The island of knights and knaves is a fictional island that is often used to test students’ ability to reason logically. The island has two types of natives, “knights” who always tell the truth, and “knaves” who always lie. Logic puzzles involve deducing facts about the island from statements made by its natives without knowing whether or not the statements are made by a knight or a knave.

The temptation is to solve such problems by case analysis – in a problem involving n natives, consider the 2n different cases obtained by assuming that the individual natives are knights or knaves. Case analysis is a clumsy way of tackling the problems. In contrast, these and similar logic puzzles are easy exercises in the use of calculational logic, which we introduce in this chapter.

The form of this chapter diverges from our usual practice of referring the reader to Part II of the book. This is because the techniques needed are unfamiliar but very necessary. The chapter gives a first introduction to calculational logic – enough to solve the knights-and-knaves puzzles – while Chapter 13 takes the subject further for more general use.

5.1 LOGIC PUZZLES

Here is a typical collection of knights-and-knaves puzzles.

1. It is rumoured that there is gold buried on the island. You ask one of the natives whether there is gold on the island. The native replies: “There is gold on this island is the same as I am a knight.”

The problem is

(a) Can it be determined whether the native is a knight or a knave?

(b) Can it be determined whether there is gold on the island?

2. Suppose you come across two of the natives. You ask both of them whether the other one is a knight.

Will you get the same answer in each case?

3. There are three natives A, B and C. Suppose A says “B and C are the same type”.

What can be inferred about the number of knights?

4. Suppose C says “A and B are as like as two peas in a pod”.

What question should you pose to A to determine whether or not C is telling the truth?

5. Devise a question that allows you to determine whether a native is a knight.

6. What question should you ask A to determine whether B is a knight?

7. What question should you ask A to determine whether A and B are the same type (i.e. both knights or both knaves)?

8. You would like to determine whether an odd number of A, B and C is a knight. You may ask one yes/no question to any one of them.

What is the question you should ask?

9. A tourist comes to a fork in the road, where one branch leads to a restaurant and one does not. A native of the island is standing at the fork.

Formulate a single yes/no question that the tourist can ask such that the answer will be yes if the left fork leads to the restaurant, and otherwise the answer will be no.

5.2 CALCULATIONAL LOGIC

5.2.1 Propositions

The algebra we learn at school is about calculating with expressions whose values are numbers. We learn, for example, how to manipulate an expression like m2−n2 in order to show that its value is the same as the value of (m+n)×(m−n), independently of the values of m and n. We say that m2−n2 and (m+n)×(m−n) are equal, and write

m2−n2 = (m+n)×(m−n).

The basis for these calculations is a set of laws. Laws are typically primitive, but general, equalities between expressions. They are “primitive” in the sense that they cannot be broken down into simpler laws, and they are “general” in the sense that they hold independently of the values of any variables in the constituent expressions. We call them axioms. Two examples of axioms, both involving zero, are

n+0 = n,

and

n−n = 0,

both of which are true whatever the value of the variable n. We say they are true “for all n”. The laws are often given names so that we can remember them more easily. For example, “associativity of addition” is the name given to the equality

(m+n)+p = m+(n+p),

which is true for all m, n and p.

(Calculational) logic is about calculating with expressions whose values are so-called “booleans” – that is, either true or false. Examples of such expressions are “it is sunny” (which is either true or false depending on to when and where “it” refers), n = 0 (which is either true or false depending on the value of n), and n < n+1 (which is true for all numbers n). Boolean-valued expressions are called propositions. Atomic propositions are propositions that cannot be broken down into simpler propositions. The three examples above are all atomic. A non-atomic proposition would be, for example, m < n < p, which can be broken down into the so-called conjunction of m < n and n < p.

Logic is not concerned with the truth or otherwise of atomic propositions; that is the concern of the problem domain being discussed. Logic is about rules for manipulating the logical connectives – the operators like “and”, “or” and “if” that are used to combine atomic propositions.

Calculational logic places emphasis on equality of propositions, in contrast to other axiomatisations of logic, which emphasise logical implication (if . . . then . . .). Equality is the most basic concept of logic – a fact first recognised by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,1 who was the first to try to formulate logical reasoning – and equality of propositions is no exception. We see shortly that equality of propositions is particularly special, recognition of which considerably enhances the beauty and power of reasoning with propositions.

5.2.2 Knights and Knaves

Equality of propositions is central to solving puzzles about knights and knaves. Recall that a knight always tells the truth, and a knave always lies. If A is a native of the island, the statement “A is a knight” is either true or false, and so is a proposition. Also, the statements made by the natives are propositions. A statement like “the restaurant is to the left” is either true or false. Suppose A denotes the proposition “A is a knight”, and suppose native A makes a statement S. Then, the crucial observation is that the values of these two propositions are the same. That is,

For example, if A says “the restaurant is to the left”, then

A = L,

where L denotes the truth value of the statement “the restaurant is to the left”. In words, A is a knight and the restaurant is to the left, or A is not a knight and the restaurant is not to the left.

Using this rule, if A says “I am a knight”, we deduce

A = A.

This does not tell us anything! A moment’s thought confirms that this is what one would expect. Both knights and knaves would claim that they are knights.

If native A is asked a yes/no question Q, the response to the question is the truth value of A = Q. That is, the response will be “yes” if A is a knight and the answer is really yes, or A is a knave and the answer is really no. Otherwise the response will be “no”. For example, asked the question “are you a knight” all natives will answer “yes”, as A = A. Asked the question “is B a knight?” A will respond “yes” if they are both the same type (i.e. A = B), otherwise “no”. That is, A’s response is “yes” or “no” depending on the truth or falsity of A = B.

Because these rules are equalities, the algebraic properties of equality play a central role in the solution of logic puzzles formulated about the island. A simple first example is if A is asked whether B is a knight, and B is asked whether A is a knight. As discussed above, A’s response is A = B. Reversing the roles of A and B, B’s response is B = A. But, equality is symmetric; therefore, the two responses will always be the same. Note that this argument does not involve any case analysis on the four different values of A and B.

The calculational properties of equality of booleans are discussed in the next section before we return again to the knights and knaves.

5.2.3 Boolean Equality

Equality – on any domain of values – has a number of characteristic properties. First, it is reflexive. That is, x = x whatever the value (or type) of x. Second, it is symmetric.

That is, x = y is the same as y = x. Third, it is transitive. That is, if x = y and y = z then x = z. Finally, if x = y and f is any function then f(x) = f(y) (where the parentheses denote function application). This last rule is called substitution of equals for equals or Leibniz’s rule.

Equality is a binary relation. When studying relations, reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity are properties that we look out for. Equality is also a function. It is a function with range the boolean values true and false. When we study functions, the sort of properties we look out for are associativity and symmetry. For example, addition and multiplication are both associative: for all x, y and z,

x + (y + z) = (x + y) + z

and

x × (y × z) = (x × y) × z.

They are also both symmetric: for all x and y,

x + y = y + x

and

x × y = y × x.

Symmetry of equality, viewed as a function, is just the same as symmetry of equality, viewed as a relation. But, what about associativity of equality? Is equality an associative operator?

The answer is that, in all but one case, the question does not make sense. Associativity of a binary function only makes sense if the domains of its two arguments and the range of its result are all the same. The expression (p = q) = r just does not make sense when p, q and r are numbers, or characters, or sequences, etc. The one exception is equality of boolean values. When p, q and r are all booleans it makes sense to compare the boolean p = q with r for equality. That is, (p = q) = r is a meaningful boolean value. Similarly, so too is p = (q = r). It also makes sense to compare these two values for equality. In other words, it makes sense to ask whether equality of boolean values is associative – and, perhaps surprisingly, it is. That is, for all booleans p, q and r,

The associativity of equality is a very powerful property, for one because it enhances economy of expression. We will see several examples; an elementary example is the following.

The reflexivity of equality is expressed by the rule

[ (p = p) = true ].

The square “everywhere” brackets emphasise that this holds for all p, whatever its type (number, boolean, string, etc.). But, for boolean p, we can apply the associativity of equality to get

[ p = (p = true) ].

This rule is most commonly used to simplify expressions by eliminating “true” from an expression of the form p = true. We use it several times below.

5.2.4 Hidden Treasures

We can now return to the island of knights and knaves, and discover the hidden treasures. Let us consider the first problem posed in Section 5.1. What can we deduce if a native says “I am a knight equals there is gold on the island”? Let A stand for “the native is a knight” and G stand for “there is gold on the island”. Then the native’s statement is A = G, and we deduce that

A = (A = G)

is true. So,

true

= { A’s statement }

A = (A = G)

= { equality of booleans is associative }

(A = A) = G

= { [ (A = A) = true ],

substitution of equals for equals }

true = G

= { equality is symmetric }

G = true

= { [ G = (G = true) ] }

G.

We conclude that there is gold on the island, but it is not possible to determine whether the native is a knight or a knave.

Suppose, now, that the native is at a fork in the road, and you want to determine whether the gold can be found by following the left or right fork. You want to formulate a question such that the reply will be “yes” if the left fork should be followed, and “no” if the right fork should be followed.

As usual, we give the unknown a name. Let Q be the question to be posed. Then, as we saw earlier, the response to the question will be A = Q. Let L denote “the gold can be found by following the left fork”. The requirement is that L is the same as the response to the question. That is, we require that L = (A = Q). But,

L = (A = Q)

= { equality is associative }

(L = A) = Q.

So, the question Q to be posed is L = A. That is, ask the question “Is the truth value of ‘the gold can be found by following the left fork’ equal to the truth value of ‘you are a knight’?”.

Some readers might object that the question is too “mathematical”; a question that cannot be expressed in everyday language is not a valid solution to the problem. An alternative way of phrasing Q in “natural” language is presented in Section 5.4.3.

Some readers might object that the question is too “mathematical”; a question that cannot be expressed in everyday language is not a valid solution to the problem. An alternative way of phrasing Q in “natural” language is presented in Section 5.4.3.

Note that this analysis is valid independently of what L denotes. It might be that you want to determine whether there is a restaurant on the island, or whether there are any knaves on the island, or whatever. In general, if it is required to determine whether some proposition P is true or false, the question to be posed is P = A. In the case of more complex propositions P, the question may be simplified.

5.2.5 Equals for Equals

Equality is distinguished from other logical connectives by Leibniz’s rule: if two expressions are equal, one expression can be substituted for the other. Here, we consider one simple example of the use of Leibniz’s rule:

Suppose there are three natives of the island, A, B and C, and C says “A and B are both the same type”. Formulate a question that, when posed to A, determines whether C is telling the truth.

To solve this problem, we let A, B and C denote the propositions A, B and C is a knight, respectively. We also let Q be the unknown question.

The response we want is C. So, by the analysis in Section 5.2.4, Q = (A = C). But C’s statement is A = B. So we know that C = (A = B). Substituting equals for equals, Q = (A = (A = B)). But A = (A = B) simplifies to B. So the question to be posed is “Is B a knight?”. Here is this argument again, but set out as a calculation of Q, with hints showing the steps taken at each stage.

Q

= { rule for formulating questions }

A = C

= { from C’s statement, C = (A = B),

substitution of equals for equals }

A = (A = B)

= { associativity of equality }

(A = A) = B

= { (A = A) = true }

true = B

= { (true = B) = B }

B.

5.3 EQUIVALENCE AND CONTINUED EQUALITIES

Associative functions are usually denoted by infix operators.2 The benefit in calculations is immense. If a binary operator ⊕ is associative (that is, (x⊕y)⊕z = x⊕(y⊕z) for all x, y and z), we can write x⊕y⊕z without fear of ambiguity. The expression becomes more compact because of the omission of parentheses. More importantly, the expression is unbiased; we may choose to simplify x⊕y or y⊕z depending on which is the most convenient. If the operator is also symmetric (that is, x⊕y = y⊕x for all x and y) the gain is even bigger, because then, if the operator is used to combine several subexpressions, we can choose to simplify u⊕w for any pair of subexpressions u and w.

Infix notation is also often used for binary relations. We write, for example, 0 ≤ m ≤ n. Here, the operators are being used conjunctionally: the meaning is 0 ≤ m and m ≤ n. In this way, the formula is more compact (since m is not written twice). More importantly, we are guided to the inference that 0 ≤ n. The algebraic property that is being hidden here is the transitivity of the at-most relation. If the relation between m and n is m < n rather than m ≤ n and we write 0 ≤ m < n, we may infer that 0 < n. Here, the inference is more complex since there are two relations involved. But, it is an inference that is so fundamental that the notation is designed to facilitate its recognition.

Refer to Section 12.3.2 for a detailed discussion of infix (and other) notation for binary operators like addition and multiplication. Section 12.5 discusses important algebraic properties like associativity and symmetry. Section 12.7 extends the discussion to binary relations.

Refer to Section 12.3.2 for a detailed discussion of infix (and other) notation for binary operators like addition and multiplication. Section 12.5 discusses important algebraic properties like associativity and symmetry. Section 12.7 extends the discussion to binary relations.

In the case of equality of boolean values, we have a dilemma. Do we understand equality as a relation and read a continued expression of the form

x = y = z

as asserting the equality of all of x, y and z? Or do we read it “associatively” as

(x = y) = z,

or, equally, as

x = (y = z),

in just the same way as we would read x+y+z? The two readings are, unfortunately, not the same (for example true = false = false is false according to the first reading but true according to the second and third readings). There are advantages in both readings, and it is a major drawback to have to choose one in favour of the other.

It would be very confusing and, indeed, dangerous to read x = y = z in any other way than x = y and y = z; otherwise, the meaning of a sequence of expressions separated by equality symbols would depend on the type of the expressions. Also, the conjunctional reading (for other types) is so universally accepted – for good reasons – that it would be quite unacceptable to try to impose a different convention.

The solution to this dilemma is to use two different symbols to denote equality of boolean values – the symbol “=” when the transitivity of the equality relation is to be emphasised and the symbol “≡” when its associativity is to be exploited. Accordingly, we write both p = q and p ≡ q. When p and q are expressions denoting boolean values, these both mean the same. But a continued expression

p ≡ q ≡ r,

comprising more than two boolean expressions connected by the “≡” symbol, is to be evaluated associatively – i.e. as (p ≡ q) ≡ r or p ≡ (q ≡ r), whichever is the most convenient – whereas a continued expression

p = q = r

is to be evaluated conjunctionally – that is, as p = q and q = r. More generally, a continued equality of the form

p1 = p2 = . . . = pn

means that all of p1, p2, . . ., pn are equal, while a continued equivalence of the form

p1 ≡ p2 ≡ . . . ≡ pn

has the meaning given by fully parenthesising the expression (in any way whatsoever, since the outcome is not affected) and then evaluating the expression as indicated by the chosen parenthesisation.

Moreover, we recommend that the “≡” symbol is pronounced as “equivales”; being an unfamiliar word, its use will help to avoid misunderstanding.

Shortly, we introduce a number of laws governing boolean equality. They invariably involve a continued equivalence. A first example is its reflexivity.

5.3.1 Examples of the Associativity of Equivalence

This section contains a couple of beautiful examples illustrating the effectiveness of the associativity of equivalence.

Even and Odd Numbers The first example is the following property of the predicate even on numbers. (A number is even exactly when it is a multiple of 2.)

[ m+n is even ≡ m is even ≡ n is even ].

It will help if we refer to whether or not a number is even or odd as the parity of the number. Then, if we parenthesise the statement as

[ m+n is even ≡ (m is even ≡ n is even) ],

it states that the number m+n is even exactly when the parities of m and n are the same. Parenthesising it as

[ (m+n is even ≡ m is even) ≡ n is even ],

it states that the operation of adding a number n to a number m does not change the parity of m exactly when n is even.

Another way of reading the statement is to use the fact that, in general, the equivalence p ≡ q ≡ r is true exactly when an odd number of p, q and r is true. So the property captures four different cases:

((m+n is even) and (m is even) and (n is even))

or ((m+n is odd) and (m is odd) and (n is even))

or ((m+n is odd) and (m is even) and (n is odd))

or ((m+n is even) and (m is odd) and (n is odd)).

The beauty of this example lies in the avoidance of case analysis. There are four distinct combinations of the two booleans “m is even” and “n is even”. Using the associativity of equivalence, the value of “m+n is even” is expressed in one simple formula, without any repetition of the component expressions, rather than as a list of different cases. Avoidance of case analysis is vital to effective reasoning.

Sign of Non-Zero Numbers The sign of a number says whether or not the number is positive. For non-zero numbers x and y, the product x×y is positive if the signs of x and y are equal. If the signs of x and y are different, the product x×y is negative.

Assuming that x and y are non-zero, this rule is expressed as

[ x×y is positive ≡ x is positive ≡ y is positive ].

Just as for the predicate even, this one statement neatly captures a number of different cases, even though no case analysis is involved. Indeed, our justification of the rule is the statement

[ x×y is positive ≡ (x is positive ≡ y is positive) ].

The other parenthesisation – which states that the sign of x is unchanged when it is multiplied by y exactly when y is positive – is obtained “for free” from the associativity of boolean equality.

5.3.2 On Natural Language

Many mathematicians and logicians appear not to be aware that equality of booleans is associative. Most courses on logic first introduce implication (“only if”) and then briefly mention “follows from” (“if”) before introducing boolean equality as “if and only if”. This is akin to introducing equality of numbers by first introducing the at-most (≤) and at-least (≥) relations, and then defining an “at most and at least” operator.

The most probable explanation lies in the fact that many logicians view the purpose of logic as formalising “natural” or “intuitive” reasoning, and our “natural” tendency is not to reason in terms of equalities, but in causal terms. (“If it is raining, I will take my umbrella.”) The equality symbol was first introduced into mathematics by Robert Recorde in 1557, which, in the history of mathematics, is quite recent; were equality “natural” it would have been introduced much earlier. Natural language has no counterpart to a continued equivalence.

This fact should not be a deterrent to the use of continued equivalence. At one time (admittedly, a very long time ago) there was probably similar resistance to the introduction of continued additions and multiplications. The evidence is still present in the language we use today. For example, the most common way to express time is in words – “quarter to ten” or “ten past eleven”. Calculational requirements (e.g. wanting to determine how long is it before the train is due to arrive) have influenced natural language so that, nowadays, people sometimes say, for example, “nine forty-five” or “eleven ten” in everyday speech. But we still do not find it acceptable to say “ten seventy”! Yet this is what we actually use when we want to calculate the time difference between 9.45 and 11.10. In fact, several laws of arithmetic, including associativity of addition, are fundamental to the calculation. Changes in natural language have occurred, and will continue to occur, as a result of progress in mathematics, but will always lag a long way behind. The language of mathematics has developed in order to overcome the limitations of natural language. The goal is not to mimic “natural” reasoning, but to provide a more effective alternative.

5.4 NEGATION

Consider the following knights-and-knaves problem. There are two natives, A and B. Native A says, “B is a knight equals I am not a knight”. What can you determine about A and B?

This problem involves a so-called negation: the use of “not”. Negation is a unary operator (meaning that it is a function with exactly one argument) mapping a boolean to a boolean, and is denoted by the symbol “¬”, written as a prefix to its argument. If p is a boolean expression, “¬p” is pronounced “not p”.

Using the general rule that if A makes a statement S, we know that A ≡ S, we get, for this problem,

A ≡ B ≡ ¬A.

(We switch from “=” to “≡” here in order to exploit associativity.) The goal is to simplify this expression.

In order to tackle this problem, it is necessary to begin by formulating calculational rules for negation. For arbitrary proposition p, the law governing ¬p is:

Reading this as

¬p = (p ≡ false),

it functions as a definition of negation. Reading it the other way,

(¬p ≡ p) = false,

it provides a way of simplifying propositional expressions. In addition, the symmetry of equivalence means that we can rearrange the terms in a continued equivalence in any order we like. So we also get the property

p = (¬p ≡ false).

Returning to the knights-and-knaves problem, we are given that

A ≡ B ≡ ¬A.

This simplifies to ¬B as follows:

A ≡ B ≡ ¬A

= { rearranging terms }

¬A ≡ A ≡ B

= { law (5.3) with p := A }

false ≡ B

= { law (5.3) with p := B and rearranging }

¬B.

So, B is a knave, but A could be a knight or a knave. Note how (5.3) is used in two different ways.

The law (5.3), in conjunction with the symmetry and associativity of equivalence, provides a way of simplifying continued equivalences in which one or more terms are repeated and/or negated. Suppose, for example, we want to simplify

¬p ≡ p ≡ q ≡ ¬p ≡ r ≡ ¬q.

We begin by rearranging all the terms so that repeated occurrences of “p” and “q” are grouped together. Thus we get

¬p ≡ ¬p ≡ p ≡ q ≡ ¬q ≡ r.

Now we can use (5.2) and (5.3) to reduce the number of occurrences of “p” and “q” to at most one (possibly negated). In this particular example we obtain

true ≡ p ≡ false ≡ r.

Finally, we use (5.2) and (5.3) again. The result is that the original formula is simplified to

¬p ≡ r.

Just as before, this process can be compared with the simplification of an arithmetic expression involving continued addition, where now negative terms may also appear. The expression

p + (−p) + q + (−p) + r + q + (−q) + r + p

is simplified to

q + 2r

by counting all the occurrences of p, q and r, an occurrence of −p cancelling out an occurrence of p. Again, the details are different but the process is essentially identical.

The two laws (5.2) and (5.3) are all that is needed to define the way that negation interacts with equivalence; using these two laws, we can derive several other laws. A simple example of how these two laws are combined is a proof that ¬false = true:

¬false

= { law ¬p ≡ p ≡ false with p := false }

false ≡ false

= { law true ≡ p ≡ p with p := false }

true.

5.4.1 Contraposition

A rule that should now be obvious, but which is surprisingly useful, is the rule we call contraposition.3

The name refers to the use of the rule in the form (p ≡ q) = (¬p ≡ ¬q).

We used the rule of contraposition implicitly in the river-crossing problems (see Chapter 3). Recall that each problem involves getting a group of people from one side of a river to another, using one boat. If we let n denote the number of crossings, and  denote the boolean “the boat is on the left side of the river”, a crossing of the river is modelled by the assignment

denote the boolean “the boat is on the left side of the river”, a crossing of the river is modelled by the assignment

n,  := n+1, ¬

:= n+1, ¬ .

.

In words, the number of crossings increases by one, and the boat changes side. The rule of contraposition tells us that

even(n) ≡

is invariant under this assignment. This is because

(even(n) ≡  )[n,

)[n,  := n+1, ¬

:= n+1, ¬ ]

]

= { rule of substitution }

even(n+1) ≡ ¬

= { even(n+1)

= { distributivity }

even(n) ≡ even(1)

= { even(1) ≡ false }

even(n) ≡ false

= { negation }

¬(even(n)) }

¬(even(n)) ≡ ¬

= { contraposition }

even(n) ≡  .

.

We are given that, initially, the boat is on the left side. Since zero is an even number, we conclude that even(n) ≡  is invariantly

is invariantly true. In words, the boat is on the left side equivales the number of crossings is even.

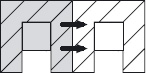

Another example is the following. Suppose it is required to move a square armchair sideways by a distance equal to its own width (see figure 5.1). However, the chair is so heavy that it can only be moved by rotating it through 90° around one of its four corners. Is it possible to move the chair as desired? If so, how? If not, why not?

Figure 5.1: Moving a heavy armchair.

Figure 5.1: Moving a heavy armchair.

The answer is that it is impossible. Suppose the armchair is initially positioned along a north–south axis. Suppose, also, that the floor is painted alternately with black and white squares, like a chess board, with each of the squares being the same size as the armchair. (see Figure 5.2). Suppose the armchair is initially on a black square. The requirement is to move the armchair from a north–south position on a black square to a north–south position on a white square.

Now, let boolean col represent the colour of the square that the armchair is on (say, true for black and false for white), and dir represent the direction that the armchair is facing (say, true for north–south and false for east–west). Then, rotating the armchair about any corner is represented by the assignment

col, dir := ¬col, ¬dir

The rule of contraposition states that an invariant of this assignment is

col ≡ dir.

So the value of this expression will remain equal to its initial value, no matter how many times the armchair is rotated. But, moving the armchair sideways one square changes the colour but does not change the direction. That is, it changes the value of col ≡ dir, and is impossible to achieve by continually rotating the armchair as prescribed.

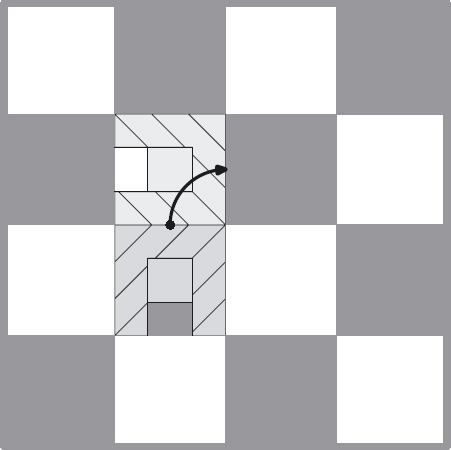

Figure 5.2: Invariant when moving a heavy armchair.

Figure 5.2: Invariant when moving a heavy armchair.

In words, an invariant of rotating the armchair through 90° around a corner point is

the chair is on a black square ≡ the chair is facing north–south

which is false when the chair is on a white square and facing north–south.

Exercise 5.7 (Knight’s Move) In the game of chess, a knight’s move is two places up or down and one place left or right, or two places left or right and one place up or down. A chessboard is an 8×8 grid of squares.

Show that it is impossible to move a knight from the bottom-left corner of a chessboard to the top-right corner in such a way that every square on the board is visited exactly once.

Hint: How many moves have to be made? Model a move in terms of the effect on the number of moves and the colour of the square on which the knight is standing; identify a relation between the two that is invariant under a move.

5.4.2 Handshake Problems

Logical properties of negation are fundamental to solving so-called handshake problems.

The simplest example of a handshake problem is this: Suppose that at a party, some people shake hands and some do not. Suppose each person counts the number of times they shake hands. Show that at least two people have the same count.

Crucial to how we solve this problem are the properties of shaking hands. These are that it is a binary relation; it is symmetric, and it is anti-reflexive. It being a “binary relation” on people, means that, for any two people – Jack and Jill, say – Jack shakes hands with Jill is either true or false. (In general, a relation is any boolean-valued function. Binary means that it is a function of two arguments.) It being a “symmetric” relation means that, for any two people – Jack and Jill, say – Jack shakes hands with Jill equivales Jill shakes hands with Jack. Finally, it being “anti-reflexive” means that no one shakes hands with themselves.

Refer to Section 12.7 for a basic introduction to binary relations and their properties.

Refer to Section 12.7 for a basic introduction to binary relations and their properties.

We are required to show that (at least) two people shake hands the same number of times. Let us explore the consequences of the properties of the shake-hands relation with respect to the number of times that each person shakes hands.

Suppose there are n people. Then, everyone shakes hands with at most n people. However, the anti-reflexivity property is that no one shakes hands with themselves. We conclude that everyone shakes hands with between 0 and n−1 people.

There are n numbers in the range 0 thru n−1. The negation of “two people shake hands the same number of times” is “everyone shakes hands a distinct number of times”. In particular, someone shakes hands 0 times and someone shakes hands n−1 times. The symmetry of the shake-hands relation makes this impossible.

Suppose we abbreviate “shake hands” to S, and suppose we use x and y to refer to people. In this way, xSy is read as “person x shakes hands with person y”, or just x shakes hands with y. Then the symmetry of “shakes hands” gives us the rule, for all x and y,

xSy ≡ ySx.

The contrapositive of this rule is that, for all x and y,

¬(xSy) ≡ ¬(ySx).

In words, x does not shake hands with y equivales y does not shake hands with x. Now, suppose person a shakes hands with no one and person b shakes hands with everyone. Then, in particular, a does not shake hands with b, that is, ¬(aSb) has the value true, and b shakes hands with a, that is, bSa also has the value true. But then, substituting equals for equals, we have that aSb has both the value false (because of the contrapositive of the symmetry of S and the fact that ¬(aSb) has the value true) and true (because bSa has the value true and S is symmetric). This is impossible.

The assumption that everyone shakes hands with a distinct number of people has led to a contradiction, and so we conclude that two people must shake hands the same number of times.

Note carefully how the symmetry and anti-reflexivity of the shakes-hands relation are crucial. Were we to consider a similar problem involving a different relation, the outcome might be different. For example, if we replace “shake hands” by some other form of greeting like “bows or curtsies”, which is not symmetric, the property need not hold. (Suppose there are two people, and one bows to the other, but the greeting is not returned.) However, if “shake hands” is replaced by “rub noses”, the property does hold. Like “shake hands”, “rub noses” is a symmetric and anti-reflexive relation.

Exercise 5.8 Here is another handshaking problem. It is a little more difficult to solve, but the essence of the problem remains the same: “shake hands” is a symmetric relation, as is “do not shake hands”.

Suppose a number of couples (husband and wife) attend a party. Some people shake hands, others do not. Husband and wife never shake hands. One person, the “host”, asks everyone else how many times they have shaken hands, and gets a different answer every time. How many times did the host and the host’s partner shake hands?

5.4.3 Inequivalence

In the knights-and-knaves problem mentioned at the beginning of Section 5.4, A might have said “B is different from myself”. This statement is formulated as B ≠ A, or ¬(B = A). This is, in fact, the same as saying “B is a knight equals I am not a knight”, as the following calculation shows (note that we switch from “=” to “≡” once again, in order to exploit associativity):

¬(B ≡ A)

= { [ ¬p ≡ p ≡ false ] with p := (B ≡ A) }

B ≡ A ≡ false

= { [ ¬p ≡ p ≡ false ] with p := A }

B ≡ ¬A.

We have thus proved, for all propositions p and q,

Note how associativity of equivalence has been used silently in this calculation. Note also how associativity of equivalence in the summary of the calculation gives us two properties for the price of one. The first is the one proved directly,

[ ¬(p ≡ q) = (p ≡ ¬q) ],

and the second comes free with associativity,

[ (¬(p ≡ q) ≡ p) = ¬q ].

The proposition ¬(p ≡ q) is usually written p  q. The operator is called inequivalence (or exclusive-or, abbreviated xor).

q. The operator is called inequivalence (or exclusive-or, abbreviated xor).

Calling inequivalence “exclusive-or” can be misleading because p

Calling inequivalence “exclusive-or” can be misleading because p  q

q  r does not mean that “exclusively” one of p, q and r is

r does not mean that “exclusively” one of p, q and r is true. On the contrary, true

true

true simplifies to true. We occasionally use this name, but only when the operator has two arguments.

Inequivalence is also associative:

(p  q)

q)  r

r

= { definition of “ ”, applied twice }

”, applied twice }

¬(¬(p ≡ q) ≡ r)

= { (5.9), with p,q := ¬(p ≡ q), r }

¬(p ≡ q) ≡ ¬r

= { contraposition (5.6), with p,q := p ≡ q, r }

p ≡ q ≡ r

= { contraposition (5.6), with p,q := p, q ≡ r }

¬p ≡ ¬(q ≡ r)

= { (5.9), with p,q := p, q ≡ r }

¬(p ≡ ¬(q ≡ r))

= { definition of “ ”, applied twice }

”, applied twice }

p  (q

(q  r).

r).

As a result, we can write the continued inequivalence p  q

q  r without fear of ambiguity.4 Note that, as a byproduct, we have shown that p

r without fear of ambiguity.4 Note that, as a byproduct, we have shown that p  q

q  r and p ≡ q ≡ r are equal.

r and p ≡ q ≡ r are equal.

We can now return to formulating a more “natural” question that enables gold to be found on the island of knights and knaves (see Section 5.2.4). Recall that, if L denotes “the gold can be found by following the left fork in the road” and A denotes “the native is a knight”, the question to be asked is: are L and A equal? The rule of contraposition combined with inequivalence allows the question to be formulated in terms of exclusive-or. We have:

We can now return to formulating a more “natural” question that enables gold to be found on the island of knights and knaves (see Section 5.2.4). Recall that, if L denotes “the gold can be found by following the left fork in the road” and A denotes “the native is a knight”, the question to be asked is: are L and A equal? The rule of contraposition combined with inequivalence allows the question to be formulated in terms of exclusive-or. We have:

L = A

= { contraposition }

¬L = ¬A

= { inequivalence and double negation }

L  ¬A .

¬A .

Expressing the inequivalence in the formula L  ¬A in terms of exclusive-or, the question becomes: “Of the two statements ‘the gold can be found by following the left fork’ and ‘you (the native) are a knave’ is one and only one of them true?”. Other formulations are, of course, possible.

¬A in terms of exclusive-or, the question becomes: “Of the two statements ‘the gold can be found by following the left fork’ and ‘you (the native) are a knave’ is one and only one of them true?”. Other formulations are, of course, possible.

As a final worked example, we show that inequivalence associates with equivalence:

(p  q) ≡ r

q) ≡ r

= { expanding the definition of p  q }

q }

¬(p ≡ q) ≡ r

= { ¬(p ≡ q) ≡ p ≡ ¬q }

p ≡ ¬q ≡ r

= { using symmetry of equivalence, the law (5.9)

is applied in the form ¬(p ≡ q) ≡ ¬q ≡ p

with p,q := q,r }

p ≡ ¬(q ≡ r)

= { definition of q  r }

r }

p ≡ (q  r) .

r) .

Exercise 5.10 Simplify the following. (Note that in each case it does not matter in which order you evaluate the subexpressions. Also, rearranging the variables and/or constants does not make any difference.)

(a) false

false

false

(b) true

true

true

true

(c) false

true

false

true

(d) p ≡ p ≡ ¬p ≡ p ≡ ¬p

(e) p  q ≡ q ≡ p

q ≡ q ≡ p

(f) p  q ≡ r ≡ p

q ≡ r ≡ p

(g) p ≡ p  ¬p

¬p  p ≡ ¬p

p ≡ ¬p

(h) p ≡ p  ¬p

¬p  p ≡ ¬p

p ≡ ¬p  ¬p

¬p

Exercise 5.11 (Encryption) The fact that inequivalence is associative, that is,

(p  (q

(q  r)) ≡ ((p

r)) ≡ ((p  q)

q)  r),

r),

is used to encrypt data. To encrypt a single bit b of data, a key a is chosen and the encrypted form of b that is transmitted is a  b. The receiver decrypts the received bit, c, using the same operation.5 That is, the receiver uses the same key a to compute a

b. The receiver decrypts the received bit, c, using the same operation.5 That is, the receiver uses the same key a to compute a  c. Show that, if bit b is encrypted and then decrypted in this way, the result is b independently of the key a.

c. Show that, if bit b is encrypted and then decrypted in this way, the result is b independently of the key a.

Exercise 5.12 On the island of knights and knaves, you encounter two natives, A and B. What question should you ask A to determine whether A and B are different types?

5.5 SUMMARY

In this chapter, we have used simple logic puzzles to introduce logical equivalence (the equality of boolean values), the most fundamental logical operator. Equivalence has the remarkable property of being associative, in addition to the standard properties of equality. Exploitation of the associativity of equivalence eliminates the tedious and ineffective case analysis that is often seen in solutions to logic puzzles.

The associativity of equivalence can be difficult to get used to, particularly if one tries to express its properties in natural language. However, this should not be used as an excuse for ignoring it. The painful, centuries-long process of accepting zero as a number, and introducing the symbol 0 to denote it, provides ample evidence that the adherence to “natural” modes of reasoning is a major impediment to effective reasoning. The purpose of a calculus is not to mimic “natural” or “intuitive” reasoning, but to provide a more powerful alternative.

5.6 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REMARKS

The fact that equality of boolean values is associative has been known since at least the 1920s, having been mentioned by Alfred Tarski in his PhD thesis, where its discovery is attributed to J. Lukasiewicz. (See the paper “On the primitive term of logistic” [Tar56]; Tarski and Lukasiewicz are both famous logicians.) Nevertheless, its usefulness was never recognised until brought to the fore by E.W. Dijkstra in his work on program semantics and mathematical method (see [DS90]).

The logic puzzles in Section 5.1 were taken from Raymond Smullyan’s book What Is the Name of This Book? [Smu78]. This is an entertaining book which leads on from simple logic puzzles to a discussion of the logical paradoxes and Gödel’s undecidability theorem. But Smullyan’s proofs often involve detailed case analyses and use traditional “if and only if” arguments. The exploitation of the associativity of equivalence in the solution of such puzzles is due to Gerard Wiltink [Wil87]. For a complete account of calculational logic, see [GS93].

1Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) was a famous German philosopher and mathematician.

2An infix operator is a symbol used to denote a function of two arguments that is written between the two arguments. The symbols “+” and “×” are both infix operators, denoting addition and multiplication, respectively.

3Other authors use the name “contraposition” for a less general rule combining negation with implication.

4This is to be read associatively, and should not be confused with p ≠ q ≠ r, which some authors occasionally write. Inequality is not transitive, so such expressions should be avoided.

5This operation is usually called “exclusive-or” in texts on data encryption; it is not commonly known that exclusive-or and inequivalence are the same. Inequivalence can be replaced by equivalence in the encryption and decryption process. But very few scientists and engineers are aware of the algebraic properties of equivalence, and this possibility is never exploited!