The problem tackled in this chapter is a particularly hard one. Yet, by suitably decomposing the problem combined with effective reasoning skills, the problem becomes solvable.

The problem is to find a Knight’s circuit of a chessboard. That is, find a sequence of moves that will take a Knight in a circuit around all the squares of a chessboard, visiting each square exactly once, and ending at the square at which the circuit began.

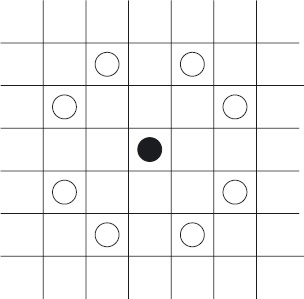

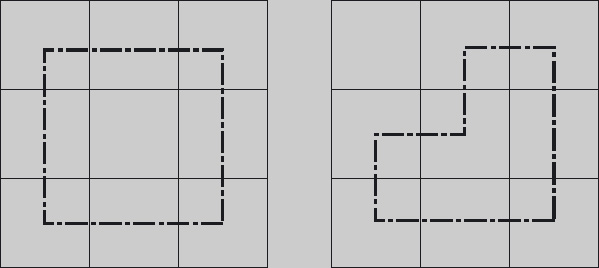

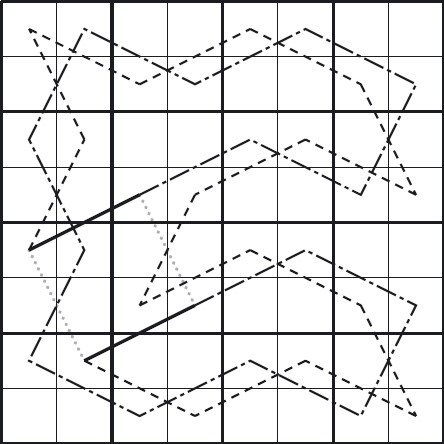

The problem is an instance of a search problem; in principle, it can be solved by a systematic, exhaustive examination of all the paths a Knight can follow around a chessboard – a brute-force search. However, there are 64 squares on a chessboard; that means 64 moves have to be chosen, one for each square. From each of the corner squares, there is a choice of just 2 moves, but from each of the 16 central squares, there is a choice of 8 moves (see Figure 11.1); from the remaining squares either 4 or 6 moves are possible. This gives a massive amount of choice in the paths that can be followed. Lots of choice is usually not a problem but, when combined with the very restrictive requirement that the path forms a circuit that visits every square exactly once, it does become a problem. The Knight’s circuit problem is hard because of this critical combination of an explosion with an implosion of choice.

But, all is not lost. The squares on a chessboard are arranged in a very simple pattern, and the Knight’s moves, although many, are specified by one simple rule (two squares horizontally or vertically, and one square in the opposite direction). There is a great deal of structure, which we must endeavour to exploit.

Figure 11.1: Knight’s moves.

Figure 11.1: Knight’s moves.

11.1 STRAIGHT-MOVE CIRCUITS

Finding a Knight’s circuit is too difficult to tackle head on. Some experience of tackling simpler circuit problems is demanded.

Let’s turn the problem on its head. Suppose you want to make a circuit of a chessboard and you are allowed to choose a set of moves that you are allowed to make. What sort of moves would you choose?

The obvious first answer is to allow moves from any square to any other square. In that case, it’s always possible to construct a circuit of any board, whatever its size – starting from any square, choose a move to a square that has not yet been visited until all the squares are exhausted; then return to the starting square. But that is just too easy. Let’s consider choosing from a restricted set of moves.

The simplest move is one square horizontally or vertically. (These are the moves that a King can make, but excluding diagonal moves.) We call these moves straight moves. Is it possible to make a circuit of a chessboard just with straight moves?

The answer is yes, although it isn’t immediately obvious. You may be able to find a straight-move circuit by trial and error, but let us try to find one more systematically. As is often the case, it is easier to solve a more general problem; rather than restrict the problem to an 8×8 board, let us consider an arbitrary rectangular board. Assuming each move is by one square only, to the left or right, or up or down, is it possible to complete a straight-move circuit of the entire board? That is, is it possible to visit every square exactly once, beginning and ending at the same square, making “straight” moves at each step?

In order to gain some familiarity with the problem, please tackle the following exercise. Its solution is relatively straightforward.

(a) What is the relation between the number of moves needed to complete a circuit of the board and the number of squares? Use your answer to show that it is impossible to complete a circuit of the board if both sides have odd length. (Hint: crucial is that each move is from one square to a different coloured square. Otherwise, the answer does not depend on the sort of moves that are allowed.)

(b) For what values of m is it possible to complete a straight-move circuit of a board of size 2m×1? (A 2m×1board has one column of squares; the number of squares is 2m.)

(c) Show that it is possible to complete a straight-move circuit of a 2×n board for all (positive) values of n. (A 2×n board has two rows, each row having n squares.)

The conclusion of exercise 11.1 is that a straight-move circuit is only possible if the board has size 2m×n, for positive numbers m and n. That is, one side has length 2m and the other has length n. (Both m and n must be non-zero because the problem assumes the existence of at least one starting square.) Also, a straight-move circuit can always be completed when the board has size 2×n, for positive n. This suggests that we now try to construct a straight-move circuit of a 2m×n board, for m at least one and n greater than one, by induction on m, the 2×n case providing the basis for the inductive construction.

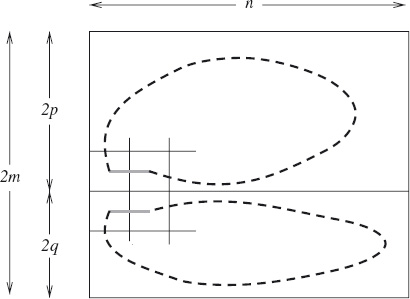

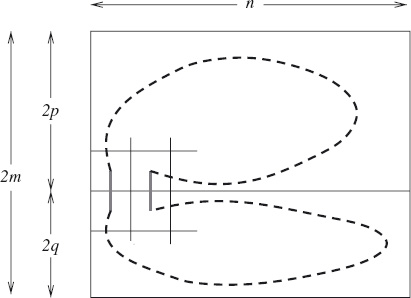

To complete the inductive construction, we need to consider a board of size 2m × n, where m is greater than 1. Such a construction is hopeful because, when m is greater than 1, a 2m × n board can be split into two boards of sizes 2p × n and 2q × n, say, where both p and q are smaller than m and p+q equals m. We may take as the inductive hypothesis that a straight-move circuit of both boards can be constructed. We just need to combine the two constructions.

In our description of the solution below, we use the convention that the first component of the size of a board gives the number of rows and the second the number of columns.

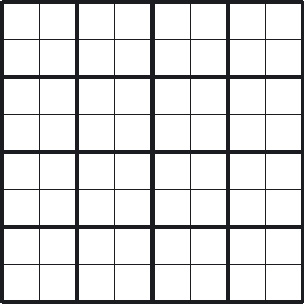

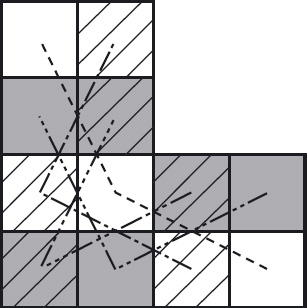

The key to the combination is the corner squares. There are two straight moves from each of the corner squares, and any straight-move circuit must use both. In particular, it must use the horizontal moves. Now, imagine that a 2m × n board is divided into a 2p × n board and a 2q × n board, with the former above the latter. The bottom-left corner of the 2p × n board is immediately above the top-left corner of the 2q × n board. Construct straight-move circuits of these two boards. Figure 11.2 shows the result diagrammatically. The two solid horizontal lines at the middle-left of the diagram depict moves that we know must form part of the two circuits. The dashed lines depict the rest of the circuits. (Of course, the shape of the dashed lines gives no indication of the shape of the circuit that is constructed.)

Figure 11.2: Combining straight-move circuits. First, split the board into two smaller boards and construct straight-move circuits of each.

Figure 11.2: Combining straight-move circuits. First, split the board into two smaller boards and construct straight-move circuits of each.

Now, to combine the circuits to form one circuit of the entire board, replace the horizontal moves from the bottom-left and top-left corners by vertical moves, as shown by the vertical solid lines in Figure 11.3. This completes the construction.

Figure 11.3: Second, combine the two circuits as shown.

Figure 11.3: Second, combine the two circuits as shown.

Figure 11.4 shows the circuit that is constructed in this way for a 6 × 8 board. Effectively, the basis of the inductive algorithm constructs straight-move circuits of three 2 × 8 boards. The induction step then combines them by replacing horizontal moves by the vertical moves shown in Figure 11.4.

Figure 11.4: A straight-move circuit for a 6 × 8 board.

Figure 11.4: A straight-move circuit for a 6 × 8 board.

Exercise 11.2 As mentioned above, when a board has an odd number of squares, no circuit is possible.

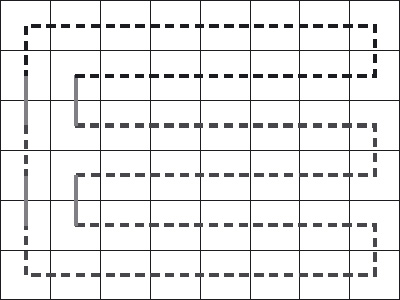

Consider a 3×3 board. It is easy to construct a straight-move circuit of all its squares but the middle square. (See Figure 11.5.) It is also possible to construct a straight-move circuit of all its squares but one of the corner squares. However, a straight-move circuit of all but one of the other four squares – the squares adjacent to a corner square, for example, the middle-left square – cannot be constructed.

Figure 11.5: Straight-move circuits of a 3 × 3 board, omitting one of the squares.

Figure 11.5: Straight-move circuits of a 3 × 3 board, omitting one of the squares.

Explore when it is possible, and when it is not possible, to construct a straight-move circuit of all the squares but one in a board of odd size.

11.2 SUPERSQUARES

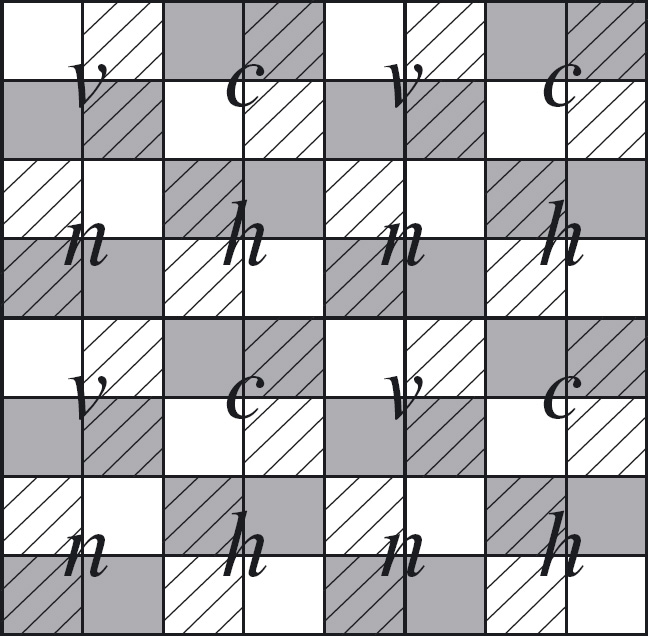

Let us now return to the Knight’s-circuit problem. The key to a solution is to exploit what we know about straight moves. The way this is done is to imagine that the 8 × 8 chessboard is divided into a 4 × 4 board by grouping together 2 × 2 squares into “supersquares”, as shown in Figure 11.6.

Figure 11.6: Chessboard divided into a 4 × 4 board of supersquares.

Figure 11.6: Chessboard divided into a 4 × 4 board of supersquares.

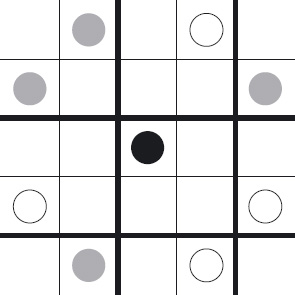

If this is done, the Knight’s moves can be classified into two types: Straight moves are moves that are “straight” with respect to the supersquares; that is, a Knight’s move is straight if it takes it from one supersquare to another supersquare either vertically above or below, or horizontally to the left or to the right. Diagonal moves are moves that are not straight with respect to the supersquares; a move is diagonal if it takes the Knight from one supersquare to another along one of the diagonals through the starting supersquare. In Figure 11.7, the boundaries of the supersquares are indicated by thickened lines; the starting position of the Knight is shown in black, the straight moves are to the white positions, and the diagonal moves are to the grey positions.

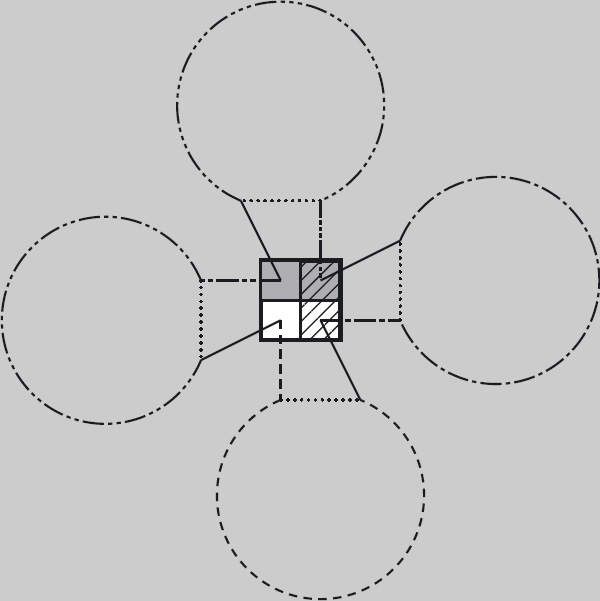

Focusing on the straight moves, we now make a crucial observation. Figure 11.8 shows the straight moves from one supersquare – the bottom-left supersquare – vertically upwards and horizontally rightwards. The “colours” (the combination of stripes and shading) indicate the moves that can be made. For example, from the bottom-left white square a straight move can be made to the top-left white square or to the bottom-right white square. However, it is not possible to move from a square to another square of a different “colour”.

Figure 11.7: Straight (white) and diagonal (grey) knight’s moves from some starting position (black). Boundaries of the supersquares are indicated by thickened lines.

Figure 11.7: Straight (white) and diagonal (grey) knight’s moves from some starting position (black). Boundaries of the supersquares are indicated by thickened lines.

Figure 11.8: Straight moves from the bottom-left supersquare.

Figure 11.8: Straight moves from the bottom-left supersquare.

Observe the pattern. Vertical moves flip the “colours” around a vertical axis, whilst horizontal moves flip them around a horizontal axis. (The vertical moves interchange striped and not-striped squares; the horizontal moves interchange shaded and not-shaded squares.)

Let us denote by v the operation of flipping the columns of a 2 × 2 square (v is short for “vertical”). Similarly, let us denote by h (short for “horizontal”) the operation of flipping the rows of the square. Now, let an infix semicolon denote doing one operation after another. So, for example, v ; h denotes the operation of first flipping the columns and then flipping the rows of the square. Flipping the columns and then flipping the rows is the same as flipping the rows and then the columns. That is,

v ; h = h ; v.

Both are equivalent to rotating the 2 × 2 square through 180° about its centre. So, let us use c (short for “centre”) as its name. That is, by definition of c,

We have now identified three operations on a 2 × 2 square. There is a fourth operation, which is the do-nothing operation. Elsewhere, we have used skip to name such an operation. Here, for greater brevity we use n (short for “no change”). Flipping twice vertically, or twice horizontally, or rotating twice through 180° about the centre, all amount to doing nothing. That is;

Also, doing nothing before or after any operation is the same as doing the operation.

The three equations (11.3), (11.4) and (11.5), together with the fact that doing one operation after another is associative (that is, doing one operation x followed by two operations y and z in turn is the same as doing first x followed by y and then concluding with z – in symbols, x ; (y ; z) = (x ; y) ; z) allow the simplification of any sequence of the operations to one operation. For example,

v; c; h

= { v; h = c }

v; v; h; h

= { v; v = h; h = n }

n; n

= { n; x = x, with x:= n }

n.

In words, flipping vertically, then rotating through 180° about the centre, and then flipping horizontally is the same as doing nothing. (Note how associativity is used implicitly between the first and second steps. The use of an infix operator for “followed by” facilitates this all-important calculational technique.)

Exercise 11.6 Construct a two-dimensional table that shows the effect of executing two operations x and y in turn. The table should have four rows and four columns, each labelled by one of n, v, h and c. (Use the physical process of flipping squares to construct the entries.)

Use the table to verify that, for x and y in the set {n,v,h,c},

Check also that, for x and y in the set {n,v,h,c},

(In principle, you need to consider 43, i.e. 64, different combinations. Think of ways to reduce the amount of work.)

Exercise 11.9 Two other operations that can be done on a 2 × 2 square are to rotate it about the centre through 90°, in one case clockwise and in the other anticlockwise. Let r denote the clockwise rotation and let a denote the anticlockwise rotation. Construct a table that shows the effect of performing any two of the operations n, r, a or c in sequence.

11.3 PARTITIONING THE BOARD

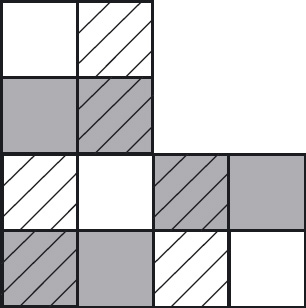

The identification of the four operations on supersquares is a significant step towards solving the Knight’s-circuit problem. Suppose one of the supersquares is labelled “n”. Then the remaining fifteen supersquares can be uniquely labelled as n, v, h or c squares, depending on their position relative to the starting square. Figure 11.9 shows how this is done. Suppose we agree that the bottom-left square is an “n” square. Then immediately above it is a “v” square, to the right of it is an “h” square, and diagonally adjacent to it is a “c” square. Supersquares further away are labelled using the rules for composing the operations.

As a consequence, all 64 squares of the chessboard are split into four disjoint sets. In Figure 11.9, the different sets are easily identified by the colour of the square1. Two squares have the same colour equivales they can be reached from each other by straight Knight’s moves. (That is, two squares of the same colour can be reached from each other by straight Knight’s moves, and two squares of different colour cannot be reached from each other by straight Knight’s moves.)

Figure 11.9: Labelling supersquares.

Figure 11.9: Labelling supersquares.

Recall the discussion of straight-move circuits in section 11.1. There we established the simple fact that it is possible to construct a straight-move circuit of a board of which one side has even length and the other side has length at least two. In particular, we can construct a straight-move circuit of a 4 × 4 board.

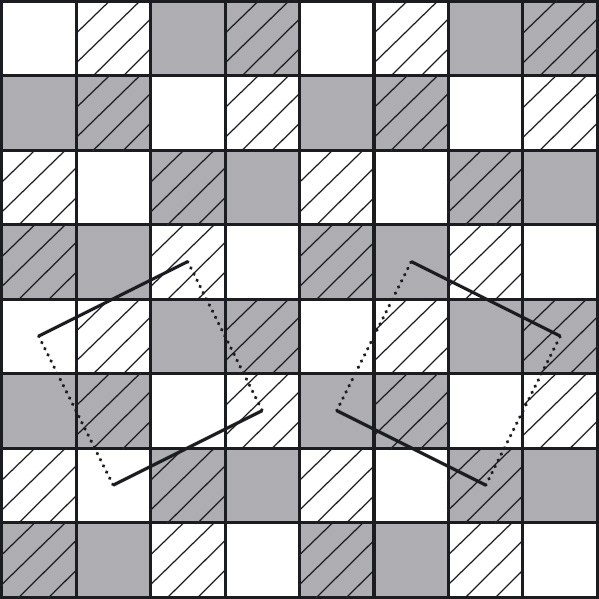

Now, a “straight” Knight’s move is “straight” with respect to the supersquares of a chessboard. That means we can construct straight-move circuits of each of the four sets of squares on the chessboard. In Figure 11.9, this means constructing a circuit of all the white squares, a circuit of all the striped squares, a circuit of all the shaded squares, and a circuit of all the shaded-and-striped squares. Figure 11.10 shows how we distinguish the four different circuits. Specifically, moves connecting white squares are shown as 0-dot, dashed lines, moves connecting striped squares are shown as 1-dot, dashed lines, moves connecting shaded squares are shown as 2-dot, dashed lines, and moves connecting shaded-and-striped squares are shown as 3-dot, dashed lines.

Figure 11.10: Moves from the bottom-left supersquare. The number of dots (0, 1, 2 or 3) corresponds to the “colour” of connected squares (white, striped, shaded and striped-and-shaded).

Figure 11.10: Moves from the bottom-left supersquare. The number of dots (0, 1, 2 or 3) corresponds to the “colour” of connected squares (white, striped, shaded and striped-and-shaded).

We now have four disjoint circuits that together visit all the squares of the chessboard. The final step is to combine the circuits into one. The way to do this is to exploit the “diagonal” Knight’s moves. (Refer back to Figure 11.7 for the meaning of “diagonal” in this context.)

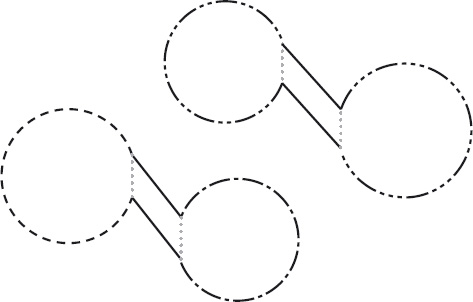

A simple way of combining the four circuits is to combine them in pairs, and then combine the two pairs. For example, we can combine the circuits of the white and striped squares into a “non-shaded” circuit of half the board; similarly, we can combine the circuits of the shaded and shaded-and-striped squares into a “non-white” circuit. Finally, by combining the non-shaded and non-white circuits, a complete circuit of the board is obtained.

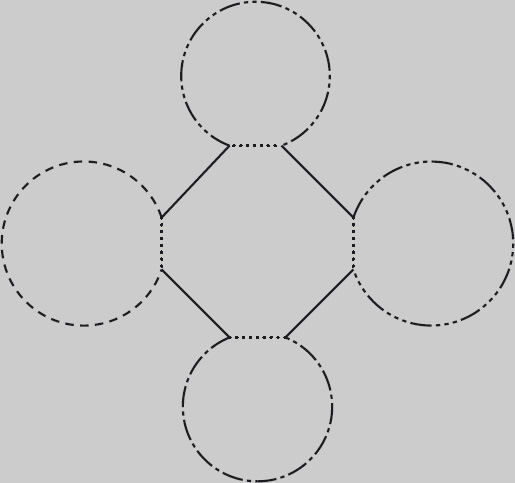

Figure 11.11 shows schematically how non-shaded and non-white circuits are formed; in each case, two straight moves (depicted by dotted lines) in the respective circuits are replaced by diagonal moves (depicted by solid lines). Figure 11.12 shows one way of choosing the straight and diagonal moves in order to combine striped and white circuits, and shaded and shaded-and-striped circuits – in each case, two “parallel” straight moves are replaced by two “parallel” diagonal moves. Exploiting symmetry, it is easy to find similar “parallel moves” with which to combine striped and shaded-and-striped circuits, or shaded and white circuits. On the other hand, there are no diagonal moves from striped to shaded, or from shaded-and-striped to white squares; consequently, it is impossible to construct a “non-striped” or a “non-plain” circuit.

Figure 11.11: Schema for forming “non-shaded” and “non-white” circuits. The straight-move circuits are depicted as circles, a single move in each being depicted by a dotted line. These straight moves are replaced by the diagonal moves, shown as solid lines.

Figure 11.11: Schema for forming “non-shaded” and “non-white” circuits. The straight-move circuits are depicted as circles, a single move in each being depicted by a dotted line. These straight moves are replaced by the diagonal moves, shown as solid lines.

Striped and white straight-move circuits have been combined in Figure 11.13 to form a “non-shaded” circuit. The method of combination is indicated by the dotted and solid lines: the straight moves (dotted lines) are replaced by diagonal moves (solid lines). To complete a circuit of the whole board, with this “non-shaded” circuit as basis, a “non-white” circuit has to be constructed, and this circuit combined with the “non-shaded” circuit. This is left as an exercise.

A slight difficulty of this method is that it constrains the straight-move circuits that can be made. For example, considering the suggested method for combining striped and white circuits in Figure 11.12, no constraint is placed on the white circuit (because there is only one way a straight-move circuit of the white squares can enter and leave the bottom-left corner of the board). However, the straight-move circuit of the striped squares is constrained by the requirement that it make use of the move shown as a dotted line. The difficulty is resolved by first choosing the combining moves and then constructing the straight-move circuits appropriately.

Figure 11.12: Forming circuits of the “non-shaded” and “non-white” squares. The straight moves shown as dotted lines are replaced by the diagonal moves shown as solid lines.

Figure 11.12: Forming circuits of the “non-shaded” and “non-white” squares. The straight moves shown as dotted lines are replaced by the diagonal moves shown as solid lines.

In order to construct a Knight”s circuit of smaller size boards, the different pairs of combining moves need to be positioned as close as possible together. This is possible in the case of an 8 × 6 board, but not for smaller boards.

Exercise 11.10 Construct a Knight’s circuit of an 8 × 8 board using the scheme discussed above. Do the same for an 8 × 6 board. Indicate clearly how the individual circuits have been combined to form the entire circuit.

Exercise 11.11 Figure 11.14 illustrates another way that the circuits can be combined. The four straight-move circuits are depicted as circles, one segment of which has been flattened and replaced by a dotted line. The dotted lines represent straight moves between consecutive points. If these are replaced by diagonal moves (represented in the diagram by solid black lines), the result is a circuit of the complete board.

To carry out this plan, the four diagonal moves in Figure 11.14 have to be identified. The key to doing this with a minimum of effort is to seek parallel striped and shaded moves, and parallel white and shaded-and-striped moves, whilst exploiting symmetry. (In contrast, the above solution involved seeking parallel striped and white moves.) Choosing to start from, say, the pair of shaded moves in the bottom-left corner, severly restricts the choice of diagonal moves; in combination with symmetry, this makes the appropriate moves easy to find.

Construct a knight’s circuit of an 8 × 8 and a 6 × 8 board using the above scheme. Explain how to extend your construction to any board of size 4m × 2n for any m and n such that m≥2 and n≥3.

(The construction of the circuit is easier for an 8 × 8 board than for a 6 × 8 board because, in the latter case, more care has to be taken in the construction of the straight-move circuits. If you encounter difficulties, try turning the board through 90° whilst maintaining the orientation of the combining moves.)

Figure 11.13: A circuit of the “non-shaded” squares. Parallel straight moves, shown as thicker dotted lines, are replaced by parallel diagonal moves, shown as thicker solid lines, thus combining the two circuits.

Figure 11.13: A circuit of the “non-shaded” squares. Parallel straight moves, shown as thicker dotted lines, are replaced by parallel diagonal moves, shown as thicker solid lines, thus combining the two circuits.

Figure 11.14: Schema for Combining Straight-Move Circuits. Four straight moves (indicated by dotted lines) are replaced by four diagonal moves (indicated by solid black lines).

Figure 11.14: Schema for Combining Straight-Move Circuits. Four straight moves (indicated by dotted lines) are replaced by four diagonal moves (indicated by solid black lines).

Exercise 11.12 Division of a board of size (4m + 2) × (4n + 2) into supersquares yields a (2m + 1) × (2n + 1) “super” board. Because this superboard has an odd number of (super) squares, no straight-move circuit is possible, and the strategy used in exercise 11.10 is not applicable. However, it is possible to construct Knight”s circuits for boards of size (4m + 2) × (4n + 2), whenever both m and n are at least 1, by exploiting exercise 11.2.

The strategy is to construct four straight-move circuits of the board omitting one of the supersquares. (Recall exercise 11.2 for how this is done.) Then, for each circuit, one move is replaced by two moves – a straight move and a diagonal move – both with end points in the omitted supersquare. This scheme is illustrated in Figure 11.15.

Complete the details of this strategy for a 6 × 6 board. Make full advantage of the symmetry of a 6 × 6 board. In order to construct the twelve combining moves depicted in Figure 11.15, it suffices to construct just three; the remaining nine can be found by rotating the moves through a right angle.

Figure 11.15: Strategy for Constructing a Knight’s Circuit of (4m + 2) × (4n + 2) boards. One supersquare is chosen, and four straight-move circuits are constructed around the remaining squares. These are then connected as shown.

Figure 11.15: Strategy for Constructing a Knight’s Circuit of (4m + 2) × (4n + 2) boards. One supersquare is chosen, and four straight-move circuits are constructed around the remaining squares. These are then connected as shown.

Explain how to use your solution for the 6 × 6 board to construct Knight”s circuits of any board of size (4m + 2) × (4n + 2), whenever, both m and n are at least 1.

11.4 SUMMARY

In the absence of a systematic strategy, the Knight’s circuit problem is a truly difficult problem to solve, which means it is a very good example of disciplined problem-solving skills. The method we have used to solve the problem is essentially problem decomposition – reducing the Knight’s circuit problem to constructing straight-move circuits, and combining these together.

The key criterion for a good method is whether or not it can be extended to other related problems. This is indeed the case for the method we have used to solve the Knight’s circuit problem. The method has been applied to construct a circuit of an 8 × 8 chessboard, but the method can clearly be applied to much larger chessboards.

The key ingredients are

- the classification of moves as “straight” or “diagonal”,

- straight-move circuits of supersquares, and

- using diagonal moves to combine straight-move circuits.

Once the method has been fully understood, it is easy to remember these ingredients and reproduce a Knight’s circuit on demand. Contrast this with remembering the circuit itself, which is obviously highly impractical, if not impossible.

A drawback of the method is that it can only be applied to boards that can be divided into supersquares. As we have seen, it is not possible to construct a Knight’s circuit of a board with an odd number 7 of squares. That leaves open the cases where the board has size (2m) × (2n + 1), for some m and n. (That is, one side has even length and the other has odd length.) There are lots of websites where information on this case can be obtained; a couple are mentioned in section 11.5.

The Knight’s-circuit problem exemplifies a number of mathematical concepts discussed in part II. The n, v, h and c operations together form an example of a “group”: see definition 12.22 in section 12.5.6. The relation on squares of being connected by straight moves is an example of an “equivalence relation”, and the fact that this relation partitions the squares into four disjoint sets is an example of a general theorem about equivalence relations: see section 12.7.8.

The Knight’s-circuit problem is an instance of a general class of problems called “Hamiltonian-Circuit Problems”. In general, the input to a Hamiltonian-circuit problem is a graph (a network of nodes with edges connecting the nodes: see chapter 16) and the requirement is to find a path through the graph that visits each node exactly once, before returning to the starting node. Hamiltonian-circuit problems are, in turn, instances of a class of problems called “NP-complete” problems. NP-complete problems are problems characterised by ease of verification but difficulty of construction. That is, given a putative solution, it is easy to check whether or not it is correct (for example, given any sequencing of the squares on a chessboard, it is easy to check whether or not it is a Knight’s circuit); however, for the class of NP-complete problems, no efficient methods are known at this time for constructing solutions. “Complexity theory” is the name given to the area of computing science devoted to trying to quantify how difficult algorithmic problems really are.

11.5 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REMARKS

Solutions and historical information on the Knight”s circuit problem can easily be found on the internet. According to one of these [MacQuarrie, St. Andrews Univ.] the first Knight’s tour is believed to have been found by al-Adli ar-Rumni in the ninth century, long before chess was invented.

I learnt about the use of supersquares in solving the Knight’s circuit problem from Edsger W. Dijkstra [Dij92]. Dijkstra’s solution is for a standard-sized chessboard and uses the method of combining straight-move circuits described in exercise 11.11. The pairwise combination of straight-move circuits was suggested by Diethard Michaelis. Both solutions involve searching for “parallel moves”. Michaelis’s solution is slightly preferable because just two pairs of “parallel moves” have to be found at each stage. Dijkstra’s solution involves searching for four pairs (twice as many) at the same time, making it a little bit harder to do. The solution to exercise 11.12 was constructed by the author, with useful feedback from Michaelis.

Since first writing this chapter (in 2003), I have learnt that the use of supersquares was devised by Peter Mark Roget (better known for his Thesaurus) in 1840. According to George Jelliss [google “Knight’s Tours”], H.J.R.Murray introduced the terminology “straights” and “slants” for the two types of move in a book entitled History of Chess and published in 1913. Jellis’s website gives an encyclopaedic account of Knight’s tours and Knight’s circuits.

1Because we are unable to use true colours, like red and blue, we use “colour” to refer to the different combinations of shaded/not-shaded and striped/not-striped.