Chapter 3. Corpus Preprocessing and Wrangling

In the previous chapter, we learned how to build and structure a custom, domain-specific corpus. Unfortunately, any real corpus in its raw form is completely unusable for analytics without significant preprocessing and compression. In fact, a key motivation for writing this book is the immense challenge we ourselves have encountered in our efforts to build and wrangle corpora large and rich enough to power meaningfully literate data products. Given how much of our own routine time and effort is dedicated to text preprocessing and wrangling, it is surprising how few resources exist to support (or even acknowledge!) these phases.

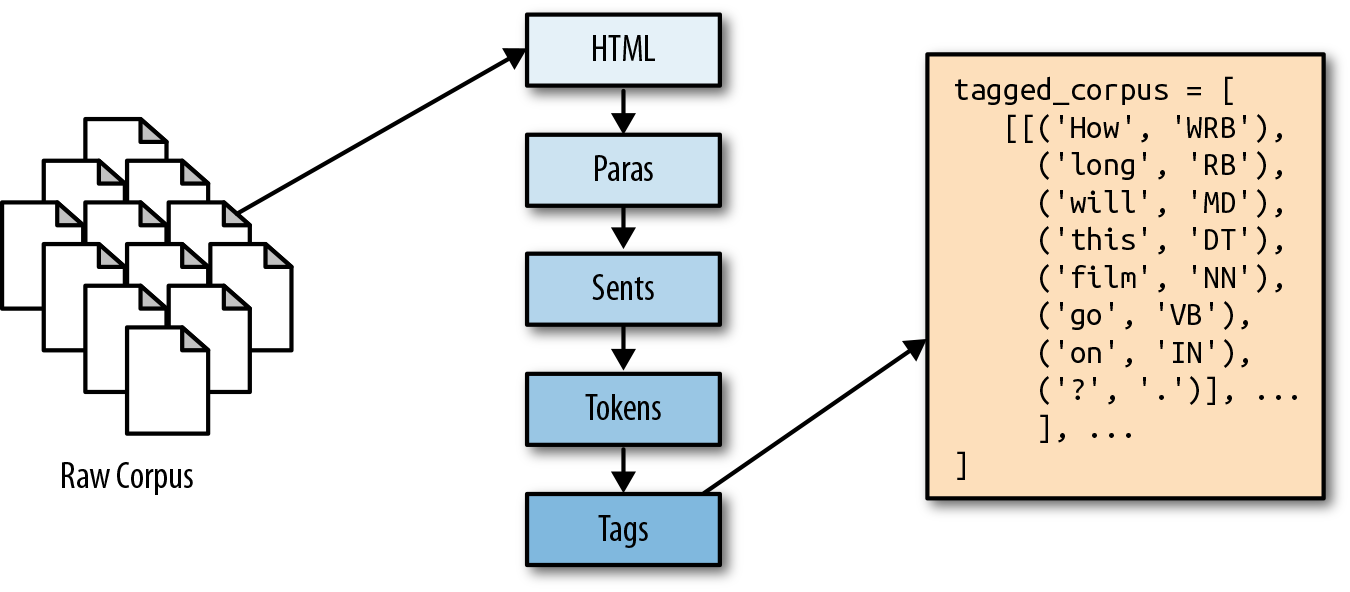

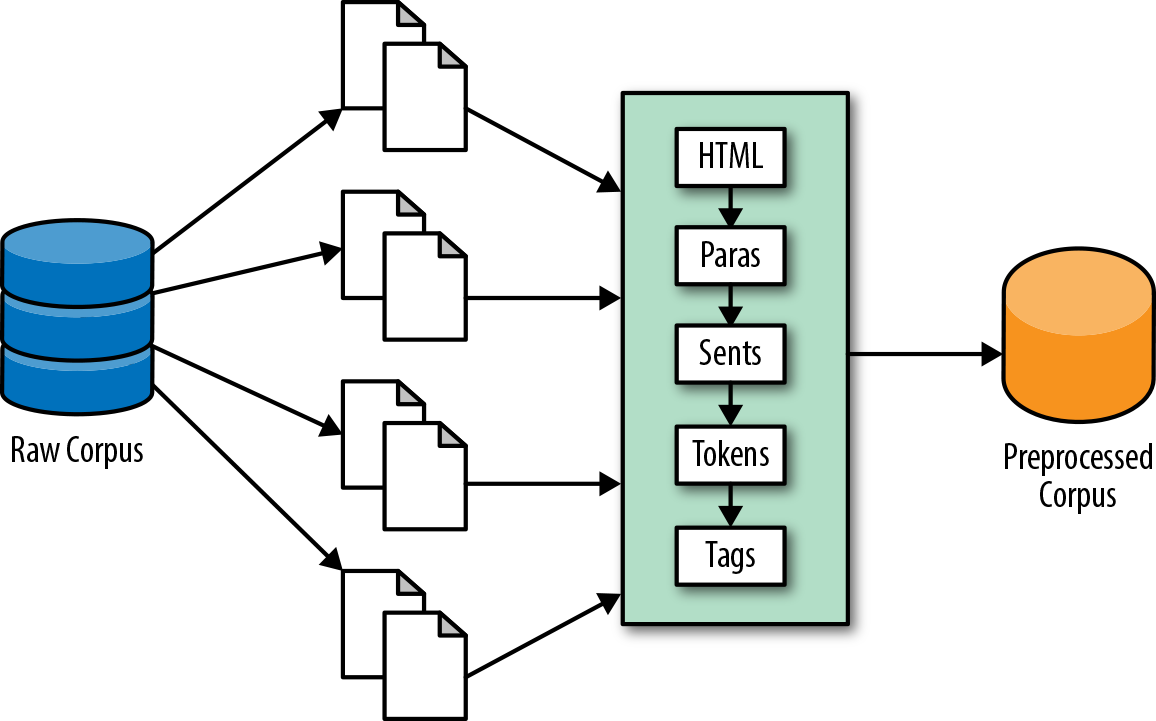

In this chapter, we propose a multipurpose preprocessing framework that can be used to systematically transform our raw ingested text into a form that is ready for computation and modeling. Our framework includes the five key stages shown in Figure 3-1: content extraction, paragraph blocking, sentence segmentation, word tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging. For each of these stages, we will provide functions conceived as methods under the HTMLCorpusReader class defined in the previous chapter.

Figure 3-1. Breakdown of document segmentation, tokenization, and tagging

Breaking Down Documents

In the previous chapter, we began constructing a custom HTMLCorpusReader, providing it with methods for filtering, accessing, and counting our documents (resolve(), docs(), and sizes()). Because it inherits from NLTK’s CorpusReader object, our custom corpus reader also implements a standard preprocessing API that also exposes the following methods:

raw()-

Provides access to the raw text without preprocessing

sents()-

A generator of individual sentences in the text

words()-

Tokenizes the text into individual words

In order to fit models using machine learning techniques on our text, we will need to include these methods as part of the feature extraction process. Throughout the rest of this chapter, we will discuss the details of preprocessing and show how to leverage and modify these methods to access content and explore features within our documents.

Note

While our focus here will be on language processing methods for a corpus reader designed to process HTML documents collected from the web, other methods may be more convenient depending on the form of your corpus. It is worth noting that NLTK CorpusReader objects already expose many other methods for different use cases; for example, automatically tagging or parsing sentences, converting annotated text into meaningful data structures like Tree objects, or providing format-specific utilities like individual XML elements.

Identifying and Extracting Core Content

Although the web is an excellent source of text with which to build novel and useful corpora, it is also a fairly lawless place in the sense that the underlying structures of web pages need not conform to any set standard. As a result, HTML content, while structured, can be produced and rendered in numerous and sometimes erratic ways. This unpredictability makes it very difficult to extract data from raw HTML text in a methodical and programmatic way.

The readability-lxml library is an excellent resource for grappling with the high degree of variability in documents collected from the web. Readability-lxml is a Python wrapper for the JavaScript Readability experiment by Arc90. Just as browsers like Safari and Chrome offer a reading mode, Readability removes distractions from the content of the page, leaving just the text.

Given an HTML document, Readability employs a series of regular expressions to remove navigation bars, advertisements, page script tags, and CSS, then builds a new Document Object Model (DOM) tree, extracts the text from the original tree, and reconstructs the text within the newly restructured tree. In the following example, which extends our HTMLCorpusReader, we import two readability modules, Unparseable and Document, which we can use to extract and clean the raw HTML text for the first phase of our preprocessing workflow.

The html method iterates over each file and uses the summary method from the readability.Document class to remove any nontext content as well as script and stylistic tags. It also corrects any of the most commonly misused tags (e.g., <div> and <br>), only throwing an exception if the original HTML is found to be unparseable. The most likely reason for such an exception is if the function is passed an empty document, which has nothing to parse:

fromreadability.readabilityimportUnparseablefromreadability.readabilityimportDocumentasPaperdefhtml(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Returns the HTML content of each document, cleaning it usingthe readability-lxml library."""fordocinself.docs(fileids,categories):try:yieldPaper(doc).summary()exceptUnparseablease:("Could not parse HTML: {}".format(e))continue

Note that the above method may generate warnings about the readability logger; you can adjust the level of verbosity according to your taste by adding:

importlogginglog=logging.getLogger("readability.readability")log.setLevel('WARNING')

The result of our new html() method is clean and well-structured HTML text. In the next few sections, we will create additional methods to incrementally decompose this text into paragraphs, sentences, and tokens.

Deconstructing Documents into Paragraphs

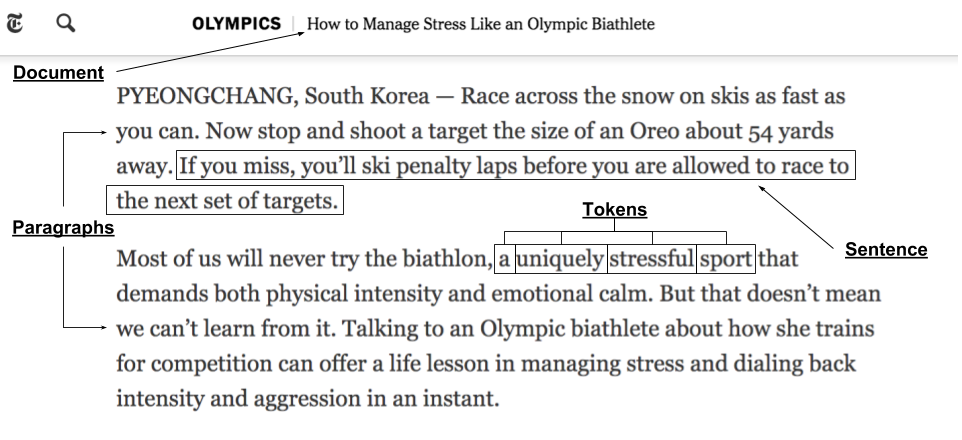

Now that we are able to filter the raw HTML text that we ingested in the previous chapter, we will move toward building a preprocessed corpus that is structured in a way that will facilitate machine learning. In Figure 3-2 we see how meaning is distributed across the elements of a New York Times news article.1 As we can see, the granularity with which we inspect this document may dramatically impact whether we classify it as a “popular sports” article or instead one about “personal health” (or both!).

Figure 3-2. Document decomposition illustrating the distribution of meaning across paragraphs, sentences, and individual tokens

This example illustrates why the vectorization, feature extraction, and machine learning tasks we will perform in subsequent chapters will rely so much on our ability to effectively break our documents down into their component pieces while also preserving their original structure.

Note

The precision and sensitivity of our models will rely on how effectively we are able to link tokens with the textual contexts in which they appear.

Paragraphs encapsulate complete ideas, functioning as the unit of document structure, and our first step will be to isolate the paragraphs that appear within the text. Some NLTK corpus readers, such as the PlaintextCorpusReader, implement a paras() method, which is a generator of paragraphs defined as blocks of text delimited with double newlines.

Our text, however, is not plain text, so we will need to create a method that extracts the paragraphs from HTML. Fortunately, our html() method retains the structure of our HTML documents. This means we can isolate content that appears within paragraphs by searching for <p> tags, the element that formally defines an HTML paragraph. Because content can also appear in other ways (e.g., embedded inside other structures within the document like headings and lists), we will search broadly through the text using BeautifulSoup.

Note

Recall that in Chapter 2 we defined our HTMLCorpusReader class so that reader objects will have the HTML document tags as a class attribute. This tag set can be expanded, abbreviated, or otherwise modified according to your context.

We will define a paras() method to iterate through each fileid and pass each HTML document to the BeautifulSoup constructor, specifying that the HTML should be parsed using the lxml HTML parser. The resulting soup is a nested tree structure that we can navigate using the original HTML tags and elements. For each of our document soups, we then iterate through each of the tags from our predefined set and yield the text from within that tag. We can then call BeautifulSoup’s decompose method to destroy the tree when we’re done working with each file to free up memory.

importbs4# Tags to extract as paragraphs from the HTML texttags=['h1','h2','h3','h4','h5','h6','h7','p','li']defparas(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Uses BeautifulSoup to parse the paragraphs from the HTML."""forhtmlinself.html(fileids,categories):soup=bs4.BeautifulSoup(html,'lxml')forelementinsoup.find_all(tags):yieldelement.textsoup.decompose()

The result of our paras() method is a generator with the raw text paragraphs from every document, from first to last, with no document boundaries. If passed a specific fileid, paras will return the paragraphs from that file only.

Note

It’s worth noting that the paras() methods for many of the NLTK corpus readers, such as PlaintextCorpusReader, function differently, frequently doing segmentation and tokenization in addition to isolating the paragraphs. This is because NLTK methods tend to expect a corpus that has already been annotated, and are thus not concerned with reconstructing paragraphs. By contrast, our methods are designed to work on raw, unannotated corpora and will need to support corpus reconstruction.

Segmentation: Breaking Out Sentences

If we can think of paragraphs as the units of document structure, it is useful to see sentences as the units of discourse. Just as a paragraph within a document comprises a single idea, a sentence contains a complete language structure, one that we want to be able to identify and encode.

In this section, we’ll perform segmentation to parse our text into sentences, which will facilitate the part-of-speech tagging methods we will use a bit later in this chapter (which rely on an internally consistent morphology). To get to our sentences, we’ll write a new method, sents(), that wraps paras() and returns a generator (an iterator) yielding each sentence from every paragraph.

Note

Syntactic segmentation is not necessarily a prerequisite for part-of-speech tagging. Depending on your use case, tagging can be used to break text into sentences, as with spoken or transcribed speech data, where sentence boundaries are less clear. In written text, performing segmentation first facilitates part-of-speech tagging. SpaCy’s tools often work better with speech data, while NLTK’s work better with written language.

Our sents() method iterates through each of the paragraphs isolated with our paras method, using the built-in NLTK sent_tokenize method to conduct segmentation. Under the hood, sent_tokenize employs the PunktSentenceTokenizer, a pre-trained model that has learned transformation rules (essentially a series of regular expressions) for the kinds of words and punctuation (e.g., periods, question marks, exclamation points, capitalization, etc.) that signal the beginnings and ends of sentences. The model can be applied to a paragraph to produce a generator of sentences:

fromnltkimportsent_tokenizedefsents(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Uses the built in sentence tokenizer to extract sentences from theparagraphs. Note that this method uses BeautifulSoup to parse HTML."""forparagraphinself.paras(fileids,categories):forsentenceinsent_tokenize(paragraph):yieldsentence

NLTK’s PunktSentenceTokenizer is trained on English text, and it works well for most European languages. It performs well when provided standard paragraphs:

['Beautiful is better than ugly.', 'Explicit is better than implicit.', 'Simple is better than complex.', 'Complex is better than complicated.', 'Flat is better than nested.', 'Sparse is better than dense.', 'Readability counts.', "Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.", 'Although practicality beats purity.', 'Errors should never pass silently.', 'Unless explicitly silenced.', 'In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.', 'There should be one-- and preferably only one -- obvious way to do it.', "Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.", 'Now is better than never.', 'Although never is often better than *right* now.', "If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.", 'If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.', "Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!"]

However, punctuation marks can be ambiguous; while periods frequently signal the end of a sentence, they can also appear in floats, abbreviations, and ellipses. In other words, identifying the boundaries between sentences can be tricky. As a result, you may find that using PunktSentenceTokenizer on nonstandard text will not always produce usable results:

['Baa, baa, black sheep,\nHave you any wool?', 'Yes, sir, yes, sir,\nThree bags full;\nOne for the master,\nAnd one for the dame,\nAnd one for the little boy\nWho lives down the lane.']

NLTK does provide alternative sentences tokenizers (e.g., for tweets), which are worth exploring. Nonetheless, if your domain space has special peculiarities in the way that sentences are demarcated, it’s advisable to train your own tokenizer using domain-specific content.

Tokenization: Identifying Individual Tokens

We’ve defined sentences as the units of discourse and paragraphs as the units of document structure. In this section, we will isolate tokens, the syntactic units of language that encode semantic information within sequences of characters.

Tokenization is the process by which we’ll arrive at those tokens, and we’ll use WordPunctTokenizer, a regular expression–based tokenizer that splits text on both whitespace and punctuation and returns a list of alphabetic and nonalphabetic characters:

fromnltkimportwordpunct_tokenizedefwords(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Uses the built-in word tokenizer to extract tokens from sentences.Note that this method uses BeautifulSoup to parse HTML content."""forsentenceinself.sents(fileids,categories):fortokeninwordpunct_tokenize(sentence):yieldtoken

As with sentence demarcation, tokenization is not always straightforward. We must consider things like: do we want to remove punctuation from tokens, and if so, should we make punctuation marks tokens themselves? Should we preserve hyphenated words as compound elements or break them apart? Should we approach contractions as one token or two, and if they are two tokens, where should they be split?

We can select different tokenizers depending on our responses to these questions. Of the many word tokenizers available in NLTK (e.g., TreebankWordTokenizer, WordPunctTokenize, PunktWordTokenizer, etc.), a common choice for tokenization is word_tokenize, which invokes the Treebank tokenizer and uses regular expressions to tokenize text as in Penn Treebank. This includes splitting standard contractions (e.g., “wouldn’t” becomes “would” and “n’t”) and treating punctuation marks (like commas, single quotes, and periods followed by whitespace) as separate tokens. By contrast, WordPunctTokenizer is based on the RegexpTokenizer class, which splits strings using the regular expression \w+|[^\w\s]+ , matching either tokens or separators between tokens and resulting in a sequence of alphabetic and nonalphabetic characters. You can also use the RegexpTokenizer class to create your own custom tokenizer.

Part-of-Speech Tagging

Now that we can access the tokens within the sentences of our document paragraphs, we will proceed to tag each token with its part of speech. Parts of speech (e.g., verbs, nouns, prepositions, adjectives) indicate how a word is functioning within the context of a sentence. In English, as in many other languages, a single word can function in multiple ways, and we would like to be able to distinguish those uses (e.g., “building” can be either a noun or a verb). Part-of-speech tagging entails labeling each token with the appropriate tag, which will encode information both about the word’s definition and its use in context.

We’ll use the off-the-shelf NLTK tagger, pos_tag, which at the time of this writing uses the PerceptronTagger() and the Penn Treebank tagset. The Penn Treebank tagset consists of 36 parts of speech, structural tags, and indicators of tense (NN for singular nouns, NNS for plural nouns, JJ for adjectives, RB for adverbs, VB for verbs, PRP for personal pronouns, etc.).

The tokenize method returns a generator that can give us a list of lists containing paragraphs, which are lists of sentences, which in turn are lists of part-of-speech tagged tokens. The tagged tokens are represented as (tag, token) tuples, where the tag is a case-sensitive string that specifies how the token is functioning in context:

fromnltkimportpos_tag,sent_tokenize,wordpunct_tokenizedeftokenize(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Segments, tokenizes, and tags a document in the corpus."""forparagraphinself.paras(fileids=fileids):yield[pos_tag(wordpunct_tokenize(sent))forsentinsent_tokenize(paragraph)]

Consider the paragraph “The old building is scheduled for demolition. The contractors will begin building a new structure next month.” The pos_tag method will differentiate how word “building” is used in context, first as a singular noun and then as the present participle of the verb “to build”:

[[('The', 'DT'), ('old', 'JJ'), ('building', 'NN'), ('is', 'VBZ'),

('scheduled', 'VBN'), ('for', 'IN'), ('demolition', 'NN'), ('.', '.')],

[('The', 'DT'), ('contractors', 'NNS'), ('will', 'MD'), ('begin', 'VB'),

('building', 'VBG'), ('a', 'DT'), ('new', 'JJ'), ('structure', 'NN'),

('next', 'JJ'), ('month', 'NN'), ('.', '.')]]

Note

Here’s the rule of thumb for deciphering part-of-speech tags: nouns start with an N, verbs with a V, adjectives with a J, adverbs with an R. Anything else is likely to be some kind of a structural element. A full list of tags can be found here: http://bit.ly/2JfUOrq.

NLTK provides several options for part-of-speech taggers (e.g., DefaultTagger, RegexpTagger, UnigramTagger, BrillTagger). Taggers can also be used in combination, such as the BrillTagger, which uses Brill transformational rules to improve initial tags.

Intermediate Corpus Analytics

Our HTMLCorpusReader now has all of the methods necessary to perform the document decompositions that will be needed in later chapters. In Chapter 2, we provided our reader with a sizes() method that enabled us to get a rough sense of how the corpus was changing over time. We can now add a new method, describe(), which will allow us to perform intermediate corpus analytics on its changing categories, vocabulary, and complexity.

First, describe() will start the clock and initialize two frequency distributions: the first, counts, to hold counts of the document substructures, and the second, tokens, to contain the vocabulary. Note that we’ll discuss and leverage frequency distributions in much greater detail in Chapter 7. We’ll keep a count of each paragraph, sentence, and word, and we’ll also store each unique token in our vocabulary. We then compute the number of files and categories in our corpus, and return a dictionary with a statistical summary of our corpus—its total number of files and categories; the total number of paragraph, sentences, and words; the number of unique terms; the lexical diversity, which is the ratio of unique terms to total words; the average number of paragraphs per document; the average number of sentences per paragraph; and the total processing time:

importtimedefdescribe(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Performs a single pass of the corpus andreturns a dictionary with a variety of metricsconcerning the state of the corpus."""started=time.time()# Structures to perform counting.counts=nltk.FreqDist()tokens=nltk.FreqDist()# Perform single pass over paragraphs, tokenize and countforparainself.paras(fileids,categories):counts['paras']+=1forsentinpara:counts['sents']+=1forword,taginsent:counts['words']+=1tokens[word]+=1# Compute the number of files and categories in the corpusn_fileids=len(self.resolve(fileids,categories)orself.fileids())n_topics=len(self.categories(self.resolve(fileids,categories)))# Return data structure with informationreturn{'files':n_fileids,'topics':n_topics,'paras':counts['paras'],'sents':counts['sents'],'words':counts['words'],'vocab':len(tokens),'lexdiv':float(counts['words'])/float(len(tokens)),'ppdoc':float(counts['paras'])/float(n_fileids),'sppar':float(counts['sents'])/float(counts['paras']),'secs':time.time()-started,}

As our corpus grows through ingestion, preprocessing, and compression, describe() allows us to recompute these metrics to see how they change over time. This can become a critical monitoring technique to help diagnose problems in the application; machine learning models will expect certain features of the data such as the lexical diversity and number of paragraphs per document to remain consistent, and if the corpus changes, it is very likely to impact performance. As such, the describe() method can be used to monitor for changes in the corpus that are sufficiently big to trigger a rebuild of any downstream vectorization and modeling.

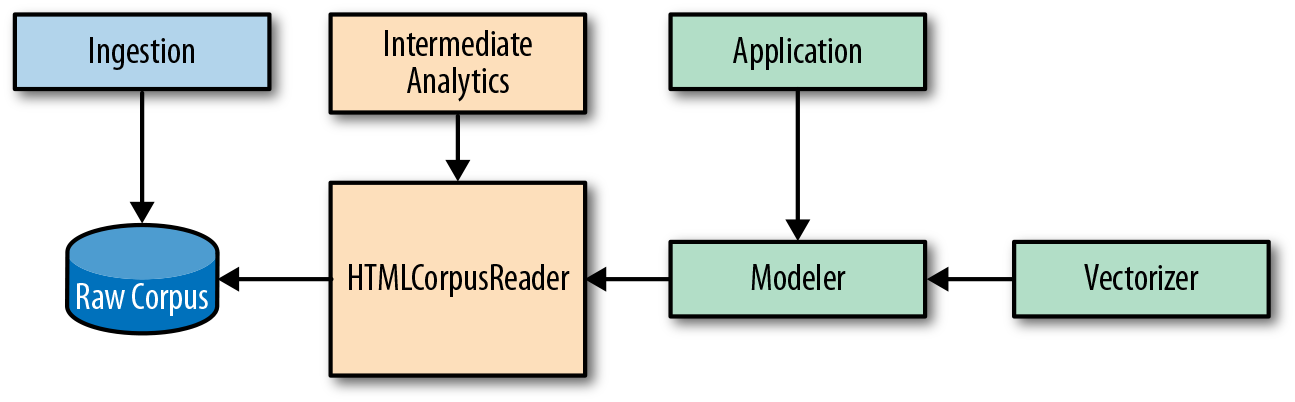

Corpus Transformation

Our reader can now stream raw documents from the corpus through the stages of content extraction, paragraph blocking, sentence segmentation, word tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging, and send the resulting processed documents to our machine learning models, as shown in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3. The pipeline from raw corpus to preprocessed corpus

Unfortunately, this preprocessing isn’t cheap. For smaller corpora, or in cases where many virtual machines can be allotted to preprocessing, a raw corpus reader such as HTMLCorpusReader may be enough. But on a corpus of roughly 300,000 HTML news articles, these preprocessing steps took over 12 hours. This is not something we will want to have to do every time we run our models or test out a new set of hyperparameters.

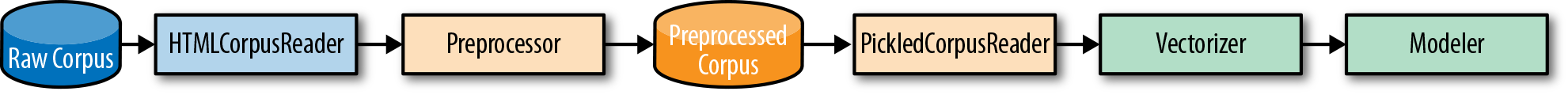

In practice, we address this by adding two additional classes, a Preprocessor class that wraps our HTMLCorpusReader to wrangle the raw corpus to store an intermediate transformed corpus artifact, and a PickledCorpusReader that can stream the transformed documents from disk in a standardized fashion for downstream vectorization and analysis, as shown in Figure 3-4.

Figure 3-4. A pipeline with intermediate storage of preprocessed corpus

Intermediate Preprocessing and Storage

In this section we’ll write a Preprocessor that takes our HTMLCorpusReader, executes the preprocessing steps, and writes out a new text corpus to disk, as shown in Figure 3-5. This new corpus is the one on which we will perform our text analytics.

Figure 3-5. An intermediate preprocessing stage to produce a transformed corpus artifact

We begin by defining a new class, Preprocessor, which will wrap our corpus reader and manage the stateful tokenization and part-of-speech tagging of our documents. The objects will be initialized with a corpus, the path to the raw corpus, and target, the path to the directory where we want to store the postprocessed corpus. The fileids() method will provide convenient access to the fileids of the HTMLCorpusReader object, and abspath() will returns the absolute path to the target fileid for each raw corpus fileid:

importosclassPreprocessor(object):"""The preprocessor wraps an `HTMLCorpusReader` and performs tokenizationand part-of-speech tagging."""def__init__(self,corpus,target=None,**kwargs):self.corpus=corpusself.target=targetdeffileids(self,fileids=None,categories=None):fileids=self.corpus.resolve(fileids,categories)iffileids:returnfileidsreturnself.corpus.fileids()defabspath(self,fileid):# Find the directory, relative to the corpus root.parent=os.path.relpath(os.path.dirname(self.corpus.abspath(fileid)),self.corpus.root)# Compute the name parts to reconstructbasename=os.path.basename(fileid)name,ext=os.path.splitext(basename)# Create the pickle file extensionbasename=name+'.pickle'# Return the path to the file relative to the target.returnos.path.normpath(os.path.join(self.target,parent,basename))

Next, we add a tokenize() method to our Preprocessor, which, given a raw document, will perform segmentation, tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging using the NLTK methods we explored in the previous section. This method will return a generator of paragraphs for each document that contains a list of sentences, which are in turn lists of part-of-speech tagged tokens:

fromnltkimportpos_tag,sent_tokenize,wordpunct_tokenize...deftokenize(self,fileid):forparagraphinself.corpus.paras(fileids=fileid):yield[pos_tag(wordpunct_tokenize(sent))forsentinsent_tokenize(paragraph)]

Note

As we gradually build up the text data structure we need (a list of documents, composed of lists of paragraphs, which are lists of sentences, where a sentence is a list of token, tag tuples), we are adding much more content to the original text than we are removing. For this reason, we should be prepared to apply a compression method to keep disk storage under control.

Writing to pickle

There are several options for transforming and saving a preprocessed corpus, but our preferred method is using pickle. With this approach we write an iterator that loads one document into memory at a time, converts it into the target data structure, and dumps a string representation of that structure to a small file on disk. While the resulting string representation is not human readable, it is compressed, easier to load, serialize and deserialize, and thus fairly efficient.

To save the transformed documents, we’ll add a preprocess() method. Once we have established a place on disk to retrieve the original files and to store their processed, pickled, compressed counterparts, we create a temporary document variable that creates our list of lists of lists of tuples data structure. Then, after we serialize the document and write it to disk using the highest compression option, we delete it before moving on to the next file to ensure that we are not holding extraneous content in memory:

importpickle...defprocess(self,fileid):"""For a single file, checks the location on disk to ensure no errors,uses +tokenize()+ to perform the preprocessing, and writes transformeddocument as a pickle to target location."""# Compute the outpath to write the file to.target=self.abspath(fileid)parent=os.path.dirname(target)# Make sure the directory existsifnotos.path.exists(parent):os.makedirs(parent)# Make sure that the parent is a directory and not a fileifnotos.path.isdir(parent):raiseValueError("Please supply a directory to write preprocessed data to.")# Create a data structure for the pickledocument=list(self.tokenize(fileid))# Open and serialize the pickle to diskwithopen(target,'wb')asf:pickle.dump(document,f,pickle.HIGHEST_PROTOCOL)# Clean up the documentdeldocument# Return the target fileidreturntarget

Our preprocess() method will be called multiple times by the following transform() runner:

...deftransform(self,fileids=None,categories=None):# Make the target directory if it doesn't already existifnotos.path.exists(self.target):os.makedirs(self.target)# Resolve the fileids to start processingforfileidinself.fileids(fileids,categories):yieldself.process(fileid)

In Chapter 11, we will explore methods for parallelizing this transform() method, which will enable rapid preprocessing and intermediate storage.

Reading the Processed Corpus

Once we have a compressed, preprocessed, pickled corpus, we can quickly access our corpus data without having to reapply tokenization methods or any string parsing—instead directly loading Python data structures and thus saving a significant amount of time and effort.

To read our corpus, we require a PickledCorpusReader class that uses pickle.load() to quickly retrieve the Python structures from one document at a time. This reader contains all the functionality of the HTMLCorpusReader (since it extends it), but since it isn’t working with raw text under the hood, it will be many times faster. Here, we override the HTMLCorpusReader docs() method with one that knows to load documents from pickles:

importpicklePKL_PATTERN=r'(?!\.)[a-z_\s]+/[a-f0-9]+\.pickle'classPickledCorpusReader(HTMLCorpusReader):def__init__(self,root,fileids=PKL_PATTERN,**kwargs):ifnotany(key.startswith('cat_')forkeyinkwargs.keys()):kwargs['cat_pattern']=CAT_PATTERNCategorizedCorpusReader.__init__(self,kwargs)CorpusReader.__init__(self,root,fileids)defdocs(self,fileids=None,categories=None):fileids=self.resolve(fileids,categories)# Load one pickled document into memory at a time.forpathinself.abspaths(fileids):withopen(path,'rb')asf:yieldpickle.load(f)

Because each document is represented as a Python list of paragraphs, we can implement a paras() method as follows:

...defparas(self,fileids=None,categories=None):fordocinself.docs(fileids,categories):forparaindoc:yieldpara

Each paragraph is also a list of sentences, so we can implement the sents() method similarly to return all sentences from the requested documents. Note that in this method like in the docs() and paras() method, the fileids and categories arguments allow you to specify exactly which documents to fetch information from; if both these arguments are None then the entire corpus is returned. A single document can be retrieved by passing its relative path to the corpus root to the fileids argument.

...defsents(self,fileids=None,categories=None):forparainself.paras(fileids,categories):forsentinpara:yieldsent

Sentences are lists of (token, tag) tuples, so we need two methods to access the ordered set of words that make up a document or documents. The first tagged() method returns the token and tag together, the second words() method returns only the token in question.

...deftagged(self,fileids=None,categories=None):forsentinself.sents(fileids,categories):fortagged_tokeninsent:yieldtagged_tokendefwords(self,fileids=None,categories=None):fortaggedinself.tagged(fileids,categories):yieldtagged[0]

When dealing with large corpora, the PickledCorpusReader makes things immensely easier. Although preprocessing and accessing data can be parallelized using the multiprocessing Python library (which we’ll see in Chapter 11), once the corpus is used to build models, a single sequential scan of all the documents before vectorization is required. Though this process can also be parallelized, it is not common to do so because of the experimental nature of exploratory modeling. Utilizing the pickle serialization speeds up the modeling and exploration process significantly!

Conclusion

In this chapter, we learned how to preprocess a corpus by performing segmentation, tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging in preparation for machine learning. In the next chapter, we will establish a common vocabulary for machine learning and discuss the ways in which machine learning on text differs from the kind of statistical programming we have done for previous applications.

First, we will consider how to frame learning problems now that our input data is text, meaning we are working in a very high-dimensional space where our instances are complete documents, and our features can include word-level attributes like vocabulary and token frequency, but also metadata like author, date, and source. Our next step will be to prepare our preprocessed text data for machine learning by encoding it as vectors. We’ll weigh several techniques for vector encoding, and discuss how to wrap that encoding process in a pipeline to allow for systematic loading, normalization, and feature extraction. Finally, we’ll discuss how to reunite the extracted features to allow for more complex analysis and more sophisticated modeling. These steps will leave us poised to extract meaningful patterns from our corpus and to use those patterns to make predictions about new, as-yet unseen data.

1 Tara Parker-Pope, How to Manage Stress Like a Biathlete, (2018) https://nyti.ms/2GJBGwr