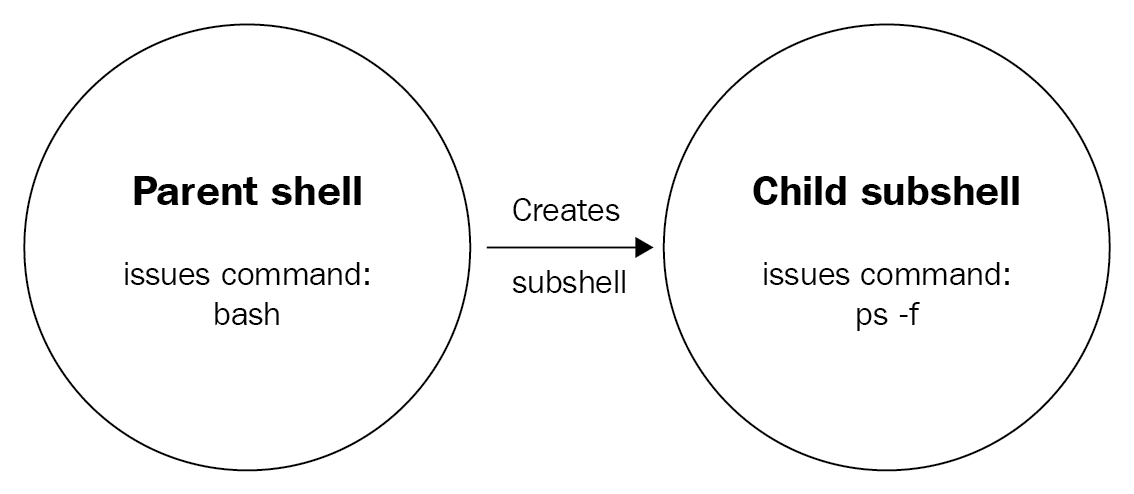

The exit status, commonly also referred to as exit codes or return codes, is the way Bash communicates the successful or unsuccessful termination of a process to its parent. In Bash, all processes are forked from the shell that calls them. The following diagram illustrates this:

When a command runs, such as ps -f in the preceding diagram, the current shell is copied (including the environment variables!), and the command runs in the copy, called the fork. After the command/process is done, it terminates the fork and returns the exit status to the shell that it was initially forked from (which, in the case of an interactive session, will be your user session). At that point, you can determine whether the process was executed successfully by looking at the exit code. As explained in the previous chapter, an exit code of 0 is considered OK, while all other codes should be treated as NOT OK. Because the fork is terminated, we need the return code, otherwise we will have no way of communicating the status back to our session!

Because we have already seen how to grab the exit status in an interactive session in the previous chapter (hint: we looked at the content of the $? variable!), let's see how we can do the same in a script:

reader@ubuntu:~/scripts/chapter_09$ vim return-code.sh

reader@ubuntu:~/scripts/chapter_09$ cat return-code.sh

#!/bin/bash

#####################################

# Author: Sebastiaan Tammer

# Version: v1.0.0

# Date: 2018-09-29

# Description: Teaches us how to grab a return code.

# Usage: ./return-code.sh

#####################################

# Run a command that should always work:

mktemp

mktemp_rc=$?

# Run a command that should always fail:

mkdir /home/

mkdir_rc=$?

echo "mktemp returned ${mktemp_rc}, while mkdir returned ${mkdir_rc}!"

reader@ubuntu:~/scripts/chapter_09$ bash return-code.sh

/tmp/tmp.DbxKK1s4aV

mkdir: cannot create directory ‘/home’: File exists

mktemp returned 0, while mkdir returned 1!

Going through the script, we start with the shebang and header. Since we don't use user input in this script, the usage is just the script name. The first command we run is mktemp. This command is used to create a temporary file with a random name, which could be useful is we needed to have a place on disk for some temporary data. Alternatively, if we supplied the -d flag to mktemp, we would create a temporary directory with a random name. Because the random name is sufficiently long and we should always have write permissions in /tmp/, we would expect the mktemp command to almost always succeed and thus return an exit status of 0. We save the return code to the mktemp_rc variable by running the variable assignment directly after the command. In that lies the biggest weakness with return codes: we only have them available directly after the command completes. If we do anything else after, the return code will be set for that action, overwriting the previous exit status!

Next, we run a command which we expect to always fail: mkdir /home/. The reason we expect this to fail is because on our system (and on pretty much every Linux system), the /home/ directory already exists. In this case, it cannot be created again, which is why the command fails with an exit status of 1. Again, directly after the mkdir command, we save the exit status into the mkdir_rc variable.

Finally, we need to check to see whether our assumptions are correct. Using echo, we print the values of both variables along with some text so that we know where we printed which value. One last thing to note here: we used double quotes for our sentence containing variables. If we used single quotes, the variables would not be expanded (the Bash term for substituting the variable name with its value). Alternatively, we could omit the quotes altogether, and echo would perform as desired as well, however that could start presenting issues when we start working with redirection, which is why we consider it good form to always use double quotes when dealing with strings containing variables.