Published by

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

10475 Crosspoint Boulevard

Indianapolis, IN 46256

Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN: 978-1-118-99987-5

ISBN: 978-1-118-99989-9 (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-118-99988-2 (ebk)

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION OR WEB SITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FURTHER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFORMATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE. FURTHER, READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT INTERNET WEBSITES LISTED IN THIS WORK MAY HAVE CHANGED OR DISAPPEARED BETWEEN WHEN THIS WORK WAS WRITTEN AND WHEN IT IS READ.

For general information on our other products and services please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (877) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937667

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates, in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. Linux is a registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Chris Negus is a Red Hat Certified Instructor (RHCI), Red Hat Certified Examiner (RHCX), Red Hat Certified Architect (RHCA), and Principal Technical Writer for Red Hat Inc. In more than six years with Red Hat, Chris has taught hundreds of IT professionals aspiring to become Red Hat Certified Engineers (RHCE).

In his current position at Red Hat, Chris produces articles for the Red Hat Customer Portal. The projects he works on include Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, Red Hat Enterprise OpenStack Platform, Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization and Linux containers in Docker format.

Besides his RHCA certification, Chris is a Red Hat Certified Virtualization Administrator (RHCVA) and Red Hat Certified Datacenter Specialist (RHCDS). He also has certificates of expertise in Deployment and Systems Management, Clustering and Storage Management, Cloud Storage, and Server Hardening.

Before joining Red Hat, Chris wrote or co-wrote dozens of books on Linux and UNIX, including Red Hat Linux Bible (all editions), CentOS Bible, Fedora Bible, Linux Troubleshooting Bible, Linux Toys and Linux Toys II. Chris also co-authored several books for the Linux Toolbox series for power users: Fedora Linux Toolbox, SUSE Linux Toolbox, Ubuntu Linux Toolbox, Mac OS X Toolbox, and BSD UNIX Toolbox.

For eight years Chris worked with the organization at AT&t that developed UNIX before moving to Utah to help contribute to Novell's UnixWare project in the early 1990s. When not writing about Linux, Chris enjoys playing soccer and just hanging out with his wife, Sheree, and son, Seth.

Richard Blum, LPIC-1, has worked in the IT industry for more than 20 years as both a systems and network administrator and has published numerous Linux and open source books. He has administered UNIX, Linux, Novell, and Microsoft servers, as well as helped design and maintain a 3,500-user network utilizing Cisco switches and routers. He has used Linux servers and shell scripts to perform automated network monitoring and has written shell scripts in most of the common Linux shell environments. Rich is an online instructor for an Introduction to Linux course that is used by colleges and universities across the United States. When he isn't being a computer nerd, Rich plays electric bass in a couple of different church worship bands, and enjoys spending time with his wife, Barbara, and two daughters, Katie Jane and Jessica.

Project Editor

Martin V. Minner

Technical Editor

Richard Blum

Production Manager

Kathleen Wisor

Copy Editor

Gwenette Gaddis

Manager of Content Development & Assembly

Mary Beth Wakefield

Marketing Director

David Mayhew

Marketing Manager

Carrie Sherrill

Professional Technology & Strategy Director

Barry Pruett

Business Manager

Amy Knies

Associate Publisher

Jim Minatel

Project Coordinator, Cover

Brent Savage

Proofreader

Amy Schneider

Indexer

John Sleeva

Cover Designer

Wiley

Since I was hired by Red Hat Inc. more than six years ago, I have been exposed to many of the best Linux developers, testers, support professionals and instructors in the world. Since I can't thank everyone individually, I instead salute the culture of cooperation and excellence that serves to improve my own Linux skills every day.

I don't speak well of Red Hat because I work there; I work at Red Hat because it lives up to the ideals of open source software in ways that match my own beliefs. There are a few people at Red Hat I would like to acknowledge particularly. Discussions with Victor Costea, Andrew Blum, and other Red Hat instructors have helped me adapt my ways of thinking about how people learn Linux. I'm able to work across a wide range of technologies because of the great support I get from my supervisor, Adam Strong, and my senior manager, Sam Knuth, who both point me toward cool projects but never hold me back.

In this edition, particular help came from Ryan Sawhill Aroha, who helped me simplify my writing on encryption technology. For the new content I wrote in this book on Linux cloud technologies, I'd like to thank members of OpenStack, Docker, and RHEV teams, who help me learn cutting-edge cloud technology every day.

As for the people at Wiley, thanks for letting me continue to develop and improve this book over the years. Marty Minner has helped keep me on task through a demanding schedule. Mary Beth Wakefield and Ken Brown have been there to remind me at the times I forgot it was a demanding schedule. Thanks to Richard Blum for his reliably thorough job of tech editing. Thanks to Margot Maley Hutchison from Waterside Productions for contracting the book for me with Wiley and always looking out for my best interests.

Finally, thanks to my wife, Sheree, for sharing her life with me and doing such a great job raising Seth and Caleb.

Chapter 1: Starting with Linux

Chapter 2: Creating the Perfect Linux Desktop

Part II: Becoming a Linux Power User

Chapter 4: Moving around the Filesystem

Chapter 5: Working with Text Files

Chapter 6: Managing Running Processes

Chapter 7: Writing Simple Shell Scripts

Part III: Becoming a Linux System Administrator

Chapter 8: Learning System Administration

Chapter 10: Getting and Managing Software

Chapter 11: Managing User Accounts

Chapter 12: Managing Disks and Filesystems

Part IV: Becoming a Linux Server Administrator

Chapter 13: Understanding Server Administration

Chapter 14: Administering Networking

Chapter 15: Starting and Stopping Services

Chapter 16: Configuring a Print Server

Chapter 17: Configuring a Web Server

Chapter 18: Configuring an FTP Server

Chapter 19: Configuring a Windows File Sharing (Samba) Server

Chapter 20: Configuring an NFS File Server

Chapter 21: Troubleshooting Linux

Part V: Learning Linux Security Techniques

Chapter 22: Understanding Basic Linux Security

Chapter 23: Understanding Advanced Linux Security

Chapter 24: Enhancing Linux Security with SELinux

Chapter 25: Securing Linux on a Network

Part VI: Extending Linux into the Cloud

Chapter 26: Using Linux for Cloud Computing

Chapter 1: Starting with Linux

Understanding How Linux Differs from Other Operating Systems

Free-flowing UNIX culture at Bell Labs

Berkeley Software Distribution arrives

UNIX Laboratory and commercialization

GNU transitions UNIX to freedom

Linus builds the missing piece

Understanding How Linux Distributions Emerged

Choosing a Red Hat distribution

Using Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Choosing Ubuntu or another Debian distribution

Finding Professional Opportunities with Linux Today

Understanding how companies make money with Linux

Chapter 2: Creating the Perfect Linux Desktop

Understanding Linux Desktop Technology

Starting with the Fedora GNOME Desktop Live image

Setting up the GNOME 3 desktop

Starting with desktop applications

Managing files and folders with Nautilus

Installing and managing additional software

Using the Metacity window manager

Using the Applications and System menus

Adding an application launcher

Part II: Becoming a Linux Power User

About Shells and Terminal Windows

Recalling Commands Using Command History

Connecting and Expanding Commands

Expanding arithmetic expressions

Creating Your Shell Environment

Getting Information about Commands

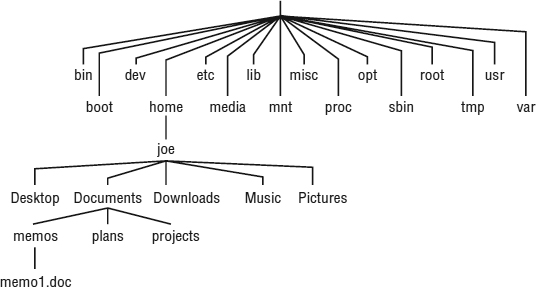

Chapter 4: Moving around the Filesystem

Using Basic Filesystem Commands

Using Metacharacters and Operators

Using file-matching metacharacters

Using file-redirection metacharacters

Using brace expansion characters

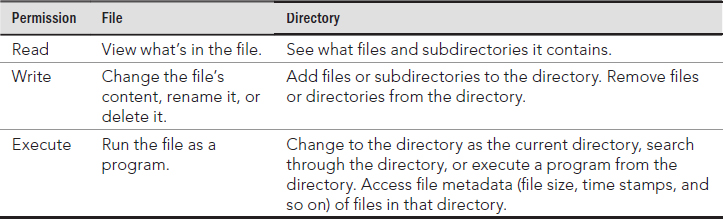

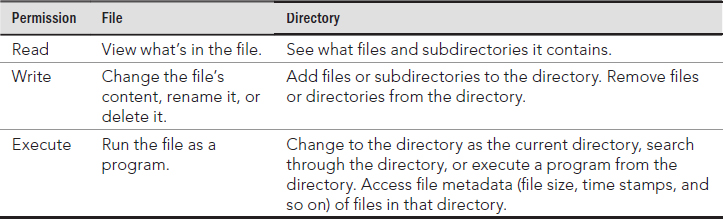

Understanding File Permissions and Ownership

Changing permissions with chmod (numbers)

Changing permissions with chmod (letters)

Setting default file permission with umask

Moving, Copying, and Removing Files

Chapter 5: Working with Text Files

Deleting, copying, and changing text

Learning more about vi and vim

Using locate to find files by name

Finding files by date and time

Using ‘not’ and ‘or’ when finding files

Finding files and executing commands

Chapter 6: Managing Running Processes

Listing and changing processes with top

Listing processes with System Monitor

Managing Background and Foreground Processes

Using foreground and background commands

Killing and Renicing Processes

Killing processes with kill and killall

Using kill to signal processes by PID

Using killall to signal processes by name

Setting processor priority with nice and renice

Limiting Processes with cgroups

Chapter 7: Writing Simple Shell Scripts

Executing and debugging shell scripts

Special shell positional parameters

Performing arithmetic in shell scripts

Using programming constructs in shell scripts

The “while...do” and “until...do” loops

Trying some useful text manipulation programs

The general regular expression parser

Remove sections of lines of text (cut)

Translate or delete characters (tr)

Part III: Becoming a Linux System Administrator

Chapter 8: Learning System Administration

Understanding System Administration

Using Graphical Administration Tools

Using browser-based admin tools

Becoming root from the shell (su command)

Allowing administrative access via the GUI

Gaining administrative access with sudo

Exploring Administrative Commands, Configuration Files, and Log Files

Administrative configuration files

Administrative log files and systemd journal

Using journalctl to view the systemd journal

Managing log messages with rsyslogd

Using Other Administrative Accounts

Checking and Configuring Hardware

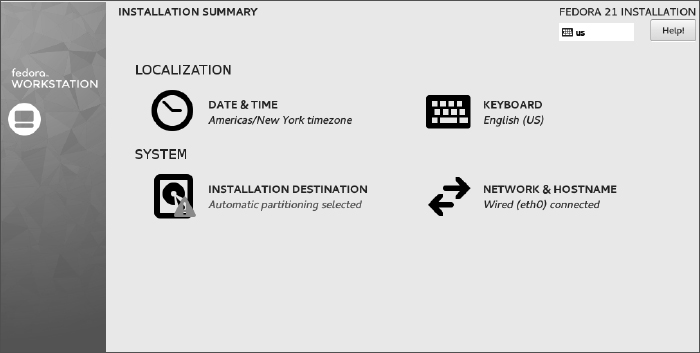

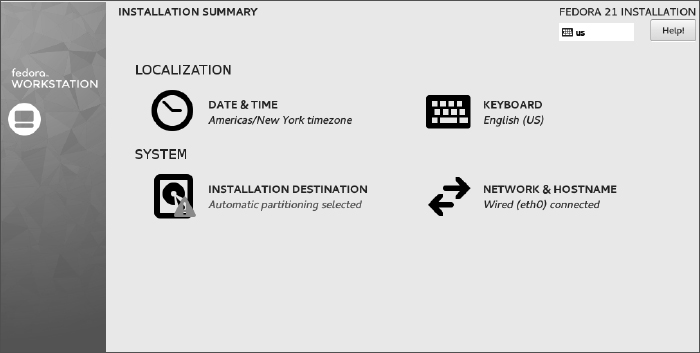

Installing Fedora from Live media

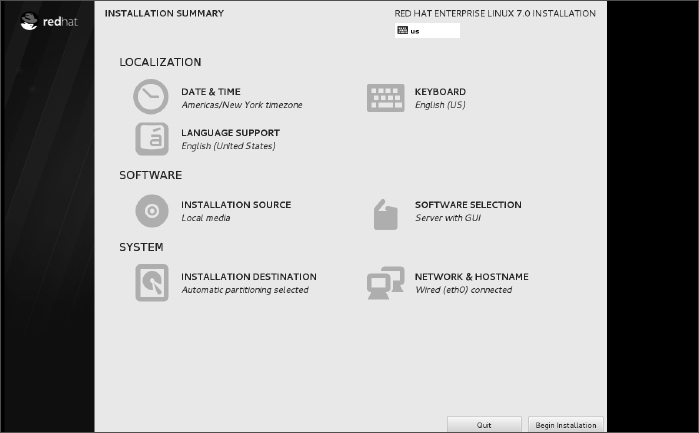

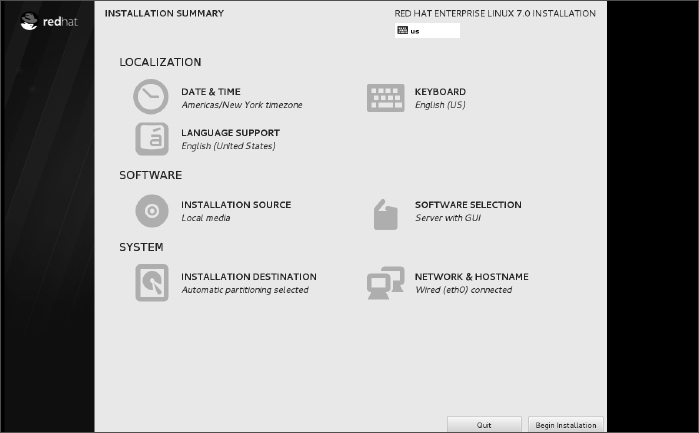

Installing Red Hat Enterprise Linux from Installation Media

Understanding Cloud-Based Installations

Installing Linux in the Enterprise

Exploring Common Installation Topics

Upgrading or installing from scratch

Installing Linux to run virtually

Using installation boot options

Boot options for disabling features

Boot options for video problems

Boot options for special installation types

Boot options for kickstarts and remote repositories

Understanding different partition types

Reasons for different partitioning schemes

Chapter 10: Getting and Managing Software

Managing Software on the Desktop

Going Beyond the Software Window

Understanding Linux RPM and DEB Software Packaging

Managing RPM Packages with YUM

2. Checking /etc/sysconfig/rhn/up2date (RHEL only)

3. Checking /etc/yum.repos.d/*.repo files

4. Downloading RPM packages and metadata from a YUM repository

5. RPM packages installed to Linux file system

6. Store YUM repository metadata to local RPM database

Using YUM with third-party software repositories

Managing software with the YUM command

Installing and removing packages

Maintaining your RPM package database and cache

Downloading RPMs from a yum repository

Installing, Querying, and Verifying Software with the rpm Command

Installing and removing packages with rpm

Managing Software in the Enterprise

Chapter 11: Managing User Accounts

Managing Users in the Enterprise

Setting permissions with Access Control Lists

Adding directories for users to collaborate

Creating group collaboration directories (set GID bit)

Creating restricted deletion directories (sticky bit)

Using the Authentication Configuration window

Chapter 12: Managing Disks and Filesystems

Understanding partition tables

Creating a single-partition disk

Creating a multiple-partition disk

Using Logical Volume Management Partitions

Using the fstab file to define mountable file systems

Using the mount command to mount file systems

Mounting a disk image in loopback

Using the mkfs Command to Create a Filesystem

Part IV: Becoming a Linux Server Administrator

CHAPTER 13: Understanding Server Administration

Starting with Server Administration

Checking the default configuration

Security settings in configuration files

Keep system software up to date

Check the filesystem for signs of crackers

Managing Remote Access with the Secure Shell Service

Starting the openssh-server service

Using ssh for remote execution

Copying files between systems with scp and rsync

Using key-based (passwordless) authentication

Enabling system logging with rsyslog

Understanding the rsyslog.conf file

Understanding the messages log file

Setting up and using a loghost with rsyslogd

Checking System Resources with sar

Displaying system space with df

Finding disk consumption with find

Managing Servers in the Enterprise

Chapter 14: Administering Networking

Configuring Networking for Desktops

Checking your network interfaces

Checking your network from NetworkManager

Checking your network from the command line

Configuring network interfaces

Configuring a network proxy connection

Configuring Networking from the Command Line

Understanding networking configuration files

Setting alias network interfaces

Setting up Ethernet channel bonding

Configuring Networking in the Enterprise

Configuring Linux as a DHCP server

Configuring Linux as a DNS server

Configuring Linux as a proxy server

Chapter 15: Starting and Stopping Services

Understanding the Initialization Daemon (init or systemd)

Understanding the classic init daemons

Understanding the Upstart init daemon

Learning Upstart init daemon basics

Learning Upstart's backward compatibility to SysVinit

Understanding systemd initialization

Learning systemd's backward compatibility to SysVinit

Checking the Status of Services

Checking services for SysVinit systems

Checking services for Upstart systems

Checking services for systemd systems

Stopping and Starting Services

Stopping and starting SysVinit services

Stopping and starting Upstart services

Stopping and starting systemd services

Stopping a service with systemd

Starting a service with systemd

Restarting a service with systemd

Reloading a service with systemd

Configuring persistent services for SysVinit

Configuring persistent services for Upstart

Configuring persistent services for systemd

Enabling a service with systemd

Disabling a service with systemd

Configuring a Default Runlevel or Target Unit

Configuring the SysVinit default runlevel

Configuring the default runlevel in Upstart

Configuring the default target unit for systemd

Adding New or Customized Services

Adding new services to SysVinit

Step 1: Create a new or customized service script file

Step 2: Add the service script to /etc/rc.d/init.d

Step 3: Add the service to runlevel directories

Adding new services to Upstart

Adding new services to systemd

Step 1: Create a new or customized service configuration unit file

Step 2: Move the service configuration unit file

Step 3: Add the service to the Wants directory

Chapter 16: Configuring a Print Server

Adding a printer automatically

Using web-based CUPS administration

Using the Print Settings window

Configuring local printers with the Print Settings window

Adding a remote UNIX (LDP/LPR) printer

Adding a Windows (SMB) printer

Configuring the CUPS server (cupsd.conf)

Configuring CUPS printer options manually

Configuring a shared CUPS printer

Configuring a shared Samba printer

Understanding smb.conf for printing

Chapter 17: Configuring a Web Server

Understanding the Apache Web Server

Getting and Installing Your Web Server

Understanding the httpd package

Apache file permissions and ownership

Understanding the Apache configuration files

Understanding default settings

Adding a virtual host to Apache

Allowing users to publish their own web content

Securing your web traffic with SSL/TLS

Understanding how SSL is configured

Generating an SSL key and self-signed certificate

Generating a certificate signing request

Troubleshooting Your Web Server

Checking for configuration errors

Accessing forbidden and server internal errors

Chapter 18: Configuring an FTP Server

Installing the vsftpd FTP Server

Opening up your firewall for FTP

Allowing FTP access in TCP wrappers

Configuring SELinux for your FTP server

Relating Linux file permissions to vsftpd

Setting up vsftpd for the Internet

Using FTP Clients to Connect to Your Server

Accessing an FTP server from Firefox

Accessing an FTP server with the lftp command

Chapter 19: Configuring a Windows File Sharing (Samba) Server

Starting the Samba (smb) service

Starting the NetBIOS (nmbd) name server

Stopping the Samba (smb) and NetBIOS (nmb) services

Configuring firewalls for Samba

Setting SELinux Booleans for Samba

Setting SELinux file contexts for Samba

Configuring Samba host/user permissions

Choosing Samba server settings

Configuring Samba user accounts

Creating a Samba shared folder

Configuring Samba in the smb.conf file

Configuring the [global] section

Configuring the [homes] section

Configuring the [printers] section

Creating custom shared directories

Accessing Samba shares in Linux

Accessing Samba shares in Windows

Chapter 20: Configuring an NFS File Server

Configuring the /etc/exports file

Access options in /etc/exports

User mapping options in /etc/exports

Exporting the shared filesystems

Opening up your firewall for NFS

Allowing NFS access in TCP wrappers

Configuring SELinux for your NFS server

Manually mounting an NFS filesystem

Mounting an NFS filesystem at boot time

Using autofs to mount NFS filesystems on demand

Automounting to the /net directory

Chapter 21: Troubleshooting Linux

Starting with System V init scripts

Starting from the firmware (BIOS or UEFI)

Troubleshooting the GRUB boot loader

Troubleshooting the initialization system

Troubleshooting System V initialization

Troubleshooting runlevel processes

Troubleshooting systemd initialization

Troubleshooting Software Packages

Fixing RPM databases and cache

Troubleshooting outgoing connections

Troubleshooting incoming connections

Check if the client can reach your system at all

Check if the service is available to the client

Check the firewall on the server

Check the service on the server

Troubleshooting in Rescue Mode

Part V: Learning Linux Security Techniques

Chapter 22: Understanding Basic Linux Security

Implementing physical security

Implementing disaster recovery

Limit access to the root user account

Setting expiration dates on temporary accounts

Setting and changing passwords

Enforcing best password practices

Understanding the password files and password hashes

Managing dangerous filesystem permissions

Managing software and services

Keeping up with security advisories

Detecting counterfeit new accounts and privileges

Detecting bad account passwords

Detecting viruses and rootkits

Chapter 23: Understanding Advanced Linux Security

Implementing Linux Security with Cryptography

Understanding encryption/decryption

Understanding cryptographic ciphers

Understanding cryptographic cipher keys

Understanding digital signatures

Implementing Linux cryptography

Encrypting Linux with miscellaneous tools

Using Encryption from the Desktop

Implementing Linux Security with PAM

Understanding the PAM authentication process

Understanding PAM control flags

Understanding PAM system event configuration files

Administering PAM on your Linux system

Managing PAM-aware application configuration files

Managing PAM system event configuration files

Implementing resources limits with PAM

Implementing time restrictions with PAM

Enforcing good passwords with PAM

Obtaining more information on PAM

Chapter 24: Enhancing Linux Security with SELinux

Understanding SELinux Benefits

Understanding How SELinux Works

Understanding type enforcement

Understanding multi-level security

Implementing SELinux security models

Understanding SELinux operational modes

Understanding SELinux security contexts

Understanding SELinux policy types

Understanding SELinux policy rule packages

Setting the SELinux policy type

Managing SELinux security contexts

Managing the user security context

Managing the file security context

Managing the process security context

Managing SELinux policy rule packages

Monitoring and Troubleshooting SELinux

Reviewing SELinux messages in the audit log

Reviewing SELinux messages in the messages log

Troubleshooting SELinux logging

Troubleshooting common SELinux problems

Using a nonstandard directory for a service

Using a nonstandard port for a service

Moving files and losing security context labels

Obtaining More Information on SELinux

Chapter 25: Securing Linux on a Network

Evaluating access to network services with nmap

Using nmap to audit your network services advertisements

Controlling access to network services

Understanding the iptables utility

Part VI: Extending Linux into the Cloud

Chapter 26: Using Linux for Cloud Computing

Overview of Linux and Cloud Computing

Cloud hypervisors (a.k.a. compute nodes)

Cloud deployment and configuration

Step 3: Install Linux on hypervisors

Step 4: Start services on the hypervisors

Step 5: Edit /etc/hosts or set up DNS

Step 1: Install Linux software

Step 4: Mount the NFS share on the hypervisors

Step 1: Get images to make virtual machines

Step 2: Check the network bridge

Step 3: Start Virtual Machine Manager (virt-manager)

Step 4: Check connection details

Step 5: Create a new virtual machine

Step 1: Identify other hypervisors

Step 2: Migrate running VM to another hypervisor

Chapter 27: Deploying Linux to the Cloud

Getting Linux to Run in a Cloud

Creating Linux Images for Clouds

Configuring and running a cloud-init cloud instance

Investigating the cloud instance

Expanding your cloud-init configuration

Adding ssh keys with cloud-init

Adding network interfaces with cloud-init

Adding software with cloud-init

Using cloud-init in enterprise computing

Using OpenStack to Deploy Cloud Images

Starting from the OpenStack Dashboard

Configuring your OpenStack virtual network

Configuring keys for remote access

Launching a virtual machine in OpenStack

Accessing the virtual machine via ssh

You can't learn Linux without using it.

I've come to that conclusion over more than a decade of teaching people to learn Linux. You can't just read a book; you can't just listen to a lecture. You need someone to guide you and you need to jump in and do it.

In 1999, Wiley published my Red Hat Linux Bible. The book's huge success gave me the opportunity to become a full-time, independent Linux author. For about a decade, I wrote dozens of Linux books and explored the best ways to explain Linux from the quiet of my small home office.

In 2008, I hit the road. I was hired by Red Hat, Inc., as a full-time instructor, teaching Linux to professional system administrators seeking Red Hat Certified Engineer (RHCE) certification. In my three years as a Linux instructor, I honed my teaching skills in front of live people whose Linux experience ranged from none to experienced professional.

In the previous edition, I turned my teaching experience into text to take a reader from someone who has never used Linux to someone with the skills to become a Linux professional. In this edition, I set out to extend those skills into the cloud. The focus of this ninth edition of the Linux Bible can be summed up in these ways:

The book is organized to enable you to start off at the very beginning with Linux and grow to become a professional Linux system administrator and power user.

Part I, “Getting Started,” includes two chapters designed to help you understand what Linux is and get you started with a Linux desktop:

Part II, “Becoming a Linux Power User,” provides in-depth details on how to use the Linux shell, work with filesystems, manipulate text files, manage processes, and use shell scripts:

In Part III, “Becoming a Linux System Administrator,” you learn how to administer Linux systems:

In Part IV, “Becoming a Linux Server Administrator,” you learn to create powerful network servers and the tools needed to manage them:

In Part V, “Learning Linux Security Techniques,” you learn how to secure your Linux systems and services:

Part VI, “Extending Linux into the Cloud,” takes you into cutting-edge cloud technologies:

Part VI contains two appendixes to help you get the most from your exploration of Linux. Appendix A, “Media,” provides guidance on downloading Linux distributions. Appendix B, “Exercise Answers,” provides sample solutions to the exercises included in chapters 2 through 26.

Throughout the book, special typography indicates code and commands. Commands and code are shown in a monospaced font:

This is how code looks.

In the event that an example includes both input and output, the monospaced font is still used, but input is presented in bold type to distinguish the two. Here's an example:

$ ftp ftp.handsonhistory.com Name (home:jake): jake Password: ******

As for styles in the text:

The following items call your attention to points that are particularly important.

NOTE

A Note box provides extra information to which you need to pay special attention.

TIP

A Tip box shows a special way of performing a particular task.

CAUTION

A Caution box alerts you to take special care when executing a procedure, or damage to your computer hardware or software could result.

If you are new to Linux, you might have vague ideas about what it is and where it came from. You may have heard something about it being free (as in cost) or free (as in freedom to use it as you please). Before you start putting your hands on Linux (which we will do soon enough), Chapter 1 seeks to answer some of your questions about the origins and features of Linux.

Take your time and work through this book to get up to speed on Linux and how you can make it work to meet your needs. This is your invitation to jump in and take the first step to becoming a Linux expert!

Visit the Linux Bible website

To find links to various Linux distributions, tips on gaining Linux certification, and corrections to the book as they become available, go to http://www.wiley.com/go/linuxbible9.

IN THIS CHAPTER

Learning what Linux is

Learning where Linux came from

Choosing Linux distributions

Exploring professional opportunities with Linux

Becoming certified in Linux

Linux is one of the most important technology advancements of the twenty-first century. Besides its impact on the growth of the Internet and its place as an enabling technology for a range of computer-driven devices, Linux development has been a model for how collaborative projects can surpass what single individuals and companies can do alone.

Google runs thousands upon thousands of Linux servers to power its search technology. Its Android phones are based on Linux. Likewise, when you download and run Google's Chrome OS, you get a browser that is backed by a Linux operating system.

Facebook builds and deploys its site using what is referred to as a LAMP stack (Linux, Apache web server, MySQL database, and PHP web scripting language)—all open source projects. In fact, Facebook itself uses an open source development model, making source code for the applications and tools that drive Facebook available to the public. This model has helped Facebook shake out bugs quickly, get contributions from around the world, and fuel Facebook's exponential growth.

Financial organizations that have trillions of dollars riding on the speed and security of their operating systems also rely heavily on Linux. These include the New York Stock Exchange, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

As “cloud” continues to be one of the hottest buzzwords today, a part of the cloud that isn't hype is that Linux and other open source technologies are the foundation on which today's greatest cloud innovations are being built. Every software component you need to build a private or public cloud (such as hypervisors, cloud controllers, network storage, virtual networking, and authentication) is freely available for you to start using from the open source world.

The widespread adoption of Linux around the world has created huge demand for Linux expertise. This chapter starts you on a path to becoming a Linux expert by helping you understand what Linux is, where it came from, and what your opportunities are for becoming proficient in it. The rest of this book provides you with hands-on activities to help you gain that expertise. Finally, I show you how you can apply that expertise to cloud technologies.

Linux is a computer operating system. An operating system consists of the software that manages your computer and lets you run applications on it. The features that make up Linux and similar computer operating systems include the following:

As someone managing Linux systems, you need to learn how to work with those features just described. While many features can be managed using graphical interfaces, an understanding of the shell command line is critical for someone administering Linux systems.

Modern Linux systems now go way beyond what the first UNIX systems (on which Linux was based) could do. Advanced features in Linux, often used in large enterprises, include the following:

Some of these advanced topics are not covered in this book. However, the features covered here for using the shell, working with disks, starting and stopping services, and configuring a variety of servers should serve as a foundation for working with those advanced features.

If you are new to Linux, chances are good that you have used a Microsoft Windows or Apple Mac OS operating system. Although Mac OS X has its roots in a free software operating system, referred to as the Berkeley Software Distribution (more on that later), operating systems from both Microsoft and Apple are considered proprietary operating systems. What that means is:

You might look at those statements about proprietary software and say, “What do I care? I'm not a software developer. I don't want to see or change how my operating system is built.”

That may be true. But the fact that others can take free and open source software and use it as they please has driven the explosive growth of the Internet (think Google), mobile phones (think Android), special computing devices (think Tivo), and hundreds of technology companies. Free software has driven down computing costs and allowed for an explosion of innovation.

Maybe you don't want to use Linux—as Google, Facebook, and other companies have done—to build the foundation for a multi-billion-dollar company. But those and other companies who now rely on Linux to drive their computer infrastructures need more and more people with the skills to run those systems.

You may wonder how a computer system that is so powerful and flexible has come to be free as well. To understand how that could be, you need to see where Linux came from. So the next section of this chapter describes the strange and winding path of the free software movement that led to Linux.

Some histories of Linux begin with this message posted by Linus Torvalds to the comp.os.minix newsgroup on August 25, 1991 (http://groups.google.com/group/comp.os.minix/msg/b813d52cbc5a044b?pli=1):

Hello everybody out there using minix -

I'm doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won't be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. This has been brewing since april, and is starting to get ready. I'd like any feedback on things people like/dislike in minix, as my OS resembles it somewhat (same physical layout of the file-system (due to practical reasons, among other things)...Any suggestions are welcome, but I won't promise I'll implement them :-)

Linus (torvalds@kruuna.helsinki.fi)

PS. Yes — it's free of any minix code, and it has a multi-threaded fs. It is NOT protable [sic] (uses 386 task switching etc), and it probably never will support anything other than AT-harddisks, as that's all I have :-(.

Minix was a UNIX-like operating system that ran on PCs in the early 1990s. Like Minix, Linux was also a clone of the UNIX operating system. With few exceptions, such as Microsoft Windows, most modern computer systems (including Mac OS X and Linux) were derived from UNIX operating systems, created originally by AT&T.

To truly appreciate how a free operating system could have been modeled after a proprietary system from AT&t Bell Laboratories, it helps to understand the culture in which UNIX was created and the chain of events that made the essence of UNIX possible to reproduce freely.

NOTE

To learn more about how Linux was created, pick up the book Just for Fun: The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary by Linus Torvalds (HarperCollins Publishing, 2001).

From the very beginning, the UNIX operating system was created and nurtured in a communal environment. Its creation was not driven by market needs, but by a desire to overcome impediments to producing programs. AT&T, which owned the UNIX trademark originally, eventually made UNIX into a commercial product, but by that time, many of the concepts (and even much of the early code) that made UNIX special had fallen into the public domain.

If you are not old enough to remember when AT&T split up in 1984, you may not remember a time when AT&T was “the” phone company. Up until the early 1980s, AT&T didn't have to think much about competition because if you wanted a phone in the United States, you had to go to AT&T. It had the luxury of funding pure research projects. The mecca for such projects was the Bell Laboratories site in Murray Hill, New Jersey.

After a project called Multics failed in around 1969, Bell Labs employees Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie set off on their own to create an operating system that would offer an improved environment for developing software. Up to that time, most programs were written on punch cards that had to be fed in batches to mainframe computers. In a 1980 lecture on “The Evolution of the UNIX Time-sharing System,” Dennis Ritchie summed up the spirit that started UNIX:

What we wanted to preserve was not just a good environment in which to do programming, but a system around which a fellowship could form. We knew from experience that the essence of communal computing as supplied by remote-access, time-shared machines is not just to type programs into a terminal instead of a keypunch, but to encourage close communication.

The simplicity and power of the UNIX design began breaking down barriers that, until this point, had impeded software developers. The foundation of UNIX was set with several key elements:

$ cat filel file2 | sort | pr | lpr

This method of directing input and output enabled developers to create their own specialized utilities that could be joined with existing utilities. This modularity made it possible for lots of code to be developed by lots of different people. A user could just put together the pieces as needed.

To make portability a reality, however, a high-level programming language was needed to implement the software needed. To that end, Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie created the C programming language. In 1973, UNIX was rewritten in C. Today, C is still the primary language used to create the UNIX (and Linux) operating system kernels.

As Ritchie went on to say in a 1979 lecture (http://cm.bell-labs.com/who/dmr/hist.html):

Today, the only important UNIX program still written in assembler is the assembler itself; virtually all the utility programs are in C, and so are most of the application's programs, although there are sites with many in Fortran, Pascal, and Algol 68 as well. It seems certain that much of the success of UNIX follows from the readability, modifiability, and portability of its software that in turn follows from its expression in high-level languages.

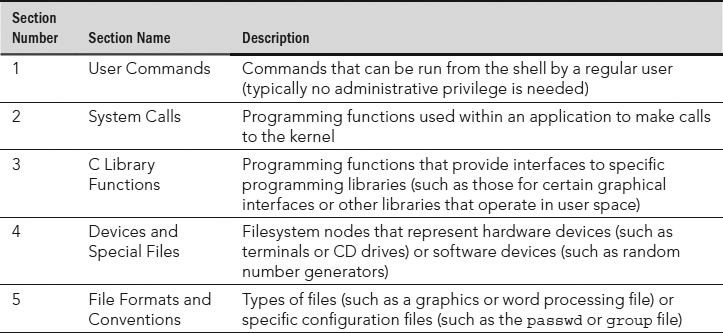

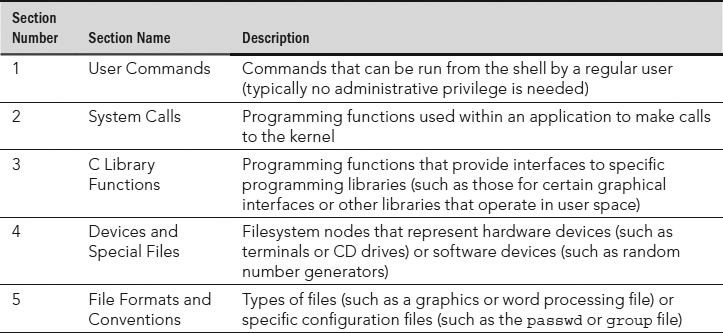

If you are a Linux enthusiast and are interested in what features from the early days of Linux have survived, an interesting read is Dennis Ritchie's reprint of the first UNIX programmer's manual (dated November 3, 1971). You can find it at Dennis Ritchie's website: http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/who/dmr/1stEdman.html. The form of this documentation is UNIX man pages, which is still the primary format for documenting UNIX and Linux operating system commands and programming tools today.

What's clear as you read through the early documentation and accounts of the UNIX system is that the development was a free-flowing process, lacked ego, and was dedicated to making UNIX excellent. This process led to a sharing of code (both inside and outside Bell Labs), which allowed rapid development of a high-quality UNIX operating system. It also led to an operating system that AT&T would find difficult to reel back in later.

Before the AT&T divestiture in 1984, when it was split up into AT&T and seven “Baby Bell” companies, AT&T was forbidden to sell computer systems. Companies that would later become Verizon, Qwest, and Alcatel-Lucent were all part of AT&T. As a result of AT&T's monopoly of the telephone system, the U.S. government was concerned that an unrestricted AT&T might dominate the fledgling computer industry.

Because AT&T was restricted from selling computers directly to customers before its divestiture, UNIX source code was licensed to universities for a nominal fee. There was no UNIX operating system for sale from AT&T that you didn't have to compile yourself.

In 1975, UNIX V6 became the first version of UNIX available for widespread use outside Bell Laboratories. From this early UNIX source code, the first major variant of UNIX was created at University of California at Berkeley. It was named the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD).

For most of the next decade, the BSD and Bell Labs versions of UNIX headed off in separate directions. BSD continued forward in the free-flowing, share-the-code manner that was the hallmark of the early Bell Labs UNIX, whereas AT&T started steering UNIX toward commercialization. With the formation of a separate UNIX Laboratory, which moved out of Murray Hill and down the road to Summit, New Jersey, AT&T began its attempts to commercialize UNIX. By 1984, divestiture was behind AT&T and it was ready to really start selling UNIX.

The UNIX Laboratory was considered a jewel that couldn't quite find a home or a way to make a profit. As it moved between Bell Laboratories and other areas of AT&T, its name changed several times. It is probably best remembered by the name it had as it began its spin-off from AT&T: UNIX System Laboratories (USL).

The UNIX source code that came out of USL, the legacy of which was sold in part to Santa Cruz Operation (SCO), was used for a time as the basis for ever-dwindling lawsuits by SCO against major Linux vendors (such as IBM and Red Hat, Inc.). Because of that, I think the efforts from USL that have contributed to the success of Linux are lost on most people.

During the 1980s, of course, many computer companies were afraid that a newly divested AT&T would pose more of a threat to controlling the computer industry than would an upstart company in Redmond, Washington. To calm the fears of IBM, Intel, Digital Equipment Corporation, and other computer companies, the UNIX Lab made the following commitments to ensure a level playing field:

NOTE

In an early email newsgroup post, Linus Torvalds made a request for a copy, preferably online, of the POSIX standard. I think that nobody from AT&T expected someone to actually be able to write his own clone of UNIX from those interfaces, without using any of its UNIX source code.

When USL eventually started taking on marketing experts and creating a desktop UNIX product for end users, Microsoft Windows already had a firm grasp on the desktop market. Also, because the direction of UNIX had always been toward source-code licensing destined for large computing systems, USL had pricing difficulties for its products. For example, on software that it was including with UNIX, USL found itself having to pay out per-computer licensing fees that were based on $100,000 mainframes instead of $2,000 PCs. Add to that the fact that no application programs were available with UnixWare, and you can see why the endeavor failed.

Successful marketing of UNIX systems at the time, however, was happening with other computer companies. SCO had found a niche market, primarily selling PC versions of UNIX running dumb terminals in small offices. Sun Microsystems was selling lots of UNIX workstations (originally based on BSD but merged with UNIX in SVR4) for programmers and high-end technology applications (such as stock trading).

Other commercial UNIX systems were also emerging by the 1980s as well. This new ownership assertion of UNIX was beginning to take its toll on the spirit of open contributions. Lawsuits were being initiated to protect UNIX source code and trademarks. In 1984, this new, restrictive UNIX gave rise to an organization that eventually led a path to Linux: the Free Software Foundation.

In 1984, Richard M. Stallman started the GNU project (http://www.gnu.org), recursively named by the phrase GNU is Not UNIX. As a project of the Free Software Foundation (FSF), GNU was intended to become a recoding of the entire UNIX operating system that could be freely distributed.

The GNU Project page (http://www.gnu.org/gnu/thegnuproject.html) tells the story of how the project came about in Stallman's own words. It also lays out the problems that proprietary software companies were imposing on those software developers who wanted to share, create, and innovate.

Although rewriting millions of lines of code might seem daunting for one or two people, spreading the effort across dozens or even hundreds of programmers made the project possible. Remember that UNIX was designed to be built in separate pieces that could be piped together. Because they were reproducing commands and utilities with well-known, published interfaces, that effort could easily be split among many developers.

It turned out that not only could the same results be gained by all new code, but in some cases, that code was better than the original UNIX versions. Because everyone could see the code being produced for the project, poorly written code could be corrected quickly or replaced over time.

If you are familiar with UNIX, try searching the thousands of GNU software packages for your favorite UNIX command from the Free Software Directory (http://directory.fsf.org/wiki/GNU). Chances are good that you will find it there, along with many, many other available software projects.

Over time, the term free software has been mostly replaced by the term open source software. The term “free software” is preferred by the Free Software Foundation, while open source software is promoted by the Open Source Initiative (http://www.opensource.org).

To accommodate both camps, some people use the term Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) instead. An underlying principle of FOSS, however, is that, although you are free to use the software as you like, you have some responsibility to make the improvements you make to the code available to others. In that way, everyone in the community can benefit from your work as you have benefited from the work of others.

To clearly define how open source software should be handled, the GNU software project created the GNU Public License, or GPL. Although many other software licenses cover slightly different approaches to protecting free software, the GPL is the most well known—and it's the one that covers the Linux kernel itself. Basic features of the GNU Public License include the following:

There is no warranty on GNU software. If something goes wrong, the original developer of the software has no obligation to fix the problem. However, many organizations, big and small, offer paid support (often in subscription form) for the software when it is included in their Linux or other open source software distribution. (See the “OSI open source definition” section later in this chapter for a more detailed definition of open source software.)

Despite its success in producing thousands of UNIX utilities, the GNU project itself failed to produce one critical piece of code: the kernel. Its attempts to build an open source kernel with the GNU Hurd project (http://www.gnu.org/software/hurd) were unsuccessful at first, so it failed to become the premier open source kernel.

The one software project that had a chance of beating out Linux to be the premier open source kernel was the venerable BSD project. By the late 1980s, BSD developers at University of California (UC) Berkeley realized that they had already rewritten most of the UNIX source code they had received a decade earlier.

In 1989, UC Berkeley distributed its own UNIX-like code as Net/1 and later (in 1991) as Net/2. Just as UC Berkeley was preparing a complete, UNIX-like operating system that was free from all AT&T code, AT&T hit them with a lawsuit in 1992. The suit claimed that the software was written using trade secrets taken from AT&T's UNIX system.

It's important to note here that BSD developers had completely rewritten the copyright-protected code from AT&T. Copyright was the primary means AT&T used to protect its rights to the UNIX code. Some believe that if AT&T had patented the concepts covered in that code, there might not be a Linux (or any UNIX clone) operating system today.

The lawsuit was dropped when Novell bought UNIX System Laboratories from AT&T in 1994. But, during that critical period, there was enough fear and doubt about the legality of the BSD code that the momentum BSD had gained to that point in the fledgling open source community was lost. Many people started looking for another open source alternative. The time was ripe for a college student from Finland who was working on his own kernel.

NOTE

Today, BSD versions are available from three major projects: FreeBSD, NetBSD, and OpenBSD. People generally characterize FreeBSD as the easiest to use, NetBSD as available on the most computer hardware platforms, and OpenBSD as fanatically secure. Many security-minded individuals still prefer BSD to Linux. Also, because of its licensing, BSD code can be used by proprietary software vendors, such as Microsoft and Apple, who don't want to share their operating system code with others. Mac OS X is built on a BSD derivative.

Linus Torvalds started work on Linux in 1991, while he was a student at the University of Helsinki, Finland. He wanted to create a UNIX-like kernel so that he could use the same kind of operating system on his home PC that he used at school. At the time, Linus was using Minix, but he wanted to go beyond what the Minix standards permitted.

As noted earlier, Linus announced the first public version of the Linux kernel to the comp.os.minix newsgroup on August 25, 1991, although Torvalds guesses that the first version didn't actually come out until mid-September of that year.

Although Torvalds stated that Linux was written for the 386 processor and probably wasn't portable, others persisted in encouraging (and contributing to) a more portable approach in the early versions of Linux. By October 5, Linux 0.02 was released with much of the original assembly code rewritten in the C programming language, which made it possible to start porting it to other machines.

The Linux kernel was the last—and the most important—piece of code that was needed to complete a whole UNIX-like operating system under the GPL. So, when people started putting together distributions, the name Linux and not GNU is what stuck. Some distributions such as Debian, however, refer to themselves as GNU/Linux distributions. (Not including GNU in the title or subtitle of a Linux operating system is also a matter of much public grumbling by some members of the GNU project. See http://www.gnu.org.)

Today, Linux can be described as an open source UNIX-like operating system that reflects a combination of SVID, POSIX, and BSD compliance. Linux continues to aim toward compliance with POSIX as well as with standards set by the owner of the UNIX trademark, The Open Group(http://www.unix.org).

The non-profit Open Source Development Labs, renamed the Linux Foundation after merging with the Free Standards Group (http://www.linuxfoundation.org), which employs Linus Torvalds, manages the direction today of Linux development efforts. Its sponsors list is like a Who's Who of commercial Linux system and application vendors, including IBM, Red Hat, SUSE, Oracle, HP, Dell, Computer Associates, Intel, Cisco Systems, and others. The Linux Foundation's primary charter is to protect and accelerate the growth of Linux by providing legal protection and software development standards for Linux developers.

Although much of the thrust of corporate Linux efforts is on corporate, enterprise computing, huge improvements are continuing in the desktop arena as well. The KDE and GNOME desktop environments continuously improve the Linux experience for casual users. Newer lightweight desktop environments such as Xfce and LXDE now offer efficient alternatives that today bring Linux to thousands of netbook owners.

Linus Torvalds continues to maintain and improve the Linux kernel.

NOTE

For a more detailed history of Linux, see the book Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution (O'Reilly, 1999). The entire first edition is available online at http://oreilly.com/catalog/opensources/book/toc.html.

Linux provides a platform that lets software developers change the operating system as they like and get a wide range of help creating the applications they need. One of the watchdogs of the open source movement is the Open Source Initiative (OSI, http://www.opensource.org).

Although the primary goal of open source software is to make source code available, other goals of open source software are also defined by OSI in its open source definition. Most of the following rules for acceptable open source licenses serve to protect the freedom and integrity of the open source code:

Open source licenses used by software development projects must meet these criteria to be accepted as open source software by OSI. About 70 different licenses are accepted by OSI to be used to label software as “OSI Certified Open Source Software.” In addition to the GPL, other popular OSI-approved licenses include:

The end result of open source code is software that has more flexibility to grow and fewer boundaries in how it can be used. Many believe that the fact that numerous people look over the source code for a project results in higher-quality software for everyone. As open source advocate Eric S. Raymond says in an often-quoted line, “Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.”

Having bundles of source code floating around the Internet that could be compiled and packaged into a Linux system worked well for geeks. More casual Linux users, however, needed a simpler way to put together a Linux system. To respond to that need, some of the best geeks began building their own Linux distributions.

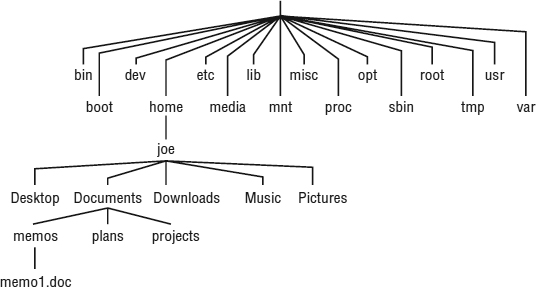

A Linux distribution consists of the components needed to create a working Linux system and the procedures needed to get those components installed and running. Technically, Linux is really just what is referred to as the kernel. Before the kernel can be useful, you must have other software such as basic commands (GNU utilities), services you want to offer (such as remote login or web servers), and possibly a desktop interface and graphical applications. Then, you must be able to gather all that together and install it on your computer's hard disk.

Slackware (http://www.slackware.com) is one of the oldest Linux distributions still being developed today. It made Linux friendly for less technical users by distributing software already compiled and grouped into packages (those packages of software components were in a format called tarballs). You would use basic Linux commands then to do things like format your disk, enable swap, and create user accounts.

Before long, many other Linux distributions were created. Some Linux distributions were created to meet special needs, such as KNOPPIX (a live CD Linux), Gentoo (a cool customizable Linux), and Mandrake (later called Mandriva, which was one of several desktop Linux distributions). But two major distributions rose to become the foundation for many other distributions: Red Hat Linux and Debian.

When Red Hat Linux appeared in the late 1990s, it quickly became the most popular Linux distribution for several reasons:

For years, Red Hat Linux was the preferred Linux distribution for both Linux professionals and enthusiasts. Red Hat, Inc., gave away the source code, as well as the compiled, ready-to-run versions of Red Hat Linux (referred to as the binaries). But as the needs of their Linux community users and big-ticket customers began to move further apart, Red Hat abandoned Red Hat Linux and began developing two operating systems instead: Red Hat Enterprise Linux and Fedora.

In March 2012, Red Hat, Inc., became the first open source software company to bring in more than $1 billion in yearly revenue. It achieved that goal by building a set of products around Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) that would suit the needs of the most demanding enterprise computing environments.

While other Linux distributions focused on desktop systems or small business computing, RHEL worked on those features needed to handle mission-critical applications for business and government. It built systems that could speed transactions for the world's largest financial exchanges and be deployed as clusters and virtual hosts.

Instead of just selling RHEL, Red Hat offers an ecosystem of benefits for Linux customers to draw on. To use RHEL, customers buy subscriptions that they can use to deploy any version of RHEL they desire. If they decommission a RHEL system, they can use the subscription to deploy another system.

Different levels of support are available for RHEL, depending on customer needs. Customers can be assured that, along with support, they can get hardware and third-party software that is certified to work with RHEL. They can get Red Hat consultants and engineers to help them put together the computing environments they need. They can also get training and certification exams for their employees (see the discussion of RHCE certification later in this chapter).

Red Hat has also added other products as natural extensions to Red Hat Enterprise Linux. JBoss is a middleware product for deploying Java-based applications to the Internet or company intranets. Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization is composed of the virtualization hosts, managers, and guest computers that allow you to install, run, manage, migrate, and decommission huge virtual computing environments.

In recent years, Red Hat has extended its portfolio into cloud computing. RHEL OpenStack Platform and Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization offer complete platforms for running and managing virtual machines. Red Hat Cloudforms is a cloud management platform. RHEL Atomic and Linux containers in Docker format offer ways of containerizing applications for the cloud.

There are those who have tried to clone RHEL, using the freely available RHEL source code, rebuilding and rebranding it. Oracle Linux is built from source code for RHEL but currently offers an incompatible kernel. CentOS is a community-sponsored Linux distribution that is built from RHEL source code. Recently, Red Hat took over support of the CentOS project.

I've chosen to use Red Hat Enterprise Linux for many of the examples in this book because, if you want a career working on Linux systems, there is a huge demand for those who can administer RHEL systems. If you are starting out with Linux, however, Fedora can provide an excellent entry point to the same skills you need to use and administer RHEL systems.

While RHEL is the commercial, stable, supported Linux distribution, Fedora is the free, cutting-edge Linux distribution that is sponsored by Red Hat, Inc. Fedora is the Linux system Red Hat uses to engage the Linux development community and encourage those who want a free Linux for personal use and rapid development.

Fedora includes more than 16,000 software packages, many of which keep up with the latest available open source technology. As a user, you can try the latest Linux desktop, server, and administrative interfaces in Fedora for free. As a software developer, you can create and test your applications using the latest Linux kernel and development tools. Because the focus of Fedora is on the latest technology, it focuses less on stability. So expect that you might need to do some extra work to get everything working and that not all the software will be fully baked.

However, I recommend that you use Fedora for most of the examples in this book for the following reasons:

Fedora is extremely popular with those who develop open source software. However, in the past few years, another Linux distribution has captured the attention of many people starting out with Linux: Ubuntu.

Like Red Hat Linux, the Debian GNU/Linux distribution was an early Linux distribution that excelled at packaging and managing software. Debian uses deb packaging format and tools to manage all of the software packages on its systems. Debian also has a reputation for stability.

Many Linux distributions can trace their roots back to Debian. According to distrowatch (http://distrowatch.com), more than 130 active Linux distributions can be traced back to Debian. Popular Debian-based distributions include Linux Mint, elementary OS, Zorin OS, LXLE, Kali Linux, and many others. However, the Debian derivative that has achieved the most success is Ubuntu (http://www.ubuntu.com).

By relying on stable Debian software development and packaging, the Ubuntu Linux distribution was able to come along and add those features that Debian lacked. In pursuit of bringing new users to Linux, the Ubuntu project added a simple graphical installer and easy-to-use graphical tools. It also focused on full-featured desktop systems, while still offering popular server packages.

Ubuntu was also an innovator in creating new ways to run Linux. Using live CDs or live USB drives offered by Ubuntu, you could have Ubuntu up and running in just a few minutes. Often included on live CDs were open source applications, such as web browsers and word processors, that actually ran in Windows. This made the transition to Linux from Windows easier for some people.

If you are using Ubuntu, don't fear. Most of subject matter covered in this book will work as well in Ubuntu as it does in Fedora or RHEL. This edition of Linux Bible provides expanded coverage of Ubuntu.

If you want to develop an idea for a computer-related research project or technology company, where do you begin? You begin with an idea. After that, you look for the tools you need to explore and eventually create your vision. Then, you look for others to help you during that creation process.

Today, the hard costs of starting a company like Google or Facebook include just a computer, a connection to the Internet, and enough caffeinated beverage of your choice to keep you up all night writing code. If you have your own world-changing idea, Linux and thousands of software packages are available to help you build your dreams. The open source world also comes with communities of developers, administrators, and users who are available to help you.

If you want to get involved with an existing open source project, projects are always looking for people to write code, test software, or write documentation. In those projects, you will find people who use the software, work on the software, and are usually willing to share their expertise to help you as well.

But whether you seek to develop the next great open source software project or simply want to gain the skills needed to compete for the thousands of well-paying Linux administrator or development jobs, it will help you to know how to install, secure, and maintain Linux systems.

So, what are the prospects for Linux careers? “The 2014 Linux Jobs Report” from the Linux Foundation(http://www.linuxfoundation.org/publications/linux-foundation/linux-adoption-trends-end-user-report-2014) surveyed more than 1,100 hiring managers and 4,000 Linux professionals. Here is what the Linux Foundation found:

The major message to take from this survey is that Linux continues to grow and create demands for Linux expertise. Companies that have begun using Linux have continued to move forward with Linux. Those using Linux continue to expand its use and find that cost savings, security, and the flexibility it offers continue to make Linux a good investment.

Open source enthusiasts believe that better software can result from an open source software development model than from proprietary development models. So in theory, any company creating software for its own use can save money by adding its software contributions to those of others to gain a much better end product for themselves.

Companies that want to make money by selling software need to be more creative than they were in the old days. Although you can sell the software you create that includes GPL software, you must pass the source code of that software forward. Of course, others can then recompile that product, basically using and even reselling your product without charge. Here are a few ways that companies are dealing with that issue:

Although Red Hat's Fedora project includes much of the same software and is also available in binary form, there are no guarantees associated with the software or future updates of that software. A small office or personal user might take a risk on using Fedora (which is itself an excellent operating system), but a big company that's running mission-critical applications will probably put down a few dollars for RHEL.

Other certification programs are offered by Linux Professional Institute (http://www.lpi.org), CompTIA (http://www.comptia.org), and Novell (https://training.novell.com/). LPI and CompTIA are professional computer industry associations. Novell centers its training and certification on its SUSE Linux products.

This is in no way an exhaustive list, because more creative ways are being invented every day to support those who create open source software. Remember that many people have become contributors to and maintainers of open source software because they needed or wanted the software themselves. The contributions they make for free are worth the return they get from others who do the same.

Although this book is not focused on becoming certified in Linux, it touches on the activities you need to be able to master to pass popular Linux certification exams. In particular, most of what is covered in the Red Hat Certified Engineer (RHCE) and Red Hat Certified System Administrator (RHCSA) exams for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 is described in this book.

If you are looking for a job as a Linux IT professional, often RHCSA or RHCE certification is listed as a requirement or at least a preference for employers. The RHCSA exam (EX200) provides the basic certification, covering such topics as configuring disks and filesystems, adding users, setting up a simple web and FTP server, and adding swap space. The RHCE exam (EX300) tests for more advanced server configuration, as well an advanced knowledge of security features, such as SELinux and firewalls.

Those of us who have taught RHCE/RHCSA courses and given exams (as I did for three years) are not allowed to tell you exactly what is on the exam. However, Red Hat gives an overview of how the exams work, as well as a list of topics you can expect to see covered in the exam. You can find those exam objectives on the following sites:

As the exam objectives state, the RHCSA and RHCE exams are performance-based, which means that you are given tasks to do and you must perform those tasks on an actual Red Hat Enterprise Linux system, as you would on the job. You are graded on how well you obtained the results of those tasks.

If you plan to take the exams, check back to the exam objectives pages often, because they change from time to time. Keep in mind also that the RHCSA is a standalone certification; however, you must pass the RHCSA and the RHCE exams to get an RHCE certification. Often, the two exams are given on the same day.

You can sign up for RHCSA and RHCE training and exams at http://training.redhat.com. Training and exams are given at major cities all over the United States and around the world. The skills you need to complete these exams are described in the following sections.

As noted earlier, RHCSA exam topics cover basic system administration skills. These are the current topics listed for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 at the RHCSA exam objectives site (again, check the exam objectives site in case they change) and where in this book you can learn about them:

Most of these topics are covered in this book. Refer to Red Hat documentation (https://access.redhat.com/documentation/) under the Red Hat Enterprise Linux heading for descriptions of features not found in this book. In particular, the System Administrator's Guide contains descriptions of many of the RHCSA-related topics.

RHCE exam topics cover more advanced server configuration, along with a variety of security features for securing those servers in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7. Again, check the RHCE exam objectives site for the most up-to-date information on topics you should study for the exam.

The system configuration and management requirement for the RHCE exam covers a range of topics, including the following:

For each of the network services in the list that follows, make sure that you can go through the steps to install packages required by the service, set up SELinux to allow access to the service, set the service to start at boot time, secure the service by host or by user (using iptables, TCP wrappers, or features provided by the service itself), and configure it for basic operation. These are the services:

Although there are other tasks in the RHCE exam, as just noted, keep in mind that most of the tasks have you configure servers and then secure those servers using any technique you need. Those can include firewall rules (iptables), SELinux, TCP Wrappers, or any features built into configuration files for the particular service.

Linux is an operating system that is built by a community of software developers around the world and led by its creator, Linus Torvalds. It is derived originally from the UNIX operating system, but has grown beyond UNIX in popularity and power over the years.

The history of the Linux operating system can be tracked from early UNIX systems that were distributed free to colleges and improved by initiatives such as the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD). The Free Software Foundation helped make many of the components needed to create a fully-free UNIX-like operating system. The Linux kernel itself was the last major component needed to complete the job.

Most Linux software projects are protected by one of a set of licenses that fall under the Open Source Initiative umbrella. The most prominent of these is the GNU Public License (GPL). Standards such as the Linux Standard Base and world-class Linux organizations and companies (such as Canonical Ltd. and Red Hat, Inc.) make it possible for Linux to continue to be a stable, productive operating system into the future.

Learning the basics of how to use and administer a Linux system will serve you well in any aspect of working with Linux. The remaining chapters each provide a series of exercises with which you can test your understanding. That's why, for the rest of the book, you will learn best with a Linux system in front of you so you can work through the examples in each chapter and complete the exercises successfully.

The next chapter describes how to get started with Linux by describing how to get and use a Linux desktop system.

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding the X Window System and desktop environments

Running Linux from a Live CD/DVD

Navigating the GNOME 3 desktop

Adding extensions to GNOME 3

Using Nautilus to manage files in GNOME 3

Working with the GNOME 2 desktop

Enabling 3D effects in GNOME 2

Using Linux as your everyday desktop system is becoming easier to do all the time. As with everything in Linux, you have choices. There are full-featured GNOME or KDE desktop environments or lightweight desktops such as LXDE or Xfce. There are even simpler standalone window managers.

After you have chosen a desktop, you will find that almost every major type of desktop application you have on a Windows or Mac system has equivalent applications in Linux. For applications that are not available in Linux, you can often run a Windows application in Linux using Windows compatibility software.

The goal of this chapter is to familiarize you with the concepts related to Linux desktop systems and to give you tips for working with a Linux desktop. In this chapter you:

To use the descriptions in this chapter, I recommend you have a Fedora system running in front of you. You can get Fedora in lots of ways, including these:

Because the current release of Fedora uses the GNOME 3 interface, most of the procedures described here work with other Linux distributions that have GNOME 3 available. If you are using an older Red Hat Enterprise Linux system (RHEL 6 uses GNOME 2, but RHEL 7 uses GNOME 3), I added descriptions of GNOME 2 that you can try as well.

NOTE

Ubuntu uses its own Unity desktop as its default, instead of GNOME. There is, however, an Ubuntu GNOME project. To download the medium for the latest Ubuntu version with a GNOME desktop, go to the Ubuntu GNOME download page (http://ubuntugnome.org/download/).

You can add GNOME and use it as the desktop environment for Ubuntu 11.10 and later. Older Ubuntu releases use GNOME 2 by default.

Modern computer desktop systems offer graphical windows, icons, and menus that are operated from a mouse and keyboard. If you are under 30 years old, you might think there's nothing special about that. But the first Linux systems did not have graphical interfaces available. Also, today, many Linux servers tuned for special tasks (for example, serving as a web server or file server) don't have desktop software installed.

Nearly every major Linux distribution that offers desktop interfaces is based on the X Window System (http://www.x.org). The X Window System provides a framework on which different types of desktop environments or simple window managers can be built.

The X Window System (sometimes simply called X) was created before Linux existed and even predates Microsoft Windows. It was built to be a lightweight, networked desktop framework.

X works in a sort of backward client/server model. The X server runs on the local system, providing an interface to your screen, mouse, and keyboard. X clients (such as word processors, music players, or image viewers) can be launched from the local system or from any system on your network, provided that the X server gives permission to do so.

X was created in a time when graphical terminals (thin clients) simply managed the keyboard, mouse, and display. Applications, disk storage, and processing power were all on larger centralized computers. So applications ran on larger machines but were displayed and managed over the network on the thin client. Later, thin clients were replaced by desktop personal computers. Most client applications on PCs ran locally, using local processing power, disk space, memory, and other hardware features, while not allowing applications that didn't start from the local system.

X itself provides a plain gray background and a simple “X” mouse cursor. There are no menus, panels, or icons on a plain X screen. If you were to launch an X client (such as a terminal window or word processor), it would appear on the X display with no border around it to move, minimize, or close the window. Those features are added by a window manager.

A window manager adds the capability to manage the windows on your desktop and often provides menus for launching applications and otherwise working with the desktop. A full-blown desktop environment includes a window manager, but also adds menus, panels, and usually an application programming interface that is used to create applications that play well together.

So how does an understanding of how desktop interfaces work in Linux help you when it comes to using Linux? Here are some ways:

Many different desktop environments are available to choose from in Linux. Here are some examples:

GNOME was originally designed to resemble the MAC OS desktop, while KDE was meant to emulate the Windows desktop environment. Because it is the most popular desktop environment, and the one most often used in business Linux systems, most desktop procedures and exercises in this book use the GNOME desktop. Using GNOME, however, still gives you the choice of several different Linux distributions.

A live Linux ISO image is the quickest way to get a Linux system up and running so you can start trying it out. Depending on its size, the image can be burned to a CD, DVD, or USB drive and booted on your computer. With a Linux live image, you can have Linux take over the operation of your computer temporarily, without harming the contents of your hard drive.