Installing Linux

IN THIS CHAPTER

Choosing an installation method

Installing a single- or multi-boot system

Performing a Live media installation of Fedora

Installing Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Understanding cloud-based installations

Partitioning the disk for installation

Understanding the GRUB boot loader

Installing Linux has become a fairly easy thing to do—if you are starting with a computer that is up to spec (hard disk, RAM, CPU, and so on) and you don't mind totally erasing your hard drive. Installation is more complex if you want to stray from a default installation. So this chapter begins with a simple installation from Live media and progresses to more complex installation topics.

To ease you into the subject of installing Linux, I cover three ways of installing Linux and step you through each process:

- Installing from Live media—A Linux Live media ISO is a single, read-only image that contains everything you need to start a Linux operating system. That image can be burned to a DVD or USB drive and booted from that medium. With the Live media, you can totally ignore your computer's hard disk; in fact, you can run Live media on a system with no hard disk. After you are running the Live Linux system, some Live media ISOs allow you to launch an application that permanently installs the contents of the Live medium to your hard disk. The first installation procedure in this chapter shows you how to permanently install Linux from a Fedora Live media ISO.

- Installing from an installation DVD—An installation DVD, available with Fedora, RHEL, Ubuntu and other Linux distributions, offers more flexible ways of installing Linux. In particular, instead of just copying the whole Live media contents to your computer, with an installation DVD you can choose exactly which software packages you want. The second installation procedure I show in this chapter steps you through an installation process from a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 installation DVD.

- Installing in the enterprise—Sitting in front of a computer and clicking through installation questions isn't inconvenient if you are installing a single system. But what if you need to install dozens or hundreds of Linux systems? What if you want to install those systems in particular ways that need to be repeated over multiple installations? The last section of this chapter describes efficient ways of installing multiple Linux systems, using network installation features and kickstart files.

A fourth method of installation not covered in this chapter is to install Linux as a virtual machine on a virtualization host, such as Virtual Box or VMware system. Chapter 26 and 27 describe ways of installing or deploying a virtual machine on a Linux KVM host or in a cloud environment.

To try the procedures in this chapter along with me, you should have a computer in front of you that you don't mind totally erasing. As an alternative, you can use a computer that has another operating system installed (such as Windows), as long as there is enough unused disk space available outside that operating system. I describe the procedure, and risk of data loss, if you decide to set up one of these “dual boot” (Linux and Windows) arrangements.

Choosing a Computer

You can get a Linux distribution that runs on handheld devices or an old PC in your closet with as little as 24MB of RAM and a 486 processor. To have a good desktop PC experience with Linux, however, you should consider what you want to be able to do with Linux when you are choosing your computer.

Be sure to consider the basic specifications you need for a PC-type computer to run the Fedora and Red Hat Enterprise Linux distributions. Because Fedora is used as the basis for Red Hat Enterprise Linux releases, hardware requirements are similar for basic desktop and server hardware for those two distributions.

- Processor—A 400 MHz Pentium processor is the minimum for a GUI installation. For most applications, a 32-bit processor is fine (x86). However, if you want to set up the system to do virtualization, you need a 64-bit processor (x86_64).

NOTE

If you have a 486 machine (at least 100 MHz), consider trying Damn Small Linux (http://www.damnsmall-linux.org) or Slackware (http://www.slackware.org). It won't have the same graphical interface, but you could do some of the shell exercises. If you have a MacBook, try a GNOME version of Ubuntu that you can get at https://help.ubuntu.com/community/MacBook.

- RAM—Fedora recommends at least 1GB of RAM, but at least 2GB or 3GB would be much better. On my RHEL desktop, I'm running a web browser, word processor, and mail reader, and I'm consuming over 2GB of RAM.

- DVD or CD drive—You need to be able to boot up the installation process from a DVD, CD, or USB drive. In recent releases, the Fedora live media ISO has become too big to fit on a CD, so you need to burn it to a DVD or USB drive. If you can't boot from a DVD or USB drive, there are ways to start the installation from a hard disk or by using a PXE install. After the installation process is started, more software can sometimes be retrieved from different locations (over the network or from hard disk, for example).

NOTE

PXE (pronounced pixie) stands for Preboot eXecution Environment. You can boot a client computer from a Network Interface Card (NIC) that is PXE-enabled. If a PXE boot server is available on the network, it can provide everything a client computer needs to boot. What it boots can be an installer. So with a PXE boot, it is possible to do a complete Linux installation without a CD, DVD, or any other physical medium.

- Network card—You need wired or wireless networking hardware to be able to add more software or get software updates. Fedora offers free software repositories if you can connect to the Internet. For RHEL, updates are available as part of the subscription price.

- Disk space—Fedora recommends at least 10GB of disk space for an average desktop installation, although installations can range (depending on which packages you choose to install) from 600MB (for a minimal server with no GUI install) to 7GB (to install all packages from the installation DVD). Consider the amount of data you need to store. Although documents can consume very little space, videos can consume massive amounts of space. (By comparison, you can install the Damn Small Linux Live CD to disk with only about 200MB of disk space.)

- Special hardware features—Some Linux features require special hardware features. For example, to use Fedora or RHEL as a virtualization host using KVM, the computer must have a processor that supports virtualization. These include AMD-V or Intel-VT chips.

If you're not sure about your computer hardware, there are a few ways to check what you have. If you are running Windows, the System Properties window can show you the processor you have, as well as the amount of RAM that's installed. As an alternative, with the Fedora Live CD booted, open a shell and type dmesg | less to see a listing of hardware as it is detected on your system.

With your hardware in place, you can choose to install Linux from a Live CD or from installation media, as described in the following sections.

Installing Fedora from Live media

In Chapter 1, you learned how to get and boot up Linux Live media. This chapter steps you through an installation process of a Fedora Live DVD so it is permanently installed on your hard disk.

Simplicity is the main advantage of installing from Live media. Essentially, you are just copying the kernel, applications, and settings from the ISO image to the hard disk. There are fewer decisions you have to make to do this kind of installation, but you also don't get to choose exactly which software packages to install. After the installation, you can add and remove packages as you please.

The first decisions you have to make about your Live media installation include where you want to install the system and whether you want to keep existing operating systems around when your installation is done:

- Single-boot computer—The easiest way to install Linux is to not have to worry about other operating systems or data on the computer and have Linux replace everything. When you are done, the computer boots up directly to Fedora.

- Multi-boot computer—If you already have Windows installed on a computer, and you don't want to erase it, you can install Fedora along with Windows on that system. Then at boot time, you can choose which operating system to start up. To be able to install Fedora on a system with another operating system installed, you must either have extra disk space available (outside the Windows partition) or be able to shrink the Windows system to gain enough free space to install Fedora.

- Bare metal or virtual system—The resulting Fedora installation can be installed to boot up directly from the computer hardware or from within an existing operating system on the computer. If you have a computer that is running as a virtual host, you can install Fedora on that system as a virtual guest. Virtualization host software includes KVM, Xen, and VirtualBox (for Linux and UNIX systems, as well as Windows and the MAC), Hyper-V (for Microsoft systems), and VMWare (both Linux and Microsoft systems). You can use the Fedora Live ISO image from disk or burned to a DVD to start an installation from your chosen hypervisor host. (Chapter 16 describes how to set up a KVM virtualization host.)

The following procedure steps you through the process of installing the Fedora Live ISO described in Chapter 1 to your local computer. Because the Fedora 21 installation is very similar to the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 installation described later in this chapter, you can refer to that procedure if you want to go beyond the simple selections shown here (particularly in the area of storage configuration).

CAUTION

Before beginning the procedure, be sure to make backup copies of any data that you want to keep. Although you can choose to not erase selected disk partitions (as long as you have enough space available on other partitions), there is always a risk that data can be lost when you are manipulating disk partitions. Also, unplug any USB drives you have plugged into your computer because they could be overwritten.

- Get Fedora. Choose the Fedora Live media image you want to use, download it to your local system, and burn it to a DVD, as described in Chapter 1. See Appendix A for information on how to get the Fedora Live media and burn it to a DVD or USB drive.

- Boot the Live image. Insert the DVD or USB drive. When the BIOS screen appears, look for a message that tells you to press a particular function key (such as F12) to interrupt the boot process and select the boot medium. Select the DVD or USB drive, depending on which you have, and Fedora should come up and display the boot screen. When you see the boot screen, select Start Fedora Live.

- Start the installation. When the Welcome to Fedora screen appears, position your mouse over the Install to Hard Drive area and select it. Figure 9.1 shows an example of the Install to Hard Drive selection on the Fedora Live media.

Start the installation process from Live media.

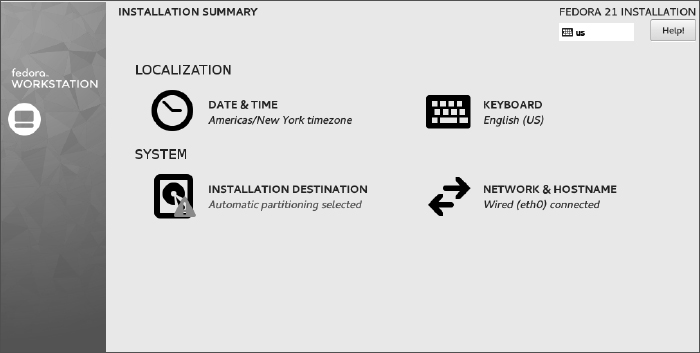

- Select the language. When prompted, choose the language type that best suits you (such as U.S. English) and select Next. You should see the Installation summary screen, as shown in Figure 9.2.

- Select DATE & TIME. From the DATE & TIME screen, you can select your time zone by either clicking the map or choosing the region and city from drop-down boxes. To set the date and time, if you have an Internet connection, you can select the Network Time button to turn it on. Or you can select OFF and set the date and time manually from boxes on the bottom of the screen. Select Done in the upper-right corner when you are finished.

Select configuration options from the Installation Summary screen.

- Select INSTALLATION DESTINATION. Available storage devices (such as your hard drive) are displayed, with your hard drive selected as the installation destination. If you want the installer to automatically install Fedora, just select Done in the upper-left corner. Here are your choices as this point:

- Automatically configure...—If there is enough available disk space on the selected disk drive, you can continue with the installation by selecting Continue. The installer will ensure that there's enough available disk space to install Fedora.

- I want more space...—If you want to get rid of some or all the space on the hard disk that is currently being used, choose this selection and click Continue. You can erase partitions that currently contain data.

- I want to review/modify...—To take more control of your disk partitioning, select this option and click Continue. This lets you add and delete partitioning to divide up you disk exactly as you like.

- Other options—From this screen, you can also choose your partitioning scheme (I recommend LVM because it allows you to expand your storage more easily later). You can also choose whether to encrypt the data on your disk, making your data inaccessible to anyone who tries to boot your computer without the password you set later.

Select Done when you have configured your storage.

- Select KEYBOARD. You can use the default English (U.S.) keyboard or select KEYBOARD to choose a different keyboard layout.

- Select NETWORK CONFIGURATION. Choose this to be able to enable your network interface and type in a hostname for the computer. If DHCP is available on the network, you can simply set your network interfaces to pick up IP address information automatically. You can also set up IP address information manually. Select Begin Installation when you are finished, and the installation process begins.

- Select ROOT PASSWORD. As Fedora installs, this selection lets you set the password for the root user. Type any password you like, and then type it again in the Confirm box. Select Done to set the password. If the password is not at least six characters long or if it is considered to be too easy (like a common word), the installer doesn't leave the password screen when you click Done. You can either change the password or click Done again to have the installer use the password anyway.

- Select CREATE USER. It is good practice to have at least one regular (non-root) user on every system, because root should be used only for administrative tasks and not everyday computer use. Add the user's full name, short username, and password. To allow this user to do administrative tasks without knowing the root password, select the “Make this user administrator” box.

By clicking the Advanced box, you can change some of the default settings. For example, with a user named chris, the default home directory would be /home/chris, and the next available user ID and group ID are assigned to the user. By selecting Advanced, you can change those settings and even assign the user to additional groups. Select Done when you are finished adding the user.

- Finish Configuration. When the first part of the installation is complete, click Finish Configuration. Some final configuration happens on the system at this point. When that is finished, select Quit. At this point, the disk is repartitioned, filesystems are formatted, the Linux image is copied to hard disk, and the necessary settings are implemented.

- Reboot. Select the little on/off button on the top-right corner of the screen. When prompted, click the restart button. Eject or remove the Live media. The computer should boot to your newly installed Fedora system. (You may need to actually power off the computer for it to boot back up.)

- Log in and begin using Fedora. The login screen appears at this point, allowing you to log in as the user account and password you just created.

- Get software updates. To keep your system secure and up to date, one of the first tasks you should do after installing Fedora is to get the latest versions of the software you just installed. If your computer has an Internet connection (plugging into a wired Ethernet network or selecting an accessible wireless network from the desktop takes care of that), you can simply open a Terminal as root and type yum update to download and update all your packages from the Internet. If a new kernel is installed, you can reboot your computer to have that new kernel take effect.

At this point, you can begin using the desktop, as described in Chapter 2. You can also use the system to perform exercises from any of the chapters in this book.

Installing Red Hat Enterprise Linux from Installation Media

In addition to offering a live DVD, most Linux distributions offer a single image or set of images that can be used to install the distribution. For this type of installation media, instead of copying the entire contents of the medium to disk, software is split up into packages that you can select to meet your exact needs. A full installation DVD, for example, can allow you to install anything from a minimal system to a full-featured desktop to a full-blown server that offers multiple services.

In this chapter, I use a Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 server edition installation DVD as the installation medium. Review the hardware information and descriptions of dual booting in the previous section before beginning your RHEL installation.

Follow this procedure to install Red Hat Enterprise Linux from an installation DVD.

- Get installation media. The process of downloading RHEL install ISO images is described on the Red Hat Enterprise Linux product page. If you are not yet a Red Hat customer, you can apply for an evaluation copy and download ISO images here: http://www.redhat.com/en/technologies/linux-platforms/enterprise-linux.

This requires that you create a Red Hat account. If that is not possible, you can download an installation DVD from a mirror site of the CentOS project to get a similar experience: http://wiki.centos.org/Download.

For this example, I used the 3.4G RHEL 7 Server DVD ISO named rhel-server-7.0-x86_64-dvd.iso. After you have the DVD ISO, you can burn it to a physical DVD as described in Appendix A.

- Boot the installation media. Insert the DVD into your DVD drive, and reboot your computer. The Welcome screen appears.

- Select Install or Test media. Select “Install” or “Test this media & install” to do a new installation of RHEL. The media test verifies that the DVD has not been corrupted during the copy or burning process. If you need to modify the installation process, you can add boot options by pressing the Tab key with a boot entry highlighted and typing in the options you want. See the section “Using installation boot options” later in this chapter.

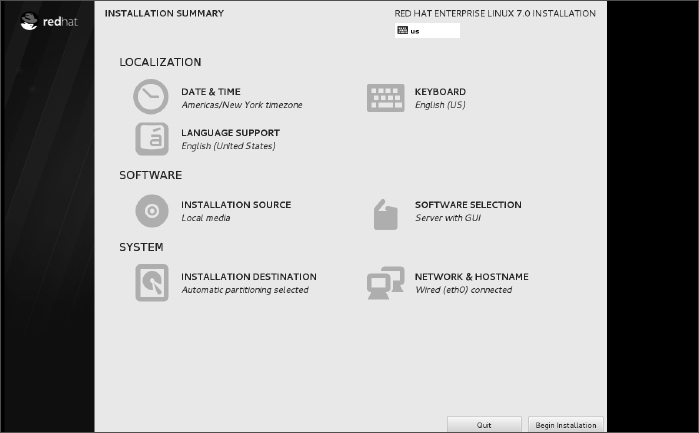

- Select a language. Select your language, and select Continue. The Installation Summary screen appears. From that screen, you can select to change: Date & Time, Language support, Keyboard, Installation Source, Software Selection, Installation Destination, and Network & Hostname, as shown in Figure 9.3.

- Date & Time. Choose a time zone for your machine from either the map or the list shown (as described in the Fedora section). Either set the time manually with up/down arrows or select Network Time to have your system try to automatically connect to networked time servers to sync system time. Select Done when you are finished.

Choose from Localization, Software, and System topics on the Installation Summary screen.

- Language support. You have a chance to add support for additional languages (beyond what you set by default earlier). Select Done when you are finished.

- Keyboard. Choose from different types of keyboards available with the languages you selected earlier. Type some text to see how the keys are laid out.

- Installation Source. The installation DVD is used, by default, to provide the RPM packages used during installation. You have the option of selecting “On the network” and choosing a Web URL (http, https, or ftp) when a Red Hat Enterprise Linux software repository is installed. After choosing the DVD or a network location, you can add additional yum repositories to have those repositories used during installation as well. Select Done when you are finished.

- Software Selection. A minimal installation is selected by default, which offers no desktop interface (shell only). If you are new to Linux and want to try out some services, the “Server with GUI” selection provides a GNOME 3 desktop system on top of a basic server install. You can select to add other services, such as a DNS, File and Storage, Identity Management, and other services. Other base environments include Infrastructure server, File and Print server, Basic Web server, and Virtualization Host server. Select Done when you are ready to continue.

- Installation Destination. The new RHEL system is installed, by default, on the local hard drive using automatic partitioning. You also have the option of attaching network storage or special storage, such as Firmware RAID. (See the section “Partitioning Hard Drives” later in this chapter for details on configuring storage.) Click Done when you are finished. You may be asked to verify that it's okay to delete existing storage.

- Network & Hostname. Any network interface cards that are discovered can be configured at this point. If a DHCP service is available on the network, network address information is assigned to the interface after you select ON. Select Configure if you prefer to configure the network interface manually. Fill in the Hostname box if you want to set the system's hostname. Setting up your network and hostname during installation can make it easier to begin using your system after installation. Click Done to continue.

- Begin Installation. Click the Begin Installation button to start the install process. A progress bar marks the progress of the installation. As the system is installing, you can set the root password and create a new user account for your new system.

- Root Password. Set the password for the root user and verify it (type it again). Click Done to accept it. If the password is too short or too weak, you stay on the page (where you can set a new password). If you decide to keep the weak password instead, click Done again to accept the weak password.

- Create User. It is good practice to log into a Linux system with a non-root user account and request root privilege as needed. You can set up a user account, including a username, full name, and password. You can select “Make this user administrator” to give that user sudo privileges (allowing the account to act as the root user as needed). Select Done when you are finished. If the password you enter is too short or otherwise weak, you must change it or click Done again if you still want to use the weak password.

- Complete the installation. When installation is finished, click Reboot. Pop out the DVD when the system restarts, and Red Hat Enterprise Linux starts up from the hard disk.

- Run firstboot. If you installed a desktop interface, the firstboot screen appears the first time you boot the system. Here's what you do:

- License—Read and agree to the License Information, click Done, and click Finish Configuration.

- Kdump—You can choose to set aside some amount of RAM for the kdump feature. If kdump is enabled, the RAM set aside can be used in the event that your kernel crashes to have a place that the kernel dump can be stored. Without kdump, there would be no way to diagnose a crashed kernel. If you enable kdump, which is done by default, you can also manually set the amount of memory to set aside for it. Click Forward when you are finished.

- Subscription Registration—Provided that your network is configured, you can select “Yes” to register your system now. When prompted, you can leave the default subscription management system in place (subscription.rhn.redhat.com) or enter the location of a Red Hat Satellite server to register your system. You need your Red Hat account and password to register and entitle your system for updates. In most cases, you can automatically attach an entitlement to the system. However, you can click the “Manually attach...” button if you want to choose a specific entitlement to attach to the system later when you log in to the system.

You should now be able to log in to your Red Hat Enterprise Linux system. One of the first things you should do is get software updates for the new system.

Understanding Cloud-Based Installations

When you install a Linux system on a physical computer, the installer can see the computer's hard drive, network interfaces, CPUs, and other hardware components. When you install Linux in a cloud environment, those physical components are abstracted into a pool of resources. So, to install a Linux distribution in an Amazon EC2, Google Compute Engine, or OpenStack cloud platform, you need to go about things differently.

The common way of installing Linux in a cloud is to start with a file that is an image of an installed Linux system. Typically, that image includes all the files needed by a basic, running Linux system. Metadata is added to that image from a configuration file or by filling out a form from a cloud controller that creates and launches the operating system as a virtual machine.

The kind of information added to the image might include a particular hostname, root password, and new user account. You might also want to choose to have a specific amount of disk space, particular network configuration, and a certain number of CPU processors.

Methods for installing Linux in a local cloud-like KVM environment are discussed in Chapter 26, “Using Linux for Cloud Computing.” Methods for deploying cloud images are contained in Chapter 27, “Deploying Linux to the Cloud.” That chapter covers how to run a Linux system as a virtual machine image on a KVM environment, Amazon EC2 cloud, or OpenStack environment.

Installing Linux in the Enterprise

If you were managing dozens, hundreds, even thousands of Linux systems in a large enterprise, it would be terribly inefficient to have to go to each computer to type and click through each installation. Fortunately, with Red Hat Enterprise Linux and other distributions, you can automate installation in such a way that all you need to do is turn on a computer and boot from the computer's network interface card to get your desired Linux installation.

Although we have focused on installing Linux from a DVD or USB media, there are many other ways to launch a Linux installation and many ways to complete an installation. The following bullets step through the installation process and describe ways of changing that process along the way:

- Launch the installation medium. You can launch an installation from any medium you can boot from a computer: CD, DVD, USB drive, hard disk, or network interface card with PXE support. The computer goes through its boot order and looks at the master boot record on the physical medium or looks for a PXE server on the network.

- Start the anaconda kernel. The job of the boot loader is to point to the special kernel (and possibly an initial RAM disk) that starts the Linux installer (called anaconda). So any of the media just described simply needs to point to the location of the kernel and initial RAM disk to start the installation. If the software packages are not on the same medium, the installation process prompts you for where to get those packages.

- Add kickstart or other boot options. Boot options (described later in this chapter) can be passed to the anaconda kernel to configure how it starts up. One option supported by Fedora and RHEL allows you to pass the location of a kickstart file to the installer. That kickstart can contain all the information needed to complete the installation: root password, partitioning, time zone, and so on to further configure the installed system. After the installer starts, it either prompts for needed information or uses the answers provided in the kickstart file.

- Find software packages. Software packages don't have to be on the installation medium. This allows you to launch an installation from a boot medium that contains only a kernel and initial RAM disk. From the kickstart file or from an option you enter manually to the installer, you can identify the location of the repository holding the RPM software packages. That location can be a local CD (cdrom), website (http), FTP site (ftp), NFS share (nfs), NFS ISO (nfsiso), or local disk (hd).

- Modify installation with kickstart scripts. Scripts included in a kickstart can run commands you choose before or after the installation to further configure the Linux system. Those commands can add users, change permissions, create files and directories, grab files over the network, or otherwise configure the installed system exactly as you specify.

Although installing Linux in enterprise environments is beyond the scope of this book, I want you to understand the technologies that are available when you want to automate the Linux installation process. Here are some of those technologies available to use with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, along with links to where you can find more information about them:

- Install server—If you set up an installation server, you don't have to carry the software packages around to each machine where you install RHEL. Essentially, you copy all the software packages from the RHEL installation medium to a web server (http), FTP server (ftp), or NFS server (nfs), and then point to the location of that server when you boot the installer. The RHEL Installation Guide describes how to set up an installation server (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html-single/Installation_Guide/index.html#sect-making-media-sources-network).

- PXE server—If you have a computer with a network interface card that supports PXE booting (as most do), you can set your computer's BIOS to boot from that NIC. If you have set up a PXE server on that network, that server can present a menu to the computer containing entries to launch an installation process. The RHEL Installation Guide provides information on how to set up PXE servers for installation (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html-single/Installation_Guide/index.html#chap-installation-server-setup).

- Kickstart files—To fully automate an installation, you create what is called a kickstart file. By passing a kickstart file as a boot option to a Linux installer, you can provide answers to all the installation questions you would normally have to click through.

When you install RHEL, a kickstart file containing answers to all installation questions for the installation you just did is in the /root/anaconda-ks.cfg file. You can present that file to your next installation to repeat the installation configuration or use that file as a model for different installations.

See the RHEL Installation Guide for information on passing a kickstart file to the anaconda installer (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html-single/Installation_Guide/index.html#sect-parameter-configuration-files-kickstart-s390) and creating your own kickstart files (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/6/html-single/Installation_Guide/index.html#s1-kickstart2-file).

Exploring Common Installation Topics

Some of the installation topics touched upon earlier in this chapter require further explanation for you to be able to implement them fully. Read through the topics in this section to get a greater understanding of specific installation topics.

Upgrading or installing from scratch

If you have an earlier version of Linux already installed on your computer, Fedora, Ubuntu, and other Linux distributions offer an upgrade option. Red Hat Enterprise Linux offers a limited upgrade path from RHEL 6 to RHEL 7.

Upgrading lets you move a Linux system from one major release to the next. Between minor releases, you can simply update packages as needed (for example, by typing yum update). Here are a few general rules before performing an upgrade:

- Remove extra packages. If you have software packages you don't need, remove them before you do an upgrade. Upgrade processes typically upgrade only those packages that are on your system. Upgrades generally do more checking and comparing than clean installs do, so any package you can remove saves time during the upgrade process.

- Check configuration files. A Linux upgrade procedure often leaves copies of old configuration files. You should check that the new configuration files still work for you.

TIP

Installing Linux from scratch goes faster than an upgrade. It also results in a cleaner Linux system. So, if you don't need the data on your system (or if you have a backup of your data), I recommend you do a fresh installation. Then you can restore your data to a freshly installed system.

Some Linux distributions, most notably Gentoo, have taken the approach of providing ongoing updates. Instead of taking a new release every few months, you simply continuously grab updated packages as they become available and install them on your system.

Dual booting

It is possible to have multiple operating systems installed on the same computer. One way to do this is by having multiple partitions on a hard disk and/or multiple hard disks, and then installing different operating systems on different partitions. As long as the boot loader contains boot information for each of the installed operating systems, you can choose which one to run at boot time.

CAUTION

Although tools for resizing Windows partitions and setting up multi-boot systems have improved in recent years, there is still some risk of losing data on Windows/Linux dual-boot systems. Different operating systems often have different views of partition tables and master boot records that can cause your machine to become unbootable (at least temporarily) or lose data permanently. Always back up your data before you try to resize a Windows (NTFS or FAT) filesystem to make space for Linux.

If the computer you are using already has a Windows system on it, quite possibly the entire hard disk is devoted to Windows. Although you can run a bootable Linux, such as KNOPPIX or Damn Small Linux, without touching the hard disk, to do a more permanent installation, you'll want to find disk space outside the Windows installation. There are a few ways to do this:

- Add a hard disk. Instead of messing with your Windows partition, you can simply add a hard disk and devote it to Linux.

- Resize your Windows partition. If you have available space on a Windows partition, you can shrink that partition so free space is available on the disk to devote to Linux. Tools such as Acronis Disk Director (http://www.acronis.com) are available to resize your disk partitions and set up a workable boot manager. Some Linux distributions (particularly bootable Linuxes used as rescue CDs) include a tool called GParted (which includes software from the Linux-NTFS project for resizing Windows NTFS partitions).

NOTE

Type yum install gparted (in Fedora) or apt-get install gparted (in Ubuntu) to install GParted. Run gparted as root to start it.

Before you try to resize your Windows partition, you might need to defragment it. To defragment your disk on some Windows systems, so that all your used space is put in order on the disk, open My Computer, right-click your hard disk icon (typically C:), select Properties, click Tools, and select Defragment Now.

Defragmenting your disk can be a fairly long process. The result of defragmentation is that all the data on your disk are contiguous, creating lots of contiguous free space at the end of the partition. Sometimes, you have to complete the following special tasks to make this true:

- If the Windows swap file is not moved during defragmentation, you must remove it. Then, after you defragment your disk again and resize it, you need to restore the swap file. To remove the swap file, open the Control Panel, open the System icon, click the Performance tab, and select Virtual Memory. To disable the swap file, click Disable Virtual Memory.

- If your DOS partition has hidden files that are on the space you are trying to free up, you need to find them. In some cases, you can't delete them. In other cases, such as swap files created by a program, you can safely delete those files. This is a bit tricky because some files should not be deleted, such as DOS system files. You can use the attrib -s -h command from the root directory to deal with hidden files.

After your disk is defragmented, you can use commercial tools described earlier (Acronis Disk Director) to repartition your hard disk to make space for Linux. Or use the open source alternative GParted.

After you have cleared enough disk space to install Linux (see the disk space requirements described earlier in this chapter), you can install Ubuntu, Fedora, RHEL, or another Linux distribution. As you set up your boot loader during installation, you can identify Windows, Linux, and any other bootable partitions so you can select which one to boot when you start your computer.

Installing Linux to run virtually

Using virtualization technology, such as KVM, VMWare, VirtualBox, or Xen, you can configure your computer to run multiple operating systems simultaneously. Typically, you have a host operating system running (such as your Linux or Windows desktop), and then you configure guest operating systems to run within that environment.

If you have a Windows system, you can use commercial VMWare products to run Linux on your Windows desktop. Visit http://www.vmware.com/try-vmware to get a trial of VMWare Workstation. Then run your installed virtual guests with the free VMWare Player. With a full-blown version of VMWare Workstation, you can run multiple distributions at the same time.

Open source virtualization products that are available with Linux systems include VirtualBox (http://www.virtualbox.org), Xen (http://www.xen.org), and KVM (http://www.linux-kvm.org). VirtualBox was developed originally by Sun Microsystems. Some Linux distributions still use Xen. However, all Red Hat systems currently use KVM as the basis for Red Hat's hypervisor features in RHEL, Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization, and other cloud projects. See Chapter 26 for information on installing Linux as a virtual machine on a Linux KVM host.

Using installation boot options

When the anaconda kernel launches at boot time for RHEL or Fedora, boot options provided on the kernel command line modify the behavior of the installation process. By interrupting the boot loader before the installation kernel boots, you can add your own boot options to direct how the installation behaves.

When you see the installation boot screen, depending on the boot loader, press Tab or some other key to be able to edit the anaconda kernel command line. The line identifying the kernel might look something like the following:

vmlinuz initrd=initrd.img ...

The vmlinuz is the compressed kernel and initrd.img is the initial RAM disk (containing modules and other tools needed to start the installer). To add more options, just type them at the end of that line and press Enter.

So, for example, if you have a kickstart file available from /root/ks.cfg on a CD, your anaconda boot prompt to start the installation using the kickstart file could look like the following:

vmlinuz initrd=initrd.img ks=cdrom:/root/ks.cfg

For Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 and the latest Fedora releases, kernel boot options used during installation are transitioning to a new naming method. With this new naming, a prefix of inst. can be placed in front of any of the boot options shown in this section that are specific to the installation process (for example, inst.xdriver or inst.repo=dvd).

For the time being, however, you can still use the options shown in the next few sections with the inst. prefix.

Boot options for disabling features

Sometimes, a Linux installation fails because the computer has some non-functioning or non-supported hardware. Often, you can get around those issues by passing options to the installer that do such things as disable selected hardware when you need to select your own driver. Table 9.1 provides some examples:

TABLE 9.1 Boot Options for Disabling Features

| Installer Option | Tells System |

| nofirewire | Not to load support for firewire devices |

| nodma | Not to load DMA support for hard disks |

| noide | Not to load support for IDE devices |

| nompath | Not to enable support for multipath devices |

| noparport | Not to load support for parallel ports |

| nopcmcia | Not to load support for PCMCIA controllers |

| noprobe | Not to probe hardware, instead prompt user for drivers |

| noscsi | Not to load support for SCSI devices |

| nousb | Not to load support for USB devices |

| noipv6 | Not to enable IPV6 networking |

| nonet | Not to probe for network devices |

| numa-off | To disable the Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) for AMD64 architecture |

| acpi=off | To disable the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) |

Boot options for video problems

If you are having trouble with your video display, you can specify video settings as noted in Table 9.2.

TABLE 9.2 Boot Options for Video Problems

| Boot Option | Tells System |

| xdriver=vesa | Use standard vesa video driver |

| resolution=1024x768 | Choose exact resolution to use |

| nofb | Don't use the VGA 16 framebuffer driver |

| skipddc | Don't probe DDC of the monitor (the probe can hang the installer) |

| graphical | Force a graphical installation |

Boot options for special installation types

By default, installation runs in graphical mode with you sitting at the console answering questions. If you have a text-only console, or if the GUI isn't working properly, you can run an installation in plain-text mode: By typing text, you cause the installation to run in text mode.

If you want to start installation on one computer, but you want to answer the installation questions from another computer, you can enable a vnc (virtual network computing) installation. After you start this type of installation, you can go to another system and open a vnc viewer, giving the viewer the address of the installation machine (such as 192.168.0.99:1). Table 9.3 provides the necessary commands, along with what to tell the system to do.

TABLE 9.3 Boot Options for VNC Installations

| Boot Option | Tells System |

| vnc | Run installation as a VNC server |

| vncconnect=hostname[:port] | Connect to VNC client hostname and optional port |

| vncpassword=<password> | Client uses password (at least 8 characters) to connect to installer |

Boot options for kickstarts and remote repositories

You can boot the installation process from an installation medium that contains little more than the kernel and initial RAM disk. If that is the case, you need to identify the repository where the software packages exist. You can do that by providing a kickstart file or by identifying the location of the repositories in some way. To force the installer to prompt for the repository location (CD/DVD, hard drive, NFS, or URL), add askmethod to the installation boot options.

Using repo= options, you can identify software repository locations. The following examples show the syntax to use for creating repo= entries:

repo=hd:/dev/sda1:/myrepo Repository in /myrepo on disk 1 first partition repo=http://abc.example.com/myrepo Repository available from /myrepo on Web server repo=ftp://ftp.example.com/myrepo Repository available from /myrepo on FTP server repo=cdrom Repository available from local CD or DVD repo=nfs::mynfs.example.com:/myrepo/ Repository available from /myrepo on NFS share repo=nfsiso::nfs.example.com:/mydir/rhel7.iso Installation ISO image available from NFS server

Instead of identifying the repository directly, you can specify it within a kickstart file. The following are examples of some ways to identify the location of a kickstart file.

ks=cdrom:/stuff/ks.cfg Get kickstart from CD/DVD. ks=hd:sda2:/test/ks.cfg Get kickstart from test directory on hard disk (sda2) ks=http://www.example.com/ksfiles/ks.cfg Get kickstart from a Web server. ks=ftp://ftp.example.com/allks/ks.cfg Get kickstart from a FTP server. ks=nfs:mynfs.example.com:/someks/ks.cfg Get kickstart from an NFS server.

Miscellaneous boot options

Here are a few other options you can pass to the installer that don't fit in a category.

rescue Instead of installing, run the kernel to open Linux rescue mode. mediacheck Check the installation CD/DVD for checksum errors.

For further information on using the anaconda installer in rescue mode (to rescue a broken Linux system), see Chapter 21, “Troubleshooting Linux.” For information on the latest boot options use in RHEL 7, refer to the RHEL 7 Installation Guide (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html-single/Installation_Guide/index.html#chap-anaconda-boot-options).

Using specialized storage

In large enterprise computing environments, it is common to store the operating system and data outside the local computer. Instead, some special storage device beyond the local hard disk is identified to the installer, and that storage device (or devices) can be used during installation.

Once identified, the storage devices you indicate during installation can be used the same way that local disks are used. You can partition them and assign a structure (filesystem, swap space, and so on) or leave them alone and simply mount them where you want the data to be available.

The following types of specialized storage devices can be selected from the Specialized Storage Devices screen when you install Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Fedora, or other Linux distributions:

- Firmware RAID—A firmware RAID device is a type of device that has hooks in the BIOS, allowing it to be used to boot the operating system, if you choose.

- Multipath devices—As the name implies, multipath devices provide multiple paths between the computer and its storage devices. These paths are aggregated, so these devices look like a single device to the system using them, while the underlying technology provides improved performance, redundancy, or both. Connections can be provided by iSCSI or Fibre Channel over Ethernet (FCoE) devices.

- Other SAN devices—Any device representing a Storage Area Network (SAN).

While configuring these specialized storage devices is beyond the scope of this book, know that if you are working in an enterprise where iSCSI and FCoE devices are available, you can configure your Linux system to use them at installation time. The types of information you need to do this include:

- iSCSI devices—Have your storage administrator provide you with the target IP address of the iSCSI device and the type of discovery authentication needed to use the device. The iSCSI device may require credentials.

- Fibre Channel over Ethernet Devices (FCoE)—For FCoE, you need to know the network interface that is connected to your FCoE switch. You can search that interface for available FCoE devices.

Partitioning hard drives

The hard disk (or disks) on your computer provide the permanent storage area for your data files, application programs, and the operating system itself. Partitioning is the act of dividing a disk into logical areas that can be worked with separately. In Windows, you typically have one partition that consumes the whole hard disk. However, with Linux there are several reasons why you may want to have multiple partitions:

- Multiple operating systems—If you install Linux on a PC that already has a Windows operating system, you may want to keep both operating systems on the computer. For all practical purposes, each operating system must exist on a completely separate partition. When your computer boots, you can choose which system to run.

- Multiple partitions within an operating system—To protect their entire operating system from running out of disk space, people often assign separate partitions to different areas of the Linux filesystem. For example, if /home and /var were assigned to separate partitions, then a gluttonous user who fills up the /home partition wouldn't prevent logging daemons from continuing to write to log files in the /var/log directory.

Multiple partitions also make doing certain kinds of backups (such as an image backup) easier. For example, an image backup of /home would be much faster (and probably more useful) than an image backup of the root filesystem (/).

- Different filesystem types—Different kinds of filesystems have different structures. Filesystems of different types must be on their own partitions. Also, you might need different filesystems to have different mount options for special features (such as read-only or user quotas). In most Linux systems, you need at least one filesystem type for the root of the filesystem (/) and one for your swap area. Filesystems on CD-ROM use the iso9660 filesystem type.

TIP

When you create partitions for Linux, you usually assign the filesystem type as Linux native (using the ext2, ext3, ext4, or xfs type on most Linux systems). If the applications you are running require particularly long filenames, large file sizes, or many inodes (each file consumes an inode), you may want to choose a different filesystem type.

For example, if you set up a news server, it can use many inodes to store small news articles. Another reason for using a different filesystem type is to copy an image backup tape from another operating system to your local disk (such as a legacy filesystem from an OS/2 or Minix operating system).

Coming from Windows

If you have only used Windows operating systems before, you probably had your whole hard disk assigned to C: and never thought about partitions. With many Linux systems, you have the opportunity to view and change the default partitioning based on how you want to use the system.

During installation, systems such as Fedora and RHEL let you partition your hard disk using graphical partitioning tools. The following sections describe how to partition your disk during a Fedora installation. See the section “Tips for creating partitions” for some ideas for creating disk partitions.

Understanding different partition types

Many Linux distributions give you the option of selecting different partition types when you partition your hard disk during installation. Partition types include:

- Linux partitions—Use this option to create a partition for an ext2, ext3, or ext4 filesystem type that is added directly to a partition on your hard disk (or other storage medium). The xfs filesystem type can also be used on a Linux partition.

- LVM partitions—Create an LVM partition if you plan to create or add to an LVM volume group. LVMs give you more flexibility in growing, shrinking, and moving partitions later than regular partitions do.

- RAID partitions—Create two or more RAID partitions to create a RAID array. These partitions should be on separate disks to create an effective RAID array.

RAID arrays can help improve performance, reliability, or both as those features relate to reading, writing, and storing your data.

- Swap partitions—Create a swap partition to extend the amount of virtual memory available on your system.

The following sections describe how to add regular Linux partitions, LVM, RAID, and swap partitions using the Fedora graphical installer. If you are still not sure when you should use these different partition types, refer to Chapter 12 for further information on configuring disk partitions.

Reasons for different partitioning schemes

Different opinions exist relating to how to divide up a hard disk. Here are some issues to consider:

- Do you want to install another operating system? If you want Windows on your computer along with Linux, you need at least one Windows (Win95, FAT16, VFAT, or NTFS type), one Linux (Linux ext4 or xfs), and usually one Linux swap partition.

- Is it a multiuser system? If you are using the system yourself, you probably don't need many partitions. One reason for partitioning an operating system is to keep the entire system from running out of disk space at once. That also serves to put boundaries on what an individual can use up in his or her home directory (although disk quotas provide a more refined way of limiting disk use).

- Do you have multiple hard disks? You need at least one partition per hard disk. If your system has two hard disks, you may assign one to / and one to /home (if you have lots of users) or /var (if the computer is a server sharing lots of data). With a separate /home partition, you can install another Linux system in the future without disturbing your home directories (and presumably all or most of your user data).

Tips for creating partitions

Changing your disk partitions to handle multiple operating systems can be very tricky, in part because each operating system has its own ideas about how partitioning information should be handled, as well as different tools for doing it. Here are some tips to help you get it right:

- If you are creating a dual-boot system, particularly for a Windows system, try to install the Windows operating system first after partitioning your disk. Otherwise, the Windows installation may make the Linux partitions inaccessible. Choosing a VFAT instead of NTFS filesystem for Windows also makes sharing files between your Windows and Linux systems easier and more reliable. (Support for NTFS partitions from Linux has improved greatly in the past few years, but not all Linux systems include NTFS support.)

- The fdisk man page recommends that you use partitioning tools that come with an operating system to create partitions for that operating system. For example, the DOS fdisk knows how to create partitions that DOS will like, and the Linux fdisk will happily make your Linux partitions. After your hard disk is set up for dual boot, however, you should probably not go back to Windows-only partitioning tools. Use Linux fdisk or a product made for multi-boot systems (such as Acronis Disk Director).

- You can have up to 63 partitions on an IDE hard disk. A SCSI hard disk can have up to 15 partitions. You typically won't need nearly that many partitions. If you need more partitions, use LVM and create as many logical volumes as you like.

If you are using Linux as a desktop system, you probably don't need lots of different partitions. However, some very good reasons exist for having multiple partitions for Linux systems that are shared by lots of users or are public web servers or file servers. Having multiple partitions within Fedora or RHEL, for example, offers the following advantages:

- Protection from attacks—Denial-of-service attacks sometimes take actions that try to fill up your hard disk. If public areas, such as /var, are on separate partitions, a successful attack can fill up a partition without shutting down the whole computer. Because /var is the default location for web and FTP servers, and is expected to hold lots of data, entire hard disks often are assigned to the /var filesystem alone.

- Protection from corrupted filesystems—If you have only one filesystem (/), its corruption can cause the whole Linux system to be damaged. Corruption of a smaller partition can be easier to fix and often allows the computer to stay in service while the correction is made.

Table 9.4 lists some directories that you may want to consider making into separate filesystem partitions.

TABLE 9.4 Assigning Partitions to Particular Directories

Although people who use Linux systems casually rarely see a need for lots of partitions, those who maintain and occasionally have to recover large systems are thankful when the system they need to fix has several partitions. Multiple partitions can limit the effects of deliberate damage (such as denial-of-service attacks), problems from errant users, and accidental filesystem corruption.

Using the GRUB boot loader

A boot loader lets you choose when and how to boot the operating systems installed on your computer's hard disks. The GRand Unified Bootloader (GRUB) is the most popular boot loader used for installed Linux systems. There are two major versions of GRUB available today:

- GRUB Legacy (version 1)—As of this writing, this version of GRUB is used by default to boot Red Hat Enterprise Linux operating systems (at least through RHEL 6.5). It was also used with earlier versions of Fedora and Ubuntu.

- GRUB 2—The current versions of Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Ubuntu, and Fedora use GRUB 2 as the default boot loader.

The GRUB Legacy version is described in the following sections. After that, there is a description of GRUB 2.

NOTE

SYSLINUX is another boot loader you will encounter with Linux systems. The SYSLINUX boot loaders are not typically used for installed Linux systems. However, SYSLINUX is commonly used as the boot loader for Linux CDs and DVDs. SYSLINUX is particularly good for booting ISO9660 CD images (isolinux) and USB sticks (syslinux), and for working on older hardware or for PXE booting (pxelinux) a system over the network.

Using GRUB Legacy (version 1)

With multiple operating systems installed and several partitions set up, how does your computer know which operating system to start? To select and manage which partition is booted and how it is booted, you need a boot loader. The boot loader that is installed by default with Red Hat Enterprise Linux systems is the GRand Unified Boot loader (GRUB).

GRUB Legacy is a GNU boot loader (http://www.gnu.org/software/grub) that offers the following features:

- Support for multiple executable formats.

- Support for multi-boot operating systems (such as Fedora, RHEL, FreeBSD, NetBSD, OpenBSD, and other Linux systems).

- Support for non-multi-boot operating systems (such as Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows NT, Windows ME, Windows XP, Windows Vista, Windows 7, and OS/2) via a chain-loading function. Chain-loading is the act of loading another boot loader (presumably one that is specific to the proprietary operating system) from GRUB to start the selected operating system.

- Support for multiple filesystem types.

- Support for automatic decompression of boot images.

- Support for downloading boot images from a network.

At the time of this writing, GRUB version 1 is used in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6. GRUB version 2 is used in Fedora, Ubuntu, Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, and other Linux distributions. This section describes how to use GRUB version 1.

For more information on how GRUB works, at the command line type man grub or info grub. The info grub command contains more details about GRUB.

Booting with GRUB Legacy

When you install Linux, you are typically given the option to configure the information needed to boot your computer (with one or more operating systems) into the default boot loader. GRUB is very flexible to configure, so it looks different in different Linux distributions.

With the GRUB boot loader that comes with Red Hat Enterprise Linux installed in the master boot record of your hard disk, when the BIOS starts up the boot loader one of several things can happen:

- Default—If you do nothing, the default operating system boots automatically after five seconds. (The timeout is set by the timeout value, in seconds, in the grub. conf or menu. lst file.)

- Select an operating system—Press any key before the five seconds expires, and you see a list of titles to select from. The titles can represent one or more kernels for the same Linux system. Or they may represent Windows, Ubuntu, or other operating systems. Use the up and down arrow keys to highlight any title, and press Enter to boot that operating system.

- Edit the boot process—If you want to change any of the options used during the boot process, use the arrow keys to highlight the operating system you want and type e to select it. Follow the next procedure to change your boot options temporarily.

If you want to change your boot options so they take effect every time you boot your computer, see the section on permanently changing boot options. Changing those options involves editing the /boot/grub/grub.conf file.

Temporarily changing boot options

From the GRUB Legacy boot screen, you can select to change or add boot options for the current boot session. On some Linux systems, the menu is hidden, so you have to press the Tab key or some other key (before a few seconds of timeout is exceeded) to see the menu. Then select the operating system you want (using the arrow keys), and type e (as described earlier).

Three lines in the example of the GRUB Legacy editing screen identify the boot process for the operating system you chose. Here is an example of those lines (because of the length of the kernel line, it is represented here as three lines):

root (hd0,0)

kernel /vmlinuz-2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64 ro

root=/dev/mapper/vg_myhost-lv_root

rd_NO_MD rd_NO_DM

LANG=en_US.UTF-8 SYSFONT=latarcyrheb-sun16 KEYBOARDTYPE=pc

KEYTABLE=us rhgb quiet crashkernel=auto

initrd /initramfs-2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64.img

The first line (beginning with root) shows that the entry for the GRUB boot loader is on the first partition of the first hard disk (hd0,0). GRUB represents the hard disk as hd, regardless of whether it is a SCSI, IDE, or other type of disk. In GRUB Legacy, you just count the drive number and partition number, starting from zero (0).

The second line of the example (beginning with kernel) identifies the kernel boot image (/boot/vmlinuz-2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64) and several options. The options identify the partition as initially being loaded ro (read-only) and the location of the root filesystem on a partition with the label that begins root=/dev/mapper/vg_myhost-lv_ root. The third line (starting with initrd) identifies the location of the initial RAM disk, which contains additional modules and tools needed during the boot process.

If you are going to change any of the lines related to the boot process, you will probably change only the second line to add or remove boot options. Follow these steps to do just that:

- After interrupting the GRUB boot process and typing e to select the boot entry you want, position the cursor on the kernel line and type e.

- Either add or remove options after the name of the boot image. You can use a minimal set of bash shell command-line editing features to edit the line. You can even use command completion (type part of a filename and press Tab to complete it). Here are a few options you may want to add or delete:

- Boot to a shell. If you forgot your root password or if your boot process hangs, you can boot directly to a shell by adding init=/bin/sh to the boot line.

- Select a run level. If you want to boot to a particular run level, you can add the run level you want to the end of the kernel line. For example, to have RHEL boot to run level 3 (multiuser plus networking mode), add 3 to the end of the kernel line. You can also boot to single-user mode (1), multiuser mode (2), or X GUI mode (5). Level 3 is a good choice if your GUI is temporarily broken. Level 1 is good if you have forgotten your root password.

- Watch boot messages. By default, you will see a splash screen as Linux boots. If you want to see messages showing activities happening as the system boots up, you can remove the option rhgb quiet from the kernel line. This lets you see messages as they scroll by. Pressing Esc during boot-up gets the same result.

- Press Enter to return to the editing screen.

- Type b to boot the computer with the new options. The next time you boot your computer, the new options will not be saved. To add options so they are saved permanently, see the next section.

Permanently changing boot options

You can change the options that take effect each time you boot your computer by changing the GRUB configuration file. In RHEL and other Linux systems, GRUB configuration centers on the /boot/grub/grub.conf or /boot/grub/menu.lst file.

The /boot/grub/grub.conf file is created when you install Linux. Here's an example of that file for RHEL:

# grub.conf generated by anaconda # # Note you do not have to rerun grub after making changes to the file # NOTICE: You have a /boot partition. This means that # all kernel and initrd paths are relative to /boot/, eg. # root (hd0,0) # kernel /vmlinuz-version ro root=/dev/mapper/vg_joke-lv_root # initrd /initrd-[generic-]version.img #boot=/dev/sda default=0 timeout=5 splashimage=(hd0,0)/grub/splash.xpm.gz

hiddenmenu title Red Hat Enterprise Linux (2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64) root (hd0,0) kernel /vmlinuz-2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64 ro root=/dev/mapper/vg_myhost-lv_root rd_NO_MD rd_NO_DM LANG=en_US.UTF-8 SYSFONT=latarcyrheb-sun16 KEYBOARDTYPE=pc KEYTABLE=us rhgb quiet crashkernel=auto initrd /initramfs-2.6.32-131.17.1.el6.x86_64.img title Windows XP rootnoverify (hd0,1) chainloader +1

The default=0 line indicates that the first partition in this list (in this case, Red Hat Enterprise Linux) is booted by default. The line timeout=5 causes GRUB to pause for five seconds before booting the default partition. (That's how much time you have to press e if you want to edit the boot line, or to press arrow keys to select a different operating system to boot.)

The splashimage line looks in the first partition on the first disk (hd0, 0) for the boot partition (in this case /dev/sda1). GRUB loads splash.xpm.gz as the image on the splash screen (/boot/grub/splash.xpm.gz). The splash screen appears as the background of the boot screen.

NOTE

GRUB indicates disk partitions using the following notation: (hd0,0). The first number represents the disk, and the second is the partition on that disk. So (hd0,1) is the second partition (1) on the first disk (0).

The two bootable partitions in this example are Red Hat Enterprise Linux and Windows XP. The title lines for each of those partitions are followed by the name that appears on the boot screen to represent each partition.

For the RHEL system, the root line indicates the location of the boot partition as the second partition on the first disk. So, to find the bootable kernel (vmlinuz-*) and the initrd initial RAM disk boot image that is loaded (initrd-*), GRUB mounts hd0,0 as the root of the entire filesystem (represented by /dev/mapper/vg_myhost-lv_root and mounted as /). There are other options on the kernel line as well.

For the Windows XP partition, the rootnoverify line indicates that GRUB should not try to mount the partition. In this case, Windows XP is on the first partition of the first hard disk (hd0,1) or /dev/sda2. Instead of mounting the partition and passing options to the new operating system, the chainloader +1 line tells GRUB to pass the booting of the operating system to another boot loader. The +1 indicates that the first sector of the partition is used as the boot loader. (You could similarly set up to boot a Windows Vista or Windows 7 operating system.)

Microsoft operating systems require that you use the chainloader to boot them from GRUB because GRUB doesn't offer native support for Windows operating systems.

If you make any changes to the /boot/grub/grub.conf file, you do not need to load those changes. GRUB automatically picks up those changes when you reboot your computer.

Adding a new GRUB boot image

You may have different boot images for kernels that include different features. In most cases, installing a new kernel package automatically configures grub.conf to use that new kernel. However, if you want to manually add a kernel, here is the procedure for modifying the grub.conf file in Red Hat Enterprise Linux to be able to boot that kernel:

- Copy the new image from the directory in which it was created (such as /usr/src/kernels/linux-2.6.25-11/arch/i386/boot)to the /boot directory. Name the file something that reflects its contents, such as bz-2.6.25-11. For example:

# cd /usr/src/Linux-2.6.25.11/arch/i386/boot # cp bzImage /boot/bz-2.6.25-11

- Add several lines to the /boot/grub/grub.conf file so that the image can be started at boot time if it is selected. For example:

title Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.3 (My own IPV6 build) root (hd0,4) kernel /bz-2.6.25-11 ro root=/dev/sda5 initrd /initrd-2.6.25-11.img

- Reboot your computer.

- When the GRUB boot screen appears, move your cursor to the title representing the new kernel and press Enter.

The advantage to this approach, as opposed to copying the new boot image over the old one, is that if the kernel fails to boot, you can always go back and restart the old kernel. When you feel confident that the new kernel is working properly, you can use it to replace the old kernel or perhaps just make the new kernel the default boot definition.

Using GRUB 2

GRUB 2 represents a major rewrite of the GRUB Legacy project. It has been adopted as the default boot loader for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, Fedora, and Ubuntu. The major function of the GRUB 2 boot loader is still to find and start the operating system you want, but now much more power and flexibility is built into the tools and configuration files that get you there.

In GRUB 2, the configuration file is now named /boot/grub2/grub.cfg (in Fedora and other Linux systems using GRUB 2). Everything from the contents of grub.cfg to the way grub.cfg is created is different from the GRUB Legacy grub.conf file. Here are some things you should know about the grub.cfg file:

- Instead of editing grub.cfg by hand or having kernel RPM packages add to it, grub.cfg is generated from the contents of the /etc/default/grub file and the /etc/grub.d directory. You should modify or add to those files to configure GRUB 2 yourself.

- The grub.cfg file can contain scripting syntax, including such things as functions, loops, and variables.

- Device names needed to identify the location of kernels and initial RAM disks can be more reliably identified using labels or Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs). This prevents the possibility of a disk device such as /dev/sda being changed to /dev/sdb when you add a new disk (which would result in the kernel not being found).

Comments in the grub.cfg file indicate where the content came from. For example, information generated from the /etc/grub.d/00_header file comes right after this comment line:

### BEGIN /etc/grub.d/00_header ###

In the beginning of the 00_header section, there are some functions, such as those that load drivers to get your video display to work. After that, most of the sections in the grub.cfg file consist of menu entries. The following is an example of a menu item from the grub.cfg file that you could select to start Fedora 20 when the system boots up:

menuentry 'Fedora (3.16.3-200.fc20.x86_64)' --class fedora

--class gnu-linux --class gnu --class os ...{

load_video

set gfxpayload=keep

insmod gzio

insmod part_msdos

insmod ext2

set root='(hd0,msdos1)'

search --no-floppy --fs-uuid --set=root

eb31517f-f404-410b-937e-a6093b5a5380

linux /vmlinuz-3.16.3-200.fc20.x86_64

root=/dev/mapper/fedora_fedora20-root ro

rd.lvm.lv=fedora_fedora20/swap

vconsole.font=latarcyrheb-sun16

rd.lvm.lv=fedora_fedora20/root rhgb quiet

LANG=en_US.UTF-8

initrd /initramfs-3.16.3-200.fc20.x86_64.img

}

The menu entry for this selection appears as Fedora (3.16.3-200.fc20.x86_64) on the GRUB 2 boot menu. The --class entries on that line allow GRUB 2 to group the menu entries into classes (in this case, it identifies it as a fedora, gnu-linux, gnu, os type of system). The next lines load video drivers and file system drivers. After that, lines identify the location of the root file system.

The linux line shows the kernel location (/boot/vmlinuz-3.16.3-200.fc20.x86_64), followed by options that are passed to the kernel.

There are many, many more features of GRUB 2 you can learn about if you want to dig deeper into your system's boot loader. The best documentation for GRUB 2 is available on the Fedora system; type info grub2 at the shell. The info entry for GRUB 2 provides lots of information for booting different operating systems, writing your own configuration files, working with GRUB image files, setting GRUB environment variables, and working with other GRUB features.

Summary

Although every Linux distribution includes a different installation method, you need to do many common activities, regardless of which Linux system you install. For every Linux system, you need to deal with issues of disk partitioning, boot options, and configuring boot loaders.

In this chapter, you stepped through installation procedures for Fedora (using a live media installation) and Red Hat Enterprise (from installation media). You learned how deploying Linux in cloud environments can differ from traditional installation methods by combining metadata with prebuilt base operating system image files to run on large pools of compute resources.

The chapter also covered special installation topics, including using boot options and disk partitioning. With your Linux system now installed, Chapter 10 describes how to begin managing the software on your Linux system.

Exercises

Use these exercises to test your knowledge of installing Linux. I recommend you do these exercises on a computer that has no operating system or data on it that you would fear losing (in other words, one you don't mind erasing). If you have a computer that allows you to install virtual systems, that is a safe way to do these exercises as well. These exercises were tested using a Fedora 21 Live media and an RHEL 7 Server Installation DVD.

- Start installing from Fedora Live media, using as many of the default options as possible.

- After you have completely installed Fedora, update all the packages on the system.

- Start installing from an RHEL installation DVD, but make it so the installation runs in text mode. Complete the installation in any way you choose.

- Start installing from an RHEL installation DVD, and set the disk partitioning as follows: a 400MB /boot, / (3GB), /var (2GB), and /home (2GB). Leave the rest as unused space.

CAUTION

Completing Exercise 4 ultimately deletes all content on your hard disk. If you want to use this exercise only to practice partitioning, you can reboot your computer before clicking Accept Changes at the very end of this procedure without harming your hard disk. If you go forward and partition your disk, assume that all data that you have not explicitly changed has been deleted.