13

TLS

The Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol, also known as Secure Socket Layer (SSL), which is the name of its predecessor, is the workhorse of internet security. TLS protects connections between servers and clients, whether that connection is between a website and its visitors, email servers, a mobile application and its servers, or video game servers and players. Without TLS, there would be no secure online commerce, secure online banking, or for that matter secure online anything.

TLS is application agnostic; it doesn’t care about the type of content encrypted. This means that you can use it for web-based applications that rely on the HTTP protocol, as well as for any system where a client computer or device needs to initiate a connection with a remote server. For example, TLS is widely used for machine-to-machine communications in so-called internet of things (IoT) applications.

This chapter provides you with an abbreviated view of TLS. As you’ll see, TLS has become increasingly complex over the years. Unfortunately, complexity and bloat brought multiple vulnerabilities, and bugs found in its cluttered implementations have made headlines—think Heartbleed, BEAST, CRIME, and POODLE, all vulnerabilities that impacted millions of web servers.

In 2013, engineers tired of fixing new cryptographic vulnerabilities in TLS overhauled it and started working on TLS 1.3. As you’ll learn in this chapter, TLS 1.3 ditched unnecessary features and insecure ones, and replaced old algorithms with state-of-the-art ciphers. The result is a simpler, faster, and more secure protocol.

But before we explore how TLS 1.3 works, let’s review the problem that TLS aims to solve in the first place, and the reason for its very existence.

Target Applications and Requirements

TLS is best known for being the S in HTTPS websites, and the padlock in a browser’s address bar indicating that a page is secure. The primary driver for creating TLS was to enable secure browsing in applications such as e-commerce or e-banking by encrypting website connections to protect credit card numbers, user credentials, and other sensitive information.

TLS also helps to protect internet-based communication in general by establishing a secure channel between a client and a server that ensures the data transferred is confidential, authenticated, and unmodified.

One of TLS’s security goals is to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks, wherein an attacker intercepts encrypted traffic from the transmitting party, decrypts the traffic to capture the clear content, and re-encrypts it to send to the receiving party. TLS defeats man-in-the-middle attacks by authenticating servers (and optionally clients) using certificates and trusted certificate authorities, as we’ll discuss in more detail in the section “Certificates and Certificate Authorities” on page 238.

To ensure wide adoption, TLS needed to satisfy four more requirements: it needed to be efficient, interoperable, extensible, and versatile.

For TLS, efficiency means minimizing the performance penalty compared with unencrypted connections. This is good for both the server (to reduce the cost of hardware for the service providers) and for clients (to avoid perceptible delays or the reduction of mobile devices’ battery life). The protocol needed to be interoperable so that it would work on any hardware and any operating system. It was to be extensible so that it could support additional features or algorithms. And it had to be versatile—that is, not bound to a specific application (this parallels something like Transport Control Protocol, which doesn’t care about the application protocol used on top of it).

The TLS Protocol Suite

To protect client–server communications, TLS is made up of multiple versions of several protocols that together form the TLS protocol suite. And although TLS stands for Transport Layer Security, it’s actually not a transport protocol. TLS usually sits between the transport protocol TCP and an application layer protocol such as HTTP or SMTP, in order to secure data transmitted over a TCP connection.

TLS can also work over the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) transport protocol, which is used for “connectionless” transmissions such as voice or video traffic. However, unlike TCP, UDP doesn’t guarantee delivery or correct packet ordering. The UDP version of TLS is therefore slightly different and is called DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security). For more on TCP and UDP, see Charles Kozierok’s The TCP/IP Guide (No Starch Press, 2005.)

The TLS and SSL Family of Protocols: A Brief History

TLS began life in 1995 when Netscape, developer of the Netscape browser, developed TLS’s ancestor, the Secure Socket Layer (SSL) protocol. SSL was far from perfect, and both SSL 2.0 and SSL 3.0 had security flaws. The upshot is that you should never use SSL, you should always use TLS—what adds to the confusion is that TLS is often referred to as “SSL,” even by security experts.

Moreover, not all versions of TLS are secure. TLS 1.0 (1999) is the least secure TLS version, though it’s still more secure than SSL 3.0. TLS 1.1 (2006) is better but includes a number of algorithms known today to be weak. TLS 1.2 (2008) is better yet, but it’s complex and only gets you high security if configured correctly (which is no simple matter). Also, its complexity increases the risk of bugs in implementations and the risk of incorrect configurations. For example, TLS 1.2 supports AES in CBC mode, which is often vulnerable to padding oracle attacks.

TLS 1.2 inherited dozens of features and design choices from earlier versions of TLS that make it suboptimal, both in terms of security and performance. To clean up this mess, cryptography engineers reinvented TLS—keeping only the good parts and adding security features. The result is TLS 1.3, an overhaul that has simplified a bloated design and made it more secure, more efficient, and simpler. Essentially, TLS 1.3 is mature TLS.

TLS in a Nutshell

TLS has two main protocols: one determines how to transmit data, and the other what data to transmit. The record protocol defines a packet format to encapsulate data from higher-level protocols and sends this data to another party. It’s a simple protocol that people often forget is part of TLS.

The handshake protocol—or just handshake—is TLS’s key agreement protocol. It’s often mistaken for “the” TLS protocol but the record protocol and the handshake can’t be separated.

The handshake is started by a client to initiate a secure connection with a server. The client sends an initial message called ClientHello with parameters that include the cipher it wants to use. The server checks this message and its parameters and then responds with a message called ServerHello. Once both the client and the server have processed each other’s messages, they’re ready to exchange encrypted data using session keys established through the handshake protocol, as you’ll see in the section “The TLS Handshake Protocol” on page 241.

Certificates and Certificate Authorities

The most critical step in the TLS handshake, and the crux of TLS’s security, is the certificate validation step, wherein a server uses a certificate to authenticate itself to a client.

A certificate is essentially a public key accompanied by a signature of that key and associated information (including the domain name). For example, when connecting to https://www.google.com/, your browser will receive a certificate from some network host and will then verify the certificate’s signature, which reads something like “I am google.com and my public key is [key].” If the signature is verified, the certificate (and its public key) are said to be trusted, and the browser can proceed with establishing the connection. (See Chapters 10 and 12 for details about signatures.)

How does the browser know the public key needed to verify the signature? That’s where the concept of certificate authority (CA) comes in. A CA is essentially a public key hard coded in your browser or operating system. The public key’s private key (that is, its signing capability) belongs to a trusted organization that ensures the public keys in certificates that it issues belong to the website or entity that claims them. That is, a CA acts as a trusted third party. Without CAs, there would be no way to verify that the public key served by google.com belongs to Google and not to an eavesdropper performing a man-in-the-middle attack.

For example, the command shown in Listing 13-1 shows what happens when we use the OpenSSL command-line tool to initiate a TLS connection to www.google.com on port 443, the network port used for TLS-based HTTP connections (that is, HTTPS.):

$ openssl s_client -connect www.google.com:443

CONNECTED(00000003)

--snip--

---

Certificate chain

❶ 0 s:/C=US/ST=California/L=Mountain View/O=Google Inc/CN=www.google.com

i:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2

❷ 1 s:/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2

i:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA

❸ 2 s:/C=US/O=GeoTrust Inc./CN=GeoTrust Global CA

i:/C=US/O=Equifax/OU=Equifax Secure Certificate Authority

---

Server certificate

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIEgDCCA2igAwIBAgIISCr6QCbz5rowDQYJKoZIhvcNAQELBQAwSTELMAkGA1UE

BhMCVVMxEzARBgNVBAoTCkdvb2dsZSBJbmMxJTAjBgNVBAMTHEdvb2dsZSBJbnRl

--snip--

cb9reU8in8yCaH8dtzrFyUracpMureWnBeajOYXRPTdCFccejAh/xyH5SKDOOZ4v

3TP9GBtClAH1mSXoPhX73dp7jipZqgbY4kiEDNx+hformTUFBDHD0eO/s2nqwuWL

pBH6XQ==

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

subject=/C=US/ST=California/L=Mountain View/O=Google Inc/CN=www.google.com

issuer=/C=US/O=Google Inc/CN=Google Internet Authority G2

--snip--

Listing 13-1: Establishing a TLS connection with www.google.com and receiving certificates to authenticate the connection

I’ve trimmed the output to show only the interesting part, which is the certificate. Notice that before the first certificate (which starts with the BEGIN CERTIFICATE tag) is a description of the certificate chain, where the line starting with s: describes the subject name and the line starting with i: describes the issuer of the signature. Here, certificate 0 is the one received by google.com ❶, certificate 1 ❷ belongs to the entity that signed certificate 0, and certificate 2 ❸ belongs to the entity that signed certificate 1. The organization that issued certificate 2 (GeoTrust) granted permission to Google Internet Authority to issue a certificate (certificate 1) for the domain name www.google.com, thereby transferring trust to Google Internet Authority.

Obviously, these CA organizations must be trustworthy and only issue certificates to trustworthy entities, and they must protect their private keys in order to prevent an attacker from issuing certificates on their behalf (for example, in order to impersonate a legitimate google.com server).

To see what’s in a certificate, we enter the command shown in Listing 13-2 into a Linux terminal and then paste the first certificate shown in Listing 13-1.

$ openssl x509 –text –noout

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

--snip--

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number: 5200243873191028410 (0x482afa4026f3e6ba)

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C=US, O=Google Inc, CN=Google Internet Authority G2

Validity

Not Before: Dec 15 14:07:56 2016 GMT

Not After : Mar 9 13:35:00 2017 GMT

Subject: C=US, ST=California, L=Mountain View, O=Google Inc, CN=www.google.com

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

Public-Key: (2048 bit)

Modulus:

00:bc:bc:b2:f3:1a:16:3b:c6:f6:9d:28:e1:ef:8e:

92:9b:13:b2:ae:7b:50:8f:f0:b4:e0:36:8d:09:00:

--snip--

8f:e6:96:fe:41:41:85:9d:a9:10:9a:09:6e:fc:bd:

43:fa:4d:c6:a3:55:9a:9e:07:8b:f9:b1:1e:ce:d1:

22:49

Exponent: 65537 (0x10001)

--snip--

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

94:cd:66:55:83:f1:16:7d:46:d8:66:21:06:ec:c6:9d:7c:1c:

2b:c1:f6:4f:b7:3e:cd:01:ad:69:bd:a1:81:6a:7c:96:f5:9c:

--snip--

85:fa:2b:99:35:05:04:31:c3:d1:e3:bf:b3:69:ea:c2:e5:8b:

a4:11:fa:5d

Listing 13-2: Decoding a certificate received from www.google.com

What you see in Listing 13-2 is the command openssl x509 decoding a certificate, originally provided as a block of base64-encoded data. Because OpenSSL knows how this block of data is structured, it can tell us what’s inside the certificate, including a serial number and version information, identifying information, validity dates (the Not Before and Not After lines), a public key (here as an RSA modulus and its public exponent), and a signature of the preceding information.

Although security experts and cryptographers often claim the whole certificate system is broken by design, it’s one of the best solutions we have, along with the trust-on-first-use (TOFU) policy adopted by SSH, for example.

The Record Protocol

All data exchanged through TLS 1.3 communications is transmitted as sequences of TLS records, the data packets used by TLS. The TLS record protocol (the record layer) is essentially a transport protocol, agnostic of the transported data’s meaning; this is what makes TLS suitable for any application.

The TLS record protocol is first used to carry the data exchanged during the handshake. Once the handshake is complete and both parties share a secret key, application data is fragmented into chunks that are transmitted as part of the TLS records.

Structure of a TLS Record

A TLS record is a chunk of data of at most 16 kilobytes, structured as follows:

- The first byte represents the type of data transmitted and is set to the value 22 for handshake data, 23 for encrypted data, and 21 for alerts. In the TLS 1.3 specifications, this value is called ContentType.

- The second and third byte are set to 3 and 1, respectively. These bytes are fixed for historical reasons and are not unique to TLS version 1.3. In the specifications, this 2-byte value is called ProtocolVersion.

- The fourth and fifth bytes encode the length of the data to transmit as a 16-bit integer, which can be no larger than 214 bytes (16KB).

- The rest of the bytes are the data to transmit (also called the payload), of a length equal to the value encoded by the record’s fourth and fifth bytes.

NOTE

A TLS record has a relatively simple structure. As we’ve seen, a TLS record’s header includes only three fields. For comparison, an IPv4 packet includes 14 fields before its payload and a TCP segment includes 13 fields.

When the first byte of a TLS 1.3 record (ContentType) is set to 23, its payload is encrypted and authenticated using an authenticated cipher. The payload consists of a ciphertext followed by an authentication tag, which the receiving end will decrypt. But then how does the recipient know which cipher and key to decrypt with? That’s the magic of TLS: if you receive an encrypted TLS record, you already know the cipher and key, because they are established when the TLS handshake protocol is executed.

Nonces

Unlike many other protocols such as IPsec’s Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP), TLS records don’t specify the nonce to be used by the authenticated cipher.

The nonces used to encrypt and decrypt TLS records are derived from 64-bit sequence numbers, maintained locally by each party, and incremented for each new record. When the client encrypts data, it derives a nonce by XORing the sequence number with a value called client_write_iv, itself derived from the shared secret. The server uses a similar method but with a different value, called server_write_iv.

For example, if you transmit three TLS records, you’ll derive a nonce from 0 for the first record, from 1 for the second, and from 2 for the third; if you then receive three records, you’ll also use nonces 0, 1, and 2, in this order. Reuse of the same sequence numbers values for encrypting transmitted data and decrypting receiving data isn’t a weakness because they are XORed with different constants (client_write_iv and server_write_iv) and because you use different secret keys for each direction.

Zero Padding

TLS 1.3 records support a nice feature known as zero padding that mitigates traffic analysis attacks. Traffic analysis is a method that attackers use to extract information from traffic patterns using timing, volume of data transferred, and so on. For example, because ciphertexts are approximately the same size as plaintexts, even when strong encryption is used, attackers can determine the approximate size of your messages simply by looking at the length of their ciphertext.

Zero padding adds zeros to the plaintext in order to inflate the ciphertext’s size, and thus to fool observers into thinking that an encrypted message is longer than it really is.

The TLS Handshake Protocol

The handshake is the key TLS agreement protocol—the process by which a client and server establish shared secret keys in order to initiate secure communications. During the course of a TLS handshake, the client and server play different roles. The client proposes some configurations (the TLS version and a suite of ciphers, in order of preference) and the server chooses the configuration to be used. The server should follow the client’s preferences, but it may do otherwise. In order to ensure interoperability between implementations and to guarantee that any server implementing TLS 1.3 will be able to read TLS 1.3 data sent by any client implementing TLS 1.3 (even if it’s using a different library or programming language), the TLS 1.3 specifications also describe the format in which data should be sent.

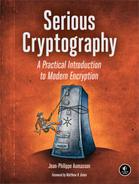

Figure 13-1 shows how data is exchanged in the handshake process, as described in the TLS 1.3 specifications. As you can see, in the TLS 1.3 handshake, the client sends a message to the server saying, “I want to establish a TLS connection with you. Here are the ciphers that I support to encrypt TLS records, and here is a Diffie–Hellman public key.” The public key must be generated specifically for this TLS session, and the client keeps the associated private key. The message sent by the client also includes a 32-byte random value and optional information (additional parameters and such). This first message is called ClientHello, and it must follow a specific format when transmitted as a series of bytes, as defined in the TLS 1.3 specification.

Figure 13-1: The TLS 1.3 handshake process when connecting to HTTPS websites

But note that the specifications also describe in what format data should be sent, in order to ensure interoperability between implementations by guaranteeing that any server implementing TLS 1.3 will be able to read TLS 1.3 data sent by any client implementing TLS 1.3, possibly using a different library or programming language.

The server receives the ClientHello message, verifies that it’s correctly formatted, and responds with a message called ServerHello. The ServerHello message is loaded with information: it contains the cipher to be used to encrypt TLS records, a Diffie–Hellman public key, a 32-byte random value (discussed in “Downgrade Protection” on page 244), a certificate, a signature of all the previous information in ClientHello and ServerHello messages (computed using the private key associated with the certificate’s public key), a MAC of that same information plus the signature. The MAC is computed using a symmetric key derived from the Diffie–Hellman shared secret, which the server computes from its Diffie–Hellman private key and the client’s public key.

When the client receives the ServerHello message, it verifies the certificate’s validity, verifies the signature, computes the shared Diffie–Hellman secret and derives symmetric keys from it, and verifies the MAC sent by the server. Once everything has been verified, the client is ready to send encrypted messages to the server.

Note, however, that TLS 1.3 supports many options and extensions, so it may behave differently than what has been described here (and shown in Figure 13-1). You can, for example, configure the TLS 1.3 handshake to require a client certificate so that the server verifies the identity of the client. TLS 1.3 also supports a handshake with pre-shared keys.

NOTE

TLS 1.3 supports many options and extensions, so it may behave differently than what has been described here (and shown in Figure 13-1). You can, for example, configure the TLS 1.3 handshake to require a client certificate so that the server verifies the identity of the client. TLS 1.3 also supports a handshake with pre-shared keys.

Let’s look at this in practice. Say you’ve deployed TLS 1.3 to provide secure access to the website https://www.nostarch.com/. When you point your browser (the client) to this site, your browser sends a ClientHello message to the site’s server that includes the ciphers that it supports. The website responds with a ServerHello message and a certificate that includes a public key associated with the domain www.nostarch.com. The client verifies the certificate’s validity using one of the certificate authorities embedded in the browser (the received certificate should be signed by a trusted certificate authority, whose certificate should be included in the browser’s certificate store in order to be validated). Once all checks are passed, the browser requests the site’s initial page from the www.nostarch.com server.

Upon a successful TLS 1.3 handshake, all communications between the client and the server are encrypted and authenticated. An eavesdropper can learn that a client at a given IP address is talking to a server at another given IP address, and can observe the encrypted content exchanged, but won’t be able to learn the underlying plaintext or modify the encrypted messages (if they do, the receiving party will notice that the communication has been tampered with, because messages are not only encrypted but also authenticated). That’s enough security for many applications.

TLS 1.3 Cryptographic Algorithms

We know that TLS 1.3 uses authenticated encryption algorithms, a key derivation function (a hash function that derives secret keys from a shared secret), as well as a Diffie–Hellman operation. But how exactly do these work, what algorithms are used, and how secure are they?

With regard to the choice of authenticated ciphers, TLS 1.3 supports only three algorithms: AES-GCM, AES-CCM (a slightly less efficient mode than GCM), and the ChaCha20 stream cipher combined with the Poly1305 MAC (as defined in RFC 7539). Because TLS 1.3 prevents you from using an unsafe key length such as 64 or 80 bits (which are both too short), the secret key can be either 128 bits (AES-GCM or AES-CCM) or 256 bits (AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305).

The key derivation operation (KDF) in Figure 13-1 is based on HKDF, a construction based on HMAC (discussed in Chapter 7) and defined in RFC 5869 that uses either the SHA-256 or the SHA-384 hash function.

Your options for performing the Diffie–Hellman operation (the core of the TLS 1.3 handshake) are limited to elliptic curve cryptography and a multiplicative group of integers modulo a prime number (as in traditional Diffie–Hellman). But you can’t use just any elliptic curve or group: the supported curves include three NIST curves as well as Curve25519 (discussed in Chapter 12) and Curve448, both defined in RFC 7748. TLS 1.3 also supports DH over groups of integers, as opposed to elliptic curves. The groups supported are the five groups defined in RFC 7919: groups of 2048, 3072, 4096, 6144, and 8192 bits.

The 2048-bit group may be TLS 1.3’s weakest link. Whereas the other options provide at least 128-bit security, 2048-bit Diffie–Hellman is believed to provide less than 100-bit security. Supporting a 2048-bit group can therefore be seen as inconsistent with other TLS 1.3 design choices.

TLS 1.3 Improvements over TLS 1.2

TLS 1.3 is very different from its predecessor. For one thing, it gets rid of weak algorithms like MD5, SHA-1, RC4, and AES in CBC mode. Also, whereas TLS 1.2 often protected records using a combination of a cipher and a MAC (such as HMAC-SHA-1) within a MAC-then-encrypt construction, TLS 1.3 only supports the more efficient and more secure authenticated ciphers. TLS 1.3 also ditches elliptic curve point encoding negotiation, and defines a single point format for each curve.

One of the main development goals of TLS 1.3 was to remove features in 1.2 that weakened the protocol and to reduce the protocol’s overall complexity and thereby its attack surface. For example, TLS 1.3 ditches optional data compression, a feature that enabled the CRIME attack on TLS 1.2. This attack exploited the fact that the length of the compressed version of a message leaks information on the content of the message.

But TLS 1.3 also brings new features that make connections either more secure or more efficient. I’ll discuss three of these features briefly: downgrade protection, the single round-trip handshake, and session resumption.

Downgrade Protection

TLS 1.3’s downgrade protection feature is designed as a defense against downgrade attacks, wherein an attacker forces the client and server to use a weaker version of TLS than 1.3. To carry out a downgrade attack, an attacker forces the server to use a weaker version of TLS by intercepting and modifying the ClientHello message to tell the server that the client doesn’t support TLS 1.3. Now the attacker can exploit vulnerabilities in earlier versions of TLS.

In an effort to defeat downgrade attacks, the TLS 1.3 server uses three types of patterns in the 32-byte random value sent within the ServerHello message to identify the type of connection requested. The pattern should match the client’s request for a specific type of TLS connection. If the client receives the wrong pattern, it knows that something is up.

Specifically, if the client asks for a TLS 1.2 connection, the first eight of the 32 bytes are set to 44 4F 57 4E 47 52 44 01, and if it asks for a TLS 1.1 connection, they’re set to 44 4F 57 4E 47 52 44 00. However, if the client requests a TLS 1.3 connection, these first eight bits should be random. For example, if a client sends a ClientHello asking for a TLS 1.3 connection, but an attacker on the network modifies it to ask for a TLS 1.1 connection, when the client receives the ServerHello with the wrong pattern, it will know that its ClientHello message was modified. (The attacker can’t arbitrarily modify the server’s 32-byte random value because this value is cryptographically signed.)

Single Round-Trip Handshake

In a typical TLS 1.2 handshake, the client sends some data to the server, waits for a response, and then sends more data and waits for the server’s response before sending encrypted messages. The delay is that of two round-trip times (RTT). In contrast, TLS 1.3’s handshake takes a single round-trip time, as shown in Figure 13-1. The time saved can be in the hundreds of milliseconds. That may sound small, but its actually significant when you consider that servers of popular services handle thousands of connections per second.

Session Resumption

TLS 1.3 is faster than 1.2, but it can be made even faster (on the order of hundreds of milliseconds) by completely eliminating the round trips that precede an encrypted session. The trick is to use session resumption, a method that leverages the pre-shared key exchanged between the client and server in a previous session to bootstrap a new session. Session resumption brings two major benefits: the client can start encrypting immediately, and there is no need to use certificates in these subsequent sessions.

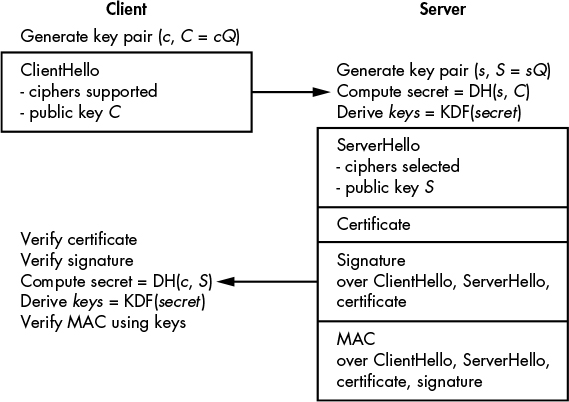

Figure 13-2 shows how session resumption works. First, the client sends a ClientHello message that includes the identifier of the key already shared (denoted PSK for pre-shared key) with the server, along with a fresh DH public key. The client can also include encrypted data in this first message (such data is known as 0-RTT data). When the server responds to a ClientHello message, it provides a MAC over the data exchange. The client verifies the MAC and knows that it’s talking to the same server as it did previously, thus rendering certificate validation somewhat superfluous. The client and the server perform a Diffie–Hellman key agreement as in the normal handshake, and subsequent messages are encrypted using keys that depend on both the PSK and the newly computed Diffie–Hellman shared secret.

Figure 13-2: The TLS 1.3 session resumption handshake. The 0-RTT data is the session resumption data sent along with the ClientHello.

The Strengths of TLS Security

We’ll evaluate the strengths of TLS 1.3 with respect to two main security notions discussed in Chapter 11: authentication and forward secrecy.

Authentication

During the TLS 1.3 handshake, the server authenticates to the client using the certificate mechanism. However, the client is not authenticated, and clients may authenticate with a server-based application (such as Gmail) by providing a username and password in a TLS record after performing the handshake. If the client has already established a session with the remote service, it may authenticate by sending a secure cookie, one that can only be sent through a TLS connection.

In certain cases, clients can authenticate to a server using a certificate-based mechanism similar to what the server uses in order to authenticate to the client: the client sends a client certificate to the server, which in turn verifies this certificate before authorizing the client. However, client certificates are rarely used because they complicate things for both clients and the server (that is, the certificate issuer): clients need to perform complex operations in order to integrate the certificate into their system and to protect its private key, while the issuer needs to make sure that only authorized clients received a certificate, among other requirements.

Forward Secrecy

Recall from “Key Agreement Protocols” on page 205 that a key agreement is said to provide forward secrecy if previous sessions aren’t compromised when the present session is compromised. In the data leak model, only temporary secrets are compromised, whereas in the breach model, long-term secrets are exposed.

Thankfully, TLS 1.3 forward secrecy holds up in the face of both a data leak and a breach. In the case of the data leak model, the attacker recovers temporary secrets such as the session keys or Diffie–Hellman private keys of a specific session (the values c, s, secret, and keys in Figure 13-1 on page 242). However, they can only use these values to decrypt communications from the present session, but not from previous sessions, because different values of c and s were used (thus yielding different keys).

In the breach model, the attacker also recovers long-term secrets (namely, the private key that corresponds to the public key in the certificate). However, this is no more useful when decrypting previous sessions than temporary secrets, because this private key only serves to authenticate the server, and forward secrecy holds up again.

But what happens in practice? Say an attacker compromises a client’s machine and gains access to all of its memory. Now the attacker may recover the client’s TLS session keys and secrets for the current session from memory. But more importantly, if previous keys are still in memory, the attacker may be able to find them too and use them to decrypt previous sessions, thereby bypassing the theoretical forward secrecy. Therefore, in order for a TLS implementation to ensure forward secrecy, it must properly erase keys from memory once they are no longer used, typically by zeroing out the memory.

How Things Can Go Wrong

TLS 1.3 fits the bill as a general-purpose secure communications protocol, but it’s not bulletproof. Like any security system, it can fail under certain circumstances (for example, when the assumptions made by its designers about real attacks turn out to be wrong). Unfortunately, even the latest version of TLS 1.3, configured with the most secure ciphers, can still be compromised. For example, TLS 1.3 security relies on the assumption that all three parties (the client, the server, and the certificate authority) will behave honestly, but what if one party is compromised or the TLS implementation itself is poorly implemented?

Compromised Certificate Authority

Root certificate authorities (root CAs) are organizations that are trusted by browsers to validate certificates served by remote hosts. For example, if your browser accepts the certificate provided by www.google.com, the assumption is that a trusted CA has verified the legitimacy of the certificate owner. The browser verifies the certificate by checking its CA-issued signature. Since only the CA knows the private key required to create this signature, we assume that others can’t create valid certificates on behalf of the CA. Very often a website’s certificate won’t be signed by a root CA but by an intermediate CA, which is connected to the root CA through a certificate chain.

But let’s say that a CA’s private key is compromised. Now the attacker will be able to use the CA’s private key to create a certificate for any URLs in, say, the google.com domain without Google’s approval. What happens then? The attacker can use those certificates to pretend to host a legitimate server or subdomain like mail.google.com and intercept a user’s credentials and communications. That’s exactly what happened in 2011 when an attacker hacked into the network of the Dutch certificate authority DigiNotar and was able to create certificates that appeared to have been legitimate DigiNotar certificates. The attacker then used these fake certificates for several Google services.

Compromised Server

If a server is compromised and fully controlled by an attacker, all is lost: the attacker will be able to see all transmitted data before it’s encrypted, and all received data once it has been decrypted. They will also be able to get their hands on the server’s private key, which could allow them to impersonate the legitimate server using their own malicious server. Obviously, TLS won’t save you in this case.

Fortunately, such security disasters are rarely seen in high-profile applications such as Gmail and iCloud, which are well protected and sometimes have their private keys stored in a separate security module. Attacks on web applications via vulnerabilities such as database query injections and cross-site scripting are more common, because they are mostly independent of TLS’s security and are carried out by attackers over a legitimate TLS connection. Such attacks may compromise usernames, passwords, and so on.

Compromised Client

TLS security is also compromised when a client, such as a browser, is compromised by a remote attacker. Having compromised the client, the attacker will be able to capture session keys, read any decrypted data, and so on. They could even install a rogue CA certificate in the client’s browser to have it silently accept otherwise invalid certificates, thereby letting attackers intercept TLS connections.

The big difference between the compromised CA or server scenarios and the compromised client scenario is that in the case of the compromised client, only the targeted client will be affected, instead of potentially all the clients.

Bugs in Implementations

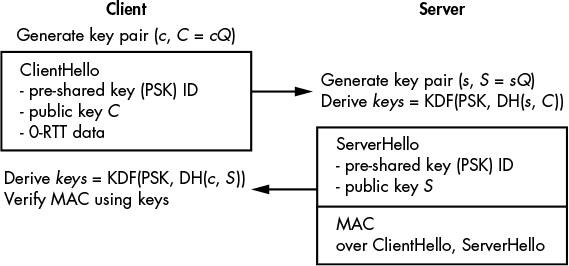

As with any cryptographic system, TLS can fail when there are bugs in its implementation. The poster child for TLS bugs is Heartbleed (see Figure 13-3), a buffer overflow in the OpenSSL implementation of a minor TLS feature known as heartbeat. Heartbleed was discovered in 2014, independently by a Google researcher and by the Codenomicon company, and affected millions of TLS servers and clients.

As you can see in Figure 13-3, a client first sends a buffer along with a buffer length to the server to check whether the server is online. In this example, the buffer is the string BANANAS, and the client explicitly says that this word is seven letters long. The server reads the seven-letter word and returns it to the client.

Figure 13-3: The Heartbleed bug in OpenSSL implementations of TLS

The problem is that the server doesn’t confirm that the length is correct, and will attempt to read as many characters as the client tells it to. Consequently, if the client provides a length that is longer than the string’s actual length, the server reads too much data from memory and will return it to the client, together with any extra data that may contain sensitive information, such as private keys or session cookies.

It won’t surprise you to hear that the Heartbleed bug came as a shock. To avoid similar future bugs, OpenSSL and other major TLS implementations now perform rigorous code reviews and use automated tools such as fuzzers in order to identify potential issues.

Further Reading

As I stated at the outset, this chapter is not a comprehensive guide to TLS, and you may want to dig deeper into TLS 1.3. For starters, the complete TLS 1.3 specifications include everything about the protocol (though not necessarily about its underlying rationale). You can find that on the home page of the TLS Working Group (TLSWG) here: https://tlswg.github.io/.

In addition, let me cite two important TLS initiatives:

- SSL Labs TLS test (https://www.ssllabs.com/ssltest/) is a free service by Qualys that lets you test a browser’s or a server’s TLS configuration, providing a security rating as well as improvement suggestions. If you set up your own TLS server, use this test to make sure that everything is safe and that you get an “A” rating.

- Let’s Encrypt (https://letsencrypt.org/) is a nonprofit that offers a service to “automagically” deploy TLS on your HTTP servers. It includes features to automatically generate a certificate and configure the TLS server, and it supports all the common web servers and operating systems.