Chapter 11. The Spine Library

Spine is a lightweight library for JavaScript application development that uses many of the concepts we’ve covered in this book, such as MVC, events, and classes. When I say lightweight, I mean lightweight—the library comes in at around 500 lines of JavaScript, which is about 2K minified and compressed. Don’t get the wrong impression, though; Spine will let you build fully featured JavaScript applications while ensuring your code remains clean and decoupled.

I created Spine while writing this book because I couldn’t find a client-side MVC framework that quite suited my needs. The library attempts to enshrine many of the best practices proposed in this book, and indeed the book’s example application, Holla, is built using Spine.

Unlike widget-based libraries such as Cappuccino and SproutCore, Spine doesn’t make any decisions about how you display data to users. The emphasis is on flexibility and simplicity. Spine gives you the bare bones and gets out of your way so you get on with the fun stuff—developing awesome applications.

Spine includes a class library with inheritance support, Spine.Class; an events module, Spine.Events; an ORM, Spine.Model; and a controller class, Spine.Controller. Anything else you’ll need, like

templating support or a DOM library, is up to you, so use what you’re most

familiar with. Having said that, Spine includes specific support for jQuery

and Zepto.js libraries, which complement it excellently.

Spine’s weakness at the moment is its lack of documentation. But since it’s still the early days of this library, the documentation situation is sure to improve. For now, this chapter should give you a pretty good introduction, and the sample applications will provide further explanation.

Setup

Simply download Spine from the project’s repository and include it in your page; Spine has no dependencies:

<script src="spine.js" type="text/javascript" charset="utf-8"></script>

Spine is completely namespaced behind the Spine variable, so it shouldn’t conflict with

any other variables. You can safely include libraries like jQuery, Zepto,

or Prototype without any complications.

Classes

Pretty much every object in Spine is encapsulated in a

class. However, Spine’s classes are constructed using Object.create() and pure prototypal inheritance, as covered in Chapter 3, which is different from how most class

abstractions are constructed.

To create a new class, call Spine.Class.create([instanceProperties,

classProperties]), passing an optional set of instance and class

properties:

var User = Spine.Class.create({

name: "Caroline"

});In the example above, instances of User now have a default name property. Behind

the scenes, create() is creating a new

object whose prototype is set to Spine.Class —i.e., it’s inheriting from it. If you want to create

subsequent subclasses, simply call create() on their parent class:

var Friend = User.create();

Friend is now a subclass of

User and will inherit all of its

properties:

assertEqual( Friend.prototype.name, "Caroline" );

Instantiation

You can instantiate classes using the new

keyword, for example:

var user = new User; assertEqual( user.name, "Caroline" ); user.name = "Trish"; assertEqual( user.name, "Trish" );

Any arguments passed to the construction

function will be sent to the instances initializer function,

init():

var User = Spine.Class.create({

init: function(name){

this.name = name;

}

});

var user = new User("Martina");

assertEqual( user.name, "Martina" );Extending Classes

As well as setting class and

instance properties during creation, you can use include () and extend(), passing in an object literal:

User.include({

// Instance properties

});

User.extend({

// Class properties

});include() and extend() pave the way for modules, which are

reusable pieces of code that you can include multiple times:

var ORM = {

extended: function(){

// invoked when extended

// this === User

},

find: function(){ /* ... */ },

first: function(){ /* ... */ }

};

User.extend( ORM );You can receive a callback when a module is included or extended. In the example

above, the extended function will be

invoked when User.extend() is called with a context of User. Likewise, if a module has an included property, it will be invoked when the

module is included inside a class.

Because we’re using prototypal-based inheritance, any properties we add onto classes will be reflected dynamically across subclasses at runtime:

var Friend = User.create();

User.include({

email: "info@eribium.org"

});

assertEqual( (new Friend).email, "info@eribium.org" );Properties in subclasses can be overridden without affecting the parent class. However, modifications to objects in subclasses, such as arrays, will be reflected across the whole inheritance tree. If you want an object to be specific to a class or instance, you’ll need to create it when the class or instance is first initialized.

Context

Context changes are rife within JavaScript programs, so

Spine.Class includes some utility

methods for controlling scope. To demonstrate the problem, take this

example:

var Controller = Spine.Class.create({

init: function(){

// Add event listener

$("#destroy").click(this.destroy);

},

destroy: function(){

// This destroy function is called with the wrong context,

// so any references to `this` will cause problems

// The following assertion will fail:

assertEqual( this, Controller.fn );

}

});In the example above, when the event is invoked, the destroy() function will be called with the context of the element #destroy, rather than the Controller. To deal

with this, you can proxy the context, forcing it to be a particular one

you specify. Spine gives you the proxy() function to do that:

var Controller = Spine.Class.create({

init: function(){

$("#destroy").click(this.proxy(this.destroy));

},

destroy: function(){ }

});Events

Events are key to Spine, and they are frequently used

internally. Spine’s event functionality is contained inside the module

Spine.Events, which can be included

wherever it’s needed. For example, let’s add some event support to a Spine

class:

var User = Spine.Class.create(); User.extend(Spine.Events);

Spine.Events gives you three

functions for handling events:

bind(eventName, callback)trigger(eventName, [*data])unbind(eventName, [callback])

If you’ve used jQuery’s event API, this will look very familiar to

you. For example, let’s bind and trigger an event on our User class:

User.bind("create", function(){ /* ... */ });

User.trigger("create");To bind multiple events with a single callback, just separate them with spaces:

User.bind("create update", function(){ /* ... */ });trigger() takes an event name and

passes optional arguments along to the event’s callbacks:

User.bind("countChange", function(count){

// `count` is passed by trigger

assertEqual(count, 5);

});

User.trigger("countChange", 5);You will most commonly use Spine’s events with data binding, hooking up your application’s models with its views. We’ll cover that in detail later in the section Building a Contacts Manager.

Models

If you take a peek at Spine’s source code, you’ll see that the vast majority of it deals with models, and rightly so—models are the central part of any MVC application. Models deal with storing and manipulating your application’s data, and Spine simplifies this by providing a full ORM.

Rather than use the create()

function to make a new model, which is already reserved, use Spine.Model.setup(name, attrs), passing in the

model name and an array of attribute names:

// Create the Task model.

var Task = Spine.Model.setup("Task", ["name", "done"]);Use include() and extend() to add instance and class properties:

Task.extend({

// Return all done tasks.

done: function(){ /* ... */ }

});

Task.include({

// Default name

name: "Empty...",

done: false,

toggle: function(){

this.done = !this.done;

}

});When instantiating a record, you can pass an optional object containing the record’s initial properties:

var task = new Task({name: "Walk the dog"});

assertEqual( task.name, "Walk the dog" );Setting and retrieving attributes is the same as setting and getting

properties on a normal object. In addition, the attributes() function returns an object literal

containing all the record’s attributes:

var task = new Task;

task.name = "Read the paper";

assertEqual( task.attributes(), {name: "Read the paper"} );Saving new or existing records is as simple as calling the save() function. When saving a record, an ID will be generated if it doesn’t

already exist; then, the record will be persisted locally in

memory:

var task = new Task({name: "Finish book"});

task.save();

task.id //=> "44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B"Records can be retrieved using the model’s find() function, passing in the record’s ID:

var task = Task.find("44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B");

assertEqual( task.name, "Finish book" );If no record exists for the given ID, an exception will be raised.

You can check whether a record exists without fear of an exception using

the exists() function:

var taskExists = Task.exists("44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B");

assert( taskExists );You can remove a record from the local cache by using the destroy() function:

var task = Task.create({name: "Thanks for all the fish"});

assert( task.exists() );

task.destroy();

assertEqual( task.exists(), false );Fetching Records

Retrieving records by ID is only one way of fetching them.

Typically, it’s useful to iterate through all the records or to return a

filtered subset. Spine lets you do this using all(), select(), and each():

// Return all tasks

Task.all(); //=> [Object]

// Return all tasks with a false done attribute

var pending = Task.select(function(task){ return !task.done });

// Invoke a callback for each task

Task.each(function(task){ /* ... */ });In addition, Spine provides a few helpers for finding records by attribute:

// Finds first task with the specified attribute value Task.findByAttribute(name, value); //=> Object // Finds all tasks with the specified attribute value Task.findAllByAttribute(name, value); //=> [Object]

Model Events

You can bind to model events to get callbacks when records change:

Task.bind("save", function(record){

console.log(record.name, "was saved!");

});If a record is involved, it will be passed to the event callback. You can bind a listener to the model to receive global callbacks for every record, or you can bind a listener to a specific record:

Task.first().bind("save", function(){

console.log(this.name, "was saved!")

});

Task.first().updateAttributes({name: "Tea with the Queen"});Although you can obviously create custom events using trigger(), the following are available:

- save

Record was saved (either created/updated)

- update

Record was updated

- create

Record was created

- destroy

Record was destroyed

- change

Any of the above; record was created/updated/destroyed

- refresh

All records invalidated and replaced

- error

Validation failed

You’ll find that model events are crucial when creating your application, especially when it comes to binding models up to the view.

Validation

Validation is achieved in the simplest possible way, by

overriding the model instance’s validate() function. validate() is called whenever the record is

saved. If validate() returns

anything, the validation fails. Otherwise, the save continues

unhindered, persisting the record to local memory:

Task.include({

validate: function(){

if ( !this.name ) return "Name required";

}

});If validation fails, you should return a string from validate() with an explanation. Use this

message to notify the user of what went wrong and how to correct

it:

Task.bind("error", function(record, msg){

// Very basic error notification

alert("Task didn't save: " + msg);

});The model’s error event will be invoked whenever validation fails. Callbacks will be passed the invalid record and error message.

Persistence

Spine’s records are always persisted in memory, but you have a choice of storage backends, such as HTML5’s Local Storage or Ajax.

Using Local Storage is trivial. Just include the

spine.model.local.js JavaScript file, and extend

your model with Spine.Model.Local:

// Save with local storage Task.extend(Spine.Model.Local); Task.fetch();

The records won’t be retrieved automatically from the browser’s

local storage, so you’ll need to call fetch() to populate your model with

preexisting data. This is typically done after everything else in your

application has been initialized. Once the model has been populated with

new data, the refresh event will be

triggered:

Task.bind("refresh", function(){

// New tasks!

renderTemplate(Task.all());

});Using Ajax persistence is similar; just include the

spine.model.ajax.js script and extend your model

with Spine.Model.Ajax:

// Save to server Task.extend(Spine.Model.Ajax);

By default, Spine detects the model name and uses some basic

pluralization to generate a URL. So, for the example above, the Task model’s URL would be /tasks. You can override this default behavior

by providing your own URL property on the class:

// Add a custom URL

Task.extend({

url: "/tasks"

});

// Fetch new tasks from the server

Task.fetch();As soon as Task.fetch() is called, Spine will make an Ajax GET request to

/tasks, expecting a JSON response

containing an array of tasks. If the server returns a successful

response, the records will be loaded and the

refresh event triggered.

Spine will send Ajax requests to the server whenever you create, update, or destroy a record, keeping the two in sync. The library expects your server to be structured in a RESTful way so it works seamlessly, although you can obviously override this to suit a custom setup. Spine expects these endpoints to exist:

read → GET /collection create → POST /collection update → PUT /collection/id destroy → DELETE /collection/id

After a record has been created client side, Spine will send off

an HTTP POST to your server, including a JSON representation of the

record. Let’s create a Task with a

name of "Buy eggs"; this is the

request that would be sent to the server:

POST /tasks HTTP/1.0

Host: localhost:3000

Origin: http://localhost:3000

Content-Length: 66

Content-Type: application/json

{"id": "44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B", "name": "Buy eggs"}Likewise, destroying a record will trigger a DELETE request to the server, and updating a record will trigger a PUT request. For PUT and DELETE requests, the record’s ID is referenced inside the URL:

PUT /tasks/44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B HTTP/1.0

Host: localhost:3000

Origin: http://localhost:3000

Content-Length: 71

Content-Type: application/json

{"id": "44E1DB33-2455-4728-AEA2-ECBD724B5E7B", "name": "Buy more eggs"}Spine has a different take on Ajax syncing than most other libraries. It sends a request to the server after the record has been saved client side, so the client is never waiting for a response. This means your client is totally decoupled from your server— i.e., it doesn’t need a server to be present in order to function.

Having a decoupled server offers three major advantages. First, your interface is fast and nonblocking, so users are never waiting to interact with your application. The second is that it simplifies your code—you don’t need to plan for a record that may be displayed in the user interface but isn’t editable due to a pending server response. Third, it makes it much easier to add offline support, if that’s ever required.

What about server-side validation? Spine assumes you’ll do all necessary validation client side. The only time a server should respond with an error is if there’s been an exception (a problem with your code), which should only happen in exceptional circumstances.

When the server returns an unsuccessful response, an

ajaxError event will be fired on the model, including the record, an

XMLHttpRequest object, Ajax settings,

and the thrown error:

Task.bind("ajaxError", function(record, xhr, settings, error){

// Invalid response

});Controllers

Controllers are the last component to Spine, and they

provide the glue that will tie the rest of your application together.

Controllers generally add event handlers to DOM elements and models,

render templates, and keep the view and models in sync. To create a Spine

controller, you need to subclass Spine.Controller by calling create():

jQuery(function(){

window.Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

// Controller properties

});

});It’s recommended to load controllers only after the rest of the page

has loaded, so you don’t have to deal with different page states. In all

the Spine examples, you’ll notice each controller is contained inside a

call to jQuery(). This ensures that the

controller will be created only when the document’s ready.

In Spine, the convention is to give controllers camel-cased plural

names—usually, the plural of the model with which they’re associated. Most

controllers just have instance properties, as they’re used after

instantiation only. Instantiating controllers is the same as instantiating

any other class, by using the new

keyword:

var tasks = new Tasks;

Controllers always have a DOM element associated with them, which can be accessed through the

el property. You can optionally pass this through on instantiation;

otherwise, the controller will generate a default div element:

var tasks = new Tasks({el: $("#tasks")});

assertEqual( tasks.el.attr("id"), "tasks" );This element can be used internally to append templates and render views:

window.Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

init: function(){

this.el.html("Some rendered text");

}

});

var tasks = new Tasks();

$("body").append(tasks.el);In fact, any arguments you pass when instantiating the controller will be set as properties on the controller. For example:

var tasks = new Tasks({item: Task.first()});

assertEqual( Task.first(), tasks.item );Elements

It’s often useful to access elements inside your

controller as local properties. Spine provides a shortcut for this:

elements. Just add the elements property on your controller,

containing an object of selectors to names. In the example below,

this.input refers to the element selected by form input[type=text]. All selections are done

in the context of the controller’s element (el), not the whole page:

// The `input` instance variable

var Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

elements: {

"form input[type=text]": "input"

},

init: function(){

// this.input refers to the form's input

console.log( this.input.val() );

}

});Keep in mind, though, that if you replace the HTML of the

controller’s element (el), you’ll

need to call refreshElements() to refresh all the element’s references.

Delegating Events

Spine’s events

property gives you an easy way to add event listeners in bulk.

Behind the scenes, Spine takes advantage of event bubbling, so only one event listener is added onto the controller’s

element (el). Like the events property, all event delegation is

scoped by el.

Events take the form of {"eventName

selector": "callback"}. The selector is optional and, if it

isn’t provided, the event will be placed straight on el. Otherwise, the event will be delegated, and it will be

triggered if the event type is fired on a child matching the selector.

This happens dynamically, so it doesn’t matter whether the contents of

el change:

var Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

events: {

"keydown form input[type=text]": "keydown"

},

keydown: function(e){ /* ... */ }

});In the example above, whenever the input matching the selector

receives a keydown event, the controller’s keydown callback is executed. Spine makes sure

that it’s executed with the correct context, so you don’t need to worry

about proxying event callbacks in this case.

The event object is passed along to the callback, which is useful in this

example because we can tell which key was pressed. Additionally, the

element in question can be retrieved from the event’s target property.

Controller Events

As well as event delegation, Spine’s controllers support

custom events. By default, controllers are extending with Spine.Events, meaning they have all the event functionality that

entails, like bind() and trigger(). You can use this to ensure that

your controllers are decoupled from each other, or as part of the

controller’s internal structure:

var Sidebar = Spine.Controller.create({

events: {

"click [data-name]": this.click

},

init: function(){

this.bind("change", this.change);

},

change: function(name){ /* ... */ },

click: function(e){

this.trigger("change", $(e.target).attr("data-name"));

}

// ...

});

var sidebar = new Sidebar({el: $("#sidebar")});

sidebar.bind("change", function(name){

console.log("Sidebar changed:", name);

})In the example above, other controllers can bind to Sidebar’s change event or

even trigger it. As we explored in Chapter 2,

custom events can be a great way of structuring applications internally,

even if they’re never used externally.

Global Events

Spine lets you bind to and trigger events on a global

basis. This is a form of PubSub, and it lets controllers communicate without even knowing

about one another, ensuring they’re properly decoupled. This is achieved

by having a global object, Spine,

which anything can bind to or trigger events on:

var Sidebar = Spine.Controller.create({

init: function(){

Spine.bind("change", this.proxy(this.change));

},

change: function(name){ /* ... */ }

});You can see in the example above that the Sidebar controller is binding to the global

event change. Other controllers or scripts can then

trigger this event, passing any required data:

Spine.trigger("change", "messages");The Render Pattern

Now that we’ve covered all the main options available in controllers, let’s look at some typical use cases.

The render pattern is a

really useful way of binding models and views. When the controller is

instantiated, it adds an event listener to the relevant model, invoking

a callback when the model is refreshed or changed. The callback will

update el, usually by replacing its

contents with a rendered template:

var Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

init: function(){

Task.bind("refresh change", this.proxy(this.render));

},

template: function(items){

return($("#tasksTemplate").tmpl(items));

},

render: function(){

this.el.html(this.template(Task.all()));

}

});This simple but blunt method for data binding updates every element whenever a single record is changed. This is fine for uncomplicated and small lists, but you may find you need more control over individual elements, such as adding event handlers to items. This is where the element pattern comes in.

The Element Pattern

The element pattern essentially gives you the same functionality as the render pattern, but with a lot more control. It consists of two controllers: one that controls a collection of items, and one that deals with each individual item. Let’s dive right into the code to give you a good indication of how it works:

var TasksItem = Spine.Controller.create({

// Delegate the click event to a local handler

events: {

"click": "click"

},

// Bind events to the record

init: function(){

this.item.bind("update", this.proxy(this.render));

this.item.bind("destroy", this.proxy(this.remove));

},

// Render an element

render: function(item){

if (item) this.item = item;

this.el.html(this.template(this.item));

return this;

},

// Use a template, in this case via jQuery.tmpl.js

template: function(items){

return($("#tasksTemplate").tmpl(items));

},

// Called after an element is destroyed

remove: function(){

this.el.remove();

},

// We have fine control over events, and

// easy access to the record too

click: function(){ /* ... */ }

});

var Tasks = Spine.Controller.create({

init: function(){

Task.bind("refresh", this.proxy(this.addAll));

Task.bind("create", this.proxy(this.addOne));

},

addOne: function(item){

var task = new TasksItem({item: item});

this.el.append(task.render().el);

},

addAll: function(){

Task.each(this.addOne);

}

});In the example above, Tasks has

responsibility for adding records when they’re initially created, and

TasksItem takes responsibility for

the record’s update and destroy events, rerendering the record when

necessary. Although it’s more complicated, this gives us some advantages

over the previous render pattern.

For one thing, it’s more efficient—the list doesn’t need to be

redrawn whenever a single element changes. Furthermore, we now have a

lot more control over individual items. We can place event handlers, as

demonstrated with the click callback,

and manage rendering on an item-by-item basis.

Building a Contacts Manager

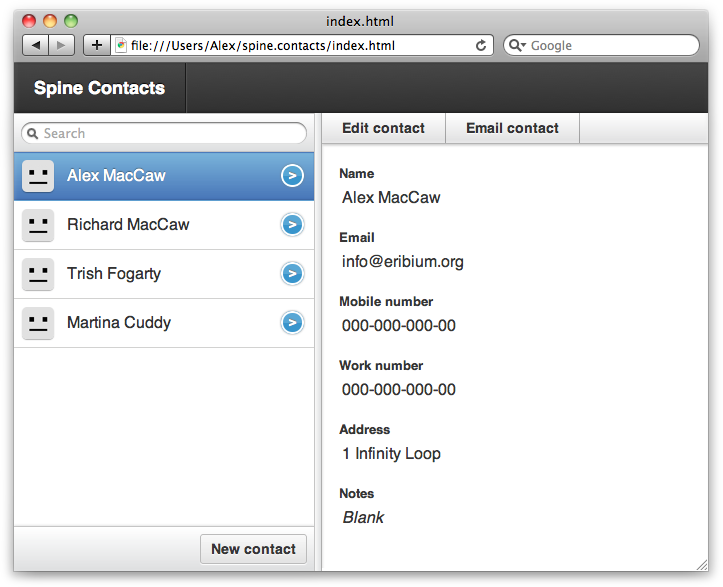

So, let’s take our knowledge of Spine’s API and apply it to something practical, like a contacts manager. We want to give users a way of reading, creating, updating, and deleting contacts, as well as searching them.

Figure 11-1 shows the finished result so you can have an idea of what we’re creating.

The contact manager is one of a set of open source Spine examples. You can follow along with the tutorial below, or download the full code from the project’s repository.

As you can see in Figure 11-1, the contact manager

has two main sections, the sidebar and the contacts view. These two will

make up our respective controllers, Sidebar and Contacts. As for models, the manager only has

one: the Contact model. Before we

expand on each individual component, let’s take a look at the initial page

structure:

<div id="sidebar">

<ul class="items">

</ul>

<footer>

<button>New contact</button>

</footer>

</div>

<div class="vdivide"></div>

<div id="contacts">

<div class="show">

<ul class="options">

<li class="optEdit">Edit contact</li>

<li class="optEmail">Email contact</li>

</ul>

<div class="content"></div>

</div>

<div class="edit">

<ul class="options">

<li class="optSave default">Save contact</li>

<li class="optDestroy">Delete contact</li>

</ul>

<div class="content"></div>

</div>

</div>We have a #sidebar div and a

#contacts div for our respective

sections. Our application is going to fill the .items list with contact names and have a

currently selected contact showing in #contacts. We’ll listen to clicks on .optEmail and .optSave, toggling between the show and edit states as

required. Finally, we’ll listen for click events on .optDestroy, which destroys the current contact

and selects another.

Contact Model

With just a half-dozen lines of code, the contact model is

exceedingly straightforward. Contact

has three attributes: first_name,

last_name, and email. We’ll also provide a helper function

that will give a full name, which will be useful in templates:

// Create the model

var Contact = Spine.Model.setup("Contact", ["first_name", "last_name", "email"]);

// Persist model between page reloads

Contact.extend(Spine.Model.Local);

// Add some instance functions

Contact.include({

fullName: function(){

if ( !this.first_name && !this.last_name ) return;

return(this.first_name + " " + this.last_name);

}

});Notice that Spine.Model.Local

is extending the model. This will ensure that records are saved to the

browser’s local storage, making them available the next time the page

loads.

Sidebar Controller

Now let’s take a look at the Sidebar controller, which has the

responsibility of listing contacts and keeping track of the currently

selected one. Whenever contacts change, the Sidebar controller must update itself to

reflect those changes. In addition, the sidebar has a “New contact”

button that it will listen to, creating new blank contacts when it’s

clicked.

Here’s the full controller in all its glory. This might be an overwhelming piece of code at first—especially if you’re not familiar with Spine—but it’s heavily commented, so it should be understandable under closer examination:

jQuery(function($){

window.Sidebar = Spine.Controller.create({

// Create instance variables:

// this.items //=> <ul></ul>

elements: {

".items": "items"

},

// Attach event delegation

events: {

"click button": "create"

},

// Render template

template: function(items){

return($("#contactsTemplate").tmpl(items));

},

init: function(){

this.list = new Spine.List({

el: this.items,

template: this.template

});

// When the list's current item changes, show the contact

this.list.bind("change", this.proxy(function(item){

Spine.trigger("show:contact", item);

}));

// When the current contact changes, i.e., when a new contact is created,

// change the list's currently selected item

Spine.bind("show:contact edit:contact", this.list.change);

// Rerender whenever contacts are populated or changed

Contact.bind("refresh change", this.proxy(this.render));

},

render: function(){

var items = Contact.all();

this.list.render(items);

},

// Called when 'Create' button is clicked

create: function(){

var item = Contact.create();

Spine.trigger("edit:contact", item);

}

});

});You’ll notice that the controller’s init() function is using a class called

Spine.List, something we haven’t yet covered. Spine.List is a utility controller that’s

great for generating lists of records. What’s more, Spine.List will keep track of a currently

selected item, and then notify listeners with a

change event when the user selects a different item.

The list is completely rerendered whenever contacts are changed or refreshed. This keeps the example nice and simple, but it may be something we want to change in the future if performance issues arise.

The #contactsTemplate

referenced in template() is a script

element that contains our contact’s template for individual list

items:

<script type="text/x-jquery-tmpl" id="contactsTemplate">

<li class="item">

{{if fullName()}}

<span>${fullName()}</span>

{{else}}

<span>No Name</span>

{{/if}}

</li>

</script>We are using jQuery.tmpl for the

templating, which should be familiar to you if you’ve read Chapter 5. Spine.List will use this template to render

each item, and it will set a class of current on the <li> if it’s associated with the

currently selected item.

Contacts Controller

Our Sidebar controller

is now displaying a list of contacts, allowing users to select

individual ones. But how about showing the currently selected contact?

This is where the Contacts controller

comes in:

jQuery(function($){

window.Contacts = Spine.Controller.create({

// Populate internal element properties

elements: {

".show": "showEl",

".show .content": "showContent",

".edit": "editEl"

},

init: function(){

// Initial view shows contact

this.show();

// Rerender the view when the contact is changed

Contact.bind("change", this.proxy(this.render));

// Bind to global events

Spine.bind("show:contact", this.proxy(this.show));

},

change: function(item){

this.current = item;

this.render();

},

render: function(){

this.showContent.html($("#contactTemplate").tmpl(this.current));

},

show: function(item){

if (item && item.model) this.change(item);

this.showEl.show();

this.editEl.hide();

}

});Whenever a new contact is selected in the sidebar, the global

show:contact event will be triggered. We’re binding to this event in Contacts, executing the show() function, which gets passed the newly

selected contact. We’re then rerendering the showContent div, replacing it with the

currently selected record.

You can see we’ve referenced a #contactTemplate template, which will display

Contacts' current contact to our

users. Let’s go ahead and add that template to the page:

<script type="text/x-jquery-tmpl" id="contactTemplate">

<label>

<span>Name</span>

${first_name} ${last_name}

</label>

<label>

<span>Email</span>

{{if email}}

${email}

{{else}}

<div class="empty">Blank</div>

{{/if}}

</label>

</script>We’ve now got functionality to show contacts, but how about

editing and destroying them? Let’s rewrite the Contacts controller to do that. The main

difference is that we’re going to

toggle between two application states, showing and editing when the

.optEdit and

.optSave elements are clicked. We’re

also going to add a new template into the fray: #editContactTemplate. When saving records,

we’ll read the edit form’s inputs and update the record’s

attributes:

jQuery(function($){

window.Contacts = Spine.Controller.create({

// Populate internal element properties

elements: {

".show": "showEl",

".edit": "editEl",

".show .content": "showContent",

".edit .content": "editContent"

},

// Delegate events

events: {

"click .optEdit": "edit",

"click .optDestroy": "destroy",

"click .optSave": "save"

},

init: function(){

this.show();

Contact.bind("change", this.proxy(this.render));

Spine.bind("show:contact", this.proxy(this.show));

Spine.bind("edit:contact", this.proxy(this.edit));

},

change: function(item){

this.current = item;

this.render();

},

render: function(){

this.showContent.html($("#contactTemplate").tmpl(this.current));

this.editContent.html($("#editContactTemplate").tmpl(this.current));

},

show: function(item){

if (item && item.model) this.change(item);

this.showEl.show();

this.editEl.hide();

},

// Called when the 'edit' button is clicked

edit: function(item){

if (item && item.model) this.change(item);

this.showEl.hide();

this.editEl.show();

},

// Called when the 'delete' button is clicked

destroy: function(){

this.current.destroy();

},

// Called when the 'save' button is clicked

save: function(){

var atts = this.editEl.serializeForm();

this.current.updateAttributes(atts);

this.show();

}

});

});As mentioned previously, we’re using a new template called

#editContactTemplate. We need to add this to the page so it can

be referenced successfully. Essentially, #editContactTemplate is very similar to

#contactTemplate, except that it’s

using input elements to display the record’s data:

<script type="text/x-jquery-tmpl" id="editContactTemplate">

<label>

<span>First name</span>

<input type="text" name="first_name" value="${first_name}" autofocus>

</label>

<label>

<span>Last name</span>

<input type="text" name="last_name" value="${last_name}">

</label>

<label>

<span>Email</span>

<input type="text" name="email" value="${email}">

</label>

</script>App Controller

So, we’ve got two controllers—Sidebar and Contacts—that deal with selecting, displaying,

and editing Contact records. Now all

that’s needed is an App controller

that instantiates every other controller, passing them the page elements

they require:

jQuery(function($){

window.App = new Spine.Controller.create({

el: $("body"),

elements: {

"#sidebar": "sidebarEl",

"#contacts": "contactsEl"

},

init: function(){

this.sidebar = new Sidebar({el: this.sidebarEl});

this.contact = new Contacts({el: this.contactsEl});

// Fetch contacts from local storage

Contact.fetch();

}

})

});Notice we’re instantiating the class with new immediately after creating the App controller. We’re also calling fetch() on the Contact model, retrieving all the contacts

from local storage.

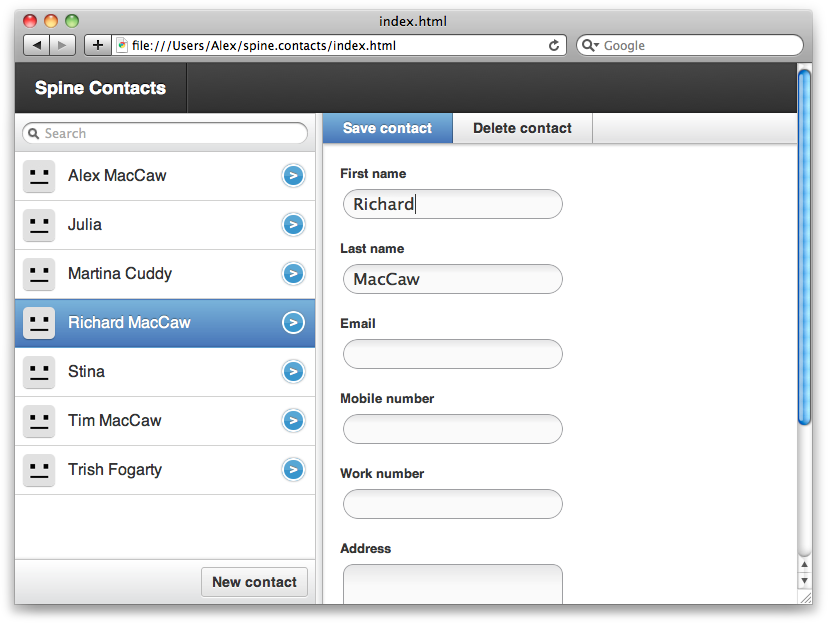

So, that’s all there is to it! Two main controllers (Sidebar and Contacts), one model (Contact), and a couple of views. To see the

finished product, check out the source repository

and see Figure 11-2.