Chapter 13. Mailing Lists and ~/.forward

As was shown in the preceding chapter, the

sendmail program is able to obtain its

list of recipients from the aliases file. It

can also obtain lists of recipients from external files. In this

chapter, we will examine the two forms that those external files

take: the :include: form

(accessed from the aliases file) and the

individual user’s ~/.forward file. Because the

chief use of the :include: form

of alias is to create mailing lists, we will

first discuss mailing lists in general, then their creation and

management, and then the user’s ~/.forward

file.

A mailing list is the name of a single recipient[209] that, when expanded by sendmail aliasing, becomes a list of many recipients. Mailing lists can be internal (in which all recipients are listed in the aliases file), external (in which all recipients are listed in external files), or a combination of the two. The list of recipients that forms a mailing list can include users, programs, and files.

Internal Mailing Lists

An internal mailing list is simply an entry in the aliases file that has more than one recipient listed on the righthand side. Consider, for example, the following aliases file entries:

admin: bob,jim,phil bob: \bob,/u/bob/admin/maillog

Here, the name admin is

actually the name of a mailing list because it expands to

more than one recipient. Similarly, the name bob is a mailing list

because it expands to two recipients. Because bob is also included in

the admin list, mail sent

to that mailing list will be alias-expanded by

sendmail to produce the

following list of recipients:

jim, phil, \bob, /u/bob/admin/maillog

This causes the mail message to be delivered to the local

users jim and phil in the normal way.

That is, each undergoes additional alias processing, and the

~/.forward file of each is

examined to see whether either should be forwarded. The

recipient \bob, on the

other hand, is delivered without any further aliasing

because of the leading backslash. Finally, the message is

appended to the file

/u/bob/admin/maillog.

Internal mailing lists can become very complex as they strive to support the needs of large institutions. Examine the following simple, but revealing, example:

research: user1, user2 applications: user3, user4 admin: user5, user6 advertising: user7, user8 engineering: research, applications frontoffice: admin, advertising everyone: engineering, frontoffice

Only the first four aliases expand to real usernames. The last three form mailing lists out of combinations of those four, the last being a superset that includes all users.

When the number of mailing lists is small and they don’t change often, they can be effectively managed as part of the aliases file. But as their number and size grow, you should consider moving individual lists to external files.[210]

:include: Mailing Lists

The special notation :include: in the righthand side of an

alias causes sendmail to read its list

of recipients from an external file. For that directive to

be recognized as special, any address that begins with

:include: must

select the local delivery

agent and, beginning with V8.7, must have the F=: delivery-agent flag

set (F=: (colon) on page 765). This is automatic with most configuration

files, but if your configuration file does not automatically

recognize the :include:

directive, you will need to add a new rule near the end of

your parse rule set 0

(The parse Rule Set 0 on page

696). For example:

R :include: $* $@ $#local $: :include:$1

Beginning with V8.7 sendmail, any

delivery agent for which the F=: flag (F=: (colon)

on page 765) is set can also process :include: files. (Note

that eliminating the F=:

flag for all delivery agent definitions in your

configuration file will disable this feature

entirely.)

The :include: directive is

used in aliases(5) files like

this:

localname: :include:/pathThe expression :include: is

literal. It must appear exactly as shown, colons and all,

with no space between the colons and the “include.” As with

any righthand side of an alias, there can be space between

the alias colon and the lead colon of the :include:.

The /path is the full pathname of a

file containing a list of recipients. It follows the

:include: with

intervening space allowed.

The /path should be a full

pathname. If it is a relative name (such as

../file), it is relative to the

sendmail queue directory. For

all but V8 sendmail, the

/path must not be quoted. If it

is quoted, the quotation marks are interpreted as part of

the filename. For V8 sendmail, the

/path can be quoted, and

the quotation marks are automatically stripped.

If the /path cannot be opened for

reading for any reason, sendmail prints

the following warning and ignores any recipients that might

have been in the file:

include: open path: reasonHere, reason is “no such file or

directory,” “permission denied,” or something similar. If

/path exists and can be

read, sendmail reads it one line at a

time. Empty lines are ignored. Beginning with V8

sendmail, lines that begin with

a # character are also

ignored:

addr

# a comment

← empty line is ignored

addr2Each line in the :include:

file is treated as a list of one or more recipient

addresses. Where there is more than one, each should be

separated from the others by commas:

addr1 addr2, addr3, addr4

The addresses can themselves be aliases that appear to the

left in the aliases file. They can also

be user addresses, program names, or filenames. An :include: file can also

contain additional :include: lists:

engineers ← to an alias biff, bill@otherhost ← to two recipients |"/etc/local/loglists thislist" ← to a program alias /usr/local/archive/thislist.hist ← to a file :include:/yet/another/file ← from another file

Beginning with V8.7 sendmail, the

TimeOut.fileopen

option (Timeout.fileopen (V8.7 and later)

on page 1102) controls how long

sendmail should wait for the

open to complete. This is useful when files are remotely

mounted, as with NFS. This timeout encompasses both this

open and the security checks described next. Note that the

NFS filesystem must be soft-mounted (or mounted with the

intr option) for

this to work.

Beginning with V8, sendmail checks the file for security. If the controlling user is root, all components of the path leading to the file are also checked.[211] If the set-user-id bit of the file is set (telling sendmail to run as the owner of the file), sendmail checks to be sure that the file is writable only by the owner. If it is group- or world-writable, sendmail silently ignores that set-user-id bit. When checking components of the path, sendmail will print the following warning if it is running as root and if any component of the path is group- or world-writable:

WARNING: writable directory offending componentThis process is described in greater detail under the -d44 debugging switch

(-d44.4 on page 569), which can

also be used to observe this process.

After sendmail opens the

/path for reading, but

before it reads the file, it sets the controlling user to be

the owner of the file (if one is not already set, and

provided that file ownership cannot be given away with

chown(1)). The controlling user

provides the uid and

gid identities of the sender

when delivering mail from the queue (C line on page 447).

The :include: file can

neither deliver through programs nor append to files if any

of the following situations are true:

If the owner of the

:include: file has a shell that is not listed in /etc/shells (The /etc/shells File on page 180)If the

:include: file is group- or world-writable (see also theDontBlameSendmailoption, Don’t Blame sendmail on page 168)If the

:include: file is group-writable and theUnsafeGroupWritesoption (UnsafeGroupWrites on page 1114) is trueIf sendmail is not running as root because the

RunAsUseroption (RunAsUser on page 1083) has been defined (see also theDontBlameSendmailoption, Don’t Blame sendmail on page 168)

Comments in :include: Lists

IDA and V8 sendmail allow

comments in :include: files. Comment lines begin

with a #

character. If the # doesn’t begin the line, it is treated

as the beginning of an address, thus allowing valid

usernames that begin with a # (such as #1user) to appear first in a line by

prefixing them with a space:

# Management ← a comment frida george@wash.dc.gov # Staff ← a comment ben steve #1user ← an address

Note that because comments and empty lines are ignored by sendmail, they can be used to create attractive, well-documented mailing lists.

Under older versions of sendmail, comments can be emulated through the use of RFC-style comments:

( comment )

By surrounding the comment in parentheses, you cause

sendmail to view it (and the

parentheses) as an RFC-style comment and, thus, to

ignore it:

( Management ) frida george@wash.dc.gov ( Staff ) ben steve

This form of comment works with both the old and new sendmail programs.

Trade-offs

As has been noted, the aliases

file should be writable only by

root for security reasons.

Therefore, ordinary users, such as nonprivileged

department heads, cannot use the

aliases file to create and

manage mailing lists. Fortunately, :include: files allow

ordinary users (or groups of users) to maintain

mailing lists. This offloads a great deal of work

from the system administrator, who would otherwise

have to manage these lists, and gives users a sense

of participation in the system.

In some circumstances, reading :include: lists can be

slower than reading entries from an

aliases database. At busy

sites or sites with numerous mail messages addressed

to mailing lists, this difference in speed can

become significant. Note that the -bv command-line switch

(-bv on page 237) can be used

with sendmail to time and

contrast the two different forms of lists. On the

other hand, rebuilding the

aliases(5) database can

sometimes be very slow. In such instances, the

:include: file

can be faster because it doesn’t require a rebuild

each time it changes.

One possible common disadvantage to all types of mailing lists is that they are visible to the outside world. This means that anyone in the world can send mail to a local list that is intended for internal use. Many lists are intended for both internal and external use. One such list might be one for discussion of the O’Reilly Nutshell Handbooks, called, say, nuts@oreilly.com. Anyone inside oreilly.com and anyone in the outside world can send mail messages to this list, and those messages will be forwarded to everyone on the nuts mailing list.

It is possible to protect your internal lists from use by outsiders, but doing so requires writing custom rules. For possible rules you might be able to adapt for your site’s needs, see http://www.sendmail.org/~ca/email/examples/internal.aliases.html.

Defining a Mailing List Owner

Notification of an error in delivery to a mailing list is sent to the original sender as bounced mail. Although this behavior is desirable for most mail delivery, it can have undesirable results for mailing lists. Because the list is maintained locally, it does not make sense for an error message to be sent to a remote sender. That sender is likely to be puzzled or upset and unable to fix the problem. A better solution is to force all error messages to be sent to a local user, regardless of who sent the original message.

When sendmail processes errors during

delivery, it looks to see whether an “owner” was defined for

the mailing list. If one was defined, errors are sent to

that owner rather than to the sender. The owner is defined

by prefixing the original mailing list alias with the phrase

owner-, as shown

in the following aliases file fragment:

nuts: :include:/home/lists/nuts.list owner-nuts: george

Here, nuts is the name of

the mailing list. If an error occurs in attempting delivery

to the list of recipients in the file /home/lists/book.list,

sendmail looks for an alias

called owner-nuts (the

original name prefixed with owner-). If sendmail

finds an owner (here, george), it sends error notification to

that owner rather than to the original sender. Generally, it

is best to have the owner- of a list be the same as the owner

of the mailing-list file, because that user is best suited

to correct errors as they appear.

To ensure that all errors in mailing lists are handled by someone, an owner of owners should also be defined. That alias usually looks like this:

owner-owner: postmaster

If sendmail cannot deliver an error

message to the owner- of

a mailing list, it instead delivers it to the owner-owner.

Beginning with V8 sendmail, a single

alias expansion is done on the owner- of any :include: list, and that expansion is

made the address of the envelope sender:

nuts: :include:/home/lists/nuts.list owner-nuts: nuts-request nuts-request: george

Here, with V8 sendmail, the envelope

sender for mail sent to nuts will be nuts-request (a single-level alias

expansion), rather than george (a multiple-level alias

expansion).

As a side effect, with V8 sendmail, mail

sent to owner-anything

will have the envelope-sender address set to a single alias

expansion of owner-owner.

This can be confusing, so always stress to users that they

should mail the maintainer of a list with the -request suffix instead of

the owner- prefix.

Exploder Mailing Lists

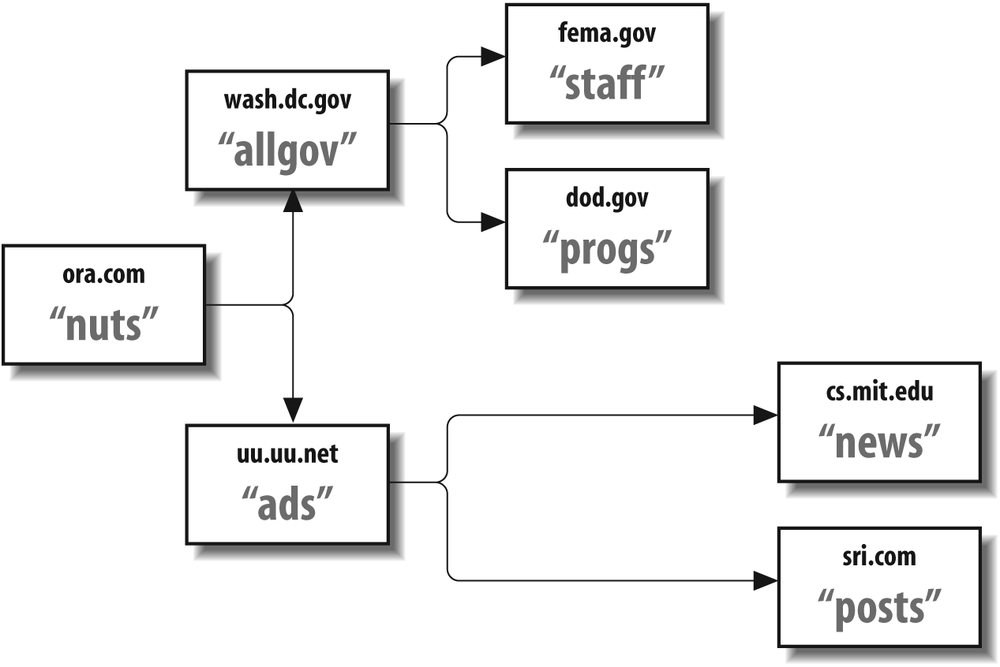

When mailing lists get extremely large, they sometimes include the names of other lists at other sites as recipients. Those other lists are called exploder lists because they cause the size of a list (the number of recipients) to explode. For example, consider the situation in Figure 13-1.

This figure shows that a message sent to nuts@ora.com will, in addition to its list of users, also be forwarded to allgov@wash.dc.gov and ads@uu.uu.net. But each recipient is also a mailing list. Like the original nuts list, they deliver to ordinary users and forward to other sites’ mailing lists.

Unless exploding lists such as this are correctly managed, problems that are both mysterious and difficult to solve can arise. A bad address in one of the distant exploding lists, for example, can cause a delivery error at a remote exploder site. If this happens, it is possible that the error notification will be sent to either the original list maintainer or (worse) the original submitter, although neither is in a position to correct such errors.

To ensure that error notification is sent to the person who is best able to handle the error, mailing list entries in the aliases file should be set up like the following. It is an approach well suited for exploder sites.

list: :include:/path/to/rebroadcast.list list-request: list-request@original.site, local maintainer's address here owner-list: local maintainer's address here

Here, list is the name of

the mailing list that explodes mail by sending the incoming

message to the users listed in

rebroadcast.list. Note that the

envelope of the outgoing message will contain the address of

a local user, one able to fix problems in

rebroadcast.list. Messages to

list-request will be relayed to

both list-request@original.site and a

local user, thus delivering administrative mail to the

originating list maintainer and to the local maintainer, one

of whom should be able to handle the request.

Problems with Mailing Lists

At small sites that just use mailing lists internally, the problems are few and can be easily solved locally. But as lists get to be large (more than a few hundred recipients), many (more than 50 lists), or complex (using exploders), problems become harder to localize and more difficult to solve. In the following discussion, we present the most common problems. It is by no means comprehensive, but it should provide information to solve most problems.

Reply Versus Bounce

The eventual recipient of a mailing-list message

should be able to reply to the message and have that

reply go to either the original sender or the list

as a whole. Which of these happens is an

administrative decision. In general, replies go to

the address listed in the From: or Reply-To: header. If the intention is

to have replies go to the list as a whole, these

headers need to be rewritten by a filter at the

originating site:

list: "|/etc/local/mailfilter list -oi -odq -flist-request list-real"

Here, the name of the filter has replaced sendmail in the aliases file entry. Writing such a filter is complex. The original addresses need to be preserved with appropriate headers before they are rewritten by the filter.

The converse problem is that not all mail-handling

programs handle replies properly. Some programs,

such as UUCP and certain versions of

emacs-mail, insist on

replying to the envelope sender as conveyed in the

five-character "From" header. By setting up lists

correctly (as we showed earlier), an administrator

can at least guarantee that those replies are sent

to the list maintainer, who can then forward them as

required.

A more serious problem is the way other sites handle

bounced mail. In an ideal world, all sites would

correctly bounce mail to the envelope sender and

(less desirably) to the Errors-To: address, which, beginning

with V8.8, is supported only if the UseErrorsTo option

(UseErrorsTo on page 1115) is

set to true.[212] Unfortunately, not all sites are so well

behaved. If a mailing list is not carefully set up,

there is a possibility that bounced mail will be

re-sent to the list as a whole. To minimize such

potential catastrophes, follow the guide in Table 13-1.

|

Header |

§ |

Use |

|

Envelope sender |

$f on page 824 |

Should be local list maintainer |

|

|

SaveFromLine on page 1085 |

Same as envelope sender |

|

|

From: on page 1157 |

Original submitter |

|

|

Reply-To: on page 1164 |

Local list maintainer, list as a whole, or original submitter |

|

|

Errors-To: on page 1156 |

If present, the local list maintainer |

Gateway Lists to News

When gatewaying a mailing list to Usenet news, the

inews(1) program bounces the

message if it is for a moderated group and lacks an

Approved:

header, which can be added by a filter program

(Write a Delivery Agent Script

on page 470) or by a news gateway delivery

agent.

If your site is running (or has access to) Usenet

news, the recnews(1) program

that is included therein can be used to gateway mail

to newsgroups. It inserts the Approved: header that

inews needs and generally

handles its gateway role well. One minor pitfall to

avoid with recnews is making

separate postings when you intend

cross-postings:

mail-news: "|/usr/local/recnews comp.mail comp.mail.d" ← separate postings mail-news: "|/usr/local/recnews comp.mail,comp.mail.d" ← cross-posted ↑ note the comma

A List-Bounced Alias

There are many ways to handle bounced mail in managing a mailing list. One of the best ways for large lists is to create a bounce alias for a list:

list-bounce: :include:/usr/local/lists/list-bounce

When an address in the main list begins to bounce, move it from the main list’s file to the corresponding list-bounce file. Then send a message to that list nightly (via cron(8)), advising the users in it that they will soon be dropped. To prevent the bad addresses from deluging you with bounced mail, set up the return address and the envelope to be an alias that delivers to /dev/null:

black-hole: /dev/null

Finally, arrange to include the following header in the outgoing message:

Precedence: junk

This prevents most sites from returning the message if it cannot be delivered.

Programs are available that can help to manage large and numerous mailing lists. We will cover them later in this chapter.

Users Ignore list-request

It is impossible to cause all users to interact properly with a mailing list. For example, all submissions to a list should (strictly speaking) be mailed to list, whereas communications to the list maintainer should be mailed to list-request. As a list maintainer, you will find that users mistakenly reverse these roles surprisingly often.

One possible cure is to insert instructions in each

mailing at the start of the message. In the header,

for example, Comment: lines can be used like

this:

Comment: "listname" INSTRUCTIONS Comment: To be added to, removed from, or have your address changed Comment: in this list, send mail to "listname-request".

Unfortunately, user inattention usually dooms such schemes to failure. You can put instructions everywhere, but some users will still send their requests to the wrong address.

A solution some sites use when the list is used only for official and rare mailings is to install the list name in the aliases file just before the mailing:

list: :include: /usr/local/lists/official.list ← beforeThen run newaliases(1) and send mail to the list. After all the mail for the list has been queued, edit the aliases file, comment out that entry, and create a new one:

#list: :include: /usr/local/lists/official.list ← after

list: owner-listRun newaliases(1) again, and you will have disabled that list. That way, mail that is wrongly sent to list will be received only by the list’s owner (who can notify the sender of the error) instead of wrongly being broadcast to the list as a whole.

Precedence: bulk

All mass mailings, such as mailing-list mailings,

should have a header Precedence: line that gives a priority

of bulk, junk, or list. On the local

machine, these priorities cause the message to be

processed from the queue after higher-priority mail.

At other sites, these priorities will cause

well-designed programs (such as the newer

vacation(1)[213] program) to skip automatically replying

to such messages.

X.400 Addresses

The X.400 telecommunications standard is finding some

acceptance in Europe and by the U.S. government.

Addresses under X.400 always begin with a leading

slash, which can cause sendmail

to think that the address is the name of a file when

the local

delivery agent is selected:

/PN=MS.USER/O=CORP/PRMD=CORP/ADMD=TELE/C=US/

To prevent this misunderstanding, all such addresses should be followed by an @domain part to route the message to an appropriate X.400 gateway:

/PN=MS.USER/O=CORP/PRMD=CORP/ADMD=TELE/C=US/@X.400.gateway.here

Mail List Etiquette

Managing your own mailing lists can become tricky, especially in light of the recent explosion of spam email and the effort and cost of fighting it. In this section, we cover positive behaviors associated with mailing lists that will help you avoid being labeled a spam emailer:

Clearly indicate subscription and management information.

Keep messages small.

Don’t use the

To:orCc:headers to create lists.Let software do the job for you.

Boot members who send spam email.

Before we begin, however, we need to mention the difference between an “open list” and “closed list.” An open list is one that allows anyone interested in it to subscribe through some (usually) automatic process. A closed list is one intended for subscribers only, and is usually tied to some controlled membership mechanism.

In this section, we chiefly discuss open lists, although the lessons taught can often apply equally to closed lists. Problems that can affect open lists include:

The subscriber’s interest has flagged or the original reason for joining no longer applies.

The subscriber left a workstation unguarded and a jokester subscribed that subscriber.

The subscriber abandoned the email address and someone else inherited it.

The subscriber moved, and the old address could not be forwarded.

Similarly, it is important that the manager of the list is easy to contact, because that person is the only one who can fix a number of common problems:

Someone on the list sent a spam email and must be removed from the list.

The mechanism used to unsubscribe is broken.

A member is receiving duplicate messages or omissions.

In general, there are only two places in a message that can contain such information: the message headers and the message body.

Some mailing list software inserts the information into custom

X- headers on

your behalf. For example:

X-Unsubscribe: remove@mailing.list.domain X-Owner: list-request@mailing.list.domain

Others arrange for standard headers to work. For example:

From: list-request@mailing.list.domain

Offer Subscription and Management Information

Each mailing to a list should contain clear information describing how a subscriber may be removed from the list and to whom to send questions or complaints.

As we illustrated earlier, some mailing list software

inserts the information into custom X- headers on your

behalf. For example:

X-Unsubscribe: remove@mailing.list.domain X-Owner: list-request@mailing.list.domain

Others arrange for standard headers to work. For example:

From: list-request@mailing.list.domain

Here, merely replying to this message will get the

subscriber’s comments delivered directly to the list

administrator (see RFC2142 Common Mailbox Names on page

474 for a -request suffix discussion).

Other mailing list software appends a standard footer to the body of every message. For example:

This list is brought to you by the power of mailing.list.domain. To unsubscribe visit http://www.mailing.list.domain/unsubscribe or send email to unsubscribe@mailing.list.domain. To report abuse or problems, send email to abuse@mailing.list.domain. In the event email fails you may also telephone +1-800-555-1234 or send surface mail to MailingList, Inc. P.O. Box 555, City, CA 12345

This footer solves most of a mailing list’s needs. It allows the recipient to unsubscribe either via a web site or by sending email to a clearly indicated email address. It also indicates to whom to send complaints and reports of problems. It is vital (and required) that if you send email from your site, you maintain an alias for the user named abuse, which causes mail for that name to be delivered to an actual person. Note that if email fails, there is a telephone number and surface mail address to fall back on.

We recommend that you adopt as many of these

techniques as you can. A recipient should be able to

communicate with the administrator of the list by

simply sending a message to the name of the list

suffixed with a -request. Also, information about

unsubscribing should be placed in clear text in the

body of every message.

Keep Messages Small

Many businesses routinely reject messages that contain attachments, or accept them and silently strip attachments. Mailing list management should adopt a similar sort of strategy when accepting messages that will be broadcast to subscribers. To protect the recipients of the mailing list, either reject submissions that contain attachments or silently remove attachments (perhaps with an indication of that removal placed in the body of the message).

The method for rejecting or removing attachments varies depending on the type of mailing list software you use, and therefore, we must leave the discovery of that method up to you.

Some lists discuss matters that, by their very nature, require readers to view or hear examples. When administrating lists that discuss images or sounds, for example, try to encourage list members to send web references instead of embedding the images or sounds directly into each message. The following lines illustrate one appropriate technique:

I put my latest 3D images up for you to see at http://www.my.domain/3d/bob/newimages. Let me know if you like them.

Here, a half kilobyte message distributes images vastly more efficiently than would a potentially two or three megabyte message that embedded the images directly inside itself. Because of that efficiency, use of references is kinder to ISP machines, and reduces the risk that the images will be removed or email rejected because they have attachments.

Don’t Pack Addresses in Headers

Hands down, the most offensive way to email a message

to a mailing list is by placing all the recipients

into a To: or

CC: header or

both. Not only will this likely mark you as a

spammer, but it also risks that your site will

become listed at one or more blacklisting

sites.

Never send mail to a mailing list like this:

To: list-owner@mailing.list.domain

Cc: bob@a.domain, ben@another.domain, bill@yet.another.domain,

carrie@somewhere.gov, jose@there.domain, ...

etc. for hundreds of addressesThere are two serious problems with this approach. First, it reveals all the members of the list to every recipient on the list. This violates the privacy of each recipient on the list. Most who join an organization, or mailing list, expect that their membership will be private and not advertised to others.

Second, messages with too many header recipients (typically more than 25 or so) are consider spam email by many sites. Mailing list messages are not spam email and therefore should never appear to be.

See Internal Mailing Lists on page 485 to learn the correct way to set up mailing lists using sendmail.

Let Software Do the Job for You

As mailing lists become large, or emailings to them become frequent, lists eventually need to be moved from self-serviced lists to fully automated lists. Three classes of software are available for this transition. Open source software for Unix is mature and well written. Commercial software for Unix and Windows is widely available. Commercial services (some free with advertising included in each message) are also available.

See Packages That Help on page 499 for a discussion of several available packages.

Maintain a Clear Policy

Each subscriber that joins your mailing list should be made aware of your list’s policies from the beginning. One common method of distributing policy to subscribers is to include it in the initial greeting sent to a new subscriber. Another common method is to post it on a web site. Naturally, we encourage you to do both.

The mailing list shall not be used to send unsolicited commercial email (spam email) to its members.

Mailings to the list shall remain on-topic and of general interest to the list as a whole.

Members shall not engage in name calling, anger, or offensive language. Members shall not post messages to the list that could be construed as defamatory, libellous, or offensive to individuals, organizations, or institutions.

Mailings to members of the list shall be sent directly to each, rather than broadcast to the list as a whole.

Members who violate these policies shall be removed from the list.

Subscribers whose addresses continue to bounce for more than a week shall be removed from the list.

Boot Off Offending Members

As the administrator of a mailing list, it is your job to police that list. Anytime a subscriber sends an offensive or spam email message to the list, you should immediately contact that subscriber and take corrective action. Many administrators will immediately unsubscribe the offender. Some administrators must find other solutions, because members may have to pay to subscribe.

Find out what your rights are as an administrator before you accept the job or before you set up the mailing list. Make certain you can remove offending subscribers in a timely manner to protect the remainder of your subscriber base.

As a courtesy to your remaining subscribers, you should let them know that you handled a certain problem and that the offending subscriber won’t post to the list again.

Packages That Help

As the number and size of mailing lists at your site become large, you might wish to install a software package that automates list management. We show four of the more mature packages here. Many other packages exist (some good, many immature), and you can find them by searching the Web.

Majordomo

The Majordomo mailing-list management software was originally written by Brent Chapman using the perl(1) language. Its chief features are that it allows users to subscribe to and remove themselves from lists without list manager intervention and that it allows list managers to manage lists remotely. In addition, users can obtain help and list descriptions with simple mail requests. Note that Majordomo aids in managing a list (the list addresses) but does not aid in list moderation (the contents of mail messages). But Majordomo does catch administrative mail erroneously sent to the list as whole. Majordomo is available from http://www.greatcircle.com/majordomo/.

Mailman

The Mailman mailing-list management software was written and is distributed as part of the GNU project. It claims to be fully web-based for ease of management. Even list managers can manage lists entirely over the Web. Mailman is written in Python (with a little additional C code for better security). The Mailman package is available from http://www.gnu.org/software/mailman/.

ListProcessor

The ListProcessor system was written by Tasos Kotsikonas. It is an automated system for managing mailing lists that replaces the aliases file for that use. According to the author, it includes support for “public and private hierarchical archives, moderated lists, peer lists, peer servers, private lists, address aliasing, news connections and gateways, mail queueing, list ownership, owner preferences, crash recovery, and batch processing.” The system also accepts Internet connections for “live” processing of requests at port 372 (as assigned by the IANA).[214] The ListProcessor system is available from http://www.listserv.net/.

ListManager

According to its author, Murray S. Kucherawy, the ListManager system “is written entirely in C, so it’s faster and more efficient than mailing list systems based on scripted languages. Rather than flat files, it uses fast B-tree databases courtesy of Sleepycat Software for faster performance.” This is the mailing list software used by sendmail.org. Among the features claimed on its web site are:

Automatic mail-alias table updates

Moderated, private, invite-only, and “hidden” lists

List archiving, with access controls and lifetime limits

Subscription confirmation, new subscriber probation, and subscriber renewals

Address validation check levels: none, syntax only, MX, and SMTP

HTTP interface and extensive help

Password security on subscriptions and list modifications

Arbitrary file storage, and Unix mailbox-format archives

MIME attachment filtering and loop detection

Automatic subscriber addition features

Quotation limiting, access control lists, digest sorting, and list inclusions

Subscriber domain matching

Rotating footers, and separate headers and footers for digests

Crontab-like digest distribution settings

Distribution of digests by size, time, or number of submissions

Welcome and farewell messages

Domain masquerading

Powerful command-line features such as “foreach” and scripting

The Listmanager software is available at http://www.listmanager.org/.

The User’s ~/.forward File

The sendmail program allows each user to

have an :include:-style

list to customize the receipt of personal mail. That file

(actually a possible sequence of files) is defined by the

ForwardPath

option (ForwardPath on page 1034).

Traditionally, that file is located in a user’s home

directory.[215] We use the C-shell notation ~ to indicate user home

directories, so we will compactly refer to this file as

~/.forward.

If a recipient address selects a delivery agent with the

F=w flag set

(F=w on page 781), that

address is considered the address of a local user whose

~/.forward file can be

processed. If the user part of that address contains a

backslash, sendmail disallows further

processing, and the message is handed to the local delivery agent’s

P= program for

delivery to the mail-spooling directory. If a backslash is

absent, sendmail tries to read that

user’s ~/.forward file.

If all the .forward files listed in the

ForwardPath

option (ForwardPath on page 1034) cannot

be read, their absence is silently ignored. This is how

sendmail behaves when those

files don’t exist. Users often choose not to have

~/.forward files. But problems

can arise when users’ home directories are remotely mounted.

If the user’s home directory is temporarily absent (as it

would be if an NFS server is down), or if a user has no home

directory, sendmail syslog(3)s the

following error message and falls back to the other

directories in its ForwardPath option:

forward: no home

If there are no further directories to fall back to, the missing home is considered a temporary error, and the message is queued for a later delivery attempt.

V8 sendmail temporarily transforms itself into the user[216] before trying to read the ~/.forward file. This is done so that reads will work across NFS. If sendmail cannot read the ~/.forward file (because it is not allowed to), it silently ignores that file.

Before reading the ~/.forward file, sendmail checks to see whether it is a “safe” file—one that is owned by the user or root, has the read permission bit set for the owner, and is writable only by root or the owner. If the ~/.forward file is not safe, sendmail logs a warning and ignores the file.

If sendmail can find and read the

~/.forward file and if that

file is safe, sendmail opens the file

for reading and gathers a list of recipients from it.

Internally, the ~/.forward file is

exactly the same as an :include: file. Each line of text in it

can contain one or more recipient addresses. Recipient

addresses can be email addresses, the names of files onto

which the message should be appended, the names of programs

through which to pipe the message, or :include: files.

Beginning with V8 sendmail,

~/.forward files can contain

comments (lines that begin with a # character). Other versions of

sendmail treat comment lines as

addresses and bounce mail that is seemingly addressed to

#.

Unscrambling Forwards

The traditional use of the

~/.forward file, as its name

implies, is to forward mail to another site.

Unfortunately, as users move from machine to

machine, they can leave behind a series of

~/.forward files, each of

which points to the next machine in a chain. As

machine names change and as old machines are

retired, the links in this chain can be broken. One

common consequence is a bounced mail message (“host

unknown”) with a dozen or so Received: (Received: on page 1162) header

lines.

As the mail administrator, you should beware of the ~/.forward files of users at your site. If any contain offsite addresses, you should periodically use the SMTP expn command[217] to examine them. For example, consider a local user whose ~/.forward contains the following line:

user@remote.domain

This causes all local mail for the user to be

forwarded to the host remote.domain for delivery there. The

validity of that address can be checked with

nslookup and

telnet(1) at port 25[218] and the SMTP expn command:

%ns -q=mx remote.domainAddress: 123.45.67.89 remote.domain preference = 0, mail exchanger = mail.remote.domain remote.domain preference = 10, mail exchanger = mx.another.domain %telnet mail.remote.domain 25Trying 123.45.123.45 ... Connected to mail.remote.domain. Escape character is '^]'. 220 mail.remote.domain Sendmail 8.14.1/8.14.1 ready at Thu, 13 Dec 2007 09:48:09 −0600 (MDT) 220 ESMTP spoken hereexpn user250 <user@another.site>quit221 remote.domain closing connection Connection closed by foreign host. %

This shows that the user is known at remote.site but also

shows that mail will be forwarded (yet again) from

there to another.site. By repeating this

process, you will eventually find the site at which

the user’s mail will be delivered. Depending on your

site’s policies, you can either correct the user’s

~/.forward file or have the

user correct it. It should contain the address of

the host where that user’s mail will ultimately be

delivered.

But beware that the world of email is becoming less friendly for the well-intentioned administrator. Because EXPN can be used to harvest addresses for spam lists, it is more and more frequently turned off. If you connect to a site with EXPN turned off, you will see an error such as the following, instead of the forwarding address you need:

502 5.7.0 Sorry, we do not allow this operation

If EXPN fails, try finger(1) in its place, which also might fail (another illustration of the harm caused by spam email).

Forwarding Loops

Because ~/.forward files are under user control, the administrator occasionally needs to break loops caused by improper use of those files. To illustrate, consider a user who wishes to have mail delivered on two different machines (call them machines A and B). On machine A, the user creates a ~/.forward file such as this:

\user, user@B

Then, on machine B, the user creates this ~/.forward file:

\user, user@A

The intention is that the backslashed name (\user) will cause local

delivery and the second address in each will forward

a copy of the message to the other machine.

Unfortunately, this causes mail to go back and forth

between the two machines (delivering and forwarding

at each) until the mail is finally bounced with the

error message “too many hops.”

On the machine that the administrator controls, a fix to this looping is to temporarily edit the aliases database and insert an alias for the offending user, such as this:

user: \user

This causes mail for user to be delivered locally and that

user’s ~/.forward file to be

ignored. After the user has corrected the offending

~/.forward files, this alias

can be removed.

Appending to Files

The ~/.forward file can contain the names of files onto which mail is to be appended. Such filenames must begin with a slash character that cannot be quoted. For example, if a user wishes to keep a backup copy of incoming mail:

\user /home/user/mail/in.backup

the first line (\user) tells

sendmail to deliver directly

to the user’s mail spool file using the local delivery agent.

The second line tells sendmail

to append a copy of the mail message to the file

specified (in.backup).

Note that prior to V8, sendmail did no file locking, so writing files by way of the ~/.forward file was not recommended. Beginning with V8, however, sendmail locks those files during writing, so such use of the ~/.forward file is now OK.

If the SafeFileEnvironment option (SafeFileEnvironment on page 1084) is

set, the user should be advised to specify the path

of that safe directory:

\user /arch/bob.backup ← here /arch was specified by the SafeFileEnvironment option

When the SafeFileEnvironment option is used, the

cooperation of the system administrator might be

needed if users are to have the ability to save mail

to files via the ~/.forward

file.

Piping Through Programs

The ~/.forward file can contain

the names of programs to run. A program name is

indicated by a leading pipe (|) character, which

might or might not be quoted (Delivery Via Programs on page 468).

For example, a user might be away on a trip and want

mail to be handled by the

vacation(1) program:

\user, "|/usr/ucb/vacation user"

Recall that prefixing a local address with a backslash

tells sendmail to skip

additional alias transformations. For \user, this causes

sendmail to deliver the

message (via the local delivery agent) directly to the

user’s spool mailbox.

The quotes around the vacation

program are necessary to prevent the program and its

single argument (user) from being viewed as two separate

addresses. The vacation program

is run with the command-line argument user, and the mail

message is given to it via its standard

input.

Beginning with V8 sendmail, a user must have a valid shell to run programs from the ~/.forward file and to write files via the ~/.forward file. See The /etc/shells File on page 180 for a description of this process and for methods to circumvent it at the system level.

Because sendmail sorts all addresses and deletes duplicates before delivering to any of them, it is important that programs in ~/.forward files be unique. Consider a program that doesn’t take an argument and suppose that two users both specified that program in their ~/.forward files:

user 1 → \user1, "|/bin/notify" user 2 → \user2, "|/bin/notify"

Prior to V8 sendmail, when mail

was sent to both user1 and user2, the address /bin/notify appeared

twice in the list of addresses. The

sendmail program eliminated

what seems to be a duplicate,[219] and one of the two users did not have

the program run.

If a program requires no arguments (as opposed to ignoring them), the ~/.forward program specifications can be made unique by including a shell comment:

user 1 → \user1, "|/bin/notify #user1" user 2 → \user2, "|/bin/notify #user2"

Specialty Programs for Use with ~/.forward

Rather than expecting users to write home-grown programs for use in ~/.forward files, offer them any or all of the publicly available alternatives. The most common are listed in the following sections.

The procmail program

The procmail(1) program,

originally written by Stephen R. van den Berg and

currently maintained by Philip Guenther, is

purported to be the most reliable of the delivery

programs. It can sort incoming mail into separate

folders and files, run programs, preprocess mail

(filtering out unwanted mail), and selectively

forward mail elsewhere. It can function as a

substitute for the local delivery agent or handle mail

delivery for the individual user. The

procmail program (as

recommended in its manual) is typically used in

the ~/.forward file like

this:

"|exec /usr/local/bin/procmail #user"

Note that procmail does not accept a username as a command-line argument. Because of this, a dummy shell comment is needed for pre-V8 versions of sendmail to make the address unique. The procmail program is available from the site http://www.procmail.org/.

The slocal program

The slocal program, distributed with the mh distribution, is useful for sorting incoming mail into separate files and folders. It can be used with both Unix-style mail files and mh-style mail directory folders. The slocal program (as recommended in its manual) is typically used in the ~/.forward file like this:

"| /usr/local/lib/mh/slocal -user user"

The disposition of mail is controlled using a companion file called ~/.maildelivery.

Force Requeue on Error

Normally, a program in the user’s ~/.forward file is executed with the Bourne shell:

Mprog, P=/bin/sh, F=lsDFMeuP, S=10, R=20, A=sh -c $u

↑

the Bourne shellOne drawback to using the Bourne shell to run programs is that it exits with a value of 1 when the program cannot be executed. When sendmail sees the exit value 1, it bounces the mail message.

There will be times when bouncing a mail message because the program could not execute is not desirable. For example, consider the following ~/.forward file:

"| /usr/local/lib/slocal -user george"

If the directory /usr/local/lib is unavailable (perhaps because a file server is down or because an automounter failed), the mail message should be queued rather than bounced. To arrange for requeuing of the message on failure, users should be encouraged to construct their ~/.forward files like this:

"| /usr/local/lib/slocal -user george || exit 75"

Here, the || tells

the Bourne shell to perform what follows (the

exit 75) if the

preceding program could not be executed or if the

program exited because of an error. The exit value

75 is special, in that it tells

sendmail to queue the message

for later delivery rather than to bounce it.

Pitfalls

When sendmail collects addresses, it discards duplicates. Prior to V8 sendmail, program entries in a ~/.forward file had to be unique; otherwise, an identical entry in another user’s ~/.forward caused one or the other to be ignored. Usually, this is solved by requiring the program to take an argument. If the program won’t accept an argument, add a shell comment inside the quotes.

The database forms of the aliases(5) file contain binary integers. As a consequence, those database files cannot be shared via network-mounted filesystems by machines of differing architectures. This has been fixed with V8 sendmail, which can use the Sleepycat db(3) form of database—if you define NEWDB (NEWDB on page 128) when building sendmail.

As network-mounted filesystems become increasingly common, the likelihood that a user’s home directory will be temporarily unavailable increases. Prior to V8 sendmail, this problem was not handled well. Instead of queueing mail until a user’s home directory could be accessed, sendmail wrongly assumed that the ~/.forward didn’t exist. This caused mail to be delivered locally when it should have been forwarded to another site. This can be fixed by using the

ForwardPathoption (ForwardPath on page 1034) of V8 sendmail.Prior to V8 sendmail, there was no way to disable user forwarding via ~/.forward files. At sites with proprietary or confidential information, there was no simple way to prevent local users from arbitrarily forwarding confidential mail offsite. But ~/.forward files can be centrally administered by using the

ForwardPathoption (ForwardPath on page 1034) of V8 sendmail, even to the point of completely disabling forwarding with:define(`confFORWARD_PATH', `')

Programs run from ~/.forward files should take care to clear or reset all untrusted environment variables. Only V8 properly presets the environment.

If a user’s ~/.forward file evaluates to an empty address, the mail will be silently discarded. This has been fixed in IDA and V8 sendmail.

A program run from a ~/.forward file is always run on the machine running sendmail. That machine is not necessarily the same as the machine housing the ~/.forward file. When user home directories are network-mounted, it is possible that one machine might support the program (such as /usr/ucb/vacation), while another might lack the program or call it something else (such as /usr/bsd/vacation). Also, if the program lives under the user’s home, it might not be compiled correctly to run on the server. Note that if smrsh (Configure to Use smrsh on page 380) is used, the path is ignored.

[209] * RFC defines a mailing list as a pseudouser’s address that expands to multiple real email addresses. As you will see when we cover the ~/.forward file, real email addresses also can expand to mailing lists.

[210] * Only root should be permitted to write to the aliases file. If you keep mailing lists inside that file, it might need to be writable by others. This can create a security breach (Recommended Permissions on page 167).

[211] * The sendmail program also performs this check for critical system files, such as its configuration file.

[212] * The

sendmail program used the

Errors-To:

header, despite the fact that it was originally a

hack to get around UUCP, which confused the

envelope and header. The Errors-To: header is not an Internet

standard (in fact, it violates the Internet

standards) and cannot be expected to work on MTAs

other than sendmail. In fact,

support for the UseErrorsTo option might be removed in

the future.

[213] * The

vacation(1) program is a

wonderful tool for advising others that mail will

not be attended to for a while. Unfortunately,

some older versions of that program still exist

that reply to bulk mail, thereby causing problems for

the mailing-list maintainer.

[214] * IANA stands for Internet Assigned Numbers Authority.

[215] * Prior to V8 sendmail, the ~/.forward file could live only in the user’s home directory and had to be called .forward.

[216] † This is supported only under operating systems that properly support seteuid(3) or setreuid(3) (USESETEUID on page 151).

[217] * Under old versions of sendmail, the vrfy and expn commands are interchangeable. Under V8 sendmail and other, modern SMTP servers, the two commands differ.

[218] † In place of specifying port 25, you can use either mail or smtp. These are more mnemonic and easier to remember (although we “old timers” tend to still use 25).

[219] * V8 sendmail uses the owner of the ~/.forward file in addition to the program name when comparing.