In this chapter, we present a solution to a more general version of the problem in Section 3.5. The generalisation is to consider an arbitrary number of people; the task is to get all the people across a bridge in the optimal time. Specifically, the problem we discuss is the following:

N people wish to cross a bridge. It is dark, and it is necessary to use a torch when crossing the bridge, but they only have one torch between them. The bridge is narrow and at most 2 people can be on it at any one time. The people are numbered from 1 thru N. Person i takes time t.i to cross the bridge; when two cross together they must proceed at the speed of the slowest.

Construct an algorithm that will get all N people across in the shortest time.

For simplicity, we assume that t.i < t.j whenever i < j. (This means that we assume the people are ordered according to crossing time and that their crossing times are distinct. Assuming that the crossing times are distinct makes the arguments simpler, but is not essential. If the given times are such that t.i = t.j for some i and j, where i < j, we can always consider pairs (t.i, i), where i ranges over people, ordered lexicographically. Renaming the crossing “times” to be such pairs, we obtain a total ordering on times with the desired property.)

10.1 LOWER AND UPPER BOUNDS

The derivation that follows is quite long and surprisingly difficult, particularly in comparison to the final algorithm, which is quite simple. It is important to appreciate where precisely the difficulties lie. This has to do with the difference between establishing an “upper bound” and a “lower bound” on the crossing times.

A lexicograpic ordering on a pair of numbers is defined by

A lexicograpic ordering on a pair of numbers is defined by

[ (m,n) < (p,q) ≡ m < p ∨ (m = p ∧ n < q) ].

See Section 12.7.6 for more on ordering relations.

Because this is a problem about minimising total times, its solution exploits the algebraic properties of minimum and addition. See Section 15.2 for full details of these properties.

In the original problem given in Chapter 1, there are four people with crossing times of 1, 2, 5 and 10 minutes. Crucially, the question asked was to show that all four can cross the bridge within 17 minutes. In other words, the question asks for a so-called upper bound on the time taken. In general, an upper bound is established by exhibiting a sequence of crossings that takes the required time.

A much harder problem is to show that 17 minutes is a lower bound on the time taken. Showing that it is a lower bound means showing that the time can never be bettered.

We can use the same instance of the bridge problem to further illustrate the difference between lower and upper bounds. Most of us, when confronted with the bridge problem, will first explore the solution in which the fastest person accompanies the others across the bridge. Such a solution takes a total time of 2+1+5+1+10 (i.e. 19 minutes). By exhibiting the crossing sequence, we have established that 19 minutes is an upper bound on the crossing time; we have not established that it is a lower bound. (Indeed, it is not.) Similarly, exhibiting the crossing sequence that gets all four people across in 17 minutes does not prove that this time cannot be bettered. Doing so is much harder than just constructing the sequence.

In this chapter, the goal is to construct an algorithm for scheduling N people to cross the bridge. The algorithm we derive is quite simple but, on its own, it only establishes an upper bound on the optimal crossing time. The greatest effort goes into showing that the algorithm simultaneously establishes a lower bound on the crossing time. The combination of equal lower and upper bounds is called an exact bound; this is what is meant by an optimal solution.

In Section 10.6, we present two algorithms for constructing an optimal sequence. The more efficient algorithm assumes a knowledge of algorithm development that goes beyond the material in this book.

10.2 OUTLINE STRATEGY

Once again, the main issue we have to overcome is the avoidance of unnecessary detail. The problem asks for a sequence of crossings, but there is an enormous amount of freedom in the order in which crossings are scheduled. It may be, for example, that the optimal solution is to let one person accompany all the others one by one across the bridge, each time returning with the torch for the next person. If our solution method requires that we detail in what order the people cross, then it is extremely ineffective. The number of different orderings is (N−1)!, which is a very large number even for quite small values of N.

m! is the number of different permutations of m objects. So-called “combinatorics”, introduced in Section 16.8, is the theory of how to count the elements in sets like this.

m! is the number of different permutations of m objects. So-called “combinatorics”, introduced in Section 16.8, is the theory of how to count the elements in sets like this.

The way to avoid unnecessary detail is to focus on what we call the “forward trips”. Recall that, when crossing the bridge, the torch must always be carried. This means that crossings alternate between “forward”and “return” trips, where a forward trip is a crossing in the desired direction, and a return trip is a crossing in the opposite direction. Informally, the forward trips do the work while the return trips service the forward trips. The idea is that, if we can compute the optimal collection of forward trips, the return trips needed to sequence them correctly can be easily deduced.

In order to turn this idea into an effective solution, we need to proceed more formally. First, by the “collection” of forward trips, we mean a “bag” of sets of people. The mathematical notion of a “bag” (or “multiset” as it is sometimes called) is similar to a set but, whereas a set is defined solely by whether or not a value is an element of the set, a bag is defined by the number of times each value occurs in the set. For example, a bag of coloured marbles would be specified by saying how many red marbles are in the bag, how many blue marbles, and so on. We will write, for example, {1*a, 2*b, 0*c} to denote a bag of as, bs and cs in which a occurs once, b occurs twice and c occurs no times. For brevity, we also write {1*a, 2*b} to denote the same bag.

It is important to stress that a bag is different from a sequence. Even though when we write down an expression denoting a bag we are forced to list the elements in a certain order (alphabetical order in {1*a, 2*b, 0*c}, for example), the order has no significance. The expressions {1*a, 2*b, 0*c} and {2*b, 1*a, 0*c} both denote the same bag.

A trip is given by the set of people involved in the trip. So, for example, {1,3} is a trip in which persons 1 and 3 cross. If we are obliged to distinguish between forward and return trips, we prefix the trip with either “+” (for forward) or “−” (for return). So +{1,3} denotes a forward trip made by persons 1 and 3 and −{2} denotes a return trip made by person 2.

As we said above, our focus will be on computing the bag of forward trips in an optimal sequence of trips. We begin by establishing a number of properties of sequences of trips that allow us to do this.

We call a sequence of trips that gets everyone across in accordance with the rules a valid sequence. We will say that one valid sequence subsumes another valid sequence if the time taken by the first is at most the time taken for the second. Note that the subsumes relation is reflexive (every valid sequence subsumes itself) and transitive (if valid sequence a subsumes valid sequence b and valid sequence b subsumes valid sequence c then valid sequence a subsumes valid sequence c). The problem is to find a valid sequence that subsumes all valid sequences.

Reflexivity and transitivity are important properties of a relation discussed in Section 12.7. Note that the subsumes relation is not anti-symmetric and so is not an ordering relation on sequences. (It is what is called a pre-order.) An optimal sequence will typically not be unique: there will typically be many sequences that take the same optimal time.

Reflexivity and transitivity are important properties of a relation discussed in Section 12.7. Note that the subsumes relation is not anti-symmetric and so is not an ordering relation on sequences. (It is what is called a pre-order.) An optimal sequence will typically not be unique: there will typically be many sequences that take the same optimal time.

Formally, a valid sequence is a set of numbered trips with the following two properties:

- The trips are sets; each set has one or two elements, and the number given to a trip is its position in the sequence (where numbering begins from 1).

- Odd-numbered trips in the sequence are called forward trips; even-numbered trips are called return trips. The length of the sequence is odd.

- The trips made by each individual person alternate between forward and return trips, beginning and ending with forward trips. (A trip T is made by person i if i∈T.)

Immediate consequences of this definition which play a crucial role in finding an optimal sequence are as follows:

- The number of forward trips is one more than the number of return trips.

- The number of forward trips made by each individual person is one more than the number of return trips made by that person.

A regular forward trip means a forward trip made by two people, and a regular return trip means a return trip made by exactly one person. A regular sequence is a valid sequence that consists entirely of regular forward and return trips.

The first step (Lemma 10.1) is to show that every valid sequence is subsumed by one in which all trips are regular. The significance of this is threefold.

- In a regular sequence, the number of forward trips is N−1 and the number of return trips is N−2. (Recall that N is the number of people.)

- The time taken by a regular sequence can be evaluated knowing only which forward trips are made; not even the order in which they are made needs to be known. (Knowing the bag of forward trips, it is easy to determine how many times each person makes a return trip. This is because each person makes one fewer return trips than forward trips. In this way, the time taken for the return trips can be calculated.)

- Most importantly, knowing just the bag of forward trips in a regular sequence is sufficient to reconstruct a valid regular sequence. Since all such sequences take the same total time, we can thus replace the problem of finding an optimal sequence of forward and return trips by the problem of finding an optimal bag of forward trips.

Finding an optimal bag of forward trips is then achieved by focusing on which people do not make a return trip. We prove the obvious property that, in an optimal solution, the two slowest people do not return. We can then use induction to determine the complete solution.

10.3 REGULAR SEQUENCES

Recall that a “regular” sequence is a sequence in which each forward trip involves two people and each return trip involves one person. We can always restrict attention to regular sequences because of the following lemma.

Lemma 10.1 Every valid sequence containing irregular trips is subsumed by a strictly faster valid sequence without irregular trips.

Proof Suppose a given valid sequence contains irregular trips. We consider two cases: the first irregular trip is backward and the first irregular trip is forward.

If the first irregular trip is backward, choose an arbitrary person, p say, making the trip. Identify the forward trip made by p prior to the backward trip, and remove p from both trips. More formally, suppose the sequence has the form

u +{p,q} v −{p,r} w

where q and r are people, u, v and w are subsequences and p occurs nowhere in v. (Note that the forward trip made by p involves two people because it is assumed that the first irregular trip is backward.) Replace the sequence by

u +{q} v −{r} w.

This results in a valid sequence, the time for which is no greater than the original sequence. (To check that the sequence remains valid, we have to check that the trips made by each individual continue to alternate between forward and return. This is true for individuals other than p because the points at which they cross remain unchanged, and it is true for p because the trips made by p have changed by the removal of consecutive forward and return trips. The time taken is no greater since, for any x and y, t.p ↑ x + t.p ↑ y ≥ x+y.) The number of irregular crossings is not reduced, since a new irregular forward trip has been introduced, but the total number of person-trips is reduced.

Now suppose the first irregular trip is forward. There are two cases to consider: the irregular trip is the very first in the sequence, and it is not the very first.

If the first trip in the sequence is not regular, it means that one person crosses and then immediately returns. (We assume that N is at least 2.) These two crossings can be removed. Clearly, since times are positive, the total time taken is reduced. Also, the number of person-trips is reduced.

If the first irregular crossing is a forward trip but not the very first, let us suppose it is person p who crosses, and suppose q is the person who returns immediately before this forward trip. (There is only one such person because of the assumption that p’s forward trip is the first irregular trip.) That is, suppose the sequence has the form

u −{q} +{p} v.

Consider the latest crossing that precedes q’s return trip and involves p or q. There are two cases: it is a forward trip or it is a return trip.

If it is a forward trip, it must involve q and not p. Swap p with q in this trip and remove q’s return trip and p’s irregular crossing. That is, transform

u +{q,r} w −{q} +{p} v

(where w does not involve p or q) to

u +{p,r} w v.

The result is a valid sequence. Moreover, the total crossing time is reduced (since, for any x, t.q ↑ x + t.q + t.p > t.p ↑ x), and the number of person-trips is also reduced.

If it is a return trip, it is made by one person only. (This is because we assume that p’s forward trip is the first irregular trip in the sequence.) That person must be p. Swap p with q in this return trip, and remove q’s return trip and p’s irregular crossing. That is, transform

u −{p} w −{q} +{p} v

(where w does not involve p or q) to

u −{q} w v.

The result is a valid sequence. Moreover, the total crossing time is reduced (since t.p+t.q+t.p > t.q), and the number of person-trips is also reduced.

We have now described how to transform a valid sequence that has at least one irregular crossing; the transformation has the effect of strictly decreasing the total time taken. Repeating this process while there are still irregular crossings is therefore guaranteed to terminate with a valid sequence that is regular, subsumes the given valid sequence and has a smaller person-trip count.

10.4 SEQUENCING FORWARD TRIPS

Lemma 10.1 has three significant corollaries. First, it means that the number of forward trips in an optimal sequence is N−1 and the number of return trips is N−2. This is because every subsequence comprising a forward trip followed by a return trip increases the number of people that have crossed by one, and the last trip increases the number by two. Thus, after the first 2×(N−2) trips, N−2 people have crossed and 2 have not, and after 2×(N−2) +1 trips everyone has crossed.

Second, it means that the total time taken to complete any regular sequence can be evaluated if only the bag of forward trips in the sequence is known; not even the order in which the trips are made is needed. This is because the bag of forward trips enables us to determine how many times each individual makes a forward trip. Hence, the number of times each individual returns can be computed, from which the total time for the return trips can be computed.

For example, suppose the forward trips in a regular sequence are as follows:

3*{1,2}, 1*{1,6}, 1*{3,5}, 1*{3,4}, 1*{7,8}.

(The trips are separated by commas; recall that 3*{1,2} means that persons 1 and 2 make 3 forward trips together, 1*{1,6} means that persons 1 and 6 make one forward trip together, etc. Note that no indication is given of the order in which the forward trips occur in the sequence.) Then, counting the number of occurrences of each person in the bag, person 1 makes 4 forward trips, and hence 3 return trips; similarly, person 2 makes 3 forward trips and hence 2 return trips, while person 3 makes 2 forward trips and hence 1 return trip. The remaining people (4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) all make 1 forward trip and, hence, no return trips. The total time taken is thus:

3 × (t.1↑t.2) + 1 × (t.1↑t.6) + 1 × (t.3↑t.5) + 1 × (t.3↑t.4) + 1 × (t.7↑t.8)

+ 3 × t.1 + 2 × t.2 + 1 × t.3.

(The top line gives the time taken by the forward trips, and the bottom line gives the time taken by the return trips.) Note that the total number of forward trips is 7 (one less than the number of people), and the total number of return trips is 6.

The third important corollary of Lemma 10.1 is that, given just the bag of forward trips corresponding to a regular sequence, it is possible to construct a regular sequence to get everyone across with the same collection of forward trips. This is a non-obvious property of the forward trips and to prove that it is indeed the case we need to make some crucial observations.

Suppose F is a bag of forward trips corresponding to some regular sequence. That is, F is a collection of sets, each with exactly two elements and each having a certain multiplicity. The elements of the sets in F are people, which we identify with numbers in the range 1 thru N, and each number in the range must occur at least once. The number of times a person occurs is the number of forward trips made by that person.

We will call a person a settler if they make only one forward trip; we call a person a nomad if they make more than one forward trip. Division of people into these two types causes the trips in F to be divided into three types depending on the number of settlers in the trip. If both people in a trip are settlers we say the trip is hard; if one of the people is a settler and the other a nomad, we say the trip is firm; finally, if both people are nomads we say the trip is soft.

Suppose we use #nomad, #hard, #firm and #soft to denote the number of nomads, the number of hard trips, the number of firm trips and the number of soft trips, respectively, in the collection F. Then, the number of trips in F is

#hard + #firm + #soft.

The number of return trips equals the total number of forward trips made by individual nomads less the number of nomads, since each nomad makes one more forward trip than return trip. Since each soft trip contributes 2 to the number of forward trips made by nomads, and each firm trip contributes 1, the number of return trips is thus

2 × #soft + #firm − #nomad.

But the number of forward trips is one more than the number of return trips. That is,

#hard + #firm + #soft = 2 × #soft + #firm − #nomad + 1.

Equivalently,

#hard + #nomad = #soft + 1.

We summarise these properties in the following definition.

Definition 10.2 (Regular Bag) Suppose N is at least 2. A bag of subsets of {i | 1≤i ≤N} is called a regular N-bag if it has the following properties:

- Each element of F has size 2. (Informally, each trip in F involves two people.)

∀i : 1≤ i ≤N :

∀i : 1≤ i ≤N :  ∃T : T∈F : i∈T

∃T : T∈F : i∈T

. (Informally, every person is an element of at least one trip in F.)

. (Informally, every person is an element of at least one trip in F.)- If #hard.F, #soft.F and #nomad.F denote, respectively, the number of trips in F that involve two settlers, the number of trips in F that involve no settlers, and the number of nomads in F, then

Formally, what we have proved is the following.

“∀” and “∃” denote the so-called universal and existential quantifiers. Later we use “Σ” for summation. We use a uniform notation for all quantifiers which is explained in Chapter 14.

“∀” and “∃” denote the so-called universal and existential quantifiers. Later we use “Σ” for summation. We use a uniform notation for all quantifiers which is explained in Chapter 14.

Lemma 10.4 Given a valid regular sequence of trips to get N people across, where N is at least 2, the bag of forward trips F that is obtained from the sequence by forgetting the numbering of the trips is a regular N-bag. Moreover, the time taken by the sequence of trips can be evaluated from F. Let #FT denote the multiplicity of T in F. Then, the time taken is

where

(rFi is the number of times that person i returns.)

Combining the definitions of the trip types with (10.3), we make a number of deductions. If #nomad.F is zero, there are no nomads and hence, by definition, no soft or firm trips. So, by (10.3), #hard.F is 1. That is,

If there is only one nomad, there are no trips involving two nomads. That is #soft.F is zero. It follows from (10.3) that #hard.F also equals zero. The converse is immediate from (10.3). That is,

If N (the number of people) is greater than 2, not all can cross at once, and so #nomad.F is at least 1. It follows from (10.3) that #soft.F is at least 1:

Now we can show how to construct a regular sequence from F.

Lemma 10.10 Given N (at least 2) and a regular N-bag, a valid regular sequence of trips can be constructed from F to get N people across. The time taken by the sequence is given by (10.5).

Proof The proof is by induction on the size of the bag F. We need to consider three cases.

The easiest case is when F consists of exactly one trip (with multiplicity one). The sequence is then just this one trip.

The second case is also easy. It is the case where #nomad.F = 1. In this case, every trip in F is firm. That is, each trip has the form {n,s} where n is the nomad and s is a settler. The sequence is simply obtained by listing all the elements of F in an arbitrary order and inserting a return trip by the nomad n in between each pair of forward trips of which the first is the trip {n,s} for some s.

The third case is that #hard.F is non-zero and F has more than one trip. In this case, by (10.9), #soft.F is at least 1. It follows, by definition of soft, that #nomad.F is at least 2. Choose any soft trip in F. Suppose it is {n,m}, where n and m are both nomads. Construct the sequence which begins with the trip {n,m} and is followed by the return of n, then an arbitrary hard trip and then the return of m. Reduce the multiplicity of the chosen hard trip and the chosen soft trip in F by 1. (That is, remove one occurrence of each from F.) We get a new bag F′ in which the number of trips made by each of n and m has been reduced by 1 and the number of people has been reduced by 2. By induction, there is a regular sequence corresponding to F′ which gets the remaining people across.

Optimisation Problem Lemmas 10.4 and 10.10 have a significant impact on how to solve the general case of the bridge problem. Instead of seeking a sequence of crossings of optimal duration, we seek a regular bag as defined in Definition 10.2 that optimises the time given by (10.5). It is this problem that we now solve.

In solving this problem, it is useful to introduce some terminology when discussing the time taken as given by (10.5). There are two summands in this formula: the value of the first summand we call F’s total forward time, and the value of the second summand F’s total return time. Given a bag F and a trip T in F, we call  ⇑i : i∈T : t.i

⇑i : i∈T : t.i ×#FT the forward time of T in F. (Sometimes “in F” is omitted if this is clear from the context.) For each person i, we call the value of t.i × rFi the return time of person i.

×#FT the forward time of T in F. (Sometimes “in F” is omitted if this is clear from the context.) For each person i, we call the value of t.i × rFi the return time of person i.

10.5 CHOOSING SETTLERS AND NOMADS

This section is about how to choose settlers and nomads. We establish that the settlers are the slowest people and the nomads are the fastest. More specifically, we establish that in an optimal solution there are at most 2 nomads. Person 1 is always a nomad if N is greater than 2; additionally, person 2 may also be a nomad.

Lemma 10.11 Every regular bag is subsumed by a regular bag for which all settlers are slower than all nomads.

Proof Suppose the regular N-bag F is given. Call a pair of people (p, q) an inversion if, within F, p is a settler, q is a nomad and p is faster than q.

Choose any inversion (p, q). Suppose q and p are interchanged everywhere in F. We get a regular N-bag. Moreover, the return time is clearly reduced by at least t.q − t.p.

The forward times for the trips not involving p or q are, of course, unchanged. The forward time for the trips originally involving q are not increased (because t.p < t.q). The forward time for the one trip originally involving p is increased by an amount that is at most t.q−t.p. This is verified by considering two cases. The first case is when the trip involving p is {p,q}. In this case, swapping p and q has no effect on the trip, and the increase in time taken is 0. In the second case, the trip involving p is {p,r} where r ≠ q. In this case, it suffices to observe that

t.p ↑ t.r + (t.q − t.p)

= { distributivity of addition over max, arithmetic }

t.q ↑ (t.r + (t.q − t.p))

≥ { t.p ≤ t.q, monotonicity of max }

t.q ↑ t.r.

Finally, the times for all other forward trips are unchanged.

The net effect is that the total time taken does not increase. That is, the transformed bag subsumes the original bag. Also, the number of inversions is decreased by at least one. Thus, by repeating the process of identifying and eliminating inversions, a bag F is obtained that subsumes the given bag.

Corollary 10.12 Every regular N-bag is subsumed by a regular N-bag F with the following properties:

- In any firm trip in F, the nomad is person 1.

- Every soft trip in F is {1,2}. (Note that the multiplicity of this trip in the bag can be an arbitrary number, including 0.)

- The multiplicity of {1,2} in F is j, for some j where 1≤j ≤N÷2, and the hard trips are {k: 0≤ k< j−1: {N− 2×k, N− 2×k− 1}}. (Note that this is the empty set when j equals 1.)

The set of hard trips is a set of sets. Standard mathematical notation for the set

The set of hard trips is a set of sets. Standard mathematical notation for the set

{{N− 2×k, N− 2×k−1} | 0≤ k<j−1}

does not make clear that the variable k is bound and variables j and N are free. See Section 14.2.2 for further discussion.

Proof Suppose F is a regular N-bag that optimises the total travel time. From Lemma 10.11, we may assume that the settlers are slower than the nomads.

Suppose there is a firm trip in F in which the nomad is person i where i is not 1. Replace i in one occurrence of the trip by person 1. This has no effect on the forward time, since i is slower than the other person in the trip. However, the total return time is reduced (by t.i−t.1). We claim that this results in a regular N-bag, which contradicts F being optimal. (See Lemma 10.4 for the properties required of a regular bag.)

Of course, the size of each set in F is unchanged. The number of trips made by i decreases by one, but remains positive because i is a nomad in F. The number of trips made by all other persons either remains unchanged or, in the case of person 1, increases. So it remains to check property (10.3). If person i is still a nomad after the replacement, property (10.3) is maintained because the type (hard, firm or soft) of each trip remains unchanged. However, person i may become a settler. That is, the number of nomads may be decreased by the replacement. If so, person i is an element of two trips in F. The second trip is either a firm trip in F and becomes a hard trip, or it is a soft trip in F and becomes firm. In both cases, it is easy to check that (10.3) is maintained.

Now suppose there is a soft trip in F different from {1,2}. A similar argument to the one above shows that replacing the trip by {1,2} results in a regular bag with a strictlysmaller total travel time, contradicting F being optimal.

We may now conclude from (10.3) that either there are no soft trips or the multiplicity of {1,2} in F is j, for some j which is at least 2, and there are j−1 hard trips. When there are no soft trips, all the trips are firm or hard. But, as we have shown, person 1 is the only nomad in firm trips and there are no nomads in hard trips; it follows that person 1 is the only nomad in F and, from (10.3), that there are no hard trips. Thus persons 1 and 2 are the elements of one (firm) trip in F.

It remains to show that, when j is at least 2, the hard trips form the set

{k: 0≤ k< j−1: {N− 2×k, N− 2×k− 1}}.

(The multiplicity of each hard trip is 1, so we can ignore the distinction between bags and sets.)

Assume that the number of soft trips is j, where j is at least two. Then the settlers are persons 3 thru N, and 2×(j−1) of them are elements of hard trips, the remaining N−2×(j−2) being elements of firm trips. Any regular bag clearly remains regular under any permutation of the settlers. So we have to show that choosing the settlers so that the hard trips are filled in order of slowness gives the optimal arrangement. This is done by induction on the number of settlers in the hard trips.

Corollary 10.13 Suppose F is an optimal solution satisfying the properties listed in Corollary 10.12. Then, if j is the multiplicity of {1,2} in F, the total time taken by F is

where

HF.j =  Σi : 0≤i<j−1 : t.(N−2i)

Σi : 0≤i<j−1 : t.(N−2i)

and

FF.j =  Σi : 3 ≤ i ≤ N − 2×(j−1) : t.i

Σi : 3 ≤ i ≤ N − 2×(j−1) : t.i .

.

(The first three terms give the forward times, and the last two terms give the return times.)

Proof There are two cases to consider. If there are no soft trips, the value of j is 1. In this case, the total time taken is

Σi :2≤i ≤N: t.i

Σi :2≤i ≤N: t.i + (N−2) × t.1.

+ (N−2) × t.1.

HF.1 + FF.1 + 1 × t.2 + (N−1−1) × t.1 + (1−1) × t.2

= { definition of HF and FF, arithmetic }

0 +  Σi : 3 ≤ i ≤ N : t.i

Σi : 3 ≤ i ≤ N : t.i + t.2 + (N−2) × t.1

+ t.2 + (N−2) × t.1

= { arithmetic }

Σ i : 2 ≤ i ≤ N : t.i

Σ i : 2 ≤ i ≤ N : t.i + (N−2) × t.1.

+ (N−2) × t.1.

If there are soft trips, the value of j is equal to the number of soft trips and is at least 2. In this case, HF.j is the forward time for the hard trips in F and FF.j is the forward time for the firm trips in F. Also, j × t.2 is the forward time for the j soft trips. Finally, person 1’s return time is (N−j−1) × t.1 and person 2’s return time is (j−1) × t.2. (Person 2 is an element of j forward trips, and person 1 is an element of j +(N− 2×(j−1) −3+ 1) forward trips. Note that the sum of j−1 and N−j−1 is N−2, which is what we expect the number of return trips to be.)

10.6 THE ALGORITHM

For all j, where j is at least 2, define OT.j to be the optimal time taken by a regular N-bag where the multiplicity of {1,2} in the bag is j. That is, OT.j is given by (10.14). Now, we observe that

HF.(j+1) – HF.j = t.(N–2j+2)

and

FF.(j+1) – FF.j = –(t.(N–2j+2) + t.(N–2j+1)).

As a consequence,

OT.(j+1) – OT.j = –t.(N–2j+1) + 2 × t.2 – t.1.

Note that

OT.(j+1) – OT.j ≤ OT.(k+1) – OT.k

= { above }

–t.(N–2j+1) + 2 × t.2 – t.1 ≤ –t.(N–2k+1) + 2 × t.2 – t.1

= { arithmetic }

t.(N–2k+1) ≤ t.(N–2j+1)

= { t increases monotonically }

j ≤ k.

That is, OT.(j+1) − OT.j increases as j increases. A consequence is that the minimum value of OT.j can be determined by a search for the point at which the difference function changes from being negative to being positive.

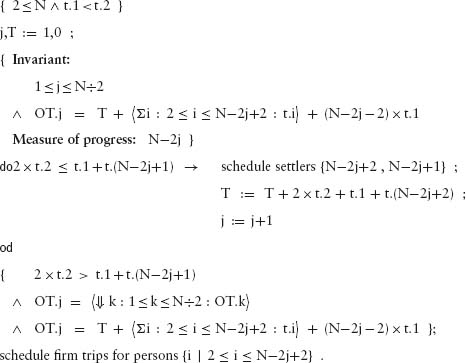

The simplest way to do this and simultaneously construct a regular sequence to get all N people across is to use a linear search, beginning with j assigned to 1. At each iteration the test 2 × t.2 ≤ t.1+t.(N−2j+1) is performed. If it evaluates to true, the soft trip {1,2} is scheduled; this is followed by the return of person 1, then the hard trip {N−2j+2, N−2j+1} and then the return of person 2. If the test evaluates to false, the remaining N−2j+2 people are scheduled to cross in N−2j+1 firm trips. In each trip one person crosses accompanied by person 1; in between two such trips person 1 returns. This algorithm is documented below. For brevity, the details of the trip schedules have been omitted. Note that the loop is guaranteed to terminate because j is increased by 1 at each iteration so that eventually N−2j+1 equals 1 or 2. In either case, the test for termination will succeed (because t.1 < t.2). The invariant documents the optimal time needed to get all N people across when the multiplicity of {1,2} in the bag of forward trips is j.

Linear search is a very elementary algorithmic technique. Those familiar with a programming language will recognise a linear search as a so-called for loop. Binary search is typically more efficient than linear search, but is not always applicable. Binary search is used as an example of algorithm design in Section 9.3. The algorithm presented there can be adapted to solve Exercise 10.15.

Linear search is a very elementary algorithmic technique. Those familiar with a programming language will recognise a linear search as a so-called for loop. Binary search is typically more efficient than linear search, but is not always applicable. Binary search is used as an example of algorithm design in Section 9.3. The algorithm presented there can be adapted to solve Exercise 10.15.

Exercise 10.15 When the number N is large, the number of tests can be reduced by using binary search to determine the optimal value of j. Show how this is done.

In Chapter 3, we argued that brute-force search should be avoided whenever possible. Brute-force search is applicable to river-crossing problems where the issue is whether there is a way of crossing according to the given constraints. In the bridge problem, finding at least one way of getting the people across the bridge is clearly not an issue; the problem is getting the people across in the fastest time.

In Chapter 3, we argued that brute-force search should be avoided whenever possible. Brute-force search is applicable to river-crossing problems where the issue is whether there is a way of crossing according to the given constraints. In the bridge problem, finding at least one way of getting the people across the bridge is clearly not an issue; the problem is getting the people across in the fastest time.

The state-transition graph for the bridge problem is acyclic. A method akin to brute-force search for solving optimisation problems on an acyclic graph is so-called “dynamic programming”. Like brute-force search, it involves constructing a state-transition diagram and then using topological search to explore the different paths through the diagram to determine the best path. See Section 16.7 for more information on acylic graphs and topological search.

Dynamic programming is useful for some problems where the state-transition diagram has little or no structural properties but, just as for brute-force search, it should not be used blindly. The execution time of dynamic programming depends on the number of states in the state-transition diagram. This is typically substantially smaller than the total number of different paths – making dynamic programming substantially more efficient than a brute-force search of all paths – but, even so, the number of states can grow exponentially, making dynamic programming impractical except for small instances.

Exercise 10.16 is about quantifying the number of states and the number of different ways (including suboptimal ways) of solving the bridge problem. The conclusion is that dynamic programming is unacceptably inefficient except for relatively small numbers of people.

Exercise 10.16 In this exercise, consider only solutions to the problem in which, repeatedly, two people cross and one returns. Thus, every solution has N−1 forward trips and N−2 return trips.

(a) Calculate the number of states in the state-transition diagram for the bridge problem.

(b) Calculate the number of different ways of getting everyone across the bridge.

Tabulate your answers for N equal to 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

10.7 SUMMARY

In this chapter, we have presented an algorithm to solve the bridge problem for an arbitrary number of people and arbitrary individual crossing times. The greatest challenge in an optimisation problem of this nature is to establish without doubt that the algorithm constructs a solution that cannot be improved. A major step in solving the problem was to eliminate the need to consider sequences of crossings and to focus on the bag of forward trips. Via a number of lemmas, we established a number of properties of an optimum bag of forward trips that enabled us to construct the required algorithm.

Many of the properties we proved are not surprising. An optimal sequence is “regular” – that is, each forward trip is made by two people and each return trip is made by one; the “settlers” (the people who never make a return trip) are the slowest, and the “nomads” (the people who do make return trips) are the fastest. Less obvious is that there are at most two nomads and the number of “hard” trips (trips made by two settlers) is one less than the number of trips that the two fastest people make together. The proof of the fact that there are at most two nomads is made particularly easy by the focus on the bag of forward trips; if we had to reason about the sequence of trips, this property could have been very difficult to establish.

Even though these properties may seem unsurprising and the final algorithm (in retrospect) perhaps even “obvious”, it is important to appreciate that proof is required: the interest in the bridge problem is that the most “obvious” solution (letting the fastest person accompany everyone else across the bridge) is not always the best solution. Always beware of claims that something is “obvious”.

10.8 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REMARKS

In American English, the bridge problem is called the “flashlight problem”; it is also sometimes called the “torch problem”. The solution presented here is based on a solution to the yet more general problem in which the capacity of the bridge is a parameter [Bac08]. In terms of this more general problem, this chapter is about the capacity-2 problem; the solution is essentially the same as a solution given by Rote [Rot02]. Rote gives a comprehensive bibliography, including pointing out one publication where the algorithm is incorrect.

When the capacity of the bridge is also a parameter, the problem is much harder to solve. Many “obvious” properties of an optimal solution turn out to be false. For example, it is no longer the case that an optimal solution uses a minimum number of crossings. (If N = 5, the capacity of the bridge is 3 and the travel times are 1, 1, 4, 4 and 4, the shortest time is 8, which is achieved using 5 crossings. The shortest time using 3 crossings is 9.)