Several models of the Raspberry Pi have emerged since the first Model B and Model A successor. In this chapter, the ARM architecture is introduced along with CPU features supported by your Pi. Then the Linux API (application programming interface) for managing CPU in your application will be covered (threads).

/proc/cpuinfo

Session output listing /proc/cpuinfo on a Raspberry Pi 3 model B+

There are four groups with processors identified as 0 through 3 (only the first was shown in the figure). At the bottom of the file is listed Hardware, Revision, and a Serial number.

In the processor group is a line labeled “model name.” In this example, we see “ARMv7 Processor rev 4 (v7l)” listed. Also at the bottom, there is “Hardware” listed with the value “BCM2835”. Let’s take a moment to discuss what the architecture name implies.

ARM Architecture

Raspberry Pi ARM Architectures and Implementations

Architecture Name | Bus Size | Instruction Sets | SoC |

|---|---|---|---|

ARMv6Z | 32-bit | ARM and Thumb (16-bit) | BCM2835 |

ARMv7-A | 32-bit | ARM and Thumb (16-bit) | BCM2836 |

ARMv8-A | 32/64-bit | AArch32 (compatible with ARMv7-A) and AArch64 execution states. | BCM2837 |

The design and general capabilities are summarized in the columns Bus Size and Instruction Sets. Each new architecture added new features to the instruction set and other processor features.

The column SoC (system on chip) identifies the implementation of the architecture by Broadcom.

AArch32, with ARMv7-A architecture compatibility.

AArch64, with a new ARM 64-bit instruction set.

It is running the AArch32 execution state, for compatibility with the 32-bit Raspbian Linux code. Someday hopefully, we will see a true 64-bit Raspbian Linux.

Architecture Suffix

“A” for the Cortex-A family of application processors.

“R” for the Cortex-R family of real-time processors.

“M” for the Cortex-M family of low power, microcontroller processors.

In the architecture names ARMv7-A or ARMv8-A, we see that these belong to the application processor family. These are fully capable members, while the Cortex-R and Cortex-M families are often subsets or specialize in a few areas.

Features

ARM Features That May Be Listed in /proc/cpuinfo

Feature Name | Description |

|---|---|

half | Half-word loads and stores |

thumb | 16-bit Thumb instruction set support |

fastmult | 32x32 producing 64-bit multiplication support |

vfp | Early SIMD vector floating-point instructions |

edsp | DSP extensions |

neon | Advanced SIMD/NEON support |

vfpv3 | VFP version 3 support |

tls | TLS register |

vfpv4 | VFP version 4 with fast context switching |

idiva | SDIV and UDIV hardware division in ARM mode |

idivt | SDIV and UDIV hardware division in Thumb mode |

vfpd32 | VFP with 32 D-registers |

lpae | Large physical address extension (>4 GB physical memory on 32-bit architecture) |

evtstrm | Kernel event stream using generic architected timer |

crc32 | CRC-32 hardware accelerated support |

Execution Environment

Program execution context

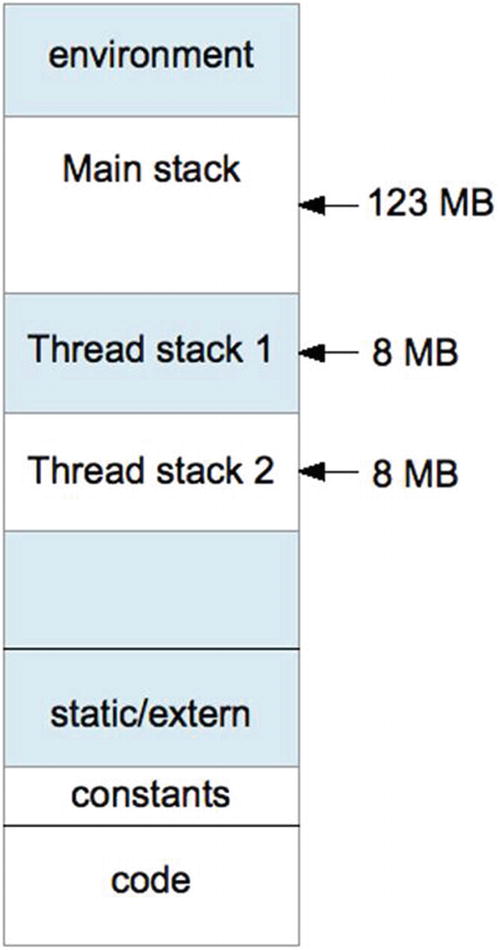

At the lowest end of the address space is the “text” region containing the program code. This region of virtual memory is read-only, holding read-only program constants in addition to executable code.

The next region (in increasing address) contains blocks of uninitialized arrays, buffers, static C variables, and extern storage.

At the high end of memory are environment variables for the program, like PATH. You can easily check this yourself by using getenv("PATH") and printing the returned address for it. Its address will likely be the highest address in your Raspberry Pi application, except possibly for another environment variable.

Below that, your main program’s stack begins and grows downward. Each function call causes a new stack frame to be created below the current one.

If you now add a thread to the program, a new stack has to be allocated for it. Experiments on the Pi show that the first thread stack gets created approximately 123 MB below the main stack’s beginning. A second thread has its stack allocated about 8 MB below the first. Each new thread’s stack (by default) is allocated 8 MB of stack space.

Dynamically allocated memory gets allocated from the heap, which sits between the static/extern region and the bottom end of the stack.

Threads

Every program gets one main thread of execution. But sometimes there is a need for the performance advantage of multiple threads, especially on a Pi with four cores.

pthread Headers

-lpthread

to link with the pthread library.

pthread Error Handling

The pthread routines return zero when they succeed and return an error code when they fail. The value errno is not used for these calls.

However, this approach doesn't work for threaded programs. Imagine two threads concurrently opening files with open(2), which set the errno value upon failure. Both threads cannot share the same int value for errno.

Rather than change a vast body of code already using errno in this manner, other approaches were implemented to provide each thread with its own private copy of errno. This is one reason that programs today using errno must include the header file errno.h. The header file takes care of defining the thread specific reference to errno.

Because the pthread standard was developing before the errno solution generally emerged, the pthread library returns the error code directly and returns zero when successful. If Unix were to be rewritten from scratch today, all system calls would probably work this way.

pthread_create(3)

thread: This first argument is simply a pointer to a pthread_t variable to receive the created thread’s ID value. The ID value allows you to query and control the created thread. If the call succeeds, the thread ID is returned to the calling program.

attr: This is a pointer to a pthread_attr_t attribute object that supplies various options and parameters. If you can accept the defaults, simply supply zero or NULL.

start_routine: As shown in the following code, this is simply the name of a start routine that accepts a void pointer and returns a void pointer.

arg: This generic pointer is passed to start_routine. It may point to anything of interest to the thread function (start_routine). Often this is a structure containing values, or in a C++ program, it can be the pointer to an object. If you don’t need an argument value, supply zero (or NULL).

returns: Zero is returned if the function is successful; otherwise, an error number is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EAGAIN | Insufficient resources to create another thread, or a system-imposed limit on the number of threads was encountered. |

EINVAL | Invalid settings in attr. |

EPERM | No permission to set the scheduling policy and parameters specified in attr. |

This example does not use thread attributes (argument 2 is zero). We also don’t care about the value passed into my_thread(), so argument 4 is provided a zero. Argument 3 simply needs to tell the system call what function to execute. The value of rc will be zero if the thread is successfully created (tested by the assert(3) macro).

At this point, the main thread and the function my_thread() execute in parallel. Since there is only one CPU on the Raspberry Pi, only one executes at any instant of time. But they both execute concurrently, trading blocks of execution time in a preemptive manner. Each, of course, runs using its own stack.

Thread my_thread() terminates gracefully, by returning.

pthread_attr_t

attr: Address of the pthread_attr_t variable to initialize/destroy

returns: Zero upon success, or an error code when it fails (not in errno)

Error | Description |

|---|---|

ENOMEM | Insufficient resources (memory) |

The Linux implementation of pthread_attr_init(3) may never return the ENOMEM error, but other Unix platforms might.

attr: The pointer to the attribute to fetch a value from, or to establish an attribute in.

stacksize: This is a stack size value when setting the attribute, and a pointer to the receiving size_t variable when fetching the stack size.

returns: Returns zero if the call is successful; otherwise, returns an error number (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The stack size is less than PTHREAD_STACK_MIN (16,384) bytes. |

On some systems, pthread_attr_setstacksize() can fail with the error EINVAL if stack size is not a multiple of the system page size.

The system default is provided by the initialization of attr. Then it is a matter of “getting” a value out of the attr object, and then putting in a new stack size in the call to pthread_attr_setstacksize().

pthread_join(3)

In the earlier pthread_create() example, the main program creates my_thread() and starts it executing. At some point, the main program is going to finish and want to exit (or return). If the main program exits before my_thread() completes, the entire process and the threads in it are destroyed, even if they have not completed.

thread: Thread ID of the thread to be joined with.

retval: Pointer to the void * variable to receive the returned value. If you are uninterested in a return value, this argument can be supplied with zero (or NULL).

returns: The function returns zero when successful; otherwise, an error number is returned (not in errno).

pthread_detach(3)

The function pthread_join(3) causes the caller to wait until the indicated thread returns. Sometimes, however, a thread is created and never checked again. When that thread exits, some of its resources are retained to allow for a join operation on it. If there is never going to be a join, it is better for that thread to be forgotten when it exits and have its resources immediately released.

thread: The thread ID of the thread to be altered, so that it will not wait for a join when it completes. Its resources will be immediately released upon the named thread’s termination.

returns: Zero if the call was successful; otherwise, an error code is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | Thread is not a joinable thread. |

ESRCH | No thread with the ID thread could be found. |

pthread_self(3)

pthread_kill(3)

thread: This is the thread ID that you want to signal (or test).

sig: This is the signal that you wish to send. Alternatively, supply zero to test whether the thread exists.

returns: Returns zero if the call is successful, or an error code (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | An invalid signal was specified. |

ESRCH | No thread with the ID thread could be found. |

One useful application of the pthread_kill(3) function is to test whether another thread exists. If the sig argument is supplied with zero, no actual signal is delivered, but the error checking is still performed. If the function returns zero, you know that the thread still exists.

But what does it mean when the thread exists? Does it mean that it is still executing? Or does it mean that it has not been reclaimed as part of a pthread_join(3), or as a consequence of pthread_detach(3) cleanup?

It turns out that when the thread exists, it means that it is still executing. In other words, it has not returned from the thread function that was started. If the thread has returned, it is considered to be incapable of receiving a signal.

Based on this, you know that you will get a zero returned when the thread is still executing. When error code ESRCH is returned instead, you know that the thread has completed.

Mutexes

While not strictly a CPU topic, mutexes are inseparable from a discussion about threads. A mutex is a locking device that allows the software designer to stop one or more threads while another is working with a shared resource. In other words, one thread receives exclusive access. This is necessary to facilitate inter-thread communication. I’m simply going to describe the mutex API here, rather than the theory behind the application of mutexes.

pthread_mutex_create(3)

mutex: A pointer to a pthread_mutex_t object, to be initialized.

attr: A pointer to a pthread_mutexattr_t object, describing mutex options. Supply zero (or NULL), if you can accept the defaults.

returns: Returns zero if the call is successful; otherwise, returns an error code (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EAGAIN | The system lacks the necessary resources (other than memory) to initialize another mutex. |

ENOMEM | Insufficient memory exists to initialize the mutex. |

EPERM | The caller does not have the privilege to perform the operation. |

EBUSY | The implementation has detected an attempt to reinitialize the object referenced by mutex, a previously initialized, but not yet destroyed, mutex. |

EINVAL | The value specified by attr is invalid. |

pthread_mutex_destroy(3)

mutex: The address of the mutex to release resources for.

returns: Returns zero when successful, or an error code when it fails (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EBUSY | Mutex is locked or in use in conjunction with a pthread_cond_wait(3) or pthread_cond_timedwait(3). |

EINVAL | The value specified by mutex is invalid. |

pthread_mutex_lock(3)

mutex: A pointer to the mutex to lock.

returns: Returns zero if the mutex was successfully locked; otherwise, an error code is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The mutex was created with the protocol attribute having the value PTHREAD_PRIO_PROTECT, and the calling thread’s priority is higher than the mutex’s current priority ceiling. Or the value specified by the mutex does not refer to an initialized mutex object. |

EAGAIN | Maximum number of recursive locks for mutex has been exceeded. |

EDEADLK | The current thread already owns the mutex. |

pthread_mutex_unlock(3)

mutex: A pointer to the mutex to be unlocked.

returns: Returns zero if the mutex was unlocked successfully; otherwise, an error code is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The value specified by mutex does not refer to an initialized mutex object. |

EPERM | The current thread does not own the mutex. |

Condition Variables

Sometimes mutexes alone are not enough for efficient scheduling of CPU between different threads. Mutexes and condition variables are often used together to facilitate inter-thread communication. New comers might struggle with this concept, at first.

Why do we need condition variables when we have mutexes?

Consider what is necessary in building a software queue that can hold a maximum of eight items. Before we can queue something, we need to first see if the queue is full. But we cannot test that until we have the queue locked—otherwise, another thread could be changing things under our own noses.

So we lock the queue but find that it is full. What do we do now? Do we simply unlock and try again? This works but it wastes CPU time. Wouldn’t it be better if we had some way of being alerted when the queue was no longer full?

- 1.

Lock the mutex. We cannot examine anything in the queue until we lock it.

- 2.Check the queue’s capacity. Can we place a new item in it? If so:

- a.

Place the new item in the queue.

- b.

Unlock and exit.

- a.

- 3.If the queue is full, the following steps are performed:

- a.

Using a condition variable, “wait” on it, with the associated mutex.

- b.

When control returns from the wait, return to step 2.

- a.

- 1.

The mutex is locked (1).

- 2.The wait is performed (3a). This causes the kernel to do the following:

- a.

Put the calling thread to sleep (put on a kernel wait queue).

- b.

Unlock the mutex that was locked in step 1.

- a.

Unlocking of the mutex in step 2b is necessary so that another thread can do something with the queue (hopefully, take an entry from the queue so that it is no longer full). If the mutex remained locked, no thread would be able to move.

- 1.

Lock the mutex.

- 2.

Find entries in the queue (it was currently full), and pull one item out of it.

- 3.

Unlock the mutex.

- 4.

Signal the condition variable that the “waiter” is using, so that it can wake up.

- 1.

The kernel makes the “waiting” thread ready.

- 2.

The mutex is successfully relocked.

Once that thread awakens with the mutex locked, it can recheck the queue to see whether there is room to queue an item. Notice that the thread is awakened only when it has already reacquired the mutex lock. This is why condition variables are paired with a mutex in their use.

pthread_cond_init(3)

cond: A pointer to the pthread_cond_t structure to be initialized.

attr: A pointer to a cond variable attribute if one is provided, or supply zero (or NULL).

returns: Zero is returned if the call is successful; otherwise, an error code is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EAGAIN | The system lacked the necessary resources. |

ENOMEM | Insufficient memory exists to initialize the condition variable. |

EBUSY | The implementation has detected an attempt to reinitialize the object referenced by cond, a previously initialized, but not yet destroyed, condition variable. |

EINVAL | The value specified by attr is invalid. |

pthread_cond_destroy(3)

cond: Condition variable to be released.

returns: Zero if the call was successful; otherwise, returns an error code (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EBUSY | Detected an attempt to destroy the object referenced by cond while it is referenced by pthread_cond_wait() or pthread_cond_timedwait() in another thread. |

EINVAL | The value specified by cond is invalid. |

pthread_cond_wait(3)

This function is one-half of the queue solution. The pthread_cond_wait(3) function is called with the mutex already locked. The kernel will then put the calling thread to sleep (on the wait queue) to release the CPU, while at the same time unlocking the mutex. The calling thread remains blocked until the condition variable cond is signaled in some way (more about that later).

cond: Pointer to the condition variable to be used for the wake-up call.

mutex: Pointer to the mutex to be associated with the condition variable.

returns: Returns zero upon success; otherwise, an error code is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The value specified by cond, mutex is invalid. Or different mutexes were supplied for concurrent pthread_cond_timedwait() or pthread_cond_wait() operations on the same condition variable. |

EPERM | The mutex was not owned by the current thread at the time of the call. |

The while loop retries the test to see whether the queue is “not full.” The while loop is necessary when multiple threads are inserting into the queue. Depending on timing, another thread could beat the current thread to queuing an item, making the queue full again.

pthread_cond_signal(3)

cond: A pointer to the condition variable used to signal one thread.

returns: Returns zero if the function call was successful; otherwise, an error number is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The value cond does not refer to an initialized condition variable. |

It is not an error if no other thread is waiting. This function does, however, wake up one waiting thread, if one or more are waiting on the specified condition variable.

This call is preferred for performance reasons if signaling one thread will “work.” When there are special conditions whereby some threads may succeed and others would not, you need a broadcast call instead. When it can be used, waking one thread saves CPU cycles.

pthread_cond_broadcast(3)

cond: A pointer to the condition variable to be signaled, waking all waiting threads.

returns: Zero is returned when the call is successful; otherwise, an error number is returned (not in errno).

Error | Description |

|---|---|

EINVAL | The value cond does not refer to an initialized condition variable. |

It is not an error to broadcast when there are no waiters.

Summary

This chapter has introduced the CPU as a resource to be exploited. The /proc/cpuinfo driver was described, which provides a quick summary of your CPU capabilities (and number of processors).

An introduction to ARM architecture was provided, allowing you to view architecture differs from implementation—that the BCM2837 is Broadcom’s implementation of the ARMv8-A architecture, for example. For the C programmer, the chapter finished with a whirlwind tour of the pthread API, as supported by Linux.