Chapter 18. The R (Rules) Configuration Command

Rules are like little if-then clauses,[245] existing inside rule sets, that test a pattern against an address and change the address if the two match. The process of converting one form of an address into another is called rewriting. Most rewriting requires a sequence of many rules because an individual rule is relatively limited in what it can do. This need for many rules, combined with the sendmail program’s need for succinct expressions, can make sequences of rules dauntingly cryptic.

In this chapter, we dissect the components of individual rules. In the next chapter. we will show how groups of rules can be combined to perform necessary tasks.

Why Rules?

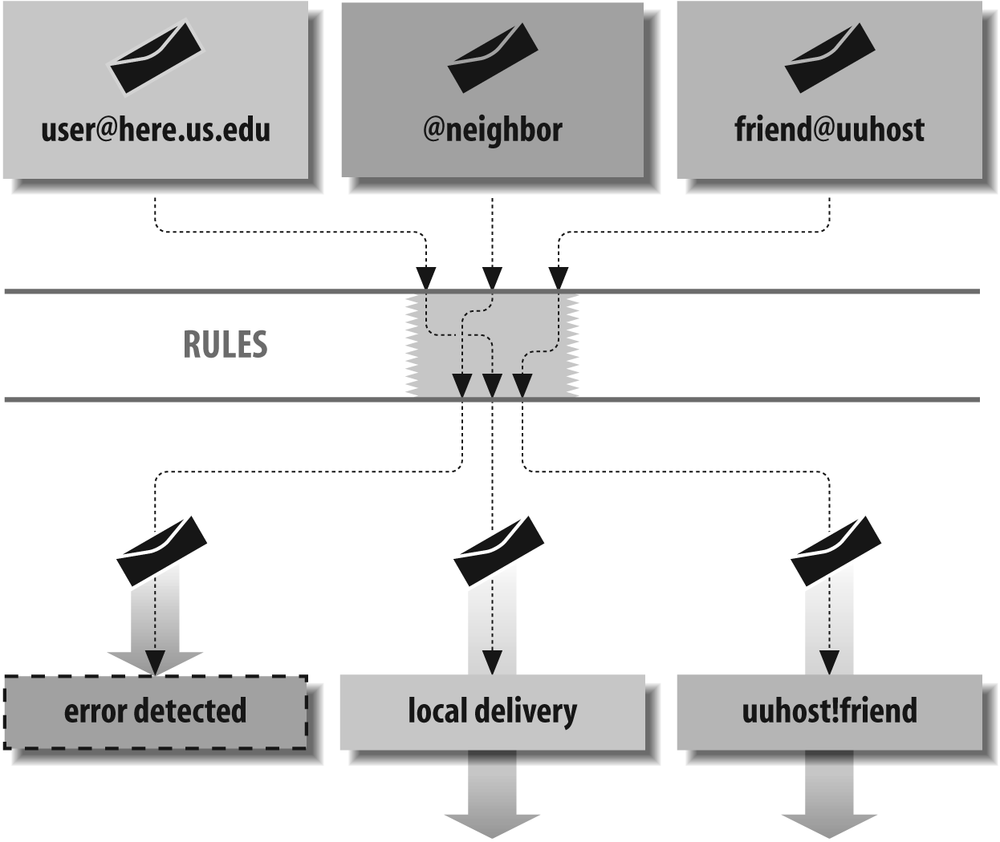

Rules in a sendmail.cf file are used to rewrite (modify) mail addresses, to detect errors in addressing, and to select mail delivery agents. Addresses need to be rewritten because they can be specified in many ways, yet are required to be in particular forms by delivery agents. To illustrate, consider Figure 18-1, and the address:

friend@uuhost

If the machine uuhost were

connected to yours over a dial-up line, mail might be sent

by UUCP, which requires addresses to be expressed in UUCP

form:

uuhost!friend

Rules can be used to change any address, such as friend@uuhost, into another address, such as uuhost!friend, for use by UUCP.

Rules can also detect and reject errors on the machine from which mail originated. This prevents errors from propagating over the network. Mail to an address without a username is one such error:

@neighbor

It is better to detect this kind of error as early as possible

instead of having the host neighbor reject it.

Rules can also select delivery agents. Delivery agents are the means used by sendmail to actually transmit or deliver mail messages. Rules examine the address of each envelope recipient and select the appropriate delivery agent. For example:

root@here.us.edu

Here, rules detect that here.us.edu is the name of the local

machine and then select the local delivery agent to perform final

delivery to the user root’s system

mailbox.

And lastly, rules can be used to make decisions about such things as rejecting spam, or deferring to a different queue.

The R Configuration Command

Rules are declared in the configuration file with the R configuration command.

Like all configuration commands, the R rule configuration

command must begin a line. The general form consists of an

R command

followed by three parts:

Rlhs rhs comment ↑ ↑ tabs tabs

The lhs stands for

lefthand side and is most

commonly expressed as LHS. The rhs stands for righthand

side and is expressed as RHS. The LHS and

RHS are mandatory. The third part (the comment) is optional. The

three parts must be separated from each other by one or more

tab characters (space characters will

not work).

Space characters between the R and the LHS are optional. If there is a

tab between the R and the

LHS, sendmail prints and logs the

following error:

configfile: line number: R line: null LHS

Space characters can be used inside any of the three parts: the LHS, RHS, or comment. They are often used in those parts to make rules clearer and easier to parse visually.

The tabs leading to the comment and the comment itself are

optional and can be omitted. If the RHS is absent,

sendmail prints the following

warning and ignores that R line:

invalid rewrite line "bad rule here" (tab expected)This error is printed when the RHS is absent, even if there are tabs following the LHS. (This warning is usually the result of tabs being converted to spaces when text is copied from one window to another in a windowing system using cut and paste.)

Macros in Rules

Each noncomment part of a rule is expanded as the configuration file is read.[246] Thus, any references to defined macros are replaced with the value that the macro has at that point in the configuration file. To illustrate, consider the following mini configuration file (which we will call test.cf):

V10 Stest DAvalue1 R $A $A.new DAvalue2 R $A $A.new

First, note that as of V8.10

sendmail, rules (the R lines) cannot exist

outside of rule sets (the S line). If you omit a rule set

declaration, the following error will be printed and

logged:

configfile: line number: missing valid ruleset for "bad rule here"

Second, note that beginning with V8.9,

sendmail will complain if the

configuration file lacks a correct version number

(the V line). Had

we omitted that line, sendmail

would have printed and logged the following

warning:

Warning: .cf file is out of date: sendmail 8.12.6 supports version 10, .cf file is version 0

The first D line

assigns the value value1 to the $A

sendmail macro. The second

D line replaces

the value assigned to $A in the first line with the new value

value2. Thus,

$A will have

the value value1

when the first R

line is expanded and value2 when the second is expanded.

Prove this to yourself by running

sendmail in -bt rule-testing mode to

test that file:

% echo =Stest | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cf

> =S0

R value1 value1 . new

R value2 value2 . newHere, we use the =S

command (Show Rules in a Rule Set with =S

on page 306) to show each rule after it has been

read and expanded.

Another property of macros is that an undefined macro

expands to an empty string. Consider this rewrite of

the previous test.cf file in

which we use a $B

macro that was never defined:

V10 Stest DAvalue1 R $A $A.$B DAvalue2 R $A $A.$B

Run sendmail again, in rule-testing mode, to see the result:

% echo =Stest | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cf

R value1 value1 .

R value2 value2 .Beginning with V8.7, sendmail macros can be either single-character or multicharacter. Both forms are expanded when the configuration file is read:

D{OURDOMAIN}us.edu

R ${OURDOMAIN} localhost.${OURDOMAIN}Multicharacter macros can be used in the LHS and in the RHS. When the configuration file is read, the previous example is expanded to look like this:

R us . edu localhost . us . edu

It is critical to remember that macros are expanded when the configuration file is read. If you forget, you might discover that your configuration file is not doing what you expect.

Rules Are Treated Like Addresses

After each side (LHS and RHS) is expanded, each is then normalized just as though it were an address. A check is made for any tabs that might have been introduced during expansion. If any are found, everything from the first tab to the end of the string is discarded.

Then, if the version of the configuration file you are running is less than 9 (that is, if the version of sendmail you are running is less than V8.10), RFC2822-style comments are removed. An RFC2822 comment is anything between and including an unquoted pair of parentheses:

DAroot@my.site (Operator) R $A tabRHS ↓ R root@my.site (Operator) tabRHS ← expanded ↓ R root@my.site tabRHS ← comment stripped prior to version 8 configs only

Finally, prior to V8.13 (see the next section, As of V8.13, rules no longer need to balance on page 653, for V8.13 and later behavior), a check was made for balanced quotation marks, and for right angle brackets balanced by left.[247] If any righthand character appeared without a corresponding lefthand character, sendmail printed one of the following errors (where configfile is the name of the configuration file that was being read, number shows the line number in that file, and expression is the part of the rule that was unbalanced) and attempted to make corrections:

configfile : line number: expression ...Unbalanced '"' configfile : line number: expression ...Unbalanced ''

Note that prior to V8.13, an unbalanced quotation mark was corrected by appending a second quotation mark, and an unbalanced angle bracket was corrected by removing it. Consider the following test.cf confirmation file:

V8 Stest R x RHS" R y RHS>

If you ran pre-V8.13 sendmail in rule-testing mode on this file, the following errors and rules would be printed:

% echo =Stest | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cf

test.cf: line 3: RHS"... Unbalanced '"'

test.cf: line 4: RHS>... Unbalanced '>'

R x RHS ""

R y RHSAlso note that prior to V8.7 sendmail, only an unbalanced righthand character was checked.[248] For V8.12 through V8.13 sendmail, unbalanced lefthand characters were also detected, and sendmail attempted to balance them. Consider the following rewrite of our test.cf file:

V9 Stest R x "RHS R y <RHS

Here, pre-V8.13 sendmail detected and fixed the unbalanced characters and issued warnings:

% echo =Stest | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cf

test.cf: line 3: "RHS... Unbalanced '"'

test.cf: line 4: <RHS... Unbalanced '<'

R x "RHS"

R y < RHS >If you saw one of these Unbalanced errors, correct the problem

at once. If you left the faulty rule in place,

sendmail would continue to

run but would likely produce erroneous mail delivery

and other odd problems.

Note that prior to configuration file version 9, configuration files had to have pairs of parentheses that also had to balance. That is, with version 8 and lower configuration files, the following rules:

V8 Stest R x (RHS R y RHS)

would produce the following errors:

% echo =Stest | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cf

test.cf: line 3: (RHS... Unbalanced '('

test.cf: line 3: R line: null RHS ← RFC2822 comment removed

test.cf: line 4: RHS)... Unbalanced ')'Line 3 (the second line of output in this example) shows that with configuration files prior to version 9, a parenthesized expression was interpreted as an RFC822 comment and removed.

As of V8.13, rules no longer need to balance

Prior to V8.13, special characters in rules were required to balance. If they didn’t, sendmail would issue a warning and try to make them balance:

SCheck_Subject R ----> test <---- $#discard $: discard

When a rule such as the preceding one was read by sendmail (while parsing its configuration file), sendmail would issue the following warning:

/path/cffile: line num: ----> test <----... Unbalanced '>' /path/cffile: line num: ----> test <----... Unbalanced '<'

Thereafter, sendmail would rewrite this rule internally to become:

R <----> test ---- $#discard $: discard

Clearly, such behavior made it difficult to write rules for parsing header values and for matching unusual sorts of addresses. Beginning with V8.13 sendmail, rules are no longer automatically balanced. Instead, unbalanced expressions in rules are accepted as is, no matter what.

The characters that were special but that no longer need to balance are shown in Table 18-1.

Note that if you have composed rules that anticipated and corrected this automatic balancing, you will need to rewrite those rules beginning with V8.13.

See also No balancing with $>+ on page 1133, which discusses this same change

as it applies to the $>+ header operator.

Backslashes in rules

Backslash characters are used in addresses to

protect certain special characters from

interpretation (Escape Character in the Header Field

on page 1124). For example, the address blue;jay would

ordinarily be interpreted as having three parts

(or tokens, which we’ll discuss soon). To prevent

sendmail from treating this

address as three parts and instead allow it to be

viewed as a single item, the special separating

nature of the ;

can be escaped by prefixing

it with a backslash:

blue\;jay

V8 sendmail handles backslashes differently than other versions have in the past. Instead of stripping a backslash and setting a high bit (as discussed later), it leaves backslashes in place:

blue\;jay becomes → blue\;jayThis causes the backslash to mask the special meaning of characters because sendmail always recognizes the backslash in that role.

V8 sendmail strips

backslashes only when a delivery agent has the

F=s flag (F=s on page 779) set, and then

only if they are not inside full quotation marks.

V8 sendmail also strips

backslashes when dequoting with the dequote dbtype (dequote on page 904).

Mail to \user is delivered to user on the local machine (bypassing further aliasing) with the backslash stripped. But for mail to \user@otherhost the backslash is preserved in both the envelope and the header.

Tokenizing Rules

The sendmail program views the text that makes up rules and addresses as being composed of individual tokens. Rules are tokenized—divided into individual parts—while the configuration file is being read and while they are being normalized. Addresses are tokenized at another time (as we’ll show later), but the process is the same for both.

The text our.domain, for example, is

composed of three tokens: our, a dot,

and domain. Tokens are separated by

special characters that are defined by the OperatorChars option

(OperatorChars on page 1062) or

the $o macro prior to

V8.7:

define(`confOPERATORS', `.:%@!^/[ ]+') ← m4 configuration O OperatorChars=.:%@!^/[ ]+ ← V8.7 and later Do.:%@!^=/[ ] ← prior to V8.7

When any of these separation characters are recognized in text, they are considered individual tokens. Any leftover text is then combined into the remaining tokens:

xxx@yyy;zzz becomes → xxx @ yyy;zzz@ is defined to be a token,

but ; is not. Therefore,

the text xxx@yyy;zzz is

divided into three tokens.

In addition to the characters in the OperatorChars option,

sendmail also defines 10

tokenizing characters internally:

( )<>,;"\r\n

This internal list, and the list defined by the OperatorChars option, are

combined into one master list that is used for all

tokenizing. The previous example, when divided by using this

master list, becomes five tokens instead of just

three:

xxx@yyy;zzz becomes → xxx @ yyy ; zzzIn rules, quotation marks can be used to override the meaning of tokenizing characters defined in the master list. For example:

"xxx@yyy";zzz becomes → "xxx@yyy" ; zzzHere, three tokens are produced because the @ appears inside quotation

marks. Note that the quotation marks are retained.

Because the configuration file is read sequentially from start

to finish, the OperatorChars option should be defined

before any rules are declared. But note, beginning with V8.7

sendmail, if you omit this

option you cause the separation characters to default

to:

. : % @ ! ^ / [ ]

Also note that beginning with V8.10, if you declare the

OperatorChars

option after any rule, the following error will be

produced:

Warning: OperatorChars is being redefined.

It should only be set before ruleset definitions.To prevent this error, declare the OperatorChars option in your

mc configuration file only with

the confOPERATORS

m4 macro (OperatorChars on page 1062):

define(`confOPERATORS', `.:%@!^/[ ]-')

Here, we have added a dash character (-) to the default list. Note that you

should not define your own operator characters unless you

first create and examine a configuration file with the

default settings. That way, you can be sure you always

augment the actual defaults you find, and avoid the risk

that you might miss new defaults in the future.

$-operators Are Tokens

As we progress into the details of rules, you will see

that certain characters become operators when

prefixed with a $

character. Operators cause

sendmail to perform actions,

such as looking for a match ($* is a wildcard

operator) or replacing tokens with others by

position ($1 is a

replacement operator).

For tokenizing purposes, operators always divide one token from another, just as the characters in the master list did. For example:

xxx$*zzz becomes → xxx $* zzzThe Space Character Is Special

The space character is special for two reasons. First, although the space character is not in the master list, it always separates one token from another:

xxx zzz becomes → xxx zzzSecond, although the space character separates tokens, it is not itself a token. That is, in this example the seven characters on the left (the fourth is the space in the middle) become two tokens of three letters each, not three tokens. Therefore, the space character can be used inside the LHS or RHS of rules for improved clarity but does not itself become a token or change the meaning of the rule.

Pasting Addresses Back Together

After an address has passed through all the rules (and has been modified by rewriting), the tokens that form it are pasted back together to form a single string. The pasting process is very straightforward in that it mirrors the tokenizing process:

xxx @ yyy becomes → xxx@yyyThe only exception to this straightforward pasting

process occurs when two adjoining tokens are both

simple text. Simple text is anything other than the

separation characters (defined by the OperatorChars option,

OperatorChars on page 1062, and

internally by sendmail) or the

operators (characters prefixed by a $ character). The

xxx and

yyy in the

preceding example are both simple text.

When two tokens of simple text are pasted together,

the character defined by the BlankSub option (BlankSub on page 980) is inserted

between them.[249] Usually, that option is defined as a

dot, so two tokens of simple text would have a dot

inserted between them when they are joined:

xxx yyy becomes → xxx.yyyNote that the improper use of a space character in the LHS or RHS of rules can lead to addresses that have a dot (or other character) inserted where one was not intended.

The Workspace

As was mentioned, rules exist to rewrite addresses. We won’t cover the reasons this rewriting needs to be done just yet, but we will concentrate on the general behavior of rewriting.

Before any rules are called to perform rewriting, a temporary buffer called the “workspace” is created. The address to be rewritten is then tokenized and placed into that workspace. The process of tokenizing addresses in the workspace is exactly the same as the tokenizing of rules that you saw before:

gw@wash.dc.gov becomes → gw @ wash . dc . govHere, the tokenizing characters defined by the OperatorChars option

(OperatorChars on page 1062) and

those defined internally by sendmail

caused the address to be broken into seven tokens. The

process of rewriting changes the tokens in the

workspace:

← workspace is "gw" "@" "wash" "." "dc" "." "gov" R lhs rhs R lhs rhs ← rules rewrite the workspace R lhs rhs ← workspace is "gw" "." "LOCAL"

Here, the workspace began with seven tokens. The three hypothetical rules recognized that this was a local address (in token form) and rewrote it so that it became three tokens.

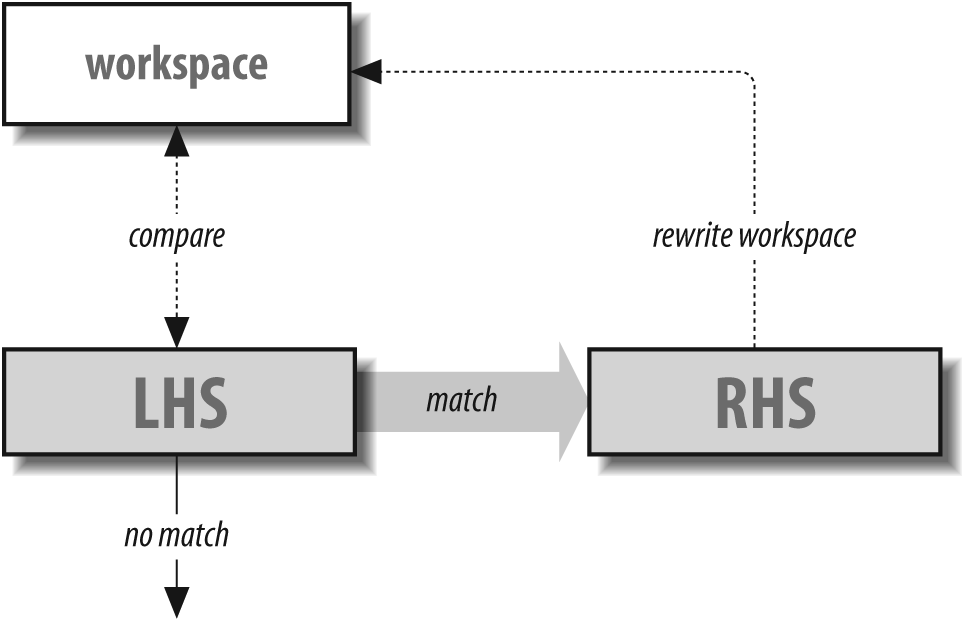

The Behavior of a Rule

Each individual rule (R

command) in the configuration file can be thought of as a

while-do statement. Recall that rules are composed of an LHS

(lefthand side) and an RHS (righthand side), separated from

each other by tabs. As long as (while) the LHS matches the

workspace, the workspace is rewritten (do) by the RHS (see

Figure 18-2).

Consider a rule in which we want the name tom in the workspace

changed into the name fred. One possible rule to do this might

look like this:

R tom fred

If the workspace contains the name tom, the LHS of this rule matches

exactly. As a consequence, the RHS is given the opportunity

to rewrite the workspace. It does so by placing the name

fred into that

workspace. The new workspace is once again compared to the

tom in the LHS,

but now there is no match because the workspace contains

fred. When the

workspace and the LHS do not match, the rule is skipped, and

the current contents of the workspace

are carried down to the next rule. Thus, in our example, the

name fred in the

workspace is carried down.

Clearly, there is little reason to worry about endless loops

in a rule when using names such as tom and fred. But the LHS and RHS can contain

pattern-matching and replacement operators, and those

operators can lead to loops. To

illustrate, consider the following example of a

test.cf file:

V10 Stest R fred fred

Clearly, the LHS will always match fred both before and after each rewrite.

Here’s what happens when you run the -bt rule-testing mode on

this file:

%/usr/sbin/sendmail -bt -Ctest.cfADDRESS TEST MODE (ruleset 3 NOT automatically invoked) Enter <ruleset> <address> >test fredtest input: fred Infinite loop in ruleset test, rule 1 test returns: fred >

V8 sendmail discovers the loop and breaks it for you. Earlier versions of sendmail would hang forever.

Note that you can avoid the chance of accidental loops by using special prefix operators on the RHS, as described in Rewrite Once Prefix: $: on page 662 and Rewrite-and-Return Prefix: $@ on page 664.

The LHS

The LHS of any rule is compared to the current contents of the workspace to determine whether the two match. Table 18-2 displays a variety of special operators offered by sendmail that make comparisons easier and more versatile.

|

Operator |

§ |

Description or use |

| [a] | ||

|

|

$* on page 681 |

Match zero or more tokens. |

|

|

$+ on page 679 |

Match one or more tokens. |

|

|

$- on page 679 |

Match exactly one token. |

|

|

$@ on page 673 |

Match exactly zero tokens (V8 only). |

|

|

Matching Any in a Class: $= on page 863 |

Match any tokens in a class.[a] |

|

|

Matching Any Token Not in a Class: $~ on page 864 |

Match any single token not in a class. |

|

|

$# on page 680 |

Match a literal |

|

|

$| on page 682 |

Match a literal |

|

|

Use Value As Is with $& on page 793 |

Delay macro expansion until runtime. |

[a] a Class matches either a single token or multiple tokens, depending on the version of sendmail (Access Classes in Rules). | ||

The first three operators in Table 18-2

are wildcard operators, which can be used to match arbitrary

sequences of tokens in the workspace. Consider the following

rule, which employs the $- operator (match any single

token):

R $- fred.local

Here, a match is found only if the workspace contains a single

token (such as tom). If the workspace

contains multiple tokens (such as

tom@host), the LHS does not

match. A match causes the workspace to be rewritten by the

RHS to become fred.local.

The rewritten workspace is then compared again to the

$-, but this time

there is no match because the workspace contains three

tokens (fred, a dot [.],

and local). Because there

is no match, the current workspace

(fred.local) is

carried down to the next rule (if there is one).

The $@ operator (introduced

in V8 sendmail) matches an empty

workspace. Merely omitting the LHS won’t work:

RtabRHS ← won't work R $@tabRHS ← will work

If you merely omit the LHS in a mistaken attempt to match an empty LHS, you will see the following error when sendmail starts up:

configfile: line number: R line: null LHS

Note that all comparisons of tokens in the LHS to tokens in

the workspace are done in a

case-insensitive manner. That is,

tom in the LHS

matches TOM, Tom, and even ToM in the

workspace.

Minimum Matching

When a pattern-matching operator can match multiple

tokens ($+ and

$+)

sendmail performs

minimum matching. For

example, consider a workspace of xxx.yyy.zzz and an LHS

of:

$+.$+

The first $+

matches only a single token (xxx) but the second

$+ matches

three (yyy, a

dot, and zzz).

This is because the first $+ matches the minimum number of tokens

that it can while still allowing the whole LHS to

match the workspace. Shortly, when we discuss the

RHS, we’ll show why this is important.

Backup and Retry

Multiple token-matching operators, such as $*, always try to match

the fewest number of tokens that they can. Such a

simple-minded approach could lead to problems in

matching (or not matching) classes in the LHS. For

example, consider the following five tokens in the

workspace:

A . B . C

given the following LHS rule:

R $+ . $=X $*

Because the $+

tries to match the minimum number of tokens, it

first matches only the A in the workspace. The $=X then tries to match

the B to the

class X. If this

match fails, sendmail backs up

and tries again.

The third time through, the $+ matches the A.B, and the $=X tries to match the C in the workspace. If

C is not in the

class X, the

entire LHS fails.

The ability of the sendmail program to back up and retry LHS matches eliminates much of the ambiguity from rule design. The multitoken matching operators try to match the minimum but match more if necessary for the whole LHS to match.

The RHS

The purpose of the RHS in a rule is to rewrite the workspace. To make this rewriting more versatile, sendmail offers several special RHS operators. The complete list is shown in Table 18-3.

|

RHS |

§ |

Description or use |

|

|

Copy by Position: $digit on page 661 |

Copy by position. |

|

|

Rewrite Once Prefix: $: on page 662 |

Rewrite once (when used as a prefix), or specify the user in a delivery agent “triple,” or specify the default value to return on a failed database-map lookup. |

|

|

Rewrite-and-Return Prefix: $@ on page 664 |

Rewrite and return (when used as a prefix), or specify the host in a delivery-agent “triple,” or specify an argument to pass in a database-map lookup or action. |

|

|

Rewrite Through a Rule Set: $>set on page 664 |

Rewrite through another rule set (such as a subroutine call that returns to the current position). |

|

|

Return a Selection: $# on page 667 |

Specify a delivery agent or choose an action, such as to reject or discard a recipient, sender, connection, or message. |

|

|

Canonicalize Hostname: $[ and $] on page 668 |

Canonicalize the hostname. |

|

|

Use $( and $) in Rules on page 892 |

Perform a lookup in an external database, file, or network service, or perform a change (such as dequoting), or store a value into a macro. |

|

|

Use Value As Is with $& on page 793 |

Delay conversion of a macro until runtime. |

Copy by Position: $digit

The $digit

operator in the RHS is used to copy tokens from the

LHS into the workspace. The

digit refers to

positions of LHS wildcard operators in the

LHS:

R $+ @ $* $2!$1

↑ ↑

$1 $2Here, the $1 in the

RHS indicates tokens matched by the first wildcard

operator in the LHS (in this case, the $+), and the $2 in the RHS indicates

tokens matched by the second wildcard operator in

the LHS (the $*).

In this example, if the workspace contains A@B.C, it will be

rewritten by the RHS as follows (note that the order

is defined by the RHS):

$* matches B.C so $2 copies it to workspace ! explicitly added to the workspace $+ matches A so $1 adds it to workspace

The $digit

copies all the tokens matched by its corresponding

wildcard operator. For the $+ wildcard operator, only a single

token (A) is

matched and copied with $1. The ! is copied as is. For the $* wildcard operator,

three tokens are matched (B.C), so $2 copies all three. Thus, this rule

rewrites A@B.C

into B.C!A.

Not all LHS operators need to be

referenced with a $digit in

the RHS. Consider the following:

R $* < $* > $* <$2>

Here, only the middle LHS operator (the second one) is

required to rewrite the workspace. So, only the

$2 is needed in

the RHS ($1 and

$3 are not

needed and are not present in the RHS).

Although macros appear to be operators in the LHS,

they are not. Recall that macros are expanded when

the configuration file is read (Macros in Rules on page 650). As a

consequence, although they appear as $letter in

the configuration file, they are converted to tokens

when that configuration file is read. For

example:

DAxxx R $A @ $* $1

Here, the macro A

is defined to have the value xxx. To the unwary, the

$1

appears to indicate the

$A. But when

the configuration file is read, the previous rule is

expanded into:

R xxx @ $* $1

Clearly, the $1

refers to the $*

(because $

digit references only

operators and $A

is a macro, not an operator). The

sendmail program is unable to

detect errors of this sort. If the $1 were instead $2 (in a mistaken

attempt to reference the $*), sendmail

prints the following error and skips that

rule:

ruleset replacement number out of boundsV8 sendmail catches these errors when the configuration file is read. Earlier versions caught this error only when the rule was actually used.

The digit of the $digit must

be in the range one through nine. A $0 is meaningless and

causes sendmail to print the

previous error message and to skip that rule. Extra

digits are considered tokens rather than extensions

of the $digit. That

is, $11 is the

RHS operator $1

and the token 1,

not a reference to the

11th LHS

operator.

Rewrite Once Prefix: $:

Ordinarily, the RHS rewrites the workspace as long as the workspace continues to match the LHS. This looping behavior can be useful. Consider the need to strip extra trailing dots off an address in the workspace:

R $* .. $1.

Here, the $*

matches any address that has two or more trailing

dots. The $1. in

the RHS then strips one of those two trailing dots

when rewriting the workspace. For example:

xxx . . . . . becomes → xxx . . . . xxx . . . . becomes → xxx . . . xxx . . becomes → xxx . . xxx . . becomes → xxx . xxx . ← match fails

Although this looping behavior of rules can be handy, for most rules it can be dangerous. Consider the following example:

R $* <$1>

The intention of this rule is to cause whatever is in

the workspace to become surrounded with angle

brackets. But after the workspace is rewritten, the

LHS again checks for a match; and because the

$* matches

anything, the match succeeds, the RHS rewrites the

workspace again, and again the LHS checks for a

match:

xxx becomes → < xxx > < xxx > becomes → < < xxx > > < < xxx > > becomes → < < < xxx > > > ↓ and so on, until ... ↓ sendmail prints: rewrite: expansion too long

In this case,sendmail catches the problem because the workspace has become too large. It prints the preceding error message and skips that and all further rules in the rule set. If you are running sendmail in test mode, this fatal error would also be printed:

= = Ruleset 0 (0) status 65

Unfortunately, not all such endless looping produces a visible error message. Consider the following example:

R $* $1

Here is an LHS that matches anything and an RHS that rewrites the workspace in such a way that the workspace never changes. For older versions, this causes sendmail to appear to hang (as it processes the same rule over and over and over). Newer versions of sendmail will catch such endless looping and will print and log the following error:

Infinite loop in ruleset ruleset_name, rule rule_number

In this instance, the original workspace is returned.

It is not always desirable (or even possible) to write

“loop-proof” rules. To prevent looping,

sendmail offers the $: RHS prefix. By

starting the RHS of a rule with the $: operator, you are

telling sendmail to rewrite the

workspace only once, at most:

R $* $: <$1>

Again the rule causes the contents of the workspace to

be surrounded by a pair of angle brackets. But here

the $: prefix

prevents the LHS from checking for another match

after the rewrite.

Note that the $:

prefix must begin the RHS to have any effect. If it

instead appears inside the RHS, its special meaning

is lost:

foo rewritten by $: $1 becomes → foo foo rewritten by $1 $: becomes → foo $:

Rewrite-and-Return Prefix: $@

The flow of rules is such that each and every rule in a series of rules (a rule set) is given a chance to match the workspace:

R xxx yyy R yyy zzz

The first rule matches xxx in the workspace and rewrites the

workspace to contain yyy. The first rule then tries to match

the workspace again but, of course, fails. The

second rule then tries to match the workspace.

Because the workspace contains yyy, a match is found,

and the RHS rewrites the workspace to be zzz.

There will often be times when one rule in a series

performs the appropriate rewrite and no subsequent

rules need to be called. In the earlier example,

suppose xxx

should only become yyy and that the second rule should not

be called. To solve problems such as this,

sendmail offers the $@ prefix for use in the

RHS.

The $@ prefix tells

sendmail that the current

rule is the last one that should be used in the

current rule set. If the LHS of the current rule

matches, any rules that follow (in the current rule

set) are ignored:

R xxx $@ yyy R yyy zzz

If the workspace contains anything other than xxx, the first rule does

not match, and the second rule is called. But if the

workspace contains xxx, the first rule matches and

rewrites the workspace. The $@ prefix for the RHS of that rule

prevents the second rule (and any subsequent rules

in that rule set) from being called.

Note that the $@

also prevents looping. The $@ tells sendmail

to skip further rules and to

rewrite only once. The difference between $@ and $: is that both rewrite

only once, but $@

doesn’t proceed to the next

rule, whereas $:

does.

The $@ operator

must be used as a prefix because it has special

meaning only when it begins the RHS of a rule. If it

appears anywhere else inside the RHS it loses its

special meaning:

foo rewritten by $@ $1 becomes → foo foo rewritten by $1 $@ becomes → foo $@

Rewrite Through a Rule Set: $>set

Rules are organized in sets that can be thought of as subroutines. Occasionally, a series of rules can be common to two or more rule sets. To make the configuration file more compact and somewhat clearer, such common series of rules can be made into separate subroutines.

The RHS $>set

operator tells sendmail to

perform additional rewriting using a secondary set

of rules. The set is the

rule set name or number of that secondary set. If

set is the name or

number of a nonexistent rule set, the effect is the

same as if the subroutine rules were never called

(the workspace is unchanged).

If the set is numeric and

is greater than the maximum number of allowable rule

sets, sendmail prints the

following error and skips that rule:

bad ruleset bad_number (maximum max)

If the set is a name and

the rule set name is undeclared,

sendmail prints the following

error and skips that rule:

Unknown ruleset bad_nameNeither of these errors is caught when the configuration file is read. They are caught only when mail is sent because a rule set name can be a macro:

$> $&{SET}The $& prefix

prevents the macro named {SET} from being expanded when the

configuration file is read. Therefore, the name or

number of the rule set cannot be known until mail is

sent.

The process of calling another set of rules proceeds in five stages:

- First

As usual, if the LHS matches the workspace, the RHS gets to rewrite the workspace.

- Second

The RHS ignores the

$>setpart and rewrites the rest as usual.- Third

The part of the rewritten workspace following the

$>setis then given to the set of rules specified by set. They either rewrite the workspace or do not.- Fourth

The portion of the original RHS from the

$>setto the end is replaced with the subroutine’s rewriting, as though it had performed the subroutine’s rewriting itself.- Fifth

The LHS gets a crack at the new workspace as usual unless it is prevented by a

$: or$@prefix in the RHS.

For example, consider the following two sets of rules:

# first set

S21

R $*.. $:$>22 $1. strip extra trailing dots

...etc.

# second set

S22

R $*.. $1. strip trailing dotsHere, the first set of rules contains, among other things, a single rule that removes extra dots from the end of an address. But because other rule sets might also need extra dots stripped, a subroutine (the second set of rules) is created to perform that task.

Note that the first rule strips one trailing dot from

the workspace and then calls rule set 22 (the

$>22),

which then strips any additional dots. The

workspace, as rewritten by rule set 22, becomes the

workspace yielded by the RHS in the first rule. The

$: prevents the

LHS of the first rule from looking for a match a

second time.

Prior to V8.8 sendmail, the

subroutine call must begin the RHS (immediately

follow any $@ or

$: prefix, if

any), and only a single subroutine can be called.

That is, the following causes rule set 22 to be

called but does not call 23:

$>22 xxx $>23 yyy

Instead of calling rule set 23, the $> operator and the

23 are copied

as is into the workspace, and that workspace is

passed to rule set 22:

xxx $> 23 yyy ← passed to rule set 22Beginning with V8.8[250] sendmail, subroutine calls can appear anywhere inside the RHS, and there can be multiple subroutine calls. Consider the same RHS as shown earlier:

$>22 xxx $>23 yyy

Beginning with V8.8 sendmail,

rule set 23 is called first and is given the

workspace yyy to

rewrite. The workspace, as rewritten by rule set 23,

is added to the end of the xxx, and the combined result is passed

to rule set 22.

Under V8.8 sendmail, subroutine rule set calls are performed from right to left. The result (rewritten workspace) of each call is appended to the RHS text to the left.

You should beware of one problem with all versions of

sendmail. When ordinary text

immediately follows the number of the rule set, that

text is likely to be ignored. This can be witnessed

by using the -d21.3 debugging switch.

Consider the following RHS:

$>3uucp.$1

Because sendmail parses the

3 and the

uucp as a

single token, the subroutine call succeeds, but the

uucp is lost.

The -d21.3 switch

illustrates this problem:

-----callsubr 3uucp (3) ← sees this -----callsubr 3 (3) ← but should have seen this

The 3uucp is

interpreted as the number 3, so it is accepted as a

valid number despite the fact that uucp was attached.

Because the uucp

is a part of the number, it is not available for

comparison to the workspace and so is lost. The

correct way to write the previous RHS is:

$>3 uucp.$1

Note that the space between the 3 and the uucp causes them to be

viewed as two separate tokens.

This problem can also arise with macros. Consider the following:

$>3$M

Here, the $M is

expanded when the configuration file is parsed. If

the expanded value lacks a leading space, that value

(or the first token in it) is lost.

Note that operators that follow a rule set number are correctly recognized:

$>3$[$1$]

Here, the 3 is

immediately followed by the $[ operator. Because operators are

token separators, the call to rule set 3 will be

correctly interpreted as:

-----callsubr 3 (3) ← goodBut as a general rule, and just to be safe, the number of a subroutine call should always be followed by a space.[251]

Return a Selection: $#

The $# operator in

the RHS is copied as is into the workspace and

functions as a flag advising

sendmail that an action has

been selected. The $# must be the first token copied into

the rewritten workspace for it to have this special

meaning. If it occupies any other position in the

workspace, it loses its special meaning:

$# local ← selects delivery agent in the parse rule set 0 $# OK ← accepts a message in the Local_check_mail rule set xxx $# local ← no special meaning

When it is used in the parse rule set 0 (The parse Rule Set 0 on page 696) and

localaddr rule

set 5 (The localaddr Rule Set 5 on

page 700) (and occupies the first position in the

rewritten workspace), the $# operator tells

sendmail that the second

token in the workspace is the name of a delivery

agent (here, local). When used in the check_ rule sets (Check Headers with Rule Sets on page

265 and The Local_check_ Rule Sets on page 252) subsequent tokens in the workspace

(here, OK) say

how a message should be handled.

Note that the $#

operator can be prefixed with a $@ or a $: without losing its

special meaning because those prefix operators are

not copied to the workspace:

$@ $# local rewritten as → $# localHowever, those prefix operators are not necessary

because the $#

acts just like a $@ prefix. It prevents the LHS from

attempting to match again after the RHS rewrite, and

it causes any following rules (in that rule set) to

be skipped. When used in non-prefix roles in the

parse rule set

0 and localaddr

rule set 5, $@

and $: also act

like flags, conveying host and address information

to sendmail (The parse Rule Set 0 on page

696).

Canonicalize Hostname: $[ and $]

Tokens that appear between a $[ and $] pair of operators in the RHS are

considered to be the name of a host. That hostname

is looked up by using DNS[252] and replaced with the full canonical

form of that name. If found, it is then copied to

the workspace, and the $[ and $] are discarded.

For example, consider a rule that looks for a hostname in angle brackets and (if found) rewrites it in canonical form:

R < $* > $@ < $[ $1 $] > canonicalize hostname

Such canonicalization is useful at sites where users

frequently send mail to machines using the short

version of a machine’s name. The $[ tells

sendmail to view all the

tokens that follow (up to the $]) as a single

hostname.

If the name cannot be canonicalized (perhaps because there is no such host), the name is copied as is into the workspace. For configuration files lower than 2, no indication is given that it could not be canonicalized (more about this soon).

Note that if the $[

is omitted and the $] is included, the $] loses its special

meaning and is copied as is into the

workspace.

The hostname between the $[ and $] can also be an IP address. By

surrounding the hostname with square brackets

([ and ]), you are telling

sendmail that it is really an

IP address:

wash.dc.gov ← a hostname [123.45.67.8] ← an IPv4 address [IPv6:2002:c0a8:51d2::23f4] ← an IPv6 address

When the IP address between the square brackets

corresponds to a known host, the address and the

square brackets are replaced with that host’s

canonical name. Note that when handling IPv6

addresses, the IPv6: prefix must be present. After the

successful lookup of a known host, the entire

expression between $[ and $] will be replaced with the new

information.

If the version of the configuration file is 2 or greater (as set

with the V

configuration command, The V Configuration Command on page

580), a successful canonicalization has a dot

appended to the result:

myhost becomes → myhost . domain . ← success nohost becomes → nohost ← failure

Note that a trailing dot is not legal in an address specification, so subsequent rules (such as rule set 4) must remove these added trailing dots.[253]

Also, the K

configuration command (The K Configuration Command on page

882) can be used to redefine (or eliminate) the dot

as the added character. For example:

Khost host -a.found

This causes sendmail to add the

text .found to a

successfully canonicalized hostname instead of the

dot.

One difference between V8

sendmail and other versions

is the way it looks up names from between the

$[ and $] operators. The rules

for V8 sendmail are as

follows:

- First

If the name contains at least one dot (.) anywhere within it, it is looked up as is; for example, host.com.

- Second

If that fails, it appends the default domain to the name (as defined in /etc/resolv.conf) and tries to look up the result; for example, host.com.foo.edu.

- Third

If that fails, each entry in the domain search path (as defined in /etc/resolv.conf) is appended to the original host; for example, host.com.edu.

- Fourth

If the original name did not have a dot in it, it is looked up as is; for example, host.

This approach allows names such as host.com to first match an actual site, such as sendmail.com (if that was intended), instead of wrongly matching a host in a local department of your school. This is particularly important if you have wildcard MX records for your site.

An example of canonicalization

The following three-line configuration file can be used to observe how sendmail canonicalizes hostnames:

V10 SCanon R $* $@ $[ $1 $]

If this file were called test.cf, sendmail could be run in rule-testing mode with a command such as the following:

% /usr/sbin/sendmail -Ctest.cf -btThereafter, hostname canonicalization can be

observed by specifying the Canon rule set and a

hostname. One such run of tests might appear as

follows:

ADDRESS TEST MODE (ruleset 3 NOT automatically invoked) Enter <ruleset> <address> >Canon washcanon input: wash canon returns: wash . dc. gov . >Canon nohostcanon input: nohost canon returns: nohost >

Note that the known host named wash is rewritten in

canonicalized form (with a dot appended because

the version of this mini configuration file, the

V10, is greater

than 2). The unknown host named nohost is unchanged and

has no dot appended.

Default in canonicalization: $:

IDA and V8 sendmail both

offer an alternative to leaving the hostname

unchanged when canonicalization fails with

$[ and $]. A default can be

used instead of the failed hostname by prefixing

that default with a $: operator:

$[ host $: default $]The $:

default must follow the

host (or

square-brace-enclosed address) and precede the

$]. To

illustrate its use, consider the following

rule:

R $* $: $[ $1 $: $1.notfound $]

If the hostname $1 can be canonicalized, the workspace

becomes that canonicalized name. If it cannot, the

workspace becomes the original hostname with a

.notfound

appended to it. If the

default part of the

$:default is

omitted, a failed canonicalization is rewritten as

zero tokens.

Because the $[ and $] operators are implemented using the

host dbtype

($[ and $]: A Special Case on page 895), you can modify the behavior of

that dbtype by adding a -T to it:

Khost host -T.tmp

Thereafter, whenever $[ and $] find a temporary lookup failure, the

suffix .tmp is

returned, and .notfound, in this example, is returned

only if the host truly does not exist.

Other Operators

Many other operators (depending on your version of sendmail) can also be used in rules. Because of their individual complexity, all of the following are detailed in other chapters. We outline them here, however, for completeness.

- Class macros

Class macros are described in Matching Any in a Class: $= on page 863 and Matching Any Token Not in a Class: $~ on page 864. Class macros can appear only in the LHS. They begin with the prefix

$=to match a token in the workspace to one of many items in a class. The alternative prefix$˜causes a single token in the workspace to match if it does not appear in the list of items that are in the class.- Conditionals

The conditional macro operator

$?is rarely used in rules (Macro Conditionals: $?, $|, and $. on page 794). When it is used in rules, the result is often not what was intended. Its else part, the$|conditional operator, is used by the various rule sets (The check_compat Rule Set on page 259) to separate two differing pieces of information in the workspace.- Database maps

The database-map operators,

$(and$), are used to look up tokens in various types of database files, plain files, and network services. They also provide access to internal services, such as dequoting or storing a value in the macro (see Chapter 23 on page 878).

Pitfalls

Any text following a rule set number in a

$>expression in the RHS sho uld be separated from the expression with a space. If the space is absent and the text is something other th an a separating character or an operator, the text is ignored. For example, in$>22xxx, thexxxis ignored.Because rules are processed like addresses when the configuration file is read, they can silently change from what was intended if they are parenthesized or if other nonaddress components are used.

Copying rules between screen windows can cause tabs to invisibly become spaces, leading to rule failure.

A lone

$*in the LHS is especially dangerous. It can lead to endless rule looping and cause all rules that follow it to be ignored (remember the$: and$@prefixes in the RHS).Failure to test new rules can bring a site to its knees. A flood of bounced mail messages can run up the load on a machine and possibly even require a reboot. Always test every new rule both with

-bt(testing) mode (Batch Rule-Set Testing on page 319) and selected-d(debugging) switches (Table 15-3 on page 536).Overloading of operator meanings can confuse the new user, or even the seasoned user when a new release of sendmail appears. Under older versions of sendmail, the

$: operator, for example, could either be a prefix used to suppress recursion or was a nonprefix used to specify the user in a delivery agent “triple.” In a later release, it also became the way to specify the default value to return on a failed database-map lookup.

Rule Operator Reference

In this section, we describe each rule operator. Note that we

exclude operators that are not germane to rules (such as

$?, Macro Conditionals: $?, $|, and $.

on page 794) and list only those that can be used in rules.

Because all rule operators are symbolic, we cannot list them

in alphabetical order, so instead we list them in the

alphabetical order of pronunciation. That is, for example,

$@ (pronounced

dollar-at) comes before $: (pronounced dollar-colon).

To avoid confusion based on different ways of pronouncing symbols, we list all the operators in Table 18-4 so that you can easily find them.

|

Operator |

§ |

RHS or LHS |

Description or use |

|

|

$& on page 673 |

LHS and RHS |

Delay macro expansion until runtime. |

|

|

$@ on page 673 |

LHS |

Match exactly zero tokens (V8 only). |

|

|

$@ on page 674 |

RHS |

Rewrite once and return. |

|

|

$@ on page 674 |

RHS |

Specify host in delivery agent “triple”. |

|

|

$@ on page 674 |

RHS |

Specify DSN status in error agent “triple”. |

|

|

$@ on page 675 |

RHS |

Specify a database-map argument. |

|

|

$: on page 675 |

RHS |

Rewrite once and continue. |

|

|

$: on page 676 |

RHS |

Specify address in delivery agent “triple”. |

|

|

$: on page 676 |

RHS |

Specify message in error or discard agent “triple”. |

|

|

$: on page 676 |

RHS |

Specify a default database-map value. |

|

|

$digit on page 677 |

RHS |

Copy by position. |

|

|

$= on page 677 |

LHS |

Match any token in a class. |

|

|

$> on page 677 |

RHS |

Rewrite through another rule set (subroutine call). |

|

|

$[ $] on page 678 |

RHS |

Canonicalize the hostname. |

|

|

$( $) on page 678 |

RHS |

Perform a database-map lookup or action. |

|

|

$- on page 679 |

LHS |

Match exactly one token. |

|

|

$+ on page 679 |

LHS |

Match one or more tokens. |

|

|

$# on page 680 |

LHS |

Match a literal |

|

|

$# on page 680 |

RHS |

Specify a delivery agent. |

|

|

$# on page 681 |

RHS |

Specify return for a policy-checking rule set. |

|

|

$* on page 681 |

Match zero or more tokens. | |

|

|

$~ on page 682 |

LHS |

Match any single token not in a specified class. |

|

|

$| on page 682 |

LHS and RHS |

Match or return a literal |

$&

Delay macro expansion until runtime LHS and RHS operator

Normally, sendmail macros are

expanded (replaced with their values) when the

configuration file is read. For those situations

when a sendmail macro should

not be expanded, but rather should be used in rules

as is, V8 sendmail offers the

$& prefix.

For example, consider the following RHS of a

rule:

R... $w.$&M

Normally, when sendmail

encounters this RHS in the configuration file, it

will recursively expand $w into its final text value (where

that text value is your hostname, such as

wash.dc.gov). But because the

M

sendmail macro is prefixed

(here, with $&), it is not expanded until the

rule is processed.

The $& operator

can be used in either the LHS or the RHS of a rule.

The $&

operator is described in full in Use Value As Is with $& on page

793.

$@

Match exactly zero tokens (V8 only) LHS operator

There will be times when you have to match an empty

workspace. The $@

operator, when used in the LHS, does exactly that.

To illustrate, consider the following rule:

R $@ $#error $@ nouser $: "553 User address required"

Here, the idea is to detect an empty address (the

LHS), and to reject the message with an error (the

RHS) if such an address is found. This LHS matches a

workspace (an address) that contains zero

information (zero tokens). Here, then, the $@ operator matches an

empty workspace.

The $@ operator was

introduced because it is illegal to literally put

nothing on the LHS. The following rule (here we show

tabs with tab) won’t

work:

Rtab$#error $@ nouser $: "553 User address required"If you try to match an empty workspace such as this, you will get the following error:

configfile: line number: R line: null LHS

Note that the $@

operator matches zero tokens only when used on the

LHS. When used on the RHS $@ has a totally different meaning.

Note, too, that the $@ operator on the LHS cannot be

referenced by a $

digit operator on the

RHS.

$@

Rewrite once and return RHS prefix

The $@ operator,

when used to prefix the RHS, tells

sendmail that the current

rule is the last one that should be used in the

current rule set. If the LHS of the current rule

matches, any rules that follow (in the current rule

set) are ignored.

This $@ prefix also

prevents the current rule from calling itself

recursively. To illustrate, consider the following

rule:

R $* . $* $@ $1

The idea here is to strip the domain part of a

hostname, and to return just the host part. That is,

if the workspace contains

wash.dc.gov, this rule will

return wash. The $@ prefix to the RHS

tells sendmail to return the

rewritten workspace without processing any

additional rules in the current rule set, and to

allow the LHS to match only once.

Note that the $@

prefix can prefix only the RHS. This operator is

described further in Rewrite-and-Return Prefix: $@

on page 664 of this chapter.

$@

Specify host in delivery agent “triple” RHS delivery agent operator

The parse rule set

0 selects a delivery agent that can handle the

address specified in the workspace. The form for

selecting a delivery agent looks like this:

LHS... $#delivery_agent $@ host $: addressThree pieces of information are necessary to select a

delivery agent. The $# specifies the name of the delivery

agent. The $@

specifies the host part of the address (for

gw@wash.dc.gov, the host part would

be wash.dc.gov), and the

$: specifies

the user part of the address (the

gw) for local delivery and

the whole address (the

gw@wash.dc.gov) for SMTP

delivery.

The use of $@ to

specify the host can follow only the $# prefix part of the

RHS. Note that $@

has a different use when the delivery agent is named

error (see

$@ on page

674).

The use of $@ to

specify the host part of a delivery agent triple is

described in detail in The parse Rule Set 0 on page 696. See

also The use of $h in A=TCP on

page 739 for how to use this $@ to specify the port

to which sendmail should

connect.

$@

Specify DSN status in error-agent “triple” RHS delivery agent operator

Beginning with V8.7, the RHS of a rule to select an

error delivery

agent can look like this:

R... $#error $@ dsn $: text of error message here

The text following the $: is the actual error message text

that will be included in bounced mail or sent back

to a connecting SMTP host. The numbers following the

$@ specify the

DSN error to be returned. For example:

R$* < @ spam.host > $* $#error $@ 5.7.1 $: 550 You are a spammer, go away

Here, the number following the $@ contains a dot, so it

is interpreted as a DSN status expression. The

.7. in the

number causes sendmail to set

its exit value to EX_DATAERR. The 5.7.1 itself is defined

in RFC1893 as meaning “Permanent failure, delivery

not authorized, message refused.” Note that if the

number following the $@ does not contain a dot,

sendmail sets its

exit(2) value to that

number.

The use of $@ to

specify the DNS return value for the error delivery agent is

described in detail in error on

page 720.

$@

Specify a database-map argument RHS database operator

When looking up information or performing actions with

the $( and

$) operators,

it is sometimes necessary to provide positional

substitution arguments. To illustrate, consider an

entry such as this in a hypothetical database source

file:

hostA %0!%1@%2

With such an entry in place, and having built the database, the following rule could be used to perform a lookup:

R$- @ $-.uucp $: $(uucp $2 $@ $1 $@ mailhost $: $1.$2.uucp $)

Here, if the workspace contains the address joe@hostA.uucp, the LHS matches, causing it to be rewritten as hostA!joe@mailhost.

See Specify Numbered Substitution with $@ on page 894 for a full description of how

$@ is used in

this way.

$:

Rewrite once and continue RHS prefix

Ordinarily, the RHS of a rule continues to rewrite the workspace for as long as the workspace continues to match the LHS. This looping behavior can be useful when intended, but can be a disaster if unintended. But consider what could happen, under older versions of sendmail, if you wrote a rule such as the following, which seeks to match a domain address with at least one first dot:

R $+ . $* $1.OK

An address such as wash.dc.gov

will match the LHS and will be rewritten by the RHS

into wash.OK. But because rules

continue to match until they fail, the new address,

wash.OK, will be matched by

the LHS again, and again will be rewritten to be

wash.OK. As you can see, this

rule sets up an infinite loop.[254] To prevent such infinite looping on this

rule, you should prefix the RHS with the $: operator:

R $+ . $* $: $1.OKThe $: prefix tells

sendmail to rewrite the

workspace only once. With the $: prefix added to our

example, the domain address

wash.dc.gov would be

rewritten to wash.OK exactly

once. Progress would then proceed to the next

following rule (if there is one).

The $: prefix is

described in full in Rewrite Once Prefix: $:

on page 662.

$:

Specify address in delivery agent “triple” RHS delivery agent operator

The parse rule set

(formerly rule set 0) selects a delivery agent that

can handle the address specified in the workspace.

The form for selecting a delivery agent looks like

this:

LHS... $#delivery_agent $@ host $: addressThree pieces of information are necessary to select a

delivery agent.[255] The $# specifies the name of the delivery

agent. The $@

specifies the host part of the address (for

gw@wash.dc.gov, the host part would

be wash.dc.gov), and the

$: specifies

the address part (the gw for

local delivery, or gw@wash.dc.gov for

SMTP delivery).

The use of $: to

specify the address can follow only the $# prefix part of the

RHS. Note that $:

has a different use when the delivery agent is named

error or

discard (see

$: on page

676).

The use of $: to

specify the address part of a delivery agent triple

is described in detail in The parse Rule Set 0 on page

696.

$:

Specify message in error or discard agent “triple” RHS delivery agent operator

Beginning with V8.7, the RHS of a rule used to select

an error or

discard

delivery agent can look like this:

R... $#error $@ dsn $: text of error message here R... $#discard $: discard

For the error

delivery agent, the text following the $: is the actual error

message text that will be included in bounced mail

or sent back to a connecting SMTP host. For the

discard

delivery agent, the text following the $: is generally the

literal word discard.[256]

Use of $: to

specify the error

delivery agent’s error message is described in

detail in error on page 720. Use

of $: to specify

the discard

delivery agent is described in discard on page 719.

$:

Specify a default database-map value RHS database operator

When looking up information with the $( and $) operators it is

sometimes desirable to provide a default return

value, should the lookup fail. Default values are

specified with the $: operator, which fits between the

$( and $) operators like

this:

LHS.... $( name key $: default $)Here, name is the symbolic

name you associated with a dbtype (The type on

page 882) using the K configuration command. The

key is the value being

looked up, and default is

the value to be placed in the workspace if the

lookup fails.

To illustrate, consider the following rule:

R $+ < @ $* . fax > $: $1 < @ $(faxdb $2 $: faxhost $) >

Here, any address that ends in .fax (such as

bob@here.fax) has the host part

($* or the

here) looked up in the

faxdb database (the $2 is the key). If that

host is not found with the lookup, the workspace is

changed to

user<@faxhost>

(or, for our example,

bob@faxhost).

See Specify a Default with $: on

page 893 for a complete description of the $: operator as it is

used with database maps.

$digit

The LHS wildcard operators ($*, $+, $-, and $@) and the LHS class-matching

operators ($= and

$˜) can have

their matched values copied to the RHS by the

$digit

positional operator. Consider, for example, the

following rule:

R $+ < @ $- . $* > $: $1

Here, there are three wildcard operators in the LHS.

The first (the $+) corresponds to the $1 on the RHS. The

object of this rule is to match a focused address

and rewrite it as the username. For example,

gw@wash.dc.gov will be rewritten to

be gw.

The $digit

operator can be used only on the RHS of rules. See

Copy by Position: $digit on

page 661 for a full description of this $digit

operator.

$=

Match any token in a class LHS operator

When trying to match tokens in the workspace to

members of a class, you can use the $= operator. For

example, consider the following rule:

R $+ < @ $={InternalHosts} > $: $1 < @ mailhub >Here, the workspace is expected to hold a focused

address (such as

gw<@wash.dc.gov>). The

$={InternalHosts} expression causes

sendmail to look up the host

part of the address (the

wash.dc.gov) in the class

{InternalHosts}. If that host is found in

that class, a match is made and the workspace is

rewritten by the RHS to become

gw<@mailhub>.

Class macros in general are described in Chapter 22 on page 854, and the $= operator in particular is described

in full in Matching Any in a Class: $=

on page 863.

Note that the $=

operator can be used only on the LHS of rules, and

that the $=

operator can be referenced by an RHS $digit

operator.

$>

Rewrite through another rule set RHS operator

It is often valuable to group rule sets by function and call them as subroutines from a rule. To illustrate, consider the following rule:

R $+ < @ $+ > $: $>setHere, the RHS $>set

operator tells sendmail to

perform additional rewriting using a secondary set

of rules called set. The

workspace is passed as is to that secondary rule

set, and the result of the rewriting by that

secondary rule set becomes the new workspace.

The $> operator

is described in full in Rewrite Through a Rule Set: $>set on page 664.

$[ $]

Canonicalize hostname RHS operators

The $[ $] operators

are used to convert a non-fully qualified hostname,

or a CNAME, into the official, fully qualified

hostname. They are also used to convert square

bracket-enclosed addresses into hostnames. They must

be used in a pair with the host or address to be

looked up between them. To illustrate, consider this

rule:

R $+ < @ $+ > $: $1 < @ $[ $2 $] >

This rule will match a focused address such as

gw<@wash> and cause the

host part (the second $+ on the LHS) to be passed to the RHS

(the $2). Because

the $2 is between

the pair of $[ $]

operators, it is looked up with DNS and converted to

a fully qualified hostname. Thus, the domain

dc.gov, for example, will

have the host wash fully

qualified to become

wash.dc.gov. These $[ $] operators can be

used only on the RHS, and are fully described in

$[ and $]: A Special Case on page 895.

$( $)

Perform a database-map lookup/action RHS operators

The $( and $) operators perform a

wide range of actions. They can be used to look up

information in databases, files, or network

services, or to perform transformation (such as

dequoting), or to store values in macros. These

operators make many customizations possible. Their

simplest use might look like this:

R $- $: $( faxusers $1 $) ← look up in a database R $- $: $( dequote $1 $) ← perform a transformation

In the first line, the intention is for users listed

in the faxusers

database to have their mail delivered by fax instead

of by email. Any lone username in the workspace

(matched by the $-) is looked up (the $1 inside the $( and $) operators) in the

faxusers

database. If that username is found it that

database, the workspace is replaced by the value for

that name (perhaps something such as

user@faxhost). If the user is

not found in the database, the workspace is

unchanged.

The second line looks for any lone username in the

workspace, and dequotes (removes quotation marks

from) that name using the built-in dequote type (dequote on page 904).

Note that the $(

and $) operators

can be used only on the RHS of rules. They are fully

explained in Use $( and $) in Rules

on page 892.

$-

Match exactly one token LHS operator

The user part of an address is the part to the left of

the @ in an

address. It is usually a single token (such as

george or

taka).[257] The easiest way to match the user part

of an address is with the $- operator. For example, the following

rule looks for any username at our local domain, and

dequotes it.

R $- < @ $=w . > $: $(dequote $1 $) < @ $2 . >

Here, the intention is to take any quoted username

(such as “george” or “george+nospam”) and to change

the address using the dequote database-map type (dequote on page 904). The effect of

this rule on a quoted user workspace, then, might

look like this:

"george"@wash.dc.gov becomes → george@wash.dc.gov "george+nospam"@wash.dc.gov becomes → george+nospam@wash.dc.gov

Because the quotation character is not a token,

"george+nospam"

is seen as a single token and is matched with the

$-

operator.

The -bt

rule-testing mode offers an easy way to determine a

character splits the user part of an address into

more than one token:

%echo '0 george+nospam' | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt | head −3ADDRESS TEST MODE (ruleset 3 NOT automatically invoked) Enter <ruleset> <address> > parse input: george + nospam ← 3 tokens %echo '0 "george+nospam"' | /usr/sbin/sendmail -bt | head −3ADDRESS TEST MODE (ruleset 3 NOT automatically invoked) Enter <ruleset> <address> > parse input: "george+nospam" ← 1 token

Note that the $-

operator can be used only on the LHS of rules, and

that the $-

operator can be referenced by a $digit

operator on the RHS.

$+

Match one or more tokens LHS operator

The $+ operator is

very handy when you need to match at least one token

in the workspace. For example, recall that the host

part of an address containing zero tokens is bad,

but one containing one or more tokens is

good:

george@ ← zero tokens is bad george@wash ← one token is good george@wash.dc.gov ← many tokens is good

A rule that seeks to match the host part of an address might look like this:

R $- @ $+ $: $1 < @ $2 >

Here, the LHS matches any complete address—that is, an

address that contains a user part that is a single

token (such as george), an

@ character,

and a host part that is one or more tokens (such as

wash or

wash.dc.gov).[258] Any address that matches is rewritten by

the RHS to focus on the host part. Focusing an

address means to surround the host part in angle

braces. Thus, for example,

george@wash will become

george<@wash>.

Note that the $+

operator can be used only on the LHS of rules, and

can be referenced by a $digit

operator on the RHS.

$#

Match a literal $# LHS operator

Because the RHS can return a delivery agent

specification, it is sometimes desirable to check

for the $#

operator on the LHS of a rule. Consider, for

example, the following rule:

R $+ $| $# OK $@ $1

The LHS looks for anything (the $+) followed by a

$| operator,

and then $# OK.

This might match a workspace that was set up by a

database-map lookup or a call to another rule set.

The $# OK means

the address was OK as is, and so should be placed

back into the workspace. The RHS does just that by

returning (the $@

prefix) the original address (the $1 references the LHS

$+, which

contained the original address).

Note that the $#

operator has no special meaning in the LHS. It is

used only to detect a delivery agent-like

specification made by an earlier rule on the RHS.

The next two sections reveal how this is

done.

$#

Specify a delivery agent RHS delivery agent operator

The $# RHS operator

serves two functions. The first is to select a

delivery agent, and the second is to return the

status of a policy-checking rule set. We cover the

first in this section and the second in the

next.

When used as a prefix to the RHS or a rule set (except

when used in a policy-checking rule set), the

$# operator is

used to select a delivery agent. Consider, for

example, the following rule:

R$+ $#local $: $1

Here, the LHS looks for a workspace that contains a

username (without a host part). If such a workspace

is found, the RHS is then used to select a delivery

agent for that user. The selection of a delivery

agent is signaled by the $# prefix to the RHS. The symbolic name

of the delivery agent is set to local. The $: operator in the RHS

is described in $:

on page 676.

The $# in the RHS

must be used as a prefix or it loses its special

meaning. See Return a Selection: $#

on page 667 for a full description of this

operator.

$#

Specify return for a policy-checking rule set RHS check operator

The $# RHS operator

serves two functions. The first is to select a

delivery agent, and the second is to return the

status of a policy-checking rule set (such as

check_mail).

When used as a prefix to the RHS in one of the

policy-checking rule sets, the $# operator tells

sendmail that the message

should be either rejected, discarded, or accepted.

Consider the following three rules:

R $* $| REJECT $# error $@ 5.7.1 $: "550 Access denied" R $* $| DISCARD $# discard $: discard R $* $| OK $# OK

The first rule shows how the $# prefix is used in the RHS to specify

the error

delivery agent, which will cause the message to be

rejected.[259] The error delivery agent is fully described

in error on page 720.

The second rule shows how the $# prefix is used in the RHS to specify

the discard

delivery agent, which will cause the message to be

simply discarded. The discard delivery agent is fully

described in discard on page

719.

The last rule shows how the $# prefix is used in the RHS to specify

that the message is acceptable, and that it is OK to

deliver it.

Note that the $# in

the RHS must be used as a prefix or it loses its

special meaning. See Return a Selection: $#

on page 667 for a full description of this

operator.

$*

Match zero or more tokens LHS operator

The $* operator is

a wildcard operator. It is used to match zero or

more tokens in the workspace. One handy use for it

is to honor a pair of angle braces, regardless of

whether that pair has something between them. The

following LHS, for example, will match <>, or <wash>, or even

<some.big.long.domain>:

R < $* > ...

But because $* can

match an unexpected number of tokens, it is wise to

understand minimum matching before using it. See

Minimum Matching on page 660 for

a discussion of minimum matching and the backup and

retry process.

Note that the $*

operator can be used only on the LHS of rules, and

can be referenced by an RHS $digit

operator.

$~

Match any single token not in a specified class LHS operator

When trying to match tokens in the workspace to

members of a class, it is possible to invert the