Chapter 10. Deploying

Deploying your web application properly is just as important as actually developing it; there’s no point in building the next Facebook if it loads too slowly for people to actually use it. Users want your site to be as reliable and fast as possible, with good uptime. Deploying JavaScript and HTML files sounds straightforward—they’re static assets after all—but there’s actually a fair amount to it. This is an often neglected part to web application building.

Luckily, there are a few tried-and-tested techniques that should apply to all JavaScript applications, and indeed serving any kind of static assets. If you follow the recommendations below, you should be well on your way to delivering speedy web apps.

Performance

One of the simplest ways of increasing performance is also the most obvious: minimize the amount of HTTP requests. Every HTTP request contains a lot of header information, as well as the TCP overhead. Keeping separate connections to an absolute minimum will ensure pages load faster for users. This clearly extends to the amount of data the server needs to transfer. Keeping a page and its assets’ file size low will decrease any network time—the real bottleneck to any application on the Web.

Concatenating scripts into a single script and combining CSS into a single stylesheet will reduce the amount of HTTP connections needed to render the page. You can do this upon deployment or at runtime. If it’s the latter, make sure any files generated are cached in production.

Use CSS sprites to combine images into one comprehensive image. Then, use

the CSS background-image and background-position properties to display the

relevant images in your page. You just have to scope the background

position coordinates to cover the desired image.

Avoiding redirects also keeps the number of HTTP requests to a minimum. You may think these are fairly uncommon, but one of the most frequent redirect scenarios occurs when a trailing slash (/) is missing from a URL that should otherwise have one. For example, going to http://facebook.com currently redirects you to http://facebook.com/. If you’re using Apache, you can fix this by using Alias or mod_rewrite.

It’s also important to understand how your browser downloads resources. To speed up page rendering, modern browsers download required resources in parallel. However, the page can’t start rendering until all the stylesheets and scripts have finished downloading. Some browsers go even further, blocking all other downloads while any JavaScript files are being processed.

However, most scripts need to access the DOM and add things like event handlers,

which are executed after the page loads. In other words, the browser is

needlessly restricting the page rendering until everything’s finished

downloading, decreasing performance. You can solve this by setting the

defer attribute on scripts, letting the

browser know the script won’t need to manipulate the DOM until after the

page has loaded:

<script src="foo.js" type="text/javascript" charset="utf-8" defer></script>

Scripts with the defer attribute

set to “defer” will be downloaded in parallel with other

resources and won’t prevent page rendering. HTML5 has also introduced a

new mode of script downloading and execution called async. By setting the async attribute, the script will be executed at the first opportunity after

it’s finished downloading. This means it’s possible (and likely) that

async scripts are not executed in the order in which they occur in the

page, leaving an opportunity for dependency errors. If the script doesn’t

have any dependencies, though, async is a useful tool. Google

Analytics, for example, takes advantage of it by default:

<script src="http://www.google-analytics.com/ga.js" async></script>

Caching

If it weren’t for caching, the Web would collapse under network traffic. Caching stores recently requested resources locally so subsequent requests can serve them up from the disk, rather than downloading them again. It’s important to explicitly tell browsers what you want cached. Some browsers like Chrome will make their own default decisions, but you shouldn’t rely on that.

For static resources, make the cache “never” expire by adding a far

future Expires header. This will ensure that the browser only ever downloads the

resource once, and it should then be set on all static components,

including scripts, stylesheets, and images.

Expires: Thu, 20 March 2015 00:00:00 GMT

You should set the expiry date in the far future relative to the

current date. The example above tells the browser the cache won’t be stale

until March 20th, 2015. If you’re using the Apache web server, you can set a

relative expiration date easily using ExpiresDefault:

ExpiresDefault "access plus 5 years"

But what if you want to expire the resource before that time? A useful technique is to append the file’s modified time (or mtime) as a query parameter on URLs referencing it. Rails, for example, does this by default. Then, whenever the file is modified, the resource’s URL will change, clearing out the cache.

<link rel="stylesheet" href="master.css?1296085785" type="text/css">

HTTP 1.1. introduced a new class of headers, Cache-Control, to give developers more advanced caching and to address

the limitations of Expires. The

Cache-Control control header can take a

number of options, separated by commas:

Cache-Control: max-age=3600, must-revalidate

To see the full list of options, visit the specification. The ones you’re likely to use now are listed below:

-

max-age Specifies the maximum amount of time, in seconds, that a resource will be considered fresh. Unlike

Expires, which is absolute, this directive is relative to the time of the request.-

public Marks resources as cacheable. By default, if resources are served over SSL or if HTTP authentication is used, caching is turned off.

-

no-store Turns off caching completely, which is something you’ll want to do for dynamic content only.

-

must-revalidate Tells caches they must obey any information you give them regarding resource freshness. Under certain conditions, HTTP allows caches to serve stale resources according to their own rules. By specifying this header, you’re telling the cache that you want it to strictly follow your rules.

Adding a Last-Modified header

to the served resource can also help caching. With

subsequent requests to the resource, browsers can specify the If-Modified-Since header, which contains a timestamp. If the resource hasn’t been

modified since the last request, the server can just return a 304 (not

modified) status. The browser still has to make the request, but the

server doesn’t have to include the resource in its response, saving

network time and bandwidth:

# Request GET /example.gif HTTP/1.1 Host:www.example.com If-Modified-Since:Thu, 29 Apr 2010 12:09:05 GMT # Response HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Thu, 20 March 2009 00:00:00 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.3 (Unix) Cache-Control: max-age=3600, must-revalidate Expires: Fri, 30 Oct 1998 14:19:41 GMT Last-Modified: Mon, 17 March 2009 00:00:00 GMT Content-Length: 1040 Content-Type: image/gif

There is an alternative to Last-Modified: ETags. Comparing ETags is like comparing the hashes of two files; if the ETags are

different, the cache is stale and must be revalidated. This works in a

similar way to the Last-Modified

header. The server will attach an ETag to a resource with an ETag header, and a client will check ETags with

an If-None-Match header:

# Request GET /example.gif HTTP/1.1 Host:www.example.com If-Modified-Since:Thu, 29 Apr 2010 12:09:05 GMT If-None-Match:"48ef9-14a1-4855efe32ba40" # Response HTTP/1.1 304 Not Modified

ETags are typically constructed with attributes specific to the

server—i.e., two separate servers will give different ETags for the same

resource. With clusters becoming more and more common, this is a real

issue. Personally, I advise you to stick with Last-Modified

and turn off ETags altogether.

Minification

JavaScript minification reduces unnecessary characters from scripts without changing any functionality. These characters include whitespace, new lines, and comments. The better minifiers can interpret JavaScript. Therefore, they can safely shorten variables and function names, further reducing characters. Smaller file sizes are better because there’s less data to transfer over the network.

It’s not just JavaScript that can be minified. Stylesheets and HTML can also be processed. Stylesheets in particular tend to have a lot of redundant whitespace. Minification is something best done on deployment because you don’t want to be debugging any minified code. If there’s an error in production, try to reproduce it in a development environment first—you’ll find it much easier to debug the problem.

Minification has the additional benefit of obscuring your code. It’s true that a sufficiently motivated person could probably reconstruct it, but it’s a barrier to entry for the casual observer.

There are a lot of minimizing libraries out there, but I advise you to choose one with a JavaScript engine that can actually interpret the code. YUI Compressor is my favorite because it is well maintained and supported. Created by Yahoo! engineer Julien Lecomte, its goal was to shrink JavaScript files even further than JSMin by applying smart optimizations to the source code. Suppose we have the following function:

function per(value, total) {

return( (value / total) * 100 );

}YUI Compressor will, in addition to removing whitespace, shorten the local variables, saving yet more characters:

function per(b,a){return((b/a)*100)};Because YUI Compressor actually parses the JavaScript, it can

usually replace variables—without

introducing code errors. However, this isn’t always the case; sometimes

the compressor can’t fathom your code, so it leaves it alone. The most

common reason for this is the use of an eval() or with() statement. If the compressor detects

you’re using either of those, it won’t perform variable name replacement.

In addition, both eval() and with() can cause performance problems—the

browser’s JIT compiler has the same issue as the compressor. My advice is

to stay well clear of either of these statements.

The simplest way to use YUI Compressor is by downloading the binaries, which require Java, and executing them on the command line:

java -jar yuicompressor-x.y.z.jar foo.js > foo.min.js

However, you can do this programmatically on deployment. If you’re using a library like Sprockets or Less, they’ll do this for you. Otherwise, there are several interface libraries to YUI Compressor, such as Sam Stephenson’s Ruby-YUI-compressor gem or the Jammit library.

Gzip Compression

Gzip is the most popular and supported compression method on

the Web. It was developed by the GNU project, and support for it was added

in HTTP/1.1. Web clients indicate their support for compression by sending

an Accept-Encoding header along with

the request:

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

If the web server sees this header and supports any of the

compression types listed, it may compress its response and indicate this

via the Content-Encoding header:

Content-Encoding: gzip

Browsers can then decode the response properly. Obviously, compressing the data can reduce network time, but the true extent of this is often not realized. Gzip generally reduces the response size by 70%, a massive reduction that greatly speeds up the time it takes for your site to load.

Servers generally have to be configured over which file types should be gzipped. A good rule of thumb is to gzip any text response, such as HTML, JSON, JavaScript, and stylesheets. If the files are already compressed, such as images and PDFs, they shouldn’t be served with gzip because the recompression doesn’t reduce their size.

Configuring gzip depends on your web server, but if you use Apache 2.x or later, the module you need is mod_deflate. For other web servers, see their documentation.

Using a CDN

A content delivery network, or CDN, can serve static content on your behalf, reducing its load time. The user’s proximity to the web server can have an impact on load times. CDNs can deploy your content across multiple geographically dispersed servers, so when a user requests a resource, it can be served up from a server near them (ideally in the same country). Yahoo! has found that CDNs can improve enduser response times by 20% or more.

Depending on how much you can afford to spend, there are lot of companies out there offering CDNs, such as Akamai Technologies, Limelight Networks, EdgeCast, and Level 3 Communications. Amazon Web Services has recently released an affordable option called Cloud Front that ties into its S3 service closely and may be a good option for startups.

Google offers a free CDN and loading architecture for many popular open source JavaScript libraries, including jQuery and jQueryUI. One of the advantages of using Google’s CDN is that many other sites use it too, increasing the likelihood that any JavaScript files you reference are already cached in a user’s browser.

Check out the list of available libraries. If, say, you want to include the jQuery library, you can either use Google’s JavaScript loader library or, more simply, a plain old script tag:

<!-- minimized version of the jQuery library --> <script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.4.4/jquery.min.js"></script> <!-- minimized version of the jQuery UI library --> <script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jqueryui/1.8.6/jquery-ui.min.js"> </script>

You’ll notice that in the example above we haven’t specified a

protocol; instead, // is used. This is

a little-known trick that ensures the script file is fetched using the

same protocol as the host page. In other words, if your page was loaded

securely over HTTPS, the script file will be as well, eliminating any

security warnings. A relative URL without a scheme is valid and compliant

to the RTF spec. More importantly, it’s got support across the board;

heck, protocol-relative URLs even work in Internet Explorer 3.0.

Auditors

There are some really good tools to give you a quick heads up regarding your site’s performance. YSlow is an extension of Firebug, which is in turn a Firefox extension. You’ll need to install all three to use it. Once it’s installed, you can use it to audit web pages. The extension will run through a series of checks, including caching, minification, gzipping, and CDNs. It will give your site a grade, depending on how it fares, and then offer advice on how to improve your score.

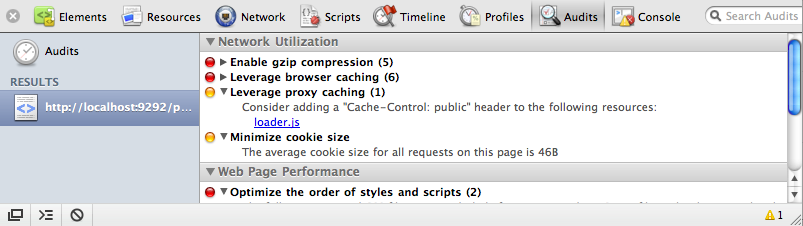

Google Chrome and Safari also have auditors, but these are built right into the browser. As shown in Chrome in Figure 10-1, simply go to the Audits section of Web Inspector and click Run. This is a great way of seeing what things your site could improve on to increase its performance.

Resources

Both Yahoo! and Google have invested a huge amount into analyzing web performance. Increasing sites’ render speed is obviously in their best interest, both for their own services and for the user experience of their customers when browsing the wider Web. Indeed, Google now takes speed into account with its Pagerank algorithm, which helps determine where sites are ranked for search queries. Both companies have excellent resources on improving performance, which you can find on the Google and Yahoo! developer sites.