Chapter 1. Introduction

This long-overdue book is about Squid: a popular open source caching proxy for the Web. With Squid you can:

Use less bandwidth on your Internet connection when surfing the Web

Reduce the amount of time web pages take to load

Protect the hosts on your internal network by proxying their web traffic

Collect statistics about web traffic on your network

Prevent users from visiting inappropriate web sites at work or school

Ensure that only authorized users can surf the Internet

Enhance your user’s privacy by filtering sensitive information from web requests

Reduce the load on your own web server(s)

Convert encrypted (HTTPS) requests on one side, to unencrypted (HTTP) requests on the other

Squid’s job is to be both a proxy and a cache. As a proxy, Squid is an intermediary in a web transaction. It accepts a request from a client, processes that request, and then forwards the request to the origin server. The request may be logged, rejected, and even modified before forwarding. As a cache, Squid stores recently retrieved web content for possible reuse later. Subsequent requests for the same content may be served from the cache, rather than contacting the origin server again. You can disable the caching part of Squid if you like, but the proxying part is essential.

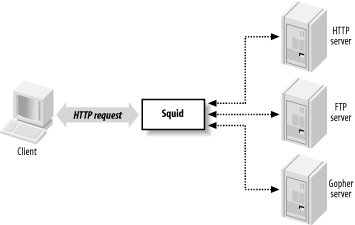

As Figure 1-1 shows, Squid accepts HTTP (and HTTPS) requests from clients, and speaks a number of protocols to servers. In particular, Squid knows how to talk to HTTP, FTP, and Gopher servers.[1] Conceptually, Squid has two “sides.” The client-side talks to web clients (e.g., browsers and user-agents); the server-side talks to HTTP, FTP, and Gopher servers. These are called origin servers, because they are the origin location for the data they serve.

Note that Squid’s client-side understands only HTTP (and HTTP encrypted with SSL/TLS). This means, for example, that you can’t make an FTP client talk to Squid (unless the FTP client is also an HTTP client). Furthermore, Squid can’t proxy protocols for email (SMTP), instant messaging, or Internet Relay Chat.

Web Caching

Web caching refers to the act of storing certain web resources (i.e., pages and other data files) for possible future reuse. For example, Matilda is the first person in the office each morning, and she likes to read the local newspaper online with her wake-up coffee. As she visits the various sections, the Squid cache on their office network stores the HTML pages and JPEG images. Harry comes in a short while later and also reads the newspaper online. For him, the site loads much faster because much of the content is served from Squid. Additionally, Harry’s browsing doesn’t waste the bandwidth of the company’s DSL line by transferring the exact same data as when Matilda viewed the site.

A cache hit occurs each time Squid satisfies an HTTP request from its cache. The cache hit ratio, or cache hit rate, is the percentage of all requests satisfied as hits. Web caches typically achieve hit ratios between 30% and 60%. A similar metric, the byte hit ratio, represents the volume of data (i.e., number of bytes) served from the cache.

A cache miss occurs when Squid can’t satisfy a request from the cache. A miss can happen for any number of reasons. Obviously, the first time Squid receives a request for a particular resource, it is a cache miss. Similarly, Squid may have purged the cached copy to make room for new objects.

Another possibility is that the resource is uncachable. Origin servers can instruct caches on how to treat the response. For example, they can say that the data must never be cached, can be reused only within a certain amount of time, and so on. Squid also uses a few internal heuristics to determine what should, or should not, be saved for future use.

Cache validation is a process that ensures Squid doesn’t serve stale data to the user. Before reusing a cached response, Squid often validates it with the origin server. If the server indicates that Squid’s copy is still valid, the data is sent from Squid. Otherwise, Squid updates its cached copy as it relays the response to the client. Squid generally performs validation using timestamps. The origin server’s response usually contains a last-modified timestamp. Squid sends the timestamp back to the origin server to find if the original resource has changed.

For a detailed treatment of web caching, have a look at my book Web Caching, also by O’Reilly.

A Brief History of Squid

In the beginning was the CERN HTTP server. In addition to functioning as an HTTP server, it was also the first caching proxy. The caching module was written by Ari Luotonen in 1994.

That same year, the Internet Research Task Force Group on Resource Discovery (IRTF-RD) started the Harvest project. It was “an integrated set of tools to gather, extract, organize, search, cache, and replicate” Internet information. I joined the Harvest project near the end of 1994. While most people used Harvest as a local (or distributed) search engine, the Object Cache component was quite popular as well. The Harvest cache boasted three major improvements over the CERN cache: faster use of the filesystem, a single process design, and caching hierarchies via the Internet Cache Protocol.

Towards the end of 1995, many Harvest team members made the move to the exciting world of Internet-based startup companies. The original authors of the Harvest cache code, Peter Danzig and Anawat Chankhunthod, turned it into a commercial product. Their company was later acquired by Network Appliance. In early 1996, I joined the National Laboratory for Applied Network Research (NLANR) to work on the Information Resource Caching (IRCache) project, funded by the National Science Foundation. Under this project, we took the Harvest cache code, renamed it Squid, and released it under the GNU General Public License.

Since that time Squid has grown in size and features. It now supports a number of cool things such as URL redirection, traffic shaping, sophisticated access controls, numerous authentication modules, advanced disk storage options, HTTP interception, and surrogate mode (a.k.a. HTTP server acceleration).

Funding for the IRCache project ended in July 2000. Today, a number of volunteers continue to develop and support Squid. We occasionally receive financial or other types of support from companies that benefit from Squid.

Looking towards the future, we are rewriting Squid in C++ and, at the same time, fixing a number of design issues in the older code that are limiting to new features. We are adding support for protocols such as Edge Side Includes (ESI) and Internet Content Adaptation Protocol (ICAP). We also plan to make Squid support IPv6. A few developers are constantly making Squid run better on Microsoft Windows platforms. Finally, we will add more and more HTTP/1.1 features and work towards full compliance with the latest protocol specification.

Hardware and Operating System Requirements

Squid runs on all popular Unix systems, as well as Microsoft Windows. Although Squid’s Windows support is improving all the time, you may have an easier time with Unix. If you have a favorite operating system, I’d suggest using that one. Otherwise, if you’re looking for a recommendation, I really like FreeBSD.

Squid’s hardware requirements are generally modest. Memory is often the most important resource. A memory shortage causes a drastic degradation in performance. Disk space is, naturally, another important factor. More disk space means more cached objects and higher hit ratios. Fast disks and interfaces are also beneficial. SCSI performs better than ATA, if you can justify the higher costs. While fast CPUs are nice, they aren’t critical to good performance.

Because Squid uses a small amount of memory for every cached response, there is a relationship between disk space and memory requirements. As a rule of thumb, you need 32 MB of memory for each GB of disk space. Thus, a system with 512 MB of RAM can support a 16-GB disk cache. Your mileage may vary, of course. Memory requirements depend on factors such as the mean object size, CPU architecture (32- or 64-bit), the number of concurrent users, and particular features that you use.

People often ask such questions as, “I have a network with X users. What kind of hardware do I need for Squid?” These questions are difficult to answer for a number of reasons. In particular, it’s hard to say how much traffic X users will generate. I usually find it easier to look at bandwidth usage, and go from there. I tell people to build a system with enough disk space to hold 3-7 days worth of web traffic. For example, if your users consume 1 Mbps (HTTP and FTP traffic only) for 8 hours per day, that’s about 3.5 GB per day. So, I’d say you want between 10 and 25 GB of disk space for each Mbps of web traffic.

Squid Is Open Source

Squid is free software and a collaborative project. If you find Squid useful, please consider contributing back to the project in one or more of the following ways:

Participate on the squid-users discussion list. Answer questions and help out new users.

Try out new versions and report bugs or other problems.

Contribute to the online documentation and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). If you notice an inconsistency, report it to the maintainers.

Submit your local modifications back to the developers for inclusion into the code base.

Provide financial support to one or more developers through small development contracts.

Tell the developers about features you would like to have.

Tell your friends and colleagues that Squid is cool.

Squid is released as free software under the GNU General Public License. This means, for example, that anyone who distributes Squid must make the source code available to you. See http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-faq.html for more information about the GPL.

Squid’s Home on the Web

The main source for up-to-date information about Squid is http://www.squid-cache.org. There you can:

Download the source code.

Read the FAQ and other documentation.

Subscribe to the mailing list, or read the archives.

Contact the developers.

Find links to third-party applications.

And more!

Getting Help

Given that Squid is free software, you may need to rely on the kindness of strangers for occasional assistance. The best place to do this is the squid-users mailing list. Before posting a message to the mailing list, however, you should check Squid’s FAQ document to see if your question has already been asked and answered. If neither resource provides the help you need, you can contact one of the many services offering professional support for Squid.

Frequently Asked Questions

Squid’s FAQ document, located at http://www.squid-cache.org/Doc/FAQ/FAQ.html, is a good source of information for new users. The FAQ evolves over time, so it will contain entries written after this book. The FAQ also contains some historical information that may be irrelevant today.

Even so, the FAQ is one of the first places you should look for answers to your questions. This is especially true if you are a new user. While it is certainly less effort for you to simply write to the mailing list for help, veteran mailing list members grow tired of reading and answering the same questions. If your question is frequently asked, it may simply be ignored.

The FAQ is quite large. The HTML version exists as approximately 25 different chapters, each in a separate file. These can be difficult to search for keywords and awkward to print. You can also download PostScript, PDF, and text versions by following links at the top of the HTML version.

Mailing Lists

Squid has three mailing lists you might find useful. I explain how to become a subscriber below, but you may want to check Squid’s mailing list page, http://www.squid-cache.org/mailing-lists.html, for possibly more up-to-date information.

squid-users

The squid-users mailing list is an excellent place to find answers for such questions as:

How do I ... ?

Is this a bug ... ?

Does this feature/program work on my platform?

What does this error message mean?

Note that you must subscribe before you can post a message. To subscribe to the squid-users list, send a message to squid-users-subscribe@squid-cache.org.

If you prefer, you can receive the digest version of the list. In this case, you’ll receive multiple postings in a single email message. To sign up this way, send a message to squid-users-digest-subscribe@squid-cache.org.

Once you subscribe, you can post a message to the list by writing to squid-users@squid-cache.org. If you have a question, consider checking the FAQ and/or mailing list archives first. You can browse the list archive by visiting http://www.squid-cache.org/mail-archive/squid-users/. However, if you are looking for something specific, you’ll probably have more luck with the search interface at http://www.squid-cache.org/search/.

squid-announce

The moderated squid-announce list is used to announce new Squid versions and important security updates. The volume is quite low, usually less than one message per month. Write to squid-announce-subscribe@squid-cache.org if you’d like to subscribe.

squid-dev

The squid-dev list is a place where Squid hackers and developers can exchange ideas and information. Anyone can post a message to squid-dev, but subscriptions are moderated. If you’d like to join the discussion, please send a message about yourself and your interests in Squid. One of the list members should subscribe you within a few days.

The squid-dev messages are archived at http://www.squid-cache.org/mail-archive/squid-dev/, where anyone may browse them.

Professional Support

A number of companies now offer professional assistance for Squid. They may be able to help you get started with Squid for the first time, recommend a configuration for your network environment, and even fix some bugs.

Some of the consulting companies are associated with core Squid developers. By giving them your business, you ensure that fixes and features will be committed to future Squid software releases. If necessary, you can also arrange for development of private features.

Visit http://www.squid-cache.org/Support/services.html for the list of professional support services.

Getting Started with Squid

If you are new to Squid, the next few chapters will help you get started. First, I’ll show you how to get the code, either the original source or precompiled binaries. In Chapter 3, I go through the steps necessary to compile and install Squid on your Unix system; this chapter is important because you’ll probably need to tune your system before compiling the source code. Chapter 4 provides a very brief introduction to Squid’s configuration file. Finally, Chapter 5 explains how to run Squid.

If you’ve already had a little experience installing and running Squid, you may want to skip ahead to Chapter 6.

Exercises

Visit the Squid site and locate the squid-users mailing list archive. Browse the messages for the past few weeks.

Search the Squid FAQ for information about file descriptors.

Check one of the Squid mirror sites. Is it up to date with the primary site?

[1] Gopher servers are quite rare these days. Squid also knows about WAIS and whois, but these are even more obscure.