Chapter 11. Model Evaluation

11.0 Introduction

In this chapter we will examine strategies for evaluating the quality of models created through our learning algorithms. It might appear strange to discuss model evaluation before discussing how to create them, but there is a method to our madness. Models are only as useful as the quality of their predictions, and thus fundamentally our goal is not to create models (which is easy) but to create high-quality models (which is hard). Therefore, before we explore the myriad learning algorithms, we first set up how we can evaluate the models they produce.

11.1 Cross-Validating Models

Solution

Create a pipeline that preprocesses the data, trains the model, and then evaluates it using cross-validation:

# Load librariesfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearnimportmetricsfromsklearn.model_selectionimportKFold,cross_val_scorefromsklearn.pipelineimportmake_pipelinefromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.preprocessingimportStandardScaler# Load digits datasetdigits=datasets.load_digits()# Create features matrixfeatures=digits.data# Create target vectortarget=digits.target# Create standardizerstandardizer=StandardScaler()# Create logistic regression objectlogit=LogisticRegression()# Create a pipeline that standardizes, then runs logistic regressionpipeline=make_pipeline(standardizer,logit)# Create k-Fold cross-validationkf=KFold(n_splits=10,shuffle=True,random_state=1)# Conduct k-fold cross-validationcv_results=cross_val_score(pipeline,# Pipelinefeatures,# Feature matrixtarget,# Target vectorcv=kf,# Cross-validation techniquescoring="accuracy",# Loss functionn_jobs=-1)# Use all CPU scores# Calculate meancv_results.mean()

0.96493171942892597

Discussion

At first consideration, evaluating supervised-learning models might appear straightforward: train a model and then calculate how well it did using some performance metric (accuracy, squared errors, etc.). However, this approach is fundamentally flawed. If we train a model using our data, and then evaluate how well it did on that data, we are not achieving our desired goal. Our goal is not to evaluate how well the model does on our training data, but how well it does on data it has never seen before (e.g., a new customer, a new crime, a new image). For this reason, our method of evaluation should help us understand how well models are able to make predictions from data they have never seen before.

One strategy might be to hold off a slice of data for testing. This is called validation (or hold-out). In validation our observations (features and targets) are split into two sets, traditionally called the training set and the test set. We take the test set and put it off to the side, pretending that we have never seen it before. Next we train our model using our training set, using the features and target vector to teach the model how to make the best prediction. Finally, we simulate having never before seen external data by evaluating how our model trained on our training set performs on our test set. However, the validation approach has two major weaknesses. First, the performance of the model can be highly dependent on which few observations were selected for the test set. Second, the model is not being trained using all the available data, and not being evaluated on all the available data.

A better strategy, which overcomes these weaknesses, is called k-fold cross-validation (KFCV). In KFCV, we split the data into k parts called “folds.” The model is then trained using k – 1 folds—combined into one training set—and then the last fold is used as a test set. We repeat this k times, each time using a different fold as the test set. The performance on the model for each of the k iterations is then averaged to produce an overall measurement.

In our solution, we conducted k-fold cross-validation using 10 folds and outputted the evaluation scores to cv_results:

# View score for all 10 foldscv_results

array([ 0.97222222, 0.97777778, 0.95555556, 0.95 , 0.95555556,

0.98333333, 0.97777778, 0.96648045, 0.96089385, 0.94972067])

There are three important points to consider when we are using KFCV. First, KFCV assumes that each observation was created independent from the other (i.e., the data is independent identically distributed [IID]). If the data is IID, it is a good idea to shuffle observations when assigning to folds. In scikit-learn we can set shuffle=True to perform shuffling.

Second, when we are using KFCV to evaluate a classifier, it is often

beneficial to have folds containing roughly the same percentage of

observations from each of the different target classes (called stratified k-fold). For example, if our target vector contained gender and 80% of the observations were male, then each fold would contain 80% male and 20% female observations. In scikit-learn, we can conduct stratified k-fold cross-validation by replacing the KFold class with StratifiedKFold.

Finally, when we are using validation sets or cross-validation, it is important to preprocess data based on the training set and then apply those transformations to both the training and test set. For example, when we fit our standardization object, standardizer, we calculate the mean and variance of only the training set. Then we apply that transformation (using transform) to both the training and test sets:

# Import libraryfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_split# Create training and test setsfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,test_size=0.1,random_state=1)# Fit standardizer to training setstandardizer.fit(features_train)# Apply to both training and test setsfeatures_train_std=standardizer.transform(features_train)features_test_std=standardizer.transform(features_test)

The reason for this is because we are pretending that the test set is unknown data. If we fit both our preprocessors using observations from both training and test sets, some of the information from the test set leaks into our training set. This rule applies for any preprocessing step such as feature selection.

scikit-learn’s pipeline package makes this easy to do while using

cross-validation techniques. We first create a pipeline that

preprocesses the data (e.g., standardizer) and then trains a model

(logistic regression, logit):

# Create a pipelinepipeline=make_pipeline(standardizer,logit)

Then we run KFCV using that pipeline and scikit does all the work for us:

# Do k-fold cross-validationcv_results=cross_val_score(pipeline,# Pipelinefeatures,# Feature matrixtarget,# Target vectorcv=kf,# Cross-validation techniquescoring="accuracy",# Loss functionn_jobs=-1)# Use all CPU scores

cross_val_score comes with three parameters that we have not

discussed that are worth noting. cv determines our cross-validation technique. K-fold is the most common by far, but there are others, like leave-one-out-cross-validation where the number of folds k equals the number of observations. The scoring parameter defines our metric for success, a number of which are discussed in other recipes in this chapter. Finally, n_jobs=-1 tells scikit-learn to use every core available. For example, if your computer has four cores (a common number for laptops), then scikit-learn will use all four cores at once to speed up the operation.

11.2 Creating a Baseline Regression Model

Solution

Use scikit-learn’s DummyRegressor to create a simple model to use as a

baseline:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.datasetsimportload_bostonfromsklearn.dummyimportDummyRegressorfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_split# Load databoston=load_boston()# Create featuresfeatures,target=boston.data,boston.target# Make test and training splitfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,random_state=0)# Create a dummy regressordummy=DummyRegressor(strategy='mean')# "Train" dummy regressordummy.fit(features_train,target_train)# Get R-squared scoredummy.score(features_test,target_test)

-0.0011193592039553391

To compare, we train our model and evaluate the performance score:

# Load libraryfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLinearRegression# Train simple linear regression modelols=LinearRegression()ols.fit(features_train,target_train)# Get R-squared scoreols.score(features_test,target_test)

0.63536207866746675

Discussion

DummyRegressor allows us to create a very simple model that we

can use as a baseline to compare against our actual model. This can

often be useful to simulate a “naive” existing prediction process in a

product or system. For example, a product might have been originally

hardcoded to assume that all new users will spend $100 in the first

month, regardless of their features. If we encode that assumption into a baseline model, we are able to concretely state the benefits of using a machine learning approach.

DummyRegressor uses the strategy parameter to set the method of making predictions, including the mean or median value in the training set. Furthermore, if we set strategy to constant and use the constant parameter, we can set the dummy regressor to predict some constant value for every observation:

# Create dummy regressor that predicts 20's for everythingclf=DummyRegressor(strategy='constant',constant=20)clf.fit(features_train,target_train)# Evaluate scoreclf.score(features_test,target_test)

-0.065105020293257265

One small note regarding score. By default, score returns the

coefficient of determination (R-squared, R2) score:

where yi is the true value of the target observation, is the predicted value, and ȳ is the mean value for the target vector.

The closer R2 is to 1, the more of the variance in the target vector that is explained by the features.

11.3 Creating a Baseline Classification Model

Solution

Use scikit-learn’s DummyClassifier:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.datasetsimportload_irisfromsklearn.dummyimportDummyClassifierfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_split# Load datairis=load_iris()# Create target vector and feature matrixfeatures,target=iris.data,iris.target# Split into training and test setfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,random_state=0)# Create dummy classifierdummy=DummyClassifier(strategy='uniform',random_state=1)# "Train" modeldummy.fit(features_train,target_train)# Get accuracy scoredummy.score(features_test,target_test)

0.42105263157894735

By comparing the baseline classifier to our trained classifier, we can see the improvement:

# Load libraryfromsklearn.ensembleimportRandomForestClassifier# Create classifierclassifier=RandomForestClassifier()# Train modelclassifier.fit(features_train,target_train)# Get accuracy scoreclassifier.score(features_test,target_test)

0.94736842105263153

Discussion

A common measure of a classifier’s performance is how much better it is

than random guessing. scikit-learn’s DummyClassifier makes this

comparison easy. The strategy parameter gives us a number of options

for generating values. There are two particularly useful strategies.

First, stratified makes predictions that are proportional to the training

set’s target vector’s class proportions (i.e., if 20% of the observations

in the training data are women, then DummyClassifier will predict

women 20% of the time). Second, uniform will generate predictions

uniformly at random between the different classes. For example, if 20%

of observations are women and 80% are men, uniform will produce

predictions that are 50% women and 50% men.

11.4 Evaluating Binary Classifier Predictions

Solution

Use scikit-learn’s cross_val_score to conduct cross-validation while

using the scoring parameter to define one of a number of

performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and

F1.

Accuracy is a common performance metric. It is simply the proportion of observations predicted correctly:

where:

-

TP is the number of true positives. Observations that are part of the positive class (has the disease, purchased the product, etc.) and that we predicted correctly.

-

TN is the number of true negatives. Observations that are part of the negative class (does not have the disease, did not purchase the product, etc.) and that we predicted correctly.

-

FP is the number of false positives. Also called a Type I error. Observations predicted to be part of the positive class that are actually part of the negative class.

-

FN is the number of false negatives. Also called a Type II error. Observations predicted to be part of the negative class that are actually part of the positive class.

We can measure accuracy in three-fold (the default number of folds)

cross-validation by setting scoring="accuracy":

# Load librariesfromsklearn.model_selectionimportcross_val_scorefromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_classification# Generate features matrix and target vectorX,y=make_classification(n_samples=10000,n_features=3,n_informative=3,n_redundant=0,n_classes=2,random_state=1)# Create logistic regressionlogit=LogisticRegression()# Cross-validate model using accuracycross_val_score(logit,X,y,scoring="accuracy")

array([ 0.95170966, 0.9580084 , 0.95558223])

The appeal of accuracy is that it has an intuitive and plain English explanation: proportion of observations predicted correctly. However, in the real world, often our data has imbalanced classes (e.g., the 99.9% of observations are of class 1 and only 0.1% are class 2). When in the presence of imbalanced classes, accuracy suffers from a paradox where a model is highly accurate but lacks predictive power. For example, imagine we are trying to predict the presence of a very rare cancer that occurs in 0.1% of the population. After training our model, we find the accuracy is at 95%. However, 99.9% of people do not have the cancer: if we simply created a model that “predicted” that nobody had that form of cancer, our naive model would be 4.9% more accurate, but clearly is not able to predict anything. For this reason, we are often motivated to use other metrics like precision, recall, and the F1 score.

Precision is the proportion of every observation predicted to be positive that is actually positive. We can think about it as a measurement noise in our predictions—that is, when we predict something is positive, how likely we are to be right. Models with high precision are pessimistic in that they only predict an observation is of the positive class when they are very certain about it. Formally, precision is:

# Cross-validate model using precisioncross_val_score(logit,X,y,scoring="precision")

array([ 0.95252404, 0.96583282, 0.95558223])

Recall is the proportion of every positive observation that is truly positive. Recall measures the model’s ability to identify an observation of the positive class. Models with high recall are optimistic in that they have a low bar for predicting that an observation is in the positive class:

# Cross-validate model using recallcross_val_score(logit,X,y,scoring="recall")

array([ 0.95080984, 0.94961008, 0.95558223])

If this is the first time you have encountered precision and recall, it is understandable if it takes you a little while to fully understand them. This is one of the downsides to accuracy; precision and recall are less intuitive. Almost always we want some kind of balance between precision and recall, and this role is filled by the F1 score. The F1 score is the harmonic mean (a kind of average used for ratios):

It is a measure of correctness achieved in positive prediction—that is, of observations labeled as positive, how many are actually positive:

# Cross-validate model using f1cross_val_score(logit,X,y,scoring="f1")

array([ 0.95166617, 0.95765275, 0.95558223])

Discussion

As an evaluation metric, accuracy has some valuable properties, especially its simple intuition. However, better metrics often involve using some balance of precision and recall—that is, a trade-off between the optimism and pessimism of our model. F1 represents a balance between the recall and precision, where the relative contributions of both are equal.

Alternatively to using cross_val_score, if we already have the true y

values and the predicted y values, we can calculate metrics like

accuracy and recall directly:

# Load libraryfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_splitfromsklearn.metricsimportaccuracy_score# Create training and test splitX_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(X,y,test_size=0.1,random_state=1)# Predict values for training target vectory_hat=logit.fit(X_train,y_train).predict(X_test)# Calculate accuracyaccuracy_score(y_test,y_hat)

0.94699999999999995

See Also

11.5 Evaluating Binary Classifier Thresholds

Solution

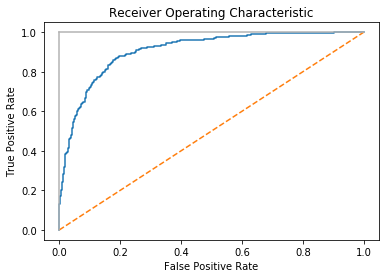

The Receiving Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a common method for evaluating the quality of a binary classifier. ROC compares the presence of true positives and false positives at every probability

threshold (i.e., the probability at which an observation is predicted to be a class). By plotting the ROC curve, we can see how the model

performs. A classifier that predicts every observation correctly would

look like the solid light gray line in the following chart, going straight up to the top immediately. A classifier that predicts at random will appear as the diagonal line. The better the model, the closer it is to the solid line. In scikit-learn, we can use roc_curve to calculate the true and false positives at each threshold, then plot them:

# Load librariesimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltfromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_classificationfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.metricsimportroc_curve,roc_auc_scorefromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_split# Create feature matrix and target vectorfeatures,target=make_classification(n_samples=10000,n_features=10,n_classes=2,n_informative=3,random_state=3)# Split into training and test setsfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,test_size=0.1,random_state=1)# Create classifierlogit=LogisticRegression()# Train modellogit.fit(features_train,target_train)# Get predicted probabilitiestarget_probabilities=logit.predict_proba(features_test)[:,1]# Create true and false positive ratesfalse_positive_rate,true_positive_rate,threshold=roc_curve(target_test,target_probabilities)# Plot ROC curveplt.title("Receiver Operating Characteristic")plt.plot(false_positive_rate,true_positive_rate)plt.plot([0,1],ls="--")plt.plot([0,0],[1,0],c=".7"),plt.plot([1,1],c=".7")plt.ylabel("True Positive Rate")plt.xlabel("False Positive Rate")plt.show()

Discussion

Up until now we have only examined models based on the values they

predict. However, in many learning algorithms those predicted values are based off of probability estimates. That is, each observation is given an explicit probability of belonging in each class. In our solution, we can use predict_proba to see the predicted probabilities for the first observation:

# Get predicted probabilitieslogit.predict_proba(features_test)[0:1]

array([[ 0.8688938, 0.1311062]])

We can see the classes using classes_:

logit.classes_

array([0, 1])

In this example, the first observation has an ~87% chance of being in the negative class (0) and a 13% chance of being in the positive class (1). By default, scikit-learn predicts an observation is part of the positive class if the probability is greater than 0.5 (called the threshold). However, instead of a middle ground, we will often want to explicitly bias our model to use a different threshold for substantive reasons. For example, if a false positive is very costly to our company, we might prefer a model that has a high probability threshold. We fail to predict some positives, but when an observation is predicted to be positive, we can be very confident that the prediction is correct. This trade-off is represented in the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR). The true positive rate is the number of observations correctly predicted true divided by all true positive observations:

The false positive rate is the number of incorrectly predicted positives divided by all true negative observations:

The ROC curve represents the respective TPR and FPR for every probability threshold. For example, in our solution a threshold of roughly 0.50 has a TPR of \0.81 and an FPR of \0.15:

("Threshold:",threshold[116])("True Positive Rate:",true_positive_rate[116])("False Positive Rate:",false_positive_rate[116])

Threshold: 0.528224777887 True Positive Rate: 0.810204081633 False Positive Rate: 0.154901960784

However, if we increase the threshold to ~80% (i.e., increase how certain the model has to be before it predicts an observation as positive) the TPR drops significantly but so does the FPR:

("Threshold:",threshold[45])("True Positive Rate:",true_positive_rate[45])("False Positive Rate:",false_positive_rate[45])

Threshold: 0.808019566563 True Positive Rate: 0.563265306122 False Positive Rate: 0.0470588235294

This is because our higher requirement for being predicted to be in the positive class has made the model not identify a number of positive observations (the lower TPR), but also reduce the noise from negative observations being predicted as positive (the lower FPR).

In addition to being able to visualize the trade-off between TPR and

FPR, the ROC curve can also be used as a general metric for a model. The

better a model is, the higher the curve and thus the greater the area

under the curve. For this reason, it is common to calculate the area

under the ROC curve (AUCROC) to judge the overall equality of a model at

all possible thresholds. The closer the AUCROC is to 1, the better the

model. In scikit-learn we can calculate the AUCROC using

roc_auc_score:

# Calculate area under curveroc_auc_score(target_test,target_probabilities)

0.90733893557422962

11.6 Evaluating Multiclass Classifier Predictions

Solution

Use cross-validation with an evaluation metric capable of handling more than two classes:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.model_selectionimportcross_val_scorefromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_classification# Generate features matrix and target vectorfeatures,target=make_classification(n_samples=10000,n_features=3,n_informative=3,n_redundant=0,n_classes=3,random_state=1)# Create logistic regressionlogit=LogisticRegression()# Cross-validate model using accuracycross_val_score(logit,features,target,scoring='accuracy')

array([ 0.83653269, 0.8259826 , 0.81308131])

Discussion

When we have balanced classes (e.g., a roughly equal number of observations in each class of the target vector), accuracy is—just like in the binary class setting—a simple and interpretable choice for an evaluation metric. Accuracy is the number of correct predictions divided by the number of observations and works just as well in the multiclass as binary setting. However, when we have imbalanced classes (a common scenario), we should be inclined to use other evaluation metrics.

Many of scikit-learn’s built-in metrics are for evaluating binary classifiers. However, many of these metrics can be extended for use when we have more than two classes. Precision, recall, and F1 scores are useful metrics that we have already covered in detail in previous recipes. While all of them were originally designed for binary classifiers, we can apply them to multiclass settings by treating our data as a set of binary classes. Doing so enables us to apply the metrics to each class as if it were the only class in the data, and then aggregate the evaluation scores for all the classes by averaging them:

# Cross-validate model using macro averaged F1 scorecross_val_score(logit,features,target,scoring='f1_macro')

array([ 0.83613125, 0.82562258, 0.81293539])

In this code, _macro refers to the method used to average the

evaluation scores from the classes:

macro-

Calculate mean of metric scores for each class, weighting each class equally.

weighted-

Calculate mean of metric scores for each class, weighting each class proportional to its size in the data.

micro-

Calculate mean of metric scores for each observation-class combination.

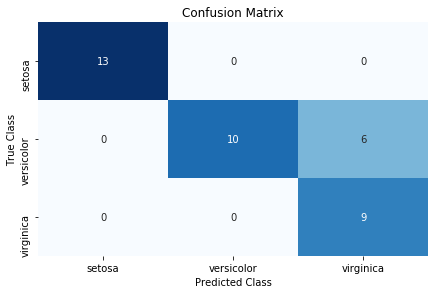

11.7 Visualizing a Classifier’s Performance

Solution

Use a confusion matrix, which compares predicted classes and true classes:

# Load librariesimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltimportseabornassnsfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_splitfromsklearn.metricsimportconfusion_matriximportpandasaspd# Load datairis=datasets.load_iris()# Create feature matrixfeatures=iris.data# Create target vectortarget=iris.target# Create list of target class namesclass_names=iris.target_names# Create training and test setfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,random_state=1)# Create logistic regressionclassifier=LogisticRegression()# Train model and make predictionstarget_predicted=classifier.fit(features_train,target_train).predict(features_test)# Create confusion matrixmatrix=confusion_matrix(target_test,target_predicted)# Create pandas dataframedataframe=pd.DataFrame(matrix,index=class_names,columns=class_names)# Create heatmapsns.heatmap(dataframe,annot=True,cbar=None,cmap="Blues")plt.title("Confusion Matrix"),plt.tight_layout()plt.ylabel("True Class"),plt.xlabel("Predicted Class")plt.show()

Discussion

Confusion matrices are an easy, effective visualization of a classifier’s performance. One of the major benefits of confusion matrices is their interpretability. Each column of the matrix (often visualized as a heatmap) represents predicted classes, while every row shows true classes. The end result is that every cell is one possible combination of predict and true classes. This is probably best explained using an example. In the solution, the top-left cell is the number of observations predicted to be Iris setosa (indicated by the column) that are actually Iris setosa (indicated by the row). This means the models accurately predicted all Iris setosa flowers. However, the model does not do as well at predicting Iris virginica. The bottom-right cell indicates that the model successfully predicted nine observations were Iris virginica, but (looking one cell up) predicted six flowers to be viriginica that were actually Iris versicolor.

There are three things worth noting about confusion matrices. First, a perfect model will have values along the diagonal and zeros everywhere else. A bad model will look like the observation counts will be spread evenly around cells. Second, a confusion matrix lets us see not only where the model was wrong, but also how it was wrong. That is, we can look at patterns of misclassification. For example, our model had an easy time differentiating Iris virginica and Iris setosa, but a much more difficult time classifying Iris virginica and Iris versicolor. Finally, confusion matrices work with any number of classes (although if we had one million classes in our target vector, the confusion matrix visualization might be difficult to read).

11.8 Evaluating Regression Models

Solution

Use mean squared error (MSE):

# Load librariesfromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_regressionfromsklearn.model_selectionimportcross_val_scorefromsklearn.linear_modelimportLinearRegression# Generate features matrix, target vectorfeatures,target=make_regression(n_samples=100,n_features=3,n_informative=3,n_targets=1,noise=50,coef=False,random_state=1)# Create a linear regression objectols=LinearRegression()# Cross-validate the linear regression using (negative) MSEcross_val_score(ols,features,target,scoring='neg_mean_squared_error')

array([-1718.22817783, -3103.4124284 , -1377.17858823])

Another common regression metric is the coefficient of determination, R2:

# Cross-validate the linear regression using R-squaredcross_val_score(ols,features,target,scoring='r2')

array([ 0.87804558, 0.76395862, 0.89154377])

Discussion

MSE is one of the most common evaluation metrics for regression models. Formally, MSE is:

where n is the number of observations, yi is the true value of the target we are trying to predict for observation i, and is the model’s predicted value for yi. MSE is a measurement of the squared sum of all distances between predicted and true values. The higher the value of MSE, the greater the total squared error and thus the worse the model. There are a number of mathematical benefits to squaring the error term, including that it forces all error values to be positive, but one often unrealized implication is that squaring penalizes a few large errors more than many small errors, even if the absolute value of the errors is the same. For example, imagine two models, A and B, each with two observations:

-

Model A has errors of 0 and 10 and thus its MSE is 02 + 102 = 100.

-

Model B has two errors of 5 each, and thus its MSE is 52 + 52 = 50.

Both models have the same total error, 10; however, MSE would consider Model A (MSE = 100) worse than Model B (MSE = 50). In practice this implication is rarely an issue (and indeed can be theoretically beneficial) and MSE works perfectly fine as an evaluation metric.

One important note: by default in scikit-learn arguments of the

scoring parameter assume that higher values are better than lower

values. However, this is not the case for MSE, where higher values mean

a worse model. For this reason, scikit-learn looks at the negative MSE using the neg_mean_squared_error argument.

A common alternative regression evaluation metric is R2, which measures the amount of variance in the target vector that is explained by the model:

where yi is the true target value of the ith observation, is the predicted value for the ith observation, and is the mean value of the target vector. The closer to 1.0, the better the model.

11.9 Evaluating Clustering Models

Solution

The short answer is that you probably can’t, at least not in the way you want.

That said, one option is to evaluate clustering using silhouette coefficients, which measure the quality of the clusters:

importnumpyasnpfromsklearn.metricsimportsilhouette_scorefromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.clusterimportKMeansfromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_blobs# Generate feature matrixfeatures,_=make_blobs(n_samples=1000,n_features=10,centers=2,cluster_std=0.5,shuffle=True,random_state=1)# Cluster data using k-means to predict classesmodel=KMeans(n_clusters=2,random_state=1).fit(features)# Get predicted classestarget_predicted=model.labels_# Evaluate modelsilhouette_score(features,target_predicted)

0.89162655640721422

Discussion

Supervised model evaluation compares predictions (e.g., classes or quantitative values) with the corresponding true values in the target vector. However, the most common motivation for using clustering methods is that your data doesn’t have a target vector. There are a number of clustering evaluation metrics that require a target vector, but again, using unsupervised learning approaches like clustering when you have a target vector available to you is probably handicapping yourself unnecessarily.

While we cannot evaluate predictions versus true values if we don’t have a target vector, we can evaluate the nature of the clusters themselves. Intuitively, we can imagine “good” clusters having very small distances between observations in the same cluster (i.e., dense clusters) and large distances between the different clusters (i.e., well-separated clusters). Silhouette coefficients provide a single value measuring both traits. Formally, the ith observation’s silhouette coefficient is:

where si is the silhouette coefficient for observation i, ai is the mean distance between i and all observations of the same class, and bi is the mean distance between i and all observations from the closest cluster of a different class. The value returned by silhouette_score is the mean silhouette coefficient for all observations. Silhouette coefficients range between –1 and 1, with 1 indicating dense, well-separated clusters.

11.10 Creating a Custom Evaluation Metric

Solution

Create the metric as a function and convert it into a scorer function

using scikit-learn’s make_scorer:

# Load librariesfromsklearn.metricsimportmake_scorer,r2_scorefromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_splitfromsklearn.linear_modelimportRidgefromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_regression# Generate features matrix and target vectorfeatures,target=make_regression(n_samples=100,n_features=3,random_state=1)# Create training set and test setfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,test_size=0.10,random_state=1)# Create custom metricdefcustom_metric(target_test,target_predicted):# Calculate r-squared scorer2=r2_score(target_test,target_predicted)# Return r-squared scorereturnr2# Make scorer and define that higher scores are betterscore=make_scorer(custom_metric,greater_is_better=True)# Create ridge regression objectclassifier=Ridge()# Train ridge regression modelmodel=classifier.fit(features_train,target_train)# Apply custom scorerscore(model,features_test,target_test)

0.99979061028820582

Discussion

While scikit-learn has a number of built-in metrics for evaluating model

performance, it is often useful to define our own metrics. scikit-learn

makes this easy using make_scorer. First, we define a function that

takes in two arguments—the ground truth target vector and our predicted

values—and outputs some score. Second, we use make_scorer to create a

scorer object, making sure to specify whether higher or lower scores are

desirable (using the greater_is_better parameter).

The custom metric in the solution (custom_metric) is a toy

example since it simply wraps a built-in metric for calculating the

R2 score. In a real-world situation, we would replace the custom_metric function with whatever custom metric we wanted. However, we can see that the custom metric that calculates R2 does work by comparing the results to scikit-learn’s r2_score built-in

method:

# Predict valuestarget_predicted=model.predict(features_test)# Calculate r-squared scorer2_score(target_test,target_predicted)

0.99979061028820582

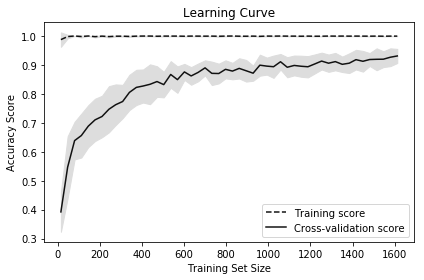

11.11 Visualizing the Effect of Training Set Size

Solution

Plot the learning curve:

# Load librariesimportnumpyasnpimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltfromsklearn.ensembleimportRandomForestClassifierfromsklearn.datasetsimportload_digitsfromsklearn.model_selectionimportlearning_curve# Load datadigits=load_digits()# Create feature matrix and target vectorfeatures,target=digits.data,digits.target# Create CV training and test scores for various training set sizestrain_sizes,train_scores,test_scores=learning_curve(# ClassifierRandomForestClassifier(),# Feature matrixfeatures,# Target vectortarget,# Number of foldscv=10,# Performance metricscoring='accuracy',# Use all computer coresn_jobs=-1,# Sizes of 50# training settrain_sizes=np.linspace(0.01,1.0,50))# Create means and standard deviations of training set scorestrain_mean=np.mean(train_scores,axis=1)train_std=np.std(train_scores,axis=1)# Create means and standard deviations of test set scorestest_mean=np.mean(test_scores,axis=1)test_std=np.std(test_scores,axis=1)# Draw linesplt.plot(train_sizes,train_mean,'--',color="#111111",label="Training score")plt.plot(train_sizes,test_mean,color="#111111",label="Cross-validation score")# Draw bandsplt.fill_between(train_sizes,train_mean-train_std,train_mean+train_std,color="#DDDDDD")plt.fill_between(train_sizes,test_mean-test_std,test_mean+test_std,color="#DDDDDD")# Create plotplt.title("Learning Curve")plt.xlabel("Training Set Size"),plt.ylabel("Accuracy Score"),plt.legend(loc="best")plt.tight_layout()plt.show()

Discussion

Learning curves visualize the performance (e.g., accuracy, recall) of a model on the training set and during cross-validation as the number of observations in the training set increases. They are commonly used to determine if our learning algorithms would benefit from gathering additional training data.

In our solution, we plot the accuracy of a random forest classifier at 50 different training set sizes ranging from 1% of observations to 100%. The increasing accuracy score of the cross-validated models tell us that we would likely benefit from additional observations (although in practice this might not be feasible).

11.12 Creating a Text Report of Evaluation Metrics

Solution

Use scikit-learn’s classification_report:

# Load librariesfromsklearnimportdatasetsfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_splitfromsklearn.metricsimportclassification_report# Load datairis=datasets.load_iris()# Create feature matrixfeatures=iris.data# Create target vectortarget=iris.target# Create list of target class namesclass_names=iris.target_names# Create training and test setfeatures_train,features_test,target_train,target_test=train_test_split(features,target,random_state=1)# Create logistic regressionclassifier=LogisticRegression()# Train model and make predictionsmodel=classifier.fit(features_train,target_train)target_predicted=model.predict(features_test)# Create a classification report(classification_report(target_test,target_predicted,target_names=class_names))

precision recall f1-score support

setosa 1.00 1.00 1.00 13

versicolor 1.00 0.62 0.77 16

virginica 0.60 1.00 0.75 9

avg / total 0.91 0.84 0.84 38

Discussion

classification_report provides a quick means for us to see some common

evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score (described

earlier in this chapter). Support refers to the number of observations

in each class.

See Also

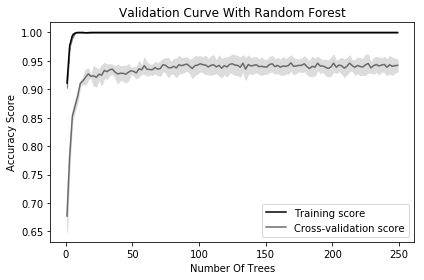

11.13 Visualizing the Effect of Hyperparameter Values

Solution

Plot the validation curve:

# Load librariesimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltimportnumpyasnpfromsklearn.datasetsimportload_digitsfromsklearn.ensembleimportRandomForestClassifierfromsklearn.model_selectionimportvalidation_curve# Load datadigits=load_digits()# Create feature matrix and target vectorfeatures,target=digits.data,digits.target# Create range of values for parameterparam_range=np.arange(1,250,2)# Calculate accuracy on training and test set using range of parameter valuestrain_scores,test_scores=validation_curve(# ClassifierRandomForestClassifier(),# Feature matrixfeatures,# Target vectortarget,# Hyperparameter to examineparam_name="n_estimators",# Range of hyperparameter's valuesparam_range=param_range,# Number of foldscv=3,# Performance metricscoring="accuracy",# Use all computer coresn_jobs=-1)# Calculate mean and standard deviation for training set scorestrain_mean=np.mean(train_scores,axis=1)train_std=np.std(train_scores,axis=1)# Calculate mean and standard deviation for test set scorestest_mean=np.mean(test_scores,axis=1)test_std=np.std(test_scores,axis=1)# Plot mean accuracy scores for training and test setsplt.plot(param_range,train_mean,label="Training score",color="black")plt.plot(param_range,test_mean,label="Cross-validation score",color="dimgrey")# Plot accurancy bands for training and test setsplt.fill_between(param_range,train_mean-train_std,train_mean+train_std,color="gray")plt.fill_between(param_range,test_mean-test_std,test_mean+test_std,color="gainsboro")# Create plotplt.title("Validation Curve With Random Forest")plt.xlabel("Number Of Trees")plt.ylabel("Accuracy Score")plt.tight_layout()plt.legend(loc="best")plt.show()

Discussion

Most training algorithms (including many covered in this book) contain hyperparameters that must be chosen before the training process begins. For example, a random forest classifier creates a “forest” of decision trees, each of which votes on the predicted class of an observation. One hyperparameter in random forest classifiers is the number of trees in the forest. Most often hyperparameter values are selected during model selection (see Chapter 12). However, it is occasionally useful to visualize how model performance changes as the hyperparameter value changes. In our solution, we plot the changes in accuracy for a random forest classifier for the training set and during cross-validation as the number of trees increases. When we have a small number of trees, both the training and cross-validation score are low, suggesting the model is underfitted. As the number of trees increases to 250, the accuracy of both levels off, suggesting there is probably not much value in the computational cost of training a massive forest.

In scikit-learn, we can calculate the validation curve using

validation_curve, which contains three important parameters:

-

param_nameis the name of the hyperparameter to vary. -

param_rangeis the value of the hyperparameter to use. -

scoringis the evaluation metric used to judge to model.