Chapter 11. Advanced Topics

In this chapter, we’ll do a quick pass through some of the more advanced topics. We’re going to assume that you have a pretty good hold on Docker by now and that you’ve already got it in production or you’re at least a regular user. We’ll talk about how containers work in detail, and about some aspects of Docker security, Docker networking, Docker plug-ins, swappable runtimes, and other advanced configuration.

Some of this chapter covers configurable changes you can make to your Docker installation. These can be useful, but Docker has good defaults, so as with most software, you should stick to the defaults on your operating system unless you have a good reason to change them and have educated yourself on what those changes mean to you. Getting your installation right for your environment will likely involve some trial and error, tuning, and adjustment over time. However, changing settings from their default before understanding them well is not what we recommend.

Containers in Detail

Though we usually talk about Linux containers as a single entity, they are, in fact, implemented through several separate mechanisms built into the Linux kernel that all work together: control groups (cgroups), namespaces, and SELinux or AppArmor, all of which serve to contain the process. cgroups provide for resource limits, namespaces allow for processes to use identically named resources and isolate them from each other’s view of the system, and SELinux or AppArmor provides strong security isolation. We’ll talk about SELinux and AppArmor in a bit. But what do cgroups and namespaces do for you?

Before we launch into detail, another comparison might be in order to help you understand how each of these subsystems plays into the way that containers work. At the risk of mixing metaphors, we might make a comparison to a hotel. When running Docker, your computer is the hotel. Without Docker, it’s more like a hostel with open bunk rooms. In our modern hotel, each container that you launch is an individual room with one or more guests (our processes) in it.

Namespaces make up the walls of the room, and ensure that processes cannot interact with neighboring processes in any ways that they are not specifically allowed to. Control groups are like the floor and ceiling of the room, trying to ensure that the inhabitants have the resources they need to enjoy their stay, without allowing them to use resources or space reserved for others. Imagine the worst kind of noisy hotel neighbors and you can really appreciate good, solid barriers between rooms. Finally, SELinux and AppArmor are a bit like hotel security, ensuring that even if something unexpected or untoward happens, it is unlikely to cause much more than the headache of filling out paperwork and filing an incident report.

cgroups

Traditional distributed system design dictates running each intensive task on its own virtual server. So, for example, you don’t run your applications on the database server because they have competing resource demands and their resource usage could grow unbounded and begin to dominate the server, starving the database of performance.

On real hardware systems, this could be quite expensive and so solutions like virtual servers are very appealing, in part because you can share expensive hardware between competing applications, and the virtualization layer will handle your resource partitioning. But while it saves money, this is still a fairly expensive approach if you don’t need all the other separation provided by virtualization, because running multiple kernels introduces a reasonable overhead on the applications. Maintaining virtual machines is also not the cheapest solution. All the same, cloud computing has shown that it’s immensely powerful and, with the right tooling, incredibly effective.

But if the only kind of isolation you needed was resource partitioning, wouldn’t it be great if you could get that on the same kernel? For many years, you could assign a “niceness” value to a process and it would give the scheduler hints about how you wanted this process to be treated in relation to others. But it wasn’t possible to impose hard limits like those that you get with virtual machines. And niceness is not at all fine-grained: you can’t give something more I/O and less CPU than other processes. This fine-grained control, of course, is one of the promises of Docker and the mechanism that it uses to provide that is cgroups, which predate Docker and were invented to solve just that problem.

Control groups, or cgroups for short, allow you to set limits on resources for processes and their children. This is the mechanism that Docker uses to control limits on memory, swap, CPU, and storage and network I/O resources. cgroups are built into the Linux kernel and originally shipped back in 2007 in Linux 2.6.24. The official kernel documentation defines them as “a mechanism for aggregating/partitioning sets of tasks, and all their future children, into hierarchical groups with specialized behavior.” It’s important to note that this setting applies to a process and all of the children that descend from it. That’s exactly how containers are structured.

Every Docker container is assigned a cgroup that is unique to that container. All of the processes in the container will be in the same group. This means that it’s easy to control resources for each container as a whole without worrying about what might be running. If a container is redeployed with new processes added, you can have Docker assign the same policy and it will apply to all of them.

We talked previously about the cgroups hooks exposed by Docker via the Remote API. This allows you to control memory, swap, and disk usage. But there are lots of other things you can limit with cgroups, including the number of I/O operations per second (iops) a container can have, for example. You might find that in your environment you need to use some of these levers to keep your containers under control, and there are a few ways you can go about doing that. By their nature, cgroups need to do a lot of accounting of resources used by each group. That means that when you’re using them, the kernel has a lot of interesting statistics about how much CPU, RAM, disk I/O, and so on your processes are using. So Docker uses cgroups not just to limit resources but also to report on them. These are many of the metrics you see, for example, in the output of docker stats.

The /sys filesystem

The primary way to control cgroups in a fine-grained manner, even if you configured them with Docker, is to manage them yourself. This is the most powerful method because changes don’t just happen at creation time—they can be done on the fly.

On systems with systemd, there are command-line tools like systemctl that you can use to do this. But since cgroups are built into the kernel, the method that works everywhere is to talk to the kernel directly via the /sys filesystem. If you’re not familiar with /sys, it’s a filesystem that directly exposes a number of kernel settings and outputs. You can use it with simple command-line tools to tell the kernel how to behave in a number of ways.

Note that this method of configuring cgroups controls for containers works only directly on the Docker server, so it is not available remotely via any API. If you use this method, you’ll need to figure out how to script this for your own environment.

Warning

Changing cgroups values yourself, outside of any Docker configuration, breaks some of the repeatability of Docker deployment. Unless you tool changes into your deployment process, settings will revert to their defaults when containers are replaced. Some schedulers take care of this for you, so if you run one in production you might check the documentation to see how to best apply these changes repeatably.

Let’s use an example of changing the CPU cgroups settings for a container we already have running. First we need to get the long ID of the container, and then we need to find it in the /sys filesystem. Here’s what that looks like:

$ docker ps --no-trunc CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS NAMES dcbbaa763... 0415448f2cc2 "supervisord" 3 weeks ago Up 2 days romantic_morse

Here, we’ve had docker ps give us the long ID in the output, and the ID we want is dcbbaa763daff1dc0a91e7675d3c93895cb6a6d83371e25b7f0bd62803ed8e86. You can see why Docker normally truncates this. In the examples we’re going to truncate it, too, to make it at least a little readable and fit into the constraints of a standard page. But remember that you will need to use the long one!

Now that we have the ID, we can find our container’s cgroup in the /sys filesystem. /sys is laid out so that each type of setting is grouped into a module and that module is exposed at a different place in the /sys filesystem. So when we look at CPU settings, we won’t see blkio settings, for example. You might take a look around in the /sys to see what else is there. But for now we’re looking at the CPU controller, so let’s inspect what that gives us. You need root access on the system to do this because you’re manipulating kernel settings:

$ ls /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf cgroup.clone_children cpu.cfs_period_us cpu.rt_runtime_us notify_on_release cgroup.event_control cpu.cfs_quota_us cpu.shares tasks cgroup.procs cpu.rt_period_us cpu.stat

Note

The exact path here will change a bit depending on the Linux distribution your Docker server is running on and what the hash of your container is. For example, on CoreOS, the path would look something like:

/sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/system.slice/docker-8122be2d7a67a52e949582f6d5 cb2771a8469ab20ecf7b6915e9217d92ddde98.scope/

You can see that under cgroups, there is a docker directory that contains all of the Docker containers that are running on this host. You can’t set cgroups for things that aren’t running, because they apply only to running processes. This is an important point that you should consider. Docker takes care of reapplying cgroup settings for you when you start and stop containers. Without that mechanism, you are somewhat on your own.

Back to our task. Let’s inspect the CPU shares for this container. Remember that we set these earlier via the Docker command-line tool. But for a normal container where no settings were passed, this setting is the default:

$ cat /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf/cpu.shares 1024

1024 CPU shares means we are not limited at all. Let’s tell the kernel that this container should be limited to half that:

$ echo 512 > /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf/cpu.shares $ cat /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf/cpu.shares 512

Warning

In production you should not use this method to adjust cgroups on the fly, but we are demonstrating it here so that you understand the underlying mechanics that make all of this work. Take a look at docker container update if you’d like to adjust these on a running container. You might also find the --cgroup-parent option to docker run interesting.

There you have it. We’ve changed the container’s settings on the fly. This method is very powerful because it allows you to set any cgroups setting for the container. But as we mentioned earlier, it’s entirely ephemeral. When the container is stopped and restarted, the setting reverts to the default:

$ docker stop dcbbaa763daf dcbbaa763daf $ cat /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf/cpu.shares cat: /sys/fs/.../cpu.shares: No such file or directory

You can see that the directory path doesn’t even exist anymore now that the container is stopped. And when we start it back up, the directory comes back but the setting is back to 1024:

$ docker start dcbbaa763daf dcbbaa763daf $ cat /sys/fs/cgroup/cpu/docker/dcbbaa763daf/cpu.shares 1024

If you were to change these kinds of settings in a production system via the /sys fileystem directly, you’d want to tool that directly. A daemon that watches the docker events stream and changes settings at container startup, for example, is a possibility. Currently, the community has not contributed much rich tooling in this area. It’s likely that Docker will eventually expand the native driver’s functionality to allow this level of configuration.

Namespaces

Inside each container, you see a filesystem, network interfaces, disks, and other resources that all appear to be unique to the container despite sharing the kernel with all the other processes on the system. The primary network interface on the actual machine, for example, is a single shared resource. But inside your container it will look like it has an entire network interface to itself. This is a really useful abstraction: it’s what makes your container feel like a machine all by itself. The way this is implemented in the kernel is with namespaces. Namespaces take a traditionally global resource and present the container with its own unique and unshared version of that resource.

Note

Unlike cgroups, namespaces are not something that you can see reflected in the kernel filesystems, like /sys and /proc.

Rather than just having a single namespace, however, containers have a namespace on each of the six types of resources that are currently namespaced in the kernel: mounts, UTS, IPC, PID, network, and user namespaces. Essentially when you talk about a container, you’re talking about a number of different namespaces that Docker sets up on your behalf. So what do they all do?

- Mount namespaces

-

Docker uses these primarily to make your container look like it has its own entire filesystem namespace. If you’ve ever used a

chrootjail, this is its tougher cousin. It looks a lot like achrootjail but goes all the way down to the kernel so that evenmountandunmountsystem calls are namespaced. If you usedocker execornsenterto get into a container, you’ll see a filesystem rooted on “/”. But we know that this isn’t the actual root partition of the system. It’s the mount namespace that makes that possible. - UTS namespaces

-

Named for the kernel structure they namespace, UTS (Unix Timesharing System) namespaces give your container its own hostname and domain name. This is also used by older systems like NIS to identify which domain a host belongs to. When you enter a container and see a hostname that is not the same as the machine on which it runs, it’s this namespace that makes that happen.

Tip

To have a container use its host’s UTS namespace, you can specify the --uts=host option when launching the container with docker run. There are similar commands for sharing the other namespaces as well.

- IPC namespaces

-

These isolate your container’s System V IPC and POSIX message queue systems from those of the host. Some IPC mechanisms use filesystem resources like named pipes, and those are covered by the mount namespace. The IPC namespace covers things like shared memory and semaphores that aren’t filesystem resources but which really should not cross the container wall.

- PID namespaces

-

We have already shown that you can see all of the processes in containers in the Linux

psoutput on the host Docker server. But inside the container, processes have a totally different PID. This is the PID namespace in action. A process has a unique PID in each namespace to which it belongs. If you look in /proc inside a container, or runps, you will only see the processes inside the container’s PID namespace. - Network namespaces

-

This is what allows your container to have its own network devices, ports, and so on. When you run

docker psand see the bound ports for your container, you are seeing ports from both namespaces. Inside the container, yournginxmight be bound to port 80, but that’s on the namespaced network interface. This namespace makes it possible to have what seems to be a completely separate network stack for your container. - User namespaces

-

These provide isolation between the user and group IDs inside a container and those on the Docker host. Earlier when we looked at

psoutput outside and then inside the container, we saw different user IDs; this is how that happened. A new user inside a container is not a new user on the Docker host’s main namespace, and vice versa. There are some subtleties here, though. For example, UID 0 (root) in a user namespace is not the same thing as UID 0 on the host, although running asrootinside the container does increase the risk of potential security exploits. Some of this work is reasonably new to the Linux kernel and there are concerns about security leakage, which we’ll talk about in a bit.

So all of the namespaces combined together provide the visual and, in many cases, the functional isolation that makes a container look like a virtual machine even though it’s on the same kernel. Let’s explore what some of that namespacing that we just described actually looks like.

Note

There is a lot of work going into making containers more secure. The community is actively looking into ways to support rootless containers that would enable regular users to create, run, and manage containers locally without needing special privileges. New container runtimes like Google gVisor are also trying to explore better ways to create much more secure container sandboxes without losing most of the advantages of containerized workflows.

Exploring namespaces

One of the easiest to demonstrate namespaces is the UTS namespace, so let’s use docker exec to get a shell in a container and take a look. From within the Docker server, run the following:

$ hostname docker2 $ docker exec -i -t 28970c706db0 /bin/bash -l # hostname 28970c706db0

Note

Although docker exec will work from a remote system, here we ssh into the Docker server itself in order to demonstrate that the hostname of the server is different from inside the container. There are also easier ways to obtain some of the information we’re getting here. But the idea is to explore how namespaces work, not to pick the most ideal path to gather the information.

That docker exec command line gets us an interactive process (-i), allocates a pseudo-TTY (-t), and then executes /bin/bash while executing all the normal login process in the bash shell (-l). Once we have a terminal open inside the container’s namespace, we ask for the hostname and get back the container ID. That’s the default hostname for a Docker container unless you tell Docker to name it otherwise. This is a pretty simple example, but it should clearly show that we’re not in the same namespace as the host.

Another example that’s easy to understand and demonstrate involves PID namespaces. Let’s log into the Docker server again and look at the process list of a new container:

$ docker run -d --rm --name pstest spkane/train-os sleep 240 6e005f895e259ed03c4386b5aeb03e0a50368cc173078007b6d1beaa8cd7dded $ docker exec -ti pstest /bin/bash -l [root@6e005f895e25 /]# ps -ef UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD root 1 0 0 16:35 ? 00:00:00 sleep 240 root 7 0 0 16:36 pts/0 00:00:00 /bin/bash -l root 27 7 0 16:36 pts/0 00:00:00 ps -ef [root@6e005f895e25 /]# exit logout

and then let’s get the same list from the Docker server:

$ ps axlf ... 899 root 3:29 /usr/bin/containerd 1088 root 7:12 /usr/local/bin/dockerd -H unix:///var/run/docker.sock ... 1158 root 4:59 docker-containerd --config ... 4946 root 0:00 docker-containerd-shim -namespace moby -workdir ... 4966 root 0:00 sleep 240 ... $ pstree -p 1088 dockerd(1088)---docker-containe(1158)-+-docker-containe(4946)---sleep(4966)

What we can see here is that from inside our container, the original command run by Docker from the CMD in our Dockerfile is sleep 240 and it has been assigned PID 1 inside the container. You might recall that this is the PID normally used by the init process on Unix systems. In this case, the sleep 240 command that we started the container with is the first process, so it gets PID 1. But in the Docker server’s main namespace, we do a little work to find our container’s processes and we see the PID there is not 1, but 4966, and it’s a child of the dockerd process, which is PID 1088.

We can go ahead and remove the container we started in the last example, by running:

$ docker rm -f pstest

The other namespaces work in essentially the same manner, and you probably get the idea by now. It’s worth pointing out here that when we were working with nsenter back in Chapter 4, we had to pass a pretty arcane (at that point) set of arguments to the command when we ran it to enter a container from the Docker server. Let’s look at that command

line now:

$ sudo nsenter --target $PID --mount --uts --ipc --net --pid root@3c4f916619a5:/#

Now that we’ve explained namespaces in detail, this probably makes a lot more sense to you. You’re telling nsenter exactly which of the namespaces you want to enter. It can also be educational to use nsenter to only enter parts of the namespace of a throwaway container to see what you get. In the preceding example, we enter all of the namespaces we just talked about.

When it comes down to it, namespaces are the primary thing that make a container look like a container. Combine them with cgroups, and you have reasonably robust isolation between processes on the same kernel.

Security

We’ve spent a good bit of space now talking about how Docker contains applications, allows you to constrain resources, and uses namespaces to give the container its own unique view of the world. We have also briefly mentioned the need for technologies like SELinux and AppArmor. One of the advantages of containers is the ability to replace virtual machines in a number of cases. So let’s take a look at what isolation we really get, and what we don’t.

You are undoubtedly aware by now that the isolation you get from a container is not as strong as that from a virtual machine. We’ve been reinforcing the idea from the start of this book that containers are just processes running on the Docker server. Despite the isolation provided by namespaces, containers are not as secure as you might imagine, especially if you are still mentally comparing them to lightweight virtual machines.

One of the big boosts in performance for containers, and one of the things that makes them lightweight, is that they share the kernel of the Docker server. This is also the source of the greatest security concern around Docker containers. The main reason for this concern is that not everything in the kernel is namespaced. We have talked about all of the namespaces that exist and how the container’s view of the world is constrained by the namespaces it runs in. However, there are still lots of places in the kernel where no real isolation exists and namespaces constrain the container only if it does not have the power to tell the kernel to give it access to a different namespace.

Containerized applications are more secure than noncontainerized applications because cgroups and standard namespaces provide some important isolation from the host’s core resources. But you should not think of containers as a substitute for good security practices. If you think about how you would run an application on a production system, that is really how you should run all your containers. If your application would traditionally run as a nonprivileged user on a server, then it should be run in the same manner inside the container. It is very easy to tell Docker to run your whole container as a nonprivileged user, and in almost all cases, this is what you should be doing.

Tip

The --userns-remap argument to the dockerd command makes it possible to force all containers to run within a user and group context that is unprivileged on the host system. This protects the host from various potential security exploits. For more information about this topic, read through the official userns-remap and docker daemon documentation.

Let’s look at some common security risks and controls.

UID 0

The first and most overarching security risk in a container is that, unless you are using the userns-remap functionality in the Docker daemon, the root user in the container is actually the root user on the system. There are extra constraints on root in a container, and namespaces do a good job of isolating root in the container from the most dangerous parts of the /proc and /sys filesystems. But generally speaking, by default, you have root access, so if you somehow get access to protected resources on a file mount or outside of your namespace, then the kernel will treat you as root, and therefore give you access to the resource. Unless otherwise configured, Docker starts all services in containers as root, which means you are responsible for managing privileges in your applications just like you are on any Linux system. Let’s explore some of the limits on root access and look at some obvious holes. This is not intended to be an exhaustive statement on container security, but rather an attempt to give you a healthy understanding of some of the classes of security risks.

First, let’s fire up a container and get a bash shell using the public Ubuntu image shown in the following code. Then we’ll see what kinds of access we have, after installing some tools we want to run.

$ docker run -t -i ubuntu /bin/bash root@808a2b8426d1:/# apt-get update ... root@808a2b8426d1:/# apt-get install kmod ... root@808a2b8426d1:/# lsmod Module Size Used by xt_nat 12726 2 xt_tcpudp 12603 8 veth 13244 0 xt_addrtype 12713 2 xt_conntrack 12760 1 iptable_filter 12810 1 acpiphp 24119 0 ipt_MASQUERADE 12759 4 aufs 191008 14 iptable_nat 12909 1 nf_conntrack_ipv4 14538 2 nf_defrag_ipv4 12729 1 nf_conntrack_ipv4 nf_nat_ipv4 13316 1 iptable_nat nf_nat 26158 4 ipt_MASQUERADE,nf_nat_ipv4 nf_conntrack 83996 6 ipt_MASQUERADE,nf_nat ip_tables 27473 2 iptable_filter,iptable_nat x_tables 29938 7 ip_tables,xt_tcpudp bridge 101039 0 floppy 70206 0 ...

In Docker Community Edition you may see only two modules in the list, but on a normal Linux system this list can be very long, so we’ve cut the output down quite a bit in this example. What we’re looking at here is a new container that we started. Using lsmod, we’ve just asked the kernel to tell us what modules are loaded. It is not that surprising that we get this list, since a normal user can always do this. If you run this listing on the Docker server itself, it will be identical, which reinforces the fact that the container is talking to the same Linux kernel that is running on the server. So we can see the kernel modules; what happens if we try to unload the floppy module?

root@808a2b8426d1:/# rmmod floppy rmmod: ERROR: ... kmod_module_remove_module() could not remove 'floppy': ... rmmod: ERROR: could not remove module floppy: Operation not permitted

That’s the same error message we would get if we were a nonprivileged user trying to tell the kernel to remove a module. This should give you a good sense that the kernel is doing its best to prevent us from doing things we shouldn’t. And because we’re in a limited namespace, we can’t get the kernel to give us access to the top-level namespace either. We are essentially relying on the hope that there are no bugs in the kernel that allow us to escalate our privileges inside the container. Because if we do manage to do that, we are root, which means that we will be able to make changes, if the kernel allows us to.

We can contrive a simple example of how things can go wrong by starting a bash shell in a container that has had the Docker server’s /etc bind-mounted into the container’s namespace. Keep in mind that anyone who can start a container on your Docker server can do what we’re about to do any time they like because you can’t configure Docker to prevent it, so you must instead rely on external tools like SELinux to avoid exploits like this:

$ docker run -i -t -v /etc:/host_etc ubuntu /bin/bash root@e674eb96bb74:/# more /host_etc/shadow root:!:16230:0:99999:7::: daemon:*:16230:0:99999:7::: bin:*:16230:0:99999:7::: sys:*:16230:0:99999:7::: ... irc:*:16230:0:99999:7::: nobody:*:16230:0:99999:7::: libuuid:!:16230:0:99999:7::: syslog:*:16230:0:99999:7::: messagebus:*:16230:0:99999:7::: kmatthias:$1$aTAYQT.j$3xamPL3dHGow4ITBdRh1:16230:0:99999:7::: sshd:*:16230:0:99999:7::: lxc-dnsmasq:!:16458:0:99999:7:::

Here we’ve used the -v switch to Docker to tell it to mount a host path into the container. The one we’ve chosen is /etc, which is a dangerous thing to do. But it serves to prove a point: we are root in the container, and root has file permissions in this path. So we can look at the real /etc/shadow file any time we like. There are plenty of other things you could do here, but the point is that by default you’re only partly constrained.

Warning

It is a bad idea to run your container processes with UID 0. This is because any exploit that allows the process to somehow escape its namespaces will expose your host system to a fully privileged process. You should always run your standard containers with a nonprivileged UID. This is not a theoretical problem: it has been demonstrated publicly with several exploits.

The easiest way to deal with the potential problems surrounding the use of UID 0 inside containers is to always tell Docker to use a different UID for your container.

You can do this by passing the -u argument to docker run. In the next example we run the whoami command to show that we are root by default and that we can read the /etc/shadow file that is inside this container.

$ docker run spkane/train-os:latest whoami root $ docker run spkane/train-os:latest cat /etc/shadow root:locked::0:99999:7::: bin:*:16489:0:99999:7::: daemon:*:16489:0:99999:7::: adm:*:16489:0:99999:7::: lp:*:16489:0:99999:7::: ...

In this example, when you add -u 500, you will see that we become a new, unprivileged user and can no longer read the same /etc/shadow file.

$ docker run -u 500 spkane/train-os:latest whoami user500 $ docker run -u 500 spkane/train-os:latest cat /etc/shadow cat: /etc/shadow: Permission denied

Privileged Containers

There are times when you need your container to have special kernel capabilities that would normally be denied to the container. These could include mounting a USB drive, modifying the network configuration, or creating a new Unix device.

In the following code, we try to change the MAC address of our container:

$ docker run --rm -ti ubuntu /bin/bash

root@b328e3449da8:/# ip link ls

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

9: eth0: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/ether 02:42:0a:00:00:04 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

root@b328e3449da8:/# ip link set eth0 address 02:0a:03:0b:04:0c

RTNETLINK answers: Operation not permitted

root@b328e3449da8:/# exit

As you can see, it doesn’t work. This is because the underlying Linux kernel blocks the nonprivileged container from doing this, which is exactly what we’d normally want. However, assuming that we need this functionality for our container to work as intended, the easiest way to significantly expand a container’s privileges is by launching it with the --privileged=true argument.

Warning

We don’t recommend actually running the ip link set eth0 address command in the next example, since this will change the MAC address on the container’s network interface. We show it to help you understand the mechanism. Try it at your own risk.

$ docker run -ti --rm --privileged=true ubuntu /bin/bash

root@88d9d17dc13c:/# ip link ls

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

9: eth0: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/ether 02:42:0a:00:00:04 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

root@88d9d17dc13c:/# ip link set eth0 address 02:0a:03:0b:04:0c

root@88d9d17dc13c:/# ip link ls

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

9: eth0: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/ether 02:0a:03:0b:04:0c brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

root@88d9d17dc13c:/# exit

In the preceding output, you will notice that we no longer get the error and the link/ether entry for eth0 has been changed.

The problem with using the --privileged=true argument is that you are giving your container very broad privileges, and in most cases you likely need only one or two kernel capabilities to get the job done.

If we explore our privileged container some more, we will discover that we have capabilities that have nothing to do with changing the MAC address. We can even do things that could cause issues with both Docker and the host system. In the following code, we are going to create a memory swapfile and enable it:1

$ docker run -ti --rm --privileged=true ubuntu /bin/bash root@0ffcdd8f7535:/# dd if=/dev/zero of=/swapfile1 bs=1024 count=100 100+0 records in 100+0 records out 102400 bytes (102 kB) copied, 0.00046004 s, 223 MB/s root@0ffcdd8f7535:/# mkswap /swapfile1 Setting up swapspace version 1, size = 96 KiB no label, UUID=fc3d6118-83df-436e-867f-87e9fbce7692 root@0ffcdd8f7535:/# swapon /swapfile1 root@0ffcdd8f7535:/# swapoff /swapfile1 root@0ffcdd8f7535:/# exit exit

Warning

In the previous example, if you do not disable the swapfile before exiting your container, you will leave your Docker host in a bad state where Docker can’t destroy the container because your host is accessing a swapfile that is inside the container’s filesystem.

In that case, the error message will look something like this:

FATAL [0049] Error response from daemon: Cannot destroy container 0f...70: Driver overlay failed to remove root filesystem 0f...70: remove /var/lib/docker/overlay/0f...70/upper/swapfile1: operation not permitted

In this example, you can fix this from the Docker server by running:

$ sudo swapoff \

/var/lib/docker/overlay/0f...70/upper/swapfile1

So, as we’ve seen, it is possible for people to do malicious things in a fully privileged container.

To change the MAC address, the only kernel capability we actually need is CAP_NET_ADMIN. Instead of giving our container the full set of privileges, we can give it this one privilege by launching our Docker container with the --cap-add argument, as shown here:

$ docker run -ti --rm --cap-add=NET_ADMIN ubuntu /bin/bash

root@852d18f5c38d:/# ip link set eth0 address 02:0a:03:0b:04:0c

root@852d18f5c38d:/# ip link ls

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

9: eth0: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state ...

link/ether 02:0a:03:0b:04:0c brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

root@852d18f5c38d:/# exit

You should also notice that although we can change the MAC address, we can no longer use the swapon command inside our container.

$ docker run -ti --rm --cap-add=NET_ADMIN ubuntu /bin/bash root@848aa7924594:/# dd if=/dev/zero of=/swapfile1 bs=1024 count=100 100+0 records in 100+0 records out 102400 bytes (102 kB) copied, 0.000575541 s, 178 MB/s root@848aa7924594:/# mkswap /swapfile1 Setting up swapspace version 1, size = 96 KiB no label, UUID=3b365d90-8116-46ad-80c5-24341299dc41 root@848aa7924594:/# swapon /swapfile1 swapon: /swapfile1: swapon failed: Operation not permitted root@848aa7924594:/# exit

It is also possible to remove specific capabilities from a container. I imagine for a moment that your security team requires that tcpdump be disabled in all containers, and when you test some of your containers, you find that tcpdump is installed and can easily be run.

$ docker run -ti --rm spkane/train-os:latest tcpdump -i eth0 tcpdump: verbose output suppressed, use -v or -vv for full protocol decode listening on eth0, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), capture size 262144 bytes 26:52:10.182287 IP6 :: > ff03::1:ff3e:f0e4: ICMP6, neighbor solicitation, ... 26:52:10.199257 ARP, Request who-has 1.qarestr.sub-172-14-0.myvzw.com ... 26:52:10.199312 ARP, Reply 1.qarestr.sub-172-14-0.myvzw.com is-at ... 26:52:10.199328 IP 204117a59e09.38725 > 192.168.62.4.domain: 52244+ PTR? ... 26:52:11.223184 IP6 fe83::8c11:30ff:fe5e:f0e4 > ff02::16: HBH ICMP6, ... ...

You could remove tcpdump from your images, but there is very little preventing someone from reinstalling it. The most effective way to solve this problem is to determine what capability tcpdump needs to operate and remove that from the container. In this case, you can do so by adding --cap-drop=NET_RAW to your docker run command.

$ docker run -ti --rm --cap-drop=NET_RAW spkane/train-os:latest tcpdump -i eth0 tcpdump: eth0: You don't have permission to capture on that device (socket: Operation not permitted)

By using both the --cap-add and --cap-drop arguments to docker run, you can finely control your container’s

Linux kernel capabilities.

Secure Computing Mode

When Linux kernel version 2.6.12 was released in 2005, it included a new security feature called Secure Computing Mode, or seccomp for short. This feature enables a process to make a one-way transition into a special state, where it will only be allowed to make the system calls exit(), sigreturn(), and read() or write() to already-open file descriptors.

An extension to seccomp, called seccomp-bpf, utilizes the Linux version of Berkeley Packet Filter (bpf) rules to allow you to create a policy that will provide an explicit list of system calls that a process can utilize while running under Secure Computing Mode. The Docker support for Secure Computing Mode utilizes seccomp-bpf so that users can create profiles that give them very fine-grained control of what kernel system calls their containerized processes are allowed to make.

Note

By default, all containers use Secure Computing Mode and have the default profile attached to them. You can read more about Secure Computing Mode and what system calls the default profile blocks in the documentation. You can examine the default policy’s JSON file to see what a policy looks like and understand exactly what it defines.

To see how you could use this, let’s use the program strace to trace the system calls that a process is making.

If you try to run strace inside a container for debugging, you’ll quickly realize that it will not work when using the default seccomp profile.

$ docker run -ti --rm spkane/train-os:latest whoami root $ docker run -ti --rm spkane/train-os:latest strace whoami strace: ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, ...): Operation not permitted +++ exited with 1 +++

You could potentially fix this by giving your container the process-tracing-related capabilities, like this:

$ docker run -ti --rm --cap-add=SYS_PTRACE spkane/train-os:latest \

strace whoami

execve("/usr/bin/whoami", ["whoami"], [/* 4 vars */]) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x136f000

mmap(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, ...

access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file ...

open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

...

write(1, "root\n", 5root

) = 5

close(1) = 0

munmap(0x7f854286b000, 4096) = 0

close(2) = 0

exit_group(0) = ?

+++ exited with 0 +++

But you can also solve this problem by using a seccomp profile. Unlike seccomp, --cap-add will enable a whole set of system calls, and you may not need them all. With a seccomp profile, however, you can be very specific about exactly what you want enabled or disabled.

If we take a look at the default seccomp profile, we’ll see something like this:

{"defaultAction":"SCMP_ACT_ERRNO","archMap":[{"architecture":"SCMP_ARCH_X86_64","subArchitectures":["SCMP_ARCH_X86","SCMP_ARCH_X32"]},...],"syscalls":[{"names":["accept","accept4",..."write","writev"],"action":"SCMP_ACT_ALLOW","args":[],"comment":"","includes":{},"excludes":{}},{"names":["personality"],"action":"SCMP_ACT_ALLOW","args":[{"index":0,"value":0,"valueTwo":0,"op":"SCMP_CMP_EQ"}],"comment":"","includes":{},"excludes":{}},...{"names":["vhangup"],"action":"SCMP_ACT_ALLOW","args":[],"comment":"","includes":{"caps":["CAP_SYS_TTY_CONFIG"]},"excludes":{}}]}

This JSON file provides a list of supported architectures, a default rule, and a specific setting for each system call that doesn’t fall under the default rule. In this case, the default action is SCMP_ACT_ERRNO, and will generate an error if an unspecified call is attempted.

If you look closely at the default profile, you’ll notice that CAP_SYS_PTRACE includes four system calls: kcmp, process_vm_readv, process_vm_writev, and ptrace.

{"names":["kcmp","process_vm_readv","process_vm_writev","ptrace"],"action":"SCMP_ACT_ALLOW","args":[],"comment":"","includes":{"caps":["CAP_SYS_PTRACE"]},

In the current use case, the container actually needs only one of those syscalls to function properly. This means that you are giving your container more capabilities than it requires when you use --cap-add=SYS_PTRACE. To ensure that you are adding only the one additional system call that you need, you can create your own Secure Computing Mode policy, based on the default policy that Docker provides.

First, pull down the default policy and make a copy of it.

$ wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/moby/moby/master/\ profiles/seccomp/default.json $ cp default.json strace.json

Note

The URL above has been continued on the following line so that it fits in the margins. You may find that you need to re-assemble the URL and remove the back slashes for the command to work properly in your environment.

Then edit the file and insert the line containing the word ptrace into the syscalls.names section of JSON:

..."syscalls":[{"names":[..."pwritev2","ptrace","read",...

Once you have saved your changes, you can verify them using a command like diff (Unix) or compare-object (PowerShell).

$ diff -u default.json strace.json

--- default.json 2018-02-19 11:47:07.000000000 -0800+++ strace.json 2018-02-19 12:12:21.000000000 -0800@@ -229,6 +229,7 @@"pwrite64", "pwritev", "pwritev2",+ "ptrace","read", "readahead", "readlink",

You are now ready to test your new finely tuned seccomp profile.

$ docker run -ti --rm --security-opt=seccomp:strace.json \

spkane/train-os:latest strace whoami

execve("/usr/bin/whoami", ["whoami"], [/* 4 vars */]) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x944000

...

close(2) = 0

exit_group(0) = ?

+++ exited with 0 +++

If everything went according to plan, your strace of the whoami program should have run perfectly, and now you can rest comfortably knowing that your container has been given only the exact privileges it needs to get the job done, and nothing more.

Warning

You could completely disable the default Secure Computing Mode profile by setting --securityopt=seccomp:unconfined, however running a container unconfined is a very bad idea in general, and is probably only useful when you are trying to figure out exactly what system calls you need to define in your profile.

The strength of Secure Computing Mode is that it allows users to be much more selective about what a container can and can’t do with the underlying Linux kernel. Custom profiles are not required for most containers, but they are an incredibly handy tool when you need to carefully craft a powerful container and ensure that you maintain the overall security of the system.

SElinux and AppArmor

Earlier we talked about how containers are a combination of two or three things: cgroups, namespaces, and SELinux or AppArmor. We’re going to discuss the latter two systems now. They allow you to apply security controls that extend beyond those normally supported by Unix systems. SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) originated in the US National Security Agency, was strongly adopted by Red Hat, and supports very fine-grained control. AppArmor is an effort to achieve many of the same goals without the level of complication involved in SELinux. AppArmor actually predates the open source release of SELinux by two years, having first appeared in 1998 in the Immunix Linux distribution. Novell, SuSE, and Canonical have been some of AppArmor’s recent champions.

Docker ships by default with reasonable profiles enabled on platforms that support them. This means that on Ubuntu systems, AppArmor is enabled and configured, and on Red Hat systems, SELinux is set up. You can further configure these profiles to enable or prevent all sorts of features, and if you’re running Docker in production, you should do a risk analysis to determine if there are additional considerations that you should be aware of. We’ll give a quick outline of the benefits you are getting from these systems.

Both systems provide Mandatory Access Control, a class of security system where a systemwide security policy grants users (or “initiators”) access to a resource (or “target”). This allows you to prevent anyone, including root, from accessing a part of the system that they should not have access to. You can apply the policy to a whole container so that all processes are constrained. Many chapters would be required to provide a clear and detailed overview of how to configure these systems. The default profiles are performing tasks like blocking access to parts of the /proc and /sys filesystems that would be dangerous to expose in the container, even though they show up in the container’s namespace. The default profiles also provide more narrowly scoped mount access to prevent containers from getting hold of mount points they should not see.

If you are considering using Docker containers in production, make certain that the systems you are running have AppArmor or SELinux enabled and running. For the most part, both systems are reasonably equivalent. But in the Docker context, one notable limitation of SELinux is that it only works fully on systems that support filesystem metadata, which means that it won’t work with all Docker storage drivers. AppArmor, on the other hand, does not use filesystem metadata and therefore works on all of the Docker backends. Which one you use is somewhat distribution-centric, so you may be forced to choose a filesystem backend that also supports the security system that you use.

The Docker Daemon

From a security standpoint, the Docker daemon and its components are the only completely new risk you are introducing to your infrastructure. Your containerized applications are not any less secure and are, at least, a little more secure than they would be if deployed outside of containers. But without the containers, you would not be running dockerd, the Docker daemon. You can run Docker such that it doesn’t expose any ports on the network. In this model, you’d need to do something like set up an SSH tunnel to each Docker server or run a specialized agent if you wanted to control the containers. That’s often not ideal, so many people end up exposing at least one Docker port on the local network.

The default configuration for Docker, on most distributions, leaves Docker isolated from the network with only a local Unix socket exposed. Since you cannot remotely administer Docker when it is set up this way, it is not uncommon to see people simply add the nonencrypted port 2375 to the configuration. This may be great for getting started with Docker, but it is not what you should do in any environment where you care about the security of your servers. In fact, you should not open Docker up to the outside world at all unless you have a very good reason to do it. If you do, you should also commit to properly securing it. Most scheduler systems run their own software on each node and expect to talk to Docker over the Unix domain socket.

If you do need to expose the daemon to the network, you can do a few things to tighten Docker down in a way that makes sense in most production environments. But no matter what you do, you are relying on the Docker daemon itself to be resilient against threats like buffer overflows and race conditions, two of the more common classes of security vulnerabilities. This is true of any network service. The risk is perhaps a little higher from Docker because it has the ability to control most of your applications, and because of the privileges the daemon requires, it has to be run as root.

The basics of locking Docker down are common with many other network daemons: encrypt your traffic and authenticate users. The first is reasonably easy to set up on Docker; the second is not as easy. If you have SSL certificates you can use for protecting HTTP traffic to your hosts, such as a wildcard certificate for your domain, you can turn on TLS support to encrypt all of the traffic to your Docker servers, using port 2376. This is a good first step. The Docker documentation will walk you through doing this.

Authenticating users is more complicated. Docker does not provide any kind of fine-grained authorization: you either have access or you don’t. But the authentication control it does provide—signed certificates—is reasonably strong. Unfortunately this also means that you don’t get a cheap step from no authentication to some authentication without also having to set up your own certificate authority in most cases. If your organization already has one, then you are in luck. Certificate management needs to be implemented carefully in any organization, both to keep certificates secure and to distribute them efficiently. So, given that, here are the basic steps:

-

Set up a method of generating and signing certificates.

-

Generate certificates for the server and clients.

-

Configure Docker to require certificates with

--tlsverify.

Detailed instructions on getting a server and client set up, as well as a simple certificate authority, are included in the Docker documentation.

Warning

Because it’s a daemon that runs with privilege, and because it has direct control of your applications, it is a bad idea to expose Docker directly on the internet. If you need to talk to your Docker hosts from outside your network, consider something like a VPN or an SSH tunnel to a secure jump host.

Advanced Configuration

Docker has a very clean external interface and on the surface it looks pretty monolithic. But there’s actually a lot going on under the covers that is configurable, and the logging backends we described in “Logging” are a good example. You can also do things like change out the storage backend for container images for the whole daemon, use a completely different runtime, or configure individual containers to run on a totally different network configuration. Those are powerful switches and you’ll want to know what they do before turning them on. First we’ll talk about the network configuration, then we’ll cover the storage backends, and finally we’ll try out a completely different container runtime to replace the default runc supplied with Docker.

Networking

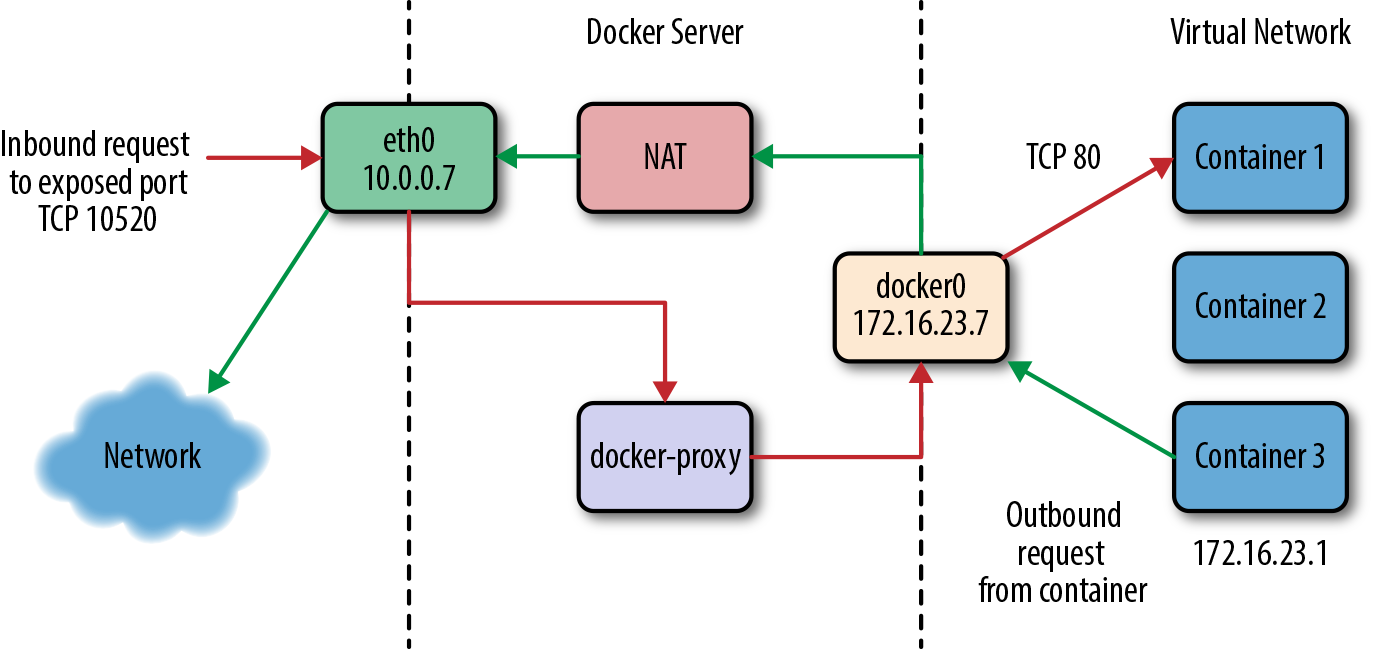

Early on we described the layers of networking between a Docker container and the real live network. Let’s take a closer look at how that works. Docker supports a rich set of network configurations, but let’s start out with the default setup. Figure 11-1 shows a drawing of a typical Docker server, where there are three containers running on their private network, shown on the right. One of them has a public port (TCP port 10520) that is exposed on the Docker server. We’ll track how an inbound request gets to the Docker container and also how a Docker container can make an outbound connection to the external network.

Figure 11-1. The network on a typical Docker server

If we have a client somewhere on the network that wants to talk to the nginx server running on TCP port 80 inside Container 1, the request will come into the eth0 interface on the Docker server. Because Docker knows this is a public port, it has spun up an instance of docker-proxy to listen on port 10520. So our request is passed to the docker-proxy process, which then forwards the request to the correct container address and port on the private network. Return traffic from the request flows through the same route.

Outbound traffic from the container follows a different route in which the docker-proxy is not involved at all. In this case, Container 3 wants to contact a server on the public internet. It has an address on the private network of 172.16.23.1 and its default route is the docker0 interface 172.16.23.7. So it sends the traffic there. The Docker server now sees that this traffic is outbound and it has traffic forwarding enabled. And since the virtual network is private, it wants to send the traffic from its own public address instead. So the request is passed through the kernel’s network address translation (NAT) layer and put onto the external network via the eth0 interface on the server. Return traffic passes through the same route. Note that the NAT is one-way, so containers on the virtual network will see real network addresses in response packets.

You’ve probably noticed that it’s not a simple configuration. It’s a fair amount of complexity, but it makes Docker seem pretty transparent. It also contributes to the security posture of the Docker stack because the containers are namespaced into their own network namespace, are on their own private network, and don’t have access to things like the main system’s DBus or IPTables.

Let’s examine what’s happening at a more detailed level. The interfaces that show up in ifconfig or ip addr show in the Docker container are actually virtual Ethernet interfaces on the Docker server’s kernel. They are then mapped into the container’s network namespace and given the names that you see inside the container. Let’s take a look at what we see when running ip addr show on a Docker server. We’ll shorten the output a little for clarity and spaces, as shown here:

$ ip addr show

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether 00:0c:29:b2:2a:21 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.16.168.178/24 brd 172.16.168.255 scope global eth0

inet6 fe80::20c:29ff:feb2:2a21/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

4: docker0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether 56:84:7a:fe:97:99 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.17.42.1/16 scope global docker0

inet6 fe80::5484:7aff:fefe:9799/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

112: vethf3e8733: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether b6:3e:7a:ba:5e:1c brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet6 fe80::b43e:7aff:feba:5e1c/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

What this tells us is that we have the normal loopback interface, our real Ethernet interface eth0, and then the Docker bridge interface, docker0, that we described earlier. This is where all the traffic from the Docker containers is picked up to be routed outside the virtual network. The surprising thing in this output is the vethf3e8733 interface. When Docker creates a container, it creates two virtual interfaces, one of which sits on the server side and is attached to the docker0 bridge, and one that is exposed into the container’s namespace. What we’re seeing here is the server-side interface. Did you notice how it doesn’t show up as having an IP address assigned to it? That’s because this interface is just joined to the bridge. This interface will have a totally different name in the container’s namespace as well.

As with so many pieces of Docker, you can replace the proxy with a different implementation. To do so, you would use the --userland-proxy-path=<path> setting, but there are probably not that many good reasons to do this unless you have a very specialized network. However, the --userland-proxy=false flag to dockerd will completely disable the userland-proxy and instead rely on hairpin NAT functionality to route traffic between local containers. This performs a lot better than the userland-proxy and will likely become the preferred approach. Docker documentation currently recommends it as the best approach, but it is not yet the default. If you need higher-throughput services, this might be right for you.

Host networking

As we’ve noted, there is a lot of complexity involved in the default implementation. You can, however, run a container without the whole networking configuration that Docker puts in place for you. And the docker-proxy can also limit throughput for very high-volume data services, by requiring all the network traffic to pass through the docker-proxy process before being received by the container. So what does it look like if we turn off the Docker network layer? Since the beginning, Docker has let you do this on a per-container basis with the --net=host command-line switch. There are times, like when you want to run high-throughput applications, where you might want to do this. But you lose some of Docker’s flexibility when you do it. Even if you never need or want to do this, it’s useful to expose how the mechanism works.

Warning

Like others we discuss in this chapter, this is not a setting you should take lightly. It has operational and security implications that might be outside your tolerance level. It can be the right thing to do, but you should consider the repercussions.

Let’s start a container with --net=host and see what happens.

$ docker run -i -t --net=host ubuntu /bin/bash

root@782d18f5c38a:/# apt update

...

root@782d18f5c38a:/# apt install -y iproute2 net-tools

...

root@782d18f5c38a:/# ip addr show

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether 00:0c:29:b2:2a:21 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.16.168.178/24 brd 172.16.168.255 scope global eth0

inet6 fe80::20c:29ff:feb2:2a21/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

3: lxcbr0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether fe:59:0b:11:c2:76 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.0.3.1/24 brd 10.0.3.255 scope global lxcbr0

inet6 fe80::fc59:bff:fe11:c276/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

4: docker0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether 56:84:7a:fe:97:99 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.17.42.1/16 scope global docker0

inet6 fe80::5484:7aff:fefe:9799/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

112: vethf3e8733: <BROADCAST,UP,LOWER_UP>

link/ether b6:3e:7a:ba:5e:1c brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet6 fe80::b43e:7aff:feba:5e1c/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

That should look pretty familiar. That’s because when we run a container with the host networking option, we’re just in the host’s network namespace. Note that we’re also in the server’s UTS namespace. Our server’s hostname is docker2, so let’s see what the container’s hostname is:

root@852d18f5c38d:/# hostname docker2

If we do a mount to see what’s mounted, though, we see that Docker is still maintaining our /etc/resolv.conf, /etc/hosts, and /etc/hostname directories. Interestingly, the /etc/hostname directory simply contains the server’s hostname. Just to prove that we can see all the normal networking on the Docker server, let’s look at netstat -an to check if we can see the docker daemon running:

root@852d18f5c38d:/# netstat -an | grep 2375 tcp6 0 0 :::2375 :::* LISTEN

Note

This netstat example will work as shown only if the Docker daemon is actually listening on the unencrypted TCP port (2375). You can try to look for another server port that you know your server is using.

So we are indeed in the server’s network namespace. What all of this means is that if we were to launch a high-throughput network service, we could expect network performance from it that is essentially native. But it also means we could try to bind to ports that would collide with those on the server, so if you do this you should be careful about how you allocate port assignments.

Configuring networks

There is more to networking than just the default network or host networking, however. The docker network command lets you create multiple networks backed by different drivers. It also allows you to view and manipulate the Docker network layers and how they are attached to containers that are running on the system.

Listing the networks available from Docker’s perspective is easily accomplished with the following command:

$ docker network ls NETWORK ID NAME DRIVER c37e1476e9c1 none null d7f88e502765 host host 15dd2b3b16b1 bridge bridge

You can then find out more details about any individual network by using the docker network inspect command along with the network ID:

$ docker network inspect 15dd2b3b16b1

[{"Name":"bridge","Id":...,"Scope":"local","Driver":"bridge","IPAM":{"Driver":"default","Config":[{"Subnet":"172.18.0.0/16"}]},"Containers":{"...":{"EndpointID":"...","MacAddress":"04:42:ab:26:03:52","IPv4Address":"172.18.0.2/16","IPv6Address":""}},"Options":{"com.docker.network.bridge.default_bridge":"true","com.docker.network.bridge.enable_icc":"true","com.docker.network.bridge.enable_ip_masquerade":"true","com.docker.network.bridge.host_binding_ipv4":"0.0.0.0","com.docker.network.bridge.name":"docker0","com.docker.network.driver.mtu":"1500"}}]

Docker networks can be created and removed, as well as attached and detached from individual containers, with the network subcommand.

So far, we’ve set up a bridged network, no Docker network, and a bridged network with hairpin NAT. There are a few other drivers that you can use to create different topologies using Docker as well, with the overlay and macvlan drivers being the most common. Let’s take a brief look at what these can do for you.

overlay-

This driver is used in Swarm mode to generate a network overlay between the Docker hosts, creating a private network between all the containers that runs on top of the real network. This is useful for Swarm, but not scoped for general use with non-Swarm containers.

macvlan-

This a driver creates a real MAC address for each of your containers and then exposes them on the network via the interface of your choice. This requires that you switch gears to support more than one MAC address per physical port on the switch. The end result is that all the containers appear directly on the underlying network. When you’re moving from a legacy system to a container-native one, this can be a really useful step. There are drawbacks here, such as making it harder when debugging to identify which host traffic is really coming from, overflowing the MAC tables in your network switches, excessive ARPing by container hosts, and other underlying network issues. For that reason the

macvlandriver is not recommended unless you have a good understanding of your underlying network and can manage it effectively.There are a few sets of configurations that are possible here, but the basic setup is easy to configure:

$ docker network create -d macvlan \ --subnet=172.16.16.0/24 \ --gateway=172.16.16.1 \ -o parent=eth0 ourvlan

Tip

You can prevent Docker from allocating specific addresses by specifying them as named auxiliary addresses --aux-address="my-router=172.16.16.129".

There is a lot more you can configure with the Docker network layer. However, the defaults, host networking, and userland-proxyless mode are the ones that you’re most likely to use or encounter in the wild. Some of the other options you can configure include the container’s DNS nameservers, resolver options, and default gateways, among other things. The networking section of the Docker documentation gives an overview of how to do some of this configuration.

Note

For advanced network configuration of Docker, check out Weave—a well-supported overlay network tool for spanning containers across multiple Docker hosts, similar to the overlay driver but much more configurable, and without the Swarm requirement. Another offering, supported directly by Docker Enterprise Edition, is Project Calico. If you are running Kubernetes, which has its own networking configuration, you might also take a look at CoreOS’s flannel, which is an etcd-backed network fabric for containers.

Storage

Backing all of the images and containers on your Docker server is a storage backend that handles reading and writing all of that data. Docker has some strenuous requirements on its storage backend: it has to support layering, the mechanism by which Docker tracks changes and reduces both how much disk a container occupies and how much is shipped over the wire to deploy new images. Using a copy-on-write strategy, Docker can start up a new container from an existing image without having to copy the whole image. The storage backend supports that. The storage backend is what makes it possible to export images as groups of changes in layers, and also lets you save the state of a running container. In most cases, you need the kernel’s help in doing this efficiently. That’s because the filesystem view in your container is generally a union of all of the layers below it, which are not actually copied into your container. Instead, they are made visible to your container, and only when you make changes does anything get written to your container’s own filesystem. One place this layering mechanism is exposed to you is when you upload or download a new image from a registry like Docker Hub. The Docker daemon will push or pull each layer at a time, and if some of the layers are the same as others it has already stored, it will use the cached layer instead. In the case of a push to a registry, it will sometimes even tell you which image they are mounted from.

Docker relies on an array of possible kernel drivers to handle the layering. The Docker codebase contains code that can handle interacting with all of these backends, and you can configure the decision about which to use on daemon restart. So let’s look at what is available and some of the pluses and minuses of each.

Various backends have different limitations that may or may not make them your best option. In some cases, your choices of which backend to use are limited by what your distribution of Linux actually supports. Using the drivers that are built into the kernel shipped with your distribution will always be the easiest approach. It’s generally best to stay near the tested path here as well. We’ve seen all manner of oddities from various backends since Docker’s release. And, as usual, the common case is always the best-supported one. Different backends also report different statistics up through the Docker Remote API (/info endpoint). This is potentially useful for monitoring your Docker systems. However, not all backends are created equal, so let’s see how they differ.

- Overlay

-

Overlay (formerly OverlayFS) is a union filesystem where multiple layers are mounted together so that they appear as a single filesystem. This is the most recommended driver these days and works on most major distributions. If you are running on a Linux kernel older than 4.0 (or 3.10.0-693 for CentOS/RHEL), then you won’t be able to take advantage of this backend. The reliability and performance are good enough that it might be worth updating your OS for Docker hosts in order to support it, even if your company standard is an older distribution. Overlay is part of the mainline Linux kernel and has become increasingly stable over time. Being in the mainline means that long-term support is virtually guaranteed, which is another nice advantage. Docker supports two versions of the Overlay backend,

overlayandoverlay2. As you might expect, you are strongly advised to useoverlay2as it is faster, more efficient with inode usage, and more robust.

Note

The Docker community is frequently improving support for a variety of filesystem backends. For more details about the supported filesystems, take a look at the official documentation.

- AuFS

-

Although at the time of this writing it is no longer recommended,

aufsis the original backend. AuFS is a union filesystem driver with reasonable support on various popular Linux distributions. It was never accepted into the mainline kernel, however, and this has limited its availability on various distributions. It is not supported on recent versions of Red Hat, Fedora, or CentOS, for example. It is not shipped in the standard Ubuntu distribution, but is in the Ubuntulinux-image-extrapackage.Its status as a second-class citizen in the kernel has led to the development of many of the other backends now available. If you are running an older distribution that supports AuFS, you might consider it for stability but you should really upgrade to a kernel version that natively supports Overlay or Btrfs (discussed next).

- Btrfs

-

Btrfs is fundamentally a copy-on-write filesystem, which means it’s a pretty good fit for the Docker image model. Like

aufsand unlikedevicemapper, Docker is using the backend in the way it was intended. That means it’s both pretty stable in production and also a good performer. It scales reasonably to thousands of containers on the same system. A drawback for Red Hat–based systems is that Btrfs does not support SELinux. If you can use thebtrfsbackend, we currently recommend it as one of the most stable backends for production, after theoverlay2driver. One popular way to runbtrfsbackends for Docker containers without having to give over a whole volume to this somewhat prerelease filesystem is to make a Btrfs filesystem in a file and loopback-mount it with something likemount -o loop file.btrs /mnt. Using this method, you could build a 50 GB Docker container storage filesystem even on cloud-based systems without having to give over all your precious local storage to Btrfs. - Device Mapper

-

Originally written by Red Hat to support their distributions, which lacked AuFS in Docker’s early days, Device Mapper has become the default backend on all Red Hat–based distributions of Linux. If you run Docker Enterprise Edition or the commercially supported release on a Red Hat OS, this is your only option. Device Mapper itself has been built into the Linux kernel for ages and is very stable. The way the Docker daemon uses it is a bit unconventional, though, and in the past this backend was not that stable. This checkered past means that we prefer to pick a different backend when possible. If your distribution supports only the

devicemapperdriver, then you will likely be fine. But it’s worth considering usingoverlay2orbtrfs. By default,devicemapperutilizes theloop-lvmmode, which has zero configuration, but it is very slow and useful only for development. If you decide to use thedevicemapperdriver, it is very important that you make sure it is configured to usedirect-lvmmode for all nondevelopment environments.

Note

You can find out more about using the various devicemapper modes with Docker in the official documentation.

A 2014 blog article also provides some interesting history about the various Docker storage backends.

- VFS

-

The Virtual File System (

vfs) driver is the simplest, and slowest, to start up of the supported drivers. It doesn’t really support copy-on-write. Instead, it makes a new directory and copies over all of the existing data. It was originally intended for use in tests and for mounting host volumes. Thevfsdriver is very slow to create new containers, but runtime performance is native, which is a real benefit. Its mechanism is very simple, which means there is less to go wrong. Docker, Inc., does not recommend it for production use, so proceed with caution if you think it’s the right solution for your production environment. - ZFS

-

ZFS, originally created by Sun Microsystems, is the most advanced open source filesystem available on Linux. Due to licensing restrictions, it does not ship in mainline Linux. However, the ZFS On Linux project has made it pretty easy to install. Docker can then run on top of the ZFS filesystem and use its advanced copy-on-write facilities to implement layering. Given that ZFS is not in the mainline kernel and not available off the shelf in the major commercial distributions, however, going this route requires some extended effort. If you are already running ZFS in production, however, then this is probably your very best option.

Warning

Storage backends can have a big impact on the performance of your containers. And if you swap the backend on your Docker server, all of your existing images will disappear. They are not gone, but they will not be visible until you switch the driver back. Caution is advised.

You can use docker info to see which storage backend your system is running:

$ docker info ... Storage Driver: overlay2 Backing Filesystem: extfs Supports d_type: true Native Overlay Diff: true ...

As you can see, Docker will also tell you what the underlying or “backing” filesystem is in cases where there is one. Since we’re running overlay2 here, we can see it’s backed by an ext filesystem. In some cases, like with devicemapper on raw partitions or with btrfs, there won’t be a different underlying filesystem.

Storage backends can be swapped via command-line arguments to docker on startup. If we wanted to switch our Ubuntu system from aufs to devicemapper, we would do so like this:

$ dockerd --storage-driver=devicemapper

That will work on pretty much any Linux system that can support Docker because devicemapper is almost always present. The same holds true for overlay2 on modern Linux kernels. However, you will need to have the actual underlying dependencies in place for the other drivers. For example, without aufs in the kernel—usually via a kernel module—Docker will not start up with aufs set as the storage driver, and the same holds true for Btrfs or ZFS.

Getting the appropriate storage driver for your systems and deployment needs is one of the more important technical points to get right when you’re taking Docker to production. Be conservative; make sure the path you choose is well supported in your kernel and distribution. Historically this was a pain point, but most of the drivers have reached reasonable maturity. Remain cautious for any newly appearing backends, however, as this space continues to change. Getting new backend drivers to work reliably for production systems takes quite some time, in our experience.

The Structure of Docker

What we think of as Docker is made of five major server-side components that present a common front via the API. These parts are dockerd, containerd, runc, docker-containerd-shim, and the docker-proxy we described in “Networking”. We’ve spent a lot of time interacting with dockerd and the API it presents. It is, in fact, responsible for orchestrating the whole set of components that make up Docker. But when it starts a container, Docker relies on containerd to handle instantiating the container. All of this used to be handled in the dockerd process itself, but there were a number of shortcomings to that design:

-

dockerdhad a huge number of jobs. -

A monolithic runtime prevented any of the components from being swapped out easily.

-

dockerdhad to supervise the lifecycle of the containers themselves and it couldn’t be restarted or upgraded without losing all the running containers.

Another one of the major motivations for containerd was that, as we’ve just shown, containers are not just a single abstraction. On the Linux platform, they are a process involving namespaces, cgroups, and security rules in AppArmor or SELinux. But Docker runs on Windows and will likely work on other platforms in the future. The idea of containerd is to present a standard layer to the outside world where, regardless of implementation, developers can think about the higher-level concepts of containers, tasks, and snapshots rather than worrying about specific Linux system calls. This simplifies the Docker daemon quite a lot, and enables platforms like Kubernetes to integrate directly into containerd rather than using the Docker API. Kubernetes currently supports both methods, though it normally talks to Docker directly. In theory, you could replace containerd with an API-compatible layer, something that doesn’t talk to containers at all, but at this time there aren’t any alternatives that we know of.

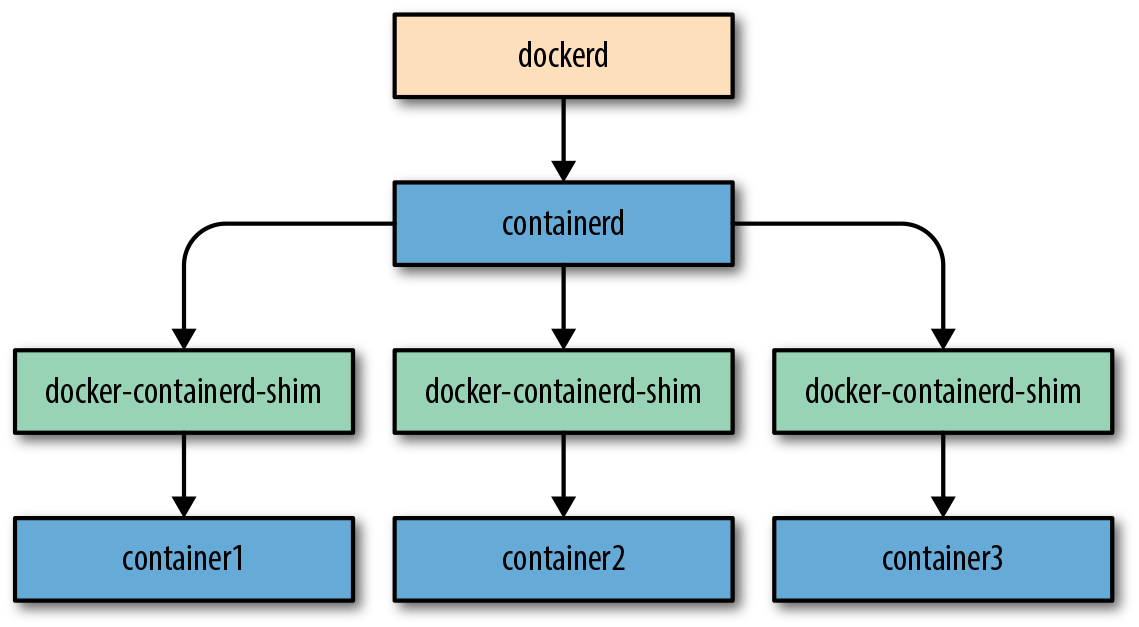

Let’s take a look at the components (shown in Figure 11-2) and see what each of them does:

dockerd-

One per server. Serves the API, builds container images, and does high-level network management including volumes, logging, statistics reporting, and more.

containerd-

One per server. Manages lifecycle, execution, copy-on-write filesystem, and low-level networking drivers.

docker-containerd-shim-

One per container. Handles file descriptors passed to the container (e.g.,

stdin/out) and reports exit status. runc-

Constructs the container and executes it, gathers statistics, and reports events on lifecycle.

Figure 11-2. Structure of Docker

dockerd and containerd speak to each other over a socket, usually a Unix socket, using a gRPC API. dockerd is the client in this case, and containerd is the server! runc is a CLI tool that reads configuration from JSON on disk and is executed by containerd.

When we start a new container, dockerd will handle making sure that the image is present or will pull it from the repository specified in the image name. (In the future this responsibility may shift to containerd, which already supports image pulls.) The Docker daemon also does most of the rest of the setup around the container, like setting up any logging drivers and volumes or volume drivers. It then talks to containerd and asks it to run the container. containerd will take the image and apply the container configuration passed in from dockerd to generate an OCI (Open Container Initiative) bundle that runc can execute.2 It will then execute docker-containerd-shim to start the container. This will in turn execute runc to actually construct and start the container. However, runc will not stay running, and the docker-containerd-shim will be the actual parent process of the new container process.