2

RANDOMNESS

Randomness is found everywhere in cryptography: in the generation of secret keys, in encryption schemes, and even in the attacks on cryptosystems. Without randomness, cryptography would be impossible because all operations would become predictable, and therefore insecure.

This chapter introduces you to the concept of randomness in the context of cryptography and its applications. We discuss pseudorandom number generators and how operating systems can produce reliable randomness, and we conclude with real examples showing how flawed randomness can impact security.

Random or Non-Random?

You’ve probably already heard the phrase “random bits,” but strictly speaking there is no such thing as a series of random bits. What is random is actually the algorithm or process that produces a series of random bits; therefore, when we say “random bits,” we actually mean randomly generated bits.

What do random bits look like? For example, to most people, the 8-bit string 11010110 is more random than 00000000, although both have the same chance of being generated (namely, 1/256). The value 11010110 looks more random than 00000000 because it has the signs typical of a randomly generated value. That is, 11010110 has no obvious pattern.

When we see the string 11010110, our brain registers that it has about as many zeros (three) as it does ones (five), just like 55 other 8-bit strings (11111000, 11110100, 11110010, and so on), but only one 8-bit string has eight zeros. Because the pattern three-zeros-and-five-ones is more likely to occur than the pattern eight-zeros, we identify 11010110 as random and 00000000 as non-random, and if a program produces the bits 11010110, you may think that it’s random, even if it’s not. Conversely, if a randomized program produces 00000000, you’ll probably doubt that it’s random.

This example illustrates two types of errors people often make when identifying randomness:

Mistaking non-randomness for randomness Thinking that an object was randomly generated simply because it looks random.

Mistaking randomness for non-randomness Thinking that patterns appearing by chance are there for a reason other than chance.

The distinction between random-looking and actually random is crucial. Indeed, in crypto, non-randomness is often synonymous with insecurity.

Randomness as a Probability Distribution

Any randomized process is characterized by a probability distribution, which gives all there is to know about the randomness of the process. A probability distribution, or simply distribution, lists the outcomes of a randomized process where each outcome is assigned a probability.

A probability measures the likelihood of an event occurring. It’s expressed as a real number between 0 and 1 where a probability 0 means impossible and a probability of 1 means certain. For example, when tossing a two-sided coin, each side has a probability of landing face up of 1/2, and we usually assume that landing on the edge of the coin has probability zero.

A probability distribution must include all possible outcomes, such that the sum of all probabilities is 1. Specifically, if there are N possible events, there are N probabilities p1, p2, . . . , pN with p1 + p2 + . . . + pN = 1. In the case of the coin toss, the distribution is 1/2 for heads and 1/2 for tails. The sum of both probabilities is equal to 1/2 + 1/2 = 1, because the coin will fall on one of its two faces.

A uniform distribution occurs when all probabilities in the distribution are equal, meaning that all outcomes are equally likely to occur. If there are N events, then each event has probability 1/N. For example, if a 128-bit key is picked uniformly at random—that is, according to a uniform distribution—then each of the 2128 possible keys should have a probability of 1/2128.

In contrast, when a distribution is non-uniform, probabilities aren’t all equal. A coin toss with a non-uniform distribution is said to be biased, and may yield heads with probability 1/4 and tails with probability 3/4, for example.

Entropy: A Measure of Uncertainty

Entropy is the measure of uncertainty, or disorder in a system. You might think of entropy as the amount of surprise found in the result of a randomized process: the higher the entropy, the less the certainty found in the result.

We can compute the entropy of a probability distribution. If your distribution consists of probabilities p1, p2, . . . , pN, then its entropy is the negative sum of all probabilities multiplied by their logarithm, as shown in this expression:

−p1 × log(p1) − p2 × log(p2) − ... pN × log(pN)

Here the function log is the binary logarithm, or logarithm in base two. Unlike the natural logarithm, the binary logarithm expresses the information in bits and yields integer values when probabilities are powers of two. For example, log(1/2) = –1, log(1/4) = –2, and more generally log(1/2N) = –n. (That’s why we actually take the negative sum, in order to end up with a positive number.) Random 128-bit keys produced using a uniform distribution therefore have the following entropy:

2128 × (−2−128 × log(2−128)) = −log(2−128) = 128 bits

If you replace 128 by any integer n you will find that the entropy of a uniformly distributed n-bit string will be n bits.

Entropy is maximized when the distribution is uniform because a uniform distribution maximizes uncertainty: no outcome is more likely than the others. Therefore, n-bit values can’t have more than n bits of entropy.

By the same token, when the distribution is not uniform, entropy is lower. Consider the coin toss example. The entropy of a fair toss is the following:

−(1/2) × log (1/2) − (1/2) × log (1/2) = 1/2 + 1/2 = 1 bit

What if one side of the coin has a higher probability of landing face up than the other? Say heads has a probability of 1/4 and tails 3/4 (remember that the sum of all probabilities should be 1).

The entropy of such a biased toss is this:

−(3/4) × log(3/4) − (1/4) × log(1/4) ≈ −(3/4) × (−0.415) − (1/4) × (−2) ≈ 0.81 bit

The fact that 0.81 is less than the 1-bit entropy of a fair toss tells us that the more biased the coin, the less uniform the distribution and the lower the entropy. Taking this example further, if heads has a probability of 1/10, the entropy is 0.469; if the probability drops to 1/100, the entropy drops to 0.081.

NOTE

Entropy can also be viewed as a measure of information. For example, the result of a fair coin toss gives you exactly one bit of information—heads or tails—and you’re unable to predict the result of the toss in advance. In the case of the unfair coin toss, you know in advance that tails is more probable, so you can usually predict the outcome of the toss. The result of the coin toss gives you the information needed to predict the result with certainty.

Random Number Generators (RNGs) and Pseudorandom Number Generators (PRNGs)

Cryptosystems need randomness to be secure and therefore need a component from which to get their randomness. The job of this component is to return random bits when requested to do so. How is this randomness generation done? You’ll need two things:

- A source of uncertainty, or source of entropy, provided by random number generators (RNGs).

- A cryptographic algorithm to produce high-quality random bits from the source of entropy. This is found in pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs).

Using RNGs and PRNGs is the key to making cryptography practical and secure. Let’s briefly look at how RNGs work before exploring PRNGs in depth.

Randomness comes from the environment, which is analog, chaotic, uncertain, and hence unpredictable. Randomness can’t be generated by computer-based algorithms alone. In cryptography, randomness usually comes from random number generators (RNGs), which are software or hardware components that leverage entropy in the analog world to produce unpredictable bits in a digital system. For example, an RNG might directly sample bits from measurements of temperature, acoustic noise, air turbulence, or electrical static. Unfortunately, such analog entropy sources aren’t always available, and their entropy is often difficult to estimate.

RNGs can also harvest the entropy in a running operating system by drawing from attached sensors, I/O devices, network or disk activity, system logs, running processes, and user activities such as key presses and mouse movement. Such system- and human-generated activities can be a good source of entropy, but they can be fragile and manipulated by an attacker. Also, they’re slow to yield random bits.

Quantum random number generators (QRNGs) are a type of RNG that relies on the randomness arising from quantum mechanical phenomena such as radioactive decay, vacuum fluctuations, and observing photons’ polarization. These can provide real randomness, rather than just apparent randomness. However, in practice, QRNGs may be biased and don’t produce bits quickly; like the previously cited entropy sources, they need an additional component to produce reliably at high speed.

Pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) address the challenge we face in generating randomness by reliably producing many artificial random bits from a few true random bits. For example, an RNG that translates mouse movements to random bits would stop working if you stop moving the mouse, whereas a PRNG always returns pseudorandom bits when requested to do so.

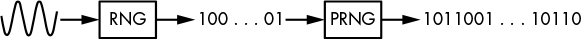

PRNGs rely on RNGs but behave differently: RNGs produce true random bits relatively slowly from analog sources, in a nondeterministic way, and with no guarantee of high entropy. In contrast, PRNGs produce random-looking bits quickly from digital sources, in a deterministic way, and with maximum entropy. Essentially, PRNGs transform a few unreliable random bits into a long stream of reliable pseudorandom bits suitable for crypto applications, as shown in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1: RNGs produce few unreliable bits from analog sources, whereas PRNGs expand those bits to a long stream of reliable bits.

How PRNGs Work

A PRNG receives random bits from an RNG at regular intervals and uses them to update the contents of a large memory buffer, called the entropy pool. The entropy pool is the PRNG’s source of entropy, just like the physical environment is to an RNG. When the PRNG updates the entropy pool, it mixes the pool’s bits together to help remove any statistical bias.

In order to generate pseudorandom bits, the PRNG runs a deterministic random bit generator (DRBG) algorithm that expands some bits from the entropy pool into a much longer sequence. As its name suggests, a DRBG is deterministic, not randomized: given one input you will always get the same output. The PRNG ensures that its DRBG never receives the same input twice, in order to generate unique pseudorandom sequences.

In the course of its work, the PRNG performs three operations, as follows:

init() Initializes the entropy pool and the internal state of the PRNG

refresh(R) Updates the entropy pool using some data, R, usually sourced from an RNG

next(N) Returns N pseudorandom bits and updates the entropy pool

The init operation resets the PRNG to a fresh state, reinitializes the entropy pool to some default value, and initializes any variables or memory buffers used by the PRNG to carry out the refresh and next operations.

The refresh operation is often called reseeding, and its argument R is called a seed. When no RNG is available, seeds may be unique values hardcoded in a system. The refresh operation is typically called by the operating system, whereas next is typically called or requested by applications. The next operation runs the DRBG and modifies the entropy pool to ensure that the next call will yield different pseudorandom bits.

Security Concerns

Let’s talk briefly about the way that PRNGs address some high-level security concerns. Specifically, PRNGs should guarantee backtracking resistance and prediction resistance. Backtracking resistance (also called forward secrecy) means that previously generated bits are impossible to recover, whereas prediction resistance (backward secrecy) means that future bits should be impossible to predict.

In order to achieve backtracking resistance, the PRNG should ensure that the transformations performed when updating the state through the refresh and next operations are irreversible so that if an attacker compromises the system and obtains the entropy pool’s value, they can’t determine the previous values of the pool or the previously generated bits. To achieve prediction resistance, the PRNG should call refresh regularly with R values that are unknown to an attacker and that are difficult to guess, thus preventing an attacker from determining future values of the entropy pool, even if the whole pool is compromised. (Even if the list of R values used were known, you’d need to know the order in which refresh and next calls were made in order to reconstruct the pool.)

The PRNG Fortuna

Fortuna is a PRNG construction used in Windows originally designed in 2003 by Niels Ferguson and Bruce Schneier. Fortuna superseded Yarrow, a 1998 design by Kelsey and Schneier now used in the macOS and iOS operating systems. I won’t provide the Fortuna specification here or show you how to implement it, but I will try to explain how it works. You’ll find a complete description of Fortuna in Chapter 9 of Cryptography Engineering by Ferguson, Schneier, and Kohno (Wiley, 2010).

Fortuna’s internal memory includes the following:

- Thirty-two entropy pools, P1, P2, . . . , P32, such that Pi is used every 2i reseeds.

- A key, K, and a counter, C (both 16 bytes). These form the internal state of Fortuna’s DRBG.

In simplest terms, Fortuna works like this:

- init() sets K and C to zero and empties the 32 entropy pools Pi, where i = 1 . . . 32.

- refresh(R) appends the data, R, to one of the entropy pools. The system chooses the RNGs used to produce R values, and it should call refresh regularly.

- next(N) updates K using data from one or more entropy pools, where the choice of the entropy pools depends mainly on how many updates of K have already been done. The N bits requested are then produced by encrypting C using K as a key. If encrypting C is not enough, Fortuna encrypts C + 1, then C + 2, and so on, to get enough bits.

Although Fortuna’s operations look fairly simple, implementing them correctly is hard. For one thing, you need to get all the details of the algorithm right—namely, how entropy pools are chosen, the type of cipher to be used in next, how to behave when no entropy is received, and so on. Although the specs define most of the details, they don’t include a comprehensive test suite to check that an implementation is correct, which makes it difficult to ensure that your implementation of Fortuna will behave as expected.

Even if Fortuna is correctly implemented, security failures may occur for reasons other than the use of an incorrect algorithm. For example, Fortuna might not notice if the RNGs fail to produce enough random bits, and as a result Fortuna will produce lower-quality pseudorandom bits, or it may stop delivering pseudorandom bits altogether.

Another risk inherent in Fortuna implementations lies in the possibility of exposing associated seed files to attackers. The data in Fortuna seed files is used to feed entropy to Fortuna through refresh calls when an RNG is not immediately available, such as immediately after a system reboot and before the system’s RNGs have recorded any unpredictable events. However, if an identical seed file is used twice, then Fortuna will produce the same bit sequence twice. Seed files should therefore be erased after being used to ensure that they aren’t reused.

Finally, if two Fortuna instances are in the same state because they are sharing a seed file (meaning they are sharing the same data in the entropy pools, including the same C and K), then the next operation will return the same bits in both instances.

Cryptographic vs. Non-Cryptographic PRNGs

There are both cryptographic and non-cryptographic PRNGs. Non-crypto PRNGs are designed to produce uniform distributions for applications such as scientific simulations or video games. However, you should never use non-crypto PRNGs in crypto applications, because they’re insecure—they’re only concerned with the quality of the bits’ probability distribution and not with their predictability. Crypto PRNGs, on the other hand, are unpredictable, because they’re also concerned with the strength of the underlying operations used to deliver well-distributed bits.

Unfortunately, most PRNGs exposed by programming languages, such as libc’s rand and drand48, PHP’s rand and mt_rand, Python’s random module, Ruby’s Random class, and so on, are non-cryptographic. Defaulting to a non-crypto PRNG is a recipe for disaster because it often ends up being used in crypto applications, so be sure to use only crypto PRNGs in crypto applications.

A Popular Non-Crypto PRNG: Mersenne Twister

The Mersenne Twister (MT) algorithm is a non-cryptographic PRNG used (at the time of this writing) in PHP, Python, R, Ruby, and many other systems. MT will generate uniformly distributed random bits without statistical bias, but it’s predictable: given a few bits produced by MT, it’s easy enough to tell which bits will follow.

Let’s look under the hood to see what makes the Mersenne Twister insecure. The MT algorithm is much simpler than that of crypto PRNGs: its internal state is an array, S, consisting of 624 32-bit words. This array is initially set to S1, S2, . . . , S624 and evolves to S2, . . . , S625, then S3, . . . , S626, and so on, according to this equation:

Sk + 624 = Sk + 397 ⊕ A((Sk ∧ 0x80000000) ∨ (Sk + 1 ∧ 0xfffffff))

Here, ⊕ denotes the bitwise XOR (^ in the C programming language), ∧ denotes the bitwise AND (& in C), ∨ denotes the bitwise OR (| in C), and A is a function that transforms some 32-bit word, x, to (x >> 1), if x’s most significant bit is 0, or to (x >> 1) ⊕ 0x9908b0df otherwise.

Notice in this equation that bits of S interact with each other only through XORs. The operators ∧ and ∨ never combine two bits of S together, but just bits of S with bits from the constants 0x80000000 and 0x7fffffff. This way, any bit from S625 can be expressed as an XOR of bits from S398, S1, and S2, and any bit from any future state can be expressed as an XOR combination of bits from the initial state S1, . . . , S624. (When you express, say, S228 + 624 = S852 as a function of S625, S228, and S229, you can in turn replace S625 by its expression in terms of S398, S1, and S2.)

Because there are exactly 624 × 32 = 19,968 bits in the initial state (or 624 32-bit words), any output bit can be expressed as an equation with at most 19,969 terms (19,968 bits plus one constant bit). That’s just about 2.5 kilobytes of data. The converse is also true: bits from the initial state can be expressed as an XOR of output bits.

Linearity Insecurity

We call an XOR combination of bits a linear combination. For example, if X, Y, and Z are bits, then the expression X ⊕ Y ⊕ Z is a linear combination, whereas (X ∧ Y) ⊕ Z is not because there’s an AND (∧). If you flip a bit of X in X ⊕ Y ⊕ Z, then the result changes as well, regardless of the value of the Y and Z. In contrast, if you flip a bit of X in (X ∧ Y) ⊕ Z, the result changes only if Y’s bit at the same position is 1. The upshot is that linear combinations are predictable, because you don’t need to know the value of the bits in order to predict how a change in their value will affect the result.

For comparison, if the MT algorithm were cryptographically strong, its equations would be nonlinear and would involve not only single bits but also AND-combinations (products) of bits, such as S1S15S182 or S17S256S257S354S498S601. Although linear combinations of those bits include at most 624 variables, nonlinear combinations allow for up to 2624 variables. It would be impossible to solve, let alone write down the whole of these equations. (Note that 2305, a much smaller number, is the estimated information capacity of the observable universe.)

The key here is that linear transformations lead to short equations (comparable in size to the number of variables), which are easy to solve, whereas nonlinear transformations give rise to equations of exponential size, which are practically unsolvable. The game of cryptographers is thus to design PRNG algorithms that emulate such complex nonlinear transformations using only a small number of simple operations.

NOTE

Linearity is just one of many security criteria. Although necessary, nonlinearity alone does not make a PRNG cryptographically secure.

The Uselessness of Statistical Tests

Statistical test suites like TestU01, Diehard, or the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) test suite are one way to test the quality of pseudorandom bits. These tests take a sample of pseudorandom bits produced by a PRNG (say, one megabyte worth), compute some statistics on the distribution of certain patterns in the bits, and compare the results with the typical results obtained for a perfect, uniform distribution. For example, some tests count the number of 1 bits versus the number of 0 bits, or the distribution of 8-bit patterns. But statistical tests are largely irrelevant to cryptographic security, and it’s possible to design a cryptographically weak PRNG that will fool any statistical test.

When you run statistical tests on randomly generated data, you will usually see a bunch of statistical indicators as a result. These are typically p-values, a common statistical indicator. These results aren’t always easy to interpret, because they’re rarely as simple as passed or failed. If your first results seem abnormal, don’t worry: they may be the result of some accidental deviation, or you may be testing too few samples. To ensure that the results you see are normal, compare them with those obtained for some reliable sample of identical size; for example, one generated with the OpenSSL toolkit using the following command:

$ openssl rand <number of bytes> -out <output file>

Real-World PRNGs

Let’s turn our attention to how to implement PRNGs in the real world. You’ll find crypto PRNGs in the operating systems (OSs) of most platforms, from desktops and laptops to embedded systems such as routers and set-top boxes, as well as virtual machines, mobile phones, and so on. Most of these PRNGs are software based, but some are pure hardware. Those PRNGs are used by applications running on the OS, and sometimes other PRNGs running on top of cryptographic libraries or applications.

Next we’ll look at the most widely deployed PRNGs: the one for Linux, Android, and many other Unix-based systems; the one in Windows; and the one in recent Intel microprocessors, which is hardware based.

Generating Random Bits in Unix-Based Systems

The device file /dev/urandom is the userland interface to the crypto PRNG of common *nix systems, and it’s what you will typically use to generate reliable random bits. Because it’s a device file, requesting random bits from /dev/urandom is done by reading it as a file. For example, the following command uses /dev/urandom to write 10MB of random bits to a file:

$ dd if=/dev/urandom of=<output file> bs=1M count=10

The Wrong Way to Use /dev/urandom

You could write a naive and insecure C program like the one shown in Listing 2-1 to read random bits, and hope for the best, but that would be a bad idea.

int random_bytes_insecure(void *buf, size_t len)

{

int fd = open("/dev/urandom", O_RDONLY);

read(fd, buf, len);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

Listing 2-1: Insecure use of /dev/urandom

This code is insecure; it doesn’t even check the return values of open() and read(), which means your expected random buffer could end up filled with zeroes, or left unchanged.

A Safer Way to Use /dev/urandom

Listing 2-2, copied from LibreSSL, shows a safer way to use /dev/urandom.

int random_bytes_safer(void *buf, size_t len)

{

struct stat st;

size_t i;

int fd, cnt, flags;

int save_errno = errno;

start:

flags = O_RDONLY;

#ifdef O_NOFOLLOW

flags |= O_NOFOLLOW;

#endif

#ifdef O_CLOEXEC

flags |= O_CLOEXEC;

#endif

fd = ❶open("/dev/urandom", flags, 0);

if (fd == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR)

goto start;

goto nodevrandom;

}

#ifndef O_CLOEXEC

fcntl(fd, F_SETFD, fcntl(fd, F_GETFD) | FD_CLOEXEC);

#endif

/* Lightly verify that the device node looks sane */

if (fstat(fd, &st) == -1 || !S_ISCHR(st.st_mode)) {

close(fd);

goto nodevrandom;

}

if (ioctl(fd, RNDGETENTCNT, &cnt) == -1) {

close(fd);

goto nodevrandom;

}

for (i = 0; i < len; ) {

size_t wanted = len - i;

ssize_t ret = ❷read(fd, (char *)buf + i, wanted);

if (ret == -1) {

if (errno == EAGAIN || errno == EINTR)

continue;

close(fd);

goto nodevrandom;

}

i += ret;

}

close(fd);

if (gotdata(buf, len) == 0) {

errno = save_errno;

return 0; /* satisfied */

}

nodevrandom:

errno = EIO;

return -1;

}

Listing 2-2: Safe use of /dev/urandom

Unlike Listing 2-1, Listing 2-2 makes several sanity checks. Compare, for example, the call to open() at ❶ and the call to read() at ❷ with those in Listing 2-1: you’ll notice that the safer code checks the return values of those functions, and upon failure closes the file descriptor and returns –1.

Differences Between /dev/urandom and /dev/random on Linux

Different Unix versions use different PRNGs. The Linux PRNG, defined in drivers/char/random.c in the Linux kernel, mainly uses the hash function SHA-1 to turn raw entropy bits into reliable pseudorandom bits. The PRNG harvests entropy from various sources (including the keyboard, mouse, disk, and interrupt timings) and has a primary entropy pool of 512 bytes, as well as a non-blocking pool for /dev/urandom and a blocking pool for /dev/random.

What’s the difference between /dev/urandom and /dev/random? The short story is that /dev/random attempts to estimate the amount of entropy and refuses to return bits if the level of entropy is too low. Although this may sound like a good idea, it’s not. For one thing, entropy estimators are notoriously unreliable and can be fooled by attackers (which is one reason why Fortuna ditched Yarrow’s entropy estimation). Furthermore, /dev/random runs out of estimated entropy pretty quickly, which can produce a denial-of-service condition, slowing applications that are forced to wait for more entropy. The upshot is that in practice, /dev/random is no better than /dev/urandom and creates more problems than it solves.

Estimating the Entropy of /dev/random

You can observe how /dev/random’s entropy estimate evolves by reading its current value in bits in /proc/sys/kernel/random/entropy_avail on Linux. For example, the shell script shown in Listing 2-3 first minimizes the entropy estimate by reading 4KB from /dev/random, waits until it reaches an estimate of 128 bits, reads 64 bits from /dev/random, and then shows the new estimate. When running the script, notice how user activity accelerates entropy recovery (bytes read are printed to stdout encoded in base64).

#!/bin/sh

ESTIMATE=/proc/sys/kernel/random/entropy_avail

timeout 3s dd if=/dev/random bs=4k count=1 2> /dev/null | base64

ent=`cat $ESTIMATE`

while [ $ent -lt 128 ]

do

sleep 3

ent=`cat $ESTIMATE`

echo $ent

done

dd if=/dev/random bs=8 count=1 2> /dev/null | base64

cat $ESTIMATE

Listing 2-3: A script showing the evolution of /dev/urandom’s entropy estimate

A sample run of Listing 2-3 gave the output shown in Listing 2-4. (Guess when I started randomly moving the mouse and hitting the keyboard to gather entropy.)

xFNX/f2R87/zrrNJ6Ibr5R1L913tl+F4GNzKb60BC+qQnHQcyA==

2

18

19

27

28

72

124

193

jq8XWCt8

129

Listing 2-4: A sample execution of the entropy estimate evolution script in Listing 2-3

As you can see in Listing 2-4, we have 193 − 64 = 129 bits of entropy left in the pool, as per /dev/random’s estimator. Does it make sense to consider a PRNG as having N less entropy bits just because N bits were just read from the PRNG? (Spoiler: it does not.)

NOTE

Like /dev/random, Linux’s getrandom() system call blocks if it hasn’t gathered enough initial entropy. However, unlike /dev/random, it won’t attempt to estimate the entropy in the system and will never block after its initialization stage. And that’s fine. (You can force getrandom() to use /dev/random and to block by tweaking its flags, but I don’t see why you’d want to do that.)

The CryptGenRandom() Function in Windows

In Windows, the legacy userland interface to the system’s PRNG is the CryptGenRandom() function from the Cryptography application programming interface (API). The CryptGenRandom() function has been replaced in recent Windows versions with the BcryptGenRandom() function in the Cryptography API: Next Generation (CNG) API. The Windows PRNG takes entropy from the kernel mode driver cng.sys (formerly ksecdd.sys), whose entropy collector is loosely based on Fortuna. As is usually the case in Windows, the process is complicated.

Listing 2-5 shows a typical C++ invocation of CryptGenRandom() with the required checks.

int random_bytes(unsigned char *out, size_t outlen)

{

static HCRYPTPROV handle = 0; /* only freed when the program ends */

if(!handle) {

if(!CryptAcquireContext(&handle, 0, 0, PROV_RSA_FULL,

CRYPT_VERIFYCONTEXT | CRYPT_SILENT)) {

return -1;

}

}

while(outlen > 0) {

const DWORD len = outlen > 1048576UL ? 1048576UL : outlen;

if(!CryptGenRandom(handle, len, out)) {

return -2;

}

out += len;

outlen -= len;

}

return 0;

}

Listing 2-5: Using the Windows CryptGenRandom() PRNG interface

Notice in Listing 2-5 that prior to calling the actual PRNG, you need to declare a cryptographic service provider (HCRYPTPROV) and then acquire a cryptographic context with CryptAcquireContext(), which increases the chances of things going wrong. For instance, the final version of the TrueCrypt encryption software was found to call CryptAcquireContext() in a way that could silently fail, leading to suboptimal randomness without notifying the user. Fortunately, the newer BCryptGenRandom() interface for Windows is much simpler and doesn’t require the code to explicitly open a handle (or at least makes it much easier to use without a handle).

A Hardware-Based PRNG: RDRAND in Intel Microprocessors

We’ve discussed only software PRNGs so far, so let’s have a look at a hardware one. The Intel Digital Random Number Generator is a hardware PRNG introduced in 2012 in Intel’s Ivy Bridge microarchitecture, and it’s based on NIST’s SP 800-90 guidelines with the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) in CTR_DRBG mode. Intel’s PRNG is accessed through the RDRAND assembly instruction, which offers an interface independent of the operating system and is in principle faster than software PRNGs.

Whereas software PRNGs try to collect entropy from unpredictable sources, RDRAND has a single entropy source that provides a serial stream of entropy data as zeroes and ones. In hardware engineering terms, this entropy source is a dual differential jamb latch with feedback; essentially, a small hardware circuit that jumps between two states (0 or 1) depending on thermal noise fluctuations, at a frequency of 800 MHz. This kind of thing is usually pretty reliable.

The RDRAND assembly instruction takes as an argument a register of 16, 32, or 64 bits and then writes a random value. When invoked, RDRAND sets the carry flag to 1 if the data set in the destination register is a valid random value, and to 0 otherwise, which means you should be sure to check the CF flag if you write assembly code directly. Note that the C intrinsics available in common compilers don’t check the CF flag but do return its value.

NOTE

Intel’s PRNG framework provides an assembly instruction other than RDRAND: the RDSEED assembly instruction returns random bits directly from the entropy source, after some conditioning or cryptographic processing. It’s intended to be able to seed other PRNGs.

Intel’s PRNG is only partially documented, but it’s built on known standards, and has been audited by the well-regarded company Cryptography Research (see their report titled “Analysis of Intel’s Ivy Bridge Digital Random Number Generator”). Nonetheless, there have been some concerns about its security, especially following Snowden’s revelations about cryptographic backdoors, and PRNGs are indeed the perfect target for sabotage. If you’re concerned but still wish to use RDRAND or RDSEED, just mix them with other entropy sources. Doing so will prevent effective exploitation of a hypothetical backdoor in Intel’s hardware or in the associated microcode in all but the most far-fetched scenarios.

How Things Can Go Wrong

To conclude, I’ll present a few examples of randomness failures. There are countless examples to choose from, but I’ve chosen four that are simple enough to understand and illustrate different problems.

Poor Entropy Sources

In 1996, the SSL implementation of the Netscape browser was computing 128-bit PRNG seeds according to the pseudocode shown in Listing 2-6, copied from Goldberg and Wagner’s page at http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~daw/papers/ddj-netscape.html.

global variable seed;

RNG_CreateContext()

(seconds, microseconds) = time of day; /* Time elapsed since 1970 */

pid = process ID; ppid = parent process ID;

a = mklcpr(microseconds);

➊ b = mklcpr(pid + seconds + (ppid << 12));

seed = MD5(a, b); /* Derivation of a 128-bit value using the hash MD5 */

mklcpr(x) /* not cryptographically significant; shown for completeness */

return ((0xDEECE66D * x + 0x2BBB62DC) >> 1);

MD5() /* a very good standard mixing function, source omitted */

Listing 2-6: Pseudocode of the Netscape browser’s generation of 128-bit PRNG seeds

The problem here is that the PIDs and microseconds are guessable values. Assuming that you can guess the value of seconds, microseconds has only 106 possible values and thus an entropy of log(106), or about 20 bits. The process ID (PID) and parent process ID (PPID) are 15-bit values, so you’d expect 15 + 15 = 30 additional entropy bits. But if you look at how b is computed at ❶, you’ll see that the overlap of three bits yields an entropy of only about 15 + 12 = 27 bits, for a total entropy of only 47 bits, whereas a 128-bit seed should have 128 bits of entropy.

Insufficient Entropy at Boot Time

In 2012, researchers scanned the whole internet and harvested public keys from TLS certificates and SSH hosts. They found that a handful of systems had identical public keys, and in some cases very similar keys (namely, RSA keys with shared prime factors): in short, two numbers, n = pq and n′ = p′q′, with p = p′, whereas normally all ps and qs should be different in distinct modulus values.

After further investigation, it turned out that many devices generated their public key early, at first boot, before having collected enough entropy, despite using an otherwise decent PRNG (typically /dev/urandom). PRNGs in different systems ended up producing identical random bits due to a same base entropy source (for example, a hardcoded seed).

At a high level, the presence of identical keys is due to key-generation schemes like the following, in pseudocode:

prng.seed(seed)

p = prng.generate_random_prime()

q = prng.generate_random_prime()

n = p*q

If two systems run this code given an identical seed, they’ll produce the same p, the same q, and therefore the same n.

The presence of shared primes in different keys is due to key-generation schemes where additional entropy is injected during the process, as shown here:

prng.seed(seed)

p = prng.generate_random_prime()

prng.add_entropy()

q = prng.generate_random_prime()

n = p*q

If two systems run this code with the same seed, they’ll produce the same p, but the injection of entropy through prng.add_entropy() will ensure distinct qs.

The problem with shared prime factors is that given n = pq and n′ = pq′, it’s trivial to recover the shared p by computing the greatest common divisor (GCD) of n and n′. For the details, see the paper “Mining Your Ps and Qs” by Heninger, Durumeric, Wustrow, and Halderman, available at https://factorable.net/.

Non-cryptographic PRNG

Earlier we discussed the difference between crypto and non-crypto PRNGs and why the latter should never be used for crypto applications. Alas, many systems overlook that detail, so I thought I should give you at least one such example.

The popular MediaWiki application runs on Wikipedia and many other wikis. It uses randomness to generate things like security tokens and temporary passwords, which of course should be unpredictable. Unfortunately, a now obsolete version of MediaWiki used a non-crypto PRNG, the Mersenne Twister, to generate these tokens and passwords. Here’s a snippet from the vulnerable MediaWiki source code. Look for the function called to get a random bit, and be sure to read the comments.

/**

* Generate a hex-y looking random token for various uses.

* Could be made more cryptographically sure if someone cares.

* @return string

*/

function generateToken( $salt = '' ) {

$token = dechex(mt_rand()).dechex(mt_rand());

return md5( $token . $salt );

}

Did you notice mt_rand() in the preceding code? Here, mt stands for Mersenne Twister, the non-crypto PRNG discussed earlier. In 2012, researchers showed how to exploit the predictability of Mersenne Twister to predict future tokens and temporary passwords, given a couple of security tokens. MediaWiki was patched in order to use a crypto PRNG.

Sampling Bug with Strong Randomness

The next bug shows how even a strong crypto PRNG with sufficient entropy can produce a biased distribution. The chat program Cryptocat was designed to offer secure communication. It used a function that attempted to create a uniformly distributed string of decimal digits—namely, numbers in the range 0 through 9. However, just taking random bytes modulo 10 doesn’t yield a uniform distribution, because when taking all numbers between 0 and 255 and reducing them modulo 10, you don’t get an equal number of values in 0 to 9.

Cryptocat did the following to address that problem and obtain a uniform distribution:

Cryptocat.random = function() {

var x, o = '';

while (o.length < 16) {

x = state.getBytes(1);

if (x[0] <= 250) {

o += x[0] % 10;

}

}

return parseFloat('0.' + o)

}

And that was almost perfect. By taking only the numbers up to a multiple of 10 and discarding others, you’d expect a uniform distribution of the digits 0 through 9. Unfortunately, there was an off-by-one error in the if condition. I’ll leave the details to you as an exercise. You should find that the values generated had an entropy of 45 instead of approximately 53 bits (hint: <= should have been < instead).

Further Reading

I’ve just scratched the surface of randomness in cryptography in this chapter. There is much more to learn about the theory of randomness, including topics such as different entropy notions, randomness extractors, and even the power of randomization and derandomization in complexity theory. To learn more about PRNGs and their security, read the classic 1998 paper “Cryptanalytic Attacks on Pseudorandom Number Generators” by Kelsey, Schneier, Wagner, and Hall. Then look at the implementation of PRNGs in your favorite applications and try to find their weaknesses. (Search online for “random generator bug” to find plenty of examples.)

We’re not done with randomness, though. We’ll encounter it again and again throughout this book, and you’ll discover the many ways it helps to construct secure systems.