Whereas the contrary bringeth bliss, And is a pattern of celestial peace. Whom should we match with Henry, being a king. . .

Many of JavaScript's features were borrowed from other languages. The syntax came from Java, functions came from Scheme, and prototypal inheritance came from Self. JavaScript's Regular Expression feature was borrowed from Perl.

A regular expression is the specification of the syntax of a

simple language. Regular expressions are used with methods to search, replace, and

extract information from strings. The methods that work with regular expressions are

regexp.exec, regexp.test, string.match, string.replace, string.search, and string.split. These

will all be described in Chapter 8. Regular expressions usually have a

significant performance advantage over equivalent string operations in

JavaScript.

Regular expressions came from the mathematical study of formal languages. Ken Thompson adapted Stephen Kleene's theoretical work on type-3 languages into a practical pattern matcher that could be embedded in tools such as text editors and programming languages.

The syntax of regular expressions in JavaScript conforms closely to the original formulations from Bell Labs, with some reinterpretation and extension adopted from Perl. The rules for writing regular expressions can be surprisingly complex because they interpret characters in some positions as operators, and in slightly different positions as literals. Worse than being hard to write, this makes regular expressions hard to read and dangerous to modify. It is necessary to have a fairly complete understanding of the full complexity of regular expressions to correctly read them. To mitigate this, I have simplified the rules a little. As presented here, regular expressions will be slightly less terse, but they will also be slightly easier to use correctly. And that is a good thing because regular expressions can be very difficult to maintain and debug.

Today's regular expressions are not strictly regular, but they can be very useful. Regular expressions tend to be extremely terse, even cryptic. They are easy to use in their simplest form, but they can quickly become bewildering. JavaScript's regular expressions are difficult to read in part because they do not allow comments or whitespace. All of the parts of a regular expression are pushed tightly together, making them almost indecipherable. This is a particular concern when they are used in security applications for scanning and validation. If you cannot read and understand a regular expression, how can you have confidence that it will work correctly for all inputs? Yet, despite their obvious drawbacks, regular expressions are widely used.

Here is an example. It is a regular expression that matches URLs. The pages of this book are not infinitely wide, so I broke it into two lines. In a JavaScript program, the regular expression must be on a single line. Whitespace is significant:

var parse_url = /^(?:([A-Za-z]+):)?(\/{0,3})([0-9.\-A-Za-z]+)

(?::(\d+))?(?:\/([^?#]*))?(?:\?([^#]*))?(?:#(.*))?$/;

var url = "http://www.ora.com:80/goodparts?q#fragment";Let's call parse_url's exec method. If it successfully matches the string that we pass it,

it will return an array containing pieces extracted from the url:

var url = "http://www.ora.com:80/goodparts?q#fragment";

var result = parse_url.exec(url);

var names = ['url', 'scheme', 'slash', 'host', 'port',

'path', 'query', 'hash'];

var blanks = ' ';

var i;

for (i = 0; i < names.length; i += 1) {

document.writeln(names[i] + ':' +

blanks.substring(names[i].length), result[i]);

}This produces:

url: http://www.ora.com:80/goodparts?q#fragment scheme: http slash: // host: www.ora.com port: 80 path: goodparts query: q hash: fragment

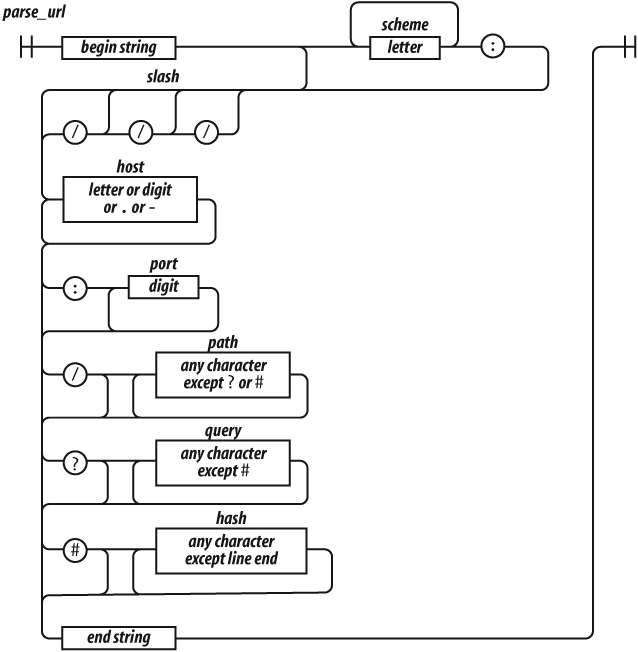

In Chapter 2, we used railroad diagrams to describe the JavaScript

language. We can also use them to describe the languages defined by regular

expressions. That may make it easier to see what a regular expression does. This is

a railroad diagram for parse_url.

Regular expressions cannot be broken into smaller pieces the way that functions

can, so the track representing parse_url is a

long one.

Let's factor parse_url into its parts to see

how it works.

^

The ^ character indicates the beginning of the

string. It is an anchor that prevents exec from

skipping over a non-URL-like prefix.

(?:([A-Za-z]+):)?

This factor matches a scheme name, but only if it is followed by a : (colon). The (?:

. . . ) indicates a noncapturing group. The

suffix ? indicates that the group is

optional.

It means repeat zero or one time. The ( . . . ) indicates a

capturing group. A capturing group copies the text it matches and places it in the

result array. Each capturing group is given a

number. This first capturing group is 1, so a copy of the text matched by this

capturing group will appear in result[1]. The [ .

. . ] indicates a character class. This character class, A-Za-z, contains 26 uppercase letters and 26 lowercase letters. The

hyphens indicate ranges, from A to Z. The suffix + indicates that the character class will be matched one or more

times. The group is followed by the : character,

which will be matched literally.

(\/{0,3})The next factor is capturing group 2. \/

indicates that a / (slash) character should be

matched. It is escaped with \ (backslash) so that

it is not misinterpreted as the end of the regular expression literal. The suffix

{0,3} indicates that the / will be matched 0 or 1 or 2 or 3 times.

([0-9.\-A-Za-z]+)

The next factor is capturing group 3. It will match a host name, which is made up

of one or more digits, letters, or . or -. The - was

escaped as \- to prevent it from being confused

with a range hyphen.

(?::(\d+))?

The next factor optionally matches a port number, which is a sequence of one or

more digits preceded by a :. \d represents a digit character. The series of one or

more digits will be capturing group 4.

(?:\/([^?#]*))?

We have another optional group. This one begins with a /. The character class [^?#]

begins with a ^, which indicates that the class

includes all characters except ? and #. The * indicates that the character class is matched zero

or more times.

Note that I am being sloppy here. The class of all characters except ? and # includes line-ending characters, control characters, and lots of other characters that really shouldn't be matched here. Most of the time this will do what we want, but there is a risk that some bad text could slip through. Sloppy regular expressions are a popular source of security exploits. It is a lot easier to write sloppy regular expressions than rigorous regular expressions.

(?:\?([^#]*))?

Next, we have an optional group that begins with a ?. It contains capturing group 6, which contains zero or more

characters that are not #.

(?:#(.*))?

We have a final optional group that begins with #. The . will match any character

except a line-ending character.

$

The $ represents the end of the string. It

assures us that there was no extra material after the end of the URL.

Those are the factors of the regular expression parse_url.[1]

It is possible to make regular expressions that are more complex than parse_url, but I wouldn't recommend it. Regular

expressions are best when they are short and simple. Only then can we have

confidence that they are working correctly and that they could be successfully

modified if necessary.

There is a very high degree of compatibility between JavaScript language processors. The part of the language that is least portable is the implementation of regular expressions. Regular expressions that are very complicated or convoluted are more likely to have portability problems. Nested regular expressions can also suffer horrible performance problems in some implementations. Simplicity is the best strategy.

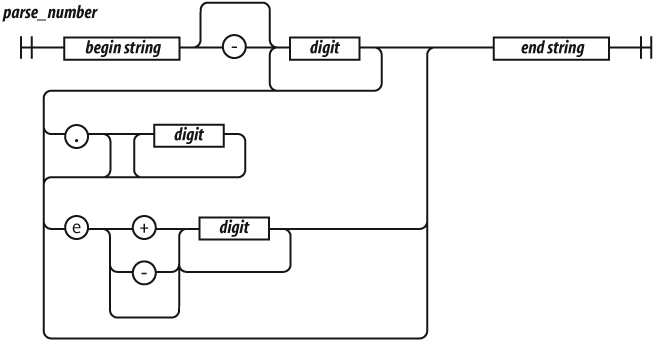

Let's look at another example: a regular expression that matches numbers. Numbers can have an integer part with an optional minus sign, an optional fractional part, and an optional exponent part.

var parse_number = /^-?\d+(?:\.\d*)?(?:e[+\-]?\d+)?$/i;

var test = function (num) {

document.writeln(parse_number.test(num));

};

test('1'); // true

test('number'); // false

test('98.6'); // true

test('132.21.86.100'); // false

test('123.45E-67'); // true

test('123.45D-67'); // falseparse_number successfully identified the

strings that conformed to our specification and those that did not, but for those

that did not, it gives us no information on why or where they failed the number

test.

Let's break down parse_number.

/^ $/i

We again use ^ and $ to anchor the regular expression. This causes all of the characters

in the text to be matched against the regular expression. If we had omitted the

anchors, the regular expression would tell us if a string contains a number. With

the anchors, it tells us if the string contains only a number. If we included just

the ^, it would match strings starting with a

number. If we included just the $, it would match

strings ending with a number.

The i flag causes case to be ignored when

matching letters. The only letter in our pattern is e. We want that e to also match

E. We could have written the e factor as [Ee] or

(?:E|e), but we didn't have to because we

used the i flag:

-?

The ? suffix on the minus sign indicates that

the minus sign is optional:

\d+

\d means the same as [0-9]. It matches a digit. The +

suffix causes it to match one or more digits:

(?:\.\d*)?

The (?: . . . )? indicates an optional

noncapturing group. It is usually better to use noncapturing groups instead of the

less ugly capturing groups because capturing has a performance penalty. The group

will match a decimal point followed by zero or more digits:

(?:e[+\-]?\d+)?

This is another optional noncapturing group. It matches e (or E), an optional sign, and

one or more digits.

[1] When you press them all together again, it is visually quite confusing:

/^(?:([A-Za-z]+):)?(\/{0,3})([0-9.\-A-Za-z]+)(?::(\d+))?(?:\/([^?#]*))?(?:\?([^#]*))?(?:#(.*))?$/