Chapter 9. DNS and sendmail

Overview

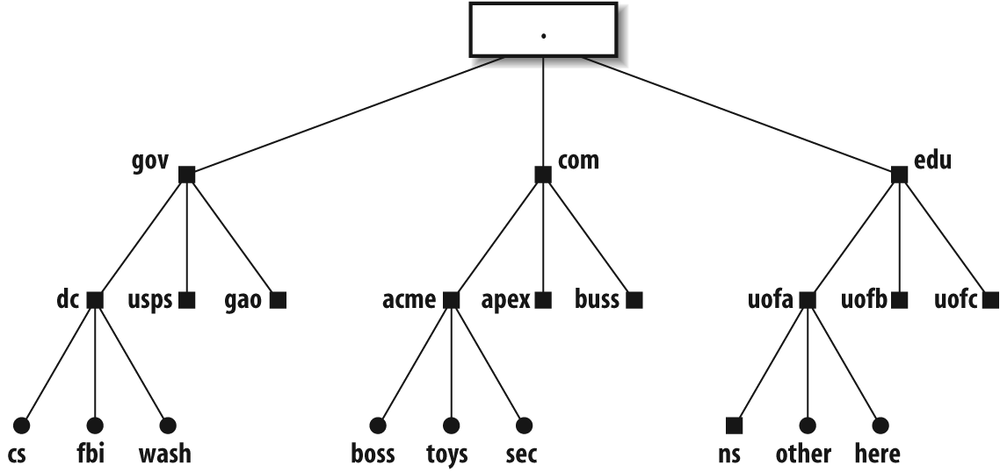

DNS stands for Domain Name System. A domain is any logical collection of related hostnames or site names. A naming system is best visualized as an inverted tree of information that corresponds to fully qualified domain names (see Figure 9-1) organized in a name space (as opposed to physical space). Local or regional knowledge about an individual part of that name space is call a DNS zone. We will expand on these concepts soon.

The parts of a fully qualified name are separated from one another with dots. For example:

here.uofa.edu

This name describes the machine here that is part of the uofa subdomain of the

edu top-level

domain. In Figure 9-1,

the dot at the top is the “root” of the tree. It is implied

but not always[147] included in fully qualified domain names:

here.uofa.edu.

↑

impliedThe root zone is served by machines running software enabling them to function as name servers.[148] Each has knowledge of all the top-level domains (such as gov, com, biz, uk, au, etc.) and the server machines for those domains. Each of the top-level domain’s servers knows of one or more machines with knowledge of the next level below. For example, the server for edu “knows” about the subdomains uofa, uofb, and uofc but might not know about anything below those subdomains, nor about the other domains next to itself, such as com.[149]

A knowledgeable machine, one that can look up or distribute information about its domain and subdomains, is called a name server. Each is required to have knowledge only of what is immediately below it. This minimizes the amount of knowledge any given name server must store and administer.

The use of a name space is designed to make the access to host- or domain-specific information efficient. The location within a name space need not correspond to a physical location. For example, in Figure 9-1, the host here.ufa.edu could be in Los Angeles, whereas the host other.uofa.edu could be in Denver.

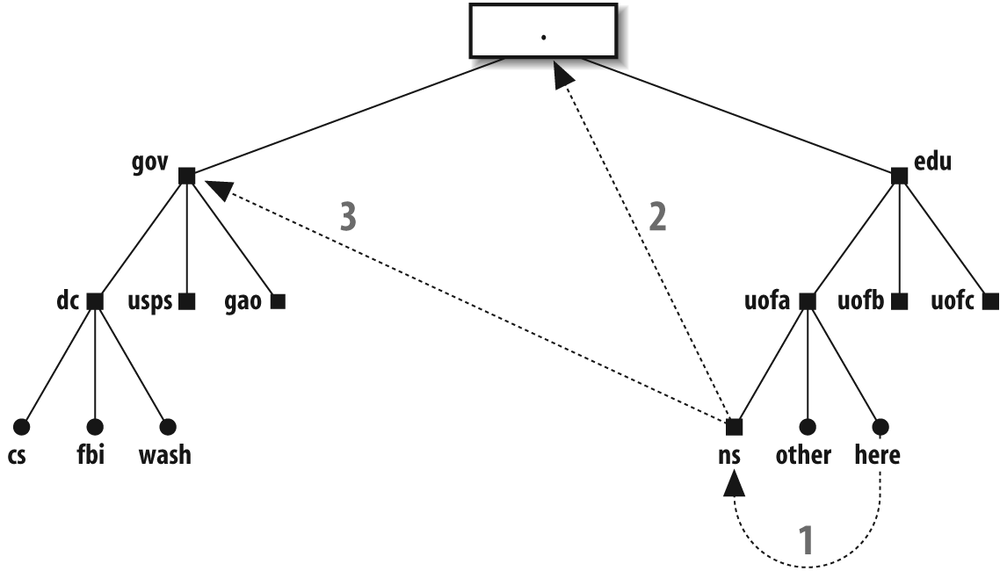

The way the name space information is used is illustrated in Figure 9-2. The steps that are taken when sendmail on here.uofa.edu (the local host) attempts to connect to fbi.dc.gov (the remote host) to send an email message to a user there are explained immediately following the figure.

The local sendmail needs the IP address of the remote host to initiate a network connection. The local sendmail asks its local name server (say, ns.uofa.edu) for that address. The ns.uofa.edu name server might already know the address (having cached that information during a previous inquiry). If so, it gives the requested address to the local sendmail, and no further DNS requests need to be made. If the local name server doesn’t have that information, it contacts other name servers for the needed information.

In the case of fbi.dc.gov, the local name server next contacts one of the root servers (the dot in the big box in our example). A root server will likely not have the information requested but will indicate the best place to inquire. For our example, the root server recommends the name server for the .gov domain and provides our local name server with the address of that .gov domain server machine.

The local name server then contacts one of the .gov name servers. This process continues until a name server provides the needed information. As it happens, any name server can return the final answer if it has the authority to do so. For our example, .gov knows the address, and is authoritative, for fbi.dc.gov. It returns that address to the local name server, which in turn returns the address to the local sendmail.

Note that this is a simplified description. The actual practice can be more or less complex depending on which name servers are “authoritative” for which domains and what is cached where.

The sendmail program needs the IP address of the machine to which it must connect. That address can be returned by name servers in three possible forms:

An MX record lists one or more machines that have agreed to receive mail for a particular site or machine. Multiple MX records are tried in order of cost[150] (least to most). An MX record does not need to point to the looked-up host. MX records always take precedence over A records.

An address record gives the IP address directly. For IPv4 this is called an A record, and for IPv6 this is called an AAAA record.

A CNAME (Canonical NAME, or alias) record refers sendmail to the real name, which can have an A record, an AAAA record, or MX records. But note that an MX record may not have a CNAME as its value.

Which BIND?

Before we discuss DNS in greater depth, we must first attend to an administrative detail. Every site on the Internet should, at a minimum, run BIND software version 9.x. BIND provides the software and libraries that are needed to perform DNS inquiries(9.3.4 is the latest release of 9.x as of this writing).

Unless you are already running the latest version, you should consider upgrading. The latest versions are available from http://www.isc.org/.

In this book, we won’t describe how to install BIND. Instead, you should refer to the book DNS and BIND, Fifth Edition, by Paul Albitz and Cricket Liu (O’Reilly).

Make sendmail DNS-Aware

Not all releases of sendmail are ready to use DNS. To determine whether yours is ready, type the following command:

%/usr/sbin/sendmail -d0.1 -bt < /dev/nullVersion 8.14.1 Compiled with: LOG MIME8TO7NAMED_BINDNETINET NETUNIX NEWDB SCANF USERDB XDEBUG = == == == == == = SYSTEM IDENTITY (after readcf) = == == == == == = (short domain name) $w = here (canonical domain name) $j = here.uofa.edu (subdomain name) $m = uofa.edu (node name) $k = here = == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == == =

Look for a statement that indicates whether your

sendmail was compiled with

NAMED_BIND

support (NAMED_BIND on

page 124). If it was, it can use DNS. If it wasn’t,

either you will have to get a corrected version from

your vendor, or you will have to download and

compile the latest version of

sendmail from scratch (Download the Source on page

42).

But even if your sendmail binary

supports DNS, site configuration might not. If your

host supports a service-switch file, for instance,

make sure that file lists dns as the method used to fetch

information about hosts.

If your sendmail still seems unable to use DNS, despite your efforts, look for other reasons for failure. Make sure, for example, that your /etc/resolv.conf file is present and that it contains the address (not the name) of a valid name-server machine for your domain.

How sendmail Uses DNS

The sendmail program uses DNS in several different ways:

When sendmail first starts, it might use DNS to get the canonical name for the local host. That name is then assigned to the

$jmacro ($j on page 830).[151] If DNS returns additional names for the local host, those names are assigned to the class$=w($=w on page 876).When sendmail first starts, it looks up the IP address or addresses assigned to each network interface. For each address it finds, it uses DNS to look up the hostname associated with that address.

When another host connects to the local host to transfer mail, the local sendmail looks up the other host with DNS to find the other host’s canonical name.

Before accepting mail, sendmail can look up the IP address of the connecting host on various blacklist sites (How DNSBL Works on page 260). If that address is listed, the message is rejected.

To relay based on MX records (FEATURE(relay_based_on_MX) on page 271), sendmail does a lookup to determine whether the connecting host is listed as an MX server for the local domain.

When delivering network SMTP mail, sendmail uses DNS to find the address (or addresses) to which it should connect.

When sendmail expands

$[and$]in the RHS of a rule, it looks up the hostname (or IP address) between them.

We discuss each of these uses later in this chapter.

Determine the Local Canonical Name

All versions of sendmail use more or less the same logical process to obtain the canonical name of the local host. As illustrated in the following sample program, sendmail first calls gethostname(3) to obtain the local host’s name within its domain. That name can be either a short name or a fully qualified one depending on how your system is set up. If the call to gethostname(3) fails, the name of the local host is set to localhost:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/param.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <stdio.h>

main( )

{

char hostbuf[MAXHOSTNAMELEN];

struct hostent *hp;

/* Get the local host name */

if (gethostname(hostbuf, sizeof(hostbuf)) < 0)

{

strcpy(hostbuf, "localhost");

}

printf("hostname = "%s"\n", hostbuf);

/* canonicalize it and get aliases */

if((hp = gethostbyname(hostbuf)) = = NULL)

{

perror("gethostbyname");

exit(2);

}

printf("canonical = "%s"\n", hp->h_name);

while (*hp->h_aliases != NULL)

{

printf("alias: "%s"\n", *hp->h_aliases);

++hp->h_aliases;

}

}The local hostname is then given to the gethostbyname routine to obtain the canonical name for the local host. That same routine also returns any aliases (other names for the local host). Note that, if you defined NETINET6 (NET... on page 126) when compiling (for IPv6 support), you must use getipnodebyname(3) in place of gethostbyname(3).

The short (host) name found by

gethostbyname(3) or

getipnodebyname(3) is

assigned as the value of the $w

sendmail macro. The short name,

the canonical name, and any aliases are added to the

class $=w.

If the DontProbeInterfaces option (DontProbeInterfaces on page 1023) is

undefined, or set to false, the address and hostname

associated with each interface are also added to the

class $=w (Probe Network Interfaces on page

327).

Some old Sun and Ultrix machines are set up to use NIS where the canonical name is the short name, and a fully qualified name that should have been the canonical name appears as an alias. For such systems, you must link with the BIND library (libresolv.a) when compiling this program or compiling sendmail. That library gets its information from DNS rather than from NIS. But note that V8.7 and above versions of sendmail do the intelligent thing and use the canonical name that was found in the list of aliases, if it exists.

If a good BIND library is not available, or if it is

not convenient to compile and install a new version

of sendmail, you can circumvent

the short name assigned to the $j

sendmail macro by defining

$j like

this:

define(`confDOMAIN_NAME', `canonical name here')

The canonical name is your

site’s hostname with a dot and your domain name

appended.

The result of all these lookups can be viewed by

running sendmail with a

-d0.4 debugging

switch (-d0.4 on page 542). The

actual DNS lookups can be watched with the -d8.8 debugging switch

(-d8.8 on page 549).

Probe Network Interfaces

After the canonical name, and any other names for the

local machine, have been placed in $=w,

sendmail then searches

(probes) all the network interfaces to find any

additional names and addresses that might also need

to be added to $=w. But note that if the DontProbeInterfaces

option (DontProbeInterfaces on

page 1023) is defined as true, this additional step

is skipped. Note also that if the DontProbeInterfaces

option is defined as the literal value localhost, only the

loopback interface is

skipped, and all the other network interfaces are

included.

The list of network interfaces is obtained from your kernel using a system call appropriate for your operating system. The kernel generally returns a list composed of interface and IP address pairs. If you defined NETINET6 (NET... on page 126) when compiling, the list might contain IPv6 addresses. If you defined NETINET (NET... on page 126) when compiling, the list might contain IPv4 addresses.

For each address that is found, sendmail performs a reverse lookup using gethostbyaddr(3) or getipnodebyaddr(3). Each lookup (if successful) will return the hostname associated with the address.

Each address and hostname is appended to the class

$=w. The names

and addresses added can be viewed with the -d0.4 debugging

command-line switch (-d0.4 on page

542), which also allows errors in this process to be

printed.

Look Up a Remote Host’s Name

When sendmail begins to run as a

daemon, it creates a socket, binds to that socket,

and listens for incoming SMTP connections. When a

remote host connects to the local host,

sendmail uses the

accept(2) library routine to

accept the connection. The

accept(2) routine provides

the IP address of the remote machine to

sendmail. After that, it

calls gethostbyaddr(3) or

getipnodebyaddr(3) to convert

that IP address to a canonical hostname. The

sendmail program then calls

gethostbyname(3) or

getipnodebyname(3) to find

all the addresses for that found hostname. If the

original address is not in that list,

sendmail considers the

address and hostname to be forgeries and records

that fact in its syslog

messages, its added Received: header, and its reply to the

initial greeting:

(may be forged)

The sendmail program needs a valid canonical hostname for five reasons:

The remote hostname is compared to the local hostname to prevent sendmail from connecting to itself.

The remote hostname claimed in the HELO or EHLO SMTP line is compared to the canonical name. If they differ, sendmail adds text noting that difference to its SMTP reply, and adds both to the

Received: header it generated.The macro

$sis assigned the canonical hostname as its value.The canonical name is included in many log messages produced by the setting of the

LogLevel(L) option (LogLevel on page 1040) and is available for inclusion inReceived: header (Received: on page 1162) lines.The canonical name is used by the various antirelay rule set checks.

DNS Blacklist Lookups

If you define the dnsbl feature (FEATURE(dnsbl) on page 261) or the enhdnsbl feature (FEATURE(enhdnsbl) on page 263) in your mc

configuration file, you will cause

sendmail to look up the IP

address of each connecting site at the blackhole

server you specify. If a lookup is successful and

returns a match, the connection is rejected, or as

of V8.14, discarded or quarantined. If a lookup is

successful and returns no match, the connection is

accepted. If the lookup fails, the connection is

either deferred or accepted, depending on the nature

of the failure.

Lookups are performed using the host database type

(dns on page 905). Each lookup

attempts to find A (address) records that correspond

to the address looked up. Note that this is

different from the usual way in which addresses are

looked up. Normally, addresses are reverse-looked-up

to find hostnames. But for blackhole purposes,

addresses are forward-looked-up, as though they are

hostnames.

Look Up Addresses for Delivery

When sendmail prepares to connect to a remote host for transfer of mail, it first performs a series of checks that vary from version to version. All versions accept an IP address surrounded with square brackets as a literal address and use it as is.

Beginning with V8.1, sendmail first checks to see whether the host part of the address is surrounded with square brackets. If so, it skips looking up MX records. (We’ll elaborate on MX records soon.)

Beginning with V8.8, sendmail

first checks to see whether the F=0 flag (F=0 (zero)

on page 761) is set for the selected delivery agent.

If it is set, sendmail skips

looking up MX records.

If sendmail is allowed to look up MX records, it calls the res_search(3) BIND library routine to find all the MX records for the host. If it finds any MX records, it sorts them in order of cost, and lists them, placing the least expensive first. If V8 sendmail finds two costs that are the same, it randomizes the selection between the two when sorting.[152]

After all MX records are found and listed, or if no MX

records are found, sendmail

adds the host specified by the FallbackMXhost option

(FallbackMXhost on page 1030) to

the end of the list. For V8.11 and earlier, the

hostname, if there was one, was added to the end of

the list as is. Beginning with V8.12, if a hostname

is listed, MX records are looked up for it as well,

and those MX records are added (in the proper sorted

order) to the end of the list. By surrounding the

hostname specified under V8.12 in square brackets,

the behavior of earlier versions is emulated in that

the hostname is added as is (surrounded in square

brackets).

If there are no MX records, the original hostname

becomes the only entry in the list. If, in this

instance, the FallbackMXhost option adds MX records,

they are added following that hostname.

The sendmail program then tries to deliver the message to each host in the list of MX hosts, one at a time, until one of them succeeds or until they all fail. The value of an MX record contains a cost value (also called preference) and the hostname to which to connect. All MX hosts at a given cost (preference) are tried before any at a higher cost (lower preference) are tried (that is, all the 5’s are tried, for example, before any 6’s). Beginning with V8.8 sendmail, if a host in the list returns a 5xy SMTP code (permanent failure), the effect is to cause subsequent MX hosts to be ignored. (Connect failures are the exception, in that they continue to the next MX host as usual.) Most temporary errors cause sendmail to try the next MX record. If sendmail exhausts the MX list with neither success nor a permanent error, the temporary error will cause the message to be queued for a later attempt.

If no MX records are found,

sendmail tries to deliver the

message to the address of the single original host.

If all else fails, sendmail

attempts to deliver to the host listed with the

FallbackMXhost

option. And, beginning with V8.13, if the FallbackMXhost host

fails or was not defined, and if the FallBackSmartHost option

(FallBackSmartHost on page 1031)

is defined, the host defined by the FallBackSmartHost option

is the last host attempted.

Whether sendmail tries to connect to the original host or to a list of MX hosts or to a fallback host, it calls gethostbyname(3) or getipnodebyname(3) to get the network address for each. It then opens a network connection to each address in turn and attempts to send SMTP mail. If there are IPv6 addresses,[153] they are tried first, then IPv4 addresses, if any. If a connection fails, it proceeds to the next address in the list until the list is exhausted. When there are no more addresses to try, the message is deferred and held in the queue for a later attempt.

The $[and $] Operators

The $[ and $] operators (Canonicalize Hostname: $[ and $] on page 668) are used to canonicalize a hostname.

Here is a simplified description of the

process.

Each lookup is actually composed of many lookups that occur in the form of a loop within a loop. In the outermost loop, the following logic is used:

If the hostname has at least one dot somewhere in it, sendmail looks up its address unmodified first.

If the unmodified hostname is not found and the RES_DNSRCH bit is set (the

ResolverOptionsoption, ResolverOptions on page 1080), sendmail looks up variations on the domain part of the address. The default domain is tried first (for a host in the sub-subdomain at dc.gov, that would be sub.dc.gov, thus looking up host.sub.dc.gov). If that fails, BIND 4.9 and above use thesearchattribute, if given, and try that list of possible domains. BIND 4.8 then throws away the lowest part of the domain and tries again (looks up host.dc.gov).If the hostname has no dots and the RES_DEFNAMES bit is set (the

ResolverOptionsoption, ResolverOptions on page 1080), sendmail tries the single default domain (looks up host.sub.dc.gov). This is for compatibility with older versions of DNS.

Each lookup just described is performed by using the following three steps:

Prior to V8.12 sendmail, try the hostname with a T_ANY query that requests all the cached DNS records for that host. If it succeeds, IPv6 AAAA records, IPv4 A records, and/or MX records might be among those returned. However, success is not guaranteed because sometimes only NS records are returned. In that instance, the following two steps are also taken.

Beginning with V8.12 sendmail, if using IPv6, try the hostname with a T_AAAA query that requests the AAAA record, and then, if using IPv4, try the hostname with a T_A query that requests the A records.

If only NS records are returned, try the hostname with a T_MX query that requests MX records for the host.

Each query searches the data returned as follows:

Search for a CNAME (alias) record. If one is found, replace the initial hostname (the alias) with the canonical name returned and start over.

Search for an A or AAAA record (the IP address). If one is found, the hostname that was just used to query is considered the canonical address.

Search for an MX record. If one is found and a default domain has not been added, treat the MX record like an A record. For example, if the input hostname is sub.dc.gov and an MX record is found, the MX record is considered official. If, on the other hand, the input hostname has no domain added (is sub) and the query happens to stumble across sub.dc.gov as the MX record, the following searches are also tried.

If an MX record is found and no MX record has been previously found, the looked-up hostname is saved for future use. For example, if the query was for sub.dc.gov and two MX records were returned (hostA.sub.dc.gov and hostB.sub.dc.gov), sub.dc.gov is saved for future use.

If no MX record is found, but one was found previously, the previous one is used. This assumes that the search is normally from most to least complex (sub.sub.dc.gov, sub.dc.gov, dc.gov).

All this apparent complexity is necessary to deal with wildcard MX records (Wildcard MX Records on page 335) in a reasonable and usually successful way.

Broken IPv6 Name Servers

The sendmail program will look up AAAA records only if it is built with the NETINET6 (NET... on page 126) compile-time macro defined. As described earlier, sendmail looks up the AAAA records first, then A records.

All name servers should return NODATA if a host is found and no AAAA records are available. But some name servers are broken and, when asked for an AAAA record, will wrongly return a temporary failure (SERVFAIL). This causes sendmail to queue the mail for later delivery.

If you have defined NETINET6 when building sendmail, and if you notice this kind of error, we have two recommendations:

Notify hostmaster[154] at the site that is running the broken name server. The sooner broken name servers are fixed, the cleaner the Internet will run.

Add the

WorkAroundBrokenAAAAargument to theResolverOptionsoption (ResolverOptions on page 1080) in your mc configuration file:define(`confBIND_OPTS', `+WorkAroundBrokenAAAA')

This will cause sendmail to pretend that NODATA was returned when SERVFAIL is wrongly returned. This causes sendmail to continue with further lookups, specifically for A and MX records.

Set Up MX Records

An MX record is simply the method used by DNS to route mail bound for one machine to another instead. An MX record is created by a single line in one of your named(8) files:

hostA IN MX 10 hostB

This line says that all mail destined for hostA in your domain

should instead be delivered to hostB in your domain. The IN says that this is an

Internet-type record, and the 10 is the cost for using this MX

record.

An MX record can point to another host or to the original host:

hostA IN MX 0 hostA

This line says that mail for hostA will be delivered to hostA. Such records might

seem redundant, but they are not because a host can have

many MX records (one of which can point to itself

):

hostA IN MX 0 hostA

IN MX 10 hostBHere, hostA has the lowest

cost (0 versus 10 for hostB), so the first

delivery attempt will be to hostA. If hostA is unavailable, delivery will be

attempted to hostB

instead.

Usually, MX records point to hosts inside the same domain. Therefore, managing them does not require the cooperation of others. But it is legal for MX records to point to hosts in different domains:

hostA IN MX 0 hostA

IN MX 10 host.other.domain.Here, you must contact the administrator at other.domain and obtain

permission before creating this MX record. We cover this

concept in more detail when we discuss disaster preparation

later in this chapter.

Although MX records are usually straightforward, there is one risk, and there can be a few problems associated with them.

Failover MX Servers Result in Spam

Email spammers tend to send to the highest cost MX server, rather than the lowest cost one as you might expect. To illustrate, consider a backup MX server that is intended for emergency use only:

hostA IN MX 0 hostA

IN MX 100 BackupHostHere, hostA has the

lowest cost (0

versus 100 for

BackupHost), so

the first delivery attempt should be to hostA. But most

spam-sending software ignores low-cost records (the

record for hostA

in the preceding code) and will instead deliver to

the highest cost server (BackupHost) on purpose.

The theory is that a site will run connection-based

spam filters on the main (lowest cost) server

(hostA) but

will be much more lax on a failover MX server that

is intended only for emergency use (BackupHost). The main

server (hostA)

will never reject connections from its own failover

MX server (BackupHost). Spam senders use that

knowledge to circumvent connection-based rejections

by always sending to the failover MX server.

If you list multiple MX records, be certain that the same level of connection-based spam controls are installed on all of them. Content-based spam control may still reside only on the main mail server because it will still screen messages from all MX failover machines.

MX Must Point to Host with an A or AAAA Record

The A and AAAA records for a host are lines that give the host’s IP address or addresses:

hostC IN A 123.45.67.8 ← IPv4 hostC IN AAAA 3ffe:8050:201:1860:42::1 ← IPv6

Here, hostC is the

host’s name. The IN says this is an Internet-type

record. The A

marks this as an IPv4 A record, with the IP address

123.45.67.8.

The AAAA marks

this as an IPv6 AAAA record, with the IP address

3ffe:8050:201:1860:42::1.

An MX record must point to a hostname that has an A or AAAA record. To illustrate, consider the following:

hostA IN MX 10 hostB ← illegal

IN MX 20 hostC

hostB IN MX 10 hostC

hostC IN A 123.45.67.8Note that hostB

lacks an A record but hostC has one. It is illegal to point

an MX record at a host that lacks an A or AAAA

record. Therefore, the first line in the preceding

example is illegal, whereas the second line is

legal.

Although such a mistake is difficult to make when maintaining your own domain tables, it can easily happen if you rely on a name server in someone else’s domain, as shown here:

hostA IN MX 10 mail.other.domain.

The other administrator might, for example, retire the

machine mail and

replace its A record with an MX record that points

to a different machine. Unless you are notified of

the change, your MX record will suddenly become

illegal.

Note that although an MX record must point to a hostname that has an A or AAAA record, it is illegal for an MX record to point directly to an A or AAAA record:

hostA IN MX 10 123.45.67.89 ← illegalFinally, note that it is unwise to point an MX record at a domain name, because a domain is not a host and therefore is not required to have an A or an AAAA record.

MX to CNAME Is Illegal

The sendmail program is frequently more forgiving than other MTAs because it accepts an MX record that points to a CNAME record. The presumption is that, eventually, the CNAME will correctly point to an A or AAAA record. But beware: this kind of indirection can cost additional DNS lookups. Consider this example of an exceptionally bad setup:

hostA IN MX 10 mailhub mailhub IN CNAME nfsmast nfsmast IN CNAME hostB hostB IN A 123.45.67.89

First, sendmail looks up hostA and gets an MX

record pointing to mailhub. Because there is only a single

MX record, sendmail considers

mailhub to be

official. Next, mailhub is looked up to find an A or

AAAA record (IP address), but instead a CNAME

(nfsmast) is

returned. Now, sendmail must

look up the CNAME nfsmast to find its A or AAAA record.

But again a CNAME is returned instead. So,

sendmail must again look for

an A or AAAA record (this time with hostB). Finally,

sendmail succeeds by finding

the A record for hostB, but only after far too many

lookups.[155]

The correct way to form the preceding DNS file entries is as follows:

hostA IN MX 10 hostB mailhub IN CNAME hostB nfsmast IN CNAME hostB hostB IN A 123.45.67.89

In general, try to construct DNS records in such a way that the fewest lookups are required to resolve any records.

MX Records Are Nonrecursive

Consider the following MX setup, which causes all mail

for hostA to be

sent to hostB and

all mail for hostB to be sent to hostB, or to hostC if hostB is down:[156]

hostA IN MX 10 hostB

hostB IN MX 10 hostB

IN MX 20 hostCOne might expect sendmail to be

smart and deliver mail for hostA to hostC if hostB is down. But

sendmail won’t do that. The

RFC standards do not allow it to recursively look up

additional MX records. If

sendmail did, it could get

hopelessly entangled in MX loops. Consider the

following:

hostA IN MX 10 hostB

hostB IN MX 10 hostB

IN MX 20 hostC

hostC IN MX 10 hostA ← potential loopIf your intention is to have hostA MX to two other hosts, you must

state that explicitly:

hostA IN MX 10 hostB

IN MX 20 hostC

hostB IN MX 10 hostB

IN MX 20 hostCAnother reason sendmail refuses

to follow MX records beyond the target host is that

costs in such a situation are undefined. Consider

the previous example with the potential loop. What

is the cost of hostA when MX’d by hostB to hostC? Should it be the

minimum of 10, the maximum of 20, the mean of 15, or

the sum of 30?

Wildcard MX Records

Wildcard MX records should not be used unless you understand all the possible risks. They can provide a shorthand way of MX’ing many hosts with a single MX record, but it is a shorthand that can be easily abused. For example:

*.dc.gov. IN MX 10 hostB

This says that any host in the domain .dc.gov (where that host

doesn’t have any record of its own) should have its

mail forwarded to hostB.

; domain is .dc.gov *.dc.gov. IN MX 10 hostB hostA IN MX 10 hostC hostB IN A 123.45.67.8

Here, mail to hostD

(no record at all) will be forwarded to hostB. But the wildcard

MX record will be ignored for hostA and hostB because each has

its own record.

Extreme care must be exercised in setting up wildcard MX records. It is easy to create ambiguous situations that DNS might not be able to handle correctly. Consider the following, for example:

; domain is sub.dc.gov *.dc.gov. IN MX 10 hostB.dc.gov. *.sub.dc.gov. IN MX 10 hostC.dc.gov.

Here, an unqualified name such as the plain hostD matches both

wildcard records. This is ambiguous, so DNS

automatically picks the most complete one (*.sub.dc.gov.) and

supplies that MX record to

sendmail.

One compelling weakness of wildcard MX records is that they match any hostname at all, even for machines that don’t exist:

; domain is sub.dc.gov *.dc.gov. IN MX 10 hostB.dc.gov.

Here, mail to foo.dc.gov will be

forwarded to hostB.dc.gov, even if there is no host

foo in that domain.

Wildcard MX records almost never have any appropriate use on the Internet. They are often misunderstood and are often used just to save the effort of typing hundreds of MX records. They do, however, have legitimate uses behind firewall machines and on networks not connected to the Internet.

What? They Ignore MX Records?

Many older MTAs on the network ignore MX records. Some

pre-Solaris Sun sites, for example, wrongly run the

non-MX version of sendmail when

they should use

/usr/lib/sendmail.mx. Some

Solaris sites wrongly do all host lookups with NIS

when they should list dns on the hosts line of their

/etc/nsswitch.conf file.

Because of these and other mistakes, you will

occasionally find some sites that insist on sending

mail to a host even though that host has been

explicitly MX’d to another.

To illustrate why this is bad, consider a UUCP host that has only an MX record. It has no A record because it is not on the network:

uuhost IN MX 10 uucpserver

Here, mail to uuhost will be sent to uucpserver, which will

forward the message to uuhost with UUCP software. An attempt

to ignore this MX record will fail because uuhost has no other

records. Similar problems can arise for printers

with direct network connections, terminal servers,

and even workstations that don’t run an SMTP daemon

such as sendmail.

If you believe in DNS and disdain sites that don’t, you can simply ignore the offending sites. In this case, the mail will fail if your MX’d host doesn’t run a sendmail daemon (or another MTA). This is not as nasty as it sounds. There is actually considerable support for this approach; failure to obey MX records is a clear violation of published network protocols. RFC1123, Host Requirements, Add STARTTLS Support to Your mc File, notes that obeying MX records is mandatory. RFC1123 has existed for more than 12 years.

On the one hand, to ensure that all mail is received,

even on a workstation whose mail is MX’d elsewhere,

you can run the sendmail daemon

on every machine. On the other hand, to ensure that

all mail is received, even for hosts that are not

machines (like uuhost earlier) you can assign each

such host an IP address that is the IP address of

your mail server.

Caching MX Records

Although you are not required to have MX records for all hosts, there is a good reason to consider doing so. To illustrate, consider the following host that has only an A record:

hostB IN A 123.45.67.8

When V8.12 and above sendmail first look up this host, they ask the name server for that host’s MX records. Because there are none, that request comes back empty. The sendmail program must then make a second lookup for the IP address.

When pre-V8.12 sendmail first looks up this host, it asks the local name server for all records. Because there is only an A record, that is all it gets. But note that asking for any record causes the local name server to cache the information.

The next time sendmail looks up this same host, the local name server will return the A record from its cache. This is faster and reduces Internet traffic. The cached information is “nonauthoritative” (because it is a copy) and includes no MX records (because there are none).

When pre-V8.12 sendmail gets a nonauthoritative reply that lacks MX records, it is forced to do another DNS lookup. This time, it specifically asks for MX records. In this case there are none, so it gets none.

Because hostB lacks

an MX record, sendmail performs

a DNS lookup each and every time mail is sent to

that host. If hostB were a major mail-receiving site,

its lack of an MX record would cause many

sendmail programs, all over

the world, to waste network bandwidth with useless

DNS lookups.

We strongly recommend that every host on the Internet have at least one MX record. As a minimum, it can simply point to itself with a low cost:

hostB IN A 123.45.67.8

IN MX 1 hostBThis will not change how mail is routed to hostB but will reduce

the number of DNS lookups required.

Ambiguous MX Records

RFC974 leaves the treatment of ambiguous MX records to the implementor’s discretion. This has generated much debate in sendmail circles. Consider the following:

foo IN MX 10 hostA

foo IN MX 20 hostB ← mail from hostB to foo

foo IN MX 30 hostCWhen mail is sent from a host (hostB) that is an MX

record for the receiving host (foo) all MX records that

have a cost equal to or greater than that of

hostB must be

discarded. The mail is then delivered to the

remaining MX host with the lowest cost (hostA). This is a

sensible rule because it prevents hostB from wrongly

trying to deliver to itself.

It is possible to configure hostB so that it views the name

foo as a

synonym for its own name. Such a configuration

results in hostB

never looking up any MX records because it

recognizes mail to foo as local.

But what should happen if hostB does not recognize foo as local and if

there is no hostA?

← no hostA foo IN MX 20 hostB ← mail from hostB to foo foo IN MX 30 hostC

Again, RFC974 says that when mail is being sent from a

host (hostB) that

is an MX record for the receiving host (foo) all MX records that

have a cost equal to or greater than that of

hostB must be

discarded. In this example, that leaves

zero MX records. Three

courses of action are now open to

sendmail, but RFC974 doesn’t

say which it should use:

Assume that this is an error condition. Clearly, hostB should have been configured to recognize foo as local. It didn’t (hence the MX lookup and discarding in the first place), so it must not have known what it was doing. V8 sendmail with the

TryNullMXListoption (TryNullMXList on page 1112) not set (undeclared or declared as false) will bounce the mail message with this message:553 5.3.5 host config error: mail loops back to me (MX problem?)Look to see whether foo has an A record. If it does, go ahead and try to deliver the mail message directly to foo. If it lacks an A record, bounce the message. This approach runs the risk that foo might not be configured to properly accept mail (thus causing mail to disappear down a black hole). Still, this approach can be desirable in some circumstances. V8 sendmail with the

TryNullMXListoption (TryNullMXList on page 1112) set to true always tries to connect to foo.[157]Assume (even though it has not been configured to do so) that foo should be treated as local to hostB. No version of sendmail makes this assumption.

This situation is not an idle exercise. Consider the

MX record for uuhost presented in the previous

section:

uuhost IN MX 10 uucpserver

Here, uuhost has no

A or AAAA record because it is connected to uucpserver via a dial-up

line. If uucpserver is not configured to

recognize uuhost

as one of its UUCP clients, and if mail is sent from

uucpserver to

uuhost, it will

query DNS and get itself as the MX record for

uuhost. As we

have shown, that MX record is discarded, and an

ambiguous situation has developed.

How to Use dig

The dig(1) program is distributed with the BIND name server software. It is a command-line program that permits users to easily look up hosts and addresses in the same way sendmail does. We won’t cover all the bells and whistles of dig(1) here (read the online manual); instead, we will provide you with only the four basic commands you need to use dig(1):

% dig host.domain ← look up a host by name (§9.4.1 on page 339) % dig -x IPaddress ← reverse-look-up an IP address (§9.4.2 on page 341) % dig mx host.domain ← look up MX records (§9.4.3 on page 342) % dig @nameserver host.domain ← use a different name server (§9.4.4 on page 343)

After you have learned these basic commands, you will wonder how you ever lived without this program.

Look Up a Host by namewith dig(1)

The dig(1) program can be used to look up the IP address of a host by specifying the hostname:

% dig example.comThe first time you run dig(1) you may be surprised by the volume of its output,[158] which is composed of comment lines (that begin with a semicolon) and information lines. The first section of output that dig(1) prints might look like this:

% dig example.com

; <<>> DiG 9.2.3 <<>> example.com

;; global options: printcmd

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 2, ADDITIONAL: 1This first section is a summary of dig(1)’s command line

and information about how it performed the lookup.

The global

options line shows the resolver options

that were in effect when you ran the command. Here,

printcmd means

that introductory comment lines and other

information will print in addition to the answer. If

you wish to restrict dig(1)’s output to just the

answer, you can execute it with a +short command-line

argument. We demonstrate that argument

shortly.

The next section of commentary begins with the “Got answer” line:

;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 19898

Here, the opcode is

QUERY, which

means a simple lookup was performed. The status is NOERROR, which means the

lookup was successful, and the id shows the ID of the

dig(1) query itself.

The last section of introductory commentary produced by dig(1) is a summary of what it found:

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 2, ADDITIONAL: 2

The flags are the actual flags returned by the name

server. The qr is

present if this answer is a response to a request.

(Note that because dig(1) only performs lookups,

this flag will always be set.) The rd is present if the

lookup request asked for recursion to be used to get

a result. The ra

is present if the replying server actually used said

recursion. These, and other possible flags that

might appear, are documented in RFC1035.

A list of what was returned by the lookup follows the

flags on the same line. There are four possible

items, each of which may have a value of zero or

more. In the above, one question was answered

(QUERY: 1), one

record was provided as the answer (ANSWER: 1), two

authority replies were included (AUTHORITY: 2), and two

additional records were provided (ADDITIONAL: 2).

Following the introductory commentary is the QUESTION SECTION:

;; QUESTION SECTION: ;example.com. IN A

The QUESTION

SECTION echoes your original query in

the form of a comment. Here, you originally provided

dig(1) with a hostname as its command-line argument,

implying that you wished to obtain the host’s IP

address. An IP address is also an Internet (the

IN) address

(the A).

Following the QUESTION

SECTION is the ANSWER SECTION which, sensibly,

provides the answer to the question, in this case

the IP address for the domain

example.com:

;; ANSWER SECTION: example.com. 2D IN A 192.0.34.166

If more information is available, that too, will be

returned. Here, the address was returned (the

192.0.34.166)

along with information that this record will time

out in two days (the 2D), that the record is an Internet

record (the IN),

and that it is an A (address) record (an IP

address).

If this domain had more than one address, more lines would be listed. For example, the following shows three answers:

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 3, AUTHORITY: 2, ADDITIONAL: 2 ;; ANSWER SECTION: example.com. 2D IN A 192.0.34.166 example.com. 2D IN A 192.168.0.1 example.com. 2D IN A 192.168.1.1

The next section that appears (if such information was

returned) is the AUTHORITY

SECTION. The AUTHORITY SECTION lists name server

(NS) records

for the domain, although it can also contain a Start

Of Authority (SOA) record.

;; AUTHORITY SECTION: example.com. 6H IN NS b.iana-servers.net. example.com. 6H IN NS a.iana-servers.net.

Here, two name server machines are listed. Either one

can provide authoritative information about this

domain, hence the term and title AUTHORITY SECTION. In

order to look up additional information about this

domain, we need to know more than just the hostnames

of the name servers. We also need their

addresses.

The last section to appear is the ADDITIONAL (information)

SECTION. It

provides any information that was missing from the

other sections, if that additional information is

necessary for future lookups:

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION: a.iana-servers.net. 13h31m29s IN A 192.0.34.43 b.iana-servers.net. 13h31m29s IN A 192.168.5.6

Here, the IP addresses (A records) are given for the two name

servers for this domain. These records will time out

in 13 hours, 31 minutes, 29 seconds each (the

13h31m29s).

These IP addresses are the ones that will be

connected to when the next lookup for this domain is

performed.

After the introductory commentary, and the informational sections, the dig(1) program summarizes what it did:

;; Total query time: 1866 msec ;; FROM: your.host.domain to SERVER: default -- 127.0.0.1 ;; WHEN: Fri Oct 13 14:46:06 2006 ;; MSG SIZE sent: 29 rcvd: 109

Reverse Look-Up IP Addresses with dig(1)

Normally, dig(1) is used to look up hosts by name, that is, find the IP address that corresponds to the hostname. This is called a forward lookup. A reverse lookup, instead, starts with the IP address and seeks to find the hostname that belongs to it.

To reverse-look-up IP addresses you use dig(1) with

the -x

command-line switch:

dig -x address

In the following example, we will also use the

+noall,

+question, and

+answer

command-line arguments to limit dig(1)’s reply to

just the items we are interested in. The +noall tells dig(1) to

print nothing. The +question and +answer tell dig(1) to print only the

question and answer sections:

% dig +noall +question +answer -x 192.0.34.166

;166.34.0.192.in-addr.arpa. IN PTR

166.34.0.192.in-addr.arpa. 20341 IN PTR www.example.com.Note that because -x specifies an IP address, the IP

address must immediately follow it. Here, dig(1) produced just

two lines of output. The first line (a comment line)

is the original question that was asked. That line

is followed by the answer line.

You might reasonably ask, however, where did the

in-addr.arpa

come from? In the halcyon days of yore, there was no

dig(1) program; hence, there was no easy way to look

up a host by its address. In order to look up the

address, you first had to reverse it (hence, a

reverse lookup) and then to append an in-addr.arpa to the

result:

192.0.34.166 reverses to 166.34.0.192.in-addr.arpa

Internally, dig(1) performs this task for you, thus causing your question to look different from your command line. In summary, then, the following two dig(1) commands perform the same lookup,[159] but the second is easier to use:

% dig ptr 166.34.0.192.in-addr.arpa % dig -x 192.0.34.166

Finally, note that forward lookups and reverse lookups don’t always agree. This is especially true when a host is connected to a satellite or DSL line. Consider, for example, the following three commands:

% dig +noall +answer mypc.example.com mypc.example.com. 3600 IN A 192.168.45.55 % dig +noall +answer -x 192.168.45.55 55.45.168.192.in-addr.arpa 3600 IN PTR dhcphost12.isp.domain % dig +noall +answer dhcphost12.isp.domain dhcphost12.isp.domain 3600 IN A 192.168.45.55

Here, the host mypc.example.com is looked up, yielding its IP address. Next, that IP address is reverse-looked-up, but instead of yielding mypc.example.com as expected, it yields dhcphost12.isp.domain. This is a simplified example of a PC in someone’s home connected to a telephone company’s DSL service. Note that when this new hostname is looked up, that lookup reveals the original IP address.

Although such false or misleading lookups may seem dishonest, there is actually no restriction in the RFCs against them.

Look Up MX Records with dig(1)

Recall that an MX record is a Mail eXchanger record.

MX records list the hosts that should receive email

for a host or a domain. A handy way to look up MX

records with dig(1) is to use

its +short

command-line argument and pipe the result through

sort(1):

% dig +short mx example.gov | sort -n 5 amx.example.gov. 5 bmx.example.gov. 5 cmx.example.gov. 100 backup1.example.gov. 100 backup2.example.gov.

Here, a +short

argument limits output to just brief answers, the

cost and hostnames found as MX records. The sort(1)

uses -n to sort

numerically, lowest through highest costs.

This example reveals a handy property of MX records. When multiple hosts share the same cost, the rule is to select randomly from among them. That is, in this example, all three of the cost 5 hosts are tried first before any of the cost 100 hosts, but the order in which the cost 5 hosts are tried is random.

Note that we discuss MX records, generally, in Set Up MX Records on page 332, covering their management and associated pitfalls. Here, we have limited our discussion to using dig(1) to look up MX records.

Use a Different Name Server with dig(1)

Normally, dig(1) talks to the name server that is defined in your /etc/resolv.conf file. There will be times, however, when you will need to use a different name server. To illustrate, consider the need to move from one ISP to another. Let’s say your MX records are correct on the old ISP name servers, and you wish to make sure that they are correct on the new name servers before switching over to them. You could change your /etc/resolv.conf file to use the new name servers, but that isn’t advisable until you are certain the new name servers are working correctly. Instead, simply cause dig(1) itself to use the new name servers:

% dig @nameserver host

Here, the @ is

immediately followed by the hostname or IP address

of the name server to use instead of the default.

The dig(1) program will perform its lookups directly

using the name servers specified. Consider:

% dig +short mx your.domain 0 mail.your.domain 10 mail2.your.domain % dig +short @123.45.67.89 your.domain 1 mailserver.new.isp 10 mail.your.domain

Here, we first look up the local domain using the

current name servers (there is no @ argument) and find

that the output from dig(1) is correct. We then look

up the local domain at the new name server using its

IP address (the @123.45.67.89) and discover that they are

set up incorrectly. This discovery gives you time to

fix your MX records on the new name servers before

you actually switch services to them.

Pitfalls

When sendmail finds multiple A or AAAA records for a host (and no MX records), it tries them in the order returned by DNS, but looks up and uses AAAA before A records. If

sortlistis specified in the /etc/resolv.conf file, DNS returns the A or AAAA record that is on the same network first. The sendmail program assumes that DNS returns addresses in a useful order. If the address that sendmail always tries first is not the most appropriate, look for problems with DNS, not with sendmail.If you misunderstand the

TryNullMXListoption (TryNullMXList on page 1112) and mistakenly set it to true under the wrong circumstances, you might one day suddenly discover many queued messages from outside your site destined for some host you’ve never heard of before.Under old versions of DNS, an error in the zone file causes the rest of the file to be ignored. The effect is as though many of your hosts suddenly disappeared. This problem has been fixed in V4.9.x.

Sites with a central mail hub should give that hub the role of a caching secondary DNS server. If /etc/resolv.conf contains the address of

localhostas its first record, lookups will be much faster. Failure to make the mail hub any sort of DNS server runs the risk of mail failing and queueing when the hub is up but the other DNS servers are down or unreachable.[160]Prior to V8.8 sendmail, the maximum number of MX records that could be listed for a single host was 20. Some sites, such as aol.com, might reach that limit soon and exceed it. Beginning with V8.8 sendmail, that maximum has been increased to 100.

Some older versions of BIND, after running for a long while, can get into an odd state where they return a temporary error for a failed MX lookup, when in fact the host does not have an MX record. This faulty return causes sendmail to queue the message instead of delivering it to the A or AAAA record address as it should. If you find a host queued that shows a “hostname lookup” error, and you know for sure that the host has no MX record but it does have a good A or AAAA record, consider restarting your name server software, or upgrading to a newer version.

If you use name servers that are outside your direct control, such as when connected to a large ISP, you should make it a point to periodically verify that your host and IP address lookups work as expected. A mistake at their end can make your outbound or inbound mail suddenly fail and continue to fail for however long it takes them to fix their problem, possibly days. If you can ping(1) outside sites, but just cannot look up addresses, consider placing the address of a friendly alternative[161] name server in your /etc/resolv.conf file for the down interval. Just be sure to change it back when the problem is fixed.

Some sites do not properly set up firewall screening for port 53, the port used by DNS. Some sites open port 53 only for UDP traffic, when instead they should open it for both UDP and TCP traffic. When DNS does a lookup, it is possible for the reply to be too big to fit into a UDP packet. When this happens, the lookup is performed a second time using TCP because TCP can hold arbitrarily large amounts of data. Firewalls misconfigured in this way can cause odd DNS lookup failures.

[147] * It is included under some circumstances to prevent the local domain from being accidently appended improperly.

[148] † Actually, there are several machines named a.root-servers.net, b.root-servers.net, and so on.

[149] ‡ There is also a type of server called “caching.” This type doesn’t originate information about domains but is able to look up and save information and to supply it on request.

[150] * Technically, this field is called the preference. We use cost to clarify that lower values are preferable, whereas preference wrongly connotes that higher values are preferable.

[151] * Prior to V8

sendmail, the canonical name

was stored in the $w macro ($w on

page 850) and sendmail

initialized only the $j macro ($j on

page 830). Beginning with V8,

sendmail initializes both of

those variables, among others (Preassigned sendmail Macros on page

785).

[152] * Note that this is broken in many older versions of sendmail. Also note that when the MX record points to the local host, all MX records with a cost greater than or equal to the local host are tossed. (See $w on page 850 for a description of this process.)

[153] * And if sendmail was built with the NETINET6 (NET... on page 126) compile-time macro defined.

[154] * Run the whois(1) program to find the email address of the administrator for the site. It should be hostmaster, but often it is not.

[155] * Most of this happens inside the gethostbyname(3) or getipnodebyname(3) C-library routine.

[156] † We are fudging for the sake of simplicity. Here, we assume that all the hosts also have A records.

[157] * As does the

UIUC version of IDA sendmail.

Other versions of IDA (such as KJS) do not. Note

that defining the TryNullMXList option to true has the

undesirable side effect of allowing anyone on the

Internet to use your host as a backup MX server,

without your permission.

[158] * Especially if you are used to nslookup(1), which is very terse.

[159] * Some versions

of dig(1) use

a PTR lookup for -x, whereas other use an ANY

lookup.

[160] * This caveat applies only for medium to small sites. At large-volume mail sites, the volume of memory consumed by a long-running name server can adversely impact the benefit of running that name server on the same host as sendmail. At large sites, redundant, dedicated name servers should run on separate machines on the local network.

[161] † We use the vague term “friendly alternative” because you should not just presume to use any name server you want. Try telephoning the local college or a large business and asking if you can point your resolv.conf at them for a couple of days until the problem is fixed. They will probably say yes.