Chapter 7. Disk Cache Basics

I’m going to talk a lot about disk storage and filesystems in this chapter. It is important to make sure you understand the difference between two related things: disk filesystems and Squid’s storage schemes.

Filesystems are features of particular operating systems. Almost every Unix variant has an implementation of the Unix File System (UFS). It is also sometimes known as the Berkeley Fast File System (FFS). Linux’s default filesystem is called ext2fs. Many operating systems also support newer filesystem technologies. These include names and acronyms such as advfs, xfs, and reiserfs.

Programs (such as Squid) interact with filesystems via a handful of system calls. These are functions such as

open( ), close(

), read( ), write(

), stat( ), and unlink( ). The arguments to these system calls

are either pathnames (strings) or file descriptors (integers). Filesystem

implementation details are hidden from programs. They typically use

internal data structures such as inodes, but Squid doesn’t know about that.

Squid has a number of different storage schemes. The schemes have different

properties and techniques for organizing and accessing cache data on the

disk. Most of them use the filesystem interface system calls (e.g.,

open( ), write( ), etc.).

Squid has five different storage schemes: ufs, aufs, diskd, coss, and null. The first three use the same directory layout, and they are thus interchangeable. coss is an attempt to implement a new filesystem specifically optimized for Squid. null is a minimal implementation of the API: it doesn’t actually read or write data to/from the disk.

Tip

Due to a poor choice of names, “UFS” might refer to either the Unix filesystem or the Squid storage scheme. To be clear here, I’ll write the filesystem as UFS and the storage scheme as ufs.

The remainder of this chapter focuses on the squid.conf directives that control the disk cache. This includes replacement policies, object removal, and freshness controls. For the most part, I’ll only talk about the default storage scheme: ufs. We’ll get to the alternative schemes and other tricks in the next chapter.

The cache_dir Directive

The cache_dir directive is one of the most important in squid.conf. It tells Squid where and how to store cache files on disk. The cache_dir directive takes the following arguments:

cache_dirschemedirectorysizeL1L2[options]

Scheme

Squid supports a number of different storage schemes. The default (and original) is

ufs. Depending on your operating system, you may

be able to select other schemes. You must use the —enable-storeio =

LIST option with ./configure to compile the optional code for

other storage schemes. I’ll discuss aufs,

diskd, coss, and

null in Section 8.7. For now, I’ll only

talk about the ufs scheme, which is compatible

with aufs and diskd.

Directory

The directory argument is a filesystem directory, under which Squid stores cached objects. Normally, a cache_dir corresponds to a whole filesystem or disk partition. It usually doesn’t make sense to put more than one cache directory on a single filesystem partition. Furthermore, I also recommend putting only one cache directory on each physical disk drive. For example, if you have two unused hard drives, you might do something like this:

# newfs /dev/da1d # newfs /dev/da2d # mount /dev/da1d /cache0 # mount /dev/da2d /cache1

And then add these lines to squid.conf:

cache_dir ufs /cache0 7000 16 256 cache_dir ufs /cache1 7000 16 256

If you don’t have any spare hard drives, you can, of course, use an existing filesystem partition. Select one with plenty of free space, perhaps /usr or /var, and create a new directory there. For example:

# mkdir /var/squidcache

Then add a line like this to squid.conf:

cache_dir ufs /var/squidcache 7000 16 256

Size

The third cache_dir argument specifies the size of the cache directory. This is an upper limit on the amount of disk space that Squid can use for the cache_dir. Calculating an appropriate value can be tricky. You lose some space to filesystem overheads, and you must leave enough free space for temporary files and swap.state logs (see Section 13.6). I recommend mounting the empty filesystem and running df:

% df -k Filesystem 1K-blocks Used Avail Capacity Mounted on /dev/da1d 3037766 8 2794737 0% /cache0 /dev/da2d 3037766 8 2794737 0% /cache1

Here you can see that the filesystem has about 2790 MB of available space. Remember that UFS reserves some “minfree” space, 8% in this case, which is why Squid can’t use the full 3040 MB in the filesystem.

You might be tempted just to put 2790 on the cache_dir

line. You might even to get away with it if your cache isn’t very busy

and if you rotate the log files often. To be safe, however, I

recommend taking off another 10% or so. This extra space will be used

by Squid’s swap.state file and

temporary files.

Note that the cache_swap_low directive also affects how much space Squid uses. I’ll talk about the low and high watermarks in Section 7.2.

The bottom line is that you should initially be conservative about the size of your cache_dir. Start off with a low estimate and allow the cache to fill up. After Squid runs for a week or so with full cache directories, you’ll be in a good position to re-evaluate the size settings. If you have plenty of free space, feel free to increase the cache directory size in increments of a few percent.

Inodes

Inodes are fundamental building blocks of Unix filesystems. They contain information about disk files, such as permissions, ownership, size, and timestamps. If your filesystem runs out of inodes, you can’t create new files, even if it has space available. Running out of inodes is bad, so you may want to make sure you have enough before running Squid.

The programs that create new filesystems (e.g., newfs or mkfs)

reserve some number of inodes based on the total size. These

programs usually allow you to set the ratio of inodes to disk space.

For example, see the -i option in the newfs and mkfs manpages. The ratio of disk space to

inodes determines the mean file size the filesystem can support.

Most Unix systems create one inode for each 4 KB, which is usually

sufficient for Squid. Research shows that, for most caching proxies,

the mean file size is about 10 KB. You may be able to get away with

8 KB per inode, but it is risky.

You can monitor your system’s inode usage with df -i. For example:

% df -ik Filesystem 1K-blocks Used Avail Capacity iused ifree %iused Mounted on /dev/ad0s1a 197951 57114 125001 31% 1413 52345 3% / /dev/ad0s1f 5004533 2352120 2252051 51% 129175 1084263 11% /usr /dev/ad0s1e 396895 6786 358358 2% 205 99633 0% /var /dev/da0d 8533292 7222148 628481 92% 430894 539184 44% /cache1 /dev/da1d 8533292 7181645 668984 91% 430272 539806 44% /cache2 /dev/da2d 8533292 7198600 652029 92% 434726 535352 45% /cache3 /dev/da3d 8533292 7208948 641681 92% 427866 542212 44% /cache4

As long as the inode usage (%iused) is less than the space usage

(Capacity), you’re in good shape.

Unfortunately, you can’t add more inodes to an existing filesystem.

If you find that you are running out of inodes, you need to stop

Squid and recreate your filesystems. If you’re not willing to do

that, decrease the cache_dir size

instead.

The relationship between disk space and process size

Squid’s disk space usage directly affects its memory usage as well. Every object that exists on disk requires a small amount of memory. Squid uses the memory as an index to the on-disk data. If you add a new cache directory or otherwise increase the disk cache size, make sure that you also have enough free memory. Squid’s performance degrades very quickly if its process size reaches or exceeds your system’s physical memory capacity.

Every object in Squid’s cache directories takes either 76 or 112 bytes of memory, depending on your system. The memory is allocated as StoreEntry, MD5 Digest, and LRU policy node structures. Small-pointer (i.e., 32-bit) systems, like those based on the Intel Pentium, take 76 bytes. On systems with CPUs that support 64-bit pointers, each object takes 112 bytes. You can find out how much memory these structures use on your system by viewing the Memory Utilization page of the cache manager (see Section 14.2.1.2).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to predict precisely how much additional memory is required for a given amount of disk space. It depends on the mean reply size, which typically fluctuates over time. Additionally, Squid uses memory for many other data structures and purposes. Don’t assume that your estimates are, or will remain, correct. You should constantly monitor Squid’s process size and consider shrinking the cache size if necessary.

L1 and L2

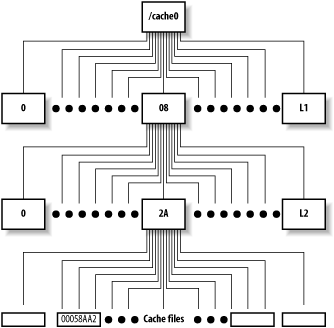

For the ufs, aufs, and diskd schemes, Squid creates a two-level directory tree underneath the cache directory. The L1 and L2 arguments specify the number of first- and second-level directories. The defaults are 16 and 256, respectively. Figure 7-1 shows the filesystem structure.

Some people think that Squid performs better, or worse, depending on the particular values for L1 and L2. It seems to make sense, intuitively, that small directories can be searched faster than large ones. Thus, L1 and L2 should probably be large enough so that each L2 directory has no more than a few hundred files.

For example, let’s say you have a cache directory that stores about 7000 MB. Given a mean file size of 10 KB, you can store about 700,000 files in this cache_dir. With 16 L1 and 256 L2 directories, there are 4096 total second-level directories. 700,000 ÷ 4096 leaves about 170 files in each second-level directory.

The process of creating swap directories with squid -z, goes faster for smaller values of L1 and L2. Thus, if your cache size is really small, you may want to reduce the number of L1 and L2 directories.

Squid assigns each cache object a unique file number. This is a 32-bit integer that uniquely identifies files on disk. Squid uses a relatively simple algorithm for turning file numbers into pathnames. The algorithm uses L1 and L2 as parameters. Thus, if you change L1 and L2, you change the mapping from file number to pathname. Changing these parameters for a nonempty cache_dir makes the existing files inaccessible. You should never change L1 and L2 after the cache directory has become active.

Squid allocates file numbers within a cache directory

sequentially. The file number-to-pathname algorithm (e.g., storeUfsDirFullPath( )) is written so that each group

of L2 files go into the same second-level directory. Squid does this

to take advantage of locality of reference. This algorithm increases

the probability that an HTML file and its embedded images are stored

in the same second-level directory. Some people expect Squid to spread

cache files evenly among the second-level directories. However, when

the cache is initially filling, you’ll find that only the first few

directories contain any files. For example:

% cd /cache0; du -k 2164 ./00/00 2146 ./00/01 2689 ./00/02 1974 ./00/03 2201 ./00/04 2463 ./00/05 2724 ./00/06 3174 ./00/07 1144 ./00/08 1 ./00/09 1 ./00/0A 1 ./00/0B ...

This is perfectly normal and nothing to worry about.

Options

Squid has two scheme-independent cache_dir

options: a read-only flag and a

max-size value.

read-only

The read-only option

instructs Squid to continue reading from the

cache_dir, but to stop storing new objects

there. It looks like this in squid.conf:

cache_dir ufs /cache0 7000 16 256 read-only

You might use this option if you want to migrate your cache

storage from one disk to another. If you simply add one

cache_dir and remove another, Squid’s hit ratio

decreases sharply. You can still get cache hits from the old

location when it is read-only. After some time, you can remove the

read-only cache directory from

the configuration.

max-size

With this option, you can specify the maximum object size to be stored in the cache directory. For example:

cache_dir ufs /cache0 7000 16 256 max-size=1048576

Note that the value is in bytes. In most situations, you

shouldn’t need to add this option. If you do, try to put the

cache_dir lines in order of increasing max-size.

Disk Space Watermarks

The cache_swap_low and cache_swap_high directives control the replacement of objects stored on disk. Their values are a percentage of the maximum cache size, which comes from the sum of all cache_dir sizes. For example:

cache_swap_low 90 cache_swap_high 95

As long as the total disk usage is below cache_swap_low, Squid doesn’t remove cached objects. As the cache size increases, Squid becomes more aggressive about removing objects. Under steady-state conditions, you should find that disk usage stays relatively close to the cache_swap_low value. You can see the current disk usage by requesting the storedir page from the cache manager (see Section 14.2.1.39).

Note that changing cache_swap_high probably won’t have a big impact on Squid’s disk usage. In earlier versions of Squid, this parameter played a more important role; now, however, it doesn’t.

Object Size Limits

You can control both the maximum and minimum size of cached objects. Responses larger than maximum_object_size aren’t stored on disk. They are still proxied, however. The logic behind this directive is that you don’t want a really big response to take up space better utilized by many small responses. The syntax is as follows:

maximum_object_size size-specificationHere are some examples:

maximum_object_size 100 KB maximum_object_size 1 MB maximum_object_size 12382 bytes maximum_object_size 2 GB

Squid checks the response size in two different ways. If the reply

includes a Content-Length header,

Squid compares its value to the maximum_object_size

value. If the content length is the larger of the two numbers, the

object becomes immediately uncachable and never consumes any disk

space.

Unfortunately, not every response has a Content-Length header. In this case, Squid

writes the response to disk as data comes in from the origin server.

Squid checks the object size again only when the response is complete.

Thus, if the object’s size reaches the

maximum_object_size limit, it continues consuming

disk space. Squid increments the total cache size only when it is done

reading a response.

In other words, the active, or in-transit, objects don’t contribute to the cache size value Squid maintains internally. This is good because it means Squid won’t remove other objects in the cache, unless the object remains cachable and then contributes to the total cache size. However, it is also bad because Squid may run out of free disk space if the reply is very large. To reduce the chance of this happening, you should also use the reply_body_max_size directive. A response that reaches the reply_body_max_size limit is cut off immediately.

Squid also has a minimum_object_size directive. It allows you to place a lower limit on the size of cached objects. Responses smaller than this size aren’t stored on disk or in memory. Note that this size is compared to the response’s content length (i.e., the size of the reply body), which excludes the HTTP headers.

Allocating Objects to Cache Directories

When Squid wants to store a cachable response on disk, it calls a function

that selects one of the cache directories. It then opens a disk file for

writing on the selected directory. If, for some reason, the open( ) call fails, the response isn’t

stored. In this case, Squid doesn’t try opening a disk file on one of

the other cache directories.

Squid has two of these cache_dir selection

algorithms. The default algorithm is called least-load; the alternative is round-robin.

The least-load algorithm, as

the name implies, selects that cache directory that currently has the

smallest workload. The notion of load depends on the underlying storage

scheme. For the aufs, coss,

and diskd schemes, the load is related to the

number of pending operations. For ufs, the load is

constant. For cases in which all cache_dirs have

equal load, the algorithm uses free space and maximum object sizes as

tie-breakers.

The selection algorithm also takes into account the max-size and read-only options. Squid skips a cache

directory if it knows the object size is larger than the limit. It also

always skips any read-only directories.

The round-robin algorithm also

uses load measurements. It always selects the next cache directory in

the list (subject to max-size and

read-only), as long as its load is

less than 100%.

Under some circumstances, Squid may fail to select a cache

directory. This can happen if all cache_dirs are

overloaded or if all have max-size

limits less than the size of the object. In this case, Squid simply

doesn’t write the object to disk. You can use the cache manager to track

the number of times Squid fails to select a cache directory. View the

store_io page (see Section 14.2.1.41), and find

the create.select_fail line.

Replacement Policies

The cache_replacement_policy directive controls the replacement policy for Squid’s disk cache. Version 2.5 offers three different replacement policies: least recently used (LRU), greedy dual-size frequency (GDSF), and least frequently used with dynamic aging (LFUDA).

LRU is the default policy, not only for Squid, but for most other caching products as well. LRU is a popular choice because it is almost trivial to implement and provides very good performance. On 32-bit systems, LRU uses slightly less memory than the others (12 versus 16 bytes per object). On 64-bit systems, all policies use 24 bytes per object.

Over the years, many researchers have proposed alternatives to LRU. These other policies are typically designed to optimize a specific characteristic of the cache, such as response time, hit ratio, or byte hit ratio. While the research almost always shows an improvement, the results can be misleading. Some of the studies use unrealistically small cache sizes. Other studies show that as cache size increases, the choice of replacement policy becomes less important.

If you want to use the GDSF or LFUDA policies, you must pass the —enable-removal-policies option to the ./configure script (see Section 3.4.1). Martin Arlitt and John Dilley of HP Labs wrote the GDSF and LFUDA implementation for Squid. You can read their paper online at http://www.hpl.hp.com/techreports/1999/HPL-1999-69.html. My O’Reilly book, Web Caching, also talks about these algorithms.

The cache_replacement_policy directive is unique in an important way. Unlike most of the other squid.conf directives, the location of this one is significant. The cache_replacment_policy value is actually used when Squid parses a cache_dir directive. You can change the replacement policy for a cache_dir by setting the replacement policy beforehand. For example:

cache_replacement_policy lru cache_dir ufs /cache0 2000 16 32 cache_dir ufs /cache1 2000 16 32 cache_replacement_policy heap GDSF cache_dir ufs /cache2 2000 16 32 cache_dir ufs /cache3 2000 16 32

In this case, the first two cache directories use LRU replacement, and the second two use GDSF. This characteristic of the replacement_policy directive is important to keep in mind if you ever decide to use the config option of the cache manager (see Section 14.2.1.7). The cache manager outputs only one (the last) replacement policy value, and places it before all of the cache directories. For example, you may have these lines in squid.conf:

cache_replacement_policy heap GDSF cache_dir ufs /tmp/cache1 10 4 4 cache_replacement_policy lru cache_dir ufs /tmp/cache2 10 4 4

but when you select config from the cache manager, you get:

cache_replacement_policy lru cache_dir ufs /tmp/cache1 10 4 4 cache_dir ufs /tmp/cache2 10 4 4

As you can see, the heap GDSF

setting for the first cache directory has been lost.

Removing Cached Objects

At some point you may find it necessary to manually remove one or more objects from Squid’s cache. This might happen if:

One of your users complains about always receiving stale data.

Your cache becomes “poisoned” with a forged response.

Squid’s cache index becomes corrupted after experiencing disk I/O errors or frequent crashes and restarts.

You want to remove some large objects to free up room for new data.

Squid was caching responses from local servers, and now you don’t want it to.

Some of these problems can be solved by forcing a reload in a web browser. However, this doesn’t always work. For example, some browsers display certain content types externally by launching another program; that program probably doesn’t have a reload button or even know about caches.

You can always use the squidclient program to reload a cached object

if necessary. Simply insert the -r option before the

URI:

% squidclient -r http://www.lrrr.org/junk >/tmp/foo

If you happen to have a refresh_pattern

directive with the ignore-reload

option set, you and your users may be unable to force a validation of

the cached response. In that case, you’ll be better off purging the

offending object or objects.

Removing Individual Objects

Squid accepts a custom request method for removing cached

objects. The PURGE method isn’t one

of the official HTTP request methods. It is different from DELETE, which Squid forwards to an origin

server. A PURGE request asks Squid

to remove the object given in the URI. Squid returns either 200 (Ok)

or 404 (Not Found).

The PURGE method is somewhat

dangerous because it removes cached objects. Squid disables the

PURGE method unless you define an

ACL for it. Normally you should allow PURGE requests only from localhost and

perhaps a small number of trusted hosts. The configuration may look

like this:

acl AdminBoxes src 127.0.0.1 172.16.0.1 192.168.0.1 acl Purge method PURGE http_access allow AdminBoxes Purge http_access deny Purge

The squidclient program

provides an easy way to generate PURGE requests. For example:

% squidclient -m PURGE http://www.lrrr.org/junk

Alternatively, you could use something else (such as a Perl script) to generate your own HTTP request. It can be very simple:

PURGE http://www.lrrr.org/junk HTTP/1.0 Accept: */*

Note that a URI alone doesn’t uniquely identify a cached

response. Squid also uses the original request method in the cache

key. It may also use other request headers if the response contains a

Vary header. When you issue a

PURGE request, Squid looks for

cached objects originally requested with the GET and HEAD methods. Furthermore, Squid also

removes all variants of a response, unless you remove a specific

variant by including the appropriate headers in the PURGE request. Squid removes only variants

for GET and HEAD requests.

Removing a Group of Objects

Unfortunately, Squid doesn’t provide a good mechanism for removing a bunch of objects at once. This often comes up when someone wants to remove all objects belonging to a certain origin server.

Squid lacks this feature for a couple of reasons. First, Squid would have to perform a linear search through all cached objects. This is CPU-intensive and takes a long time. While Squid is searching, your users can experience a performance degradation. Second, Squid keeps MD5s, rather than URIs, in memory. MD5s are one-way hashes, which means, for example, that you can’t tell if a given MD5 hash was generated from a URI that contains the string “www.example.com.” The only way to know is to recalculate the MD5 from the original URI and see if they match. Because Squid doesn’t have the URI, it can’t perform the calculation.

So what can you do?

You can use the data in access.log to

get a list of URIs that might be in the cache. Then, feed them to

squidclient or another utility to

generate PURGE requests. For

example:

% awk '{print $7}' /usr/local/squid/var/logs/access.log \

| grep www.example.com \

| xargs -n 1 squidclient -m PURGERemoving All Objects

In extreme circumstances you may need to wipe out the entire cache, or at least one of the cache directories. First, you must make sure that Squid isn’t running.

One of the easiest ways to make Squid forget about all cached objects is to overwrite the swap.state files. Note that you can’t simply remove the swap.state files because Squid then scans the cache directories and opens all the object files. You also can’t simply truncate swap.state to a zero-sized file. Instead, you should put a single byte there, like this:

# echo '' > /usr/local/squid/var/cache/swap.state

When Squid reads the swap.state file, it gets an error because the record that should be there is too short. The next read results in an end-of-file condition, and Squid completes the rebuild procedure without loading any object metadata.

Note that this technique doesn’t remove the cache files from your disk. You’ve only tricked Squid into thinking that the cache is empty. As Squid runs, it adds new files to the cache and may overwrite the old files. In some cases, this might cause your disk to run out of free space. If that happens to you, you need to remove the old files before restarting Squid again.

One way to remove cache files is with rm. However, it often takes a very long time to remove all the files that Squid has created. To get Squid running faster, you can rename the cache directory, create a new one, start Squid, and remove the old one at the same time. For example:

# squid -k shutdown # cd /usr/local/squid/var # mv cache oldcache # mkdir cache # chown nobody:nobody cache # squid -z # squid -s # rm -rf oldcache &

Another technique is to simply run newfs (or mkfs) on the cache filesystem. This works

only if you have the cache_dir on its own

disk partition.

refresh_pattern

The refresh_pattern directive controls the disk cache only indirectly. It helps Squid decide whether or not a given request can be a cache hit or must be treated as a miss. Liberal settings increase your cache hit ratio but also increase the chance that users receive a stale response. Conservative settings, on the other hand, decrease hit ratios and stale responses.

Tip

The refresh_pattern rules apply only to

responses without an explicit expiration time. Origin servers can

specify an expiration time with either the Expires header, or the Cache-Control: max-age directive.

You can put any number of refresh_pattern lines in the configuration file. Squid searches them in order for a regular expression match. When Squid finds a match, it uses the corresponding values to determine whether a cached response is fresh or stale. The refresh_pattern syntax is as follows:

refresh_pattern [-i]regexpminpercentmax[options]

For example:

refresh_pattern -i \.jpg$ 30 50% 4320 reload-into-ims refresh_pattern -i \.png$ 30 50% 4320 reload-into-ims refresh_pattern -i \.htm$ 0 20% 1440 refresh_pattern -i \.html$ 0 20% 1440 refresh_pattern -i . 5 25% 2880

The regexp parameter is a regular

expression that is normally case-sensitive. You can make them

case-insensitive with the -i option. Squid checks the

refresh_pattern lines in order; it stops searching

when one of the regular expression patterns matches the URI.

The min parameter is some number of

minutes. It is, essentially, a lower bound on stale responses. A

response can’t be stale unless its time in the cache exceeds the minimum

value. Similarly, max is an upper limit on

fresh responses. A response can’t be fresh unless its time in the cache

is less than the maximum time.

Responses that fall between the minimum and maximum are subject to

Squid’s last-modified factor (LM-factor)

algorithm. For such responses, Squid calculates the response age and the

LM-factor and compares it to the percent

value. The response age is simply the amount of time passed since the

origin server generated, or last validated, the response. The resource

age is the difference between the Last-Modified and Date headers. The LM-factor is the ratio of

the response age to the resource age.

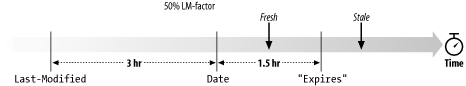

Figure 7-2 demonstrates

the LM-factor algorithm. Squid caches an object that is 3 hours old

(based on the Date and Last-Modified headers). With an LM-factor

value of 50%, the response will be fresh for the next 1.5 hours, after

which the object expires and is considered stale. If a user requests the

cached object during the fresh period, Squid returns an unvalidated

cache hit. For a request that occurs during the stale period, Squid

forwards a validation request to the origin server.

It’s important to understand the order that Squid checks the various values. Here is a simplified description of Squid’s refresh_pattern algorithm:

The response is stale if the response age is greater than the refresh_pattern

maxvalue.The response is fresh if the LM-factor is less than the refresh_pattern

percentvalue.The response is fresh if the response age is less than the refresh_pattern

minvalue.Otherwise, the response is stale.

The refresh_pattern directive also has a handful of options that cause Squid to disobey the HTTP protocol specification. They are as follows:

- override-expire

When set, this option causes Squid to check the

minvalue before checking theExpiresheader. Thus, a non-zeromintime makes Squid return an unvalidated cache hit even if the response is preexpired.- override-lastmod

When set, this option causes Squid to check the

minvalue before the LM-factor percentage.- reload-into-ims

When set, this option makes Squid transform a request with a

no-cachedirective into a validation (If-Modified-Since) request. In other words, Squid adds anIf-Modified-Sinceheader to the request before forwarding it on. Note that this only works for objects that have aLast-Modifiedtimestamp. The outbound request retains theno-cachedirective, so that it reaches the origin server.- ignore-reload

When set, this option causes Squid to ignore the

no-cachedirective, if any, in the request.

Exercises

Run

dfon your existing filesystems and calculate the ratio of inodes to disk space. If any of those partitions are used for Squid’s disk cache, do you think you’ll run out of space, or inodes first?Try to intentionally make Squid run out of disk space on a cache directory. How does Squid deal with this situation?

Write a shell script to search the cache for given URIs and optionally remove them.

Examine Squid’s store.log and estimate the percentage of requests that are subject to the refresh_pattern rules.

Can you think of any negative side effects of the

ignore-reload,override-expire, and related options?