Chapter 15. Server Accelerator Mode

Throughout most of this book, I’ve been talking about Squid as a client-side caching proxy. However, with just a few special squid.conf settings, Squid is able to function as an origin server accelerator as well. In this mode, it accepts normal HTTP requests and forwards cache misses to the real origin server (or backend server). In the parlance of RFC 3040, Squid is operating as a surrogate. This configuration is similar to what I talked about in Chapter 9. The primary difference is that, as a surrogate, Squid accepts requests for one, or maybe a few, origin server(s), rather than any and all origins. HTTP interception isn’t required for server acceleration.

As the name implies, server acceleration is generally used as a technique to improve the performance of slow, or heavily loaded, backend servers. It works well because origin servers tend to have a relatively small hot set. Most likely, the objects responsible for 90% of origin server traffic can fit entirely in memory. Depending on your particular backend server software and configuration, Squid may be able to serve requests much faster.

Security is another good reason to consider Squid as a surrogate. Think of Squid as a dedicated firewall in front of your origin server. The Squid source code is too large to be trusted as completely secure. However, you may sleep better with Squid protecting your backend server. It is simply a cache, so it doesn’t permanently store the source of your data. If the Squid box is attacked or compromised, you won’t lose any data. You may find it easier to secure a system running Squid than the system running your backend server application(s).

You might also be interested in server acceleration to implement load balancing. If your origin server runs on expensive boxes, you can save money by deploying Squid on a number of cheaper boxes. By placing Squid at a number of different locations, you can even build your own content delivery network (CDN).

Overview

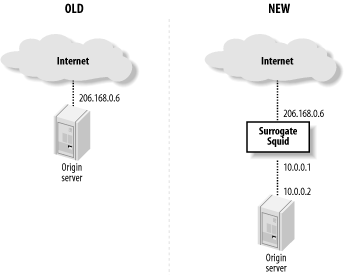

Assuming that you already have an origin server in place, you need to move it to a different IP address or TCP port. For example, you can (1) install Squid on a separate machine, (2) give the origin server a new IP address, and (3) give Squid the origin server’s old IP address. In the interest of security, you can use non-globally routable addresses (i.e., from RFC 1918) on the link between Squid and the backend server. See Figure 15-1.

Another option is to configure Squid for HTTP interception, as described in Chapter 9. For example, you can configure the origin server’s nearest router or switch to intercept HTTP requests and divert them to Squid.

If you don’t have the resources to put Squid on a dedicated system, you can run it alongside the HTTP server. However, both applications can’t share the same IP address and port number. You need to make the backend server bind to a different address (e.g., 127.0.0.1) or move it to another port number. It might seem easiest to change the port number, but I recommend changing the IP address instead.

Changing the port number can be problematic. For example, when the backend server

generates an error message, it may expose the “wrong” port. Even worse,

if the server generates an HTTP redirect, it typically appends the

nonstandard port number to the Location URI:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently Date: Mon, 29 Sep 2003 03:36:13 GMT Server: Apache/1.3.26 (Unix) Location: http://www.squid-cache.org:81/Doc/

If a client receives this response, it makes a connection to the nonstandard port (81), thus bypassing the server accelerator. If you must run Squid on the same host as your backend server, it is better to tell the backend server to listen on the loopback address (127.0.0.1). With Apache, you’d do it like this:

BindAddress 127.0.0.1 ServerName www.squid-cache.org

Once you’ve decided how to relocate your origin server, the next step is to configure Squid.

Configuring Squid

Technically, a single configuration file directive is all it takes to change Squid from a caching proxy into a surrogate. Unfortunately, life is never quite that simple. Due to the myriad of ways that different organizations design their web services, Squid has a number of directives to worry about.

http_port

Most likely, Squid is acting as a surrogate for your HTTP server on port 80. Use the http_port directive to make Squid listen on that port:

http_port 80

If you want Squid to act as surrogate and a caching proxy at the same time, list both port numbers:

http_port 80 http_port 3128

You can configure your clients to send their proxy requests to port 80 as well, but I strongly discourage that. By using separate ports, you’ll find it easier to migrate the two services to separate boxes later if it becomes necessary.

https_port

You can configure Squid to terminate encrypted HTTP (SSL and TLS) connections. This feature

requires the —enable-ssl option when running ./configure. In this mode, Squid decrypts

SSL/TLS connections from clients and forwards unencrypted requests to

your backend server. The https_port directive has

the following format:

https_port [host:]port cert=certificate.pem [key=key.pem] [version=1-4]

[cipher=list] [options=list]The cert and key arguments are pathnames to

OpenSSL-compatible certificate and private key files. If you omit the

key argument, the OpenSSL library

looks for the private key in the certificate file.

The (optional) version

argument specifies your requirements for various SSL and TLS protocols

to support: 1=automatic, 2=SSLv2 only, 3=SSLv3 only, 4=TLSv1

only.

The (optional) cipher

argument is a colon-separated list of ciphers. Squid simply passes it

to the SSL_CTX_set_cipher_list( ) function. For more

information, read the ciphers(1)

manpage on your system or try running: openssl ciphers.

The (optional) options

argument is a colon-separated list of OpenSSL options. Squid simply

passes these to the SSL_CTX_set_options( ) function. For more information,

read the SSL_CTX_set_options(3)

manpage on your system.

Here are a few example https_port lines:

https_port 443 cert=/usr/local/etc/certs/squid.cert https_port 443 cert=/usr/local/etc/certs/squid.cert version=2 https_port 443 cert=/usr/local/etc/certs/squid.cert cipher=SHA1 https_port 443 cert=/usr/local/etc/certs/squid.cert options=MICROSOFT_SESS_ID_BUG

httpd_accel_host

This is where you tell Squid the IP address, or hostname, of the backend server. If you use the loopback trick described previously, you write:

httpd_accel_host 127.0.0.1

Squid then prepends this value to partial URIs that get

accelerated. It also changes the value of the Host header.[1] For example, if the client makes this request:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: squidbook.org

Squid turns it into this request:

GET http://127.0.0.1/index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: 127.0.0.1

As you can see, the request no longer contains any information that indicates the request is for http://squidbook.org. This shouldn’t be a problem as long as the backend server isn’t configured for virtual hosting of multiple domains.

If you want Squid to use the origin server’s hostname, you can put it in the httpd_accel_host directive:

httpd_accel_host squidbook.org

Then the request is as follows:

GET http://squidbook.org/index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: squidbook.org

Another option is to enable the

httpd_accel_uses_host_header directive. Squid

then inserts the Host header value

into the URI for most requests, and the

httpd_accel_host value is used only for requests

that lack a Host header.

When you use a hostname, Squid goes through the normal steps to look up its IP address. Because you want the hostname to resolve to two different addresses (one for clients connecting to Squid and another for Squid connecting to the backend server), you should also add a static DNS entry to your system’s /etc/hosts file. For example:

127.0.0.1 squidbook.org

You might want to use a redirector instead. For example, you can

write a simple Perl program that changes http://squidbook.org/... to http://127.0.0.1/.... See Chapter 11 for the nuts and bolts of

redirecting client requests.

The httpd_accel_host directive has a

special value. If you set it to virtual, Squid inserts the origin server’s

IP address into the URI when the Host header is missing. This feature is

useful only when using HTTP interception, however.

httpd_accel_port

This directive tells Squid the port number of the backend server. It is 80 by default. You won’t need to change this unless the backend server is running on a different port. Here is an example:

httpd_accel_port 8080

If you are accelerating origin servers on multiple ports, you

can use the value 0. In this case,

Squid takes the port number from the Host header.

httpd_accel_uses_host_header

This directive controls how Squid determines the hostname it inserts into accelerated

URIs. If enabled, the request’s Host header value takes precedence over

httpd_accel_host.

The httpd_accel_uses_host_header directive goes hand in hand with virtual domain hosting on the backend server. You can leave it disabled if the backend server is handling only one domain. If, on the other hand, you are accelerating multiple origin server names, turn it on:

httpd_accel_uses_host_header on

If you enable httpd_accel_uses_host_header, be sure to install some access controls as described later in this chapter. To understand why, consider this configuration:

httpd_accel_host does.not.exist httpd_accel_uses_host_header on

Because most requests have a Host header, Squid ignores the

httpd_accel_host setting and rarely inserts the

bogus http://does.not.exist name into URIs. This

essentially turns your surrogate into a caching proxy for anyone smart

enough to fake an HTTP request. If I know that you are using Squid as

a surrogate without proper access controls, I can send a request like

this:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: www.mrcranky.com

If you’ve enabled httpd_accel_uses_host_header and don’t have any destination-based access controls, Squid should forward my request to http://www.mrcranky.com. Read Section 15.4 and install access controls to ensure that Squid doesn’t talk to foreign origin servers.

httpd_accel_single_host

Whereas the httpd_accel_uses_host_header directive determines the hostname Squid puts into a URI, this one determines where Squid forwards its cache misses. By default (i.e., with httpd_accel_single_host disabled), Squid forwards surrogate cache misses to the host in the URI. If the URI contains a hostname, Squid performs a DNS lookup to get the backend server’s IP address.

When you enable httpd_accel_single_host,

Squid always forwards surrogate cache misses to the host defined by

httpd_accel_host. In other words, the contents of

the URI and the Host header don’t

affect the forwarding decision. Perhaps the best reason to enable this

directive is to avoid DNS lookups. Simply set

httpd_accel_host to the backend server’s IP

address. Another reason to enable it is if you have another device

(load balancer, virus scanner, etc.) between Squid and the backend

server. You can make Squid forward the request to this other device

without changing any aspect of the HTTP request.

Note that enabling both httpd_accel_single_host and httpd_accel_uses_host_header is a dangerous combination that might allow an attacker to poison your cache. Consider this configuration:

httpd_accel_single_host on httpd_accel_host 172.16.1.1 httpd_accel_uses_host_header on

and this HTTP request:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.0 Host: www.othersite.com

Squid forwards the request to your backend server at 172.16.1.1 but stores the response under the URI http://www.othersite.com/index.html. Since 172.16.1.1 isn’t actually www.othersite.com, Squid now contains a bogus response for that URI. If you enable httpd_accel_with_proxy (next section) or your cache participates in a hierarchy or mesh, it may give out the bad response to unsuspecting users. To prevent such abuse, be sure to read Section 15.4.

Server-side persistent connections may not work if you use the httpd_accel_single_host directive. This is because Squid saves idle connections under the origin server hostname, but the connection-establishment code looks for an idle connection named by the httpd_accel_host value. If the two values are different, Squid fails to locate an appropriate idle connection. The idle connections are closed after the timeout, without being reused. You can avoid this little problem by disabling server-side persistent connections with the server_persistent_connections directive (see Appendix A).

httpd_accel_with_proxy

By default, whenever you enable the httpd_accel_host directive, Squid goes into strict surrogate mode. That is, it refuses proxy HTTP requests and accepts only surrogate requests, as though it were truly an origin server. Squid also disables the ICP port (although not HTCP, if you have it enabled). If you want Squid to accept both surrogate and proxy requests, enable this directive:

httpd_accel_with_proxy on

Gee, That Was Confusing!

Yeah, it was for me too. Let’s look at it another way. The settings that you need to use depend on how many backend boxes you have and how many origin server names you are accelerating. Let’s consider the four separate cases in the following sections.

One Box, One Server Name

This is the simplest sort of configuration. Because you have

only one box and one hostname, the Host header values don’t matter much. You

should probably use:

httpd_accel_host www.example.com httpd_accel_single_host on httpd_accel_uses_host_header off

If you like, you can use an IP address for httpd_accel_host, although it will appear in URIs in your access.log.

One Box, Many Server Names

Because you have many origin server names being virtually hosted

on a single box, the Host header

becomes important. We want Squid to insert it into the URIs it

generates from partial requests. Your configuration should be:

httpd_accel_host www.example.com httpd_accel_single_host on httpd_accel_uses_host_header on

In this case, Squid generates the URI based on the Host header. If absent, Squid inserts

www.example.com. You can disable

httpd_accel_single_host if you prefer. As before,

you can use an IP address in httpd_accel_host to

avoid DNS lookups.

Many Boxes, One Server Name

This sounds like a load-balancing configuration. One way to accomplish it is to create a DNS name for the backend servers with multiple IP addresses. Squid iterates between all addresses (a.k.a. round-robin) for each cache miss. In this situation, the configuration is the same as for the one box/one name case:

httpd_accel_host roundrobin.example.com httpd_accel_single_host on httpd_accel_uses_host_header off

The only difference is that the httpd_accel_host name resolves to multiple addresses. It might look like this in a Berkeley Internet Name Daemon (BIND) zone file:

$ORIGIN example.com.

roundrobin IN A 192.168.1.2

IN A 192.168.1.3

IN A 192.168.1.4With this DNS configuration, Squid uses the next address in the list each time it opens a new connection to roundrobin.example.com. When it gets to the end of the list, it starts over at the top. Note that Squid caches these DNS answers internally according to their TTLs. You aren’t relying on the name server to return the address list in a different order for each DNS query.

Another option is to use a redirector (see Chapter 11) to select the backend server. You can write a simple script to replace the URI hostname (e.g., roundrobin.example.com) with a different hostname or an IP address. You might even make the redirector smart enough to make its selection based on the current state of the backend servers. Use the following configuration with this approach:

httpd_accel_host roundrobin.example.com httpd_accel_single_host off httpd_accel_uses_host_header off

Many Boxes, Many Server Names

In this case, you want to use the Host header. You also want Squid to select

the backend server based on the origin server’s name (i.e., a DNS

lookup). The configuration is as follows:

httpd_accel_host www.example.com httpd_accel_single_host off httpd_accel_uses_host_header on

You might be tempted to set

httpd_accel_host to virtual. However, that would be a mistake

unless you are using HTTP interception.

Access Controls

A typically configured surrogate accepts HTTP requests from the whole Internet. This doesn’t mean, however, that you can forget about access controls. In particular, you’ll want to make sure Squid doesn’t accept requests belonging to foreign origin servers. The exception is when you have httpd_accel_with_proxy enabled.

For a surrogate-only configuration, use one of the destination-based access controls. For example, the dst type accomplishes the task:

acl All src 0/0 acl TheOriginServer dst 192.168.3.2 http_access allow TheOriginServer http_access deny All

Alternatively, you can use a dstdomain ACL if you prefer:

acl All src 0/0 acl TheOriginServer dstdomain www.squidbook.org http_access allow TheOriginServer http_access deny All

Note that enabling httpd_accel_single_host somewhat bypasses the access control rules. This is because the origin server location (i.e., the httpd_accel_host value) is then set after Squid performs the access control checks.

Access controls become really tricky when you combine surrogate and proxy modes in a single instance of Squid. You can no longer simply deny all requests to foreign origin servers. You can, however, make sure that outsiders aren’t allowed to make proxy requests to random origin servers. For example:

acl All src 0/0 acl ProxyUsers src 10.2.0.0/16 acl TheOriginServer dst 192.168.3.2 http_access allow ProxyUsers http_access allow TheOriginServer http_access deny All

You can also use the local port number in your access control rules. It doesn’t really protect you from malicious activity, but does ensure, for example, that user-agents send their proxy requests to the appropriate port. This also makes it easier for you to split the service into separate proxy- and surrogate-only systems later. Assuming you configure Squid to listen on ports 80 and 3128, you might use:

acl All src 0/0 acl ProxyPort myport 3128 acl ProxyUsers src 10.2.0.0/16 acl SurrogatePort myport 80 acl TheOriginServer dst 192.168.3.2 http_access allow ProxyUsers ProxyPort http_access allow TheOriginServer SurrogatePort http_access deny All

Unfortunately, these access control rules don’t prevent attempts to poison your cache when you enable httpd_accel_single_host, httpd_accel_uses_host_header, and httpd_accel_with_proxy simultaneously. This is because the valid proxy request:

GET http://www.bad.site/ HTTP/1.1 Host: www.bad.site

and the bogus surrogate request:

GET / HTTP/1.1 Host: www.bad.site

have the same access control result but are forwarded to different servers. They have the same access control result because, after Squid rewrites the surrogate request, it has the same URI as the proxy request. However, they don’t get sent to the same place. The surrogate request goes to the server defined by httpd_accel_host because httpd_accel_single_host is enabled.

You can take steps towards solving this problem. Make sure your

backend server generates an error for unknown server names (e.g., when

the Host header refers to a nonlocal

server). Better yet, don’t run Squid as a surrogate and proxy at the

same time.

Content Negotiation

Recent versions of Squid support the HTTP/1.1 Vary header. This is good news if your backend

server uses content negotiation. It might, for example, send different

responses depending on which web browser makes the request (e.g., the

User-Agent header), or based on the

user’s language preferences (e.g., the Accept-Language header).

When the response for a URI varies on some aspect of the request,

the origin (backend) server includes a Vary header. This header contains the list of

request headers used to select the variant. These are the

selecting headers. When Squid receives a response

with a Vary header, it includes the

selecting header values when it generates the internal cache key. Thus,

a subsequent request with the same values for the selecting headers may

generate a cache hit.

If you use the —enable-x-accelerator-vary option

when running ./configure, Squid looks

for a response header named X-Accelerator-Vary. Squid treats this header

exactly like the Vary header. Because

this is an extension header, however, it is ignored by downstream

agents. It essentially provides a means for private content negotiation

between Squid and your backend server. In order to use it you must also

modify your server application to send the header in its responses. I

don’t know of any situation in which this header would be useful. If you

serve negotiated responses, you probably want to use the standard

Vary header so that all agents know

what’s going on.

Gotchas

Using Squid as a surrogate may improve your origin server’s security and performance. However, there are some potentially negative side effects as well. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

Logging

When using a surrogate, the origin server’s access log contains only the cache misses from Squid. Furthermore, those log-file entries have Squid’s IP address, rather than the client’s. In other words, Squid’s access.log is where all the good information is now stored.

Recall that, by default, Squid doesn’t use the common log-file format. You should use the emulate_httpd_log directive to make Squid’s access.log look just like Apache’s default log-file format.

Ignoring Reloads

The Reload button found on most browsers generates HTTP requests with the Cache-Control: no-cache directive set. While this is

usually desirable for client-side caching proxies, it may ruin the

performance of a surrogate. This is especially true if the backend

server is heavily loaded. A reload request forces Squid to purge the

currently cached response while retrieving the new response from the

origin server. If those origin server responses arrive slowly, Squid

consumes a larger than normal number of file descriptors and network

resources.

To help in this situation, you may want to use one of the

refresh_pattern options. When the ignore-reload option is set, Squid pretends

that the request doesn’t contain the no-cache directive. The ignore-reload option is generally safe for

surrogates, although it does, technically, violate the HTTP

protocol.

To make Squid ignore reloads for all requests, use a line like this in squid.conf:

refresh_pattern . 0 20% 4320 ignore-reload

For a somewhat safer alternative, you can use the reload-into-ims option. It causes Squid to

validate its cached response when the request contains no-cache. Note, however, that this works

only for responses that have cache validators (such as Last-Modified timestamps).

Uncachable Content

As a surrogate, Squid obeys the standard HTTP headers for caching responses from your backend server. This means, for example, that certain dynamic responses might not be cached. You might want to use the refresh_pattern directive to force caching of these objects. For example:

refresh_pattern \.dhtml$ 60 80% 180

This trick only works for certain types of responses, namely,

those without a Last-Modified or

Expires header. By default, Squid

doesn’t cache such responses. However, using a nonzero minimum time in

a refresh_pattern rule instructs Squid to cache

the response, and serve it as a cache hit for that amount of time

anyway. See Section 7.7 for

the details.

If your backend server generates other types of uncachable responses, you may not be able to trick Squid into storing them.

Errors

With Squid as a surrogate in front of your origin server, you should be aware that visitors to your site may see an error message from Squid, rather than the origin server itself. In other words, your use of Squid may be “exposed” through certain error messages. For example, Squid returns its own error message when it fails to parse the client’s HTTP request, which could happen if the request is incomplete or is malformed in some way. Squid also returns an error message if it can’t connect to the backend server for some reason.

If your site is consistent and functioning properly, you probably don’t need to worry about Squid’s error messages. Nonetheless, you may want to take a close look at the access.log from time to time and see what sort of errors, if any, your users might be seeing.

Purging Objects

You may find the PURGE method

particularly useful when operating a surrogate. Because

you have a good understanding of the content being served, you are

more likely to know when a cached object must be purged. The technique

for purging an object is the same as I mentioned previously. See Section 7.6 for a

refresher.

Neighbors

Although I don’t recommend it, you can configure Squid as a surrogate and as part of a mesh or hierarchy. If you choose to take on such an arrangement, note that, by default, Squid forwards cache misses to parents (rather than the backend server). Assuming that isn’t what you really want, be sure to use the cache_peer_access directives so that requests for your backend server don’t go to your neighbors instead.

Exercises

Install and configure Squid as a surrogate on the same system where you run an HTTP server.

Make a few test requests with squidclient. Pay particular attention to the reply headers and notice how the requests appear in both access logs.

Try to poison your own surrogate with fake HTTP requests. It is probably easier with httpd_accel_single_host enabled.

Estimate the size of your origin server’s document set. What percentage of the data can fit into 1 GB of memory or disk space?

[1] Technically, the Host

header is changed only in requests Squid forwards to the backend

server (cache misses).