Chapter 10. Docker at Scale

One of Docker’s major strengths is its ability to abstract away the underlying hardware and operating system so that your application is not constrained to any particular host or environment. It facilitates scaling a stateless application not just horizontally within your data center, but also across cloud providers without many of the traditional barriers you would encounter. True to the shipping container metaphor, a container on one cloud looks like a container on another.

Many organizations find turnkey cloud deployments of Docker appealing because they can gain many of the immediate benefits of a scalable container-based platform without needing to completely build something in-house. Even though this is true, the barrier is actually pretty low for building your own platform in the cloud or in your own data center, and we’ll cover some options for doing that shortly.

The major public cloud providers have all worked to support Linux containers natively in their offerings. Some of the biggest efforts to implement Docker containers in the public cloud include:

Even cloud providers running on non-Linux operating systems like SmartOS and Windows are actively supporting the Docker ecosystem:

-

Azure Container Service (Azure supports both Windows and Linux operating systems)

It’s trivial to install Docker on a Linux instance in one of the public clouds. But getting Docker onto the server is usually just one step in the creation of a full production environment. You could do this completely on your own, or you could avail yourself of the many tools available from the major cloud providers, Docker, Inc., and the Docker community. Much of the tooling will work equally well in either a public cloud or your own data center.

A first step using built-in tooling might be to leverage Docker Engine’s Swarm mode to deploy containers easily across a large pool of Docker hosts. If you want to start with something even simpler, you could also try some of the deployment-oriented community tools like Ansible’s Docker tooling, New Relic’s Centurion, or Spotify’s Helios to quickly facilitate multihost container deployment without all the complexity of a full-blown scheduler.

In the realm of schedulers and more complex tooling systems, we are spoiled for choice with systems that replicate much of the functionality you would get from a public cloud provider, including Kubernetes, DC/OS Community Edition, and a standard Mesos cluster, as we discussed in the last chapter. Even if you run in a public cloud, there are some compelling reasons for why you might choose to run your own Docker environment rather than use one of the off-the-shelf offerings.

In this chapter, we’ll cover some options for running Docker at scale, first going through some of the simpler tools like Centurion and Docker Swarm mode, and then diving into some more advanced tools like Kubernetes and Amazon Elastic Container Service (ECS) with Fargate. All of these examples should give you a view of how you can leverage Docker to provide an incredibly flexible platform for your application workloads.

Centurion

Centurion is one of many tools that enables repeatable deployment of applications to a group of hosts. While most scheduler platforms treat the cluster as a single machine, you instead tell Centurion about each individual host that you want it to know about. Its focus is on simplifying and guaranteeing the repeatability of zero-down-time deployments with containers. Centurion does not do much more than manage your container deployment in a reliable manner, and this makes it very easy to get started with. It assumes that a load balancer sits in front of your application instances. Centurion is an easy first step in moving from traditional deployments to a Docker workflow and is a great option for people who aren’t ready for, or simply don’t need, the features of Swarm, Kubernetes, or Mesos.

Note

We could equally be covering Spotify’s Helios here, but we believe that Centurion is the simplest of these tools to get up and running. We encourage you to see if there are tools that are a better fit for your deployment needs, but this section should give you a taste of what you might achieve as a first step.

Let’s look at deploying a simple application with Centurion. Here you’ll deploy the public adejonge/helloworld container as your web application. It won’t do much more than serve up a welcome page that you can see in a browser. You could easily switch in your custom application. The only requirement is that it be deployed to a registry.

Before you can deploy, you have to satisfy the dependencies for the tool and get it installed. Centurion depends on the Docker command-line tool and requires that you have Ruby 2.0 or higher, so you’ll want to make sure you have a system with these installed. Centurion is known to run well on Linux or macOS. It can conceivably run on Windows, but this is untested by the package maintainers. Ruby runtime packages are available via yum, dnf, apk, and apt-get on all popular Linux distributions. Generally, any distribution with a kernel new enough to run Docker will ship with packages that meet this requirement. On recent macOS versions, you will already have the right version of Ruby. If you are on an older release, you can install a recent Ruby with Homebrew—which we installed in Chapter 3. Most Linux distributions that are capable of running Docker also ship with a modern enough Ruby to run Centurion. You can check to see if you have Ruby installed, and if you have a version new enough, like this:

$ ruby -v ruby 2.4.2p198 (2017-09-14 revision 59899) [x86_64-darwin17]

Here, we have Ruby 2.4.2, which is plenty recent. Once you have Ruby running, install Centurion with the Ruby package manager:

$ gem install centurion Fetching: trollop-2.1.2.gem (100%) Successfully installed trollop-2.1.2 ... Parsing documentation for centurion-1.9.0 Installing ri documentation for centurion-1.9.0 Done installing documentation for trollop, excon, logger-colors, net-ssh, net-scp, sshkit, centurion after 5 seconds 7 gems installed

You can now invoke centurion from the command line to make sure it’s available:

$ centurion --help Options: -p, --project=<s> project (blog, forums...) -e, --environment=<s> environment (production, staging...) -a, --action=<s> action (deploy, list...) (default: list) -i, --image=<s> image (yourco/project...) -t, --tag=<s> tag (latest...) -h, --hosts=<s> hosts, comma separated -d, --docker-path=<s> path to docker executable (default: docker) -n, --no-pull Skip the pull_image step --registry-user=<s> user for registry auth --registry-password=<s> password for registry auth -o, --override-env=<s> override environment variables, comma separated -l, --help Show this message

There are a lot of options there, but right now you’re just making sure that it’s installed and working. If Centurion is not yet available and you get an error, then you can add it to your path like so:

$ gempath=`gem environment | grep '\- INSTALLATION DIRECTORY' | awk '{print $4}'`

$ export PATH=$gempath/bin:$PATH

You should now be able to invoke centurion --help and see the output of the help.

To begin with, you’ll just make a directory in which you’ll store the Centurion configuration. If this were your own custom application, this might be the application’s directory, or it might be a directory in which you store all the deployment configs for all of your applications. We encourage the latter for larger installations because it facilitates conversations between teams about the deployment configuration, and helps promote good patterns between teams. Since you’re just going to deploy the public adejonge/helloworld container, let’s create a temporary directory to house the configs. Then you’ll change directories into it and tell Centurion to scaffold a basic config for you with the centurionize tool:

$ cd /tmp $ mkdir helloworld $ cd helloworld $ gem install bundle ... Done installing documentation for bundler, bundle after 4 seconds 2 gems installed $ centurionize -p helloworld Creating /tmp/helloworld/config/centurion Writing example config to /tmp/helloworld/config/centurion/helloworld.rake Writing new Gemfile to /Users/skane/tmp/helloworld/Gemfile Adding Centurion to the Gemfile Remember to run `bundle install` before running Centurion Done!

We can ignore the Gemfile for now and just open the config it generated for us in config/centurion/helloworld.rake. You might take a look at it to see what it put in place in order to get an idea of what Centurion can do. The scaffolded config contains examples of how to use many of Centurion’s features. We’ll just edit it down to the basics we care about:

namespace:environmentdodesc'Development environment'task:developmentdoset_current_environment(:development)set:image,'adejonge/helloworld'env_varsMY_ENV_VAR:'something important'host_port8080,container_port:8080host'192.168.2.10'host'192.168.2.25'endend

Note

It is important that you edit the host lines to match the hostnames or IP addresses for your Docker servers; otherwise, it won’t deploy anything! In theory, you can get Centurion working with Docker Community Edition for Mac and Windows, but at the moment, it is not straightforward or recommended.

There are two ways to use this. As is, it will require that you have Docker’s API open over the network so that Centurion can connect. Unless you’ve already got that secured, you probably want to use it over SSH instead. If you have a user who can use the Docker command locally on your servers, you can make Centurion SSH into your hosts to deploy your containers instead of requiring an exposed port. To enable this feature, simply, add something like this to the task in your Rakefile.

# Add on the line after 'set_current_environment(:development)'ssh_user=ENV['USER']puts"[Info] Will SSH using:#{ssh_user}"set:ssh,trueset:ssh_user,ssh_userset:ssh_log_level,Logger::WARN

If you are going to use SSH, you’ll want to add the required private keys to a local SSH agent so that you avoid any password prompts.

Centurion supports multiple environments in the same config. Here you’re just going to deploy to development. You could add as many environments as you like. The default file also uses a pattern where common configurations among environments are put into a common section that is called by each environment. For demonstration purposes, we’ve cut this config down to a bare minimum.

You now have a config that will let you deploy the adejonge/helloworld image from the public registry to two hosts, while setting the environment variable MY_ENV_VAR and mapping port 8080 inside the container to port 8080 of the server. Centurion supports any number of environment variables, hosts, ports, or volume mounts. The idea is to store a repeatable configuration for your application that can be stamped out onto as many Docker hosts as needed.

Centurion supports a rolling deployment model out of the box for web applications. It will cycle through a set of hosts, taking one container down at a time to help ensure that your application stays available throughout the deployment. It uses a defined health-check endpoint on a container to enable rolling deployments, health-checking each container as it comes up and not moving on to the next host until it has been successful. By default, this endpoint is set to “/” and that’s good enough for our simple welcome page application. Nearly all of this is configurable, but we’ll keep it simple for this demonstration. Once you’re more familiar with the tool, you should go back to the README to read about all of the other options.

You’re now ready to deploy this to your development environment. You are going to tell Centurion to use the helloworld project, use the development environment, and do a web application zero-downtime deployment with rolling_deploy. Centurion will initiate a docker pull on the hosts in parallel; then, on each host in turn, it will create a new container, tear down the old one, and start up the new one. We’ll cut down the very verbose output to get a clearer idea of the process:

$ centurion -p helloworld -e development -a rolling_deploy ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Fetching image adejonge/helloworld:latest IN PARALLEL I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Using CLI to pull I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Using CLI to pull latest: Pulling from adejonge/helloworld ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : ----- Connecting to Docker on 192.168.2.10 ----- ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : ----- Connecting to Docker on 192.168.2.10 ----- I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Image sha256:4 found on 192.168.2.10 ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : ----- Connecting to Docker on 192.168.2.10 ----- I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Looking for containers listening on port 8080 I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Stopping container(s): [] I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Creating new container for adejonge/helloworld:latest I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Starting new container 965f0947 I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Inspecting new container 965f0947: ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Waiting for the port to come up I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Found container up for 0 seconds I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Container is up! ... I, [... #22324] INFO -- : ----- Connecting to Docker on 192.168.2.20 ----- I, [... #22324] INFO -- : Service name helloworld

Here you can see Centurion pulling the requested image; verifying that it pulled properly; and then connecting to the hosts to stop the old container, create a new one, start it up, and then continuously health-check it until it reports back that it is healthy. At the very end, it cleans up the old containers so that they don’t hang around forever.

Now your application is up and running on both of your servers. You can connect to it with a web browser by hitting the IP address of either server on port 8080.

http://192.168.2.20:8080/

If everything is working correctly, you should see the simple message Hello World from Go in minimal Docker container in your web browser.

In real production, you’ll want a load balancer configured to sit in front of these hosts and redirect your clients to either of the instances. There is nothing dynamic to the Centurion setup, but it gets your application deployed with all the basic benefits of Docker for a minimal investment of time.

That’s all there is to a very basic setup. This class of tooling is very easy to get started with and will get you to a production infrastructure quickly. But growing your Docker deployment to a vast scale will likely involve a distributed scheduler or one of the cloud provider’s container platforms.

In that vein, let’s take a look at Docker’s Swarm tooling and see how this built-in Docker cluster mode can bridge the gap between simple tools like Centurion and the more full-featured robust platforms like Kubernetes and Amazon Elastic Container Service.

Docker Swarm Mode

After building the container runtime in the form of the Docker engine, the engineers at Docker turned to the problems of orchestrating a fleet of individual Docker hosts and effectively packing those hosts full of containers. The first tool that evolved from this work was called Docker Swarm. As we explained early on, and rather confusingly, there are now two things called “Swarm,” both of which come from Docker, Inc.

The original standalone Docker Swarm is officially Docker Swarm, but there is a second “Swarm,” which is more specifically called Swarm mode. This is actually built into the Docker Engine. The built-in Swarm mode is a lot more capable than the original Docker Swarm and is intended to replace it entirely. Swarm mode has the major advantage of not requiring you to install anything separately. You already have this on your Docker box! This is the Docker Swarm we’ll focus on here. Hopefully now that you know there are two different Docker Swarms, you won’t get confused by contradictory information on the internet.

The idea behind Docker Swarm is to present a single interface to the docker client tool, but have that interface be backed by a whole cluster rather than a single Docker daemon. Swarm is primarily aimed at managing clustered computing resources via the Docker tools. It has grown a lot since its first release and now contains several scheduler plug-ins with different strategies for assigning containers to hosts, and with basic service discovery built in. But it remains only one building block of a more complex solution. Docker has also added native support for deploying containers to Kubernetes into some Docker clients,1 which means that for some situations it is possible to start with a simpler solution like Swarm and then graduate to Kubernetes without needing to change as many of the tools that users rely on.

Swarm clusters can contain one or more managers that act as the central management hub for your Docker cluster. It is best to set up an odd number of managers. Only one manager will act as the cluster leader at a time. As you add more nodes to Swarm, you are merging them into a single, cohesive cluster that can be easily controlled with the Docker tooling.

Let’s get a Swarm cluster up and running. To start, you will need three or more Linux servers that can talk to each other over the network. Each of these servers should be running recent releases of Docker Community Edition from the official Docker software repositories.

Tip

Refer to Chapter 3 for details on installing the docker-ce packages on Linux.

For this example, we will use three Ubuntu servers running docker-ce. The very first thing you’ll need to do is ssh to the server that you want to use as the Swarm manager and then run the swarm init command using the IP address for your Swarm manager.

$ ssh 172.17.4.1

...

ubuntu@172.17.4.1:$ sudo docker swarm init --advertise-addr 172.17.4.1

Swarm initialized: current node (hypysglii5syybd2zew6ovuwq) is now a manager.

To add a worker to this swarm, run the following command:

docker swarm join --token SWMTKN-1-14......a4o55z01zq 172.17.4.1:2377

To add a manager to this swarm, run 'docker swarm join-token manager' and follow

the instructions.

Warning

In many of this chapter’s examples, it’s important that you use the correct IP addresses for your manager and worker nodes.

This step will initialize the Swarm manager and give you the token that is required for nodes that want to join the cluster. Make note of this token somewhere safe, like a password manager. Don’t worry too much if you lose this token; you can always get it again by running the following command on the manager:

sudo docker swarm join-token --quiet worker

You can inspect your progress so far by running your local docker client pointed at the new manager node’s IP address.

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 info ... Swarm: active NodeID: usjngewgh5syybd2ws6ovqwe Is Manager: true ClusterID: k2ujqs3vf8l1f31qx5fh2pouh Managers: 1 Nodes: 1 Orchestration: Task History Retention Limit: 5 Raft: Snapshot Interval: 10000 Number of Old Snapshots to Retain: 0 Heartbeat Tick: 1 Election Tick: 3 Dispatcher: Heartbeat Period: 5 seconds CA Configuration: Expiry Duration: 3 months Force Rotate: 0 Autolock Managers: false Root Rotation In Progress: false Node Address: 172.17.4.1 Manager Addresses: 172.17.4.1:2377 ...

You can also list all of the nodes that are currently in the cluster with the following command:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 node ls ID HOSTNAME STATUS AVAILABILITY MANAGER STATUS hyp... * ip-172-17-4-1 Ready Active Leader

At this point, you can add the two additional servers as workers to the Swarm cluster. This is what you’d do in production if you were going to scale up, and Swarm makes this pretty easy.

$ ssh 172.17.4.2 \

"sudo docker swarm join --token SWMTKN-1-14......a4o55z01zq 172.17.4.1:2377"

This node joined a swarm as a worker.

$ ssh 172.17.4.3 \

"sudo docker swarm join --token SWMTKN-1-14......a4o55z01zq 172.17.4.1:2377"

This node joined a swarm as a worker.

If you rerun docker node ls you should now see that you have a total of three nodes in your cluster, and only one of them is marked as the Leader.

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 node ls ID HOSTNAME STATUS AVAILABILITY MANAGER STATUS hyp... * ip-172-17-4-1 Ready Active Leader qwe... ip-172-17-4-2 Ready Active poi... ip-172-17-4-3 Ready Active

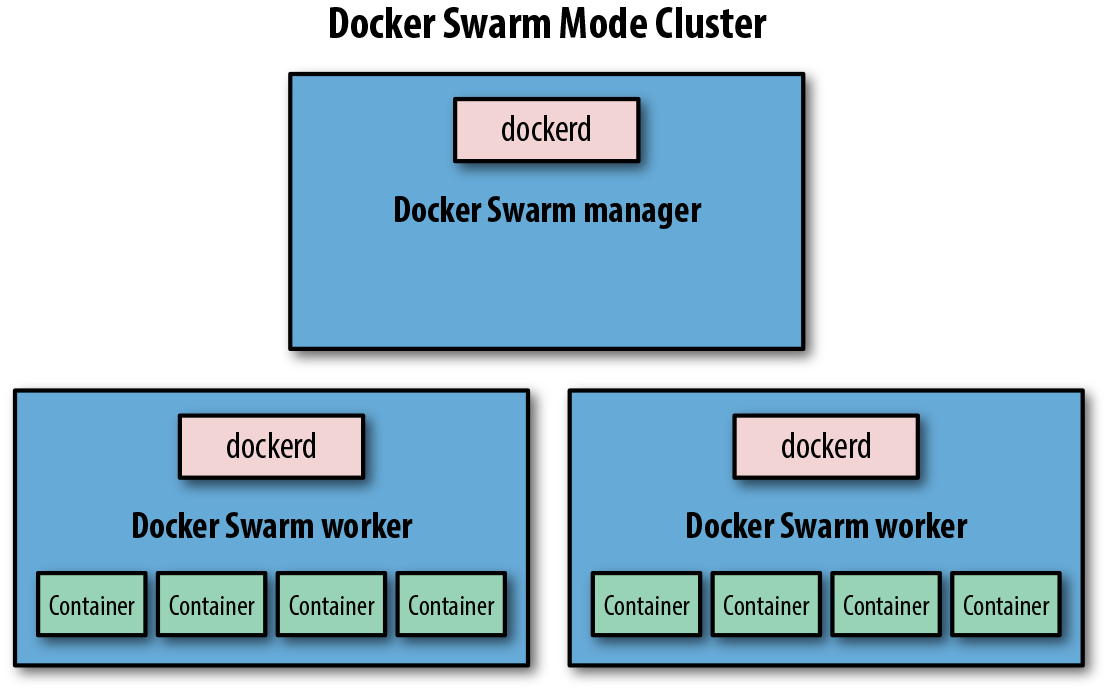

This is all that’s required to get a Swarm cluster up and running in Swarm mode (Figure 10-1)!

Figure 10-1. Simple Docker Swarm Mode cluster

The next thing you should do is create a default network for your services to use. Again, it’s pretty simple to do that:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 network create --driver=overlay default-net ckwh5ph4ksthvx6843ytrl5ik

Up to this point, we’ve just been getting the underlying pieces running, and so far we haven’t deployed any real business logic. So let’s launch your first service into the cluster. You can do that with a command like this:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service create --detach=true --name quantum \

--replicas 2 --publish published=80,target=8080 --network default-net \

spkane/quantum-game:latest

tiwtsbf270mh83032kuhwv07c

The service we’re launching with starts containers that host the Quantum web game. This is a browser-based puzzle game that uses real quantum mechanics. We hope that this is a more interesting example than another Hello World!

Warning

Although we’re using the latest tag in many of these examples, it is important that you don’t use this tag in production. It is convenient for the book, since we can easily push out updates to the code, but this tag floats and cannot be pinned to a specific release over a long period of time. That means if you use latest, then your deployments are not repeatable! It can also easily lead to a situation where you don’t have the same version of an application running on all the servers.

Let’s now see where those containers ended up, by running docker service ps against the service name you created:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ps quantum ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE ... v... quantum.1 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-2 Running Running 56 seconds ago u... quantum.2 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-3 Running Running 56 seconds ago

Swarm mode uses a routing mesh between the nodes to automatically route traffic to a container that can serve the request. When you specify a published port in the docker service create command, the mesh makes it possible to hit this port on any of your three nodes and will route you to the web application. Notice that we said any of the three nodes even though you only have two instances running. Traditionally, you would have had to also set up a separate reverse proxy layer to accomplish this, but its batteries are included with Swarm mode.

To prove it, you can test the service now by pointing a web browser to the IP address of any of your nodes.

http://172.17.4.1/

If everything is working as expected, you the splash screen for “The Quantum Game” will greet you, quickly followed by the puzzle board.

Here we only have one instance running, but you would probably have a number of instances in a real-world scenario. To get a list of all the services, we can use service ls:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ls ID NAME MODE REPLICAS IMAGE PORTS tn... quantum replicated 2/2 spkane/quantum-game:latest *:80->8080/tcp

This gives us a summary view with the most commonly needed information, but sometimes that’s not enough. Docker maintains a lot of other metatadata about services, just like it does for containers. Mimicking the Docker CLI, we can get detailed information about a service with service inspect:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service inspect --pretty quantum ID: tn5075th07tuncwqa4po4a514 Name: quantum Service Mode: Replicated Replicas: 2 Placement: UpdateConfig: Parallelism: 1 On failure: pause Monitoring Period: 5s Max failure ratio: 0 Update order: stop-first RollbackConfig: Parallelism: 1 On failure: pause Monitoring Period: 5s Max failure ratio: 0 Rollback order: stop-first ContainerSpec: Image: spkane/quantum-game:latest@sha256:257286d3126622397f... Resources: Networks: default-net Endpoint Mode: vip Ports: PublishedPort = 80 Protocol = tcp TargetPort = 8080 PublishMode = ingress

There is a lot of info here, so let’s point out some of the more important things. First we can see that this is a replicated service with two replicas, just like we saw in the service ls command. We can also see that Docker is health-checking the service at five-second intervals. Running an update to the service will use the stop-first method, which means it will take our service first to N−1 and then spin up a new instance to take us back to N. You might want to always run in N+1 mode so that you are never down a node during updates in production. You can change that with the --update-order=start-first option to the service update command. It will exhibit the same behavior in a rollback scenario, and we can likewise change that with --rollback-order=start-first.

In a real-world scenario, we need to be able to not only launch our service but also to scale it up and down. It would be a shame if we had to redeploy it to do that, not to mention it could introduce any number of issues. Luckily, Swarm makes it easy to scale our services with a single command. To double the number of instances you have running from two to four, you can simply run this:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service scale --detach=false quantum=4 quantum scaled to 4 overall progress: 4 out of 4 tasks 1/4: running [==================================================>] 2/4: running [==================================================>] 3/4: running [==================================================>] 4/4: running [==================================================>] verify: Service converged

Note

We used --detach=false in the previous command so that it was easier to see what was happening.

We can now use service ps to show us that Swarm did what we asked. This is the same command we ran earlier, but now we should have more copies running! But wait, didn’t we ask for more copies than we have nodes?

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ps quantum ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE ... v... quantum.1 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-2 Running Running 56 seconds ago u... quantum.2 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-3 Running Running 56 seconds ago e... quantum.3 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 2 minutes ago q... quantum.4 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 2 minutes ago

You’ll notice that you have two services running on the same host. Did you expect that? This may not be ideal for host resiliency, but by default Swarm will prioritize ensuring that you have the number of instances that you requested over spreading individual containers across hosts when possible. If you don’t have enough nodes, you will get multiple copies on each node. In a real-world scenario, you need to think carefully about placement and scaling. You might not be able to get away with running multiple copies on the same host in the event that you lose a whole node. Would your application still serve users at that reduced scale?

When you need to deploy a new release of your software, you will want to use the docker service update command. There are a lot of options to this command, but here’s one example:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service update --update-delay 10s \

--update-failure-action rollback --update-monitor 5s \

--update-order start-first --update-parallelism 1 \

--detach=false \

--image spkane/quantum-game:latest-plus quantum

quantum

overall progress: 4 out of 4 tasks

1/4: running [==================================================>]

2/4: running [==================================================>]

3/4: running [==================================================>]

4/4: running [==================================================>]

verify: Service converged

Running this command will cause Swarm to update your service one container at a time, pausing in between each update. Great, but what if something were to go wrong? We might need to deploy a previous release to get back to working order. You could now roll back to the previous version with the service rollback command, which we discussed in passing a little bit earlier:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service rollback quantum quantum rollback: manually requested rollback overall progress: rolling back update: 4 out of 4 tasks 1/4: running [> ] 2/4: running [> ] 3/4: running [> ] 4/4: running [> ] verify: Service converged

That’s about as nice a rollback mechanism as you could ask for. You don’t have to keep track of the previous version; Docker does that for you. All you need to do is tell it to roll back and it pulls the previous metadata out of its internal storage and performs the rollback. Note that just like during deployment, it can health-check your nodes to make sure the rollback is working successfully.

So, what happens if one of your servers is experiencing an issue and you need to take it offline? In this case, you can easily drain all the services off of a single node by using the --availability option to the docker node update command.

Let’s take a look at the nodes that you have in the cluster again:

docker -H 172.17.4.1 node ls ID HOSTNAME STATUS AVAILABILITY MANAGER STATUS hyp... * ip-172-17-4-1 Ready Active Leader qwe... ip-172-17-4-2 Ready Active poi... ip-172-17-4-3 Ready Active

Let’s also check where our containers are currently running:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ps -f "desired-state=running" quantum ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE ... f... quantum.1 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 6 minutes ago 7... quantum.2 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 6 minutes ago r... quantum.3 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-2 Running Running 6 minutes ago 6... quantum.4 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-3 Running Running 6 minutes ago

Tip

In the previous command, we used a filter so that the output showed only the currently running processes. By default, Docker will also show you the previous containers that were running in a tree format, so that you can see things like updates and rollbacks in the output.

If you have determined that the server at 172.17.4.3 is in need of downtime, you could drain the tasks of that node and move them to another host by modifying the availability state to drain in Swarm:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 node update --availability drain ip-172-17-4-3 ip-172-17-4-3

If we inspect the node, we can see that the availability is now set to drain.

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 node inspect --pretty ip-172-17-4-3 ID: l9j10ijs5e4843iwghjsplqae Hostname: ip-172-17-4-3 Joined at: 2018-03-11 18:57:17.663732624 +0000 utc Status: State: Ready Availability: Drain Address: 172.17.4.3 Platform: Operating System: linux Architecture: x86_64 Resources: CPUs: 2 Memory: 7.797GiB Plugins: Log: awslogs, fluentd, gcplogs, gelf, journald, json-file, ... Network: bridge, host, macvlan, null, overlay Volume: local Engine Version: 17.12.1-ce TLS Info: TrustRoot: ... Issuer Subject: ... Issuer Public Key: ...

You might be wondering what effect that has on the service. We told one of the nodes to stop running copies of the service, and they either have to go away or migrate somewhere else. What did it do? We can look at the details of our service again and see that all the running containers on that host have been moved to a different node.

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ps -f "desired-state=running" quantum ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE ... f... quantum.1 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 19 minutes ago 7... quantum.2 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-1 Running Running 19 minutes ago r... quantum.3 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-2 Running Running 19 minutes ago 4... quantum.4 spkane/... ip-172-17-4-2 Running Running 5 minutes ago

At this point, it is safe to bring down the node and do whatever work is required to make it healthy again. When you are ready to add the node back into the Swarm cluster, you can do so by running:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 node update --availability active ip-172-17-4-3 ip-172-17-4-3

We’ll spare you from reinspecting the node at the moment, but you can always rerun the node inspect command if you want to see what this looks like.

Warning

When you add a node back to the cluster, containers will not automatically balance! However, a new deploy or update should result in the containers being evenly spread across the nodes.

Once you are done, you can remove your service with the following command:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service rm quantum quantum

and then verify that it is indeed completely gone:

$ docker -H 172.17.4.1 service ps quantum no such service: quantum

That’s all for now! At this point, you can safely tear down all of the servers that were a part of your Swarm cluster if you no longer need them.

That was kind of a whirlwind tour, but covers the basics of using Swarm mode in Docker Engine and should help get you started building your own Docker cluster for deployment.

Amazon ECS and Fargate

One of the most popular cloud providers is Amazon via their AWS offering. Support for running containers natively has existed in Elastic Beanstalk since mid-2014. But that service assigns only a single container to an Amazon instance, which means that it’s not ideal for short-lived or lightweight containers. EC2 itself is a great platform for hosting your own Docker environment, though, and because Docker is powerful, you don’t necessarily need much on top of your instances to make this a productive environment to work in. But Amazon has spent a lot of engineering time building a service that treats containers as first-class citizens: the Elastic Container Service (ECS). In the last few years they have built upon this support with products like the ECS for Kubernetes (EKS) and, more recently, Fargate.

Note

Fargate is simply a marketing label Amazon uses for the new feature of ECS that makes it possible for AWS to automatically manage all the nodes in your container cluster so that you can focus on deploying your service.

The Elastic Container Service is a set of tools that coordinates several AWS components. With ECS, you have a choice of whether or not you will run the Fargate tooling on top. If you do, then you don’t need to handle as much of the work. If you don’t, then in addition to the cluster nodes to handle your workload you will also need to add one or more EC2 instances to the cluster running Docker and Amazon’s special ECS agent. If you run Fargate, then the cluster is automatically managed for you. In either case, you spin up the cluster and then push your containers into it.

The Amazon ECS agent we just mentioned works with the ECS service to coordinate your cluster and schedule containers to your hosts. You will only be directly exposed to this when you manage a traditional non-Fargate ECS cluster.

Core AWS Setup

The rest of this section assumes that you have access to an AWS account and some familiarity with the service. You can learn about pricing and create a new account at aws.amazon.com/free/. Amazon offers a free service tier, which may be enough for you to experiment with if you don’t already have a paid account. After you have your AWS account set up, you will need at least one administrative user, a key pair, a virtual private cloud (VPC), and a default security group in your environment. If you do not already have these set up, follow the directions in the Amazon documentation.

IAM Role Setup

AWS’s Identity and Access Management (IAM) roles are used to control what actions a user can take within your cloud environment. We need to make sure we can grant access to the right actions before moving on with the Elastic Container Service.

To work with the ECS, you need to create a role called ecsInstanceRole that has the AmazonEC2ContainerServiceforEC2Role managed role attached to it. The easiest way to do this is by logging into the AWS console and then navigating to Identity and Access Management.

Tip

Check to ensure that you don’t already have the proper role. If it already exists, then you should double-check that it is set up properly, as these directions have changed a bit over the years.

-

In the left sidebar, click Roles.

-

Then, click the “Create role” button.

-

Under AWS Service, select Elastic Container Service.

-

Under “Select your use case,” select Elastic Container Service.

-

Click Next: Permissions.

-

Click Next: Review.

-

In Role Name, type:

ecsInstanceRole. -

Click “Create role.”

If you are interested in storing container configuration in an S3 object storage bucket, take a look at the Amazon ECS Container Agent Configuration documentation.

AWS CLI Setup

Amazon supplies command-line tools that make it easy to work with their API-driven infrastructure. You will need to install a very recent version of the AWS command-line interface (CLI) tools. Amazon has detailed documentation that covers installation of their tools, but the basic steps are as follows.

Installation

Here we’ll cover installation on a few different OSes. You can feel free to skip to the one you care about. If you’re curious or just like installation instructions, by all means read them all!

- macOS

-

In Chapter 3, we discussed installing Homebrew. If you previously did this, you can install the AWS CLI using the following commands:

$ brew update $ brew install awscli

- Windows

-

Amazon provides a standard MSI installer for Windows, which can be downloaded from Amazon S3 for your architecture:

- Other

-

The Amazon CLI tools are written in Python. So on most platforms, you can install the tools with the Python

pippackage manager by running the following from a shell:$ pip install awscli --upgrade --user

Some platforms won’t have pip installed by default. In that case, you can use the easy_install package manager, like this:

$ easy_install awscli

Configuration

Quickly verify that your AWS CLI version is at least 1.7.0 with the following command:

$ aws --version aws-cli/1.14.50 Python/3.6.4 Darwin/17.3.0 botocore/1.9.3

To configure the AWS CLI tool, ensure that you have access to your AWS access key ID and AWS secret access key, and then run the configure command. You will be prompted for your authentication information and some preferred defaults:

$ aws configure AWS Access Key ID [None]: EXAMPLEEXAMPLEEXAMPLE AWS Secret Access Key [None]: ExaMPleKEy/7EXAMPL3/EXaMPLeEXAMPLEKEY Default region name [None]: us-east-1 Default output format [None]: json

At this point, it’s a really good idea to test that the CLI tools are working correctly before proceeding. We can easily do that by running the following command to list the IAM users in your account:

$ aws iam list-users

Assuming everything went according to plan and you chose JSON as your default output format, you should get something like this:

{"Users":[{"Path":"/","UserName":"administrator","UserId":"ExmaPL3ExmaPL3ExmaPL3Ex","Arn":"arn:aws:iam::936262807352:user/myuser","CreateDate":"2017-12-14T19:33:23Z"}]}

Container Instances

The first thing you need to do after installing the required tools is to create at least a single cluster that your Docker hosts will register with when they are brought online.

Note

The default cluster name is imaginatively named “default.” If you keep this name, you do not need to specify --cluster-name in many of the commands that follow.

The first thing you need to do is create a cluster in the container service. You will then launch your tasks in the cluster once it’s up and running. For these examples, you should start by creating a cluster called fargate-testing:

$ aws ecs create-cluster --cluster-name fargate-testing

{"cluster":{"clusterArn":"arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:1...2:cluster/fargate-testing","clusterName":"fargate-testing","status":"ACTIVE","registeredContainerInstancesCount":0,"runningTasksCount":0,"pendingTasksCount":0,"activeServicesCount":0}}

Before AWS Fargate was released, you were required to create AWS EC2 instances running docker and the ecs-agent and add them into your cluster. You can still use this approach if you want (EC2 launch type), but Fargate makes it much easier to run a dynamic cluster that can scale fluidly with your workload.

Tasks

Now that our container cluster is set up, we need to start putting it to work. To do this, we need to create at least one task definition. The Amazon Elastic Container Service defines the term task definition as a list of containers grouped together.

To create your first task definition, open up your favorite editor, copy in the following JSON, and then save it as webgame-task.json in your current directory, as shown here:

{"containerDefinitions":[{"name":"web-game","image":"spkane/quantum-game","cpu":0,"portMappings":[{"containerPort":8080,"hostPort":8080,"protocol":"tcp"}],"essential":true,"environment":[],"mountPoints":[],"volumesFrom":[]}],"family":"fargate-game","networkMode":"awsvpc","volumes":[],"placementConstraints":[],"requiresCompatibilities":["FARGATE"],"cpu":"256","memory":"512"}

Tip

You can also check out these files and a few others by running:

git clone \

https://github.com/bluewhalebook/\

docker-up-and-running-2nd-edition.git

The URL above has been continued on the following line so that it fits in the margins. You may find that you need to re-assemble the URL and remove the backslashes for the command to work properly.

In this task definition, we are saying that we want to create a task family called fargate-game running a single container called web-game that is based on the Quantum web game. This Docker image launches a browser-based puzzle game that uses real quantum mechanics.

Tip

Fargate limits some of the options that you can set in this configuration, including networkMode and the cpu and memory settings. You can find more out about the options in the task definition from the official AWS documentation.

In this task definition, we define some constraints on memory and CPU usage for the container, in addition to telling Amazon whether this container is essential to the task. The essential flag is useful when you have multiple containers defined in a task, and not all of them are required for the task to be successful. If essential is true and the container fails to start, then all the containers defined in the task will be killed and the task will be marked as failed. We can also use the task definition to define almost all of the typical variables and settings that would be included in a Dockerfile or on the docker run command line.

To upload this task definition to Amazon, you will need to run a command similar to what is shown here:

$ aws ecs register-task-definition --cli-input-json file://./webgame-task.json

{"taskDefinition":{"taskDefinitionArn":"arn:aws:ecs:...:task-definition/fargate-game:1","containerDefinitions":[{"name":"web-game","image":"spkane/quantum-game","cpu":0,"portMappings":[{"containerPort":8080,"hostPort":8080,"protocol":"tcp"}],"essential":true,"environment":[],"mountPoints":[],"volumesFrom":[]}],"family":"fargate-game","networkMode":"awsvpc","revision":2,"volumes":[],"status":"ACTIVE","requiresAttributes":[{"name":"com.amazonaws.ecs.capability.docker-remote-api.1.18"},{"name":"ecs.capability.task-eni"}],"placementConstraints":[],"compatibilities":["EC2","FARGATE"],"requiresCompatibilities":["FARGATE"],"cpu":"256","memory":"512"}}

We can then list all of our task definitions by running the following:

$ aws ecs list-task-definitions

{"taskDefinitionArns":["arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:012345678912:task-definition/fargate-game:1",]}

Now you are ready to create your first task in your cluster. You do so by running a command like the one shown next. The count argument in the command allows you to define how many copies of this task you want deployed into your cluster. For this job, one is enough.

You will need to modify the following command to reference a valid subnet ID and security-group ID from your AWS VPC. You should be able to find these in the AWS console or by using the AWS CLI commands aws ec2 describe-subnets and aws ec2 describe-security-groups. You can also tell AWS to assign your tasks a public IP address by using a network configuration similar to this:

awsvpcConfiguration={subnets=[subnet-abcd1234],securityGroups=[sg-abcd1234],assignPublicIp=ENABLED}.

$ aws ecs create-service --cluster fargate-testing --service-name \

fargate-game-service --task-definition fargate-game:1 --desired-count 1 \

--launch-type "FARGATE" --network-configuration \

"awsvpcConfiguration={subnets=[subnet-abcd1234],\

securityGroups=[sg-abcd1234]}"

{"service":{"serviceArn":"arn:aws:ecs:...:service/fargate-game-service","serviceName":"fargate-game-service","clusterArn":"arn:aws:ecs:...:cluster/fargate-testing","loadBalancers":[],"status":"ACTIVE","desiredCount":1,"runningCount":0,"pendingCount":0,"launchType":"FARGATE","platformVersion":"LATEST","taskDefinition":"arn:aws:ecs:...:task-definition/fargate-game:1","deploymentConfiguration":{"maximumPercent":200,"minimumHealthyPercent":100},"deployments":[{...}],"roleArn":"arn:...role/ecs.amazonaws.com/AWSServiceRoleForECS","events":[],"createdAt":1520727776.555,"placementConstraints":[],"placementStrategy":[],"networkConfiguration":{"awsvpcConfiguration":{"subnets":["subnet-abcd1234"],"securityGroups":["sg-abcd1234"],"assignPublicIp":"DISABLED"}}}}

Tip

Fargate and the awsvpc network require that you have a service linked role for ECS. In the preceding output, you should see a line that ends like this:

"role/aws-service-role/ecs.amazonaws.com/AWSServiceRoleForECS"

Most of the time this will be autogenerated for you, but you can create it manually using the following command:

aws iam create-service-linked-role \ --aws-service-name ecs.amazonaws.com

You can now list all of the services in your cluster with the following command:

$ aws ecs list-services --cluster fargate-testing

{"serviceArns":["arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:012345678912:service/fargate-game-service"]}

To retrieve all the details about your service, run:

$ aws ecs describe-services --cluster fargate-testing \

--services fargate-game-service

{"services":[{..."deployments":[{"id":"ecs-svc/9223370516126999252","status":"PRIMARY","taskDefinition":"arn:...:task-definition/fargate-game:1","desiredCount":1,"pendingCount":1,"runningCount":0,"createdAt":1520727776.555,"updatedAt":1520727776.555,"launchType":"FARGATE","platformVersion":"1.0.0","networkConfiguration":{"awsvpcConfiguration":{"subnets":["subnet-abcd1234"],"securityGroups":["sg-abcd1234"],"assignPublicIp":"DISABLED"}}}],"roleArn":"...role/ecs.amazonaws.com/AWSServiceRoleForECS","events":[{"id":"2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801","createdAt":1520727990.202,"message":"(...game-service) has reached a steady state."}],...}],"failures":[]}

This output will tell you a lot about all the tasks in your service. In this case we have a single task, which we can see has “reached a steady state.”

Note

The task-definition value is a name followed by a number (fargate-game:1). The number is the revision. If you edit your task and reregister it with the aws ecs register-task-definition command, you will get a new revision, which means that you will want to reference that new revision in various commands like aws ecs update-service. If you don’t change that number, you will continue to launch containers using the older JSON. This versioning makes it very easy to roll back changes and test new revisions without impacting all future instances.

If you want to see what individual tasks are running in your cluster, you can run the following:

$ aws ecs list-tasks --cluster fargate-testing

{"taskArns":["arn:aws:ecs:...:task/2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801"]}

Since you only have a single task in your cluster at the moment, this list is very small. You will also notice that the task ID matches the ID for the task that is listed in “a steady state” in your service.

To get more details about the individual task, you can run the following command after substituting the task ID with the correct one from your cluster:

$ aws ecs describe-tasks --cluster fargate-testing \ --task 2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801

{"tasks":[{"taskArn":"arn:aws:...:task/2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801","clusterArn":"arn:aws:ecs:...:cluster/fargate-testing","taskDefinitionArn":"arn:aws:...:task-definition/fargate-game:1","overrides":{"containerOverrides":[{"name":"web-game"}]},"lastStatus":"RUNNING","desiredStatus":"RUNNING","cpu":"256","memory":"512","containers":[{..."name":"web-game","lastStatus":"RUNNING","networkBindings":[],"networkInterfaces":[{"attachmentId":"a0d40aec-...-0c4086ed10d7","privateIpv4Address":"10.11.6.240"}]}],"startedBy":"ecs-svc/9223370516124771373","version":4,"connectivity":"CONNECTED",..."group":"service:fargate-game-service","launchType":"FARGATE","platformVersion":"1.0.0","attachments":[{"id":"a0d40aec-3469-4eb0-8bd3-0c4086ed10d7","type":"ElasticNetworkInterface","status":"ATTACHED","details":[{"name":"subnetId","value":"subnet-abcd1234"},{"name":"networkInterfaceId","value":"eni-abcd1234"},{"name":"macAddress","value":"0f:c7:7d:ac:d1:ff"},{"name":"privateIPv4Address","value":"10.4.0.100"}]}]}],"failures":[]}

If you notice that the lastStatus key is displaying a value of PENDING, this most likely means that your service is still starting up. You can describe the task again to ensure that it has completed transitioning into a RUNNING state. After verifying that the lastStatus key is set to RUNNING, you should be able to test your container.

Testing the Task

You will need a modern web browser installed on your system to connect to the container and test the web game.

In the previous output, you’ll notice that the privateIPv4Address for the example task was listed as 10.4.0.100. Yours will be different, and you may also have a publicIPv4Address if you configured your service for that.

Ensure that you are connected to a network that can reach either the public or private IP address of your host, then launch your web browser and navigate to port 8080 on that IP address.

In the example, this URL would look like:

http://10.4.0.100:8080/

If everything is working as expected, you should be greeted by the splash screen for “The Quantum Game,” which will then be quickly followed by the puzzle board.

The official version of the game can be found at http://quantumgame.io.

Note

We completely understand if you get distracted at this point and stop reading for a few hours while trying to solve some puzzles and learn a little bit of quantum mechanics at the same time. The book won’t notice! Put it down, play the puzzles, pick it back up later.

Stopping the Task

Right, so we have a running task. Now let’s take a look at stopping it. To do that, you need to know the task ID. One way to obtain this is by relisting all the tasks running in your cluster.

$ aws ecs list-tasks --cluster fargate-testing

{"taskArns":["arn:aws:ecs:...:task/2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801"]}

You can also obtain it from the service information:

$ aws ecs describe-services --cluster fargate-testing \

--services fargate-game-service

{...{"id":"a63e7114-9592-417c-96cf-559b82096cbc","createdAt":1520730006.052,"message":"(service fargate-game-service) has started 1..."}...}

Finally, we can stop the task by running the following command with the correct task ID:

$ aws ecs stop-task --cluster fargate-testing \

--task 2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801

{..."lastStatus":"RUNNING","desiredStatus":"STOPPED",...}

If you describe the task again using the same task ID, you should now see that the lastStatus key is set to STOPPED:

$ aws ecs describe-tasks --cluster fargate-testing \

--task 2781cc1c-bdae-46f3-a767-f53013cc3801

{..."lastStatus":"STOPPED","desiredStatus":"STOPPED",...}

And finally, listing all the tasks in our cluster should return an empty set:

$ aws ecs list-tasks --cluster fargate-testing

{"taskArns":[]}

At this point, you can start creating more complicated tasks that tie multiple containers together and rely on the ECS and Fargate tooling to spin up hosts and deploy the tasks into your cluster as needed.

Kubernetes

Now let’s take some time to look at Kubernetes. Since its release to the public during DockerCon 2014, Kubernetes has grown rapidly and is now probably the most widely adopted of the container platforms. It is not the most mature product today—that distinction goes to Mesos, which first launched in 2009 before containers were in widespread use—but Kubernetes has a great mix of functionality and a very strong community that includes many early Docker adopters. This mix has helped significantly increase its popularity over the years. At DockerCon EU 2017, Docker, Inc. announced that Kubernetes support will be coming to the Docker Engine tooling itself. Supported Docker clients can mix deployments between Swarm and Kubernetes from the same tooling, which makes Kubernetes even more attractive as a large-scale platform for Docker deployments.

But Docker’s Kubernetes implementation is only the latest in a large string of releases. Like Linux itself, Kubernetes is available in a number of distributions, both free and commercial. There are currently a few dozen that are available and supported to varying degrees. Its widespread adoption means Kubernetes now has some pretty nice tooling for running it locally, including a whole distribution that can be controlled and installed locally with a single binary: Minikube. That’s the distribution we’ll use to do a quick runthrough of a Kubernetes cluster. Most of the concepts you’ll learn while working with Minikube can be applied to any Kubernetes implementation, so it’s a great place to start.

What Is Minikube?

Minikube is a whole distribution of Kubernetes for a single instance. It runs on a virtual machine on your own computer and allows you to use all the same tooling against the cluster that you would use in a production system. In scope, it’s a little bit like Docker Compose: it will let you stand up a whole stack locally. It goes one step further than Compose, though, in that it actually has all the production APIs. As a result, if you run Kubernetes in production, you can have an environment on your desktop that is reasonably close in fucntion, if not in scale, to what you are running in production.

Minikube is fairly unique in that all of the distribution is controlled from a single binary you download and run locally. It will autodetect which virtual machine (VM) manager you have locally and will set up and run a VM with all of the necessary tooling on it. That means getting started with it is pretty simple.

So let’s install it!

Installing Minikube

Most of the installation is the same across all platforms because once you have the tools installed, they will be your gateway to the VM running your Kubernetes installation. Just skip to the section that applies to your operating system. Once you have the tool up and running, you can follow the shared documentation.

We need two tools to use Minikube effectively: minikube and kubectl. For the purposes of our simple installation, we’re going to leverage the fact that both of these commands are static binaries with no outside dependencies, which makes them easy to install.

Note

There are a number of other ways to install Minikube. We’re going to show you what we think is the simplest path on each platform. If you have strong preferences about how to do this, you should feel free to do so. On Windows, for example, you might prefer to use the Chocolatey package manager, or the Snap package system on Linux.

macOS

Just as in Chapter 3, you will need to have Homebrew installed on your system. If you don’t, go back to Chapter 3 and make sure you have it set up. Once you do, it’s trivial to install the minikube client:

$ brew cask install minikube

This will cause Hombrew to install a new cask, and then look there for the tooling to download Minikube. It will look something like this depending, on your configuration:

==> Auto-updated Homebrew! ... ==> Updated Formulae ... ==> Satisfying dependencies All Formula dependencies satisfied. ==> Downloading https://storage.googleapis.com/minikube/.../minikube-darwin-amd64 ######################################################################## 100.0% ==> Verifying checksum for Cask minikube ==> Installing Cask minikube ==> Linking Binary 'minikube-darwin-amd64' to '/usr/local/bin/minikube'.

That’s it! Let’s test to make sure it’s in your path:

$ which minikube /usr/local/bin/minikube

If you don’t get a response, you will need to make sure you have /usr/local/bin in your PATH environment variable. Assuming that passes, you now have the minikube tool installed.

Now you just need to get kubectl installed, and you can do that with brew as well. Generally, the version of Kubernetes in Homebrew will match the current release of Minikube, so using brew install should help prevent mismatches:

$ brew install kubernetes-cli ==> Downloading https://.../kubernetes-cli-1.9.3.high_sierra.bottle.tar.gz Already downloaded: /.../kubernetes-cli-1.9.3.high_sierra.bottle.tar.gz ==> Pouring kubernetes-cli-1.9.3.high_sierra.bottle.tar.gz ==> Caveats Bash completion has been installed to: /usr/local/etc/bash_completion.d zsh completions have been installed to: /usr/local/share/zsh/site-functions ==> Summary /usr/local/Cellar/kubernetes-cli/1.9.3: 172 files, 65.4MB

We’ll test that the same way we tested minikube:

$ which kubectl /usr/local/bin/kubectl

We’re good to go!

Windows

As with installing Docker on Windows, you’ll need to have Hyper-V or another supported virtualization platform installed in order to run the Kubernetes virtual machine. But there is no additional tooling needed on Windows. You’ll simply download the binary and put it in a place you have in your PATH so that you can execute it on the command line. As of this writing, the URL is hosted on googleapis, which is usually very reliable about maintaining APIs. You’ll want to rename that file to minikube.exe once you’ve downloaded it; otherwise, you’ll be doing a lot more typing than you probably want!

You then need to get the latest Kubernetes CLI tool, kubectl, in order to actually control your distribution. Unfortunately, there is not a /latest path for downloading that. So, to make sure you have the latest version, you need to get the latest version from the website and then plug it into a URL like this:

https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release/<VERSION>/bin/windows/amd64/kubectl.exe.

Once you’ve downloaded that, you again need to make sure it’s somewhere accessible from your PATH to make the rest of our exploration easier.

Linux

You can actually run Minikube on the Linux box itself. We don’t recommend doing that at first, because it’s harder to clean up afterward if you are just experimenting. So we need to have a version of Linux that has either KVM (Linux’s Kernel-based Virtual Machine) or VirtualBox. Because minikube is just a single binary, once you have it installed, there is no need to install any additional packages. And, because minikube is a statically linked binary, it should pretty much work on any distribution you want to run it on. Huzzah! We could be cool and do the installation all in a one-liner, but then if something goes wrong you might find it hard to understand the error. So let’s do it in a few steps. Note that at the time of this writing the binary is hosted on googleapis, which usually maintains very stable URLs. So, here we go:

# Download the file, save as 'minikube'

$ curl -Lo minikube \

https://storage.googleapis.com/minikube/releases/latest/minikube-linux-amd64

# Make it executable

$ chmod +x minikube

# Move it to /usr/local/bin

$ sudo mv minikube /usr/local/bin/

You’ll need to make sure that /usr/local/bin is in your path. Now that we have minikube we also need to fetch kubectl, which we can do like this:

# Get the latest version number

$ KUBE_VERSION=$(curl -s \

https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release/stable.txt)

# Fetch the executable

$ curl -LO \

https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/\

release/$(KUBE_VERSION)/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl

# Make it executable

$ chmod +x kubectl

# Move it to /usr/local/bin

$ sudo mv kubectl /usr/local/bin/

Note

One of the URLs in the previous example has been continued on the following line so that it fits in the margins. You may find that you need to re-assemble the URL and remove the back slashes for the command to work properly in your environment.

Running Kubernetes

Now that we have the minikube tool, we can use it to bootstrap our Kubernetes cluster. This is normally pretty straightforward. You usually don’t need to do any configuration beforehand. You can simply run:

$ minikube start Starting local Kubernetes v1.9.0 cluster... Starting VM... Downloading Minikube ISO 142.22 MB / 142.22 MB [============================================] 100.00% 0s Getting VM IP address... Moving files into cluster... Downloading localkube binary 162.41 MB / 162.41 MB [============================================] 100.00% 0s 0 B / 65 B [----------------------------------------------------------] 0.00% 65 B / 65 B [======================================================] 100.00% 0s Setting up certs... Connecting to cluster... Setting up kubeconfig... Starting cluster components... Kubectl is now configured to use the cluster. Loading cached images from config file.

So what did we just do? Minikube packs a lot into that one command. We installed a virtual machine that has a properly configured version of Docker on it. It then runs all of the necessary components of Kubernetes inside Docker containers on the host.

We can look at those containers to see what we got:

$ minikube ssh

_ _

_ _ ( ) ( )

___ ___ (_) ___ (_)| |/') _ _ | |_ __

/' _ ` _ `\| |/' _ `\| || , < ( ) ( )| '_`\ /'__`\

| ( ) ( ) || || ( ) || || |\`\ | (_) || |_) )( ___/

(_) (_) (_)(_)(_) (_)(_)(_) (_)`\___/'(_,__/'`\____)

$

On your Kubernetes cluster you probably won’t be SSHing into the command line that often. But we want to see what’s installed and get a handle on the fact that when we run minikube, we’re controlling a virtual machine. Let’s take a look at what is running on the Docker instance on our Kubernetes cluster:

$ docker ps CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND ... 6039cd53ec91 gcr.io/k8s.../storage-provisioner "/storage-provisioner" ... a28e64d209f7 fed89e8b4248 "/sidecar --v=2 --..." ... e84b6d75105b 459944ce8cc4 "/dnsmasq-nanny -v..." ... 539530cbe6e7 512cd7425a73 "/kube-dns --domai..." ... e73d514c68bf e94d2f21bc0c "/dashboard --inse..." ... 21e4b12c144f gcr.io/google_.../pause-amd64:3.0 "/pause" ... 696ac03d09f5 gcr.io/google_.../pause-amd64:3.0 "/pause" ... 47282c695e9e gcr.io/google_.../pause-amd64:3.0 "/pause" ... 92b1a4d2cd0c d166ffa9201a "/opt/kube-addons.sh" ... 97bab4a81ea8 gcr.io/google_.../pause-amd64:3.0 "/pause" ...

We won’t dive too much into what each components is. But by now you should hopefully see how the mechanism works. Also, it’s pretty easy to upgrade the components since they are just containers, are versioned, and can be pulled from Google’s container repository.

Minikube commands

In the interest of space and time, we won’t go through all of the commands for minikube. We encourage you to run it without any options, take a look at the output, and play around with what’s available. That being said, let’s take a quick look at some of the most interesting commands. We’ll cover a few more later in the course of installing an application stack, but here’s a quick survey.

To see what was going on inside the VM, earlier we used minikube ssh, which is great for debugging or inspecting containers directly. Without logging into the Minikube VM over SSH, we can always check on the cluster status using another minikube command:

$ minikube status minikube: Running cluster: Running kubectl: Correctly Configured: pointing to minikube-vm at 192.168.99.100

This shows us that everything is looking good, and also gives us the IP address of our virtual machine. For scripting purposes you can also retrieve just the IP address by calling minikube ip. At any time in the future, you can check your version of minikube by running minikube update-check and using the same mechanism you used to install it on your OS to upgrade it. Critically, the minikube status command also shows us that kubectl is installed and working properly.

We started the Kubernetes cluster with minikube start. As you might expect, following the style of Docker CLI arguments, minikube stop will stop all the Kubernetes components and the virtual machine and leave your system in a clean state.

Kubernetes Dashboard

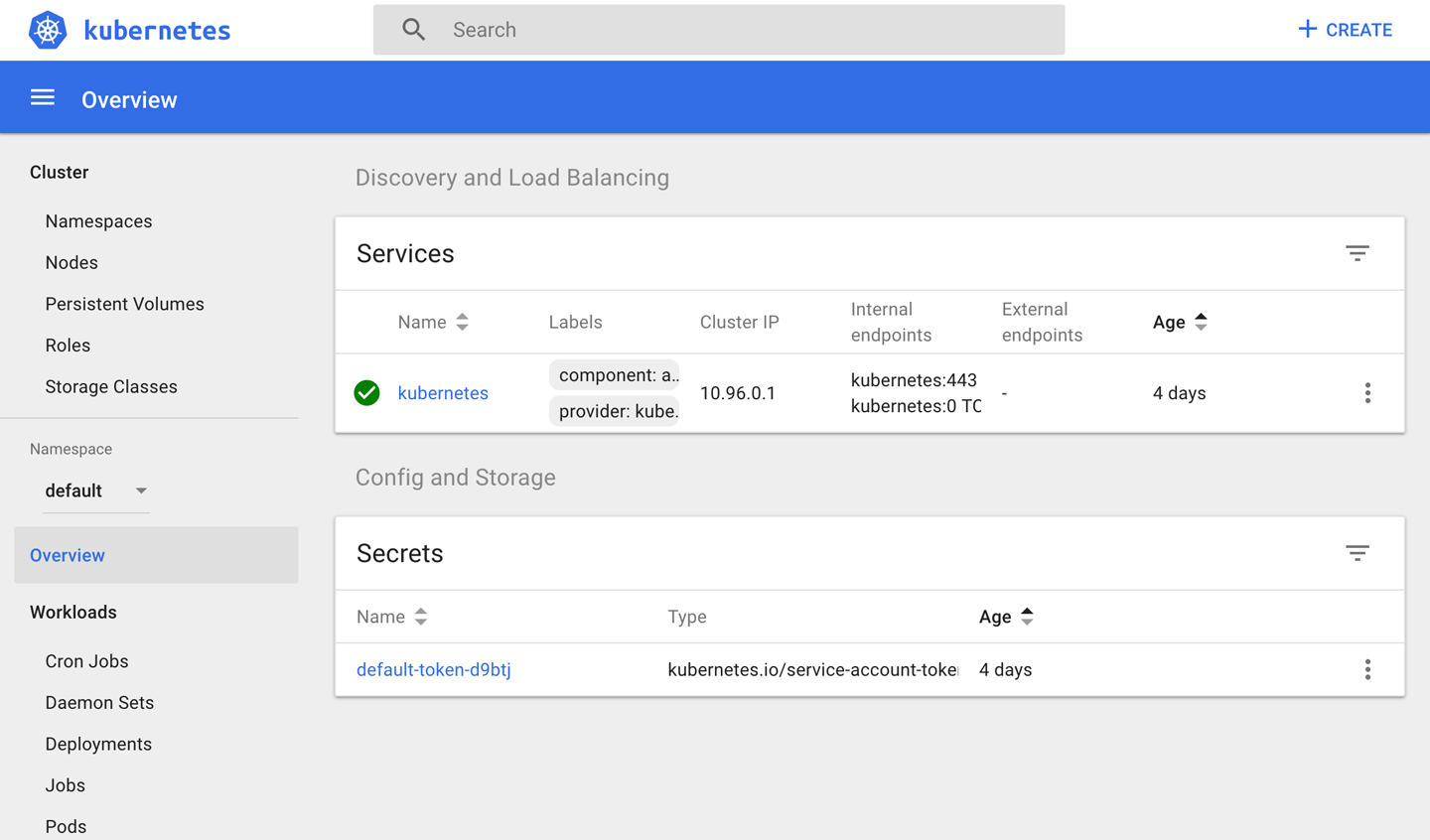

Now that we have Minikube up and running, we don’t just have the command-line tools to interact with, we actually have a whole UI installed that we can connect to. We reach it via the minikube dashboard command. Go ahead and run that—it should launch your web browser, pointed to the correct IP address and port of the Kubernetes dashboard! There is a lot of stuff on the dashboard and we’re not able to cover it all, but you should feel free to click around and explore. Many of the terms on the left will be familiar to you at this point, and some will be totally foreign. If you don’t have a computer in front of you, Figure 10-2 shows a screenshot of what an empty Minikube installation looks like from the dashboard.

Figure 10-2. Kubernetes dashboard

If you explore the Nodes link on the lefthand menu, you should see a single node in the cluster, named minikube. This is the virtual machine we started, and the dashboard, like the other components, is hosted in one of the containers we saw when we SSH’d into the host earlier. We’ll take another look at the dashboard when we’ve actually deployed something into our cluster.

Note

Kubernetes exposes almost everything that you see on the dashboard with the kubectl command as well, which makes it very scriptable with shell scripts.

While clicking around, you may notice that Kubernetes itself shows up as a component inside the system, just like your applications will.

Kubernetes Containers and Pods

Now that we have a Kubernetes cluster up and running and you’ve seen how easy that is to do locally, we need to pause to talk about a concept that Kubernetes adds on top of the container abstraction. Kubernetes came out of the experiences that Google had running their own massive platform. They encountered most of the situations you might see in a production platform and had to work out concepts to make it easier to understand and solve the kinds of problems you run into when managing a large installation. In doing so, they created a complex set of new abstractions. Kubernetes embraces many of these and thus has a whole vocabulary unto itself. We won’t try to get into all of these, but it’s important to understand the most central of these new abstractions—a concept that sits a layer above the container and is known as a pod.

In Kubernetes parlance, a pod is one or more containers sharing the same cgroups and namespaces. You can also isolate the containers themselves from each other inside the same pod using cgroups and namespaces. The idea is that you may have applications that need to be deployed together all the time and that the abstraction your scheduler needs to work with is the group of applications, not just a single container. All of the containers in the pod can talk to each other on localhost, which eliminates any need to discover each other. So why not just deploy a big container with all the applications inside it? The advantage of a pod over a supercontainer is that you can still resource-limit the individual application separately, and leverage the large library of public Docker containers to construct your application.

Additionally, Kubernetes administrators often leverage the pod abstraction to have a container run on pod startup to make sure things are configured properly for the others, to maintain a shared resource, or to announce the application to others, for example. This allows you to make finer-grained containers than you might if you have to group things into the same container. Another nice part of the pod abstraction is the ability to share mounted volumes.

Pods have a lifespan much like a Docker container. They are essentially ephemeral and can be moved between hosts according to the lifecycle of the application or the host it runs on. Containers in a pod even share the same IP address when facing the outside world, which means they look like a single entity from the network level. Just as you would run only one instance of an application per container, you generally run one instance of that container per pod. The easiest way to think about pods is that they are a group of Docker containers that work tegether as if they were one container, for most purposes. If you need only one container, then you still get a pod deployed by Kubernetes, but that pod contains only one container. The nice thing about this is that there really is only one abstraction as far as the Kubernetes scheduler is concerned: the pod. Containers are managed by some of the runtime pieces that construct the pod and also by the configuration that you use to define them.

One critical difference between a pod and a container is that you don’t construct pods in a build step. They are a runtime abstraction that lives only inside Kubernetes. So you build your Docker containers and send them to a registry, then define and deploy your pods using Kubernetes. In reality you don’t usually directly describe a pod, either; the tools generate it for you through the concept of a deployment. But the pod is the unit of execution and scheduling in a Kubernetes cluster. There is a lot more to it, but that’s the basic concept and it’s probably easiest to understand with a simple example. The pod abstraction is more complicated than thinking of your system in terms of individual containers, but it can be pretty powerful.

Let’s Deploy Something

When actually working with pods in Kubernetes, we usually manage them through the abstraction of a deployment. A deployment is just a pod definition with some health monitoring and replication. It contains the definition of the pod and a little metadata about it. So let’s look at a basic deployment and get it running.

The simplest thing we can deploy on Kubernetes is a pod that contains just one container. The Minikube project ships a sample application called echoserver that we can use to explore the basics of deployment on Kubernetes. We’ll call our deployment hello-minikube just like the Minikube documentation does.

We’ve used the minikube command, but to get things done on Kubernetes itself, we now need to leverage the kubectl command we installed earlier.

$ kubectl run hello-minikube --image=k8s.gcr.io/echoserver:1.4 --port=8080 deployment "hello-minikube" created

To see what that did for us, we can use the kubectl get command to list what’s now in our cluster. We’ll trim this down to the most interesting parts:

$ kubectl get all NAME DESIRED CURRENT UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE deploy/hello-minikube 1 1 1 1 2m NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGE rs/hello-minikube-c6c6764d 1 1 1 2m NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE po/hello-minikube-c6c6764d-cjcb4 1/1 Running 0 2m

With that one command, Kubernetes created a deployment, a replica set to manage scaling, and a pod. We ran this a couple minutes after running the first command so our pod is in the READY state. If yours isn’t, just wait and run the command a couple more times until you see it become READY. The bottom entry is a running service that represents Kubernetes itself. But where is our service? We can’t get to it yet. It’s essentially in the same state a Docker container would be if you didn’t tell it to expose any ports. So we need to tell Kubernetes to do that for us:

$ kubectl expose deployment hello-minikube --type=NodePort service "hello-minikube" exposed

This has now created a service we can reach and interact with. A service is a wrapper for one or more deployments of an application and can tell us how to contact the application. In this case, we get a NodePort, which works a lot like EXPOSE would for a container on Docker itself, but this time for the whole deployment. Let’s get Kubernetes to tell us how to get to it:

$ kubectl get svc NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE hello-minikube NodePort 10.101.150.217 <none> 8080:30616/TCP 3s kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 4d

You might think you could now connect to http://10.101.150.217:8080 to get to our service. But those addresses are not reachable from your host system because of the virtual machine in which Minikube is running. So we need to get minikube to tell us where to find the service:

$ minikube service hello-minikube --url http://192.168.99.100:30616

The nice thing about this command, like many of the other Kubernetes commands, is that it is scriptable and command-line-friendly. If we want to open it with curl on the command line, we can just include the minikube command call in our request:

$ curl $(minikube service hello-minikube --url) CLIENT VALUES: client_address=172.17.0.1 command=GET real path=/ query=nil request_version=1.1 request_uri=http://192.168.99.100:8080/ SERVER VALUES: server_version=nginx: 1.10.0 - lua: 10001 HEADERS RECEIVED: accept=*/* host=192.168.99.100:30616 user-agent=curl/7.54.0 BODY: -no body in request-

This uses nginx to grab some information from the request and play it back to us. Not the world’s most exciting application, admittedly, but you can see that we get back our own address, visible inside the Minikube virtual machine, and the request we passed with curl.

This is really the simplest use case. We didn’t really configure or define anything and relied on Kubernetes to do the right thing using its defaults. Next we’ll take a look at something more complicated. But first, let’s shut down our new service and deployment. It takes two commands to do that: one to remove the service and the other to delete it.

$ kubectl delete service hello-minikube service "hello-minikube" deleted $ kubectl delete deployment hello-minikube deployment "hello-minikube" deleted $ kubectl get all NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE svc/kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 4d

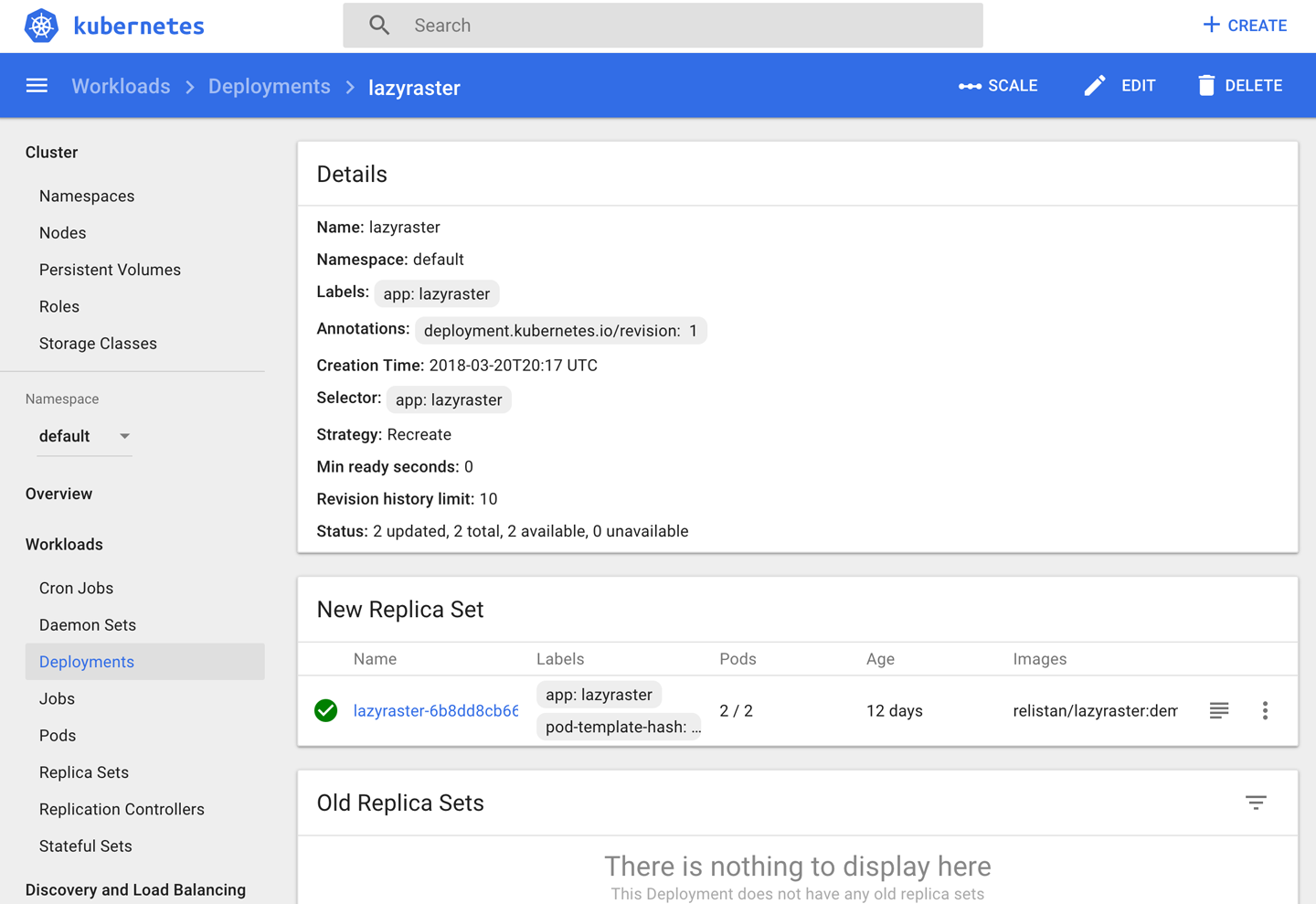

Deploying a Realistic Stack

Let’s now deploy something that looks more like a production stack. We’ll deploy an application that can fetch PDF documents from an S3 bucket, cache them on disk locally, and rasterize individual pages to PNG images on request, using the cached document. To run this application, we’ll want to write our cache files somewhere other than inside the container. We want to have them go somewhere a little more permanent and stable. And this time we want to make things repeatable, so that we’re not deploying our application through a series of CLI commands that we need to remember and hopefully get right each time. Kubernetes, much like Docker Compose, lets us define our stack in one or more YAML files that contain all of the definitions we care about in one place. This is what you want in a production environment and is similar to what you’ve seen for the other production tools.

The service we’ll now create will be called lazyraster (as in, “rasterize on demand”), and so each time you see that in the YAML definition, you’ll know we’re referring to our application. Our persistent volume will be called cache-data. Again, Kubernetes has a huge vocabulary that we can’t entirely address here, but to make it clear what we’re looking at we need to introduce two more concepts: PersistentVolume and PersistentVolumeClaim. A PersistentVolume is a physical resource that we provision inside the cluster. Kubernetes has support for many kinds of volumes, from local storage on a node to EBS volumes on AWS and similar on other cloud providers. It also supports NFS and other more modern network filesystems. A PersistentVolume stores data whose lifecycle is independent from our application or deployments. This lets us store data that persists between application deployments. For our cache, that’s what we’ll use. A PersistentVolumeClaim is a link between the physical resource of the PersistentVolume and the application that needs to consume it. We can set a policy on the claim that allows either a single read/write claim or many read claims. For our application we just want a single read/write claim to our cache-data PersistentVolume.

Tip

If you want more detail about some of the concepts we’ve talked about here, the Kubernetes project maintains a glossary of all the terms involved in operating Kubernetes. This can be really helpful. Each entry in the glossary is also linked to much more in-depth detail on other pages.

So let’s take a look at that big YAML file, which we’ll call lazyraster-service.yaml when it’s all pasted together. We’ll break it into sections so we can explain each part more easily. You can either pass each of these to kubectl separately or join them together into a single file, separated by ---, and pass them all at once, as we’ll do next. But it’s a lot easier to reason about the definitions separately.

Tip

You can also check out these files and a few others by running:

git clone \

https://github.com/bluewhalebook/\

docker-up-and-running-2nd-edition.git

The URL above has been continued on the following line so that it fits in the margins. You may find that you need to re-assemble the URL and remove the back slashes for the command to work properly.

Service Definition

apiVersion:v1kind:Servicemetadata:name:lazyrasterlabels:app:lazyrasterspec:type:NodePortports:-port:8000targetPort:8000protocol:TCPselector:app:lazyraster