Chapter 3

Activities, Fragments, and Intents

An Android application can have zero or more activities. Typically, applications have one or more activities. The main purpose of an activity is to interact with the user. From the moment an activity appears on the screen to the moment it is hidden, it goes through a number of stages. These stages are known as an activity's life cycle. Understanding the life cycle of an activity is vital to ensuring that your application works correctly. In addition to activities, Android N also supports fragments, a feature that was introduced for tablets in Android 3.0 and for phones in Android 4.0. Think of fragments as “miniature” activities that can be grouped to form an activity. In this chapter, you find out how activities and fragments work together.

Apart from activities, another unique concept in Android is that of an intent. An intent is basically the “glue” that enables activities from different applications to work together seamlessly, ensuring that tasks can be performed as though they all belong to one single application. Later in this chapter, you learn more about this very important concept and how you can use it to call built-in applications such as the Browser, Phone, Maps, and more.

UNDERSTANDING ACTIVITIES

This chapter begins by showing you how to create an activity. To create an activity, you create a Java class that extends the Activity base class:

package com.jfdimarzio.chapter1helloworld;

import android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivity;

import android.os.Bundle;

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

}

}Your activity class loads its user interface (UI) component using the XML file defined in your res/layout folder. In this example, you would load the UI from the main.xml file:

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);Every activity you have in your application must be declared in your AndroidManifest.xml file, like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android

package="com.jfdimarzio.chapter1helloworld">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@style/AppTheme">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

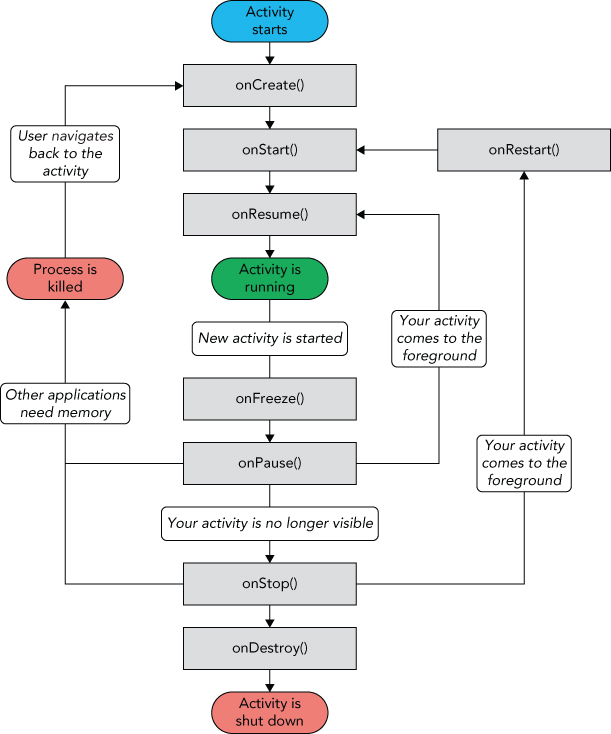

</manifest>The Activity base class defines a series of events that govern the life cycle of an activity. Figure 3.1 shows the lifecycle of an Activity.

The Activity class defines the following events:

onCreate()—Called when the activity is first createdonStart()—Called when the activity becomes visible to the useronResume()—Called when the activity starts interacting with the useronPause()—Called when the current activity is being paused and the previous activity is being resumedonStop()—Called when the activity is no longer visible to the useronDestroy()—Called before the activity is destroyed by the system (either manually or by the system to conserve memory)onRestart()—Called when the activity has been stopped and is restarting again

By default, the activity created for you contains the onCreate() event. Within this event handler is the code that helps to display the UI elements of your screen.

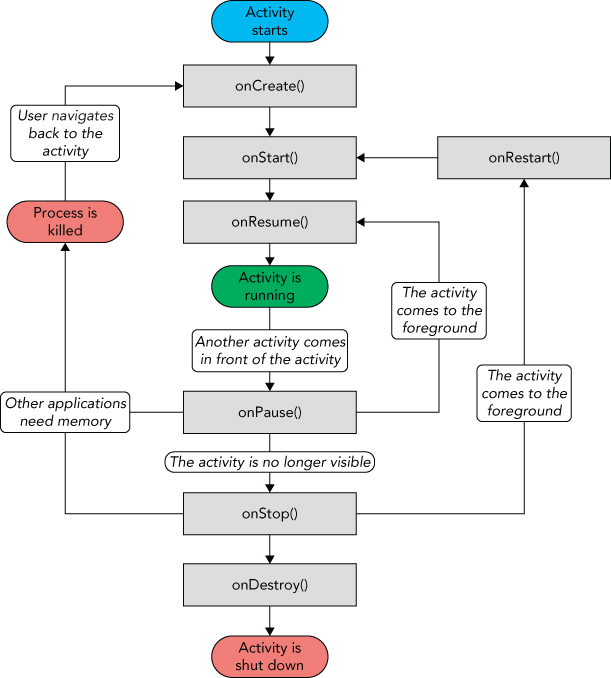

Figure 3.2 shows the life cycle of an activity and the various stages it goes through—from when the activity is started until it ends.

The best way to understand the various stages of an activity is to create a new project, implement the various events, and then subject the activity to various user interactions.

Applying Styles and Themes to an Activity

By default, an activity is themed to the default Android theme. However, there has been a push in recent years to adopt a new theme known as Material. The Material theme has a much more modern and clean look to it.

There are two versions of the Material theme available to Android developers: Material Light and Material Dark. Either of these themes can be applied from the AndroidManifest.xml.

To apply one of the Material themes to an activity, simply modify the <Application> element in the AndroidManifest.xml file by changing the default android:theme attribute. (Please be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.)

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

package="com.jfdimarzio.activity101">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@android:style/Theme.Material">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

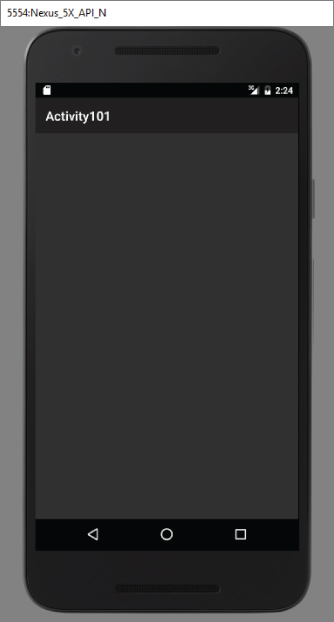

</manifest>Changing the default theme to @android:style/Theme.Material, as in the highlighted code in the preceding snippet, applies the Material Dark theme and gives your application a darker look as shown in Figure 3.4.

Hiding the Activity Title

You can also hide the title of an activity if desired (such as when you just want to display a status update to the user). To do so, use the requestWindowFeature() method and pass it the Window.FEATURE_NO_TITLE constant, like this:

import android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.Window;

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

requestWindowFeature(Window.FEATURE_NO_TITLE);

}

}Now you need to change the theme in the AndroidManifest.xml to a theme that has no title bar. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.

package com.jfdimarzio.activity101;

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

package="com.jfdimarzio.activity101">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@android:style/Theme.NoTitleBar">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

</manifest>This hides the title bar, as shown in Figure 3.5.

Displaying a Dialog Window

There are times when you need to display a dialog window to get a confirmation from the user. In this case, you can override the onCreateDialog() protected method defined in the Activity base class to display a dialog window. The following Try It Out shows you how.

Displaying a Progress Dialog

One common UI feature in an Android device is the “Please wait” dialog that you typically see when an application is performing a long-running task. For example, the application might be logging in to a server before the user is allowed to use it, or it might be doing a calculation before displaying the result to the user. In such cases, it is helpful to display a dialog, known as a progress dialog, so that the user is kept in the loop.

Android provides a ProgressDialog class you can call when you want to display a running meter to the user. ProgressDialog is easy to call from an activity.

The following Try It Out demonstrates how to display such a dialog.

The next section explains using Intents, which help you navigate between multiple Activities.

LINKING ACTIVITIES USING INTENTS

An Android application can contain zero or more activities. When your application has more than one activity, you often need to navigate from one to another. In Android, you navigate between activities through what is known as an intent.

The best way to understand this very important but somewhat abstract concept is to experience it firsthand and see what it helps you achieve. The following Try It Out shows how to add another activity to an existing project and then navigate between the two activities.

Returning Results from an Intent

The startActivity() method invokes another activity but does not return a result to the current activity. For example, you might have an activity that prompts the user for username and password. The information entered by the user in that activity needs to be passed back to the calling activity for further processing. If you need to pass data back from an activity, you should instead use the startActivityForResult() method. The following Try It Out demonstrates this.

Passing Data Using an Intent Object

Besides returning data from an activity, it is also common to pass data to an activity. For example, in the previous example, you might want to set some default text in the EditText view before the activity is displayed. In this case, you can use the Intent object to pass the data to the target activity.

The following Try It Out shows you the various ways in which you can pass data between activities.

TRY IT OUT

Passing Data to the Target Activity

- Using Eclipse, create a new Android project and name it PassingData.

- Add the bolded statements in the following code to the

activity_main.xmlfile. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.MainActivity"><Buttonandroid:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Click to go to Second Activity"android:id="@+id/button"android:onClick="onClick"/></LinearLayout> - Add a new XML file to the

res/layoutfolder and name it activity_second.xml. Populate it as follows:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical" xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.MainActivity"> <TextView android:layout_width="wrap_content" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="Welcome to the Second Activity" android:id="@+id/textView"/> <Button android:layout_width="wrap_content" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="Click to go to Main Activity" android:id="@+id/button" android:onClick="onClick"/> </LinearLayout> - Add a new

Classfile to the package and name it SecondActivity. Populate theSecondActivity.javafile as follows:package com.jfdimarzio.passingdata; import android.app.Activity; import android.content.Intent; import android.net.Uri; import android.os.Bundle; import android.view.View; import android.widget.Toast; public class SecondActvity extends Activity { @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); setContentView(R.layout.activity_second); //---get the data passed in using getStringExtra()--- Toast.makeText(this,getIntent().getStringExtra("str1"), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); //---get the data passed in using getIntExtra()--- Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString( getIntent().getIntExtra("age1", 0)), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); //---get the Bundle object passed in--- Bundle bundle = getIntent().getExtras(); //---get the data using the getString()--- Toast.makeText(this, bundle.getString("str2"), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); //---get the data using the getInt() method--- Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(bundle.getInt("age2")), Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); } public void onClick(View view) { //---use an Intent object to return data--- Intent i = new Intent(); //---use the putExtra() method to return some // value--- i.putExtra("age3", 45); //---use the setData() method to return some value--- i.setData(Uri.parse("Something passed back to main activity")); //---set the result with OK and the Intent object--- setResult(RESULT_OK, i); //---destroy the current activity--- finish(); } } - Add the bolded statements from the following code to the

AndroidManifest.xmlfile:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" package="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata"> <application android:allowBackup="true" android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher" android:label="@string/app_name" android:supportsRtl="true" android:theme="@style/AppTheme"> <activity android:name=".MainActivity"> <intent-filter> <action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/> <category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/> </intent-filter> </activity><activity android:name=".SecondActvity" ><intent-filter ><action android:name="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.SecondActivity" /><category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" /></intent-filter></activity></application> </manifest> - Add the bolded statements from the following code to the

MainActivity.javafile:package com.jfdimarzio.passingdata; import android.content.Intent;import android.Activity;import android.os.Bundle;import android.view.View;import android.widget.Toast;public class MainActivityextends Activity{ @Override protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); setContentView(R.layout.activity_main); }public void onClick(View view) {Intent i = newIntent("com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.SecondActivity");//---use putExtra() to add new name/value pairs---i.putExtra("str1", "This is a string");i.putExtra("age1", 25);//---use a Bundle object to add new name/values// pairs---Bundle extras = new Bundle();extras.putString("str2", "This is another string");extras.putInt("age2", 35);//---attach the Bundle object to the Intent object---i.putExtras(extras);//---start the activity to get a result back---startActivityForResult(i, 1);}public void onActivityResult(int requestCode,int resultCode, Intent data){//---check if the request code is 1---if (requestCode == 1) {//---if the result is OK---if (resultCode == RESULT_OK) {//---get the result using getIntExtra()---Toast.makeText(this, Integer.toString(data.getIntExtra("age3", 0)),Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();//---get the result using getData()---Toast.makeText(this, data.getData().toString(),Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();}}}} - 7. Press Shift+F9 to debug the application on the Android emulator. Click the button on each activity and observe the values displayed.

How It Works

While this application is not visually exciting, it does illustrate some important ways to pass data between activities.

First, you can use the putExtra() method of an Intent object to add a name/value pair:

//---use putExtra() to add new name/value pairs---

i.putExtra("str1", "This is a string");

i.putExtra("age1", 25);The preceding statements add two name/value pairs to the Intent object: one of type string and one of type integer.

Besides using the putExtra() method, you can also create a Bundle object and then attach it using the putExtras() method. Think of a Bundle object as a dictionary object—it contains a set of name/value pairs. The following statements create a Bundle object and then add two name/value pairs to it. The Bundle object is then attached to the Intent object:

//---use a Bundle object to add new name/values pairs---

Bundle extras = new Bundle();

extras.putString("str2", "This is another string");

extras.putInt("age2", 35);

//---attach the Bundle object to the Intent object---

i.putExtras(extras); To obtain the data sent using the Intent object, you first obtain the Intent object using the getIntent() method. Then, call its getStringExtra() method to get the string value set using the putExtra() method:

//---get the data passed in using getStringExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,getIntent().getStringExtra("str1"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();In this case, you have to call the appropriate method to extract the name/value pair based on the type of data set. For the integer value, use the getIntExtra() method (the second argument is the default value in case no value is stored in the specified name):

//---get the data passed in using getIntExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(

getIntent().getIntExtra("age1", 0)),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); To retrieve the Bundle object, use the getExtras() method:

//---get the Bundle object passed in---

Bundle bundle = getIntent().getExtras();To get the individual name/value pairs, use the appropriate method. For the string value, use the getString() method:

//---get the data using the getString()---

Toast.makeText(this, bundle.getString("str2"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();Likewise, use the getInt() method to retrieve an integer value:

//---get the data using the getInt() method---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(bundle.getInt("age2")),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();Another way to pass data to an activity is to use the setData() method (as used in the previous section), like this:

//---use the setData() method to return some value---

i.setData(Uri.parse(

"Something passed back to main activity"));Usually, you use the setData() method to set the data on which an Intent object is going to operate, such as passing a URL to an Intent object so that it can invoke a web browser to view a web page. (For more examples, see the section “Calling Built-In Applications Using Intents,” later in this chapter.)

To retrieve the data set using the setData() method, use the getData() method (in this example data is an Intent object):

//---get the result using getData()---

Toast.makeText(this, data.getData().toString(),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();FRAGMENTS

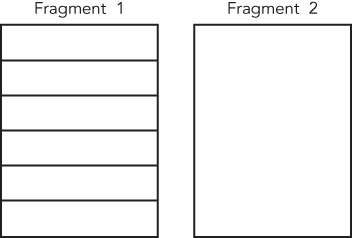

In the previous section, you learned what an activity is and how to use it. In a small-screen device (such as a smartphone), an activity typically fills the entire screen, displaying the various views that make up the user interface of an application. The activity is essentially a container for views. However, when an activity is displayed in a large-screen device, such as on a tablet, it is somewhat out of place. Because the screen is much bigger, all the views in an activity must be arranged to make full use of the increased space, resulting in complex changes to the view hierarchy. A better approach is to have “mini-activities,” each containing its own set of views. During runtime, an activity can contain one or more of these mini-activities, depending on the screen orientation in which the device is held. In Android 3.0 and later, these mini-activities are known as fragments.

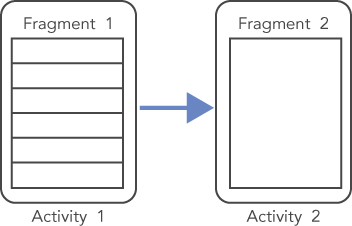

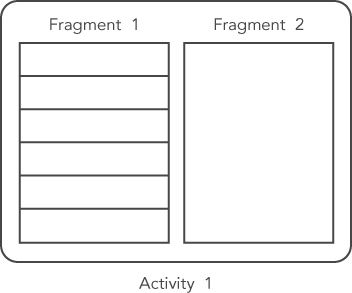

Think of a fragment as another form of activity. You create fragments to contain views, just like activities. Fragments are always embedded in an activity. For example, Figure 3.13 shows two fragments. Fragment 1 might contain a ListView showing a list of book titles. Fragment 2 might contain some TextViews and ImageViews showing some text and images.

Now imagine the application is running on an Android tablet (or on an Android smartphone) in portrait mode. In this case, Fragment 1 might be embedded in one activity, whereas Fragment 2 might be embedded in another activity (see Figure 3.14). When users select an item in the list in Fragment 1, Activity 2 is started.

If the application is now displayed in a tablet in landscape mode, both fragments can be embedded within a single activity, as shown in Figure 3.15.

From this discussion, it becomes apparent that fragments present a versatile way in which you can create the user interface of an Android application. Fragments form the atomic unit of your user interface, and they can be dynamically added (or removed) to activities in order to create the best user experience possible for the target device.

The following Try It Out shows you the basics of working with fragments.

TRY IT OUT

Using Fragments (Fragments.zip)

- Using Android Studio, create a new Android project and name it Fragments.

- In the

res/layoutfolder, add a new layout resource file and name itfragment1.xml. Populate it with the following code. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="fill_parent" android:background="#00FF00" > <TextView android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="This is fragment #1" android:textColor="#000000" android:textSize="25sp"/> </LinearLayout> - Also in the

res/layoutfolder, add another new layout resource file and name itfragment2.xml. Populate it as follows:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="fill_parent" android:background="#FFFE00" > <TextView android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="This is fragment #2" android:textColor="#000000" android:textSize="25sp"/> </LinearLayout> - In

activity_main.xml, add the bolded lines in the following code:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical" xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity"><fragmentandroid:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"android:id="@+id/fragment1"android:layout_weight="1"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="match_parent" /><fragmentandroid:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"android:id="@+id/fragment2"android:layout_weight="1"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="match_parent" /></LinearLayout> - Under the

<Your Package Name>/fragmentspackage name, add two Java class files and name themFragment1.javaandFragment2.java. - Add the following code to

Fragment1.java:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments; import android.app.Fragment; import android.os.Bundle; import android.view.LayoutInflater; import android.view.View; import android.view.ViewGroup; public class Fragment1 extends Fragment { @Override public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) { //---Inflate the layout for this fragment--- return inflater.inflate( R.layout.fragment1, container, false); } } - Add the following code to

Fragment2.java:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments; import android.app.Fragment; import android.os.Bundle; import android.view.LayoutInflater; import android.view.View; import android.view.ViewGroup; public class Fragment2 extends Fragment { @Override public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) { //---Inflate the layout for this fragment--- return inflater.inflate( R.layout.fragment2, container, false); } } - Press Shift+F9 to debug the application on the Android emulator. Figure 3.16 shows the two fragments contained within the activity.

How It Works

A fragment behaves very much like an activity: It has a Java class and it loads its UI from an XML file. The XML file contains all the usual UI elements that you expect from an activity: TextView, EditText, Button, and so on. The Java class for a fragment needs to extend the Fragment base class:

public class Fragment1 extends Fragment {

}NOTE

Besides the Fragment base class, a fragment can also extend a few other subclasses of the Fragment class, such as DialogFragment, ListFragment, and PreferenceFragment. Chapter 6 discusses these types of fragments in more detail.

To draw the UI for a fragment, you override the onCreateView() method. This method needs to return a View object, like this:

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater,

ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {

//---Inflate the layout for this fragment---

return inflater.inflate(

R.layout.fragment1, container, false);

}

Here, you use a LayoutInflater object to inflate the UI from the

specified XML file (R.layout.fragment1 in this case). The

container argument refers to the parent ViewGroup, which

is the activity in which you are trying to embed the

fragment. The savedInstanceState argument enables you

to restore the fragment to its previously saved state.

To add a fragment to an activity, you use the <fragment> element:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res

/android"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:orientation="vertical" >

<fragment

android:name=" com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"

android:id="@+id/fragment1"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

<fragment

android:name=" com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"

android:id="@+id/fragment2"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

</LinearLayout>Note that each fragment needs a unique identifier. You can assign one via the android:id or android:tag attribute.

Adding Fragments Dynamically

Although fragments enable you to compartmentalize your UI into various configurable parts, the real power of fragments is realized when you add them dynamically to activities during runtime. In the previous section, you saw how you can add fragments to an activity by modifying the XML file during design time. In reality, it is much more useful if you create fragments and add them to activities during runtime. This enables you to create a customizable user interface for your application. For example, if the application is running on a smartphone, you might fill an activity with a single fragment; if the application is running on a tablet, you might then fill the activity with two or more fragments, as the tablet has much more screen real estate compared to a smartphone.

The following Try It Out shows how you can programmatically add fragments to an activity during runtime.

TRY IT OUT

Adding Fragments During Runtime

- Using the same project created in the previous section, modify the

main.xmlfile by commenting out the two<fragment>elements. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical" xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity"><!--<fragment android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1" android:id="@+id/fragment1" android:layout_weight="1" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent"/> <fragment android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2" android:id="@+id/fragment2" android:layout_weight="1" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent"/>--></LinearLayout> - Add the bolded lines in the following code to the

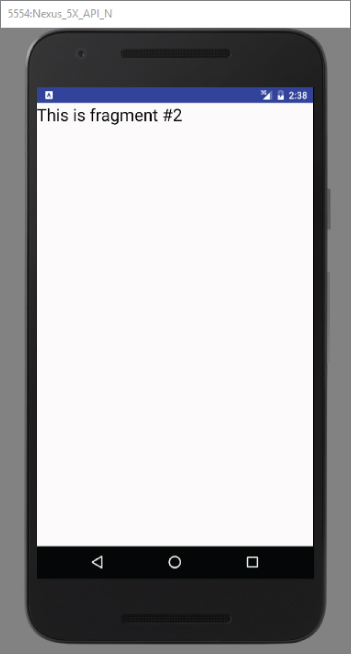

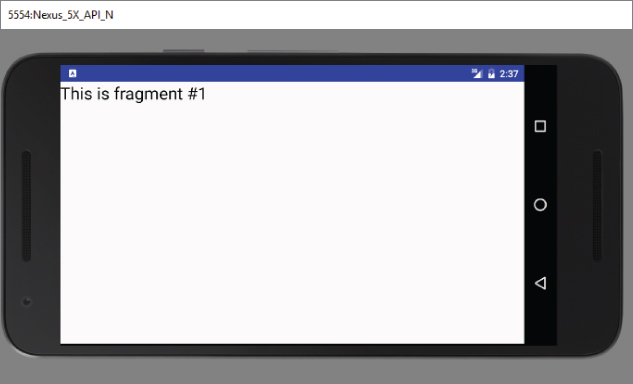

MainActivity.javafile:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments; import android.app.Activity;import android.app.FragmentManager;import android.app.FragmentTransaction;import android.os.Bundle;import android.util.DisplayMetrics;public class MainActivity extends Activity { /** Called when the activity is first created. */ @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager();FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction =fragmentManager.beginTransaction();//---get the current display info---DisplayMetrics display = this.getResources().getDisplayMetrics();int width = display.widthPixels;int height = display.heightPixels;if (width> height){//---landscape mode---Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();// android.R.id.content refers to the content// view of the activityfragmentTransaction.replace(android.R.id.content, fragment1);}else{//---portrait mode---Fragment2 fragment2 = new Fragment2();fragmentTransaction.replace(android.R.id.content, fragment2);}fragmentTransaction.commit();} } - Press Shift + F9 to run the application on the Android emulator. Observe that when the emulator is in portrait mode, Fragment 2 is displayed (see Figure 3.17). If you press Ctrl+Left to change the orientation of the emulator to landscape, Fragment 1 is shown instead (see Figure 3.18).

How It Works

To add fragments to an activity, you use the FragmentManager class by first obtaining an instance of it:

FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager();You also need to use the FragmentTransaction class to perform fragment transactions (such as add, remove, or replace) in your activity:

FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction =

fragmentManager.beginTransaction(); In this example, the WindowManager is used to determine whether the device is currently in portrait mode or landscape mode. Once that is determined, you can add the appropriate fragment to the activity by creating the fragment. Next, you call the replace() method of the FragmentTransaction object to add the fragment to the specified view container. In this case, android.R.id.content refers to the content view of the activity.

//---landscape mode---

Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();

// android.R.id.content refers to the content

// view of the activity

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment1);Using the replace() method is essentially the same as calling the remove() method followed by the add() method of the FragmentTransaction object. To ensure that the changes take effect, you need to call the commit() method:

fragmentTransaction.commit(); Life Cycle of a Fragment

Like activities, fragments have their own life cycle. Understanding the life cycle of a fragment enables you to properly save an instance of the fragment when it is destroyed, and restore it to its previous state when it is re-created.

The following Try It Out examines the various states experienced by a fragment.

TRY IT OUT

Understanding the Life Cycle of a Fragment (Fragments.zip)

- Using the same project created in the previous section, add the following bolded code to the

Fragment1.javafile. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using.package com.jfdimarzio.fragments; import android.app.Activity; import android.app.Fragment; import android.os.Bundle;import android.util.Log;import android.view.LayoutInflater; import android.view.View; import android.view.ViewGroup; public class Fragment1 extends Fragment { @Override public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {Log.d("Fragment 1", "onCreateView");//---Inflate the layout for this fragment--- return inflater.inflate( R.layout.fragment1, container, false); }@Overridepublic void onAttach(Activity activity) {super.onAttach(activity);Log.d("Fragment 1", "onAttach");}@Overridepublic void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);Log.d("Fragment 1", "onCreate");}@Overridepublic void onActivityCreated(Bundle savedInstanceState) {super.onActivityCreated(savedInstanceState);Log.d("Fragment 1", "onActivityCreated");}@Overridepublic void onStart() {super.onStart();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onStart");}@Overridepublic void onResume() {super.onResume();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onResume");}@Overridepublic void onPause() {super.onPause();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onPause");}@Overridepublic void onStop() {super.onStop();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onStop");}@Overridepublic void onDestroyView() {super.onDestroyView();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDestroyView");}@Overridepublic void onDestroy() {super.onDestroy();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDestroy");}@Overridepublic void onDetach() {super.onDetach();Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDetach");}} - Switch the Android emulator to landscape mode by pressing Ctrl+Left.

- Press Shift+F9 in Android Studio to debug the application on the Android emulator.

- When the application is loaded on the emulator, the following is displayed in the logcat console in Android Monitor:

12-09 04:17:43.436: D/Fragment 1(2995): onAttach 12-09 04:17:43.466: D/Fragment 1(2995): onCreate 12-09 04:17:43.476: D/Fragment 1(2995): onCreateView 12-09 04:17:43.506: D/Fragment 1(2995): onActivityCreated 12-09 04:17:43.506: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStart 12-09 04:17:43.537: D/Fragment 1(2995): onResume - Click the Home button on the emulator. The following output is displayed in the logcat console:

12-09 04:18:47.696: D/Fragment 1(2995): onPause 12-09 04:18:50.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStop - On the emulator, click the Home button and hold it. Launch the application again. This time, the following is displayed:

12-09 04:20:08.726: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStart 12-09 04:20:08.766: D/Fragment 1(2995): onResume - Click the Back button on the emulator. Now you should see the following output:

12-09 04:21:01.426: D/Fragment 1(2995): onPause 12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStop 12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDestroyView 12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDestroy 12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDetach

How It Works

Like activities, fragments in Android also have their own life cycle. As you have seen, when a fragment is being created, it goes through the following states:

onAttach()onCreate()onCreateView()onActivityCreated()

When the fragment becomes visible, it goes through these states:

onStart()onResume()

When the fragment goes into the background mode, it goes through these states:

onPause()onStop()

When the fragment is destroyed (when the activity in which it is currently hosted is destroyed), it goes through the following states:

onPause()onStop()onDestroyView()onDestroy()onDetach()

Like activities, you can restore an instance of a fragment using a Bundle object, in the following states:

onCreate()onCreateView()onActivityCreated()

Most of the states experienced by a fragment are similar to those of activities. However, a few new states are specific to fragments:

onAttached()—Called when the fragment has been associated with the activityonCreateView()Called to create the view for the fragmentonActivityCreated()—Called when the activity'sonCreate()method has been returnedonDestroyView()—Called when the fragment's view is being removedonDetach()—Called when the fragment is detached from the activity

One of the main differences between activities and fragments is when an activity goes into the background, the activity is placed in the back stack. This allows the activity to be resumed when the user presses the Back button. In the case of fragments, however, they are not automatically placed in the back stack when they go into the background. Rather, to place a fragment into the back stack, you need to explicitly call the addToBackStack() method during a fragment transaction, like this:

//---get the current display info---

DisplayMetrics display = this.getResources().getDisplayMetrics();

int width = display.widthPixels;

int height = display.heightPixels;

if (width> height)

{

//---landscape mode---

Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();

// android.R.id.content refers to the content

// view of the activity

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment1);

}

else

{

//---portrait mode---

Fragment2 fragment2 = new Fragment2();

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment2);

}

//---add to the back stack---

fragmentTransaction.addToBackStack(null);

fragmentTransaction.commit(); The preceding code ensures that after the fragment has been added to the activity, the user can click the Back button to remove it.

Interactions Between Fragments

Very often, an activity might contain one or more fragments working together to present a coherent UI to the user. In this case, it is important for fragments to communicate with one another and exchange data. For example, one fragment might contain a list of items (such as postings from an RSS feed). Also, when the user taps on an item in that fragment, details about the selected item might be displayed in another fragment.

The following Try It Out shows how one fragment can access the views contained within another fragment.

TRY IT OUT

Communication Between Fragments

- Using the same project created in the previous section, add the following bolded statement to the

Fragment1.xmlfile. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="fill_parent" android:background="#00FF00" > <TextViewandroid:id="@+id/lblFragment1"android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="This is fragment #1" android:textColor="#000000" android:textSize="25sp"/> </LinearLayout> - Add the following bolded lines to

fragment2.xml:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="fill_parent" android:background="#FFFE00" > <TextView android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="wrap_content" android:text="This is fragment #2" android:textColor="#000000" android:textSize="25sp"/><Buttonandroid:id="@+id/btnGetText"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Get text in Fragment #1"android:textColor="#000000"android:onClick="onClick" /></LinearLayout> - Return the two fragments to

main.xml:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical" xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity"> <fragment android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1" android:id="@+id/fragment1" android:layout_weight="1" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent"/> <fragment android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2" android:id="@+id/fragment2" android:layout_weight="1" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent"/> </LinearLayout> - Modify the

MainActivity.javafile by commenting out the code that you added in the earlier sections. It should look like this after modification:public class MainActivity extends Activity { /** Called when the activity is first created. */ @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);/*FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager(); FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction = fragmentManager.beginTransaction(); //---get the current display info--- DisplayMetrics display = this.getResources().getDisplayMetrics(); int width = display.widthPixels; int height = display.heightPixels; if (width> height) { //---landscape mode--- Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1(); // android.R.id.content refers to the content // view of the activity fragmentTransaction.replace( android.R.id.content, fragment1); } else { //---portrait mode--- Fragment2 fragment2 = new Fragment2(); fragmentTransaction.replace( android.R.id.content, fragment2); } fragmentTransaction.commit();*/} } - Add the following bolded statements to the

Fragment2.javafile:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments; import android.app.Fragment; import android.os.Bundle; import android.view.LayoutInflater; import android.view.View; import android.view.ViewGroup; import android.widget.Button; import android.widget.TextView; import android.widget.Toast; public class Fragment2 extends Fragment { @Override public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) { //---Inflate the layout for this fragment--- return inflater.inflate( R.layout.fragment2, container, false); }@Overridepublic void onStart() {super.onStart();//---Button view---Button btnGetText = (Button)getActivity().findViewById(R.id.btnGetText);btnGetText.setOnClickListener(new View.OnClickListener() {public void onClick(View v) {TextView lbl = (TextView)getActivity().findViewById(R.id.lblFragment1);Toast.makeText(getActivity(), lbl.getText(),Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();}});}} - Press Shift+F9 to debug the application on the Android emulator. In the second fragment on the right, click the button. You should see the

Toastclass displaying the textThis is fragment #1.

How It Works

Because fragments are embedded within activities, you can obtain the activity in which a fragment is currently embedded by first using the getActivity() method and then using the findViewById() method to locate the view(s) contained within the fragment:

TextView lbl = (TextView)

getActivity().findViewById(R.id.lblFragment1);

Toast.makeText(getActivity(), lbl.getText(),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); The getActivity() method returns the activity with which the current fragment is currently associated.

Alternatively, you can also add the following method to the MainActivity.java file:

public void onClick(View v) {

TextView lbl = (TextView)

findViewById(R.id.lblFragment1);

Toast.makeText(this, lbl.getText(),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}Understanding the Intent Object

So far, you have seen the use of the Intent object to call other activities. This is a good time to recap and gain a more detailed understanding of how the Intent object performs its magic.

First, you learned that you can call another activity by passing its action to the constructor of an Intent object:

startActivity(new Intent("com.jfdimarzio.SecondActivity"));The action (in this example "com.jfdimarzio.SecondActivity") is also known as the component name. This is used to identify the target activity/application that you want to invoke. You can also rewrite the component name by specifying the class name of the activity if it resides in your project, like this:

startActivity(new Intent(this, SecondActivity.class));You can also create an Intent object by passing in an action constant and data, such as the following:

Intent i = new

Intent(android.content.Intent.ACTION_VIEW,

Uri.parse("http://www.amazon.com"));

startActivity(i);The action portion defines what you want to do, whereas the data portion contains the data for the target activity to act upon. You can also pass the data to the Intent object using the setData() method:

Intent i = new

Intent("android.intent.action.VIEW");

i.setData(Uri.parse("http://www.amazon.com")); In this example, you indicate that you want to view a web page with the specified URL. The Android OS will look for all activities that are able to satisfy your request. This process is known as intent resolution. The next section discusses in more detail how your activities can be the target of other activities.

For some intents, there is no need to specify the data. For example, to select a contact from the Contacts application, you specify the action and then indicate the MIME type using the setType() method:

Intent i = new

Intent(android.content.Intent.ACTION_PICK);

i.setType(ContactsContract.Contacts.CONTENT_TYPE);NOTE

Chapter 9 discusses how to use the Contacts application from within your application.

The setType() method explicitly specifies the MIME data type to indicate the type of data to return. The MIME type for ContactsContract.Contacts.CONTENT_TYPE is "vnd.android.cursor.dir/contact".

Besides specifying the action, the data, and the type, an Intent object can also specify a category. A category groups activities into logical units so that Android can use those activities for further filtering. The next section discusses categories in more detail.

To summarize, an Intent object can contain the following information:

- Action

- Data

- Type

- Category

Using Intent Filters

Earlier, you saw how an activity can invoke another activity using the Intent object. In order for other activities to invoke your activity, you need to specify the action and category within the <intent-filter> element in the AndroidManifest.xml file, like this:

<intent-filter >

<action android:name="com.jfdimarzio.SecondActivity"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT"/>

</intent-filter>This is a very simple example in which one activity calls another using the "com.jfdimarzio.SecondActivity" action.

DISPLAYING NOTIFICATIONS

So far, you have been using the Toast class to display messages to the user. While the Toast class is a handy way to show users alerts, it is not persistent. It flashes on the screen for a few seconds and then disappears. If it contains important information, users may easily miss it if they are not looking at the screen.

For messages that are important, you should use a more persistent method. In this case, you should use the NotificationManager to display a persistent message at the top of the device, commonly known as the status bar (sometimes also referred to as the notification bar). The following Try It Out demonstrates how.

TRY IT OUT

Displaying Notifications on the Status Bar (Notifications.zip)

- Using Android Studio, create a new Android project and name it Notifications.

- Add a new class file named

NotificationViewto the package. In addition, add a newnotification.xmllayout resource file to theres/layoutfolder. - Populate the

notification.xmlfile as follows. Be sure to change all instances of"com.jfdimarzio"to whatever package name your project is using)<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent"><TextViewandroid:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Here are the details for the notification…" /></LinearLayout> - Populate the

NotificationView.javafile as follows:package com.jfdimarzio.notifications; import android.app.Activity; import android.app.NotificationManager; import android.os.Bundle; public class NotificationView extends Activity { @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); setContentView(R.layout.notification); //---look up the notification manager service--- NotificationManager nm = (NotificationManager) getSystemService(NOTIFICATION_SERVICE); //---cancel the notification that we started--- nm.cancel(getIntent().getExtras().getInt("notificationID")); } } - Add the following statements in bold to the

AndroidManifest.xmlfile:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" package="com.jfdimarzio.notifications"><uses-permission android:name="android.permission.VIBRATE"/><application android:allowBackup="true" android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher" android:label="@string/app_name" android:supportsRtl="true" android:theme="@style/AppTheme"> <activity android:name=".MainActivity"> <intent-filter> <action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/> <category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/> </intent-filter> </activity><activity android:name=".NotificationView"android:label="Details of notification"><intent-filter><action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" /><category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" /></intent-filter></activity></application> </manifest> - Add the following statements in bold to the

activity_main.xmlfile:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <RelativeLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin" android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin" tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.notifications.MainActivity"><Buttonandroid:id="@+id/btn_displaynotif"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Display Notification"android:onClick="onClick"/></RelativeLayout> - Add the following statements in bold to the

MainActivity.javafile:package com.jfdimarzio.notifications; import android.app.Activity;import android.app.NotificationManager;import android.app.PendingIntent;import android.content.Intent;import android.os.Bundle;import android.support.v4.app.NotificationCompat;import android.view.View;public class MainActivity extends Activity {int notificationID = 1;@Override protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); setContentView(R.layout.activity_main); }public void onClick(View view) {displayNotification();}protected void displayNotification(){//---PendingIntent to launch activity if the user selects// this notification---Intent i = new Intent(this, NotificationView.class);i.putExtra("notificationID", notificationID);PendingIntent pendingIntent = PendingIntent.getActivity(this, 0, i, 0);NotificationManager nm = (NotificationManager)getSystemService(NOTIFICATION_SERVICE);NotificationCompat.Builder notifBuilder;notifBuilder = new NotificationCompat.Builder(this).setSmallIcon(R.mipmap.ic_launcher).setContentTitle("Meeting Reminder").setContentText("Reminder: Meeting starts in 5 minutes");nm.notify(notificationID, notifBuilder.build());}} - Press Shift+F9 to debug the application on the Android emulator.

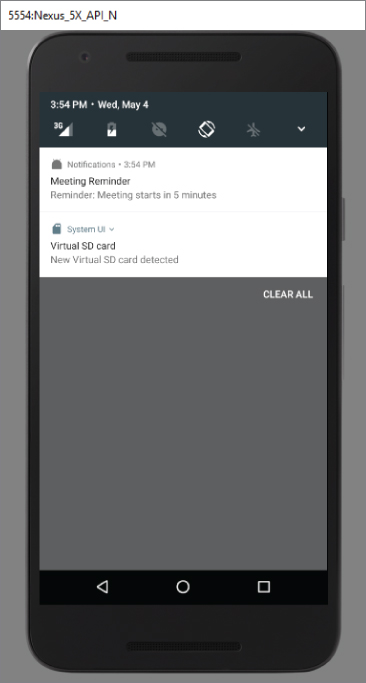

- Click the Display Notification button and a notification ticker text (set in the constructor of the

Notificationobject) displays on the status bar. - Click and drag the status bar down to reveal the notification details set using the

setLatestEventInfo()method of theNotificationobject (see Figure 3.19).

How It Works

To display a notification, you first created an Intent object to point to the NotificationView class:

Intent i = new Intent(this, NotificationView.class);

i.putExtra("notificationID", notificationID);This intent is used to launch another activity when the user selects a notification from the list. In this example, you added a name/value pair to the Intent object so that you can tag the notification ID, identifying the notification to the target activity. Later, you will use this ID to dismiss the notification.

You also need to create a PendingIntent object. A PendingIntent object helps you to perform an action on your application's behalf, often at a later time, regardless of whether your application is running. In this case, you initialized it as follows:

PendingIntent pendingIntent =

PendingIntent.getActivity(this, 0, i, 0);The getActivity() method retrieves a PendingIntent object and you set it using the following arguments:

- context—Application context

- request code—Request code for the intent

- intent—The intent for launching the target activity

- flags—The flags in which the activity is to be launched

You then obtain an instance of the NotificationManager class and create an instance of the NotificationCompat.Builder class:

NotificationManager nm = (NotificationManager)getSystemService(NOTIFICATION

_SERVICE);

NotificationCompat.Builder notifBuilder;

notifBuilder = new NotificationCompat.Builder(this)

.setSmallIcon(R.mipmap.ic_launcher)

.setContentTitle("Meeting Reminder")

.setContentText("Reminder: Meeting starts in 5 minutes");The NotificationCompat.Builder class enables you to specify the notification's main information.

Finally, to display the notification you use the notify() method:

nm.notify(notificationID, notifBuilder.build());SUMMARY

This chapter first provided a detailed look at how activities and fragments work and the various forms in which you can display them. You also learned how to display dialog windows using activities.

The second part of this chapter demonstrated a very important concept in Android—the intent. The intent is the “glue” that enables different activities to be connected, and it is a vital concept to understand when developing for the Android platform.

EXERCISES

- To create an activity, you create a Java class that extends what base class?

- What attribute of the Application element is used to specify the theme?

- What method do you override when displaying a dialog?

- What is used to navigate between activities?

- What method should you use if you plan on receiving information back from an activity?

You can find answers to the exercises in the appendix.

WHAT YOU LEARNED IN THIS CHAPTER

| TOPIC | KEY CONCEPTS |

| Creating an activity | All activities must be declared in the AndroidManifest.xml file. |

| Key life cycle of an activity | When an activity is started, the onStart() and onResume() events are always called. |

When an activity is killed or sent to the background, the onPause() event is always called. |

|

| Displaying an activity as a dialog | Use the showDialog() method and implement the onCreateDialog() method. |

| Fragments | Fragments are “mini-activities” that you can add or remove from activities. |

| Manipulating fragments programmatically | You need to use the FragmentManager and FragmentTransaction classes when adding, removing, or replacing fragments during runtime. |

| Life cycle of a fragment | Similar to that of an activity—you save the state of a fragment in the onPause() event, and restore its state in one of the following events: onCreate(), onCreateView(), or onActivityCreated(). |

| Intent | The “glue” that connects different activities. |

| Calling an activity | Use the startActivity() or startActivityForResult() method. |

| Passing data to an activity | Use the Bundle object. |

Components in an Intent object |

An Intent object can contain the following: action, data, type, and category. |

| Displaying notifications | Use the NotificationManager class. |