The importance of anomaly detection is not confined to the context of security. In a more general context, anomaly detection is any method for finding events that don’t conform to an expectation. For instances in which system reliability is of critical importance, you can use anomaly detection to identify early signs of system failure, triggering early or preventive investigations by operators. For example, if the power company can find anomalies in the electrical power grid and remedy them, it can potentially avoid expensive damage that occurs when a power surge causes outages in other system components. Another important application of anomaly detection is in the field of fraud detection. Fraud in the financial industry can often be fished out of a vast pool of legitimate transactions by studying patterns of normal events and detecting when deviations occur.

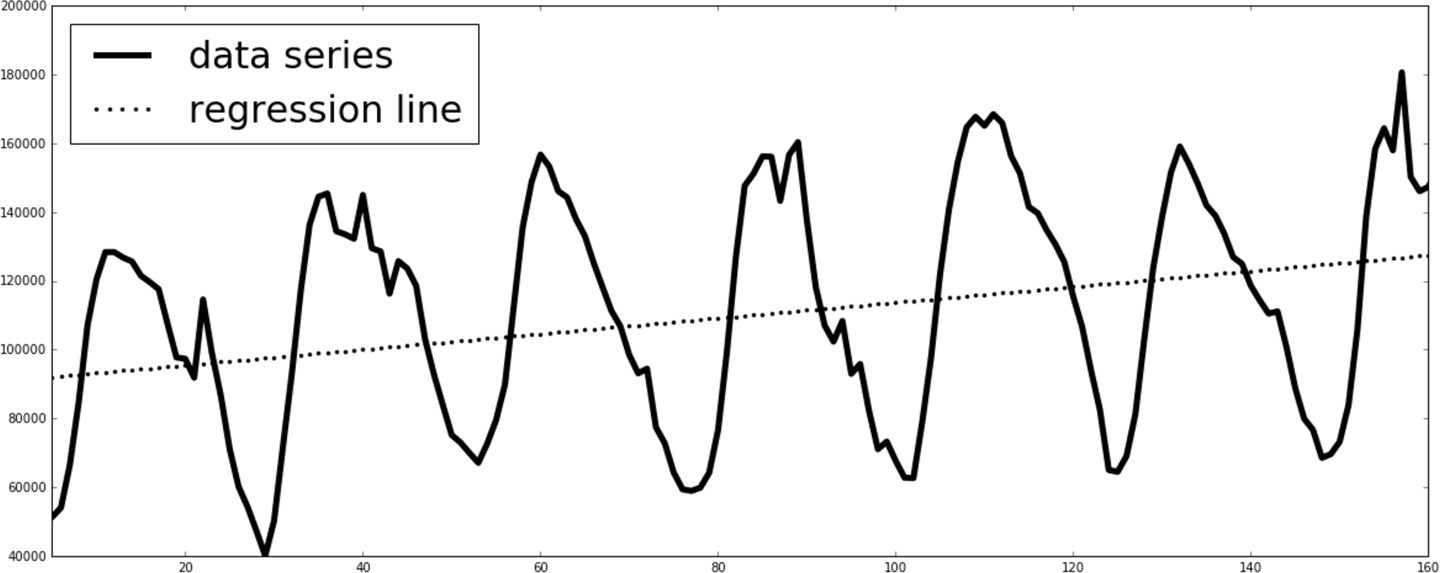

The study of anomaly detection is closely coupled with the concept of time series analysis because an anomaly is often defined as a deviation from what is normal or expected, given what had been observed in the past. Studying anomalies in the context of time thus makes a lot of sense. In the following pages we look at what anomaly detection is, examine the process of generating a time series, and discuss the techniques used to identify anomalies in a stream of data.

Response and Mitigation

After receiving an anomaly alert, what comes next? Incident response and threat mitigation are fields of practice that deserve their own publications, and we cannot possibly paint a complete picture of all the nuances and complexities involved. We can, however, consider how machine learning can be infused into traditional security operations workflows to improve the efficacy and yield of human effort.

Simple anomaly alerts can come in the form of an email or a mobile notification. In many cases, organizations that maintain a variety of different anomaly detection and security monitoring systems find value in aggregating alerts from multiple sources into a single platform known as a Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) system. SIEMs can help with the management of the output of fragmented security systems, which can quickly grow out of hand in volume. SIEMs can also correlate alerts raised by different systems to help analysts gather insights from a wide variety of security detection systems.

Having a unified location for reporting and alerting can also make a noticeable difference in the value of security alerts raised. Security alerts can often trigger action items for parts of the organization beyond the security team or even the engineering team. Many improvements to an organization’s security require coordinated efforts by cross-team management who do not necessarily have low-level knowledge of security operations. Having a platform that can assist with the generation of reports and digestible, human-readable insights into security incidents can be highly valuable when communicating the security needs of an organization to external stakeholders.

Incident response typically involves a human at the receiving end of security alerts, performing manual actions to investigate, verify, and escalate. Incident response is frequently associated with digital forensics (hence the field of digital forensics and incident response, or DFIR), which covers a large scope of actions that a security operations analyst must perform to triage alerts, collect evidence for investigations, verify the authenticity of collected data, and present the information in a format friendly to downstream consumers. Even as other areas of security adapt to more and more automation, incident response has remained a stubbornly manual process. For instance, there are tools that help with inspecting binaries and reading memory dumps, but there is no real substitute for a human hypothesizing about an attacker’s probable actions and intentions on a compromised host.

That said, machine-assisted incident response has shown significant promise. Machine learning can efficiently mine massive datasets for patterns and anomalies, whereas human analysts can make informed conjectures and perform complex tasks requiring deep contextual and experiential knowledge. Combining these sets of complementary strengths can potentially help improve the efficiency of incident response operations.

Threat mitigation is the process of reacting to intruders and attackers and preventing them from succeeding in their actions. A first reaction to an intrusion alert might be to nip the threat in the bud and prevent the risk from spreading any further. However, this action prevents you from collecting any further information about the attacker’s capabilities, intent, and origin. In an environment in which attackers can iterate quickly and pivot their strategies to circumvent detection, banning or blocking them can be counterproductive. The immediate feedback to the attackers can give them information about how they are being detected, allowing them to iterate to the point where they will be difficult to detect. Silently observing attackers while limiting their scope of damage is a better tactic, giving defenders more time to conceive a longer-term strategy that can stop attackers for good.

Stealth banning (or shadow banning, hell banning, ghost banning, etc.) is a practice adopted by social networks and online community platforms to block abusive or spam content precisely for the purpose of not giving these actors an immediate feedback loop. A stealth banning platform creates a synthetic environment visible to attackers after they are detected. This environment looks to the attacker like the normal platform, so they initially still thinks their actions are valid, when in fact anyone who has been stealth banned can cause no side effects nor be visible to other users or system components.

1 Dorothy Denning, “An Intrusion-Detection Model,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering SE-13:2 (1987): 222–232.

2 See chapter3/ids_heuristics_a.py in our code repository.

3 See chapter3/ids_heuristics_b.py in our code repository.

4 A kernel is a function that is provided to a machine learning algorithm that indicates how similar two inputs are. Kernels offer an alternate approach to feature engineering—instead of extracting individual features from the raw data, kernel functions can be efficiently computed, sometimes in high-dimensional space, to generate implicit features from the data that would otherwise be expensive to generate. The approach of efficiently transforming data into a high-dimensional, implicit feature space is known as the kernel trick. Chapter 2 provides more details.

5 You can find an example configuration file on GitHub.

6 Frédéric Cuppens et al., “Handling Stateful Firewall Anomalies,” Proceedings of the IFIP International Information Security Conference (2012): 174-186.

7 Ganesh Kumar Varadarajan, “Web Application Attack Analysis Using Bro IDS,” SANS Institute (2012).

8 Ralf Staudemeyer and Christian Omlin, “Extracting Salient Features for Network Intrusion Detection Using Machine Learning Methods,” South African Computer Journal 52 (2014): 82–96.

9 Alex Pinto, “Applying Machine Learning to Network Security Monitoring,” Black Hat webcast presented May 2014, http://ubm.io/2D9EUru.

10 Roger Meyer, “Detecting Attacks on Web Applications from Log Files,” SANS Institute (2008).

11 We use the terms “algorithm,” “method,” and “technique” interchangeably in this section, all referring to a single specific way of implementing anomaly detection; for example, a one-class SVM or elliptical envelope.

12 To be pedantic, autocorrelation is the correlation of the time series vector with the same vector shifted by some negative time delta.

13 Robert Nau of Duke University provides a great, detailed resource for forecasting, ARIMA, and more.

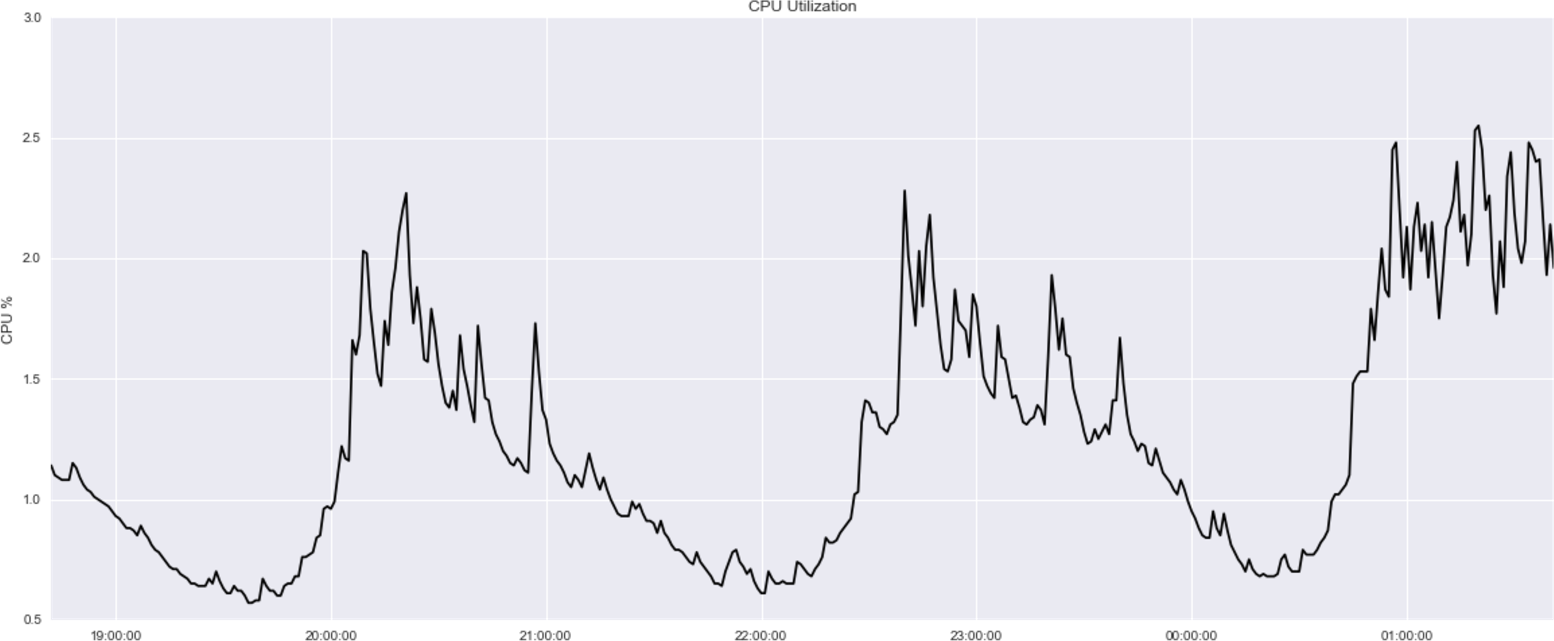

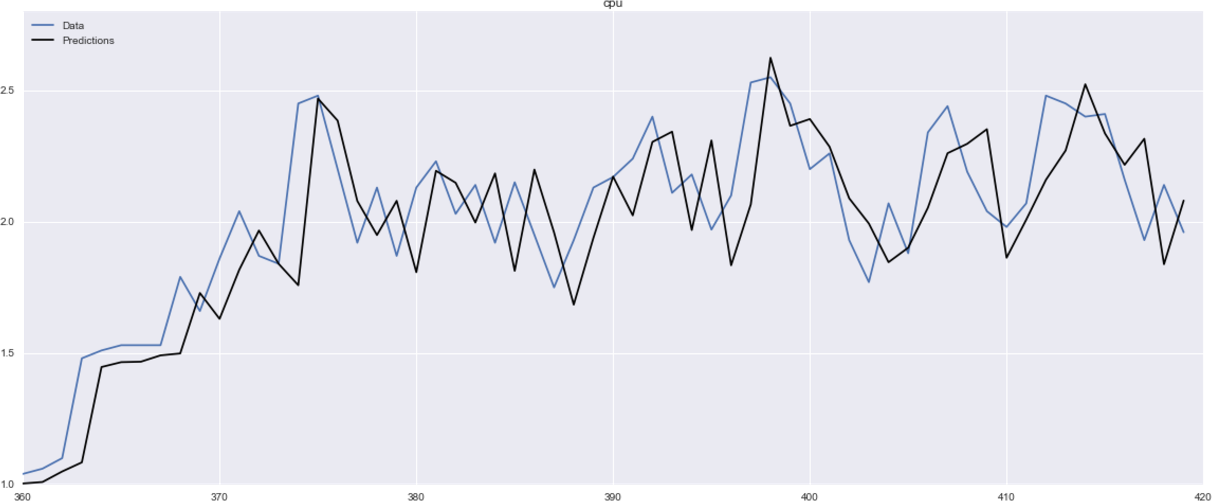

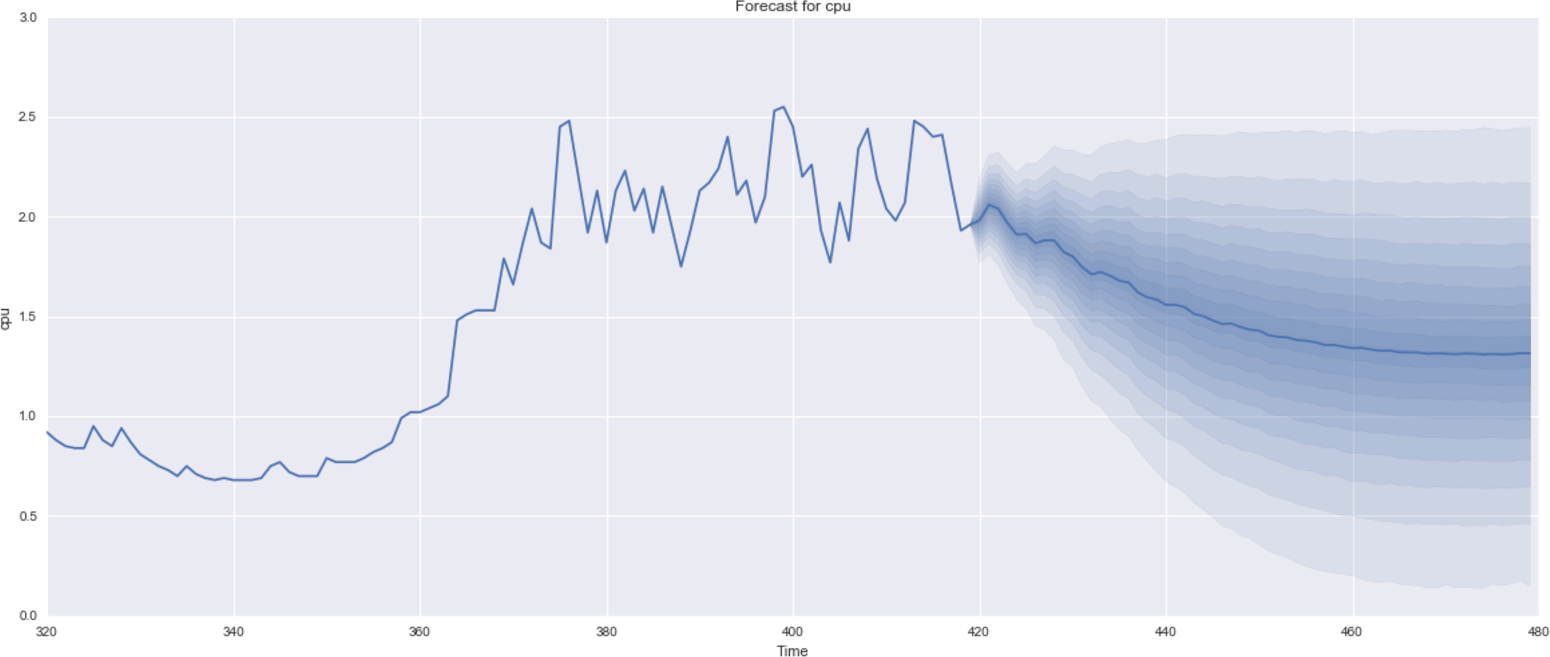

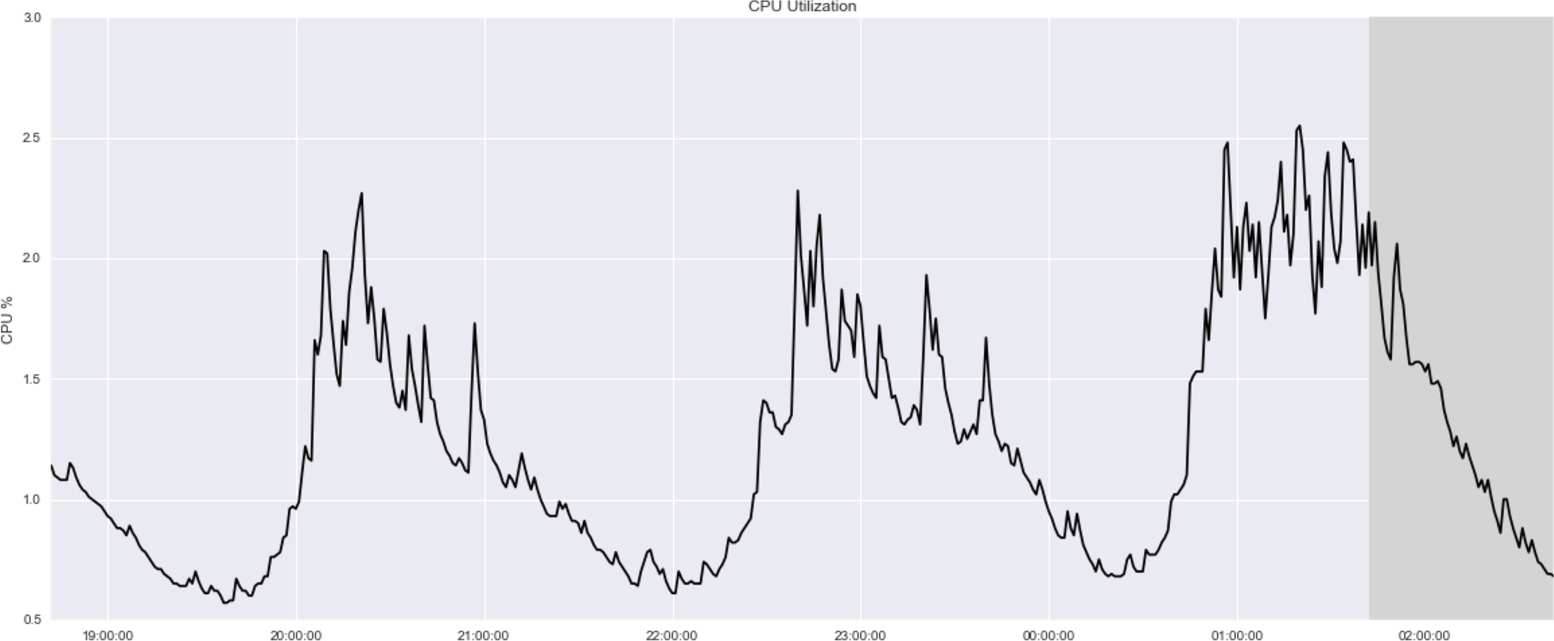

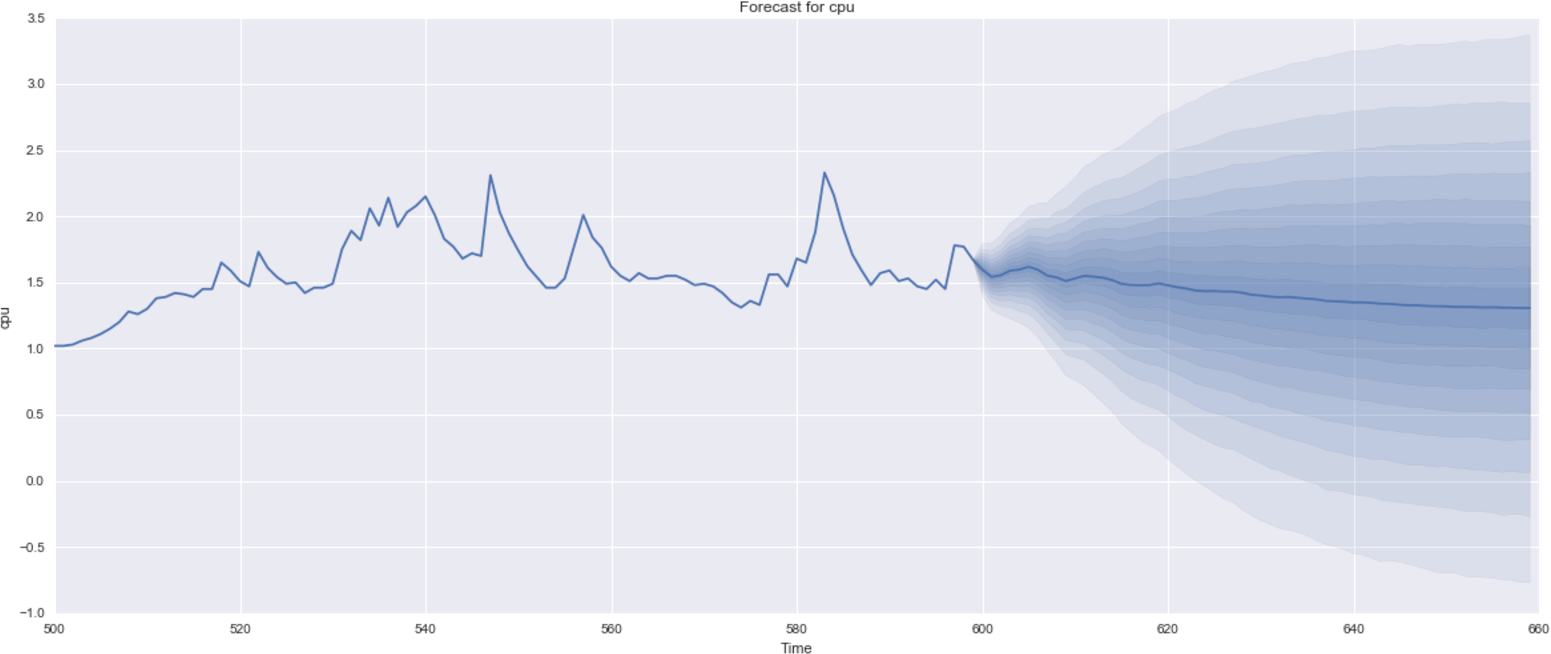

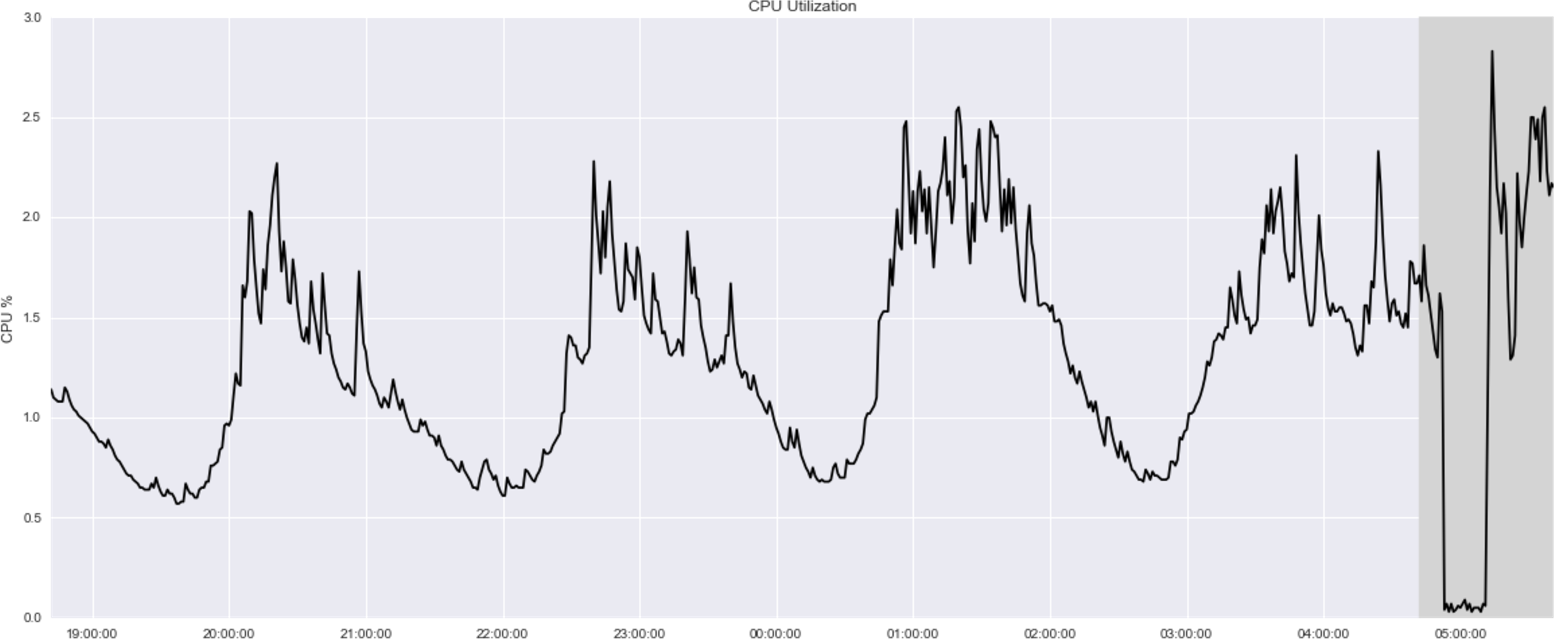

14 See chapter3/datasets/cpu-utilization in our code repository.

15 You can find documentation for PyFlux at http://www.pyflux.com/docs/arima.html?highlight=mle.

16 Full example code is given as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/arima-forecasting.ipynb in our code repository.

17 ARIMAX is a slight modification of ARIMA that adds components originating from standard econometrics, known as explanatory variables, to the prediction models.

18 Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber, “Long Short-Term Memory,” Neural Computation 9 (1997): 1735–1780.

19 Alex Graves, “Generating Sequences with Recurrent Neural Networks”, University of Toronto (2014).

20 Neural networks are made up of layers of individual units. Data is fed into the input layer and predictions are produced from the output layer. In between, there can be an arbitrary number of hidden layers. In counting the number of layers in a neural network, a widely accepted convention is to not count the input layer. For example, in a six-layer neural network, we have one input layer, five hidden layers, and one output layer.

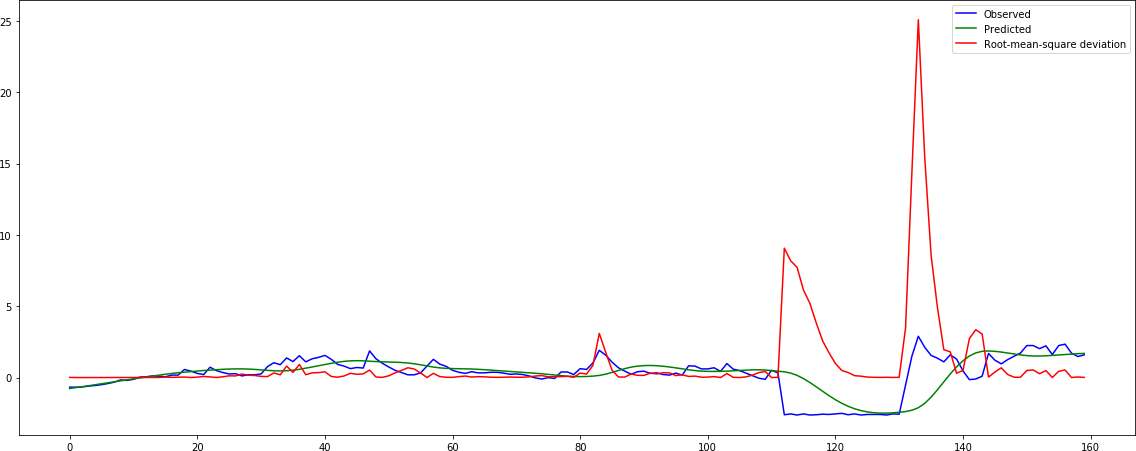

21 Full example code is given as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/lstm-anomaly-detection.ipynb in our code repository.

22 Nitish Srivastava et al., “Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting,” Journal of Machine Learning Research 15 (2014): 1929−1958.

23 Eamonn Keogh and Jessica Lin, “Clustering of Time-Series Subsequences Is Meaningless: Implications for Previous and Future Research,” Knowledge and Information Systems 8 (2005): 154–177.

24 This example can be found at chapter3/mad.py in our code repository.

25 The law of large numbers is a theorem that postulates that repeating an experiment a large number of times will produce a mean result that is close to the expected value.

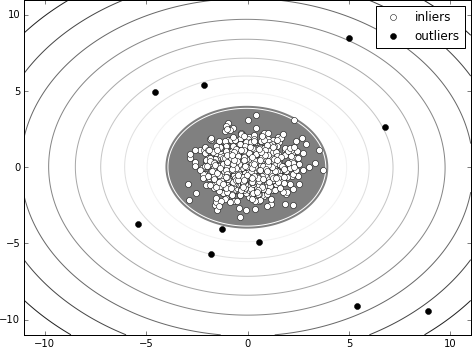

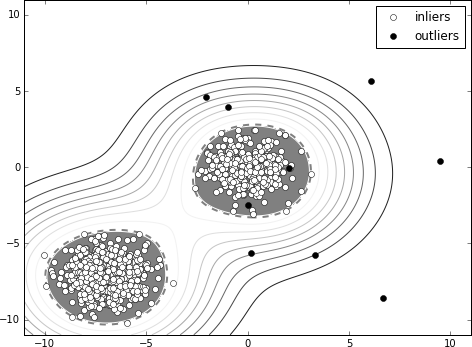

26 The full code can be found as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/elliptic-envelope-fitting.ipynb in our code repository.

27 In statistics, robust is a property that is used to describe a resilience to outliers. More generally, the term robust statistics refers to statistics that are not strongly affected by certain degrees of departures from model assumptions.

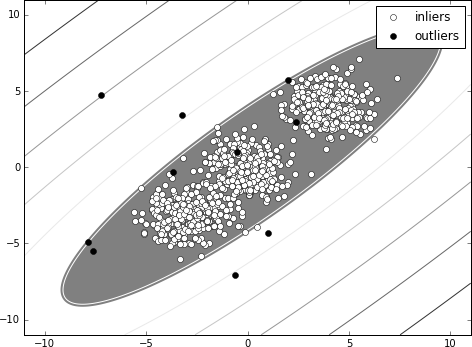

28 The full code can be found as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/one-class-svm.ipynb in our code repository.

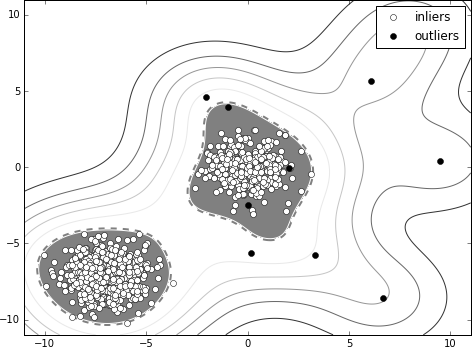

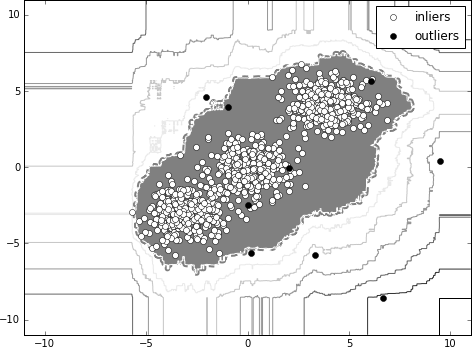

29 The full code can be found as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/isolation-forest.ipynb in our code repository.

30 Alexandr Andoni and Piotr Indyk, “Nearest Neighbors in High-Dimensional Spaces,” in Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry, 3rd ed., ed. Jacob E. Goodman, Joseph O’Rourke, and Piotr Indyk (CRC Press).

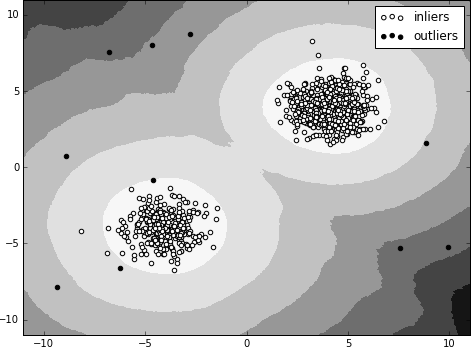

31 The full code can be found as a Python Jupyter notebook at chapter3/local-outlier-factor.ipynb in our code repository.

32 In Chapter 7, we examine the details of dealing with explainability in machine learning in more depth.

33 Ryan Turner, “A Model Explanation System”, Black Box Learning and Inference NIPS Workshop (2015).