Chapter 2. Building a Custom Corpus

As with any machine learning application, the primary challenge is to determine if and where the signal is hiding within the noise. This is done through the process of feature analysis—determining which features, properties, or dimensions about our text best encode its meaning and underlying structure. In the previous chapter, we began to see that, in spite of the complexity and flexibility of natural language, it is possible to model if we can extract its structural and contextual features.

The bulk of our work in the subsequent chapters will be in “feature extraction” and “knowledge engineering”—where we’ll be concerned with the identification of unique vocabulary words, sets of synonyms, interrelationships between entities, and semantic contexts. As we will see throughout the book, the representation of the underlying linguistic structure we use largely determines how successful we will be. Determining a representation requires us to define the units of language—the things that we count, measure, analyze, or learn from.

At some level, text analysis is the act of breaking up larger bodies of work into their constituent components—unique vocabulary words, common phrases, syntactical patterns—then applying statistical mechanisms to them. By learning on these components we can produce models of language that allow us to augment applications with a predictive capability. We will soon see that there are many levels to which we can apply our analysis, all of which revolve around a central text dataset: the corpus.

What Is a Corpus?

Corpora are collections of related documents that contain natural language. A corpus can be large or small, though generally they consist of dozens or even hundreds of gigabytes of data inside of thousands of documents. For instance, considering that the average email inbox is 2 GB (for reference, the full version of the Enron corpus, now roughly 15 years old, includes 1 M emails between 118 users and is 160 GB in size1), a moderately sized company of 200 employees would have around a half-terabyte email corpus. Corpora can be annotated, meaning that the text or documents are labeled with the correct responses for supervised learning algorithms (e.g., to build a filter to detect spam email), or unannotated, making them candidates for topic modeling and document clustering (e.g., to explore shifts in latent themes within messages over time).

A corpus can be broken down into categories of documents or individual documents. Documents contained by a corpus can vary in size, from tweets to books, but they contain text (and sometimes metadata) and a set of related ideas. Documents can in turn be broken into paragraphs, units of discourse that generally each express a single idea. Paragraphs can be further broken down into sentences, which are units of syntax; a complete sentence is structurally sound as a specific expression. Sentences are made up of words and punctuation, the lexical units that indicate general meaning but are far more useful in combination. Finally, words themselves are made up of syllables, phonemes, affixes, and characters, units that are only meaningful when combined into words.

Domain-Specific Corpora

It is very common to begin testing out a natural language model with a generic corpus. There are, for instance, many examples and research papers that leverage readily available datasets such as the Brown corpus, Wikipedia corpus, or Cornell movie dialogue corpus. However, the best language models are often highly constrained and application-specific.

Why is it that models trained in a specific field or domain of the language would perform better than ones trained on general language? Different domains use different language (vocabulary, acronyms, common phrases, etc.), so a corpus that is relatively pure in domain will be able to be analyzed and modeled better than one that contains documents from several different domains.

Consider that the term “bank” is very likely to be an institution that produces fiscal and monetary tools in an economics, financial, or political domain, whereas in an aviation or vehicular domain it is more likely to be a form of motion that results in the change of direction of a vehicle or aircraft. By fitting models in a narrower context, the prediction space is smaller and more specific, and therefore better able to handle the flexible aspects of language.

Acquiring a domain-specific corpus will be essential to producing a language-aware data product that performs well. Naturally the next question should then be “How do we construct a dataset with which to build a language model?” Whether it is done via scraping, RSS ingestion, or an API, ingesting a raw text corpus in a form that will support the construction of a data product is no trivial task.

Often data scientists start by collecting a single, static set of documents and then applying routine analyses. However, without considering routine and programmatic data ingestion, analytics will be static and unable to respond to new feedback or to the dynamic nature of language.

In this chapter, our primary focus will be not on how the data is acquired, but on how it should be structured and managed in a way that will support machine learning. However, in the next section, we will briefly present a framework for an ingestion engine called Baleen, which is particularly well-suited to the construction of domain-specific corpora for applied text analysis.

The Baleen Ingestion Engine

Baleen2 is an open source tool for building custom corpora. It works by ingesting natural language data from the discourse of professional and amateur writers, like bloggers and news outlets, in a categorized fashion.

Given an OPML file of RSS feeds (a common export format for news readers), Baleen downloads all the posts from those feeds, saves them to MongoDB storage, then exports a text corpus that can be used for analytics. While this task seems like it could be easily completed with a single function, the actual implementation of ingestion can become complex; APIs and RSS feeds can and often do change. Significant forethought is required to determine how best to put together an application that will conduct not only robust, autonomous ingestion, but also secure data management.

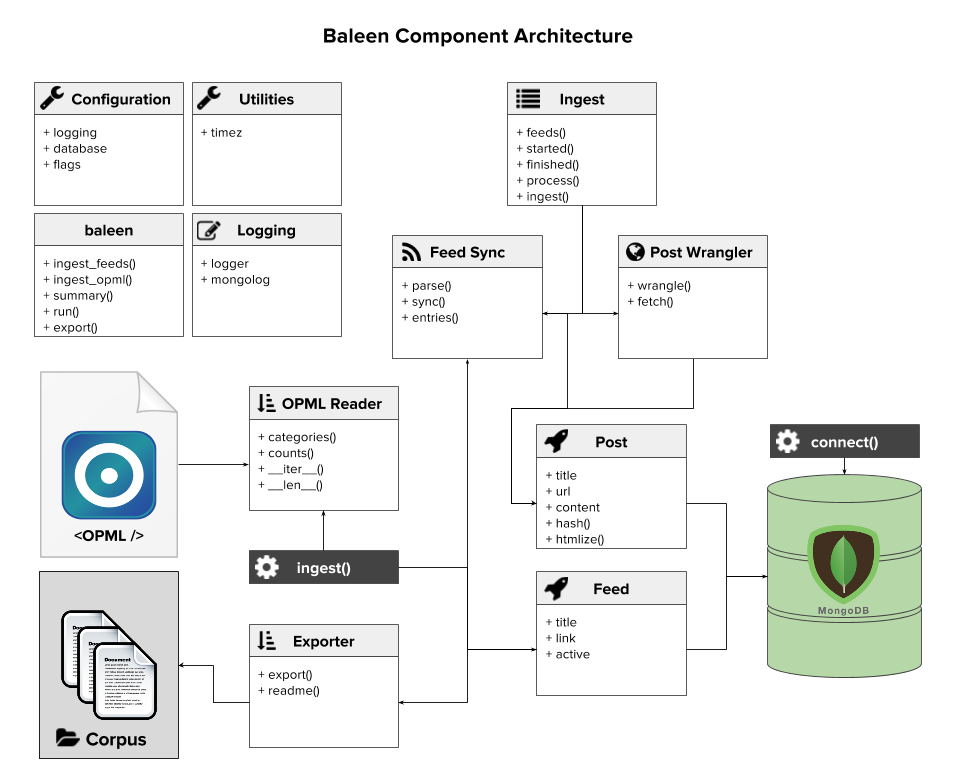

The complexity of routine text ingestion via RSS is shown in Figure 2-1. The fixture that specifies what feeds to ingest and how they’re categorized is an OPML file that must be read from disk. Connecting and inserting posts, feeds, and other information to the MongoDB store requires an object document mapping (ODM), and tools are needed to define a single ingestion job that synchronizes entire feeds and then fetches and wrangles individual posts or articles.

With these mechanisms in place, Baleen exposes utilities to run the ingestion job on a routine basis (e.g., hourly), though some configuration is required to specify database connection parameters and how often to run. Since this will be a long-running process, Baleen also provides a console to assist with scheduling, logging, and monitoring for errors. Finally, Baleen’s export tool exports the corpus out of the database.

Note

As currently implemented, the Baleen ingestion engine collects RSS feeds from 12 categories, including sports, gaming, politics, cooking, and news. As such, Baleen produces not one but 12 domain-specific corpora, a sample of which are available via our GitHub repository for the book: https://github.com/foxbook/atap/.

Figure 2-1. The Baleen RSS ingestion architecture

Whether documents are routinely ingested or part of a fixed collection, some thought must go into how to manage the data and prepare it for analytical processing and model computation. In the next section, we will discuss how to monitor corpora as our ingestion routines continue and the data change and grow.

Corpus Data Management

The first assumption we should make is that the corpora we will be dealing with will be nontrivial in size—that is, they will contain thousands or tens of thousands of documents comprising gigabytes of data. The second assumption is that the language data will come from a source that will need to be cleaned and processed into data structures that we can perform analytics on. The former assumption requires a computing methodology that can scale (which we’ll explore more fully in Chapter 11), and the latter implies that we will be performing irreversible transformations on the data (as we’ll see in Chapter 3).

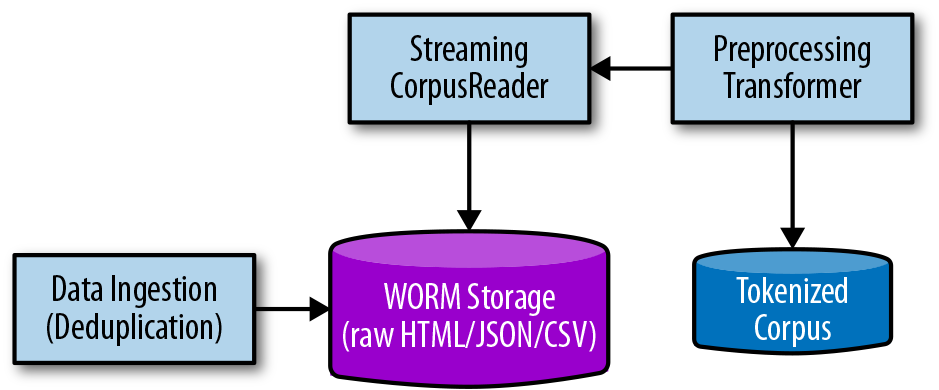

Data products often employ write-once, read-many (WORM) storage as an intermediate data management layer between ingestion and preprocessing as shown in Figure 2-2. WORM stores (sometimes referred to as data lakes) provide streaming read accesses to raw data in a repeatable and scalable fashion, addressing the requirement for performance computing. Moreover, by keeping data in a WORM store, preprocessed data can be reanalyzed without reingestion, allowing new hypotheses to be easily explored on the raw data format.

Figure 2-2. WORM storage supports an intermediate wrangling step

The addition of the WORM store to our data ingestion workflow means that we need to store data in two places—the raw corpus as well as the preprocessed corpus—which leads to the question: Where should that data be stored? When we think of data management, we usually think of databases first. Databases are certainly valuable tools in building language-aware data products, and many provide full-text search functionality and other types of indexing. However, most databases are constructed to retrieve or update only a couple of rows per transaction. In contrast, computational access to a text corpus will be a complete read of every single document, and will cause no in-place updates to the document, nor search or select individual documents. As such, databases tend to add overhead to computation without real benefit.

Note

Relational database management systems are great for transactions that operate on a small collection of rows at a time, particularly when those rows are updated frequently. Machine learning on a text corpus has a different computational profile: many sequential reads of the entire dataset. As a result, storing corpora on disk (or in a document database) is often preferred.

For text data management, the best choice is often to store data in a NoSQL document storage database that allows streaming reads of the documents with minimal overhead, or to simply write each document to disk. While a NoSQL application might be worthwhile in large applications, consider the benefits of using a file-based approach: compression techniques on directories are well suited to text information and the use of a file synchronization service provides automatic replication. The construction of a corpus in a database is beyond the scope of this book, though we will briefly explore a Sqlite corpus later in this chapter. Instead, we proceed by structuring our data on disk in a meaningful way that will support systematic access to our corpus.

Corpus Disk Structure

The simplest and most common method of organizing and managing a text-based corpus is to store individual documents in a file system on disk. By organizing the corpus into subdirectories, corpora can be categorized or meaningfully partitioned by meta information, like dates. By maintaining each document as its own file, corpus readers can seek quickly to different subsets of documents and processing can be parallelized, with each process taking a different subset of documents.

Note

NLTK CorpusReader objects, which we’ll explore in the next section, can read from either a path to a directory or a path to a Zip file.

Text is also the most compressible format, making Zip files, which leverage directory structures on disk, an ideal distribution and storage format. Finally, corpora stored on disk are generally static and treated as a whole, fulfilling the requirement for WORM storage presented in the previous section.

Storing a single document per file could lead to some challenges, however. Smaller documents like emails or tweets don’t make sense to store as individual files. Alternatively, email is typically stored in an MBox format—a plain-text format that uses separators to delimit multipart mime messages containing text, HTML, images, and attachments. These can typically be organized by the categories contained within the email service (Inbox, Starred, Archive, etc.). Tweets are generally small JSON data structures that include not just the text of the tweet but other metadata like user or location. The typical way to store multiple tweets is in newline-delimited JSON, sometimes called the JSON lines format. This format makes it easy to read one tweet at a time by parsing only a single line at a time, but also to seek to different tweets in the file. A single file of tweets can be large, so organizing tweets in files by user, location, or day can reduce overall file sizes and create a meaningful disk structure of multiple files.

An alternative technique to storing the data in some logical structure is simply to write files with a maximum size limit. For example, we can keep writing data to a file, respecting document boundaries, until it reaches some size limit (e.g., 128 MB) and then open a new file and continue writing there.

Note

A corpus on disk will necessarily contain many files that represent one or more documents in the corpus—sometimes partitioned into subdirectories that represent meaningful splits like category. Corpus and document meta information must also be stored along with its documents. As a result a standard structure for corpora on disk is vital to ensuring that data can be meaningfully read by Python programs.

Whether documents are aggregated into multidocument files or each stored as its own file, a corpus represents many files that need to be organized. If corpus ingestion occurs over time, a meaningful organization may be subdirectories for year, month, and day with documents placed into each folder, respectively. If the documents are categorized by sentiment, as positive or negative, each type of document can be grouped together into their own category subdirectory. If there are multiple users in a system that generate their own subcorpora of user-specific writing, such as reviews or tweets, then each user can have their own subdirectory. All subdirectories need to be stored alongside each other in a single corpus root directory. Importantly, corpus meta information such as a license, manifest, README, or citation must also be stored along with documents such that the corpus can be treated as an individual whole.

The Baleen disk structure

The choice of organization on disk has a large impact on how documents are read by CorpusReader objects, which we’ll explore in the next section. The Baleen corpus ingestion engine writes an HTML corpus to disk as follows:

corpus

├── citation.bib

├── feeds.json

├── LICENSE.md

├── manifest.json

├── README.md

└── books

| ├── 56d629e7c1808113ffb87eaf.html

| ├── 56d629e7c1808113ffb87eb3.html

| └── 56d629ebc1808113ffb87ed0.html

└── business

| ├── 56d625d5c1808113ffb87730.html

| ├── 56d625d6c1808113ffb87736.html

| └── 56d625ddc1808113ffb87752.html

└── cinema

| ├── 56d629b5c1808113ffb87d8f.html

| ├── 56d629b5c1808113ffb87d93.html

| └── 56d629b6c1808113ffb87d9a.html

└── cooking

├── 56d62af2c1808113ffb880ec.html

├── 56d62af2c1808113ffb880ee.html

└── 56d62af2c1808113ffb880fa.html

There are a few important things to note here. First, all documents are stored as HTML files, named according to their MD5 hash (to prevent duplication), and each stored in its own category subdirectory. It is simple to identify which files are documents and which files are meta both by the directory structure and the name of each file. In terms of meta information, a citation.bib file provides attribution for the corpus and the LICENSE.md file specifies the rights others have to use this corpus. While these two pieces of information are usually reserved for public corpora, it is helpful to include them so that it is clear how the corpus can be used—for the same reason that you would add this type of information to a private software repository. The feeds.json and manifest.json files are two corpus-specific files, that serve to identify information about the categories and each specific file, respectively. Finally, the README.md file is a human-readable description of the corpus.

Of these files, citation.bib, LICENSE.md, and README.md are special files because they can be automatically read from an NLTK CorpusReader object with the citation(), license(), and readme() methods.

A structured approach to corpus management and storage means that applied text analytics follows a scientific process of reproducibility, a method that encourages the interpretability of analytics as well as confidence in their results. Moreover, structuring a corpus as above enables us to use CorpusReader objects, which will be explained in detail in the next section.

Modifying these methods to deal with Markdown or to read corpus-specific files like the manifest is fairly simple:

importjson# In a custom corpus reader classdefmanifest(self):"""Reads and parses the manifest.json file in our corpus if it exists."""returnjson.load(self.open("README.md"))

These methods are specifically exposed programmatically to allow corpora to remain compressed, but still readable, minimizing the amount of storage required on disk. Consider that the README.md file is essential to communicating about the composition of the corpus, not just to other users or developers of the corpus, but also to “future you,” who may not remember specifics, and to be able to identify which models were trained on which corpora and what information those models have.

Corpus Readers

Once a corpus has been structured and organized on disk, two opportunities present themselves: a systematic approach to accessing the corpus in a programming context, and the ability to monitor and manage change in the corpus. We will discuss the latter at the end of the chapter, but for now we will tackle the subject of how to load documents for use in analytics.

Most nontrivial corpora contain thousands of documents with potentially gigabytes of text data. The raw text strings loaded from the documents then need to be preprocessed and parsed into a representation suitable for analysis, an additive process whose methods may generate or duplicate data, increasing the amount of required working memory. From a computational standpoint, this is an important consideration, because without some method to stream and select documents from disk, text analytics would quickly be bound to the performance of a single machine, limiting our ability to generate interesting models. Luckily, tools for streaming accesses of a corpus from disk have been well thought out by the NLTK library, which exposes corpora in Python via CorpusReader objects.

Note

Distributed computing frameworks such as Hadoop were created in response to the amount of text generated by web crawlers to produce search engines (Hadoop, inspired by two Google papers, was a follow-on project to the Nutch search engine). We will discuss cluster computing techniques to scaling with Spark, Hadoop’s distributed computing successor, in Chapter 11.

A CorpusReader is a programmatic interface to read, seek, stream, and filter documents, and furthermore to expose data wrangling techniques like encoding and preprocessing for code that requires access to data within a corpus. A CorpusReader is instantiated by passing a root path to the directory that contains the corpus files, a signature for discovering document names, as well as a file encoding (by default, UTF-8).

Because a corpus contains files beyond the documents meant for analysis (e.g., the README, citation, license, etc.) some mechanism must be provided to the reader to identify exactly what documents are part of the corpus. This mechanism is a parameter that can be specified explicitly as a list of names or implicitly as a regular expression that will be matched upon all documents under the root (e.g., \w+\.txt), which matches one or more characters or digits in the filename preceding the file extension, .txt. For instance, in the following directory, this regex pattern will match the three speeches and the transcript, but not the license, README, or metadata files:

corpus

├── LICENSE.md

├── README.md

├── citation.bib

├── transcript.txt

└── speeches

├── 04102008.txt

├── 10142009.txt

├── 09012014.txt

└── metadata.json

These three simple parameters then give the CorpusReader the ability to list the absolute paths of all documents in the corpus, to open each document with the correct encoding, and to allow programmers to access metadata separately.

Note

By default, NLTK CorpusReader objects can even access corpora that are compressed as Zip files, and simple extensions allow the reading of Gzip or Bzip compression as well.

By itself, the concept of a CorpusReader may not seem particularly spectacular, but when dealing with a myriad of documents, the interface allows programmers to read one or more documents into memory, to seek forward and backward to particular places in the corpus without opening or reading unnecessary documents, to stream data to an analytical process holding only one document in memory at a time, and to filter or select only specific documents from the corpus at a time. These techniques are what make in-memory text analytics possible for nontrivial corpora because they apply work to only a few documents in-memory at a time.

Therefore, in order to analyze your own text corpus in a specific domain that targets exactly the models you are attempting to build, you will need an application-specific corpus reader. This is so critical to enabling applied text analytics that we have devoted most of the remainder of this chapter to the subject! In this section we will discuss the corpus readers that come with NLTK and the possibility of structuring your corpus so that you can simply use one of them out of the box. We will then move forward into a discussion of how to define a custom corpus reader that does application-specific work, namely dealing with HTML files collected during the ingestion process.

Streaming Data Access with NLTK

NLTK comes with a variety of corpus readers (66 at the time of this writing) that are specifically designed to access the text corpora and lexical resources that can be downloaded with NLTK. It also comes with slightly more generic utility CorpusReader objects, which are fairly rigid in the corpus structure in that they expect but provide the opportunity to quickly create corpora and associate them with readers. They also give hints as to how to customize a CorpusReader for application-specific purposes. To name a few notable utility readers:

PlaintextCorpusReader-

A reader for corpora that consist of plain-text documents, where paragraphs are assumed to be split using blank lines.

TaggedCorpusReader-

A reader for simple part-of-speech tagged corpora, where sentences are on their own line and tokens are delimited with their tag.

BracketParseCorpusReader-

A reader for corpora that consist of parenthesis-delineated parse trees.

ChunkedCorpusReader-

A reader for chunked (and optionally tagged) corpora formatted with parentheses.

TwitterCorpusReader-

A reader for corpora that consist of tweets that have been serialized into line-delimited JSON.

WordListCorpusReader-

List of words, one per line. Blank lines are ignored.

XMLCorpusReader-

A reader for corpora whose documents are XML files.

CategorizedCorpusReader-

A mixin for corpus readers whose documents are organized by category.

The tagged, bracket parse, and chunked corpus readers are annotated corpus readers; if you’re going to be doing domain-specific hand annotation in advance of machine learning, then the formats exposed by these readers are important to understand. The Twitter, XML, and plain-text corpus readers all give hints about how to deal with data on disk that has different parseable formats, allowing for extensions related to CSV corpora, JSON, or even from a database. If your corpus is already in one of these formats, then you have little work to do. For example, consider a corpus of the plain-text scripts of the Star Wars and Star Trek movies organized as follows:

corpus ├── LICENSE ├── README └── Star Trek | ├── Star Trek - Balance of Terror.txt | ├── Star Trek - First Contact.txt | ├── Star Trek - Generations.txt | ├── Star Trek - Nemesis.txt | ├── Star Trek - The Motion Picture.txt | ├── Star Trek 2 - The Wrath of Khan.txt | └── Star Trek.txt └── Star Wars | ├── Star Wars Episode 1.txt | ├── Star Wars Episode 2.txt | ├── Star Wars Episode 3.txt | ├── Star Wars Episode 4.txt | ├── Star Wars Episode 5.txt | ├── Star Wars Episode 6.txt | └── Star Wars Episode 7.txt └── citation.bib

The CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader is perfect for accessing data from the movie scripts since the documents are .txt files and there are two categories, namely “Star Wars” and “Star Trek.” In order to use the CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader, we need to specify a regular expression that allows the reader to automatically determine both the fileids and categories:

fromnltk.corpus.reader.plaintextimportCategorizedPlaintextCorpusReaderDOC_PATTERN=r'(?!\.)[\w_\s]+/[\w\s\d\-]+\.txt'CAT_PATTERN=r'([\w_\s]+)/.*'corpus=CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader('/path/to/corpus/root',DOC_PATTERN,cat_pattern=CAT_PATTERN)

The document pattern regular expression specifies documents as having paths under the corpus root such that there is one or more letters, digits, spaces, or underscores, followed by the / character, then one or more letters, digits, spaces, or hyphens followed by .txt. This will match documents such as Star Wars/Star Wars Episode 1.txt but not documents such as episode.txt. The categories pattern regular expression truncates the original regular expression with a capture group that indicates that a category is any directory name (e.g., Star Wars/anything.txt will capture Star Wars as the category). You can start to access the data on disk by inspecting how these names are captured:

corpus.categories()# ['Star Trek', 'Star Wars']corpus.fileids()# ['Star Trek/Star Trek - Balance of Terror.txt',# 'Star Trek/Star Trek - First Contact.txt', ...]

Although regular expressions can be difficult, they do provide a powerful mechanism for specifying exactly what should be loaded by the corpus reader, and how. Alternatively, you could explicitly pass a list of categories and fileids, but that would make the corpus reader a lot less flexible. By using regular expressions you could add new categories by simply creating a directory in your corpus, and add new documents by moving them to the correct directory.

Now that we have access to the CorpusReader objects that come with NLTK, we will explore a methodology to stream the HTML data we have ingested.

Reading an HTML Corpus

Assuming we are ingesting data from the internet, it is a safe bet that the data we’re ingesting is formatted as HTML. One option for creating a streaming corpus reader is to simply strip all the tags from the HTML, writing it as plain text and using the CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader. However, if we do that, we will lose the benefits of HTML—namely computer parseable, structured text, which we can take advantage of when preprocessing. Therefore, in this section we will begin to design a custom HTMLCorpusReader that we will extend in the next chapter:

fromnltk.corpus.reader.apiimportCorpusReaderfromnltk.corpus.reader.apiimportCategorizedCorpusReaderCAT_PATTERN=r'([a-z_\s]+)/.*'DOC_PATTERN=r'(?!\.)[a-z_\s]+/[a-f0-9]+\.json'TAGS=['h1','h2','h3','h4','h5','h6','h7','p','li']classHTMLCorpusReader(CategorizedCorpusReader,CorpusReader):"""A corpus reader for raw HTML documents to enable preprocessing."""def__init__(self,root,fileids=DOC_PATTERN,encoding='utf8',tags=TAGS,**kwargs):"""Initialize the corpus reader. Categorization arguments(``cat_pattern``, ``cat_map``, and ``cat_file``) are passed tothe ``CategorizedCorpusReader`` constructor. The remainingarguments are passed to the ``CorpusReader`` constructor."""# Add the default category pattern if not passed into the class.ifnotany(key.startswith('cat_')forkeyinkwargs.keys()):kwargs['cat_pattern']=CAT_PATTERN# Initialize the NLTK corpus reader objectsCategorizedCorpusReader.__init__(self,kwargs)CorpusReader.__init__(self,root,fileids,encoding)# Save the tags that we specifically want to extract.self.tags=tags

Our HTMLCorpusReader class extends both the CategorizedCorpusReader and the CorpusReader, similarly to how the CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader uses the categorization mixin. Multiple inheritance can by tricky, so the bulk of the code in the __init__ function simply figures out which arguments to pass to which class. In particular, the CategorizedCorpusReader takes in generic keyword arguments, and the CorpusReader will be initialized with the root directory of the corpus, as well as the fileids and the HTML encoding scheme. However, we have also added our own customization, allowing the user to specify which HTML tags should be treated as independent paragraphs.

The next step is to augment the HTMLCorpusReader with a method that will allow us to filter how we read text data from disk, either by specifying a list of categories, or a list of filenames:

defresolve(self,fileids,categories):"""Returns a list of fileids or categories depending on what is passedto each internal corpus reader function. Implemented similarly tothe NLTK ``CategorizedPlaintextCorpusReader``."""iffileidsisnotNoneandcategoriesisnotNone:raiseValueError("Specify fileids or categories, not both")ifcategoriesisnotNone:returnself.fileids(categories)returnfileids

This method returns a list of fileids whether or not they have been categorized. In this sense, it both adds flexibility and exposes the method signature that we will use for pretty much every other method on the reader. In our resolve method, if both categories and fileids are specified, it will complain. If they are not specified, the method will use a CorpusReader method to compute the fileids associated with the specific categories. Note that categories can either be a single category or a list of categories. Otherwise, we will simply return the fileids—if this is None, the CorpusReader will automatically read every single document in the corpus without filtering.

Note

Note that the ability to read only part of a corpus will become essential as we move toward machine learning, particularly for doing cross-validation where we will have to create training and testing splits of the corpus.

At the moment, our HTMLCorpusReader doesn’t have a method for reading a stream of complete documents, one document at a time. Instead, it will expose the entire text of every single document in the corpus in a streaming fashion to our methods. However, we will want to parse one HTML document at a time, so the following method gives us access to the text on a document-by-document basis:

importcodecsdefdocs(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Returns the complete text of an HTML document, closing the documentafter we are done reading it and yielding it in a memory safe fashion."""# Resolve the fileids and the categoriesfileids=self.resolve(fileids,categories)# Create a generator, loading one document into memory at a time.forpath,encodinginself.abspaths(fileids,include_encoding=True):withcodecs.open(path,'r',encoding=encoding)asf:yieldf.read()

Our custom corpus reader now knows how to deal with individual documents in the corpus, one document at a time, allowing us to filter and seek to different places in the corpus. It can handle fileids and categories, and has all the tools imported from NLTK to make disk access easier.

Corpus monitoring

As we have established so far in this chapter, applied text analytics requires substantial data management and preprocessing. The methods described for data ingestion, management, and preprocessing are laborious and time-intensive, but also critical precursors to machine learning. Given the requisite time, energy, and disk storage commitments, it is good practice to include with the rest of the data some meta information about the details of how the corpus was built.

In this section, we will describe how to create a monitoring system for ingestion and preprocessing. To begin, we should consider what specific kinds of information we would like to monitor, such as the dates and sources of ingestion. Given the massive size of the corpora with which we will be working, we should at the very least, keep track of the size of each file on disk.

defsizes(self,fileids=None,categories=None):"""Returns a list of tuples, the fileid and size on disk of the file.This function is used to detect oddly large files in the corpus."""# Resolve the fileids and the categoriesfileids=self.resolve(fileids,categories)# Create a generator, getting every path and computing filesizeforpathinself.abspaths(fileids):yieldos.path.getsize(path)

One of our observations in working with RSS HTML corpora in practice is that in addition to text, a significant number of the ingested files came with embedded images, audio tracks, and video. These embedded media files quickly ate up memory during ingestion and were disruptive to preprocessing. The above sizes method is in part a reaction to these kinds of experiences with real-world corpora, and will help us to perform diagnostics and identify individual files within the corpus that are much larger than expected (e.g., images and video that have been encoded as text). This method will enable us to compute the complete size of the corpus, to track over time, and see how it is growing and changing.

Reading a Corpus from a Database

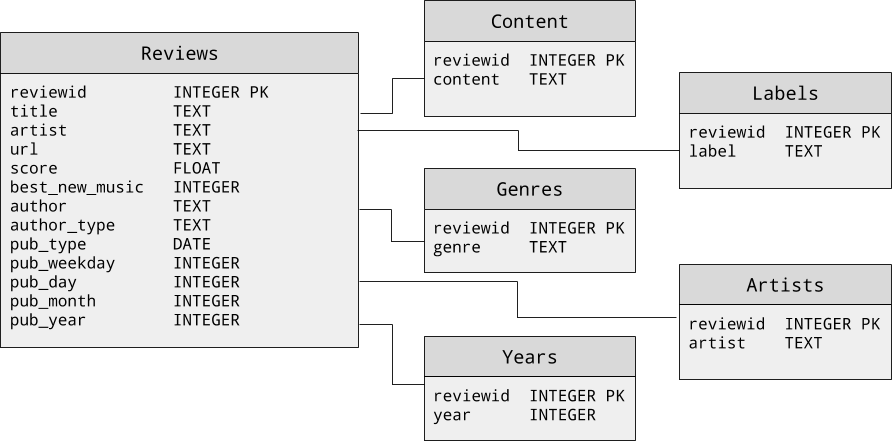

No two corpora are exactly alike, and just as every novel application will require a novel and domain-specific corpus, each corpus will require an application-specific corpus reader. In Chapter 12 we will explore a sentiment analysis application that uses a corpus of about 18,000 album reviews from the website Pitchfork.com. The extracted dataset is stored in a Sqlite database with the schema shown in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3. Schema for the album review corpus stored in a Sqlite database

To interact with this corpus, we will create a custom SqliteCorpusReader class to access its different components, mimicking the behavior of an NLTK CorpusReader, but not inheriting from it.

We want our SqliteCorpusReader to be able to fetch results from the database in a memory safe fashion; as with the HTMLCorpusReader from the previous section, we need to be able access one record at a time to perform wrangling, normalization, and transformation (which will be discussed in Chapter 3) in an efficient and streamlined way. For this reason, using the SQL-like fetchall() command is not advisable, and might keep us waiting for a long time for the results to come back before our iteration can begin. Instead, our ids(), scores(), and texts() methods each make use of fetchone(), a good alternative in this case, though with a larger database, batch-wise fetching (e.g., with fetchmany()) would be more performant.

importsqlite3classSqliteCorpusReader(object):def__init__(self,path):self._cur=sqlite3.connect(path).cursor()defids(self):"""Returns the review ids, which enable joins to otherreview metadata"""self._cur.execute("SELECT reviewid FROM content")foridxiniter(self._cur.fetchone,None):yieldidxdefscores(self):"""Returns the review score, to be used as the targetfor later supervised learning problems"""self._cur.execute("SELECT score FROM reviews")forscoreiniter(self._cur.fetchone,None):yieldscoredeftexts(self):"""Returns the full review texts, to be preprocessed andvectorized for supervised learning"""self._cur.execute("SELECT content FROM content")fortextiniter(self._cur.fetchone,None):yieldtext

As we can see from the HTMLCorpusReader and SqliteCorpusReader examples, we should be prepared to write a new corpus reader for each new dataset. However, we hope that these examples demonstrate not only their utility but their similarities. In the next chapter, we will extend our HTMLCorpusReader so that we can use it to access more granular components of our text, which will be useful for preprocessing and feature engineering.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have learned that text analytics requires a large, robust, domain-specific corpus. Since these will be very large, often unpredictable datasets, we discussed methods for structuring and managing these corpora over time. We learned how corpus readers can leverage this structure and also reduce memory pressure through streaming data loading. Finally, we started to build some custom corpus readers—one for a corpus of HTML documents stored on disk and one for a documents stored in a Sqlite database.

In the next chapter, we will learn how to preprocess our data and extend the work we have done in this chapter with methods to preprocess the raw HTML as it is streamed in a memory safe fashion and achieve our final text data structure in advance of machine learning—a list of documents, composed of lists of paragraphs, which are lists of sentences, where a sentence is a list of tuples containing a token and its part-of-speech tag.

1 Federal Energy Regulatory Committee, FERC Enron Dataset. http://bit.ly/2JJTOIv

2 District Data Labs, Baleen: An automated ingestion service for blogs to construct a corpus for NLP research, (2014) http://bit.ly/2GOFaxI