I first started playing with the Android Software Development Kit (SDK) before it was officially released as version 0.8. Back then, the tools were unpolished, the application programming interfaces (APIs) in the SDK were unstable, and the documentation was sparse. Android is now one of the most popular mobile operating systems in the world.

Every day, more developers are trying Android development using Android Studio, either as a hobby or professionally. The current challenge for many beginning developers who want to move into the exciting world of android development is trying to determine where to start.

It was with this challenge in mind that I was motivated to write this book, one that could benefit beginning Android programmers and enable them to write progressively more sophisticated applications.

This book is written to help jump-start beginning Android developers, covering the necessary topics in a linear manner so that you can build on your knowledge without being overwhelmed by the details. I adopt the philosophy that the best way to learn is by doing. The numerous Try It Out sections in each chapter first show you how to build something. Then the follow-up How It Works sections explain how everything works. I have also taken this opportunity to further improve the previous edition of this book by addressing feedback from readers and adding additional topics that are important to beginning Android developers.

Although Android programming is a huge topic, my aim for this book is threefold: to get you started with the fundamentals, to help you understand the underlying architecture of the SDK, and to appreciate why things are done in certain ways. It is beyond the scope of any book to cover everything under the sun related to Android programming. However, I am confident that after reading this book (and doing the exercises), you will be well equipped to tackle your next Android programming challenge.

This book is targeted for the beginning Android developer who wants to start developing applications using Google's Android SDK. To truly benefit from this book, you should have some background in programming and at least be familiar with object-oriented programming (OOP) concepts. If you are totally new to Java—the language used for Android development—you might want to take a programming course in Java programming or grab one of many good books on Java programming. In my experience, if you already know C# or VB.NET, learning Java doesn't require too much effort. If you're already comfortable with C# or VB.NET, you should be comfortable just following along with the Try It Outs.

For those totally new to programming, I know the lure of developing mobile apps and making some money is tempting. However, before attempting to try out the examples in this book, I think a better starting point would be to first learn the basics of programming.

This book covers the fundamentals of Android programming using the Android SDK. It is divided into 12 chapters and one appendix.

This book breaks down the task of learning Android programming into several smaller chunks, enabling you to digest each topic before delving into a more advanced one.

If you are a total beginner to Android programming, start with Chapter 1. After you have familiarized yourself with the basics, head to Chapter 2 and get to know the Android Studio IDE. When you are ready, continue with Chapter 3 and gradually move into more advanced topics.

A feature of this book is that all the code samples in each chapter are independent of those discussed in previous chapters. This gives you the flexibility to dive into the topics that interest you and start working on the Try It Out projects.

All the examples in this book run on the Android emulator (which is included as part of the Android SDK and Android Studio). However, to get the most out of this book, it would be useful to have a real Android device (though it's not absolutely necessary).

To help you get the most from the text and keep track of what's happening, a number of conventions are used throughout the book.

As for other conventions in the text:

persistence.properties.We use a monofont type with no highlighting for most code examples.

We use bolding to emphasize code that is of particular importance in the

present context.As you work through the examples in this book, you may choose either to type in all the code manually or to use the source code files that accompany the book. All the source code used in this book is available for download at www.wrox.com. When at the site, simply locate the book's title (use the Search box or one of the title lists) and click the Download Code link on the book's detail page to obtain all the source code for the book.

You'll find the filename of the project you need at the end of the title of the Try it Out features:

We make every effort to ensure that there are no errors in the text or in the code. However, no one is perfect, and mistakes do occur. If you find an error in one of our books, such as a spelling mistake or faulty piece of code, we would be very grateful for your feedback. By sending in errata, you might save another reader hours of frustration and at the same time help us provide even higher-quality information.

To find the errata page for this book, go to www.wrox.com and locate the title using the Search box or one of the title lists. Then, on the book details page, click the Book Errata link. On this page, you can view all errata that has been submitted for this book and posted by Wrox editors.

If you don't spot “your” error on the Book Errata page, go to www.wrox.com/contact/techsupport.shtml and complete the form there to send us the error you have found. We'll check the information and, if appropriate, post a message to the book's errata page and fix the problem in subsequent editions of the book.

For author and peer discussion, join the P2P forums at p2p.wrox.com. The forums are a web-based system for you to post messages relating to Wrox books and related technologies. There, you also can interact with other readers and technology users. The forums offer a subscription feature that enables you to receive emails about topics of interest (of your choosing) when new posts are made to the forums. Wrox authors, editors, other industry experts, and your fellow readers are present on these forums.

At p2p.wrox.com, you will find a number of different forums that will help you not only as you read this book but also as you develop your own applications. To join the forums, follow these steps:

After you join, you can post new messages and respond to messages posted by other users. You can read messages at any time on the web. If you want to have new messages from a particular forum emailed to you, click the Subscribe to This Forum icon next to the forum name in the forum listing.

For more information about how to use the Wrox P2P, be sure to read the P2P FAQs for answers to questions about how the forum software works, as well as many common questions specific to P2P and Wrox books. To read the FAQs, click the FAQ link on any P2P page.

Welcome to the world of Android! This chapter explains what Android is and what makes it so compelling to both developers and device manufacturers. It also shows you how to obtain and set up all the necessary tools so that you can test your application on an Android emulator in Android Studio 2 and how to get started with developing your first Android application. By the end of this chapter, you will be equipped with the basic knowledge you need to explore more sophisticated techniques and tricks for developing your next killer Android application.

Android is a mobile operating system that is based on a modified version of Linux. It was originally developed by a startup of the same name, Android, Inc. In 2005, as part of its strategy to enter the mobile space, Google purchased Android, Inc. and took over its development work (as well as its development team).

Google wanted the Android OS to be open and free, so most of the Android code was released under the open source Apache License. That means anyone who wants to use Android can do so by downloading the full Android source code. Moreover, vendors (typically hardware manufacturers) can add their own proprietary extensions to Android and customize Android to differentiate their products from others. This development model makes Android very attractive to vendors, especially those companies affected by the phenomenon of Apple's iPhone, which was a hugely successful product that revolutionized the smartphone industry. When the iPhone was launched, many smartphone manufacturers had to scramble to find new ways of revitalizing their products. These manufacturers saw Android as a solution, meaning they will continue to design their own hardware and use Android as the operating system that powers it. Some companies that have taken advantage of Android's open source policy include Motorola and Sony Ericsson, which have been developing their own mobile operating systems for many years.

The main advantage to adopting Android is that it offers a unified approach to application development. Developers need only develop for Android in general, and their applications should be able to run on numerous different devices, as long as the devices are powered using Android. In the world of smartphones, applications are the most important part of the success chain.

Android has gone through quite a number of updates since its first release. Table 1.1 shows the various versions of Android and their codenames.

Table 1.1 A Brief History of Android Versions

| ANDROID VERSION | RELEASE DATE | CODENAME |

| 1.1 | February 9, 2009 | |

| 1.5 | April 30, 2009 | Cupcake |

| 1.6 | September 15, 2009 | Donut |

| 2.0/2.1 | October 26, 2009 | Éclair |

| 2.2 | May 20, 2010 | Froyo |

| 2.3 | December 6, 2010 | Gingerbread |

| 3.0/3.1/3.2 | February 22, 2011 | Honeycomb |

| 4.0 | October 18, 2011 | Ice Cream Sandwich |

| 4.1 | July 9, 2012 | Jelly Bean |

| 4.4 | October 31, 2013 | KitKat |

| 5.0 | November 12, 2014 | Lollipop |

| 6.0 | October 5, 2015 | Marshmallow |

| 7.0 | TBD | Nougat |

In 2016, Google released Android 7.0; the following are the key changes in Android 7.0:

One important thing to keep in mind as you are looking at Android versions is that each version has its own features and APIs (application programming interfaces). Therefore, if your application is written for the newest version of Android, and it uses an API that was not present in an older version of Android, then only devices running that newer version of Android will be able to use your application.

Because Android is open source and freely available to manufacturers for customization, there are no fixed hardware or software configurations. However, the base Android OS supports many features, including

Android's web browser is based on the open source WebKit and Chrome's V8 JavaScript engine.

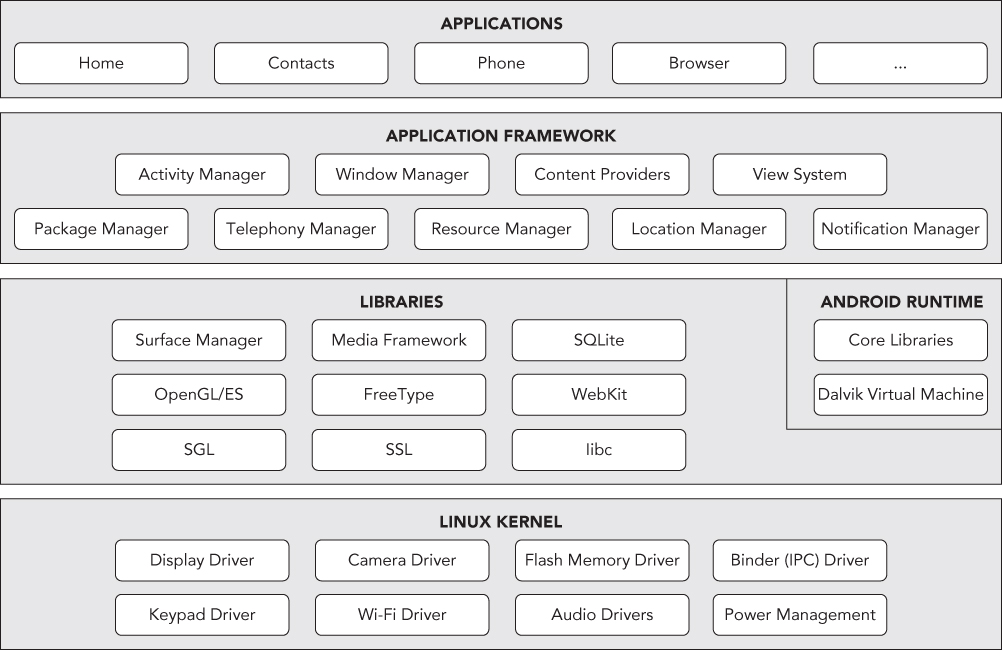

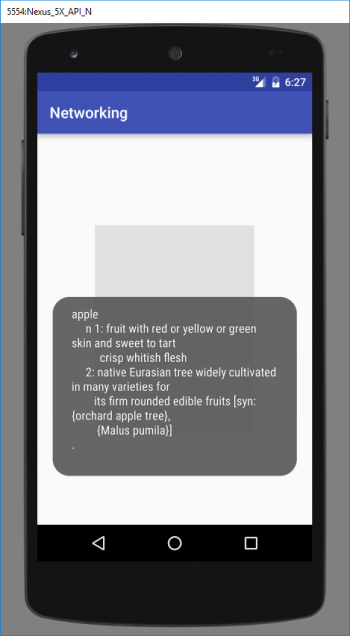

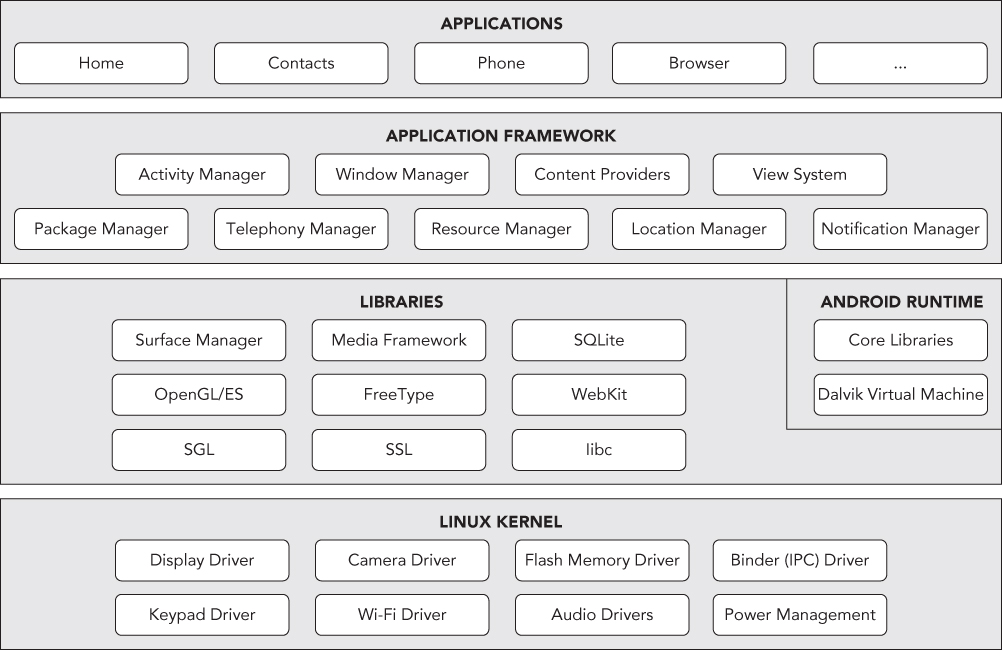

To understand how Android works, take a look at Figure 1.1, which shows the various layers that make up the Android operating system (OS).

The Android OS is roughly divided into five sections in four main layers:

Android devices come in all shapes and sizes including, but not limited to, the following types of devices:

Chances are good that you own at least one of the preceding devices. Figure 1.2 shows the Samsung Galaxy Edge 7.

Another popular category of devices is the tablet. Tablets typically come in two sizes: 7″ and 10″, measured diagonally.

Besides smartphones and tablets, Android is used in dedicated devices, such as e-book readers. Figure 1.4 shows the Barnes and Noble's NOOK Color running the Android OS.

In addition to the popular mobile devices I've already mentioned, Android is finding its way onto your wrist. Smartwatches, and “wearables” in general, have become a major segment of the Android population. Figure 1.3 shows the Motorola Moto 360 Smartwatch, which runs Android Wear (a version of Android OS specifically designed for wearables).

At the time of writing, the Samsung Galaxy Nexus (see Figure 1.4) is the only device running a pure version of Android. Many manufacturers add their own modifications to the Android OS for use on their specific devices. Motorola devices have Motoblur, HTC devices have HTC Sense, and so on. However, the Nexus devices always run a clean version of Android with no modifications.

As mentioned earlier, one of the main factors determining the success of a smartphone platform is the applications that support it. It is clear from the success of the iPhone that applications play a very vital role in determining whether a new platform swims or sinks. Also, making these applications accessible to the general user is extremely important.

Users can simply use the Google Play application that is preinstalled on their Android devices to directly download third-party applications to their devices. Both paid and free applications are available in the Google Play Store, although paid applications are available only to users in certain countries because of legal issues.

Now that you know what Android is and what its feature set contains, you are probably anxious to get your hands dirty and start writing some applications! Before you write your first app, however, you need to download the required tools.

For Android development, you can use a Mac, a Windows PC, or a Linux machine. You can freely download all the necessary tools. Most of the examples provided in this book are written to work on Android Studio. For this book, I am using a Windows 10 computer to demonstrate all the code samples. If you are using a Mac or Linux computer, the screenshots should look similar. Some minor differences might be present, but you should be able to follow along without problems.

Let the fun begin!

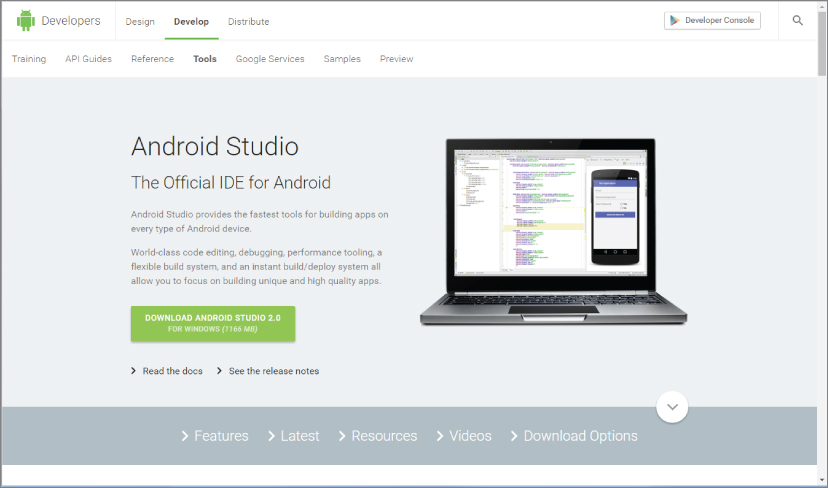

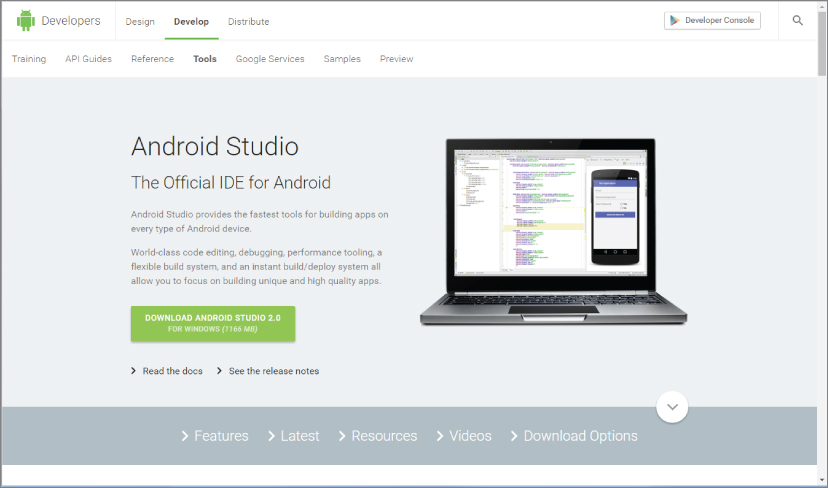

The first and most important piece of software you need to download is Android Studio 2. After you have downloaded and installed Android Studio 2, you can use the SDK Manager to download and install multiple versions of the Android SDK. Having multiple versions of the SDK available enables you to write programs that target different devices. For example, you can write one version of an application that specifically targets Android Nougat, but because that flavor of Android is on less than 1% of devices, with multiple versions of the SDK you can also write a version of your app that uses older features and targets Marshmallow or Lollipop users. You can use the Android Device Manager to set up device emulators.

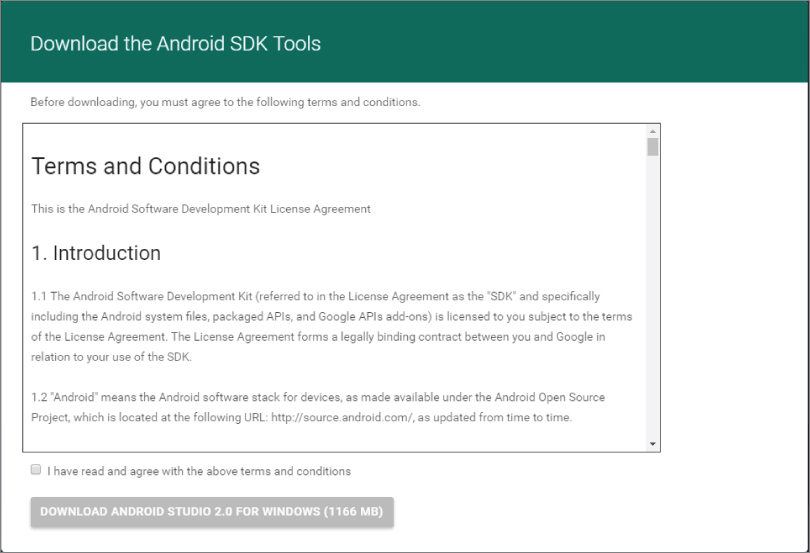

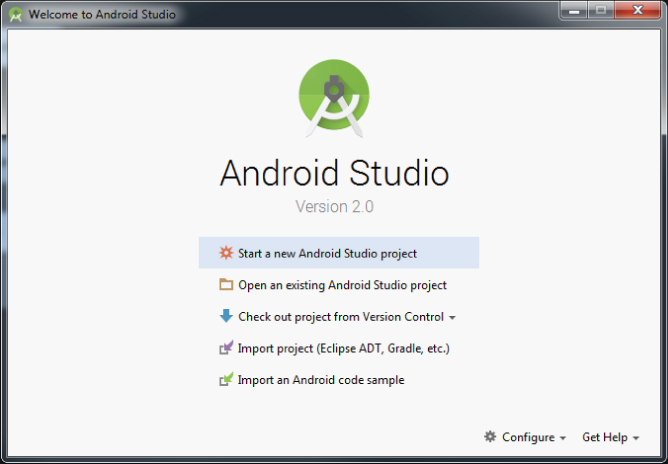

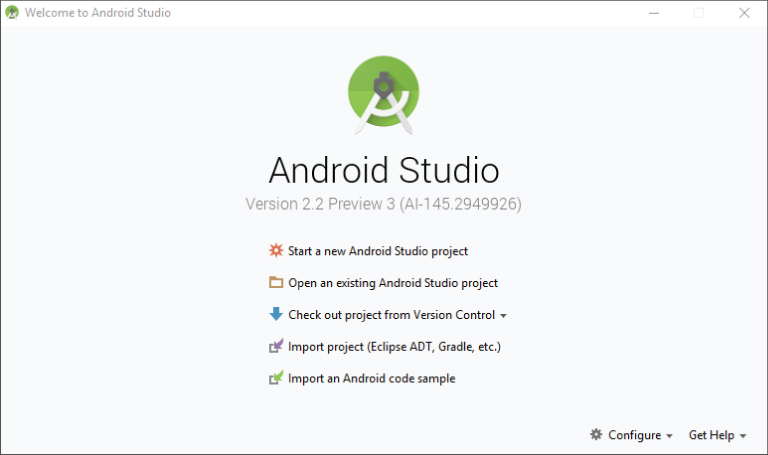

You can download Android Studio 2 from http://developer.android.com/sdk/index.html (see Figure 1.5).

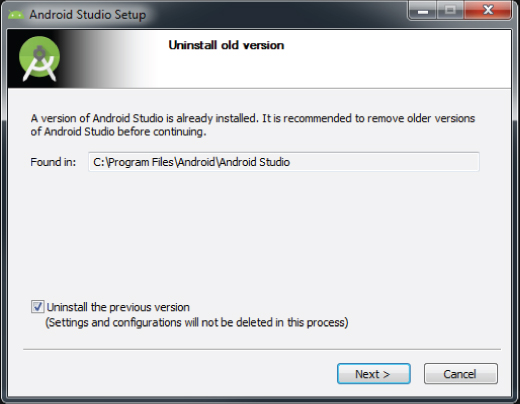

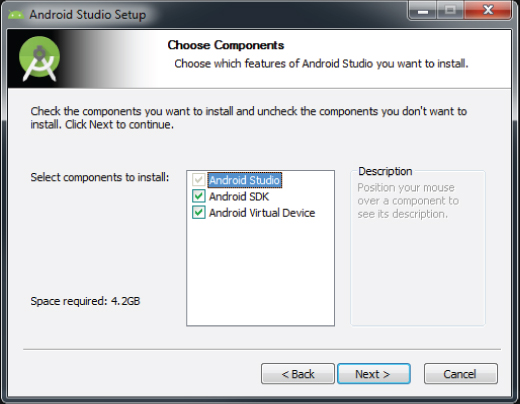

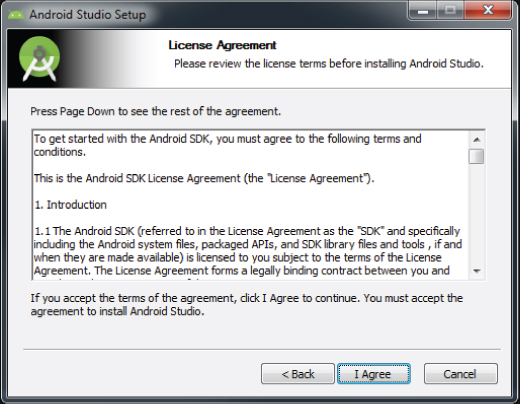

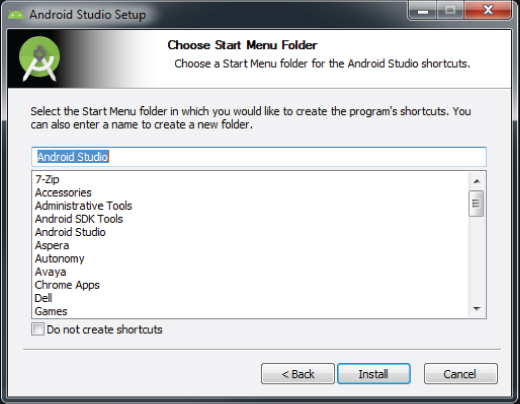

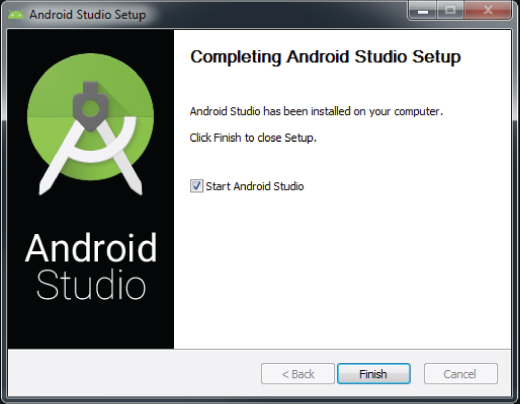

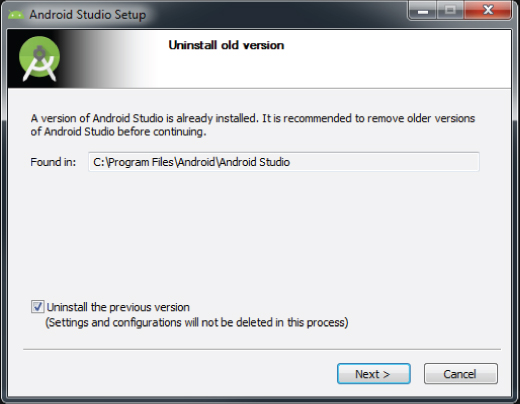

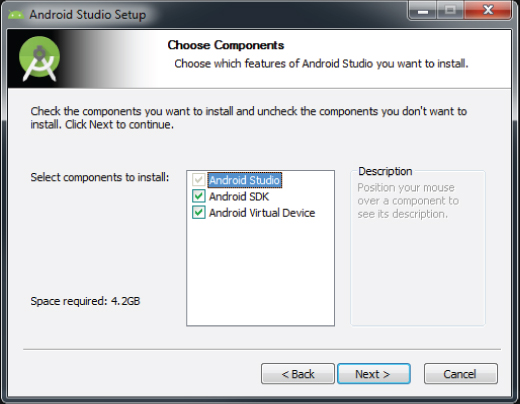

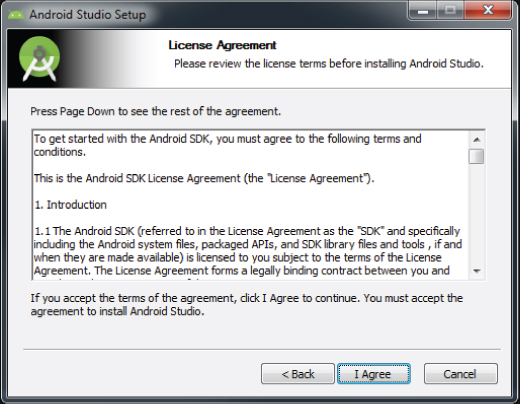

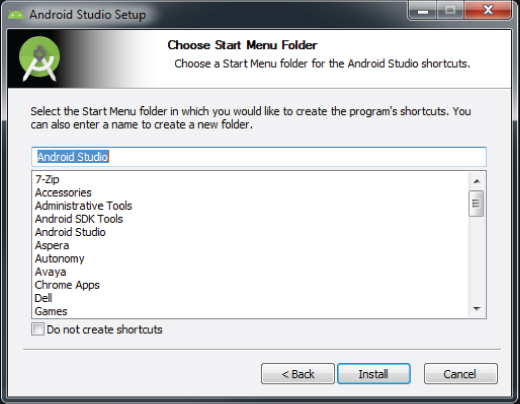

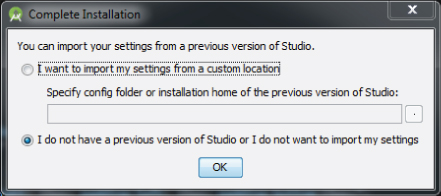

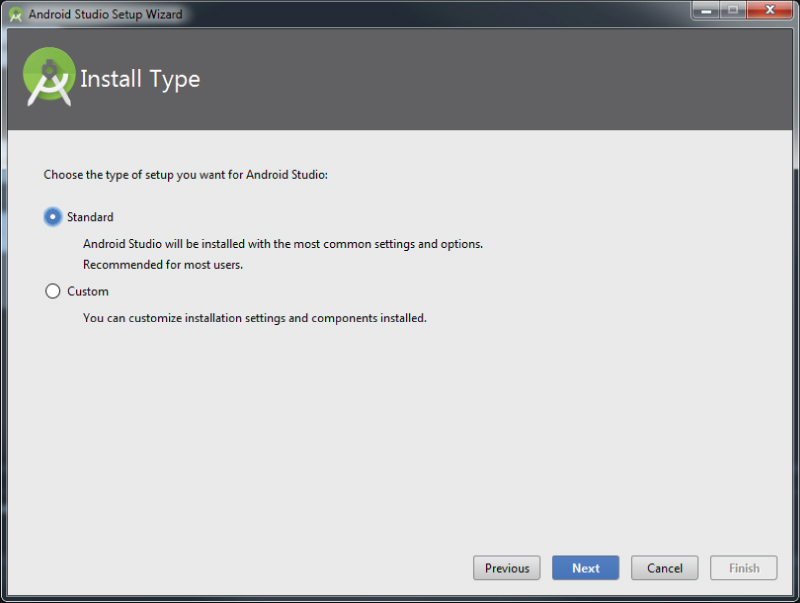

Android Studio 2 is packaged in an executable. Run the install process to set up Android Studio 2. After you've downloaded and run the setup executable, use the following steps to go through the installation process:

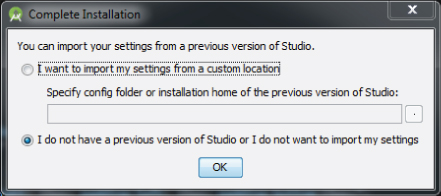

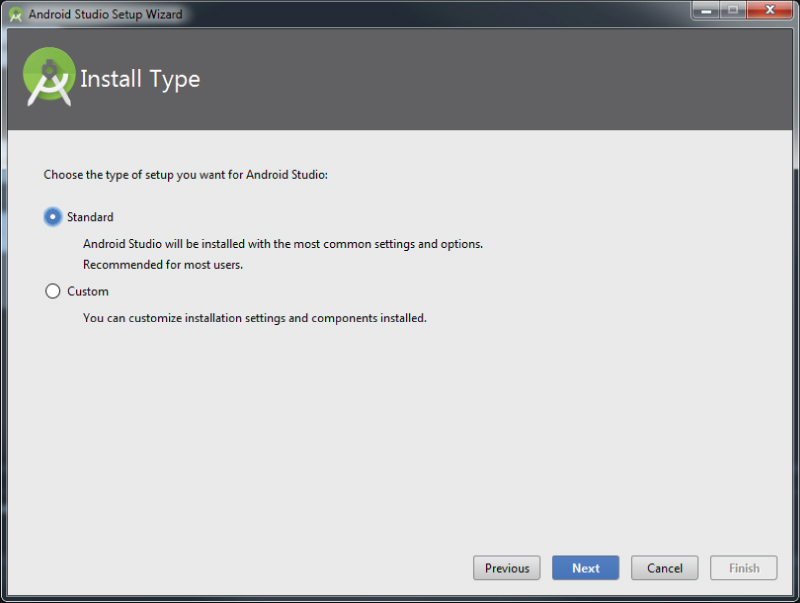

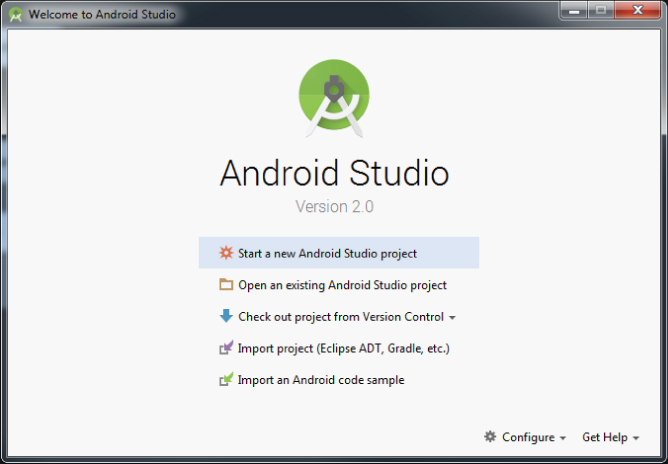

Now that Android Studio 2 is installed, you need to adjust the settings and options using the following steps:

Now that Android Studio is set up, it's time to install the latest and greatest Android SDK.

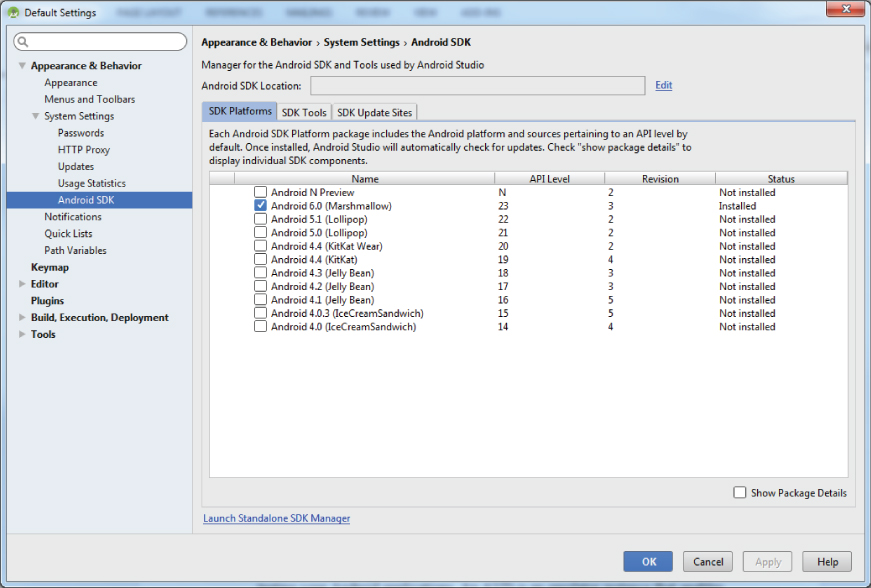

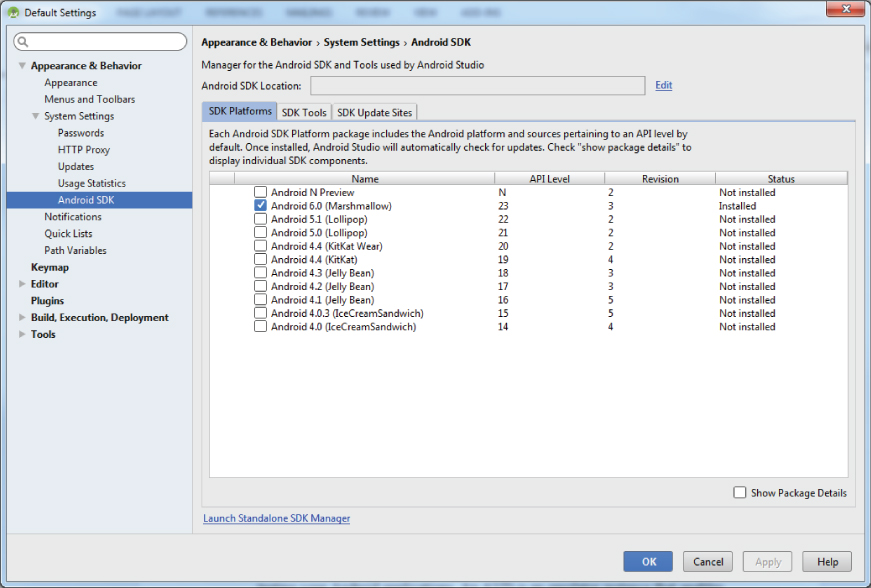

The most important piece of software you need to download is, of course, the Android SDK. The Android SDK contains all of the packages and tools required to develop a functional Android application. The SDKs are named after the version of Android OS to which they correspond. By default, the Marshmallow SDK was installed with Android Studio 2, which means you can develop applications that will run seamlessly on devices with Android Marshmallow.

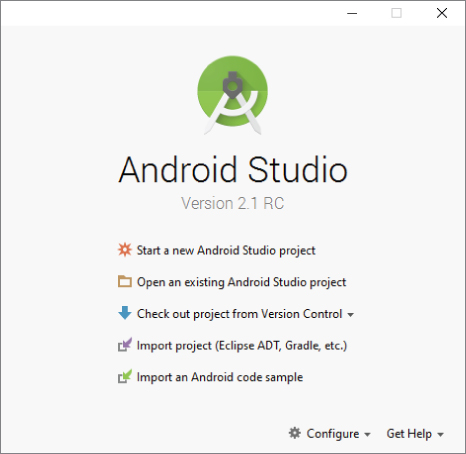

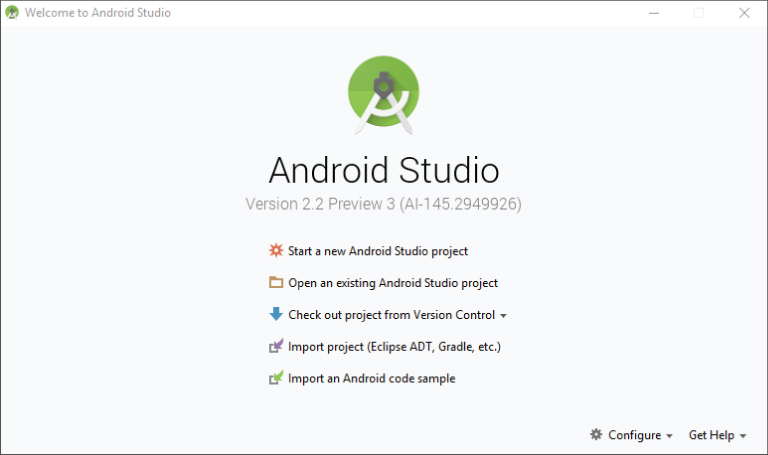

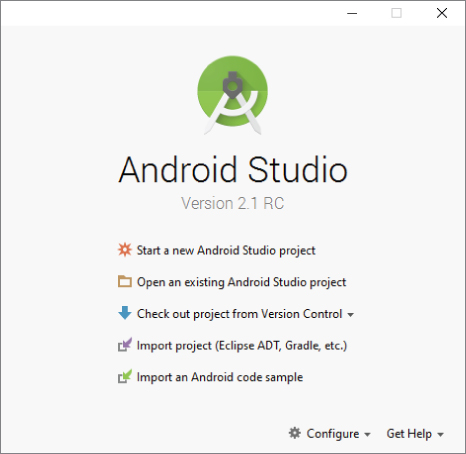

However, if you want to install a different Android SDK, you can do so using the SDK Manager from the Android Studio welcome screen (shown in Figure 1.15). From this screen, click the Configure drop-down menu in the lower-right corner. The Configure selection menu opens. Choose SDK Manager from this menu.

The SDK configuration screen, shown in Figure 1.16, shows that the Marshmallow SDK is already installed. Android N is available to be installed (as of the writing of this book Android Nougat was in a finalized beta, so it might be named differently now).

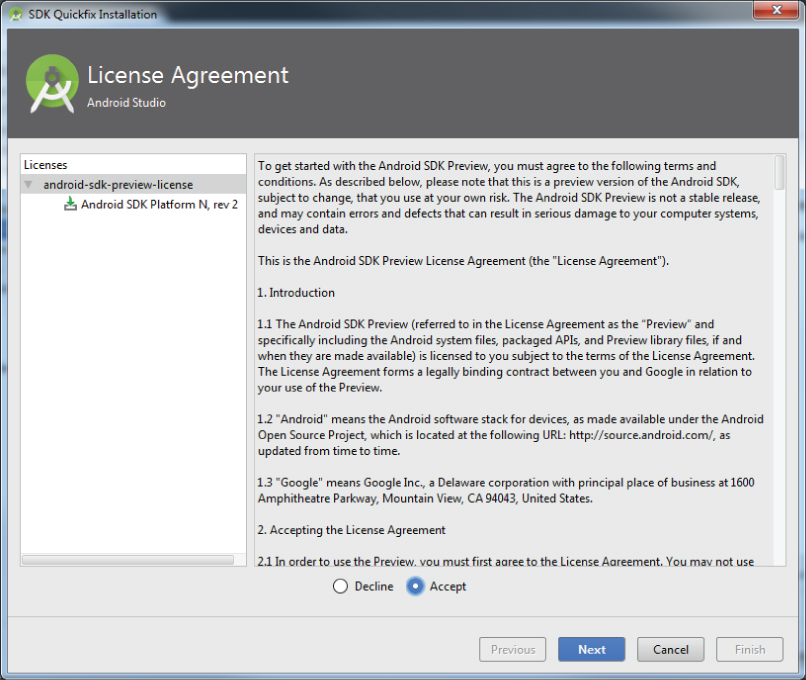

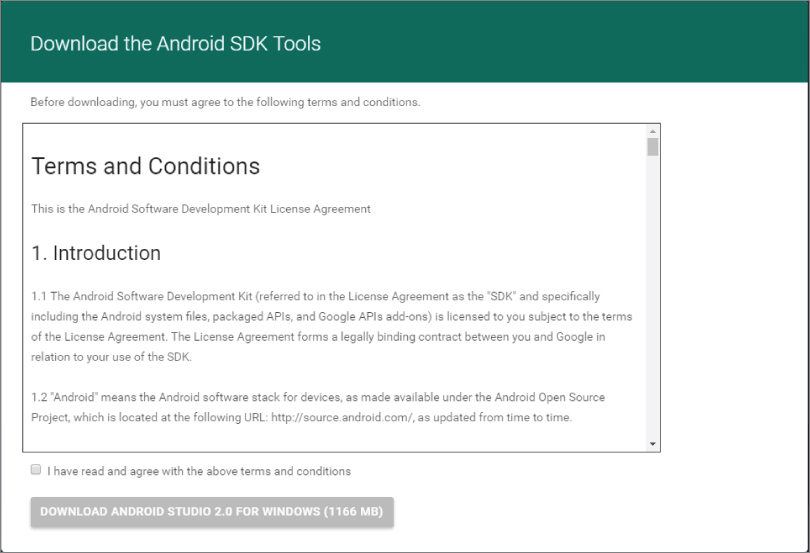

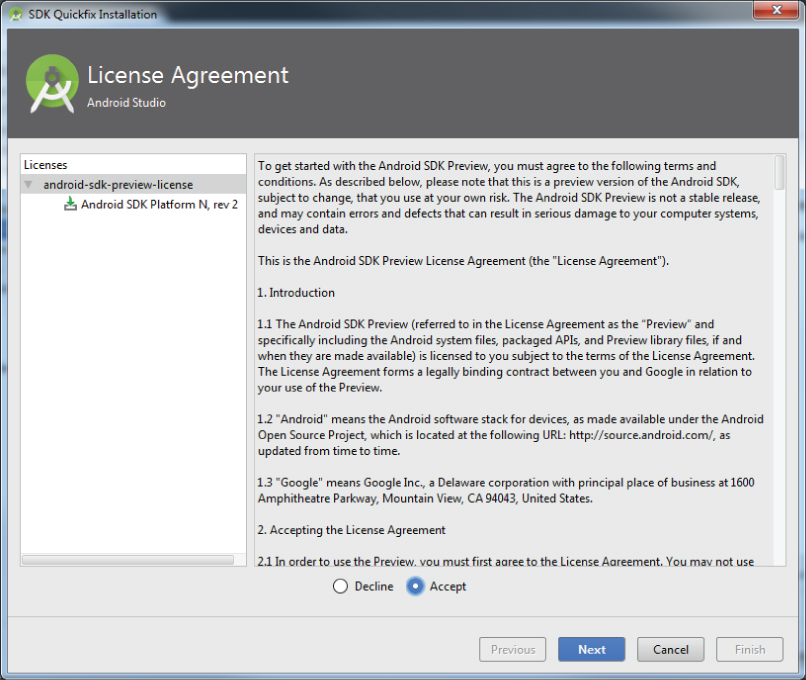

Select Android Nougat, click Apply, and then click OK. However, before the SDK is installed you must accept the licensing agreement as shown in Figure 1.17.

The setup process for Android Studio is now complete. The next section explains how to set up an Android Virtual Device that you can use to test your applications.

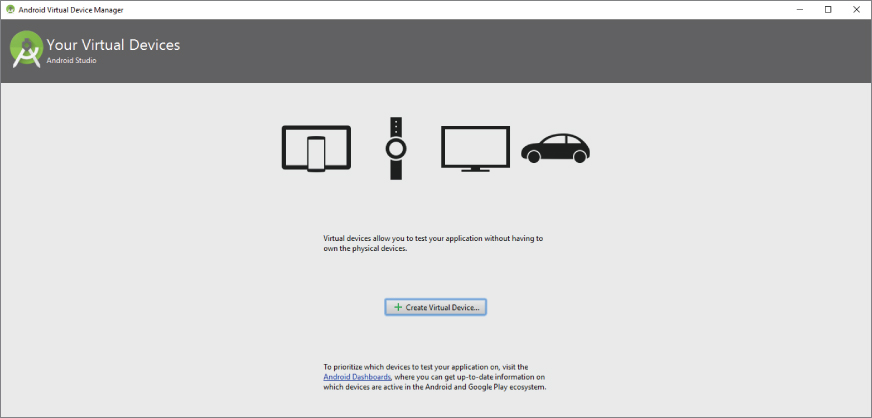

The next step is to create an Android Virtual Device (AVD) you can use for testing your Android applications. An AVD is an emulator instance that enables you to model an actual device. Each AVD consists of a hardware profile; a mapping to a system image; and emulated storage, such as a secure digital (SD) card. One important thing to remember about emulators is that they are not perfect. There are some applications, such as games (which are GPU heavy) or applications that use sensors such as the GPS or accelerometer. These types of applications cannot be simulated with the same speed or consistency within an emulator as they can when running on an actual device. However, the emulator is good for doing some generalized testing of your applications.

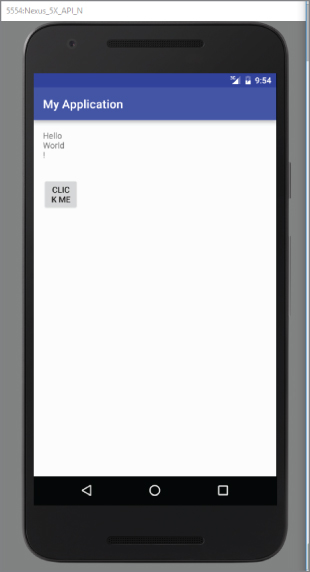

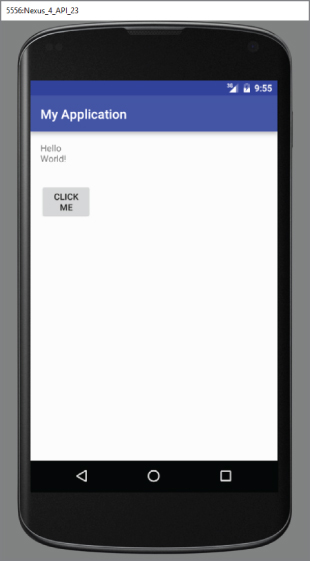

You can create as many AVDs as you want to test your applications with different configurations. This testing is important to confirm the behavior of your application when it is run on different devices with varying capabilities.

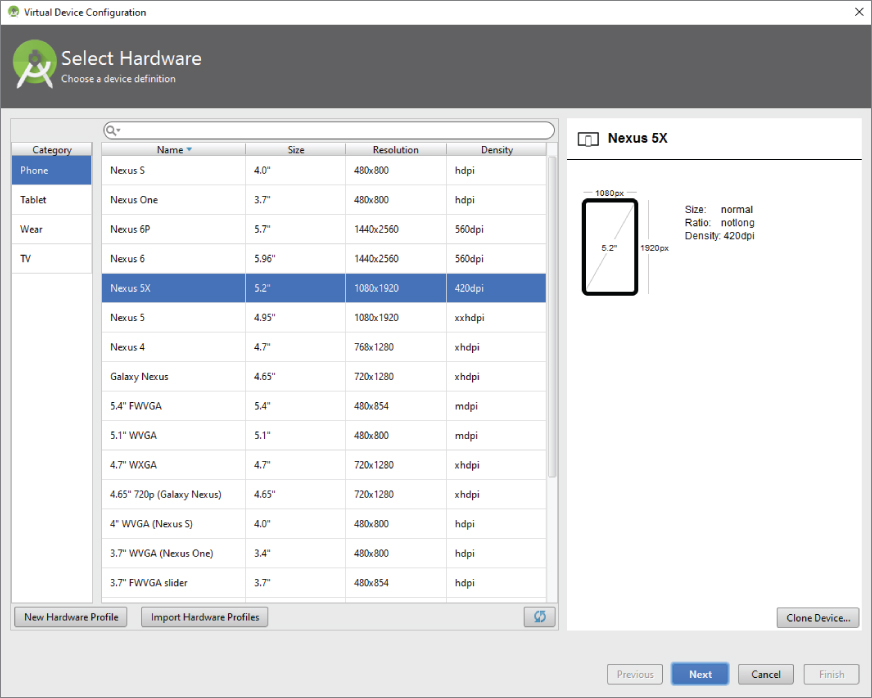

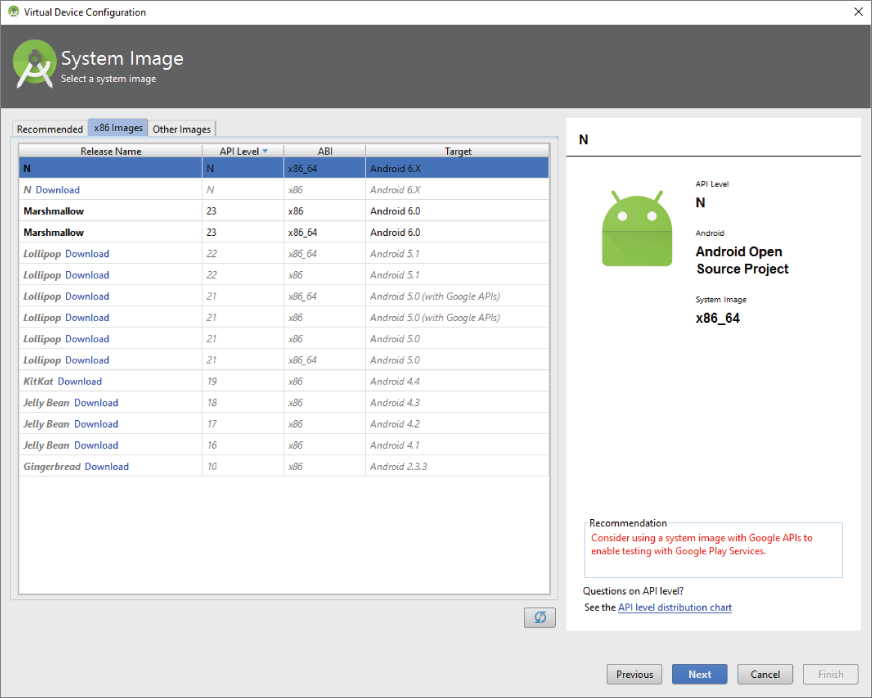

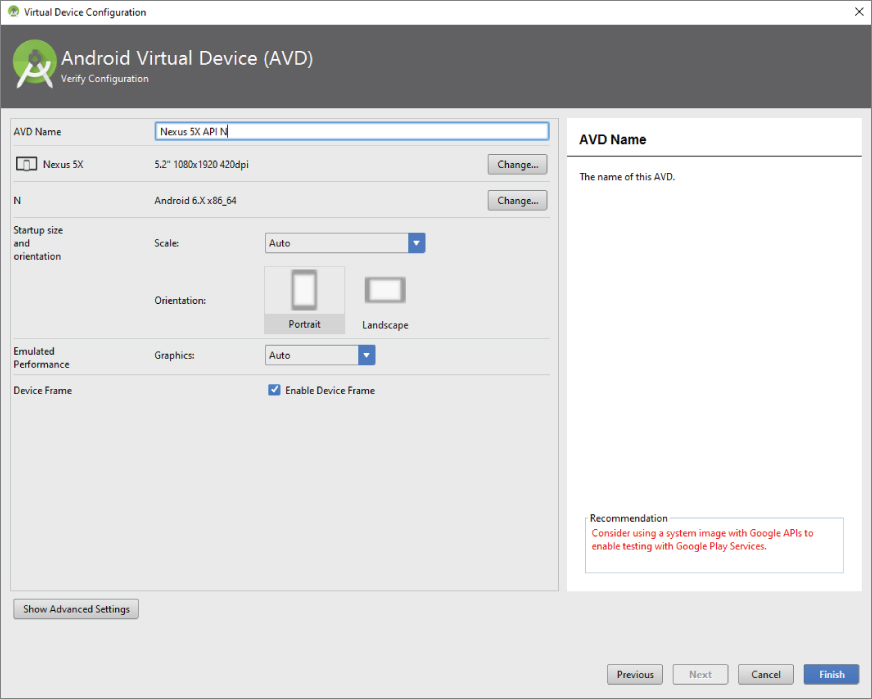

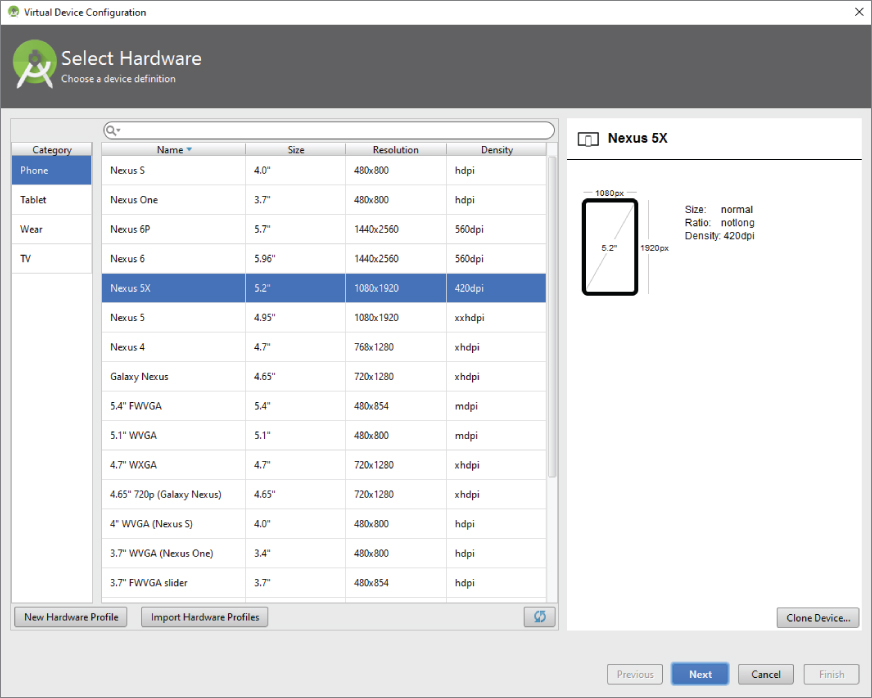

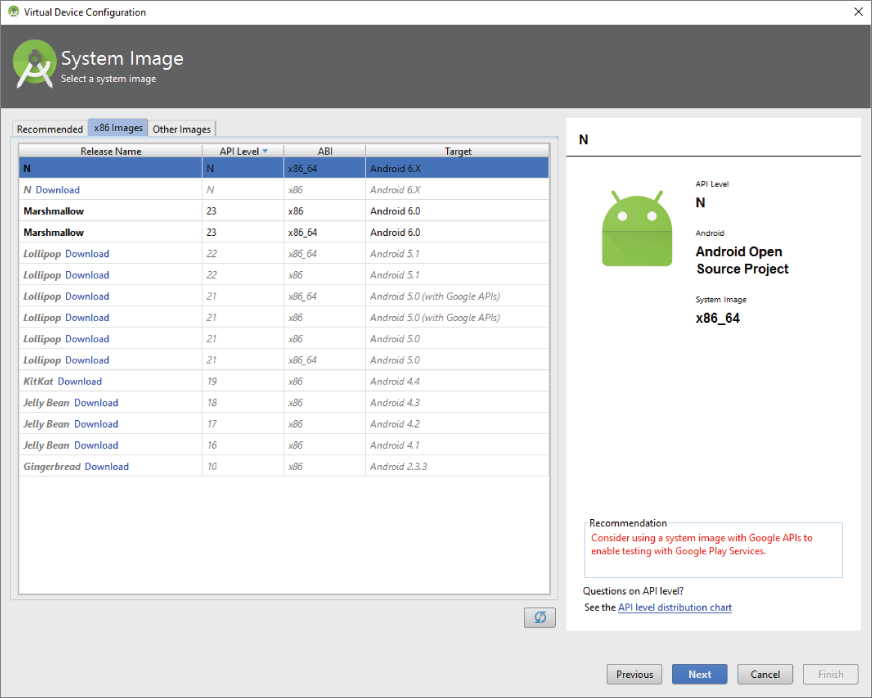

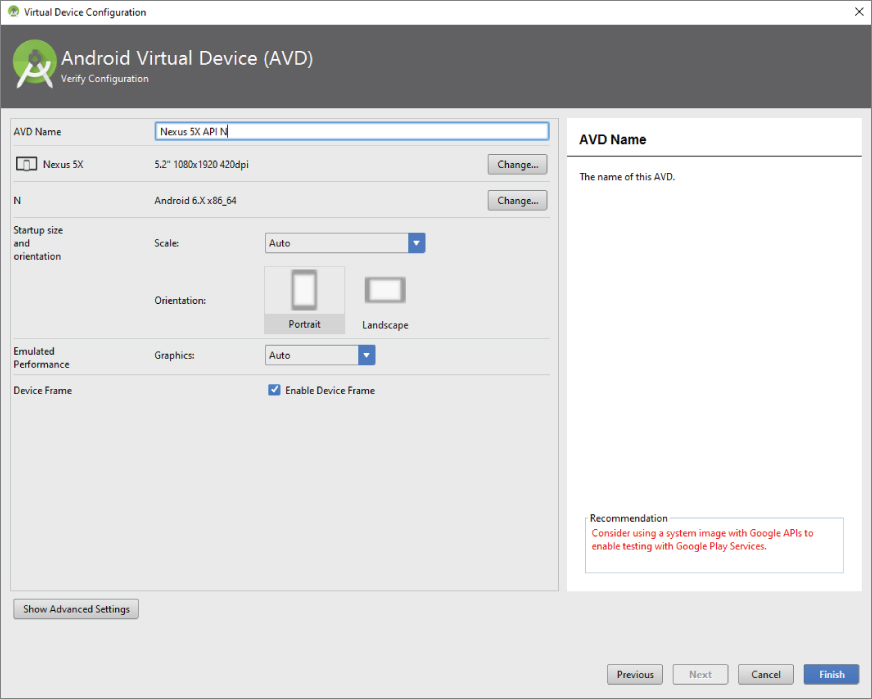

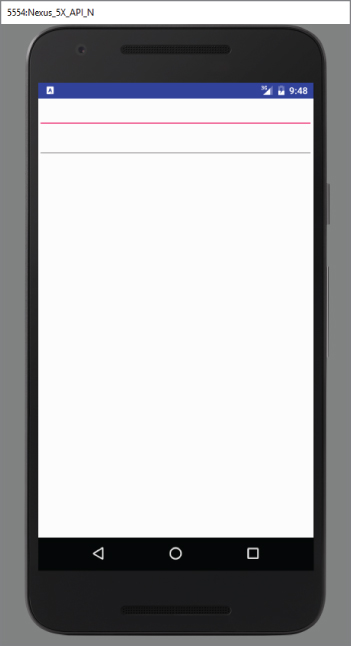

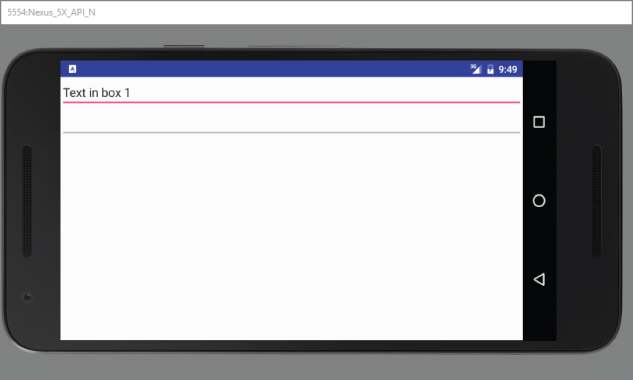

Use the following steps to create an AVD. This example demonstrates creating an AVD (put simply, an Android emulator) that emulates an Android device running Android N on the Nexus 5x hardware specs.

Android

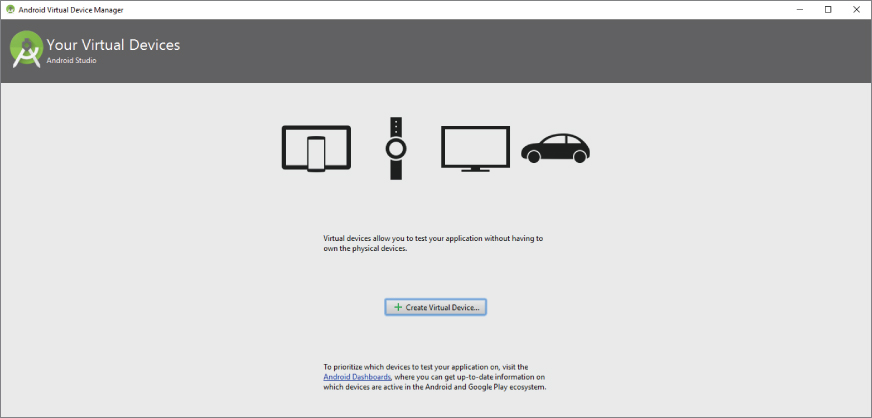

Android  AVD Manager or using the AVD Manager button from the toolbar. Figure 1.23 shows the Android Virtual Device Manager Wizard, which is where you set up AVDs to be used when you emulate your application in Android on your desktop.

AVD Manager or using the AVD Manager button from the toolbar. Figure 1.23 shows the Android Virtual Device Manager Wizard, which is where you set up AVDs to be used when you emulate your application in Android on your desktop.

Android

Android  AVD Manager or using the AVD Manager button from the toolbar.

AVD Manager or using the AVD Manager button from the toolbar.After you have created your ADV, it is time to test it. There is no better way to do this than to create and launch the ubiquitous Hello World application.

Now that Android is in its seventh version, there is a large developer community all over the world. It is easy to find solutions to problems and to find like-minded developers with whom to share app ideas and experiences.

The following are some developer communities and websites that you can turn to for help if you run into problems while working with Android:

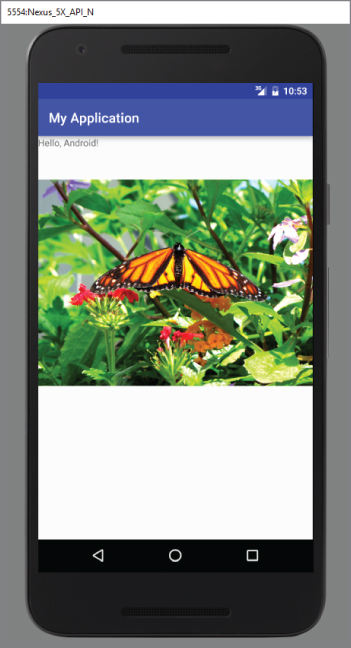

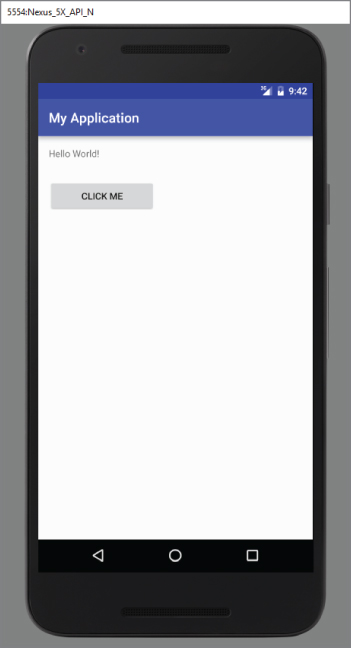

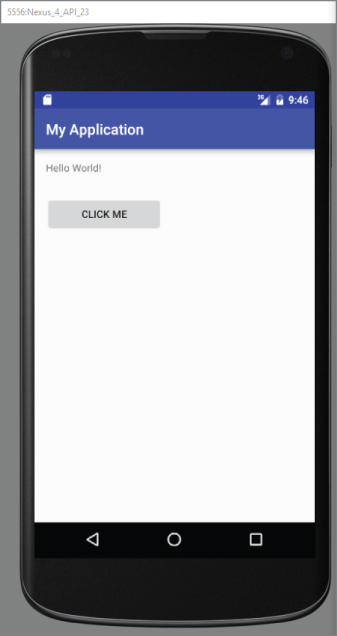

With all the tools and the SDK downloaded and installed, it is now time to start your engine. As in most programming books, the first example uses the ubiquitous Hello World application. This will give you a detailed look at the various components that make up an Android project. This is also the easiest Android project you will ever make.

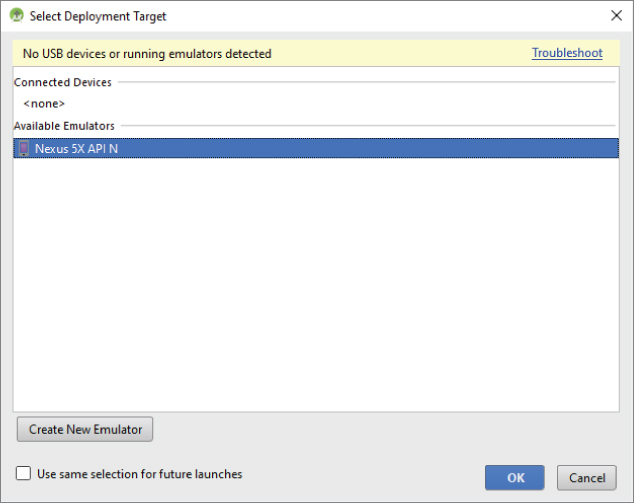

Believe it or not, the Hello World application is already finished. By default, when you create a new application in Android Studio, it creates a Hello World application. Let's launch this application and, in the process, also launch the Android emulator to see how everything works.

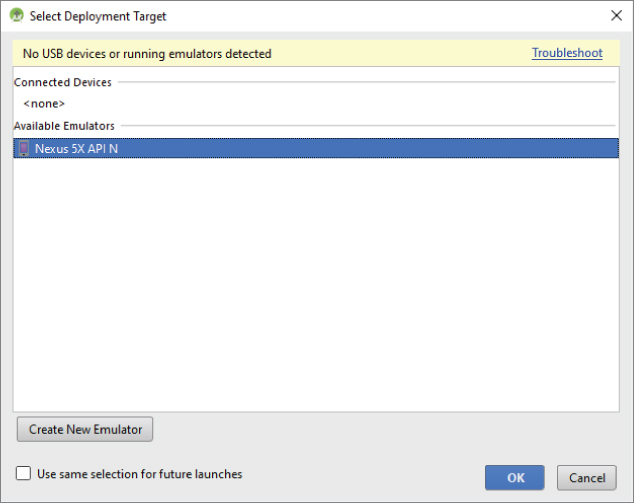

Run app from the Android Studio menu bar. You should see the Select Deployment Target dialog as shown in Figure 1.27.

Run app from the Android Studio menu bar. You should see the Select Deployment Target dialog as shown in Figure 1.27.

Run app from the Android Studio menu bar.

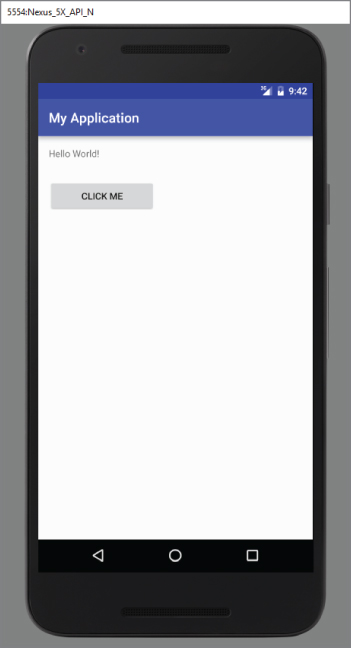

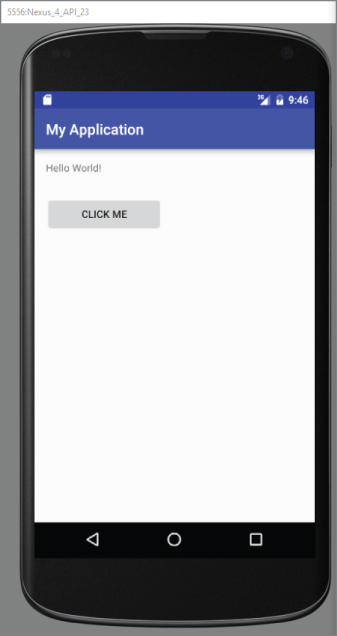

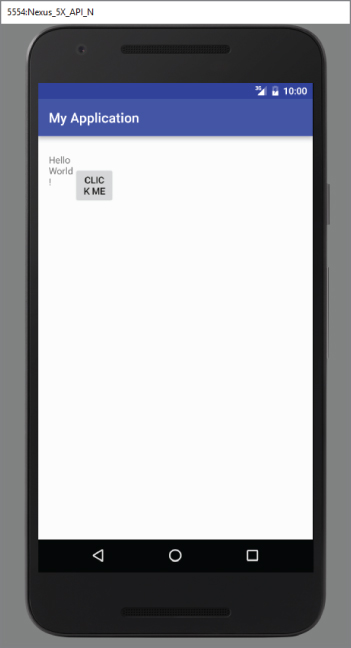

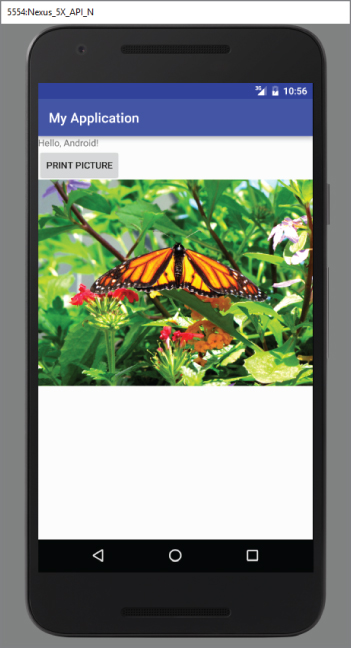

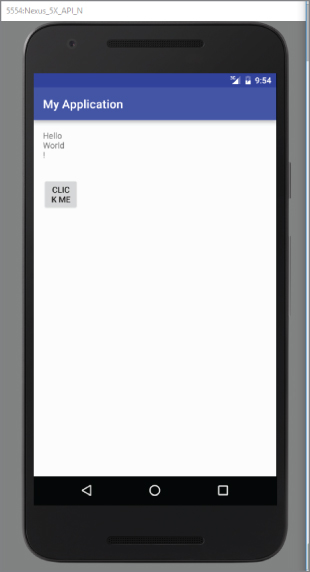

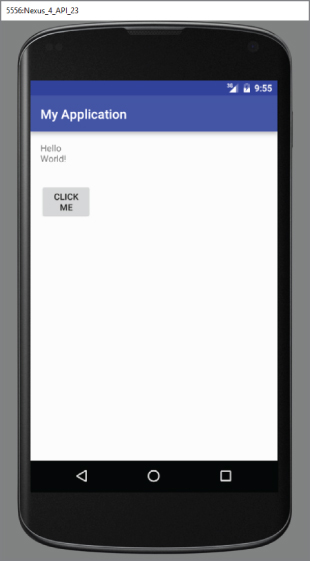

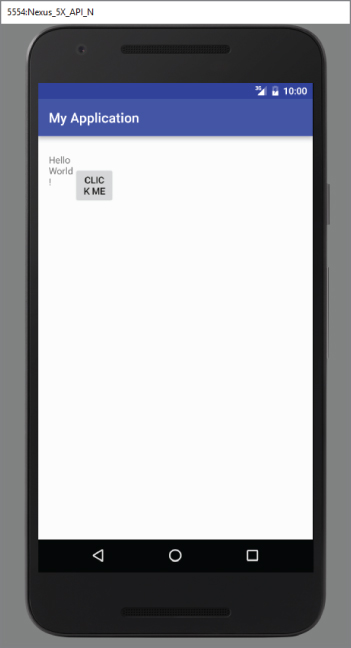

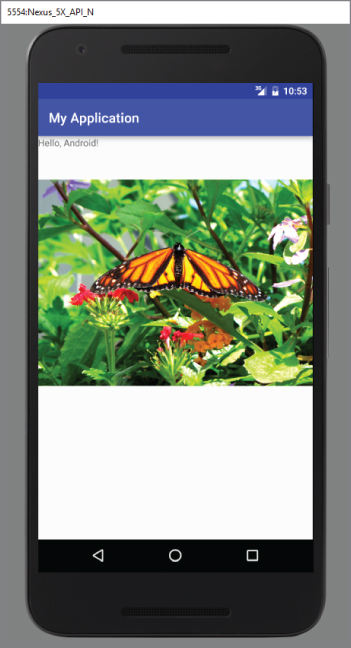

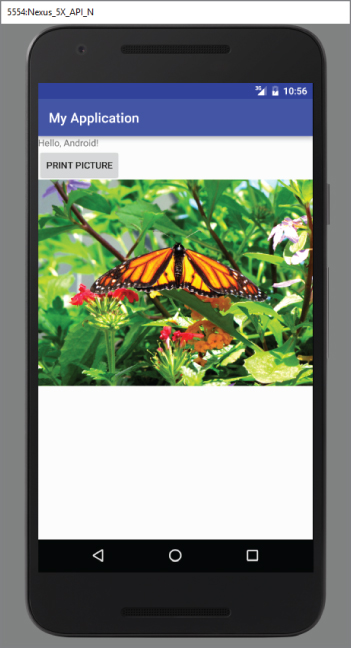

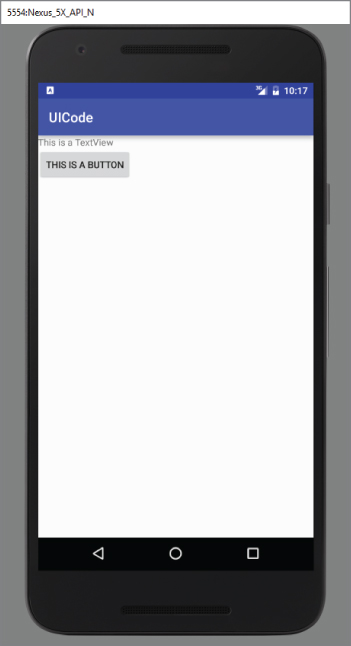

Run app from the Android Studio menu bar.With the emulator fully loaded and started, Android Studio can install your Hello World application. The application will display as shown in Figure 1.28.

This was a very quick example of how to create and launch your first Android applications. However, what this example has really done for you is introduce you, on a general scale, to most of the major skills you will fine tune throughout this book.

This chapter provided a brief overview of Android and highlighted some of its capabilities. If you have followed the sections on downloading the tools and the Android SDK, you should now have a working system—one that is capable of developing Android applications that are more interesting than the Hello World application. In the next chapter, you find out about the inner workings of Android Studio before moving on to more complex Android application development concepts.

You can find answers to the exercises in the appendix.

| TOPIC | KEY CONCEPTS |

| Android OS | Android is an open source mobile operating system based on the Linux operating system. It is available to anyone who wants to adapt it to run on their own devices. |

| Languages used for Android application development | You use the Java programming language to develop Android applications. Written applications are compiled into Dalvik executables, which are then run on top of the Dalvik virtual machine. |

| Google Play | Google Play hosts all the various Android applications written by third-party developers. |

| Tools for Android application development | Android Studio, Android SDK, and virtual devices. |

Chapter 1 covers how to install and initially configure Android Studio for the purposes of developing Android applications. This chapter explains how to navigate the intricacies of Android Studio in a way that helps you develop applications more easily and with great efficiency.

Android Studio contains myriad features to help everyone from the greenest novices to the most senior superstar developers. By the time you finish this chapter, you will be able to navigate through the features of Android Studio with confidence, produce code that is easy to read and easy to reuse with the help of refactoring, save and share your code to GitHub, and use breakpoints to quickly find problems in your applications.

Let's begin by examining the features of Android Studio.

In this section you explore the Android Studio Integrated Development Environment, which is also known as the IDE. Basically, the IDE is the interface between you and Android Studio. The more you know about the tools, windows, and options that are available to you in Android Studio, the faster you will be able to produce code and the more confident you will be at creating applications.

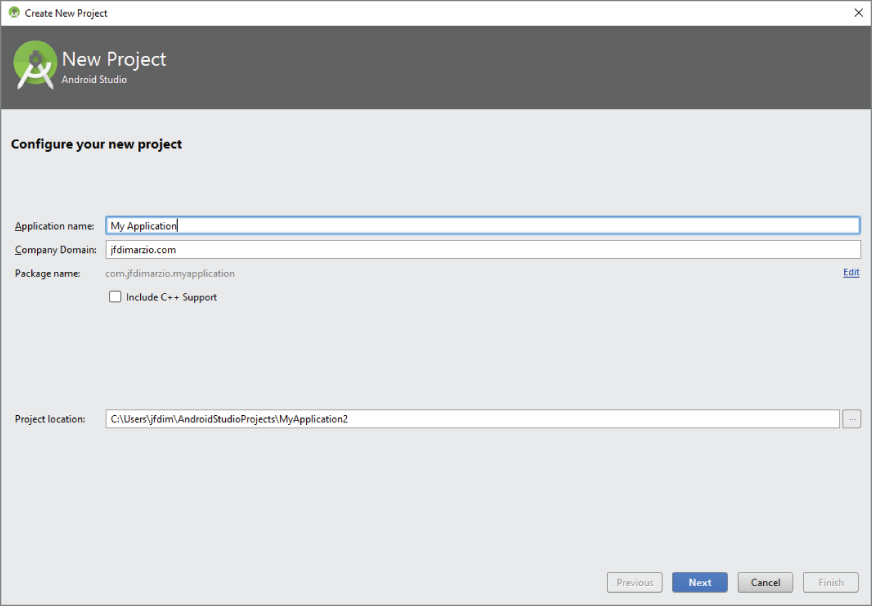

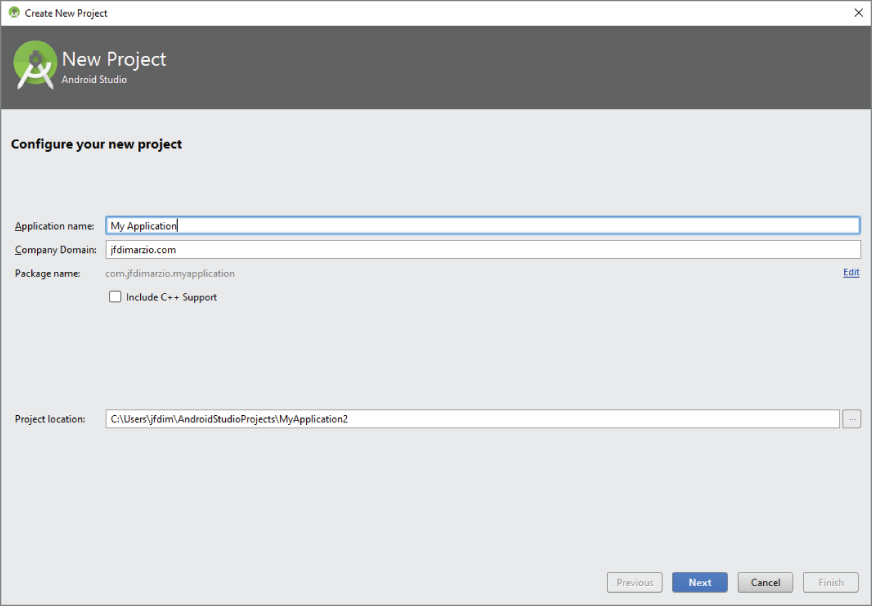

The first option you have is to name your project. Let's call this one IDEExplorer. The second option—the Company Domain—is very important because it is used to name the Java package to which your code will belong. You can type any name that you want into this field. There is no validation to check that you actually own the domain that you specify, but you should try to use a valid domain. I have used jfdimarzio.com. As you can see from the Package Name line, Android Studio automatically reverses your company domain to create the package name.

The final option on the Create New Project screen is the path to which Android Studio will save your new project. I typically accept the default here because it makes it easier for me to find projects in the future. However, feel free to specify any valid location that you want to use—it will not affect this tutorial. Click Next to continue.

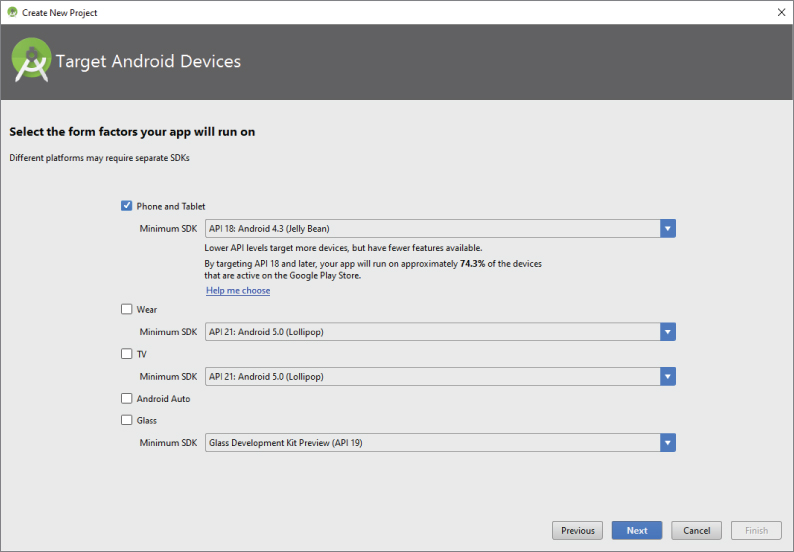

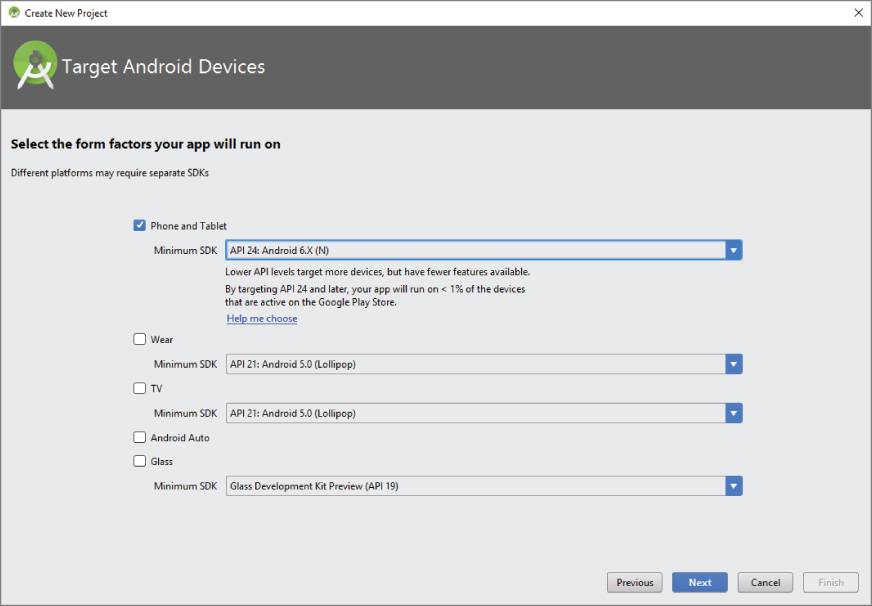

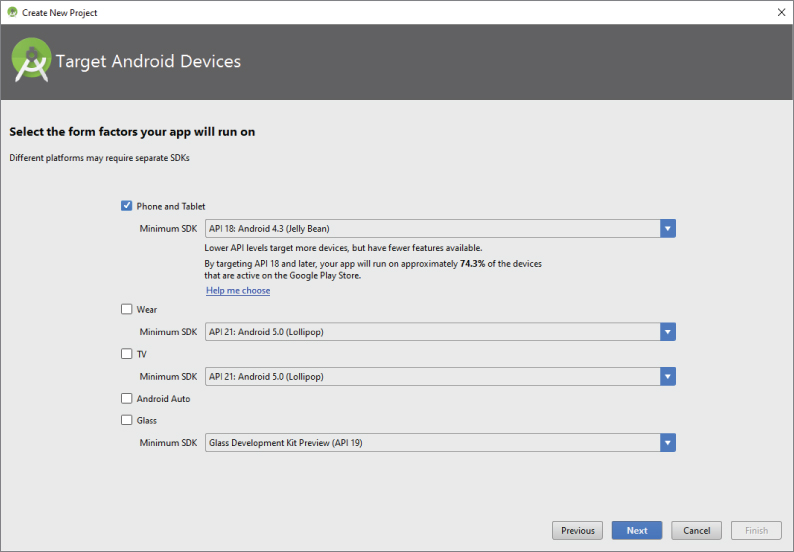

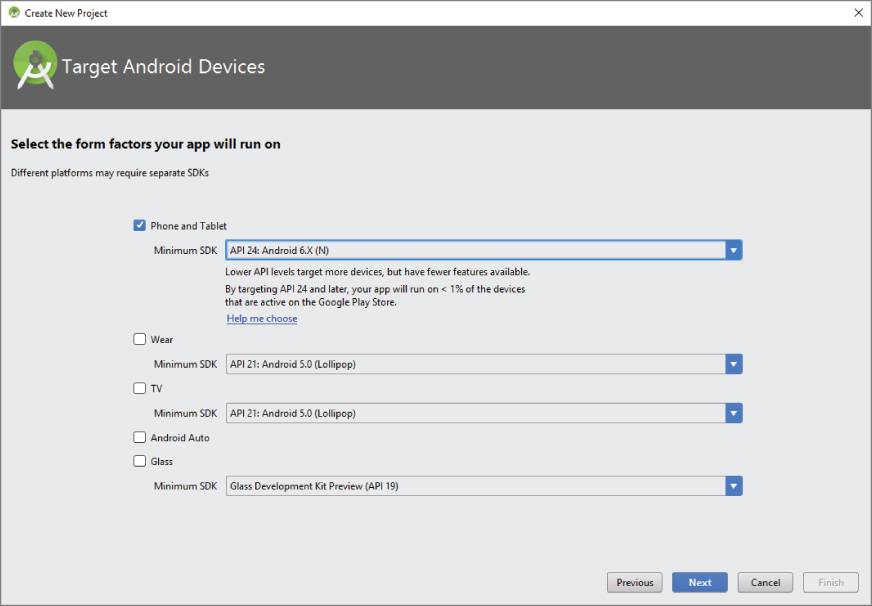

The next screen allows you to select the form factor on which your application will run (see Figure 2.3). For the purposes of this book, you exclusively use Phone and Tablet. The version of Android is Android N (or Nougat, depending on the version of the SDK you downloaded. As of the writing of this book, the name was officially announced as Nougat, but the SDK was still labeled N).

The other options on this screen allow you to create applications that run on Android Wear, Android Auto, and the elusive Google Glass. If you are feeling adventurous after reading this book, feel free to try some of these other application form factor options. For now, make sure to select Phone and Tablet and Android N and click Next to continue.

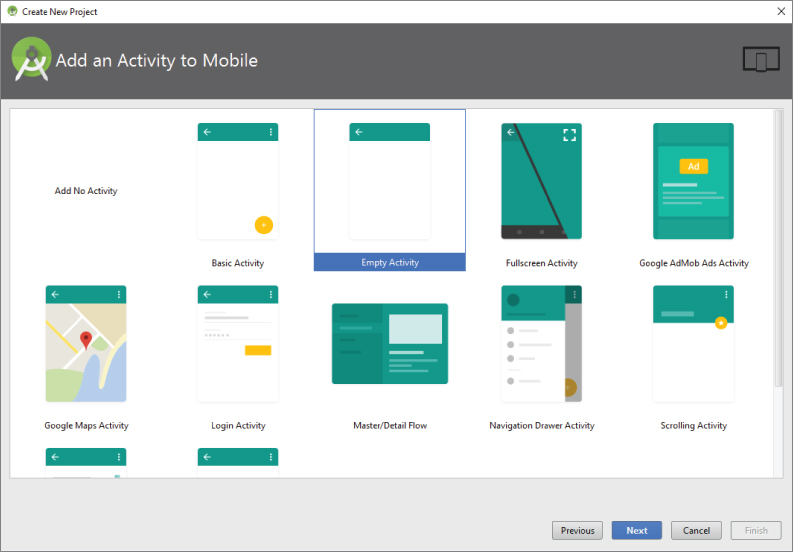

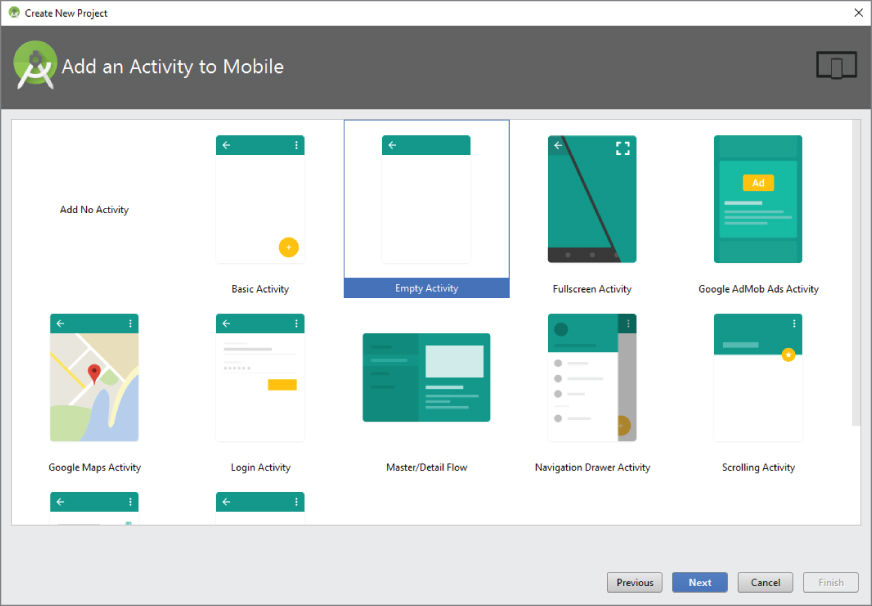

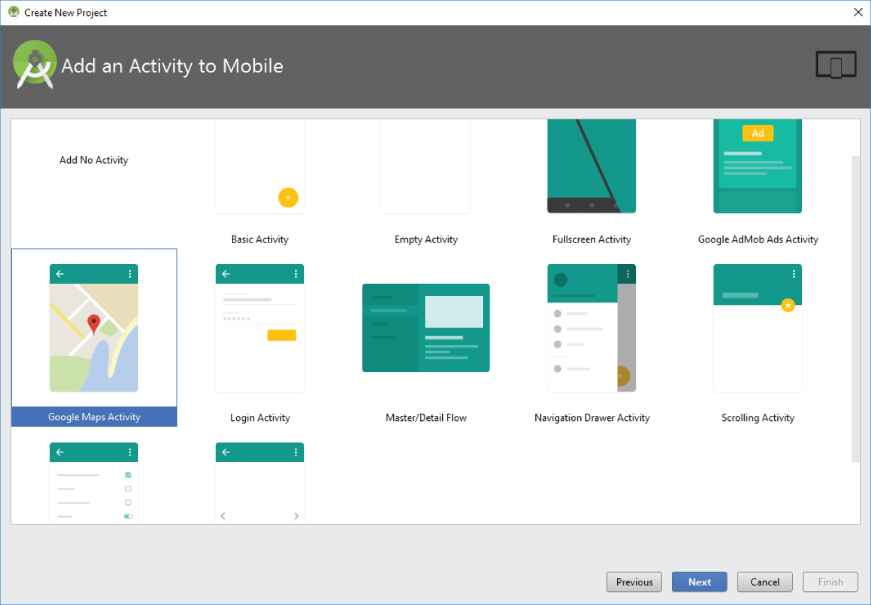

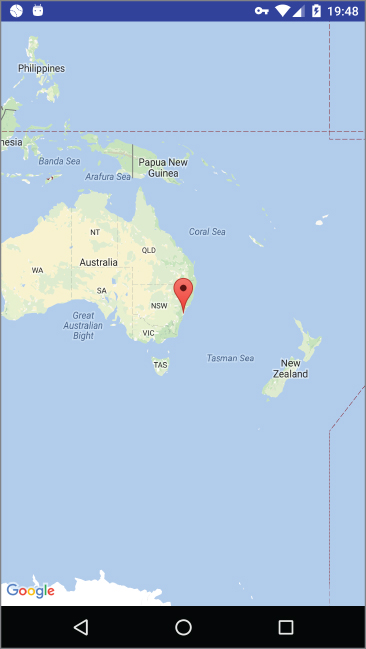

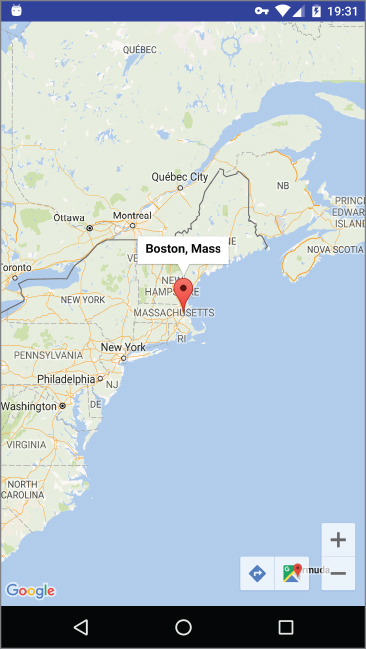

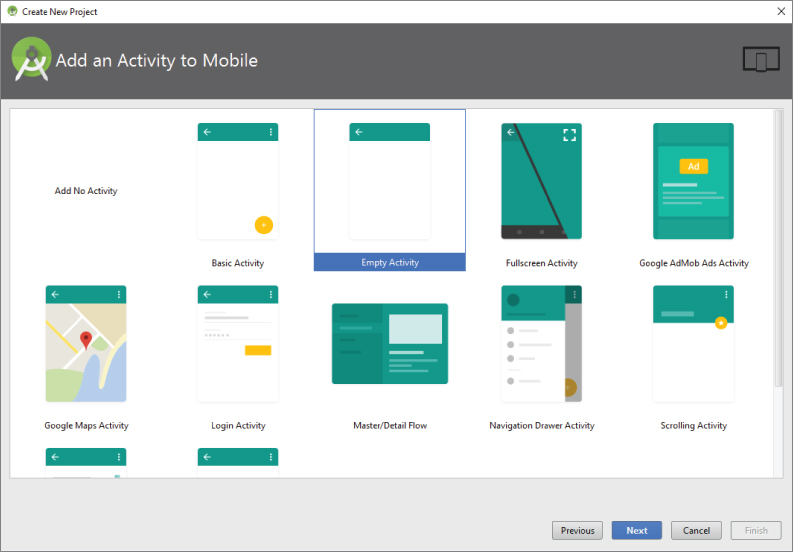

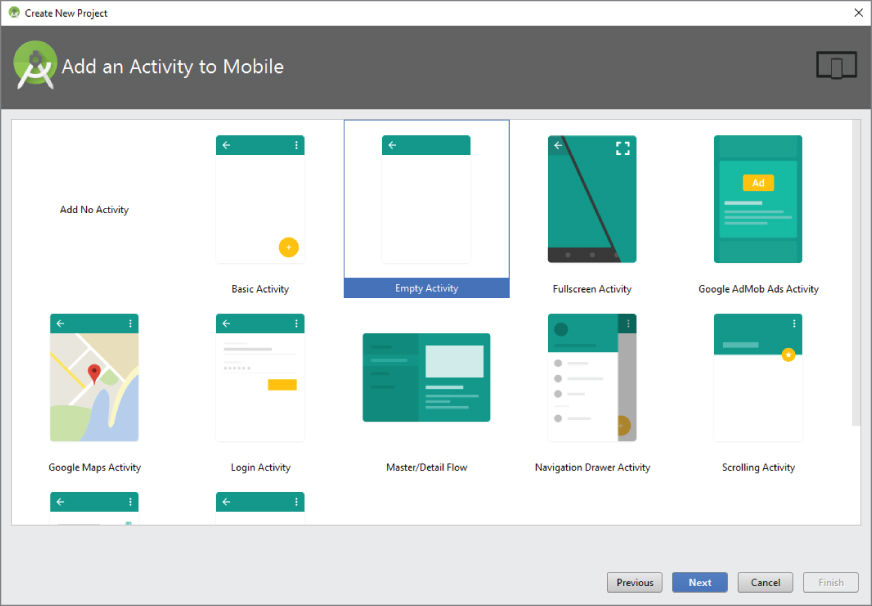

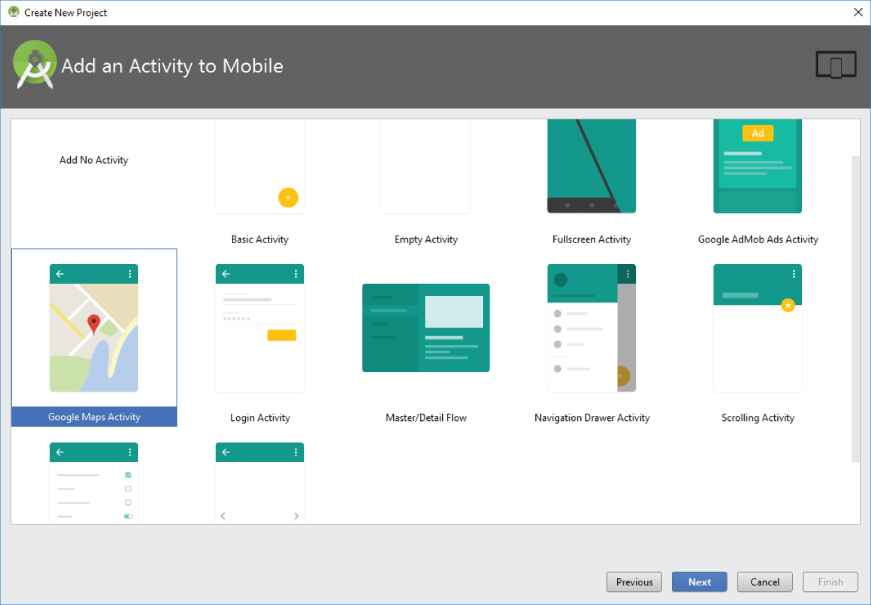

The next screen is the Add an Activity to Mobile screen, as shown in Figure 2.4. This screen is a helper that adds commonly used features to your project at the time the project is created. The options on this screen range from Add No Activity to Tabbed Activity. For example, if you were to select the Google Maps Activity option, Android Studio would create for you a project with a basic activity that contains a Google Map in it already. This can drastically cut down on the amount of time needed to create some types of applications.

The default option is Empty Activity. This is the most useful for our examples because it creates a basic activity for you, with no code in it—thus allowing you to easily follow the examples in this book.

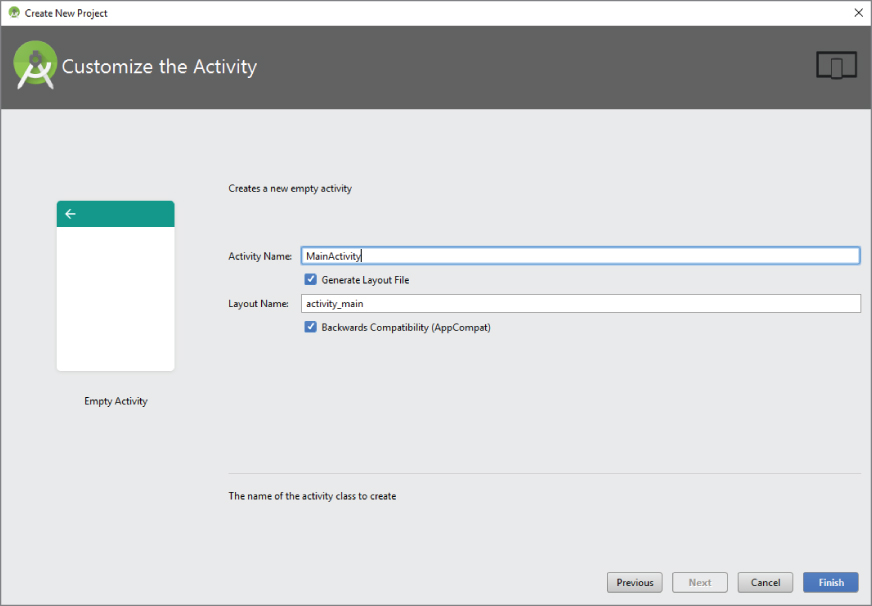

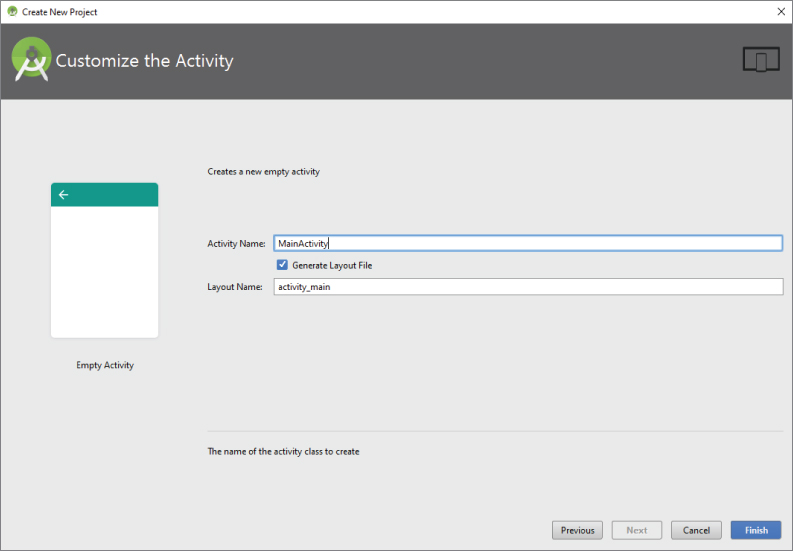

Click Next to go to the Customize the Activity screen, as shown in Figure 2.5.

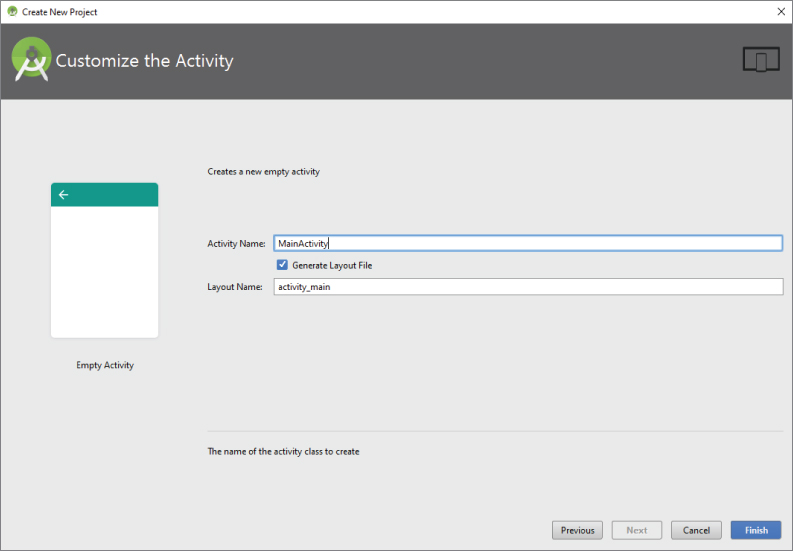

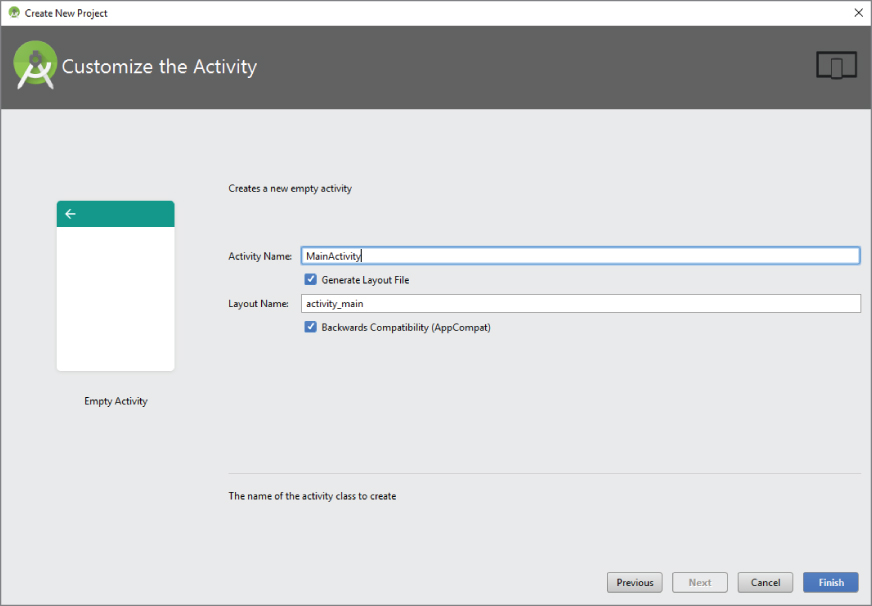

The Customize the Activity screen contains two options, one for naming your activity, and one for naming the main layout (presumably to be used by the main activity). Let's explore these two options.

MainActivity. The reason for this is to make it easier to locate the startup code for your application. If anyone else needs to look at or work with your application, they should know that the MainActivity is the starting point. All other activities can be named by their function, for example InputFormActivity or DeleteRecordActivity.activity_main layout. All other layouts should be named according to the activity that they support (activity_input, activity_delete).Click the Finish button to finish creating the project and jump into exploring the IDE.

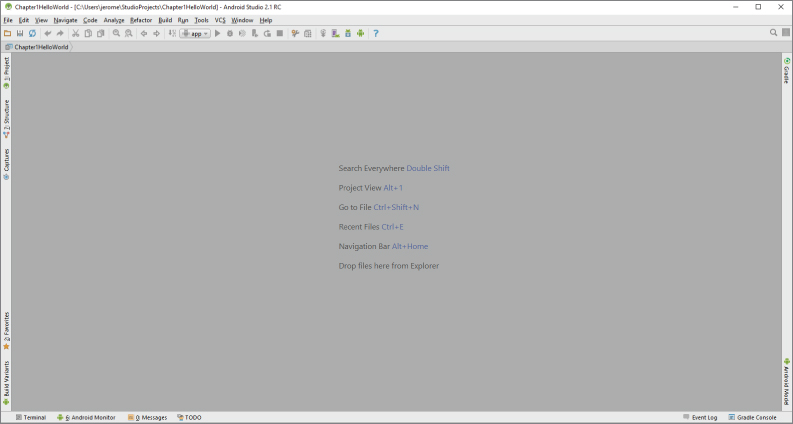

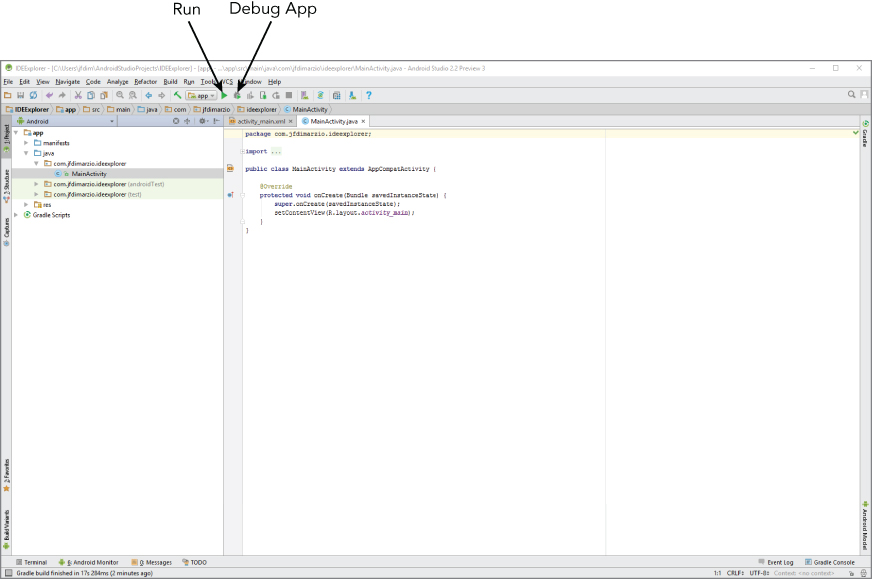

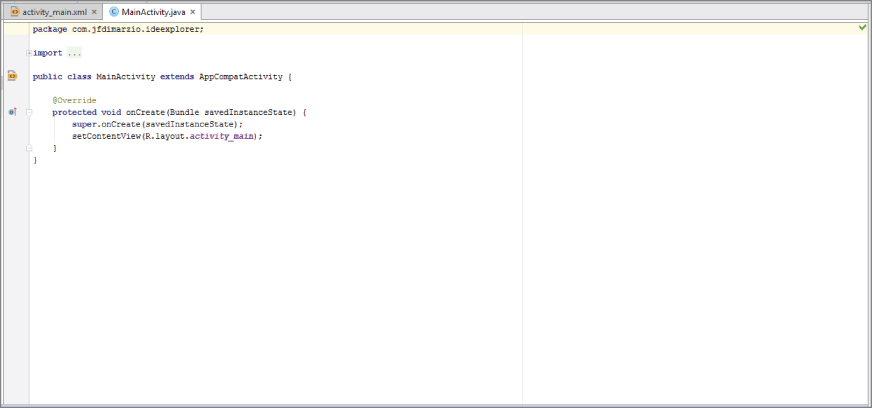

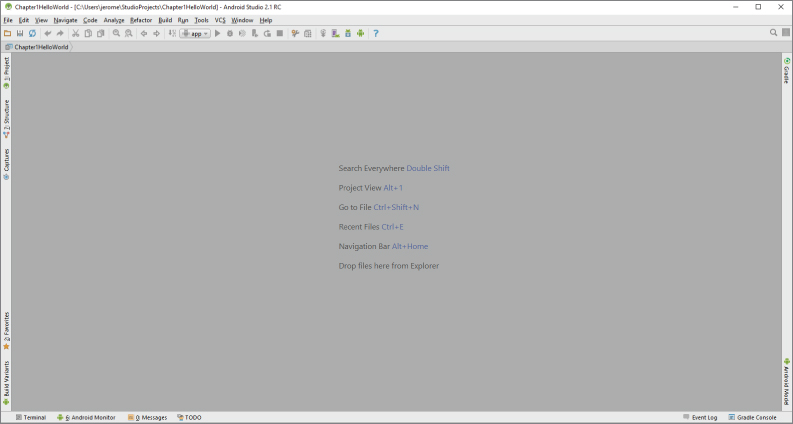

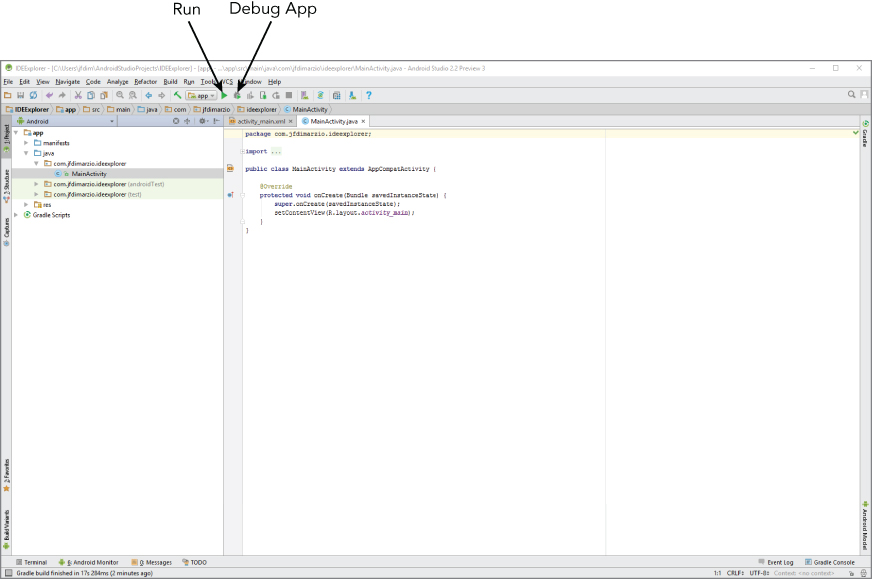

The Android Studio IDE should now be visible to you as shown in Figure 2.6.

The upper portion of the IDE represents the menu bars or ribbons. Here, as with most applications that you have used in the past, you have all of your options for interacting directly with the IDE. The most important ones to note are the green arrow, which represents the Run app option, and the green arrow with a bug behind it, which is the Debug App option. The Debug App option is arguably the one that you use the most in this book.

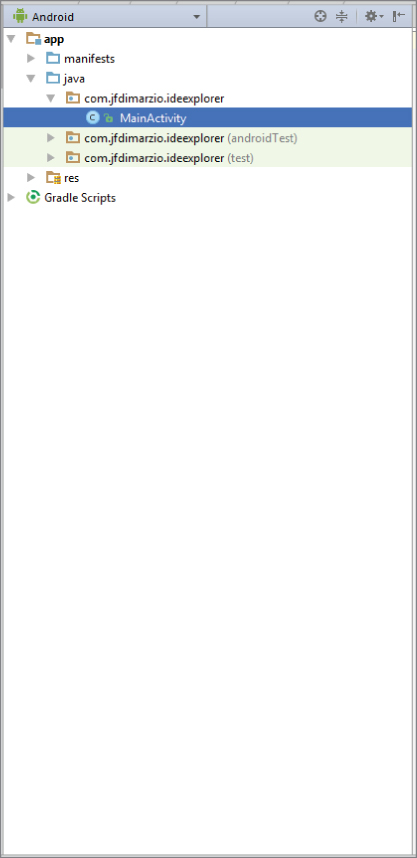

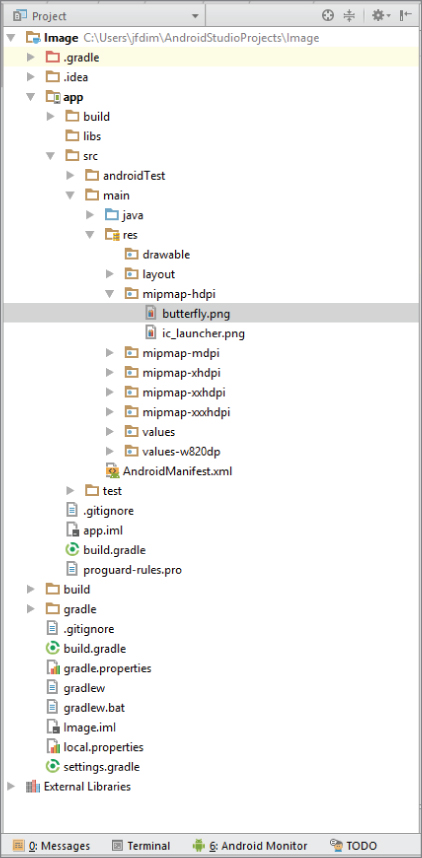

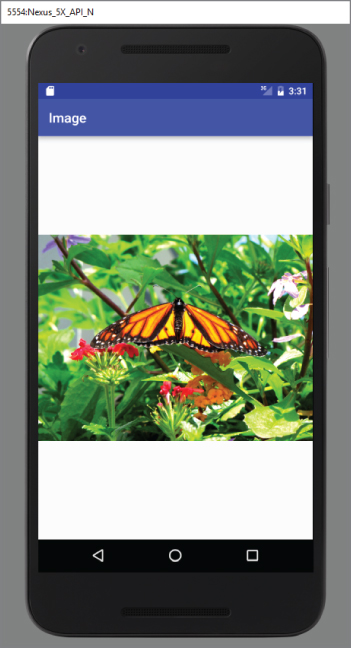

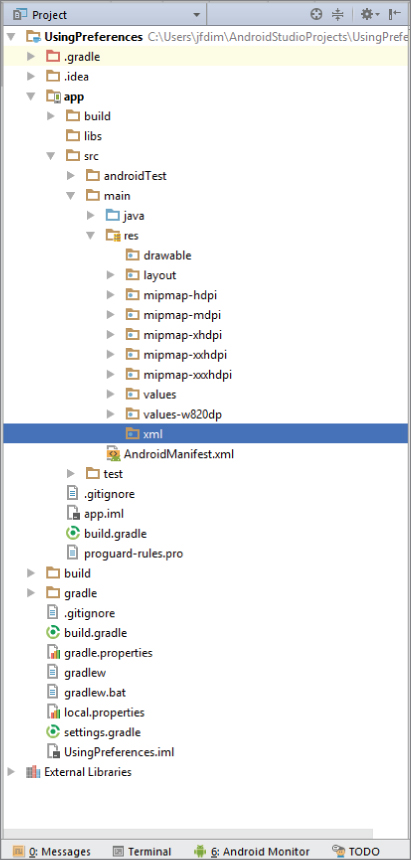

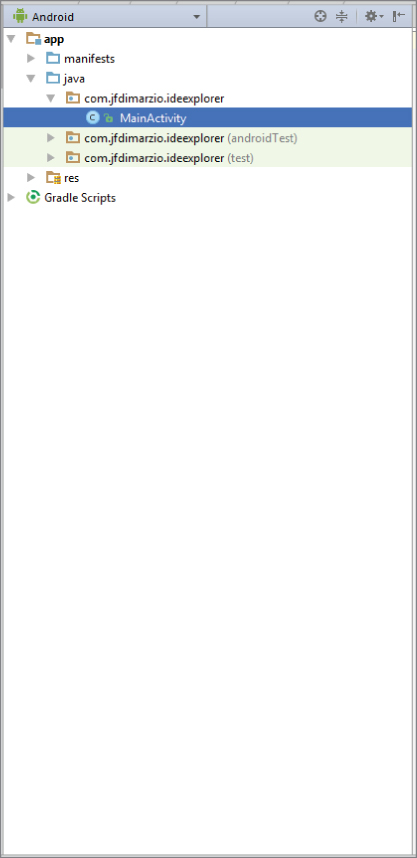

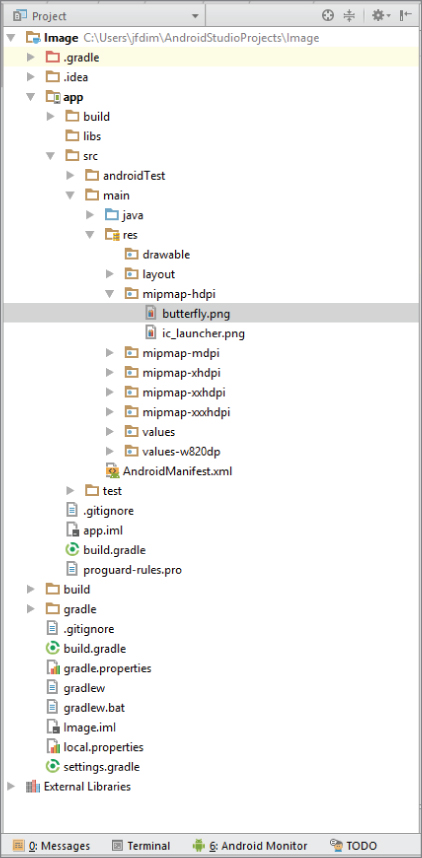

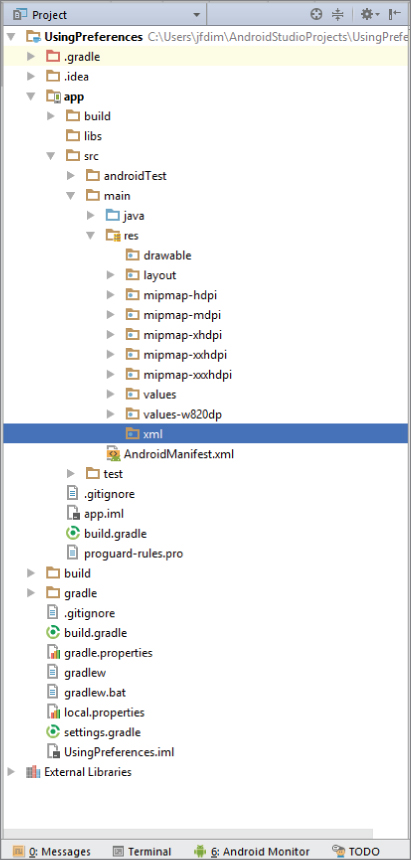

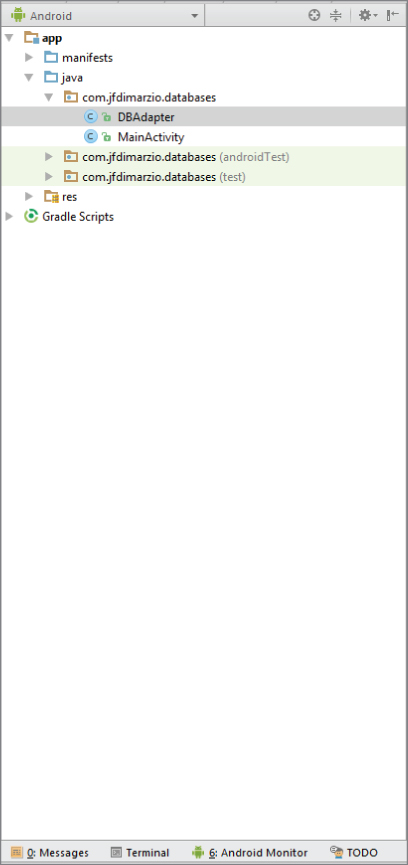

By default, the left side of the IDE shows the Project window, as shown in Figure 2.7. The Project window enables you to quickly navigate the files within your project. By default, the Project window is set to the Android view (seen just above the Project window display). To change the view, click the word Android and use the drop-down list of options to make the change. I like to keep mine on Project view when I am working.

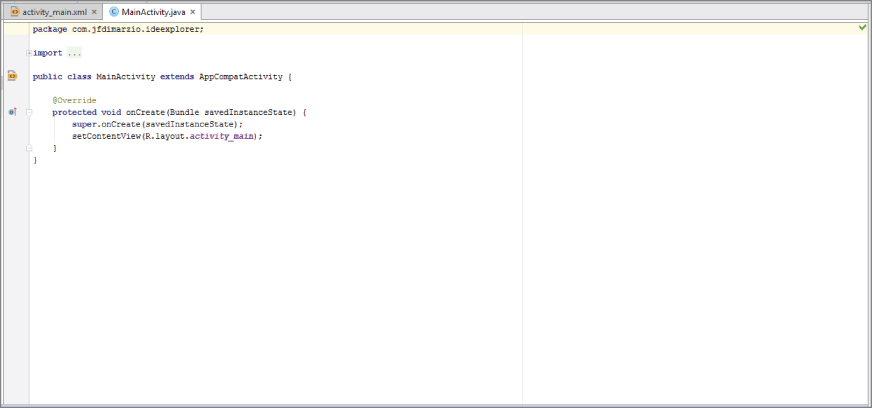

On the right side of the IDE (and taking up the largest area) are the Editor tabs (see Figure 2.8). The Editor tabs are where you write and work with your code files.

To work on a new file, simply locate the file in the Project window and double-click it to open a new Editor tab that contains that file's code. If you need to create a new file from scratch, right-click the directory into which you want to place your file, and select New  <File Type> from the context menu.

<File Type> from the context menu.

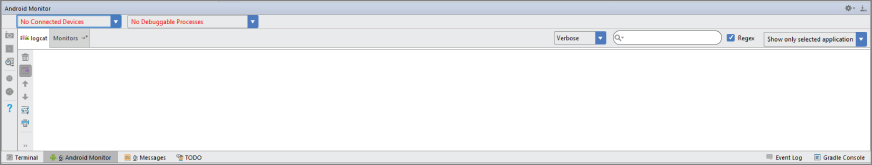

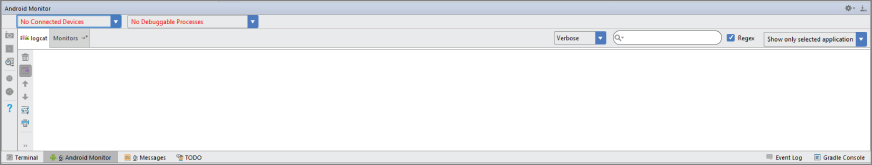

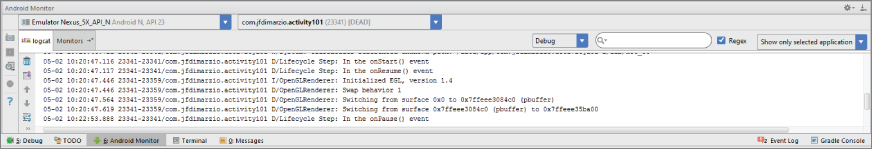

Finally, at the bottom of the IDE, you should see a button labeled Android Monitor. Click this button to open the Android Monitor (see Figure 2.9).

The Android Monitor automatically displays when you debug an application. It contains a very useful tool called logcat. Logcat displays most of the helpful messages that are output by your application while you are trying to debug it. In future chapters, you will make use of logcat—including writing custom messages to it.

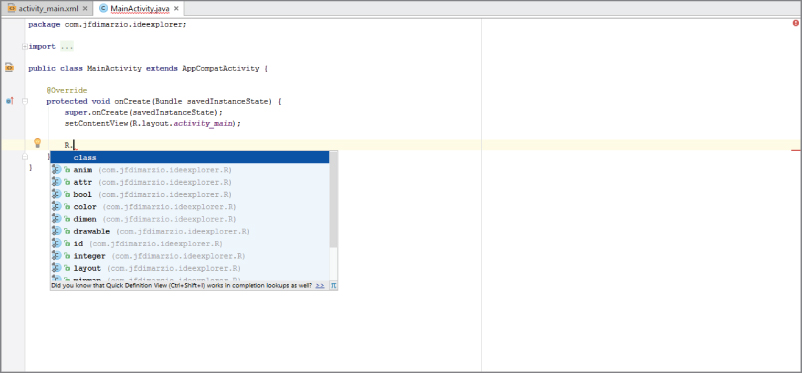

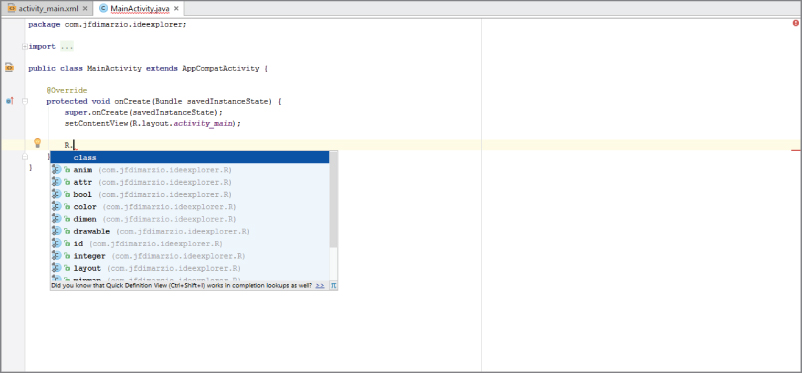

Code completion is an invaluable tool that shows you contextual options for completing the piece of code that you are trying to write. For example, in the editor tab for the MainActivity.js file, locate the line that reads

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);Place your cursor after this line and press the Enter key. On the new line, type the letter R, and then type a period, as shown here:

R.Android Studio Code Completion should display a list of values that you could use to try to complete the code statement. Figure 2.10 shows what this list might look like. This is important if you are not entirely sure of the spelling of a method call or of how to identify the different method signatures.

You can also use code completion to insert code stubs into your classes. If you are inheriting from a class that has methods you must override, code completion notifies you that there are methods that need to be overridden. With a click, it inserts the stubs of those methods into your application.

Finally, the ability to import packages is one of the Android Studio features and its code completion implementation that you will use most often while navigating the examples in this book. For example, if you were to attempt to create a variable of a type that belongs to a package that you have not imported, Android Studio recognizes this and underlines the type with a red squiggle. Set the cursor to that line and press Alt+Enter to automatically import the package into a using statement at the top of your code file.

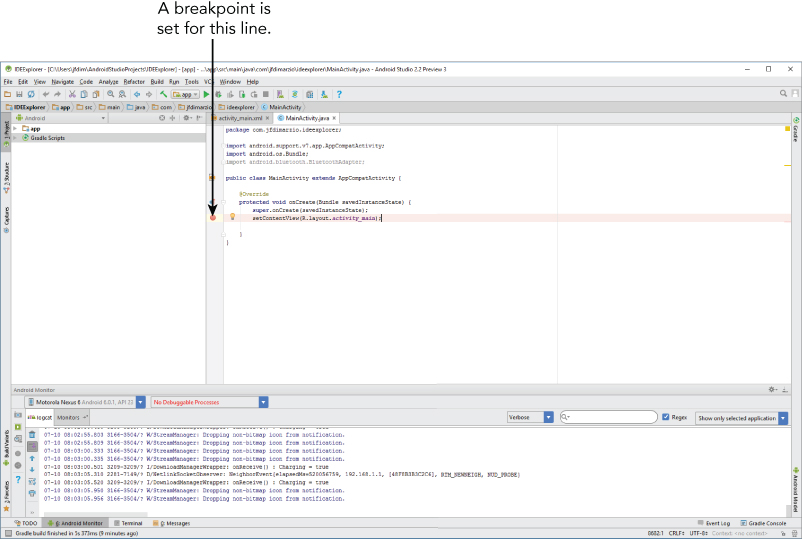

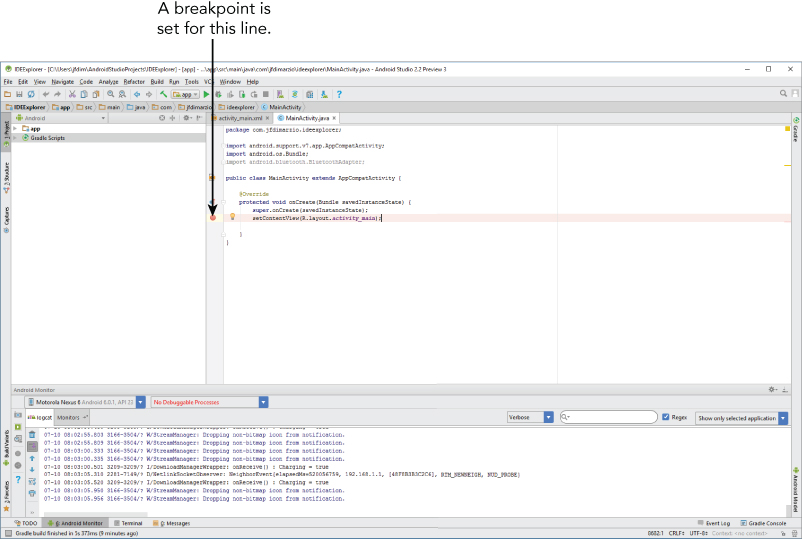

After you have built an application, you need to be able to debug it and see what is going on inside your code. One of the handiest ways to be able to see inside your code it through the use of breakpoints. Breakpoints allow you to pause the execution of your code at specific locations and see what is going on (or what is going wrong). Let's take a look at how to use breakpoints in Android Studio.

Breakpoints are a mechanism by which you can tell Android Studio to temporarily pause execution of your code, which allows you to examine the condition of your application. This means that you can check on the values of variables in your application while you are debugging it. Also, you can check whether certain lines of code are being executed as expected—or at all.

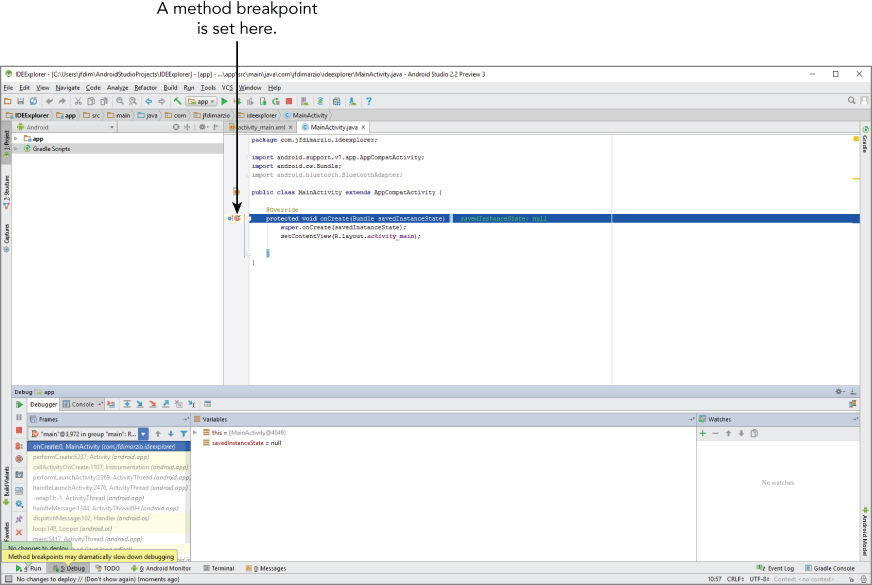

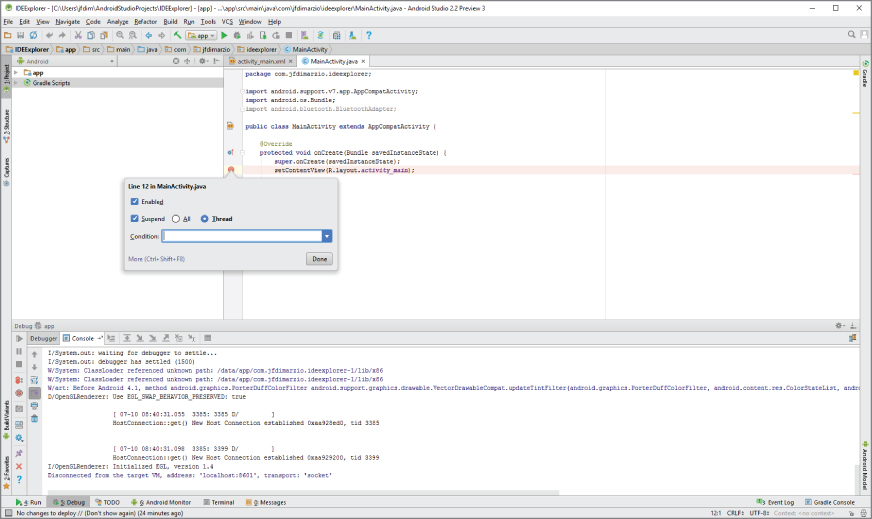

To tell Android Studio that you want to examine a specific line of code during debugging, you must set a breakpoint at that line. Click the margin of the editor tab next to line of code you want to break at, to set a breakpoint. A red circle is placed in the margin, and the corresponding line is highlighted in red, as shown in Figure 2.11.

You can also set a breakpoint by placing your cursor in the line of code where you want it to break and clicking Run  Toggle Line Breakpoint. Notice that the term used is toggle, which means that any breakpoints you set can be turned off the same way you turn them on. Simply click an existing breakpoint to remove it from your code.

Toggle Line Breakpoint. Notice that the term used is toggle, which means that any breakpoints you set can be turned off the same way you turn them on. Simply click an existing breakpoint to remove it from your code.

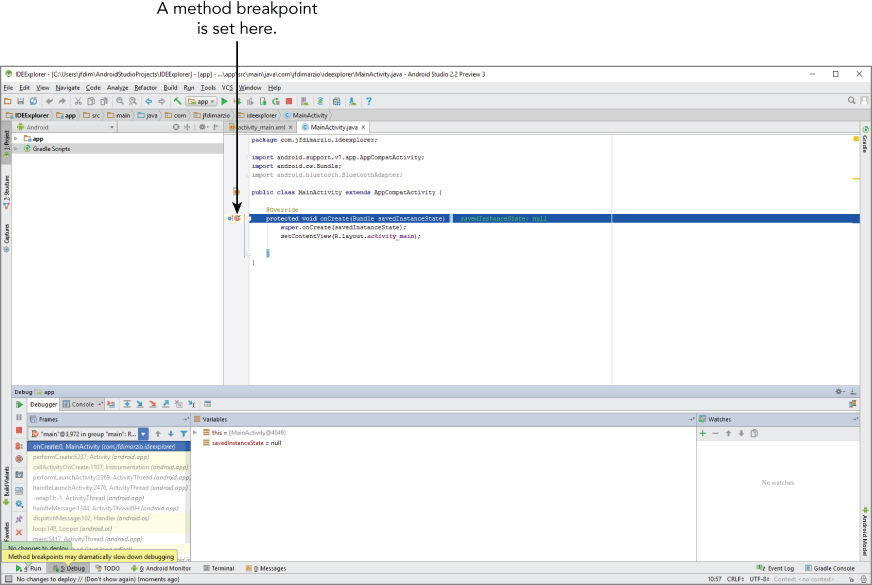

Let's say that you do not know the exact line of code where you want the break to be. You might want to check on the condition of your code when a specific method is called. You can set a method breakpoint by selecting Run  Toggle Method Breakpoint. A method breakpoint is represented by a red circle containing four dots placed at the method signature, as shown in Figure 2.12.

Toggle Method Breakpoint. A method breakpoint is represented by a red circle containing four dots placed at the method signature, as shown in Figure 2.12.

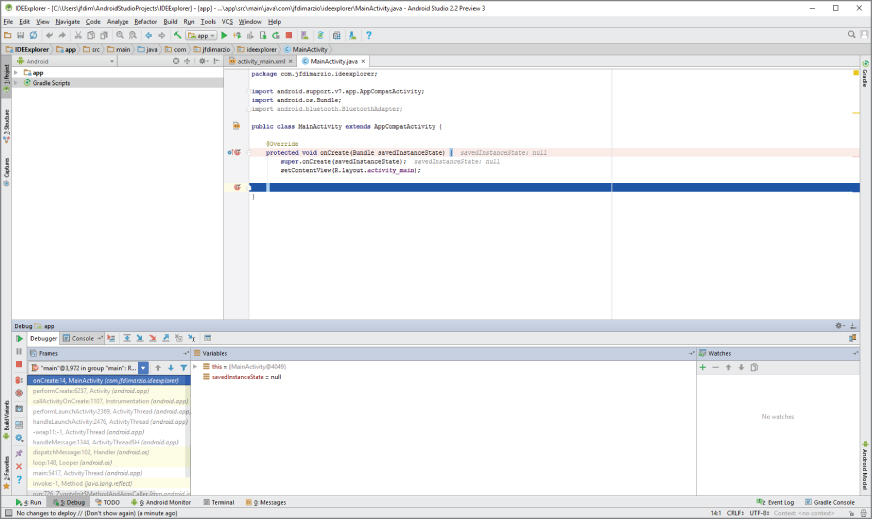

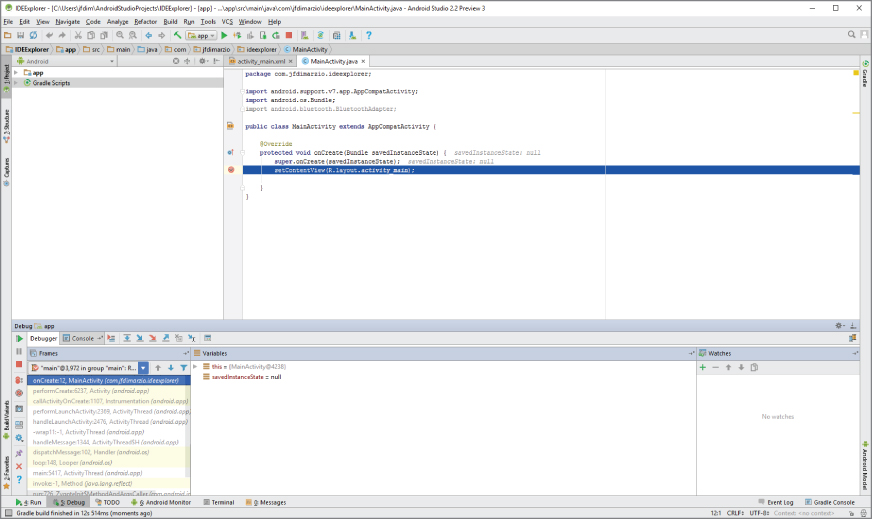

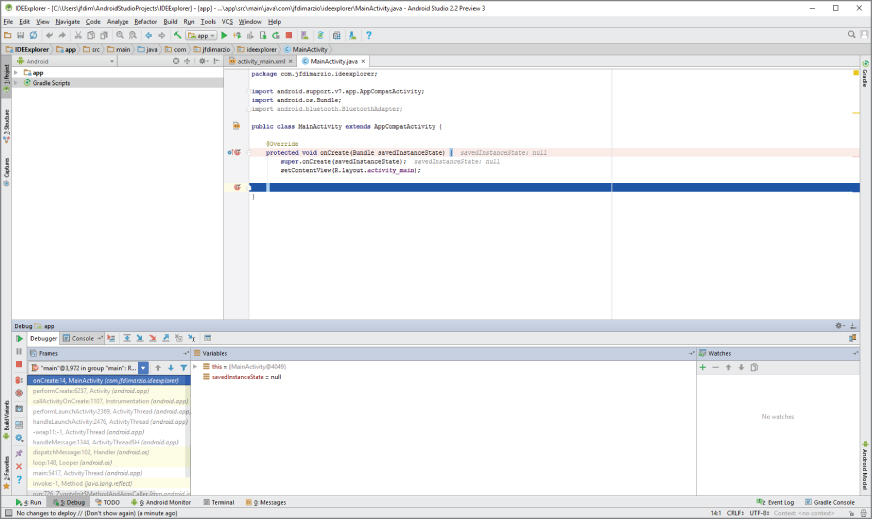

Notice in the lower left-hand area of Figure 2.12 that Android Studio has issued a warning that method breakpoints can dramatically slow down debugging. This is because method breakpoints do more than simple breakpoints in their default state. By default, method breakpoints are set apart from simple breakpoints. Android Studio pauses execution when the method is hit, and it also automatically sets a corresponding breakpoint and pauses at the end of the method (as shown in Figure 2.13).

Thus far, I've discussed simple and method breakpoints. However, there are two other types of breakpoints that you examine in this section: temporary breakpoints and conditional breakpoints.

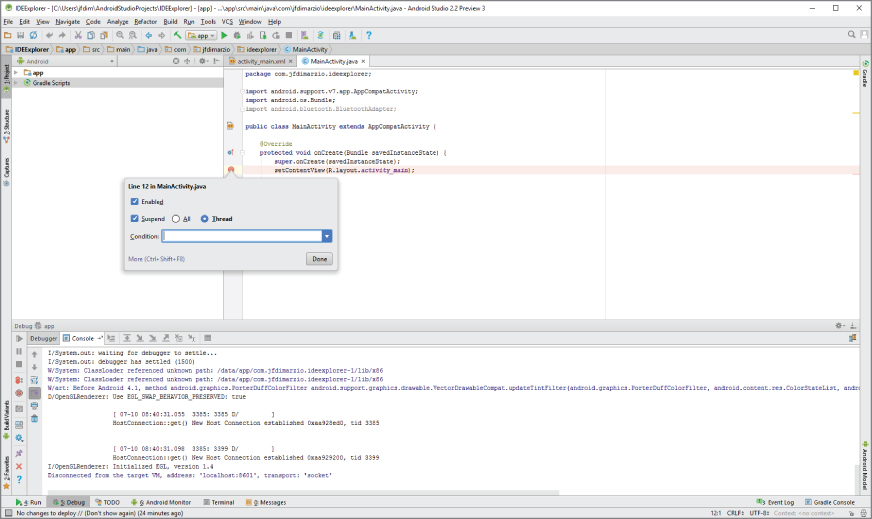

A temporary breakpoint is useful when you are trying to debug a large loop, or you just want to make sure a line of code is being hit during execution. To set a temporary breakpoint, place your cursor at the location in the code where you want it to break and select Run  Toggle Temporary Line Breakpoint. Notice that a red circle containing a 1 is now placed in the margin (once you set the conditions as shown in Figure 2.14).

Toggle Temporary Line Breakpoint. Notice that a red circle containing a 1 is now placed in the margin (once you set the conditions as shown in Figure 2.14).

The 1 in the red circle represents the fact that Android Studio only stops at this breakpoint the first time your code enters it. After that, the line is executed as though there is no breakpoint set. This can be very useful if you want to ensure a line within a loop is being hit, but you don't want to stop at the line every time it is executed.

However, let's say that you want to ensure that a line within a loop is only being called when a specific variable is set to true (or something similarly complex). In such a case, you can use a conditional breakpoint.

A condition breakpoint is a breakpoint at which Android Studio only pauses when specific conditions are met. To set a conditional breakpoint, first set a simple breakpoint at the line of code you want to examine, then right-click the simple breakpoint to bring up the condition context menu (refer to Figure 2.14).

From here you can set conditions that tell Android Studio when to pause at a breakpoint. For example, you can tell Android Studio to only pause at a line of code when your variable named foo equals true. You would then set the condition in the breakpoint to

foo == trueConditional breakpoints are extremely useful in diagnosing intermittent issues in complex code blocks.

While in debug mode, Android Studio pauses at any breakpoint that you have set. That is, as long as a breakpoint has been set on a reachable line of code (a line of code that would be executed by system), Android Studio halts execution at that line until you tell it to continue.

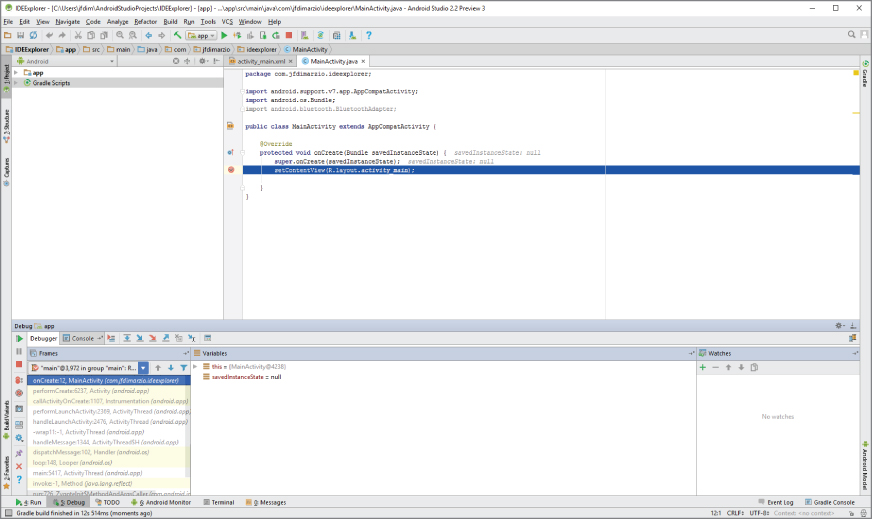

When Android Studio hits, and pauses at, a breakpoint, the red circle in the margin next to the corresponding line of code changes to a circle with a check mark (see Figure 2.15).

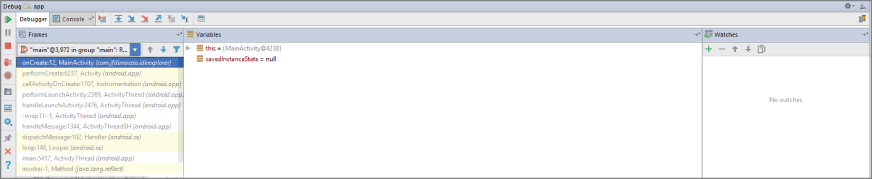

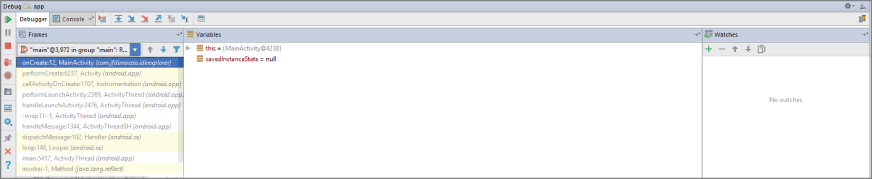

Once a breakpoint has been hit, the debug window opens at the bottom of Android Studio, as shown in Figure 2.16. The debug window contains many of the tools you use to navigate around your code.

Notice the navigation buttons located in the menu bar of the debug window. The most commonly used are Step Over and Step Into. Step Over advances you to the line of code that immediately follows the one at which you are currently paused. This means that if you are paused at a method call, and you press Step Over, Android Studio executes the method call without pausing and then pauses again when execution reached the next line. However, what if an exception happens in that method call and execution never reaches the next line of code? For these situations use Step Into.

Step Into follows execution wherever it leads in the code. Therefore, if you are paused at a method call and click Step Into, Android Studio will shift the view to the method call and pause execution at the first line of code within that method. This allows you to then follow the execution of that method line-by-line before it returns to the calling block.

After you have created, and fully debugged, your application, you might want to deploy it to the Google Store for others to enjoy. The following sections outline the steps for publishing your applications.

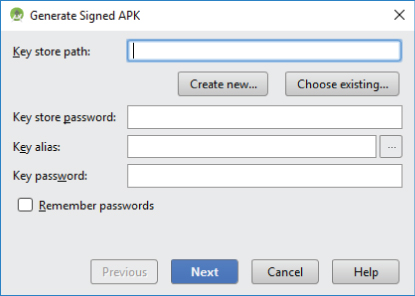

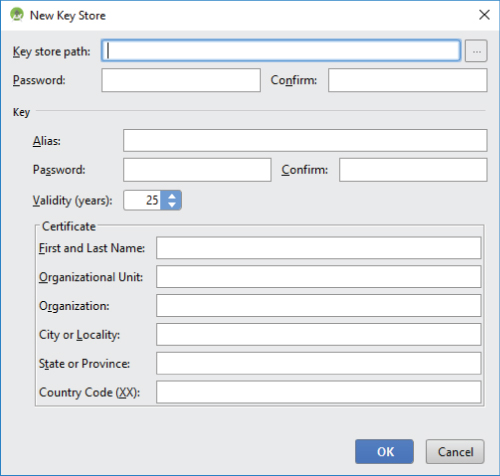

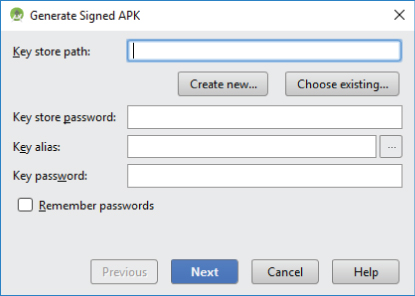

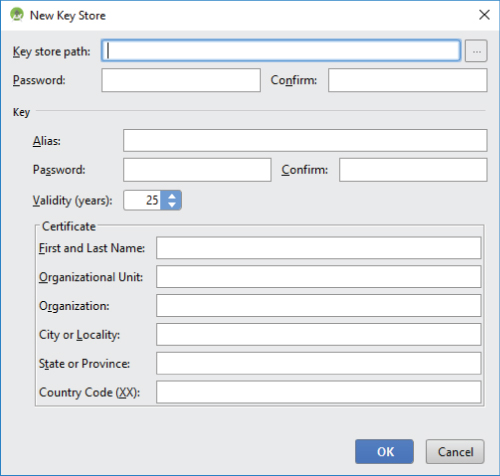

To publish your finished application on the Google Play Store, you must generate a signed APK (the Android application package). The APK is the compiled, executable version of your application. Signing it is much like signing your name to a document. The signature identifies the app's developer to Google and the users who install your application. More importantly, unless your Android Studio is in developer mode, unsigned applications will not run. Use the following steps to generate a signed APK:

Generate Signed APK from the Menu bar to bring up the Generate Signed APK window as shown in Figure 2.17.

Generate Signed APK from the Menu bar to bring up the Generate Signed APK window as shown in Figure 2.17.

Notice that there are two places for a password. These are the passwords for your key store and your key, respectively. Because a key store can hold multiple keys, it requires a separate password than that of the key for a specific app.

Now that you have a signed APK, you can upload it to the Google Play Store using the developer console at https://play.google.com/apps/publish/.

Android Studio is a powerful IDE that contains many tools. In this chapter you learned how to navigate the different areas of the Android Studio IDE, such as the Project window and the Editor tabs. You also learned how to set breakpoints and navigate through paused code.

You can find answers to the exercises in the appendix.

| TOPIC | KEY POINTS |

| Android Studio IDE | Create a new project |

| Name the Java package | |

| Name the main entry point for your application | |

| Code Completion | Provides contextual information for completing your code |

| Breakpoints | Paused only while in debug mode |

| Simple | |

| Temporary | |

| Method | |

| Conditional |

An Android application can have zero or more activities. Typically, applications have one or more activities. The main purpose of an activity is to interact with the user. From the moment an activity appears on the screen to the moment it is hidden, it goes through a number of stages. These stages are known as an activity's life cycle. Understanding the life cycle of an activity is vital to ensuring that your application works correctly. In addition to activities, Android N also supports fragments, a feature that was introduced for tablets in Android 3.0 and for phones in Android 4.0. Think of fragments as “miniature” activities that can be grouped to form an activity. In this chapter, you find out how activities and fragments work together.

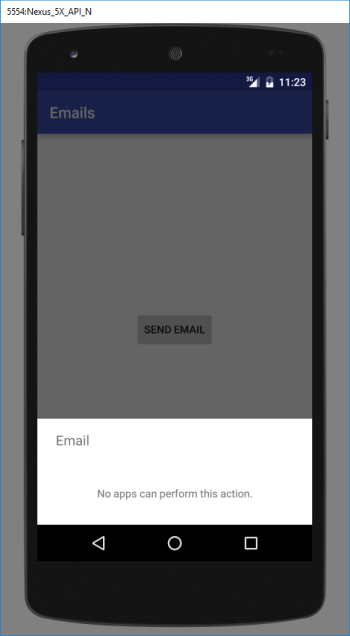

Apart from activities, another unique concept in Android is that of an intent. An intent is basically the “glue” that enables activities from different applications to work together seamlessly, ensuring that tasks can be performed as though they all belong to one single application. Later in this chapter, you learn more about this very important concept and how you can use it to call built-in applications such as the Browser, Phone, Maps, and more.

This chapter begins by showing you how to create an activity. To create an activity, you create a Java class that extends the Activity base class:

package com.jfdimarzio.chapter1helloworld;

import android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivity;

import android.os.Bundle;

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

}

}Your activity class loads its user interface (UI) component using the XML file defined in your res/layout folder. In this example, you would load the UI from the main.xml file:

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);Every activity you have in your application must be declared in your AndroidManifest.xml file, like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android

package="com.jfdimarzio.chapter1helloworld">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@style/AppTheme">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

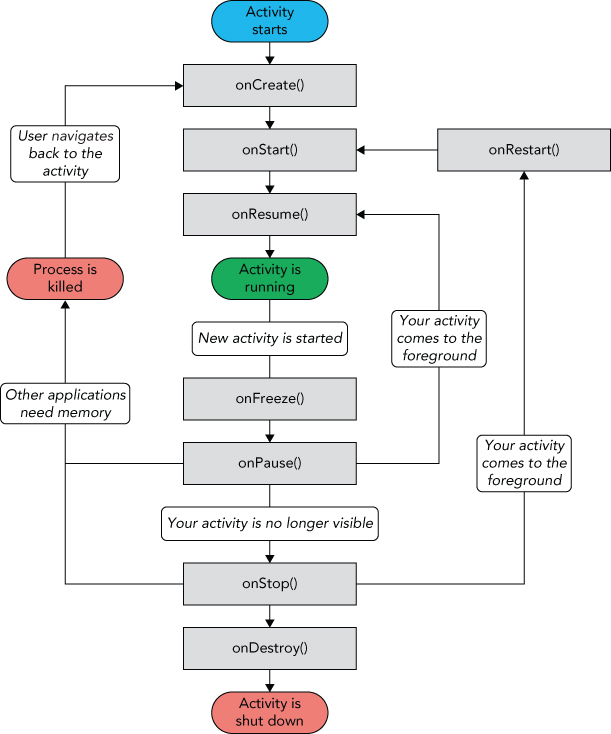

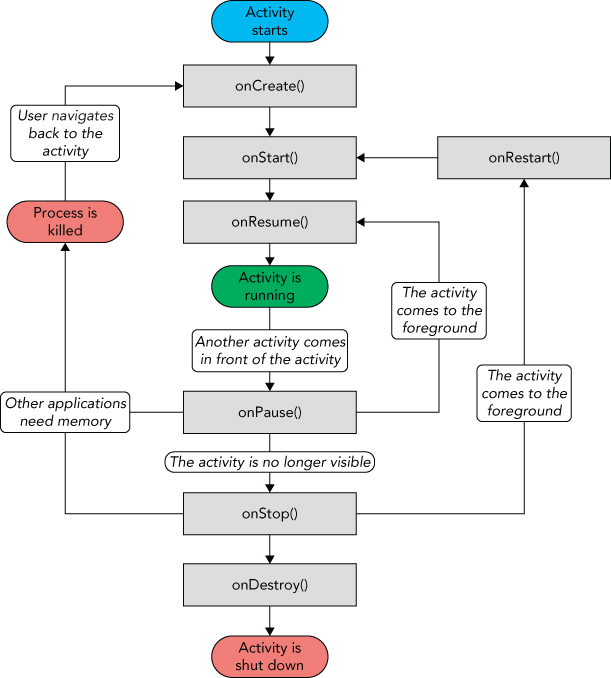

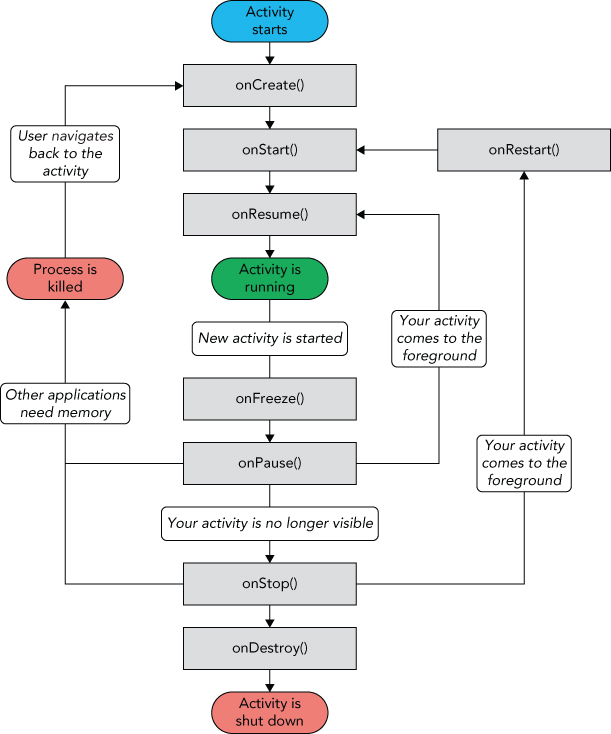

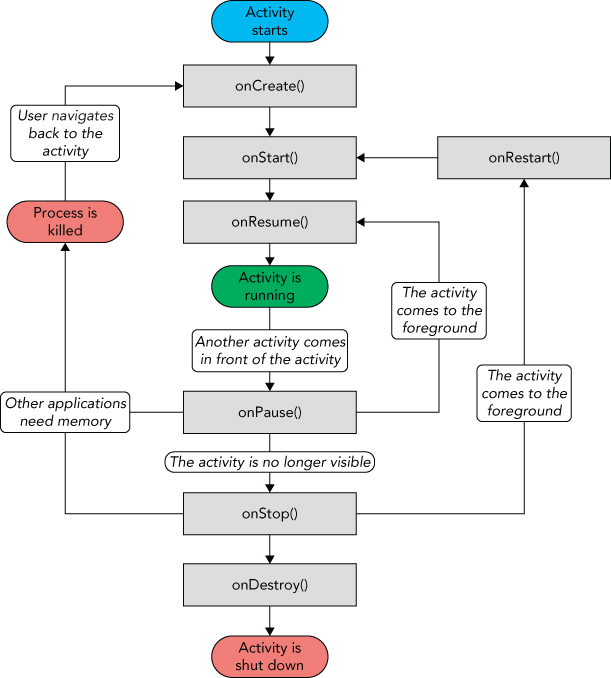

</manifest>The Activity base class defines a series of events that govern the life cycle of an activity. Figure 3.1 shows the lifecycle of an Activity.

The Activity class defines the following events:

onCreate()—Called when the activity is first createdonStart()—Called when the activity becomes visible to the useronResume()—Called when the activity starts interacting with the useronPause()—Called when the current activity is being paused and the previous activity is being resumedonStop()—Called when the activity is no longer visible to the useronDestroy()—Called before the activity is destroyed by the system (either manually or by the system to conserve memory)onRestart()—Called when the activity has been stopped and is restarting againBy default, the activity created for you contains the onCreate() event. Within this event handler is the code that helps to display the UI elements of your screen.

Figure 3.2 shows the life cycle of an activity and the various stages it goes through—from when the activity is started until it ends.

The best way to understand the various stages of an activity is to create a new project, implement the various events, and then subject the activity to various user interactions.

By default, an activity is themed to the default Android theme. However, there has been a push in recent years to adopt a new theme known as Material. The Material theme has a much more modern and clean look to it.

There are two versions of the Material theme available to Android developers: Material Light and Material Dark. Either of these themes can be applied from the AndroidManifest.xml.

To apply one of the Material themes to an activity, simply modify the <Application> element in the AndroidManifest.xml file by changing the default android:theme attribute. (Please be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.)

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

package="com.jfdimarzio.activity101">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@android:style/Theme.Material">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

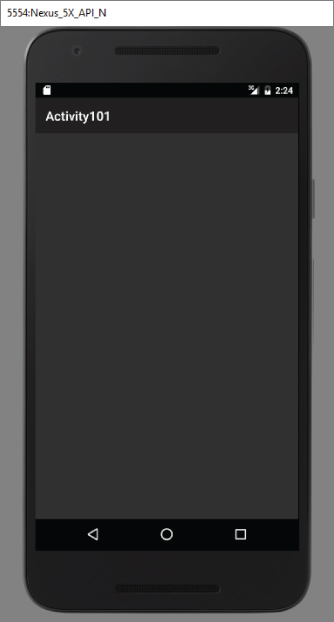

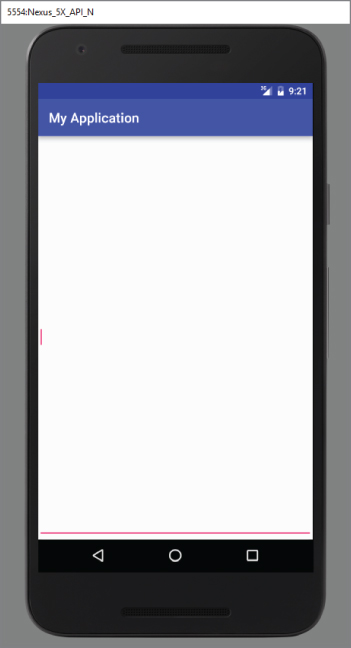

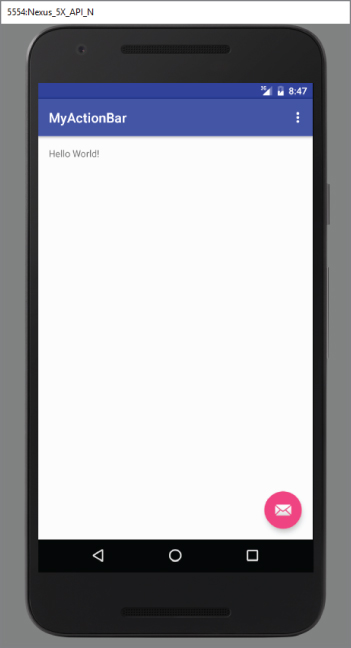

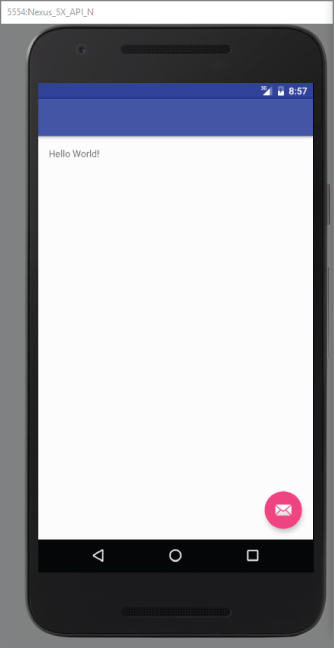

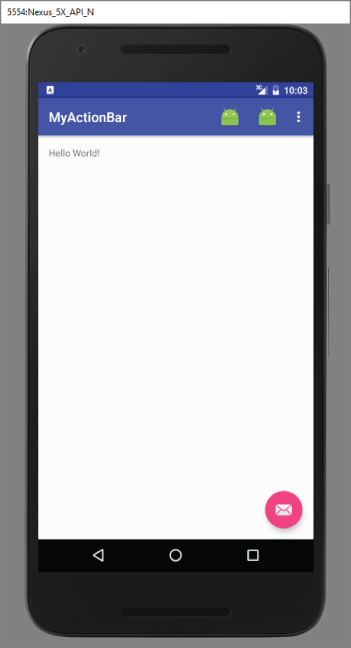

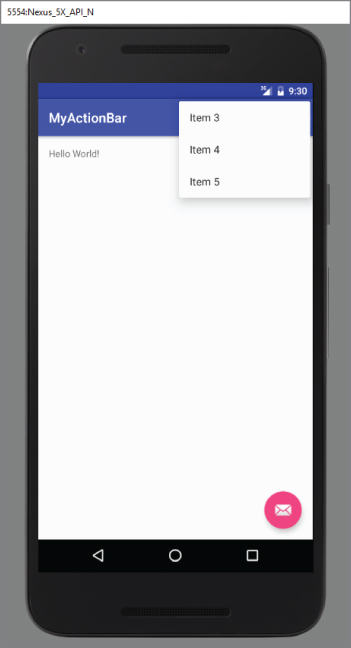

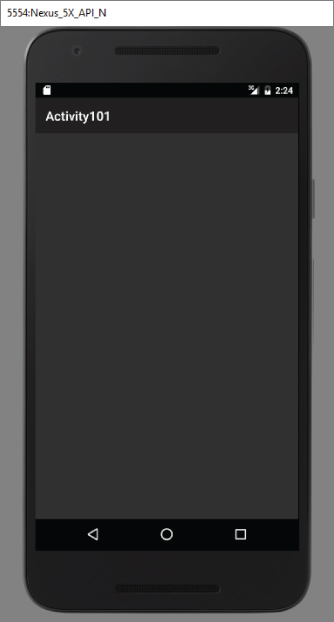

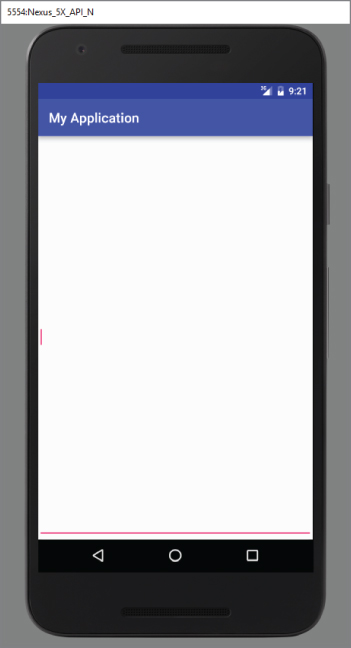

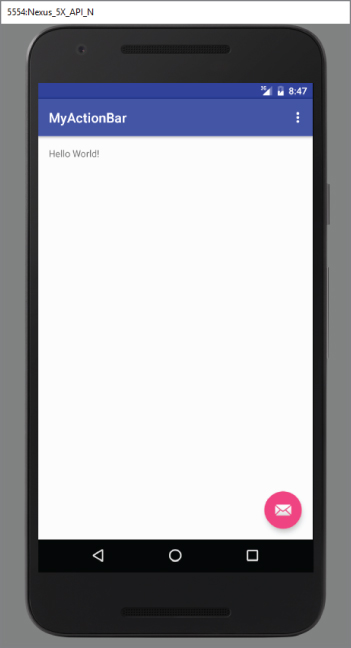

</manifest>Changing the default theme to @android:style/Theme.Material, as in the highlighted code in the preceding snippet, applies the Material Dark theme and gives your application a darker look as shown in Figure 3.4.

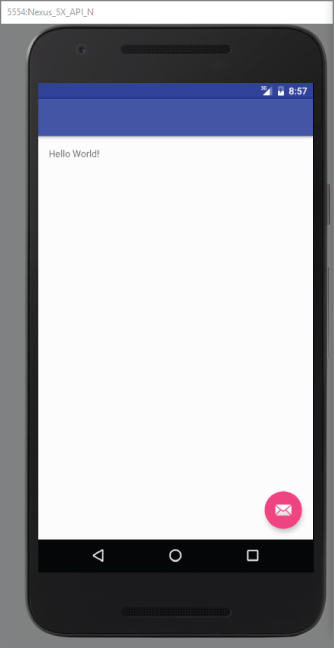

You can also hide the title of an activity if desired (such as when you just want to display a status update to the user). To do so, use the requestWindowFeature() method and pass it the Window.FEATURE_NO_TITLE constant, like this:

import android.support.v7.app.AppCompatActivity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.Window;

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

requestWindowFeature(Window.FEATURE_NO_TITLE);

}

}Now you need to change the theme in the AndroidManifest.xml to a theme that has no title bar. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.

package com.jfdimarzio.activity101;

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

package="com.jfdimarzio.activity101">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@android:style/Theme.NoTitleBar">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

</manifest>This hides the title bar, as shown in Figure 3.5.

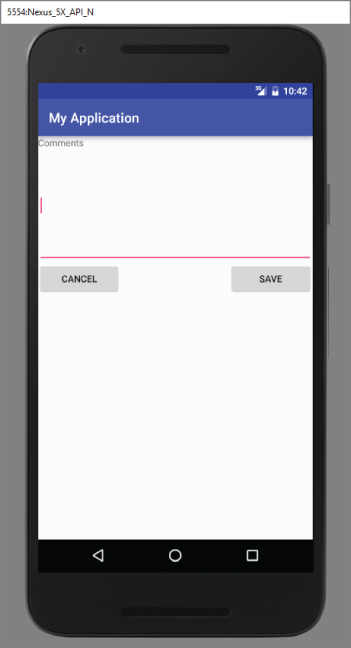

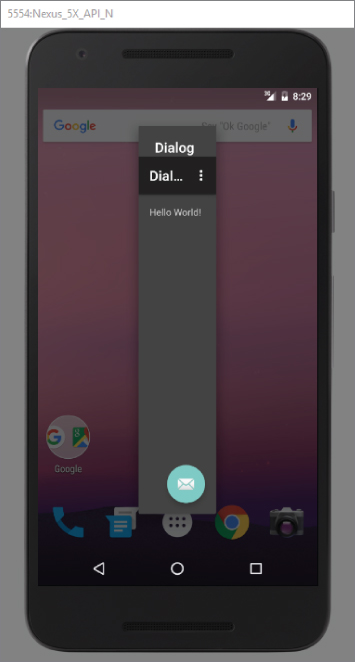

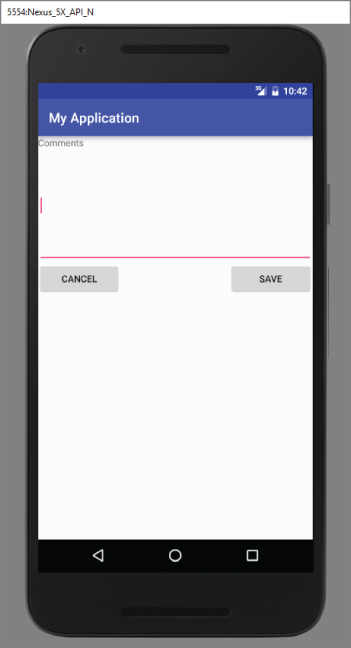

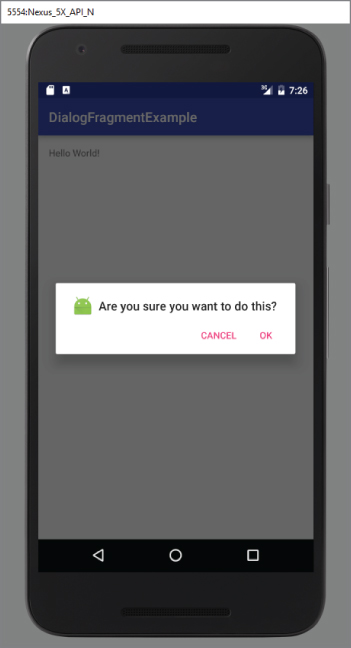

There are times when you need to display a dialog window to get a confirmation from the user. In this case, you can override the onCreateDialog() protected method defined in the Activity base class to display a dialog window. The following Try It Out shows you how.

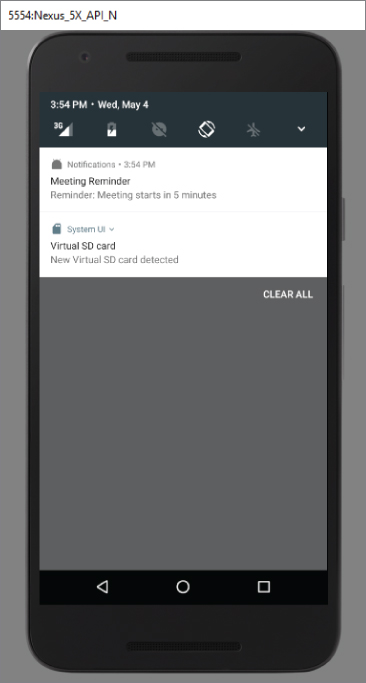

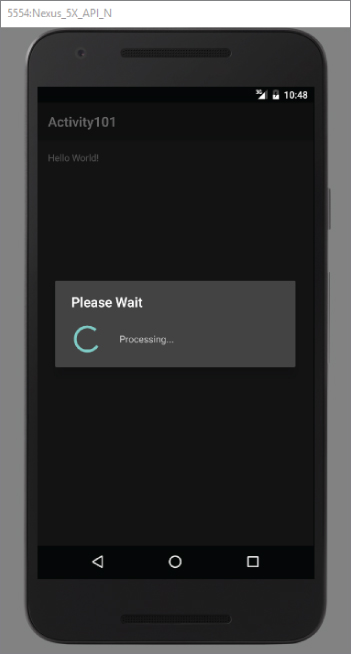

One common UI feature in an Android device is the “Please wait” dialog that you typically see when an application is performing a long-running task. For example, the application might be logging in to a server before the user is allowed to use it, or it might be doing a calculation before displaying the result to the user. In such cases, it is helpful to display a dialog, known as a progress dialog, so that the user is kept in the loop.

Android provides a ProgressDialog class you can call when you want to display a running meter to the user. ProgressDialog is easy to call from an activity.

The following Try It Out demonstrates how to display such a dialog.

The next section explains using Intents, which help you navigate between multiple Activities.

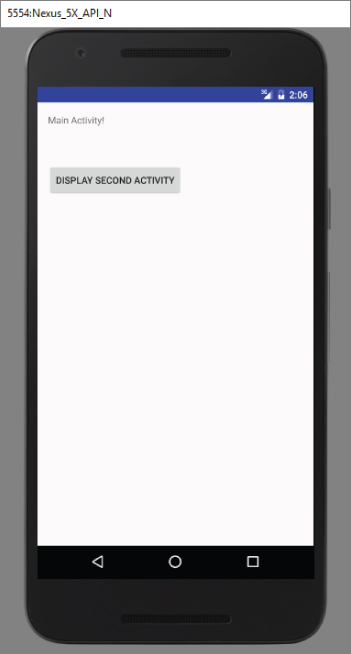

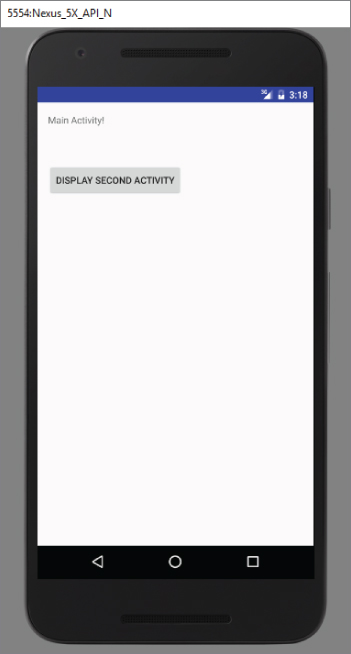

An Android application can contain zero or more activities. When your application has more than one activity, you often need to navigate from one to another. In Android, you navigate between activities through what is known as an intent.

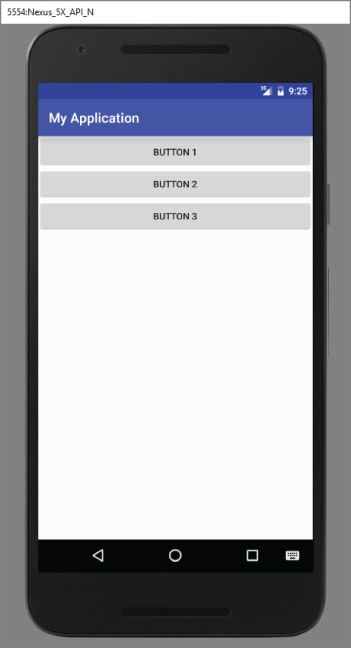

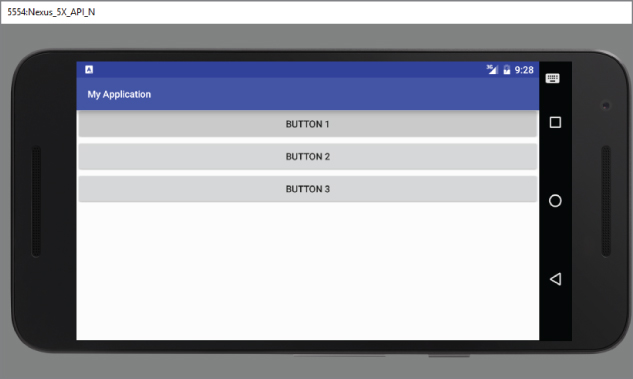

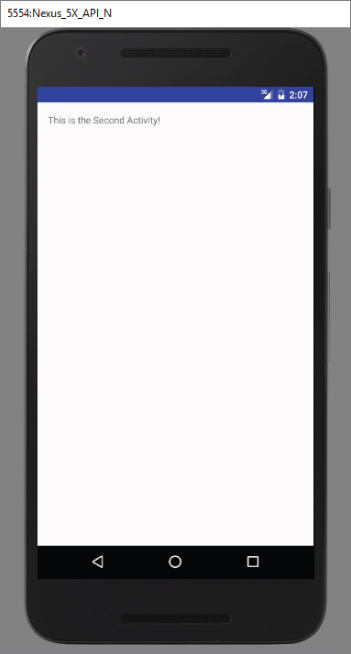

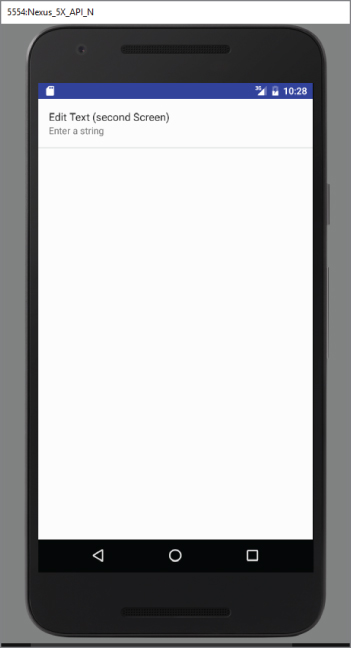

The best way to understand this very important but somewhat abstract concept is to experience it firsthand and see what it helps you achieve. The following Try It Out shows how to add another activity to an existing project and then navigate between the two activities.

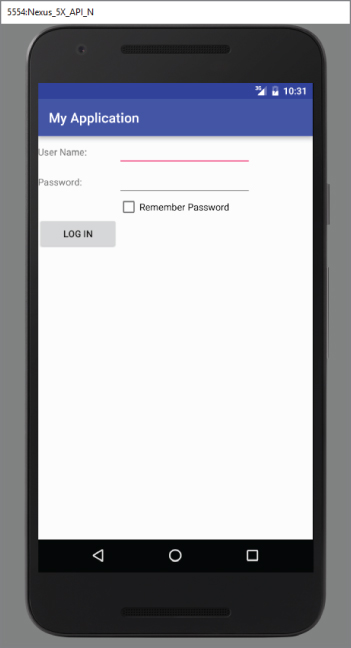

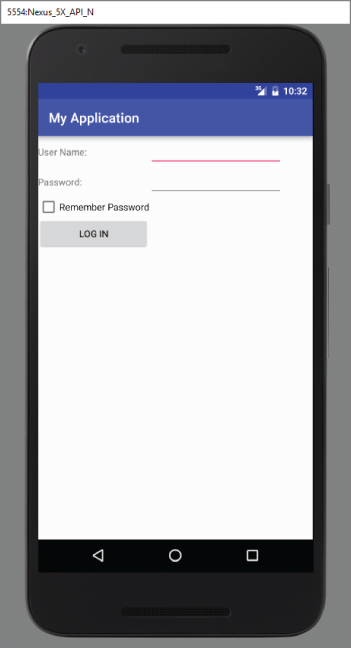

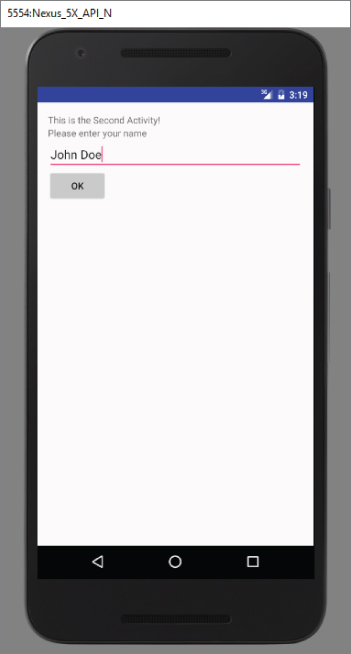

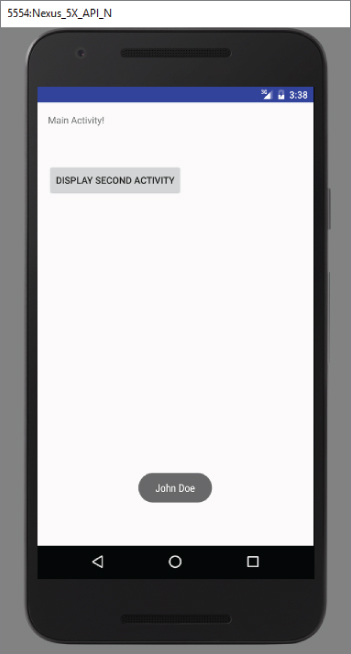

The startActivity() method invokes another activity but does not return a result to the current activity. For example, you might have an activity that prompts the user for username and password. The information entered by the user in that activity needs to be passed back to the calling activity for further processing. If you need to pass data back from an activity, you should instead use the startActivityForResult() method. The following Try It Out demonstrates this.

Besides returning data from an activity, it is also common to pass data to an activity. For example, in the previous example, you might want to set some default text in the EditText view before the activity is displayed. In this case, you can use the Intent object to pass the data to the target activity.

The following Try It Out shows you the various ways in which you can pass data between activities.

activity_main.xml file. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.MainActivity">

<Button

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Click to go to Second Activity"

android:id="@+id/button"

android:onClick="onClick"/>

</LinearLayout>res/layout folder and name it activity_second.xml. Populate it as follows:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.MainActivity">

<TextView

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Welcome to the Second Activity"

android:id="@+id/textView"/>

<Button

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Click to go to Main Activity"

android:id="@+id/button"

android:onClick="onClick"/>

</LinearLayout>Class file to the package and name it SecondActivity. Populate the SecondActivity.java file as follows:package com.jfdimarzio.passingdata;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.net.Uri;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.Toast;

public class SecondActvity extends Activity {

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_second);

//---get the data passed in using getStringExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,getIntent().getStringExtra("str1"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

//---get the data passed in using getIntExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(

getIntent().getIntExtra("age1", 0)),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

//---get the Bundle object passed in---

Bundle bundle = getIntent().getExtras();

//---get the data using the getString()---

Toast.makeText(this, bundle.getString("str2"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

//---get the data using the getInt() method---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(bundle.getInt("age2")),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

public void onClick(View view) {

//---use an Intent object to return data---

Intent i = new Intent();

//---use the putExtra() method to return some

// value---

i.putExtra("age3", 45);

//---use the setData() method to return some value---

i.setData(Uri.parse("Something passed back to main activity"));

//---set the result with OK and the Intent object---

setResult(RESULT_OK, i);

//---destroy the current activity---

finish();

}

}AndroidManifest.xml file:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

package="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata">

<application

android:allowBackup="true"

android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher"

android:label="@string/app_name"

android:supportsRtl="true"

android:theme="@style/AppTheme">

<activity android:name=".MainActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

<activity android:name=".SecondActvity" >

<intent-filter >

<action android:name="com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.SecondActivity" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

</application>

</manifest>MainActivity.java file:package com.jfdimarzio.passingdata;

import android.content.Intent;

import android.Activity;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.Toast;

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_main);

}

public void onClick(View view) {

Intent i = new

Intent("com.jfdimarzio.passingdata.SecondActivity");

//---use putExtra() to add new name/value pairs---

i.putExtra("str1", "This is a string");

i.putExtra("age1", 25);

//---use a Bundle object to add new name/values

// pairs---

Bundle extras = new Bundle();

extras.putString("str2", "This is another string");

extras.putInt("age2", 35);

//---attach the Bundle object to the Intent object---

i.putExtras(extras);

//---start the activity to get a result back---

startActivityForResult(i, 1);

}

public void onActivityResult(int requestCode,

int resultCode, Intent data)

{

//---check if the request code is 1---

if (requestCode == 1) {

//---if the result is OK---

if (resultCode == RESULT_OK) {

//---get the result using getIntExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this, Integer.toString(

data.getIntExtra("age3", 0)),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

//---get the result using getData()---

Toast.makeText(this, data.getData().toString(),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();

}

}

}

}While this application is not visually exciting, it does illustrate some important ways to pass data between activities.

First, you can use the putExtra() method of an Intent object to add a name/value pair:

//---use putExtra() to add new name/value pairs---

i.putExtra("str1", "This is a string");

i.putExtra("age1", 25);The preceding statements add two name/value pairs to the Intent object: one of type string and one of type integer.

Besides using the putExtra() method, you can also create a Bundle object and then attach it using the putExtras() method. Think of a Bundle object as a dictionary object—it contains a set of name/value pairs. The following statements create a Bundle object and then add two name/value pairs to it. The Bundle object is then attached to the Intent object:

//---use a Bundle object to add new name/values pairs---

Bundle extras = new Bundle();

extras.putString("str2", "This is another string");

extras.putInt("age2", 35);

//---attach the Bundle object to the Intent object---

i.putExtras(extras); To obtain the data sent using the Intent object, you first obtain the Intent object using the getIntent() method. Then, call its getStringExtra() method to get the string value set using the putExtra() method:

//---get the data passed in using getStringExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,getIntent().getStringExtra("str1"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();In this case, you have to call the appropriate method to extract the name/value pair based on the type of data set. For the integer value, use the getIntExtra() method (the second argument is the default value in case no value is stored in the specified name):

//---get the data passed in using getIntExtra()---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(

getIntent().getIntExtra("age1", 0)),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show(); To retrieve the Bundle object, use the getExtras() method:

//---get the Bundle object passed in---

Bundle bundle = getIntent().getExtras();To get the individual name/value pairs, use the appropriate method. For the string value, use the getString() method:

//---get the data using the getString()---

Toast.makeText(this, bundle.getString("str2"),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();Likewise, use the getInt() method to retrieve an integer value:

//---get the data using the getInt() method---

Toast.makeText(this,Integer.toString(bundle.getInt("age2")),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();Another way to pass data to an activity is to use the setData() method (as used in the previous section), like this:

//---use the setData() method to return some value---

i.setData(Uri.parse(

"Something passed back to main activity"));Usually, you use the setData() method to set the data on which an Intent object is going to operate, such as passing a URL to an Intent object so that it can invoke a web browser to view a web page. (For more examples, see the section “Calling Built-In Applications Using Intents,” later in this chapter.)

To retrieve the data set using the setData() method, use the getData() method (in this example data is an Intent object):

//---get the result using getData()---

Toast.makeText(this, data.getData().toString(),

Toast.LENGTH_SHORT).show();In the previous section, you learned what an activity is and how to use it. In a small-screen device (such as a smartphone), an activity typically fills the entire screen, displaying the various views that make up the user interface of an application. The activity is essentially a container for views. However, when an activity is displayed in a large-screen device, such as on a tablet, it is somewhat out of place. Because the screen is much bigger, all the views in an activity must be arranged to make full use of the increased space, resulting in complex changes to the view hierarchy. A better approach is to have “mini-activities,” each containing its own set of views. During runtime, an activity can contain one or more of these mini-activities, depending on the screen orientation in which the device is held. In Android 3.0 and later, these mini-activities are known as fragments.

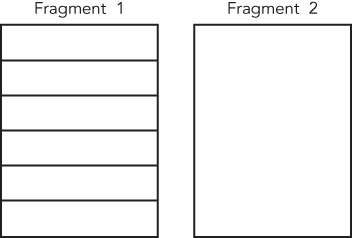

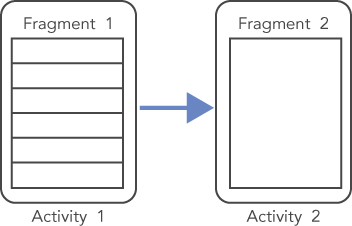

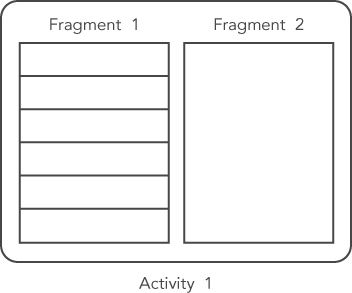

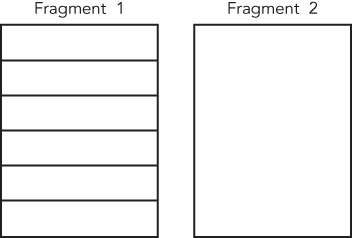

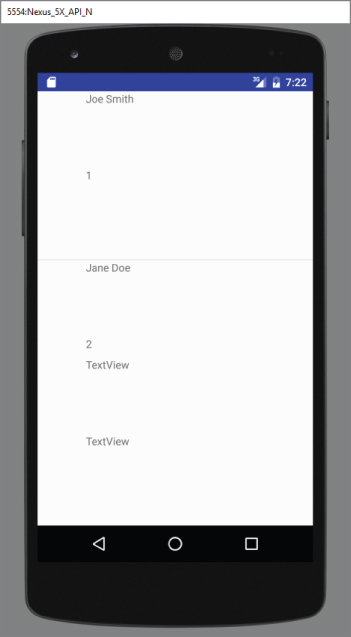

Think of a fragment as another form of activity. You create fragments to contain views, just like activities. Fragments are always embedded in an activity. For example, Figure 3.13 shows two fragments. Fragment 1 might contain a ListView showing a list of book titles. Fragment 2 might contain some TextViews and ImageViews showing some text and images.

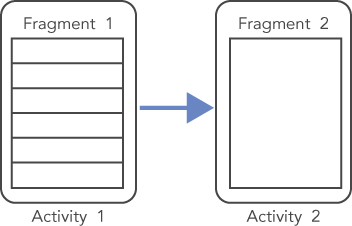

Now imagine the application is running on an Android tablet (or on an Android smartphone) in portrait mode. In this case, Fragment 1 might be embedded in one activity, whereas Fragment 2 might be embedded in another activity (see Figure 3.14). When users select an item in the list in Fragment 1, Activity 2 is started.

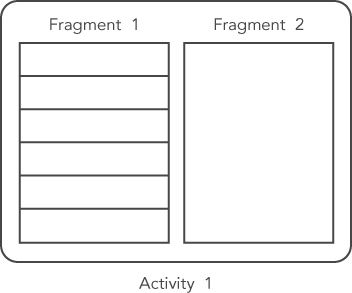

If the application is now displayed in a tablet in landscape mode, both fragments can be embedded within a single activity, as shown in Figure 3.15.

From this discussion, it becomes apparent that fragments present a versatile way in which you can create the user interface of an Android application. Fragments form the atomic unit of your user interface, and they can be dynamically added (or removed) to activities in order to create the best user experience possible for the target device.

The following Try It Out shows you the basics of working with fragments.

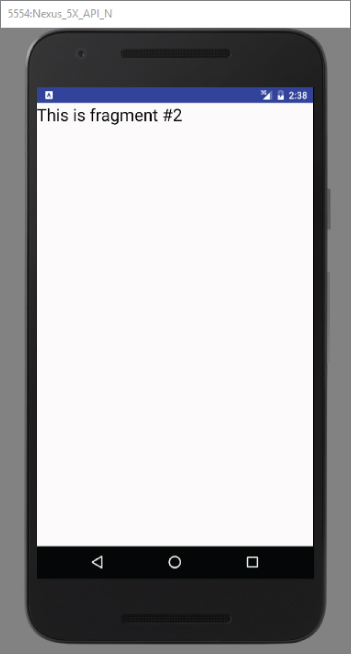

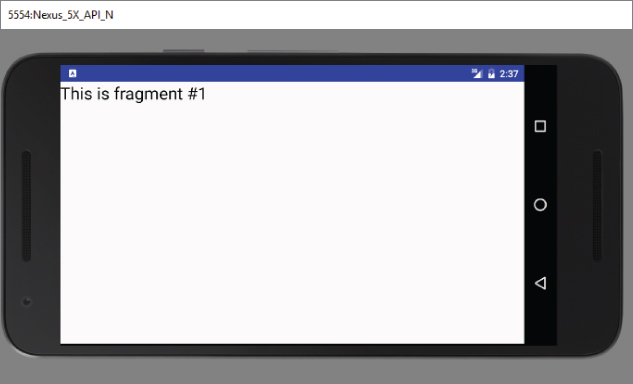

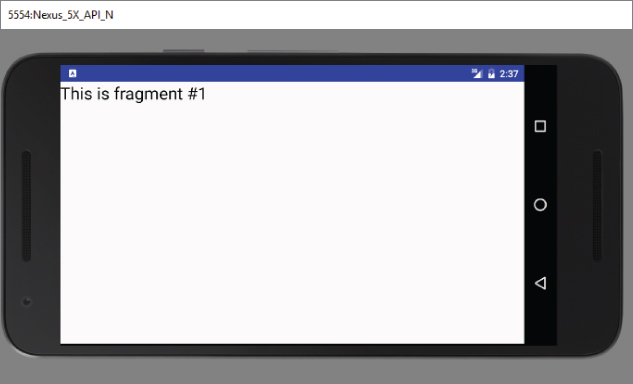

res/layout folder, add a new layout resource file and name it fragment1.xml. Populate it with the following code. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:background="#00FF00"

>

<TextView

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="This is fragment #1"

android:textColor="#000000"

android:textSize="25sp"/>

</LinearLayout>res/layout folder, add another new layout resource file and name it fragment2.xml. Populate it as follows:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:background="#FFFE00"

>

<TextView

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="This is fragment #2"

android:textColor="#000000"

android:textSize="25sp"/>

</LinearLayout>activity_main.xml, add the bolded lines in the following code:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity">

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"

android:id="@+id/fragment1"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent" />

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"

android:id="@+id/fragment2"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent" />

</LinearLayout><Your Package Name>/fragments package name, add two Java class files and name them Fragment1.java and Fragment2.java.Fragment1.java:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

public class Fragment1 extends Fragment {

@Override

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater,

ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {

//---Inflate the layout for this fragment---

return inflater.inflate(

R.layout.fragment1, container, false);

}

}Fragment2.java:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

public class Fragment2 extends Fragment {

@Override

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater,

ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {

//---Inflate the layout for this fragment---

return inflater.inflate(

R.layout.fragment2, container, false);

}

}

A fragment behaves very much like an activity: It has a Java class and it loads its UI from an XML file. The XML file contains all the usual UI elements that you expect from an activity: TextView, EditText, Button, and so on. The Java class for a fragment needs to extend the Fragment base class:

public class Fragment1 extends Fragment {

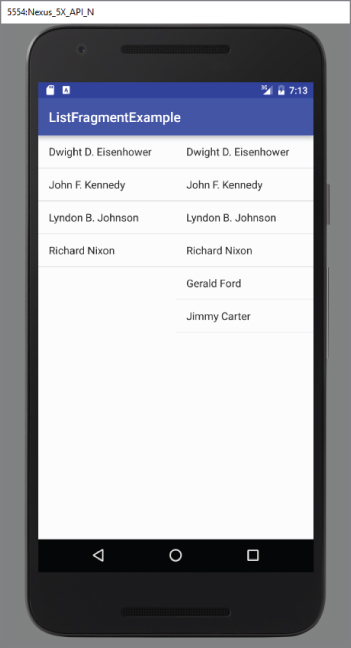

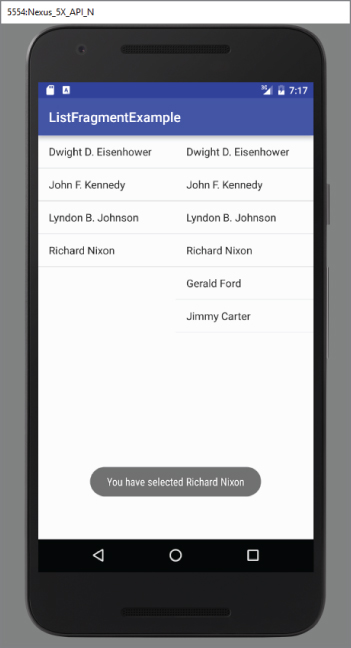

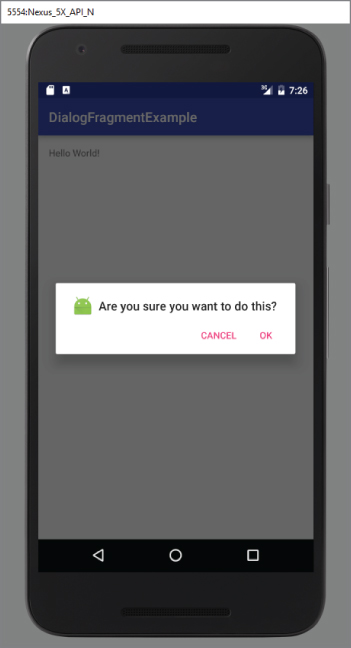

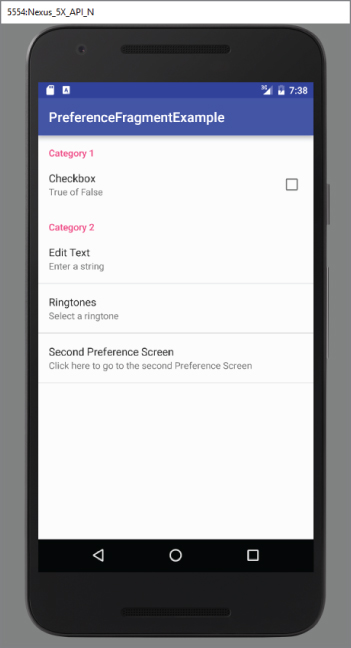

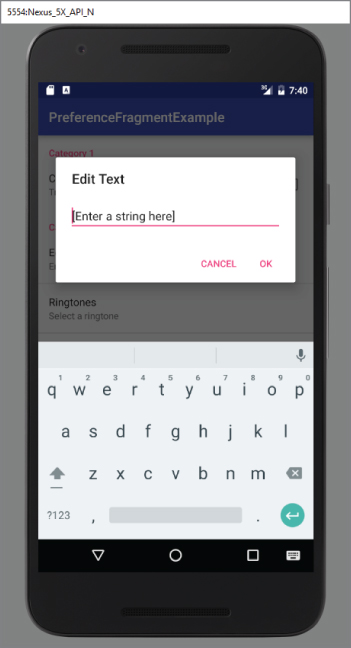

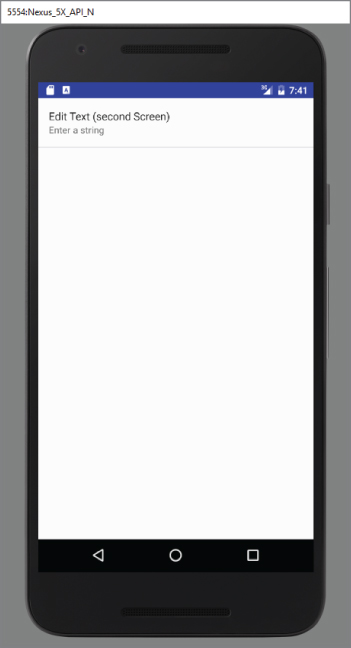

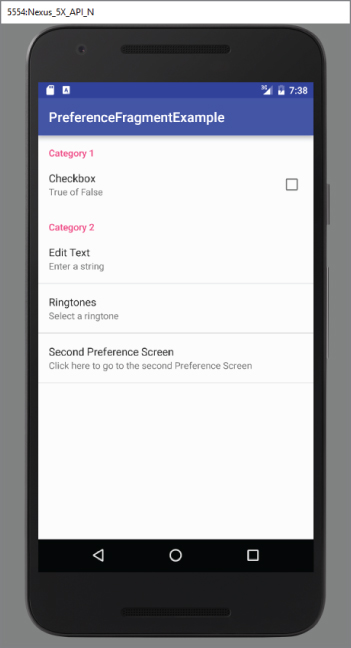

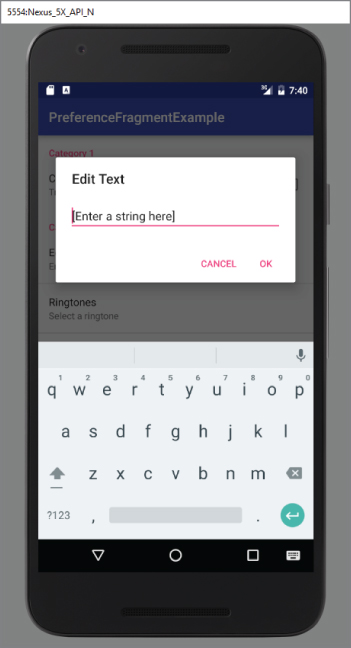

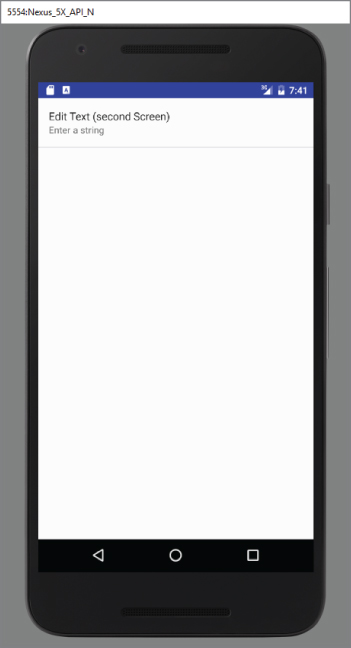

}Besides the Fragment base class, a fragment can also extend a few other subclasses of the Fragment class, such as DialogFragment, ListFragment, and PreferenceFragment. Chapter 6 discusses these types of fragments in more detail.

To draw the UI for a fragment, you override the onCreateView() method. This method needs to return a View object, like this:

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater,

ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {

//---Inflate the layout for this fragment---

return inflater.inflate(

R.layout.fragment1, container, false);

}

Here, you use a LayoutInflater object to inflate the UI from the

specified XML file (R.layout.fragment1 in this case). The

container argument refers to the parent ViewGroup, which

is the activity in which you are trying to embed the

fragment. The savedInstanceState argument enables you

to restore the fragment to its previously saved state.

To add a fragment to an activity, you use the <fragment> element:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res

/android"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:orientation="vertical" >

<fragment

android:name=" com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"

android:id="@+id/fragment1"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

<fragment

android:name=" com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"

android:id="@+id/fragment2"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

</LinearLayout>Note that each fragment needs a unique identifier. You can assign one via the android:id or android:tag attribute.

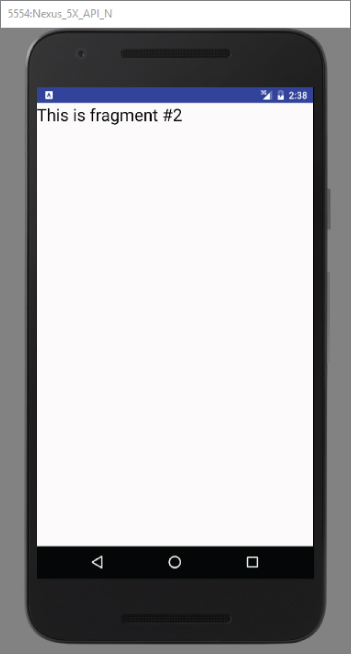

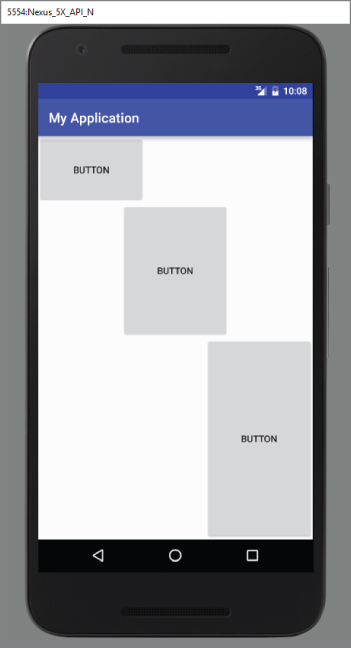

Although fragments enable you to compartmentalize your UI into various configurable parts, the real power of fragments is realized when you add them dynamically to activities during runtime. In the previous section, you saw how you can add fragments to an activity by modifying the XML file during design time. In reality, it is much more useful if you create fragments and add them to activities during runtime. This enables you to create a customizable user interface for your application. For example, if the application is running on a smartphone, you might fill an activity with a single fragment; if the application is running on a tablet, you might then fill the activity with two or more fragments, as the tablet has much more screen real estate compared to a smartphone.

The following Try It Out shows how you can programmatically add fragments to an activity during runtime.

main.xml file by commenting out the two <fragment> elements. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity">

<!--

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"

android:id="@+id/fragment1"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"

android:id="@+id/fragment2"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

-->

</LinearLayout>MainActivity.java file:package com.jfdimarzio.fragments;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.FragmentManager;

import android.app.FragmentTransaction;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.util.DisplayMetrics;

public class MainActivity extends Activity {

/** Called when the activity is first created. */

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager();

FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction =

fragmentManager.beginTransaction();

//---get the current display info---

DisplayMetrics display = this.getResources().getDisplayMetrics();

int width = display.widthPixels;

int height = display.heightPixels;

if (width> height)

{

//---landscape mode---

Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();

// android.R.id.content refers to the content

// view of the activity

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment1);

}

else

{

//---portrait mode---

Fragment2 fragment2 = new Fragment2();

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment2);

}

fragmentTransaction.commit();

}

}

To add fragments to an activity, you use the FragmentManager class by first obtaining an instance of it:

FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager();You also need to use the FragmentTransaction class to perform fragment transactions (such as add, remove, or replace) in your activity:

FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction =

fragmentManager.beginTransaction(); In this example, the WindowManager is used to determine whether the device is currently in portrait mode or landscape mode. Once that is determined, you can add the appropriate fragment to the activity by creating the fragment. Next, you call the replace() method of the FragmentTransaction object to add the fragment to the specified view container. In this case, android.R.id.content refers to the content view of the activity.

//---landscape mode---

Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();

// android.R.id.content refers to the content

// view of the activity

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment1);Using the replace() method is essentially the same as calling the remove() method followed by the add() method of the FragmentTransaction object. To ensure that the changes take effect, you need to call the commit() method:

fragmentTransaction.commit(); Like activities, fragments have their own life cycle. Understanding the life cycle of a fragment enables you to properly save an instance of the fragment when it is destroyed, and restore it to its previous state when it is re-created.

The following Try It Out examines the various states experienced by a fragment.

Fragment1.java file. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.package com.jfdimarzio.fragments;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.Fragment;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.util.Log;

import android.view.LayoutInflater;

import android.view.View;

import android.view.ViewGroup;

public class Fragment1 extends Fragment {

@Override

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater,

ViewGroup container, Bundle savedInstanceState) {

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onCreateView");

//---Inflate the layout for this fragment---

return inflater.inflate(

R.layout.fragment1, container, false);

}

@Override

public void onAttach(Activity activity) {

super.onAttach(activity);

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onAttach");

}

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onCreate");

}

@Override

public void onActivityCreated(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onActivityCreated(savedInstanceState);

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onActivityCreated");

}

@Override

public void onStart() {

super.onStart();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onStart");

}

@Override

public void onResume() {

super.onResume();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onResume");

}

@Override

public void onPause() {

super.onPause();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onPause");

}

@Override

public void onStop() {

super.onStop();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onStop");

}

@Override

public void onDestroyView() {

super.onDestroyView();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDestroyView");

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

super.onDestroy();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDestroy");

}

@Override

public void onDetach() {

super.onDetach();

Log.d("Fragment 1", "onDetach");

}

}12-09 04:17:43.436: D/Fragment 1(2995): onAttach

12-09 04:17:43.466: D/Fragment 1(2995): onCreate

12-09 04:17:43.476: D/Fragment 1(2995): onCreateView

12-09 04:17:43.506: D/Fragment 1(2995): onActivityCreated

12-09 04:17:43.506: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStart

12-09 04:17:43.537: D/Fragment 1(2995): onResume12-09 04:18:47.696: D/Fragment 1(2995): onPause

12-09 04:18:50.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStop12-09 04:20:08.726: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStart

12-09 04:20:08.766: D/Fragment 1(2995): onResume12-09 04:21:01.426: D/Fragment 1(2995): onPause

12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onStop

12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDestroyView

12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDestroy

12-09 04:21:02.346: D/Fragment 1(2995): onDetachLike activities, fragments in Android also have their own life cycle. As you have seen, when a fragment is being created, it goes through the following states:

onAttach()onCreate()onCreateView()onActivityCreated()When the fragment becomes visible, it goes through these states:

onStart()onResume()When the fragment goes into the background mode, it goes through these states:

onPause()onStop()When the fragment is destroyed (when the activity in which it is currently hosted is destroyed), it goes through the following states:

onPause()onStop()onDestroyView()onDestroy()onDetach()Like activities, you can restore an instance of a fragment using a Bundle object, in the following states:

onCreate()onCreateView()onActivityCreated()Most of the states experienced by a fragment are similar to those of activities. However, a few new states are specific to fragments:

onAttached()—Called when the fragment has been associated with the activityonCreateView() Called to create the view for the fragmentonActivityCreated()—Called when the activity's onCreate() method has been returnedonDestroyView()—Called when the fragment's view is being removedonDetach()—Called when the fragment is detached from the activityOne of the main differences between activities and fragments is when an activity goes into the background, the activity is placed in the back stack. This allows the activity to be resumed when the user presses the Back button. In the case of fragments, however, they are not automatically placed in the back stack when they go into the background. Rather, to place a fragment into the back stack, you need to explicitly call the addToBackStack() method during a fragment transaction, like this:

//---get the current display info---

DisplayMetrics display = this.getResources().getDisplayMetrics();

int width = display.widthPixels;

int height = display.heightPixels;

if (width> height)

{

//---landscape mode---

Fragment1 fragment1 = new Fragment1();

// android.R.id.content refers to the content

// view of the activity

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment1);

}

else

{

//---portrait mode---

Fragment2 fragment2 = new Fragment2();

fragmentTransaction.replace(

android.R.id.content, fragment2);

}

//---add to the back stack---

fragmentTransaction.addToBackStack(null);

fragmentTransaction.commit(); The preceding code ensures that after the fragment has been added to the activity, the user can click the Back button to remove it.

Very often, an activity might contain one or more fragments working together to present a coherent UI to the user. In this case, it is important for fragments to communicate with one another and exchange data. For example, one fragment might contain a list of items (such as postings from an RSS feed). Also, when the user taps on an item in that fragment, details about the selected item might be displayed in another fragment.

The following Try It Out shows how one fragment can access the views contained within another fragment.

Fragment1.xml file. Be sure to change all instances of "com.jfdimarzio" to whatever package name your project is using.<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:background="#00FF00" >

<TextView

android:id="@+id/lblFragment1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="This is fragment #1"

android:textColor="#000000"

android:textSize="25sp"/>

</LinearLayout>fragment2.xml:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:orientation="vertical"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="fill_parent"

android:background="#FFFE00" >

<TextView

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="This is fragment #2"

android:textColor="#000000"

android:textSize="25sp"/>

<Button

android:id="@+id/btnGetText"

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Get text in Fragment #1"

android:textColor="#000000"

android:onClick="onClick" />

</LinearLayout>main.xml:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout android:orientation="vertical"

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:paddingBottom="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

android:paddingLeft="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingRight="@dimen/activity_horizontal_margin"

android:paddingTop="@dimen/activity_vertical_margin"

tools:context="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.MainActivity">

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment1"

android:id="@+id/fragment1"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

<fragment

android:name="com.jfdimarzio.fragments.Fragment2"

android:id="@+id/fragment2"

android:layout_weight="1"

android:layout_width="fill_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"/>

</LinearLayout>MainActivity.java file by commenting out the code that you added in the earlier sections. It should look like this after modification:public class MainActivity extends Activity {

/** Called when the activity is first created. */

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

/*

FragmentManager fragmentManager = getFragmentManager();

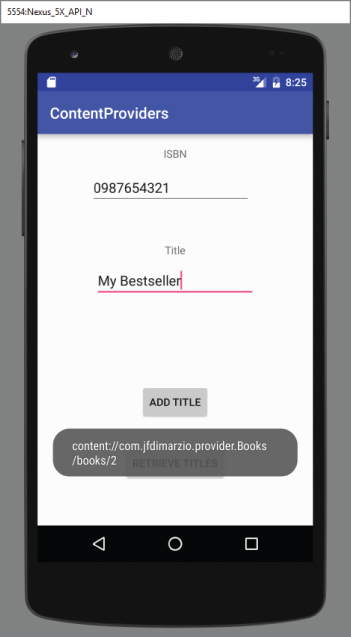

FragmentTransaction fragmentTransaction =