Chapter 14. Monitoring Squid

How can you tell if Squid is performing well? Does Squid have enough memory, bandwidth, and disk space? When the Internet seems slow, is it Squid’s fault or a problem somewhere else? Is the operating system giving enough resources to Squid? Is someone trying to abuse or hack into my proxy? You can find the answers to these, and many more, questions in this chapter. Squid provides information about itself in three different ways: cache.log messages, the cache manager, and an SNMP MIB.

Squid writes various messages to cache.log as it runs. Most of these are abnormal events of one sort or another. Unfortunately, Squid isn’t always smart enough to differentiate serious problems from those that can be safely ignored. Even so, cache.log is a good place to start when investigating a Squid problem.

The cache manager and SNMP interfaces allow you to query Squid for a variety of data. The cache manager, which has its own shortcomings, probably provides the most information in current versions of Squid. It has a TCP socket-based interface and tries to generate output suitable for both human and computer processing. The bulk of this chapter is devoted to explaining all the information available from the cache manager.

Squid supports SNMP as well. Unfortunately, the data available through SNMP is only a subset of the cache-manager information. Additionally, the Squid MIB has not evolved much over the years; it’s essentially unchanged since its first incarnation. I’ll explain how to make Squid process SNMP queries and describe all objects in the current MIB.

cache.log Warnings

This is one of the first places you should look whenever you perceive a problem with Squid. During normal operation, you’ll find various warnings and informational messages that may or may not indicate a problem. I covered the mechanics of cache.log back in Section 13.1. Here, I’ll go over a few of the warning messages you might see in your log file.

The high_response_time_warning directive makes Squid print a warning whenever the median response time exceeds a threshold. The value is in milliseconds and is disabled by default. If you add this line to squid.conf:

high_response_time_warning 1500

Squid will print the following warning if the median response time, measured over a 1-minute interval, exceeds 1.5 seconds:

2003/09/29 03:17:31| WARNING: Median response time is 2309 milliseconds

Before setting this directive, you should have a good idea of Squid’s normal response time levels. If you set it too low, you’ll get false alarms. In this particular example, it means that half of your user’s requests take more than 2.3 second to complete. High response times may be caused by local problems, such as running out of file descriptors, or by remote problems, such as a severely congested Internet link.

The high_page_fault_warning directive is similar. It causes Squid to emit a warning if the number of page faults per minute exceeds a given value. A high page-fault rate usually indicates that the Squid process can’t fit entirely in memory and must be swapped out to disk. This swapping severely impacts Squid’s performance, so you should remedy the situation as soon as possible, as I’ll discuss in Section 16.1.8.

Squid uses the Unix getrusage( ) function to

get page fault counts. On some operating systems (e.g.,

Solaris), the page fault counter represents something besides swapping.

Therefore, the high_page_fault_warning may cause

false alarms on those systems.

The high_memory_warning directive is also similar to the previously mentioned warnings. In this case, it checks the size of the Squid process; if it exceeds the threshold, you get the warning in cache.log. On some operating systems, the process size can only grow and never shrink. Therefore, you’ll constantly get this warning until Squid shuts down.

Process size information comes from either the mallinfo( ), mstats( ), or sbrk( ) functions. If these are unavailable

on your operating system, the high_memory_warning

warning won’t work.

Squid has a number of other hardcoded warnings you may see in cache.log:

DNS lookup for 'neighbor.host.name' failed!This occurs whenever Squid fails to look up the IP address for a cache neighbor. Squid refreshes the neighbor addresses every hour or so. As long as the neighbor’s address is unknown, Squid doesn’t send any traffic there.

Detected DEAD Sibling: neighbor.host.name/3128/3130Squid logs this message when it believes it can’t communicate with a neighbor cache. This happens, for example, when too many consecutive ICP queries go unacknowledged. See Section 10.3.2 for more information.

95% of replies from 'neighbor.host.name' are UDP_DENIEDThis message indicates that a neighbor cache is refusing to answer Squid’s queries. It probably means that you are sending queries to the neighbor without their permission. If they are using address-based access controls, and you have recently changed your address, they won’t know about the change. Squid refuses to send any more queries to the neighbor after detecting this condition.

Probable misconfigured neighbor at 192.168.121.5This occurs when you have an unauthorized cache client sending you ICP or HTCP queries. The best thing to do in this case is try to find out the person or organization responsible for the given address. Ask why they are querying your cache.

Forwarding loop detected for:Recall that a forwarding loop occurs when a single request flows through Squid a second time. The request’s

Viaheader contains a list of all proxies that have seen the request. If Squid detects its own name in theVialist, it emits the forwarding loop warning and sends the request directly to the origin server. See Section 10.2 for an explanation of forwarding loops.Closing client 192.168.121.5 connection due to lifetime timeoutThe client_lifetime directive places an upper limit on the duration for a single HTTP request. Squid warns you when such a request is terminated because it may indicate someone is abusing your cache with very long-lived connections, for example, by downloading infinitely long objects.

As you can see, cache.log provides only notification of abnormal events. For periodic monitoring, you need something else. The cache manager is perhaps the best choice, even though its interface is less than perfect.

The Cache Manager

The Cache Manager is an interface to Squid for receiving information about various

components. It is accessed via normal HTTP requests with a special

protocol name: cache_object. A full

cache manager URL looks like

cache_object://cache.host.name/info. Squid provides

two easy ways to access the cache manager information: the command-line

squidclient program[1] or the cachemgr.cgi CGI

program.

The squidclient utility is a simple HTTP client, with a few special features for use with Squid. For example, you can use a shortcut to request the cache manager pages. Rather than typing a long URL like this:

% squidclient cache_object://cache.host.name/info

you can use this shorter version:

% squidclient mgr:info

squidclient is a convenient way to quickly see some of the cache manager pages. It’s also useful when you need to save the cache manager output to disk for later analysis. However, some pages, such as the memory utilization table, are difficult to read in a terminal window. They are really designed to be formatted as an HTML page and viewed with your web browser. In that case, you may want to use cachemgr.cgi.

To use cachemgr.cgi, you must have an HTTP server that can execute the program. You can use an existing server or install one alongside Squid if you prefer. Keep in mind that the cache manager has only weak security (cleartext passwords). If the HTTP server is on a different host, you need to add its IP address to a cache manager access list (see Section 14.2.2). You may also want to add access controls to the HTTP server so that others can’t access cachemgr.cgi.

If you use Apache, I recommend making a special cgi-bin directory so you can protect cachemgr.cgi with access controls. For example, create a new directory, and copy the binary to it:

# mkdir /usr/local/apache/squid-cgi # cp /usr/local/squid/libexec/cachemgr.cgi /usr/local/apache/squid-cgi # chmod 755 /usr/local/apache/squid-cgi/cachemgr.cgi

Now, add a ScriptAlias line to Apache’s httpd.conf:

ScriptAlias /squid-cgi/ "/usr/local/apache/squid-cgi/"

Finally, create an .htaccess file in the squid-cgi directory that contains access controls. To allow requests from only one IP address, use something like this:

Allow from 192.168.4.2 Deny from all

Once cachemgr.cgi is installed, simply enter the appropriate URL into your web browser. For example:

http://www.server.name/squid-cgi/cachemgr.cgi

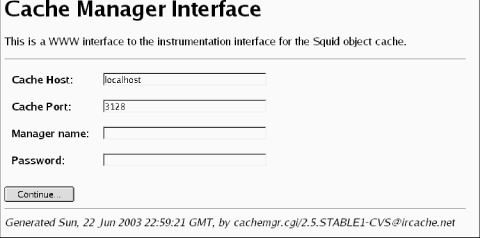

If the CGI program is working, you should see a page with four

fields. See Figure 14-1 for an

example. The Cache Host field contains the name of

the host on which Squid is running—localhost by

default. You can set it with the

—enable-cachemgr-hostname option when running ./configure. Similarly, Cache

Port contains the TCP port number to which Squid listens for

requests. It’s 3128 by default and can be changed with the

—enable-cachemgr-port option. The Manager

name and Password fields are for access

to protected pages, which I’ll talk about shortly.

After clicking on the Continue... button, you should see a list of all cache manager pages currently available. The following section describes the various pages, some of which are available only when you enable certain features at compile time.

Cache Manager Pages

This section describes the cache manager pages, in the same order in which they appear in the menu. Each section title has both the page name (for use with squidclient), followed by its description. Descriptions that contain an asterisk indicate pages that are disabled by default, unless you configure a password for them. Table 14-1 shows the table of contents and the section number for each page.

Short name | Description |

leaks | Memory Leak Tracking |

mem | Memory Utilization |

cbdata | Callback Data Registry Contents |

events | Event Queue |

squidaio_counts | Async IO Function Counters |

diskd | DISKD Stats |

config | Current Squid Configuration* |

comm_incoming | comm_incoming( ) Stats |

ipcache | IP Cache Stats and Contents |

fqdncache | FQDN Cache Stats and Contents |

idns | Internal DNS Statistics |

dns | Dnsserver Statistics |

redirector | URL Redirector Stats |

basicauthenticator | Basic User Authenticator Stats |

digestauthenticator | Digest User Authenticator Stats |

ntlmauthenticator | NTLM User Authenticator Stats |

external_acl | External ACL Stats |

http_headers | HTTP Header Statistics |

via_headers | Via Request Headers |

forw_headers | X-Forwarded-For Request Headers |

menu | This Cache Manager Menu |

shutdown | Shut Down the Squid Process* |

offline_toggle | Toggle offline_mode Setting* |

info | General Runtime Information |

filedescriptors | Process File Descriptor Allocation |

objects | All Cache Objects |

vm_objects | In-Memory and In-Transit Objects |

openfd_objects | Objects with Swapout Files Open |

io | Server-Side Network read( ) Size Histograms |

counters | Traffic and Resource Counters |

peer_select | Peer Selection Algorithms |

digest_stats | Cache Digest and ICP Blob |

5min | 5 Minute Average of Counters |

60min | 60 Minute Average of Counters |

utilization | Cache Utilization |

histograms | Full Histogram Counts |

active_requests | Client-Side Active Requests |

store_digest | Store Digest |

storedir | Store Directory Stats |

store_check_cachable_stats | storeCheckCachable( ) Stats |

store_io | Store IO Interface Stats |

pconn | Persistent Connection Utilization Histograms |

refresh | Refresh Algorithm Statistics |

delay | Delay Pool Levels |

forward | Request Forwarding Statistics |

client_list | Cache Client List |

netdb | Network Measurement Database |

asndb | AS Number Database |

carp | CARP Information |

server_list | Peer Cache Statistics |

non_peers | List of Unknown Sites Sending ICP Messages |

leaks: Memory Leak Tracking

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-leakfinder option and is intended for

developers trying to track down memory leaks. The page shows each

memory pointer being tracked and where and when it was most recently

referenced. See the Squid Programmer’s Guide (http://www.squid-cache.org/Doc/Prog-Guide/)

for more information about Squid’s leak-finder feature.

mem: Memory Utilization

The memory utilization page shows a large table of numbers. Each row corresponds

to a different pool of memory. The pools have names like acl_list and MemObject. Much of this information is of

interest to developers only. However, a few columns are worth

mentioning here.

Tip

It is important to keep in mind that this table doesn’t represent all the memory allocated by Squid. Some memory allocations aren’t tracked and don’t appear in the table. Thus, the Total row may be much less than Squid’s actual memory usage.

The impact column shows

each pool’s contribution to the total amount of memory allocated.

Usually, the StoreEntry, MD5 digest, and LRU policy node pools take up most of the

memory.

If you are a developer, you can use this page to look for

memory leaks. The column labeled high (hrs) shows the amount of time elapsed

since the pool reached its maximum size. A small value in this

column may indicate that memory for that pool isn’t being freed

correctly.

You can also use this page to find out if certain features,

such as netdb, the

ipcache, and client_db

consume too much memory. For example, the ClientInfo pool is associated with the

client_db feature. The memory utilization page

shows you how much memory you can save if you disable

client_db in squid.conf.

cbdata: Callback Data Registry Contents

The Callback Data Registry is an internal Squid programming feature for managing memory pointers. Currently, this cache manager page doesn’t provide much useful information, apart from the number of active cbdata pointers being tracked. In earlier Squid versions, the cbdata feature was implemented differently and this page provided some information to developers debugging their code.

events: Event Queue

Squid maintains an event queue for a number of tasks that must occur separately from user requests. Perhaps the most important of these is the periodic task that maintains the disk cache size. Every second or so, this task runs and looks for cache files to remove. On this page, you can see all tasks currently scheduled for execution. Most likely, you’ll not find this very interesting unless you are hacking the source code.

squidaio_counts: Async IO Function Counters

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-storeio=aufs option. It shows counters for

the number of open, close, read, write, stat, and unlink requests

received. For example:

ASYNC IO Counters: Operation # Requests open 15318822 close 15318813 cancel 15318813 write 0 read 19237139 stat 0 unlink 2484325 check_callback 311678364 queue 0

The cancel counter is

normally equal to the close

counter. This is because the close function always calls the cancel

function to ensure that any pending I/O operations are

ignored.

The write counter is zero

because this version of Squid performs writes synchronously, even

for aufs.

The check_callback counter

shows how many times the main Squid process has checked the done

queue for completed operations.

The queue value indicates

the current length of the request queue. Normally, the queue length

should be less than the number of threads × 5. If you repeatedly

observe a queue length larger than this, you may be pushing Squid

too hard. Adding more threads may help, but only to a certain

point.

diskd: DISKD Stats

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-storeio=diskd option. It provides various

statistics relating to the diskd storage

scheme.

The sent_count and recv_count lines are counters for the

number of I/O requests sent between Squid and the group of

diskd processes. The two numbers should be very

close to each other and could possibly be equal. The difference

indicates how many requests are currently outstanding.

The max_away value

indicates the largest number of outstanding requests. Similarly, the

max_shmuse counter indicates the

maximum number of shared memory blocks in use at once. These two

values are reset (to zero) each time you request this page. Thus, if

you wait longer between requests for this page, these maximum

counters are likely to be larger.

The open_fail_queue_len

counter indicates the number of times that the

diskd code decided to return failure in

response to a request to open a file because the message queue

exceeded its configured limit. In other words, this is the number of

times a diskd queue reached the Q1 limit.

Similarly, block_queue_len shows

how many times the Q2 limit has been reached. See the descriptions

of Q1 and Q2 in Section

8.5.1.

The diskd page also shows how many

requests Squid sent to the diskd processes for

each of the six I/O operations: open, create, close, unlink, read,

and write. It also shows how many times each operation succeeded or

failed. Note, these counters are incremented only for requests sent.

The open_fail_queue_len check

occurs earlier, and in that case, Squid doesn’t send a request to a

diskd process.

config: Current Squid Configuration*

This option dumps Squid’s current configuration in the squid.conf format. Thus, if you ever

accidentally remove the configuration file, you can recover it from

the running Squid process. By saving the output to a file, you can

also compare (e.g., with the diff

command) the running configuration to the saved configuration. Note,

however, that comments and blank lines aren’t preserved.

This option reveals potentially sensitive information, so it’s available only with a password. You must add a cache manager password for the config option with the cachemgr_passwd directive. See Section 14.2.2 for specifics. Additionally, these cache manager passwords aren’t displayed in this output.

comm_incoming: comm_incoming( ) Stats

This page provides low-level network I/O information to developers and Squid

wizards. The loop that checks for activity on file descriptors is

called comm_poll( ). Over the

years, this function has become increasingly complicated in order to

improve Squid’s performance. One of those performance improvements

relates to how often Squid checks certain network sockets relative

to the others.

For example, the incoming HTTP socket is where Squid accepts new client connections. This socket tends to be busier than a normal data socket because each new connection comes through the incoming socket. To provide good performance, Squid makes an extra effort to check the incoming socket more frequently than the others.

At the top of the comm_incoming page, you’ll see three

incoming interval numbers: one each for ICP, DNS, and HTTP. The

interval is the number of normal I/O events that Squid handles

before checking the incoming socket again. For example, if incoming_dns_interval is set to 140, Squid

checks the incoming DNS socket after 140 I/Os on normal connections.

Unless your Squid is very busy, you’ll probably see 256 for all

incoming intervals.

The page also contains three histograms that show how many

events occur for each incoming function call. Normally, the majority

of the histogram counts occur in the low values. In other words,

functions such as comm_select_http_incoming( ) usually handle between one and

four events.

ipcache: IP Cache Stats and Contents

The IP cache contains cached results of hostname-to-address lookups. This cache manager page displays quite a lot of information. At the top of this page you’ll see a handful of statistics like these:

IPcache Entries: 10034 IPcache Requests: 1066445 IPcache Hits: 817880 IPcache Negative Hits: 6846 IPcache Misses: 200497

In this example, you can see that the IP cache contains slightly more than 10,000 entries (hostnames). Since Squid was started, there have been 1,066,445 name-to-address requests, 817,880 of which were cache hits. This is a cache hit ratio of 77%. An IP cache negative hit occurs when Squid receives a subsequent request for a hostname that it recently failed to resolve. Rather than retry the DNS lookup immediately, Squid assumes it will fail again and returns an error message to the user.

Following these brief statistics, you’ll see a long list of the IP cache contents. For each hostname in the cache, Squid prints six fields:

The hostname itself

Flags:

Nfor negatively cached entries andHif the addresses came from the local hosts file, rather than the DNSThe number of seconds since the hostname was last requested or used

The number of seconds until the cached entry expires

The number of IP addresses known for the host, and, in parentheses, the number of BAD addresses

A list of IP addresses and whether each is OK or BAD

Here is a short sample (formatted to fit the page):

Hostname Flg lstref TTL N

ads.x10.com 9 110 1( 0) 63.211.210.20-OK

us.rd.yahoo.com 640 -340 4( 0) 216.136.232.150-OK

216.136.232.147-OK

216.136.232.149-OK

216.136.232.148-OK

www.movielodge.com 7143 -2161 1( 0) 66.250.223.36-OK

shell.windows.com 10865 -7447 2( 1) 207.46.226.48-BAD

207.46.248.237-OK

www.surf3.net 126810 -40415 1( 0) 212.74.112.95-OKThe list is sorted by the time since last reference. Recently referenced names are at the top of the list, and unused (about to be removed) names are at the bottom.

IP addresses are marked OK by default. An address is marked BAD when Squid receives an error or timeout during a TCP connection attempt. Subsequent IP cache requests don’t return BAD addresses. If all the host’s addresses become BAD, Squid resets them all back to OK.

fqdncache: FQDN Cache Stats and Contents

The FQDN cache is similar to the IP cache, except that it stores address-to-hostname lookups. Another difference is that the FQDN cache doesn’t mark hostnames as OK or BAD.

Your FQDN cache may be empty, unless you enable the log_fqdn directive, use domain-based ACLs (such as srcdomain, dstdomain, srcdom_regex, and dstdom_regex), or use a redirector.

idns: Internal DNS Statistics

Squid contains an internal DNS client implementation, which is enabled by default.

Disabling internal DNS with the

—disable-internal-dns option also disables this

page. Here is some sample output:

Internal DNS Statistics:

The Queue:

DELAY SINCE

ID SIZE SENDS FIRST SEND LAST SEND

------ ---- ----- ---------- ---------

001876 44 1 0.010 0.010

001875 44 1 0.010 0.010

Nameservers:

IP ADDRESS # QUERIES # REPLIES

--------------- --------- ---------

192.168.19.124 4889 4844

192.168.19.190 91 51

192.168.10.2 73 39

Rcode Matrix:

RCODE ATTEMPT1 ATTEMPT2 ATTEMPT3

0 6149 4 2

1 0 0 0

2 38 34 32

3 0 0 0

4 0 0 0

5 0 0 0The Internal DNS page contains three tables. First, you’ll see the queue of unanswered queries. Unfortunately, you can’t see the contents of the query (the hostname or IP address). Instead, Squid prints the ID, size, number of transmissions, and elapsed times for each query. You should see relatively few queries in the queue. If you see a lot relative to your total traffic rate, make sure your DNS servers are functioning properly.

The second table (Nameservers) shows how many queries have

been sent to, and replies received from, each DNS server. Squid

always queries the first server in the list first. Second (and

third, etc.) servers are queried only when the previous server times

out for a given query. If you see zero replies from the first

address, make sure a server is actually running at that

address.

Finally, you’ll see a table of DNS response codes versus

number of attempts. The cell for response code 0 and ATTEMPT1 should have the highest count.

Response code 0 indicates

success, while others are different types of errors (see RFC 1035

for their descriptions). You may see some smaller numbers for

response code 0 in the columns

for ATTEMPT2 and ATTEMPT3. This shows the cases when

retransmitting a query, after initially receiving an error, resulted

in a successful reply. Note that Squid retries only response code 2

(server failure) errors.

dns: Dnsserver Statistics

This cache manager page is available only when you use the

—disable-internal-dns option. In this case, Squid

uses a number of external dnsserver processes to perform DNS

lookups. The dnsserver program is

one of a number of helper processes Squid can use. The other types

of helpers are redirectors, authenticators, and external ACLs. All

Squid’s helpers have cache manager pages that display the same

statistics. For example:

Dnsserver Statistics:

number running: 5 of 5

requests sent: 3001

replies received: 3001

queue length: 0

avg service time: 23.10 msec

# FD PID # Requests Flags Time Offset Request

1 6 20110 128 AB 0.293 0 www.nlanr.net

2 7 20111 45 A 0.000 0 (none)

3 8 20112 4 A 0.000 0 (none)

4 9 20113 0 A 0.000 0 (none)

5 10 20114 0 A 0.000 0 (none)The number running line shows how many helper

processes are running and how many should be running. The

dns_children directive specifies how many

dnsserver processes to use. The

two numbers should match, but they may not if a helper process dies

unexpectedly or if some processes could not be started. Recall that

when you reconfigure a running Squid instance, all the helpers are

killed and restarted. See the discussion in Appendix A.

The requests sent and

replies received values display

the number of requests sent to (and responses received from) the

helpers since Squid started. The difference between these two, if

any, should correspond to the number of outstanding requests.

The queue length line shows

how many requests are queued, waiting for one of the helpers to

become free. The queue length should usually be zero. If not, you

should add more helpers to reduce delays for your users.

The avg service time line

shows the running average service time for all helpers. Your

particular value may depend on numerous factors, such as your

network bandwidth and processing power.

The next section displays a table of statistics for the

running dnsserver processes. The

FD column shows the file

descriptor for the socket between Squid and each dnsserver process. Similarly, the PID column shows each helper’s process ID

number.

The # Requests column shows

how many requests have been sent to each helper. These numbers are

zeroed each time you reconfigure Squid, so they many not add up to

the total number of requests sent, as shown earlier. Note that Squid

always chooses the first idle helper in the list, so the first

process should receive the largest number of requests. The last few

processes may not receive any requests at all.

The Flags column shows a

few flags describing the state of the helper process. You should

normally see A (for Alive) in

each column. Occasionally, when the helper process is handling a

request, you’ll see B (for

Busy).

The Time column displays

the amount of time elapsed (in seconds) for the current, or last,

request. Offset shows how many

bytes of the response message Squid has read on the socket. This is

almost always zero. Finally, the Request column shows the request that was

sent to the helper process. In this case, it is either a hostname or

an IP address.

redirector: URL Redirector Stats

The Redirector Stats page is available only if you are using a redirector (see Chapter 11). The format of this page is identical to Dnsserver Statistics, described earlier.

basicauthenticator: Basic User Authenticator Stats

This page is available only w ith the ./configure

—enable-auth=basic option and when you define a

Basic authenticator with the auth_param basic

program directive. The format of this page is identical

to Dnsserver Statistics, described

earlier.

digestauthenticator: Digest User Authenticator Stats

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-auth=digest option and when you define a

Digest authenticator with the auth_param digest

program directive. The format of this page is identical

to Dnsserver Statistics, described

earlier.

ntlmauthenticator: NTLM User Authenticator Stats

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-auth=ntlm option and when you define a NTLM

authenticator with then auth_param ntlm program

directive. The format of this page is similar to Dnsserver

Statistics, described earlier, with a few

additions.

The table of helper processes includes an extra column:

# Deferred Requests. NTLM

requires “stateful” helpers because the helper processes themselves

generate the challenges. Squid receives a challenge from a helper,

sends that challenge to a user, and receives a response. Squid must

send the user’s challenge response back to the same helper for

validation. For this protocol to work, Squid must defer some

messages to be sent to a helper until the helper is ready to accept

them.

These helpers also have two new flags: R (reserved or deferred) and P (placeholder). The R flag is set when the helper has at least

one deferred request waiting. The P flag is set when Squid is waiting for

the NTLM helper to generate a new challenge token.

external_acl: External ACL Stats

This page displays helper statistics for your external ACLs. If you don’t have any external_acl_type lines in squid.conf, this page will be empty. Otherwise, Squid displays the statistics for each external ACL. The format is the same as for the Dnsserver Statistics.

http_headers: HTTP Header Statistics

This page displays a number of tables containing statistics about HTTP headers. It contains up to four sections: HTCP reply stats (if HTCP is enabled), HTTP request stats, HTTP reply stats, and a final section called HTTP Fields Stats. The HTCP reply statistics refer to HTCP replies received by your cache. The HTTP request section refers to HTTP requests either sent or received by your cache. Similarly, the HTTP reply section refers to replies either sent or received by Squid.

The first three sections have the same format. Each section contains three tables: Field type distribution, Cache-control directives distribution, and Number of fields per header distribution.

The Field type distribution table shows the number of times

that each header value occurs and the percentage of cases in which

it occurs. For example, in Table 14-2 you can see that

the Accept header occurs in 98%

of HTTP requests.

ID | Name | Count | #/header |

0 | | 1416268 | 0.98 |

1 | | 322077 | 0.22 |

2 | | 709715 | 0.49 |

3 | | 1334736 | 0.92 |

... | ... | ... | ... |

Unfortunately, these (and the following) statistics are tricky

because they don’t correspond one-to-one for client requests. For

example, Squid may report 1,416,268 Accept headers in requests but only

800,542 client requests. This happens because Squid creates more

than one HTTP header data structure for each request. In the case of

HTTP replies, it seems that Squid may create up to four separate

header structures, depending on the circumstances.

The Cache-Control

directives distribution is similar, but applies only to the values

of the Cache-Control header.

Table 14-3 shows some of

the possible field values.

ID | Name | Count | #/cc_field |

0 | | 6866 | 0.02 |

1 | | 69783 | 0.24 |

2 | | 78252 | 0.27 |

3 | | 9878 | 0.03 |

4 | | 168 | 0.00 |

5 | | 10983 | 0.04 |

6 | | 2480 | 0.01 |

7 | | 165034 | 0.56 |

8 | | 4995 | 0.02 |

9 | | 0 | 0.00 |

10 | | 0 | 0.00 |

11 | | 9149 | 0.03 |

The Number of fields per header distribution table shows how many headers

occur in each request or reply. Usually, you should see something

like a normal distribution with a peak around 10-13 headers per

request or response.

Finally, this page ends with a table labeled Http Fields Stats (replies and requests). For each header, this table

shows three values: #alive,

%err, and %repeat.

The #alive column shows how

many instances of this header are currently stored in memory. HTTP

headers are kept in memory for both active requests/responses and

for completed objects stored in the memory cache.

The %err column shows the

percentage of times Squid encountered an error while parsing this

header. Common errors include incorrect date formats for Date, Expires, Last-Modified, and similar headers. The

value -1 indicates no

errors.

The %repeat column

indicates the number of times that a particular header is repeated

in a single request or response. These aren’t errors because HTTP

allows headers to be repeated.

via_headers: Via Request Headers

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-forw-via-db option. The information in this

page is intended to help cache administrators understand where

client requests come from. When enabled, Squid counts the number of

times each unique Via header

occurs in client requests.

The Via header contains a

list of downstream proxies that have forwarded the request so far.

When a proxy forwards a request, it should append its hostname and

other identifying information to the Via header. With the information in this

database, you can, in theory, reconstruct the hierarchy of proxies

forwarding requests through yours.

Squid prints the Via

database entries in a random order. The output may look something

like this:

4 1.0 proxy.firekitten.org:3128 (squid/2.5.STABLE1)

1 1.0 xnsproxy.dyndns.org:3128 (squid/2.5.PRE3-20020125)

1751 1.0 nt04.rmtcc.cc.oh.us:3128 (Squid/2.4.STABLE6),

1.0 tasksmart.rmtcc.cc.oh.us:3128 (Squid/2.4.STABLE7)

137 1.0 reg3.bdg.telco.co.id:8080 (Squid/2.2.STABLE5),

1.0 c1.telco.co.id:8080 (Squid/2.4.STABLE6),

1.0 cache2.telco.co.id:8080 (Squid/2.4.STABLE1)

53 1.0 IS_GW_312:3128 (Squid/2.4.STABLE6)

60 1.0 proxy.kiltron.net:3128 (Squid/2.4.STABLE7)

815 1.1 DORMIn this example, Squid received 1751 requests that previously

passed through two other proxies (nt04 and

tasksmart). Note that only proxies add a

Via header. Requests from

user-agents usually don’t have the header and, therefore, aren’t

counted in this database.

As you can see, the Via

headers reveal some semiprivate information, such as hostnames, port

numbers, and software versions. Please take care to respect the

privacy of your users if you enable this feature.

The Via database is stored

entirely in memory and is lost if Squid restarts. The database is

cleared whenever you rotate the log files (see Section 13.7).

forw_headers: X-Forwarded-For Request Headers

This page is available only with the ./configure

—enable-forw-via-db option. It is similar to the

via_headers page, except that it displays the

accumulation of X-Forwarded-For

headers.

X-Forwarded-For is a

nonstandard HTTP header that originated with the Squid project. Its

value is a list of client IP addresses. In other words, when Squid

receives and forwards a request, it appends the client’s IP address

to this header. It is similar to Via because the header grows each time a

proxy passes the request on towards the origin server.

The forw_headers output is similar to

via_headers. Each line begins with an integer,

followed by a header value. The integer indicates how many times

that particular X-Forwarded-For

value was received. For example:

1 10.37.1.56, 10.1.83.8 3 10.3.33.77, 10.1.83.8 569 116.120.203.54 21 10.65.18.200, 10.1.83.120 31 116.120.204.6 5 10.1.92.7, 10.1.83.120 1 10.3.65.122, 10.3.1.201, 10.1.83.8 2 10.73.73.51, 10.1.83.120 1 10.1.68.141, 10.1.83.8 3 10.1.92.7, 10.1.83.122

As with via_headers, this database is also stored in memory and is lost if Squid exits. The database is cleared each time you rotate Squid’s log files.

menu: This Cache Manager Menu

This page simply displays a listing of the other cache manager pages. You can use it if you forget the name of a page or if you want to know if certain optional pages are available. When using cachemgr.cgi, each item in the menu is a clickable link.

shutdown: Shut Down the Squid Process*

This is one of the few cache manager functions that doesn’t simply display some information. Rather, this “page” allows you to shut down Squid remotely. To allow shutdown via the cache manager, you must assign it a password with the cachemgr_passwd (see Section 14.2.2) directive in squid.conf. Without a password, the shutdown operation is disabled (but you can still use squid -k shutdown).

Because the cache manager has very weak security—passwords are sent in cleartext—I don’t recommend enabling this operation.

offline_toggle: Toggle offline_mode Setting*

This is another function that allows you to control Squid, rather than simply receive information. It also requires a password (see Section 14.2.2) in order to become active.

Each time you request this page, Squid toggles the offline_mode setting. Squid reports the new setting on your screen and in cache.log.

info: General Runtime Information

This page provides a lot of basic information about the way that Squid is operating. It is a good starting point for using the cache manager and for tracking down performance problems.

At the top, you’ll see the release version (e.g., Version 2.5.STABLE4) and two timestamps: the starting and current times. For example:

Squid Object Cache: Version 2.5.STABLE4 Start Time: Mon, 22 Sep 2003 03:10:37 GMT Current Time: Mon, 13 Oct 2003 10:25:16 GMT

Following that, you’ll see seven different sections. The first

section, Connection information, displays a few statistics

about the number and rate of connections, and the number of cache

clients:

Connection information for squid:

Number of clients accessing cache: 386

Number of HTTP requests received: 12997469

Number of ICP messages received: 16302149

Number of ICP messages sent: 16310714

Number of queued ICP replies: 0

Request failure ratio: 0.00

Average HTTP requests per minute since start: 423.7

Average ICP messages per minute since start: 1063.2

Select loop called: 400027445 times, 4.601 ms avgNumber of clients accessing cacheHere, “client” actually means IP address. Squid assumes that each client has a unique IP address.

Number of HTTP requests receivedThe total number of HTTP requests since Squid was started.

Number of ICP messages receivedThe total number of ICP messages received since Squid was started. Note, received messages includes both queries and responses. These values don’t include HTCP messages, however.

Number of ICP messages sentThe total number of ICP messages sent since Squid was started. Note, received messages includes both queries and responses. Doesn’t include HTCP messages. Most likely, your sent and received counts will be about the same.

Number of queued ICP repliesICP messages are sent over UDP. The

sendto( )system call rarely fails, but if it does, Squid queues the ICP message for retransmission. This counter shows how many times an ICP message was queued for retransmission. Most likely, you’ll see0here.Request failure ratioThe failure ratio is a moving average ratio between the number of failed and successful requests. In this context, a failed request is caused by either a DNS error, TCP connection error, or network read error. When this ratio exceeds 1.0—meaning Squid returns more errors than successful responses— Squid goes into hit-only mode. In this mode, Squid returns

ICP_MISS_NOFETCHinstead ofICP_MISS. Thus, your neighbor caches that use ICP won’t forward cache misses to you until the problem goes away.Average HTTP requests per minute since startThis value is simply the number of HTTP requests divided by the amount of time Squid has been running. This average doesn’t reflect short-term variations in load. To get a better instantaneous load measurement, use the 5min or 60min page.

Average ICP messages per minute since startThe number of ICP queries received by Squid divided by the amount of time that it has been running.

Select loop calledThis number is probably meaningful only to Squid developers. It represents the number of times the

select( )(orpoll( )) function has been called and the average time between calls. During normal operation, the time between calls should be in the 1-100 millisecond range.

The Cache information section displays hit ratio and

cache size statistics:

Cache information for squid:

Request Hit Ratios: 5min: 22.6%, 60min: 25.8%

Byte Hit Ratios: 5min: 24.6%, 60min: 38.7%

Request Memory Hit Ratios: 5min: 0.7%, 60min: 1.4%

Request Disk Hit Ratios: 5min: 6.0%, 60min: 12.4%

Storage Swap size: 41457489 KB

Storage Mem size: 10180 KB

Mean Object Size: 14.43 KB

Requests given to unlinkd: 0Request Hit RatiosHere, and on subsequent lines, you’ll see two hit ratio numbers: one for the last five minutes, and one for the last hour. These values are simply the percentage of HTTP requests that result in a cache hit. Here, hits include cases in which Squid validates a cached response and receives a 304 (Not Modified) reply.

Byte Hit RatiosSquid calculates byte hit ratio by comparing the number of bytes received from origin servers (or neighbors) to the number of bytes sent to clients. When received bytes are less than sent bytes, the byte hit ratio is positive. However, it is possible to see a negative byte hit ratio. This might occur, for example, if you have a lot of clients that abort their request before receiving the entire response.

Request Memory Hit RatiosThese values represent the percentage of all cache hits that were served from memory. Or, more accurately, the percentage of all hits (not requests!) logged as

TCP_MEM_HIT.Request Disk Hit RatiosSimilarly, these values represent the percentage of “plain” cache hits served from disk. In particular, these values are the percentage of all hits logged as

TCP_HIT. You’ll see that the memory and disk hit percentages don’t add up to 100%. This is because the other cases (such asTCP_IMS_HIT, etc.) aren’t included in either disk or memory hits.Storage Swap sizeThe amount of data currently cached on disk. It is always expressed in kilobytes. To compensate for space wasted in partial blocks at the end of files, Squid rounds up file sizes to the nearest filesystem block size.

Storage Mem sizeThe amount of data currently cached in memory. It is always expressed in kilobytes and is always a multiple of Squid’s memory page size: 4 KB.

Mean Object SizeSimply the storage swap size divided by the number of cached objects. You should set the configuration directive store_avg_object_size close to the actual value reported here. Squid uses the configured value for a number of internal estimates.

Requests given to unlinkdThe unlinkd process handles file deletion external to Squid (depending on your configuration). This value simply shows how many files Squid has asked unlinkd to remove. It is zero when unlinkd isn’t used.

The Median Service Times section displays the median of

various service time (or response time) distributions. You’ll see a

value for the last five minutes and for the last hour. All values

are in seconds. Squid uses the median, rather than the mean, because

these distributions often have heavy tails that can significantly

skew the mean value. The output looks like this:

Median Service Times (seconds) 5 min 60 min:

HTTP Requests (All): 0.19742 0.15048

Cache Misses: 0.22004 0.17711

Cache Hits: 0.05951 0.04047

Near Hits: 0.37825 0.14252

Not-Modified Replies: 0.01309 0.01387

DNS Lookups: 0.05078 0.03223

ICP Queries: 0.00000 0.07487HTTP Requests (All)These are the median response times for all HTTP requests taken together. For an HTTP request, the timer starts as soon as Squid receives the request and ends when Squid writes the last byte of the response. Thus, this time also includes DNS lookups (if any), and ICP queries to upstream neighbors (if you have them) for cache misses.

Cache MissesThis line shows the response time for cache misses only. Unless your cache hit ratio is close to 50%, the cache miss response time is close to (but a little larger than) the overall response time.

Cache HitsThe cache hit response time includes only requests logged as

TCP_HIT,TCP_MEM_HIT, andTCP_OFFLINE_HIT. These are unvalidated cache hits served directly from Squid, without any communication to the origin server. Thus, your cache hit response time should be significantly less than the miss time. You should keep track of this value over time; if it climbs too high, your disk filesystem may be a performance bottleneck.Near HitsA near hit is a validated cache hit. It corresponds to

TCP_REFRESH_HITin access.log. For these, Squid contacts the origin server (or parent cache), which adds some latency to the response time. The server’s response is a small 304 (Not Modified) message. Thus, the near hit response time is typically in between cache hits and cache misses.Not-Modified RepliesThis line shows the response times for requests logged as

TCP_IMS_HIT. This occurs when the client sends a conditional (a.k.a. validation) request, and Squid serves a response without contacting the origin server. The name “not-modified” is somewhat misleading for this category because the status code received by the client isn’t necessarily 304. For example, the client may send an If-modified-since request, and Squid has a fresh, cached response with a more recent modification time. Squid knows that its response is fresh and that the client’s copy is stale. In this case, the client receives a 200 (OK) reply with the new object data.DNS LookupsThe DNS service time shows how long it takes, on average, to query the DNS. This includes both name-to-address and address-to-name lookups. It doesn’t include IP- and FQDN-cache hits, however. DNS queries can be a significant source of latency. If you experience performance problems with Squid, be sure to check this value. If you see a high median service time (i.e., around five seconds), make sure your primary DNS server (usually listed in /etc/resolv.conf) is up and running.

ICP QueriesThe ICP query time represents the elapsed time between an ICP query and response that causes Squid to select the corresponding neighbor as the next hop. Thus, it includes only requests logged as

PARENT_HIT,SIBLING_HIT,FIRST_PARENT_MISS, andCLOSEST_PARENT_MISS. This value may not be a good estimate of the overall ICP response time because ICP query/response transactions that don’t result in Squid selecting a neighbor are ignored. Due to a bug in Squid Versions 2.5.STABLE1 and earlier, ICP response time statistics aren’t collected, and these values always appear as0.

The Resource usage section includes a few statistics

relating to CPU and memory usage:

Resource usage for squid:

UP Time: 1840478.681 seconds

CPU Time: 70571.874 seconds

CPU Usage: 3.83%

CPU Usage, 5 minute avg: 1.33%

CPU Usage, 60 minute avg: 4.41%

Process Data Segment Size via sbrk( ): 342739 KB

Maximum Resident Size: 345612 KB

Page faults with physical i/o: 65375UP TimeThis line simply shows the amount of time this Squid process has been running. It is expressed in seconds.

CPU TimeThe amount of CPU time used by Squid, also in seconds. This value comes from the

getrusage( )system call, which might not be available on all operating systems.CPU UsageThis section has three CPU Usage lines. The first is the CPU Time value divided by the UP Time value. It is a long-term average CPU usage measurement. The next two lines show the CPU usage for the last five minutes and the last hour.

Process Data Segment Size via sbrk( )This line offers an estimate of Squid’s process size.

sbrk( )is a low-level system call used by the memory allocation library (malloc( )). Thesbrk( )technique provides only an estimate, which usually differs from values reported by programs such as ps and top. When thesbrk( )value is greater than theMaximum Resident Size(discussed next), the Squid process is probably page faulting, and performance may be degrading.Maximum Resident SizeThis is another estimate of memory usage and process size. The maximum resident set size (RSS) value comes from the

getrusage( )system call. Although the definition of RSS may vary between operating systems, you can think of it as the maximum amount of physical memory used by the process at any one time. Squid’s process size may be larger than the RSS, in which case some parts of the process are actually swapped to disk.Page faults with physical i/oThis value also comes from

getrusage( ). A page fault occurs when the operating system must read a page of the process’s memory from disk. This usually happens when the Squid process becomes too large to fit entirely in memory, or when the system has other programs competing for memory. Squid’s performance suffers significantly when page faults occur. You probably won’t notice any problems as long as the page-faults rate is an order of magnitude lower than the HTTP request rate.

You’ll see a section called Memory

usage for squid via mstats( ) if your system has the

mstats( ) function. In particular,

you’ll have this function if the GNU malloc library (libgnumalloc.a) is installed. Squid

reports two statistics from mstats( ):

Memory usage for squid via mstats( ):

Total space in arena: 415116 KB

Total free: 129649 KB 31%Total space in arenaThis represents the total amount of memory allocated to the process. It may be similar to the value reported by

sbrk( ). Note that this value only increases over time.Total freeThis represents the amount of memory allocated to the process but not currently in use by Squid. For example, if Squid frees up some memory, it goes into this category. Squid can later reuse that memory, perhaps for a different data structure, without increasing the process size. This value fluctuates up and down over time.

The Memory accounted for section contains a few tidbits about

Squid’s internal memory management techniques:

Memory accounted for:

Total accounted: 228155 KB

memPoolAlloc calls: 2282058666

memPoolFree calls: 2273301305Total accountedSquid keeps track of some, but not nearly all, of the memory allocated to it. This value represents the total size of all data structures accounted for. Unfortunately, it is typically only about two-thirds of the actual memory usage. Squid uses a significant amount of memory in ways that make it difficult to track properly.

memPoolAlloc callsmemPoolAlloc( )is the function through which Squid allocates many fixed-size data structures. This line shows how many times that function has been called.memPoolFree callsmemPoolFree( )is the companion function through which Squid frees memory allocated withmemPoolAlloc( ). In a steady-state condition, the two values should increase at the same rate and their difference should be roughly constant over time. If not, the code may contain a bug that frees pooled memory back to themalloclibrary.

The File descriptor usage section shows how many file

descriptors are available to Squid and how many are in use:

File descriptor usage for squid:

Maximum number of file descriptors: 7372

Largest file desc currently in use: 151

Number of file desc currently in use: 105

Files queued for open: 0

Available number of file descriptors: 7267

Reserved number of file descriptors: 100

Store Disk files open: 0Maximum number of file descriptorsThis is the limit on open file descriptors for the squid process. This should be the same value reported by ./configure when you compiled Squid. If you don’t see at least 1024 here, you should probably go back and recompile Squid after reading Section 3.3.1.

Largest file desc currently in useThis is the highest file descriptor currently open. Its value isn’t particularly important but should be within 15-20% of the next line (number currently in use). This value is more useful for developers because it corresponds to the first argument of the

select( )system call.Number of file desc currently in useThe number of currently open descriptors is an important performance metric. In general, Squid’s performance decreases as the number of open descriptors increases. The kernel must work harder to scan the larger set of descriptors for activity. Meanwhile, each file descriptor waits longer (on average) to be serviced.

Files queued for openThis value will always be zero, unless you are using the aufs storage scheme (see Section 8.4). It shows how many file-open requests have been dispatched to the thread processes but have not yet returned. aufs is the only storage scheme in which disk file descriptors are opened asynchronously.[2]

Available number of file descriptorsThe number of available descriptors is the maximum, minus the number currently open and the number queued for open. It represents the amount of breathing room Squid has to handle more load. When the available number gets close to the reserved number (next line), Squid stops accepting new connections so that existing transactions continue receiving service.

Reserved number of file descriptorsThe number of reserved file descriptors starts out at the lesser of 100 or 25% of the maximum. Squid refuses new client connections if the number of available (free) descriptors reaches this limit. It is increased if Squid encounters an error while trying to create a new TCP socket. In this case, you’ll see a message in cache.log:

Reserved FD adjusted from 100 to 150 due to failures

Store Disk files openThis counter shows the number of disk files currently open for reading or writing. It is always zero if you are using the diskd storage scheme because disk files are opened by the diskd processes, rather than Squid itself. If you use the max_open_disk_fds directive in squid.conf, Squid stops opening more cache files for reading or writing when it reaches that limit. If your filesystem is a bottleneck, this is a simple way to sacrifice a few cache hits for stable performance.

The Internal Data

Structures section gives a quick overview of how many

objects are in the cache and how many are on disk or in memory. You

can find more detail about Squid’s data structure allocations in the

mem page (see Section 14.2.1.2). This

section has a few stats:

Internal Data Structures:

2873586 StoreEntries

1336 StoreEntries with MemObjects

1302 Hot Object Cache Items

2873375 on-disk objectsStoreEntriesThis represents the number of objects cached by Squid. Each object in the cache uses one

StoreEntrystructure.StoreEntries with MemObjectsMemObjectis the data structure used for objects currently being requested and for objects stored in the memory cache.Hot Object Cache ItemsThe

HotObjectCacheis another name for the memory cache (see Appendix B). These objects are stored entirely in memory (as well as on disk). This number should always be less than the number of entries withMemObjects.on-disk objectsThis counter shows how many objects are currently stored on disk. The counter is incremented when the entire object has been successfully written. Thus, this number isn’t necessarily equal to the number of

StoreEntriesminus the number ofHotObjects.

filedescriptors: Process File Descriptor Allocation

This page displays a table of all file descriptors currently opened by Squid. It looks like this:

File Type Tout Nread * Nwrite * Remote Address Description ---- ------ ---- -------- -------- ----------------- ------------------------------ 3 File 0 0 0 /usr/local/squid/logs/cache.log 6 File 0 0 2083739 /usr/local/squid/logs/access.log 12 Pipe 0 0 0 unlinkd -> squid 13 File 0 0 2485913 /usr/local/squid/logs/store.log 15 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> unlinkd 16 Socket 24 220853* 1924 65.200.216.110.80 http://downloads.mp3.com/ 18 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> diskd 19 Socket 179 476* 1747 202.59.16.30.4171 http://ads.vesperexchange.com/ 21 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> diskd 22 Socket 20 158783* 998 210.222.20.8.80 http://home.hanmir.com/a 24 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> diskd 25 Socket 1 0 0* 210.222.20.8.80 http://home.hanmir.com/b 26 Socket 0 9048307* 1578290 .0 DNS Socket 27 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> diskd 28 Socket 0 0 0* 66.28.234.77.80 http://updates.hotbar.com/ 29 Socket 0 0* 0 .0 HTTP Socket 30 Pipe 0 0 0 squid -> diskd 31 Socket 0 93 1126 127.0.0.1.3434 ncsa_auth #1 32 Socket 0 3 31 127.0.0.1.3438 ncsa_auth #3 33 Socket 0 0 0 127.0.0.1.3440 ncsa_auth #4 34 Socket 164 8835* 1070222* 212.47.19.52.2201 http://www.eyyubyaqubov.com/ 35 Socket 177 6137* 249899* 212.47.19.25.3044 http://files10.rarlab.com/ 36 Socket 0 0 0 127.0.0.1.3442 ncsa_auth #5 37 Socket 7 158783* 774 210.222.20.8.80 http://home.hanmir.com/c 38 Socket 166 1000* 148415* 202.17.13.8.5787 http://home.hanmir.com/d

The table has seven columns:

FileThis is simply the file descriptor number. The list always starts with 3 because descriptors 0, 1, and 2 are reserved for stdin, stdout, and stderr. Any other gaps in the list represent closed descriptors.

TypeThe type field contains one of the following values: File, Pipe, or Socket. The File type is used both for files storing cached responses and for log files, such as cache.log and access.log. The Pipe type represents kernel pipes used for interprocess communication. The Socket type is also occasionally used for interprocess communication, but it’s mostly used for HTTP (and FTP) connections to clients and servers.

ToutThis is the general-purpose timeout value for the descriptor. It is expressed in minutes. Files and Pipes usually don’t have a timeout, so this value is zero. For Sockets, however, if this number of minutes go by without any activity on the descriptor, Squid calls a timeout function.

NreadThis is where Squid reports the number of bytes read from the descriptor. An asterisk (*) after the number means Squid has a function (a read handler) registered to read additional data, if there is some available.

NwriteThis column shows the number of bytes written to the descriptor. Again, the asterisk (*) indicates that a write handler is present for the descriptor. You can usually tell if a given socket is connected to a client or to a server by comparing the number of bytes read and written. Because requests are normally smaller than responses, a server connection has a higher

Nreadcount thanNwrite. The opposite is true for client connections.Remote AddressFor Sockets, this field shows the remote TCP address of the connection. The format is similar to what you would find in netstat -n output: an IP address followed by the TCP port number.

DescriptionThe description field indicates the descriptor’s use. For Files, you’ll see a pathname; for Pipes, a description to what the pipe is connected; and for Sockets, a URI, or at least the first part of it. A description such as

web.icq.comidleconnectionindicates an idle persistent connection to an origin server. Similarly,Waitingfornextrequestis an idle client-side persistent connection.

By default, the File Descriptor page isn’t password-protected. However, you may want to give it a password because it contains some sensitive and, perhaps, personally identifiable information.

objects: All Cache Objects

Requesting this page results in a list of all objects in the cache. Be careful with this page because it can be extremely long. Furthermore, it contains low-level information that is probably useful only to developers.

For each cached object, Squid prints a sequence of lines, most of which look like this:

KEY FF1F6736BCC167A4C3F93275A126C5F5

STORE_OK NOT_IN_MEMORY SWAPOUT_DONE PING_NONE

CACHABLE,DISPATCHED,VALIDATED

LV:1020824321 LU:1020824671 LM:1020821288 EX:-1

0 locks, 0 clients, 1 refs

Swap Dir 0, File 0X010AEEThe first line shows the cache key—a 128-bit MD5 checksum of the URI. The same MD5 checksum appears in store.log and in the metadata at the beginning of each response cached on disk.

The second line shows four state variables of the StoreEntry data structure:

store_status, mem_status,

swap_status, and

ping_status. Refer to the Squid source code if

you’d like more information about them.

The third line is a list of the StoreEntry flags that are set. Search the

source code for e->flags for more

information.

The fourth line shows the values of four timestamps: last-validation, last-use, last-modification, and expiration. The last-modification and expiration timestamps are taken from the origin server’s HTTP response. The others are maintained by Squid.

The fifth line shows a few counters: locks, clients, and

references. An entry with locks can’t be removed. The clients counter shows how many clients are

currently receiving data for this object. The refs counter shows how many times the

object has been requested.

The sixth line shows the object’s index to the on-disk storage. Each object has a 7-bit swap directory index and a 25-bit file number. Each storage scheme has a function to map these numbers into pathnames.

vm_objects: In-Memory and In-Transit Objects

This page is similar to All Cache Objects, except that it displays only objects that have a

MemObject data structure. In

other words, objects that are currently being requested or are

stored in the memory cache. These objects are displayed like

this:

KEY 5107D49BA7F9C6BA9559E006D6DDC4B2

GET http://www.rpgplanet.com/ac2hq/cartography/dynamic/LinvakMassif.jpg

STORE_PENDING NOT_IN_MEMORY SWAPOUT_WRITING PING_DONE

CACHABLE,DISPATCHED,VALIDATED

LV:1043286120 LU:1043286122 LM:1036015230 EX:-1

4 locks, 1 clients, 1 refs

Swap Dir 1, File 00X31BD9

inmem_lo: 184784

inmem_hi: 229840

swapout: 229376 bytes queued

swapout: 229509 bytes written

Client #0, 1533a1018

copy_offset: 217552

seen_offset: 217552

copy_size: 4096

flags:As you can see, many of the lines are the same. However, the in-memory objects have a few additional lines. Directly following the cache key (MD5 checksum), Squid prints the request method and URI.

The inmem_lo and inmem_hi lines are byte offsets of the

HTTP reply. They indicate the section of object data currently in

memory. In most cases, the difference between these two should be

less than the value of the

maximum_object_size_in_memory directive.

The swapout: bytes queued line shows the offset for how many

bytes have been given to the storage layer for writing. For objects

in the SWAPOUT_DONE state, this

value is the same as the object size. If the state is SWAPOUT_WRITING, Squid also shows the

bytes written line, which

indicates how many bytes have been successfully stored on

disk.

If one or more clients are currently receiving the response,

you’ll see a section for each of them (Client #0 in this example). For each

client, Squid reports another pair of offset values. The first,

copy_offset, is the starting

point for the last time the client-side asked for data from the

storage system. The second, seen_offset, is the point at which the

response data has been sent to the client. Note that copy_offset is always greater than or

equal to seen_offset. The

copy_size indicates the maximum

amount of data the client can receive from the storage

system.

openfd_objects: Objects with Swapout Files Open

The format of this page is the same as for In-Memory and In-Transit Objects. The

objects reported on this page should all be in the SWAPOUT_WRITING state. The page is

primarily useful to developers when trying to track down

file-descriptor leaks.

io: Server-Side Network read( ) Size Histograms

This page displays a histogram for each of the following four server-side protocols:

HTTP, FTP, Gopher, and WAIS. The histograms show how many bytes each

read( ) call received. The information

is primarily useful to developers for tuning buffer sizes and other

aspects of the source code.

The bins of the histogram are logarithmic to accommodate the large scale of read sizes. Here is an example:

HTTP I/O

number of reads: 9016088

Read Histogram:

1- 1: 3082 0%

2- 2: 583 0%

3- 4: 905 0%

5- 8: 2666 0%

9- 16: 16690 0%

17- 32: 88046 1%

33- 64: 19712 0%

65- 128: 116655 1%

129- 256: 749259 8%

257- 512: 633075 7%

513- 1024: 903145 10%

1025- 2048: 3664862 41%

2049- 4096: 1643747 18%

4097- 8192: 789796 9%

8193-16384: 99476 1%

16385-32768: 30059 0%In this case, you can see that the bin for 1025-2048 bytes is the most popular. When reading from an HTTP server, Squid got between 1025 and 2048 bytes per read 41% of the time.

counters: Traffic and Resource Counters

Squid maintains a data structure of counters. Actually, it is an array of counters. Squid shifts the array every 60 seconds and calculates 1-, 5-, and 60-minute averages from this array. This page is simply a dump of the current counter values in a format more suitable for computer processing than for reading by humans. The counters are as follows:

sample_timeThe sample time is actually the time of the last shift, rather than the current time. The sample time is always within 60 seconds of the current time.

client_http.requestsThe number of HTTP requests received from clients.

client_http.hitsThe number of cache hits in response to client requests. A hit is any transaction logged with one of the

TCP_HITcodes in access.log.client_http.errorsThe number of client transactions that resulted in an error.

client_http.kbytes_inThe amount of traffic (in kilobytes) received from clients in their requests. This is measured at the HTTP layer and doesn’t include TCP, IP, and other packet headers.

client_http.kbytes_outThe amount of traffic (in kilobytes) sent to clients in responses. Also measured at the HTTP layer.

client_http.hit_kbytes_outThe amount of traffic sent to clients in responses that are cache hits. Keep in mind that some cache hits are 304 (Not Modified) responses.

server.all.requestsThe number of requests forwarded to origin servers (or neighbor caches) for all server-side protocols (HTTP, FTP, Gopher, etc.).

server.all.errorsThe number of server-side requests (all protocols) that resulted in some kind of error.

server.all.kbytes_inThe amount of traffic (in kilobytes) read from the server-side for all protocols.

server.all.kbytes_outThe amount of traffic written to origin servers and/or neighbor caches for server-side requests.

server.http.requestsThe number of server-side requests to HTTP servers, including neighbor caches.

server.http.errorsThe number of server-side HTTP requests that resulted in an error.

server.http.kbytes_inThe amount of traffic read from HTTP origin servers and neighbor caches.

server.http.kbytes_outThe amount of traffic written to HTTP origin servers and neighbor caches.

server.ftp.requestsThe number of requests sent to FTP servers.

server.ftp.errorsThe number of requests sent to FTP servers that resulted in an error.

server.ftp.kbytes_inThe amount of traffic read from FTP servers, including control channel traffic.

server.ftp.kbytes_outThe amount of traffic written to FTP servers, including control channel traffic.

server.other.requestsThe number of “other” server-side requests. Currently, the other protocols are Gopher, WAIS, and SSL.

server.other.errorsThe number of Gopher, WAIS, and SSL requests that resulted in an error.

server.other.kbytes_inThe amount of traffic read from Gopher, WAIS, and SSL servers.

server.other.kbytes_outThe amount of traffic written to Gopher, WAIS, and SSL servers.

icp.pkts_sentThe number of ICP messages sent to neighbors. This includes both queries and replies but doesn’t include HTCP messages.

icp.pkts_recvThe number of ICP messages received from neighbors, including both queries and replies.

icp.queries_sentThe number of ICP queries sent to neighbors.

icp.replies_sentThe number of ICP replies sent to neighbors.

icp.queries_recvThe number of ICP queries received from neighbors.

icp.replies_recvThe number of ICP replies received from neighbors.

icp.query_timeoutsThe number of times that Squid timed out waiting for ICP replies to arrive.

icp.replies_queuedThe number of times Squid queued an ICP message after the initial attempt to send failed. See Section 14.2.1.24.

icp.kbytes_sentThe amount of traffic sent in all ICP messages, including both queries and replies.

icp.kbytes_recvThe amount of traffic received in all ICP messages, including both queries and replies.

icp.q_kbytes_sentThe amount of traffic sent to neighbors in ICP queries.

icp.r_kbytes_sentThe amount of traffic sent to neighbors in ICP replies.

icp.q_kbytes_recvThe amount of traffic received from neighbors in ICP queries.

icp.r_kbytes_recvThe amount of traffic received from neighbors in ICP replies.

icp.times_usedThe number of times ICP resulted in the selection of a neighbor as the next-hop for a cache miss.

cd.times_usedThe number of times Cache Digests resulted in the selection of a neighbor as the next-hop for a cache miss.

cd.msgs_sentThe number of Cache Digest messages sent to neighbors.

cd.msgs_recvThe number of Cache Digest messages received from neighbors.

cd.memoryThe amount of memory (in kilobytes) used by enabling the Cache Digests’ feature.

cd.local_memoryThe amount of memory (in kilobytes) used to store Squid’s own Cache Digest.

cd.kbytes_sentThe amount of traffic sent to neighbors in Cache Digest messages.

cd.kbytes_recvThe amount of traffic received from neighbors in Cache Digest messages.

unlink.requestsThe number of unlink requests given to the (optional) unlinkd process.

page_faultsThe number of (major) page faults as reported by

getrusage( ).select_loopsThe number of times Squid called

select( )orpoll( )in the main I/O loop.cpu_timeThe amount of CPU time (in seconds) accumulated, as reported by

getrusage( ).wall_timeThe amount of human time (in seconds) elapsed since Squid was started.

swap.outsThe number of objects (swap files) saved to disk.

swap.insThe number of objects (swap files) read from disk.

swap.files_cleanedThe number of orphaned cache files removed by the periodic cleanup procedure.

aborted_requestsThe number of server-side HTTP requests aborted due to client-side aborts.

peer_select: Peer Selection Algorithms

This page contains a lot of low-level detail about cache digests that I won’t discuss. Most of the numbers are meaningful only to the developers that originally wrote the Cache Digest implementation.

However, at the end of this page is a little table that

compares Algorithm usage:

Algorithm usage: Cache Digest: 27 ( 24%) Icp: 84 ( 76%) Total: 111 (100%)

In this example, you can see that Squid sent 111 requests to one of its neighbors: 27 are due to Cache Digests and 84 are due to ICP. In this context, ICP also includes HTCP.

digest_stats: Cache Digest and ICP Blob

This page is actually just a concatenation of the following other cache manager pages:

Traffic and Resource Counters

5 Minute Average of Counters

Full Histogram Counts

Peer Selection Algorithms

Store Digest

Its only purpose is to enable developers to take a snapshot of a number of statistics with a single request.

5min: 5 Minute Average of Counters

This page shows a five-minute average of the data in the Traffic and Resource Counters page. In addition to the counters mentioned in Section 14.2.1.30, this page also contains the following values:

client_http.all_median_svc_timeThe median service (response) time for all client requests from the last five minutes.

client_http.miss_median_svc_timeThe median service time for cache misses from the last five minutes.

client_http.nm_median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for requests logged as

TCP_IMS_HIT. See “Not-Modified Replies” in Section 14.2.1.24.client_http.nh_median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for Near Hits (

TCP_REFRESH_HITrequests).client_http.hit_median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for unvalidated cache hits.

icp.query_median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for ICP queries sent by Squid (how long it takes for the neighbors to reply to our queries).

icp.reply_median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for ICP queries received by Squid (how long it takes Squid to reply to its neighbor’s queries). ICP processing normally occurs faster than the process clock is updated, so this value is always zero.

dns.median_svc_timeThe five-minute median service time for DNS queries.

select_fdsThe mean rate at which the main I/O loop scans file descriptors with

select( )orpoll( ). Note: a low number doesn’t necessarily indicate poor performance. It may just be that Squid often has no work to do.average_select_fd_periodThe mean number of seconds required to scan a file descriptor in the main I/O loop.

median_select_fdsThe five-minute median number of ready file descriptors each time Squid calls

select( )orpoll( )(the median of theselect( )/poll( )return value). Unfortunately, this value is almost always zero because Squid’s functions for calculating the median don’t work very well with theselect_fdshistogram, in which 0 and 1 are the most common values.syscalls.selectsThe five-minute mean rate of calls to

select( )/poll( ). If Squid is usingpoll( )on your system, the variable is called syscalls.polls. This value may be a little larger than select_loops, because the latter only includes calls in the main I/O loop.syscalls.disk.opensThe five-minute mean rate of

open( )calls for disk files.syscalls.disk.closesThe five-minute mean rate of

close( )calls for disk files.syscalls.disk.readsThe five-minute mean rate of

read( )calls for disk files.syscalls.disk.writesThe five-minute mean rate of

write( )calls for disk files.syscalls.disk.seeksThe five-minute mean rate of

seek( )calls for disk files. Probably zero unless you are using aufs, which always callsseek( )before reading.syscalls.disk.unlinksThe five-minute mean rate of

unlink( )(or, in some cases,truncate( )) calls for disk files.syscalls.sock.acceptsThe five-minute mean rate of

accept( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.socketsThe five- minute mean rate of

socket( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.connectsThe five-minute mean rate of

connect( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.bindsThe five-minute mean rate of

bind( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.closesThe five-minute mean rate of

close( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.readsThe five-minute mean rate of

read( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.writesThe five-minute mean rate of

write( )calls for network sockets.syscalls.sock.recvfromsThe five-minute mean rate of

recvfrom( )calls for network sockets. Used for UDP-based protocols, such as DNS, ICP, HTCP, and some interprocess communication.syscalls.sock.sendtosThe five-minute mean rate of

sendto( )calls for network sockets. Used for UDP-based protocols, such as DNS, ICP, HTCP, and some interprocess communication.

60min: 60 Minute Average of Counters

This page shows a 60-minute average of the data in the Traffic and Resource Counters page. The descriptions are identical to those for the 5 Minute Average of Counters page, except the measurements are taken over one hour.

utilization: Cache Utilization

This page displays averages of the counters (see Traffic and Resource Counters and 5 Minute Average of Counters) over various time spans. The same values are reported for 5-minute, 15-minute, 1-hour, 8-hour, 1-day, and 3-day intervals.

This page, with a poorly chosen name, exists primarily so that developers can take a quick snapshot of statistics for testing purposes.

histograms: Full Histogram Counts