Chapter 2. The Docker Landscape

Before you dive into configuring and installing Docker, a broad survey is in order to explain what Docker is and what it brings to the table. It is a powerful technology, but not a tremendously complicated one at its core. In this chapter, we’ll cover the generalities of how Docker works, what makes it powerful, and some of the reasons you might use it. If you’re reading this, you probably have your own reasons to use Docker, but it never hurts to augment your understanding before you jump in.

Don’t worry—this chapter should not hold you up for too long. In the next chapter, we’ll dive right into getting Docker installed and running on your system.

Process Simplification

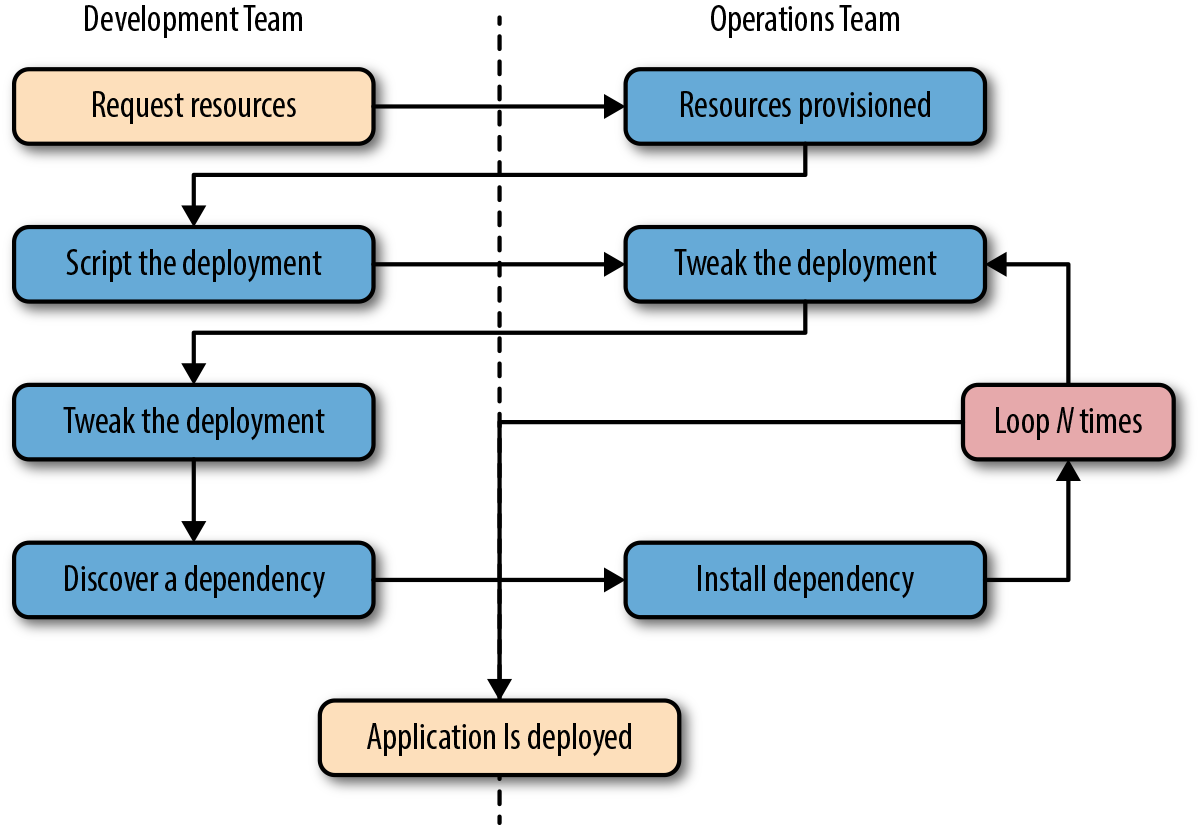

Because Docker is a piece of software, it may not be obvious that it can also have a big positive impact on company and team processes if it is adopted well. So, let’s dig in and see how Docker can simplify both workflows and communication. This usually starts with the deployment story. Traditionally, the cycle of getting an application to production often looks something like the following (illustrated in Figure 2-1):

-

Application developers request resources from operations engineers.

-

Resources are provisioned and handed over to developers.

-

Developers script and tool their deployment.

-

Operations engineers and developers tweak the deployment repeatedly.

-

Additional application dependencies are discovered by developers.

-

Operations engineers work to install the additional requirements.

-

Loop over steps 5 and 6 N more times.

-

The application is deployed.

Figure 2-1. A traditional deployment workflow (without Docker)

Our experience has shown that when you are following traditional processes, deploying a brand new application into production can take the better part of a week for a complex new system. That’s not very productive, and even though DevOps practices work to alleviate some of the barriers, it often requires a lot of effort and communication between teams of people. This process can be both technically challenging and expensive, but even worse, it can limit the kinds of innovation that development teams will undertake in the future. If deploying software is hard, time-consuming, and dependent on resources from another team, then developers may just build everything into the existing application in order to avoid suffering the new deployment penalty.

Push-to-deploy systems like Heroku have shown developers what the world can look like if you are in control of most of your dependencies as well as your application. Talking with developers about deployment will often turn up discussions of how easy things are on Heroku or similar systems. If you’re an operations engineer, you’ve probably heard complaints about how much slower your internal systems are compared with deploying on Heroku.

Heroku is a whole environment, not just a container engine. While Docker doesn’t try to be everything that is included in Heroku, it provides a clean separation of responsibilities and encapsulation of dependencies, which results in a similar boost in productivity. Docker also allows even more fine-grained control than Heroku by putting developers in control of everything, down to the OS distribution on which they ship their application. Some of the tooling and orchestrators built (e.g., Kubernetes, Swarm, or Mesos) on top of Docker now aim to replicate the simplicity of Heroku. But even though these platforms wrap more around Docker to provide a more capable and complex environment, a simple platform that uses only Docker still provides all of the core process benefits without the added complexity of a larger system.

As a company, Docker adopts an approach of “batteries included but removable.” This means that they want their tools to come with everything most people need to get the job done, while still being built from interchangeable parts that can easily be swapped in and out to support custom solutions.

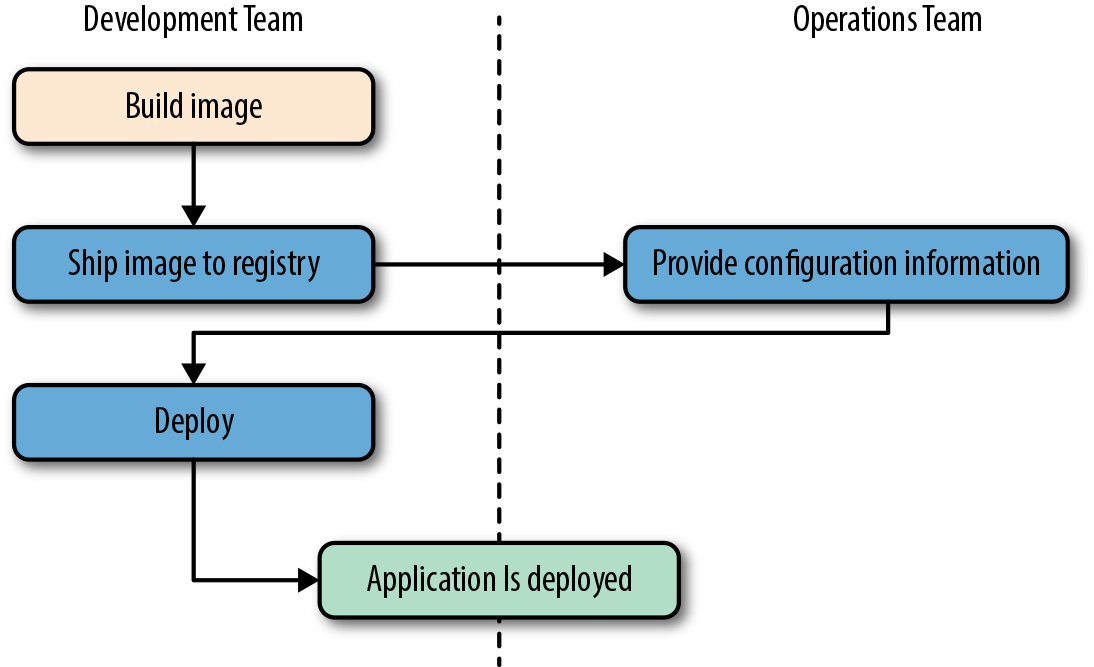

By using an image repository as the hand-off point, Docker allows the responsibility of building the application image to be separated from the deployment and operation of the container. What this means in practice is that development teams can build their application with all of its dependencies, run it in development and test environments, and then just ship the exact same bundle of application and dependencies to production. Because those bundles all look the same from the outside, operations engineers can then build or install standard tooling to deploy and run the applications. The cycle described in Figure 2-1 then looks somewhat like this (illustrated in Figure 2-2):

-

Developers build the Docker image and ship it to the registry.

-

Operations engineers provide configuration details to the container and provision resources.

-

Developers trigger deployment.

Figure 2-2. A Docker deployment workflow

This is possible because Docker allows all of the dependency issues to be discovered during the development and test cycles. By the time the application is ready for first deployment, that work is done. And it usually doesn’t require as many handoffs between the development and operations teams. That’s a lot simpler and saves a lot of time. Better yet, it leads to more robust software through testing of the deployment environment before release.

Broad Support and Adoption

Docker is already well supported, with the majority of the large public clouds offering some direct support for it. For example, Docker runs in AWS via multiple products like Elastic Container Service (ECS), Elastic Container Service for Kubernetes (EKS), Fargate, and Elastic Beanstalk. Docker can also be used on Google AppEngine, Google Kubernetes Engine, Red Hat OpenShift, IBM Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Rackspace Cloud, Docker’s own Docker Cloud, and many more. At DockerCon 2014, Google’s Eric Brewer announced that Google would be supporting Docker as its primary internal container format. Rather than just being good PR for these companies, what this meant for the Docker community was that a lot of money began to back the stability and success of the Docker platform.

Further building its influence, Docker’s containers are becoming the lingua franca between cloud providers, offering the potential for “write once, run anywhere” cloud applications. When Docker released their libswarm development library at DockerCon 2014, an engineer from Orchard demonstrated deploying a Docker container to a heterogeneous mix of cloud providers at the same time. This kind of orchestration had not been easy before because every cloud provider provided a different API or toolset for managing instances, which were usually the smallest item you could manage with an API. What was only a promise from Docker in 2014 has since become fully mainstream as the largest companies continue to invest in the platform, support, and tooling. With most providers offering some form of Docker orchestration as well as the container runtime itself, Docker is already well supported for nearly any kind of workload in common production environments. If all of your tooling is around Docker, your applications can be deployed in a cloud-agnostic manner, allowing a huge new flexibility not previously possible.

That covers Docker containers and tooling, but what about OS vendor support and adoption? The Docker client runs directly on most major operating systems, and the server can run on Linux or Windows Server. The vast majority of the ecosystem is built around Linux servers, but other platforms are increasingly being supported. The beaten path is and will likely continue to be Linux servers running Linux containers.

Note

It is actually possible to run Windows containers natively (without a VM) on 64-bit versions of Windows Server 2016. However, 64-bit versions of Windows 10 Professional still require Hyper-V to provide the Windows Server kernel that is used for Windows containers. We dive into a little more detail about this in “Windows Containers”.

In order to support the growing demand for Docker tooling in development environments, Docker has released easy-to-use implementations for macOS and Windows. These appear to run natively but are still sitting on top of a Linux kernel underneath. Docker has traditionally been developed on the Ubuntu Linux distribution, but most Linux distributions and other major operating systems are now supported where possible. RedHat, for example, has gone all-in on containers and all of their platforms have first-class support for Docker. With the near ubiquity of containers in the Linux realm, we now have distributions like Red Hat’s CoreOS, which is built entirely on top of Docker containers, either running on Docker itself or under their own rkt runtime.

In the first years after Docker’s release, a set of competitors and service providers voiced concerns about Docker’s proprietary image format. Containers on Linux did not have a standard image format, so Docker, Inc., created their own according to the needs of their business.

Service providers and commercial vendors were particularly reluctant to build platforms subject to the whim of a company with somewhat overlapping interests to their own. Docker as a company faced some public challenges in that period as a result. In order to support wider adoption, Docker, Inc., then helped sponsor the Open Container Initiative (OCI) in June 2015. The first full specification from that effort was released in July 2017, and was based in large part on version 2 of the Docker image format. The OCI is working on the certification process and it will soon be possible for implementations to be OCI certified. In the meantime, there are at least four runtimes claiming to implement the spec: runc, which is part of Docker; railcar, an alternate implementation by Oracle; Kata Containers (formerly Clear Containers) from Intel, Hyper, and the OpenStack Foundation, which run a mix of containers and virtual machines; and finally, the gVisor runtime from Google, which is implemented entirely in user space. This set is likely to grow, with plans for CoreOS’s rkt to become OCI compliant, and others are likely to follow.

The space around deploying containers and orchestrating entire systems of containers continues to expand, too. Many of these are open source and available both on premise and as cloud or SaaS offerings from various providers, either in their own clouds or yours. Given the amount of investment pouring into the Docker space, it’s likely that Docker will continue to cement itself further into the fabric of the modern internet.

Architecture

Docker is a powerful technology, and that often means something that comes with a high level of complexity. And, under the hood, Docker is fairly complex; however, its fundamental user-facing structure is indeed a simple client/server model. There are several pieces sitting behind the Docker API, including containerd and runc, but the basic system interaction is a client talking over an API to a server. Underneath this simple exterior, Docker heavily leverages kernel mechanisms such as iptables, virtual bridging, cgroups, namespaces, and various filesystem drivers. We’ll talk about some of these in Chapter 11. For now, we’ll go over how the client and server work and give a brief introduction to the network layer that sits underneath a Docker container.

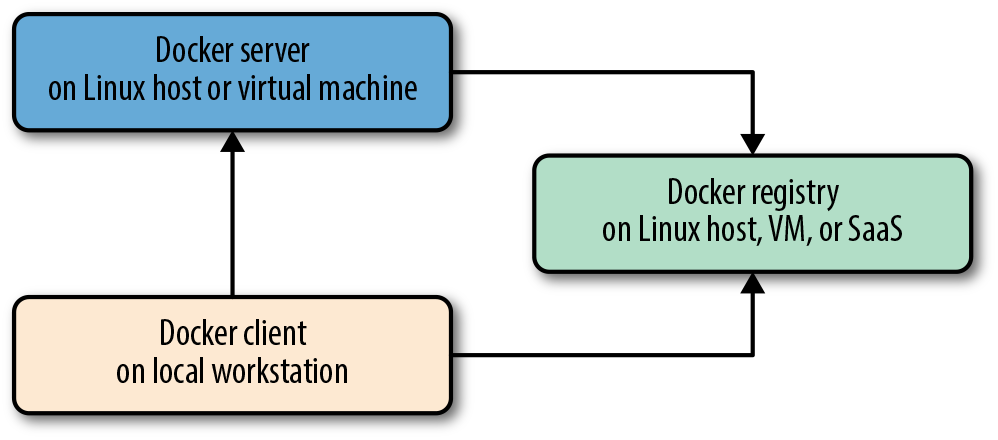

Client/Server Model

It’s easiest to think of Docker as consisting of two parts: the client and the server/daemon (see Figure 2-3). Optionally there is a third component called the registry, which stores Docker images and their metadata. The server does the ongoing work of building, running, and managing your containers, and you use the client to tell the server what to do. The Docker daemon can run on any number of servers in the infrastructure, and a single client can address any number of servers. Clients drive all of the communication, but Docker servers can talk directly to image registries when told to do so by the client. Clients are responsible for telling servers what to do, and servers focus on hosting containerized applications.

Figure 2-3. Docker client/server model

Docker is a little different in structure from some other client/server software. It has a docker client and a dockerd server, but rather than being entirely monolithic, the server then orchestrates a few other components behind the scene on behalf of the client, including docker-proxy, runc, containerd, and sometimes docker-init. Docker cleanly hides any complexity behind the simple server API, though, so you can just think of it as a client and server for most purposes. Each Docker host will normally have one Docker server running that can manage a number of containers. You can then use the docker command-line tool client to talk to the server, either from the server itself or, if properly secured, from a remote client. We’ll talk more about that shortly.

Network Ports and Unix Sockets

The docker command-line tool and dockerd daemon talk to each other over network sockets. Docker, Inc., has registered two ports with IANA for use by the Docker daemon and client: TCP ports 2375 for unencrypted traffic and 2376 for encrypted SSL connections. Using a different port is easily configurable for scenarios where you need to use different settings. The default setting for the Docker installer is to use only a Unix socket to make sure the system defaults to the most secure installation, but this is also easily configurable. The Unix socket can be located in different paths on different operating systems, so you should check where yours is located (often /var/run/docker.sock). If you have strong preferences for a different location, you can usually specify this at install time or simply change the server configuration afterward and restart the daemon. If you don’t, then the defaults will probably work for you. As with most software, following the defaults will save you a lot of trouble if you don’t need to change them.

Robust Tooling

Among the many things that have led to Docker’s growing adoption is its simple and powerful tooling. Since its initial release, its capabilities have been expanding ever wider, thanks to efforts from the Docker community at large. The tooling that Docker ships with supports building Docker images, basic deployment to individual Docker daemons, a distributed mode called Swarm mode, and all the functionality needed to actually manage a remote Docker server. Beyond the included Swarm mode, community efforts have focused on managing whole fleets (or clusters) of Docker servers and scheduling and orchestrating container deployments.

Note

One point of confusion for people who search for Docker Swarm information on the internet is that there are two different things sharing that name. There was an older, now deprecated project that was a standalone application, called “Docker Swarm,” and there is a newer, built-in Swarm that we refer to here as “Swarm mode.” You’ll need to carefully look at the search results to identify the relevant ones. Over time this conflict will hopefully become moot as the older product fades into history.

Docker has also launched its own orchestration toolset, including Compose, Machine, and Swarm, which creates a cohesive deployment story for developers. Docker’s offerings in the production orchestration space have been largely over-shadowed by Google’s Kubernetes and the Apache Mesos project in current deployments. But Docker’s orchestration tools remain useful, with Compose being particularly handy for local development.

Because Docker provides both a command-line tool and a remote web API, it is easy to add further tooling in any language. The command-line tool lends itself well to shell scripting, and a lot of power can easily be leveraged with simple wrappers around it. The tool also provides a huge amount of functionality itself, all targeted at an individual Docker daemon.

Docker Command-Line Tool

The command-line tool docker is the main interface that most people will have with Docker. This is a Go program that compiles and runs on all common architectures and operating systems. The command-line tool is available as part of the main Docker distribution on various platforms and also compiles directly from the Go source. Some of the things you can do with the Docker command-line tool include, but are not limited to:

-

Build a container image.

-

Pull images from a registry to a Docker daemon or push them up to a registry from the Docker daemon.

-

Start a container on a Docker server either in the foreground or background.

-

Retrieve the Docker logs from a remote server.

-

Start a command-line shell inside a running container on a remote server.

-

Monitor statistics about your container.

-

Get a process listing from your container.

You can probably see how these can be composed into a workflow for building, deploying, and observing applications. But the Docker command-line tool is not the only way to interact with Docker, and it’s not necessarily the most powerful.

Docker Engine API

Like many other pieces of modern software, the Docker daemon has a remote web application programming interface (API). This is in fact what the Docker command-line tool uses to communicate with the daemon. But because the API is documented and public, it’s quite common for external tooling to use the API directly. This enables all manners of tooling, from mapping deployed Docker containers to servers, to automated deployments, to distributed schedulers. While it’s very likely that beginners will not initially want to talk directly to the Docker API, it’s a great tool to have available. As your organization embraces Docker over time, it’s likely that you will increasingly find the API to be a good integration point for this tooling.

Extensive documentation for the API is on the Docker site. As the ecosystem has matured, robust implementations of Docker API libraries have emerged for all popular languages. Docker maintains SDKs for Python and Go, but the best libraries remain those maintained by third parties. We’ve used the much more extensive third-party Go and Ruby libraries, for example, and have found them to be both robust and rapidly updated as new versions of Docker are released.

Most of the things you can do with the Docker command-line tooling are supported relatively easily via the API. Two notable exceptions are the endpoints that require streaming or terminal access: running remote shells or executing the container in interactive mode. In these cases, it’s often easier to use one of these solid client libraries or the command-line tool.

Container Networking

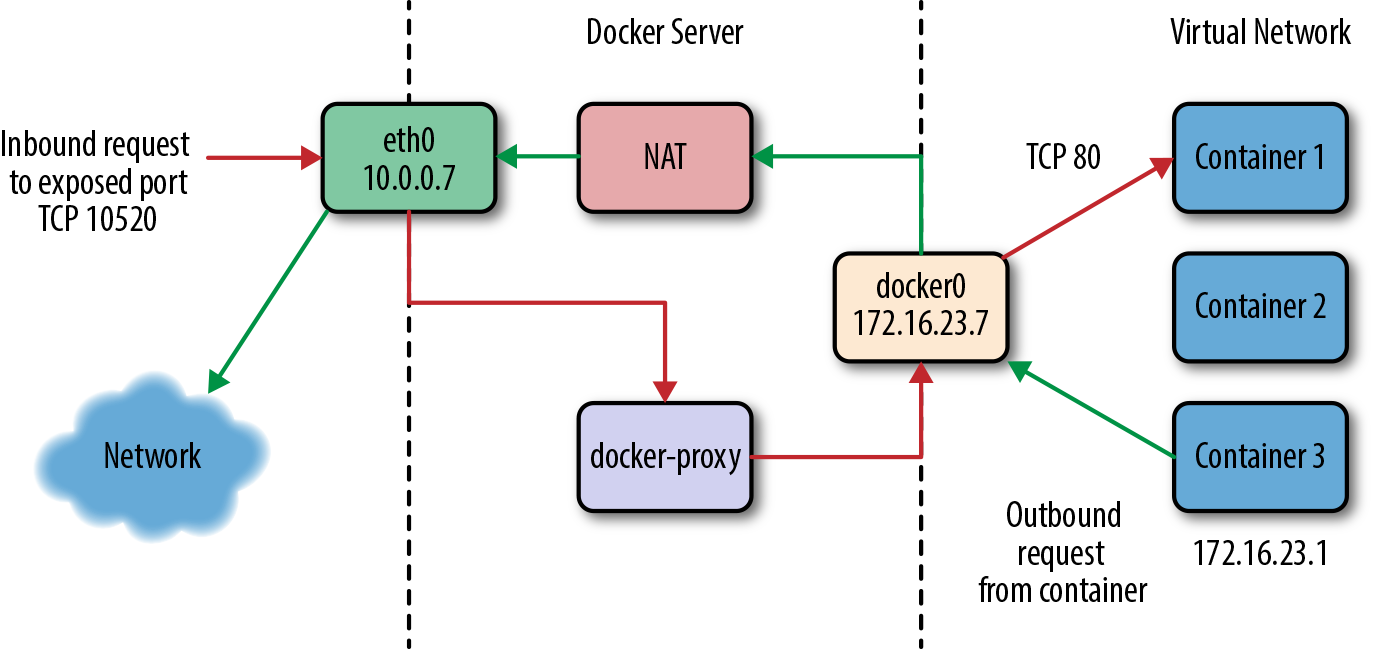

Even though Docker containers are largely made up of processes running on the host system itself, they usually behave quite differently from other processes at the network layer. Docker initially supported a single networking model, but now supports a robust assortment of configurations that handle most application requirements. Most people run their containers in the default configuration, called bridge mode. So let’s take a look at how it works.

To understand bridge mode, it’s easiest to think of each of your Docker containers as behaving like a host on a private network. The Docker server acts as a virtual bridge and the containers are clients behind it. A bridge is just a network device that repeats traffic from one side to another. So you can think of it like a mini–virtual network with each container acting like a host attached to that network.

The actual implementation, as shown in Figure 2-4, is that each container has its own virtual Ethernet interface connected to the Docker bridge and its own IP address allocated to the virtual interface. Docker lets you bind and expose individual or groups of ports on the host to the container so that the outside world can reach your container on those ports. That traffic passes over a proxy that is also part of the Docker daemon before getting to the container.

Docker allocates the private subnet from an unused RFC 1918 private subnet block. It detects which network blocks are unused on the host and allocates one of those to the virtual network. That is bridged to the host’s local network through an interface on the server called docker0. This means that all of the containers are on a network together and can talk to each other directly. But to get to the host or the outside world, they go over the docker0 virtual bridge interface. As we mentioned, inbound traffic goes over the proxy. This proxy is fairly high performance but can be limiting if you run high-throughput applications in containers.

Figure 2-4. The network on a typical Docker server

There is a dizzying array of ways in which you can configure Docker’s network layer, from allocating your own network blocks to configuring your own custom bridge interface. People often run with the default mechanisms, but there are times when something more complex or specific to your application is required. You can find much more detail about Docker networking in the documentation, and we will cover more details in the Chapter 11.

Note

When developing your Docker workflow, you should definitely get started with the default networking approach. You might later find that you don’t want or need this default virtual network. Networking is configurable per container, and you can switch off the whole virtual network layer entirely for a container using the --net=host switch to docker run. When running in that mode, Docker containers use the host’s own network devices and address and no virtual interfaces or bridge are provisioned. Note that host networking has security implications you might need to consider. Other network topologies are possible and discussed in Chapter 11.

Getting the Most from Docker

Like most tools, Docker has a number of great use cases, and others that aren’t so good. You can, for example, open a glass jar with a hammer. But that has its downsides. Understanding how to best use the tool, or even simply determining if it’s the right tool, can get you on the correct path much more quickly.

To begin with, Docker’s architecture aims it squarely at applications that are either stateless or where the state is externalized into data stores like databases or caches. Those are the easiest to containerize. Docker enforces some good development principles for this class of application, and we’ll talk later about how that’s powerful. But this means doing things like putting a database engine inside Docker is a bit like swimming against the current. It’s not that you can’t do it, or even that you shouldn’t do it; it’s just that this is not the most obvious use case for Docker, so if it’s the one you start with, you may find yourself disappointed early on. Databases that run well in Docker are often now deployed this way, but this is not the simple path. Some good applications for beginning with Docker include web frontends, backend APIs, and short-running tasks like maintenance scripts that might normally be handled by cron.

If you focus first on building an understanding of running stateless or externalized-state applications inside containers, you will have a foundation on which to start considering other use cases. We strongly recommend starting with stateless applications and learning from that experience before tackling other use cases. Note that the community is working hard on how to better support stateful applications in Docker, and there are likely to be many developments in this area.

Containers Are Not Virtual Machines

A good way to start shaping your understanding of how to leverage Docker is to think of containers not as virtual machines but as very lightweight wrappers around a single Unix process. During actual implementation, that process might spawn others, but on the other hand, one statically compiled binary could be all that’s inside your container (see “Outside Dependencies” for more information). Containers are also ephemeral: they may come and go much more readily than a traditional virtual machine.

Virtual machines are by design a stand-in for real hardware that you might throw in a rack and leave there for a few years. Because a real server is what they’re abstracting, virtual machines are often long-lived in nature. Even in the cloud where companies often spin virtual machines up and down on demand, they usually have a running lifespan of days or more. On the other hand, a particular container might exist for months, or it may be created, run a task for a minute, and then be destroyed. All of that is OK, but it’s a fundamentally different approach than the one virtual machines are typically used for.

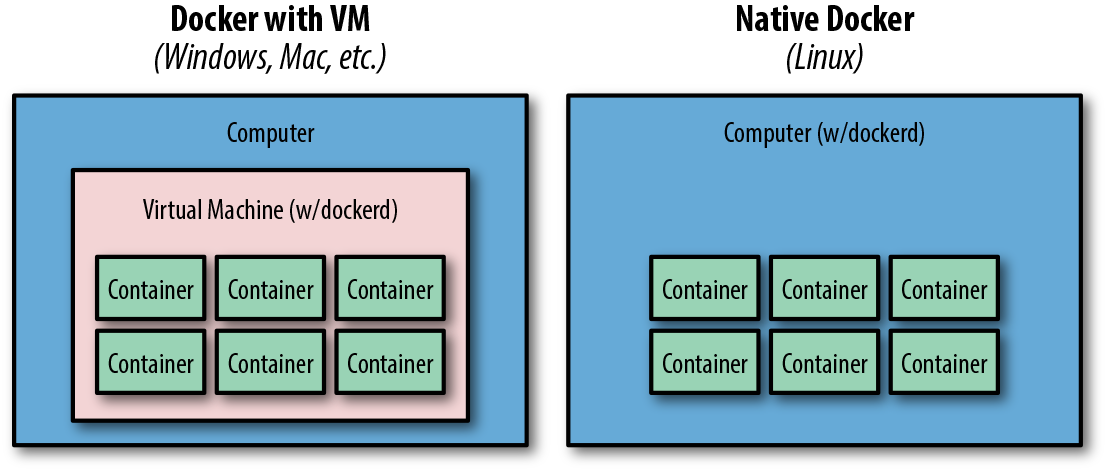

To help drive this differentiation home, if you run Docker on a Mac or Windows system you are leveraging a Linux virtual machine to run dockerd, the Docker server. However, on Linux dockerd can be run natively and therefore there is no need for a virtual machine to be run anywhere on the system (see Figure 2-5).

Figure 2-5. Typical Docker installations

Limited Isolation

Containers are isolated from each other, but that isolation is probably more limited than you might expect. While you can put limits on their resources, the default container configuration just has them all sharing CPU and memory on the host system, much as you would expect from colocated Unix processes. This means that unless you constrain them, containers can compete for resources on your production machines. That is sometimes what you want, but it impacts your design decisions. Limits on CPU and memory use are encouraged through Docker, but in most cases they are not the default like they would be from a virtual machine.

It’s often the case that many containers share one or more common filesystem layers. That’s one of the more powerful design decisions in Docker, but it also means that if you update a shared image, you may want to recreate a number of containers that still use the older one.

Containerized processes are just processes on the Docker server itself. They are running on the same exact instance of the Linux kernel as the host operating system. They even show up in the ps output on the Docker server. That is utterly different from a hypervisor, where the depth of process isolation usually includes running an entirely separate instance of the operating system kernel for each virtual machine.

This light containment can lead to the tempting option of exposing more resources from the host, such as shared filesystems to allow the storage of state. But you should think hard before further exposing resources from the host into the container unless they are used exclusively by the container. We’ll talk about security of containers later, but generally you might consider helping to enforce isolation further by applying SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) or AppArmor policies rather than compromising the existing barriers.

Warning

By default, many containers use UID 0 to launch processes. Because the container is contained, this seems safe, but in reality it isn’t. Because everything is running on the same kernel, many types of security vulnerabilities or simple misconfiguration can give the container’s root user unauthorized access to the host’s system resources, files, and processes. Refer to “Security” for a discussion of how to mitigate this.

Containers Are Lightweight

We’ll get more into the details of how this works later, but creating a container takes very little space. A quick test reveals that a newly created container from an existing image takes a whopping 12 kilobytes of disk space. That’s pretty lightweight. On the other hand, a new virtual machine created from a golden image might require hundreds or thousands of megabytes. The new container is so small because it is just a reference to a layered filesystem image and some metadata about the configuration. There is no copy of the data allocated to the container. Containers are just processes on the existing system, so there may not be a need to copy any data for the exclusive use of the container.

The lightness of containers means that you can use them for situations where creating another virtual machine would be too heavyweight or where you need something to be truly ephemeral. You probably wouldn’t, for instance, spin up an entire virtual machine to run a curl command to a website from a remote location, but you might spin up a new container for this purpose.

Toward an Immutable Infrastructure

By deploying most of your applications within containers, you can start simplifying your configuration management story by moving toward an immutable infrastructure, where components are replaced entirely rather than being changed in place. The idea of an immutable infrastructure has gained popularity in response to how difficult it is, in reality, to maintain a truly idempotent configuration management codebase. As your configuration management codebase grows, it can become as unwieldy and unmaintainable as large, monolithic legacy applications.

With Docker it is possible to deploy a very lightweight Docker server that needs almost no configuration management, or in many cases, none at all. You handle all of your application management simply by deploying and redeploying containers to the server. When the server needs an important update to something like the Docker daemon or the Linux kernel, you can simply bring up a new server with the changes, deploy your containers there, and then decommission or reinstall the old server.

Container-based Linux distributions like RedHat’s CoreOS are designed around this principle. But rather than requiring you to decommission the instance, CoreOS can entirely update itself and switch to the updated OS. Your configuration and workload largely remain in your containers and you don’t have to configure the OS very much at all.

Because of this clean separation between deployment and configuration of your servers, many container-based production systems are now using tools such as HashiCorp’s Packer to build cloud virtual server images and then leveraging Docker to nearly or entirely avoid configuration management systems.

Stateless Applications

A good example of the kind of application that containerizes well is a web application that keeps its state in a database. Stateless applications are normally designed to immediately answer a single self-contained request, and have no need to track information between requests from one or more clients. You might also run something like ephemeral memcache instances in containers. If you think about your web application, though, it probably has local state that you rely on, like configuration files. That might not seem like a lot of state, but it means that you’ve limited the reusability of your container and made it more challenging to deploy into different environments, without maintaining configuration data in your codebase.

In many cases, the process of containerizing your application means that you move configuration state into environment variables that can be passed to your application from the container. Rather than baking the configuration into the container, you apply the configuration to the container at deployment time. This allows you to easily do things like use the same container to run in either production or staging environments. In most companies, those environments would require many different configuration settings, from the names of databases to the hostnames of other service dependencies.

With containers, you might also find that you are always decreasing the size of your containerized application as you optimize it down to the bare essentials required to run. We have found that thinking of anything that you need to run in a distributed way as a container can lead to some interesting design decisions. If, for example, you have a service that collects some data, processes it, and returns the result, you might configure containers on many servers to run the job and then aggregate the response on another container.

Externalizing State

If Docker works best for stateless applications, how do you best store state when you need to? Configuration is best passed by environment variables, for example. Docker supports environment variables natively, and they are stored in the metadata that makes up a container configuration. This means that restarting the container will ensure that the same configuration is passed to your application each time. It also makes the configuration of the container easily observable while it’s running, which can make debugging a lot easier.

Databases are often where scaled applications store state, and nothing in Docker interferes with doing that for containerized applications. Applications that need to store files, however, face some challenges. Storing things to the container’s filesystem will not perform well, will be extremely limited by space, and will not preserve state across a container lifecycle. If you redeploy a stateful service without utilizing storage external to the container, you will lose all of that state. Applications that need to store filesystem state should be considered carefully before you put them into Docker. If you decide that you can benefit from Docker in these cases, it’s best to design a solution where the state can be stored in a centralized location that could be accessed regardless of which host a container runs on. In certain cases, this might mean using a service like Amazon S3, EBS volumes, HDFS, OpenStack Swift, a local block store, or even mounting EBS volumes or iSCSI disks inside the container. Docker volume plug-ins provide some options here and are briefly discussed in Chapter 11.

Tip

Although it is possible to externalize state on an attached filesystem, it is not generally encouraged by the community, and should be considered an advanced use case. It is strongly recommended that you start with applications that don’t need persistent state. There are multiple reasons why this is typically discouraged, but in almost all cases it is because it introduces dependencies between the container and the host that interfere with using Docker as a truly dynamic, horizontally scalable application delivery service. If your container relies on an attached filesystem, it can only be deployed to the system that contains this filesystem. Remote volumes that can be dynamically attached are a good solution, but also an advanced use case.

The Docker Workflow

Like many tools, Docker strongly encourages a particular workflow. It’s a very enabling workflow that maps well to how many companies are organized, but it’s probably a little different than what you or your team are doing now. Having adapted our own organizations’ workflow to the Docker approach, we can confidently say that this change is a benefit that touches many teams in the organization. If the workflow is implemented well, it can help realize the promise of reduced communication overhead between teams.

Revision Control

The first thing that Docker gives you out of the box is two forms of revision control. One is used to track the filesystem layers that comprise images, and the other is a tagging systems for images.

Filesystem layers

Docker containers are made up of stacked filesystem layers, each identified by a unique hash, where each new set of changes made during the build process is laid on top of the previous changes. That’s great, because it means that when you do a new build, you only have to rebuild the layers that follow the change you’re deploying. This saves time and bandwidth because containers are shipped around as layers and you don’t have to ship layers that a server already has stored. If you’ve done deployments with many classic deployment tools, you know that you can end up shipping hundreds of megabytes of the same data to a server over and over at each deployment. That’s slow, and worse, you can’t really be sure exactly what changed between deployments. Because of the layering effect, and because Docker containers include all of the application dependencies, with Docker you can be quite sure where the changes happened.

To simplify this a bit, remember that a Docker image contains everything required to run your application. If you change one line of code, you certainly don’t want to waste time rebuilding every dependency your code requires into a new image. Instead, Docker will use as many base layers as it can so that only the layers affected by the code change are rebuilt.

Image tags

The second kind of revision control offered by Docker is one that makes it easy to answer an important question: what was the previous version of the application that was deployed? That’s not always easy to answer. There are a lot of solutions for non-Dockerized applications, from Git tags for each release, to deployment logs, to tagged builds for deployment, and many more. If you’re coordinating your deployment with Capistrano, for example, it will handle this for you by keeping a set number of previous releases on the server and then using symlinks to make one of them the current release.

But what you find in any scaled production environment is that each application has a unique way of handling deployment revisions. Many of them do the same thing, but some may be different. Worse, in heterogeneous language environments, the deployment tools are often entirely different between applications and very little is shared. So the question of “What was the previous version?” can have many answers depending on whom you ask and about which application. Docker has a built-in mechanism for handling this: it provides image tagging at deployment time. You can leave multiple revisions of your application on the server and just tag them at release. This is not rocket science, and it’s not functionality that is hard to find in other deployment tooling, as we mention. But it can easily be made standard across all of your applications, and everyone can have the same expectations about how things will be tagged for all applications. This makes communication easier between teams and it makes tooling much simpler because there is one source of truth for build versions.

Warning

In many examples on the internet and in this book, you will see people use the latest tag. This is useful when you’re getting started and when you’re writing examples, as it will always grab the most recent version of a image. But since this is a floating tag, it is a really bad idea to use latest in most production workflows, as your dependencies can get updated out from under you, and it is impossible to roll back to latest because the old version is no longer the one tagged latest. It also makes it hard to verify if the same image is running on different servers. The rule of thumb is: don’t use the latest tag in production. It’s not even a good idea to use the latest tag from upstream images, for the same reasons.

Building

Building applications is a black art in many organizations, where a few people know all the levers to pull and knobs to turn in order to spit out a well-formed, shippable artifact. Part of the heavy cost of getting a new application deployed is getting the build right. Docker doesn’t solve all the problems, but it does provide a standardized tool configuration and toolset for builds. That makes it a lot easier for people to learn to build your applications, and to get new builds up and running.

The Docker command-line tool contains a build flag that will consume a Dockerfile and produce a Docker image. Each command in a Dockerfile generates a new layer in the image, so it’s easy to reason about what the build is going to do by looking at the Dockerfile itself. The great part of all of this standardization is that any engineer who has worked with a Dockerfile can dive right in and modify the build of any other application. Because the Docker image is a standardized artifact, all of the tooling behind the build will be the same regardless of the language being used, the OS distribution it’s based on, or the number of layers needed. The Dockerfile is checked into a revision control system, which also means tracking changes to the build is simplified. Modern multistage Docker builds also allow you to define the build environment separately from the final artifact image. This provides huge configurability for your build environment just like you’d have for a production container.

Most Docker builds are a single invocation of the docker build command and generate a single artifact, the container image. Because it’s usually the case that most of the logic about the build is wholly contained in the Dockerfile, it’s easy to create standard build jobs for any team to use in build systems like Jenkins. As a further standardization of the build process, many companies—eBay, for example—have standardized Docker containers to do the image builds from a Dockerfile. SaaS build offerings like Travis CI and Codeship also have first-class support for Docker builds.

Testing

While Docker itself does not include a built-in framework for testing, the way containers are built lends some advantages to testing with Docker containers.

Testing a production application can take many forms, from unit testing to full integration testing in a semi-live environment. Docker facilitates better testing by guaranteeing that the artifact that passed testing will be the one that ships to production. This can be guaranteed because we can either use the Docker SHA for the container, or a custom tag to make sure we’re consistently shipping the same version of the application.

Since, by design, containers include all of their dependencies, tests run on containers are very reliable. If a unit test framework says tests were successful against a container image, you can be sure that you will not experience a problem with the versioning of an underlying library at deployment time, for example. That’s not easy with most other technologies, and even Java WAR (Web application ARchive) files, for example, don’t include testing of the application server itself. That same Java application deployed in a Docker container will generally also include an application server like Tomcat, and the whole stack can be smoke-tested before shipping to production.

A secondary benefit of shipping applications in Docker containers is that in places where there are multiple applications that talk to each other remotely via something like an API, developers of one application can easily develop against a version of the other service that is currently tagged for the environment they require, like production or staging. Developers on each team don’t have to be experts in how the other service works or is deployed just to do development on their own application. If you expand this to a service-oriented architecture with innumerable microservices, Docker containers can be a real lifeline to developers or QA engineers who need to wade into the swamp of inter-microservice API calls.

A common practice in organizations that run Docker containers in production is for automated integration tests to pull down a versioned set of Docker containers for different services, matching the current deployed versions. The new service can then be integration-tested against the very same versions it will be deployed alongside. Doing this in a heterogeneous language environment would previously have required a lot of custom tooling, but it becomes reasonably simple to implement because of the standardization provided by Docker containers.

Packaging

Docker produces what for all intents and purposes is a single artifact from each build. No matter which language your application is written in or which distribution of Linux you run it on, you get a multilayered Docker image as the result of your build. And it is all built and handled by the Docker tooling. That’s the shipping container metaphor that Docker is named for: a single, transportable unit that universal tooling can handle, regardless of what it contains. Like the container port or multimodal shipping hub, your Docker tooling will only ever have to deal with one kind of package: the Docker image. That’s powerful, because it’s a huge facilitator of tooling reuse between applications, and it means that someone else’s off-the-shelf tools will work with your build images.

Applications that traditionally take a lot of custom configuration to deploy onto a new host or development system become totally portable with Docker. Once a container is built, it can easily be deployed on any system with a running Docker server.

Deploying

Deployments are handled by so many kinds of tools in different shops that it would be impossible to list them here. Some of these tools include shell scripting, Capistrano, Fabric, Ansible, and in-house custom tooling. In our experience with multi-team organizations, there are usually one or two people on each team who know the magical incantation to get deployments to work. When something goes wrong, the team is dependent on them to get it running again. As you probably expect by now, Docker makes most of that a nonissue. The built-in tooling supports a simple, one-line deployment strategy to get a build onto a host and up and running. The standard Docker client handles deploying only to a single host at a time, but there are a large array of tools available that make it easy to deploy into a cluster of Docker hosts. Because of the standardization Docker provides, your build can be deployed into any of these systems, with low complexity on the part of the development teams.

The Docker Ecosystem

Over the years, a wide community has formed around Docker, driven by both developers and system administrators. Like the DevOps movement, this has facilitated better tools by applying code to operations problems. Where there are gaps in the tooling provided by Docker, other companies and individuals have stepped up to the plate. Many of these tools are also open source. That means they are expandable and can be modified by any other company to fit their needs.

Note

Docker is a commercial company that has contributed much of the core Docker source code to the open source community. Companies are strongly encouraged to join the community and contribute back to the open source efforts. If you are looking for supported versions of the core Docker tools, you can find out more about its offerings on the Docker website.

Orchestration

The first important category of tools that adds functionality to the core Docker distribution contains orchestration and mass deployment tools. Mass deployment tools like New Relic’s Centurion, Spotify’s Helios, and the Ansible Docker tooling still work largely like traditional deployment tools but leverage the container as the distribution artifact. They take a fairly simple, easy-to-implement approach. You get a lot of the benefits of Docker without much complexity.

Fully automatic schedulers like Apache Mesos—when combined with a scheduler like Singularity, Aurora, Marathon, or Google’s Kubernetes—are more powerful options that take nearly complete control of a pool of hosts on your behalf. Other commercial entries are widely available, such as HashiCorp’s Nomad, CoreOS’s Tectonic, Mesosphere’s DCOS, and Rancher.1 The ecosystems of both free and commercial options continue to grow rapidly.

Atomic hosts

One additional idea that you can leverage to enhance your Docker experience is atomic hosts. Traditionally, servers and virtual machines are systems that an organization will carefully assemble, configure, and maintain to provide a wide variety of functionality that supports a broad range of usage patterns. Updates must often be applied via nonatomic operations, and there are many ways in which host configurations can diverge and introduce unexpected behavior into the system. Most running systems are patched and updated in place in today’s world. Conversely, in the world of software deployments, most people deploy an entire copy of their application, rather than trying to apply patches to a running system. Part of the appeal of containers is that they help make applications even more atomic than traditional deployment models.

What if you could extend that core container pattern all the way down into the operating system? Instead of relying on configuration management to try to update, patch, and coalesce changes to your OS components, what if you could simply pull down a new, thin OS image and reboot the server? And then if something breaks, easily roll back to the exact image you were previously using?

This is one of the core ideas behind Linux-based atomic host distributions, like Red Hat’s CoreOS and Red Hat’s original Project Atomic. Not only should you be able to easily tear down and redeploy your applications, but the same philosophy should apply for the whole software stack. This pattern helps provide very high levels of consistency and resilience to the whole stack.

Some of the typical characteristics of an atomic host are a minimal footprint, a design focused on supporting Linux containers and Docker, and atomic OS updates and rollbacks that can easily be controlled via multihost orchestration tools on both bare-metal and common virtualization platforms.

In Chapter 3, we will discuss how you can easily use atomic hosts in your development process. If you are also using atomic hosts as deployment targets, this process creates a previously unheard of amount of software stack symmetry between your development and production environments.

Additional tools

Docker is not just a standalone solution. It has a massive feature set, but there is always a case where someone needs more than it can deliver. There is a wide ecosystem of tools to either improve or augment Docker’s functionality. Some good production tools leverage the Docker API, like Prometheus for monitoring, or Ansible or Spotify’s Helios for orchestration. Others leverage Docker’s plug-in architecture. Plug-ins are executable programs that conform to a specification for receiving and returning data to Docker. Some examples include Rancher’s Convoy plug-in for managing persistent volumes on Amazon EBS volumes or over NFS mounts, Weaveworks’ Weave Net network overlay, and Microsoft’s Azure File Service plug-in.

There are many more good tools that either talk to the API or run as plug-ins. Many plug-ins have sprung up to make life with Docker easier on the various cloud providers. These really help with seamless integration between Docker and the cloud. As the community continues to innovate, the ecosystem continues to grow. There are new solutions and tools available in this space on an ongoing basis. If you find you are struggling with something in your environment, look to the ecosystem!

Wrap-Up

There you have it: a quick tour through Docker. We’ll return to this discussion later on with a slightly deeper dive into the architecture of Docker, more examples of how to use the community tooling, and an exploration of some of the thinking behind designing robust container platforms. But you’re probably itching to try it all out, so in the next chapter we’ll get Docker installed and running.

1 Some of these commercial offerings have free editions of their platforms.