1

ENCRYPTION

Encryption is the principal application of cryptography; it makes data incomprehensible in order to ensure its confidentiality. Encryption uses an algorithm called a cipher and a secret value called the key; if you don’t know the secret key, you can’t decrypt, nor can you learn any bit of information on the encrypted message—and neither can any attacker.

This chapter will focus on symmetric encryption, which is the simplest kind of encryption. In symmetric encryption, the key used to decrypt is the same as the key used to encrypt (unlike asymmetric encryption, or public-key encryption, in which the key used to decrypt is different from the key used to encrypt). You’ll start by learning about the weakest forms of symmetric encryption, classical ciphers that are secure against only the most illiterate attacker, and then move on to the strongest forms that are secure forever.

The Basics

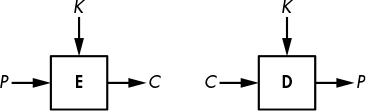

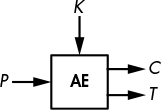

When we’re encrypting a message, plaintext refers to the unencrypted message and ciphertext to the encrypted message. A cipher is therefore composed of two functions: encryption turns a plaintext into a ciphertext, and decryption turns a ciphertext back into a plaintext. But we’ll often say “cipher” when we actually mean “encryption.” For example, Figure 1-1 shows a cipher, E, represented as a box taking as input a plaintext, P, and a key, K, and producing a ciphertext, C, as output. I’ll write this relation as C = E(K, P). Similarly, when the cipher is in decryption mode, I’ll write D(K, C).

Figure 1-1: Basic encryption and decryption

NOTE

For some ciphers, the ciphertext is the same size as the plaintext; for some others, the ciphertext is slightly longer. However, ciphertexts can never be shorter than plaintexts.

Classical Ciphers

Classical ciphers are ciphers that predate computers and therefore work on letters rather than on bits. They are much simpler than a modern cipher like DES—for example, in ancient Rome or during WWI, you couldn’t use a computer chip’s power to scramble a message, so you had to do everything with only pen and paper. There are many classical ciphers, but the most famous are the Caesar cipher and Vigenère cipher.

The Caesar Cipher

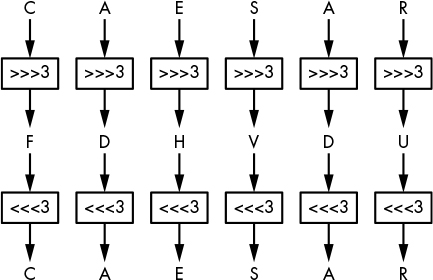

The Caesar cipher is so named because the Roman historian Suetonius reported that Julius Caesar used it. It encrypts a message by shifting each of the letters down three positions in the alphabet, wrapping back around to A if the shift reaches Z. For example, ZOO encrypts to CRR, FDHVDU decrypts to CAESAR, and so on, as shown in Figure 1-2. There’s nothing special about the value 3; it’s just easier to compute in one’s head than 11 or 23.

The Caesar cipher is super easy to break: to decrypt a given ciphertext, simply shift the letters three positions back to retrieve the plaintext. That said, the Caesar cipher may have been strong enough during the time of Crassus and Cicero. Because no secret key is involved (it’s always 3), users of Caesar’s cipher only had to assume that attackers were illiterate or too uneducated to figure it out—an assumption that’s much less realistic today. (In fact, in 2006, the Italian police arrested a mafia boss after decrypting messages written on small scraps of paper that were encrypted using a variant of the Caesar cipher: ABC was encrypted to 456 instead of DEF, for example.)

Could the Caesar cipher be made more secure? You can, for example, imagine a version that uses a secret shift value instead of always using 3, but that wouldn’t help much because an attacker could easily try all 25 possible shift values until the decrypted message makes sense.

The Vigenère Cipher

It took about 1500 years to see a meaningful improvement of the Caesar cipher in the form of the Vigenère cipher, created in the 16th century by an Italian named Giovan Battista Bellaso. The name “Vigenère” comes from the Frenchman Blaise de Vigenère, who invented a different cipher in the 16th century, but due to historical misattribution, Vigenère’s name stuck. Nevertheless, the Vigenère cipher became popular and was later used during the American Civil War by Confederate forces and during WWI by the Swiss Army, among others.

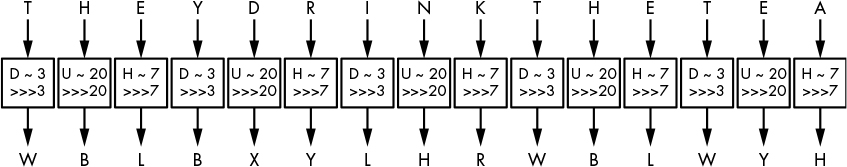

The Vigenère cipher is similar to the Caesar cipher, except that letters aren’t shifted by three places but rather by values defined by a key, a collection of letters that represent numbers based on their position in the alphabet. For example, if the key is DUH, letters in the plaintext are shifted using the values 3, 20, 7 because D is three letters after A, U is 20 letters after A, and H is seven letters after A. The 3, 20, 7 pattern repeats until you’ve encrypted the entire plaintext. For example, the word CRYPTO would encrypt to FLFSNV using DUH as the key: C is shifted three positions to F, R is shifted 20 positions to L, and so on. Figure 1-3 illustrates this principle when encrypting the sentence THEY DRINK THE TEA.

Figure 1-3: The Vigenère cipher

The Vigenère cipher is clearly more secure than the Caesar cipher, yet it’s still fairly easy to break. The first step to breaking it is to figure out the key’s length. For example, take the example in Figure 1-3, wherein THEY DRINK THE TEA encrypts to WBLBXYLHRWBLWYH with the key DUH. (Spaces are usually removed to hide word boundaries.) Notice that in the ciphertext WBLBXYLHRWBLWYH, the group of three letters WBL appears twice in the ciphertext at nine-letter intervals. This suggests that the same three-letter word was encrypted using the same shift values, producing WBL each time. A cryptanalyst can then deduce that the key’s length is either nine or a value divisible by nine (that is, three). Furthermore, they may guess that this repeated three-letter word is THE and therefore determine DUH as a possible encryption key.

The second step to breaking the Vigenère cipher is to determine the actual key using a method called frequency analysis, which exploits the uneven distribution of letters in languages. For example, in English, E is the most common letter, so if you find that X is the most common letter in a ciphertext, then the most likely plaintext value at this position is E.

Despite its relative weakness, the Vigenère cipher may have been good enough to securely encrypt messages when it was used. First, because the attack just outlined needs messages of at least a few sentences, it wouldn’t work if the cipher was used to encrypt only short messages. Second, most messages needed to be secret only for short periods of time, so it didn’t matter if ciphertexts were eventually decrypted by the enemy. (The 19th-century cryptographer Auguste Kerckhoffs estimated that most encrypted wartime messages required confidentiality for only three to four hours.)

How Ciphers Work

Based on simplistic ciphers like the Caesar and Vigenère ciphers, we can try to abstract out the workings of a cipher, first by identifying its two main components: a permutation and a mode of operation. A permutation is a function that transforms an item (in cryptography, a letter or a group of bits) such that each item has a unique inverse (for example, the Caesar cipher’s three-letter shift). A mode of operation is an algorithm that uses a permutation to process messages of arbitrary size. The mode of the Caesar cipher is trivial: it just repeats the same permutation for each letter, but as you’ve seen, the Vigenère cipher has a more complex mode, where letters at different positions undergo different permutations.

In the following sections, I discuss in more detail what these are and how they relate to a cipher’s security. I use each component to show why classical ciphers are doomed to be insecure, unlike modern ciphers that run on high-speed computers.

The Permutation

Most classical ciphers work by replacing each letter with another letter—in other words, by performing a substitution. In the Caesar and Vigenère ciphers, the substitution is a shift in the alphabet, though the alphabet or set of symbols can vary: instead of the English alphabet, it could be the Arabic alphabet; instead of letters, it could be words, numbers, or ideograms, for example. The representation or encoding of information is a separate matter that is mostly irrelevant to security. (We’re just considering Latin letters because that’s what classical ciphers use.)

A cipher’s substitution can’t be just any substitution. It should be a permutation, which is a rearrangement of the letters A to Z, such that each letter has a unique inverse. For example, a substitution that transforms the letters A, B, C, and D, respectively to C, A, D, and B is a permutation, because each letter maps onto another single letter. But a substitution that transforms A, B, C, D to D, A, A, C is not a permutation, because both B and C map onto A. With a permutation, each letter has exactly one inverse.

Still, not every permutation is secure. In order to be secure, a cipher’s permutation should satisfy three criteria:

- The permutation should be determined by the key, so as to keep the permutation secret as long as the key is secret. In the Vigenère cipher, if you don’t know the key, you don’t know which of the 26 permutations was used; hence, you can’t easily decrypt.

- Different keys should result in different permutations. Otherwise, it becomes easier to decrypt without the key: if different keys result in identical permutations, that means there are fewer distinct keys than distinct permutations, and therefore fewer possibilities to try when decrypting without the key. In the Vigenère cipher, each letter from the key determines a substitution; there are 26 distinct letters, and as many distinct permutations.

- The permutation should look random, loosely speaking. There should be no pattern in the ciphertext after performing a permutation, because patterns make a permutation predictable for an attacker, and therefore less secure. For example, the Vigenère cipher’s substitution is pretty predictable: if you determine that A encrypts to F, you could conclude that the shift value is 5 and you would also know that B encrypts to G, that C encrypts to H, and so on. However, with a randomly chosen permutation, knowing that A encrypts to F would only tell you that B does not encrypt to F.

We’ll call a permutation that satisfies these criteria a secure permutation. But as you’ll see next, a secure permutation is necessary but not sufficient on its own for building a secure cipher. A cipher will also need a mode of operation to support messages of any length.

The Mode of Operation

Say we have a secure permutation that transforms A to X, B to M, and N to L, for example. The word BANANA therefore encrypts to MXLXLX, where each occurrence of A is replaced by an X. Using the same permutation for all the letters in the plaintext thus reveals any duplicate letters in the plaintext. By analyzing these duplicates, you might not learn the entire message, but you’ll learn something about the message. In the BANANA example, you don’t need the key to guess that the plaintext has the same letter at the three X positions and another same letter at the two L positions. So if you know, for example, that the message is a fruit’s name, you could determine that it’s BANANA rather than CHERRY, LYCHEE, or another six-letter fruit.

The mode of operation (or just mode) of a cipher mitigates the exposure of duplicate letters in the plaintext by using different permutations for duplicate letters. The mode of the Vigenère cipher partially addresses this: if the key is N letters long, then N different permutations will be used for every N consecutive letters. However, this can still result in patterns in the ciphertext because every Nth letter of the message uses the same permutation. That’s why frequency analysis works to break the Vigenère cipher, as you saw earlier.

Frequency analysis can be defeated if the Vigenère cipher only encrypts plaintexts that are of the same length as the key. But even then, there’s another problem: reusing the same key several times exposes similarities between plaintexts. For example, with the key KYN, the words TIE and PIE encrypt to DGR and ZGR, respectively. Both end with the same two letters (GR), revealing that both plaintexts share their last two letters as well. Finding these patterns shouldn’t be possible with a secure cipher.

To build a secure cipher, you must combine a secure permutation with a secure mode. Ideally, this combination prevents attackers from learning anything about a message other than its length.

Why Classical Ciphers Are Insecure

Classical ciphers are doomed to be insecure because they’re limited to operations you can do in your head or on a piece of paper. They lack the computational power of a computer and are easily broken by simple computer programs. Let’s see the fundamental reason why that simplicity makes them insecure in today’s world.

Remember that a cipher’s permutation should look random in order to be secure. Of course, the best way to look random is to be random—that is, to select every permutation randomly from the set of all permutations. And there are many permutations to choose from. In the case of the 26-letter English alphabet, there are approximately 288 permutations:

26! = 403291461126605635584000000 ≈ 288

Here, the exclamation point (!) is the factorial symbol, defined as follows:

n! = n × (n − 1) × (n – 2) × . . . × 3 × 2

(To see why we end up with this number, count the permutations as lists of reordered letters: there are 26 choices for the first possible letter, then 25 possibilities for the second, 24 for the third, and so on.) This number is huge: it’s of the same order of magnitude as the number of atoms in the human body. But classical ciphers can only use a small fraction of those permutations—namely, those that need only simple operations (such as shifts) and that have a short description (like a short algorithm or a small look-up table). The problem is that a secure permutation can’t accommodate both of these limitations.

You can get secure permutations using simple operations by picking a random permutation, representing it as a table of 25 letters (enough to represent a permutation of 26 letters, with the 26th one missing), and applying it by looking up letters in this table. But then you wouldn’t have a short description. For example, it would take 250 letters to describe 10 different permutations, rather than just the 10 letters used in the Vigenère cipher.

You can also produce secure permutations with a short description. Instead of just shifting the alphabet, you could use more complex operations such as addition, multiplication, and so on. That’s how modern ciphers work: given a key of typically 128 or 256 bits, they perform hundreds of bit operations to encrypt a single letter. This process is fast on a computer that can do billions of bit operations per second, but it would take hours to do by hand, and would still be vulnerable to frequency analysis.

Perfect Encryption: The One-Time Pad

Essentially, a classical cipher can’t be secure unless it comes with a huge key, but encrypting with a huge key is impractical. However, the one-time pad is such a cipher, and it is the most secure cipher. In fact, it guarantees perfect secrecy: even if an attacker has unlimited computing power, it’s impossible to learn anything about the plaintext except for its length.

In the next sections, I’ll show you how a one-time pad works and then offer a sketch of its security proof.

Encrypting with the One-Time Pad

The one-time pad takes a plaintext, P, and a random key, K, that’s the same length as P and produces a ciphertext C, defined as

C = P ⊕ K

where C, P, and K are bit strings of the same length and where ⊕ is the bitwise exclusive OR operation (XOR), defined as 0 ⊕ 0 = 0, 0 ⊕ 1 = 1, 1 ⊕ 0 = 1, 1 ⊕ 1 = 0.

NOTE

I’m presenting the one-time pad in its usual form, as working on bits, but it can be adapted to other symbols. With letters, for example, you would end up with a variant of the Caesar cipher with a shift index picked at random for each letter.

The one-time pad’s decryption is identical to encryption; it’s just an XOR: P = C ⊕ K. Indeed, we can verify C ⊕ K = P ⊕ K ⊕ K = P because XORing K with itself gives the all-zero string 000 . . . 000. That’s it—even simpler than the Caesar cipher.

For example, if P = 01101101 and K = 10110100, then we can calculate the following:

C = P ⊕ K = 01101101 ⊕ 10110100 = 11011001

Decryption retrieves P by computing the following:

P = C ⊕ K = 11011001 ⊕ 10110100 = 01101101

The important thing is that a one-time pad can only be used one time: each key K should be used only once. If the same K is used to encrypt P1 and P2 to C1 and C2, then an eavesdropper can compute the following:

C1 ⊕ C2 = (P1 ⊕ K) ⊕ (P2 ⊕ K) = P1 ⊕ P2 ⊕ K ⊕ K = P1 ⊕ P2

An eavesdropper would thus learn the XOR difference of P1 and P2, information that should be kept secret. Moreover, if either plaintext message is known, then the other message can be recovered.

Of course, the one-time pad is utterly inconvenient to use because it requires a key as long as the plaintext and a new random key for each new message or group of data. To encrypt a one-terabyte hard drive, you’d need another one-terabyte drive to store the key! Nonetheless, the one-time pad has been used throughout history. For example, it was used by the British Special Operations Executive during WWII, by KGB spies, by the NSA, and is still used today in specific contexts. (I’ve heard of Swiss bankers who couldn’t agree on a cipher trusted by both parties and ended up using one-time pads, but I don’t recommend doing this.)

Why Is the One-Time Pad Secure?

Although the one-time pad is not practical, it’s important to understand what makes it secure. In the 1940s, American mathematician Claude Shannon proved that the one-time pad’s key must be at least as long as the message to achieve perfect secrecy. The proof’s idea is fairly simple. You assume that the attacker has unlimited power, and thus can try all the keys. The goal is to encrypt such that the attacker can’t rule out any possible plaintext given some ciphertext.

The intuition behind the one-time pad’s perfect secrecy goes as follows: if K is random, the resulting C looks as random as K to an attacker because the XOR of a random string with any fixed string yields a random string. To see this, consider the probability of getting 0 as the first bit of a random string (namely, a probability of 1/2). What’s the probability that a random bit XORed with the second bit is 0? Right, 1/2 again. The same argument can be iterated over bit strings of any length. The ciphertext C thus looks random to an attacker that doesn’t know K, so it’s literally impossible to learn anything about P given C, even for an attacker with unlimited time and power. In other words, knowing the ciphertext gives no information whatsoever about the plaintext except its length—pretty much the definition of a secure cipher.

For example, if a ciphertext is 128 bits long (meaning the plaintext is 128 bits as well), there are 2128 possible ciphertexts; therefore, there should be 2128 possible plaintexts from the attacker’s point of view. But if there are fewer than 2128 possible keys, the attacker can rule out some plaintexts. If the key is only 64 bits, for example, the attacker can determine the 264 possible plaintexts and rule out the overwhelming majority of 128-bit strings. The attacker wouldn’t learn what the plaintext is, but they would learn what the plaintext is not, which makes the encryption’s secrecy imperfect.

As you can see, you must have a key as long as the plaintext to achieve perfect security, but this quickly becomes impractical for real-world use. Next, I’ll discuss the approaches taken in modern-day encryption to achieve the best security that’s both possible and practical.

Encryption Security

You’ve seen that classical ciphers aren’t secure and that a perfectly secure cipher like the one-time pad is impractical. We’ll thus have to give a little in terms of security if we want secure and usable ciphers. But what does “secure” really mean, besides the obvious and informal “eavesdroppers can’t decrypt secure messages”?

Intuitively, a cipher is secure if, even given a large number of plaintext–ciphertext pairs, nothing can be learned about the cipher’s behavior when applied to other plaintexts or ciphertexts. This opens up new questions:

- How does an attacker come by these pairs? How large is a “large number”? This is all defined by attack models, assumptions about what the attacker can and cannot do.

- What could be “learned” and what “cipher’s behavior” are we talking about? This is defined by security goals, descriptions of what is considered a successful attack.

Attack models and security goals must go together; you can’t claim that a system is secure without explaining against whom or from what it’s safe. A security notion is thus the combination of some security goal with some attack model. We’ll say that a cipher achieves a certain security notion if any attacker working in a given model can’t achieve the security goal.

Attack Models

An attack model is a set of assumptions about how attackers might interact with a cipher and what they can and can’t do. The goals of an attack model are as follows:

- To set requirements for cryptographers who design ciphers, so that they know what attackers and what kinds of attacks to protect against.

- To give guidelines to users, about whether a cipher will be safe to use in their environment.

- To provide clues for cryptanalysts who attempt to break ciphers, so they know whether a given attack is valid. An attack is only valid if it’s doable in the model considered.

Attack models don’t need to match reality exactly; they’re an approximation. As the statistician George E. P. Box put it, “all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.” To be useful in cryptography, attack models should at least encompass what attackers can actually do to attack a cipher. It’s okay and a good thing if a model overestimates attackers’ capabilities, because it helps anticipate future attack techniques—only the paranoid cryptographers survive. A bad model underestimates attackers and provides false confidence in a cipher by making it seem secure in theory when it’s not secure in reality.

Kerckhoffs’s Principle

One assumption made in all models is the so-called Kerckhoffs’s principle, which states that the security of a cipher should rely only on the secrecy of the key and not on the secrecy of the cipher. This may sound obvious today, when ciphers and protocols are publicly specified and used by everyone. But historically, Dutch linguist Auguste Kerckhoffs was referring to military encryption machines specifically designed for a given army or division. Quoting from his 1883 essay “La Cryptographie Militaire,” where he listed six requirements of a military encryption system: “The system must not require secrecy and can be stolen by the enemy without causing trouble.”

Black-Box Models

Let’s now consider some useful attack models expressed in terms of what the attacker can observe and what queries they can make to the cipher. A query for our purposes is the operation that sends an input value to some function and gets the output in return, without exposing the details of that function.

An encryption query, for example, takes a plaintext and returns a corresponding ciphertext, without revealing the secret key.

We call these models black-box models, because the attacker only sees what goes in and out of the cipher. For example, some smart card chips securely protect a cipher’s internals as well as its keys, yet you’re allowed to connect to the chip and ask it to decrypt any ciphertext. The attacker would then receive the corresponding plaintext, which may help them determine the key. That’s a real example where decryption queries are possible.

There are several different black-box attack models. Here, I list them in order from weakest to strongest, describing attackers’ capabilities for each model:

- Ciphertext-only attackers (COA) observe ciphertexts but don’t know the associated plaintexts, and don’t know how the plaintexts were selected. Attackers in the COA model are passive and can’t perform encryption or decryption queries.

- Known-plaintext attackers (KPA) observe ciphertexts and do know the associated plaintexts. Attackers in the KPA model thus get a list of plaintext–ciphertext pairs, where plaintexts are assumed to be randomly selected. Again, KPA is a passive attacker model.

- Chosen-plaintext attackers (CPA) can perform encryption queries for plaintexts of their choice and observe the resulting ciphertexts. This model captures situations where attackers can choose all or part of the plaintexts that are encrypted and then get to see the ciphertexts. Unlike COA or KPA, which are passive models, CPA are active attackers, because they influence the encryption processes rather than passively eavesdropping.

- Chosen-ciphertext attackers (CCA) can both encrypt and decrypt; that is, they get to perform encryption queries and decryption queries. The CCA model may sound ludicrous at first—if you can decrypt, what else do you need?—but like the CPA model, it aims to represent situations where attackers can have some influence on the ciphertext and later get access to the plaintext. Moreover, decrypting something is not always enough to break a system. For example, some video-protection devices allow attackers to perform encryption queries and decryption queries using the device’s chip, but in that context attackers are interested in the key in order to redistribute it; in this case, being able to decrypt “for free” isn’t sufficient to break the system.

In the preceding models, ciphertexts that are observed as well as queried don’t come for free. Each ciphertext comes from the computation of the encryption function. This means that generating 2n plaintext–ciphertext pairs through encryption queries takes about as much computation as trying 2n keys, for example. The cost of queries should be taken into account when you’re computing the cost of an attack.

Gray-Box Models

In a gray-box model, the attacker has access to a cipher’s implementation. This makes gray-box models more realistic than black-box models for applications such as smart cards, embedded systems, and virtualized systems, to which attackers often have physical access and can thus tamper with the algorithms’ internals. By the same token, gray-box models are more difficult to define than black-box ones because they depend on physical, analog properties rather than just on an algorithm’s input and outputs, and crypto theory will often fail to abstract the complexity of the real world.

Side-channel attacks are a family of attacks within gray-box models. A side channel is a source of information that depends on the implementation of the cipher, be it in software or hardware. Side-channel attackers observe or measure analog characteristics of a cipher’s implementation but don’t alter its integrity; they are noninvasive. For pure software implementations, typical side channels are the execution time and the behavior of the system that surrounds the cipher, such as error messages, return values, branches, and so on. In the case of implementations on smart cards, for example, typical side-channel attackers measure power consumption, electromagnetic emanations, or acoustic noise.

Invasive attacks are a family of attacks on cipher implementations that are more powerful than side-channel attacks, and more expensive because they require sophisticated equipment. You can run basic side-channel attacks with a standard PC and an off-the-shelf oscilloscope, but invasive attacks require tools such as a high-resolution microscopes and a chemical lab. Invasive attacks thus consist of a whole set of techniques and procedures, from using nitric acid to remove a chip’s packaging to microscopic imagery acquisition, partial reverse engineering, and possible modification of the chip’s behavior with something like laser fault injection.

Security Goals

I’ve informally defined the goal of security as “nothing can be learned about the cipher’s behavior.” To turn this idea into a rigorous mathematical definition, cryptographers define two main security goals that correspond to different ideas of what it means to learn something about a cipher’s behavior:

Indistinguishability (IND) Ciphertexts should be indistinguishable from random strings. This is usually illustrated with this hypothetical game: if an attacker picks two plaintexts and then receives a ciphertext of one of the two (chosen at random), they shouldn’t be able to tell which plaintext was encrypted, even by performing encryption queries with the two plaintexts (and decryption queries, if the model is CCA rather than CPA).

Non-malleability (NM) Given a ciphertext C1 = E(K, P1), it should be impossible to create another ciphertext, C2, whose corresponding plaintext, P2, is related to P1 in a meaningful way (for example, to create a P2 that is equal to P1 ⊕ 1 or to P1 ⊕ X for some known value X). Surprisingly, the one-time pad is malleable: given a ciphertext C1 = P1 ⊕ K, you can define C2 = C1 ⊕ 1, which is a valid ciphertext of P2 = P1 ⊕ 1 under the same key K. Oops, so much for our perfect cipher.

Next, I’ll discuss these security goals in the context of different attack models.

Security Notions

Security goals are only useful when combined with an attack model. The convention is to write a security notion as GOAL-MODEL. For example, IND-CPA denotes indistinguishability against chosen-plaintext attackers, NM-CCA denotes nonmalleability against chosen-ciphertext attackers, and so on. Let’s start with the security goals for an attacker.

Semantic Security and Randomized Encryption: IND-CPA

The most important security notion is IND-CPA, also called semantic security. It captures the intuition that ciphertexts shouldn’t leak any information about plaintexts as long as the key is secret. To achieve IND-CPA security, encryption must return different ciphertexts if called twice on the same plaintext; otherwise, an attacker could identify duplicate plaintexts from their ciphertexts, contradicting the definition that ciphertexts shouldn’t reveal any information.

One way to achieve IND-CPA security is to use randomized encryption. As the name suggests, it randomizes the encryption process and returns different ciphertexts when the same plaintext is encrypted twice. Encryption can then be expressed as C = E(K, R, P), where R is fresh random bits. Decryption remains deterministic, however, because given E(K, R, P), you should always get P, regardless of the value of R.

What if encryption isn’t randomized? In the IND game introduced in “Security Goals” on page 12, the attacker picks two plaintexts, P1 and P2, and receives a ciphertext of one of the two, but doesn’t know which plaintext the ciphertext corresponds to. That is, they get Ci = E(K, Pi) and have to guess whether i is 1 or 2. In the CPA model, the attacker can perform encryption queries to determine both C1 = E(K, P1) and C2 = E(K, P2). If encryption isn’t randomized, it suffices to see if Ci is equal to C1 or to C2 in order to determine which plaintext was encrypted and thereby win the IND game. Therefore, randomization is key to the IND-CPA notion.

NOTE

With randomized encryption, ciphertexts must be slightly longer than plaintexts in order to allow for more than one possible ciphertext per plaintext. For example, if there are 264 possible ciphertexts per plaintext, ciphertexts must be at least 64 bits longer than plaintexts.

Achieving Semantically Secure Encryption

One of the simplest constructions of a semantically secure cipher uses a deterministic random bit generator (DRBG), an algorithm that returns random-looking bits given some secret value:

E(K, R, P) = (DRBG(K R) ⊕ P, R)

Here, R is a string randomly chosen for each new encryption and given to a DRBG along with the key (K || R denotes the string consisting of K followed by R). This approach is reminiscent of the one-time pad: instead of picking a random key of the same length as the message, we leverage a random bit generator to get a random-looking string.

The proof that this cipher is IND-CPA secure is simple, if we assume that the DRBG produces random bits. The proof works ad absurdum: if you can distinguish ciphertexts from random strings, which means that you can distinguish DRBG(K || R) ⊕ P from random, then this means that you can distinguish DRBG(K || R) from random. Remember that the CPA model lets you get ciphertexts for chosen values of P, so you can XOR P to DRBG(K, R) ⊕ P and get DRBG(K, R). But now we have a contradiction, because we started by assuming that DRBG(K, R) can’t be distinguished from random, producing random strings. So we conclude that ciphertexts can’t be distinguished from random strings, and therefore that the cipher is secure.

NOTE

As an exercise, try to determine what other security notions are satisfied by the above cipher E(K, R, P) = (DRBG(K || R) ⊕ P, R). Is it NM-CPA? IND-CCA? You’ll find the answers in the next section.

Comparing Security Notions

You’ve learned that attack models such as CPA and CCA are combined with security goals such as NM and IND to build the security notions NM-CPA, NM-CCA, IND-CPA, and IND-CCA. How are these notions related? Can we prove that satisfying notion X implies satisfying notion Y?

Some relations are obvious: IND-CCA implies IND-CPA, and NM-CCA implies NM-CPA, because anything a CPA attacker can do, a CCA attacker can do as well. That is, if you can’t break a cipher by performing chosen-ciphertext and chosen-plaintext queries, you can’t break it by performing chosen-plaintext queries only.

A less obvious relation is that IND-CPA does not imply NM-CPA. To understand this, observe that the previous IND-CPA construction (DRBG(K, R) ⊕ P, R) is not NM-CPA: given a ciphertext (X, R), you can create the ciphertext (X ⊕ 1, R), which is a valid ciphertext of P ⊕ 1, thus contradicting the notion of non-malleability.

But the opposite relation does hold: NM-CPA implies IND-CPA. The intuition is that IND-CPA encryption is like putting items in a bag: you don’t get to see them, but you can rearrange their positions in the bag by shaking it up and down. NM-CPA is more like a safe: once inside, you can’t interact with what you put in there. But this analogy doesn’t work for IND-CCA and NM-CCA, which are equivalent notions that each imply the presence of the other. I’ll spare you the proof, which is pretty technical.

Asymmetric Encryption

So far we’ve considered only symmetric encryption, where two parties share a key. In asymmetric encryption, there are two keys: one to encrypt and another to decrypt. The encryption key is called a public key and is generally considered publicly available to anyone who wants to send you encrypted messages. The decryption key, however, must remain secret and is called a private key.

The public key can be computed from the private key, but obviously the private key can’t be computed from the public key. In other words, it’s easy to compute in one direction, but not in the other—and that’s the point of public-key cryptography, whose functions are easy to compute in one direction but practically impossible to invert.

The attack models and security goals for asymmetric encryption are about the same as for symmetric encryption, except that because the encryption key is public, any attacker can make encryption queries by using the public key to encrypt. The default model for asymmetric encryption is therefore the chosen-plaintext attacker (CPA).

Symmetric and asymmetric encryption are the two main types of encryption, and they are usually combined to build secure communication systems. They’re also used to form the basis of more sophisticated schemes, as you’ll see next.

When Ciphers Do More Than Encryption

Basic encryption turns plaintexts into ciphertexts and ciphertexts into plaintexts, with no requirements other than security. However, some applications often need more than that, be it extra security features or extra functionalities. That’s why cryptographers created variants of symmetric and asymmetric encryption. Some are well-understood, efficient, and widely deployed, while others are experimental, hardly used, and offer poor performance.

Authenticated Encryption

Authenticated encryption (AE) is a type of symmetric encryption that returns an authentication tag in addition to a ciphertext. Figure 1-4 shows authenticated encryption sets AE(K, P) = (C, T), where the authentication tag T is a short string that’s impossible to guess without the key. Decryption takes K, C, and T and returns the plaintext P only if it verifies that T is a valid tag for that plaintext–ciphertext pair; otherwise, it aborts and returns some error.

Figure 1-4: Authenticated encryption

The tag ensures the integrity of the message and serves as evidence that the ciphertext received is identical to the one sent in the first place by a legitimate party that knows the key K. When K is shared with only one other party, the tag also guarantees that the message was sent by that party; that is, it implicitly authenticates the expected sender as the actual creator of the message.

NOTE

I use “creator” rather than “sender” here because an eavesdropper can record some (C, T) pairs sent by party A to party B and then send them again to B, pretending to be A. This is called a replay attack, and it can be prevented, for example, by including a counter number in the message. When a message is decrypted, its counter i is increased by one: i + 1. In this way, one could check the counter to see if a message has been sent twice, indicating that an attacker is attempting a replay attack by resending the message. This also enables the detection of lost messages.

Authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD) is an extension of authenticated encryption that takes some cleartext and unencrypted data and uses it to generate the authentication tag AEAD(K, P, A) = (C, T). A typical application of AEAD is used to protect protocols’ datagrams with a cleartext header and an encrypted payload. In such cases, at least some header data has to remain in the clear; for example, destination addresses need to be clear in order to route network packets.

For more on authenticated encryption, jump to Chapter 8.

Format-Preserving Encryption

A basic cipher takes bits and returns bits; it doesn’t care whether bits represents text, an image, or a PDF document. The ciphertext may in turn be encoded as raw bytes, hexadecimal characters, base64, and other formats. But what if you need the ciphertext to have the same format as the plaintext, as is sometimes required by database systems that can only record data in a prescribed format?

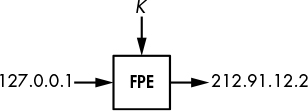

Format-preserving encryption (FPE) solves this problem. It can create ciphertexts that have the same format as the plaintext. For example, FPE can encrypt IP addresses to IP addresses (as shown in Figure 1-5), ZIP codes to ZIP codes, credit card numbers to credit card numbers with a valid checksum, and so on.

Figure 1-5: Format-preserving encryption for IP addresses

Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is the holy grail to cryptographers: it enables its users to replace a ciphertext, C = E(K, P), with another ciphertext, C′ = E(K, F(P)), for F(P) can be any function of P, and without ever decrypting the initial ciphertext C. For example, P can be a text document, and F can be the modification of part of the text. You can imagine a cloud application that stores your encrypted data, but where the cloud provider doesn’t know what the data is or the type of changes made when you change that data. Sounds amazing, doesn’t it?

But there’s a flip side: this type of encryption is slow—so slow that even the most basic operation would take an unacceptably long time. The first FHE scheme was created in 2009, and since then more efficient variants appeared, but it remains unclear whether FHE will ever be fast enough to be useful.

Searchable Encryption

Searchable encryption enables searching over an encrypted database without leaking the searched terms by encrypting the search query itself. Like fully homomorphic encryption, searchable encryption could enhance the privacy of many cloud-based applications by hiding your searches from your cloud provider. Some commercial solutions claim to offer searchable encryption, though they’re mostly based on standard cryptography with a few tricks to enable partial searchability. As of this writing, however, searchable encryption remains experimental within the research community.

Tweakable Encryption

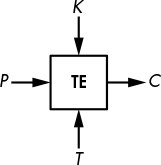

Tweakable encryption (TE) is similar to basic encryption, except for an additional parameter called the tweak, which aims to simulate different versions of a cipher (see Figure 1-6). The tweak might be a unique per-customer value to ensure that a customer’s cipher can’t be cloned by other parties using the same product, but the main application of TE is disk encryption. However, TE is not bound to a single application and is a lower-level type of encryption used to build other schemes, such as authentication encryption modes.

Figure 1-6: Tweakable encryption

In disk encryption, TE encrypts the content of storage devices such as hard drives or solid-state drives. (Randomized encryption can’t be used because it increases the size of the data, which is unacceptable for files on storage media.) To make encryption unpredictable, TE uses a tweak value that depends on the position of the data encrypted, which is usually a sector number or a block index.

How Things Can Go Wrong

Encryption algorithms or implementations thereof can fail to protect confidentiality in many ways. This can be due to a failure to match the security requirements (such as “be IND-CPA secure”) or to set requirements matching reality (if you target only IND-CPA security when attackers can actually perform chosen-ciphertext queries). Alas, many engineers don’t even think about cryptographic security requirements and just want to be “secure” without understanding what that actually means. That’s usually a recipe for disaster. Let’s look at two examples.

Weak Cipher

Our first example concerns ciphers that can be attacked using cryptanalysis techniques, as occurred with the 2G mobile communication standard. Encryption in 2G mobile phones used a cipher called A5/1 that turned out to be weaker than expected, enabling the interception of calls by anyone with the right skills and tools. Telecommunication operators had to find workarounds to prevent the attack.

NOTE

The 2G standard also defined A5/2, a cipher for areas other than the EU and US. A5/2 was purposefully weaker to prevent the use of strong encryption everywhere.

That said, attacking A5/1 isn’t trivial, and it took more than 10 years for researchers to come up with an effective cryptanalysis method. Furthermore, the attack is a time-memory trade-off (TMTO), a type of method that first runs computations for days or weeks in order to build large look-up tables, which are subsequently used for the actual attack. For A5/1, the precomputed tables are more than 1TB. Later standards for mobile encryption, such as 3G and LTE, specify stronger ciphers, but that doesn’t mean that their encryption won’t be compromised; rather, it simply means that the encryption won’t be compromised by breaking the symmetric cipher that’s part of the system.

Wrong Model

The next example concerns an invalid attack model that overlooked some side channels.

Many communication protocols that use encryption ensure that they use ciphers considered secure in the CPA or CCA model. However, some attacks don’t require encryption queries, as in the CPA model, nor do they require decryption queries, as in the CCA model. They simply need validity queries to tell whether a ciphertext is valid, and these queries are usually sent to the system responsible for decrypting ciphertexts. Padding oracle attacks are an example of such attacks, wherein an attacker learns whether a ciphertext conforms to the required format.

Specifically, in the case of padding oracle attacks, a ciphertext is valid only if its plaintext has the proper padding, a sequence of bytes appended to the plaintext to simplify encryption. Decryption fails if the padding is incorrect, and attackers can often detect decryption failures and attempt to exploit them. For example, the presence of the Java exception javax.crypto.BadPaddingException would indicate that an incorrect padding was observed.

In 2010, researchers found padding oracle attacks in several web application servers. The validity queries consisted of sending a ciphertext to some system and observing whether it threw an error. Thanks to these queries, they could decrypt otherwise secure ciphertexts without knowing the key.

Cryptographers often overlook attacks like padding oracle attacks because they usually depend on an application’s behavior and on how users can interact with the application. But if you don’t anticipate such attacks and fail to include them in your model when designing and deploying cryptography, you may have some nasty surprises.

Further Reading

We discuss encryption and its various forms in more detail throughout this book, especially how modern, secure ciphers work. Still, we can’t cover everything, and many fascinating topics won’t be discussed. For example, to learn the theoretical foundations of encryption and gain a deeper understanding of the notion of indistinguishability (IND), you should read the 1982 paper that introduced the idea of semantic security, “Probabilistic Encryption and How to Play Mental Poker Keeping Secret All Partial Information” by Goldwasser and Micali. If you’re interested in physical attacks and cryptographic hardware, the proceedings of the CHES conference are the main reference.

There are also many more types of encryption than those presented in this chapter, including attribute-based encryption, broadcast encryption, functional encryption, identity-based encryption, message-locked encryption, and proxy re-encryption, to cite but a few. For the latest research on those topics, you should check https://eprint.iacr.org/, an electronic archive of cryptography research papers.