10

RSA

The Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) cryptosystem revolutionized cryptography when it emerged in 1977 as the first public-key encryption scheme; whereas classical, symmetric-key encryption schemes use the same secret key to encrypt and decrypt messages, public-key encryption (also called asymmetric encryption) uses two keys: one is your public key, which can be used by anyone who wants to encrypt messages for you, and the other is your private key, which is required in order to decrypt messages encrypted using the public key. This magic is the reason why RSA came as a real breakthrough, and 40 years later, it’s still the paragon of public-key encryption and a workhorse of internet security. (One year prior to RSA, Diffie and Hellman had introduced the concept of public-key cryptography, but their scheme was unable to perform public-key encryption.)

RSA is above all an arithmetic trick. It works by creating a mathematical object called a trapdoor permutation, a function that transforms a number x to a number y in the same range, such that computing y from x is easy using the public key, but computing x from y is practically impossible unless you know the private key—the trapdoor. (Think of x as a plaintext and y as a ciphertext.)

In addition to encryption, RSA is also used to build digital signatures, wherein the owner of the private key is the only one able to sign a message, and the public key enables anyone to verify the signature’s validity.

In this chapter, I explain how the RSA trapdoor permutation works, discuss RSA’s security relative to the factoring problem (discussed in Chapter 9), and then explain why the RSA trapdoor permutation alone isn’t enough to build secure encryption and signatures. I also discuss ways to implement RSA and demonstrate how to attack it.

We begin with an explanation of the basic mathematical notions behind RSA.

The Math Behind RSA

When encrypting a message, RSA sees the message as a big number, and encryption consists essentially of multiplications of big numbers. Therefore, in order to understand how RSA works, we need to know what kind of big numbers it manipulates and how multiplication works on those numbers.

RSA sees the plaintext that it’s encrypting as a positive integer between 1 and n – 1, where n is a large number called the modulus. More precisely, RSA works on the numbers less than n that are co-prime with n and therefore that have no common prime factor with n. Such numbers, when multiplied together, yield another number that satisfies these criteria. We say that these numbers form a group, denoted ZN*, and call the multiplicative group of integers modulo n. (See the mathematical definition of a group in “What Is a Group?” on page 174.)

For example, consider the group Z4* of integers modulo 4. Recall from Chapter 9 that a group must include an identity element (that is, 1) and that each number x in the group must have an inverse, a number y such that x × y = 1. How do we determine that set that makes up Z4*? Based on our definitions, we know that 0 is not in the group Z4* because multiplying any number by 0 can never give 1, so 0 has no inverse. By the same token, the number 1 belongs to Z4* because 1 × 1 = 1, so 1 is its own inverse. However, the number 2 does not belong in this group because we can’t obtain 1 by multiplying 2 with another element of Z4* (the reason is that 2 isn’t co-prime with 4, because 4 and 2 share the factor of 2.) The number 3 belongs in the group Z4* because it is its own inverse within Z4*. Thus, we have Z4* = {1, 3}.

Now consider Z5*, the multiplicative group of integers modulo 5. What numbers does this set contain? The number 5 is prime, and 1, 2, 3, and 4 are all co-prime with 5, so the set of Z5* is {1, 2, 3, 4}. Let’s verify this: 2 × 3 mod 5 = 1, therefore, 2 is 3’s inverse, and 3 is 2’s inverse; note that 4 is its own inverse because 4 × 4 mod 5 = 1; finally, 1 is again its own inverse in the group.

In order to find the number of elements in a group Zn* when n isn’t prime, we use Euler’s totient function, which is written as φ(n), with φ representing the Greek letter phi. This function gives the number of elements co-prime with n, which is the number of elements in Zn*. As a rule, if n is a product of prime numbers n = p1 × p2 × . . . × pm, the number of elements in the group Zn* is the following:

φ(n) = (p1 − 1) × (p2 − 1) × ... × (pm − 1)

RSA only deals with numbers n that are the product of two large primes, usually noted as n = pq. The associated group ZN* will then contain φ(n) = (p – 1)(q – 1) elements. By expanding this expression, we get the equivalent definition φ(n) = n – p – q + 1, or φ(n) = (n + 1) – (p + q), which expresses more intuitively the value of φ(n) relative to n. In other words, all but (p + q) numbers between 1 and n – 1 belong to ZN* and are “valid numbers” in RSA operations.

The RSA Trapdoor Permutation

The RSA trapdoor permutation is the core algorithm behind RSA-based encryption and signatures. Given a modulus n and number e, called the public exponent, the RSA trapdoor permutation transforms a number x from the set Zn* into a number y = xe mod n. In other words, it calculates the value that’s equal to x multiplied by itself e times modulo n and then returns the result. When we use the RSA trapdoor permutation to encrypt, the modulus n and the exponent e make up the RSA public key.

In order to get x back from y, we use another number, denoted d, to compute the following:

yd mod n = (xe)d mod n = xed mod n = x

Because d is the trapdoor that allows us to decrypt, it is part of the private key in an RSA key pair, and, unlike the public key, it should always be kept secret. The number d is also called the secret exponent.

Obviously, d isn’t just any number; it’s the number such that e multiplied by d is equivalent to 1, and therefore such that xed mod n = x for any x. More precisely, we must have ed = 1 mod φ(n) in order to get xed = x1 = x and to decrypt the message correctly. Note that we compute modulo φ(n) and not modulo n here because exponents behave like the indexes of elements of Zn* rather than as the elements themselves. Because Zn* has φ(n) elements, the index must be less than φ(n).

The number φ(n) is crucial to RSA’s security. In fact, finding φ(n) for an RSA modulus n is equivalent to breaking RSA, because the secret exponent d can easily be derived from φ(n) and e, by computing e’s inverse. Hence p and q should also be secret, since knowing p or q gives φ(n) by computing (p – 1)(q – 1) = φ(n).

NOTE

φ(n) is also called the order of the group Zn*; the order is an important characteristic of a group, which is also essential to other public-key systems such as Diffie–Hellman and elliptic curve cryptography.

RSA Key Generation and Security

Key generation is the process by which an RSA key pair is created, namely a public key (modulus n and public exponent e) and its private key (secret exponent d). The numbers p and q (such that n = pq) and the order φ(n) should also be secret, so they’re often seen as part of the private key.

In order to generate an RSA key pair, we first pick two random prime numbers, p and q, and then compute φ(n) from these, and we compute d as the inverse of e. To show how this works, Listing 10-1 uses SageMath (http://www.sagemath.org/), an open-source Python-like environment that includes many mathematical packages.

❶ sage: p = random_prime(2^32); p

1103222539

❷ sage: q = random_prime(2^32); q

17870599

❸ sage: n = p*q; n

c

❹ sage: phi = (p-1)*(q-1); phi

36567230045260644

❺ sage: e = random_prime(phi); e

13771927877214701

❻ sage: d = xgcd(e, phi)[1]; d

15417970063428857

❼ sage: mod(d*e, phi)

1

Listing 10-1: Generating RSA parameters using SageMath

NOTE

In order to avoid multiple pages of output, I’ve used a 64-bit modulus n in Listing 10-1, but in practice an RSA modulus should be at least 2048 bits.

We use the random_prime() function to pick random primes p ❶ and q ❷, which are lower than a given argument. Next, we multiply p and q to get the modulus n ❸ and φ(n), which is the variable phi ❹. We then generate a random public exponent, e ❺, by picking a random prime less than phi in order to ensure that e will have an inverse modulo phi. We then generate the associated private exponent d by using the xgcd() function from Sage ❻. This function computes the numbers s and t given two numbers, a and b, with the extended Euclidean algorithm such that as + bt = GCD(a, b). Finally, we check that ed mod φ(n) = 1 ❼, to ensure that d will work correctly to invert the RSA permutation.

Now we can apply the trapdoor permutation, as shown in Listing 10-2.

❶ sage: x = 1234567

❷ sage: y = power_mod(x, e, n); y

19048323055755904

❸ sage: power_mod(y, d, n)

1234567

Listing 10-2: Computing the RSA trapdoor permutation back and forth

We assign the integer 1234567 to x ❶ and then use the function power_mod(x, e, n), the exponentiation modulo n, or xe mod n in equation form, to calculate y ❷. Having computed y = xe mod n, we compute yd mod n ❸ with the trapdoor d to return the original x.

But how hard is it to find x without the trapdoor d? An attacker who can factor big numbers can break RSA by recovering p and q and then φ(n) in order to compute d from e. But that’s not the only risk. Another risk to RSA lies in an attacker’s ability to compute x from xe mod n, or e th roots modulo n, without necessarily factoring n. Both risks seem closely connected, though we don’t know for sure whether they are equivalent.

Assuming that factoring is indeed hard and that finding e th roots is about as hard, RSA’s security level depends on three factors: the size of n, the choice of p and q, and how the trapdoor permutation is used. If n is too small, it could be factored in a realistic amount of time, revealing the private key. To be safe, n should at least be 2048 bits long (a security level of about 90 bits, requiring a computational effort of about 290 operations), but preferably 4096 bits long (a security level of approximately 128 bits). The values p and q should be unrelated random prime numbers of similar size. If they are too small, or too close together, it becomes easier to determine their value from n. Finally, the RSA trapdoor permutation should not be used directly for encryption or signing, as I’ll discuss shortly.

Encrypting with RSA

Typically, RSA is used in combination with a symmetric encryption scheme, where RSA is used to encrypt a symmetric key that is then used to encrypt a message with a cipher such as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). But encrypting a message or symmetric key with RSA is more complicated than simply converting the target to a number x and computing xe mod n.

In the following subsections, I explain why a naive application of the RSA trapdoor permutation is insecure, and how strong RSA-based encryption works.

Breaking Textbook RSA Encryption’s Malleability

Textbook RSA encryption is the phrase used to describe the simplistic RSA encryption scheme wherein the plaintext contains only the message you want to encrypt. For example, to encrypt the string RSA, we would first convert it to a number by concatenating the ASCII encodings of each of the three letters as a byte: R (byte 52), S (byte 53), and A (byte 41). The resulting byte string 525341 is equal to 5395265 when converted to decimal, which we might then encrypt by computing 5395265e mod n. Without knowing the secret key, there would be no way to decrypt the message.

However, textbook RSA encryption is deterministic: if you encrypt the same plaintext twice, you’ll get the same ciphertext twice. That’s one problem, but there’s a bigger problem—given two textbook RSA ciphertexts y1 = x1e mod n and y2 = x2e mod n, you can derive the ciphertext of x1 × x2 by multiplying these two ciphertexts together, like this:

y1 × y2 mod n = x1e × x2e mod n = (x1 × x2)e mod n

The result is (x1 × x2)e mod n, the ciphertext of the message x1 × x2 mod n. Thus an attacker could create a new valid ciphertext from two RSA ciphertexts, allowing them to compromise the security of your encryption by letting them deduce information about the original message. We say that this weakness makes textbook RSA encryption malleable. (Of course, if you know x1 and x2, you can compute (x1 × x2)e mod n, too, but if you only know y1 and y2, you should not be able to multiply ciphertexts and get a ciphertext of the multiplied plaintexts.)

Strong RSA Encryption: OAEP

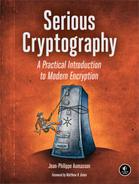

In order to make RSA ciphertexts nonmalleable, the ciphertext should consist of the message data and some additional data called padding, as shown in Figure 10-1. The standard way to encrypt with RSA in this fashion is to use Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding (OAEP), commonly referred to as RSA-OAEP. This scheme involves creating a bit string as large as the modulus by padding the message with extra data and randomness before applying the RSA function.

Figure 10-1: Encrypting a symmetric key, K, with RSA using (n, e) as a public key

NOTE

OAEP is referred to as RSAES-OAEP in official documents such as the PKCS#1 standard by the RSA company and NIST’s Special Publication 800-56B. OAEP improves on the earlier method now called PKCS#1 v1.5, which is one of the first in a series of Public-Key Cryptography Standards (PKCS) created by RSA. It is markedly less secure than OAEP, yet is still used in many systems.

OAEP’s Security

OAEP uses a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) to ensure the indistinguishability and nonmalleability of ciphertexts by making the encryption probabilistic. It has been proven secure as long as the RSA function and the PRNG are secure and, to a lesser extent, as long as the hash functions aren’t too weak. You should use OAEP whenever you need to encrypt with RSA.

How OAEP Encryption Works

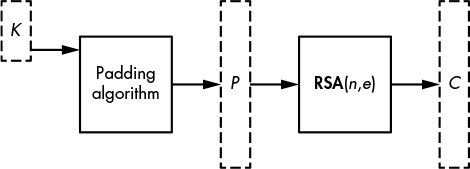

In order to encrypt with RSA in OAEP mode, you need a message (typically a symmetric key, K), a PRNG, and two hash functions. To create the ciphertext, you use a given modulus n long of m bytes (that is, 8m bits, and therefore an n lower than 28m). To encrypt K, the encoded message is formed as M = H || 00 . . . 00 || 01 || K, where H is an h-byte constant defined by the OAEP scheme, followed by as many 00 bytes as needed and a 01 byte. This encoded message, M, is then processed as described next and as depicted in Figure 10-2.

Figure 10-2: Encrypting a symmetric key, K, with RSA-OAEP, where H is a fixed parameter and R is random bits

Next, you generate an h-byte random string R and set M = M ⊕ Hash1(R), where Hash1(R) is as long as M. You then set R = R ⊕ Hash2(M), where Hash2(M) is as long as R. Now you use these new values of M and R to form an m-byte string P = 00 || M || R, which is as long as the modulus n and which can be converted to an integer number less than n. The result of this conversion is the number x, which is then used to compute the RSA function xe mod n to get the ciphertext.

To decrypt a ciphertext y, you would first compute x = yd mod n and, from this, recover the final values of M and R. Next, you would retrieve M’s initial value by computing M ⊕ Hash1(R ⊕ Hash2(M)). Finally, you would verify that M is of the form H || 00 . . . 00 || 01 || K, with an h-byte H and 00 bytes followed by a 01 byte.

In practice, the parameters m and h (the length of the modulus and the length of Hash2’s output, respectively) are typically m = 256 bytes (for 2048-bit RSA) and h = 32 (using SHA-256 as Hash2). This leaves m – h – 1 = 223 bytes for M, of which up to m – 2h – 2 = 190 bytes are available for K (the “– 2” is due to the separator 01 byte in M). The Hash1 hash value is then composed of m – h – 1 = 223 bytes, which is longer than the hash value of any common hash function.

NOTE

In order to build a hash with such an unusual output length, the RSA standard documents specify the use of the mask generating function technique to create hash functions that return arbitrarily large hash values from any hash function.

Signing with RSA

Digital signatures can prove that the holder of the private key tied to a particular digital signature signed some message and that the signature is authentic. Because no one other than the private key holder knows the private exponent d, no one can compute a signature y = xd mod n from some value x, but everyone can verify ye mod n = x given the public exponent e. That verified signature can be used in a court of law to demonstrate that the private-key holder did sign some particular message—a property of undeniability called nonrepudiation.

It’s tempting to see RSA signatures as the converse of encryption, but they are not. Signing with RSA is not the same as encrypting with the private key. Encryption provides confidentiality whereas a digital signature is used to prevent forgeries. The most salient example of this difference is that it’s okay for a signature scheme to leak information on the message signed, because the message is not secret. For example, a scheme that reveals parts of the messages could be a secure signature scheme but not a secure encryption scheme.

Due to the processing overhead required, public-key encryption can only process short messages, which are usually secret keys rather than actual messages. A signature scheme, however, can process messages of arbitrary sizes by using their hash values Hash(M) as a proxy, and it can be deterministic yet secure. Like RSA-OAEP, RSA-based signature schemes can use a padding scheme, but they can also use the maximal message space allowed by the RSA modulus.

Breaking Textbook RSA Signatures

What we call a textbook RSA signature is the method that signs a message, x, by directly computing y = xd mod n, where x can be any number between 0 and n – 1. Like textbook encryption, textbook RSA signing is simple to specify and implement but also insecure in the face of several attacks. One such attack involves a trivial forgery: upon noticing that 0d mod n = 0, 1d mod n = 1, and (n – 1)d mod n = n – 1, regardless of the value of the private key d, an attacker can forge signatures of 0, 1, or n – 1 without knowing d.

More worrying is the blinding attack. For example, say you want to get a third party’s signature on some incriminating message, M, that you know they would never knowingly sign. To launch this attack, you could first find some value, R, such that ReM mod n is a message that your victim would knowingly sign. Next, you would convince them to sign that message and to show you their signature, which is equal to S = (R eM)d mod n, or the message raised to the power d. Now, given that signature, you can derive the signature of M, namely M d, with the aid of some straightforward computations.

Here’s how this works: because S can be written as (R eM)d = RedM d, and because Red = R is equal to Red = R (by definition), we have S = (R eM)d = RM d. To obtain M d, we simply divide S by R, as follows, to obtain the signature:

S/R = RM d/R = M d

As you can see, this is a practical and powerful attack.

The PSS Signature Standard

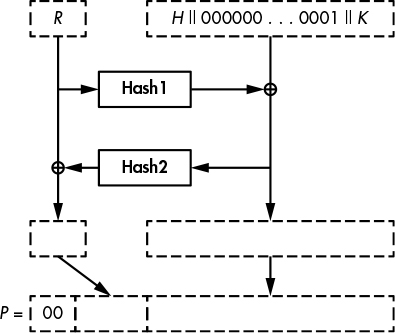

The RSA Probabilistic Signature Scheme (PSS) is to RSA signatures what OAEP is to RSA encryption. It was designed to make message signing more secure, thanks to the addition of padding data.

As shown in Figure 10-3, PSS combines a message narrower than the modulus with some random and fixed bits before RSAing the results of this padding process.

Figure 10-3: Signing a message, M, with RSA and with the PSS standard, where (n, d) is the private key

Like all public-key signature schemes, PSS works on a message’s hash rather than on the message itself. Signing Hash(M) is secure as long as the hash function is collision resistant. One particular benefit of PSS is that you can use it to sign messages of any length, because after hashing a message, you’ll obtain a hash value of the same length regardless of the message’s original length. The hash’s length is typically 256 bits, with the hash function SHA-256.

Why not sign by just running OAEP on Hash(M)? Unfortunately, you can’t. Although similar to PSS, OAEP has only been proven secure for encryption, not for signature.

Like OAEP, PSS also requires a PRNG and two hash functions. One, Hash1, is a typical hash with h-byte hash values such as SHA-256. The other, Hash2, is a wide-output hash like OAEP’s Hash2.

The PSS signing procedure for message M works as follows (where h is Hash1’s output length):

Pick an r-byte random string R using the PRNG.

Form an encoded message M′ = 0000000000000000 || Hash1(M) || R, long of h + r + 8 bytes (with eight zero bytes at the beginning).

Compute the h-byte string H = Hash1(M′).

Set L = 00 . . . 00 || 01 || R, or a sequence of 00 bytes followed by a 01 byte and then R, with a number of 00 bytes such that L is long of m – h – 1 bytes (the byte width m of the modulus minus the hash length h minus 1).

Set L = L ⊕ Hash2(H), thus replacing the previous value of L with a new value.

Convert the m-byte string P = L || H || BC to a number, x, lower than n. Here, the byte BC is a fixed value appended after H.

Given the value of x just obtained, compute the RSA function xd mod n to obtain the signature.

To verify a signature given a message, M, you compute Hash1(M) and use the public exponent e to retrieve L and H and then M′ from the signature, checking the padding’s correctness at each step.

In practice, the random string R (called a salt in the RSA-PSS standard) is usually as long as the hash value. For example, if you use n = 2048 bits and SHA-256 as the hash, the value L is long of m – h – 1 = 256 – 32 – 1 =223 bytes, and the random string R would typically be 32 bytes.

Like OAEP, PSS is provably secure, standardized, and widely deployed. Also like OAEP, it looks needlessly complex and is prone to implementation errors and mishandled corner cases. But unlike RSA encryption, there’s a way to get around this extra complexity with a signature scheme that doesn’t even need a PRNG, thus reducing the risk of insecure RSA signatures caused by an insecure PRNG, as discussed next.

Full Domain Hash Signatures

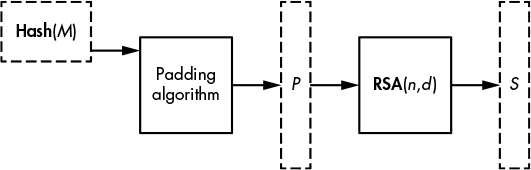

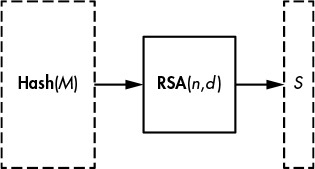

Full Domain Hash (FDH) is the simplest signature scheme you can imagine. To implement it, you simply convert the byte string Hash(M) to a number, x, and create the signature y = xd mod n, as shown in Figure 10-4.

Figure 10-4: Signing a message with RSA using the Full Domain Hash technique

Signature verification is straightforward, too. Given a signature that is a number y, you compute x = ye mod n and compare the result with Hash(M). It’s boringly simple, deterministic, yet secure. So why bother with the complexity of PSS?

The main reason is that PSS was released after FDH, in 1996, and it has a security proof that inspires more confidence than FDH. Specifically, its proof offers slightly higher security guarantees than the proof of FDH, and its use of randomness helped strengthen that proof.

These stronger theoretical guarantees are the main reason cryptographers prefer PSS over FDH, but most applications using PSS today could switch to FDH with no meaningful security loss. In some contexts, however, a viable reason to use PSS instead of FDH is that PSS’s randomness protects it from some attacks on its implementation, such as the fault attacks we’ll discuss in “How Things Can Go Wrong” on page 196.

RSA Implementations

I sincerely hope you’ll never have to implement RSA from scratch. If you’re asked to, run as fast as you can and question the sanity of the person who asked you to do so. It took decades for cryptographers and engineers to develop RSA implementations that are fast, sufficiently secure, and hopefully free of debilitating bugs, so you really don’t want to reinvent RSA. Even with all the documentation available, it would take months to complete this daunting task.

Typically, when implementing RSA, you’ll use a library or API that provides the necessary functions to carry out RSA operations. For example, the Go language has the following function in its crypto package (from https://www.golang.org/src/crypto/rsa/rsa.go):

func EncryptOAEP(hash hash.Hash, random io.Reader, pub *PublicKey, msg []byte,

label []byte) (out []byte, err error)

The function EncryptOAEP() takes a hash value, a PRNG, a public key, a message, and a label (an optional parameter of OAEP), and returns a signature and an error code. When you call EncryptOAEP(), it calls encrypt() to compute the RSA function given the padded data, as shown in Listing 10-3.

func encrypt(c *big.Int, pub *PublicKey, m *big.Int) *big.Int {

e := big.NewInt(int64(pub.E))

c.Exp(m, e, pub.N)

return c

}

Listing 10-3: Implementing the core RSA encryption function from the Go language cryptography library

The main operation shown in Listing 10-3 is c.Exp(m, e, pub.N), which raises a message, m, to the power e modulo pub.N, and assigns the result to the variable c.

If you choose to implement RSA instead of using a readily available library function, be sure to rely on an existing big-number library, which is a set of functions and types that allow you to define and compute arithmetic operations on large numbers thousands of bits long. For example, you might use the GNU Multiple Precision (GMP) arithmetic library in C, or Go’s big package. (Believe me, you don’t want to implement big-number arithmetic yourself.)

Even if you just use a library function when implementing RSA, be sure that you understand how the internals work in order to measure the risks.

Fast Exponentiation Algorithm: Square-and-Multiply

The operation of raising x to the power e, when computing xe mod n, is called exponentiation. When we’re working with big numbers, as with RSA, this operation can be extremely slow if naively implemented. But how do we do this efficiently?

The naive way to compute xe mod n takes e – 1 multiplications, as shown in the pseudocode algorithm in Listing 10-4.

expModNaive(x, e, n) {

y = x

for i = 1 to e – 1 {

y = y * x mod n

}

return y

}

Listing 10-4: A naive exponentiation algorithm in pseudocode

This algorithm is simple but highly inefficient. One way to get the same result exponentially faster is to square rather than multiply exponents until the correct value is reached. This family of methods is called square-and-multiply, or exponentiation by squaring or binary exponentiation.

For example, say that we want to compute 365537 mod 36567232109354321. (The number 65537 is the public exponent used in most RSA implementations.) We could multiply the number 3 by itself 65536 times, or we could approach this problem with the understanding that 65537 can be written as 216 + 1 and use a series of squaring operations. Essentially, we do the following:

Initialize a variable, y = 3, and then compute the following squaring (y2) operations:

Set y = y2 mod n (now y = 32 mod n).

Set y = y2 mod n (now y = (32)2 mod n = 34 mod n).

Set y = y2 mod n (now y = (34)2 = 38 mod n).

Set y = y2 mod n (now y = (38)2 = 316 mod n).

Set y = y2 mod n (now y = (316)2= 332 mod n).

And so on until y = 365536, by performing 16 squarings.

To get the final result, we return 3 × y mod n = 365537 mod n = 26652909283612267. In other words, we compute the result with only 17 multiplications rather than 65536 with the naive method.

More generally, a square-and-multiply method works by scanning the exponent’s bits one by one, from left to right, computing the square for each exponent’s bit to double the exponent’s value, and multiplying by the original number for each bit with a value of 1 encountered. In the preceding example, the exponent 65537 is 10000000000000001 in binary, and we squared y for each new bit and multiplied by the original number 3 only for the very first and last bits.

Listing 10-5 shows how this would work as a general algorithm in pseudocode to compute xe mod n when the exponent e consists of bits em – 1em – 2 . . . e1e0, where e0 is the least significant bit.

expMod(x, e, n) {

y = x

for i = m – 1 to 0 {

y = y * y mod n

if ei == 1 then

y = y * x mod n

}

return y

}

Listing 10-5: A fast exponentiation algorithm in pseudocode

The expMod() algorithm shown in Listing 10-5 runs in time O(m), whereas the naive algorithm runs in time O(2m), where m is the bit length of the exponent. Here, O() is the asymptotic complexity notation introduced in Chapter 9.

Real systems often implement variants of this simplest square-and-multiply method. One such variant is the sliding window method, which considers blocks of bits rather than individual bits to perform a given multiplication operation. For example, see the function expNN() of the Go language, whose source code is available at https://golang.org/src/math/big/nat.go.

How secure are these square-and-multiply exponentiation algorithms? Unfortunately, the tricks to speed the process up often result in increased vulnerability against some attacks. Let’s see what can go wrong.

The weakness in these algorithms is due to the fact that the exponentiation operations are heavily dependent on the exponent’s value. The if operation shown in Listing 10-5 takes a different branch based on whether an exponent’s bit is 0 or 1. If a bit is 1, an iteration of the for loop will be slower than it will be for 0, and attackers who monitor the execution time of the RSA operation can exploit this time difference to recover a private exponent. This is called a timing attack. Attacks on hardware can distinguish 1 bit from 0 bits by monitoring the device’s power consumption and observing which iterations perform an extra multiplication to reveal which bits of the private exponent are 1.

Only a minority of cryptographic libraries implement effective defenses against timing attacks, let alone against such power-analysis attacks.

Small Exponents for Faster Public-Key Operations

Because an RSA computation is essentially the computation of an exponentiation, its performance depends on the value of the exponents used. Smaller exponents require fewer multiplications and therefore can make the exponentiation computation much faster.

The public exponent e can in principle be any value between 3 and φ(n) – 1, as long as e and φ(n) are co-prime. But in practice you’ll only find small values of e, and most of the time e = 65537 due to concerns with encryption and signature verification speed. For example, the Microsoft Windows CryptoAPI only supports public exponents that fit in a 32-bit integer. The larger the e, the slower it is to compute xe mod n.

Unlike the size of the public exponent, the private exponent d will be about as large as n, making decryption much slower than encryption, and signing much slower than verification. Indeed, because d is secret, it must be unpredictable and therefore can’t be restricted to a small value. For example, if e is fixed to 65537, the corresponding d will usually be of the same order of magnitude as the modulus n, which would be close to 22048 if n is 2048 bits long.

As discussed in “Fast Exponentiation Algorithm: Square-and-Multiply” on page 192, raising a number to the power 65537 will only take 17 multiplications, whereas raising a number to the power of some 2048-bit number will take on the order of 3000 multiplications.

One way to determine the actual speed of RSA is to use the OpenSSL toolkit. For example, Listing 10-6 shows the results of 512-, 1024-, 2048-, and 4096-bit RSA operations on my MacBook, which is equipped with an Intel Core i5-5257U clocked at 2.7 GHz.

$ openssl speed rsa512 rsa1024 rsa2048 rsa4096

Doing 512 bit private rsa's for 10s: 161476 512 bit private RSA's in 9.59s

Doing 512 bit public rsa's for 10s: 1875805 512 bit public RSA's in 9.68s

Doing 1024 bit private rsa's for 10s: 51500 1024 bit private RSA's in 8.97s

Doing 1024 bit public rsa's for 10s: 715835 1024 bit public RSA's in 8.45s

Doing 2048 bit private rsa's for 10s: 13111 2048 bit private RSA's in 9.65s

Doing 2048 bit public rsa's for 10s: 288772 2048 bit public RSA's in 9.68s

Doing 4096 bit private rsa's for 10s: 1273 4096 bit private RSA's in 9.71s

Doing 4096 bit public rsa's for 10s: 63987 4096 bit public RSA's in 8.50s

OpenSSL 1.0.2g 1 Mar 2016

--snip--

sign verify sign/s verify/s

rsa 512 bits 0.000059s 0.000005s 16838.0 193781.5

rsa 1024 bits 0.000174s 0.000012s 5741.4 84714.2

rsa 2048 bits 0.000736s 0.000034s 1358.7 29831.8

rsa 4096 bits 0.007628s 0.000133s 131.1 7527.9

Listing 10-6: Benchmarks of RSA operations using the OpenSSL toolkit

How much slower is verification compared to signature generation? To get an idea, we can compute the ratio of the verification time over signature time. The benchmarks in Listing 10-6 show that I’ve got verification-over-signature speed ratios of approximately 11.51, 14.75, 21.96, and 57.42 for 512-, 1024-, 2048-, and 4096-bit moduli sizes, respectively. The gap grows with the modulus size because the number of multiplications for e operations will remain constant with respect to the modulus size (for example, 17 when e = 65537), while private-key operations will always need more multiplications for a greater modulus because d will grow accordingly.

But if small exponents are so nice, why use 65537 and not something like 3? It would actually be fine (and faster) to use 3 as an exponent when implementing RSA with a secure scheme such as OAEP, PSS, or FDH. Cryptographers avoid doing so, however, because when e = 3, less secure schemes make certain types of mathematical attacks possible. The number 65537 is large enough to avoid such low-exponent attacks, and it has just one instance in which a bit is 1, thanks to its low Hamming weight, which decreases the computational time. 65537 is also special for mathematicians: it’s the fourth Fermat number, or a number of the form

2(2n) + 1

because it’s equal to 216 + 1, where 16 = 24, but that’s just a curiosity mostly irrelevant for cryptographic engineers.

The Chinese Remainder Theorem

The most common trick to speed up decryption and signature verification (that is, the computation of yd mod n) is the Chinese remainder theorem (CRT). It makes RSA about four times faster.

The Chinese remainder theorem allows for faster decryption by computing two exponentiations, modulo p and modulo q, rather than simply modulo n. Because p and q are much smaller than n, it’s faster to perform two “small” exponentiations than a single “big” one.

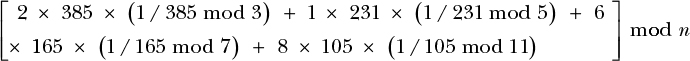

The Chinese remainder theorem isn’t specific to RSA. It’s a general arithmetic result that, in its simplest form, states that if n = n1n2n3 . . . , where the nis are pairwise co-prime (that is, GCD(ni, nj) = 1 for any distinct i and j), then the value x mod n can be computed from the values x mod n1, x mod n2, x mod n3, . . . . For example, say we have n = 1155, which we write as the product of prime factors 3 × 5 × 7 × 11. We want to determine the number x that satisfies x mod 3 = 2, x mod 5 = 1, x mod 7 = 6, and x mod 11 = 8. (I’ve chosen 2, 1, 6, and 8 arbitrarily.)

To find x using the Chinese remainder theorem, we can compute the sum P(n1) + P(n2) + . . . , where P(ni) is defined as follows:

P(ni) = (x mod ni) × n / ni × (1 / (n / ni) mod ni) mod n

Note that the second term, n/ni, is equal to the product of all other factors than this ni.

To apply this formula to our example and recover our x mod 1155, we take the arbitrary values 2, 1, 6, and 8; we compute P(3), P(5), P(7), and P(8); and then we add them together to get the following expression:

Here, I’ve just applied the preceding definition of P(ni). (The math behind the way each number was found is straightforward, but I won’t detail it here.) This expression can then be reduced to [770 + 231 + 1980 + 1680] mod n = 41, and indeed 41 is the number I had picked for this example, so we’ve got the correct result.

Applying the CRT to RSA is simpler than the previous example, because there are only two factors for each n (namely p and q). Given a ciphertext y to decrypt, instead of computing yd mod n, you use the CRT to compute xp = ys mod p, where s = d mod (p – 1) and xq = yt mod q, where t = d mod (q – 1). You now combine these two expressions and compute x to be the following:

x = xp × q × (1/q mod p) + xq × p × (1/p mod q) mod n

And that’s it. This is faster than square-and-multiply because the multiplication-heavy operations are carried out on modulo p and q, numbers that are twice as small as n.

NOTE

In the final operation, the two numbers q × (1/q mod p) and p × (1/p mod q) can be computed in advance, which means only two multiplications and an addition of modulo n need to be computed to find x.

Unfortunately, there’s a security caveat attached to these techniques, as I’ll discuss next.

How Things Can Go Wrong

Even more beautiful than the RSA scheme itself is the range of attacks that work either because the implementation leaks (or can be made to leak) information on its internals or because RSA is used insecurely. I discuss two classic examples of these types of attacks in the sections that follow.

The Bellcore Attack on RSA-CRT

The Bellcore attack on RSA is one of the most important attacks in the history of RSA. When first discovered in 1996, it stood out because it exploited RSA’s vulnerability to fault injections—attacks that force a part of the algorithm to misbehave and thus yield incorrect results. For example, hardware circuits or embedded systems can be temporarily perturbed by suddenly altering their voltage supply or by beaming a laser pulse to a carefully chosen part of a chip. Attackers can then exploit the resulting faults in an algorithm’s internal operation by observing the impact on the final result. For example, comparing the correct result with a faulty one can provide information on the algorithm’s internal values, including secret values.

The Bellcore attack is such a fault attack. It works on RSA signature schemes that use the Chinese remainder theorem and that are deterministic—meaning that it works on FDH, but not on PSS, which is probabilistic.

To understand how the Bellcore attack works, recall from the previous section that with CRT, the result that is equal to xd mod n is obtained by computing the following, where xp = ys mod p and xq = yt mod q:

x = xp × q × (1/q mod p) + xq × p × (1/p mod q) mod n

Now assume that an attacker induces a fault in the computation of xq so that you end up with some incorrect value, which differs from the actual xq. Let’s call this incorrect value xq′ and call the final result obtained x′. The attacker can then subtract the incorrect signature x′ from the correct signature x to factor n, which results in the following:

x − x′ = (xq − xq′) × p × (1/p mod q) mod n

The value x – x′ is therefore a multiple of p, so p is a divisor of x – x′. Because p is also a divisor of n, the greatest common divisor of n and x – x′ yields p, GCD(x – x′, n) = p. We can then compute q = n/p and d, resulting in a total break of RSA signatures.

A variant of this attack works when you don’t know the correct signature but only know the message is signed. There’s also a similar fault attack on the modulus value, rather than on the CRT values computation, but I won’t go into detail on that here.

Sharing Private Exponents or Moduli

Now I’ll show you why your public key shouldn’t have the same modulus n as that of someone else.

Different private keys belonging to different systems or persons should obviously have different private exponents, d, even if the keys use different moduli, or you could try your own value of d to decrypt messages encrypted for other entities, until you hit one that shares the same d. By the same token, different key pairs should have different n values, even if they have different ds, because p and q are usually part of the private key. Hence, if we share the same n and thus the same p and q, I can compute your private key from your public key e using p and q.

What if my private key is simply the pair (n, d1), and your private key is (n, d2) and your public key is (n, e2)? Say that I know n but not p and q, so I can’t directly compute your private exponent d2 from your public exponent e2. How would you compute p and q from a private exponent d only? The solution is a bit technical, but elegant.

Remember that d and e satisfy ed = kφ(n) + 1, where φ(n) is secret and could give us p and q directly. We don’t know k or φ(n), but we can compute kφ(n) = ed – 1.

What can we do with this value kφ(n)? A first observation is that, according to Euler’s theorem, we know that for any number a co-prime with n, aφ(N) = 1 mod n. Therefore, modulo n we have the following:

akφ(n) = (aφ(n))k = 1k = 1

A second observation is that, because kφ(n) is an even number, we can write it as 2st for some numbers s and t. That is, we’ll be able to write akφ(n) = 1 mod n under the form x2 = 1 mod n for some x easily computed from kφ(n). Such an x is called a root of unity.

The key observation is that x2 = 1 mod n is equivalent to saying that the value x2 – 1 = (x – 1)(x + 1) divides n. In other words, x – 1 or x + 1 must have a common factor with n, which can give us the factorization of n.

Listing 10-7 shows a Python implementation of this method where, in order to find the factors p and q from n and d, we use small, 64-bit numbers for the sake of simplicity.

from math import gcd

n = 36567232109354321

e = 13771927877214701

d = 15417970063428857

❶ kphi = d*e - 1

t = kphi

❷ while t % 2 == 0:

t = divmod(t, 2)[0]

❸ a = 2

while a < 100:

❹ k = t

while k < kphi:

x = pow(a, k, n)

❺ if x ! = 1 and x ! = (n - 1) and pow(x, 2, n) == 1:

❻ p = gcd(x - 1, n)

break

k = k*2

a = a + 2

q = n//p

❼ assert (p*q) == n

print('p = ', p)

print('q = ', q)

Listing 10-7: A python program that computes the prime factors p and q from the private exponent d

This program determines kφ(n) from e and d ❶ by finding the number t such that kφ(n) = 2st, for some s ❷. Then it looks for a and k such that (ak)2 = 1 mod n ❸, using t as a starting point for k ❹. When this condition is satisfied ❺, we’ve found a solution. It then determines the factor p ❻ and verifies ❼ that the value of pq equals the value of n. It then prints the resulting values of p and q:

p = 2046223079

q = 17870599

The program correctly returns the two factors.

Further Reading

RSA deserves a book by itself. I had to omit many important and interesting topics, such as Bleichenbacher’s padding oracle attack on OAEP’s predecessor (the standard PKCS#1 v1.5), an attack similar in spirit to the padding oracle attack on block ciphers seen in Chapter 4. There’s also Wiener’s attack on RSA with low private exponents, and attacks using Coppersmith’s method on RSA with small exponents that potentially also have insecure padding.

To see research results related to side-channel attacks and defenses, view the CHES workshop proceedings that have run since 1999 at http://www.chesworkshop.org/. One of the most useful references while writing this chapter was Boneh’s “Twenty Years of Attacks on the RSA Cryptosystem,” a survey that reviews and explains the most important attacks on RSA. For reference specifically on timing attacks, the paper “Remote Timing Attacks Are Practical” by Brumley and Boneh, is a must-read, both for its analytical and experimental contributions. To learn more about fault attacks, read the full version of the Bellcore attack paper “On the Importance of Eliminating Errors in Cryptographic Computations” by Boneh, DeMillo, and Lipton.

The best way to learn how RSA implementations work, though sometimes painful and frustrating, is to review the source code of widely used implementations. For example, see RSA and its underlying big-number arithmetic implementations in OpenSSL, in NSS (the library used by the Mozilla Firefox browser), in Crypto++, or in other popular software, and examine their implementations of arithmetic operations as well as their defenses against timing and fault attacks.