Chapter 10. Talking to Other Squids

For one reason or another, you may find that you want Squid to forward its cache misses to another cache or HTTP proxy. This is necessary, for example, if you are using Squid inside a large corporate network that has one or more firewalls protecting you from the outside world. If your caching service is actually a cluster of Squid caches, you probably want them to cooperate with each other to minimize duplication of cached responses. You can also use Squid as a content router—routing web traffic in different directions based on some aspect of the request. Or, perhaps you’d like to participate in an informal collection of caches to further improve response time and reduce wide-area network traffic.

Intercache communication is a complex undertaking, and Squid has numerous features and protocols to accomplish the task. After explaining some of the terminology and discussing the issues, I’ll introduce the configuration file directives that control request routing. Following that I describe the nifty network measurement database.

Most likely, you’ll use one or more of Squid’s intercache protocols to assist in communicating with the other caches or proxies. The Internet Cache Protocol (ICP) is the oldest but not necessarily the best. It is widely implemented in non-Squid products, so you may need to use it for that reason alone. The newer protocols are Cache Digests, the Hypertext Caching Protocol (HTCP), and the Cache Array Routing Protocol (CARP).

There are many choices here, so I’ll spend a bit of time explaining how everything works inside Squid.

Some Terminology

Caching hierarchy is the name generally given to a collection of caches (or proxies) that forward requests to one another. We say that the members of the hierarchy are neighbors or peers.

Neighbor caches have either a parent or sibling relationship. Topologically, parent caches are one level up in the hierarchy, while siblings are on the same level. The real difference is that parents can forward cache misses for their children. Siblings, on the other hand, aren’t allowed to forward cache misses. This means that, before sending a request to a sibling, the originator should know that it will be a cache hit. Intercache protocols like ICP, HTCP, and Cache Digests can predict cache hits in neighbors. CARP, however, can’t.

Sometimes, cache hierarchies aren’t really hierarchical. Consider, for example, a group of five sibling caches. Because there are no parents or children, there is no sense of up or down. In this case, you could call it a cache mesh, or even an array, instead of a hierarchy.

Why (Not) Use a Hierarchy?

A neighbor cache improves performance by providing some extra fraction of requests as cache hits. In other words, some of the requests that are misses in your cache may be hits in the neighbor cache. If your cache can download these neighbor hits faster than from the origin server, the hierarchy should improve performance overall. The downside is that neighbor caches usually provide only a small percentage of requests as hits. About 5%, or maybe 10% if you’re lucky, of your requests that are cache misses will be hits in a neighbor. In some cases, this small benefit doesn’t justify the hassle of joining a hierarchy. In other cases, such as networks with poor or overutilized connectivity, hierarchies definitely improve performance for end users.

If you use Squid inside a firewalled network, you may need to configure the firewall proxy as a parent. In this case, Squid forwards every request to the firewall because it can’t connect directly to outside origin servers. If you have some origin servers inside the firewall, you can instruct Squid to connect to them directly.

You can also use a hierarchy to send web traffic in different directions. This is sometimes called application-layer routing, or more recently, content routing. Consider, for example, a large organization with two Internet connections. Perhaps the second connection costs less, or has higher latency, than the other. This organization may want to use the second connection for low-priority traffic, such as downloading binaries, audio and video files, or other kinds of large transfers. Or, perhaps they want to send all HTTP traffic over one link, and non-HTTP traffic over the other. Or, perhaps certain users’ traffic should go through the low-priority connection, while premium customers get to use the more expensive link. You can accomplish any of these scenarios with a hierarchy of caching proxies.

Trust is one of the most important issues for the members of a cache hierarchy. You must trust your neighbors to serve correct, unmodified responses. You must trust them with sensitive information, such as the URIs requested by your users. You must trust that they maintain secure and up-to-date systems to minimize the chances of unauthorized access and denials of service.

Another problem with hierarchies is the way that they normally propagate errors. When a neighbor cache experiences an error, such as an unreachable server, it generates an HTML page that explains the error and its origin. Your users may become confused if they get errors from neighbor caches outside the immediate organization. If the problem persists, they’ll have a hard time finding an administrator who can help them.

Sibling relationships are subject to special problem, known as false hits. This occurs when Squid sends a request to a sibling, believing it will be a cache hit, but the sibling is unable to satisfy the request without contacting the origin server. False hits happen in a number of circumstances, but usually with a low probability. Furthermore, Squid and other HTTP proxies have features for automatically retrying such requests so that the user isn’t even aware of the problem.

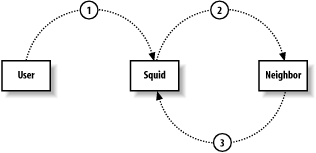

A forwarding loop is another problem sometimes seen in cache hierarchies. It occurs when Squid forwards a request somewhere, but that request comes back to Squid again, as shown in Figure 10-1.

Forwarding loops typically happen when two caches consider each other parents. If you have such an arrangement, make sure that you use the cache_peer_access directive to prevent loops. For example, if the neighbor’s IP address is 192.168.1.1, the following lines ensure Squid won’t cause a forwarding loop:

acl FromNeighbor src 192.168.1.1 cache_peer_access the.neighbor.name deny FromNeighbor

Forwarding loops can also occur with HTTP interception, especially if the interception device is on the path between Squid and an origin server.

Squid detects forwarding loops by looking for its own hostname in

the Via header. You may actually get

false forwarding loops if two cooperating caches have the same hostname.

The unique_hostname directive is useful in this

situation. Note that if the Via

header is filtered out (e.g., with headers_access),

Squid can’t detect forwarding loops.

Telling Squid About Your Neighbors

The cache_peer directive defines your neighbor caches and tells Squid how to communicate with them:

cache_peerhostnametypehttp-porticp-port[options]

The first argument is the neighbor’s hostname, or IP address. You can safely use hostnames here because Squid doesn’t block while resolving them. In fact, Squid periodically resolves the hostname in case the IP address changes while Squid is running. Neighbor hostnames must be unique: you can’t have two neighbors with the same name, even if they have different ports.

The second argument specifies the type of neighbor cache. The choices are: parent, sibling, or multicast. Parent and sibling are straightforward. I’ll talk about multicast in Section 10.6.3.

The third argument is the neighbor’s HTTP port number. It should correspond to the neighbor’s http_port (or equivalent) setting. You must always specify a nonzero HTTP port number.

The fourth argument specifies either the ICP or HTCP port number.

By default, Squid uses ICP to query other caches. That is, Squid sends

ICP queries to the neighbor on the port given here. If you add the

htcp option, Squid sends HTCP queries

to this port instead. The default ICP port is 3130, and the default HTCP

port is 4827. Make sure that you change the port number if you add the

htcp option. Setting this port number

to zero disables both ICP and HTCP. However, you should instead (or

also) use the no-query option to

disable these protocols.

cache_peer Options

The cache_peer directive has quite a few options. I’ll describe some of them here, and the others in the sections relating to specific protocols.

proxy-onlyThis option instructs Squid not to store any responses it receives from the neighbor. This is often useful when you have a cluster and don’t want a resource to be stored on more than one cache.

weight=nThis option is specific to ICP/HTCP. See Section 10.6.2.1.

ttl=nThis option is specific to multicast ICP. See Section 10.6.3.

no-queryThis option is specific to ICP/HTCP. See Section 10.6.2.1.

defaultThis option specifies the neighbor as a suitable choice in the absence of other hints. Squid normally prefers to forward a cache miss to a parent that is likely to have a cached copy of the particular resource. Sometimes Squid won’t have any clues (e.g., if you disable ICP/HTCP with

no-query). In these cases, Squid looks for a parent that has been marked as a default choice.round-robinThis option is a simple load-sharing technique. It makes sense only when you mark two or more parent caches as

round-robin. Squid keeps a counter for each parent. When it needs to forward a cache miss, Squid selects the parent with the lowest counter.multicast-responderThis option is specific to multicast ICP. See Section 10.6.3.

closest-onlyThis option is specific to ICP/HTCP. See Section 10.6.2.1.

no-digestThis option is specific to Cache Digests. See Section 10.7.

no-netdb-exchangeThis option tells Squid not to request the neighbor’s netdb database (see Section 10.5). Note, this refers to the bulk transfer of the RTT measurements, not the inclusion of these measurements in ICP miss replies.

no-delayThis option tells Squid to ignore any delay pools settings for requests to the neighbor. See Appendix C for more information on delay pools.

login=credentialsThis option instructs Squid to send HTTP authentication credentials to the neighbor. It has three different formats:

login=user:passwordThis is the most commonly used form. It causes Squid to add the same username and password in every request going to the neighbor. Your users don’t need to enter any authentication information.

login=PASSSetting the value to

PASScauses Squid to pass the user’s authentication credentials to the neighbor cache. It works only for HTTP basic authentication. Squid doesn’t add or modify any authentication information.If your Squid is configured to require proxy authentication (i.e., with a proxy_auth ACL), the neighbor cache must use the same username and password database. In other words, you should use the

PASSform only for a group of caches owned and operated by a single organization. This feature is dangerous because Squid doesn’t remove the authentication credentials from forwarded requests.login=*:passwordWith this form, Squid changes the password, but not the username, in requests that it forwards. It allows the neighbor cache to identify individual users, but doesn’t expose their passwords. This form is less dangerous than using

PASS, but does have some privacy implications.

Use this feature with extreme caution. Even if you ignore the privacy issues, this feature may cause undesirable side effects with upstream proxies. For example, I know of at least one other caching product that only looks at the credentials of the first request on a persistent connection. It apparently assumes (incorrectly) that all requests on a single connection come from the same user.

connect-timeout=nThis option specifies how long Squid should wait when establishing a TCP connection to the neighbor. Without this option, the timeout is taken from the global connect_timeout directive, which has a default value of 120 seconds. By using a lower timeout, Squid gives up on the neighbor quickly and may try to send the request to another neighbor or directly to the origin server.

digest-url=urlThis option is specific to Cache Digests. See Section 10.7.

allow-missThis option instructs Squid to omit the

Cache-Control: only-if-cacheddirective for requests sent to a sibling. You should use this only if the neighbor has enabled the icp_hit_stale directive and isn’t using a miss_access list.max-conn=nThis option places a limit on the number of simultaneous connections that Squid can open to the neighbor. When this limit is reached, Squid excludes the neighbor from its selection algorithm.

htcpThis option designates the neighbor as an HTCP server. In other words, Squid sends HTCP queries, instead of ICP, to the neighbor. Note that Squid doesn’t accept ICP and HTCP queries on the same port. When you add this option, don’t forget to change the

icp-portvalue as well. See Section 10.8.1. HTCP support requires the—enable-htcpoption when running ./configure.carp-load-factor=fThis option makes the neighbor, which must be a parent, a member of a CARP array. The sum of all

fvalues, for all parents, must equal 1. I cover CARP in Section 10.9. CARP support requires the—enable-carpoption when running ./configure.

Neighbor State

Squid keeps a variety of statistics and state information about each of its neighbors. One of

the most important is whether Squid thinks the neighbor is

alive (up) or dead (down).

The neighbor’s alive/dead state affects many aspects Squid’s selection

procedures. The algorithm for determining the alive/dead state is a

little bit complicated, so I’ll go through it here. If you want to

follow along in the source code, look at the neighborUp( ) function.

Squid uses both TCP (HTTP) and UDP (ICP/HTCP) communication to determine the state. The TCP state defaults to alive, but changes to dead if 10 consecutive TCP connections fail. When this happens, Squid initiates probe connections, no more than once every connect_timeout time period (the global directive, not the cache_peer option). The state remains dead until one of the probe connections succeeds.

If the no-query option isn’t

set (meaning Squid is sending ICP/HTCP queries to the neighbor), the

UDP layer communication also factors into the alive/dead algorithm.

The UDP state defaults to alive, but changes to dead if Squid doesn’t

get any ICP/HTCP replies for a certain amount of time—the value of the

dead_peer_timeout directive.

Squid also marks a neighbor dead if its hostname doesn’t resolve to any IP addresses. When Squid determines a neighbor is dead, it writes an entry in cache.log. Here’s an example:

2003/09/29 01:13:46| Detected DEAD Sibling: bo2.us.ircache.net/3128/3130

When communication with the neighbor is reestablished, Squid logs a message like this:

2003/09/29 01:13:49| Detected REVIVED Sibling: bo2.us.ircache.net/3128/3130

A neighbor’s state affects neighbor-selection algorithms in the following ways:

Squid doesn’t expect to receive ICP/HTCP replies from dead neighbors. Squid sends ICP queries to dead neighbors no more than once each dead_peer_timeout interval. See Appendix A.

A dead parent is excluded from the following algorithms: Cache Digests, round-robin parent, first up parent, default parent, and closest parent.

CARP is special: any failed TCP connections (not the 10 required to become dead) excludes the parent from the CARP algorithm.

There is no way to force Squid to send HTTP requests to a dead

neighbor. If all neighbors are dead, Squid will try connecting to the

origin server. If you don’t allow Squid to talk to the origin server

(with never_direct, for example), Squid returns a

cannot forward error

message:

This request could not be forwarded to the origin server or to any

parent caches. The most likely cause for this error is that:

* The cache administrator does not allow this cache to make

direct connections to origin servers, and

* All configured parent caches are currently unreachable.Altering the Relationship

The neighbor_type_domain directive allows you to change the relationship with your neighbor based on the origin server’s hostname. This is useful, for example, if your neighbor is willing to serve cache hits for any request but misses only for certain nearby domains. The syntax is:

neighbor_type_domainneighbor.host.namerelationship[!]domain...

For example:

cache_peer squid.uk.web-cache.net sibling 3128 3130 neighbor_type_domain squid.uk.web-cache.net parent .uk

Of course, the squid.uk.web-cache.net cache in this example should utilize appropriate miss_access rules to enforce the sibling relationship for non-UK requests. Note that domain names are matched to hostnames as described in Section 6.1.1.2.

Restricting Requests to Neighbors

Many people who use hierarchical caching need to control or limit requests that Squid sends to its neighbors. Squid has seven different directives that affect request routing: cache_peer_access, cache_peer_domain, never_direct, always_direct, hierarchy_stoplist, nonhierarchical_direct, and prefer_direct.

cache_peer_access

The cache_peer_access directive defines an access list for a neighbor cache. That is, it determines which requests may, or may not, be sent to the neighbor.

You can use this, for example, to split the flow of FTP and HTTP requests. You can send all FTP URIs to one parent and all HTTP URIs to another:

cache_peer A-parent.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer B-parent.my.org parent 3128 3130 acl FTP proto FTP acl HTTP proto HTTP cache_peer_access A-parent allow FTP cache_peer_access B-parent allow HTTP

This configuration ensures that A-parent receives only requests for FTP

URIs, while B-parent receives only

requests for HTTP URIs. This includes ICP/HTCP queries as well.

You might also use cache_peer_access to enable or disable a neighbor cache during certain times of the day:

cache_peer A-parent.my.org parent 3128 3130 acl DayTime time 07:00-18:00 cache_peer_access A-parent.my.org deny DayTime

cache_peer_domain

The cache_peer_domain directive is an earlier form of cache_peer_access. Rather than using the full access control feature set, it only uses domain names in URIs. It is often used to partition a group of parent caches by domain name. For example, if you have a global intranet, you may want to send requests to caches located on each continent:

cache_peer europe-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer asia-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer aust-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer africa-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer na-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer sa-cache.my.org parent 3128 3130 cache_peer_domain europe-cache.my.org parent .ch .dk .fr .uk .nl .de .fi ... cache_peer_domain asia-cache.my.org parent .jp .kr .cn .sg .tw .vn .hk ... cache_peer_domain aust-cache.my.org parent .nz .au .aq ... cache_peer_domain africa-cache.my.org parent .dz .ly .ke .mz .ma .mg ... cache_peer_domain na-cache.my.org parent .mx .ca .us ... cache_peer_domain sa-cache.my.org parent .br .cl .ar .co .ve ...

Of course, this scheme doesn’t address the popular global top-level domains, such as .com.

never_direct

The never_direct directive is an access list for requests that must never be sent directly to an origin server. When a request matches this access list, it must be sent to a neighbor (usually parent) cache.

For example, if Squid is behind a firewall, it may be able to talk to your “internal” servers directly but must send all requests for external servers via the firewall proxy (a parent). You can tell Squid “never connect directly to sites outside the firewall.” To do so, tell Squid what is inside the firewall:

acl InternalSites dstdomain .my.org never_direct allow !InternalSites

The syntax is a little strange. never_direct allow foo means Squid will not

go directly for requests that match “foo.” Since the set of internal

sites is easy to specify, I used the negation operator (!) to match

external sites, which Squid must never directly contact.

Note that this example doesn’t force Squid to connect directly to sites that match the InternalSites ACL. The never_direct access rule can only force Squid not to contact certain origin servers. You must use the always_direct rule to force direct connections to origin servers.

You must take care when using never_direct in combination with the other directives that control request routing. You can easily create an impossible situation. Here’s an example:

cache_peer A-parent.my.org parent 3128 3130 acl COM dstdomain .com cache_peer_access A-parent.my.org deny COM never_direct allow COM

This configuration creates a contradiction because any request whose domain name ends with .com must go through a neighbor cache. However, I defined only one neighbor cache, and don’t allow the .com requests to go there. When this happens, Squid emits the “cannot forward” error message mentioned earlier in Chapter 10.

always_direct

As you can probably guess, the list of always_direct rules tell Squid that some

requests must be forwarded directly to the origin server. For example,

many organizations want to keep their local traffic local. An easy way

to do this is to define an IP address-based ACL and put it in the

always_direct rule list:

acl OurNetwork src 172.16.3.0/24 always_direct allow OurNetwork

hierarchy_stoplist

Internally, Squid flags each client request as either hierarchical or nonhierarchical. A

nonhierarchical request is one that is unlikely to result in a cache

hit. For example, responses to POST

requests are almost never cachable. Forwarding requests for uncachable

objects to neighbors is a waste of resources when Squid can simply

connect to the origin server.

Some of the rules for differentiating hierarchical and

nonhierarchical requests are hardcoded in Squid. For example, the

POST and PUT methods are always nonhierarchical.

However, the hierarchy_stoplist directive allows

you to customize the algorithm. It contains a list of strings that,

when found in a URI, make the request nonhierarchical. The default

list is:

hierarchy_stoplist ? cgi-bin

Thus, any request that contains a question mark or the cgi-bin string matches the stoplist and

becomes nonhierarchical.

By default, Squid prefers to send nonhierarchical requests directly to origin servers. Because they are unlikely to result in cache hits, they are generally an extra burden on neighbor caches. However, the never_direct access control rules override hierarchy_stoplist. In particular, Squid:

Never sends ICP/HTCP queries for nonhierarchical requests unless the request matches a never_direct rule

Never sends ICP/HTCP queries to sibling caches for nonhierarchical requests

Never looks in neighbor cache digests for nonhierarchical requests

nonhierarchical_direct

This directive controls the way that Squid forwards nonhierarchical (i.e., probably uncachable) requests. By default, Squid prefers to send nonhierarchical requests directly to origin servers. This is because such requests are unlikely to result in cache hits. I feel it is always better to get them directly from the origin server, rather than waste time looking for them in neighbor caches. If, for some reason, you want to route such requests through the hierarchy, disable this directive:

nonhierarchical_direct off

prefer_direct

This directive controls the way that Squid forwards hierarchical (i.e., probably cachable) requests. By default, Squid prefers to send such requests to a neighbor cache first and then directly to the origin server. You can reverse this behavior by enabling the directive:

prefer_direct on

In this way, your neighbor caches become a backup if communication with the origin server fails.

The Network Measurement Database

Squid’s network measurement database (netdb) is designed to measure the proximity of origin servers. In other words, by querying this database, Squid knows how close it is to the origin server. The database includes ICMP round-trip time (RTT) measurements and hop counts. Squid normally uses only the RTT measurements but can also use the hop counts in some situations.

To enable netdb, you must configure Squid with the —enable-icmp

option. You must also install the pinger program with superuser permissions, as

described in Section 3.6. When

everything is working correctly, you should see a message like this in

cache.log:

2003/09/29 00:01:03| Pinger socket opened on FD 28

When netdb is enabled, Squid sends ICMP “pings” to origin servers. The ICMP messages are actually sent and received by the pinger program, which runs as root. Squid is careful not to send pings too frequently, which may annoy web site administrators. By default, Squid waits at least five minutes before sending another ping to the same host, or to any other host on the same /24 subnet. You can adjust the interval with the netdb_ping_period directive.

The ICMP pings are generally small in size (less than 100 bytes). Squid includes the origin server hostname in the payload of the ICMP message, along with a timestamp.

To reduce memory requirements, Squid aggregates the netdb data by /24 subnets. Squid assumes that all hosts within the subnet have similar RTT and hop-count measurements. This scheme also allows Squid to estimate the proximity of a new origin server when other servers in the subnet have already been measured.

Along with the RTT and hop-count measurements, Squid also stores a list of hostnames associated with the subnet. A typical record may look something like this:

Subnet 140.98.193.0

RTT 76.5

Hops 20.0

Hosts services1.ieee.org

www.spectrum.ieee.org

www.ieee.orgThe netdb measurements are primarily used by ICP and HTCP. When you enable the query_icmp directive in squid.conf, Squid sets a flag in the ICP/HTCP queries that it sends to neighbors. This flag is a request to include proximity measurements in the ICP/HTCP reply. If your neighbors also enabled netdb, their replies should include RTT and hop-count measurements if available. Note that Squid always sends ICP replies immediately. It doesn’t wait for an ICMP measurement before replying to the query. See Section 10.6.2.2 for details on how ICP uses netdb.

Squid remembers the RTT values it learns from ICP/HTCP replies.

These values may be used later to optimize forwarding decisions. Squid

also supports a “bulk transfer” of netdb measurements via

what is called netdb exchange.

Squid periodically makes an HTTP request to a neighbor for its

netdb data. You can disable these requests with the

no-netdb-exchange option on the

cache_peer line.

The netdb_low and netdb_high directives control the size of the measurement database. When the number of stored subnets reaches netdb_high, Squid deletes the least recently used entries until the count is less than netdb_low.

The minimum_direct_hops and

minimum_direct_rtt directives instruct Squid to

connect directly to origin servers that are no more than some number of

hops, or milliseconds, away. Requests that meet this criteria are logged

with CLOSEST_DIRECT in access.log.

The cache manager’s netdb page displays the entire network measurement database, including values from neighbor caches. For example:

Network DB Statistics:

Network recv/sent RTT Hops Hostnames

63.241.84.0 1/ 1 25.0 9.0 www.xyzzy.com

sd.us.ircache.net 21.5 15.0

bo1.us.ircache.net 27.0 13.0

pb.us.ircache.net 70.0 11.0

206.100.24.0 5/ 5 25.0 3.0 wcarchive.cdrom.com ftp.cdrom.com

uc.us.ircache.net 23.5 11.0

bo1.us.ircache.net 27.7 7.0

pb.us.ircache.net 35.7 10.0

sd.us.ircache.net 72.9 10.0

146.6.135.0 1/ 1 25.0 13.0 www.cm.utexas.edu

bo1.us.ircache.net 32.0 11.0

sd.us.ircache.net 55.0 8.0

216.234.248.0 2/ 2 25.0 8.0 postfuture.com www1.123india.com

pb.us.ircache.net 44.0 14.0

216.148.242.0 1/ 1 25.0 9.0 images.worldres.com

sd.us.ircache.net 25.2 15.0

bo1.us.ircache.net 27.0 13.0

pb.us.ircache.net 69.5 11.0Here you can see that the server www.xyzzy.com has an IP address in the 63.241.84.0/24 block. The RTT from this cache to the origin server is 25 milliseconds. The neighbor cache sd.us.ircache.net is a little closer, at 21.5 milliseconds.

Internet Cache Protocol

ICP is a lightweight object location protocol invented as a part of the Harvest

project.[1] An ICP client sends a query message to one or more ICP

servers, asking if they have a particular URI cached. Each server

replies with an ICP_HIT, ICP_MISS, or other type of ICP message. The

ICP client uses the information in the ICP replies to make a forwarding

decision.

In addition to predicting cache hits, ICP is also useful for providing hints about network conditions between Squid and the neighbor. ICP messages are similar to ICMP pings in this regard. By measuring the query/response round-trip time, Squid can estimate network congestion. In the extreme case, ICP messages may be lost, indicating that the path between the two is down or congested. From this, Squid decides to avoid the neighbor for that particular request.

Increased latency is perhaps the most significant drawback to using ICP. The query/response exchange takes some time. Caching proxies are supposed to decrease response time, not add more latency. If ICP helps us discover cache hits in neighbors, then it may lead to an overall reduction in response time. See Section 10.10 for a description of the query algorithm implemented in Squid.

ICP also suffers from a number of design deficiencies: security, scalability, false hits, and the lack of a request method. The protocol doesn’t include any security features. In general, Squid can’t verify that an ICP message is authentic; it relies on address-based access controls to filter out unwanted ICP messages.

ICP has poor scaling properties. The number of ICP messages (and bandwidth) grows in proportion to the number of neighbors. Unless you use some kind of partitioning scheme, this places a practical limit on the number of neighbors you can have. I don’t recommend having more than five or six neighbors.

ICP queries contain only URIs, with no additional request headers.

This makes it difficult to predict cache hits with perfect accuracy. An

HTTP request may include additional headers (such as Cache-Control: max-stale=N) that turn a cache hit into a

cache miss. These false hits are particularly awkward for sibling

relationships.

Also missing from the ICP query message is the request method. ICP assumes that all

queries are for GET requests. A

caching proxy can’t use ICP to locate cached objects for non-GET request methods.

You can find additional information about ICP by reading:

My book Web Caching (O’Reilly)

RFCs 2186 and 2187

My article with kc claffy: “ICP and the Squid Web Cache” in the IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communication, April 1998

Being an ICP Server

When you use the icp_port directive, Squid automatically becomes an ICP server. That is, it listens for ICP messages on the port you’ve specified, or port 3130 by default. Be sure to tell your sibling and/or child caches if you decide to use a nonstandard port.

By default, Squid denies all ICP queries. You must use the icp_access rule list to allow queries from your neighbors. It’s usually easiest to do this with src ACLs. For example:

acl N1 src 192.168.0.1 acl N2 src 172.16.0.2 acl All src 0/0 icp_access allow N1 icp_access allow N2 icp_access deny All

Note that only ICP_QUERY

messages are subject to the icp_access rules. ICP client functions,

such as sending queries and receiving replies, don’t require any

special access controls. I also recommend that you take advantage of

your operating system’s packet filtering features (e.g., ipfw, iptables, and pf) if possible. Allow UDP messages on the

ICP port from your trusted neighbors and deny them from all other

hosts.

When Squid denies an ICP query due to the icp_access rules, it sends back an ICP_DENIED message. However, if Squid

detects that more than 95% of the recent queries have been denied, it

stops responding for an hour. When this happens, Squid writes a

message in cache.log:

WARNING: Probable misconfigured neighbor at foo.web-cache.com WARNING: 150 of the last 150 ICP replies are DENIED WARNING: No replies will be sent for the next 3600 seconds

If you see this message, you should contact the administrator responsible for the misconfigured cache.

Squid was designed to answer ICP queries immediately. That is,

Squid can tell whether or not it has a fresh, cached response by

checking the in-memory index. This is also why Squid is a bit of a

memory hog. When an ICP query comes in, Squid calculates the MD5 hash

of the URI and looks for it in the index. If not found, Squid sends

back an ICP_MISS message. If found,

Squid checks the expiration time. If the object isn’t fresh, Squid

returns ICP_MISS. For fresh

objects, Squid returns ICP_HIT.

By default, Squid logs all ICP queries (but not responses) to access.log. If you have a lot of busy neighbors, your log file may become too large to manage. Use the log_icp_queries directive to prevent logging of these queries. Although you’ll lose the detailed logging for ICP, you can still get some aggregate stats via the cache manager (see Section 14.2.1.24).

If you have sibling neighbors, you’ll probably want to use the miss_access directive to enforce the relationship. It specifies an access rule for cache misses. It is similar to http_access but is checked only for requests that must be forwarded. The default rule is to allow all cache misses. Unless you add some miss_access rules, any sibling cache can become a child cache and forward cache misses through your network connection, thus stealing your bandwidth.

Your miss_access rules can be relatively simple. Don’t forget to include your local clients (i.e., web browsers) as well. Here’s a simple example:

acl Browsers src 10.9.0.0/16 acl Child1 src 172.16.3.4 acl Child2 src 192.168.2.0/24 acl All src 0/0 miss_access allow Browsers miss_access allow Child1 miss_access allow Child2 miss_access deny All

Note that I haven’t listed any siblings here. The child caches

are allowed to request misses through us, but the siblings are not.

Their cache miss requests are denied by the deny All rule.

The icp_hit_stale directive

One of the problems with ICP is that it returns ICP_MISS

for cached but stale responses. This is true even if the response is

stale, but valid (such that a validation request returns “not

modified”). Consider a simple hierarchy with a child and two parent

caches. An object is cached by one parent but not the other. The

cached response is stale, but unchanged, and needs validation. The

child’s ICP query results in two ICP_MISS replies. Not knowing that the

stale response exists in the first parent, the child forwards its

request to the second parent. Now the object is stored in both

parents, wasting resources.

You might find the icp_hit_stale

directive useful in this situation. It tells Squid to return an

ICP_HIT for any cached object,

even if it is stale. This is perfectly safe for parent relationships

but can create problems for siblings.

Recall that in a sibling relationship, the client cache is

only allowed to make requests that are cache hits. Enabling the

icp_hit_stale directive increases the number of

false hits because Squid must validate the stale responses. Squid

normally handles false hits by adding the Cache-Control: only-if-cached directive to

HTTP requests sent to siblings. If the sibling can’t satisfy the

HTTP request as a cache hit, it returns an HTTP 504 (Gateway

Timeout) message instead. When Squid receives the 504 response, it

forwards the request again, but only to a parent or the origin

server.

It makes little sense to enable

icp_hit_stale for sibling relationships if all

the false hits must be reforwarded. This is where the ICP client’s

allow-miss option to

cache_peer becomes useful. When the allow-miss option is set, Squid omits the

only-if-cached directive in HTTP

requests it sends to siblings.

If you enable icp_hit_stale, you also need to make sure that miss_access doesn’t deny cache-miss requests from siblings. Unfortunately, there is no way to make Squid allow only cache-misses for cached, stale objects. Allowing cache misses for siblings also leaves your cache open to potential abuse. The administrator of the sibling cache may change it to a parent relationship without your knowledge or permission.

The ICP_MISS_NOFETCH feature

The command-line -Y option to Squid causes it to return ICP_MISS_NOFETCH, instead of ICP_MISS, while rebuilding the in-memory

indexes. ICP clients that receive ICP_MISS_NOFETCH responses should not send

HTTP requests for those objects. This reduces the load placed on

Squid and allows the rebuild process to complete sooner.

The test_reachability directive

If you enable the netdb feature (see

Section 10.5), you might

also be interested in enabling the

test_reachability directive. The goal behind it

is to accept only requests for origin servers Squid can reach.

Enabling test_reachability causes Squid to

return ICP_MISS_NOFETCH, instead

of ICP_MISS, for origin server

sites that don’t respond to ICMP pings. This can help reduce the

number of failed HTTP requests and increase the chance that the end

user receives the data promptly. However, a significant percentage

of origin server sites intentionally filter out ICMP traffic. For

these, Squid returns ICP_MISS_NOFETCH even though an HTTP

connection would succeed.

Enabling test_reachability also causes Squid to make netdb measurements in response to ICP queries. If Squid doesn’t have any RTT measurements for the origin server in question, it sends out an ICMP ping (subject to the rate limiting mentioned previously).

Being an ICP Client

First, you must use the cache_peer directive to define your neighbor caches. See the section Section 10.3.

Second, you must also use the icp_port directive, even if your Squid is only an ICP client. This is because Squid uses the same socket for sending and receiving ICP messages. It is perhaps a bad design decision in retrospect. If you are a client only, use icp_access to block queries. For example:

acl All src 0/0 icp_access deny All

Squid sends ICP queries to its neighbors for most requests by default. See Section 10.10 for a complete description of the way that Squid decides when, and when not, to query its neighbors.

After sending one or more queries, Squid waits some amount of

time for ICP replies to arrive. If Squid receives an ICP_HIT from one of its neighbors, it

forwards the request there immediately. Otherwise, Squid waits until

all replies arrive or until a timeout occurs. The timeout is

calculated dynamically, based on the following algorithm.

Squid knows the average round-trip time between itself and each neighbor, taken from recent ICP transactions. When querying a group of neighbors, Squid calculates the mean of all the neighbor ICP RTTs, and then doubles it. In other words, the query timeout is twice the mean of RTTs for each neighbor queried. Squid ignores neighbors that appear to be down when calculating the timeout.

In some cases, the algorithm doesn’t work well, especially if you have neighbors with widely varying RTTs. You can change the upper limit on the timeout using the maximum_icp_query_timeout directive. Alternatively, you can make Squid always use a constant timeout value with the icp_query_timeout directive.

cache_peer options for ICP clients

weight=

n allows you to weight parent caches artificially when using ICP/HTCP. It

comes into play only when all parents report a cache miss. Normally,

Squid selects the parent whose reply arrives first. In fact, it

remembers which parent has the best RTT for the query. Squid

actually divides the RTT by the weight, so that a parent with

weight=2 is treated as if it’s

closer to Squid than it really is.

no-query disables ICP/HTCP

for the neighbor. That is, your cache won’t send any queries to the

neighbor for cache misses. It is often used with the default option.

closest-only refers to one

of Squid’s netdb features. It instructs Squid

to select the parent based only on netdb RTT

measurements and not the order in which replies arrive. This option

requires netdb at both ends.

ICP and netdb

As mentioned in the section Section 10.5, netdb is mostly used with ICP queries. In this section, we’ll follow all the steps involved in this process.

A Squid cache, acting as an ICP client, prepares to send a query to one or more neighbors. If query_icmp is set, Squid sets the

SRC_RTTflag in the ICP query. This informs the ICP server that Squid would like to receive an RTT measurement in the ICP reply.The neighbor receives the query with the

SRC_RTTflag set. If the neighbor is configured to make netdb measurements, it searches the database for the origin server hostname. Note that the neighbor doesn’t query the DNS for the origin server’s IP address. Thus, it finds a netdb entry only if that particular host has already been measured.If the host exists in the netdb database, the neighbor includes the RTT and hop count in the ICP reply. The

SRC_RTTflag is set in the reply to indicate the measurement is present.When Squid receives the ICP reply with the

SRC_RTTflag set, it extracts the RTT and hop count. These are added to the local netdb so that, in the future, Squid knows the approximate RTT from the neighbor to the origin server.An

ICP_HITreply causes Squid to forward the HTTP request immediately. If, on the other hand, Squid receives onlyICP_MISSreplies, it selects the parent with the smallest (nonzero) measured RTT to the origin server. The request is logged to access.log withCLOSEST_PARENT_MISS.If none of the parent

ICP_MISSreplies contain RTT values, Squid selects the parent whose ICP reply arrived first. In this case, the request is logged withFIRST_PARENT_MISS. However, if theclosest-onlyoption is set for a parent cache, Squid never selects it as a “first parent.” In other words, the parent is selected only if it is the closest parent to the origin server.

Multicast ICP

As you already know, ICP has poor scaling properties. The number of messages is

proportional to the number of neighbors. Because Squid sends identical

ICP_QUERY messages to each

neighbor, you can use multicast to reduce the number of messages

transmitted on the network. Rather than send N

messages to N neighbors, Squid sends one message

to a multicast address. The multicast routing infrastructure makes

sure each neighbor receives a copy of the message. See the book

Interdomain Multicast Routing: Practical Juniper Networks

and Cisco Systems Solutions by Brian M. Edwards, Leonard

A. Giuliano, and Brian R. Wright (Addison Wesley) for more information

on the inner workings of multicast.

Note that ICP replies are always sent via unicast. This is because ICP replies may be different (e.g., hit versus miss) and because the unicast and multicast routing topologies may differ. Because ICP is also used to indicate network conditions, an ICP reply should follow the same path an HTTP reply takes. The bottom line is that multicast only reduces message counts for queries.

Historically, I’ve found multicast infrastructure unstable and unreliable. It seems to be a low priority for many ISPs. Even though it works one day, something may break a few days or weeks later. You’re probably safe using multicast entirely within your own network, but I don’t recommend using it for ICP on the public Internet.

Multicast ICP server

A multicast ICP server joins one or more multicast group addresses to receive messages. The mcast_groups directive specifies these group addresses. The values must be multicast IP addresses or hostnames that resolve to multicast addresses. The IPv4 multicast address range is 224.0.0.0-239.255.255.255. For example:

mcast_groups 224.11.22.45

An interesting thing about multicast is that hosts, rather than applications, join a group. When a host joins a multicast group, it receives all packets that are transmitted to that group. This means that you need to be a little bit careful when selecting a multicast group to use for ICP. You don’t want to select an address that’s already being used by another application. When this kind of group overlap occurs, the two groups become joined and receive each other’s traffic.

Multicast ICP client

Multicast ICP clients transmit queries to one or more multicast group addresses. Thus, the hostname argument of the cache_peer line must be, or resolve to, a multicast address. For example:

cache_peer 224.0.14.1 multicast 3128 3130 ttl=32

The HTTP port number (e.g., 3128) is irrelevant in this case because Squid never makes HTTP connections to a multicast neighbor.

Realize that multicast groups don’t have any access controls. Any host can join any multicast group address. This means that, unless you’re careful, others may be able to receive the multicast ICP queries sent by your Squid. IP multicast has two ways to prevent packets from traveling too far: TTLs and administrative scoping. Because ICP queries may carry sensitive information (i.e., URIs that your users access), I recommend using an administratively scoped address and properly configured routers. See RFC 2365 for more information.

The ttl=n option is for

multicast neighbors only. It is the multicast TTL value to use for

ICP queries. It controls how far away the ICP queries can travel.

The valid range is 0-128. A larger value allows the multicast

queries to travel farther, and possibly be intercepted by outsiders.

Use a lower number to keep the queries close to the source and

within your network.

Multicast ICP clients must also tell Squid about the neighbors

that will be responding to queries. Squid doesn’t blindly trust any

cache that happens to send an ICP reply. You must tell Squid about

legitimate, trusted neighbors. The multicast-responder option to

cache_peer identifies such neighbors. For

example, if you know that 172.16.2.3 is a trusted neighbor on the

multicast group, you should add this line to squid.conf:

cache_peer 172.16.3.2 parent 3128 3130 multicast-responder

You can, of course, use a hostname instead of an IP address. ICP replies from foreign (unlisted) neighbors are ignored, but logged in cache.log.

Squid normally expects to receive an ICP reply for each query that it sends. This changes, however, with multicast because one query may result in multiple replies. To account for this, Squid periodically sends out “probes” on the multicast group address. These probes tell Squid how many servers are out there listening. Squid counts the number of replies that arrive within a certain amount of time. That amount of time is given by the mcast_icp_query_timeout directive. Then, when Squid sends a real ICP query to the group, it adds this count to the number of ICP replies to expect.

Multicast ICP example

Since multicast ICP is tricky, here’s another example. Let’s say your ISP has three parent caches that listen on a multicast address for ICP queries. The ISP needs only one line in its configuration file:

mcast_groups 224.0.14.255

The configuration for you (the child cache) is a little more complicated. First, you must list the multicast neighbor to which Squid should send queries. You must also list the three parent caches with their unicast addresses so that Squid accepts their replies:

cache_peer 224.0.14.225 multicast 3128 3130 ttl=16 cache_peer parent1.yourisp.net parent 3128 3130 multicast-responder cache_peer parent2.yourisp.net parent 3128 3130 multicast-responder cache_peer parent3.yourisp.net parent 3128 3130 multicast-responder mcast_icp_query_timeout 2 sec

Keep in mind that Squid never makes HTTP requests to multicast neighbors, and it never sends

ICP queries to multicast-responder neighbors.

Cache Digests

One of the most common complaints about ICP is the additional delay added for each request. In many cases, Squid waits for all ICP replies to arrive before making a forwarding decision. Squid’s Cache Digest feature offers similar functionality but without per-request network delays.

Cache Digests are based on a technique first published by Pei Cao, called Summary Cache. The fundamental idea is to use a Bloom filter to represent the cache contents. Neighboring caches download each other’s Bloom filters, or digests in this terminology. Then, they can query the digest to determine whether or not a particular URI is in the neighbor’s cache.

Compared to ICP, Cache Digests trade time for space. Whereas ICP queries incur time penalties (latency), digests incur space (memory, disk) penalties. In Squid, a neighbor’s digest is stored entirely in memory. A typical digest requires about 625 KB of memory for every million objects.

The Bloom filter is an interesting data structure that provides lossy encoding of a collection of items. The filter itself is simply a large array of bits. Given a Bloom filter (and the parameters used to generate it), you can find, with some uncertainty, if a particular item is in the collection. In Squid, items are URIs, and the digest is sized at 5 bits per cached object. For example, you can represent the collection of 1,000,000 cached objects with a filter of 5,000,000 bits, or 625,000 bytes.

Due to their nature, Bloom filters aren’t a perfect representation of the collection. They sometimes incorrectly indicate that a particular item is present in the collection because two or more items may turn on the same bit. In other words, the filter can indicate that object X is in the cache, even though X was never cached or requested. These false positives occur with a certain probability you can control by adjusting the parameters of the filter. For example, increasing the number of bits per object decreases the false positive probability. See my O’Reilly book, Web Caching, for many more details about Cache Digests.

Configuring Squid for Cache Digests

First of all, you must compile Squid with the Cache Digest code enabled. Simply add the

—enable-cache-digests option when running ./configure. Taking this step causes two

things to happen when you run Squid:

Your Squid cache generates a digest of its own contents. Your neighbors may request this digest if they are also configured to use Cache Digests.

Your Squid requests a Cache Digest from each of its neighbors.

If you don’t want to request digests for a particular neighbor,

use the no-digest option on the

cache_peer line. For example:

cache_peer neighbor.host.name parent 3128 3130 no-digest

Squid stores its own digest under the following URL:

http://my.host.name:port/squid-internal-periodic/store_digest.

When Squid requests a neighbor’s digest, it simply requests

http://neighbor.host.name:port/squid-internal-periodic/store_digest.

Obviously, this naming scheme is specific to Squid. If you have a

non-Squid neighbor that supports Cache Digests, you may need to tell

your Squid that the neighbor’s digest has a different address. The

digest-url=url option to

cache_peer allows you to configure the URL for

the neighbor’s Cache Digest. For example:

cache_peer neighbor.host.name parent 3128 3130 digest-url=http://blah/digest

squid.conf has a number of directives that control the way in which Squid generates its own Cache Digest. First, the digest_generation directive controls whether or not Squid generates a digest of its cache. You might want to disable digest generation if your cache is a child to a parent, but not a parent or sibling to any other caches. The remaining directives control low-level underlying details of digest generation. You should change them only if you fully understand the Cache Digest implementation.

The digest_bits_per_entry determines the size of the digest. The default value is 5. Increasing the value results in larger digests (consuming more memory and bandwidth) and lower false-hit probabilities. A lower setting results in smaller digests and more false hits. I feel that the default setting is a very nice tradeoff. A setting of 3 or lower has too many false hits to be useful, and a setting of 8 or higher simply wastes bandwidth.

Squid uses a two-step process to create a cache digest. First, it builds the cache digest data structure. This is basically a large Bloom filter and small header that contains the digest parameters. Once the data structure is filled, Squid creates a cached HTTP response for the digest. This simply involves prepending some HTTP headers and storing the response on disk with the other cached responses.

A Cache Digest represents a snapshot in time of the cache’s contents. The digest_rebuild_period controls how frequently Squid rebuilds the digest data structure (but not the HTTP response). The default is once per hour. More frequent rebuilds mean Squid’s digest is more up to date, at the expense of higher CPU utilization. The rebuild procedure is relatively CPU-intensive. Your users may experience a slowdown while Squid rebuilds its digest.

The digest_rebuild_chunk_percentage directive controls how much of the cache to add to the digest each time the rebuild procedure is called. The default is 10%. During each invocation of the rebuild function, Squid adds some percentage of the cache to the digest. Squid doesn’t process user requests while this function runs. After adding the specified percentage, the function reschedules itself and then exits so that Squid can process normal HTTP requests. After processing pending requests, Squid returns to the rebuild function and adds another chunk of the cache to the digest. Decreasing this value should give better response time to your users, while increasing the total time needed to rebuild the digest.

The digest_rewrite_period directive controls how often Squid creates an HTTP response from the digest data structure. In most cases, this should match the digest_rebuild_period value. The default is one hour. The rewrite procedure consists of numerous calls to a function that simply appends some amount of the digest data structure to the cache entry (as though Squid were reading an origin server response from the network). Each time this function is called, Squid appends digest_swapout_chunk_size bytes of the digest.

Hypertext Caching Protocol

HTCP and ICP have many common characteristics, although HTCP is broader in scope and generally more complex. Both use UDP for transport, and both are per-request protocols. However, HTCP addresses a number of problems with ICP, namely:

An ICP query contains only a URI, without even a request method. HTCP queries contain full HTTP request headers.

ICP provides no security. HTCP has optional message authentication via shared secret keys, although it isn’t yet implemented in Squid. Neither protocol supports encrypted messages.

ICP uses a simple, fixed-sized binary message format that is difficult to extend. HTCP uses a complex, variable-sized binary message format.

HTCP supports four basic opcodes:

- TST

Tests for the presence of a cached response

- SET

Tells a neighbor to update cached object headers

- CLR

Tells a neighbor to remove an object from its cache

- MON

Monitors a neighbor cache’s activity

In Squid, only the TST opcode is currently implemented. This book won’t cover the others.

The primary advantage of using HTCP over ICP is fewer false hits.

HTCP has fewer false hits because the query messages include full HTTP

request headers, including any Cache-Control requirements from the client.

The primary disadvantages are that HTCP queries are larger, and they

require additional CPU processing to generate and parse. Measurements

indicate that HTCP queries are about six times larger than ICP queries,

due to the presence of HTTP request headers. However, Squid’s HTCP

replies are typically smaller than ICP replies.

HTCP is documented as an experimental protocol in RFC 2756. For more information about the message format, see the RFC at http://www.htcp.org or my O’Reilly book, WebCaching.

Configuring Squid for HTCP

To use HTCP, you must configure Squid with the —enable-htcp

option. With this option enabled, Squid becomes an HTCP server by

default. The htcp_port specifies the HTCP port

number, which defaults to 4827. Setting the port to 0 disables the

HTCP server mode.

To become an HTCP client, you need to add the htcp option to a

cache_peer line. When you add this option, Squid

always sends HTCP messages, instead of ICP, to the neighbor. You can’t

use both HTCP and ICP with a single neighbor. The ICP port number

field actually becomes an HTCP port number, so you need to change that

as well. For example, let’s say you want to convert an ICP neighbor to

HTCP. Here’s the neighbor configured for ICP:

cache_peer neighbor.host.name parent 3128 3130

To switch over to HTCP, the line becomes:

cache_peer neighbor.host.name parent 3128 4827 htcp

Sometimes people forget to change the port number, and they end up sending HTCP messages to the ICP port. When this happens, Squid writes warnings to cache.log:

2003/09/29 02:28:55| WARNING: Unused ICP version 23 received from 64.216.111.20:4827

Squid doesn’t currently log HTCP queries as it does for ICP

queries. HTCP queries aren’t tracked in the client_list page either. However, when you

enable HTCP for a peer, the cache manager server_list page (see Section 14.2.1.50) shows the

count and percentage of HTCP replies that were hits and misses:

Histogram of PINGS ACKED:

Misses 5085 98%

Hits 92 2%Note that none of the current Squid versions support HTCP authentication yet.

Cache Array Routing Protocol

CARP is an algorithm that partitions URI-space among a group of caching proxies. In other words, each URI is assigned to one of the caches. CARP maximizes hit ratios and minimizes duplication of objects among the group of caches. The protocol consists of two major components: a Routing Function and a Proxy Array Membership Table. Unlike ICP, HTCP, and Cache Digests, CARP can’t predict whether a particular request will be a cache hit. Thus, you can’t use CARP with siblings—only parents.

The basic idea behind CARP is that you have a group, or array, of parent caches to handle all the load from users or child caches. A cache array is one way to handle ever-increasing loads. You can add more array members whenever you need more capacity. CARP is a deterministic algorithm. That is, the same request always goes to the same array member (as long as the array size doesn’t change). Unlike ICP and HTCP, CARP doesn’t use query messages.

Another interesting thing about CARP is that you have the choice to deploy it in a number of different places. For example, one approach is to make all user-agents execute the CARP algorithm. You could probably accomplish this with a Proxy Auto-Configuration (PAC) function, written in JavaScript (see Appendix F). However, you’re likely to have certain web agents on your network that don’t implement or support PAC files. Another option is to use a two-level cache hierarchy. The lower level (child caches) accept requests from all user-agents, and they execute the CARP algorithm to select the parent cache for each request. However, unless your network is very large, many caches can be more of a burden than a benefit. Finally, you can also implement CARP within the array itself. That is, user-agents connect to a random member of the cache array, but each member forwards cache misses to another member of the array based on the CARP algorithm.

CARP was designed to be better than a simple hashing algorithm, which typically works by applying a hash function, such as MD5, to URIs. The algorithm then calculates the modulus for the number of array members. It might be as simple as this pseudocode:

N = MD5(URI) % num_caches; next_hop = Caches[N];

This technique uniformly spreads the URIs among all the caches. It also provides a consistent mapping (maximizing cache hits), as long as the number of caches remains constant. When caches are added or removed, however, this algorithm changes the mapping for most of the URIs.

CARP’s Routing Function improves on this technique in two ways. First, it allows for unequal sharing of the load. For example, you can configure one parent to receive twice as many requests as another. Second, adding or removing array members minimizes the fraction of URIs that get reassigned.

The downside to CARP is that it is relatively CPU-intensive. For each request, Squid calculates a “score” for each parent. The request is sent to the parent cache with the highest score. The complexity of the algorithm is proportional to the number of parents. In other words, CPU load increases in proportion to the number of CARP parents. However, the calculations in CARP have been designed to be faster than, say, MD5, and other cryptographic hash functions.

In addition to the load-sharing algorithm, CARP also has a protocol component. The Membership Table has a well-defined structure and syntax so that all clients of a single array can have the same configuration. If some clients are configured differently, CARP becomes less useful because not all clients send the same request to the same parent. Note that Squid doesn’t currently implement the Membership Table feature.

Squid’s CARP implementation is lacking in another way. The protocol says that if a request can’t be forwarded to the highest-scoring parent cache, it should be sent to the second-highest-scoring member. If that also fails, the application should give up. Squid currently uses only the highest-scoring parent cache.

CARP was originally documented as an Internet Draft in 1998, which is now expired. It was developed by Vinod Valloppillil of Microsoft and Keith W. Ross of the University of Pennsylvania. With a little searching, you can still find the old document out there on the Internet. You may even be able to find some documentation on the Microsoft sites. You can also find more information on CARP in my O’Reilly book Web Caching.

Configuring Squid for CARP

To use CARP in Squid, you must first run the ./configure script with the

—enable-carp option. Next, you must add carp-load-factor options to the

cache_peer lines for parents that are members of

the array. The following is an example.

cache_peer neighbor1.host.name parent 3128 0 carp-load-factor=0.3 cache_peer neighbor2.host.name parent 3128 0 carp-load-factor=0.3 cache_peer neighbor3.host.name parent 3128 0 carp-load-factor=0.4

Note that all carp-load-factor values must add up to 1.0.

Squid checks for this condition and complains if it finds a

discrepancy. Additionally, the cache_peer lines

must be listed in order of increasing load factor values. Only recent

versions of Squid check that this condition is true.

Remember that CARP is treated somewhat specially with regard to a neighbor’s alive/dead state. Squid normally declares a neighbor dead (and ceases sending requests to it) after 10 failed connections. In the case of CARP, however, Squid skips a parent that has one or more failed connections. Once Squid is working with CARP, you can monitor it with the carp cache manager page. See Section 14.2.1.49 for more information.

Putting It All Together

As you probably realize by now, Squid has many different ways to decide how and where requests are forwarded. In many cases, you can employ more than one protocol or technique at a time. Just by looking at the configuration file, however, you’d probably have a hard time figuring out how Squid uses the different techniques in combination. In this section I’ll explain how Squid actually makes the forwarding decision.

Obviously, it all starts with a cache miss. Any request that is satisfied as an unvalidated cache hit doesn’t go through the following sequence of events.

The goal of the selection procedure is to create a list of appropriate next-hop locations. A next-hop location may be a neighbor cache or the origin server. Depending on your configuration, Squid may select up to three possible next-hops. If the request can’t be satisfied by the first, Squid tries the second, and so on.

Step 1: Determine Direct Options

The first step is to determine if the request may, must, or must not be sent directly to

the origin server. Squid evaluates the

never_direct and

always_direct access rule lists for the request.

The goal is to set a flag to one of three values: DIRECT_YES,

DIRECT_MAYBE, or DIRECT_NO. This flag later determines whether Squid

should, or should not, try to select a neighbor cache for the request.

Squid checks the following conditions in order. If any condition is

true, it sets the direct flag and proceeds to the next step. If you’re

following along in the source code, this step corresponds to the

beginning of the peerSelectFoo( ) function:

Squid looks at the always_direct list first. If the request matches this list, the direct flag is set to DIRECT_YES.

Squid looks at the never_direct list next. If the request matches this list, the direct flag is set to DIRECT_NO.

Squid has a special check for requests that appear to be looping. When Squid detects a forwarding loop, it sets the direct flag to DIRECT_YES to break the loop.

Squid checks the minimum_direct_hops and minimum_direct_rtt settings, but only if you’ve enabled netdb. If the measured hop count or round-trip time is lower than the configured values, Squid sets the direct flag to DIRECT_YES.

If none of the previous conditions are true, Squid sets the direct flag to DIRECT_MAYBE.

If the direct flag is set to DIRECT_YES, the selection process is complete. Squid forwards the request directly to the origin server and skips the remaining steps in this section.

Step 2: Neighbor Selection Protocols

Here Squid uses one of the hierarchical protocols to select a neighbor cache. As

before, once Squid selects a neighbor in this step, it exits the

routine and proceeds to Step 3. This step roughly corresponds to the

peerGetSomeNeighbor( ) function:

Squid examines the neighbor’s Cache Digests. If it indicates a hit, that neighbor is placed on the next-hop list.

Squid tries CARP if enabled. CARP always succeeds (i.e., selects a parent), unless the cache_peer_access or cache_peer_domain rules forbid communication with any of the parent caches for a particular request.

Squid checks netdb measurements (if enabled) for a “closest parent.” If Squid knows that the round-trip time from one or more parents to the origin server is less than its own RTT to the origin server, Squid selects the parent with the least RTT. For this to happen, the following conditions must be met:

Both your Squid and the parent cache(s) must have enabled netdb measurements.

query_icmp must be enabled in your configuration file.

The origin server must respond to ICMP pings.

The parent(s) must have previously measured the RTT to the origin server and returned those measurements in ICP/HTCP replies, or through a netdb exchange.

Squid sends ICP/HTCP queries as the last resort. Squid loops through all neighbors and checks a number of conditions. Squid doesn’t query a neighbor if:

The direct flag is DIRECT_MAYBE and the request is nonhierarchical (see Section 10.4.5). Because Squid is allowed to go directly to the origin server, it doesn’t bother the neighbor with this request, which is likely to be uncachable.

The direct flag is DIRECT_NO, the neighbor is a sibling, and the request is nonhierarchical. Because Squid is forced to use a neighbor, it only queries parents, which can always handle a cache miss.

The cache_peer_access or cache_peer_domain rules forbid sending this request to the neighbor.

The neighbor’s

no-queryflag is set, or its ICP/HTCP port number is zero.The neighbor is a multicast responder.

Squid counts how many queries it sends and calculates how many replies to expect. If it expects at least one reply, the rest of the next-hop selection procedure is postponed until the replies arrive, or a timeout occurs. Squid expects to receive replies from neighbors that are alive, but not neighbors that are dead (see Section 10.3.2).

Step 2a: ICP/HTCP Reply Processing

If Squid sends out any ICP or HTCP queries, it waits for some number of replies. Just after transmitting the queries, Squid knows how many replies to expect and the maximum amount of time to wait for them. Squid expects a reply from every alive neighbor queried. If you’re using multicast, Squid adds the current group size estimate to the expected reply count. While waiting for replies, Squid schedules a timeout, in case one or more of the replies don’t arrive.

When Squid receives an ICP/HTCP reply from a neighbor, it takes the following actions:

If the reply is a hit, Squid forwards the request to that neighbor immediately. Any replies arriving after this point are ignored.

If the reply is a miss, and it is from a sibling, it is ignored.

Squid doesn’t immediately act on ICP/HTCP misses from parents. Instead, it remembers which parents meet the following criteria:

- The closest-parent miss

If the reply includes a netdb RTT measurement, Squid remembers the parent that has the least RTT to the origin server.

- The first-parent miss

Squid remembers the parent that had the first reply. In other words, the parent with least RTT to your cache. Two cache_peer options affect this part of the algorithm:

weight=Nandclosest-only.The

weight=Noption makes a parent closer than it really is. When calculating RTTs, Squid divides the actual RTT by this artificial weight. Thus you can give higher preference to certain parents by increasing their weight value.The

closest-onlyoption disables the first-parent miss feature for a neighbor cache. In other words, Squid selects a parent (based on ICP/HTCP miss replies) only if that parent is the closest to the origin server.

If Squid receives the expected number of replies (all misses), or if the timeout occurs, it selects the closest-parent miss neighbor if set. Otherwise, it selects the first-parent miss neighbor if set.

Squid may not receive any ICP/HTCP replies from parent caches, either because they weren’t queried or because the network dropped some packets. In this case, Squid relies on the secondary parent (or direct) selection algorithm described in the next section.

If the ICP/HTCP query timeout occurs before receiving the

expected number of replies, Squid prepends the string TIMEOUT_ to the result code in access.log.

Step 3: Secondary Parent Selection

This step is a little tricky. Remember that if the direct flag

is DIRECT_YES, Squid never executes this step. If the flag is

DIRECT_NO, Squid calls the getSomeParent( ) function (described

subsequently) to select a backup parent, in case Step 2 failed to select

one. Following that, Squid adds to the list all parents it believes

are alive. Thus, it tries all possible parent caches before returning

an error message to the user.

In the case of DIRECT_MAYBE, Squid adds both a parent cache, and

the origin server. The order, however, depends on the

prefer_direct setting. If

prefer_direct is enabled, Squid inserts the

origin server into the list first. Next, Squid calls getSomeParent( ) if the request is hierarchical

or if the nonhierarchical_direct directive is

disabled. Finally, Squid adds the origin server last if

prefer_direct is disabled.

The getSomeParent( ) function selects one of the

parents based on the following criteria. In each case, the parent must

be alive and allowed to handle the request according to the

cache_peer_access and

cache_peer_domain rules:

The first parent with the

defaultcache_peer optionThe parent with the

round-robincache_peer option that has the lowest request countThe first parent that is known to be alive

Retrying

Occasionally, Squid’s attempt to forward a request to an origin server or neighbor may fail for one reason or another. This is why Squid creates a list of appropriate next-hop locations during the neighbor selection procedure. When one of the following types of errors occurs, Squid can retry the request at the next server in the list:

Network congestion or other errors can cause a “connection timeout.”

The origin server or neighbor cache may be temporarily unavailable, causing a “connection refused” error.

A sibling may return a 504 (Gateway Timeout) error if the request would cause a cache miss.

A neighbor may return an “access denied” error message if the two caches have a mismatch in access control policies.

A read error may occur on an established connection before Squid reads the HTTP message body.

There may be race conditions with persistent connections.

Squid’s algorithm for retrying failed requests is relatively aggressive. It is better for Squid to keep trying (causing some extra delay), rather than return an error to the user.

How Do I ...

New Squid users often ask the same, or similar, questions about getting Squid to forward requests in the right way. Here I’ll show you how to configure Squid for some common scenarios.

Send All Requests Through Another Proxy?

You simply need to define a parent and tell Squid it isn’t allowed to connect directly to origin servers. For example:

cache_peer parent.host.name parent 3128 0 acl All src 0/0 never_direct allow All

The drawback to this configuration is that Squid can’t forward cache misses if the parent goes down. If that happens, your users receive the “cannot forward” error message.

Send All Requests Through Another Proxy Unless It’s Down?

nonhierarchical_direct off prefer_direct off cache_peer parent.host.name parent 3128 0 default no-query

Or, if you’d like to use ICP with the other proxy:

nonhierarchical_direct off prefer_direct off cache_peer parent.host.name parent 3128 3130 default

With this configuration, Squid forwards all cache misses to the parent as long as it is alive. Using ICP should cause Squid to detect a dead parent quickly, but at the same time may incorrectly declare the parent dead on occasion.

Make Sure Squid Doesn’t Use Neighbors for Some Requests?

Define an ACL to match the special request:

cache_peer parent.host.name parent 3128 0 acl Special dstdomain special.server.name always_direct allow Special

In this case, cache misses for requests in the special.server.name domain are always sent to the origin server. Other requests may, or may not, go through the parent cache.

Send Some Requests Through a Parent to Bypass Local Filters?

Some ISPs (and other organizations) have upstream providers that force HTTP traffic through a filtering proxy (perhaps with HTTP interception). You might be able to get around their filters if you can use a different proxy beyond their network. Here’s how you can send only special requests to the far-away proxy:

cache_peer far-away-parent.host.name parent 3128 0 acl BlockedSites dstdomain www.censored.com cache_peer_access far-away-parent.host.name allow BlockedSites never_direct allow BlockedSites

Exercises

Toggle your prefer_direct and/or nonhierarchical_direct settings and look for any changes in the access.log.

Enable netdb and view the netdb cache manager page after Squid has been running for a while.

If using ICP or HTCP, count the percentage of requests that experienced a timeout waiting for replies to arrive.

If you used

—enable-cache-digestsand have a reasonably full cache, disable the digest_generation directive and note any change in memory usage.Use your operating system’s packet filters to block ICP or HTCP messages to your neighbors. How quickly does Squid change their state from alive to dead, and back again?

[1] For more information, see the following papers: “A Hierarchical Internet Object Cache,” by Danzig, Chankhunthod, et al, USENIX Annual Technical Conference, 1995, and “The Harvest information discovery and access system,” by C. Mic Bowman, Peter B. Danzig, Darren R. Hardy, Udi Manber, and Michael F. Schwartz, Proceedings of the Second International World Wide Web Conference.