Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Vijin Boricha

Acquisition Editor: Rohit Rajkumar

Content Development Editor: Abhishek Jadhav

Technical Editor: Prachi Sawant

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Jagdish Prabhu

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Priyanka Dhadke

Graphics: Tom Scaria

Production Coordinator: Tom Scaria

First published: December 2018

Production reference: 1281218

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78899-559-7

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Sebastiaan Tammer is a Linux enthusiast from the Netherlands. After attaining his BSc in information sciences, he graduated with an MSc in business informatics, both from Utrecht University. His professional career started in Java development, before he pivoted into a Linux opportunity. Because of this dual background, he feels most at home in a DevOps environment.

Besides working extensively with technologies such as Puppet, Chef, Docker, and Kubernetes, he has also attained the RHCE and OSCP certificates. He spends a lot of time in and around Bash. Whether it is creating complex scripting solutions or just automating simple tasks, there is hardly anything he hasn't done with Bash!

Heathe Kyle Yeakley holds degrees in technical communications and network management. He began his IT career in 1999 doing entry-level help desk support. In 2003, he began his first enterprise data center job performing tape backup and recovery for the United States Federal Aviation Administration. He worked in the aerospace sector for several years, during which time he worked on a wide range of products, including HP Tru64 Unix, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Solaris 10, Legato Networker, Symantec NetBackup, HP and NetApp storage arrays, Spectra Logic and ADIC tape libraries, VMware, and HP Blade servers.

He currently works for Agio, where he and his coworkers deliver managed IT services to some of the world's most prestigious companies.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Shell scripts allow us to program commands in chains and have the system execute them as a scripted event, just like batch files. This book will start with an overview of Linux and Bash shell scripting, and then quickly deep dive into helping you set up your local environment, before introducing you to tools that are used to write shell scripts. The next set of chapters will focus on helping you understand Linux under the hood and what Bash provides the user. Soon, you will have embarked on your journey along the command line. You will now begin writing actual scripts instead of commands, and will be introduced to practical applications for scripts. The final set of chapters will deep dive into the more advanced topics in shell scripting. These advanced topics will take you from simple scripts to reusable, valuable programs that exist in the real world. The final chapter will leave you with some handy tips and tricks and, as regards the most frequently used commands, a cheat sheet containing the most interesting flags and options will also be provided.

After completing this book, you should feel confident about starting your own shell scripting projects, no matter how simple or complex the task previously seemed. We aim to teach you how to script and what to consider, to complement the clear-cut patterns that you can use in your daily scripting challenges.

This book targets new and existing Linux system administrators, as well as Windows system administrators or developers who are interested in automating administrative tasks. No prior shell scripting experience is required, but if you do possess some experience, this book will quickly turn you into a pro. Readers should have a (very) basic understanding of the command line.

Chapter 1, Introduction, primes you for the remainder of the book. Aided by some background in Linux and Bash, you should be better able to understand how and why shell scripting can provide clear benefits to you.

Chapter 2, Setting Up Your Local Environment, helps you to prepare your local machine for the examples and exercises throughout the rest of the book. You will be shown how to set up an Ubuntu 18.04 Linux virtual machine on your local machine, using VirtualBox. This virtual machine will be used to write, run, and debug commands and scripts in this book.

Chapter 3, Choosing the Right Tools, introduces you to the tools that will be used to write shell scripts. Two different kinds of tools will be described: IDE editors (Atom, Notepad++), and terminal-based editors (vim and nano). You will be encouraged to initially write scripts in an IDE, and troubleshoot scripts in a terminal-based editor, to most resemble real-world use.

Chapter 4, The Linux Filesystem, coves how the Linux filesystem is organized by exploring the virtual machine created in the previous chapters. You will achieve this by performing your first command-line actions, such as cd, pwd, and ls. Context regarding the different structures will be provided so that you can use this information when writing scripts. And, most importantly, the concept of everything is a file will be explained.

Chapter 5, Understanding the Linux Permissions Scheme, gets you acquainted with permissions under Linux, once again by exploring the virtual machine. Commands such as sudo, chmod, and chown will be used to interactively learn about file and directory privileges. The skills acquired in this chapter will be heavily used in shell scripting, so it is imperative that you gain exposure to both the successful execution of commands as well as failure messages.

Chapter 6, File Manipulation, introduces you to the most relevant file manipulation commands, including the most commonly used flags and modifiers for those commands. This will be achieved by means of commands inside the virtual machine.

Chapter 7, Hello World!, educates you in terms of thinking ahead and developing good habits when it comes to writing scripts. You will write your first actual shell script during this chapter.

Chapter 8, Variables and User Input, introduces you to variables and user input. You will see how parameters are used by Bash, and where the differences lie between parameters and arguments. User input will be handled and used to produce new functions in your scripts. Finally, the difference between interactive and non-interactive scripts will be clarified and discussed.

Chapter 9, Error Checking and Handling, gets you familiar with (user) input, and error checking and handling. Introducing user input into a script is bound to result in more errors, unless the script specifically deals with the possibility of users submitting incorrect or unexpected input. You will learn how to best deal with this.

Chapter 10, Regular Expressions, gets you familiar with regular expressions, which are often used in shell scripting. The most common patterns and uses for these regular expressions will be presented. Basic usage of sed will be covered in this chapter, complementing regular expression explanations.

Chapter 11, Conditional Testing and Scripting Loops, discusses the different kind of loops and the relevant control structures that are used in shell scripting with Bash.

Chapter 12, Using Pipes and Redirection in Scripts, introduces you to redirection on Linux. This chapter will start with the basic input/output redirection, before continuing to stream redirection and pipes.

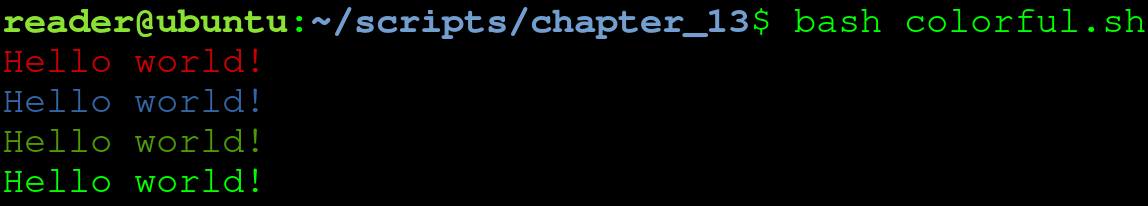

Chapter 13, Functions, introduces you to functions. Functions will be presented as blocks of code that are grouped together in such a way that they can be reused, often with different arguments, to produce a slightly different end result. You will learn to understand the benefit to reusing code, and planning scripts accordingly.

Chapter 14, Scheduling and Logging, teaches you how to schedule scripts and how to make sure these scheduled scripts perform the task they were intended for, by using the crontab and the at command, coupled with proper logging.

Chapter 15, Parsing Bash Script Arguments with getopts, helps you to improve your scripts by adding flags instead of positional parameters, thereby making the scripts much easier to use.

Chapter 16, Bash Parameter Substitution and Expansion, shows how previous patterns used in earlier scripts can be optimized by means of parameter expansion, substitution, and variable manipulation.

Chapter 17, Tips and Tricks with Cheat Sheet, provides you with some handy tips and tricks that are not necessarily used in Bash scripts, but that are very convenient when working on the terminal. For the most frequently used commands, a cheat sheet containing the most interesting flags and options will be provided so that you can use this chapter as reference while scripting.

You will require an Ubuntu 18.04 Linux virtual machine to follow along with the book. We will guide you through setting this up during in the second chapter. You will only truly learn shell scripting if you follow along with all code examples. The entire book has been written with this in mind, so be sure to follow this advice!

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Learn-Linux-Shell-Scripting-Fundamentals-of-Bash-4.4. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/9781788995597_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Let's try to copy the /tmp/ directory into our home directory."

A block of code is set as follows:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello World!"

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

reader@ubuntu:~/scripts/chapter_10$ grep 'use' grep-file.txt

We can use this regular file for testing grep.

but in the USA they use color (and realize)!

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

reader@ubuntu:~/scripts/chapter_10$ grep 'e.e' character-class.txt

eee

e2e

e e

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see on screen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Click the Install button and watch the installation."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in, and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

The information within this book is intended to be used only in an ethical manner. Do not use any information from the book if you do not have written permission from the owner of the equipment. If you perform illegal actions, you are likely to be arrested and prosecuted to the full extent of the law. Packt Publishing does not take any responsibility if you misuse any of the information contained within the book. The information herein must only be used while testing environments with proper written authorizations from appropriate persons responsible.

Before we start writing shell scripts, we need to have some context about our two most relevant components: Linux and Bash. We'll give an explanation of Linux and Bash, look into the history behind the two technologies, and discuss the current state of both.

The following topics will be covered in this chapter:

Linux is a generic term that refers to different open source operating systems that are based on the Linux kernel. The Linux kernel was originally created by Linus Torvalds in 1991, and open sourced in 1996. A kernel is a piece of software that is designed to act as an intermediate layer between low-level hardware (such as the processor, memory, and input/output devices) and high-level software, such as an operating system. Apart from the Linux kernel, most Linux operating systems rely heavily on GNU project utilities; for example, the Bash shell is a GNU program. Because of this, Linux operating systems are referred to by some as GNU/Linux. The GNU project, where GNU stands for GNU's Not Unix! (a recursive acronym), is a collection of free software, a lot of which is found in most Linux distributions. This collection includes many tools, but also an alternative kernel called GNU HURD (which is not as widespread as the Linux kernel).

Why do we need a kernel? Since a kernel sits between hardware and the operating system, it provides an abstraction for interacting with hardware. This is why the Linux ecosystem has grown so large: the kernel can be used freely, and it handles a lot of low-level operations on many types of hardware. Creators of an operating system can therefore spend their time making an easy-to-use, beautiful experience for their users, instead of having to worry about how the users' pictures are going to be written to the physical disk(s) attached to the system.

The Linux kernel is so-called Unix-like software. As you might suspect, this implies that it is similar to the original Unix kernel, which was created between 1971 and 1973 at Bell Labs, by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. However, the Linux kernel is only based on Unix principles and does not share code with Unix systems. Famous Unix systems include the BSDs (FreeBSD, OpenBSD, and so on) and macOS.

Linux operating systems are broadly used for one of two purposes: as a desktop or as a server. As a desktop, Linux can serve as a replacement for the more commonly used Microsoft Windows or macOS. However, most Linux usage is accounted for the server landscape. At the time of writing, it is estimated that around 70% of all servers on the internet use a Unix or Unix-like operating system. The next time you're browsing the news, reading your mail, or are scrolling through your favorite social media website, remember that there's a big chance the pages you are being shown have been processed by one or more Linux servers.

There are many distributions, or flavors, of Linux. Most Linux operating systems fall within distribution families. A distribution family is based on a common ancestor, and often use the same package management tools. One of the more well-known Linux distributions, Ubuntu, is based on the Debian distribution family. Another prominent Linux distribution, Fedora, is based on the Red Hat family. Other notable distribution families include SUSE, Gentoo, and Arch.

Not many people realize how many devices run the Linux kernel. For example, the most common smartphone operating system in use today, Android (with a market share of around 85%), uses a modified version of the Linux kernel. The same goes for many smart TVs, routers, modems, and various other (embedded) devices. If we were to include Unix and other Unix-like software, we can safely say that most of the devices in the world run on these kernels!

The most commonly used shell in Linux systems is the Bourne-again shell, or Bash. The Bash shell is based on the Bourne shell, known as sh. But what is a shell?

A shell is, in essence, a user interface. Most often, it is used to refer to a text-based interface, also called a command-line interface (CLI). However, it is called a shell because it can be seen as a shell around the kernel; this means that it applies not just to CLIs, but just as well to graphical user interfaces (GUIs). When we refer to a shell in this book, we are talking about a CLI, and unless stating differently, we're talking about the Bash shell.

The purpose of a shell, both CLI and GUI, is to allow the user to interact with the system. After all, a system that does not offer interaction would be hard to justify, not too mention hard to use! Interaction in this context means many things: typing on your keyboard will make letters appear on your screen, moving your mouse will change the location of the cursor on screen, giving the command to delete a file (either with a CLI or GUI) will remove the bytes from the disk, and so on.

In the earliest days of Unix and computers, no GUIs were available, so all work was performed via a CLI. To connect to the shell on a running machine, a video terminal was used: often this would be a very simple monitor combined with a keyboard, which was connected with, for example, a RS-232 serial cable. Commands entered on this video terminal were processed by the shell running on the Unix machine.

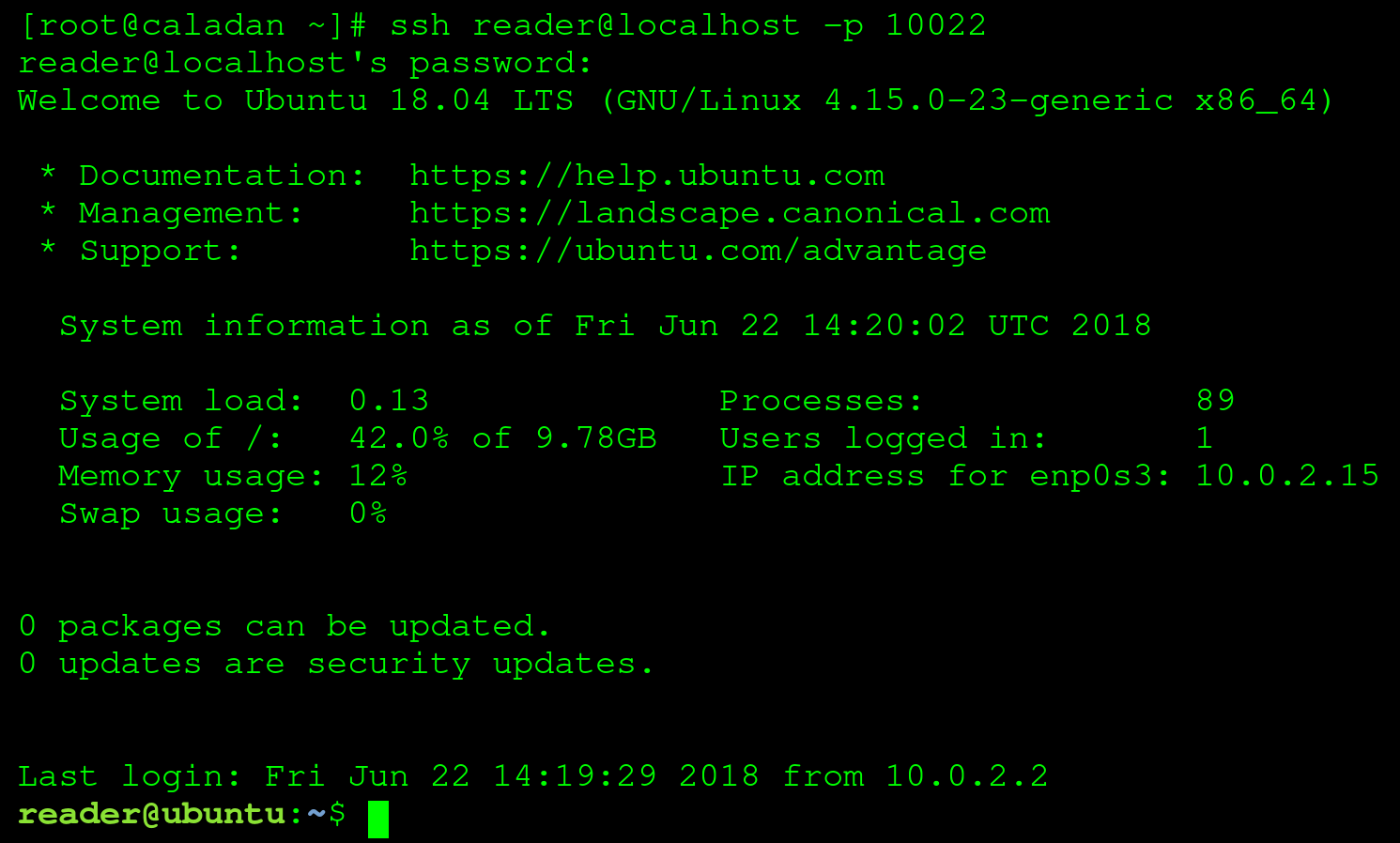

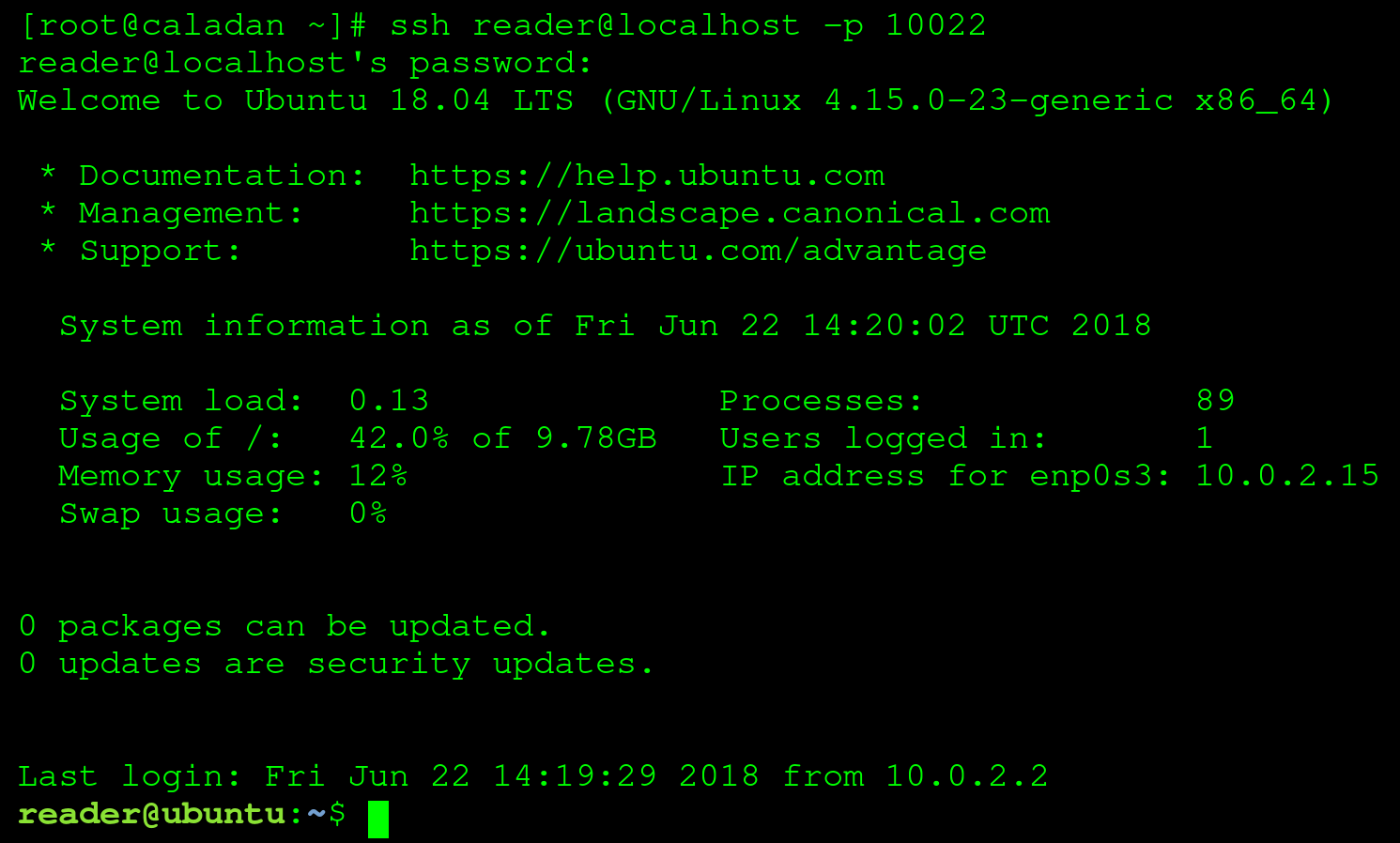

Luckily for us, things have changed quite a bit since the first computers. Today, we no longer use dedicated hardware to connect to shells. A piece of software running in a GUI, a terminal emulator, is used for interaction with the shell. Lets take a quick look at how connecting to a Bash shell with a terminal emulator can look:

In the preceding screenshot, we're connected to a Linux virtual machine (we'll be setting this up in the next chapter), using a terminal emulator (GNOME Terminal) via the Secure Shell (SSH) protocol. A few interesting things to note:

Besides using the Bash shell for direct system interaction, it provides another important functionality: the ability to execute multiple commands sequentially, with or without user interaction, tailored to a specific goal. This might sound complicated, but it's actually pretty simple: we're talking about Bash scripts, the subject of this book!

In this chapter, you've read about the GNU/Linux operating systems and the Linux kernel, what a kernel really is, and how big an impact Linux distributions have on daily life. You've also learned what a shell is, and that the most common Linux shell, Bash, can be both used to interact with a Linux system, and is also utilized to write shell scripts.

In the next chapter, we'll set up a local environment which we will use throughout the rest of the book, in both the examples and exercises.

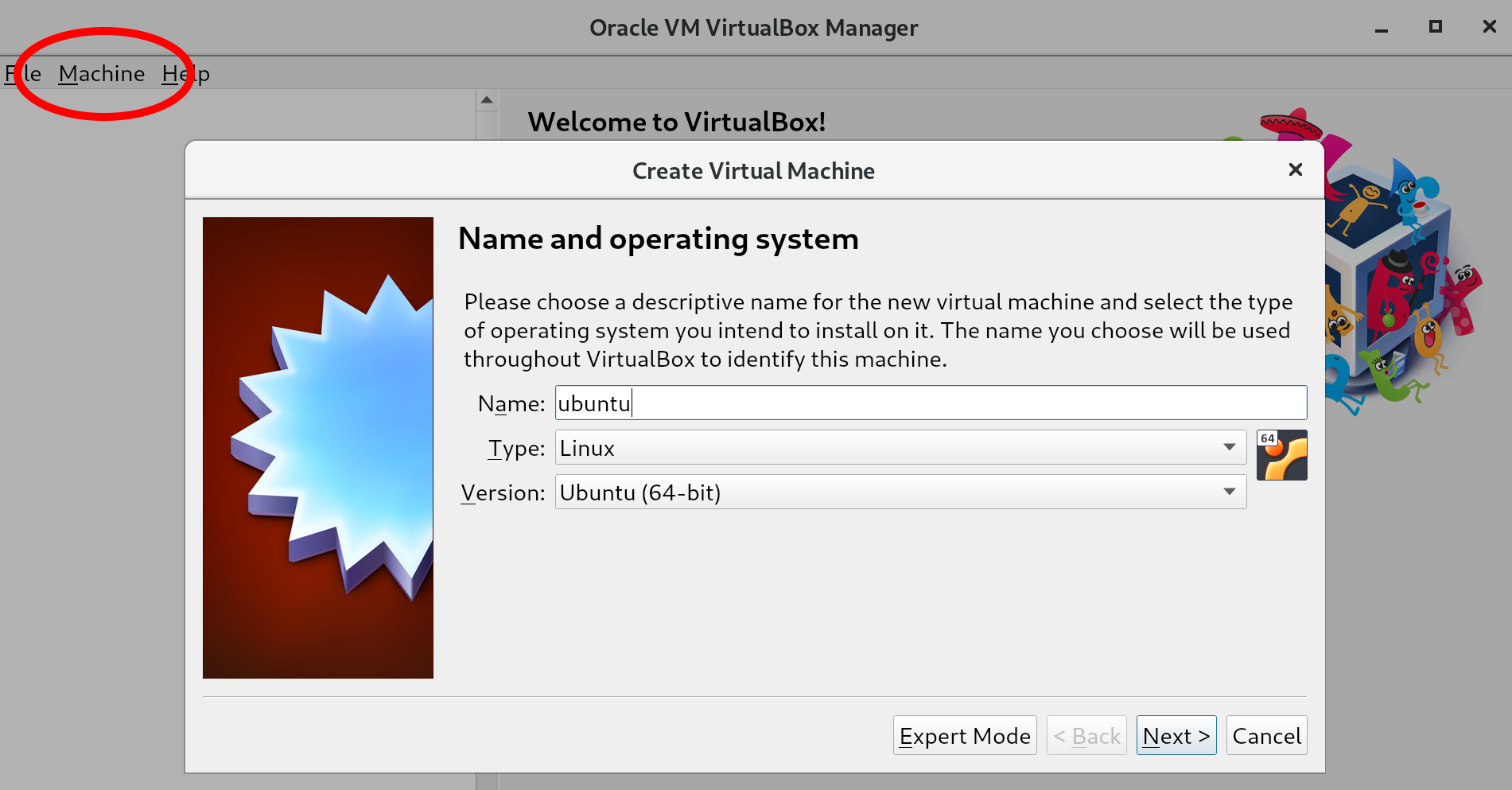

In the previous chapter, we ventured into some context for the wonderful world of Linux and Bash. Since this is a practical, exercise-driven book, we're going to use this chapter to set up a machine where you can follow along with the examples and perform the exercises at the end of each chapter. This can either be a virtual machine or a physical installation; that is up to you. We will discuss this in the first part of this chapter, before continuing with the installation of VirtualBox and, finally, creating an Ubuntu virtual machine.

The following command will be introduced in this chapter: ssh and exit.

The following topics will be covered in this chapter:

To complete the exercises in this chapter (and the following chapters), you will need either a PC or laptop with at least 2 GHz of CPU power, 10 GB of hard disk space, and about 1 GB of RAM to spare. Pretty much all hardware created in the last 5 years should suffice.

A virtual machine is an emulation of a physical machine. This means it runs inside a physical machine, as opposed to directly on the hardware. A physical machine has direct access to all hardware, such as the CPU, the RAM, and other devices such as the mouse, the keyboard, and the monitor. It is, however, impossible to share the CPU or the RAM between multiple physical machines. Virtual machines do not directly get access to hardware, but through an emulation layer, which means resources can be shared between multiple virtual machines.

Because we're discussing Bash shell scripting in general, in theory it does not matter what kind of an installation is performed. As long as that installation runs a compatible Linux operating system with Bash 4.4 or later, all exercises should work. There are, however, many advantages to using a virtual machine over a physical installation:

Unfortunately, there are also drawbacks associated with virtual machine use:

In our opinion, modern computers are fast enough to make the drawbacks almost trivial, while the advantages provided by running Linux in a virtual machine are very helpful. Because of this, we will only be explaining a virtual machine setup in the rest of this chapter. If you feel confident enough to run Linux as a physical installation (or perhaps you already have Linux running somewhere!), feel free to explore the rest of the book with that machine.

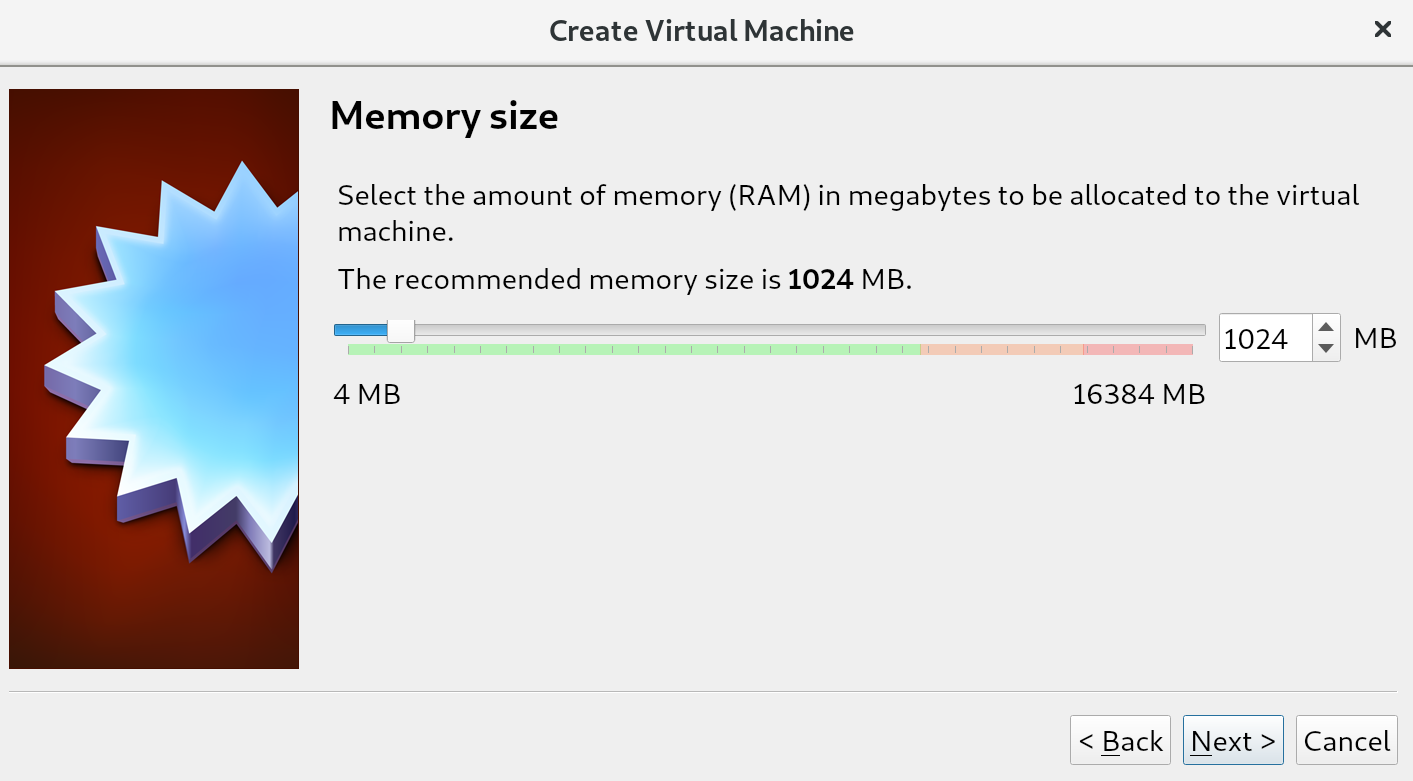

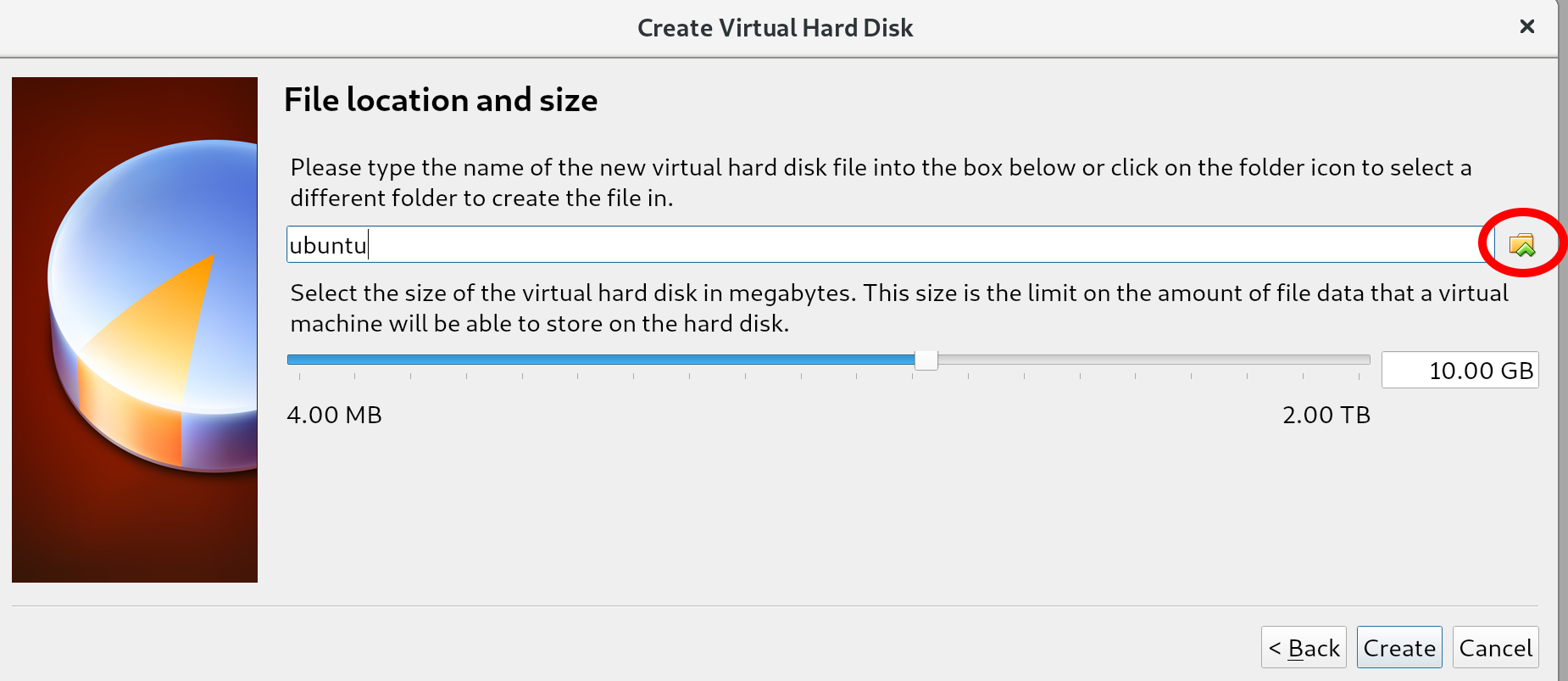

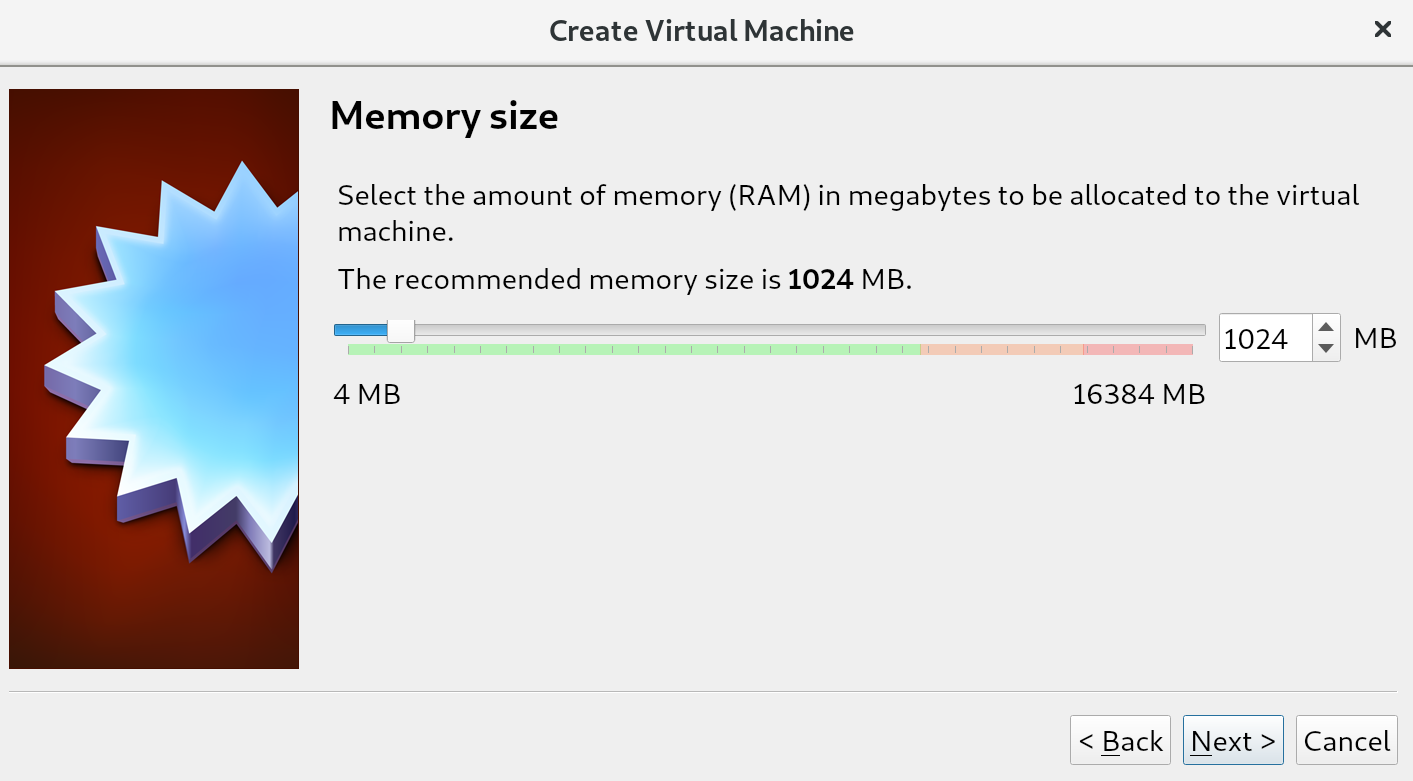

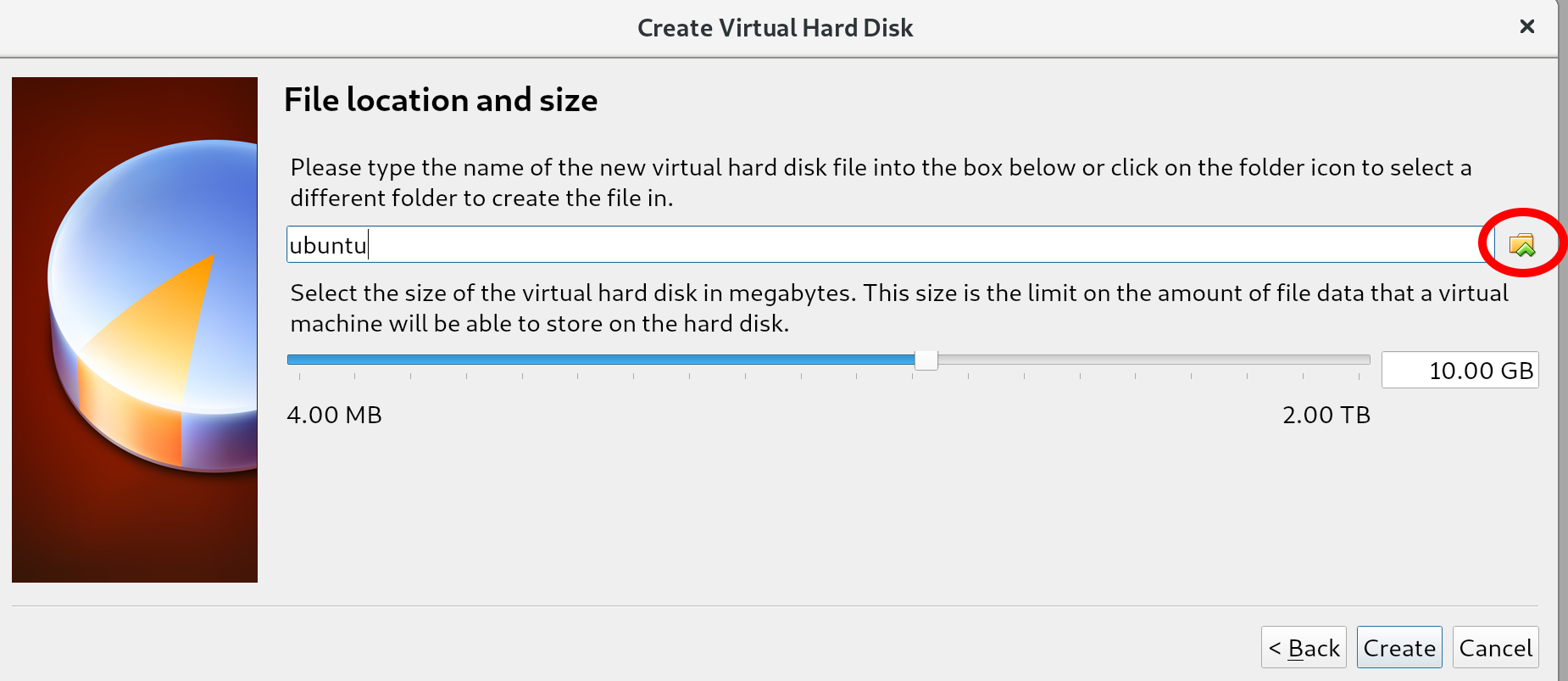

If you want to be sure all examples and exercises work as seen in this book, run an Ubuntu 18.04 LTS virtual machine in VirtualBox with the recommended specifications of 1 CPU, 1 GB RAM, and a 10 GB hard disk: this setup is described in the rest of this chapter. Even if many other types of deployment should work, you would not want to be banging your head against the wall for hours when an exercise is not working, before discovering it was caused by your setup.

To use virtual machines, we need software called a hypervisor. A hypervisor manages resources between the host machine and the virtual machines, provides access to disks, and has an interface to manage it all. There are two different types of hypervisors: type-1 and type-2. Type-1 hypervisors are the so-called bare-metal hypervisors. These are installed instead of a regular operating system such as Linux, macOS, or Windows, directly on the hardware. These types of hypervisors are used for corporate servers, cloud services, and so on. For this book, we will use a type-2 hypervisor (also called hosted hypervisors): these are installed within another operating system, as a piece of software not much different than, for example, a browser.

There are many type-2 hypervisors. The most popular choices at the time of writing are VirtualBox, VMware workstation player, or OS-specific variants such as QEMU/KVM on Linux, Parallels Desktop on macOS, and Hyper-V on Windows. Because we are going to use a virtual machine throughout this book, we do not assume anything about the host machine: you should work comfortably with whatever operating system you prefer. Because of this, we've chosen to use VirtualBox as our hypervisor, since it runs on Linux, macOS, and Windows (and even others!). Furthermore, VirtualBox is free and open source software, which means you can just download and use it.

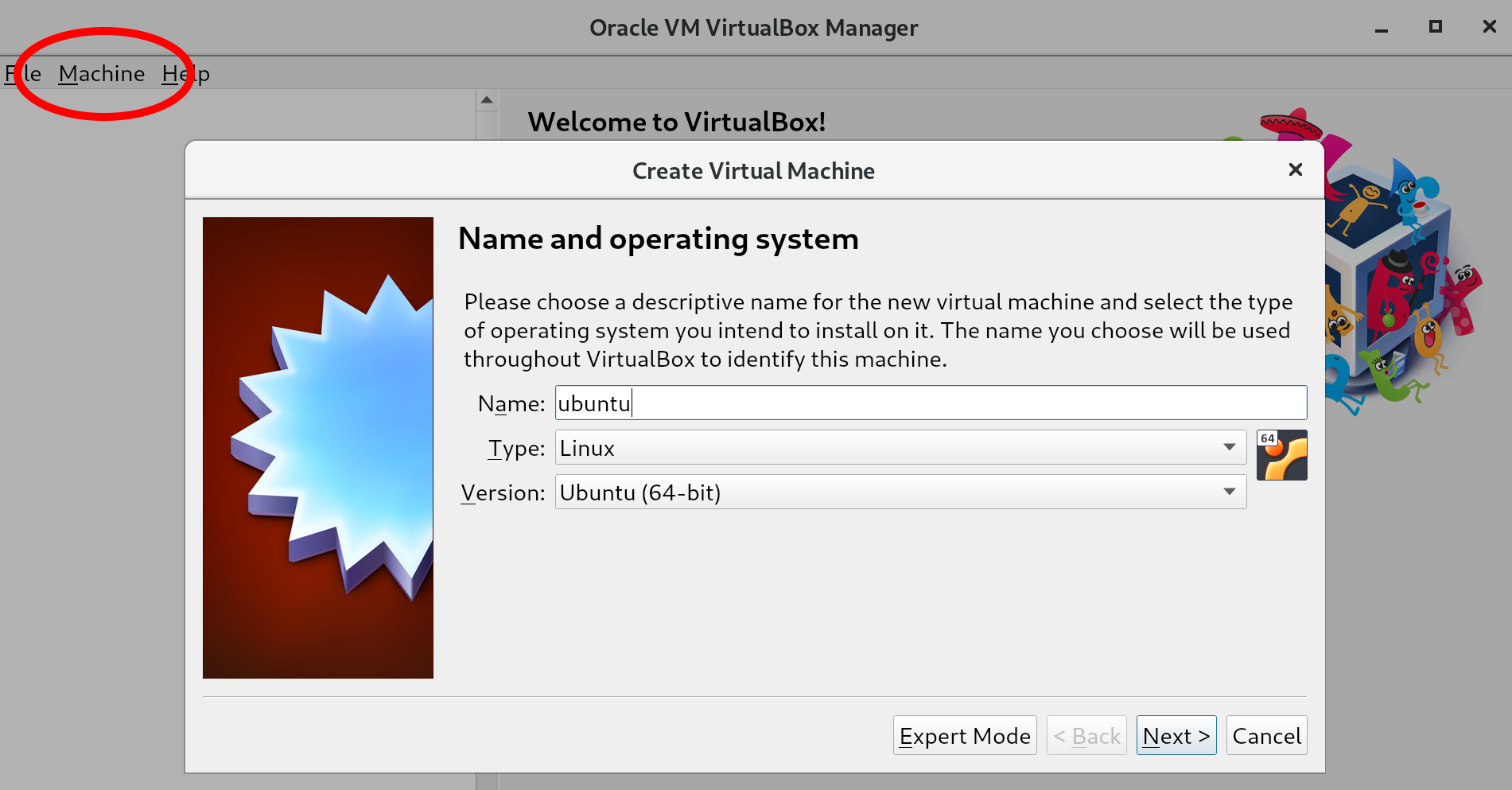

Presently, VirtualBox is owned by Oracle. You can download the installer for VirtualBox from https://www.virtualbox.org/. Installation should not be hard; follow the instructions by the installer.

In this book, we're scripting with Bash, which means we do not need a GUI for our Linux installation. We have chosen to use Ubuntu Server 18.04 LTS as the virtual machine operating system, for a number of reasons:

At the time of writing, Ubuntu is maintained by Canonical. You can download the ISO image from https://www.ubuntu.com/download/server. Download the file now, and remember where you save this file, since you'll need it soon.

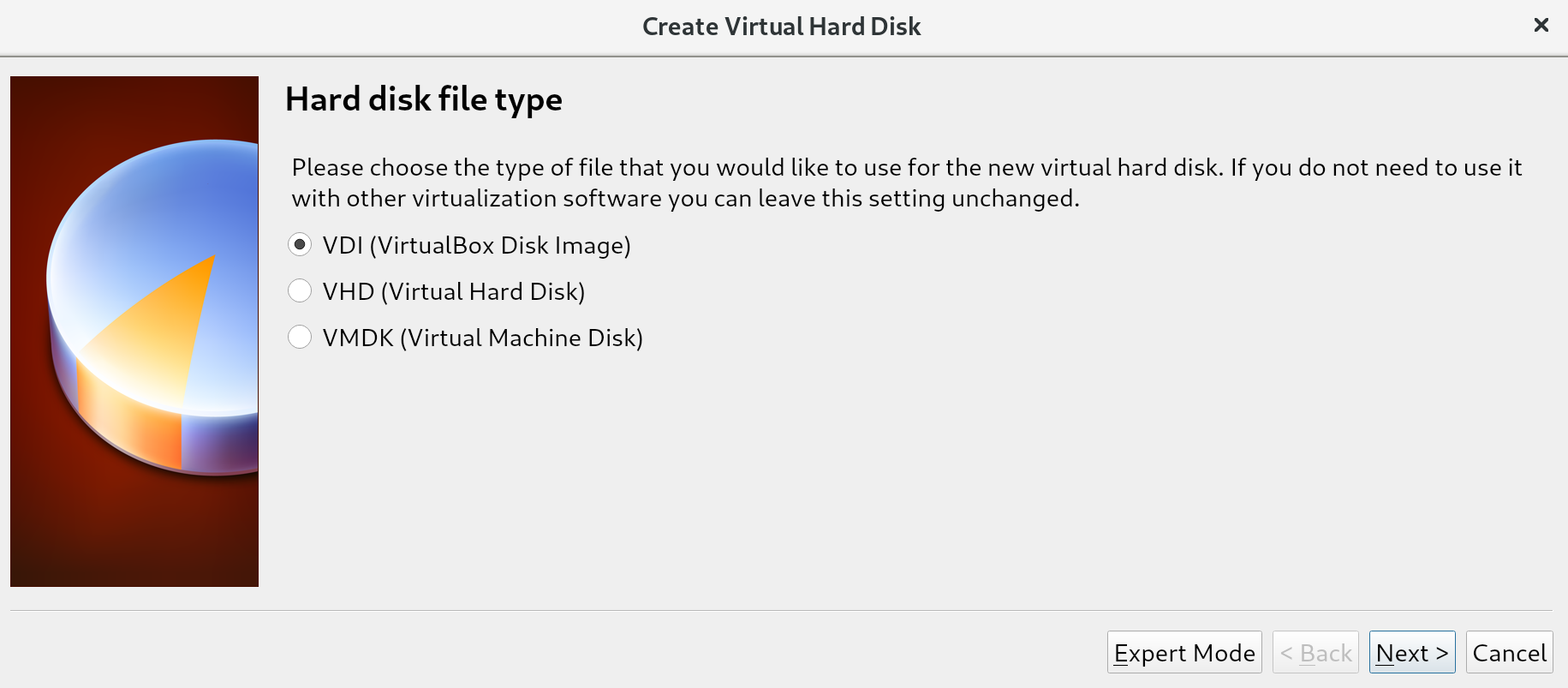

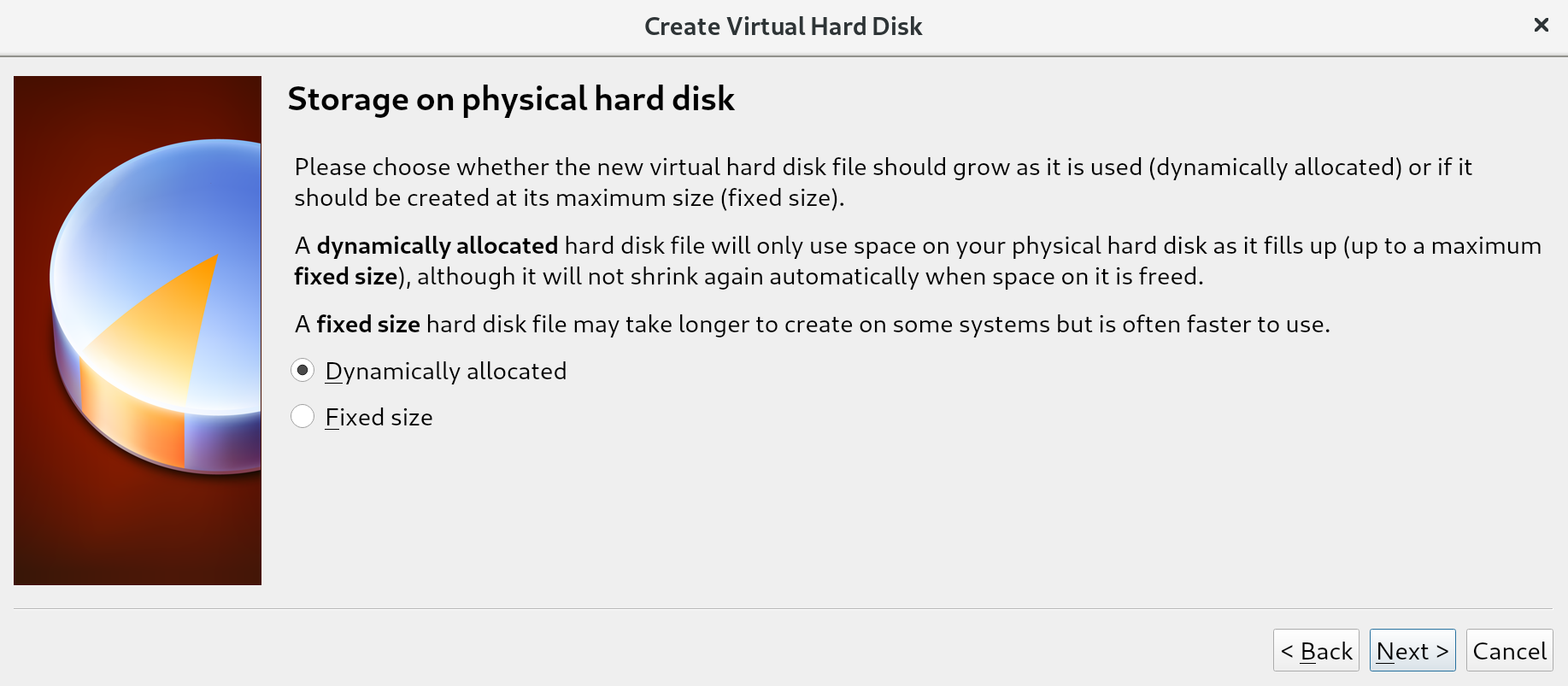

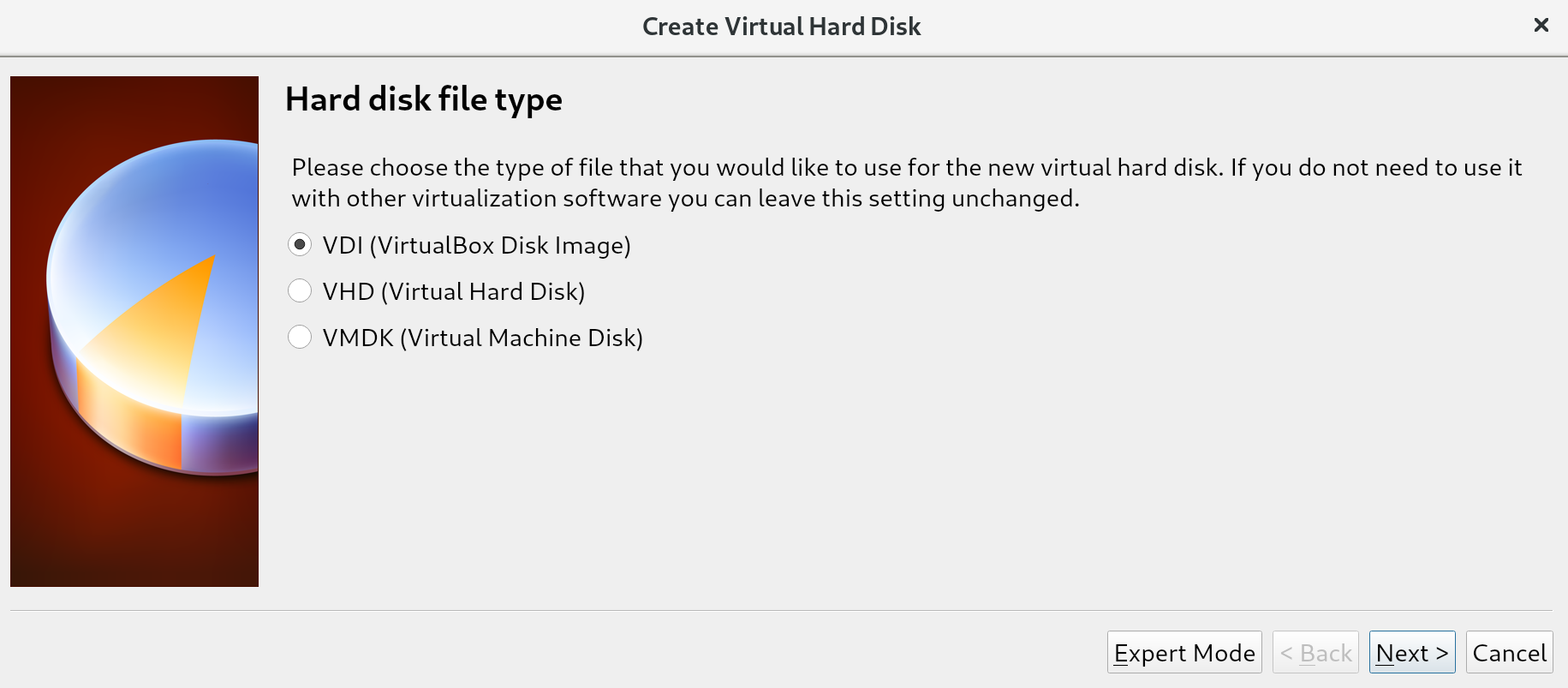

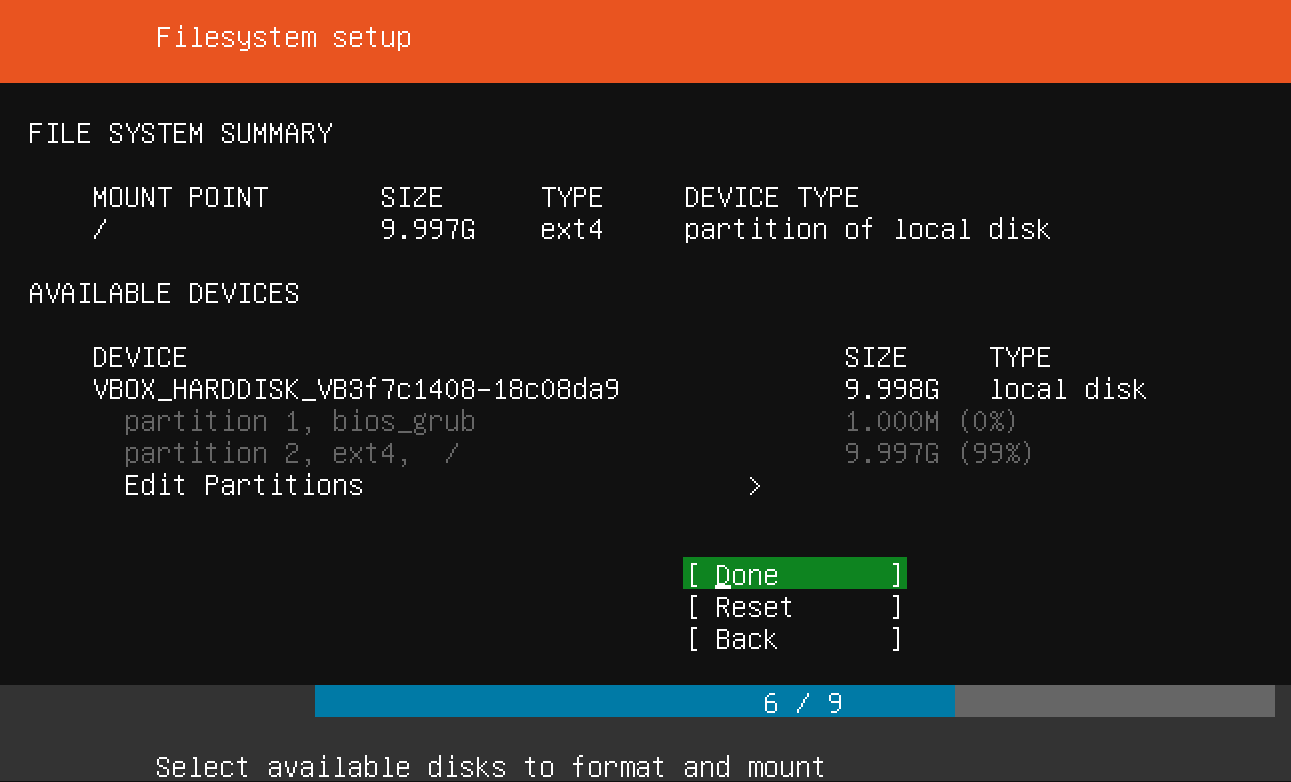

First, we will start with creating the virtual machine to host our Ubuntu installation:

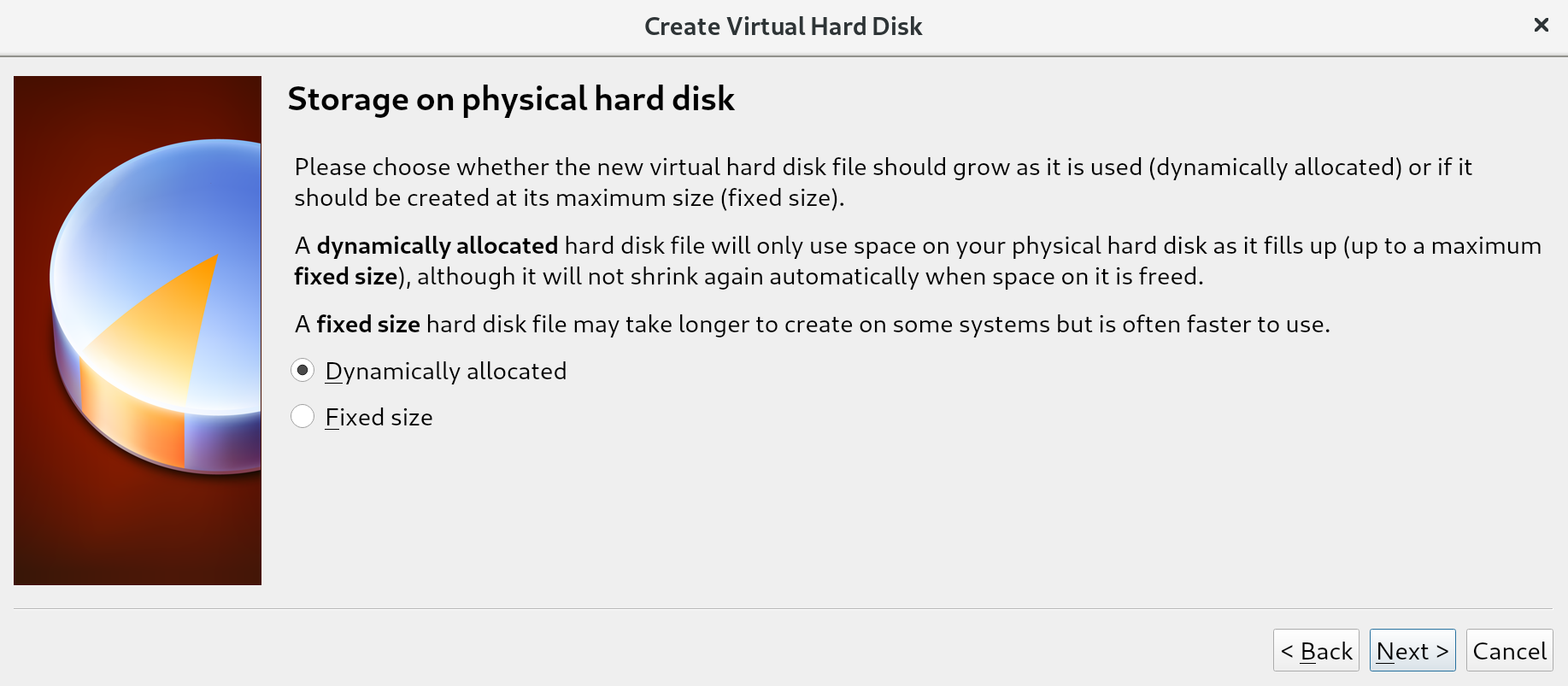

The difference between these options is often most relevant in situations where many virtual machines are running on a single host. Creating a total of disks larger than what is physically available, but assuming not all disks will be fully used, allows us to place more virtual machines on a single machine. This is called overprovisioning, and will only work if not all disks are filled up (because we can never have more virtual disk space than we have physical disk space). For us, this distinction does not matter since we'll be running a single virtual machine; we keep the default of Dynamically allocated and go to the next screen:

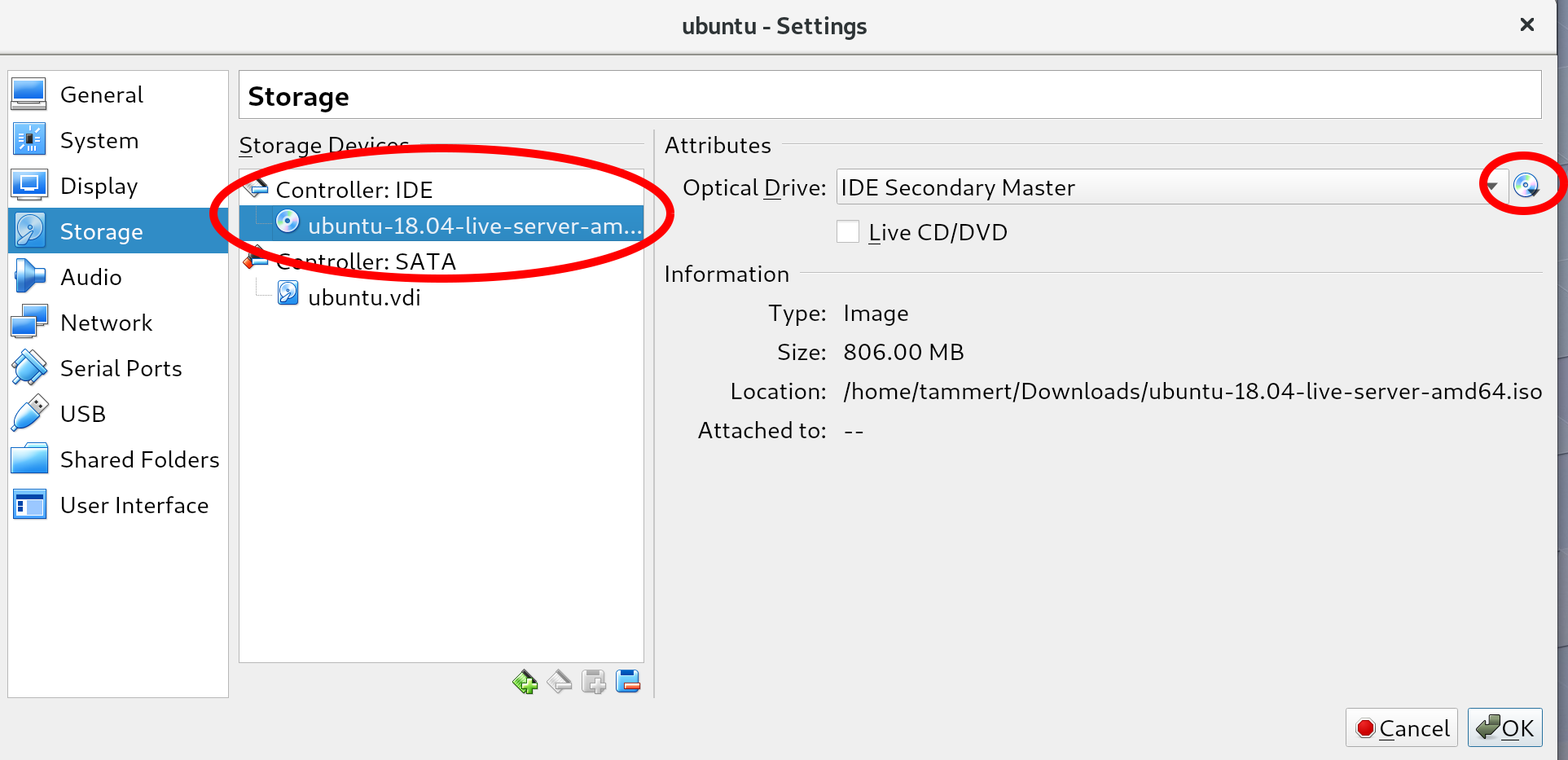

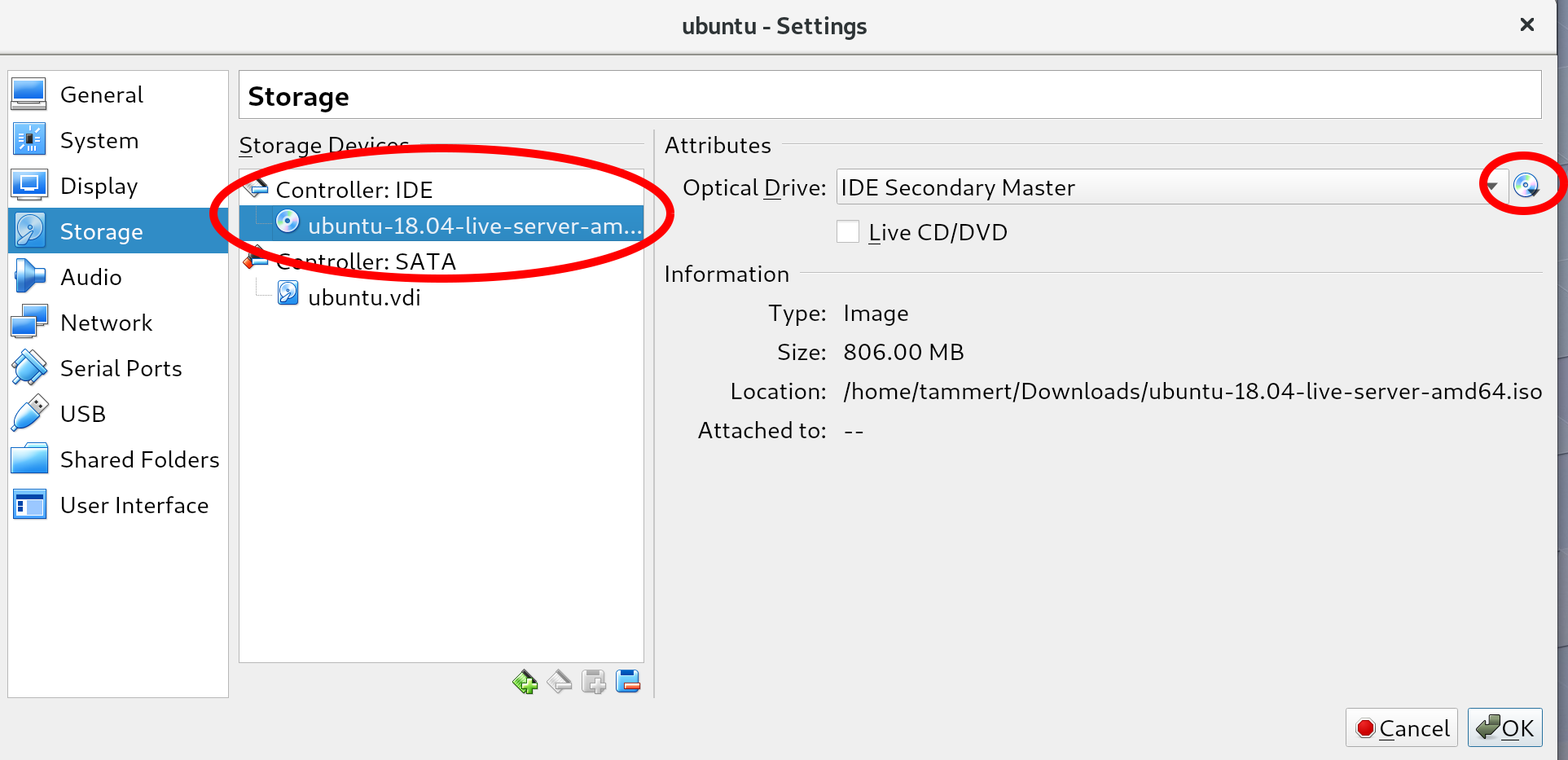

You should see a disk icon with the word Empty (in the location circled on the left in the preceding screenshot). Select it and mount an ISO file by clicking the select disk icon (circled on the right), choose virtual optical disk file, and then select the Ubuntu ISO that you downloaded earlier. If you do this correctly, your screen should resemble the preceding screenshot: you no longer see the word Empty next to the disk icon and the Information section should be filled in.

With this step, we've finished setting up the virtual machine!

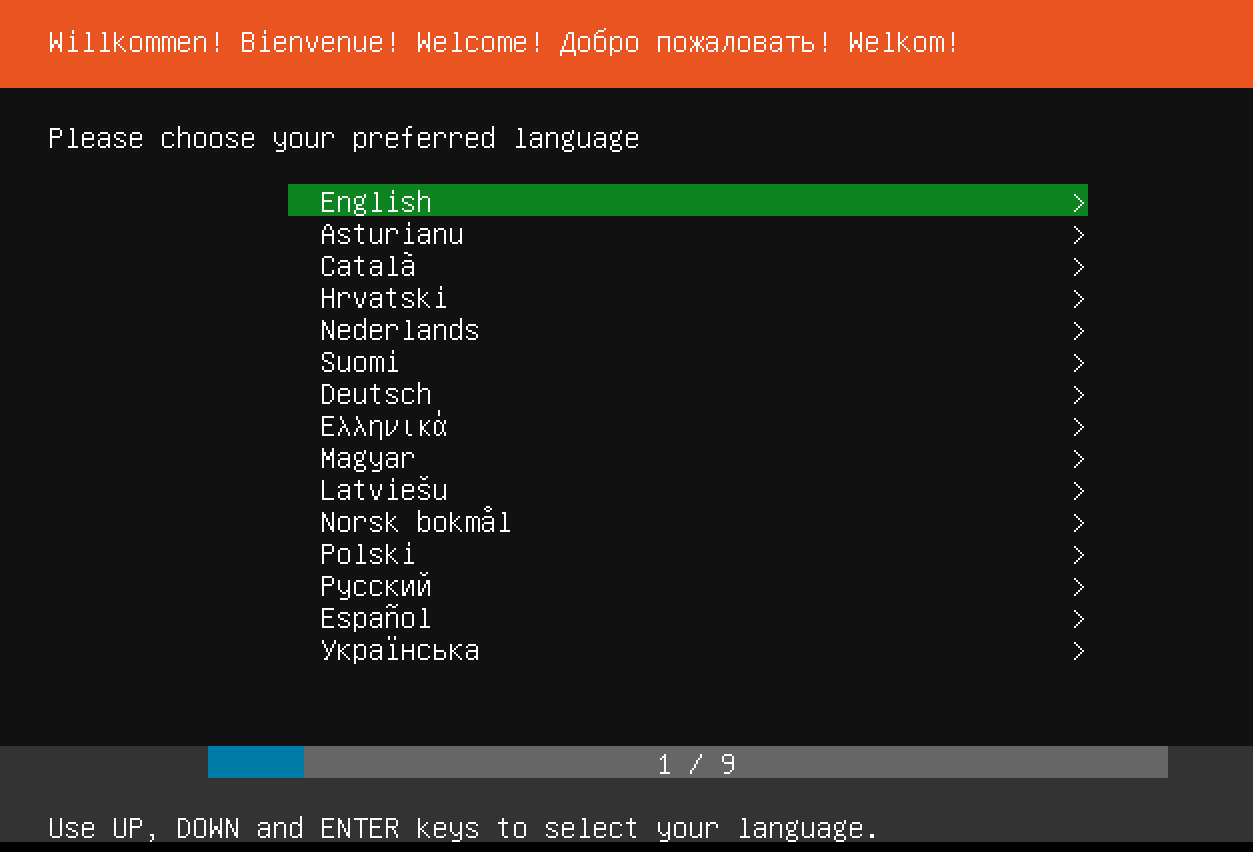

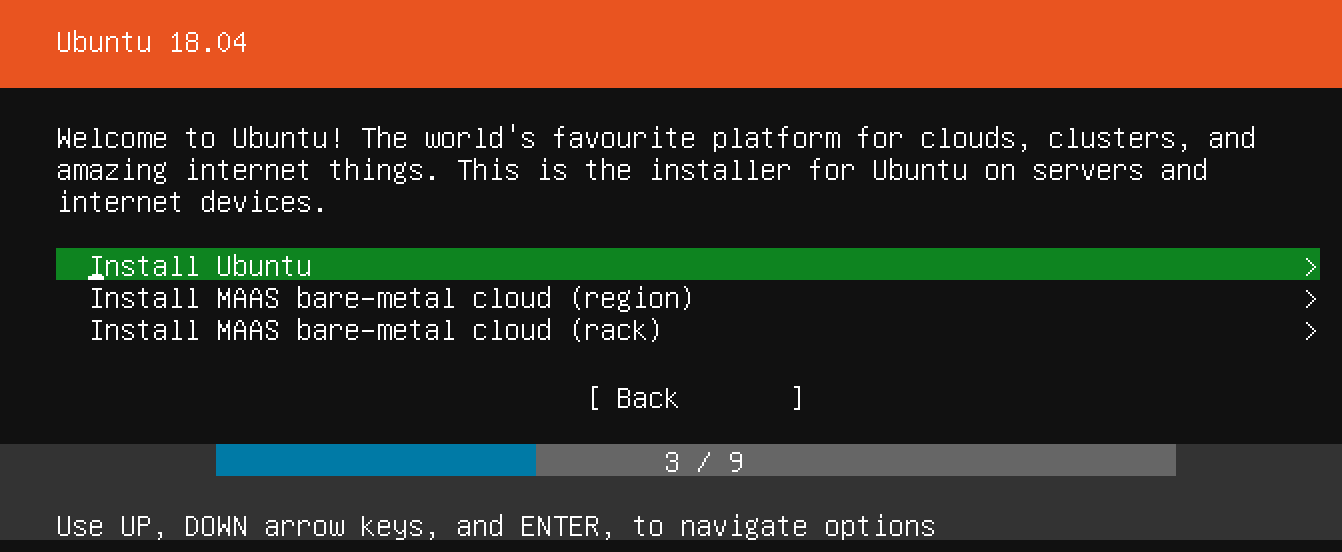

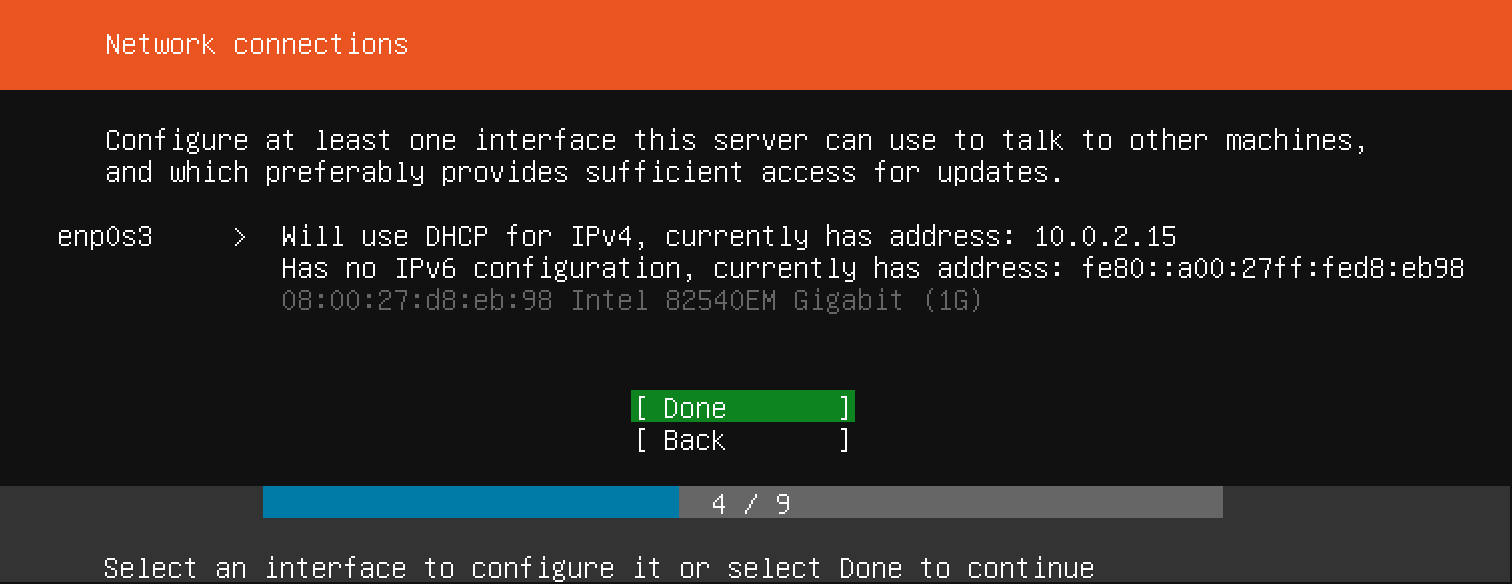

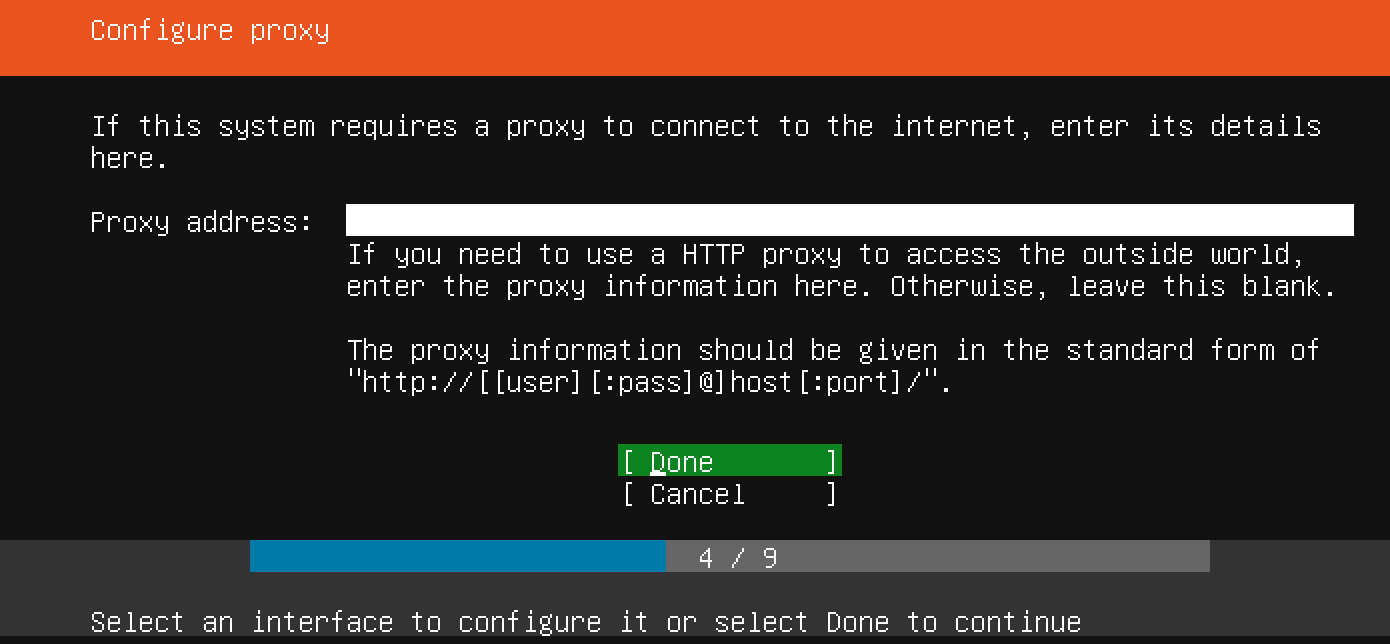

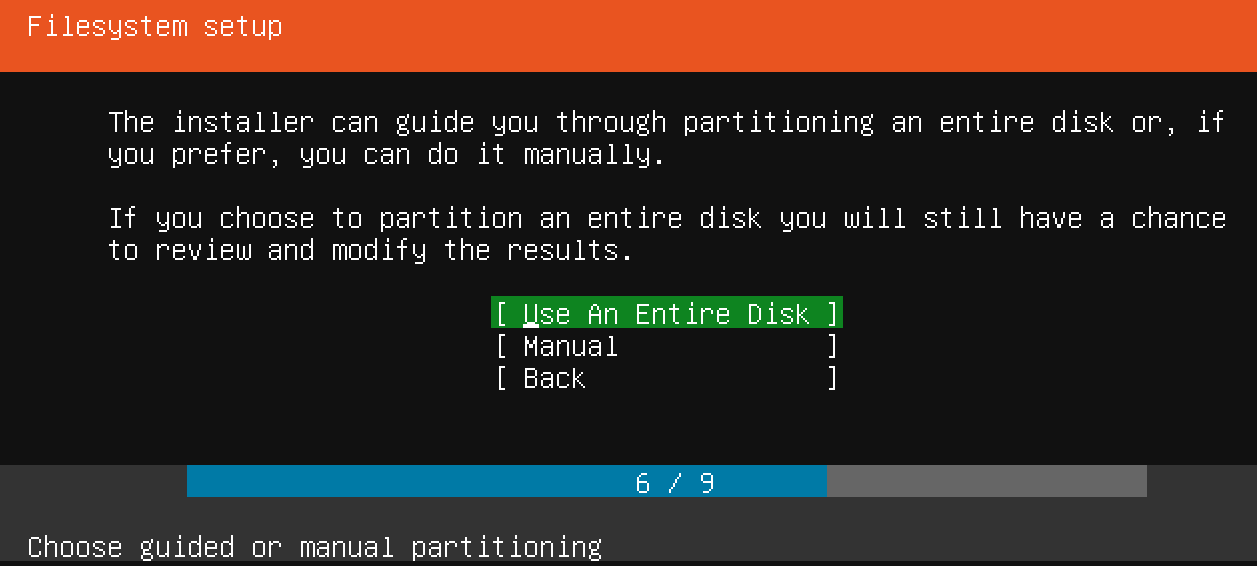

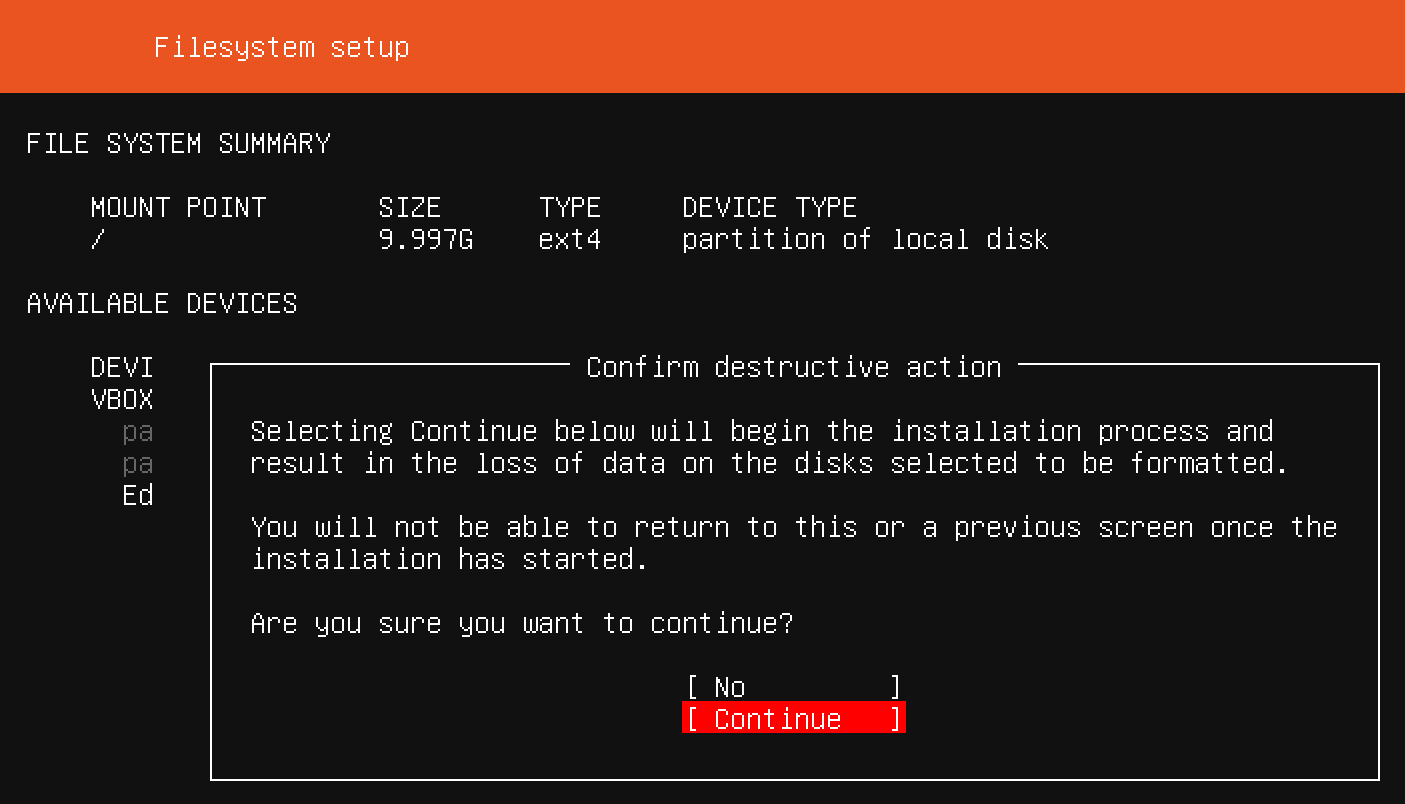

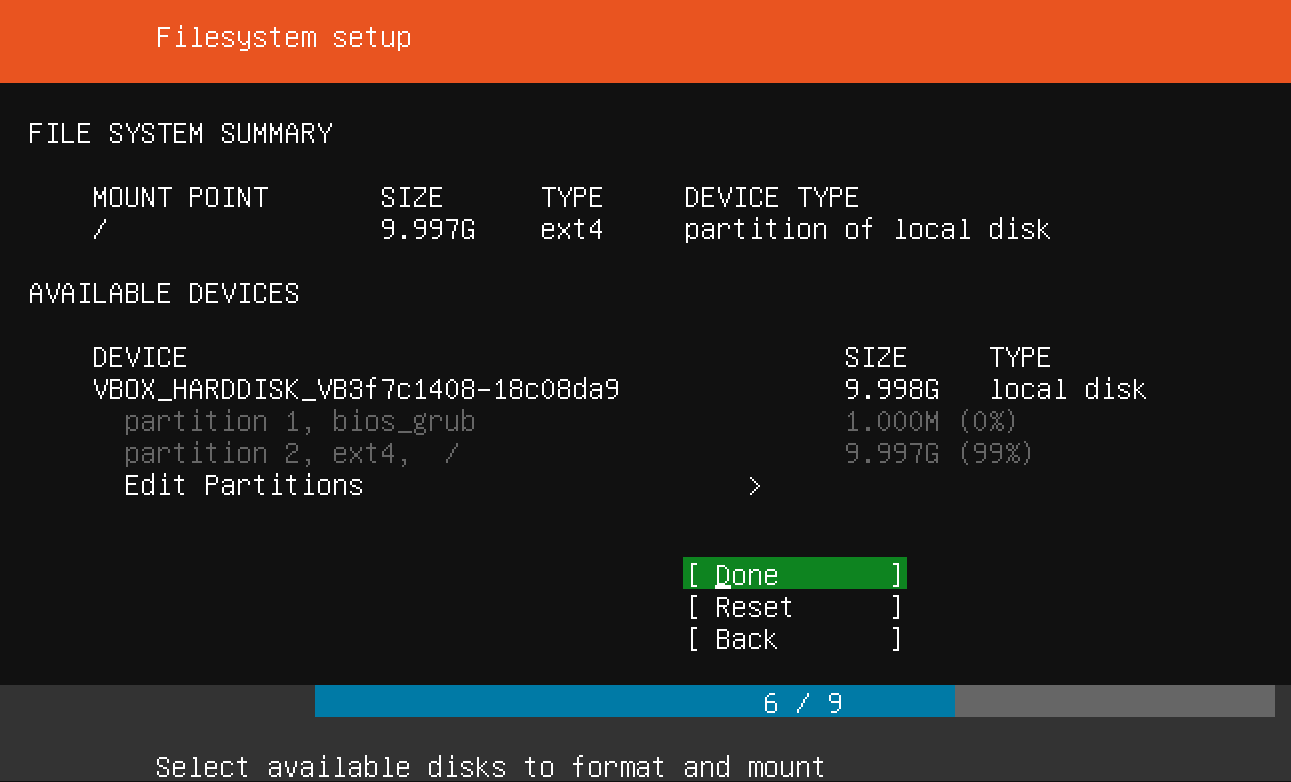

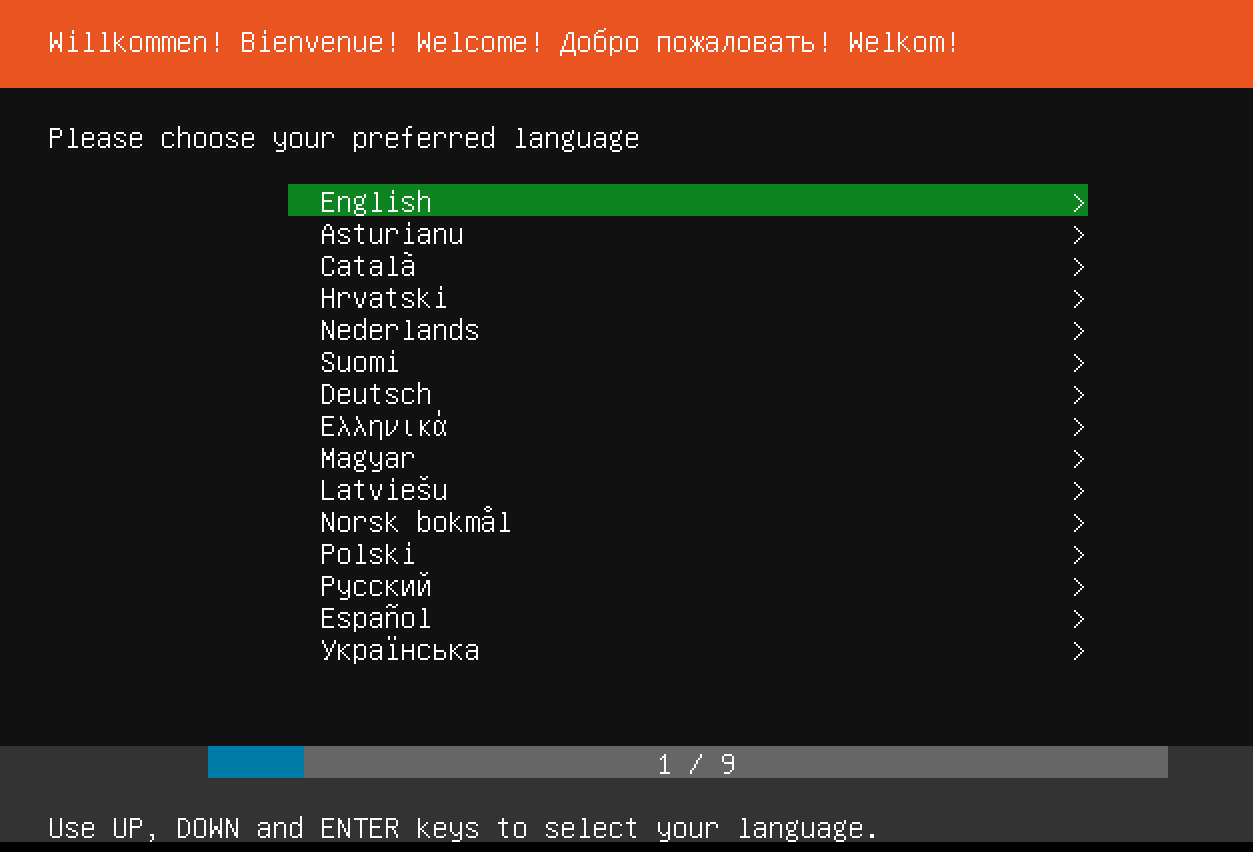

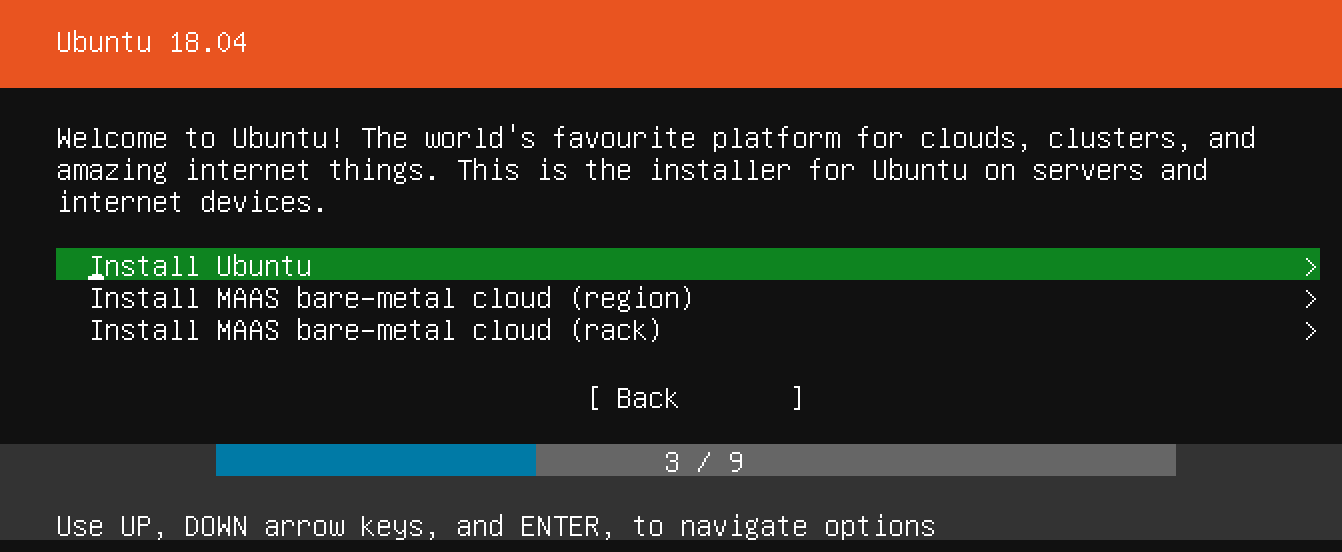

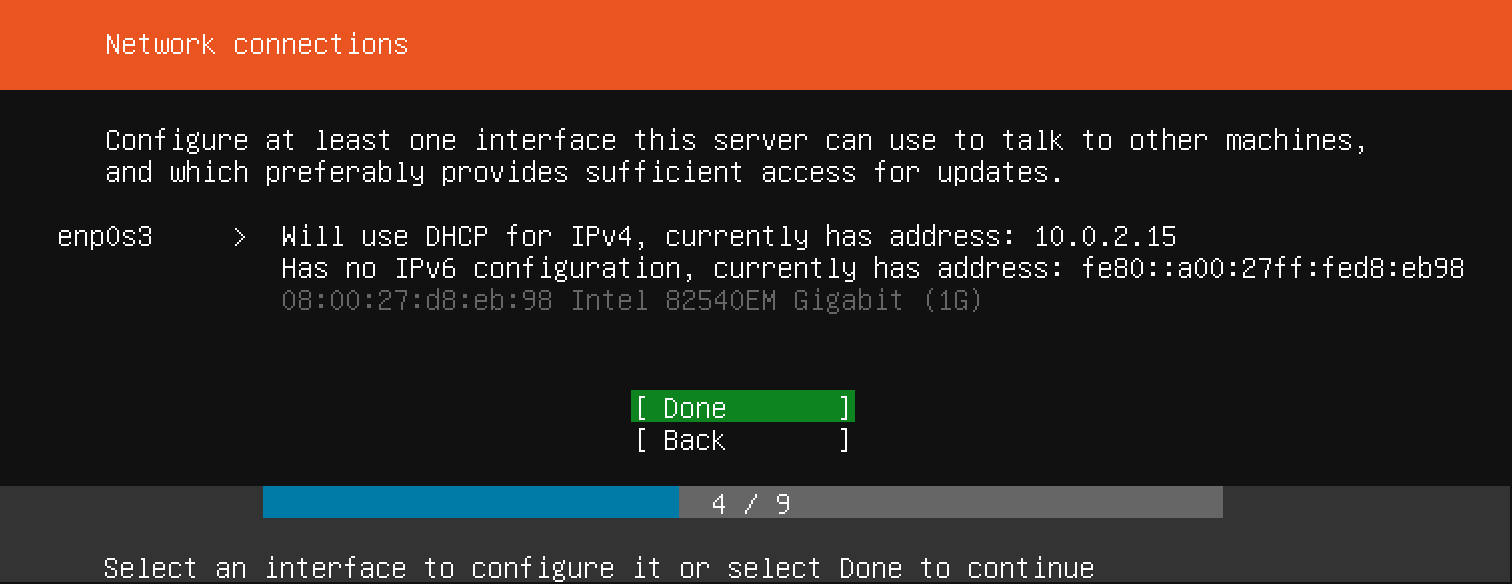

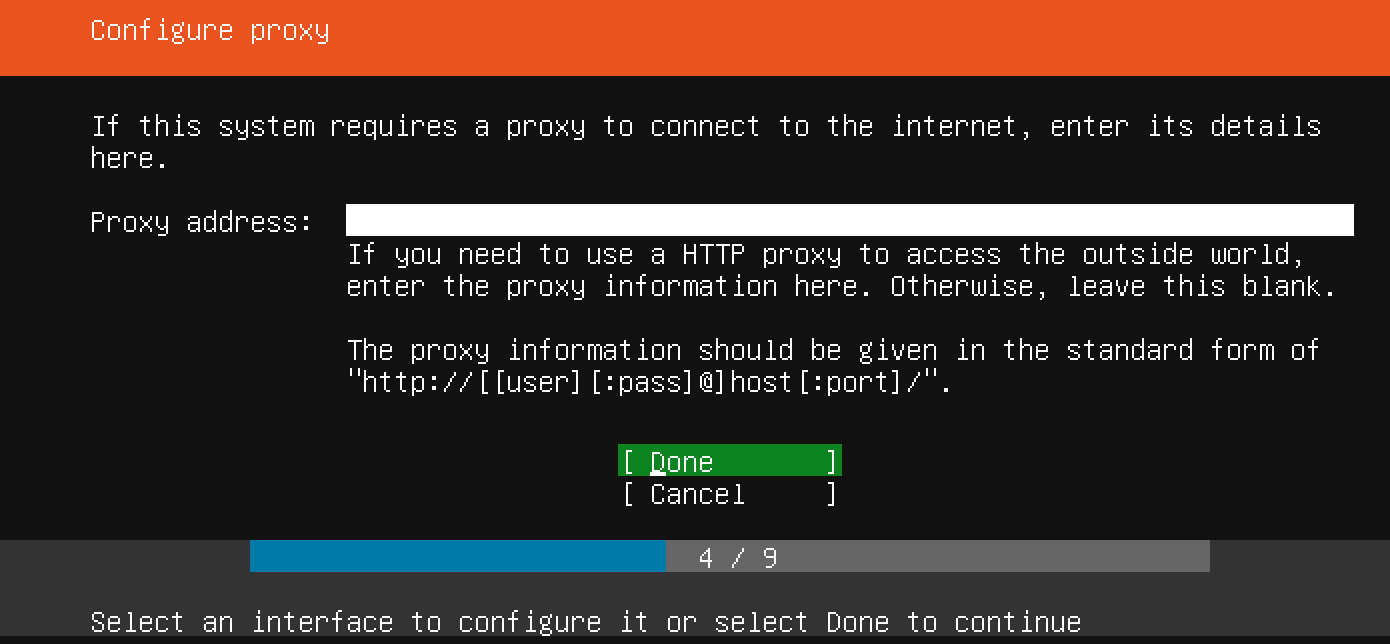

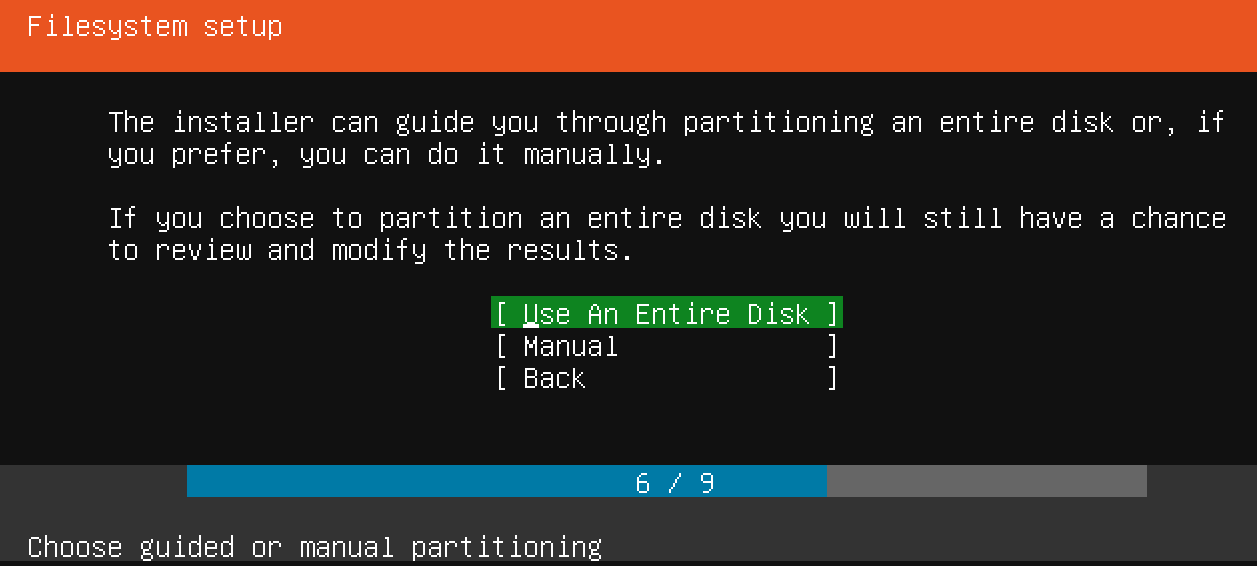

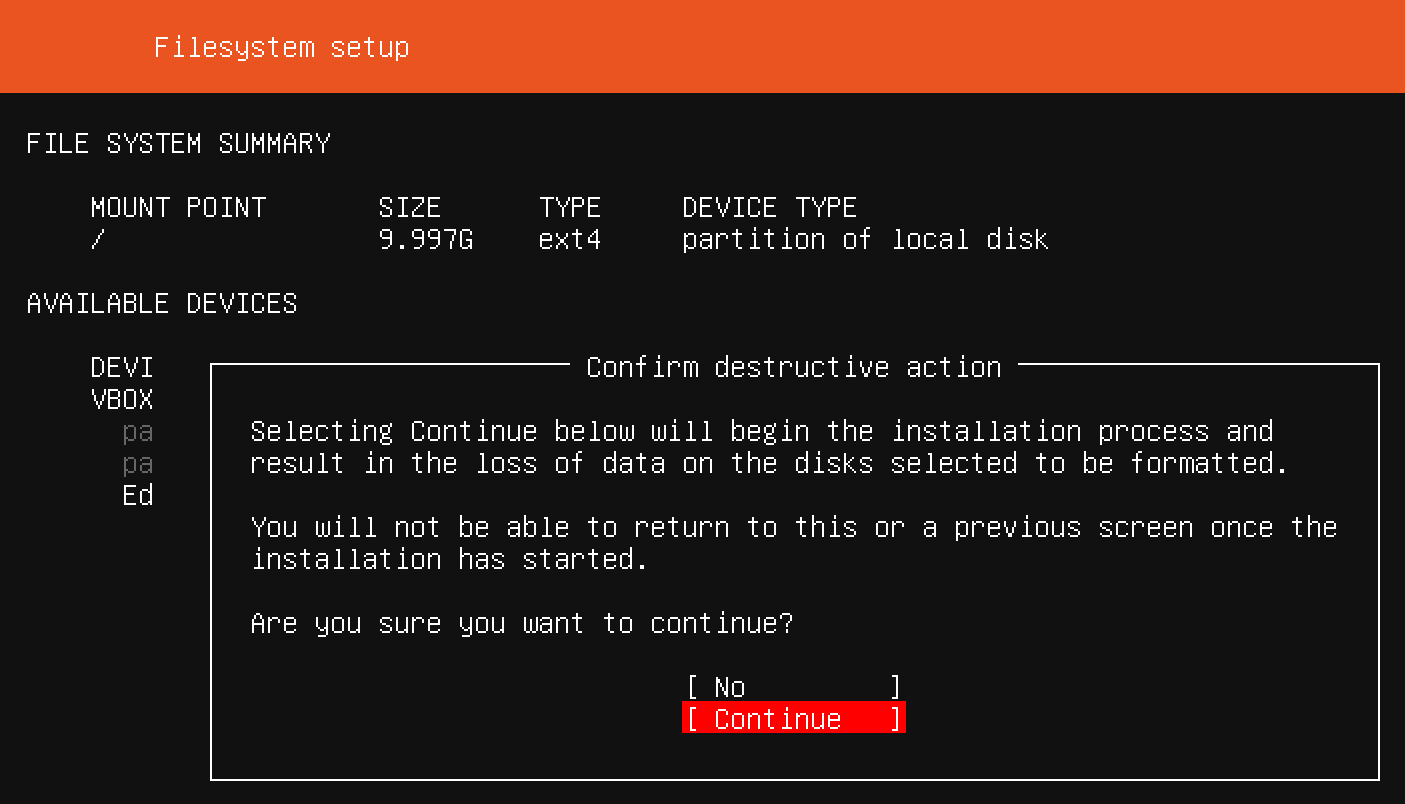

Now you can start your virtual machine from the VirtualBox main screen. Right click on the machine, select Start followed by Normal Start. If all goes well, a new window will pop up, showing you the virtual machine console. After a while, you should see the Ubuntu server installation screen in that window:

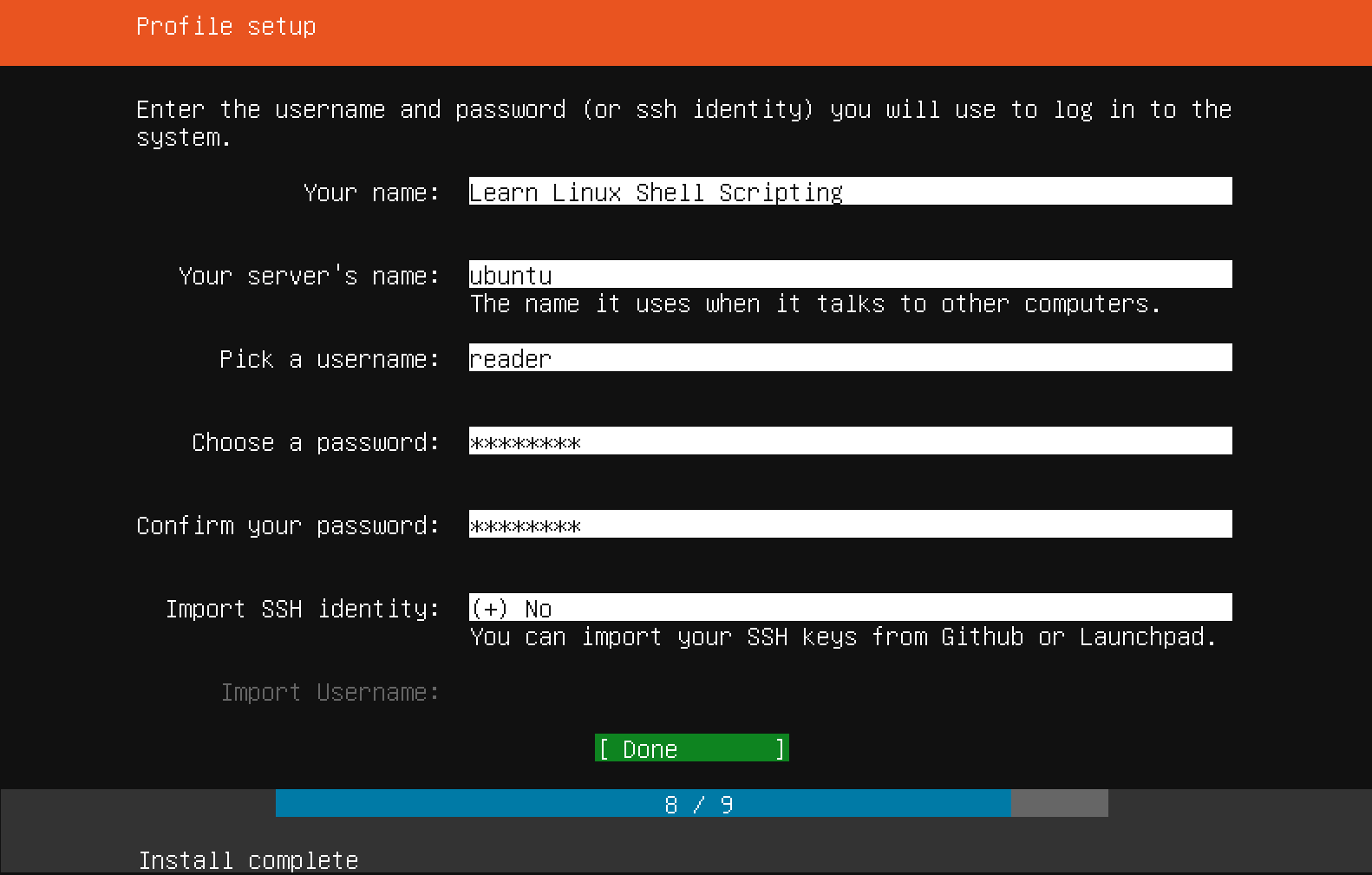

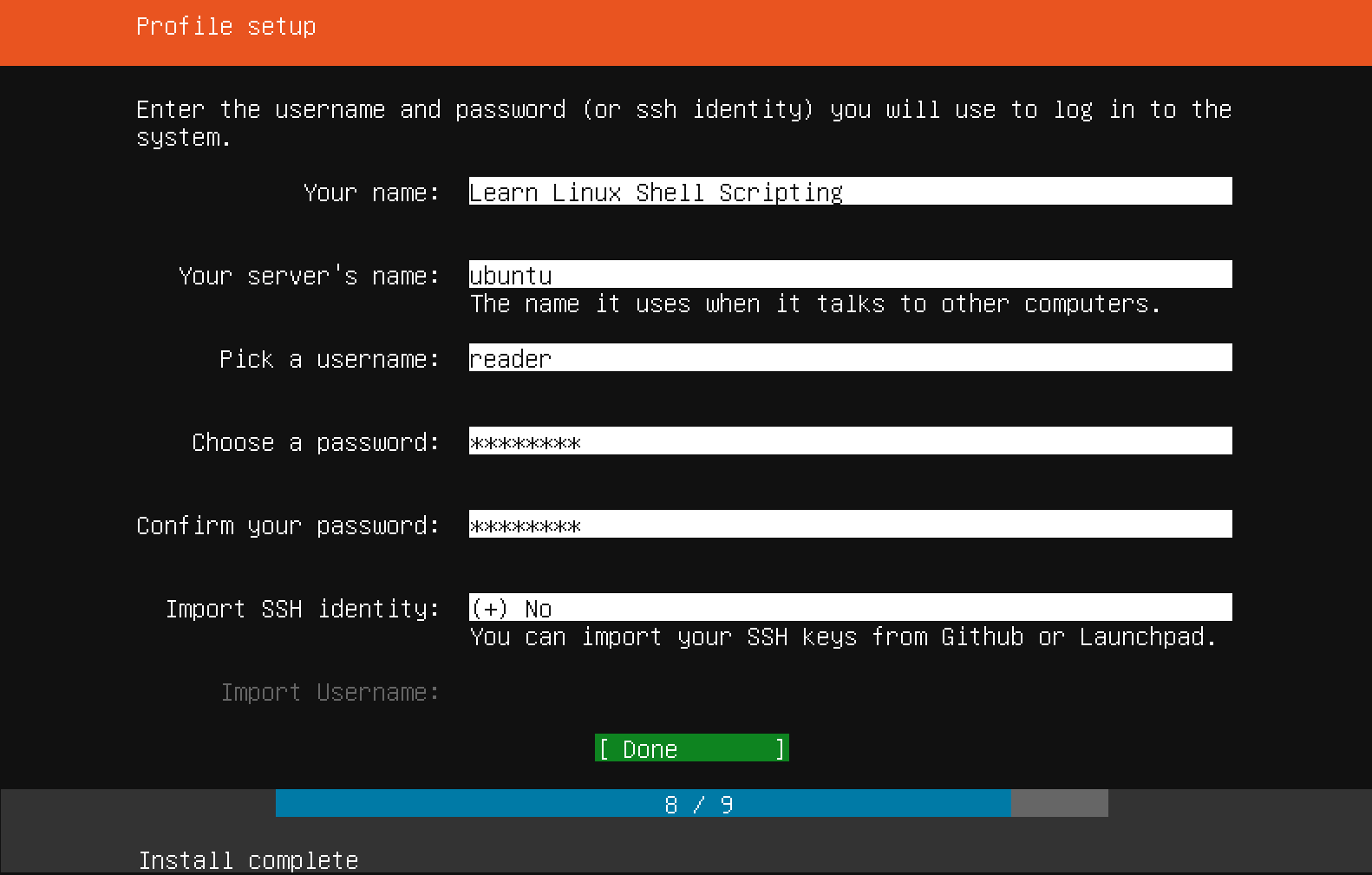

Now that you've chosen a server name and configured an administrative user, press Enter to finalize the installation.

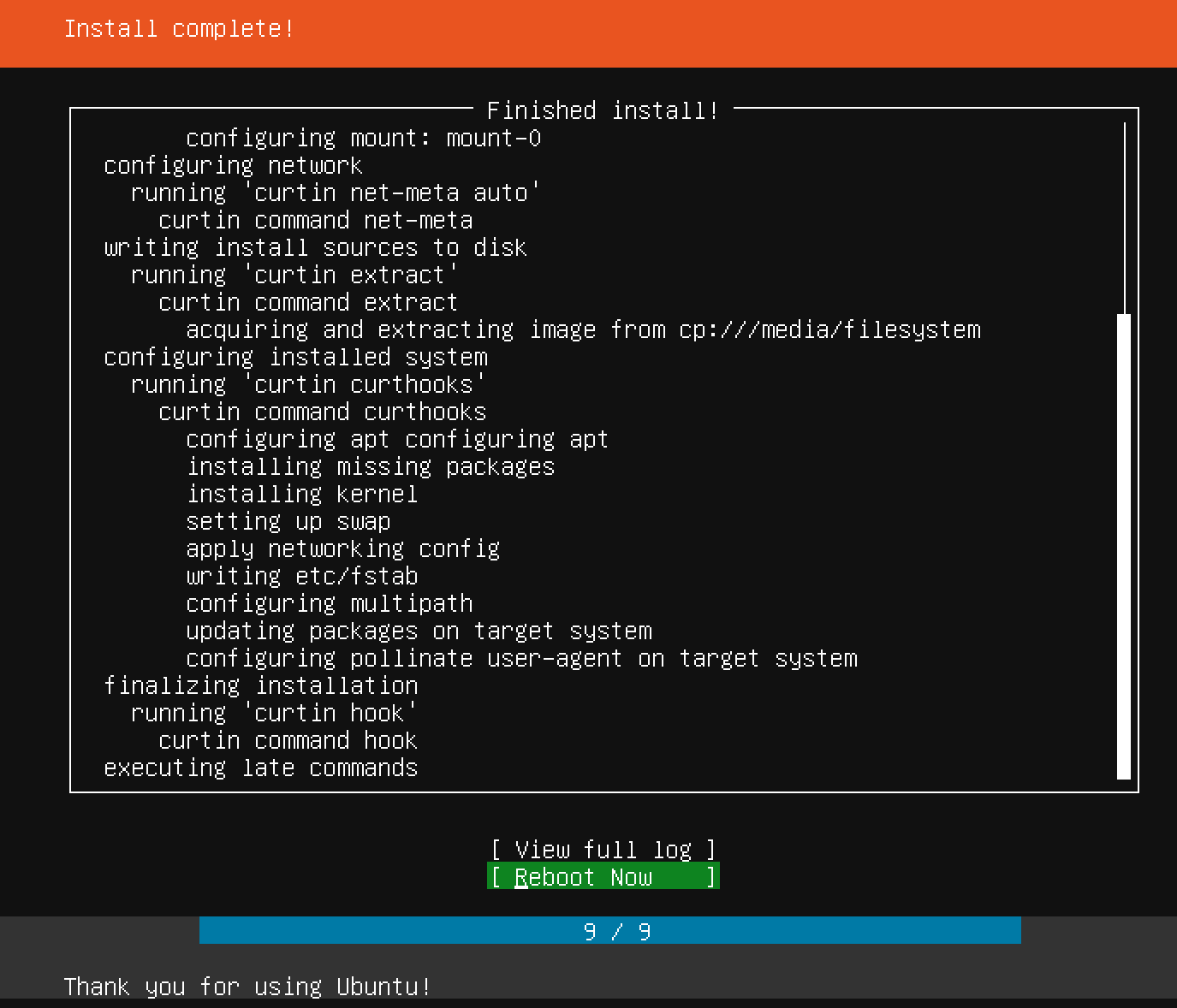

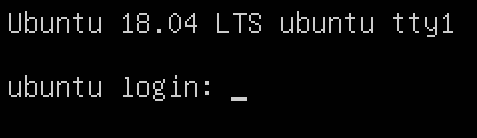

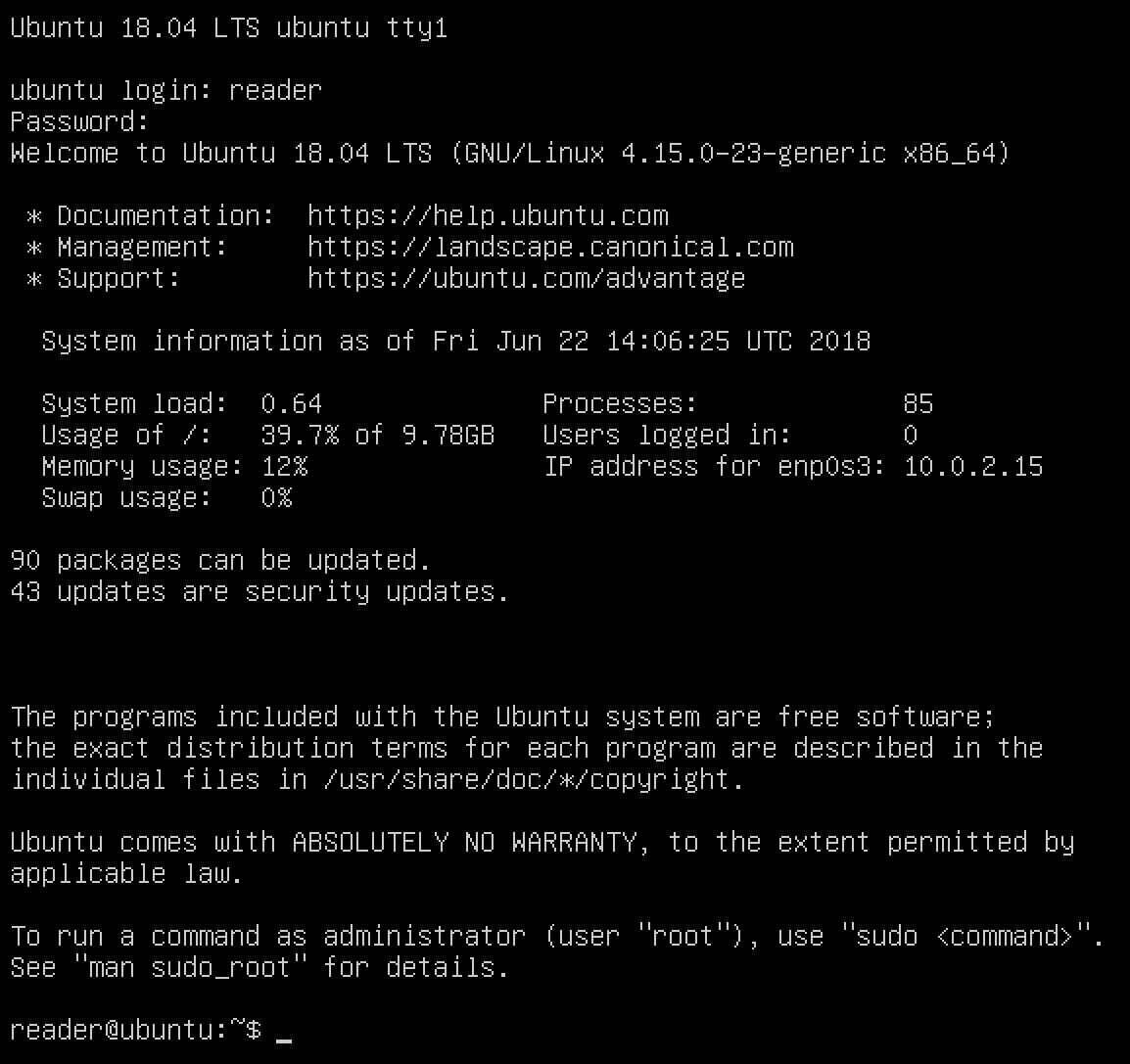

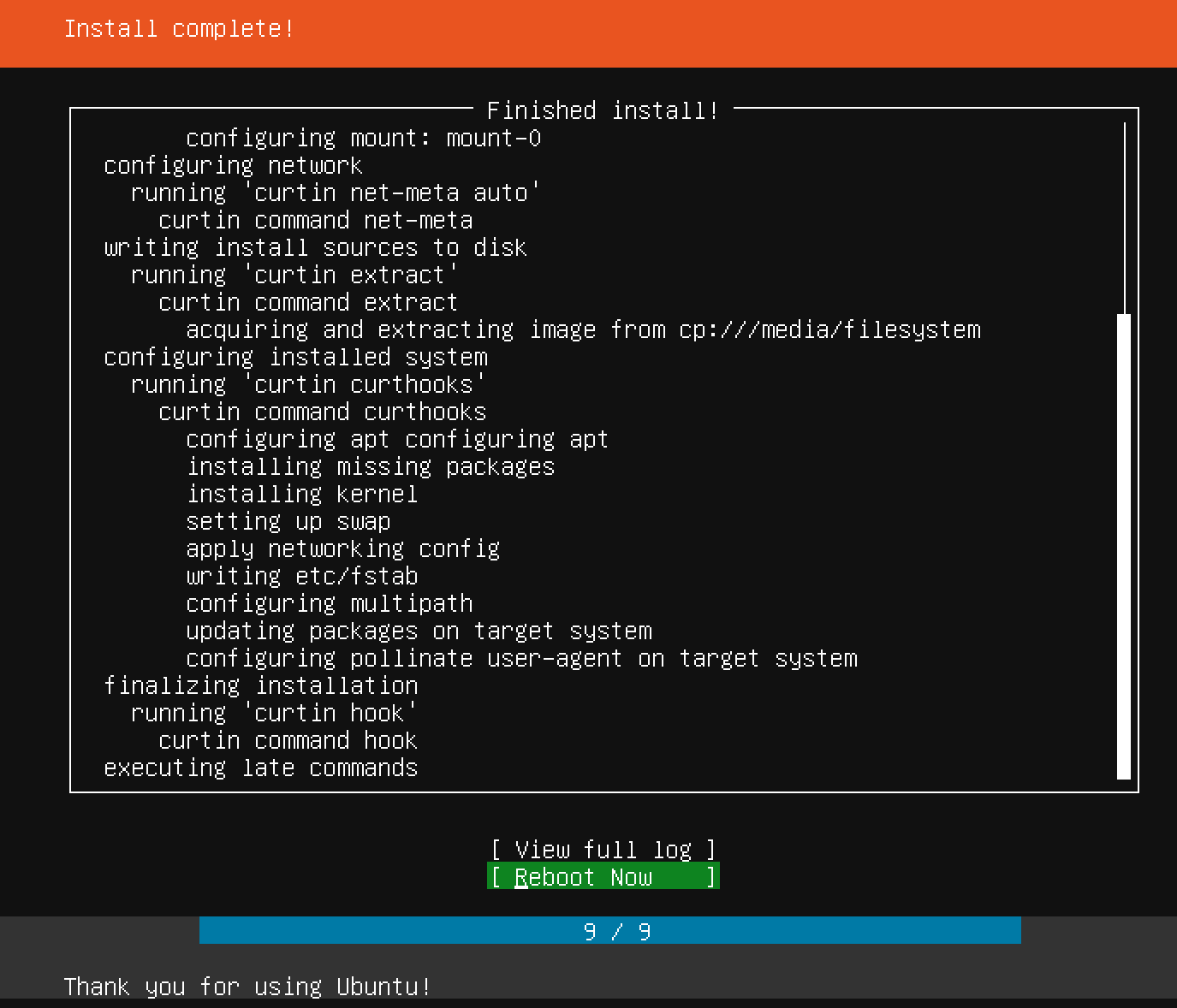

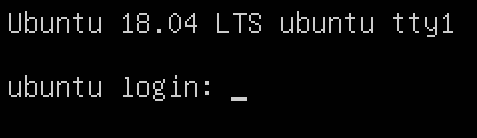

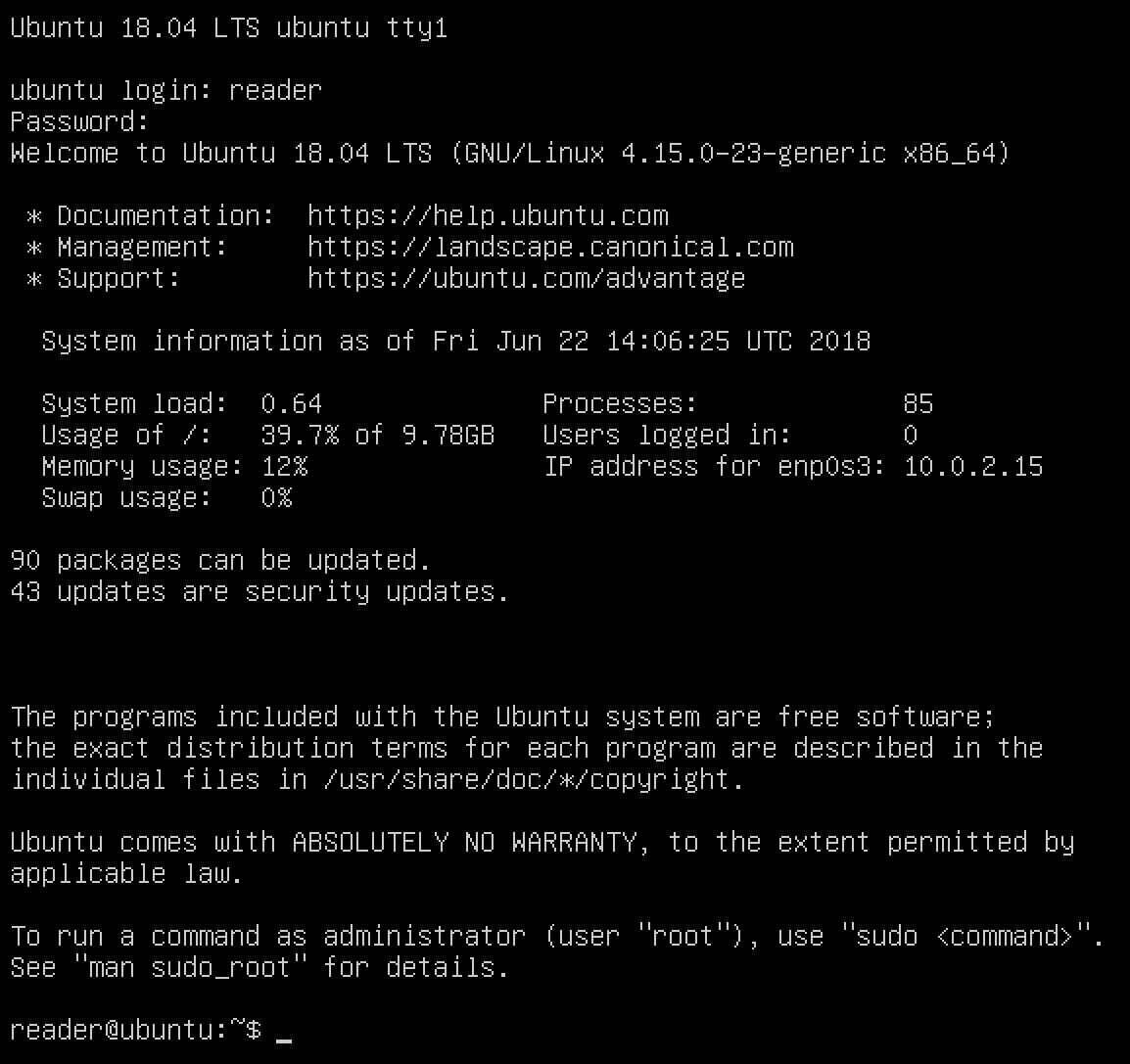

After a few seconds, a message stating Please remove the installation medium, then press Enter should appear. Follow the instructions and, if all goes well, you should be greeted with a terminal login prompt:

Give yourself a pat on the back: you have just created a virtual machine, installed Ubuntu Server 18.04 LTS, and logged in via the Terminal console. Well done! To exit, type exit or logout and press Enter.

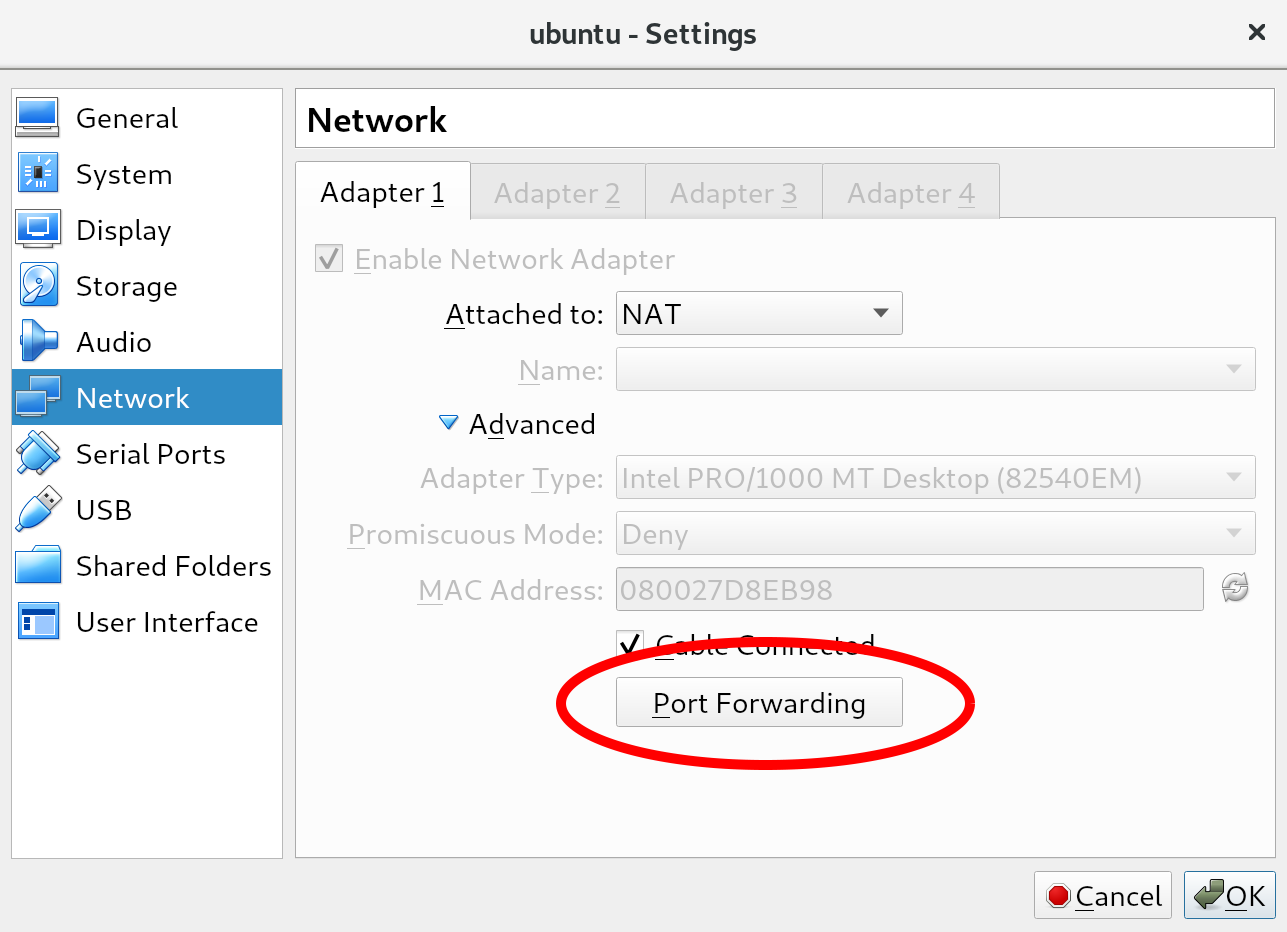

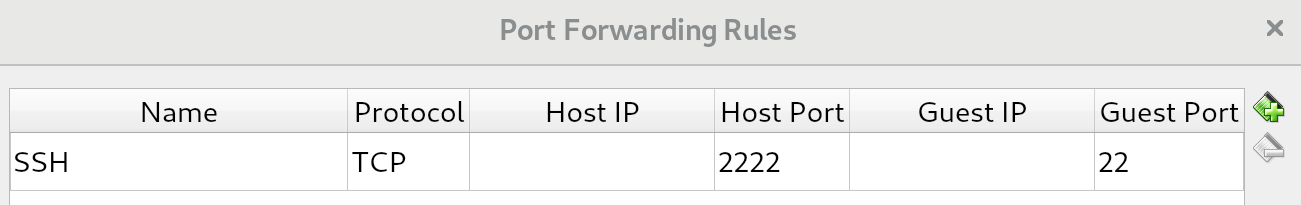

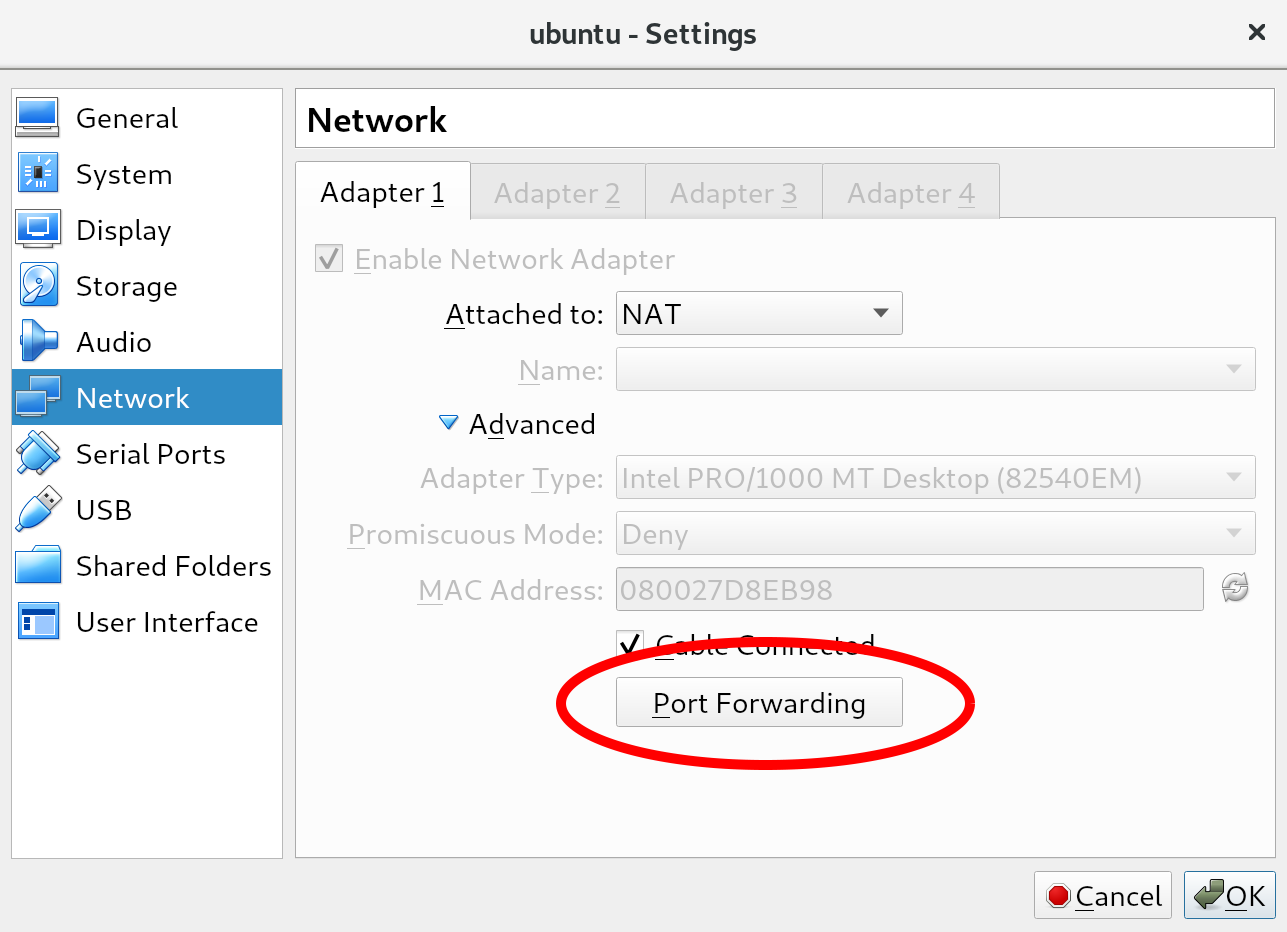

We have successfully connected to the Terminal console provided to us by VirtualBox. However, this Terminal connection is really basic: for example, we can't scroll up, we can't paste copied text, and we do not have colored syntax highlighting. Fortunately for us, we have a nice alternative: the Secure Shell (SSH) protocol. SSH is used to connect to the running shell on the virtual machine. Normally, this would be done over the network: this is how enterprises maintain their Linux servers. In our setup, we can actually use SSH within our host machine, using the power forwarding we set up earlier.

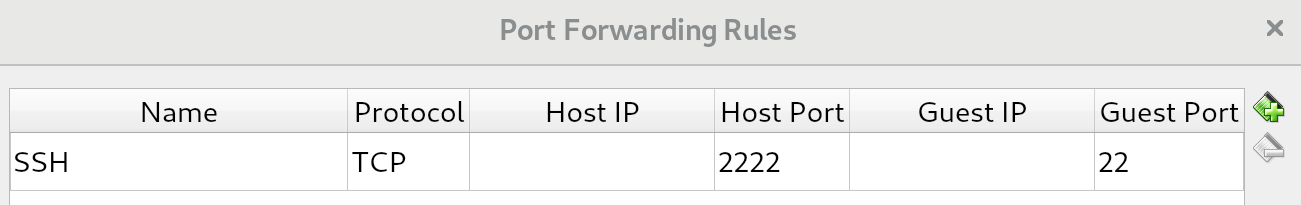

If you followed the installation guide, port 2222 on the host machine should be redirected to port 22 on the virtual machine, the port where the SSH process is running. From a Linux or macOS host machine, we can connect using the following command (substitute the username or port number if necessary):

$ ssh reader@localhost -p 2222

However, there is a good chance you're running Windows. In that case, you will probably not have access to a native SSH client application within Command Prompt. Luckily, there are many good (and free!) SSH clients. The simplest and most well-known client is PuTTY. PuTTY was created in 1999 and, while it's definitely a very stable client, its age is starting to show. We would recommend some newer SSH client software, such as MobaXterm. This provides you with more session management, a better GUI, and even a local Command Prompt!

Whichever software you decide on, be sure to use the following values (again, change the port or username if you deviated from the installation guide):

In this chapter, we have started preparing our local machine for the rest of the book. We now know about the differences between virtual and physical machines, and why we prefer to use a virtual machine for the remainder of this book. We've learned about the two different types of hypervisors. We have installed and configured VirtualBox with a virtual machine, on which we have installed the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system. Finally, we have connected to our running virtual machine using SSH instead of the VirtualBox terminal, which affords better usability and options.

The following command was introduced in this chapter: ssh and exit.

In the next chapter, we will finish setting up our local machine by looking at some different tools we can use that will help us with bash scripting, both on the GUI and on the virtual machine CLI.

The following resources might be interesting if you'd like to go deeper into the subjects of this chapter:

This chapter will introduce some tools that will help us when we're writing Bash scripts. We will focus on two types of tools: GUI-based editors (Atom and Notepad++) and Terminal-based editors (Vim and nano). We will describe the tools and how to use them, their strengths and weaknesses, and how to use both GUI- and Terminal-based editors together for the best results.

The following commands will be introduced in this chapter: vim, nano, and ls.

The following topics will be covered in this chapter:

You will need the virtual machine we created in the previous chapter when using Vim or nano. If you want to use Notepad++, you will need a Windows host machine. For Atom, the host machine can run either Linux, macOS, or Windows.

Tooling has come a long way since the first Unix and Unix-like distributions. In the earliest days, writing shell scripts was significantly harder than today: the shells were less powerful, text editors were command-line only and things such as syntax highlighting and autocomplete were non-existent. Today, we have very powerful GUI editors that will help us in our scripting adventures. Why would we want to wait until we run a script to find an error, when a GUI editor could have already shown us the error in advance? Today, using an advanced editor for shell scripting is almost a necessity that we wouldn't want to live without.

We'll describe two text editors in the coming pages: Atom and Notepad++. Both are GUI-based, which we can use for efficient shell scripting. If you have a preference for either already, pick that one. If you're unsure, we would recommend using Atom.

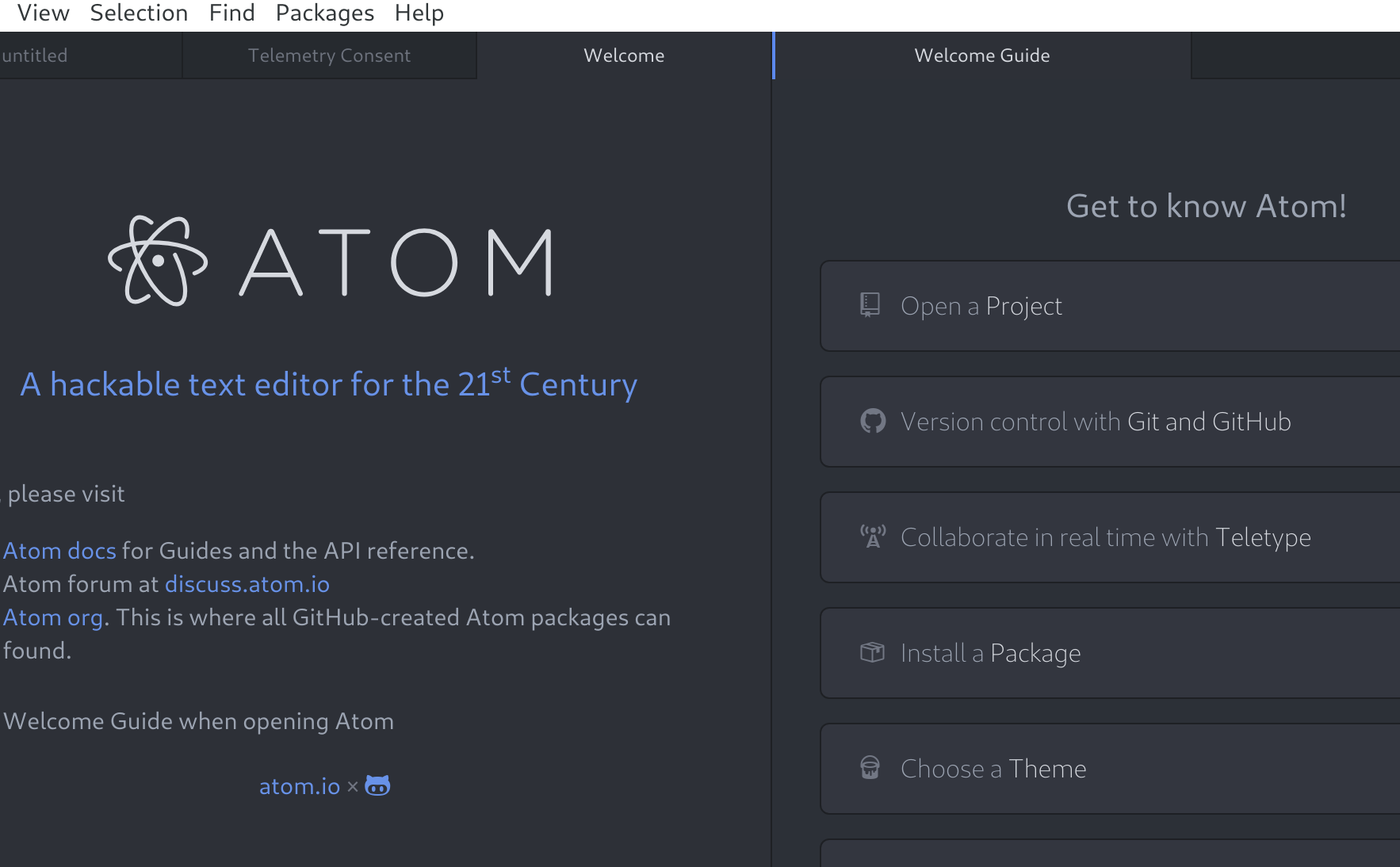

The first graphical editor we will consider is Atom, made by GitHub. It's described as A hackable text editor for the 21st Century. Hackable, in this sense, means that while the default installation of Atom is as complete as any text editor, this application really shines because it is very configurable and extensible. Anything that has not been integrated by GitHub can be written as an extension package. By using these extensions, you can make your Atom installation fully your own; if you do not like something, change it. If it can't be changed out of the box, find a package that does it. And even if there's not a package that does what you're hoping, you still have the option to create your own package!

Another nice feature of Atom is the default integration with Git and GitHub. Git is currently the most popular version control system. Version control systems are used when writing code or scripts. They ensure that history of files is preserved, and make it possible for multiple, even many, contributors to work on the same files at the same time, without getting burdened down by conflict management. GitHub, as the name suggests, is currently the most prominent web-based Git provider for open source software.

The last great thing about Atom we want to mention is that, by default, it supports many scripting and programming languages. When we say supports, we mean that it can recognize file types by their extensions, and offer syntax highlighting (which makes for much easier scripting!). This functionality is provided through core packages, which work the same way as normal packages but are included from the start. For our purposes, the core package, language-shellscript, will help us in our shell scripting endeavors.

Let's go ahead and install Atom. As long as you're running Linux, macOS, or Windows, you can go to https://atom.io/ and grab the installer. Run the installer and, if necessary, follow along with the prompts until Atom is installed. Now, start Atom and you'll be greeted by the welcome screen, which at the time of writing looks like the following:

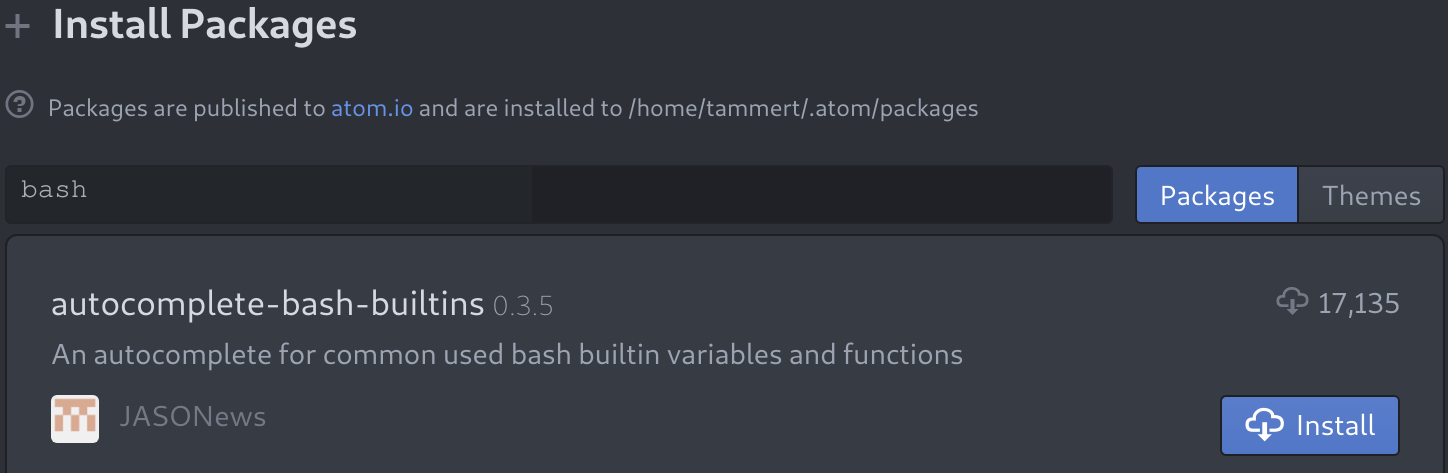

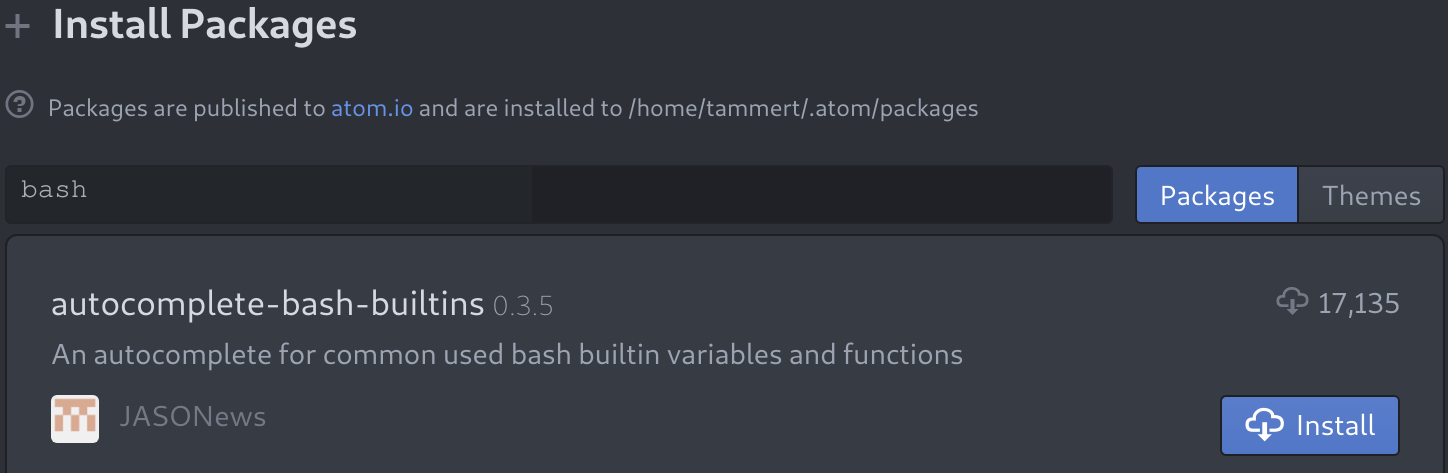

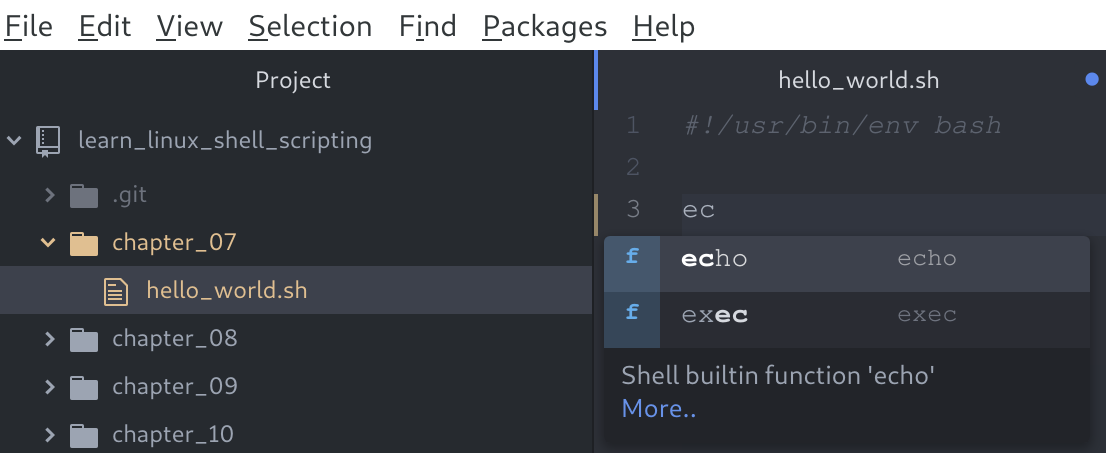

Be sure to look at all the screens Atom has to offer. When you feel like you've explored enough, let's add a package to Atom that will complement our shell scripting. If you have the Welcome Guide screen still open, select Install a Package from there. Otherwise, you can use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + , to bring up the Settings screen. You will see an Install option there, which will take you to the Install Packages screen. Search for bash, and you should see the following package:

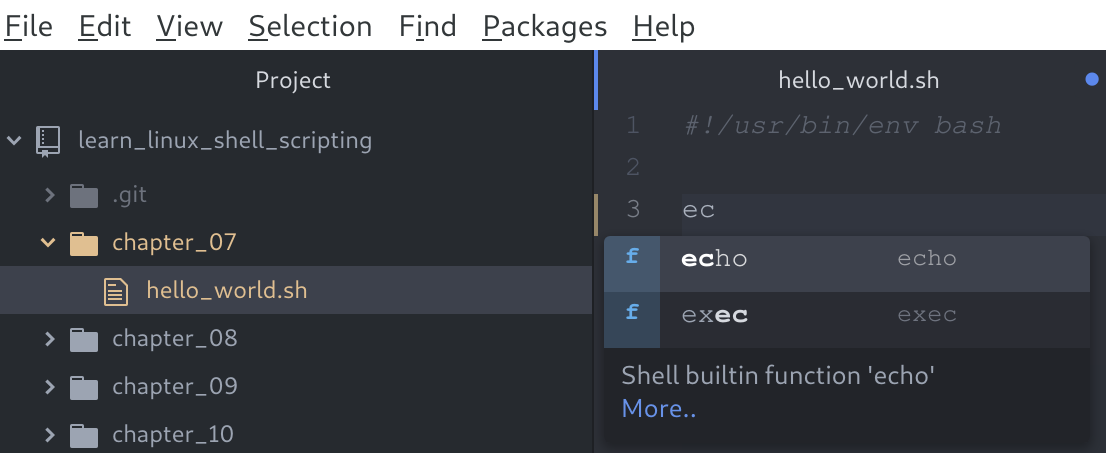

Click the Install button and watch the installation. You might be prompted to reboot Atom after the install; be sure to do so. If you're not prompted but see errors of any kind, a reboot of Atom is never a bad idea. After installing the package, you will now have autocomplete functionality when writing shell scripts. This means that you can start typing and Atom will try to predict what you want, in the following manner:

On the right-hand side, you can see we started typing the echo shell command, and after the first two letters, Atom presented us with two options that contain those two letters. Once it makes a suggestion, we can press Enter and the command is inserted fully. While it will not save much time in this instance, it can be great for two main reasons:

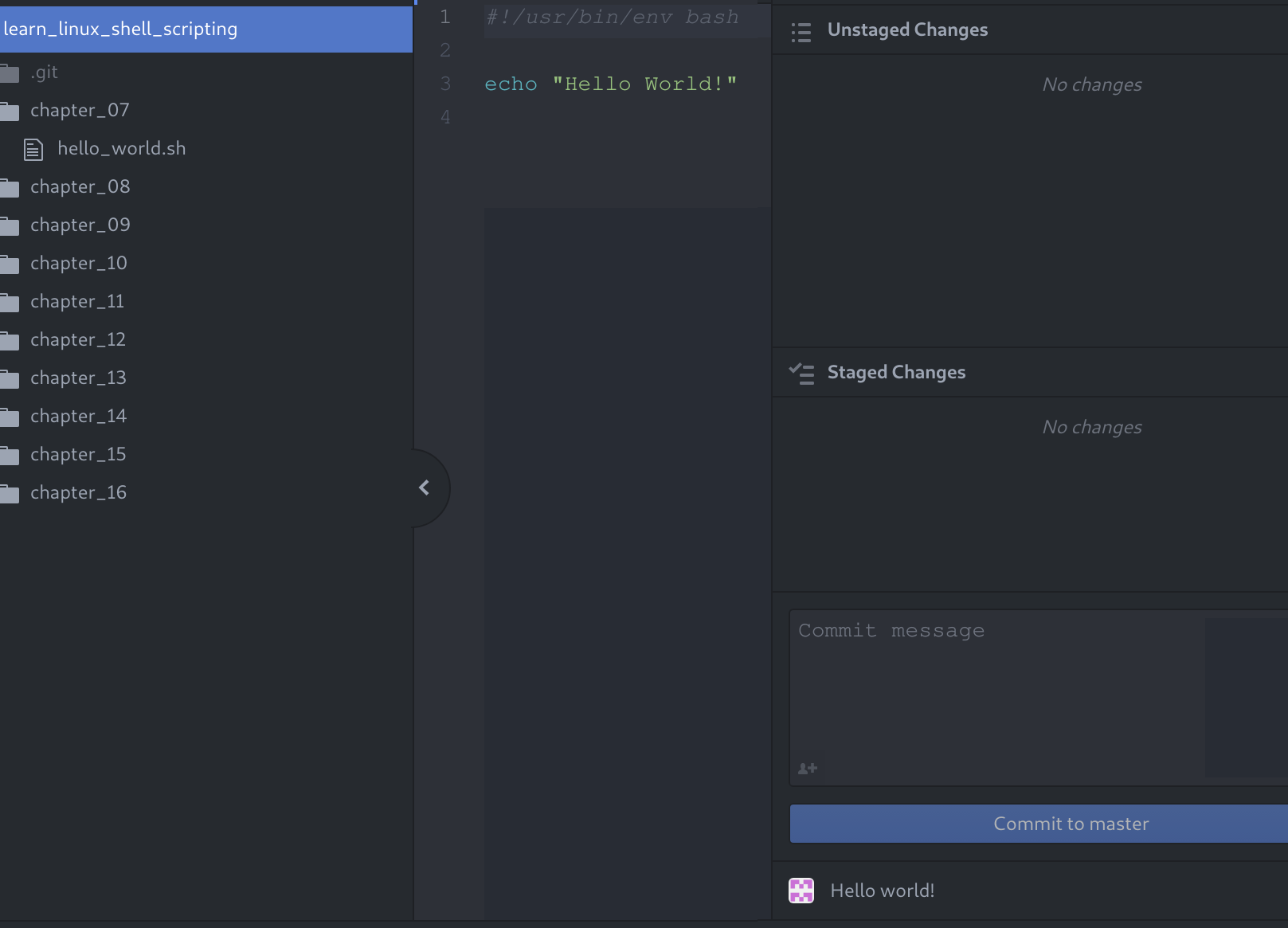

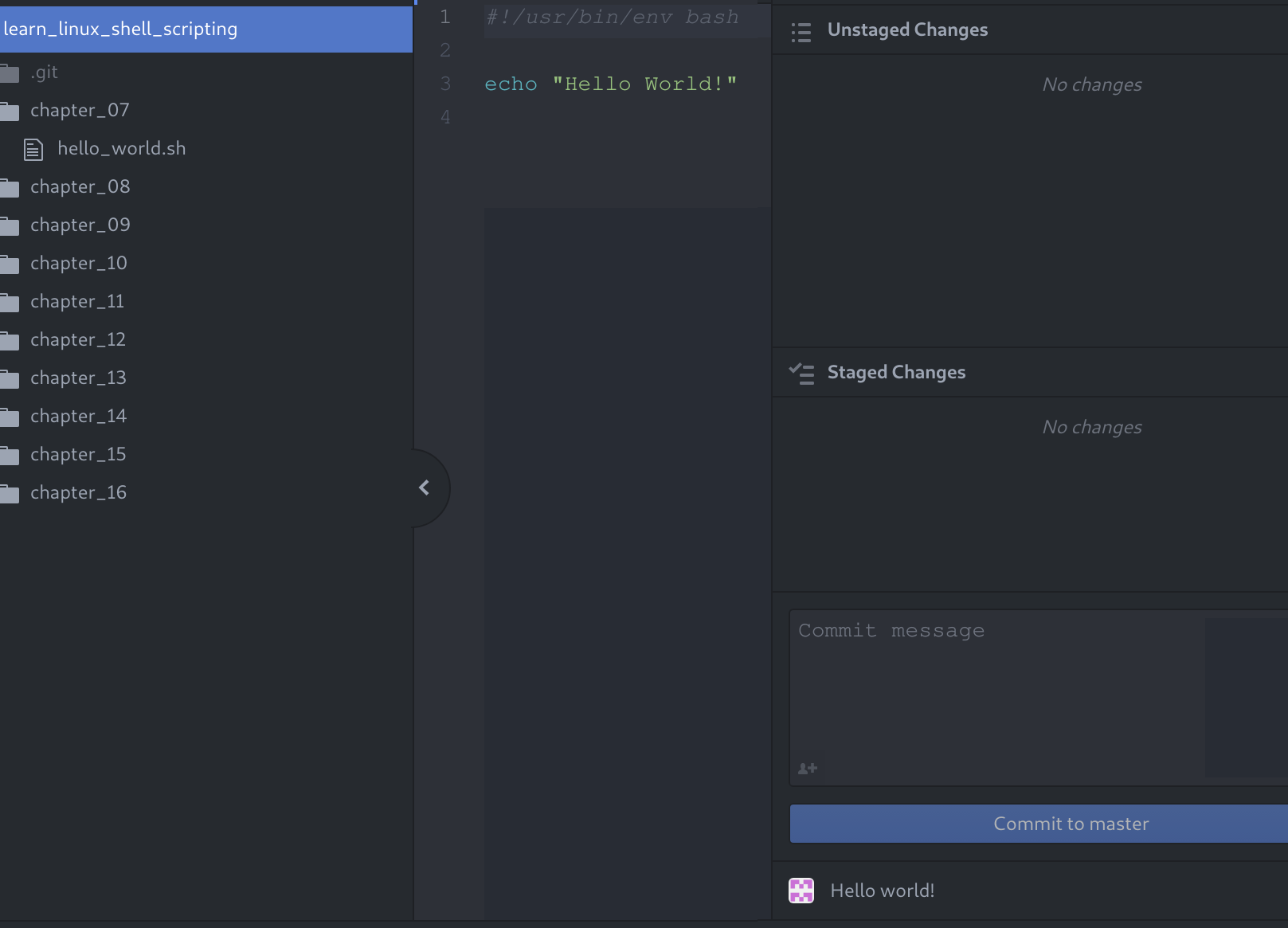

Finally, let's look at how Atom looks when you've got a Git project open and are working on files:

When working in Atom, the screen will mostly look like this. On the left-hand side, you'll see the Tree View, which you can toggle on/off by pressing Ctrl + \. The Tree View contains all the files in your current project (which is the directory you've opened). All these files can be opened by double-clicking them, which causes them to appear in the middle: the Editor View. This is where you'll spend most of your time, working on the shell scripts. The Editor View will always be visible, even if there are currently no files open.

By default, there is one last view, the Git View, located on the right-hand side. This view can be toggled by pressing Ctrl +Shift + 9. The code for this book is hosted on GitHub, which you will download (or, as Git calls it, clone) once, without the need to edit it on the remote server. Because of this, the Git View is not needed in this book, but we mention it since you will probably use it for other projects.

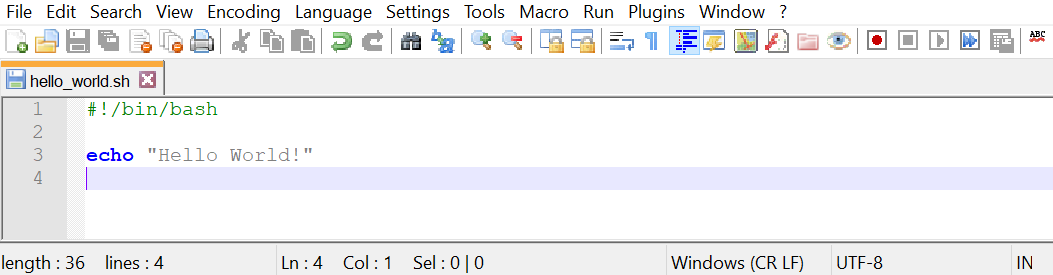

Where Atom is closer to an integrated development environment (IDE) than a text editor, Notepad++ is pretty much what the name implies: good old Notepad with some added features. Some of these added features include being able to have multiple files open at the same time, syntax highlighting, and limited autocomplete. It was initially released in 2003 and only works on Windows.

Notepad++ is characterized by its simplicity. If you are familiar with any kind of Notepad software (who isn't?), Notepad++ should be instantly recognizable. While we recommend using Atom for this book, using a simple solution such as Notepad++ will definitely not hold you back. However, in a business environment, you would almost always create scripts in an already existing version-controlled repository, which is where the added features of Atom really shine.

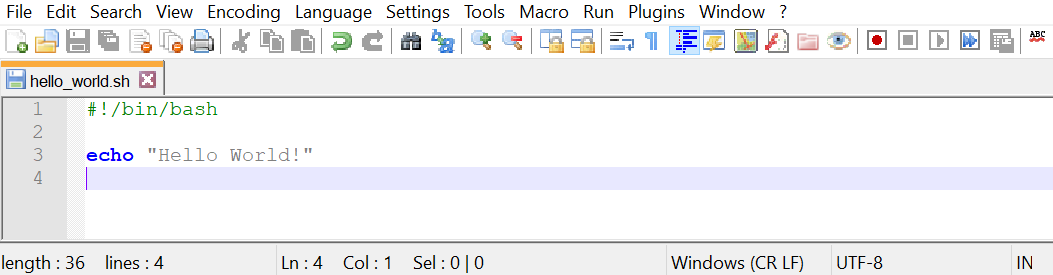

If you would like to check out Notepad++, grab it from https://notepad-plus-plus.org/download and run the installer (remember, only if you're on Windows!). Keep the default options and run Notepad++ after the installation. You should be greeted by the following screen:

As you can see, when you open a file ending in .sh, you will see syntax highlighting. This is because the .sh extension is reserved for shell script files. This can help you immensely when writing scripts. The example of a missing quote messing up your script will become really apparent with color-based syntax highlighting, possibly saving you many minutes of troubleshooting.

Notepad++ has many other features that make it a great enhanced Notepad. You can use macros to perform scripted tasks, you can install plugins to extend functionality, and there are many more unique features that make Notepad++ an attractive option.

Being able to use command-line editors is a skill anyone working with Linux should learn sooner or later. For Linux installations with a GUI, this might be substituted with a GUI tool such as Atom or the distribution's built-in variant on Notepad. However, server installations will almost never have a GUI and you will have to rely on command-line text editors. While this might sound daunting, it's really not! To give you a small introduction to command-line editors, we'll go over two of the most popular applications that are present on most Linux distributions: Vim and GNU nano.

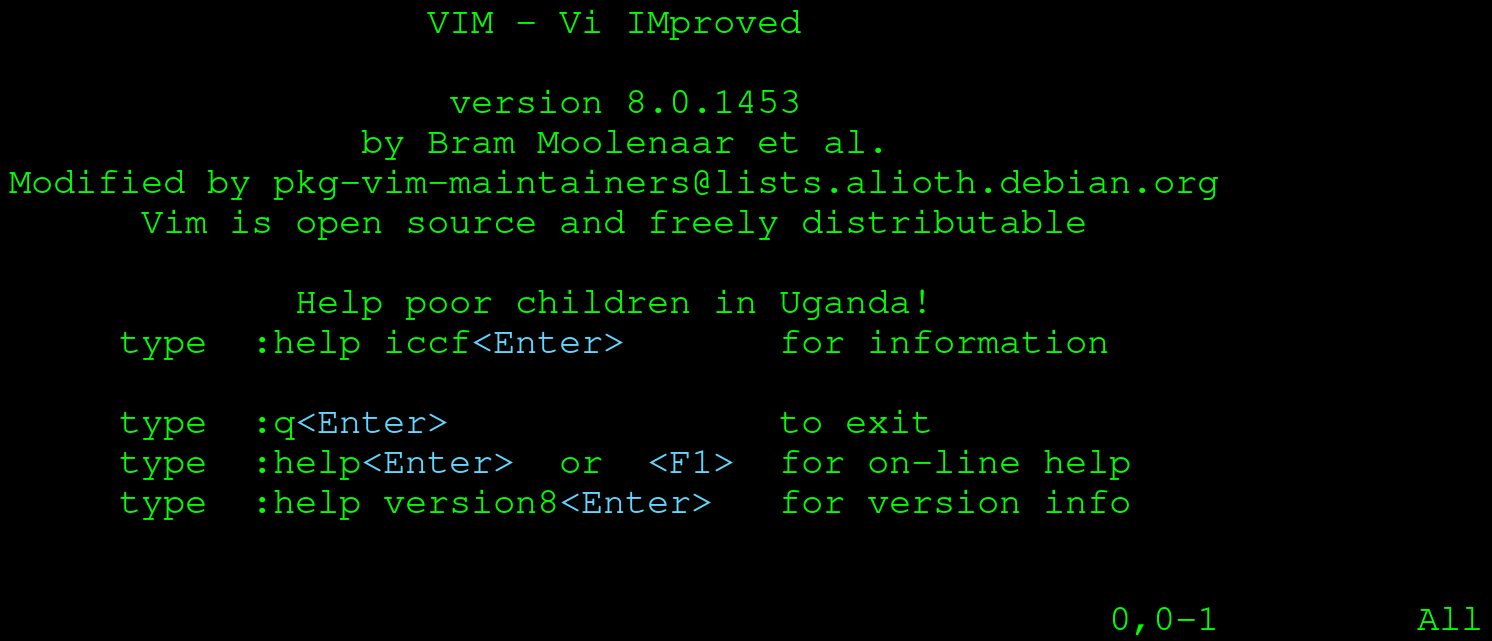

The first command-line text editor we will discuss is perhaps the most popular for Linux: Vim. Vim is derived from the term Vi Improved, as it is an updated clone of the Unix editor Vi. It was created and is still maintained by Bram Moolenaar, who first released Vim publicly in 1991. Vim (or, on very old systems, Vi) should be present on all Unix or Unix-like machines you will encounter.

Vim is considered a hard-to-learn tool. This is mainly caused by the fact it works very differently from text editors that most people are used to. However, once the initial learning curve is over, many agree that a lot of actions can be done in Vim much more quickly than in a normal text editor (such as Microsoft's Notepad++).

Let's jump in! Log in to your virtual machine:

$ ssh reader@localhost -p 2222

Once logged in, open Vim to an empty file:

$ vim

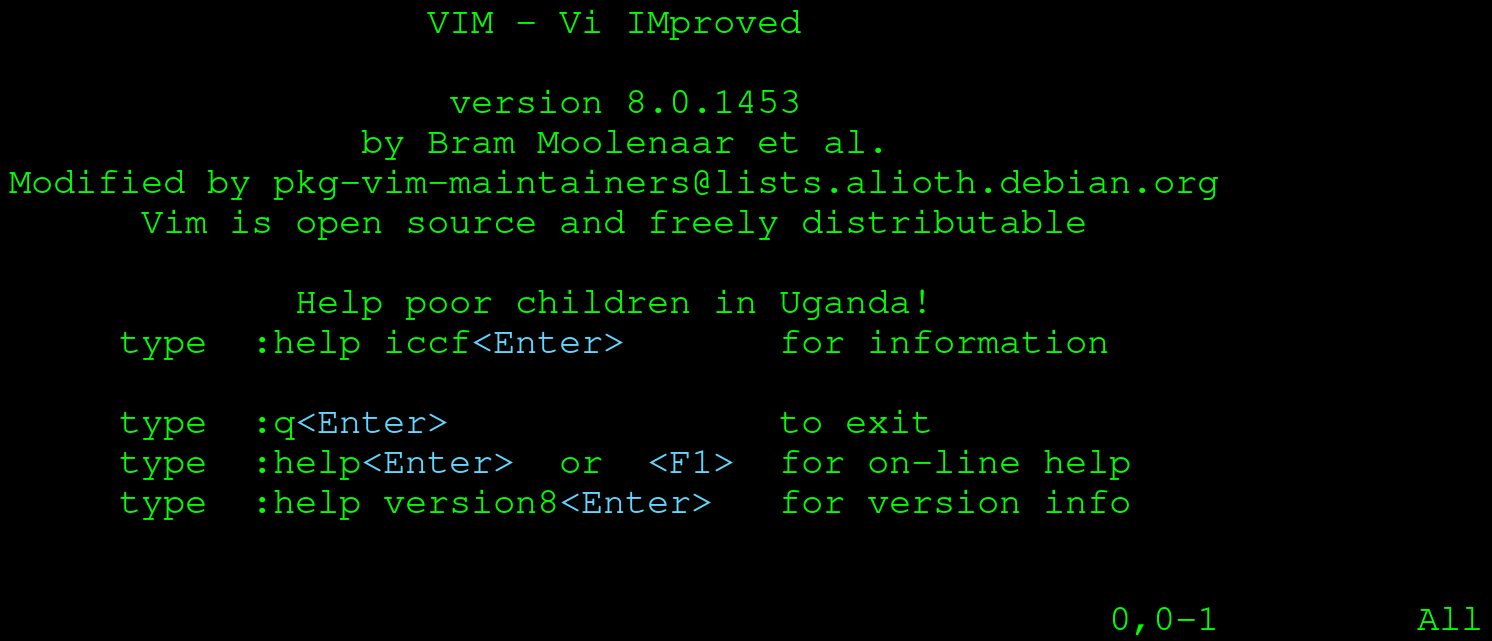

You should be greeted by something looking approximately like the following:

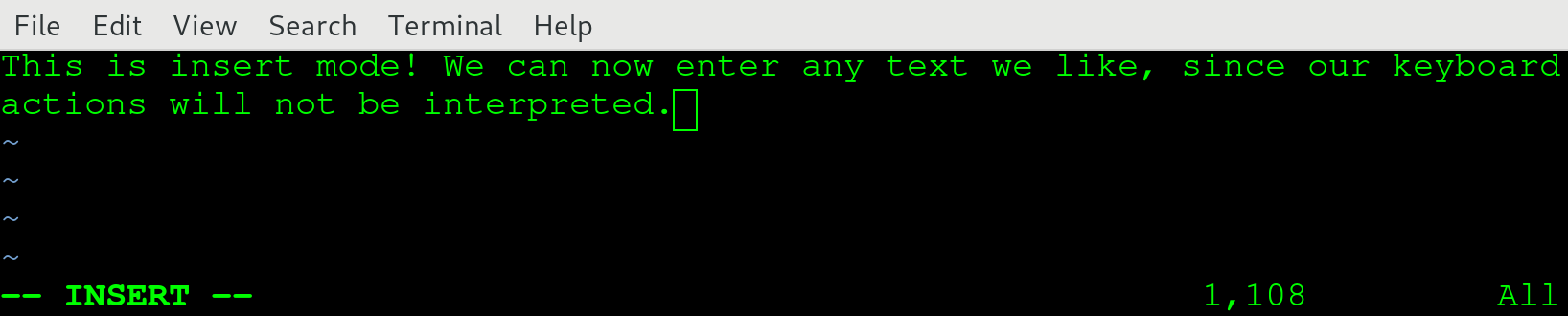

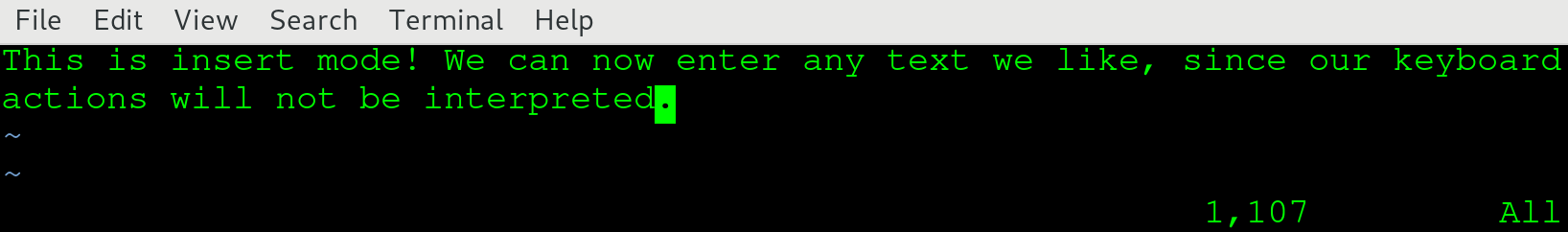

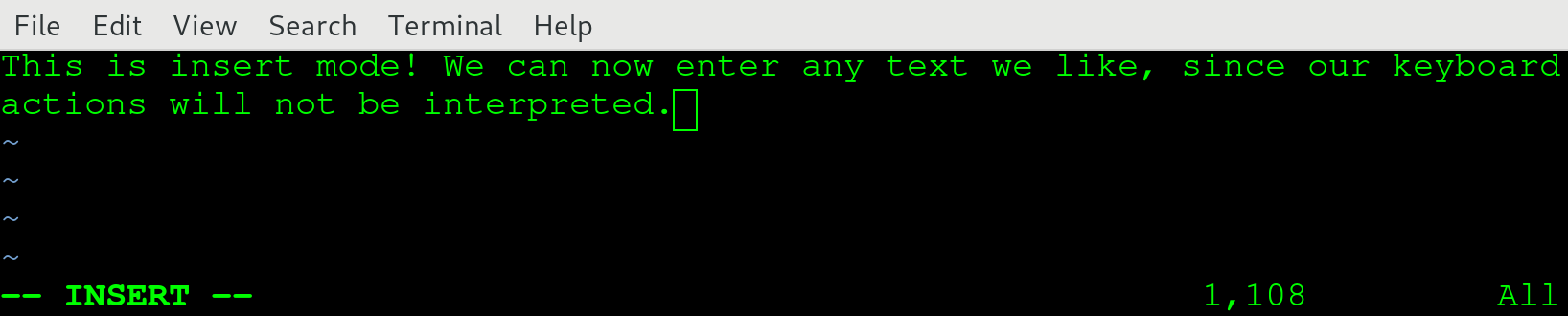

Vim starts a new process that uses your entire Terminal (don't worry, everything will still be right where you left it once you exit Vim!). When you start up Vim, you will be placed in normal mode. Vim has a number of modes, of which normal and insert are the most interesting to explore. In normal mode, you can't just start typing like you would in Notepad or Word. Since Vim was designed to be used without a mouse, it needed a way to manipulate text as well. Where some applications decided on using modifiers for this (holding the Shift key in Notepad for example), Vim decided on modes. Let's first enter insert mode so we can start to type some text. Press the I key, and your screen should switch to insert mode:

We've taken the liberty of typing some text while in insert mode. Be sure to do the same and when you're done, press Esc to go back to normal mode:

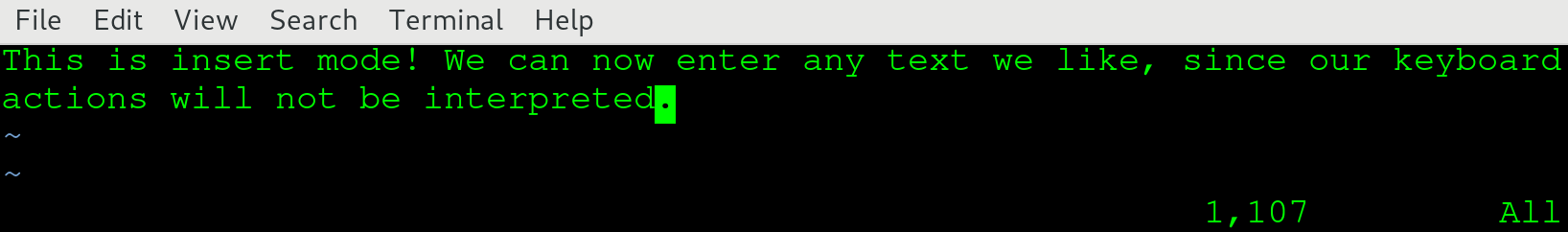

If you compare the two screenshots, you should a big difference: in the lower-left corner, the text -- INSERT -- is gone! When you're in a mode other than normal, that mode is clearly presented there. If you do not see anything, you can safely assume you're in normal mode. In normal mode, we can navigate using the arrow keys. We can also manipulate characters, words, and even (multiple) lines with a few key presses! For example, hit dd and notice that your whole line just got deleted. If you want to get it back, hit u for undo.

One challenge remains: exiting Vim. Normally, you might be tempted to use the Esc button to exit a program. If you're a little familiar with Linux, you might even know that a nice Ctrl + C will probably exit most programs as well. However, neither will work for Vim: Esc will just land you in normal mode, while Ctrl + C will not do anything. To quit Vim, make sure you are in normal mode and enter the following:

:q!

This exits your current document, without saving anything. If you want to save and exit, use the following:

:x filename.txt

This saves your current document as filename.txt and returns you to your Terminal. Note that normally you'll start Vim on an already existing file by using the following command:

$ vim filename.txt

In this case, you do not need to enter a filename when saving and exiting; using :x is enough in that case. :x is actually shorthand for :wq. :w is the write action, which you use to save a file, and :q is used to quit. Combined, they are used to save and quit. If you want to save your file at any other time during editing, you can just use :w to accomplish this.

Vim has many commands that power users appreciate. For now, remember that there are two important modes, normal and insert. You can go from normal to insert by pressing I, and you can go back to normal mode by pressing Esc. When in insert mode, Vim behaves just like Notepad or Word, but in normal mode you can perform easy text manipulation, for example deleting the whole line currently selected. If you want to exit Vim, go to normal mode and enter either :q! or :x, depending on whether you want to save the changes or not.

The .vimrc file can be used to set some persistent options for Vim. Using this file, you can customize your Vim experience. There are many possibilities for customization: popular examples include setting the color scheme, converting between tabs and spaces, and setting search options.

To create a .vimrc file that will be used when starting Vim, do the following:

$ cd

$ vim .vimrc

The first command places you in your home directory (don't worry, this will be explained in greater detail later in this book). The second starts a Vim editor for the .vimrc file. Don't forget the dot in front, as this is how Linux deals with hidden files (again, more on this later on). We're using the following configuration in our .vimrc file:

set expandtab

set tabstop=2

syntax on

colo peachpuff

set ignorecase

set smartcase

set number

In order, the following things are achieved with this configuration:

To get you started off with some great-to-know commands for Vim, we've incorporated a cheat sheet. After working through vimtutor, having this cheat sheet nearby almost guarantees you can properly use Vim!

Keystrokes are entered directly. Note that the keystrokes are case sensitive, so a is different from A. You can either hold Shift for the capital letters or use the Caps Lock key. However, the most practical approach would be to use Shift:

|

Keystroke |

Effect |

|

Esc |

Exit insert mode, go back to command mode. |

|

i |

Enter insert mode before the current location of the cursor. |

|

a |

Enter insert mode after the current location of the cursor. |

|

I |

Enter insert mode at the beginning of the current line. |

|

A |

Enter insert mode at the end of the current line. |

|

o |

Enter insert mode with a new line below the current line. |

|

O |

Enter insert mode with a new line above the current line. |

|

dd |

Delete the current line. |

|

u |

Undo the changes made in the previous insert mode. |

|

Ctrl + r |

Redo an undo. |

|

yy |

'Yank' the current line (=copy). |

|

p |

Paste the last yanked line below the current line. |

|

P |

Paste the last yanked line above the current line. |

|

H |

Navigate to the beginning of the file. |

|

M |

Navigate to the middle of the file. |

|

G |

Navigate to the end of the file. |

|

dH |

Delete all lines until the beginning of the file (including the current line). |

|

dG |

Delete all lines until the end of the file (including the current line). |

GNU nano, commonly referred to as just nano, is another command-line editor that is present by default on most Linux installations. As the name might suggest, it is part of the GNU project, no different than many other parts that make up a Linux distribution (remember, Bash is also GNU project software). Nano was first released in 1999, with the intention of replacing the Pico text editor, a simple text editor created for Unix systems.

Nano is much more than a What You See Is What You Get (WYSIWYG) tool, definitely when compared to Vim. Similar to Notepad and Word, nano does not use different modes; it's always ready to start typing your documents or scripts.

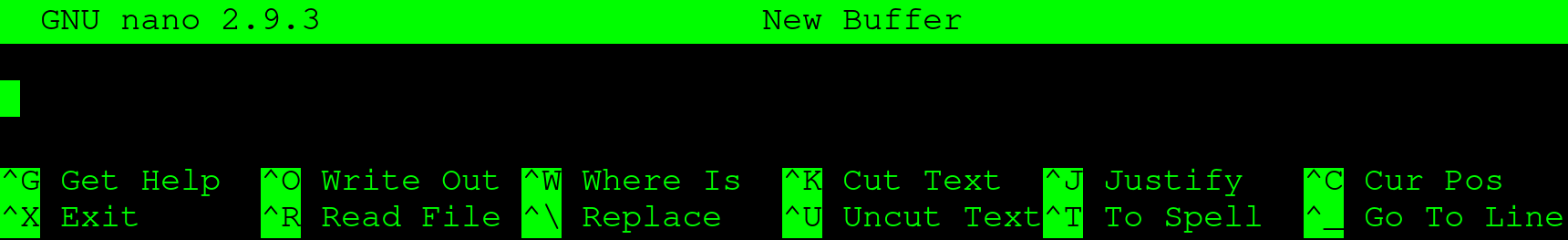

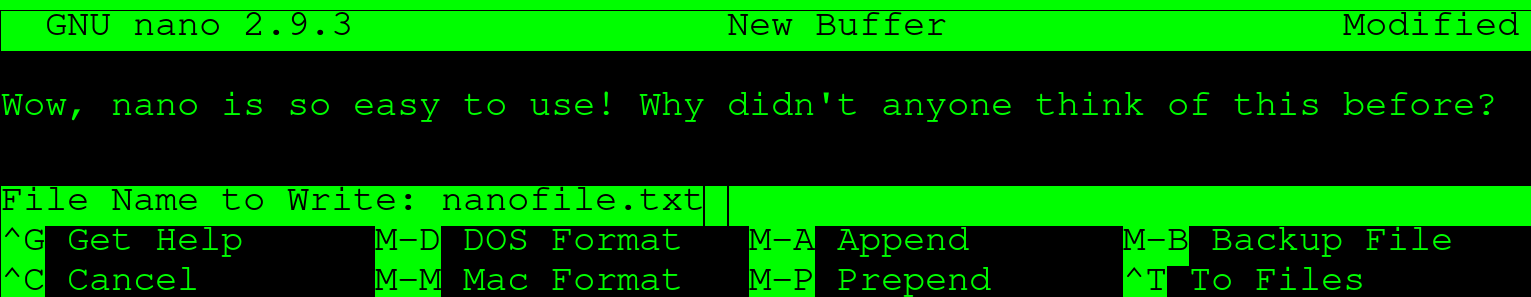

On your virtual machine, open a nano editor screen:

$ nano

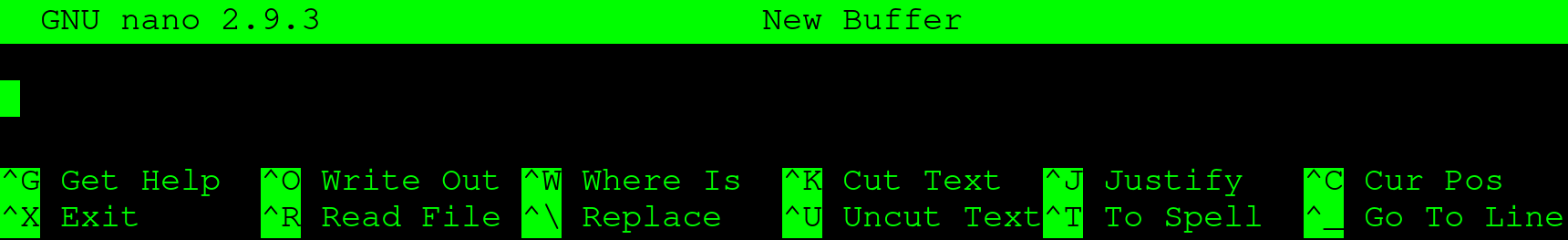

A screen similar to the following should come up:

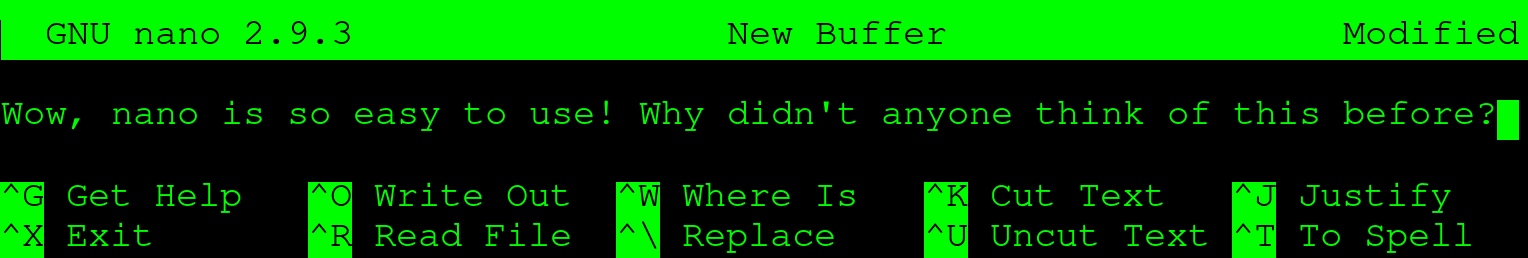

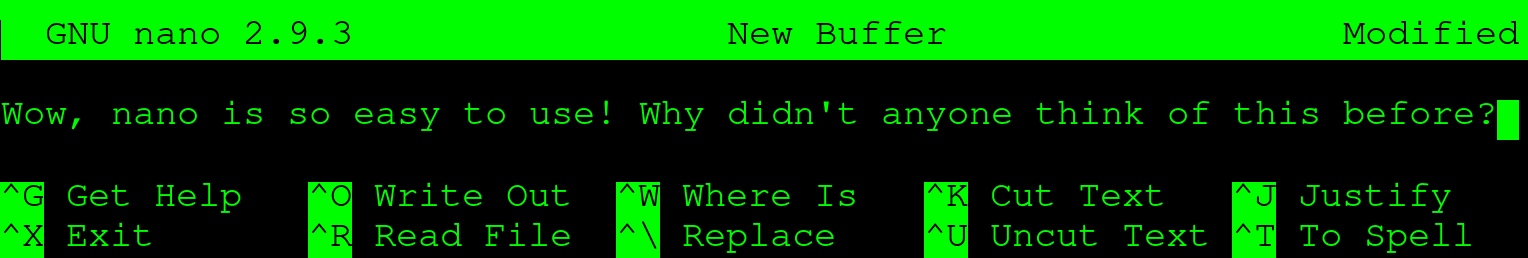

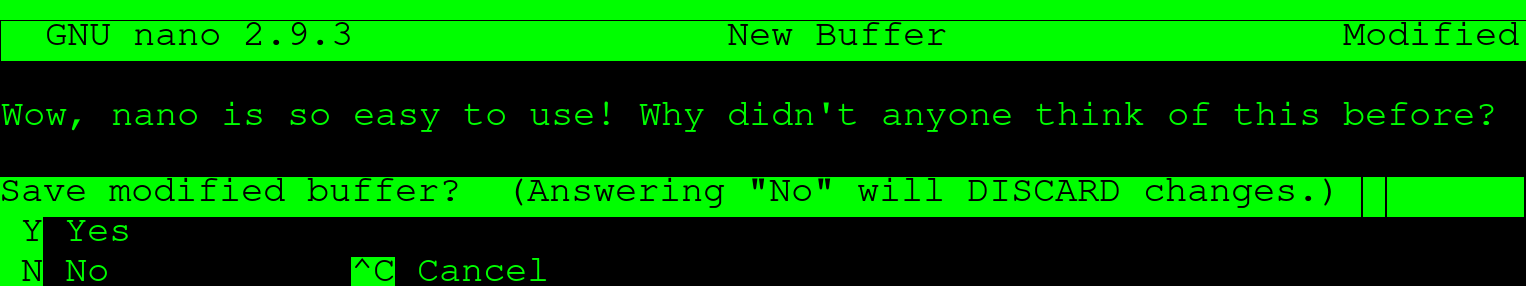

Feel free to start typing something. It should look something like the following:

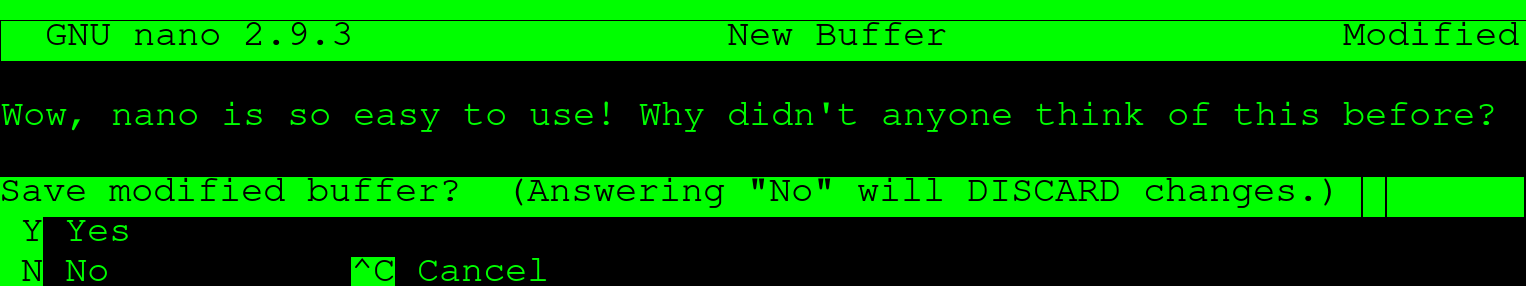

As you can see, the bottom of the screen is reserved for presenting what nano calls control keys. While it might not be obvious at first, the ^ is shorthand for Ctrl. If you want to exit, you hold down Ctrl and press X:

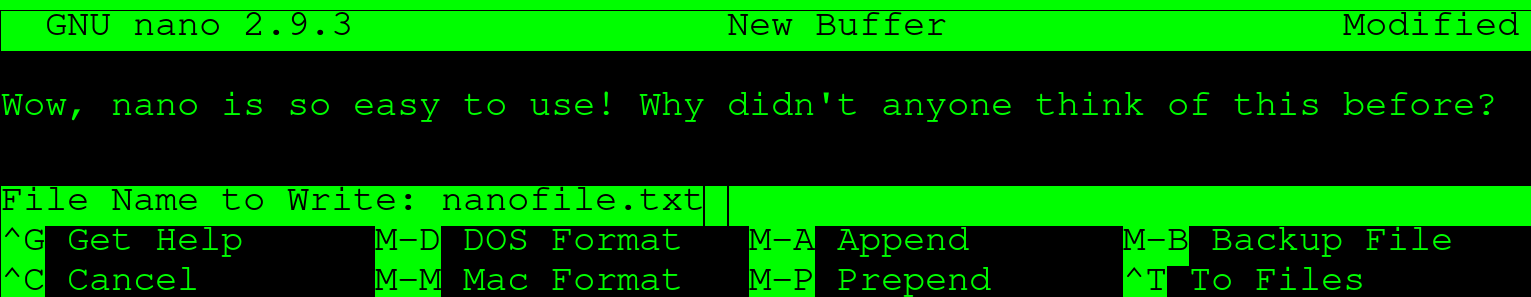

You will be prompted whether you'd like to exit with or without saving your file. In this case, we press Y for Yes. If we started nano with a filename, the save and exit would be completed right away, but because we started nano without a filename, another choice will be presented to us:

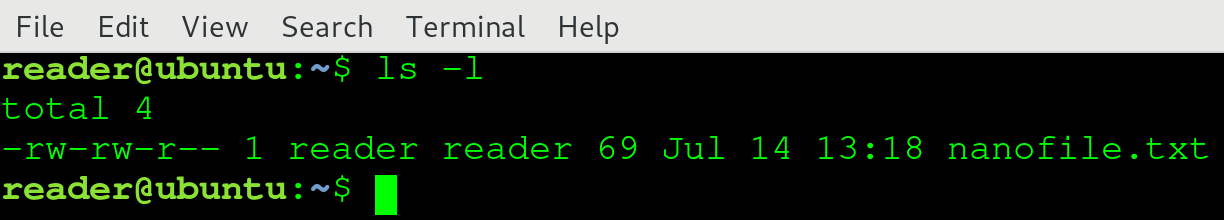

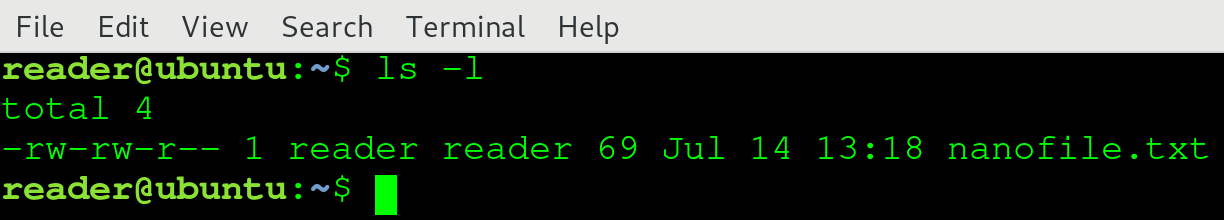

Enter a filename and press Enter. You will be back in your previous Terminal screen, in the directory where you started nano. If everything went well, you can see the file with the following command:

$ ls -l

While nano has more advanced features, for basic usage we have discussed the most important features. While it's initially easier to use than Vim, it's also not as powerful. Simply said, nano is simple, Vim is powerful.

If you do not have any experience and/or preference, our recommendation would be to spend a little bit of time learning Vim and stick with it. After spending more time with Linux and Bash scripting, the advanced features of Vim become hard to live without. However, if you can't get used to Vim, don't be ashamed to use nano: it's a fine editor that will get most jobs done without too much hassle!

To give you an impression of how we like to combine GUI tools with command-line editors, we've given the following example workflow. Don't worry about not understanding all steps yet; at the end of the book, you should come back to this example and understand exactly what we're talking about.

When you're writing shell scripts, you normally go through a few phases:

Phases 1 and 2 are often done without writing actual code. You think about the purpose of the script, how it could be implemented, and what is gained by creating the script. These steps often involve research and looking for best practices. When you feel like you have a good idea about why, what, and how you're going to write your shell script, you move on to phase 3: writing the script. At this point, you would open your favorite GUI-based editor and start typing away. Because the GUI editor has autocomplete, syntax highlighting, and other productivity features built in, you can efficiently write most of the shell script code. After you feel like your script is ready for testing, you need to move away from your GUI: the script has to be tested on the system it's been designed for.

Phase 4 begins. You copy and paste the script to the server, using either Vim or nano. Once the script is on the server, you run it. Most of the time, it will not actually do everything you expected it to do. Tiny mistakes are easy to make and easy to fix, but it would be a small hassle to go back to the GUI editor, change it, save it, transfer it to the server, and run it again! Luckily, we can use either Vim or nano to make minor changes to fix the script right there on the server and try again. A missing ; or " will make a shell script unusable, but it's fixed quickly (although errors like that are often highlighted in the GUI editors, so those are unlikely to make it onto the server, even for the first version).

Finally, after a number of iterations, your script will work as expected. Now you have to make sure the full and correct script is uploaded to your version control system. It's recommended to transfer the script from the GUI to the server one last time, to see whether you have applied all the changes you made on the server to your GUI session as well. Once that is done, commit it, and you're finished!

In this chapter, we discussed four text editing tools, divided into two types: GUI-based editors (Atom and Notepad++) and command-line editors (Vim and GNU nano), before showing how to use these tools together.

Atom is a powerful text editor that can be configured exactly how you want . By default, it has support for many different coding languages, including shell. It also comes with Git and GitHub integration. We also briefly discussed Notepad++. While not as powerful as Atom, it is also suitable for our purposes, as it is basically an enhanced Notepad with all the important features for shell scripting.

Vim and nano are the two most popular Linux command-line text editors. We have learned that while Vim is very powerful, it is also harder to learn than nano. However, learning how to properly use Vim will speed up many things you do on a Linux system and is a very valuable skill to have. For a great hands-on introduction to Vim, go through the vimtutor. Nano is much easier to use, as it more closely resembles the WYSIWYG editing style also found in Microsoft Word and Notepad.

We ended the chapter with an example of a shell scripting journey. We gave a brief overview of how to use GUI-based editors in combination with command-line editors.

The following commands were introduced in this chapter: vim, nano, and ls.

The following resource might be interesting if you'd like to go deeper into the subjects of this chapter:

In this chapter, we'll spend some time exploring the Linux filesystem. We will explain what a filesystem is and what makes the Linux filesystem unique. We will describe the structure of the Linux filesystem and how, under Linux, (almost) everything is a file. We will do this interactively, giving your the first closer look at some common Linux commands which will be used in scripting later on.

The following commands will be introduced in this chapter: pwd, cd, df, echo, type, cat, and less.

The following topics will be covered in this chapter:

We will explore the Linux filesystem using the virtual machine we created in Chapter 2, Setting Up Your Local Environment.

This chapter will present the basics of the Linux filesystem. Because filesystems are complicated, we will not be delving too deeply into the guts of the technology; instead, we'll present just enough information that's still relevant for shell scripting.

A filesystem is, in essence, the way data is stored and retrieved on a physical medium (which can be a hard disk, solid state drive, or even RAM). It is a software implementation that manages where and how the bits are written and found again, and may include various advanced features which enhance reliability, performance, and functionality.

The concept of a filesystem is abstract: there are many filesystem implementations, which are confusingly often referred to as filesystems. We find it easiest to grasp by ordering the filesystems in families, just as with Linux distributions: there are Linux filesystems, Windows filesystems, macOS filesystems, and many others. The Windows filesystem family spans from the earliest filesystem of FAT up until the newest ReFS, with the most widely used currently being NTFS.

At the time of writing, the most important filesystems in the Linux family are the following implementations:

The most commonly used Linux filesystem implementation is currently ext4. It is the fourth iteration in the extended file system (ext) series of Linux filesystems. It was released in 2008 and is considered very stable, but it is not state-of-the-art; reliability is the most important consideration.

XFS is most famously used in Red Hat distributions (Red Hat Enterprise Linux, CentOS, and Fedora). It contains some features that are more advanced than ext4, such as parallel I/O, larger file size support, and better handling of large files.

Finally, there is Btrfs. This filesystem implementation was initially designed at Oracle and is considered stable as of 2014. Btrfs has many advanced features that could make it preferable to ext4 and XFS; the principal developer of ext4 even stated that ext4 should eventually be replaced by Btrfs. The most interesting feature of Btrfs is that it uses the copy-on-write (COW) principle: files that are copied aren't actually written out to the physical medium fully, but only a new pointer to the same data is created. Only when either the copy or the original gets modified is new data written.

As you might have guessed, a filesystem implementation is nothing more than software. For Linux, the three implementations previously described are present in all newer Linux kernels. This means that, as long as the correct drivers are installed in the operating system, these can all be used. Even better, all of these can even be used concurrently! We will discuss this further later in this chapter.

Another interesting thing to note is that, while ext4 is native to Linux, with the help of drivers it can be used under, for example, Windows as well. You would not use ext4 as the filesystem for the primary drive under Windows, but you could mount a Linux-formatted ext4 filesystem under Windows and interact with the contents. The other way around, mounting a Windows filesystem under Linux, is also supported for most implementations. And while we used ext4 as the example here, the same goes for XFS and Btrfs.

As should be clear by now, in reality, there is no such thing as the Linux filesystem. However, these filesystems share certain characteristics that make them viable as Linux filesystems.

A Linux filesystem adheres to the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS). This FHS is maintained by The Linux Foundation and is currently up to version 3.0. As with many things in the Linux ecosystem, it is based on a Unix predecessor: the Unix Filesystem Standard (UFS). It specifies the directory structure and its contents. We'll explore this structure together in the next part of this chapter.

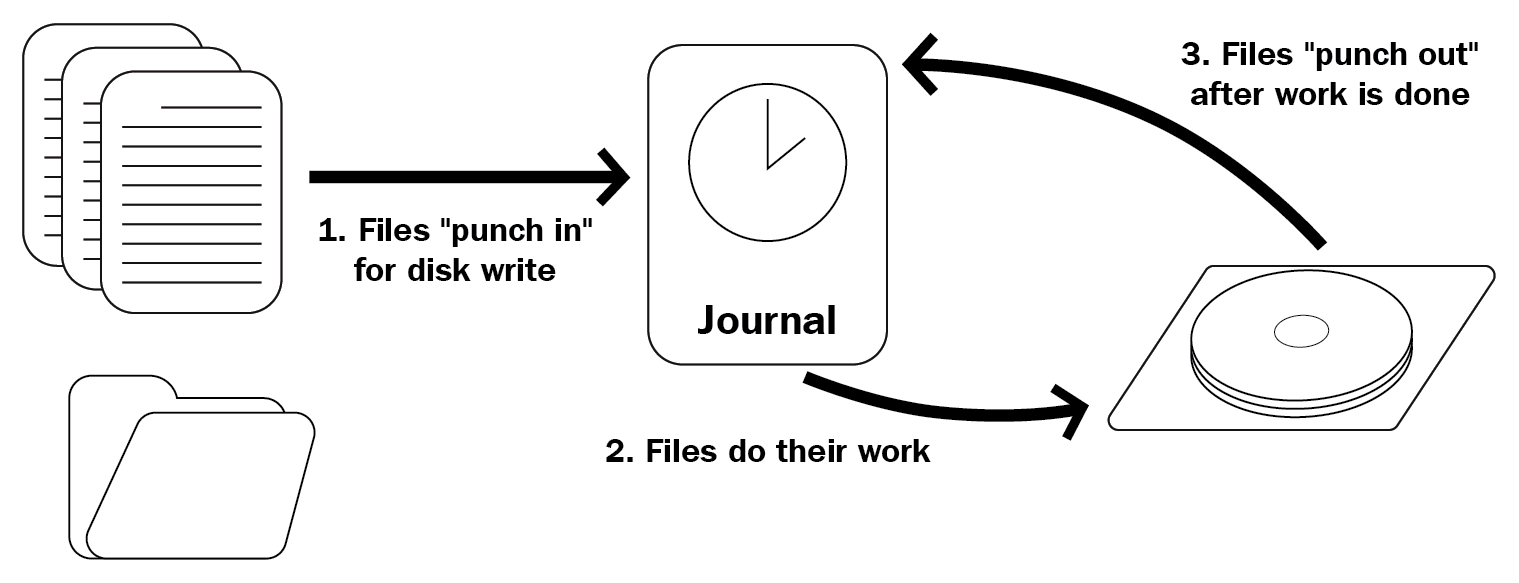

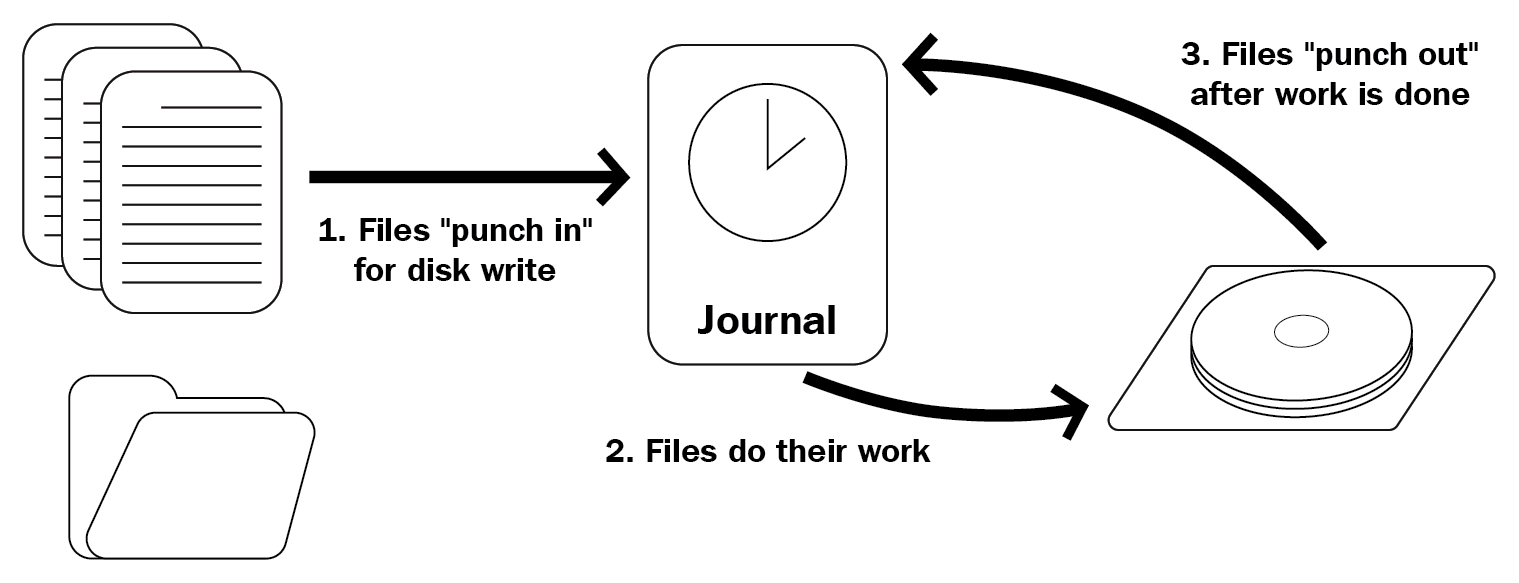

Since Linux is most commonly used in servers, Linux filesystem implementations (often) have very advanced features on the topic of file integrity and disaster recovery. An example of such a disaster would be a system experiencing a power outage when it was in the middle of writing a business-critical file. If the write operation was stored in memory and aborted halfway through, the file would be in an inconsistent state. When the system is brought up again, the operating system does not have the write operation in memory anymore (since memory is cleared on each reboot), and only a part of the file will be written. Obviously, this is unwanted behavior and can lead to problems. Because of the properties of COW, Btrfs does not have this problem. However, ext4 and XFS are not COW filesystems. They both handle this issue in another way: with journaling:

As the preceding diagram shows, files are written to disk in three steps:

If the server crashes between steps 2 and 3, the write will be done again after power up, because the journal still contains the entry. The journal only contains some metadata about the operation, not the entire file. Since the journal contains a reference to the actual location on disk (the drive sectors), it will overwrite what was previously written, in this case, part of the file. If it finished successfully this time, the journal entry will be removed and the state of the file/disk is guaranteed. Should the server fail between steps 1 and 2, the actual instruction to write to disk has never been given and the software giving the instruction should account for that possibility.

While there are many more advanced filesystem features that are very interesting, we want to focus on what makes the Linux filesystem distinctively Linux: the filesystem structure. If you're used to Windows, this will probably be the single most confusing difference between the two operating systems. If you're coming from macOS, the difference is still noticeable, but much smaller: this is a result of macOS being a Unix operating system, which has obvious similarities with the Unix-like Linux structure.

We're going to be interactively exploring the Linux filesystem from this point on. We advise you to follow along with the code examples that follow, since this increases information retention significantly. Besides that, your system might look differently from the one we use, should you have chosen not to use Ubuntu 18.04 LTS for this book. In any case, start up that virtual machine and start exploring with us!

Let's start by logging in to our virtual machine via SSH:

ssh -p 2222 reader@localhost

Enter your password at the prompt and you should arrive at the default Ubuntu 18.04 login banner, which should look similar to the following:

reader@localhost's password:

Welcome to Ubuntu 18.04.1 LTS (GNU/Linux 4.15.0-29-generic x86_64)

<SNIPPED>

System information as of Sat Jul 28 14:15:19 UTC 2018

System load: 0.09 Processes: 87

Usage of /: 45.6% of 9.78GB Users logged in: 0

Memory usage: 15% IP address for enp0s3: 10.0.2.15

Swap usage: 0%

<SNIPPED>

Last login: Sat Jul 28 14:13:42 2018 from 10.0.2.2

reader@ubuntu:~$

When logging in (either via SSH or the Terminal console) you will end up at the home directory of the user. You can always find out where you are exactly by using the pwd command. pwd stands for print working directory:

reader@ubuntu:~$ pwd

/home/reader

So, we've ended up in the /home/reader/ directory. This is the default for most Linux distributions: /home/$USERNAME/. Since we created the primary user reader, this is where we expect to be. For those of you coming from Windows, this might look very foreign: where is the drive name (C:, D:, and so on) and why are we using (forward) slashes instead of backslashes?

Linux, as well as Unix and other Unix-like systems, uses a tree structure. It is referred to as a tree because it starts at a single origin point, the root (found at /). Directories are nested from there (like branches from a tree), not much differently from other operating systems. Finally, the tree structure ends in files that are considered the leaves of the tree. This might sound terribly complicated still, but it's actually relatively simple. Let's keep exploring to make sure we fully understand this structure! Under Linux, we use the cd command to change directories. It works by entering cd, followed by the location on the filesystem where we want to go as the argument to the command. Navigate to the filesystem root:

reader@ubuntu:~$ cd /

reader@ubuntu:/$

As you can see, nothing much seems to have happened. However, there is one tiny difference in your Terminal prompt: the ~ character has been replaced by /. Under Ubuntu, the default configuration shows the location on the filesystem without needing to use the pwd command. The prompt is built as follows: <username>@<hostname>:<location>$. Why the ~ then? Simple: the tilde character is shorthand for the user's home directory! If the shorthand wasn't there, the prompt at login would be reader@ubuntu:/home/reader$.

Since we have navigated to the root of the filesystem, let's check out what we can find there. To list the contents of the current directory, we use the ls command:

reader@ubuntu:/$ ls

bin dev home initrd.img.old lib64 media opt root sbin srv sys usr vmlinuz

boot etc initrd.img lib lost+found mnt proc run snap swap.img tmp var vmlinuz.old

If you're using SSH, you'll most likely have some colors to differentiate between files and directories (and even permissions on directories, if you see tmp in a different manner; this will be discussed in the next chapter). However, even with color assistance, this still feels unclear. Let's clean it up a bit by using an option on the ls command:

reader@ubuntu:/$ ls -l

total 2017372

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Jul 28 10:31 bin

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Jul 28 10:32 boot

drwxr-xr-x 19 root root 3900 Jul 28 10:31 dev

drwxr-xr-x 90 root root 4096 Jul 28 10:32 etc

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Jun 30 18:20 home

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 33 Jul 27 11:39 initrd.img -> boot/initrd.img-4.15.0-29-generic

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 33 Jul 27 11:39 initrd.img.old -> boot/initrd.img-4.15.0-23-generic

drwxr-xr-x 22 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:09 lib

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 lib64

drwx------ 2 root root 16384 Jun 30 17:58 lost+found

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 media

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 mnt

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 opt

dr-xr-xr-x 97 root root 0 Jul 28 10:30 proc

drwx------ 3 root root 4096 Jul 1 09:40 root

drwxr-xr-x 26 root root 920 Jul 28 14:15 run

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 12288 Jul 28 10:31 sbin

drwxr-xr-x 4 root root 4096 Jun 30 18:20 snap

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 srv

-rw------- 1 root root 2065694720 Jun 30 18:00 swap.img

dr-xr-xr-x 13 root root 0 Jul 28 10:30 sys

drwxrwxrwt 9 root root 4096 Jul 28 14:32 tmp

drwxr-xr-x 10 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:07 usr

drwxr-xr-x 13 root root 4096 Apr 26 19:10 var

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 30 Jul 27 11:39 vmlinuz -> boot/vmlinuz-4.15.0-29-generic

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 30 Jul 27 11:39 vmlinuz.old -> boot/vmlinuz-4.15.0-23-generic

The option -l (hyphen lowercase l, as in long) to ls gives the long listing format. Among other things, this prints the permissions, the owner of the file/directory, the type of file, and its size. Remember, permissions and ownership are discussed in the next chapter, so no need to worry about this for now. The most important thing to take away from this is that each file/directory is printed on its own line, where the first character of that line denotes the type of file: d for directory, - for regular file, and l for symlinks (which are shortcuts under Linux).

Let's navigate deeper into the tree structure, back toward our home directory. At this point, you have two options. You can use a relative path (as in: relative to the current location) or a fully qualified path (which is not relative to the current directory). Let's try both:

reader@ubuntu:/$ cd home

reader@ubuntu:/home$

The preceding is an example of changing directories into a relative directory. We were positioned in the root directory, /, and we navigated to home from there, effectively ending up in /home. We could have navigated there from anywhere by using the fully qualified path:

reader@ubuntu:/$ cd /home

reader@ubuntu:/home$

Did you spot the difference? In the fully qualified example, the argument to cd started with a slash, but in the relative example it did not. Let's see what happens if you use both types incorrectly:

reader@ubuntu:/home$ ls

reader

reader@ubuntu:/home$ cd /reader

-bash: cd: /reader: No such file or directory

We listed the contents of the /home directory with ls. As expected, we saw (at least) the current user's home directory, reader. However, when we tried to navigate to it using cd /reader, we got the infamous error No such file or directory. This is not surprising though: there isn't actually a directory /reader. The directory we're looking for is /home/reader, which would be reached fully qualified with the command cd /home/reader:

reader@ubuntu:/home$ cd home

-bash: cd: home: No such file or directory

reader@ubuntu:/home$

The same error is presented if we try to use an incorrect relative path. In the preceding example, we are currently located in the /home directory and we use the cd home command. Effectively, this would put us in /home/home, which, as we saw when we used ls in the /home directory, does not exist!

Even though fully qualified is safer, it's much less efficient then relative. You saw how we can move deeper into the branches of the tree structure, but what if you had to go down a level, back toward the root? Luckily for us, that does not force us to use fully qualified paths. We can use the .. notation, which means as much as go up a level toward /:

reader@ubuntu:/home$ cd ..

reader@ubuntu:/$

Using cd .. to move up lands us back at the root of the filesystem. At this point, you might think If I do this again while I'm on the highest level of the filesystem, what would happen?. Give it a try:

reader@ubuntu:/$ cd ..

reader@ubuntu:/$

Fortunately for us, we do not get an error nor a crashing machine; instead, we just end up (or, depending on how you look at it, stay) on the root of the filesystem.

Now that we've got the basics of moving around using cd and listing directory contents using ls under control, let's start exploring other parts of the filesystem. Let's begin with an overview of every directory directly under the root filesystem, as specified by the FHS:

|

Location |

Purpose |

|

/bin/ |

Contains essential binaries (=tools) used by normal users |

|

/boot/ |

Contains files used in the boot process: kernel, initramfs, bootloader |

|

/dev/ |

Contains special files used to access devices |

|

/etc/ |

Default location for software configuration files |

|

/home/ |

Contains the home directories for normal users |

|

/lib/ |

Contains system libraries |

|

/lib64/ |

Contains 64bit system libraries |

|

/media/ |

Removable devices such as USB and DVDs can be found here |

|

/mnt/ |

Empty by default, can be used to mount other filesystems |

|

/opt/ |

Directory where optional software can be installed |

|

/proc/ |

Directory where information about processes is stored |

|

/root/ |

The home directory of the root user |

|

/run/ |

Contains variable data about run-time data, different each boot |

|

/sbin/ |

Contains essential sytem binaries (=tools) used by administrative users |

|

/srv/ |

Directory to place data to be served by the server |

|

/sys/ |

Contains information about the system, such as drivers and kernel features |

|

/tmp/ |

Directory intended for temporary files, often cleared on reboot (because it is stored in RAM, instead of on disk) |

|

/usr/ |

Contains non-essential files and binaries as read-only user data |

|

/var/ |

Contains variable files, such as logs |

While each and every top-level directory has an important function, there are a few we're going to examine more closely since we're undoubtedly going to encounter them in our shell scripting. These are /bin/, /sbin/, /usr/, /etc/, /opt/, /tmp/, and /var/.

But first, we'd like to briefly address something you might have found confusing, especially if you're coming from a Windows background where you're used to multiple disks/partitions in the form of C:\, D:\, E:\, and so on. With the preceding directory structure, and the information that the highest point in the filesystem is at /, how does Linux deal with multiple disks/partitions?

The answer is actually pretty simple. Linux mounts filesystems somewhere within the tree structure. The first mount is found on the primary partition we have already covered: it is mounted on /! Let's see how this looks while we check out a new df tool:

reader@ubuntu:~$ df -hT

Filesystem Type Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

udev devtmpfs 464M 0 464M 0% /dev

tmpfs tmpfs 99M 920K 98M 1% /run

/dev/sda2 ext4 9.8G 4.4G 5.0G 47% /

tmpfs tmpfs 493M 0 493M 0% /dev/shm

tmpfs tmpfs 5.0M 0 5.0M 0% /run/lock

tmpfs tmpfs 493M 0 493M 0% /sys/fs/cgroup

/dev/loop0 squashfs 87M 87M 0 100% /snap/core/4917

/dev/loop1 squashfs 87M 87M 0 100% /snap/core/4486

/dev/loop2 squashfs 87M 87M 0 100% /snap/core/4830

tmpfs tmpfs 99M 0 99M 0% /run/user/1000

While this is a lot of output by df (which reports filesystem disk space usage), the most interesting was highlighted previously: the partition /dev/sda2 of type ext4 (remember?) is mounted on /. You're getting a preview of the everything is a file later in this chapter: /dev/sda2 is handled as a file, but it is actually a reference to a partition on the disk (which is, in this case, a virtual disk). Another example from our Arch Linux host gives even more information (don't worry if you don't have a Linux host, we'll explain later):

[root@caladan ~]# df -hT

Filesystem Type Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

dev devtmpfs 7.8G 0 7.8G 0% /dev

run tmpfs 7.8G 1.5M 7.8G 1% /run

/dev/mapper/vg_caladan-lv_arch_root ext4 50G 29G 19G 60% /

tmpfs tmpfs 7.8G 287M 7.5G 4% /dev/shm

tmpfs tmpfs 7.8G 0 7.8G 0% /sys/fs/cgroup

tmpfs tmpfs 7.8G 212K 7.8G 1% /tmp

/dev/sda1 vfat 550M 97M 453M 18% /boot

tmpfs tmpfs 1.6G 16K 1.6G 1% /run/user/120

tmpfs tmpfs 1.6G 14M 1.6G 1% /run/user/1000

/dev/sdc1 vfat 15G 552M 14G 4% /run/media/tammert/ARCH_201803

/dev/mapper/vg_caladan-lv_data btrfs 10G 17M 9.8G 1% /data

You can see I have an ext4 filesystem mounted as my root. However, I also have an extra btrfs partition mounted on /data/ and a vfat boot partition (which is needed on bare-metal installations, but not on virtual machines) on /boot/. To top it off, there's also a vfat USB device with the Arch Linux installer connected, which was automatically mounted under /run/media/. So not only does Linux handle multiple partitions or disks gracefully, even different types of filesystems can be used side by side under the same tree structure!

Let's get back to top-level directories. We'll discuss /bin/, /sbin/, and /usr/ first, because they are really similar. As stated in the overview, all of these directories contain binaries used by normal users and administrators of the system. Let's see where those binaries are and how our user session knows how to find them in the process. We'll manage this by using the echo command. Its short description is simply display a line of text. Let's see how it works:

reader@ubuntu:~$ echo

reader@ubuntu:~$ echo 'Hello'

Hello

reader@ubuntu:~$

If we use echo without passing an argument, an empty line of text is displayed (pretty much just as promised by the short description!). If we pass text, which we enclose in single quotes, that text is printed instead. In this context, a bit of text which contains either letters, numbers, or other characters is referred to as a string. So, any string we pass to echo will be printed in our Terminal. While this might not seem that interesting, it is interesting when you start to consider variables. A variable is a string which value is, as the name implies, variable from time to time. Let's use echo to print the current value of the variable BASH_VERSION:

reader@ubuntu:~$ echo BASH_VERSION

BASH_VERSION

reader@ubuntu:~$ echo $BASH_VERSION

4.4.19(1)-release

reader@ubuntu:~$

You should notice we did not use the echo BASH_VERSION command, since that would print the literal text BASH_VERSION, but we instead started the variable name with a $. In Bash, the $ denotes the fact that we're using a variable (we will explain variables and variable interpolation further in Chapter 8, Variables and User Input). Why are we telling you this? Because the binaries we can use from our Terminal are found by using a variable, specifically the PATH variable:

reader@ubuntu:~$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin <SNIPPED>

reader@ubuntu:~$

As you can see here, binaries need to be in the /usr/local/sbin/, /usr/local/bin/, /usr/sbin/, /usr/bin/, /sbin/, or /bin/ directory for us to be able to use them (with the current value of PATH, which we can change, but that's out of scope for now). That would mean that binaries we've been using up until now (cd, ls, pwd, and echo) would need to be in one of these directories so that we can use them, right? Unfortunately, this is where things get slightly complicated. On Linux, we basically use two types of binaries: those that are found on disk (in a directory as specified by the PATH variable), or they can be built into the shell we're using, then called a shell builtin. A good example is actually the echo command we just learned, which is both! We can see what type of command we're dealing with by using type:

reader@ubuntu:~$ type -a echo

echo is a shell builtin

echo is /bin/echo

reader@ubuntu:~$ type -a cd

cd is a shell builtin

reader@ubuntu:~$

If a command is both built-in and a binary within the PATH, the binary is used. If it is only present as a built-in, such as cd, the built-in is used. As a general rule, most commands you use will be binaries on disk, as found in your PATH. Furthermore, most of these will be present in the /usr/bin/ directory (on our Ubuntu virtual machine, more than half of the total binaries are present in /usr/bin/!).

So, the overall goal of the binary directories should be clear: to provide us with the tools we need to perform our work. The question remains, why are there (at least) six different directories, and why are they divided between bin and sbin? The answer to the last part of the question is easy: bin has normal utilities used by users, while sbin has utilities used by system administrators. In that last category, tools related to disk maintenance, network configuration, and firewalling, for example, are found. The bin directories contain utilities that are used for filesystem operations (such as creating and removing files/directories), archiving, and listing information about the system, among others.

The difference between the top-level /(s)bin/ and /usr/(s)bin/ is a bit more vague. In general, the rule is that essential tools are found in /(s)bin, while system-specific binaries are placed in the /usr/(s)bin directories. So if you installed a package to run a web server, it would be placed in either /usr/bin/ or /usr/sbin/, since it is system-specific. Finally, the /usr/local/(s)bin/ directories are, in our experience, most often used for binaries that are installed manually, instead of from a package manager. But you could place them in either directory of the PATH to work; it's mostly a matter of convention.

As a final note, /usr/ contains more than just binaries. Among these are some libraries (which have the same relation to the /lib/ and /lib64/ top-level directories) and some miscellaneous files. If you're curious, we would definitely recommend checking out the rest of the /usr/ directory using cd and ls, but the most important thing to remember is that binaries and libraries can be located here.

On to the next interesting top-level directory within the Linux filesystem: the /etc/ directory. Pronounced et-c as in et-cetera, it is used to store configuration files for both system software as well as user software. Let's see what it contains:

reader@ubuntu:/etc# ls

acpi console-setup ethertypes inputrc logrotate.conf network python3 shadow ucf.conf

...<SNIPPED>: