Creating the Perfect Linux

Desktop

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding the X Window System and desktop environments

Running Linux from a Live CD/DVD

Navigating the GNOME 3 desktop

Adding extensions to GNOME 3

Using Nautilus to manage files in GNOME 3

Working with the GNOME 2 desktop

Enabling 3D effects in GNOME 2

Using Linux as your everyday desktop system is becoming easier to do all the time. As with everything in Linux, you have choices. There are full-featured GNOME or KDE desktop environments or lightweight desktops such as LXDE or Xfce. There are even simpler standalone window managers.

After you have chosen a desktop, you will find that almost every major type of desktop application you have on a Windows or Mac system has equivalent applications in Linux. For applications that are not available in Linux, you can often run a Windows application in Linux using Windows compatibility software.

The goal of this chapter is to familiarize you with the concepts related to Linux desktop systems and to give you tips for working with a Linux desktop. In this chapter you:

- Step through the desktop features and technologies that are available in Linux

- Tour the major features of the GNOME desktop environment

- Learn tips and tricks for getting the most out of your GNOME desktop experience

To use the descriptions in this chapter, I recommend you have a Fedora system running in front of you. You can get Fedora in lots of ways, including these:

- Running Fedora from a live medium—Refer to Appendix A for information on downloading and burning Fedora Live image to a DVD or USB drive so you can boot it live to use with this chapter.

- Installing Fedora permanently—Install Fedora to your hard disk and boot it from there (as described in Chapter 9, “Installing Linux”).

Because the current release of Fedora uses the GNOME 3 interface, most of the procedures described here work with other Linux distributions that have GNOME 3 available. If you are using an older Red Hat Enterprise Linux system (RHEL 6 uses GNOME 2, but RHEL 7 uses GNOME 3), I added descriptions of GNOME 2 that you can try as well.

NOTE

Ubuntu uses its own Unity desktop as its default, instead of GNOME. There is, however, an Ubuntu GNOME project. To download the medium for the latest Ubuntu version with a GNOME desktop, go to the Ubuntu GNOME download page (http://ubuntugnome.org/download/).

You can add GNOME and use it as the desktop environment for Ubuntu 11.10 and later. Older Ubuntu releases use GNOME 2 by default.

Understanding Linux Desktop Technology

Modern computer desktop systems offer graphical windows, icons, and menus that are operated from a mouse and keyboard. If you are under 30 years old, you might think there's nothing special about that. But the first Linux systems did not have graphical interfaces available. Also, today, many Linux servers tuned for special tasks (for example, serving as a web server or file server) don't have desktop software installed.

Nearly every major Linux distribution that offers desktop interfaces is based on the X Window System (http://www.x.org). The X Window System provides a framework on which different types of desktop environments or simple window managers can be built.

The X Window System (sometimes simply called X) was created before Linux existed and even predates Microsoft Windows. It was built to be a lightweight, networked desktop framework.

X works in a sort of backward client/server model. The X server runs on the local system, providing an interface to your screen, mouse, and keyboard. X clients (such as word processors, music players, or image viewers) can be launched from the local system or from any system on your network, provided that the X server gives permission to do so.

X was created in a time when graphical terminals (thin clients) simply managed the keyboard, mouse, and display. Applications, disk storage, and processing power were all on larger centralized computers. So applications ran on larger machines but were displayed and managed over the network on the thin client. Later, thin clients were replaced by desktop personal computers. Most client applications on PCs ran locally, using local processing power, disk space, memory, and other hardware features, while not allowing applications that didn't start from the local system.

X itself provides a plain gray background and a simple “X” mouse cursor. There are no menus, panels, or icons on a plain X screen. If you were to launch an X client (such as a terminal window or word processor), it would appear on the X display with no border around it to move, minimize, or close the window. Those features are added by a window manager.

A window manager adds the capability to manage the windows on your desktop and often provides menus for launching applications and otherwise working with the desktop. A full-blown desktop environment includes a window manager, but also adds menus, panels, and usually an application programming interface that is used to create applications that play well together.

So how does an understanding of how desktop interfaces work in Linux help you when it comes to using Linux? Here are some ways:

- Because Linux desktop environments are not required to run a Linux system, a Linux system may have been installed without a desktop. It might offer only a plain-text, command-line interface. You can choose to add a desktop later. After it is installed, you can choose whether to start up the desktop when your computer boots or start it as needed.

- For a very lightweight Linux system, such as one meant to run on less powerful computers, you can choose an efficient, though less feature-rich, window manager (such as twm or fluxbox) or a lightweight desktop environment (such as LXDE or Xfce).

- For more robust computers, you can choose more powerful desktop environments (such as GNOME and KDE) that can do such things as watch for events to happen (such as inserting a USB flash drive) and respond to those events (such as opening a window to view the contents of the drive).

- You can have multiple desktop environments installed and you can choose which one to launch when you log in. In this way, different users on the same computer can use different desktop environments.

Many different desktop environments are available to choose from in Linux. Here are some examples:

- GNOME—GNOME is the default desktop environment for Fedora, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, and many others. Think of it as a professional desktop environment, focusing on stability more than fancy effects.

- K Desktop Environment—KDE is probably the second most popular desktop environment for Linux. It has more bells and whistles than GNOME and offers more integrated applications. KDE is also available with Fedora, RHEL, Ubuntu, and many other Linux systems.

- Xfce—The Xfce desktop was one of the first lightweight desktop environments. It is good to use on older or less powerful computers. It is available with RHEL, Fedora, Ubuntu, and other Linux distributions.

- LXDE—The Lightweight X11 Desktop Environment (LXDE) was designed to be a fast-performing, energy-saving desktop environment. Often, LXDE is used on less-expensive devices (such as netbook computers) and on live media (such as a live CD or live USB stick). It is the default desktop for the KNOPPIX live CD distribution. Although LXDE is not included with RHEL, you can try it with Fedora or Ubuntu.

GNOME was originally designed to resemble the MAC OS desktop, while KDE was meant to emulate the Windows desktop environment. Because it is the most popular desktop environment, and the one most often used in business Linux systems, most desktop procedures and exercises in this book use the GNOME desktop. Using GNOME, however, still gives you the choice of several different Linux distributions.

Starting with the Fedora GNOME Desktop Live image

A live Linux ISO image is the quickest way to get a Linux system up and running so you can start trying it out. Depending on its size, the image can be burned to a CD, DVD, or USB drive and booted on your computer. With a Linux live image, you can have Linux take over the operation of your computer temporarily, without harming the contents of your hard drive.

If you have Windows installed, Linux just ignores it and uses Linux to control your computer. When you are finished with the Linux live image, you can reboot the computer, pop out the CD or DVD, and go back to running whatever operating system was installed on the hard disk.

To try out a GNOME desktop along with the descriptions in this section, I suggest you get a Fedora Live DVD (as described in Appendix A). Because a live DVD does all its work from the DVD and in memory, it runs slower than an installed Linux system. Also, although you can change files, add software, and otherwise configure your system, by default, the work you do disappears when you reboot, unless you explicitly save that data to your hard drive or external storage.

The fact that changes you make to the live environment go away on reboot is very good for trying out Linux, but not that great if you want an ongoing desktop or server system. For that reason, I recommend that if you have a spare computer, you install Linux permanently on that computer's hard disk to use with the rest of this book (as described in Chapter 9).

After you have a live CD or DVD in hand, do the following to get started:

- Get a computer. If you have a standard PC (32-bit or 64-bit) with a CD/DVD drive and at least 1GB of memory (RAM) and at least a 400-MHz processor, you are ready to start. (Just make sure the image you download matches your computer's architecture—a 64-bit medium does not run on a 32-bit computer.)

- Start the live CD/DVD. Insert the live CD/DVD or USB drive into your computer and reboot your computer. Depending on the boot order set on your computer, the live image might start up directly from the BIOS (the code that controls the computer before the operating system starts).

NOTE

If, instead of booting the live medium, your installed operating system starts up instead, you need to perform an additional step to start the live CD/DVD. Reboot again, and when you see the BIOS screen, look for some words that say something like “Boot Order.” The onscreen instructions may say to press the F12 or F1 key. Press that key immediately from the BIOS screen. Next, you should see a screen that shows available selections. Highlight an entry for CD/DVD or USB drive, and press Enter to boot the live image. If you don't see the drive there, you may need to go into BIOS setup and enable the CD/DVD or USB drive there.

- Start Fedora. If the selected drive is able to boot, you see a boot screen. For Fedora, with Start Fedora highlighted, press Enter to start the live medium.

- Begin using the desktop. For Fedora, the live medium lets you choose between installing Fedora or boots directly from the medium to a GNOME 3 desktop.

You can now proceed to the next section, “Using the GNOME 3 Desktop” (which includes information on using GNOME 3 in Fedora, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, and other operating systems). The section following that covers the GNOME 2 desktop.

Using the GNOME 3 Desktop

The GNOME 3 desktop offers a radical departure from its GNOME 2.x counterparts. GNOME 2.x is serviceable, but GNOME 3 is elegant. With GNOME 3, a Linux desktop now appears more like the graphical interfaces on mobile devices, with less focus on multiple mouse buttons and key combinations and more on mouse movement and one-click operations.

Instead of feeling structured and rigid, the GNOME 3 desktop seems to expand as you need it to. As a new application is run, its icon is added to the Dash. As you use the next workspace, a new one opens, ready for you to place more applications.

After the computer boots up

If you booted up a live image, when you reach the desktop, you are assigned as the Live System User for your username. For an installed system, you see the login screen, with user accounts on the system ready for you to select and enter a password. Log in with the username and password you have defined for your system.

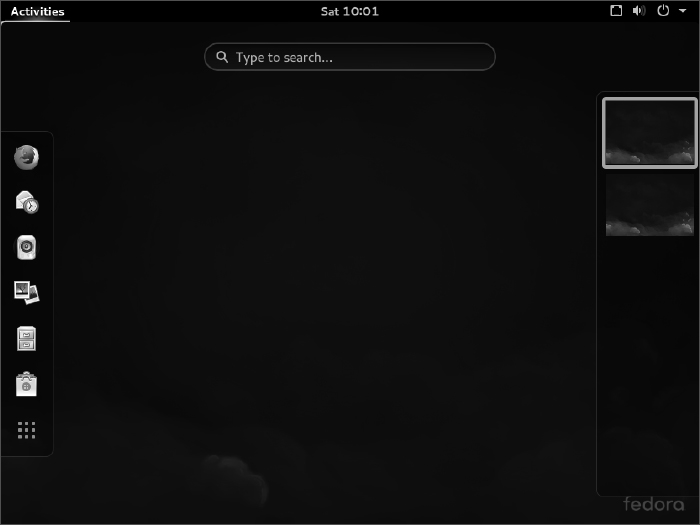

Figure 2.1 is an example of the GNOME 3 desktop screen that appears for Fedora. Press the Windows key (or move the mouse cursor to the upper-left corner of the desktop) to toggle between a blank desktop and the Overview screen.

FIGURE 2.1

Starting with the GNOME 3 desktop in Fedora.

There is very little on the GNOME 3 desktop when you start out. The top bar has the word “Activities” on the left, a clock in the middle, and some icons on the right for such things as adjusting audio volume, checking your network connection, and viewing the name of the current user. The Overview screen is where you can select to open applications, active windows, or different workspaces.

Navigating with the mouse

To get started, try navigating the GNOME 3 desktop with your mouse:

- Toggle activities and windows. Move your mouse cursor to the upper-left corner of the screen, near the Activities button. Each time you move there, your screen changes between showing you the windows you are actively using and a set of available Activities. (This has the same effect as pressing the Windows key.)

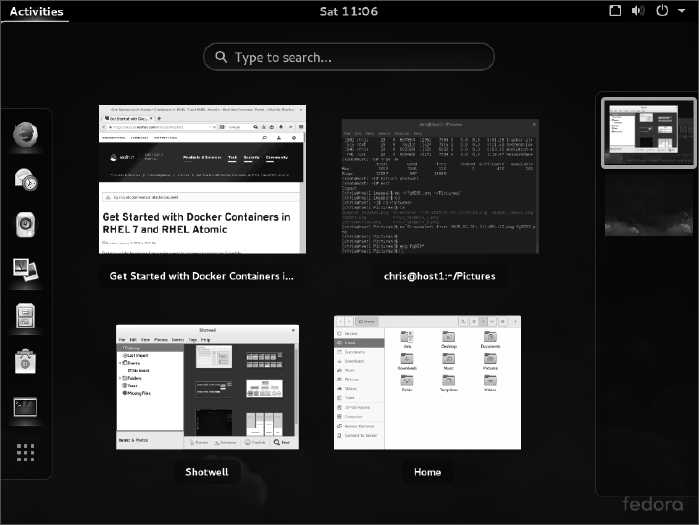

- Open windows from applications bar. Click to open some applications from the Dash on the left (Firefox, File Manager, Shotwell, or others). Move the mouse to the upper-left corner again, and toggle between showing all active windows minimized (Overview screen) and showing them overlapping (full-sized). Figure 2.2 shows an example of the miniature windows view.

FIGURE 2.2

Show all windows on the desktop minimized.

- Open applications from Applications list. From the Overview screen, select the Application button from the bottom of the left column (the button has nine dots in a box). The view changes to a set of icons representing the applications installed on your system, as shown in Figure 2.3.

Show the list of available applications.

- View additional applications. From the Applications screen, you can change the view of your applications in several ways, as well as launch them in different ways:

- Page through—To see icons representing applications that are not onscreen, use the mouse to click dots on the right to page through applications. If you have a wheel mouse, you can use that instead to scroll the icons.

- Frequent—Select the Frequent button on the bottom of the screen to see often-run applications or the All button to see all applications again.

- Launching an application—To start the application you want, left-click its icon to open the application in the current workspace. Right-click to open a menu that lets you choose to open a New Window, add or remove the application from Favorites (so the application's icon appears on the Dash), or Show Details about the application. Figure 2.4 shows an example of the menu.

- Open additional applications. Start up additional applications. Notice that as you open a new application, an icon representing that application appears in the Dash bar on the left. Here are other ways to start applications:

Click the middle mouse button to display an application's selection menu.

- Application icon—Click any application icon to open that application.

- Drop Dash icons on workspace—From the Windows view, you can drag any application icon from the Dash by pressing and holding the left mouse button on it and dragging that icon to any of the miniature workspaces on the right.

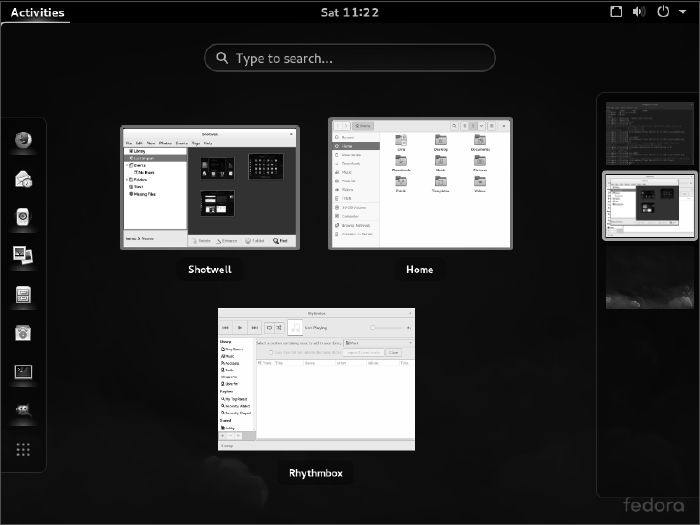

- Use multiple workspaces. Move the mouse to the upper-left corner again to show a minimized view of all windows. Notice all the applications on the right jammed into a small representation of one workspace while an additional workspace is empty. Drag and drop a few of the windows to an empty desktop space. Figure 2.5 shows what the small workspaces look like. Notice that an additional empty workspace is created each time the last empty one is used. You can drag and drop the miniature windows to any workspace and then select the workspace to view it.

- Use the window menu. Move the mouse to the upper-left corner of the screen to return to the active workspace (large window view). Right-click the title bar on a window to view the window menu. Try these actions from that menu:

- Minimize—Remove window temporarily from view.

- Maximize—Expand window to maximum size.

- Move—Change window to moving mode. Moving your mouse moves the window. Click to fix the window to a spot.

- Resize—Change the window to resize mode. Moving your mouse resizes the window. Click to keep the size.

- Workspace selections—Several selections let you use workspaces in different ways. Select Always on Top to make the current window always on top of other windows in the workspace. Select Always on Visible Workspace to always show the window on the workspace that is visible. Or select Move to Workspace Up or Move to Workspace Down to move the window to the workspace above or below, respectively.

As new desktops are used, additional ones appear on the right.

If you don't feel comfortable navigating GNOME 3 with your mouse, or if you don't have a mouse, the next section helps you navigate the desktop from the keyboard.

Navigating with the keyboard

If you prefer to keep your hands on the keyboard, you can work with the GNOME 3 desktop directly from the keyboard in a number of ways, including these:

- Windows key—Presses the Windows key on the keyboard. On most PC keyboards, this is the key with the Microsoft Windows logo on it next to the Alt key. This toggles the mini-window (Overview) and active-window (current workspace) views. Many people use this key often.

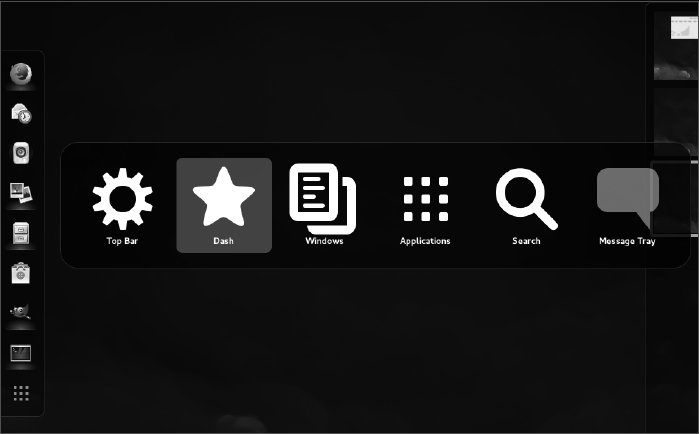

- Select different views—From the Windows or Applications view, hold Ctrl+Alt+Tab to see a menu of the different views (see Figure 2.6). Still holding the Ctrl+Alt keys, press Tab again to highlight one of the following icons from the menu and release to select it:

- Top bar—Keeps the current view.

Press Ctrl+Alt+Tab to display additional desktop areas to select.

- Dash—Highlights the first application in the application bar on the left. Use arrow keys to move up and down that menu, and press Enter to open the highlighted application.

- Windows—Selects the Windows view.

- Applications—Selects the Applications view.

- Search—Highlights the search box. Type a few letters to show only icons for applications that contain the letters you type. When you have typed enough letters to uniquely identify the application you want, press Enter to launch the application.

- Message tray—Reveals the bottom message tray. This tray lets you view notifications and open removable media.

- Top bar—Keeps the current view.

- Select an active window—Return to any of your workspaces (press the Windows key if you are not already on an active workspace). Press Alt+Tab to see a list of all active windows (see Figure 2.7). Continue to hold the Alt key as you press the Tab key (or right or left arrow keys) to highlight the application you want from the list of active desktop application windows. If an application has multiple windows open, press Alt+` (backtick, located above the Tab key) to choose among those sub-windows. Release the Alt key to select it.

Press Alt+Tab to select which running application to go to.

- Launch a command or application—From any active workspace, you can launch a Linux command or a graphical application. Here are some examples:

- Applications—From the Overview screen, press Ctrl+Alt+Tab and continue to press Tab until the Applications icon is highlighted; then release Ctrl+Alt. The Applications view appears, with the first icon highlighted. Use the Tab key or arrow keys (up, down, right, and left) to highlight the application icon you want, and press Enter.

- Command box—If you know the name (or part of a name) of a command you want to run, press Alt+F2 to display a command box. Type the name of the command you want to run into the box (try gnome-calculator to open a calculator application, for example).

- Search box—From the Overview screen, press Ctrl+Alt+Tab and continue to press Tab until the magnifying glass (Search) icon is highlighted; then release Ctrl+Alt. In the search box now highlighted, type a few letters in an application's name or description (type scr to see what you get). Keep typing until the application you want is highlighted (in this case, Screenshot), and press Enter to launch it.

- Dash—From the Overview screen, press Ctrl+Alt+Tab and continue to press Tab until the star (Dash) icon is highlighted; then release Ctrl+Alt. From the Dash, move the up and down arrows to highlight an application you want to launch, and press Enter.

- Escape—When you are stuck in an action you don't want to complete, try pressing the Esc key. For example, after pressing Alt+F2 (to enter a command), opening an icon from the top bar, or going to an overview page, pressing Esc returns you to the active window on the active desktop.

I hope you now feel comfortable navigating the GNOME 3 desktop. Next, you can try running some useful and fun desktop applications from GNOME 3.

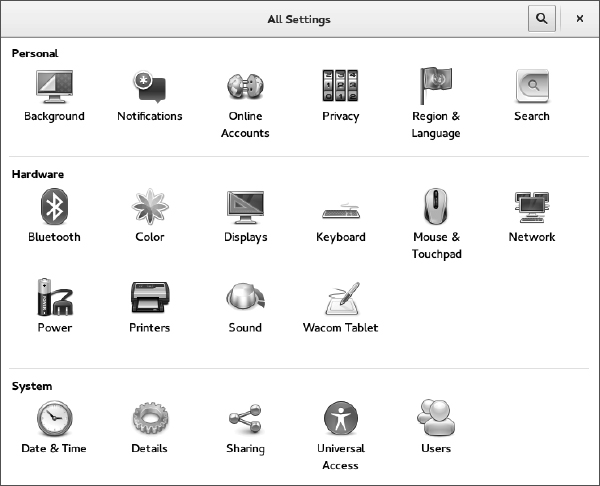

Setting up the GNOME 3 desktop

Much of what you need GNOME 3 to do for you is set up automatically. However, you need to make a few tweaks to get the desktop the way you want. Most of these setup activities are available from the System Settings window (see Figure 2.8). Open the Settings icon from the Applications list.

FIGURE 2.8

Change desktop settings from the System Settings window.

Here are some suggestions for configuring a GNOME 3 desktop:

- Configure networking—A wired network connection is often configured automatically when you boot up your Fedora system. For wireless, you probably have to select your wireless network and add a password when prompted. An icon in the top bar lets you do any wired or wireless network configuration you need to do. Refer to Chapter 14, “Administering Networking,” for further information on configuring networking.

- Personal settings—Tools in this group let you change your desktop background (Background), use different online accounts (Online Accounts), and set your language and date and currency format based on region (Region and Language) and screen locking (Screen). To change your background, open the System Settings window, select Background, and then select from the available Wallpapers. To add your own Background, download a wallpaper image you like to your Pictures folder, click the Wallpapers box to change it to Pictures folder, and choose the image you want.

- Bluetooth—If your computer has Bluetooth hardware, you can enable that device to communicate with other Bluetooth devices (such as a Bluetooth headset or printer).

- Printers—Instead of using the System Settings window to configure a printer, refer to Chapter 16, “Configuring a Print server,” for information on setting up a printer using the CUPS service.

- Sound—Click the Sound settings button to adjust sound input and output devices on your system.

Extending the GNOME 3 desktop

If the GNOME 3 shell doesn't do everything you like, don't despair. You can add extensions to provide additional functionality to GNOME 3. Also, a GNOME Tweak Tool lets you change advanced settings in GNOME 3.

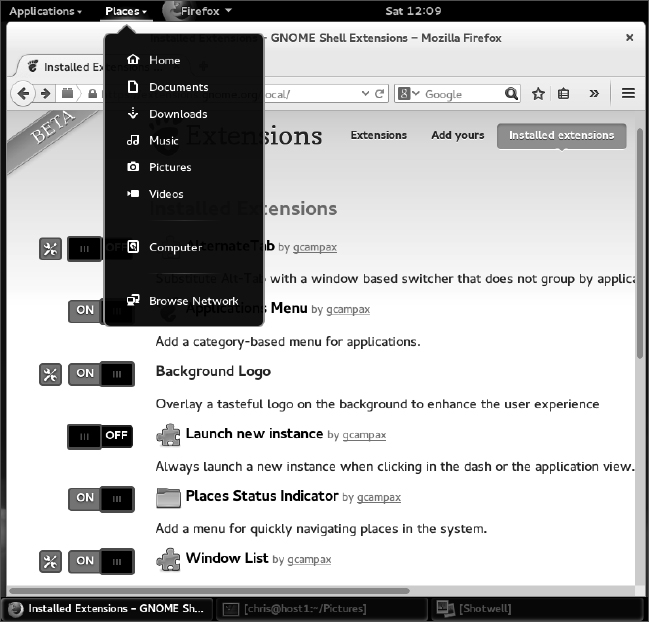

Using GNOME shell extensions

GNOME shell extensions are available to change the way your GNOME desktop looks and behaves. Visit the GNOME Shell Extensions site (http://extensions.gnome.org) from your Firefox browser on your GNOME 3 desktop. That site tells you what extensions you have installed and which ones are available for you to install (you must select to allow the site to see those extensions).

Because the extensions page knows what extensions you have and the version of GNOME 3 you are running, it can present only those extensions that are compatible with your system. Many of the extensions help you add back in features from GNOME 2, including these:

- Applications Menu—Adds an Applications menu to the top panel, just as it was in GNOME 2.

- Places Status Indicator—Adds a systems status menu, similar to the Places menu in GNOME 2, to let you quickly navigate to useful folders on your system.

- Window list—Adds a list of active windows to the top panel, similar to the Window list that appeared on the bottom panel in GNOME 2.

To install an extension, simply select the ON button next to the name. Or you can click the extension name from the list to see the extension's page, and click the button on that page from OFF to ON. Click Install when you are asked if you want to download and install the extension. The extension is then added to your desktop.

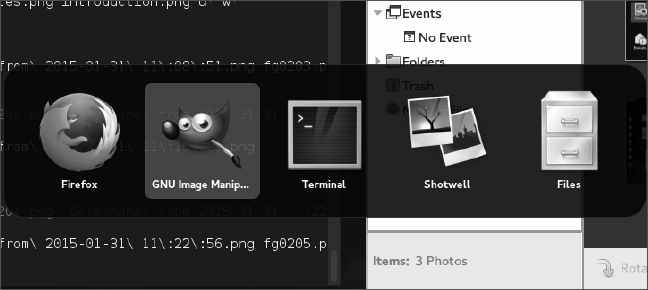

Figure 2.9 shows an example of the Applications Menu (the GNOME foot icon), Window List (showing several active applications icons), and Places Status Indicator (with folders displayed from a drop-down menu) extensions installed.

FIGURE 2.9

Extensions add features to the GNOME 3 desktop.

More than 100 GNOME shell extensions are available now, and more are being added all the time. Other popular extensions include Notifications Alert (which alerts you of unread messages), Presentation Mode (which prevents the screensaver from coming on when you are giving a presentation), and Music Integration (which integrates popular music players into GNOME 3 so you are alerted about songs being played).

Because the Extensions site can keep track of your extensions, you can click the Installed extensions button at the top of the page and see every extension that is installed. You can turn the extensions off and on from there and even delete them permanently.

Using the GNOME Tweak Tool

If you don't like the way some of the built-in features of GNOME 3 behave, you can change many of them with the GNOME Tweak Tool. This tool is not installed by default with the Fedora GNOME Live CD, but you can add it by installing the gnome-tweak-tool package. (See Chapter 10, “Getting and Managing Software,” for information on how to install software packages in Fedora.)

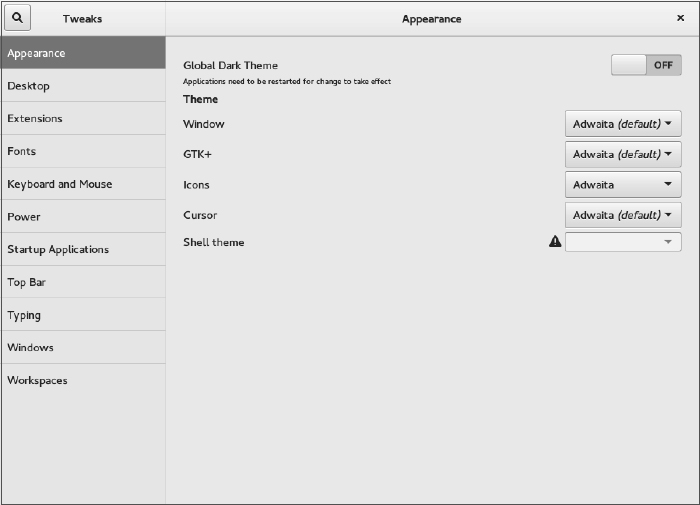

After installation, the GNOME Tweak Tool is available by launching the Advanced Settings icon from your Applications screen. Start with the Desktop category to consider what you might want to change in GNOME 3. Figure 2.10 shows the Tweak Tool (Advanced Settings window) displaying Appearance settings.

FIGURE 2.10

Change desktop settings using the GNOME Tweak Tool (Advanced Settings).

If fonts are too small for you, select the Fonts category and click the plus sign next to the Scaling Factor box to increase the font size. Or change fonts individually for documents, window titles, or monospace fonts.

Under Top Bar settings, you can change how clock information is displayed in the top bar or set whether to show the week number in the calendar. To change the look of the desktop, select the Appearance category and change the Icons theme and GTK+ theme as you like from drop-down boxes.

Starting with desktop applications

The Fedora GNOME 3 desktop live DVD comes with some cool applications you can start using immediately. To use GNOME 3 as your everyday desktop, you should install it permanently to your computer's hard disk and add the applications you need (a word processor, image editor, drawing application, and so on). If you are just getting started, the following sections list some cool applications to try out.

Managing files and folders with Nautilus

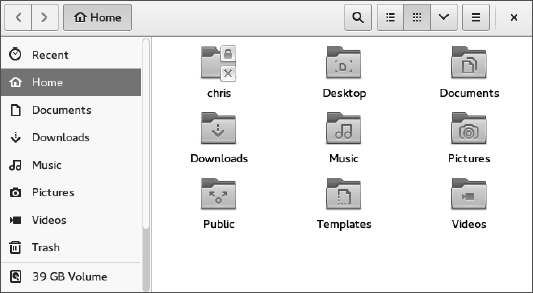

To move, copy, delete, rename, and otherwise organize files and folders in GNOME 3, you can use the Nautilus file manager. Nautilus comes with the GNOME desktop and works like other file managers you may use in Windows or Mac.

To open Nautilus, click the Files icon from the GNOME Dash or Applications list. Your user account starts with a set of folders designed to hold the most common types of content: Music, Pictures, Videos, and the like. These are all stored in what is referred to as your Home directory. Figure 2.11 shows Nautilus open to a home directory.

FIGURE 2.11

Manage files and folders from the Nautilus window.

When you want to save files you downloaded from the Internet or created with a word processor, you can organize them into these folders. You can create new folders as needed, drag and drop files and folders to copy and move them, and delete them.

Because Nautilus is not much different from most file managers you have used on other computer systems, this chapter does not go into detail about how to use drag-and-drop and traverse folders to find your content. However, I do want to make a few observations that may not be obvious about how to use Nautilus:

- Home folder—You have complete control over the files and folders you create in your Home folder. Most other parts of the filesystem are not accessible to you as a regular user.

- Filesystem organization—Although it appears under the name Home, your home folder is actually located in the filesystem under the /home folder in a folder named after your username—for example, /home/liveuser or /home/chris. In the next few chapters, you learn how the filesystem is organized (especially in relation to the Linux command shell).

- Working with files and folders—Right-click a file or folder icon to see how you can act on it. For example, you can copy, cut, move to trash (delete), or open any file or folder icon.

- Creating folders—To create a new folder, right-click in a folder window and select New Folder. Type the new folder name over the highlighted Untitled Folder, and press Enter to name the folder.

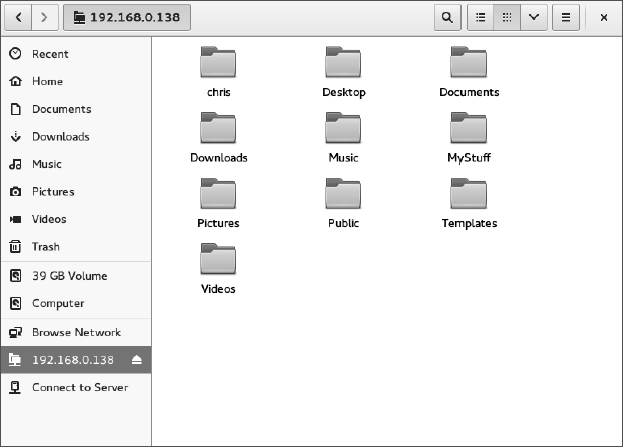

- Accessing remote content—Nautilus can display content from remote servers as well as the local filesystem. In Nautilus, select Connect to Server from the file menu. You can connect to a remote server via SSH (secure shell), FTP with login, Public FTP, Windows share, WebDav (HTTP), or Secure WebDav (HTTPS). Add appropriate user and password information as needed, and the content of the remote server appears in the Nautilus window. Figure 2.12 shows an example of a Nautilus window displaying folders from a remote server over SSH protocol (ssh://192.168.0.138).

Installing and managing additional software

The Fedora Live Desktop comes with a web browser (Firefox), a file manager (Nautilus), and a few other common applications. However, there are many other useful applications that, because of their size, just wouldn't fit on a live CD. If you install the live Fedora Workstation to your hard disk (as described in Chapter 9), you almost certainly will want to add some more software.

NOTE

You can try installing software if you are running the live medium. But keep in mind that because writeable space on a live medium uses virtual memory (RAM), that space is limited and can easily run out. Also, when you reboot your system, anything you install disappears.

When Fedora is installed, it is automatically configured to connect your system to the huge Fedora software repository that is available on the Internet. As long as you have an Internet connection, you can run the Add/Remove software tool to download and install any of thousands of Fedora packages.

FIGURE 2.12

Access remote folders using the Nautilus Connect to Server feature.

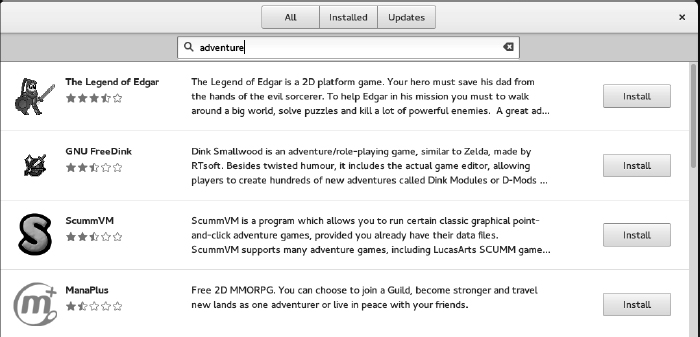

Although the entire facility for managing software in Fedora (the yum and rpm features) is described in detail in Chapter 10, “Getting and Managing Software,” you can start installing some software packages without knowing much about how the feature works. Begin by going to the applications screen and opening the Software window.

With the Software window open, you can select the applications you want to install by searching (type the name into the Find box) or choosing a category. Each category offers packages sorted by subcategories and featured packages in that category. Figure 2.13 shows the results of a search for the word adventure in the description or name of a package.

You can read a description of each package that comes up in your search. When you are ready, click Install to install the package and any dependent packages needed to make it work.

By searching for and installing some common desktop applications, you should be able to start using your desktop effectively. Refer to Chapter 10 for details on how to add software repositories and use yum and rpm commands to manage software in Fedora and Red Hat Enterprise Linux.

FIGURE 2.13

Download and install software from the huge Fedora repository.

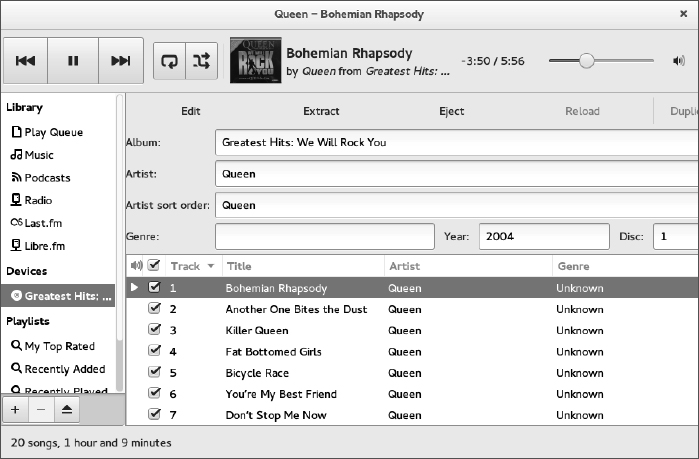

Playing music with Rhythmbox

Rhythmbox is the music player that comes on the Fedora GNOME Live Desktop. You can launch Rhythmbox from the GNOME 3 Dash and immediately play music CDs, podcasts, or Internet radio shows. You can import audio files in WAV and Ogg Vorbis formats, or add plug-ins for MP3 or other audio formats.

Figure 2.14 shows an example of the Rhythmbox window with music playing from an imported audio library.

Here are a few ways you can get started with Rhythmbox:

- Radio—Double-click the Radio selection under Library and choose a radio station from the list that appears to the right.

- Podcasts—Search for podcasts on the Internet and find the URL for one that interests you. Right-click the Podcasts entry and select New Podcast Feed. Paste or type in the URL to the podcast, and click Add. A list of podcasts from the site you selected appears to the right. Double-click the one you want to listen to.

- Audio CDs—Insert an audio CD, and press Play when it appears in the Rhythmbox window. Rhythmbox also lets you rip and burn audio CDs.

- Audio files—Rhythmbox can play WAV and Ogg Vorbis files. By adding plug-ins, you can play many other audio formats, including MP3. Because there are patent issues related to the MP3 format, the ability to play MP3s is not included with Fedora. In Chapter 10, I describe how to get software you need that is not in the repository of your Linux distribution.

FIGURE 2.14

Play music, podcasts, and Internet radio from Rhythmbox.

Plug-ins are available for Rhythmbox to get cover art, show information about artists and songs, add support for music services (such as Last.fm and Magnatune), and fetch song lyrics.

Stopping the GNOME 3 desktop

When you are finished with your GNOME 3 session, select the down arrow button in the upper-right corner of the top bar. From there, you can choose the On/Off button, which allows you to Log Out, Suspend your session, or switch to a different user account without logging out.

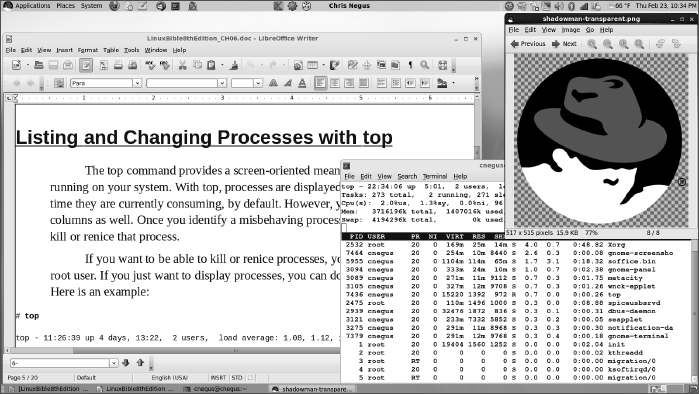

Using the GNOME 2 Desktop

The GNOME 2 desktop is the default desktop interface used up through Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6. It is well-known, stable, and perhaps a bit boring.

GNOME 2 desktops provide the more standard menus, panels, icons, and workspaces. If you are using a Red Hat Enterprise Linux system up to RHEL 6 or an older Fedora or Ubuntu distribution, you are probably looking at a GNOME 2 desktop.

This section provides a tour of GNOME 2, along with some opportunities for sprucing it up a bit. Recent GNOME releases include advances in 3D effects (see “3D effects with AIGLX” later in this chapter) and improved usability features that I'll show you as well.

To use your GNOME desktop, you should become familiar with the following components:

- Metacity (window manager)—The default window manager for GNOME 2 is Metacity. Metacity configuration options let you control such things as themes, window borders, and controls used on your desktop.

- Compiz (window manager)—You can enable this window manager in GNOME to provide 3D desktop effects.

- Nautilus (file manager/graphical shell)—When you open a folder (by double-clicking the Home icon on your desktop, for example), the Nautilus window opens and displays the contents of the selected folder. Nautilus can also display other types of content, such as shared folders from Windows computers on the network (using SMB).

- GNOME panels (application/task launcher)—These panels, which line the top and bottom of your screen, are designed to make it convenient for you to launch the applications you use, manage running applications, and work with multiple virtual desktops. By default, the top panel contains menu buttons (Applications, Places, and System), desktop application launchers (Evolution email and Firefox web browser), a workspace switcher (for managing four virtual desktops), and a clock. Icons appear in the panel when you need software updates or SELinux detects a problem. The bottom panel has a Show Desktop button, window lists, a trash can, and a workspace switcher.

- Desktop area—The windows and icons you use are arranged on the desktop area, which supports drag-and-drop between applications, a desktop menu (right-click to see it), and icons for launching applications. A Computer icon consolidates CD drives, floppy drives, the filesystem, and shared network resources in one place.

GNOME also includes a set of Preferences windows that enable you to configure different aspects of your desktop. You can change backgrounds, colors, fonts, keyboard shortcuts, and other features related to the look and behavior of the desktop. Figure 2.15 shows how the GNOME 2 desktop environment appears the first time you log in, with a few windows added to the screen.

The desktop shown in Figure 2.15 is for Red Hat Enterprise Linux. The following sections provide details on using the GNOME 2 desktop.

Using the Metacity window manager

The Metacity window manager seems to have been chosen as the default window manager for GNOME because of its simplicity. The creator of Metacity refers to it as a “boring window manager for the adult in you” and then goes on to compare other window managers to colorful, sugary cereal, whereas Metacity is characterized as Cheerios.

NOTE

To use 3D effects, your best solution is to use the Compiz window manager, described later in this chapter. You can't do much with Metacity (except get your work done efficiently). You assign new themes to Metacity and change colors and window decorations through the GNOME preferences (described later). Only a few Metacity themes exist, but expect the number to grow.

Basic Metacity functions that might interest you are keyboard shortcuts and the workspace switcher. Table 2.1 shows keyboard shortcuts to get around the Metacity window manager.

FIGURE 2.15

The GNOME 2 desktop environment.

| Actions | Keystrokes |

| Cycle backward, without pop-up icons | Alt+Shift+Esc |

| Cycle backward among panels | Alt+Ctrl+Shift+Tab |

| Close menu | Esc |

You can use other keyboard shortcuts with the window manager as well. Select System  Preferences

Preferences  Keyboard Shortcuts to see a list of shortcuts, such as the following:

Keyboard Shortcuts to see a list of shortcuts, such as the following:

- Run Dialog—To run a command to launch an application from the desktop by command name, press Alt+F2. From the dialog box that appears, type the command and press Enter. For example, type gedit to run a simple graphical text editor.

- Lock Screen—If you want to step away from your screen and lock it, press Ctrl+Alt+L. You need to type your user password to open the screen again.

- Show Main Menu—To open an application from the Applications, Places, or System menu, press Alt+F1. Then use the up and down arrow keys to select from the current menu, or use the right and left arrow keys to select from other menus.

- Print Screen—Press the Print Screen key to take a picture of the entire desktop. Press Alt+Print Screen to take a picture of the current window.

Another Metacity feature of interest is the workspace switcher. Four virtual workspaces appear in the Workspace Switcher on the GNOME 2 panel. You can do the following with the Workspace Switcher:

- Choose current workspace—Four virtual workspaces appear in the Workspace Switcher. Click any of the four virtual workspaces to make it your current workspace.

- Move windows to other workspaces—Click any window, each represented by a tiny rectangle in a workspace, to drag and drop it to another workspace. Likewise, you can drag an application from the Window list to move that application to another workspace.

- Add more workspaces—Right-click the Workspace Switcher, and select Preferences. You can add workspaces (up to 32).

- Name workspaces—Right-click the Workspace Switcher, and select Preferences. Click in the Workspaces pane to change names of workspaces to any names you choose.

You can view and change information about Metacity controls and settings using the gconf-editor window (type gconf-editor from a Terminal window). As the window says, it is not the recommended way to change preferences, so when possible, you should change the desktop through GNOME 2 preferences. However, gconf-editor is a good way to see descriptions of each Metacity feature.

From the gconf-editor window, select apps  metacity, and choose from general, global_keybindings, keybindings_commands, window_keybindings, and workspace_names. Click each key to see its value, along with short and long descriptions of the key.

metacity, and choose from general, global_keybindings, keybindings_commands, window_keybindings, and workspace_names. Click each key to see its value, along with short and long descriptions of the key.

Changing GNOME's appearance

You can change the general look of your GNOME desktop by selecting System  Preferences

Preferences  Appearance. From the Appearance Preferences window, select from three tabs:

Appearance. From the Appearance Preferences window, select from three tabs:

- Theme—Entire themes are available for the GNOME 2 desktop that change the colors, icons, fonts, and other aspects of the desktop. Several different themes come with the GNOME desktop, which you can simply select from this tab to use. Or click Get more themes online to choose from a variety of available themes.

- Background—To change your desktop background, select from a list of backgrounds on this tab to have the one you choose immediately take effect. To add a different background, put the background you want on your system (perhaps download one by selecting Get more backgrounds online and downloading it to your Pictures folder). Then click Add, and select the image from your Pictures folder.

- Fonts—Different fonts can be selected to use by default with your applications, documents, desktop, window title bar, and for fixed width.

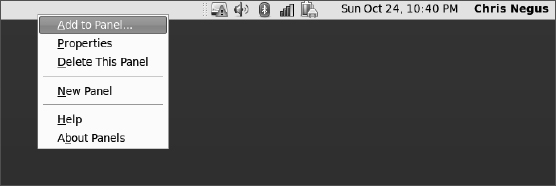

Using the GNOME panels

The GNOME panels are placed on the top and bottom of the GNOME desktop. From those panels, you can start applications (from buttons or menus), see what programs are active, and monitor how your system is running. You can also change the top and bottom panels in many ways—by adding applications or monitors or by changing the placement or behavior of the panel, for example.

Right-click any open space on either panel to see the Panel menu. Figure 2.16 shows the Panel menu on the top.

FIGURE 2.16

The GNOME Panel menu.

From GNOME's Panel menu, you can choose from a variety of functions, including these:

- Use the menus

- The Applications menu displays most of the applications and system tools you will use from the desktop.

- The Places menu lets you select places to go, such as the Desktop folder, home folder, removable media, or network locations.

- The System menu lets you change preferences and system settings, as well as get other information about GNOME.

- Add to Panel—Add an applet, menu, launcher, drawer, or button.

- Properties—Change the panel's position, size, and background properties.

- Delete This Panel—Delete the current panel.

- New Panel—Add panels to your desktop in different styles and locations.

You can also work with items on a panel. For example, you can do the following:

- Move items—To move an item on a panel, right-click it, select Move, and drag and drop it to a new position.

- Resize items—You can resize some elements, such as the Window list, by clicking an edge and dragging it to the new size.

- Use the Window list—Tasks running on the desktop appear in the Window list area. Click a task to minimize or maximize it.

The following sections describe some things you can do with the GNOME panel.

Using the Applications and System menus

Click Applications on the panel, and you see categories of applications and system tools that you can select. Click the application you want to launch. To add an item from a menu so that it can launch from the panel, drag and drop the item you want to the panel.

You can add items to your GNOME 2 menus. To do that, right-click any of the menu names and select Edit Menus. The window that appears lets you add or delete menus associated with the Applications and System menus. You can also add items to launch from those menus by selecting New Item and typing the name, command, and comment for the item.

Adding an applet

You can run several small applications, called applets, directly on the GNOME panel. These applications can show information you may want to see on an ongoing basis or may just provide some amusement. To see what applets are available and to add applets that you want to your panel, follow these steps:

- Right-click an open space in the panel so the Panel menu appears.

- Click Add to Panel. An Add to Panel window appears.

- Select from among several dozen applets, including a clock, dictionary lookup, stock ticker, and weather report. The applet you select appears on the panel, ready for you to use.

Figure 2.17 shows (from left to right) eyes, system monitor, weather report, terminal, and Wanda the fish.

Placing applets on the panel makes accessing them easy.

After an applet is installed, right-click it on the panel to see what options are available. For example, select Preferences for the stock ticker, and you can add or delete stocks whose prices you want to monitor. If you don't like the applet's location, right-click it, click Move, slide the mouse until the applet is where you want it (even to another panel), and click to set its location.

If you no longer want an applet to appear on the panel, right-click it, and click Remove From Panel. The icon representing the applet disappears. If you find that you have run out of room on your panel, you can add a new panel to another part of the screen, as described in the next section.

Adding another panel

If you run out of space on the top or bottom panels, you can add more panels to your desktop. You can have several panels on your GNOME 2 desktop. You can add panels that run along the entire bottom, top, or side of the screen. To add a panel, follow these steps:

- Right-click an open space in the panel so the Panel menu appears.

- Click New Panel. A new panel appears on the side of the screen.

- Right-click an open space in the new panel, and select Properties.

- From the Panel Properties, select where you want the panel from the Orientation box (Top, Bottom, Left, or Right).

After you've added a panel, you can add applets or application launchers to it as you did to the default panel. To remove a panel, right-click it and select Delete This Panel.

Adding an application launcher

Icons on your panel represent a web browser and several office productivity applications. You can add your own icons to launch applications from the panel as well. To add a new application launcher to the panel, follow these steps:

- Right-click in an open space on the panel.

- Click Add to Panel

Application Launcher from the menu. All application categories from your Applications and System menus appear.

Application Launcher from the menu. All application categories from your Applications and System menus appear. - Select the arrow next to the category of application you want, and then select Add. An icon representing the application appears on the panel.

To launch the application you just added, simply click the icon on the panel.

If the application you want to launch is not on one of your menus, you can build a launcher yourself as follows:

- Right-click in an open space on the panel.

- Click Add to Panel

Custom Application Launcher

Custom Application Launcher  Add. The Create Launcher window appears.

Add. The Create Launcher window appears. - Provide the following information for the application you want to add:

- Type—Select Application (to launch a regular GUI application) or Application in Terminal. Use Application in Terminal if the application is a character-based or ncurses application. (Applications written using the ncurses library run in a Terminal window but offer screen-oriented mouse and keyboard controls.)

- Name—Choose a name to identify the application (this appears in the tooltip when your mouse is over the icon).

- Command—This identifies the command line that is run when the application is launched. Use the full pathname, plus any required options.

- Comment—Enter a comment describing the application. It also appears when you later move your mouse over the launcher.

- Click the Icon box (it might say No Icon), select one of the icons shown, and click OK. Alternatively, you can browse your filesystem to choose an icon.

- Click OK.

The application should now appear in the panel. Click it to start the application.

NOTE

Icons available to represent your application are contained in the /usr/share/pixmaps directory. These icons are in either.png or .xpm formats. If there isn't an icon in the directory you want to use, create your own (in one of those two formats) and assign it to the application.

Adding a drawer

A drawer is an icon that you can click to display other icons representing menus, applets, and launchers; it behaves just like a panel. Essentially, any item you can add to a panel you can add to a drawer. By adding a drawer to your GNOME panel, you can include several applets and launchers that together take up the space of only one icon. Click the drawer to show the applets and launchers as if they were being pulled out of a drawer icon on the panel.

To add a drawer to your panel, right-click the panel and select Add to Panel  Drawer. A drawer appears on the panel. Right-click it, and add applets or launchers to it as you would to a panel. Click the icon again to retract the drawer.

Drawer. A drawer appears on the panel. Right-click it, and add applets or launchers to it as you would to a panel. Click the icon again to retract the drawer.

Figure 2.18 shows a portion of the panel with an open drawer that includes an icon for launching a weather report, sticky notes, and a stock monitor.

FIGURE 2.18

Add launchers or applets to a drawer on your GNOME 2 panel.

Changing panel properties

You can change the orientation, size, hiding policy, and background properties of your desktop panels. To open the Panel Properties window that applies to a specific panel, right-click an open space on the panel and choose Properties. The Panel Properties window that appears includes the following values:

- Orientation—Move the panel to a different location on the screen by clicking a new position.

- Size—Select the size of your panel by choosing its height in pixels (48 pixels by default).

- Expand—Select this check box to have the panel expand to fill the entire side, or clear the check box to make the panel only as wide as the applets it contains.

- AutoHide—Select whether a panel is automatically hidden (appearing only when the mouse pointer is in the area).

- Show Hide buttons—Choose whether the Hide/Unhide buttons (with pixmap arrows on them) appear on the edges of the panel.

- Arrows on hide buttons—If you select Show Hide Buttons, you can choose to have arrows on those buttons.

- Background—From the Background tab, you can assign a color to the background of the panel, assign a pixmap image, or just leave the default (which is based on the current system theme). Click the Background Image check box if you want to select an Image for the background, and then select an image, such as a tile from /usr/share/backgrounds/tiles or another directory.

TIP

I usually turn on the AutoHide feature and turn off the Hide buttons. Using AutoHide gives you more desktop space to work with. When you move your mouse to the edge where the panel is, the panel pops up–so you don't need Hide buttons.

Adding 3D effects with AIGLX

Several initiatives have made strides in recent years to bring 3D desktop effects to Linux. Ubuntu, openSUSE, and Fedora used AIGLX (http://fedoraproject.org/wiki/RenderingProject/aiglx).

The goal of the Accelerated Indirect GLX project (AIGLX) is to add 3D effects to everyday desktop systems. It does this by implementing OpenGL (http://opengl.org) accelerated effects using the Mesa (http://www.mesa3d.org) open source OpenGL implementation.

Currently, AIGLX supports a limited set of video cards and implements only a few 3D effects, but it does offer some insight into the eye candy that is in the works.

If your video card was properly detected and configured, you may be able to simply turn on the Desktop Effects feature to see the effects that have been implemented so far. To turn on Desktop Effects, select System  Preferences

Preferences  Desktop Effects. When the Desktop Effects window appears, select Compiz. (If the selection is not available, install the compiz package.)

Desktop Effects. When the Desktop Effects window appears, select Compiz. (If the selection is not available, install the compiz package.)

Enabling Compiz does the following:

- Starts Compiz—Stops the current window manager and starts the Compiz window manager.

- Enables the Windows Wobble When Moved effect—With this effect on, when you grab the title bar of the window to move it, the window wobbles as it moves. Menus and other items that open on the desktop also wobble.

- Enables the Workspaces on a Cube effect—Drag a window from the desktop to the right or the left, and the desktop rotates like a cube, with each of your desktop workspaces appearing as a side of that cube. Drop the window on the workspace where you want it to go. You can also click the Workspace Switcher applet in the bottom panel to rotate the cube to display different workspaces.

Other nice desktop effects result from using the Alt+Tab keys to tab among different running windows. As you press Alt+Tab, a thumbnail of each window scrolls across the screen as the window it represents is highlighted.

Figure 2.19 shows an example of a Compiz desktop with AIGLX enabled. The figure illustrates a web browser window being moved from one workspace to another as those workspaces rotate on a cube.

The following are some interesting effects you can get with your 3D AIGLX desktop:

Rotate workspaces on a cube with AIGLX desktop effects enabled.

- Spin cube—Hold Ctrl+Alt keys, and press the right and left arrow keys. The desktop cube spins to each successive workspace (forward or back).

- Slowly rotate cube—Hold the Ctrl+Alt keys, press and hold the left mouse button, and move the mouse around on the screen. The cube moves slowly with the mouse among the workspaces.

- Scale and separate windows—If your desktop is cluttered, hold Ctrl+Alt and press the up arrow key. Windows shrink down and separate on the desktop. Still holding Ctrl+Alt, use your arrow keys to highlight the window you want and release the keys to have that window come to the surface.

- Tab through windows—Hold the Alt key, and press the Tab key. You see reduced versions of all your windows in a strip in the middle of your screen, with the current window highlighted in the middle. Still holding the Alt key, press Tab or Shift+Tab to move forward or backward through the windows. Release the keys when the one you want is highlighted.

- Scale and separate workspaces—Hold Ctrl+Alt, and press the down arrow key to see reduced images of the workspace shown on a strip. Still holding Ctrl+Alt, use the right and left arrow keys to move among the different workspaces. Release the keys when the workspace you want is highlighted.

- Send current window to next workspace—Hold Ctrl+Alt+Shift keys together, and press the left and right arrow keys. The next workspace to the left or right, respectively, appears on the current desktop.

- Slide windows around—Press and hold the left mouse button on the window title bar, and then press the left, right, up, or down arrow keys to slide the current window around on the screen.

If you get tired of wobbling windows and spinning cubes, you can easily turn off the AIGLX 3D effects and return to using Metacity as the window manager. Select System  Preferences

Preferences  Desktop Effects again, and toggle off the Enable Desktop Effects button to turn off the feature.

Desktop Effects again, and toggle off the Enable Desktop Effects button to turn off the feature.

If you have a supported video card, but find that you cannot turn on the Desktop Effects, check that your X server started properly. In particular, make sure that your /etc/X11/xorg.conf file is properly configured. Make sure that dri and glx are loaded in the Module section. Also, add an extensions section anywhere in the file (typically at the end of the file) that appears as follows:

Section "extensions" Option "Composite" EndSection

Another option is to add the following line to the /etc/X11/xorg.conf file in the Device section:

Option "XAANoOffscreenPixmaps"

The XAANoOffscreenPixmaps option improves performance. Check your /var/log/Xorg.log file to make sure that DRI and AIGLX features were started correctly. The messages in that file can help you debug other problems as well.

Summary

The GNOME desktop environment has become the default desktop environment for many Linux systems, including Fedora and RHEL. The GNOME 3 desktop (now used in Fedora and Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7) is a modern, elegant desktop, designed to match the types of interfaces available on many of today's mobile devices. The GNOME 2 desktop (used through RHEL 6) provides a more traditional desktop experience.

Besides GNOME desktops, you can try out other popular and useful desktop environments. The K Desktop Environment (KDE) offers many more bells and whistles than GNOME and is used by default in several Linux distributions. Netbooks and live CD distributions sometimes use the LXDE or Xfce desktops.

Now that you have a grasp of how to get and use a Linux desktop, it's time to start digging into the more professional administrative interfaces. Chapter 3 introduces you to the Linux command-line shell interface.

Exercises

Use these exercises to test your skill in using a GNOME desktop. You can use either a GNOME 2.x (Red Hat Enterprise Linux up until RHEL 6.x) or GNOME 3.x (Fedora 16 or later or Ubuntu up to 11.10, or later using the Ubuntu GNOME project) desktop. If you are stuck, solutions to the tasks for both the GNOME 2 and GNOME 3 desktops are shown in Appendix B.

- Obtain a Linux system with either a GNOME 2 or GNOME 3 desktop available. Start the system, and log in to a GNOME desktop.

- Launch the Firefox web browser, and go to the GNOME home page (http://gnome.org).

- Pick a background you like from the GNOME art site (http://gnome-look.org/), download it to your Pictures folder, and select it as your current background.

- Start a Nautilus File Manager window, and move it to the second workspace on your desktop.

- Find the image you downloaded to use as your desktop background, and open it in any image viewer.

- Move back and forth between the workspace with Firefox on it and the one with the Nautilus file manager.

- Open a list of applications installed on your system, and select an image viewer to open from that list. Use as few clicks or keystrokes as possible.

- Change the view of the windows on your current workspace to smaller views of those windows you can step through. Select any window you like to make it your current window.

- From your desktop, using only the keyboard, launch a music player.

- Take a picture of your desktop, using only keystrokes.