Maintainability

Successful machine learning systems in production often outlive their creators (within an organization). As such, these systems must be maintained by engineers who don’t necessarily understand why certain development choices were made. Maintainability is a software principle that extends beyond security and machine learning. All software systems should optimize for maintainability, because poorly maintained systems will eventually be deprecated and killed. Even worse, such systems can limp along for decades, draining resources from the organization and preventing it from implementing its goals. A recent paper from Google28 argues that due to their complexity and dependence on ever-changing data, machine learning systems are even more susceptible than other systems to buildup of technical debt.

In this section we briefly touch on a few maintainability concepts. We do not go into great detail, because many of these concepts are covered in depth in dedicated publications.29

Problem: Checkpointing, Versioning, and Deploying Models

Is a machine learning model code or data? Because models are so tightly coupled to the nature of the data used to generate them, there is an argument that they should be treated as data, because code should be independent of the data it processes. However, there is operational value in subjecting models to the same versioning and deployment processes that conventional source code is put through. Our view is that machine learning models should be treated both as code and data. Storing model parameters/hyperparameters in version-control systems such as Git makes the restoration of previous models very convenient when something goes wrong. Storing models in databases allows for querying parameters across versions in parallel, which can be valuable in some contexts.

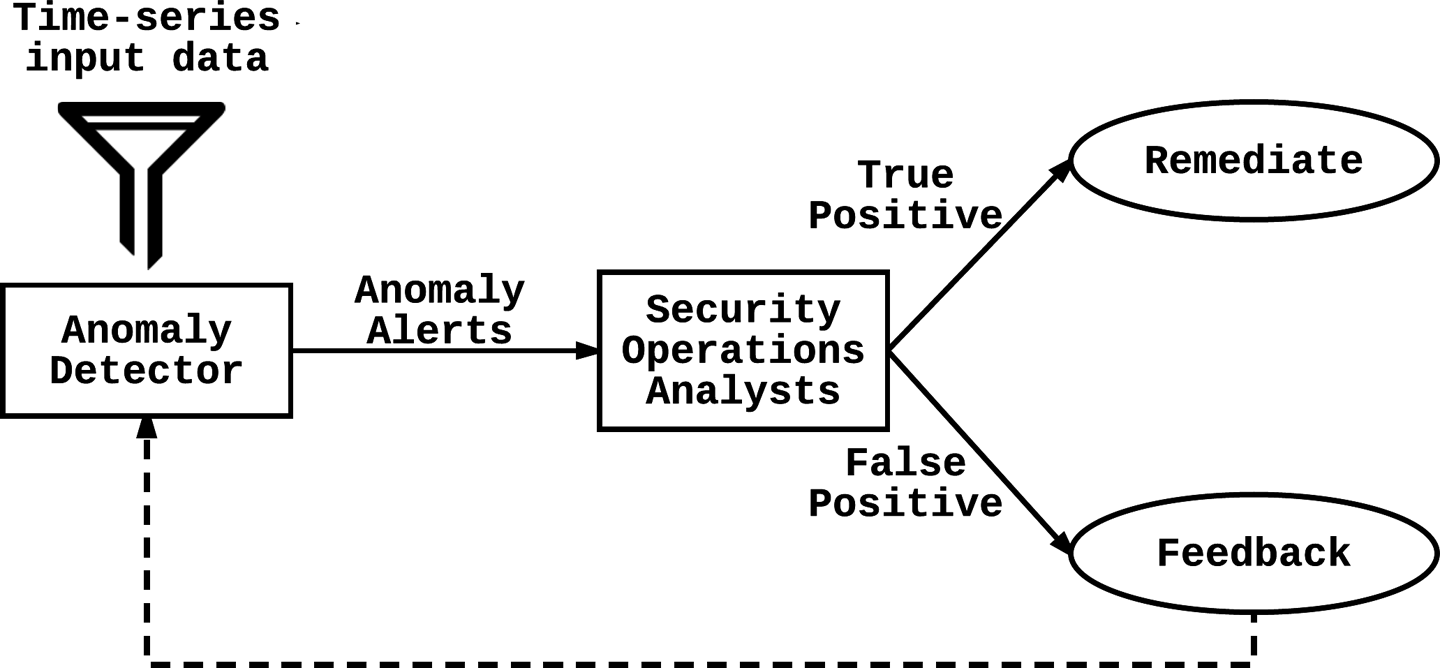

For audit and development purposes, it is good to ensure that any decision that a system makes at any point in time can be reproduced. For instance, consider a web application anomaly detection server that flags a particular user session as anomalous. Because of the high fluctuations in input that web applications can see, this system attempts to continuously measure and adapt to the changing traffic through continuous and automatic parameter tuning. Furthermore, machine learning models are continuously tuned and improved over time, whether due to automated learning mechanisms or human engineers. Checkpointing and versioning of models enables us to see if this user session would have triggered the model from two months ago.

Serializing models for storage can be as simple as using the Python pickle object serialization interface. For space and performance efficiency as well as better portability, you can use a custom storage format that saves all parameter information required to reconstruct a machine learning model. For instance, storing all the feature weights of a trained linear regression model in a JSON file is a platform- and framework-agnostic way to save and reconstruct linear regressors.

Predictive Model Markup Language (PMML) is the leading open standard for XML-based serialization and sharing of predictive data mining models.30 Besides storing model parameters, the format can also encode various transformations applied to the data in preprocessing and postprocessing steps. A convenient feature of the PMML format is the ability to develop a model using one machine learning framework and deploy it on a different machine learning framework. As the common denominator between different systems, PMML enables developers to compare the performance and accuracy of the same model executed on different machine learning frameworks.

The deployment mechanism for machine learning models should be engineered to be as foolproof as possible. Machine learning systems can be deployed as web services (accessible via REST APIs, for example), or embedded in backend software. Tight coupling with other systems is discouraged because it causes a lot of friction during deployment and results in a very inflexible framework. Accessing machine learning systems through APIs adds a valuable layer of indirection which can lend a lot of flexibility during the deployment, A/B testing, and debugging process.

Goal: Graceful Degradation

Software systems should fail gracefully and transparently. If a more advanced and demanding version of a website does not work on an old browser, a simpler, lightweight version of the site should be served instead. Machine learning systems are no different. Graceful failure is an important feature for critical systems that have the potential to bring down the availability of other systems. Security systems are frequently in the critical path, and there has to be a well-defined policy for how to deal with failure scenarios.

Should security systems fail open (allow requests through if the system fails to respond) or fail closed (block all requests if the system fails to respond)? This question cannot be answered without a comprehensive study of the application, weighing the risk and cost of an attack versus the cost of denying real users access to an application. For example, an authentication system will probably fail closed, because failing open would allow anybody to access the resources in question; an email spam detection system, on the other hand, will fail open, because blocking everyone’s email is much more costly than letting some spam through. In the general case, the cost of a breach vastly outweighs the cost of users being denied service, so security systems typically favor policies that define a fail-closed strategy. In some scenarios, however, this will make the system vulnerable to denial-of-service attacks, since attackers simply have to take down the security gateway to deny legitimate users access to the entire system.

Graceful degradation of security systems can also be achieved by having simpler backup systems in place. For instance, consider the case in which your website is experiencing heavy traffic volumes and your machine learning system that differentiates real human traffic from bot traffic is at risk of buckling under the stress. It may be wise to fall back to a more primitive and less resource-intensive strategy of CAPTCHAs until traffic returns to normal.

A well-thought-out strategy for ensuring continued system protection when security solutions fail is important because any loopholes in your security posture (e.g., decreased system availability) represent opportunities for attackers to get in.

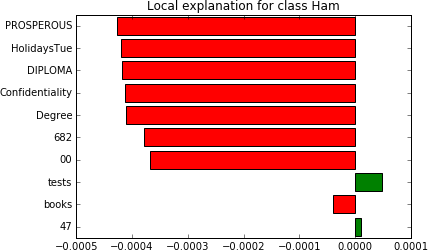

Goal: Easily Tunable and Configurable

Religious separation of code and configuration is a basic requirement for all production-quality software. This principle holds especially true for security machine learning systems. In the world of security operations, configurations to security systems often have to be tuned by security operations analysts, who don’t necessarily have a background in software development. Designing software and configuration that empowers such analysts to tune systems without the involvement of software engineers can significantly reduce the operational costs of such systems and make for a more versatile and flexible organization.