Chapter 17. Support Vector Machines

17.0 Introduction

To understand support vector machines, we must understand hyperplanes. Formally, a hyperplane is an n – 1 subspace in an n-dimensional space. While that sounds complex, it actually is pretty simple. For example, if we wanted to divide a two-dimensional space, we’d use a one-dimensional hyperplane (i.e., a line). If we wanted to divide a three-dimensional space, we’d use a two-dimensional hyperplane (i.e., a flat piece of paper or a bed sheet). A hyperplane is simply a generalization of that concept into n dimensions.

Support vector machines classify data by finding the hyperplane that maximizes the margin between the classes in the training data. In a two-dimensional example with two classes, we can think of a hyperplane as the widest straight “band” (i.e., line with margins) that separates the two classes.

In this chapter, we cover training support vector machines in a variety of situations and dive under the hood to look at how we can extend the approach to tackle common problems.

17.1 Training a Linear Classifier

Solution

Use a support vector classifier (SVC) to find the hyperplane that maximizes the margins between the classes:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.svmimportLinearSVCfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScalerimportnumpyasnp# Load data with only two classes and two featuresiris=datasets.load_iris()features=iris.data[:100,:2]target=iris.target[:100]# Standardize featuresscaler=StandardScaler()features_standardized=scaler.fit_transform(features)# Create support vector classifiersvc=LinearSVC(C=1.0)# Train modelmodel=svc.fit(features_standardized,target)

Discussion

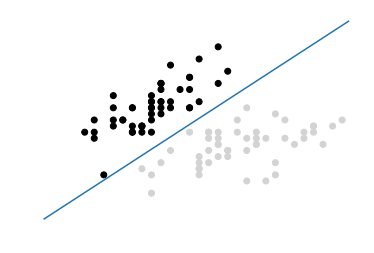

scikit-learn’s LinearSVC implements a simple SVC. To get an intuition

behind what an SVC is doing, let us plot out the data and hyperplane.

While SVCs work well in high dimensions, in our solution we only loaded

two features and took a subset of observations so that the data contains

only two classes. This will let us visualize the model. Recall that SVC

attempts to find the hyperplane—a line when we only have two

dimensions—with the maximum margin between the classes. In the following code we plot the two classes on a two-dimensional space, then draw the

hyperplane:

# Load libraryfrommatplotlibimportpyplotasplt# Plot data points and color using their classcolor=["black"ifc==0else"lightgrey"forcintarget]plt.scatter(features_standardized[:,0],features_standardized[:,1],c=color)# Create the hyperplanew=svc.coef_[0]a=-w[0]/w[1]xx=np.linspace(-2.5,2.5)yy=a*xx-(svc.intercept_[0])/w[1]# Plot the hyperplaneplt.plot(xx,yy)plt.axis("off"),plt.show();

In this visualization, all observations of class 0 are black and observations of class 1 are light gray. The hyperplane is the decision boundary deciding how new observations are classified. Specifically, any observation above the line will by classified as class 0 while any observation below the line will be classified as class 1. We can prove this by creating a new observation in the top-left corner of our visualization, meaning it should be predicted to be class 0:

# Create new observationnew_observation=[[-2,3]]# Predict class of new observationsvc.predict(new_observation)

array([0])

There are a few things to note about SVCs. First, for the sake of visualization we limited our example to a binary example (e.g., only two classes); however, SVCs can work well with multiple classes. Second, as our visualization shows, the hyperplane is by definition linear (i.e., not curved). This was okay in this example because the data was linearly separable, meaning there was a hyperplane that could perfectly separate the two classes. Unfortunately, in the real world this will rarely be the case.

More typically, we will not be able to perfectly separate classes. In these situations there is a balance between SVC maximizing the margin of the hyperplane and minimizing the misclassification. In SVC, the latter is controlled with the hyperparameter C, the penalty imposed on errors. C is a parameter of the SVC learner and is the penalty for misclassifying a data point. When C is small, the classifier is okay with misclassified data points (high bias but low variance). When C is large, the classifier is heavily penalized for misclassified data and therefore bends over backwards to avoid any misclassified data points (low bias but high variance).

In scikit-learn, C is determined by the parameter C and

defaults to C=1.0. We should treat C has a

hyperparameter of our learning algorithm, which we tune using model

selection techniques in Chapter 12.

17.2 Handling Linearly Inseparable Classes Using Kernels

Solution

Train an extension of a support vector machine using kernel functions to create nonlinear decision boundaries:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.svmimportSVCfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScalerimportnumpyasnp# Set randomization seednp.random.seed(0)# Generate two featuresfeatures=np.random.randn(200,2)# Use a XOR gate (you don't need to know what this is) to generate# linearly inseparable classestarget_xor=np.logical_xor(features[:,0]>0,features[:,1]>0)target=np.where(target_xor,0,1)# Create a support vector machine with a radial basis function kernelsvc=SVC(kernel="rbf",random_state=0,gamma=1,C=1)# Train the classifiermodel=svc.fit(features,target)

Discussion

A full explanation of support vector machines is outside the scope of this book. However, a short explanation is likely beneficial for understanding support vector machines and kernels. For reasons best learned elsewhere, a support vector classifier can be represented as:

where β0 is the bias, S is the set of all support vector observations, α are the model parameters to be learned, and (xi, xi') are pairs of two support vector observations, xi and xi'. Most importantly, K is a kernel function that compares the similarity between xi and xi'. Don’t worry if you don’t understand kernel functions. For our purposes, just realize that K 1) determines the type of hyperplane used to separate our classes and 2) we create different hyperplanes by using different kernels. For example, if we wanted the basic linear hyperplane like the one we created in Recipe 17.1, we can use the linear kernel:

where p is the number of features. However, if we wanted a nonlinear decision boundary, we swap the linear kernel with a polynomial kernel:

where d is the degree of the polynomial kernel function. Alternatively, we can use one of the most common kernels in support vectors machines, the radial basis function kernel:

where γ is a hyperparameter and must be greater than zero. The main point of the preceding explanation is that if we have linearly inseparable data we can swap out a linear kernel with an alternative kernel to create a nonlinear hyperplane decision boundary.

We can understand the intuition behind kernels by visualizing a simple example. This function, based on one by Sebastian Raschka, plots the observations and decision boundary hyperplane of a two-dimensional space. You do not need to understand how this function works; I have included it here so you can experiment on your own:

# Plot observations and decision boundary hyperplanefrommatplotlib.colorsimportListedColormapimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltdefplot_decision_regions(X,y,classifier):cmap=ListedColormap(("red","blue"))xx1,xx2=np.meshgrid(np.arange(-3,3,0.02),np.arange(-3,3,0.02))Z=classifier.predict(np.array([xx1.ravel(),xx2.ravel()]).T)Z=Z.reshape(xx1.shape)plt.contourf(xx1,xx2,Z,alpha=0.1,cmap=cmap)foridx,clinenumerate(np.unique(y)):plt.scatter(x=X[y==cl,0],y=X[y==cl,1],alpha=0.8,c=cmap(idx),marker="+",label=cl)

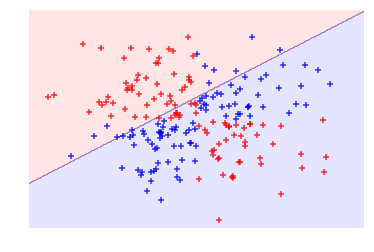

In our solution, we have data containing two features (i.e., two dimensions) and a target vector with the class of each observation. Importantly, the classes are assigned such that they are linearly inseparable. That is, there is no straight line we can draw that will divide the two classes. First, let’s create a support vector machine classifier with a linear kernel:

# Create support vector classifier with a linear kernelsvc_linear=SVC(kernel="linear",random_state=0,C=1)# Train modelsvc_linear.fit(features,target)

SVC(C=1, cache_size=200, class_weight=None, coef0=0.0, decision_function_shape='ovr', degree=3, gamma='auto', kernel='linear', max_iter=-1, probability=False, random_state=0, shrinking=True, tol=0.001, verbose=False)

Next, since we have only two features, we are working in a two-dimensional space and can visualize the observations, their classes, and our model’s linear hyperplane:

# Plot observations and hyperplaneplot_decision_regions(features,target,classifier=svc_linear)plt.axis("off"),plt.show();

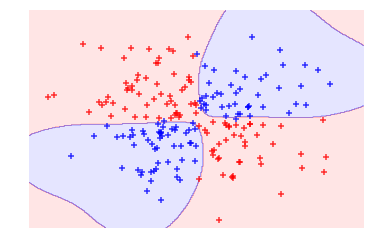

As we can see, our linear hyperplane did very poorly at dividing the two classes! Now, let’s swap out the linear kernel with a radial basis function kernel and use it to train a new model:

# Create a support vector machine with a radial basis function kernelsvc=SVC(kernel="rbf",random_state=0,gamma=1,C=1)# Train the classifiermodel=svc.fit(features,target)

And then visualize the observations and hyperplane:

# Plot observations and hyperplaneplot_decision_regions(features,target,classifier=svc)plt.axis("off"),plt.show();

By using the radial basis function kernel we could create a decision boundary able to do a much better job of separating the two classes than the linear kernel. This is the motivation behind using kernels in support vector machines.

In scikit-learn, we can select the kernel we want to use by using the

kernel parameter. Once we select a kernel, we will need to specify the

appropriate kernel options such as the value of d (using

the degree parameter) in polynomial kernels and γ

(using the gamma parameter) in radial basis function kernels. We will

also need to set the penalty parameter, C. When training the model, in

most cases we should treat all of these as hyperparameters and use model

selection techniques to identify the combination of their values that

produces the model with the best performance.

17.3 Creating Predicted Probabilities

Solution

When using scikit-learn’s SVC, set probability=True, train the

model, then use predict_proba to see the calibrated probabilities:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.svmimportSVCfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScalerimportnumpyasnp# Load datairis=datasets.load_iris()features=iris.datatarget=iris.target# Standardize featuresscaler=StandardScaler()features_standardized=scaler.fit_transform(features)# Create support vector classifier objectsvc=SVC(kernel="linear",probability=True,random_state=0)# Train classifiermodel=svc.fit(features_standardized,target)# Create new observationnew_observation=[[.4,.4,.4,.4]]# View predicted probabilitiesmodel.predict_proba(new_observation)

array([[ 0.00588822, 0.96874828, 0.0253635 ]])

Discussion

Many of the supervised learning algorithms we have covered use probability estimates to predict classes. For example, in k-nearest neighbor, an observation’s k neighbor’s classes were treated as votes to create a probability that an observation was of that class. Then the class with the highest probability was predicted. SVC’s use of a hyperplane to create decision regions does not naturally output a probability estimate that an observation is a member of a certain class. However, we can in fact output calibrated class probabilities with a few caveats. In an SVC with two classes, Platt scaling can be used, wherein first the SVC is trained, and then a separate cross-validated logistic regression is trained to map the SVC outputs into probabilities:

where A and B are parameter vectors and f is the ith observation’s signed distance from the hyperplane. When we have more than two classes, an extension of Platt scaling is used.

In more practical terms, creating predicted probabilities has two major issues. First, because we are training a second model with cross-validation, generating predicted probabilities can significantly increase the time it takes to train our model. Second, because the predicted probabilities are created using cross-validation, they might not always match the predicted classes. That is, an observation might be predicted to be class 1, but have a predicted probability of being class 1 of less than 0.5.

In scikit-learn, the predicted probabilities must be generated when the

model is being trained. We can do this by setting SVC’s probability to True. After the model is trained, we can output the estimated probabilities for each class using predict_proba.

17.4 Identifying Support Vectors

Solution

Train the model, then use support_vectors_:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.svmimportSVCfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScalerimportnumpyasnp#Load data with only two classesiris=datasets.load_iris()features=iris.data[:100,:]target=iris.target[:100]# Standardize featuresscaler=StandardScaler()features_standardized=scaler.fit_transform(features)# Create support vector classifier objectsvc=SVC(kernel="linear",random_state=0)# Train classifiermodel=svc.fit(features_standardized,target)# View support vectorsmodel.support_vectors_

array([[-0.5810659 , 0.43490123, -0.80621461, -0.50581312],

[-1.52079513, -1.67626978, -1.08374115, -0.8607697 ],

[-0.89430898, -1.46515268, 0.30389157, 0.38157832],

[-0.5810659 , -1.25403558, 0.09574666, 0.55905661]])

Discussion

Support vector machines get their name from the fact that the hyperplane is being determined by a relatively small number of observations, called the support vectors. Intuitively, think of the hyperplane as being “carried” by these support vectors. These support vectors are therefore very important to our model. For example, if we remove an observation that is not a support vector from the data, the model does not change; however, if we remove a support vector, the hyperplane will not have the maximum margin.

After we have trained an SVC, scikit-learn offers us a number of options

for identifying the support vector. In our solution, we used

support_vectors_ to output the actual observations’ features of the

four support vectors in our model. Alternatively, we can view the

indices of the support vectors using support_:

model.support_

array([23, 41, 57, 98], dtype=int32)

Finally, we can use n_support_ to find the number of support vectors belonging

to each class:

model.n_support_

array([2, 2], dtype=int32)

17.5 Handling Imbalanced Classes

Solution

Increase the penalty for misclassifying the smaller class using

class_weight:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.svmimportSVCfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScalerimportnumpyasnp#Load data with only two classesiris=datasets.load_iris()features=iris.data[:100,:]target=iris.target[:100]# Make class highly imbalanced by removing first 40 observationsfeatures=features[40:,:]target=target[40:]# Create target vector indicating if class 0, otherwise 1target=np.where((target==0),0,1)# Standardize featuresscaler=StandardScaler()features_standardized=scaler.fit_transform(features)# Create support vector classifiersvc=SVC(kernel="linear",class_weight="balanced",C=1.0,random_state=0)# Train classifiermodel=svc.fit(features_standardized,target)

Discussion

In support vector machines, C is a hyperparameter determining the penalty for misclassifying an observation. One method for handling imbalanced classes in support vector machines is to weight C by classes, so that:

where C is the penalty for misclassification, wj is a weight inversely proportional to class j’s frequency, and Cj is the C value for class j. The general idea is to increase the penalty for misclassifying minority classes to prevent them from being “overwhelmed” by the majority class.

In scikit-learn, when using SVC we can set the values for Cj automatically by setting class_weight='balanced'. The balanced argument automatically weighs classes such that:

where wj is the weight to class j, n is the number of observations, nj is the number of observations in class j, and k is the total number of classes.