Chapter 1. Some Basics

We began previous editions of this book with a very long tutorial aimed at those new to sendmail. In this edition, however, much of that tutorial has been folded into the chapters that follow, and we present, instead, a brief introductory chapter intended to get new people started. It begins with a look at some of the basic concepts of email and the sendmail program. We will show you sendmail’s basic parts, explore the three parts of an email message, then demonstrate how to run sendmail by hand. We finish with an overview of the roles sendmail plays and of its various modes. Lastly, we take a preliminary look at its configuration file.

Email Basics

Imagine yourself with pen and paper, writing a letter to a friend far away. You finish the letter and sign it, reflect on what you’ve written, then tuck the letter into an envelope. You put your friend’s address on the front, your return address in the lefthand corner, and a stamp in the righthand corner, and the letter is ready for mailing. Electronic mail (email for short) is prepared in much the same way, but a computer is used instead of pen and paper.

The post office transports real letters in real envelopes, whereas sendmail transports electronic letters in electronic envelopes. If your friend (the recipient) is in the same neighborhood (on the same machine), only a single post office (sendmail running locally) is involved. If your friend is in a distant location, the mail message will be forwarded from the local post office (sendmail running locally) to a distant one (sendmail running remotely) for delivery. Although sendmail is similar to a post office in many ways, it is superior in others:

Delivery typically takes seconds rather than days.

Address changes (forwarding) take effect immediately, and mail can be forwarded anywhere in the world.

Host addresses are looked up dynamically. Therefore, machines can be moved or renamed and email delivery will still succeed.

Mail can be delivered through programs that access other networks (such as Unix to Unix Communication Protocol [UUCP] and Bitnet). This would be like the post office using United Parcel Service to deliver an overnight letter.

This analogy between a post office and sendmail will break down as we explore sendmail in more detail. But the analogy serves a role in this introductory material, so we will continue to use it to illuminate a few of sendmail’s more obscure points.

Requests for Comments (RFCs)

A complete understanding of sendmail is not possible without at least some exposure to Requests for Comments (RFCs) issued by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) at the Network Information Center (NIC). These numbered documents define (among other things) the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) and the format of email message headers.

When you see a reference to an RFC in this book, it will appear, for example, as RFC2821. The RFCs of interest to sendmail are listed in the Bibliography at the end of this book.

Email and sendmail

A mail user agent (MUA) is any of the many programs that users run to read, reply to, compose, and dispose of email. Examples of an MUA include the original Unix mail program (/bin/mail); the Berkeley Mail program; its System V equivalent (mailx); free software programs such as mush, elm, pine, and mh; and commercial programs such as Zmail. Examples of MUAs also exist for PCs. Eudora and ClarisWorks are two standalone MUAs. Netscape and Explorer are web browsers that can also act as MUAs. Thunderbird is an open source MUA from the folks at Mozilla. Many MUAs can exist on a single machine. MUAs sometimes perform limited mail transport, but this is usually a very complex task for which they are not suited. We won’t be covering MUAs in this book.

A mail transfer agent (MTA) is a highly specialized program that delivers mail and transports it between machines, like the post office does. Usually, there is only one MTA on a machine. The sendmail program is an MTA.

Beginning with V8.10, sendmail also recognizes

the role of a mail submission agent (MSA), as defined in RFC2476.

MTAs are not supposed to alter an email’s text, except to add

Received:, Return-Path:, and other required

headers. Email submitted by an MUA might require more modification

than is legal for an MTA to perform, so the new role of an MSA was

created. An MSA accepts messages from an MUA, and has the legal

right to heavily add to, subtract from, and screen or alter all such

email. An MSA, for example, can ensure that all hostnames are fully

qualified, and that headers, such as Date:, are always included.

Other MTAs

The sendmail program is not the only MTA on the block. Others have existed for some time, and new MTAs appear on the scene every once in a while. Here we describe a few of the other major MTAs:

- qmail

Stressing modularity and security, qmail claims to be a replacement for sendmail. The qmail program is an open source offering, available from http://www.qmail.org.

- Postfix

Written by Wietse Venema, a security expert on the IBM Research staff, Postfix is advertised to be a drop-in replacement for sendmail that purports to deliver email more quickly, conveniently, and safely. The Postfix program is an open source offering, available from http://www.postfix.com.

- Sun ONE Messaging Server

This MTA is a multithreaded commercial product that purports to be faster and more scalable than sendmail, and is part of a large commercial offering. Information can be found at http://www.sun.com.

- Sendmail Switch[4]

This is the same sendmail we describe here, but with selected commercial enhancements, and a suite of support software that forms a complete email solution. Additional information can be found at http://www.sendmail.com.

Many other MTAs exist, some good and some not so good. We mention only five here because, after all, this is a book about the open source sendmail.

Why sendmail Is So Complex

In its simplest role, that of transporting mail from a user on one machine to another user on the same machine, sendmail is almost trivial. All vendors supply a sendmail (and a configuration file) that will accomplish this. But as your needs increase, the job of sendmail becomes more complicated, and its configuration file becomes more complex. On hosts that are connected to the Internet, for example, sendmail should use the Domain Name System (DNS) to translate hostnames into network addresses. Machines with UUCP connections, on the other hand, need to have sendmail run the uux program.

The sendmail program needs to transport mail between a wide variety of machines. Consequently, its configuration file is designed to be very flexible. This concept allows a single binary to be distributed to many machines, where the configuration file can be customized to suit particular needs. This configurability contributes to making sendmail complex.

When mail needs to be delivered to a particular user, for example, the sendmail program decides on the appropriate delivery method based on its configuration file. The decision process might include the following steps:

If the recipient receives mail on the same machine as the sender, sendmail delivers the mail using the /usr/sbin/mail.local program.

If the recipient’s machine is connected to the sending machine using UUCP, it uses uux to send the mail message.

If the recipient’s machine is on the Internet, the sending machine transports the mail using SMTP.

Otherwise, the mail message might need to be transported over another network (such as Bitnet) or possibly rejected.

Basic Parts of sendmail

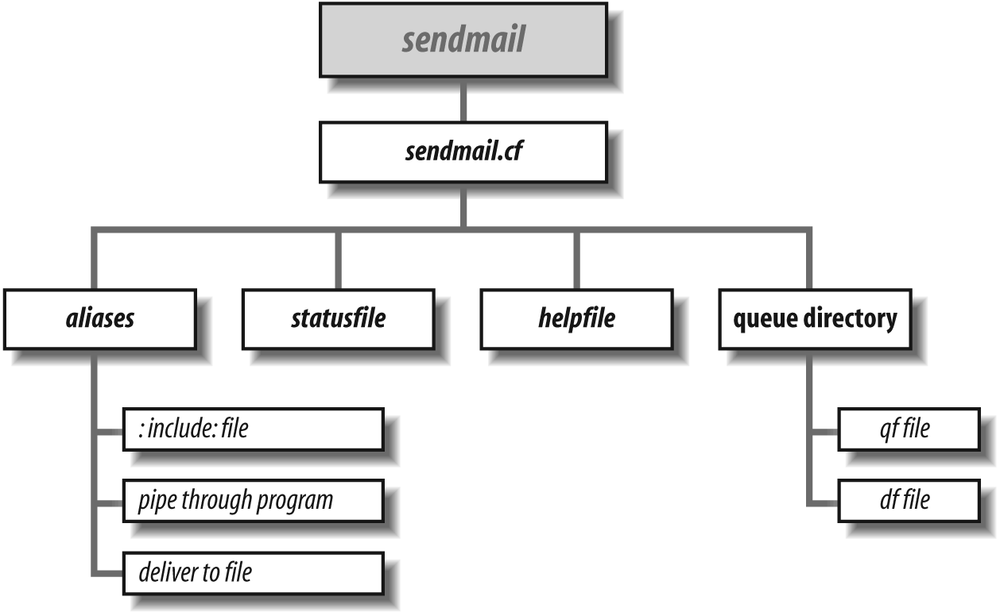

The sendmail program is actually composed of several parts, including programs, files, directories, and the services it provides. Its foundation is a configuration file that defines the location and behavior of these other parts and contains rules for rewriting addresses. A queue directory holds mail until it can be delivered. An aliases file allows alternative names for users and the creation of mailing lists. Database files can handle tasks ranging from spam rejection to virtual hosting.

The Configuration File

The configuration file contains all the information sendmail needs to do its job. Within it you provide information, such as file locations, permissions, and modes of operation.

Rewriting rules and rule sets also appear in the configuration file. They transform a mail address into another form that might be required for delivery. They are perhaps the single most confusing aspect of the configuration file. Because the configuration file is designed to be fast for sendmail to read and parse, rules can look cryptic to humans:

R $+ @ $+ $: $1 < @ $2 > focus on domain R $+ < $+ @ $+ > $1 $2 < @ $3 > move gaze right

But what appears to be complex is really just succinct. The

R at the

beginning of each line, for example, labels a

rewrite rule. And the $+ expressions mean to

match one or more parts of an address. With experience, such

expressions (and indeed the configuration file as a whole)

soon become meaningful.

Fortunately, you don’t need to learn the details of rule sets to configure and install sendmail. The mc form of configuration insulates you from such details, and allows you to perform very complex tasks easily.

The Queue

Not all mail messages can be delivered immediately. When delivery is delayed, sendmail must be able to save messages for later transmission. The sendmail queue comprises one or more directories that hold mail until it can be delivered. A mail message can be queued:

When the destination machine is unreachable or down. The mail message will be delivered when the destination machine returns to service.

When a mail message has many recipients. Some mail messages might be successfully delivered but others might not. Those that have transient failures are queued for later delivery.

When a mail message is expensive. Expensive mail (such as mail sent over a long-distance phone line) can be queued for delivery when rates are lower.

When (beginning with V8.11) authentication or stream encryption suffers a temporary failure to start. In this case, the message is queued for a later try.

Because safety is always primary concern. The sendmail program is configured to queue all mail messages by default, thus minimizing the risk of loss should the machine crash.

Aliases and Mailing Lists

Aliases allow mail that is sent to one address to be redirected to another address. They also allow mail to be appended to files or piped through programs, and form the basis of mailing lists. The heart of aliasing is the aliases(5) file (often stored in database format for swifter lookups). Aliasing is also available to the individual user via a file called ~/.forward in the user’s home directory.

Basic Parts of a Mail Message

In this section, we will examine the three parts that make up a mail message: the header, body, and envelope. But before we do, we must first demonstrate how to run sendmail by hand so that you can see what a message’s parts look like.

Run sendmail by Hand

Most users do not run sendmail directly. Instead, they use one of many MUAs to compose a mail message. Those programs invisibly pass the mail message to sendmail, creating the appearance of instantaneous transmission. The sendmail program then takes care of delivery in its own seemingly mysterious fashion.

Although most users don’t run sendmail directly, it is perfectly legal to do so. You, like many system managers, might need to do this to track down and solve mail problems.

Here’s a demonstration of one way to run sendmail by hand. First create a file named sendstuff with the following contents:

This is a one-line message.

Second, mail this file to yourself with the following command

line, where you is your login

name:

%/usr/sbin/sendmailyou<sendstuff

Here, you run sendmail directly by

specifying its full pathname.[5] When you run sendmail, any

command-line arguments that do not begin with a - character are considered

to be the names of the people to whom you are sending the

mail message.

The <sendstuff sequence

causes the contents of the file that you have created

(sendstuff) to be redirected

into the sendmail program. The

sendmail program treats

everything it reads from its standard input (up to the end

of the file) as the mail message to transmit.[6]

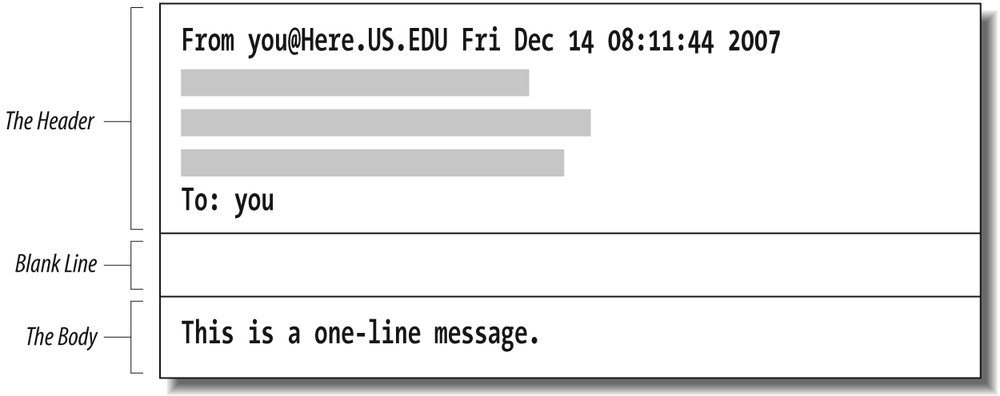

Now view the mail message you just sent. How you do this will vary. Many users just type mail to view their mail. Others use the mh(1) package and type inc to receive and show to view their mail. No matter how you normally view your mail, save the mail message you just received to a file. It will look something like this:

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 14 08:11:44 2007

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:44 −0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200712141548.d872mLW24467@Here.US.EDU>

To: you ← might be something else (see §24.9.81 on

page 1060)

This is a one-line message.The first thing to note is that this file begins with seven lines of text that were not in your original message. Those lines were added by sendmail and your local delivery program and are called the header.

The last line of the file is the original line from your sendstuff file. It is separated from the header by one blank line. The body of a mail message comes after the header and consists of everything that follows the first blank line (see Figure 1-1).

Ordinarily, when you send mail with your MUA, the MUA adds a header and feeds both the header and the body to sendmail. This time, however, you ran sendmail directly and supplied only a body; the header was added by sendmail.

The Header

Let’s examine the header in more detail:

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 14 08:11:44 2007

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:44 −0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200712141511.d872mLW24467@Here.US.EDU>

To: you ← might be something else (see §24.9.81 on

page 1060)Notice that most header lines start with a word followed by a

colon. Each word tells what kind of information the rest of

the line contains. Many types of header lines can appear in

a mail message. Some are mandatory, some are optional, and

some can appear many times. Those that appeared in the

message you mailed to yourself were all mandatory.[7] That’s why sendmail added

them to your message. The line starting with the five

characters "From " (the

fifth character is a space) is added by some programs (such

as /bin/mail) but not by others (such

as mh).

A Received: line is added

each time a machine receives the mail message. (If there are

too many such lines, the mail message will

bounce—because it is probably

in a loop—and will be returned to the sender as failed

mail.) The indented line is a continuation of the line

above, the Received:

line. The Date: line

gives the date and time when the message was originally

sent. The From: line

lists the email address and the full name of the sender. The

Message-ID: line

is like a serial number in that it is guaranteed to uniquely

identify the mail message. And the To:[8] line shows a list of one or more recipients.

(Multiple recipients would be separated with commas.)

A complete list of all header lines that are of importance to sendmail is presented in Chapter 25 on page 1120. The important concept here is that the header precedes, and is separate from, the body in all mail messages.

The Body

The body of a mail message consists of everything following the first blank line to the end of the file. When you sent your sendstuff file, it contained only a body. Now, edit the file sendstuff and add a small header:

Subject: a test ← add

← add

This is a one-line message.The Subject: header line is

optional. The sendmail program passes

it through as is. Here, the Subject: line is followed by a blank line

and then the message text, forming a header and a body. Note

that a blank line must be truly blank. If you put space or

tab characters in it, thus forming an “empty-looking” line,

the header will not be separated from

the body as intended.

Send this file to yourself again, running sendmail by hand as you did before:

%/usr/sbin/sendmailyou<sendstuff

Notice that our Subject:

header line was carried through without change:

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 14 08:11:44 2007

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:44 −0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 14 Dec 2007 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200712141511.d9BMTuX29709@Here.US.EDU>

Subject: a test ← note

To: you

This is a one-line message.The Envelope

So that it can more easily handle delivery to diverse recipients, the sendmail program uses the concept of an envelope. This envelope is analogous to the physical envelopes that are used for post office mail. Imagine you want to send two copies of a document, one to your friend in the office next to yours and one to a friend across the country:

To: friend1, friend2@remote

After you photocopy the document, you stuff each copy into a

separate envelope. You hand one envelope to a clerk, who

carries it next door and hands it to friend1 in the next

office. This is like delivery on your local machine. The

clerk drops the other copy in the slot at the corner

mailbox, and the post office forwards that envelope across

the country to friend2@remote. This is like

sendmail transporting a mail

message to a remote machine.

To illustrate what an envelope is, consider one way in which sendmail might run /usr/lib/mail.local, a program that performs local delivery:

deliver to friend1's mailbox ↓ /usr/lib/mail.local -d friend1 ← sendmail runs ↑ the envelope recipient

Here sendmail runs

/usr/lib/mail.local with a

-d, which tells

/usr/lib/mail.local to append

the mail message to friend1’s mailbox.

Information that describes the sender or recipient, but is not part of the message header, is considered envelope information. The two might or might not contain the same information (a point we’ll gloss over for now). In the case of /usr/lib/mail.local, the email message shows two recipients in its header:

To: friend1, friend2@remote ← the headerBut the envelope information that is given to /usr/lib/mail.local shows only one (the one appropriate to local delivery):

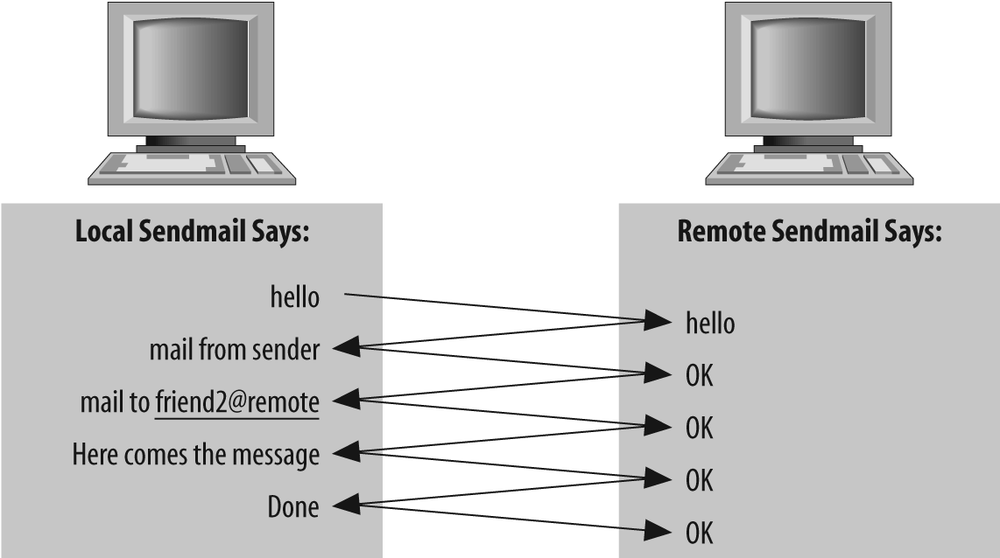

-d friend1 ← specifies the envelopeNow consider the envelope of a message transported over the network. When sending network mail, sendmail must give the remote site the envelope-sender address and a list of recipients separate from and before it sends the mail message (header and body). Figure 1-2 shows this in a greatly simplified conversation between the local sendmail and the remote machine’s sendmail.

The local sendmail tells the remote

machine’s sendmail that there is mail

from you (the envelope-sender) and for friend2@remote. It conveys

this envelope-sender and recipient information

separate from and

before it transmits the mail

message that contains the header. Because this information

is conveyed separately from the message header, it is called

the envelope.

Only one recipient is listed in the envelope, whereas two were listed in the message header:

To: friend1, friend2@remote

The remote machine should not need to know about the local

user, friend1, so that

bit of recipient information is excluded from the

envelope.

A given mail message can be sent by using many different envelopes (like the two here), but the header will be common to them all. Note that the headers of a message don’t necessarily reflect the actual envelope. You witness such mismatches whenever you receive a message from a mailing list or receive a spam message.

Basic Roles of sendmail

The sendmail program plays a variety of roles, all critical to the proper flow of electronic mail. It listens to the network for incoming mail, transports mail messages to other machines, and hands local mail to a local program for local delivery. It can append mail to files and pipe mail through other programs. It can queue mail for later delivery and understand the aliasing of one recipient name to another.

Role in the Filesystem

The sendmail program’s role (position) in the local filesystem hierarchy can be viewed as an inverted tree (see Figure 1-3).

When sendmail is run, it first reads the /etc/mail/sendmail.cf configuration file. Among the many items contained in that file are the locations of all the other files and directories that sendmail needs.

Files and directories listed in sendmail.cf are usually specified as full pathnames for security (such as /var/spool/mqueue rather than mqueue). As the first step in our tour of those files, run the following command to gather a list of them:[9]

% grep =/ /etc/mail/sendmail.cfThe output produced by the grep(1) command might appear something like the following:[10]

O AliasFile=/etc/mail/aliases #O ErrorHeader=/etc/mail/error-header O HelpFile=/etc/mail/helpfile O QueueDirectory=/var/spool/mqueues/q.* O StatusFile=/etc/mail/statistics #O UserDatabaseSpec=/etc/mail/userdb #O ServiceSwitchFile=/etc/mail/service.switch #O HostsFile=/etc/hosts #O SafeFileEnvironment=/arch #O DeadLetterDrop=/var/tmp/dead.letter O ControlSocketName=/var/spool/mqueues/.control #O PidFile=/var/run/sendmail.pid #O DefaultAuthInfo=/etc/mail/default-auth-info Mlocal, P=/usr/lib/mail.local, F=lsDFMAw5:/|@qPSXfmnz9, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromL, Mprog, P=/bin/sh, F=lsDFMoqeu9, S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL, R=EnvToL/HdrToL, D=$z:/,

Notice that some lines begin with an O character, some with an M, and others with a

#. The O marks a line as a

configuration option. The word following the O is the name of the

option. The options in the preceding output show the

location of the files that sendmail

uses. AliasFile, for

example, defines the location of the

aliases(5) database. The lines

that begin with M define

delivery agents. The lines that

begin with a # are

comments.

First we will examine the files in the O option lines. Then we

will discuss local delivery and the files in the M delivery agent

lines.

Role in the aliases File

Aliasing is the process of converting one recipient name into another. One use is to convert a generic name (such as root) into a real username. Another is to convert one name into a list of many names (for mailing lists).

Take a few moments to examine your

aliases file. Its location is

determined by the AliasFile option in your

sendmail.cf file. For

example:

O AliasFile=/etc/mail/aliases

Compare what you find in your aliases file to the brief example of an aliases file listed here:

# Mandatory aliases. postmaster: bob MAILER-DAEMON: postmaster abuse: postmaster # The five forms of aliases John_Adams: adamj xpres: ford,carter,reagan,clinton oldlist: :include:/usr/local/oldguys nobody: /dev/null ftphelp: |/usr/local/bin/sendhelp

Your aliases file is probably far more complex, but even so, note that the example shows all the possible forms of aliases.

Lines that begin with # are

comments. Empty lines are ignored. As the first comment

indicates, three aliases are mandatory in every

aliases file. They are the

simplest form of alias: a name and what to change that name

into. The name on the left of the : is changed into the name

on the right. Names are not case-sensitive. For example,

POSTMASTER,

Postmaster, and

postmaster are

all the same.[11]

For every envelope that lists a local user as a recipient,

sendmail looks up that

recipient’s name in the aliases file.

(A local user is any address that

would normally be delivered on the local machine. That is,

postmaster is local, whereas

postmaster@remote might not

be.) When sendmail is processing the

envelope, and when it matches the recipient to one of the

names on the left of the aliases file,

it replaces that recipient name with the text to the right

of the : character. For example, the envelope recipient

postmaster

becomes the new envelope recipient bob.

After a name is substituted, the new name is then looked up,

and the process is repeated until no more matches are found.

The name MAILER-DAEMON is

first changed to postmaster. Then postmaster is looked up again and changed

to bob. Because there is

no entry for bob in the

aliases file, the mail message

is delivered into bob’s mailbox.

Every aliases file must have an alias for

postmaster that

will expand to the name of a real user.[12] Mail about mail problems is always sent to

postmaster both

by mail-related programs and by users who are having trouble

sending mail.

When mail is bounced (returned because

it could not be delivered), it is always sent from MAILER-DAEMON. That alias

is needed because users might reply to bounced mail. Without

it, replies to bounced mail would themselves bounce.

The five types of lines in an aliases file are as follows:

John_Adams: adamj xpres: ford,carter,reagan,clinton oldlist: :include:/usr/local/oldguys nobody: /dev/null ftphelp: |/usr/local/bin/sendhelp

You have already seen the first line (it was the form used to

convert postmaster to

bob). In the

previous example, mail sent to John_Adams is delivered to the user whose

login name is adamj.

The xpres: line shows how

one name can be expanded into a list of many names. Each new

name becomes a new name for further alias processing. If a

name can’t be further expanded, a copy of the mail message

is delivered to it.

The oldlist: line shows how

a mailing list can be read from a file. The expression

:include: tells

sendmail to read a specific

file and to use the names in that file as the list of

recipients.

The nobody: line shows how

a name can be aliased to a file. The mail message is

appended to the file. The /dev/null

file listed here is a special one. That file is an empty

hole into which the mail message simply vanishes.

The ftphelp: line shows how

a name can be replaced by the name of a program. The

| character

causes sendmail to pipe the mail

message through the program whose full pathname follows (in

this case, we specified the full pathname as

/usr/local/bin/sendhelp).

The aliases file can become very complex. It can be used to solve many special mail problems. The aliases file is covered in greater detail in Chapter 12 on page 460.

Role in Queue Management

A mail message can be temporarily undeliverable for a wide variety of reasons, such as when a remote machine is down or has a temporary disk problem. To ensure that such a message is eventually delivered, sendmail stores it in a queue directory until the message can be delivered successfully.

The QueueDirectory option

in your configuration file tells

sendmail where to find its

queue directory:

O QueueDirectory=/var/spool/mqueue

The location of that directory must be a full pathname. Its

exact location varies from vendor to vendor, but you can

always find it by looking for the QueueDirectory option in your

configuration file.

Beginning with V8.10, sendmail allows multiple queue directories to be used. Such a declaration can look like this:

O QueueDirectory=/var/spool/queues/q.*

Here, sendmail will use the subdirectories in /var/spool/queues that begin with the name q. for storage of messages. Such directories might be called, for example, q.00 and q.01.

If you have permission, take a look at a sendmail queue directory. It might be empty if no mail is waiting to be sent. If it is not empty, it will contain files such as these:

dfg17NVhbh002596 dfg1BHotav010793 qfg17NVhbh002596 qfg1BHotav010793

When a mail message is queued, it is split into two parts,

each part being saved in a separate file. The header

information is saved in a file whose name begins with the

characters qf. The body

of the mail message is saved in a file whose name begins

with the characters df.

The previous example shows two queued mail messages. One is

identified by the unique string g17NVhbh002596 and the other by g1BHotav010793.

The internals of the queue files and the processing of those files are covered in Chapter 11 on page 394.

Role in Local Delivery

Another role of the sendmail program is to deliver mail messages to local users. A local user is one who has a mailbox on the local filesystem. Delivering local mail is done by appending a message to the user’s mailbox, by feeding the mail message to a program, or by appending the message to a file other than the user’s mailbox.

In general, sendmail does not put mail messages directly into files. You saw the exception in the aliases file, in which you could specifically tell sendmail to append mail to a file. This is the exception, not the rule. Usually, sendmail calls other programs to perform delivery. Those other programs are called delivery agents.[13]

In your sendmail.cf file you found two lines that defined local delivery agents, the ones that sendmail uses to deliver mail to the local filesystem:

Mlocal, P=/usr/lib/mail.local, F=lsDFMAw5:/|@qPSXfmnz9, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromL, Mprog, P=/bin/sh, F=lsDFMoqeu9, S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL, R=EnvToL/HdrToL, D=$z:/,

The /usr/lib/mail.local program is used to append mail to the user’s mailbox. The /bin/sh program is used to run other programs that handle delivery.

Delivery to a Mailbox

The configuration file line that begins with Mlocal defines how mail is

appended to a user’s mailbox file. That program is usually

/usr/lib/mail.local (or with

older systems, /bin/mail) but can

easily be a program such as deliver(1)

or procmail(1).

Under Unix, a user’s mailbox is a single file that contains a

series of mail messages. The usual Unix convention (but not

the only possibility) is that each message in a mailbox

begins with a line that starts with the five characters

"From " (the

fifth is a blank space) and ends with a blank line.

The sendmail program neither knows nor

cares what a user’s mailbox looks like. All it cares about

is the name of the program that it must run to add mail

messages to that mailbox. In the example, that program is

/usr/lib/mail.local. The

M configuration

lines that define delivery agents are covered in detail in

Chapter 20

on page 711.

Delivery Through a Program

Mail addresses that begin with a | character are the names of programs to

run. You saw one such address in the example

aliases file:

ftphelp: |/usr/local/bin/sendhelp

Here, mail sent to the address ftphelp is transformed via an alias into

the new address |/usr/local/bin/sendhelp. The | character at the start

of this new address tells sendmail that

this is a program to run rather than a file to append to.

The intention here is that the program will receive the mail

and do something useful with it.

The sendmail program doesn’t run mail

delivery programs directly. Instead, it runs a shell and

tells that shell to run the program. The name of the shell

is listed in the configuration file in a line[14] that begins with Mprog:

Mprog, P=/bin/sh, F=lsDFMoqeu9, S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL, R=EnvToL/HdrToL, D=$z:/,

In this example, the shell is the /bin/sh(1). Other programs can appear in this line, such as /bin/ksh(1), the Korn Shell, or smrsh(1), the sendmail restricted shell that is supplied with the source distribution.

Role in Network Transport

Another role of sendmail is that of transporting mail to other machines. A message is transported when sendmail determines that the recipient is not local. The following lines from a typical configuration file define delivery agents for transporting mail to other machines:

Msmtp, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuX, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, Muucp, P=/usr/bin/uux, F=DFMhuUd, S=FromU, R=EnvToU/HdrToU, M=100000,

The actual lines in your file might differ. The name smtp in the preceding

example might appear in your file as ether or ddn or something else. The

name uucp might appear as

suucp or uucp-dom. There might be

more such lines than we’ve shown here. The important point

for now is that some delivery agents deal with local

delivery, whereas others deal with delivery over a

network.

Role in TCP/IP

The sendmail program has the internal ability to transport mail over only one kind of network, one that uses TCP/IP; the following line instructs sendmail to do this:

Msmtp, P=[IPC], F=mDFMuX, S=EnvFromSMTP/HdrFromSMTP, R=EnvToSMTP/HdrFromSMTP,

The [IPC] might appear as

[TCP], but note

that, beginning with V8.10 sendmail,

the expression [TCP] is

deprecated, and it has been dropped entirely in

V8.12.

When sendmail transports mail on a TCP/IP network, it first sends the envelope-sender’s address to the other site. If the other site accepts the sender’s address as legal, the local sendmail then sends the list of envelope-recipient addresses. The other site accepts or rejects each recipient address one by one. If any recipient addresses are accepted, the local sendmail sends the message (header and body together). This kind of transaction for sending email is called SMTP and is defined in RFC2821.

Role in UUCP

UUCP is an old-style means of moving email between machines that are only connected with dial-up modems. The line in the configuration file that tells sendmail how to transport over UUCP might look, in part, like this:

Muucp, P=/usr/bin/uux, F=DFMhuUd, S=12, R=22/42, M=10000000,

This line tells sendmail to send UUCP network mail by running the /usr/bin/uux (UNIX to UNIX eXecute) program.

Role in Other Protocols

sendmail can use many other kinds of network protocols to transport email. Some of them might have shown up when you ran grep earlier. Other common possibilities might look, in part, like one of these:

Mfax, P=/usr/local/bin/faxmail, F=DFMhu, S=14, R=24, M=100000, Mmail11, P=/usr/etc/mail11, F=nsFx, S=Mail11From, R=Mail11To, Mmac, P=/usr/bin/macmail, F=CDFMmpsu, S=MailMacFrom, R=MailMacTo, A=macmail -t $u

The Mfax line defines one

of the many possible ways to send a fax using

sendmail. A fax machine

transports images of documents over telephone lines. In the

preceding configuration line, the

/usr/local/bin/faxmail program

is run, and a mail message is fed to it for conversion to

and transmission as a fax image.

The Mmail11 line defines a

way of using the mail11(1) program to

transport email over a DECnet network, used mostly by the

Open VMS operating system (formerly by Digital Equipment

Corporation).

The Mmac line defines a way

to transport mail to Macintosh machines that are connected

on an AppleTalk network.

In all these examples, note that sendmail sends email over other networks by running programs that are tailored specifically for that use. Remember that the only network sendmail can use directly is a TCP/IP-based network.[15]

Role As a Daemon

Just as sendmail can transport mail messages over a TCP/IP-based network, it can also receive mail that is sent to it over the network. To do this, it must be run in daemon mode. A daemon is a program that runs in the background independent of terminal control.

As a daemon, sendmail is started once, usually when your machine is booted. Whenever an email message is sent to your machine, the sending machine talks to the sendmail daemon that is listening on your machine.

%grep sendmail /etc/rc*←BSD-based systems %grep sendmail /etc/init.d/*←SysV-based systems %grep sendmail /etc/*rc←HP-UX systems (prior to HP-UX 10.0)

One typical example of what you will find is:

/etc/rc.local:if [ -f /usr/lib/sendmail -a -f /etc/mail/sendmail.cf ]; then /etc/rc.local: /usr/lib/sendmail -bd -q1h; echo -n ' sendmail'

The second line in this example shows that sendmail is run at boot time with a command line of:

/usr/lib/sendmail -bd -q1h

The -bd command-line switch

tells sendmail to run in daemon mode.

The -q1h command-line

switch tells sendmail to wake up once

per hour and process the queue. Command-line switches are

covered in Chapter 6 on

page 220.

Basic Modes of sendmail

Besides the daemon mode (discussed earlier), sendmail can be run in a number of other useful modes. In this section, we’ll have a look at some of these. Others we’ll leave for later.

How to Run sendmail

One way to run sendmail is to provide it

with the name of a recipient as the only command-line

argument. For example, the following sends a mail message to

george:

% /usr/lib/sendmail georgeMultiple recipients can also be given. For example, the

following sends a mail message to george, truman, and teddy:

% /usr/lib/sendmail george,truman,teddyThe sendmail program accepts two

different kinds of command-line arguments. Arguments that

do not begin with a - character (such as

george) are

assumed to be recipients. Arguments that

do begin with a - character are taken as

switches that determine the behavior of

sendmail. The recipients must

always follow all the switched arguments. Any switched

arguments that follow recipients will be interpreted as

recipient addresses, potentially causing bounced

mail.

In this chapter, we will cover only a few of these switch-style command-line arguments (see Table 1-1). The complete list of command-line switches, along with an explanation of each, is presented in Chapter 6 on page 220.

|

Flag |

Description |

|

|

Set operating mode. |

|

|

Run in verbose mode. |

|

|

Run in debugging mode. |

Become a mode (-b)

The sendmail program can function

in a number of different ways depending on which

form of -b

argument you use. One form, for example, causes

sendmail to display the

contents of the queue. Another causes

sendmail to rebuild the

aliases database. A complete

list of the -b

command-line mode-setting switches is shown in Table 1-2.

We will cover only a few in this chapter.

|

Form |

Description |

|

|

Use ARPAnet (Grey Book) protocols. |

|

|

Run as a daemon, but don’t fork. |

|

|

Run as a daemon. |

|

|

Purge persistent host status. |

|

|

Print persistent host status. |

|

|

Rebuild alias database. |

|

|

Be a mail sender. |

|

|

Print number of entries in the queue (V8.12 and above). |

|

|

Print the queue. |

|

|

Run SMTP on standard input. |

|

|

Test mode: resolve addresses only. |

|

|

Verify: don’t collect or deliver. |

|

|

Freeze the configuration file (obsolete). |

The effects of some of the options in Table 1-2 can also be achieved by running sendmail using a different name. Other names and a description of their results are shown in Table 1-3. Each name can be a hard link with or a symbolic link to sendmail.

Daemon mode (-bd)

The sendmail program can run as a daemon in the background, listening for incoming mail from other machines. The sendmail program reads its configuration file only once, when it first starts as a daemon. It then continues to run forever, never reading the configuration file again. As a consequence, it will never see any changes to that configuration file.

Thus, when you change something in the sendmail.cf configuration file, you always need to kill and restart the sendmail daemon. But before you can kill the daemon, you need to know how to correctly restart it. This information is in the /var/run/sendmail.pid file or one of your system rc files.

On a Berkeley Unix-based system, for example, the daemon is usually started like this:

/usr/sbin/sendmail -bd -q1h

The -bd

command-line switch specifies daemon mode. The

-q switch tells

sendmail how often to look in

its queue to process pending mail. The -q1h switch says to

process the queue at one (1) hour (h) intervals.

The actual command to start the sendmail daemon on your system might be different from what we’ve shown. If you manage many different brands of systems, you’ll need to know how to start the daemon on all of them.

Kill and Restart, Beginning with V8.7

Killing and restarting the sendmail daemon became easier beginning with V8.7. A single command[16] will kill and restart the daemon. In the following command, you might need to replace the path /var/run with one appropriate to your operating system (such as /etc/mail):

% kill -HUP `head −1 /var/run/sendmail.pid'This single command has the same effect as the two commands shown for V8.6 in the following sections.

Kill and restart with V8.6

Before you can start the sendmail daemon, you need to make sure there is not a daemon running already.

Beginning with V8.6, the pid of the currently running daemon is found in the first line of the /etc/mail/sendmail.pid file. The process of killing the daemon looks like this:

% kill −15 `head −1 /etc/mail/sendmail.pid'After killing the currently running daemon, you can start a new daemon with the following simple command:

% `tail −1 /etc/mail/sendmail.pid'Kill and restart, very old versions

Under old versions of sendmail, you need to use the ps(1) program to find the pid of the daemon. How you run ps is different on BSD Unix and System V Unix. For BSD Unix the command you use and the output it produces resemble the following:

%ps ax | grep sendmail | grep -v grep99 ? IW 0:07 /usr/lib/sendmail -bd -q1h %kill −15 99

Here, the leftmost number printed by

ps (the 99) was used to kill the

daemon.

For System V-based systems you use different arguments for the ps command, and its output differs:

%ps -ae | grep sendmail99 ? 0:01 sendmail %kill −15 99

Under old versions of sendmail, you must look in your system rc files for the way to restart sendmail.

If you forget to kill the daemon

If you forget to kill the daemon before starting a new one, you might see a stream of messages similar to the following, one printed every five seconds (probably to your console window):

... getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use getrequests: cannot bind: Address already in use opendaemonsocket: server SMTP socket wedged: exiting

This shows that the attempt to run a second daemon failed.[17]

Show Queue Mode (-bp)

The sendmail program can also display the

contents of its queue directories. It can do this in two

ways: by running as a program named

mailq or by being run as

sendmail with the -bp command-line switch.

Whichever way you run it, the contents of the queue are

printed. If the queue is empty,

sendmail prints the

following:

/var/spool/mqueue is empty

If, on the other hand, mail is waiting in the queue, the output is far more verbose, possibly containing lines similar to these:

/var/spool/mqueue (1 requests)

--Q-ID------ --Size-- ----Q-Time------ ------------Sender/Recipient------------

d8BJXvF13031* 702 Fri Dec 14 16:51 <you@here.us.edu>

Deferred: Host fbi.dc.gov is down

<george@fbi.dc.gov>Here, the output produced with the -bp switch shows that only one mail

message is in the queue. If there were more, each entry

would look pretty much the same as this. Each message

results in at least two lines of output.

The first line shows details about the message and the sender.

The d8BJXvF13031

identifies this message in the queue directory

/var/spool/mqueue. The * shows

that this message is locked and currently being processed.

The 702 is the size of

the message body in bytes (the size of the

df file as mentioned in

Role in Queue Management on page

14). The date shows when this message was originally queued.

The address shown is the name of the sender.

A second line might appear giving a reason for failure (if there was one). A message can be queued intentionally or because it couldn’t immediately be delivered.

The third and possibly subsequent lines show the addresses of the recipients.

If there is more than one queue, each queue will print the preceding information, and the last queue’s information will be followed by a line that looks like this:

Total Requests: numHere, beginning with V8.10, the num

will be the total number of messages stored in all the queue

directories.

The output produced by the -bp switch is covered more fully in Chapter 11 on page 394.

Rebuild Aliases Mode (-bi)

Because sendmail might have to search through thousands of names in the aliases file, a version of the file is stored in a separate dbm(3) or db(3) database format file. The use of a database significantly improves lookup speed.

Although early versions of sendmail can

automatically update the database whenever the

aliases file is changed, that

is no longer possible with modern versions.[18] Now, you need to rebuild the database yourself,

either by running sendmail using the

command newaliases or with the -bi command-line switch.

Both do the same thing:

%newaliases%/usr/lib/sendmail -bi

There will be a delay while sendmail rebuilds the aliases database; then a summary of what it did is printed:

/etc/mail/aliases: 859 aliases, longest 615 bytes, 28096 bytes total

This line shows that the database was successfully rebuilt. Beginning with V8.6 sendmail, multiple alias files became possible, so each line (and there might be many) begins with the name of an alias file. The information then displayed is the number of aliases processed, the size of the biggest entry to the right of the : in the aliases file, and the total number of bytes entered into the database. Any mistakes in an alias file will also be printed here.

The aliases file and how to manipulate it are covered in Chapter 12 on page 460.

Verify Mode (-bv)

A handy tool for checking aliases is the -bv command-line switch.

It causes sendmail to recursively look

up an alias and report the ultimate real name that it

found.

To illustrate, consider the following aliases file:

animals: farmanimals,wildanimals bill-eats: redmeat birds: farmbirds,wildbirds bob-eats: seafood,whitemeat farmanimals: pig,cow farmbirds: chicken,turkey fish: cod,tuna redmeat: animals seafood: fish,shellfish shellfish: crab,lobster ted-eats: bob-eats,bill-eats whitemeat: birds wildanimals: deer,boar wildbirds: quail

Although you can figure out what the name ted-eats ultimately

expands to, it is far easier to have

sendmail do it for you. By

using sendmail, you have the added

advantage of being assured accuracy, which is especially

important in large and complex aliases

files.

In addition to expanding aliases, the -bv switch performs another important

function. It verifies whether the expanded aliases are, in

fact, deliverable. Consider the following one-line

aliases file:

root: fred,larry

Assume that the user fred

is the system administrator and has an account on the local

machine. The user larry,

however, has left, and his account has been removed. You can

run sendmail with the -bv switch to find out

whether both names are valid:

% /usr/lib/sendmail -bv rootThis tells sendmail to verify the name

root from the

aliases file. Because larry (one of root’s aliases) doesn’t

exist, the output produced looks like this:

larry... User unknown fred... deliverable: mailer local, user fred

Verbose Mode (-v)

The -v command-line switch

tells sendmail to run in

verbose mode. In that mode,

sendmail prints a

blow-by-blow[19] description of all the steps it takes in

delivering a mail message. To watch

sendmail run in verbose mode,

send mail to yourself as you did in Run sendmail by Hand on page 6, but this

time add a -v

switch:

%/usr/lib/sendmail -vyou<sendstuff

The output produced shows that sendmail delivers your mail locally:

you...Connecting to local...you...Sent

When sendmail forwards mail to another

machine over a TCP/IP network, it communicates with that

other machine using the SMTP protocol. To see what SMTP

looks like, run sendmail again, but

this time, instead of using you

as the recipient, give sendmail your

address on another machine:

%/usr/lib/sendmail -vyou@remote.domain<sendstuff

The output produced by this command line will look similar to the following:

you@remote.domain... Connecting to remote.domain via smtp... 220 remote.Domain ESMTP Sendmail 8.14.1/8.14.1 ready at Fri, 14 Dec 2007 06:36:12 −080 0 >>> EHLO here.us.edu 250-remote.domain Hello here.us.edu [123.45.67.89], pleased to meet you 250-ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES 250-8BITMIME 250-SIZE 250-DSN 250-ETRN 250-DELIVERBY 250 HELP >>> MAIL From:<you@here.us.edu> SIZE=4537 250 2.1.0 <you@here.us.edu> ... Sender ok >>> RCPT To:<you@remote.domain> 250 2.1.5 <you@remote.domain> ... Recipient ok >>> DATA 354 Enter mail, end with "." on a line by itself >>> . 250 2.0.0 d9L29Nj20475 Message accepted for delivery you@remote.domain... Sent (d9L29Nj20475 Message accepted for delivery) Closing connection to remote.domain >>> QUIT 221 remote.domain closing connection

The lines that begin with numbers and the lines that begin

with >>>

characters constitute a record of the SMTP conversation.

We’ll discuss those shortly. The other lines are

sendmail on your local machine

telling you what it is trying to do and what it has

successfully done:

you@remote.domain... Connecting to remote.domain via smtp... ... you@remote.domain... Sent (d9L29Nj20475 Message accepted for delivery) Closing connection to remote.domain

The first line shows to whom the mail is addressed and that

the machine remote.domain

is on the network. The last two lines show that the mail

message was successfully sent.

In the SMTP conversation, your local machine displays what it

is saying to the remote host by preceding each line with

>>>

characters. The messages (replies) from the remote machine

are displayed with leading numbers. We now explain that

conversation.

220 remote.Domain ESMTP Sendmail 8.14.1/8.14.1 ready at Fri, 14 Dec 2007 06:36:12 −080 0

Once your sendmail has connected to the

remote machine, your sendmail waits for

the other machine to initiate the conversation. The other

machine says it is ready by sending the number 220 and its fully

qualified hostname (the only required information). If the

other machine is running sendmail, it

may also say the program name is

sendmail and state the version.

It may also state that it is ready and gives its idea of the

local date and time.

The ESMTP means that the

remote site understands Extended SMTP.

If sendmail waits too long for a connection without receiving this initial message, it prints “Connection timed out” and queues the mail message for later delivery.

Next, the local sendmail sends (the

>>>) the

word EHLO, for Extended

Hello, and its own hostname:

>>> EHLO here.us.edu 250-remote.domain Hello here.us.edu [123.45.67.89], pleased to meet you 250-ENHANCEDSTATUSCODES 250-8BITMIME 250-SIZE 250-DSN 250-ETRN 250-DELIVERBY 250 HELP

The E of the EHLO says that the local

sendmail speaks ESMTP too. The

remote machine replies with 250, then lists the ESMTP services that

it supports. All but the last reply line contain a dash

following the 250. That

dash signals that an additional reply line will follow. The

last line, the HELP line,

lacks a dash, and so completes the reply.

One problem that could occur is your machine sending a short

hostname (“here”) in the EHLO message. This would cause an error

because the remote machine wouldn’t find here in its domain

remote.domain.

This is one reason why it is important for your

sendmail to always use your

machine’s fully qualified hostname. A fully qualified name

is one that begins with the host’s name, followed by a dot,

then the entire DNS domain.

If all has gone well so far, the local machine sends the name of the sender of the mail message and the size of the message in bytes:

>>> MAIL From:<you@here.us.edu> SIZE=4537 250 2.1.0 <you@here.us.edu> ... Sender ok

Here, that sender address was accepted by the remote machine, and the size was not too large.

Next, the local machine sends the name of the recipient:

>>> RCPT To:<you@remote.domain> 250 2.1.5 <you@remote.domain> ... Recipient ok

If the user you were not

known on the remote machine, it might reply with an error of

“User unknown.” Here, the recipient is ok. Note that ok does not necessarily

mean that the address is good. It can still be bounced

later. The ok means only

that the address is acceptable.

After the envelope information has been sent, your sendmail attempts to send the mail message (header and body combined):

>>> DATA 354 Enter mail, end with "." on a line by itself >>> .

DATA tells the remote host

to “get ready.” The remote machine says to send the message,

and the local machine does so. (The message is not printed

as it is sent.) A dot on a line by itself is used to mark

the end of a mail message. This is a convention of the SMTP

protocol. Because mail messages can contain lines that begin

with dots as a valid part of the message,

sendmail doubles any dots at

the beginning of lines before they are sent.[20] For example, consider what happens when the

following text is sent through the mail:

My results matched yours at first: 126.71 126.72 ... 126.79 But then the numbers suddenly jumped high, looking like noise saturated the line.

To prevent any of these lines from being wrongly interpreted as the end of the mail message, sendmail inserts an extra dot at the beginning of any line that begins with a dot, so the actual text transferred is:

My results matched yours at first:

126.71

126.72

.... ← note extra dot

126.79

But then the numbers suddenly jumped high, looking like

noise saturated the line.The SMTP-server program running at the receiving end (for example, another sendmail) strips those extra dots when it receives the message.

The remote sendmail shows the queue identification number that it assigned to the mail it accepted:

250 2.0.0 d9L29Nj20475 Message accepted for delivery . . . >>> QUIT 221 remote.domain closing connection

The local sendmail sends QUIT to say it is all

done. The remote machine acknowledges by closing the

connection.

Note that the -v (verbose)

switch for sendmail is most useful with

mail sent to remote machines. It allows you to watch SMTP

conversations as they occur and can help in tracking down

why a mail message fails to reach its destination.

Debugging Mode (-d)

The sendmail program can also produce

debugging output. The

sendmail program is placed in

debugging mode by using the -d command-line switch. That switch

produces far more information than -v does. To see for yourself, enter the

following command line, but substitute your own login name

in place of the you:

%/usr/lib/sendmail -dyou< /dev/null

This command line produces a great deal of output. We won’t explain this output because it is explained in Chapter 15 on page 530. For now, just remember that the sendmail program’s debugging output can produce a great deal of information.

In addition to producing lots of debugging information, the

-d switch can be

modified to display specific debugging information. By

adding a numeric argument to the -d switch, output can be limited to one

specific aspect of the sendmail

program’s behavior.

Type in this command line, but change

you to your own login

name:

%/usr/lib/sendmail -d0you< /dev/null

Here, the -d0 is the

debugging switch with a category of 0. That category limits

sendmail’s program output to

information about how sendmail was

compiled. A detailed explanation of that output is covered

in -d0.4 on page 542.

In addition to a category, a level can

also be specified. The level adjusts the amount of output

produced. A low level produces little output; a high level

produces greater and more complex output. The string

following the -d has the

form:

category.level

For example, enter the following command line:

% /usr/lib/sendmail -d0.1 -bpThe -d0 instructs

sendmail to produce general

debugging information. The level .1 limits sendmail

to its minimal output. That level could have been omitted

because a level .1 is the

default. Recall that -bp

causes sendmail to print the contents

of its queue. The output produced looks something like the

following:

Version 8.14.1

Compiled with: LOG NAMED_BIND NDBM NETINET NETUNIX NIS SCANF

XDEBUG

== == == == == == SYSTEM IDENTITY (after readcf) == == == == == ==

(short domain name) $w = here

(canonical domain name) $j = here.us.edu

(subdomain name) $m = us.edu

(node name) $k = here

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == ==

/var/spool/mqueue is emptyHere, the -d0.1 switch

causes sendmail to print its version,

some information about how it was compiled, and how it

interpreted your host (domain) name. Now run the same

command line again, but change the level from .1 to .11:

% /usr/lib/sendmail -d0.11 -bpThe increase in the level causes sendmail to print more information:

Version 8.14.1

Compiled with: LOG NAMED_BIND NDBM NETINET NETUNIX NIS SCANF

XDEBUG

OS Defines: HASFLOCK HASGETUSERSHELL HASINITGROUPS HASLSTAT

HASSETREUID HASSETSID HASSETVBUF HASUNAME IDENTPROTO

IP_SRCROUTE

Config file: /etc/mail/sendmail.cf

Pid file: /etc/mail/sendmail.pid

canonical name: here.us.edu

UUCP nodename: here

a.k.a.: [123.45.67.89]

== == == == == == SYSTEM IDENTITY (after readcf) == == == == == ==

(short domain name) $w = here

(canonical domain name) $j = here.us.edu

(subdomain name) $m = us.edu

(node name) $k = here

== == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == ==

== == == == == ==

/var/spool/mqueue is emptyThe sendmail.cf File

The sendmail.cf file is read and parsed by sendmail every time sendmail starts. It contains information that is necessary for sendmail to run. It lists the locations of important files and specifies the default permissions for those files. It contains options that modify sendmail’s behavior. Most important, it contains rules and rule sets for rewriting addresses.

Configuration Commands

The sendmail.cf configuration file is line-oriented. A configuration command, composed of a single letter, begins each line:

V10/Berkeley ← good V10/Berkeley ← bad, does not begin a line V10/Berkeley Fw/etc/mail/mxhosts ← bad, two commands on one line Fw/etc/mail/mxhosts ← good

Each configuration command is followed by parameters that are

specific to it. For example, the V command is followed by an ASCII

representation of an integer value, a slash, and a vendor

name. Whereas the F

command is followed by a letter (a w in the example), then the full pathname

of a file. The complete list of configuration

commands[21] is shown in Table 1-4.

|

Command |

Description |

|

|

Define a class macro. |

|

|

Define a macro. |

|

|

Define an environment variable (beginning with V8.7). |

|

|

Define a class macro from a file, pipe, or database map. |

|

|

Define a header. |

|

|

Declare a keyed database (beginning with V8.1). |

|

|

Include extended load average support (contributed software, not covered). |

|

|

Define a mail delivery agent. |

|

|

Define an option. |

|

|

Define delivery priorities. |

|

|

Define a queue (beginning with V8.12). |

|

|

Define a rewriting rule. |

|

|

Declare a rule-set start. |

|

|

Declare trusted users (ignored in V8.1, restored in V8.7). |

|

|

Define configuration file version (beginning with V8.1). |

|

|

Define a mail filter (beginning with V8.12). |

Some commands, such as V,

should appear only once in your

sendmail.cf file. Others, such

as R, can appear

often.

Blank lines and lines that begin with the # character are considered

comments and are ignored. A line that begins with either a

tab or a space character is a continuation of the preceding

line:

# a comment

V10

/Berkeley ← continuation of V line above

↑ tabNote that anything other than a command, a blank line, a

space, a tab, or a #

character causes an error. If the

sendmail program finds such a

character, it prints the following warning, ignores that

line, and continues to read the configuration file:

/etc/mail/sendmail.cf: line 15: unknown configuration line "v9"

Here, sendmail found a line in its

sendmail.cf file that began

with the letter v.

Because a lowercase v is

not a legal command, sendmail printed a

warning. The line number in the warning is that of the line

in the sendmail.cf file that began with

the illegal character.

An example of each kind of command is illustrated in the following sections.

The version Command

To prevent older versions of sendmail

from breaking when reading new-style

sendmail.cf files, a V (for

version) command was introduced

beginning with V.1. The form for the version command looks

like this:

V10/Berkeley

The V must begin the line.

The version number that follows must be 10 to enable all the new

features of V.14 sendmail.cf. The

number 10 indicates that the syntax of the

sendmail.cf file has undergone

10 major changes over the years, the tenth being the current

and most recent. The meaning of each version is detailed in

The V Configuration Command on

page 580.

The Berkeley tells

sendmail that this is the pure

open source version. Other vendor names can appear here too.

Sun, for example,

would be listed on Sun Solaris platforms and would cause the

Sun Microsystems version of sendmail to

recognize the Sun configuration file extensions.

Comments

Comments help other people understand your configuration file.

They can also remind you about something you might have done

months ago and forgotten. They slow down

sendmail by only the tiniest

amount, so don’t be afraid to use them. As was mentioned

earlier, when the #

character begins a line in the

sendmail.cf file, that entire

line is treated as a comment and ignored. For example, the

entire following line is ignored by the

sendmail program:

# This is a comment

Besides beginning a line, comments can also follow commands.[22] That is:

V10/Berkeley # this is another comment

A Quick Tour

The other commands in a configuration file tend to be more complex than the version command you just saw (so complex, in fact, that whole chapters in this book are dedicated to most of them). Here, we present a quick tour of each command—just enough to give you the flavor of a configuration file but in small enough bites to be easily digested.

Mail delivery agents

Recall that the sendmail program

does not generally deliver mail itself. Instead, it

calls other programs to perform that delivery. The

M command

defines a mail delivery agent (a program that

delivers the mail). For example, as was previously

shown:

Mlocal, P=/usr/lib/mail.local, F=lsDFMAw5:/|@qPSXfmnz9,

S=EnvFromL/HdrFromL, R=EnvToL/HdrToL,

T=DNS/RFC822/SMTP,

A=mail.local -lThis tells sendmail that local mail is to be

delivered by using the

/usr/lib/mail.local program.

The other parameters in these lines are covered in

Chapter 20 on page 711.

Macros

The ability to define a value once and then use it in

many places makes maintaining your

sendmail.cf file easier. The

D

sendmail.cf command defines a

macro. A macro’s name is either a single letter or

curly-brace-enclosed multiple characters. It has

text as a value. Once defined, that text can be

referenced symbolically elsewhere:

DRmail.us.edu ← a single letter D{REMOTE}mail.us.edu ← multiple characters (beginning with V8.7)

Here, R and

{REMOTE} are

macro names that have the string mail.us.edu as their

values. Those values are accessed elsewhere in the

sendmail.cf file with

expressions such as $R and ${REMOTE}. Macros are covered in Chapter 21 on page 784.

Rules

At the heart of the sendmail.cf

file are sequences of rules that rewrite (transform)

mail addresses from one form to another. This is

necessary chiefly because addresses must conform to

many differing standards. The R command is used to

define a rewriting rule:

R$- $@ $1 @ $R user -> user @ remote

Mail addresses are compared to the rule on the left

($-). If they

match that rule, they are rewritten on the basis of

the rule on the right ($@

$1 @ $R). The text at the far right is a

comment (that doesn’t require a leading #).

Use of multicharacter macros and # comments (V8

configuration files and above) can make rules appear

a bit less cryptic:

R$- # If a plain username

$@ $1 @ ${REMOTE} # append "@" remote hostThe details of rules such as this are more fully explained in Chapter 18 on page 648.

Rule sets

Because rewriting can require several steps, rules are

organized into sets, which can be thought of as

subroutines. The S command begins a rule set:

S3

This particular S

command begins rule set 3. Beginning with V8.7

sendmail, rule sets can be

given symbolic names as well as numbers:

SHubset

This particular S

command begins a rule set named Hubset. Named rule sets

are automatically assigned numbers by

sendmail.

All the R commands

(rules) that follow an S command belong to that rule set. A

rule set ends when another S command appears to define another

rule set. Rule sets are covered in Chapter 19 on page 683.

Class macros

There are times when the single text value of a

D command

(macro definition) is not sufficient. Often, you

will want to define a macro to have multiple values

and view those values as elements in an array. The

C command

defines a class macro. A class macro is like an

array in that it can hold many items. The name of a

class is either a single letter or, beginning with

V8.7, a curly-brace-enclosed multicharacter

name:

CW localhost fontserver ← a single letter C{MY_NAMES} localhost fontserver ← multiple characters (beginning with V8.7)

Here, each class contains two items: localhost and fontserver. The value of

a class macro is accessed with an expression such as

$=W or $={MY_NAMES}. Class

macros are covered in Chapter 22 on page 854.

File class macros

To make administration easier, it is often convenient

to store long or volatile lists of values in a file.

The F

sendmail.cf command defines a

file class macro. It is just like the C command shown earlier,

except that the array values are taken from a

file:

FW/etc/mail/mynames

F{MY_NAMES}/etc/mail/mynames ← multiple characters (beginning with V8.7)Here, the file class macros W and {MY_NAMES} obtain their values from the

file

/etc/mail/mynames.

The file class macro can also take its list of values from the output of a program. That form looks like this:

FM|/bin/shownames

F{MY_NAMES}|/bin/shownames ← multiple characters (beginning with V8.7)Here, sendmail runs the program

/bin/shownames.

The output of that program is appended to the class

macro.

Beginning with V8.12, sendmail can also take its list of values from a database map. That form looks like this:

FM@ldap:-k (&(objectClass=virtHosts)(host=*)) -v host

F{MY_NAMES}@ldap:-k (&(objectClass=virtHosts)(host=*)) -v hostHere, sendmail gets the list of virtual domains it will manage from a Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) database.

File class macros are covered in Chapter 22 on page 854.

Options

Options tell the sendmail program many useful and necessary things. They specify the location of key files, set timeouts, and define how sendmail will act and how it will dispose of errors. They can be used to tune sendmail to meet your particular needs.

The O command is

used to set sendmail options.

An example of the option command looks like

this:

OQ/var/spool/mqueue

O QueueDirectory=/var/spool/mqueue ← beginning with V8.7Here, the Q option

(beginning with V8.7 called QueueDirectory) defines the name of the

directory in which mail will be queued as

/var/spool/mqueue.

Multicharacter option names, such as QueueDirectory, require

a space following the initial O to be recognized.

Options are covered in Chapter 24 on page 947.

Headers

Mail messages are composed of two parts: a header followed (after a blank line) by the body. The body can contain virtually anything.[23] The header, on the other hand, contains lines of information that must strictly conform to certain standards.

The H command is

used to specify which mail headers to include in a

mail message and how each will look:

HReceived: $?sfrom $s $.by $j ($v/$Z)$?r with $r$. id $i$?u for $u$.; $b

This particular H

command tells sendmail that a

Received:

header line must be added to the header of every

mail message. Headers are covered in Chapter 25 on page 1120.

Priority

Not all mail has the same priority. Mass mailings (to

a mailing list, for example) should be transmitted

after mail to individual users. The P command sets the

beginning priority for a mail message. That priority

is used to determine a message’s order when the mail

queue is processed:

Pjunk= −100

This particular P

command tells sendmail that

mail with a Precedence: header line of junk should be processed

last. Priority commands are covered in Chapter 25 on page 1120.

Trusted users

For some software (such as UUCP) to function

correctly, it must be able to tell

sendmail who a mail message

is from. This is necessary when that software runs

as a different user identity

(uid) than that specified in

the From: line in

the message header. The T

sendmail.cf command[24] lists those users that are

trusted to override the

From: address

in a mail message. All other users can have a

warning included in the mail message

header.[25]

Troot daemon uucp

This particular T

sendmail.cf command says that

there are three users who are to be considered

trusted. They are root (who is

a god under Unix), daemon

(sendmail usually runs as the

pseudouser daemon), and

uucp (necessary for UUCP

software to work properly).

Beginning with V8.10 sendmail, trusted users are also the only ones, other than root, permitted to rebuild the aliases database.

Trusted users are covered in Chapter 4 on page 154.

Keyed databases

Certain information, such as a list of UUCP hosts, is

better maintained outside of the

sendmail.cf file. External

databases (called keyed

databases) provide faster access to such

information. Keyed databases were introduced with

V8.1 and come in several forms, the nature and

location of which are declared with the K configuration

command:

Kuucp hash /etc/mail/uucphosts

This particular K

command declares a database with the symbolic name

uucp, with the

type hash,

located in /etc/mail/uucphosts.

The K command is

detailed and the types of databases are explained in

Chapter 23 on page 878.

Environment variables

The sendmail program is very

paranoid about security. One way to circumvent

security with root-run programs

such as sendmail is by running

them with bogus environment variables. To prevent

such an end run, V8 sendmail

erases all its environment variables when it starts.

It then presets the values for a small set of

variables (such as TZ and SYSTYPE). This small, safe

environment is then passed to its delivery agents.

Beginning with V8.7 sendmail,

sites that wish to augment this list can do so with

the E

configuration command:

EPOSTGRESHOME=/home/postgres

Here, the environment variable POSTGRESHOME is assigned the value /home/postgres.

This allows programs to use the

postgres(1) database to

access information. The E command is detailed in Chapter 4 on

page 154.

Queues defined

Beginning with V8.12, it is possible to both define a queue group and set its individual properties. Rule sets then select to which queue group a recipient’s message should belong.

To illustrate, consider a situation in which a great deal of your site’s mail goes to a host that is very busy during the day. You might prefer such mail, when it is deferred, to be retried only once every other hour. You could define such a site’s queue like this:

Qslowsite, P=/var/spool/mqueue/slowdir, I=2h

This configuration file line tells sendmail to place all mail bound for that site into the queue directory /var/spool/mqueue/slowdir and to process messages from that directory only once every 2 hours.

A rule elsewhere in the configuration file tells sendmail to associate any mail to anyone at slowsite.com with that queue group. Queue groups are described in detail in Queue Groups (V8.12 and Later) on page 408.

External filter programs

Beginning unofficially with V8.10, and officially with V8.12 sendmail, it is possible to filter all inbound messages through an external filter program. The default filter program is called milter(8), and is described in Create Milter Support on page 1170.

The X configuration

command (The X Configuration Command on page 1173) allows you to tune the way external

filters are used. In the following example, the

first filter tried will use the Unix socket

/var/run/f1.sock, and will

reject the message (the F=R) if the filter cannot be

accessed:

Xfilter1, S=local:/var/run/f1.sock, F=R

[4] * This is a professional MTA product, so like sendmail itself, it is, in a sense, a crossbar “switch.”

[5] * That path might be different on your system. If so, substitute the correct pathname in all the examples that follow. For example, try looking for sendmail in /usr/lib or /usr/ucblib.

[6] † We are fudging

for simplicity here. If the file contains a line

that contains only a single dot, that line will be

treated as though it marks the end of the file. If

you need to include such a line as part of literal

input, use the IgnoreDots options (IgnoreDots on page 1038).

[7] * We are fudging

for simplicity. The Message-ID: header is not strictly

mandatory.

[8] * Depending on how

the NoRecipientAction option was set, this

could be an Apparently-To: header, a Bcc: header, or even a

To: header