8

AUTHENTICATED ENCRYPTION

This chapter is about a type of algorithm that protects not only a message’s confidentiality but also its authenticity. Recall from Chapter 7 that message authentication codes (MACs) are algorithms that protect a message’s authenticity by creating a tag, which is a kind of signature. Like MACs, the authenticated encryption (AE) algorithms we’ll discuss in this chapter produce an authentication tag, but they also encrypt the message. In other words, a single AE algorithm offers the features of both a normal cipher and a MAC.

Combining a cipher and a MAC can achieve varying levels of authenticated encryption, as you’ll learn throughout this chapter. I’ll review several possible ways to combine MACs with ciphers, explain which methods are the most secure, and introduce you to ciphers that produce both a ciphertext and an authentication tag. We’ll then look at four important authenticated ciphers: three block cipher–based constructions, with a focus on the popular Advanced Encryption Standard in Galois Counter Mode (AES-GCM), and a cipher that uses only a permutation algorithm.

Authenticated Encryption Using MACs

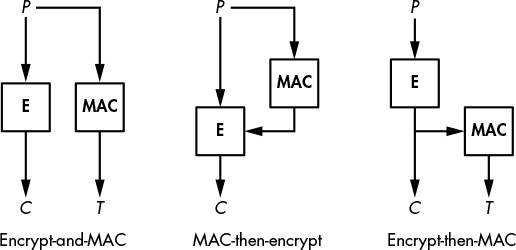

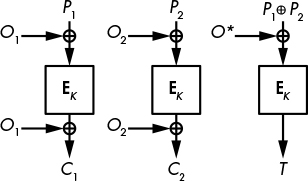

As shown in Figure 8-1, MACs and ciphers can be combined in one of three ways to both encrypt and authenticate a plaintext: encrypt-and-MAC, MAC-then-encrypt, and encrypt-then-MAC.

Figure 8-1: Cipher and MAC combinations

The three combinations differ in the order in which encryption is applied and the authentication tag is generated. However, the choice of a specific MAC or cipher algorithm is unimportant as long as each is secure in its own right, and the MAC and cipher use distinct keys.

As you can see in Figure 8-1, in the encrypt-and-MAC composition, the plaintext is encrypted and an authentication tag is generated from the plaintext directly, such that the two operations (encryption and authentication) are independent of each other and can therefore be computed in parallel. In the MAC-then-encrypt scheme, the tag is generated from the plaintext first, and then the plaintext and MAC are encrypted together. In contrast, in the case of the encrypt-then-MAC method, the plaintext is encrypted first, and then the tag is generated from the ciphertext.

All three approaches are about equally resource intensive. Let’s see which method is likely to be the most secure.

Encrypt-and-MAC

The encrypt-and-MAC approach computes a ciphertext and a MAC tag separately. Given a plaintext (P), the sender computes a ciphertext C = E(K1, P), where E is an encryption algorithm and C is the resulting ciphertext. The authentication tag (T) is calculated from the plaintext as T = MAC(K2, P). You can compute C and T first or in parallel.

Once the ciphertext and authentication tag have been generated, the sender transmits both to the intended recipient. When the recipient receives C and T, they decrypt C to obtain the plaintext P by computing P = D(K1, C). Next, they compute MAC(K2, P) using the decrypted plaintext and compare the result to the T received. This verification will fail if either C or T was corrupted, and the message will be deemed invalid.

At least in theory, encrypt-and-MAC is the least secure MAC and cipher composition because even a secure MAC could leak information on P, which would make P easier to recover. Because the goal of using MACs is simply to make tags unforgeable, and because tags aren’t necessarily random looking, the authentication tag (T) of a plaintext (P) could still leak information even though the MAC is considered secure! (Of course, if the MAC is a pseudorandom function, the tag won’t leak anything on P.)

Still, despite its relative weakness, encrypt-and-MAC continues to be supported by many systems, including the secure transport layer protocol SSH, wherein each encrypted packet C is followed by the tag T = MAC(K, N || P) sent in the unencrypted plaintext packet P. N in this equation is a 32-bit sequence number that is incremented for each sent packet, in order to help ensure that the received packets are processed in the right order. In practice, encrypt-and-MAC has proven good enough for use with SSH, thanks to the use of strong MAC algorithms like HMAC-SHA-256 that don’t leak information on P.

MAC-then-Encrypt

The MAC-then-encrypt composition protects a message, P, by first computing the authentication tag T = MAC(K2, P). Next, it creates the ciphertext by encrypting the plaintext and tag together, according to C = E(K1, P || T).

Once these steps have been completed, the sender transmits only C, which contains both the encrypted plaintext and tag. Upon receipt, the recipient decrypts C by computing P || T = D(K1, C) to obtain the plaintext and tag T. Next, the recipient verifies the received tag T by computing a tag directly from the plaintext according to MAC(K2, P) in order to confirm that the computed tag is equal to the tag T.

As with encrypt-and-MAC, when MAC-then-encrypt is used, the recipient must decrypt C before they can determine whether they are receiving corrupted packets—a process that exposes potentially corrupted plaintexts to the receiver. Nevertheless, MAC-then-encrypt is more secure than encrypt-and-MAC because it hides the plaintext’s authentication tag, thus preventing the tag from leaking information on the plaintext.

MAC-then-encrypt has been used in the TLS protocol for years, but TLS 1.3 replaced MAC-then-encrypt with authenticated ciphers (see Chapter 13 for more on TLS 1.3).

Encrypt-then-MAC

The encrypt-then-MAC composition sends two values to the recipient: the ciphertext produced by C = E(K1, P) and a tag based on the ciphertext, T = MAC(K2, C). The receiver computes the tag using MAC(K2, C) and verifies that it equals the T received. If the values are equal, the plaintext is computed as P = D(K1, C); if they are not equal, the plaintext is discarded.

One advantage with this method is that the receiver only needs to compute a MAC in order to detect corrupt messages, meaning that there is no need to decrypt a corrupt ciphertext. Another advantage is that attackers can’t send pairs of C and T to the receiver to decrypt unless they have broken the MAC, which makes it harder for attackers to transmit malicious data to the recipient.

This combination of features makes encrypt-then-MAC stronger than the encrypt-and-MAC and MAC-then-encrypt approaches. This is one reason why the widely used IPSec secure communications protocol suite uses it to protect packets (for example, within VPN tunnels).

But then why don’t SSH and TLS use encrypt-then-MAC? The simple answer is that when SSH and TLS were created, other approaches appeared adequate—not because theoretical weaknesses didn’t exist but because theoretical weaknesses don’t necessarily become actual vulnerabilities.

Authenticated Ciphers

Authenticated ciphers are an alternative to the cipher and MAC combinations. They are like normal ciphers except that they return an authentication tag together with the ciphertext.

The authenticated cipher encryption is represented as AE(K, P) = (C, T). The term AE stands for authenticated encryption, which as you can see from this equation is based on a key (K) and a plaintext (P) and returns a ciphertext (C) and a generated authentication tag pair (T). In other words, a single authenticated cipher algorithm does the same job as a cipher and MAC combination, making it simpler, faster, and often more secure.

Authenticated cipher decryption is represented by AD(K, C, T) = P. Here, AD stands for authenticated decryption, which returns a plainte (P) given a ciphertext (C), tag (T), and key (K). If either or both C and T are invalid, AD will return an error to prevent the recipient from processing a plaintext that may have been forged. By the same token, if AD returns a plaintext, you can be sure that it has been encrypted by someone or something that knows the secret key.

The basic security requirements of an authenticated cipher are simple: its authentication should be as strong as a MAC’s, meaning that it should be impossible to forge a ciphertext and tag pair (C, T) that the decryption function AD will accept and decrypt.

As far as confidentiality is concerned, an authenticated cipher is fundamentally stronger than a basic cipher because systems holding the secret key will only decrypt a ciphertext if the authentication tag is valid. If the tag is invalid, the plaintext will be discarded. This characteristic prevents attackers from performing chosen-ciphertext queries, an attack where they create ciphertexts and ask for the corresponding plaintext.

Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data

Cryptographers define associated data as any data processed by an authenticated cipher such that the data is authenticated (thanks to the authentication tag) but not encrypted. Indeed, by default, all plaintext data fed to an authenticated cipher is encrypted and authenticated.

But what if you simply want to authenticate all of a message, including its unencrypted parts, but not encrypt the entire message? That is, you want to authenticate and transmit data in addition to an encrypted message. For example, if a cipher processes a network packet composed of a header followed by a payload, you might choose to encrypt the payload to hide the actual data transmitted, but not encrypt the header since it contains information required to deliver the packet to its final recipient. At the same time, you might still like to authenticate the header’s data to make sure that it is received from the expected sender.

In order to accomplish these goals, cryptographers have created the notion of authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD). An AEAD algorithm allows you to attach cleartext data to a ciphertext in such a way that if the cleartext data is corrupted, the authentication tag will not validate and the ciphertext will not be decrypted.

We can write an AEAD operation as AEAD(K, P, A) = (C, A, T). Given a key (K), plaintext (P), and associated data (A), AEAD returns the ciphertext, the unencrypted associated data A, and an authentication tag. AEAD leaves the unencrypted associated data unchanged, and the ciphertext is the encryption of plaintext. The authentication tag depends on both P and A, and will only be verified as valid if neither C nor A has been modified.

Because the authenticated tag depends on A, decryption with associated data is computed by ADAD(K, C, A, T) = (P, A). Decryption requires the key, ciphertext, associated data, and tag in order to compute the plaintext and associated data, and it will fail if either C or A has been corrupted.

One thing to note when using AEAD is that you can leave A or P empty. If the associated data A is empty, AEAD becomes a normal authenticated cipher; if P is empty, it’s just a MAC.

NOTE

As of this writing, AEAD is the current norm for authenticated encryption. Because nearly all authenticated ciphers in use today support associated data, when referring to authenticated ciphers throughout this book, I am referring to AEAD unless stated otherwise. When discussing AEAD operations of encryption and decryption, I’ll refer to them as AE and AD, respectively.

Avoiding Predictability with Nonces

Recall from Chapter 1 that in order to be secure, encryption schemes must be unpredictable and return different ciphertexts when called repeatedly to encrypt the same plaintext—otherwise, an attacker can determine whether the same plaintext was encrypted twice. In order to be unpredictable, block ciphers and stream ciphers feed the cipher an extra parameter: the initial value (IV) or nonce—a number that can be used only once. Authenticated ciphers use the same trick. Thus, authenticated encryption can be expressed as AE(K, P, A, N), where N is a nonce. It’s up to the encryption operation to pick a nonce that has never been used before with the same key.

As with block and stream ciphers, decryption with an authenticated cipher requires the nonce used for encryption in order to perform correctly. We can thus express decryption as AD(K, C, A, T, N) = (P, A), where N is the nonce used to create C and T.

What Makes a Good Authenticated Cipher?

Researchers have been struggling since the early 2000s to define what makes a good authenticated cipher, and as I write this, the answer is still elusive. Because of AEAD’s many inputs that play different roles, it’s harder to define a notion of security than it is for basic ciphers that only encrypt a message. Nevertheless, in this section, I’ll summarize the most important criteria to consider when evaluating the security, performance, and functionality of an authenticated cipher.

Security Criteria

The most important criteria used to measure the strength of an authenticated cipher are its ability to protect the confidentiality of data (that is, the secrecy of the plaintext) and the authenticity and integrity of the communication (as with the MAC’s ability to detect corrupted messages). An authenticated cipher must compete in both leagues: its confidentiality must be as strong as that of the strongest cipher, and its authenticity as strong as that of the best MAC. In other words, if you remove the authentication part in an AEAD, you should get a secure cipher, and if you remove the encryption part, you should get a strong MAC.

Another measure of the strength of an authenticated cipher’s security is based on something a bit more subtle—namely, its fragility when faced with repeated nonces. For example, if a nonce is reused, can an attacker decrypt ciphertexts or learn the difference between plaintexts?

Researchers call this notion of robustness misuse resistance, and have designed misuse-resistant authenticated ciphers to weigh the impact of a repeated nonce and attempt to determine whether confidentiality, authenticity, or both would be compromised in the face of such an attack, as well as what information about the encrypted data would likely be leaked.

Performance Criteria

As with every cryptographic algorithm, the throughput of an authenticated cipher can be measured in bits processed per second. This speed depends on the number of operations performed by the cipher’s algorithm and on the extra cost of the authentication functionality. As you might imagine, the extra security features of authenticated ciphers come with a performance hit. However, the measure of a cipher’s performance isn’t just about pure speed. It’s also about parallelizability, structure, and whether the cipher is streamable. Let’s examine these notions more closely.

A cipher’s parallelizability is a measure of its ability to process multiple data blocks simultaneously without waiting for the previous block’s processing to complete. Block cipher–based designs can be easily parallelizable when each block can be processed independently of the other blocks. For example, the CTR block cipher mode discussed in Chapter 4 is parallelizable, whereas the CBC encryption mode is not, because blocks are chained.

The internal structure of an authenticated cipher is another important performance criteria. There are two main types of structure: one-layer and two-layer. In a two-layer structure (for example, in the widely used AES-GCM), one algorithm processes the plaintext and then a second algorithm processes the result. Typically, the first layer is the encryption layer and the second is the authentication layer. But as you might expect, a two-layer structure complicates implementation and tends to slow down computations.

An authenticated cipher is streamable (also called an online cipher) when it can process a message block-by-block and discard any already-processed blocks. In contrast, nonstreamable ciphers must store the entire message, typically because they need to make two consecutive passes over the data: one from the start to the end, and the other from the end to the start of the data obtained from the first pass.

Due to potentially high memory requirements, some applications won’t work with nonstreamable ciphers. For example, a router could receive an encrypted block of data, decrypt it, and then return the plaintext block before moving on to decrypt the subsequent block of the message, though the recipient of the decrypted message would still have to verify the authentication tag sent at the end of the decrypted data stream.

Functional Criteria

Functional criteria are the features of a cipher or its implementation that don’t directly relate to either security or performance. For example, some authenticated ciphers only allow associated data to precede the data to be encrypted (because they need access to it in order to start encryption). Others require associated data to follow the data to be encrypted or support the inclusion of associated data anywhere—even between chunks of plaintext. This last case is the best, because it enables users to protect their data in any possible situation, but it’s also the hardest to design securely: as always, more features often bring more complexity—and more potential vulnerabilities.

Another piece of functional criteria to consider relates to whether you can use the same core algorithm for both encryption and decryption. For example, many authenticated ciphers are based on the AES block cipher, which specifies the use of two similar algorithms for encrypting and decrypting a block. As discussed in Chapter 4, the CBC block cipher mode requires both algorithms, but the CTR mode requires only the encryption algorithm. Likewise, authenticated ciphers may not need both algorithms. Although the extra cost of implementing both encryption and decryption algorithms won’t impact most software, it’s often noticeable on low-cost dedicated hardware, where implementation cost is measured in terms of logic gates, or the silicon area occupied by the cryptography.

AES-GCM: The Authenticated Cipher Standard

AES-GCM is the most widely used authenticated cipher. AES-GCM is, of course, based on the AES algorithm, and the Galois counter mode (GCM) of operation is essentially a tweak of the CTR mode that incorporates a small and efficient component to compute an authentication tag. As I write this, AES-GCM is the only authenticated cipher that is a NIST standard (SP 800-38D). AES-GCM is also part of NSA’s Suite B and of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) for the secure network protocols IPSec, SSH, and TLS 1.2.

NOTE

Although GCM works with any block cipher, you’ll probably only see it used with AES. Some people don’t want to use AES because it’s American, but they won’t use GCM either, for the same reason. Therefore, GCM is rarely paired with other ciphers.

GCM Internals: CTR and GHASH

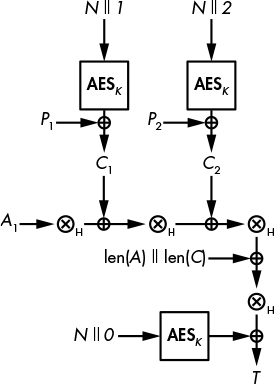

Figure 8-2: The AES-GCM mode, applied to one associated data block, A1, and two plaintext blocks, P1 and P2. The circled multiplication sign represents polynomial multiplication by H, the authentication key derived from K.

Figure 8-2 shows how AES-GCM works: AES instances parameterized by a secret key (K) transform a block composed of the nonce (N) concatenated with a counter (starting here at 1, then incremented to 2, 3, and so on) and then XOR the result with a plaintext block to obtain a ciphertext block. So far, that’s nothing new compared to the CTR mode.

Next, the ciphertext blocks are mixed using a combination of XORs and multiplications (as you’ll see next). You can see AES-GCM as doing 1) an encryption in CTR mode and 2) a MAC over the ciphertext blocks. Therefore, AES-GCM is essentially an encrypt-then-MAC construction, where AES-CTR encrypts using a 128-bit key (K) and a 96-bit nonce (N), with the minor difference that the counter starts from 1, not 0, as in normal CTR mode (which doesn’t matter, as far as security is concerned).

To authenticate the ciphertext, GCM uses a Wegman–Carter MAC (see Chapter 7) to authenticate the ciphertext, which XORs the value AES(K, N || 0) with the output of a universal hash function called GHASH. In Figure 8-2, GHASH corresponds to the series of operations “⊗H” followed by the XOR with len(A) || len(C), or the bit length of A (the associated data) followed by the bit length of C (the ciphertext).

We can thus express the authentication tag’s value as T = GHASH(H, C) ⊕ AES(K, N || 0), where C is the ciphertext and H is the hash key, or authentication key. This key is determined as H = AES(K, 0), which is the encryption of the block equal to a sequence of null bytes (this step does not appear in Figure 8-2, for clarity).

NOTE

In GCM, GHASH doesn’t use K directly in order to ensure that if GHASH’s key is compromised, the master key K remains secret. Given K, you can get H by computing AES(K, 0), but you can’t recover K from that value since K acts here as AES’s key.

As Figure 8-2 shows, GHASH uses polynomial notation to multiply each ciphertext block with the authentication key H. This use of polynomial multiplication makes GHASH fast in hardware as well as in software, thanks to a special polynomial multiplication instruction available in many common microprocessors (CLMUL, for carry-less multiplication).

Alas, GHASH is far from ideal. For one thing, its speed is suboptimal. Even when the CLMUL instruction is used, the AES-CTR layer that encrypts the plaintext remains faster than the GHASH MAC. Second, GHASH is painful to implement correctly. In fact, even the experienced developers of the OpenSSL project, by far the most-used cryptographic piece of software in the world, got AES-GCM’s GHASH wrong. One commit had a bug in a function called gcm_ghash_clmul that allowed attackers to forge valid MACs for the AES-GCM. (Fortunately, the error was spotted by Intel engineers before the bug entered the next OpenSSL release.)

GCM Security

AES-GCM’s biggest weakness is its fragility in the face of nonce repetition. If the same nonce N is used twice in an AES-GCM implementation, an attacker can get the authentication key H and use it to forge tags for any ciphertext, associated data, or combination thereof.

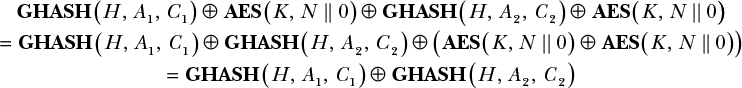

A look at the basic algebra behind AES-GCM’s computations (as shown in Figure 8-2) will help make this fragility clear. Specifically, a tag (T) is computed as T = GHASH(H, A, C) ⊕ AES(K, N || 0), where GHASH is a universal hash function with linearly related inputs and outputs.

Now what happens if you get two tags, T1 and T2, computed with the same nonce N ? Right, the AES part will vanish. If we have two tags, T1 = GHASH(H, A1, C1) ⊕ AES(K, N || 0) and T2 = GHASH(H, A1, C1) ⊕ AES(K, N || 0), then XORing them together gives the following:

If the same nonce is used twice, an attacker can thus recover the value GHASH(H, A1, C1) ⊕ GHASH(H, A2, C2) for some known A1, C1, A2, and C2. The linearity of GHASH then allows an attacker to easily determine H. (It would have been worse if GHASH had used the same key K as the encryption part, but because H = AES(K, 0), there’s no way to find K from H.)

As recently as 2016, researchers scanned the internet for instances of AES-GCM exposed through HTTPS servers, in search of systems with repeating nonces (see https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/475/). They found 184 servers with repeating nonces, including 23 that always used the all-zero string as a nonce.

GCM Efficiency

One advantage of GCM mode is that both GCM encryption and decryption are parallelizable, allowing you to encrypt or decrypt different plaintext blocks independently. However, the AES-GCM MAC computation isn’t parallelizable, because it must be computed from the beginning to the end of the ciphertext once GHASH has processed any associated data. This lack of parallelizability means that any system that receives the plaintext first and then the associated data will have to wait until all associated data is read and hashed before hashing the first ciphertext block.

Nevertheless, GCM is streamable: since the computations in its two layers can be pipelined, there’s no need to store all ciphertext blocks before computing GHASH because GHASH will process each block as it’s encrypted. In other words, P1 is encrypted to C1, then GHASH processes C1 while P2 is encrypted to C2, then P1 and C1 are no longer needed, and so on.

OCB: An Authenticated Cipher Faster than GCM

The acronym OCB stands for offset codebook (though its designer, Phil Rogaway, prefers to simply call it OCB). First developed in 2001, OCB predates GCM, and like GCM it produces an authenticated cipher from a block cipher, though it does so faster and more simply. Then why hasn’t OCB seen wider adoption? Unfortunately, until 2013, all uses of OCB required a license from the inventor. Fortunately, as I write this, Rogaway grants free licenses for nonmilitary software implementations (see http://web.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/ocb/license.htm). Therefore, although OCB is not yet a formal standard, perhaps we will begin to see wider adoption.

Unlike GCM, OCB blends encryption and authentication into one processing layer that uses only one key. There’s no separate authentication component, so OCB gets you authentication mostly for free and performs almost as many block cipher calls as a non-authenticated cipher. Actually, OCB is almost as simple as the ECB mode (see Chapter 4), except that it’s secure.

OCB Internals

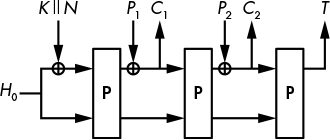

Figure 8-3 shows how OCB works: OCB encrypts each plaintext block P to a ciphertext block C = E(K, P ⊕ O) ⊕ O, where E is a block cipher encryption function. Here, O (called the offset) is a value that depends on the key and the nonce incremented for each new block processed.

To produce the authentication tag, OCB first XORs the plaintext blocks together to compute S = P1 ⊕ P2 ⊕ P3 ⊕ . . . (that is, the XOR of all plaintext blocks). The authentication tag is then T = E(K, S ⊕ O*), where O* is an offset value computed from the offset of the last plaintext block processed.

Figure 8-3: The OCB encryption process when run on two plaintext blocks, with no associated data

Like AES-GCM, OCB also supports associated data as a series of blocks, A1, A2, and so on. When an OCB encrypted message contains associated data, the authentication tag is calculated according to the formula

T = E(K, S ⊕ O*) ⊕ E(K, A1 ⊕ O1) ⊕ E(K, A2 ⊕ O2) ⊕ ...

where OCB specifies offset values that are different from those used to encrypt P.

Unlike GCM and encrypt-then-MAC, which create an authentication tag by combining ciphertext, OCB calculates the authentication tag by combining plaintext data. There’s nothing wrong with this approach, and OCB is backed by solid security proofs.

NOTE

For more on how to implement OCB correctly, see either RFC 7253 or the 2011 paper “The Software Performance of Authenticated-Encryption Modes” by Krovetz and Rogaway, which covers the latest and best version of OCB, OCB3. For further details on OCB, see the OCB FAQ at http://web.cs.ucdavis.edu/~rogaway/ocb/ocb-faq.htm.

OCB Security

OCB is a bit less fragile than GCM against repeated nonces. For example, if a nonce is used twice, an attacker that sees the two ciphertexts will notice that, say, the third plaintext block of the first message is identical to the third plaintext block of the second message. With GCM, attackers can find not only duplicates but also XOR differences between blocks at the same position. The impact of repeated nonces is therefore worse with GCM than it is with OCB.

As with GCM, repeated nonces can break the authenticity of OCB, though less effectively. For example, an attacker could combine blocks from two messages authenticated with OCB to create another encrypted message with the same checksum and tag as one of the original two messages, but the attacker would not be able to recover a secret key as with GCM.

OCB Efficiency

OCB and GCM are about equally fast. Like GCM, OCB is parallelizable and streamable. In terms of raw efficiency, GCM and OCB will make about as many calls to the underlying block cipher (usually AES), but OCB is slightly more efficient than GCM because it simply XORs the plaintext rather than performing something like the relatively expensive GHASH computation. (In earlier generations of Intel microprocessors, AES-GCM used to be more than three times slower than AES-OCB because AES and GHASH instructions had to compete for CPU resources and couldn’t be run in parallel.)

One important difference between OCB and GCM implementations is that OCB needs both the block cipher’s encryption and decryption functions in order to encrypt and decrypt, which increases the cost of hardware implementations when only limited silicon is available for crypto components. In contrast, GCM uses only the encryption function for both encryption and decryption.

SIV: The Safest Authenticated Cipher?

Synthetic IV, also known as SIV, is an authenticated cipher mode typically used with AES. Unlike GCM and OCB, SIV is secure even if you use the same nonce twice: if an attacker gets two ciphertexts encrypted using the same nonce, they’ll only be able to learn whether the same plaintext was encrypted twice. Unlike with messages encrypted with GCM or OCB, the attacker would be unable to tell whether the first block of the two messages is the same because the nonce used to encrypt is first computed as a combination of the given nonce and the plaintext.

The SIV construction specification is more general than that of GCM. Instead of specifying detailed internals as with GCM’s GHASH, SIV simply tells you how to combine a cipher (E) and a pseudorandom function (PRF) to get an authenticated cipher. Specifically, you compute the tag T = PRF(K1, N || P) and then compute the ciphertext C = E(K2, T, P), where T acts as the nonce of E. Thus, SIV needs two keys (K1 and K2) and a nonce (N).

The major problem with SIV is that it’s not streamable: after computing T, it must keep the entire plaintext P in memory. In other words, in order to encrypt a 100GB plaintext with SIV, you must first store the 100GB of plaintext so that SIV encryption can read it.

The document RFC 5297, based on the 2006 paper “Deterministic Authenticated-Encryption” by Rogaway and Shrimpton, specifies SIV as using CMAC-AES (a MAC construction using AES) as a PRF and AES-CTR as a cipher. In 2015, a more efficient version of SIV was proposed, called GCM-SIV, that combines GCM’s fast GHASH function and SIV’s mode and is nearly as fast as GCM. Like the original SIV, however, GCM-SIV isn’t streamable. (For more information, see https://eprint.iacr.org/2015/102/.)

Permutation-Based AEAD

Now for a totally different approach to building an authenticated cipher: instead of building a mode of operation around a block cipher like AES, we’ll look at a cipher that builds a mode around a permutation. A permutation simply transforms an input to an output of the same size, reversibly, without using a key, that’s the simplest component imaginable. Better still, the resulting AEAD is fast, provably secure, and more resistant to nonce reuse than GCM and OCB.

Figure 8-4 shows how a permutation-based AEAD works: from some fixed initial state H0, you XOR the key K followed by the nonce N to the internal state, to obtain a new value of the internal state that is the same size as the original. You then transform the new state with P and get another new value of the state. Now you XOR the first plaintext block P1 to the current state and take the resulting value as the first ciphertext block C1, where P1 and C1 are equal in size but smaller than the state.

To encrypt a second block, you transform the state with P, XOR the next plaintext block P2 to the current state, and take the resulting value as C2. You then iterate over all plaintext blocks and, following the last call to P, take bits from the internal state as the authentication tag T, as shown at the right of Figure 8-4.

Figure 8-4: Permutation-based authenticated cipher

NOTE

The mode shown in Figure 8-4 can be adapted to support associated data, but the process is a bit more complicated, so we’ll skip its description.

Designing permutation-based authenticated ciphers has certain requirements in order to ensure security. For one thing, note that you only XOR input values to a part of the state: the larger this part, the more control a successful attacker has on the internal state, and thus the lower the cipher’s security. Indeed, all security relies on the secrecy of the internal state.

Also, blocks must be padded properly with extra bits, in a way that ensures that any two different messages will yield different results. As a counterexample, if the last plaintext block is shorter than a complete block, it should not just be padded with zeroes; otherwise, a plaintext block of, say, two bytes (0000) would result in a complete plaintext block (0000 . . . 0000), as would a block of three bytes (000000). As a result, you’d get the same tag for both messages, although they differ in size.

What if a nonce is reused in such a permutation-based cipher? The good news is that the impact isn’t as bad as with GCM or OCB—the strength of the authentication tag won’t be compromised. If a nonce is repeated, a successful attacker would only be able to learn whether the two encrypted messages begin with the same value, as well as the length of this common value, or prefix. For example, although encrypting the two six-block messages ABCXYZ and ABCDYZ (each letter symbolizing a block here) with the same nonce might yield the two ciphertexts JKLTUV and JKLMNO, which have identical prefixes, attackers would not be able to learn that the two plaintexts shared the same final two blocks (YZ).

In terms of performance, permutation-based ciphers offer the benefits of a single layer of operations, streamable processing, and the use of a single core algorithm for encryption and decryption. However, they are not parallelizable like GCM or OCB because new calls to P need to wait for the previous call to complete.

NOTE

If you’re tempted to pick your favorite permutation and make up your own authenticated cipher, don’t. You’re likely to get the details wrong and end up with an insecure cipher. Read the specifications written by experienced cryptographers for algorithms such as Keyak (an algorithm derived from Keccak) and NORX (designed by Philipp Jovanovic, Samuel Neves, and myself), and you’ll see that permutation-based ciphers are way more complex than they may first appear.

How Things Can Go Wrong

Authenticated ciphers have a larger attack surface than hash functions or block ciphers because they aim to achieve both confidentiality and authenticity. They take several different input values, and must remain secure regardless of the input—whether that contains only associated data and no encrypted data, extremely large plaintexts, or different key sizes. They must also be secure for all nonce values against attackers who collect numerous message/tag pairs and, to some extent, against accidental repetition of nonces.

That’s a lot to ask, and as you’ll see next, even AES-GCM has several imperfections.

AES-GCM and Weak Hash Keys

One of AES-GCM’s weaknesses is found in its authentication algorithm GHASH: certain values of the hash key H greatly simplify attacks against GCM’s authentication mechanism. Specifically, if the value H belongs to some specific, mathematically defined subgroups of all 128-bit strings, attackers might be able to guess a valid authentication tag for some message simply by shuffling the blocks of a previous message.

In order to understand this weakness, let’s look at how GHASH works.

GHASH Internals

As you saw in Figure 8-2, GHASH starts with a 128-bit value, H, initially set to AES(K, 0), and then repeatedly computes

Xi = (Xi − 1 ⊕ Ci) ⊗ H

starting from X0 = 0 and processing ciphertext blocks C1, C2, and so on. The final Xi is returned by GHASH to compute the final tag.

Now say for the sake of simplicity that all Ci values are equal to 1, so that for any i we have this:

Ci ⊗ = 1 ⊗ H = H

Next, from the GHASH equation

Xi = (Xi − 1 ⊕ Ci) ⊗ H

we derive

X1 = (X0 ⊕ C1) ⊕ H = (0 ⊕ 1) ⊗ H = H

substituting X0 with 0 and C1 with 1, to yield the following:

(0 ⊕ 1) = 1

Thanks to the distributive property of ⊗ over ⊕, we substitute X with H and C2 with 1 and then compute the next value X2 as

X2= (X1 ⊕ X2) ⊗ H = (H ⊕ 1) ⊗ H = H2 ⊕ H

where H2 is H squared, or H ⊗ H.

Now we derive X3 by substituting X2 for its derivation, and obtain the following:

X3 = (X2 ⊕ C3) ⊗ H = (H2 ⊕ H ⊕ 1) ⊗ H = H3 ⊕ H2 ⊕ H

Next, we derive X4 to be X4 = H 4 ⊕ H 3 ⊕ H 2 ⊕ H, and so on, and eventually the last Xi is this:

Xn = Hn ⊕ Hn − 1 ⊕ Hn − 2 ⊕ ... ⊕ H2 ⊕ H

Remember that we set all blocks Ci equal to 1. If instead those values were arbitrary values, we would end up with the following:

Xn = C1 ⊕ Hn ⊕ C2 ⊕ Hn − 1 ⊕ C3 Hn − 2 ⊕ ... ⊕ Cn − 1 H2 ⊕ Cn ⊕ H

GHASH then would XOR the message’s length to this last Xn, multiply the result by H, and then XOR this value with AES(K, N || 0) to create the final authentication tag, T.

Where Things Break

What can go wrong from here? Let’s look first at the two simplest cases:

- If H = 0, then Xn = 0 regardless of the Ci values, and thus regardless of the message. That is, all messages will have the same authentication tag if H is 0.

- If H = 1, then the tag is just an XOR of the ciphertext blocks, and reordering the ciphertext blocks will give the same authentication tag.

Of course, 0 and 1 are only two values of 2128 possible values of H, so there is only a 2/2128 = 1/2127 chance of these occurring. But there are other weak values as well—namely, all values of H that belong to a short cycle when raised to ith powers. For example, the value H = 10d04d25f93556e69f58ce2f8d035a4 belongs to a cycle of length five, as it satisfies H 5 = H, and therefore He = H for any e that is a multiple of five (the very definition of cycle with respect to fifth powers). Consequently, in the preceding expression of the final GHASH value Xn, swapping the blocks Cn (multiplied to H) and the block Cn – 4 (multiplied to H 5) will leave the authentication tag unchanged, which amounts to a forgery. An attacker may exploit this property to construct a new message and its valid tag without knowing the key, which should be impossible for a secure authenticated cipher.

The preceding example is based on a cycle of length five, but there are many cycles of greater length and therefore many values of H that are weaker than they should be. The upshot is that, in the unlikely case that H belongs to a short cycle of values and attackers can forge as many authentication tags as they want, unless they know H or K, they cannot determine H’s cycle length. So although this vulnerability can’t be exploited, it could have been avoided by more carefully choosing the polynomial used for modulo reductions.

NOTE

For further details on this attack, read “Cycling Attacks on GCM, GHASH and Other Polynomial MACs and Hashes” by Markku-Juhani O. Saarinen, available at https://eprint.iacr.org/2011/202/.

AES-GCM and Small Tags

In practice, AES-GCM usually returns 128-bit tags, but it can produce tags of any length. Unfortunately, when shorter tags are used, the probability of forgery increases significantly.

When a 128-bit tag is used, an attacker who attempts a forgery should succeed with a probability of 1/2128 because there are 2128 possible 128-bit tags. (Generally, with an n-bit tag, the probability of success should be 1/2n, where 2N is the number of possible values of an n-bit tag.) But when shorter tags are used, the probability of forgery is much higher than 1/2n due to weaknesses in the structure of GCM that are beyond the scope of this discussion. For example, a 32-bit tag will allow an attacker who knows the authentication tag of some 2MB message to succeed with a chance of 1/216 instead of 1/232.

Generally, with n-bit tags, the probability of forgery isn’t 1/2n but rather 2m/2n, where 2m is the number of blocks of the longest message for which a successful attacker observed the tag. For example, if you use 48-bit tags and process messages of 4GB (or 228 blocks of 16 bytes each), the probability of a forgery will be 228/248 = 1/220, or about one chance in a million. That’s a relatively high chance as far as cryptography is concerned. (For more information on this attack, see the 2005 paper “Authentication Weaknesses in GCM” by Niels Ferguson.)

Further Reading

To learn more about authenticated ciphers, visit the home page of CAESAR, the Competition for Authenticated Encryption: Security, Applicability, and Robustness (http://competitions.cr.yp.to/caesar.html). Begun in 2012, CAESAR is a crypto competition in the style of the AES and SHA-3 competitions, though it isn’t organized by NIST.

The CAESAR competition has attracted an impressive number of innovative designs: from OCB-like modes to permutation-based modes, as well as new core algorithms. Examples include the previously mentioned NORX and Keyak permutation-based authenticated ciphers; AEZ (as in AEasy), which is built on a nonstreamable two-layer mode that makes it misuse resistant; AEGIS, a beautifully simple authenticated cipher that leverages AES’s round function.

In this chapter, I’ve focused on GCM, but a handful of other modes are used in real applications as well. Specifically, the counter with CBC-MAC (CCM) and EAX modes competed with GCM for standardization in the early 2000s, and although GCM was selected, the two competitors are used in a few applications. For example, CCM is used in the WPA2 Wi-Fi encryption protocol. You may want to read these ciphers’ specifications and review their relative security and performance merits.

This concludes our discussion of symmetric-key cryptography! You’ve seen block ciphers, stream ciphers, (keyed) hash functions, and now authenticated ciphers—or all the main cryptography components that work with a symmetric key, or no key at all. Before we move to asymmetric cryptography, Chapter 9 will focus more on computer science and math, to provide background for asymmetric schemes such as RSA (Chapter 10) and Diffie–Hellman (Chapter 11).