Chapter 6. All About Access Controls

Access controls are the most important part of your Squid configuration file. You’ll use them to grant access to your authorized users and to keep out the bad guys. You can use them to restrict, or prevent access to, certain material; to control request rewriting; to route requests through a hierarchy; and to support different qualities of service.

Access controls are built from two different components. First, you define a number of access control list (ACL) elements. These elements refer to specific aspects of client requests, such as IP addresses, URL hostnames, request methods, and origin server port numbers. After defining the necessary elements, you combine them into a number of access list rules. The rules apply to particular services or operations within Squid. For example, the http_access rules are applied to incoming HTTP requests. I cover the access control elements first, and then the rules later in this chapter.

Access Control Elements

ACL elements are the building blocks of Squid’s access control implementation. These are how you specify things such as IP addresses, port numbers, hostnames, and URL patterns. Each ACL element has a name, which you refer to when writing the access list rules. The basic syntax of an ACL element is as follows:

acl name type value1 value2 ...For example:

acl Workstations src 10.0.0.0/16

In most cases, you can list multiple values for one ACL element. You can also have

multiple acl lines with the same

name. For example, the following two configurations are

equivalent:

acl Http_ports port 80 8000 8080 acl Http_ports port 80 acl Http_ports port 8000 acl Http_ports port 8080

A Few Base ACL Types

Squid has approximately 25 different ACL types, some of which have a common base type. For example, both src and dst ACLs use IP addresses as their base type. To avoid being redundant, I’ll cover the base types first and then describe each type of ACL in the following sections.

IP addresses

Used by: src, dst, myip

Squid has a powerful syntax for specifying IP addresses in ACLs. You can write addresses as subnets, address ranges, and domain names. Squid supports both “dotted quad” and CIDR prefix[1] subnet specifications. In addition, if you omit a netmask, Squid calculates the appropriate netmask for you. For example, each group in the next example are equivalent:

acl Foo src 172.16.44.21/255.255.255.255 acl Foo src 172.16.44.21/32 acl Foo src 172.16.44.21 acl Xyz src 172.16.55.32/255.255.255.248 acl Xyz src 172.16.55.32/28 acl Bar src 172.16.66.0/255.255.255.0 acl Bar src 172.16.66.0/24 acl Bar src 172.16.66.0

When you specify a netmask, Squid checks your work. If your netmask masks out non-zero bits of the IP address, Squid issues a warning. For example, the following lines results in the subsequent warning:

acl Foo src 127.0.0.1/8 aclParseIpData: WARNING: Netmask masks away part of the specified IP in 'Foo'

The problem here is that the /8 netmask (255.0.0.0) has all zeros in the last three octets, but the IP address 127.0.0.1 doesn’t. Squid warns you about the problem so you can eliminate the ambiguity. To be correct, you should write:

acl Foo src 127.0.0.1/32

or:

acl Foo src 127.0.0.0/8

Sometimes you may need to list multiple, contiguous subnets. In these cases, it may be easier to specify an address range. For example:

acl Bar src 172.16.10.0-172.16.19.0/24

This is equivalent to, and more efficient than, this approach:

acl Foo src 172.16.10.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.11.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.12.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.13.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.14.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.15.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.16.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.18.0/24 acl Foo src 172.16.19.0/24

Note that with IP address ranges, the netmask goes only at the very end. You can’t specify different netmasks for the beginning and ending range values.

You can also specify hostnames in IP ACLs. For example:

acl Squid dst www.squid-cache.org

Tip

Squid converts hostnames to IP addresses at startup. Once started, Squid never makes another DNS lookup for the hostname’s address. Thus, Squid never notices if the address changes while it’s running.

If the hostname resolves to multiple addresses, Squid adds each to the ACL. Also note that you can’t use netmasks with hostnames.

Using hostnames in address-based ACLs is usually a bad idea.

Squid parses the configuration file before initializing other

components, so these DNS lookups don’t use Squid’s nonblocking IP

cache interface. Instead, they use the blocking gethostbyname( ) function. Thus, the need to

convert ACL hostnames to addresses can delay Squid’s startup

procedure. Avoid using hostnames in src,

dst, and myip ACLs unless

absolutely necessary.

Squid stores IP address ACLs in memory with a data structure known as an splay tree (see http://www.link.cs.cmu.edu/splay/). The splay tree has some interesting self-organizing properties, one of which being that the list automatically adjusts itself as lookups occur. When a matching element is found in the list, that element becomes the new root of the tree. In this way frequently referenced items migrate to the top of the tree, which reduces the time for future lookups.

All subnets and ranges belonging to a single ACL element must not overlap. Squid warns you if you make a mistake. For example, this isn’t allowed:

acl Foo src 1.2.3.0/24 acl Foo src 1.2.3.4/32

It causes Squid to print a warning in cache.log:

WARNING: '1.2.3.4' is a subnetwork of '1.2.3.0/255.255.255.0'

WARNING: because of this '1.2.3.4' is ignored to keep splay tree searching

predictable

WARNING: You should probably remove '1.2.3.4' from the ACL named 'Foo'In this case, you need to fix the problem, either by removing one of the ACL values or by placing them into different ACL lists.

Domain names

Used by: srcdomain, dstdomain, and the cache_host_domain directive

A domain name is simply a DNS name or zone. For example, the following are all valid domain names:

www.squid-cache.org squid-cache.org org

Domain name ACLs are tricky because of a subtle difference relating to matching domain names and subdomains. When the ACL domain name begins with a period, Squid treats it as a wildcard, and it matches any hostname in that domain, even the domain name itself. If, on the other hand, the ACL domain name doesn’t begin with a period, Squid uses exact string comparison, and the hostname must be exactly the same for a match.

Table 6-1 shows Squid’s rules for matching domain and hostnames. The first column shows hostnames taken from requested URLs (or client hostnames for srcdomain ACLs). The second column indicates whether or not the hostname matches lrrr.org. The third column shows whether the hostname matches an .lrrr.org ACL. As you can see, the only difference is in the second case.

URL hostname | Matches ACL lrrr.org? | Matches ACL .lrrr.org? |

lrrr.org | Yes | Yes |

i.am.lrrr.org | No | Yes |

iamlrrr.org | No | No |

Domain name matching can be confusing, so let’s look at another example so that you really understand it. Here are two slightly different ACLs:

acl A dstdomain foo.com acl B dstdomain .foo.com

A user’s request to get http://www.foo.com/ matches ACL B, but not A. ACL A requires an exact string match, but the

leading dot in ACL B is like a

wildcard.

On the other hand, a user’s request to get

http://foo.com/ matches both ACLs A and B. Even though there is no word before

foo.com in the URL hostname, the leading dot in

ACL B still causes a

match.

Squid uses splay trees to store domain name ACLs, just as it does for IP addresses. However, Squid’s domain name matching algorithm presents an interesting problem for splay trees. The splay tree technique requires that only one key can match any particular search term. For example, let’s say the search term (from a URL) is i.am.lrrr.org. This hostname would be a match for both .lrrr.org and .am.lrrr.org. The fact that two ACL values match one hostname confuses the splay algorithm. In other words, it is a mistake to put something like this in your configuration file:

acl Foo dstdomain .lrrr.org .am.lrrr.org

If you do, Squid generates the following warning message:

WARNING: '.am.lrrr.org' is a subdomain of '.lrrr.org' WARNING: because of this '.am.lrrr.org' is ignored to keep splay tree searching predictable WARNING: You should probably remove '.am.lrrr.org' from the ACL named 'Foo'

You should follow Squid’s advice in this case. Remove one of the related domains so that Squid does exactly what you intend. Note that you can use both domain names as long as you put them in different ACLs:

acl Foo dstdomain .lrrr.org acl Bar dstdomain .am.lrrr.org

This is allowed because each named ACL uses its own splay tree.

Usernames

Used by: ident, proxy_auth

ACLs of this type are designed to match usernames. Squid may learn a username through

the RFC 1413 ident protocol or via HTTP authentication headers.

Usernames must be matched exactly. For example, bob doesn’t match bobby. Squid also has related ACLs

(ident_regex and

proxy_auth_regex) that use regular-expression

pattern matching on usernames.

You can use the word REQUIRED as a special value to match any

username. If Squid can’t determine the username, the ACL isn’t

matched. This is how Squid is usually configured when using

username-based access controls.

Regular expressions

Used by: srcdom_regex, dstdom_regex, url_regex, urlpath_regex, browser, referer_regex, ident_regex, proxy_auth_regex, req_mime_type, rep_mime_type

A number of ACLs use regular expressions

(regex) to match character strings. (For a complete

regular-expression reference, see O’Reilly’s Mastering

Regular Expressions.) For Squid, the most commonly used

regex features match the beginning and/or end of a string. For

example, the ^ character is

special because it matches the beginning of a line or string:

^http://

This regex matches any URL that begins with http://. The $ character is also special because it

matches the end of a line or string:

.jpg$

Actually, the previous example is slightly wrong because the . character is special too. It is a wildcard that matches any character. What we really want is this:

\.jpg$

The backslash escapes the . so that its specialness is taken

away. This regex matches any string that ends with .jpg. If you don’t use the ^ or $

characters, regular expressions behave like standard substring

searches. They match an occurrence of the word (or words) anywhere

in the string.

With all of Squid’s regex types, you have the option to use

case-insensitive comparison. Matching is case-sensitive by default.

To make it case-insensitive, use the -i option

after the ACL type. For example:

acl Foo url_regex -i ^http://www

TCP port numbers

Used by: port, myport

This type is relatively straightforward. The values are individual port numbers or port number ranges. Recall that TCP port numbers are 16-bit values and, therefore, must be greater than 0 and less than 65,536. Here are some examples:

acl Foo port 123 acl Bar port 1-1024

Autonomous system numbers

Used by: src_as, dst_as

Internet routers use Autonomous System (AS) numbers to construct routing tables. Essentially, an AS number refers to a collection of IP networks managed by a single organization. For example, my ISP has been assigned the following network blocks: 134.116.0.0/16, 137.41.0.0/16, 206.168.0.0/16, and many more. In the Internet routing tables, these networks are advertised as belonging to AS 3404. When routers forward packets, they typically select the path that traverses the fewest autonomous systems. If none of this makes sense to you, don’t worry. AS-based ACLs should only be used by networking gurus.

Here’s how the AS-based types work: when Squid first starts up, it sends a special query to a whois server. The query essentially says, “Tell me which IP networks belong to this AS number.” This information is collected and managed by the Routing Arbiter Database (RADB). Once Squid receives the list of IP networks, it treats them similarly to the IP address-based ACLs.

AS-based types only work well when ISPs keep their RADB information up to date. Some ISPs are better than others about updating their RADB entries; many don’t bother with it at all. Also note that Squid converts AS numbers to networks only at startup or when you signal it to reconfigure. If the ISP updates its RADB entry, your cache won’t know about the changes until you restart or reconfigure Squid.

Another problem is that the RADB server may be unreachable when your Squid process starts. If Squid can’t contact the RADB server, it removes the AS entries from the access control configuration. The default server, whois.ra.net, may be too far away from many users to be reliable.

ACL Types

Now we can focus on the ACL types themselves. I present them here roughly in order of decreasing importance.

src

IP addresses are the most commonly used access control elements. Most sites use IP address controls to specify clients that are allowed to access Squid and those that aren’t. The src type refers to client (source) IP addresses. That is, when an src ACL appears in an access list, Squid compares it to the IP address of the client issuing the request.

Normally you want to allow requests from hosts inside your network and block all others. For example, if your organization is using the 192.168.0.0 subnet, you can use an ACL like this:

acl MyNetwork src 192.168.0.0

If you have many subnets, you can list them all on the same acl line:

acl MyNetwork src 192.168.0.0 10.0.1.0/24 10.0.5.0/24 172.16.0.0/12

Squid has a number of other ACL types that check the client’s address. The srcdomain type compares the client’s fully qualified domain name. It requires a reverse DNS lookup, which may add some delay to processing the request. The srcdom_regex ACL is similar, but it allows you to use a regular expression to compare domain names. Finally, the src_as type compares the client’s AS number.

dst

The dst type refers to origin server (destination) IP addresses. Among other things, you can use this to prevent some or all of your users from visiting certain web sites. However, you need to be a little careful with the dst ACL. Most of the requests received by Squid have origin server hostnames. For example:

GET http://www.web-cache.com/ HTTP/1.0

Here, www.web-cache.com is the hostname. When an access list rule includes a dst element, Squid must find the IP addresses for the hostname. If Squid’s IP cache contains a valid entry for the hostname, the ACL is checked immediately. Otherwise, Squid postpones request processing while the DNS lookup is in progress. This can add significant delay to some requests. To avoid those delays, you should use the dstdomain ACL type (instead of dst) whenever possible.[2]

Here is a simple dst ACL example:

acl AdServers dst 1.2.3.0/24

Note that one problem with dst ACLs is that the origin server you are trying to allow or deny may change its IP address. If you don’t notice the change, you won’t bother to update squid.conf. You can put a hostname on the acl line, but that adds some delay at startup. If you need many hostnames in ACLs, you may want to preprocess the configuration file and turn the hostnames into IP addresses.

myip

The myip type refers to the IP address where clients connect to Squid. This is what you see under the Local Address column when you run netstat -n on the Squid box. Most Squid installations don’t use this type. Usually, all clients connect to the same IP address, so this ACL element is useful only on systems that have more than one IP address.

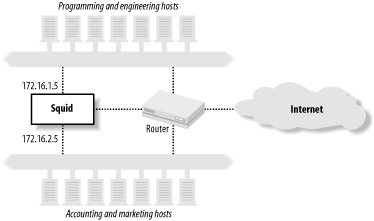

To understand how myip may be useful, consider a simple company local area network with two subnets. All users on subnet-1 are programmers and engineers. Subnet-2 consists of accounting, marketing, and other administrative departments. The system on which Squid runs has three network interfaces: one on subnet-1, one on subnet-2, and the third connecting to the outbound Internet connection (see Figure 6-1).

When properly configured, all users on subnet-1 connect to Squid’s IP address on that subnet, and similarly, all subnet-2 users connect to Squid’s second IP address. You can use this to give the technical staff on subnet-1 full access, while limiting the administrative staff to only work-related web sites.

The ACLs might look like this:

acl Eng myip 172.16.1.5 acl Admin myip 172.16.2.5

Note, however, that with this scheme you must take special measures to prevent users on one subnet from connecting to Squid’s address on the other subnet. Otherwise, clever users on the accounting and marketing subnet can connect through the programming and engineering subnet and bypass your restrictions.

dstdomain

In some cases, you’re likely to find that name-based access controls make a lot of sense. You can use them to block access to certain sites, to control how Squid forwards requests and to make some responses uncachable. The dstdomain type is very useful because it checks the hostname in requested URLs.

First, however, I want to clarify the difference between the following two lines:

acl A dst www.squid-cache.org acl B dstdomain www.squid-cache.org

A is really an IP address

ACL. When Squid parses the configuration file, it looks up the IP

address for www.squid-cache.org and stores the

address in memory. It doesn’t store the name. If the IP address for

www.squid-cache.org changes while Squid is

running, Squid continues using the old address.

The dstdomain ACL, on the other hand, is

stored as a domain name (i.e., a string), not as an IP address. When

Squid checks ACL B, it uses

string comparison functions on the hostname part of the URL. In this

case, it doesn’t really matter if the

www.squid-cache.org IP changes while Squid is

running.

The primary problem with dstdomain ACLs is that some URLs have IP addresses instead of hostnames. If your goal is to block access to certain sites with dstdomain ACLs, savvy users can simply look up the site’s IP address manually and insert it into the URL. For example, these two URLs bring up the same page:

http://www.squid-cache.org/docs/FAQ/ http://206.168.0.9/docs/FAQ/

The first can be easily matched with dstdomain ACLs, but the second can’t. Thus, if you elect to rely on dstdomain ACLs, you may want to also block all requests that use an IP address instead of a hostname. See the Section 6.3.8 for an example.

srcdomain

The srcdomain ACL is somewhat tricky as well. It requires a so-called reverse DNS lookup on each client’s IP address. Technically, Squid requests a DNS PTR record for the address. The answer—a fully qualified domain name (FQDN)—is what Squid compares to the ACL value. (Refer to O’Reilly’s DNS and BIND for more information about DNS PTR records.)

As with dst ACLs, FQDN lookups are a potential source of significant delay. The request is postponed until the FQDN answer comes back. FQDN answers are cached, so the srcdomain lookup delay usually occurs only for the client’s first request.

Unfortunately, srcdomain lookups sometimes don’t work. Many organizations fail to keep their reverse lookup databases current. If an address doesn’t have a PTR record, the ACL check fails. In some cases, requests may be postponed for a very long time (e.g., two minutes) until the DNS lookup times out. If you choose to use the srcdomain ACL, make sure that your own DNS in-addr.arpa zones are properly configured and working. Assuming that they are, you can use an ACL like this:

acl LocalHosts srcdomain .users.example.com

port

Most likely, you’ll want to use the port ACL to limit access to certain origin server port numbers. As I’ll explain shortly, Squid really shouldn’t connect to certain services, such as email and IRC servers. The port ACL allows you to define individual ports, and port ranges. Here is an example:

acl HTTPports port 80 8000-8010 8080

HTTP is similar in design to other protocols, such as SMTP. This means that clever users can trick Squid into relaying email messages to an SMTP server. Email relays are one of the primary reasons we must deal with a daily deluge of spam. Historically, spam relays have been actual mail servers. Recently, however, more and more spammers are using open HTTP proxies to hide their tracks. You definitely don’t want your Squid cache to be used as a spam relay. If it is, your IP address is likely to end up on one of the many mail-relay blacklists (MAPS, ORDB, spamhaus, etc.). In addition to email, there are a number of other TCP/IP services that Squid shouldn’t normally communicate with. These include IRC, Telnet, DNS, POP, and NNTP. Your policy regarding port numbers should be either to deny the known-to-be-dangerous ports and allow the rest, or to allow the known-to-be-safe ports and deny the rest.

My preference is to be conservative and allow only the safe

ports. The default squid.conf

includes the following Safe_ports

ACL:

acl Safe_ports port 80 # http acl Safe_ports port 21 # ftp acl Safe_ports port 443 563 # https, snews acl Safe_ports port 70 # gopher acl Safe_ports port 210 # wais acl Safe_ports port 1025-65535 # unregistered ports acl Safe_ports port 280 # http-mgmt acl Safe_ports port 488 # gss-http acl Safe_ports port 591 # filemaker acl Safe_ports port 777 # multiling http http_access deny !Safe_ports

This is a sensible approach. It allows users to connect to any

nonprivileged port (1025-65535), but only specific ports in the

privileged range. If one of your users tries to request a URL, such

as http://www.lrrr.org:123/, Squid returns an

access denied error message. In some cases, you may need to add

additional port numbers to the Safe_ports ACL to keep your users

happy.

A more liberal approach is to deny access to certain ports that are known to be particularly dangerous. The Squid FAQ includes an example of this:

acl Dangerous_ports 7 9 19 22 23 25 53 109 110 119 http_access deny Dangerous_ports

One drawback to the Dangerous_ports approach is that Squid ends up searching the entire list for almost every request. This places a little extra burden on your CPU. Most likely, 99% of the requests reaching Squid are for port 80, which doesn’t appear in the Dangerous_ports list. The list is searched for all of these requests without resulting in a match. However, integer comparison is a fast operation and should not significantly impact performance.

myport

Squid also has a myport ACL. Whereas the port ACL refers to the origin server port number, myport refers to the port where Squid receives client requests. Squid listens on different port numbers if you specify more than one with the http_port directive.

The myport ACL is particularly useful if you use Squid as an HTTP accelerator for your web site and as a proxy for your users. You can accept the accelerator requests on port 80 and the proxy requests on port 3128. You probably want the world to access the accelerator, but only your users should access Squid as a proxy. Your ACLs may look something like this:

acl AccelPort myport 80 acl ProxyPort myport 3128 acl MyNet src 172.16.0.0/22 http_access allow AccelPort # anyone http_access allow ProxyPort MyNet # only my users http_access deny ProxyPort # deny others

method

The method ACL refers to the HTTP request

method. GET is

typically the most common method, followed by POST, PUT, and others. This example demonstrates

how to use the method ACL:

acl Uploads method PUT POST

Squid knows about the following standard HTTP methods:

GET, POST, PUT, HEAD, CONNECT, TRACE, OPTIONS, and DELETE. In addition, Squid knows about the

following methods from the WEBDAV specification, RFC 2518: PROPFIND, PROPPATCH, MKCOL, COPY, MOVE, LOCK, UNLOCK.[3] Certain Microsoft products use nonstandard WEBDAV

methods, so Squid knows about them as well: BMOVE, BDELETE, BPROPFIND. Finally, you can configure

Squid to understand additional request methods with the

extension_methods directive. See Appendix A.

Note that the CONNECT

method is special in a number of ways. It is the method used for

tunneling certain requests through HTTP proxies (see also RFC 2817:

Upgrading to TLS Within HTTP/1.1). Be especially careful with the

CONNECT method and remote server

port numbers. As I talked about in the previous section, you don’t

want Squid to connect to certain remote services. You should limit

the CONNECT method to only the

HTTPS/SSL and perhaps NNTPS ports (443 and 563, respectively). The

default squid.conf does

this:

acl CONNECT method CONNECT acl SSL_ports 443 563 http_access allow CONNECT SSL_ports http_access deny CONNECT

With this configuration, Squid only allows tunneled requests

to ports 443 (HTTPS/SSL) and 563 (NNTPS). CONNECT method requests to all other ports

are denied.

PURGE is another special

request method. It is specific to Squid and not defined in any of

the RFCs. It provides a way for the administrator to forcibly remove

cached objects. Since this method is somewhat dangerous, Squid

denies PURGE requests by default,

unless you define an ACL that references the method. Otherwise,

anyone with access to the cache may be able to remove any cached

object. I recommend allowing PURGE from localhost

only:

acl Purge method PURGE acl Localhost src 127.0.0.1 http_access allow Purge Localhost http_access deny Purge

See Section 7.6 for more information on removing objects from Squid’s cache.

proto

This type refers to a URI’s access (or transfer) protocol. Valid values are the following: http, https (same as HTTP/TLS), ftp, gopher, urn, whois, and cache_object. In other words, these are

the URL scheme names (RFC 1738 terminology) supported by Squid. For

example, suppose that you want to deny all FTP requests. You can use

the following directives:

acl FTP proto FTP http_access deny FTP

The cache_object scheme is a feature specific to Squid. It is used to access Squid’s cache management interface, which I’ll talk about in Section 14.2. Unfortunately, it’s not a very good name, and it should probably be changed.

The default squid.conf file has a couple of lines that restrict cache manager access:

acl Manager proto cache_object acl Localhost src 127.0.0.1 http_access allow Manager Localhost http_access deny Manager

These configuration lines allow cache-manager requests only when they come from the localhost address. All other cache-manager requests are denied. This means that any user with an account on the Squid machine can access the potentially sensitive cache-manager information. You may want to modify the cache-manager access controls or protect certain pages with passwords. I’ll talk about that in Section 14.2.2.

time

The time ACL allows you to control access based on the time of day and the day of the week. The syntax is somewhat cryptic:

acl name [days] [h1:m1-h2:m2]You can specify days of the week, starting and stopping times, or both. Days are specified by the single-letter codes shown in Table 6-2. Times are specified in 24-hour format. The starting time must be less than the ending time, which makes it awkward to write time ACLs that span “midnights.”

Code | Day |

S | Sunday |

M | Monday |

T | Tuesday |

W | Wednesday |

H | Thursday |

F | Friday |

A | Saturday |

D | All weekdays (M-F) |

Tip

Days and times are interpreted with the localtime( ) function, which takes into

account your local time zone and daylight savings time settings.

Make sure that your computer knows what time zone it is in! You’ll

also want to make sure that your clock is synchronized to the

correct time.

To specify a time ACL that matches your weekday working hours, you can write:

acl Working_hours MTWHF 08:00-17:00

or:

acl Working_hours D 08:00-17:00

Let’s look at a trickier example. Perhaps you’re an ISP that relaxes access during off-peak hours, say 8 P.M. to 4 A.M. Since this time spans midnight, you can’t write “20:00-04:00.” Instead you’ll need either to split this into two ACLs or define the peak hours and use negation. For example:

acl Offpeak1 20:00-23:59 acl Offpeak2 00:00-04:00 http_access allow Offpeak1 ... http_access allow Offpeak2 ...

Alternatively, you can do it like this:

acl Peak 04:00-20:00 http_access allow !Peak ...

Although Squid allows it, you probably shouldn’t put more than one day list and time range on a single time ACL line. The parser isn’t always smart enough to figure out what you want. For example, if you enter this:

acl Blah time M 08:00-10:00 W 09:00-11:00

what you really end up with is this:

acl Blah time MW 09:00-11:00

The parser ORs weekdays together and uses only the last time range. It does work, however, if you write it like this, on two separate lines:

acl Blah time M 08:00-10:00 acl Blah time W 09:00-11:00

ident

The ident ACL matches usernames returned by the ident protocol. This is a simple protocol, that’s documented in RFC 1413. It works something like this:

A user-agent (client) establishes a TCP connection to Squid.

Squid connects to the ident port (113) on the client’s system.

Squid writes a line containing the two TCP port numbers of the client’s first connection. The Squid-side port number is probably 3128 (or whatever you configured in squid.conf). The client-side port is more or less random.

The client’s ident server writes back the username belonging to the process that opened the first connection.

Squid records the username for access control purposes and for logging in access.log.

When Squid encounters an ident ACL for a particular request, that request is postponed until the ident lookup is complete. Thus, the ident ACL may add some significant delays to your users’ requests.

We recommend using the ident ACL only on local area networks and only if all or most of the client workstations run the ident server. If Squid and the client workstations are connected to a LAN with low latency, the ident ACL can work well. Using ident for clients connecting over WAN links is likely to frustrate both you and your users.

The ident protocol isn’t very secure. Savvy users will be able

to replace their normal ident server with a fake server that returns

any username they select. For example, if I know that connections

from the user administrator are

always allowed, I can write a simple program that answers every

ident request with that username.

Tip

You can’t use ident ACLs with

interception caching (see Chapter

9). When Squid is configured for interception caching, the

operating system pretends that it is the origin server. This means

that the local socket address for intercepted TCP connections has

the origin server’s IP address. If you run netstat -n on Squid, you’ll see a lot of foreign

IP addresses in the Local Address column.

When Squid makes an ident query, it creates a new TCP socket and

binds the local endpoint to the same IP address as the local end

of the client’s TCP connection. Since the local address isn’t

really local (it’s some far away origin server’s IP address), the

bind( ) system call fails.

Squid handles this as a failed ident query.

Note that Squid also has a feature to perform “lazy” ident lookups on clients. In this case, requests aren’t delayed while waiting for the ident query. Squid logs the ident information if it is available by the time the HTTP request is complete. You can enable this feature with the ident_lookup_access directive, which I’ll discuss later in this chapter.

proxy_auth

Squid has a powerful, and somewhat confusing, set of features to support HTTP proxy authentication. With proxy authentication, the client’s HTTP request includes a header containing authentication credentials. Usually, this is simply a username and password. Squid decodes the credential information and then queries an external authentication process to find out if the credentials are valid.

Squid currently supports three techniques for receiving user credentials: the HTTP Basic protocol, Digest authentication protocol, and NTLM. Basic authentication has been around for a long time. By today’s standards, it is a very insecure technique. Usernames and passwords are sent together, essentially in cleartext. Digest authentication is more secure, but also more complicated. Both Basic and Digest authentication are documented in RFC 2617. NTLM also has better security than Basic authentication. However, it is a proprietary protocol developed by Microsoft. A handful of Squid developers have essentially reverse-engineered it.

In order to use proxy authentication, you must also configure Squid to spawn a number of external helper processes. The Squid source code includes some programs that authenticate against a number of standard databases, including LDAP, NTLM, NCSA-style password files, and the standard Unix password database. The auth_param directive controls the configuration of all helper programs. I’ll go through it in detail in Chapter 12.

The auth_param directive and proxy_auth ACL is one of the few cases where their order in the configuration file is important. You must define at least one authentication helper (with auth_param) before any proxy_auth ACLs. If you don’t, Squid prints an error message and ignores the proxy_auth ACLs. This isn’t a fatal error, so Squid may start anyway, and all your users’ requests may be denied.

The proxy_auth ACL takes usernames as

values. However, most installations simply use the special value

REQUIRED:

auth_param ... acl Auth1 proxy_auth REQUIRED

In this case, any request with valid credentials matches the ACL. If you need fine-grained control, you can specify individual usernames:

auth_param ... acl Auth1 proxy_auth allan bob charlie acl Auth2 proxy_auth dave eric frank

Tip

Proxy authentication doesn’t work with HTTP interception

because the user-agent doesn’t realize it’s talking to a proxy

rather than the origin server. The user-agent doesn’t know that it

should send a Proxy-Authorization header in its

requests. See Section

9.2 for additional details.

src_as

This type checks that the client (source) IP address belongs to a specific AS number. (See Section 6.1.1.6 for information on how Squid maps AS numbers to IP addresses.) As an example, consider the fictitious ISP that uses AS 64222 and advertises the 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, and 192.168.0.0/16 networks. You can write an ACL like this, which allows requests from any host in the ISP’s address space:

acl TheISP src 10.0.0.0/8 acl TheISP src 172.16.0.0/12 acl TheISP src 192.168.0.0/16 http_access allow TheISP

Alternatively, you can write it like this:

acl TheISP src_as 64222 http_access allow TheISP

Not only is the second form shorter, it also means that if the ISP adds more networks, you won’t have to update your ACL configuration.

dst_as

The dst_as ACL is often used with the cache_peer_access directive. In this way, Squid can forward cache misses in a manner consistent with IP routing. Consider an ISP that exchanges routes with a few other ISPs. Each ISP operates their own caching proxy, and these proxies can forward requests to each other. Ideally, ISP A forwards cache misses for servers on ISP B’s network to ISP B’s caching proxy. An easy way to do this is with AS ACLs and the cache_peer_access directive:

acl ISP-B-AS dst_as 64222 acl ISP-C-AS dst_as 64333 cache_peer proxy.isp-b.net parent 3128 3130 cache_peer proxy.isp-c.net parent 3128 3130 cache_peer_access proxy.isb-b.net allow ISP-B-AS cache_peer_access proxy.isb-c.net allow ISP-C-AS

These access controls make sure that the only requests sent to the two ISPs are for their own origin servers. I’ll talk further about cache cooperation in Chapter 10.

snmp_community

The snmp_community ACL is meaningful only for SNMP queries, which are controlled by the snmp_access directive. For example, you might write:

acl OurCommunityName snmp_community hIgHsEcUrItY acl All src 0/0 snmp_access allow OurCommunityName snmp_access deny All

In this case, an SNMP query is allowed only if the community

name is set to hIgHsEcUrItY.

maxconn

The maxconn ACL refers to the number of simultaneous connections from a client’s IP address. Some Squid administrators find this a useful way to prevent users from abusing the proxy or consuming too many resources.

The maxconn ACL matches a request when that request exceeds the number you specify. For this reason, you should use maxconn ACLs only in deny rules. Consider this example:

acl OverConnLimit maxconn 4 http_access deny OverConnLimit

In this case, Squid allows up to four connections at once from each IP address. When a client makes the fifth connection, the OverConnLimit ACL is matched, and the http_access rule denies the request.

The maxconn ACL feature relies on Squid’s client database. This database keeps a small data structure in memory for each client IP address. If you have a lot of clients, this database may consume a significant amount of memory. You can disable the client database in the configuration file with the client_db directive. However, if you disable the client database, the maxconn ACL will no longer work.

arp

The arp ACL is used to check the Media Access Control (MAC) address (typically Ethernet) of cache clients. The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) is the way that hosts find the MAC address corresponding to an IP address. This feature came about when some university students discovered that, under Microsoft Windows, they could set a system’s IP address to any value. Thus, they were able to circumvent Squid’s address-based controls. To escalate this arms race, a savvy system administrator gave Squid the ability to check the client’s Ethernet addresses.

Unfortunately, this feature uses nonportable code. If you use

Solaris or Linux, you should be able to use arp

ACLs. If not, you’re out of luck. The best way to find out is to add

the —enable-arp-acl option when you run ./configure.

The arp ACL feature contains another important limitation. ARP is a datalink layer protocol. It works only for hosts on the same subnet as Squid. You can’t easily discover the MAC address of a host on a different subnet. If you have routers between Squid and your users, you probably can’t use arp ACLs.

Now that you know when not to use them, let’s see how arp ACLs actually look. The values are Ethernet addresses, as you would see in ifconfig and arp output. For example:

acl WinBoxes arp 00:00:21:55:ed:22 acl WinBoxes arp 00:00:21:ff:55:38

srcdom_regex

The srcdom_regex ACL allows you

to use regular expression matching on client domain

names. This is similar to the srcdomain ACL,

which uses modified substring matching. The same caveats apply here:

some client addresses don’t resolve back to domain names. As an

example, the following ACL matches hostnames that begin with

dhcp:

acl DHCPUser srcdom_regex -i ^dhcp

Because of the leading ^

symbol, this ACL matches the hostname

dhcp12.example.com, but not

host12.dhcp.example.com.

dstdom_regex

The dstdom_regex ACL is obviously similar, except that it applies to origin server names. The issues with dstdomain are relevant here, too. The following example matches hostnames that begin with www:

acl WebSite dstdom_regex -i ^www\.

Here is another useful regular expression that matches IP addresses given in URL hostnames:

acl IPaddr dstdom_regex [0-9]$

This works because Squid requires URL hostnames to be fully qualified. Since none of the global top-level domains end with a digit, this ACL matches only IP addresses, which do end with a number.

url_regex

You can use the url_regex ACL to match any part of a requested URL, including the transfer protocol and origin server hostname. For example, this ACL matches MP3 files requested from FTP servers:

acl FTPMP3 url_regex -i ^ftp://.*\.mp3$

urlpath_regex

The urlpath_regex ACL is very similar to

url_regex, except that the transfer protocol and hostname aren’t

included in the comparison. This makes certain types of checks much

easier. For example, let’s say you need to deny requests with

sex in the URL, but still

possibly allow requests that have sex in their hostname:

acl Sex urlpath_regex sex

As another example, let’s say you want to provide special treatment for cgi-bin requests. You can catch some of them with this ACL:

acl CGI1 urlpath_regex ^/cgi-bin

Of course, CGI programs aren’t necessarily kept under /cgi-bin/, so you’d probably want to write additional ACLs to catch the others.

browser

Most HTTP requests include a User-Agent header. The value of this

header is typically something strange like:

Mozilla/4.51 [en] (X11; I; Linux 2.2.5-15 i686)

The browser ACL performs regular

expression matching on the value of the User-Agent header. For example, to deny

requests that don’t come from a Mozilla browser, you can use:

acl Mozilla browser Mozilla http_access deny !Mozilla

Before using the browser ACL, be sure

that you fully understand the User-Agent strings your cache receives.

Some user-agents lie about their identity. Even Squid has a feature

to rewrite User-agent headers in

requests that it forwards. With browsers such as Opera and KDE’s

Konqueror, users can send different user-agent strings to different

origin servers or omit them altogether.

req_mime_type

The req_mime_type ACL refers to the Content-Type

header of the client’s HTTP request. Content-Type headers usually appear only

in requests with message bodies. POST and PUT requests might include the header, but

GET requests don’t. You might be

able to use the req_mime_type ACL to detect

certain file uploads and some types of HTTP tunneling

requests.

The req_mime_type ACL values are regular expressions. To catch audio file types, you can use an ACL like this:

acl AuidoFileUploads req_mime_type -i ^audio/

rep_mime_type

The rep_mime_type ACL refers to

the Content-Type

header of the origin server’s HTTP response. It is really only

meaningful when used in an http_reply_access

rule. All other access control forms are based on aspects of the

client’s request. This one is based on the response.

If you want to try blocking Java code with Squid, you might use some access rules like this:

acl JavaDownload rep_mime_type application/x-java http_reply_access deny JavaDownload

External ACLs

Squid Version 2.5 introduces a new feature: external ACLs. You instruct Squid to send certain pieces of information to an external process. This helper process then tells Squid whether the given data is a match or not.

Squid comes with a number of external ACL helper programs; most determine whether or not the named user is a member of a particular group. See Section 12.5 for descriptions of those programs and for information on how to write your own. For now, I’ll explain how to define and utilize an external ACL type.

The external_acl_type directive defines a new external ACL type. Here’s the general syntax:

external_acl_typetype-name[options]formathelper-command

type-name is a user-defined string.

You’ll also use it in an acl line to reference

this particular helper.

Squid currently supports the following options:

- ttl=

n The amount of time, in seconds, to cache the result for values that are a match. The default is 3600 seconds, or 1 hour.

- negative_ttl=

n The amount of time, in seconds, to cache the result for values that aren’t a match. The default is 3600 seconds, or 1 hour.

- concurrency=

n The number of helper processes to spawn. The default is 5.

- cache=

n The maximum number of results to cache. The default is 0, which doesn’t limit the cache size.

format is one or more keywords that begin with the % character. Squid currently supports the following format tokens:

- %LOGIN

The username, taken from proxy authentication credentials.

- %IDENT

The username, taken from an RFC 1413 ident query.

- %SRC

The IP address of the client.

- %DST

The IP address of the origin server.

- %PROTO

The transfer protocol (e.g., HTTP, FTP, etc.).

- %PORT

The origin server TCP port number.

- %METHOD

The HTTP request method.

- %{

Header} The value of an HTTP request header; for example, %{User-Agent} causes Squid to send strings like this to the authenticator:

"Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Win32)"

- %{Hdr:

member} Selects certain members of list-based HTTP headers, such as

Cache-Control; for example, given this HTTP header:X-Some-Header: foo=xyzzy, bar=plugh, foo=zoinks

and the token

%{X-Some-Header:foo}, Squid sends this string to the external ACL process:foo=xyzzy, foo=zoinks

- %{Hdr:;

member} The same as

%{Hdr:member}, except that the;character is the list separator. You can use any nonalphanumeric character as the separator.

helper-command is the command that Squid spawns for the helper. You may include command arguments here as well. For example, the entire command may be something like:

/usr/local/squid/libexec/my-acl-prog.pl -X -5 /usr/local/squid/etc/datafile

Putting all these together results in a long line. Squid’s configuration file doesn’t support the backslash line-continuation technique shown here, so remember that all these must go on a single line:

external_acl_type MyAclType cache=100 %LOGIN %{User-Agent} \

/usr/local/squid/libexec/my-acl-prog.pl -X -5 \

/usr/local/squid/share/usernames \

/usr/local/squid/share/useragentsNow that you know how to define an external ACL, the next step is to write an acl line that references it. This is relatively straightforward. The syntax is as follows:

aclacl-nameexternaltype-name[args...]

Here is a simple example:

acl MyAcl external MyAclType

Squid accepts any number of optional arguments following the

type-name. These are sent to the helper

program for each request, after the expanded tokens. See my

description of the unix_group helper in Section 12.5.3 for an example

of this feature.

Dealing with Long ACL Lists

ACL lists can sometimes be very long. Such lists are awkward to maintain inside the squid.conf file. Also, you may need to generate Squid ACL lists automatically from other sources. In these cases, you’ll be happy to know that you can include ACL lists from external files. The syntax is as follows:

aclname"filename"

The double quotes here instruct Squid to open

filename and assign its contents to the

ACL. For example, instead of this:

acl Foo BadClients 1.2.3.4 1.2.3.5 1.2.3.6 1.2.3.7 1.2.3.9 ...

you can do this:

acl Foo BadClients "/usr/local/squid/etc/BadClients"

and put the IP addresses into the BadClients file:

1.2.3.4 1.2.3.5 1.2.3.6 1.2.3.7 1.2.3.9 ...

Your file may include comments that begin with a # character. Note that each entry in the

file must be on a separate line. Whereas a space character delimits

values on an acl line, newlines are the delimiter

for files containing ACL values.

How Squid Matches Access Control Elements

It is important to understand how Squid searches ACL elements for a match. When an ACL element has more than one value, any single value can cause a match. In other words, Squid uses OR logic when checking ACL element values. Squid stops searching when it finds the first value that causes a match. This means that you can reduce delays by placing likely matches at the beginning of a list.

Let’s look at a specific example. Consider this ACL definition:

acl Simpsons ident Maggie Lisa Bart Marge Homer

When Squid encounters the Simpsons ACL in

an access list, it performs the ident lookup. Let’s see what happens

when the user’s ident server returns Marge. Squid’s ACL code compares this value

to Maggie, Lisa, and Bart before finding a match with Marge. At this point, the search terminates,

and we say that the Simpsons ACL matches the

request.

Actually, that’s a bit of a lie. The ident

ACL values aren’t stored as an unordered list. Rather, they are stored

as an splay tree. This means that Squid doesn’t end up searching all

the names in the event of a nonmatch. Searching an splay tree with

N items requires

log(N) comparisons. Many other ACL types use

splay trees as well. The regular expression-based types, however,

don’t.

Since regular expressions can’t be sorted, they are stored as linked lists. This makes them inefficient for large lists, especially for requests that don’t match any of the regular expressions in the list. In an attempt to improve this situation, Squid moves a regular expression to the top of the list when a match occurs. In fact, due to the nature of the ACL matching code, Squid moves matched entries to the second position in the list. Thus, commonly matched values naturally migrate to the top of the ACL list, which should reduce the number of comparisons.

Let’s look at another simple example:

acl Schmever port 80-90 101 103 107 1 2 3 9999

This ACL is a match for a request to an origin server port between 80 and 90, and all the other individual listed port numbers. For a request to port 80, Squid matches the ACL by looking at the first value. For port 9999, all the other values are checked first. For a port number not listed, Squid checks every value before declaring the ACL isn’t a match. As I’ve said before, you can optimize the ACL matching by placing the more common values first.

Access Control Rules

As I mentioned earlier, ACL elements are the first step in building access controls. The second step is the access control rules, where you combine elements to allow or deny certain actions. You’ve already seen some http_access rules in the preceding examples. Squid has a number of other access control lists:

- http_access

This is your most important access list. It determines which client HTTP requests are allowed, and which are denied. If you get the http_access configuration wrong, your Squid cache may be vulnerable to attacks and abuse from people who shouldn’t have access to it.

- http_reply_access

The http_reply_access list is similar to http_access. The difference is that the former list is checked when Squid receives a reply from an origin server or upstream proxy. Most access controls are based on aspects of the client’s request, in which case the http_access list is sufficient. However, some people prefer also to allow or deny requests based on the reply content type. Because Squid doesn’t know the content type value until it receives the server’s reply, this additional access list is necessary. See Section 6.3.9 for more information.

- icp_access

If your Squid cache is configured to serve ICP replies (see Section 10.6), you should use the icp_access list. In most cases, you’ll want to allow ICP requests only from your neighbor caches.

- no_cache

You can use the no_cache access list to tell Squid it must never store certain responses (on disk or in memory). This list is typically used in conjunction with dst, dstdomain, and url_regex ACLs.

The “no” in no_cache causes some confusion because of double negatives. A request that is denied by the no_cache list isn’t cached. In other words

no_cachedeny ... is the way to make something uncachable. See Section 6.3.10 for an example.- miss_access

The miss_access list is primarily useful for a Squid cache with sibling neighbors. It determines how Squid handles requests that are cache misses. This feature is necessary for Squid to enforce sibling relationships with its neighbors. See Section 6.3.7 for an example.

- redirector_access

This access list determines which requests are sent to one of the redirector processes (see Chapter 11). By default, all requests go through a redirector if you are using one. You can use the redirector_access list to prevent certain requests from being rewritten. This is particularly useful because a redirector receives less information about a particular request than does the access control system.

- ident_lookup_access

The ident_lookup_access list is similar to redirector_access. It enables you to make “lazy” ident lookups for certain requests. Squid doesn’t issue ident queries by default. It does so only for requests that are allowed by the ident_lookup_access rules (or by an ident ACL).

- always_direct

This access list affects how a Squid cache with neighbors forwards cache misses. Usually Squid tries to forward cache misses to a parent cache, and/or Squid uses ICP to locate cached responses in neighbors. However, when a request matches an always_direct rule, Squid forwards the request directly to the origin server.

With this list, matching an

allowrule causes Squid to forward the request directly. See Section 10.4.4 for more information and an example.- never_direct

Not surprisingly, never_direct is the opposite of always_direct. Cache miss requests that match this list must be sent to a neighbor cache. This is particularly useful for proxies behind firewalls.

With this list, matching an

allowrule causes Squid to forward the request to a neighbor. See Section 10.4.3 for more information and an example.- snmp_access

This access list applies to queries sent to Squid’s SNMP port. The ACLs that you can use with this list are snmp_community and src. You can also use srcdomain, srcdom_regex, and src_as if you really want to. See Section 14.3 for an example.

- broken_posts

This access list affects the way that Squid handles certain

POSTrequests. Some older user-agents are known to send an extra CRLF (carriage return and linefeed) at the end of the request body. That is, the message body is two bytes longer than indicated by theContent-Lengthheader. Even worse, some older HTTP servers actually rely on this incorrect behavior. When a request matches this access list, Squid emulates the buggy client and sends the extra CRLF characters.

Squid has a number of additional configuration directives that use ACL elements. Some of these used to be global settings that were modified to use ACLs to provide more flexibility.

- cache_peer_access

This access list controls the HTTP requests and ICP/HTCP queries that are sent to a neighbor cache. See Section 10.4.1 for more information and examples.

- reply_body_max_size

This access list restricts the maximum acceptable size of an HTTP reply body. See Appendix A for more information.

- delay_access

This access rule list controls whether or not the delay pools are applied to the (cache miss) response for this request. See Appendix C.

- tcp_outgoing_address

This access list binds server-side TCP connections to specific local IP addresses. See Appendix A.

- tcp_outgoing_tos

This access list can set different TOS/Diffserv values in TCP connections to origin servers and neighbors. See Appendix A.

- header_access

With this directive, you can configure Squid to remove certain HTTP headers from the requests that it forwards. For example, you might want to automatically filter out

Cookieheaders in requests sent to certain origin servers, such as doubleclick.net. See Appendix A.- header_replace

This directive allows you to replace, rather than just remove, the contents of HTTP headers. For example, you can set the

User-Agentheader to a bogus value to keep certain origin servers happy while still protecting your privacy. See Appendix A.

Access Rule Syntax

The syntax for an access control rule is as follows:

access_listallow|deny [!]ACLname...

For example:

http_access allow MyClients http_access deny !Safe_Ports http_access allow GameSites AfterHours

When reading the configuration file, Squid makes only one pass

through the access control lines. Thus, you must define the ACL

elements (with an acl line) before

referencing them in an access list. Furthermore, the order of the

access list rules is very important. Incoming requests are checked in

the same order that you write them. Placing the most common ACLs early

in the list may reduce Squid’s CPU usage.

Tip

For most of the access lists, the meaning of deny and allow are obvious. Some of them, however,

aren’t so intuitive. In particular, pay close attention when writing

always_direct,

never_direct, and no_cache

rules. In the case of always_direct, an

allow rule means that matching

requests are forwarded directly to origin servers. An

always_direct deny rule means that matching requests

aren’t forced to go directly to origin servers, but may still do so

if, for example, all neighbor caches are unreachable. The

no_cache rules are tricky as well. Here, you

must use deny for requests that

must not be cached.

How Squid Matches Access Rules

Recall that Squid uses OR logic when searching ACL elements. Any single value in an acl can cause a match.

It’s the opposite for access rules, however. For http_access and the other rule sets, Squid uses AND logic. Consider this generic example:

access_list allow ACL1 ACL2 ACL3

For this rule to be a match, the request must match each of ACL1, ACL2, and ACL3. If any of those ACLs don’t match the request, Squid stops searching this rule and proceeds to the next. Within a single rule, you can optimize rule searching by putting least-likely-to-match ACLs first. Consider this simple example:

acl A method http acl B port 8080 http_access deny A B

This http_access rule is somewhat

inefficient because the A ACL is

more likely to be matched than B.

It is better to reverse the order so that, in most cases, Squid only

makes one ACL check, instead of two:

http_access deny B A

One mistake people commonly make is to write a rule that can never be true. For example:

acl A src 1.2.3.4 acl B src 5.6.7.8 http_access allow A B

This rule is never going to be true because a source IP address can’t be equal to both 1.2.3.4 and 5.6.7.8 at the same time. Most likely, someone who writes a rule like that really means this:

acl A src 1.2.3.4 5.6.7.8 http_access allow A

As with the algorithm for matching the values of an ACL, when Squid finds a matching rule in an access list, the search terminates. If none of the access rules result in a match, the default action is the opposite of the last rule in the list. For example, consider this simple access configuration:

acl Bob ident bob http_access allow Bob

Now if the user Mary makes a

request, she is denied. The last (and only) rule in the list is an

allow rule, and it doesn’t match

the username Mary. Thus, the

default action is the opposite of allow, so the request is denied. Similarly,

if the last entry is a deny rule,

the default action is to allow the request. It is good practice always

to end your access lists with explicit rules that either allow or deny

all requests. To be perfectly clear, the previous example should be

written this way:

acl All src 0/0 acl Bob ident bob http_access allow Bob http_access deny All

The src 0/0 ACL is an easy

way to match each and every type of request.

Access List Style

Squid’s access control syntax is very powerful. In most cases, you can probably think of two or more ways to accomplish the same thing. In general, you should put the more specific and restrictive access controls first. For example, rather than:

acl All src 0/0 acl Net1 src 1.2.3.0/24 acl Net2 src 1.2.4.0/24 acl Net3 src 1.2.5.0/24 acl Net4 src 1.2.6.0/24 acl WorkingHours time 08:00-17:00 http_access allow Net1 WorkingHours http_access allow Net2 WorkingHours http_access allow Net3 WorkingHours http_access allow Net4 http_access deny All

you might find it easier to maintain and understand the access control configuration if you write it like this:

http_access allow Net4 http_access deny !WorkingHours http_access allow Net1 http_access allow Net2 http_access allow Net3 http_access deny All

Whenever you have a rule with two or more ACL elements, it’s always a good idea to follow it up with an opposite, more general rule. For example, the default Squid configuration denies cache manager requests that don’t come from the localhost IP address. You might be tempted to write it like this:

acl CacheManager proto cache_object acl Localhost src 127.0.0.1 http_access deny CacheManager !Localhost

However, the problem here is that you haven’t yet allowed the cache manager requests that do come from localhost. Subsequent rules may cause the request to be denied anyway. These rules have this undesirable behavior:

acl CacheManager proto cache_object acl Localhost src 127.0.0.1 acl MyNet 10.0.0.0/24 acl All src 0/0 http_access deny CacheManager !Localhost http_access allow MyNet http_access deny All

Since a request from localhost doesn’t match MyNet, it gets denied. A better way to write

the rules is like this:

http_access allow CacheManager localhost http_access deny CacheManager http_access allow MyNet http_access deny All

Delayed Checks

Some ACLs can’t be checked in one pass because the necessary information is unavailable. The ident, dst, srcdomain, and proxy_auth types fall into this category. When Squid encounters an ACL that can’t be checked, it postpones the decision and issues a query for the necessary information (IP address, domain name, username, etc.). When the information is available, Squid checks the rules all over again, starting at the beginning of the list. It doesn’t continue where the previous check left off. If possible, you may want to move these likely-to-be-delayed ACLs near the top of your rules to avoid unnecessary, repeated checks.

Because these delays are costly (in terms of time), Squid caches the information whenever possible. Ident lookups occur for each connection, rather than each request. This means that persistent HTTP connections can really benefit you in situations where you use ident queries. Hostnames and IP addresses are cached as specified by the DNS replies, unless you’re using the older external dnsserver processes. Proxy Authentication information is cached as I described previously in Section 6.1.2.12.

Slow and Fast Rule Checks

Internally, Squid considers some access rule checks fast, and others slow. The difference is whether or not Squid postpones its decision to wait for additional information. In other words, a slow check may be deferred while Squid asks for additional data, such as:

A reverse DNS lookup: the hostname for a client’s IP address

An RFC 1413 ident query: the username associated with a client’s TCP connection

An authenticator: validating the user’s credentials

A forward DNS lookup: the origin server’s IP address

An external, user-defined ACL

Some access rules use fast checks out of necessity. For example, the icp_access rule is a fast check. It must be fast, to serve ICP queries quickly. Furthermore, certain ACL types, such as proxy_auth, are meaningless for ICP queries. The following access rules are fast checks:

header_access

reply_body_max_size

reply_access

ident_lookup

delay_access

miss_access

broken_posts

icp_access

cache_peer_access

redirector_access

snmp_access

The following ACL types may require information from external sources (DNS, authenticators, etc.) and are thus incompatible with fast access rules:

srcdomain, dstdomain, srcdom_regex, dstdom_regex

dst, dst_as

proxy_auth

ident

external_acl_type

This means, for example, that you can’t reliably use an ident ACL in a header_access rule.

Common Scenarios

Because access controls can be complicated, this section contains a few examples. They demonstrate some of the common uses for access controls. You should be able to adapt them to your particular needs.

Allowing Local Clients Only

Almost every Squid installation should restrict access based on client IP addresses. This is one of the best ways to protect your system from abuses. The easiest way to do this is write an ACL that contains your IP address space and then allow HTTP requests for that ACL and deny all others:

acl All src 0/0 acl MyNetwork src 172.16.5.0/24 172.16.6.0/24 http_access allow MyNetwork http_access deny All

Most likely, this access control configuration will be too

simple, so you’ll need to add more lines. Remember that the order of

the http_access lines is important. Don’t add

anything after deny All. Instead,

add the new rules before or after allow

MyNetwork as necessary.

Blocking a Few Misbehaving Clients

For one reason or another, you may find it necessary to deny access for a particular client IP address. This can happen, for example, if an employee or student launches an aggressive web crawling agent that consumes too much bandwidth or other resources. Until you can stop the problem at the source, you can block the requests coming to Squid with this configuration:

acl All src 0/0 acl MyNetwork src 172.16.5.0/24 172.16.6.0/24 acl ProblemHost src 172.16.5.9 http_access deny ProblemHost http_access allow MyNetwork http_access deny All

Denying Pornography

Blocking access to certain content is a touchy subject. Often, the hardest part about using Squid to deny pornography is coming up with the list of sites that should be blocked. You may want to maintain such a list yourself, or get one from somewhere else. The “Access Controls” section of the Squid FAQ has links to freely available lists.

The ACL syntax for using such a list depends on its contents. If the list contains regular expressions, you probably want something like this:

acl PornSites url_regex "/usr/local/squid/etc/pornlist" http_access deny PornSites

On the other hand, if the list contains origin server hostnames, simply change url_regex to dstdomain in this example.

Restricting Usage During Working Hours

Some corporations like to restrict web usage during working hours, either to save bandwidth, or because policy forbids employees from doing certain things while working. The hardest part about this is differentiating between appropriate and inappropriate use of the Internet during these times. Unfortunately, I can’t help you with that. For this example, I’m assuming that you’ve somehow collected or acquired a list of web site domain names that are known to be inappropriate. The easy part is configuring Squid:

acl NotWorkRelated dstdomain "/usr/local/squid/etc/not-work-related-sites" acl WorkingHours time D 08:00-17:30 http_access deny !WorkingHours NotWorkRelated

Notice that I’ve placed the !WorkingHours ACL first in the rule. The

dstdomain ACL is expensive (comparing strings and

traversing lists), but the time ACL is a simple

inequality check.

Let’s take this a step further and understand how to combine something like this with the source address controls described previously. Here’s one way to do it:

acl All src 0/0 acl MyNetwork src 172.16.5.0/24 172.16.6.0/24 acl NotWorkRelated dstdomain "/usr/local/squid/etc/not-work-related-sites" acl WorkingHours time D 08:00-17:30 http_access deny !WorkingHours NotWorkRelated http_access allow MyNetwork http_access deny All

This scheme works because it accomplishes our goal of denying

certain requests during working hours and allowing requests only from

your own network. However, it might be somewhat inefficient. Note that

the NotWorkRelated ACL is searched

for all requests, regardless of the source IP address. If that list is

long, you’ll waste CPU resources by searching it for requests from

outside your network. Thus, you may want to change the rules around

somewhat:

http_access deny !MyNetwork http_access deny !WorkingHours NotWorkRelated http_access Allow All

Here we’ve delayed the most expensive check until the very end. Outsiders that may be trying to abuse Squid will not be wasting your CPU cycles.

Preventing Squid from Talking to Non-HTTP Servers

You need to minimize the chance that Squid can communicate with certain types of TCP/IP servers. For example, people should never be able to use your Squid cache to relay SMTP (email) traffic. I covered this previously when introducing the port ACL. However, it is such an important part of your access controls that I’m presenting it here as well.

First of all, you have to worry about the CONNECT request method. User agents use this

method to tunnel TCP connections through an HTTP proxy. It was

invented for HTTP/TLS (a.k.a SSL) requests, and this remains the

primary use for the CONNECT method.

Some user-agents may also tunnel NNTP/TLS traffic through firewall

proxies. All other uses should be rejected. Thus, you’ll need an

access list that allows CONNECT

requests to HTTP/TLS and NNTP/TLS ports only.

Secondly, you should prevent Squid from connecting to certain services such as SMTP. You can either allow safe ports or deny dangerous ports. I’ll give examples for both techniques.

Let’s start with the rules present in the default squid.conf file:

acl Safe_ports port 80 # http acl Safe_ports port 21 # ftp acl Safe_ports port 443 563 # https, snews acl Safe_ports port 70 # gopher acl Safe_ports port 210 # wais acl Safe_ports port 280 # http-mgmt acl Safe_ports port 488 # gss-http acl Safe_ports port 591 # filemaker acl Safe_ports port 777 # multiling http acl Safe_ports port 1025-65535 # unregistered ports acl SSL_ports port 443 563 acl CONNECT method CONNECT http_access deny !Safe_ports http_access deny CONNECT !SSL_ports <additional http_access lines as necessary...>

Our Safe_ports ACL lists all

privileged ports (less than 1024) to which Squid may have valid

reasons for connecting. It also lists the entire nonprivileged port

range. Notice that the Safe_ports

ACL includes the secure HTTP and NNTP ports (443 and 563) even though

they also appear in the SSL_ports

ACL. This is because the Safe_ports

ACL is checked first in the rules. If you swap the order of the first

two http_access lines, you could

probably remove 443 and 563 from the Safe_ports list, but it’s hardly worth the

trouble.

The other way to approach this is to list the privileged ports that are known to be unsafe:

acl Dangerous_ports 7 9 19 22 23 25 53 109 110 119 acl SSL_ports port 443 563 acl CONNECT method CONNECT http_access deny Dangerous_ports http_access deny CONNECT !SSL_ports <additional http_access lines as necessary...>

Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with all these strange port numbers. You can find out what each one is for by reading the /etc/services file on a Unix system or by reading IANA’s list of registered TCP/UDP port numbers at http://www.iana.org/assignments/port-numbers.

Giving Certain Users Special Access

Organizations that employ username-based access controls often need to give certain users special privileges. In this simple example, there are three elements: all authenticated users, the usernames of the administrators, and a list of pornographic web sites. Normal users aren’t allowed to view pornography, but the admins have the dubious job of maintaining the list. They need to connect to all servers to verify whether or not a particular site should be placed in the pornography list. Here’s how to accomplish the task:

auth_param basic program /usr/local/squid/libexec/ncsa_auth

/usr/local/squid/etc/passwd

acl Authenticated proxy_auth REQUIRED

acl Admins proxy_auth Pat Jean Chris

acl Porn dstdomain "/usr/local/squid/etc/porn.domains"

acl All src 0/0

http_access allow Admins

http_access deny Porn

http_access allow Authenticated

http_access deny AllLet’s examine how this all works. First, there are three ACL definitions. The Authenticated ACL matches any valid proxy authentication credentials. The Admins ACL matches valid credentials from users Pat, Jean, and Chris. The Porn ACL matches certain origin server hostnames found in the porn.domains file.

This example has four access control rules. The first checks only the Admins ACL and allows all requests from Pat, Jean, and Chris. For other users, Squid moves on to the next rule. According to the second rule, a request is denied if its origin server hostname is in the porn.domains file. For requests that don’t match the Porn ACL, Squid moves on to the third rule. Here, the request is allowed if it contains valid authentication credentials. The external authenticator (ncsa_auth in this case) is responsible for deciding whether or not the credentials are valid. If they aren’t, the final rule applies, and the request is denied.

Note that the ncsa_auth authenticator isn’t a requirement. You can use any of the numerous authentication helpers described in Chapter 12.

Preventing Abuse from Siblings

If you open up your cache to peer with other caches, you need to take additional precautions. Caches often use ICP to discover which objects are stored in their neighbors. You should accept ICP queries only from known and approved neighbors.

Furthermore, you can configure Squid to enforce a sibling

relationship by using the miss_access rule list. Squid checks these

rules only when forwarding cache misses, never cache hits. Thus, all

requests must first pass the http_access rules before the miss_access list comes into play.

In this example, there are three separate ACLs. One is for the local users that connect directly to this cache. Another is for a child cache, which is allowed to forward requests that are cache misses. The third is a sibling cache, which must never forward a request that results in a cache miss. Here’s how it all works:

alc All src 0/0 acl OurUsers src 172.16.5.0/24 acl ChildCache src 192.168.1.1 acl SiblingCache src 192.168.3.3 http_access allow OurUsers http_access allow ChildCache http_access allow SiblingCache http_access deny All miss_access deny SiblingCache icp_access allow ChildCache icp_access allow SiblingCache icp_access deny All

Denying Requests with IP Addresses

As I mentioned in Section 6.1.2.4, the dstdomain type is good for blocking access to specific origin servers. However, clever users might be able to get around the rule by replacing URL hostnames with their IP addresses. If you are desperate to stop such requests, you may want to block all requests that contain an IP address. You can do so with a redirector (see Chapter 11) or with a semicomplicated dstdom_regex ACL like this:

acl IPForHostname dstdom_regex ^[0-9]+\.[0-9]+\.[0-9]+\.[0-9]+$ http_access deny IPForHostname

An http_reply_access Example

Recall that the response’s content type is the only new information available when Squid checks the http_reply_access rules. Thus, you can keep the http_reply_access rules very simple. You need only check the rep_mime_type ACLs. For example, here’s how you can deny responses with certain content types:

acl All src 0/0 acl Movies rep_mime_type video/mpeg acl MP3s rep_mime_type audio/mpeg http_reply_access deny Movies http_reply_access deny MP3s http_reply_access allow All

Preventing Cache Hits for Local Sites

If you have a number of origin servers on your network, you may want to configure Squid so that their responses are never cached. Because the servers are nearby, they don’t benefit too much from cache hits. Additionally, it frees up storage space for other (far away) origin servers.

The first step is to define an ACL for the local servers. You might want to use an address-based ACL, such as dst:

acl LocalServers dst 172.17.1.0/24

If the servers don’t live on a single subnet, you might find it easier to create a dstdomain ACL:

acl LocalServers dstdomain .example.com

Next, you simply deny caching of those servers with a no_cache access rule:

no_cache deny LocalServers

Tip

The no_cache rules don’t prevent your

clients from sending these requests to Squid. There is nothing you

can configure in Squid to stop such requests from coming. Instead,

you must configure the user-agents themselves.

If you add a no_cache rule after Squid has been running for a while, the cache may contain some objects that match the new rule. Prior to Squid Version 2.5, these previously cached objects might be returned as cache hits. Now, however, Squid purges any cached response for a request that matches a no_cache rule.

Testing Access Controls

As your access control configuration becomes longer, it also becomes more complicated. I

strongly encourage you to test your access controls before turning them

loose on a production server. Of course, the first thing you should do

is make sure that Squid can correctly parse your configuration file. Use

the -k parse feature for this:

% squid -k parse