In this chapter, I put Angular in context within the world of web app development and set the foundation for the chapters that follow. The goal of Angular is to bring the tools and capabilities that have been available only for server-side development to the web client and, in doing so, make it easier to develop, test, and maintain rich and complex web applications.

Angular works by allowing you to extend HTML, which can seem like an odd idea until you get used to it. Angular applications express functionality through custom elements, and a complex application can produce an HTML document that contains a mix of standard and custom markup.

The style of development that Angular supports is derived through the use of the Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern, although this is sometimes referred to as Model-View-Whatever, since there are countless variations on this pattern that can be adhered to when using Angular. I am going to focus on the standard MVC pattern in this book since it is the most established and widely used. In the sections that follow, I explain the characteristics of projects where Angular can deliver significant benefit (and those where better alternatives exist), describe the MVC pattern, and describe some common pitfalls.

This Book and the Angular Release Schedule

Google has adopted an aggressive release schedule for Angular. This means that there is an ongoing stream of minor releases and a major release every six months. Minor releases should not break any existing features and should largely contain bug fixes. The major releases can contain substantial changes and may not offer backward compatibility.

It doesn’t seem fair or reasonable to ask readers to buy a new edition of this book every six months, especially since the majority of Angular features are unlikely to change even in a major release. Instead, I am going to post updates following the major releases to the GitHub repository for this book, https://github.com/Apress/pro-angular-6 .

This is an experiment for me (and for Apress), and I don’t yet know what form those updates may take—not least because I don’t know what the major releases of Angular will contain—but the goal is to extend the life of this book by supplementing the examples it contains.

I am not making any promises about what the updates will be like, what form they will take, or how long I will produce them before folding them into a new edition of this book. Please keep an open mind and check the repository for this book when new Angular versions are released. If you have ideas about how the updates could be improved as the experiment unfolds, then e-mail me at adam@adam-freeman.com and let me know.

Understanding Where Angular Excels

Angular isn’t the solution to every problem, and it is important to know when you should use Angular and when you should seek an alternative. Angular delivers the kind of functionality that used to be available only to server-side developers, but entirely in the browser. This means Angular has a lot of work to do each time an HTML document to which Angular has been applied is loaded—the HTML elements have to be compiled, the data bindings have to be evaluated, components and other building blocks need to be executed, and so on, building support for the features I described in Chapter 2 and those that I describe later in this book.

This kind of work takes time to perform, and the amount of time depends on the complexity of the HTML document, on the associated JavaScript code, and—critically—on quality of the browser and the processing capability of the device. You won’t notice any delay when using the latest browsers on a capable desktop machine, but old browsers on underpowered smartphones can really slow down the initial setup of an Angular app.

The goal, therefore, is to perform this setup as infrequently as possible and deliver as much of the app as possible to the user when it is performed. This means giving careful thought to the kind of web application you build. In broad terms, there are two kinds of web application: round-trip and single-page.

Understanding Round-Trip and Single-Page Applications

For a long time, web apps were developed to follow a round-trip model. The browser requests an initial HTML document from the server. User interactions—such as clicking a link or submitting a form—led the browser to request and receive a completely new HTML document. In this kind of application, the browser is essentially a rending engine for HTML content, and all of the application logic and data resides on the server. The browser makes a series of stateless HTTP requests that the server handles by generating HTML documents dynamically.

A lot of current web development is still for round-trip applications, not least because they require little from the browser, which ensures the widest possible client support. But there are some serious drawbacks to round-trip applications: they make the user wait while the next HTML document is requested and loaded, they require a large server-side infrastructure to process all the requests and manage all the application state, and they require a lot of bandwidth because each HTML document has to be self-contained (leading to a lot of the same content being included in each response from the server).

Single-page applications take a different approach. An initial HTML document is sent to the browser, but user interactions lead to Ajax requests for small fragments of HTML or data inserted into the existing set of elements being displayed to the user. The initial HTML document is never reloaded or replaced, and the user can continue to interact with the existing HTML while the Ajax requests are being performed asynchronously, even if that just means seeing a “data loading” message.

Most current apps fall somewhere between the extremes, tending to use the basic round-trip model enhanced with JavaScript to reduce the number of complete page changes, although the emphasis is often on reducing the number of form errors by performing client-side validation.

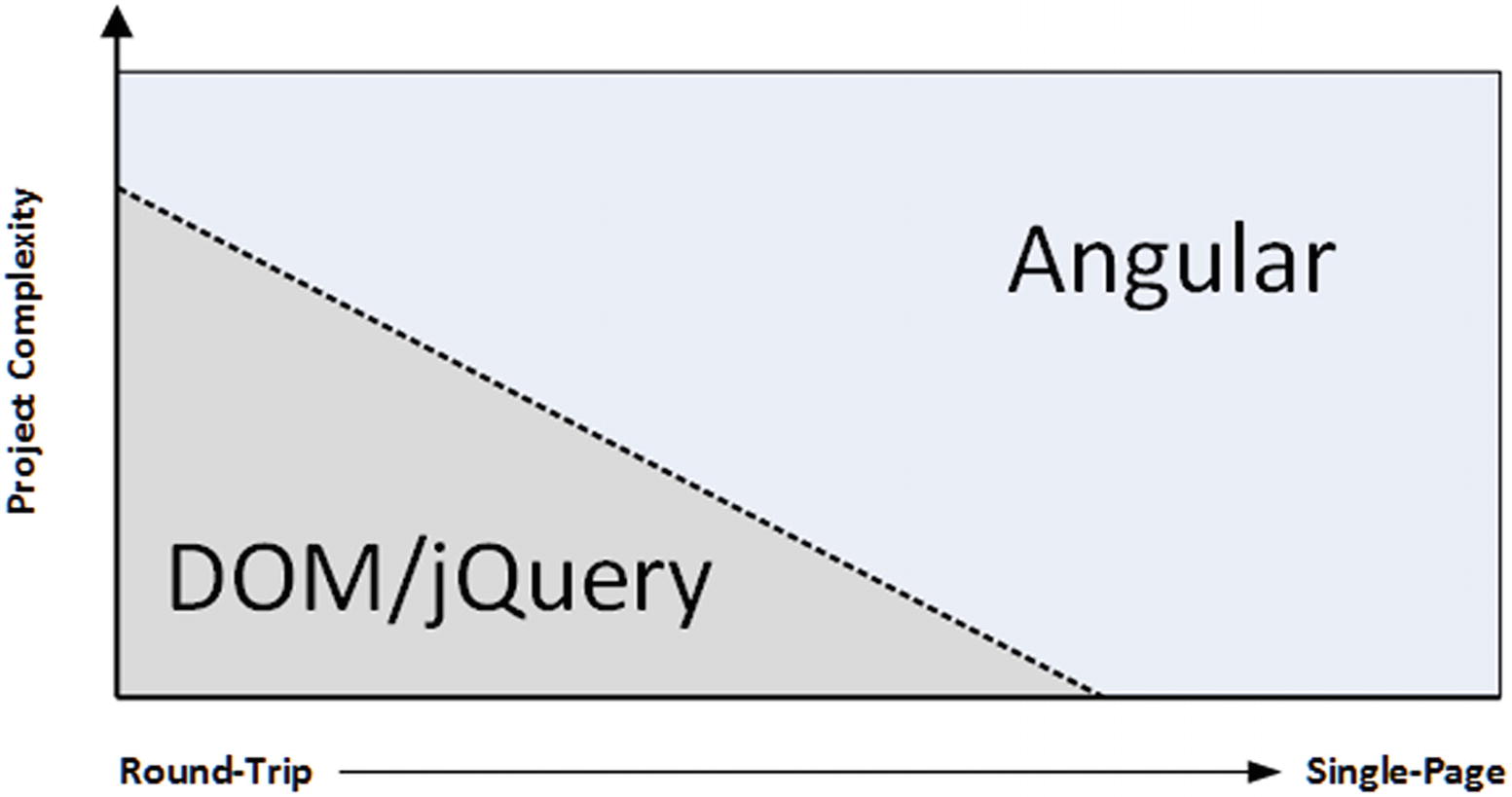

Angular is well-suited to single-page web apps

Angular excels in single-page applications and especially in complex round-trip applications. For simpler projects, using the DOM API directly or a library like jQuery is generally a better choice, although nothing prevents you from using Angular in all of your projects.

The single-page application model is the sweet spot for Angular, not just because of the initialization process but because the benefits of using the MVC pattern (which I describe later in this chapter) really start to manifest themselves in larger and more complex projects, which are the ones pushing toward the single-page model.

Tip

Another phrase you may encounter is progressive web applications (PWAs). Progressive applications continue to work even when disconnected from the network and have access to features such as push notifications. PWAs are not specific to Angular, but I demonstrate how to use simple PWA features in Chapter 10.

Comparing Angular to jQuery

Angular and jQuery take different approaches to web app development. jQuery is all about explicitly manipulating the browser’s Document Object Model (DOM) to create an application. The approach that Angular takes is to co-opt the browser into being the foundation for application development.

jQuery is, without any doubt, a powerful tool—and one I love to use. jQuery is robust and reliable, and you can get results pretty much immediately. I especially like the Fluid API and the ease with which you can extend the core jQuery library. But as much as I love jQuery, it isn’t the right tool for every job any more than Angular is. It can be hard to write and manage large applications using jQuery, and thorough unit testing can be a challenge.

Angular also uses the DOM to present HTML content to users but takes an entirely different path to building applications, focusing more on the data in the application and associating it to HTML elements through dynamic data bindings.

The main drawback of Angular is that there is an up-front investment in development time before you start to see results—something that is common in any MVC-based development. This initial investment is worthwhile, however, for complex apps or those that are likely to require significant revision and maintenance.

So, in short, use jQuery (or use the DOM API directly) for low-complexity web apps where unit testing isn’t critical and you require immediate results. Use Angular for single-page web apps, when you have time for careful design and planning and when you can easily control the HTML generated by the server.

Comparing Angular to React and Vue.js

There are two main competitors to Angular: React and Vue.js. There are some low-level differences between them, but, for the most part, all of these frameworks are excellent, all of them work in similar ways, and all of them can be used to create rich and fluid client-side applications.

The main difference between these frameworks is the developer experience. Angular requires you to use TypeScript to be effective, for example. If you are used to using a language like C# or Java, then TypeScript will be familiar and avoids dealing with some of the oddities of the JavaScript language. Vue.js and React don’t require TypeScript but lean toward mixing HTML, JavaScript, and CSS content together in a single file, which not everyone enjoys.

My advice is simple: pick the framework that you like the look of the most and switch to one of the others if you don’t get on with it. That may seem like an unscientific approach but there isn’t a bad choice to make, and you will find that many of the core concepts carry over between frameworks even if you switch.

Understanding the MVC Pattern

The term Model-View-Controller has been in use since the late 1970s and arose from the Smalltalk project at Xerox PARC where it was conceived as a way to organize some early GUI applications. Some of the fine detail of the original MVC pattern was tied to Smalltalk-specific concepts, such as screens and tools, but the broader ideas are still applicable to applications, and they are especially well-suited to web applications.

The MVC pattern first took hold in the server-side end of web development, through toolkits like Ruby on Rails and the ASP.NET MVC Framework. In recent years, the MVC pattern has been seen as a way to manage the growing richness and complexity of client-side web development as well, and it is in this environment that Angular has emerged.

The key to applying the MVC pattern is to implement the key premise of a separation of concerns, in which the data model in the application is decoupled from the business and presentation logic. In client-side web development, this means separating the data, the logic that operates on that data, and the HTML elements used to display the data. The result is a client-side application that is easier to develop, maintain, and test.

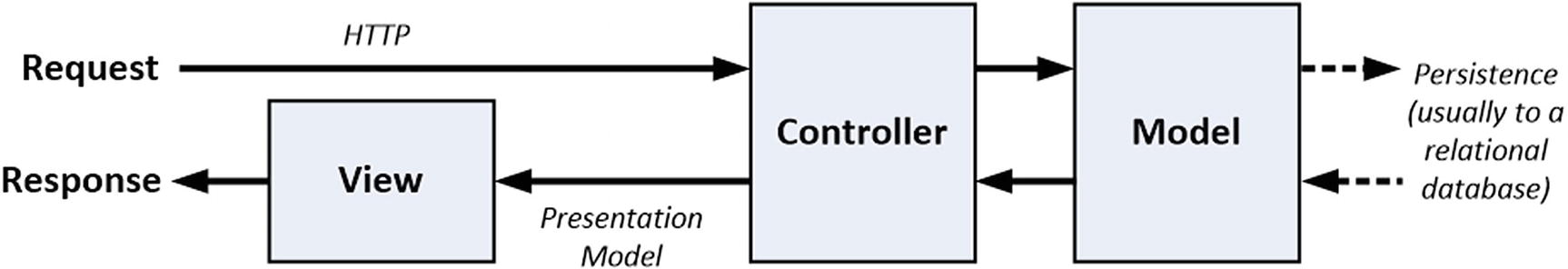

The server-side implementation of the MVC pattern

I took this figure from my Pro ASP.NET Core MVC 2 book, which describes Microsoft’s server-side implementation of the MVC pattern. You can see that the expectation is that the model is obtained from a database and that the goal of the application is to service HTTP requests from the browser. This is the basis for round-trip web apps, which I described earlier.

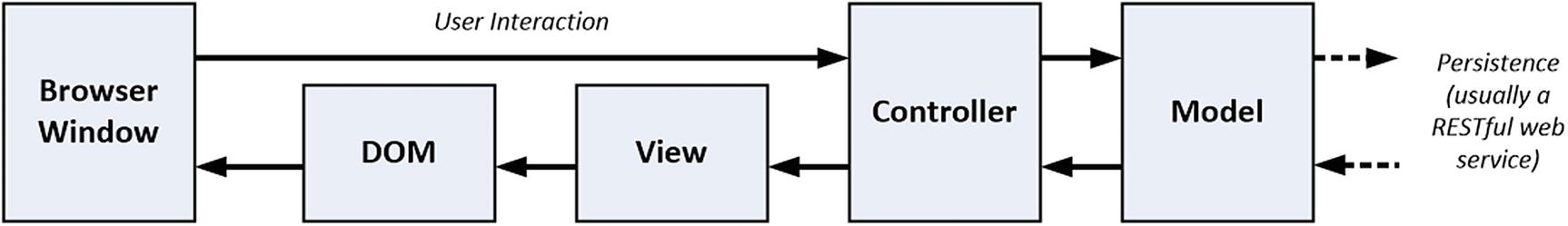

A client-side implementation of the MVC pattern

The client-side implementation of the MVC pattern gets its data from server-side components, usually via a RESTful web service, which I describe in Chapter 24. The goal of the controller and the view is to operate on the data in the model to perform DOM manipulation so as to create and manage HTML elements that the user can interact with. Those interactions are fed back to the controller, closing the loop to form an interactive application.

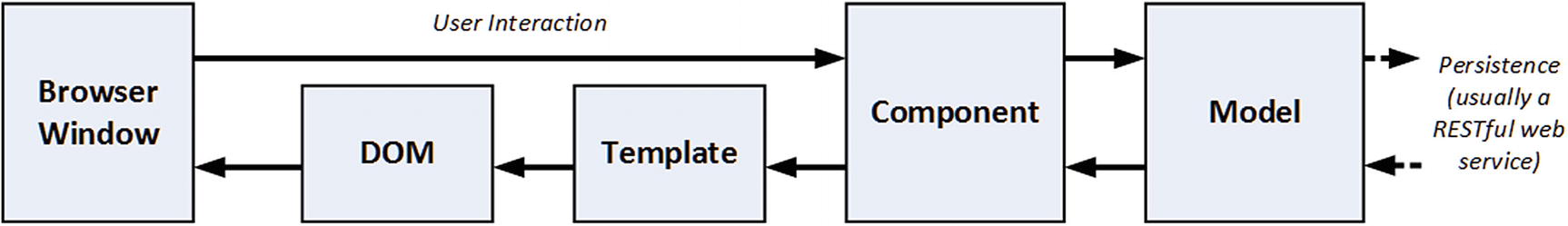

The Angular implementation of the MVC pattern

The figure shows the basic mapping of Angular building blocks to the MVC pattern. To support the MVC pattern, Angular provides a broad set of additional features, which I describe throughout the book.

Tip

Using a client-side framework like Angular doesn’t preclude using a server-side MVC framework, but you’ll find that an Angular client takes on some of the complexity that would have otherwise existed at the server. This is generally a good thing because it offloads work from the server to the client, and that allows for more clients to be supported with less server capacity.

Patterns and Pattern Zealots

A good pattern describes an approach to solving a problem that has worked for other people on other projects. Patterns are recipes, rather than rules, and you will need to adapt any pattern to suit your specific projects, just like a cook has to adapt a recipe to suit different ovens and ingredients.

The degree by which you depart from a pattern should be driven by need and experience. The time you have spent applying a pattern to similar projects will inform your knowledge about what does and doesn’t work for you. If you are new to a pattern or you are embarking on a new kind of project, then you should stick as closely as possible to the pattern until you truly understand the benefits and pitfalls that await you. Be careful not to reform your entire development effort around a pattern, however, since wide-sweeping disruption usually causes productivity losses that undermine whatever outcome you were hoping the pattern would give.

Patterns are flexible tools and not fixed rules, but not all developers understand the difference, and some become pattern zealots. These are the people who spend more time talking about the pattern than applying it to projects and consider any deviation from their interpretation of the pattern to be a serious crime. My advice is to simply ignore this kind of person because any kind of engagement will just suck the life out of you, and you’ll never be able to change their minds. Instead, just get on with some work and demonstrate how a flexible application of a pattern can produce good results through practical application and delivery.

With this in mind, you will see that I follow the broad concepts of the MVC pattern in the examples in this book but that I adapt the pattern to demonstrate different features and techniques. This is how I work in my own projects—embracing the parts of patterns that provide value and setting aside those that do not.

Understanding Models

Models—the M in MVC—contain the data that users work with. There are two broad types of model: view models, which represent just data passed from the component to the template, and domain models, which contain the data in a business domain, along with the operations, transformations, and rules for creating, storing, and manipulating that data, collectively referred to as the model logic.

Tip

Many developers new to the MVC pattern get confused with the idea of including logic in the data model, believing that the goal of the MVC pattern is to separate data from logic. This is a misapprehension: the goal of the MVC framework is to divide an application into three functional areas, each of which may contain both logic and data. The goal isn’t to eliminate logic from the model. Rather, it is to ensure that the model contains logic only for creating and managing the model data.

You can’t read a definition of the MVC pattern without tripping over the word business, which is unfortunate because a lot of web development goes far beyond the line-of-business applications that led to this kind of terminology. Business applications are still a big chunk of the development world, however, and if you are writing, say, a sales accounting system, then your business domain would encompass the process related to sales accounting, and your domain model would contain the accounts data and the logic by which accounts are created, stored, and managed. If you are creating a cat video website, then you still have a business domain; it is just that it might not fit within the structure of a corporation. Your domain model would contain the cat videos and the logic that will create, store, and manipulate those videos.

Contain the domain data

Contain the logic for creating, managing, and modifying the domain data (even if that means executing remote logic via web services)

Provide a clean API that exposes the model data and operations on it

Expose details of how the model data is obtained or managed (in other words, details of the data storage mechanism or the remote web service should not be exposed to controllers and views)

Contain logic that transforms the model based on user interaction (because this is the component’s job)

Contain logic for displaying data to the user (this is the template’s job)

The benefits of ensuring that the model is isolated from the controller and views are that you can test your logic more easily (I describe Angular unit testing in Chapter 29) and that enhancing and maintaining the overall application is simpler and easier.

The best domain models contain the logic for getting and storing data persistently and the logic for create, read, update, and delete operations (known collectively as CRUD) or separate models for querying and modifying data, known as the Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern.

This can mean the model contains the logic directly, but more often the model will contain the logic for calling RESTful web services to invoke server-side database operations (which I demonstrate in Chapter 8 when I build a realistic Angular application and which I describe in detail in Chapter 24).

Angular vs. AngularJS

The original AngularJS was popular but awkward to use and required developers to deal with some arcane and oddly implemented features that made web application development more complex than it needed to be. Angular, starting with Angular 2 and continuing to the Angular 6 release described in this book, is a complete rewrite that is easier to learn, is easier to work with, and is much more consistent. It is still a complex framework, as the size of this book shows, but creating web applications with Angular is a more pleasant experience than with AngularJS.

The differences between AngularJS and Angular are so profound that I have not included any migration details in this book. If you have an AngularJS application that you want to upgrade to Angular, then you can use the upgrade adapter, which allows code from both versions of the framework to coexist in the same application. See https://angular.io/guide/upgrade for details. This can ease the transition, although AngularJS and Angular are so different that my advice is to make a clean start and switch to Angular for a ground-up rewrite. This isn’t always possible, of course, especially for complex applications, but the process of migrating while also managing coexistence is a difficult one to master and can lead to problems that are hard to track down and correct.

Understanding Controllers/Components

Contain the logic required to set up the initial state of the template

Contain the logic/behaviors required by the template to present data from the model

Contain the logic/behaviors required to update the model based on user interaction

Contain logic that manipulates the DOM (that is the job of the template)

Contain logic that manages the persistence of data (that is the job of the model)

Understanding View Data

The domain model isn’t the only data in an Angular application. Components can create view data (also known as view model data or view models) to simplify templates and their interactions with the component.

Understanding Views/Templates

Contain the logic and markup required to present data to the user

Contain complex logic (this is better placed in a component or one of the other Angular building blocks, such as directives, services, or pipes)

Contain logic that creates, stores, or manipulates the domain model

Templates can contain logic, but it should be simple and used sparingly. Putting anything but the simplest method calls or expressions in a template makes the overall application harder to test and maintain.

Understanding RESTful Services

The logic for domain models in Angular apps is often split between the client and the server. The server contains the persistent store, typically a database, and contains the logic for managing it. In the case of a SQL database, for example, the required logic would include opening connections to the database server, executing SQL queries, and processing the results so they can be sent to the client.

You don’t want the client-side code accessing the data store directly—doing so would create a tight coupling between the client and the data store that would complicate unit testing and make it difficult to change the data store without also making changes to the client code.

By using the server to mediate access to the data store, you prevent tight coupling. The logic on the client is responsible for getting the data to and from the server and is unaware of the details of how that data is stored or accessed behind the scenes.

There are lots of ways of passing data between the client and the server. One of the most common is to use Asynchronous JavaScript and XML (Ajax) requests to call server-side code, getting the server to send JSON and making changes to data using HTML forms.

This approach can work well and is the foundation of RESTful web services, which use the nature of HTTP requests to perform CRUD operations on data.

Note

REST is a style of API rather than a well-defined specification, and there is disagreement about what exactly makes a web service RESTful. One point of contention is that purists do not consider web services that return JSON to be RESTful. Like any disagreement about an architectural pattern, the reasons for the disagreement are arbitrary and dull and not at all worth worrying about. As far as I am concerned, JSON services are RESTful, and I treat them as such in this book.

There is no standard URL specification for a RESTful web service, but the idea is to make the URL self-explanatory, such that it is obvious what the URL refers to. In this case, it is obvious that there is a collection of data objects called people and that the URL refers to the specific object within that collection whose identity is bob.

Tip

It isn’t always possible to create such self-evident URLs in a real project, but you should make a serious effort to keep things simple and not expose the internal structure of the data store through the URL (because this is just another kind of coupling between components). Keep your URLs as simple as possible and keep the mappings between the URL format and the structure of the data within the server.

The Operations Commonly Performed in Response to HTTP Methods

Method | Description |

|---|---|

GET | Retrieves the data object specified by the URL |

PUT | Updates the data object specified by the URL |

POST | Creates a new data object, typically using form data values as the data fields |

DELETE | Deletes the data object specified by the URL |

You don’t have to use the HTTP methods to perform the operations I describe in the table. A common variation is that the POST method is often used to serve double duty and will update an object if one exists and create one if not, meaning that the PUT method isn’t used. I describe the support that Angular provides for Ajax and for easily working with RESTful services in Chapter 24.

Idempotent HTTP Methods

You can implement any mapping between HTTP methods and operations on the data store, although I recommend you stick as closely as possible to the convention I describe in the table.

If you depart from the normal approach, make sure you honor the nature of the HTTP methods as defined in the HTTP specification. The GET method is nullipotent, which means the operations you perform in response to this method should only retrieve data and not modify it. A browser (or any intermediate device, such as a proxy) expects to be able to repeatedly make a GET request without altering the state of the server (although this doesn’t mean the state of the server won’t change between identical GET requests because of requests from other clients).

The PUT and DELETE methods are idempotent, which means that multiple identical requests should have the same effect as a single request. So, for example, using the DELETE method with the /people/bob URL should delete the bob object from the people collection for the first request and then do nothing for subsequent requests. (Again, of course, this won’t be true if another client re-creates the bob object.)

The POST method is neither nullipotent nor idempotent, which is why a common RESTful optimization is to handle object creation and updates. If there is no bob object, using the POST method will create one, and subsequent POST requests to the same URL will update the object that was created.

All of this is important only if you are implementing your own RESTful web service. If you are writing a client that consumes a RESTful service, then you just need to know what data operation each HTTP method corresponds to. I demonstrate consuming such a service in Chapter 8 and describe the Angular features for HTTP requests in more detail in Chapter 24.

Common Design Pitfalls

In this section, I describe the three most common design pitfalls that I encounter in Angular projects. These are not coding errors but rather problems with the overall shape of the web app that prevent the project team from getting the benefits that Angular and the MVC pattern can provide.

Putting the Logic in the Wrong Place

Putting business logic in templates, rather than in components

Putting domain logic in components, rather than in the model

Putting data store logic in the client model when using a RESTful service

These are tricky issues because they take a while to manifest themselves as problems. The application still runs, but it will become harder to enhance and maintain over time. In the case of the third variety, the problem will become apparent only when the data store is changed (which rarely happens until a project is mature and has grown beyond its initial user projections).

Tip

Getting a feel for where logic should go takes some experience, but you’ll spot problems earlier if you are using unit testing because the tests you have to write to cover the logic won’t fit nicely into the MVC pattern. I describe the Angular support for unit testing in Chapter 29.

Template logic should prepare data only for display and never modify the model.

Component logic should never directly create, update, or delete data from the model.

The templates and components should never directly access the data store.

If you keep these in mind as you develop, you’ll head off the most common problems.

Adopting the Data Store Data Format

The next problem arises when the development team builds an application that depends on the quirks of the server-side data store. In a well-designed Angular application that gets its data from a RESTful service, it is the job of the server to hide the data store implementation details and present the client with data in a suitable data format that favors simplicity in the client. Decide how the client needs to represent dates, for example, and then ensure you use that format within the data store—and if the data store can’t support that format natively, then it is the job of the server to perform the translation.

Just Enough Knowledge to Cause Trouble

Angular is a complex framework that can be bewildering until you get used it. There are lots of different building blocks available, and they can be combined in different ways to achieve similar results. This makes Angular development flexible and means you will develop your own style of problem-solving by creating combinations of features that suit your project and working style.

Becoming proficient in Angular takes time. The temptation is to jump into creating your own projects before understanding how the different parts of Angular fit together. You might produce something that works without really understanding why it works, and that’s a recipe for disaster when you need to make changes. My advice is to go slow and take the time to understand all the features that Angular provides. By all means, start creating projects early, but make sure you really understand how they work and be prepared to make changes as you find better ways of achieving the results you require.

Summary

In this chapter, I provided some context for Angular. I explained how Angular supports the MVC pattern for app development, and I gave a brief overview of REST and how it is used to express data operations over HTTP requests. I finished the chapter by describing the three most common design problems in Angular projects. In the next chapter, I provide a quick primer for HTML and the Bootstrap CSS framework that I use for examples throughout this book.