The topic of this chapter is a problem that is discussed in many books on recreational mathematics and often used in computing science and artificial intelligence as an illustration of “recursion” as a problem-solving strategy.

The Tower of Hanoi problem is quite difficult to solve without a systematic problem-solving strategy. Induction gives a systematic way of constructing a first solution. However, this solution is undesirable. A better solution is obtained by observing an invariant of the inductive solution. In this way, this chapter brings together a number of the techniques discussed earlier: principally induction and invariants, but also the properties of logical equivalence.

For this problem, we begin with the solution of the problem. One reason for doing so is to make clear where we are headed; the Tower of Hanoi problem is one that is not solved in one go – several steps are needed before a satisfactory solution is found. Another reason is to illustrate how difficult it can be to understand why a correct solution has been found if no information about the solution method is provided.

8.1 SPECIFICATION AND SOLUTION

8.1.1 The End of the World!

The Tower of Hanoi problem comes from a puzzle marketed in 1883 by the French mathematician Édouard Lucas, under the pseudonym M. Claus.

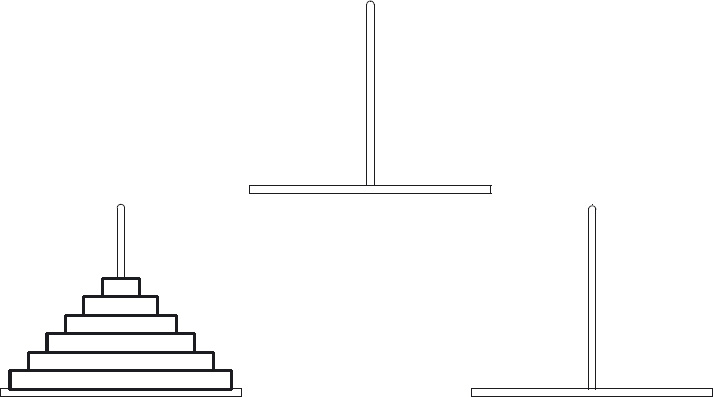

The puzzle is based on a legend according to which there is a temple in Brahma where there are three giant poles fixed in the ground. On the first of these poles, at the time of the world’s creation, God placed 64 golden discs, each of different size, in decreasing order of size (see Figure 8.1). The monks were given the task of moving the discs, one per day, from one pole to another according to the rule that no disc may ever be above a smaller disc.

The monks’ task would be complete when they succeeded in moving all the discs from the first of the poles to the second and, on the day that they completed their task, the world would come to an end!

Figure 8.1: Tower of Hanoi problem.

Figure 8.1: Tower of Hanoi problem.

8.1.2 Iterative Solution

There is a very easy solution to the Tower of Hanoi problem that is easy to remember and easy to execute. To formulate the solution, we assume that the poles are arranged at the three corners of a triangle. Movements of the discs can then be succinctly described as either clockwise or anticlockwise movements. We assume that the problem is to move all the discs from one pole to the next in a clockwise direction. We also assume that days are numbered from 0 onwards. On day 0, the discs are placed in their initial position and the monks begin moving the discs on day 1. With these assumptions, the solution is the following.

On every alternate day, beginning on the first day, the smallest disc is moved. The rule for moving the smallest disc is that it should cycle around the poles. The direction of rotation depends on the total number of discs. If the total number of discs is odd, the smallest disc should cycle in a clockwise direction. Otherwise, it should cycle in an anticlockwise direction.

On every other day, a disc other than the smallest disc is moved – subject to the rule that no disc may ever be above a smaller disc. It is easy to see that because of this rule there is exactly one move possible so long as not all the discs are on one pole.

The algorithm terminates when no further moves are possible, that is, on an even-numbered day when all the discs are on one and the same pole.

Try executing this algorithm yourself on, say, a 4-disc puzzle. Take care to cycle the smallest disc on the odd-numbered moves and to obey the rule not to place a disc on top of a disc smaller than itself on the even-numbered moves. If you do, you will find that the algorithm works. Depending on how much patience you have, you can execute the algorithm on larger and larger problems – 5-disc, 6-disc, and so on.

8.1.3 Why?

Presenting the problem and its solution, like this, provides no help whatsoever in understanding how the solution is constructed. If anything, it only serves to impress – look at how clever I am! – but in a reprehensible way. Matters would be made even worse if we now proceeded to give a formal mathematical verification of the correctness of the algorithm. This is not how we intend to proceed! Instead, we first present an inductive solution of the problem. Then, by observing a number of invariants, we show how to derive the algorithm above from the inductive solution.

8.2 INDUCTIVE SOLUTION

Constructing a solution by induction on the number of discs is an obvious strategy.

Let us begin with an attempt at a simple-minded inductive solution. Suppose that the task is to move M discs from one specific pole to another specific pole. Let us call these poles A and B, and the third pole C. (Later, we see that naming the poles is inadvisable.)

As often happens, the basis is easy. When the number of discs is 0 no steps are needed to complete the task. For the inductive step, we assume that we can move n discs from A to B, and the problem is to show how to move n+1 discs from A to B.

Here, we soon get stuck! There are only a couple of ways that the induction hypothesis can be used, but these lead nowhere:

- Move the top n discs from A to B. After doing this, we have exhausted all possibilities of using the induction hypothesis because n discs are now on pole B, and we have no hypothesis about moving discs from this pole.

- Move the smallest disc from A to C. Then move the remaining n discs from A to B. Once again, we have exhausted all possibilities of using the induction hypothesis, because n discs are now on pole B, and we have no hypothesis about moving discs from this pole.

The mistake we have made is to be too specific about the induction hypothesis. The way out is to generalise by introducing one or more parameters to model the start and finish positions of the discs.

At this point, we make a crucial decision. Rather than name the poles (A, B and C, say), we observe that the problem exhibits a rotational symmetry. The rotational symmetry is obvious when the poles are placed at the corners of an equilateral triangle, as we did in Figure 8.1. (This rotational symmetry is obscured by placing the poles in a line, as is often done.) The problem does not change when we rotate the poles and discs about the centre of the triangle.

The importance of this observation is that only one additional parameter needs to be introduced, namely, the direction of movement. That is, in order to specify how a particular disc is to be moved, we need only say whether it is to be moved clockwise or anticlockwise from its current position. Also, the generalisation of the Tower of Hanoi problem becomes how to move n discs from one pole to the next in the direction d, where d is either clockwise or anticlockwise. The alternative of naming the poles leads to the introduction of two additional parameters, the start and finish positions of the discs. This is much more complicated since it involves unnecessary additional detail.

Now, we can return to the inductive solution again. We need to take care in formulating the induction hypothesis. It is not sufficient to simply take the problem specification as induction hypothesis. This is because the problem specification assumes that there are exactly M discs that are to be moved. When using induction, it is necessary to move n discs in the presence of M−n other discs. If some of these M−n discs are smaller than the n discs being moved, the requirement that a larger disc may not be placed on top of a smaller disc may be violated. We need a stronger induction hypothesis.

In the case where n is 0, the sequence of moves is the empty sequence. In the case of n+1 discs we assume that we have a method of moving the n smallest discs from one pole to either of its two neighbours. We must show how to move n+1 discs from one pole to its neighbour in direction d, where d is either clockwise or anticlockwise. For convenience, we assume that the discs are numbered from 1 upwards, with the smallest disc being given number 1.

Given the goal of exploiting the induction hypothesis, there is little choice of what to do. We can begin by moving the n smallest discs in the direction d, or in the direction ¬d. Any other initial choice of move would preclude the use of the induction hypothesis. Some further thought (preferably assisted by a physical model of the problem) reveals that the solution is to move the n smallest discs in the direction ¬d. Then disc n+1 can be moved in the direction d. (This action may place disc n+1 on top of another disc. However, the move is valid because the n discs smaller than disc n+1 are not on the pole to which disc n+1 is moved.) Finally, we use the induction hypothesis again to move the n smallest discs in the direction ¬d. This places them above disc n+1, and all n+1 smallest discs have now been moved from their original position to the neighbouring pole in direction d.

The following code summarises this inductive solution to the problem. The code defines Hn(d) to be a sequence of pairs  k, d′

k, d′ where n is the number of discs, k is a disc number and d and d′ are directions. Discs are numbered from 1 onwards, disc 1 being the smallest. Directions are boolean values, true representing a clockwise movement and

where n is the number of discs, k is a disc number and d and d′ are directions. Discs are numbered from 1 onwards, disc 1 being the smallest. Directions are boolean values, true representing a clockwise movement and false an anticlockwise movement. The pair  k , d′

k , d′ means move the disc numbered k from its current position in the direction d′. The semicolon operator concatenates sequences together, “[]” denotes an empty sequence and [x] is a sequence with exactly one element x. Taking the pairs in order from left to right, the complete sequence Hn(d) prescribes how to move the n smallest discs one by one from one pole to its neighbour in the direction d, following the rule of never placing a larger disc on top of a smaller disc:

means move the disc numbered k from its current position in the direction d′. The semicolon operator concatenates sequences together, “[]” denotes an empty sequence and [x] is a sequence with exactly one element x. Taking the pairs in order from left to right, the complete sequence Hn(d) prescribes how to move the n smallest discs one by one from one pole to its neighbour in the direction d, following the rule of never placing a larger disc on top of a smaller disc:

H0(d) = [] ,

Hn+1(d) = Hn(¬d) ; [ n+1, d

n+1, d  ]; Hn(¬d).

]; Hn(¬d).

Note that the procedure name H recurs on the right-hand side of the equation for Hn+1(d). Because of this we have what is called a recursive solution to the problem. Recursion is a very powerful problem-solving technique, but unrestricted use of recursion can be unreliable. The form of recursion used here is limited; describing the solution as an “inductive” solution makes clear the limitation on the use of recursion.

This inductive procedure gives us a way to generate the solution to the Tower of Hanoi problem for any given value of n – we simply use the rules as left-to-right rewrite rules until all occurrences of H have been eliminated. For example, here is how we determine H2(cw). (We use cw and aw, meaning clockwise and anticlockwise, rather than true and false in order to improve readability.)

H2(cw)

= { 2nd equation, n,d := 1,cw }

H1(aw) ; [ 2,

2,cw ] ;H1(

] ;H1(aw)

= { 2nd equation, n,d := 0,aw }

H0(cw) ; [ 1,

1,aw ] ;H0(

] ;H0(cw) ; [ 2,

2,cw ] ;H0(

] ;H0(cw) ; [ 1,

1,aw ] ;H0(

] ;H0(cw)

= { 1st equation }

[] ; [ 1,

1,aw ] ; [] ; [

] ; [] ; [ 2,

2,cw ] ; [] ; [

] ; [] ; [ 1,

1,aw ] ; []

] ; []

= { concatenation of sequences }

[ 1,

1,aw ,

,  2,

2,cw ,

,  1,

1,aw ] .

] .

As an exercise you should determine H3(aw) in the same way. If you do, you will quickly discover that this inductive solution to the problem takes a lot of effort to put into practice. The complete expansion of the equations in the case of n = 3 takes 16 steps, in the case of n = 4 takes 32 steps, and so on. This is not the easy solution that the monks are using! The solution given in Section 8.1.1 is an iterative solution to the problem. That is, it is a solution that involves iteratively (i.e. repeatedly) executing a simple procedure dependent only on the current state. The implementation of the inductive solution, on the other hand, involves maintaining a stack of the sequence of moves yet to be executed. The memory of Brahman monks is unlikely to be large enough to do that!

Exercise 8.1 The number of days the monks need to complete their task is the length of the sequence H64(cw). Let Tn(d) denote the length of the sequence Hn(d). Derive an inductive definition of T from the inductive definition of H. (You should find that Tn(d) is independent of d.) Use this definition to evaluate T0, T1 and T2. Hence, or otherwise, formulate a conjecture expressing Tn as an arithmetic function of n. Prove your conjecture by induction on n.

Exercise 8.2 Use induction to derive a formula for the number of different states in the Tower of Hanoi problem.

Use induction to show how to construct a state-transition diagram that shows all possible states of n discs on the poles, and the allowed moves between states.

Use the construction to show that the above solution optimises the number of times that discs are moved.

Exercise 8.3 (Constant Direction)

(a) Suppose the discs must always be moved in a constant direction, say clockwise. That is, every move of a disc should be clockwise and no anticlockwise moves are allowed.

Use induction to devise an algorithm to move n discs, for arbitrary n, in the direction d. Use the same induction hypothesis as for the standard Tower of Hanoi problem, namely that it is possible to move the n smallest discs – under the new constraints – from one pole to its neighbour in the direction d, beginning from any valid starting position. Since the direction of movement is constant, it suffices to determine the sequence of discs that are moved. For example, to move 2 discs clockwise, the solution is the sequence

[1,1,2,1,1].

(Disc 1 – the smallest disc – is moved twice clockwise, then disc 2 is moved clockwise, and finally disc 1 is moved twice clockwise.)

(b) Now suppose that the direction each disc is moved must be constant, but may differ between discs. Formally, suppose dir is a function from discs to booleans such that, for each n, the direction of movement of disc n is given by dir(n); true means that disc n must always be moved clockwise, and false means that disc n must always be moved anticlockwise. Use induction to devise an algorithm to move n discs, for arbitrary n, in the direction d. (Again it suffices to determine the sequence of discs that are moved.)

8.3 THE ITERATIVE SOLUTION

Recall the iterative solution to the problem, presented in Section 8.1.2. It has two main elements: the first is that the smallest disc cycles around the poles (i.e. its direction of movement is invariantly clockwise or invariantly anticlockwise), the second is that the disc to be moved alternates between the smallest disc and some other disc. In this section, we show how these properties are derived from the inductive solution.

Cyclic Movement of the Discs

In this section, we show that the smallest disc always cycles around the poles. In fact, we do more than this. We show that all the discs cycle around the poles, and we calculate the direction of movement of each.

The key is that, for all pairs  k,d′

k,d′ in the sequence Hn+1(d), the boolean value even(k) ≡ d′ is invariant (i.e. always true or always false). This is a simple consequence of the rule of contraposition discussed in Section 5.4.1. When the formula for Hn+1(d) is applied, the parameter “n+1” is replaced by “n” and “d” is replaced by “¬d”. Since even(n+1) ≡ ¬(even(n)), the value of even(n+1) ≡ d remains constant under this assignment.

in the sequence Hn+1(d), the boolean value even(k) ≡ d′ is invariant (i.e. always true or always false). This is a simple consequence of the rule of contraposition discussed in Section 5.4.1. When the formula for Hn+1(d) is applied, the parameter “n+1” is replaced by “n” and “d” is replaced by “¬d”. Since even(n+1) ≡ ¬(even(n)), the value of even(n+1) ≡ d remains constant under this assignment.

Whether even(k) ≡ d′ is true or false (for all pairs  k , d

k , d in the sequence Hn+1(d)) will depend on the initial values of n and d. Let us suppose these are N and D. Then, for all moves

in the sequence Hn+1(d)) will depend on the initial values of n and d. Let us suppose these are N and D. Then, for all moves  k, d

k, d , we have

, we have

even(k) ≡ d ≡ even(N) ≡ D.

This formula allows us to determine the direction of movement d of disc k. Specifically, if it is required to move an even number of discs in a clockwise direction, all even-numbered discs should cycle in a clockwise direction, and all odd-numbered discs should cycle in an anticlockwise direction. Likewise, if it is required to move an odd number of discs in a clockwise direction, all even-numbered discs should cycle in an anticlockwise direction, and all odd-numbered discs should cycle in a clockwise direction. In particular, the smallest disc (which is odd-numbered) should cycle in a direction opposite to D if N is even, and in the same direction as D if N is odd.

Exercise 8.4 An explorer once discovered the Brahman temple and was able to secretly observe the monks performing their task. At the time of his discovery, the monks had got some way to completing their task, so that the discs were arranged on all three poles. The poles were arranged in a line and not at the corners of the triangle so he was not sure which direction was clockwise and which anticlockwise. However, on the day of his arrival he was able to observe the monks move the smallest disc from the middle pole to the rightmost pole. On the next day, he saw the monks move a disc from the middle pole to the leftmost pole. Did the disc being moved have an even number or an odd number?

Alternate Discs

We now turn to the second major element of the solution, namely that the disc that is moved alternates between the smallest disc and some other disc.

By examining the puzzle itself, it is not difficult to see that this must be the case. After all, two consecutive moves of the smallest disc are wasteful as they can always be combined into one. And two consecutive moves of a disc other than the smallest have no effect on the state of the puzzle. We now want to give a formal proof that the sequence Hn(d) satisfies this property.

Let us call a sequence of numbers alternating if it has two properties. The first property is that consecutive elements alternate between one and a value greater than one; the second property is that if the sequence is non-empty then it begins and ends with the value one. We write alt(ks) if the sequence ks has these two properties.

The sequence of discs moved on successive days, which we denote by discn(d), is obtained by taking the first component of each of the pairs in Hn(d) and ignoring the second. Let the sequence that is obtained in this way be denoted by discn(d). Then, from the definition of H we get:

disc0(d) = [] ,

discn+1(d) = discn(¬d) ; [n+1] ; discn(¬d).

Our goal is to prove alt(discn.d). The proof is by induction on n. The base case, n = 0, is clearly true because an empty sequence has no consecutive elements. For the induction step, the property of alternating sequences on which the proof depends is that, for a sequence ks and number k,

alt(ks ; [k] ; ks) ⇐ alt(ks) ∧ ((ks = []) ≡ (k = 1)).

The proof is then:

alt(discn+1(d))

= { definition }

alt(discn(¬d) ; [n+1] ; discn(¬d))

⇐ { above property of alternating sequences }

alt(discn(¬d)) ∧ ((discn(¬d) = []) ≡ (n+1 = 1))

= { induction hypothesis applied to the first conjunct,

straightforward property of discn for the second }

true.

Exercise 8.5 The explorer left the area and did not return until several years later. On his return, he discovered the monks in a state of great despair. It transpired that one of the monks had made a mistake shortly after the explorer’s first visit but it had taken the intervening time before they had discovered the mistake. The state of the discs was still valid but the monks had discovered that they were no longer making progress towards their goal; they had got into a never-ending loop!

Fortunately, the explorer was able to tell the monks how to proceed in order to return all the discs to one and the same pole while still obeying the rules laid down to them on the day of the world’s creation. They would then be able to begin their task afresh.

What was the algorithm the explorer gave to the monks? Say why the algorithm is correct. (Hint: The disc being moved will still alternate between the smallest and some other disc. You only have to decide in which direction the smallest disc should be moved. Because of the monks’ mistake this will not be constant. Make use of the fact that, beginning in a state in which n discs are all on the same pole, maintaining invariant the relationship

even(n) ≡ d ≡ even(k) ≡ d′

for the direction d′ moved by disc k will move n discs in the direction d.)

Exercise 8.6 [Coloured Discs] Suppose each disc is coloured red, white or blue. The colouring of discs is random; different discs may be coloured differently.

Devise an algorithm that will sort the discs so that all the red discs are on one pole, all the white discs are on another pole, and all the blue discs are on the third pole. You may assume that, initially, all discs are on one pole.

8.4 SUMMARY

In this chapter we have seen how to use induction to construct a solution to the Tower of Hanoi problem and then how to transform the inductive solution to an iterative solution that is easy for human beings to execute. An essential component of the inductive solution, which is often overlooked, is the proper formulation of an inductive hypothesis. The transformation to an interative solution involves identifying an invariant of the inductive solution: the odd-numbered disks cycle around the poles in one direction whilst the even-numbered poles cycle around in the opposite direction. The invariant is easy to spot if the poles are arranged at the corners of a triangle rather than in a straight line. This illustrates the importance of recognising and exploiting inherent symmetry in order to avoid unnecessary complexity.

The chapter has also illustrated two important design considerations: the inclusion of the 0-disc problem as the basis for the construction (rather than the 1-disc problem) and the avoidance of unnecessary detail by not naming the poles and referring to the direction of movement of the discs (clockwise or anticlockwise) instead.

8.5 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REMARKS

Information on the history of the Tower of Hanoi problem is taken from [Ste97]. Martin Gardner [Gar08] cites a paper by R.E. Allardice and A.Y. Fraser published in 1884 as describing the iterative solution. Gardner also discusses several related problems. A proof of the correctness of the iterative solution was published in [BL80]. The formulation and proof presented here is based on [BF01].