In this book, Harry takes us on an adventure of discovery with Python and testing. It’s an excellent book, fun to read and full of vital information. It has my highest recommendations for anyone interested in testing with Python, learning Django, or wanting to use Selenium. Testing is essential for developer sanity and it’s a notoriously difficult field, full of trade-offs. Harry does a fantastic job of holding our attention whilst exploring real-world testing practices.

Michael Foord, Python Core Developer and Maintainer of unittest

This book is far more than an introduction to test-driven development—it’s a complete best-practices crash course, from start to finish, into modern web application development with Python. Every web developer needs this book.

Kenneth Reitz, Fellow at Python Software Foundation

Harry’s book is what we wish existed when we were learning Django. At a pace that’s achievable and yet delightfully challenging, it provides excellent instruction for Django and various test practices. The material on Selenium alone makes the book worth purchasing, but there’s so much more!

Daniel and Audrey Roy Greenfeld, authors of Two Scoops of Django (Two Scoops Press)

Obey the Testing Goat: Using Django, Selenium, and JavaScript

Second Edition

Copyright © 2017 Harry Percival. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491958704 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Test-Driven Development with Python, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-491-95870-4

[LSI]

This book is my attempt to share with the world the journey I’ve taken from “hacking” to “software engineering”. It’s mainly about testing, but there’s a lot more to it, as you’ll soon see.

I want to thank you for reading it.

If you bought a copy, then I’m very grateful. If you’re reading the free online version, then I’m still grateful that you’ve decided it’s worth spending some of your time on. Who knows, perhaps once you get to the end, you’ll decide it’s good enough to buy a real copy for yourself or for a friend.

If you have any comments, questions, or suggestions, I’d love to hear from you. You can reach me directly via obeythetestinggoat@gmail.com, or on Twitter @hjwp. You can also check out the website and my blog, and there’s a mailing list.

I hope you’ll enjoy reading this book as much as I enjoyed writing it.

“Who are you, why are you writing this book, and why should I read it?” I hear you ask.

I’m still quite early on in my programming career. They say that in any discipline, you go from apprentice, to journeyman, and eventually, sometimes, on to master. I’d say that I’m—at best—a journeyman programmer. But I was lucky enough, early on in my career, to fall in with a bunch of TDD fanatics, and it made such a big impact on my programming that I’m burning to share it with everyone. You might say I have the enthusiasm of a recent convert, and the learning experience is still a recent memory for me, so I hope I can still empathise with beginners.

When I first learned Python (from Mark Pilgrim’s excellent Dive Into Python), I came across the concept of TDD, and thought “Yes. I can definitely see the sense in that.” Perhaps you had a similar reaction when you first heard about TDD? It sounds like a really sensible approach, a really good habit to get into—like regularly flossing your teeth.

Then came my first big project, and you can guess what happened—there was a client, there were deadlines, there was lots to do, and any good intentions about TDD went straight out of the window.

And, actually, it was fine. I was fine.

At first.

At first I knew I didn’t really need TDD because it was a small website, and I could easily test whether things worked by just manually checking it out. Click this link here, choose that drop-down item there, and this should happen. Easy. This whole writing tests thing sounded like it would have taken ages, and besides, I fancied myself, from the full height of my three weeks of adult coding experience, as being a pretty good programmer. I could handle it. Easy.

Then came the fearful goddess Complexity. She soon showed me the limits of my experience.

The project grew. Parts of the system started to depend on other parts. I did

my best to follow good principles like DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), but that

just led to some pretty dangerous territory. Soon I was playing with multiple

inheritance. Class hierarchies eight levels deep. eval statements.

I became scared of making changes to my code. I was no longer sure what depended on what, and what might happen if I changed this code over here, oh gosh, I think that bit over there inherits from it—no, it doesn’t, it’s overriden. Oh, but it depends on that class variable. Right, well, as long as I override the override it should be fine. I’ll just check—but checking was getting much harder. There were lots of sections to the site now, and clicking through them all manually was starting to get impractical. Better to leave well enough alone, forget refactoring, just make do.

Soon I had a hideous, ugly mess of code. New development became painful.

Not too long after this, I was lucky enough to get a job with a company called Resolver Systems (now PythonAnywhere), where Extreme Programming (XP) was the norm. They introduced me to rigorous TDD.

Although my previous experience had certainly opened my mind to the possible benefits of automated testing, I still dragged my feet at every stage. “I mean, testing in general might be a good idea, but really? All these tests? Some of them seem like a total waste of time… What? Functional tests as well as unit tests? Come on, that’s overdoing it! And this TDD test/minimal-code-change/test cycle? This is just silly! We don’t need all these baby steps! Come on, we can see what the right answer is, why don’t we just skip to the end?”

Believe me, I second-guessed every rule, I suggested every shortcut, I demanded justifications for every seemingly pointless aspect of TDD, and I came out seeing the wisdom of it all. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve thought “Thanks, tests”, as a functional test uncovers a regression we would never have predicted, or a unit test saves me from making a really silly logic error. Psychologically, it’s made development a much less stressful process. It produces code that’s a pleasure to work with.

So, let me tell you all about it!

My main aim is to impart a methodology—a way of doing web development, which I think makes for better web apps and happier developers. There’s not much point in a book that just covers material you could find by Googling, so this book isn’t a guide to Python syntax, or a tutorial on web development per se. Instead, I hope to teach you how to use TDD to get more reliably to our shared, holy goal: clean code that works.

With that said: I will constantly refer to a real practical example, by building a web app from scratch using tools like Django, Selenium, jQuery, and Mocks. I’m not assuming any prior knowledge of any of these, so you should come out of the other end of this book with a decent introduction to those tools, as well as the discipline of TDD.

In Extreme Programming we always pair-program, so I’ve imagined writing this book as if I was pairing with my previous self, having to explain how the tools work and answer questions about why we code in this particular way. So, if I ever take a bit of a patronising tone, it’s because I’m not all that smart, and I have to be very patient with myself. And if I ever sound defensive, it’s because I’m the kind of annoying person that systematically disagrees with whatever anyone else says, so sometimes it takes a lot of justifying to convince myself of anything.

I’ve split this book into three parts.

Dives straight into building a simple web app using TDD. We start by writing a functional test (with Selenium), and then we go through the basics of Django—models, views, templates—with rigorous unit testing at every stage. I also introduce the Testing Goat.

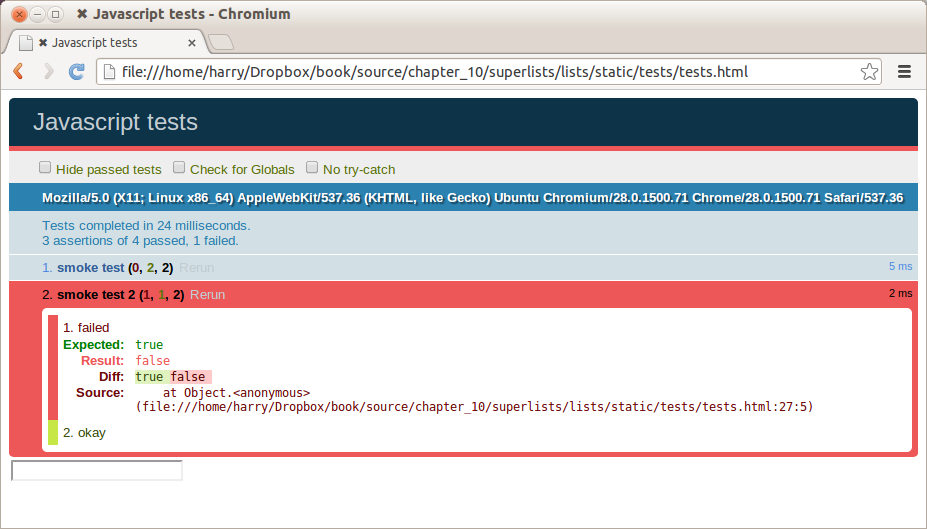

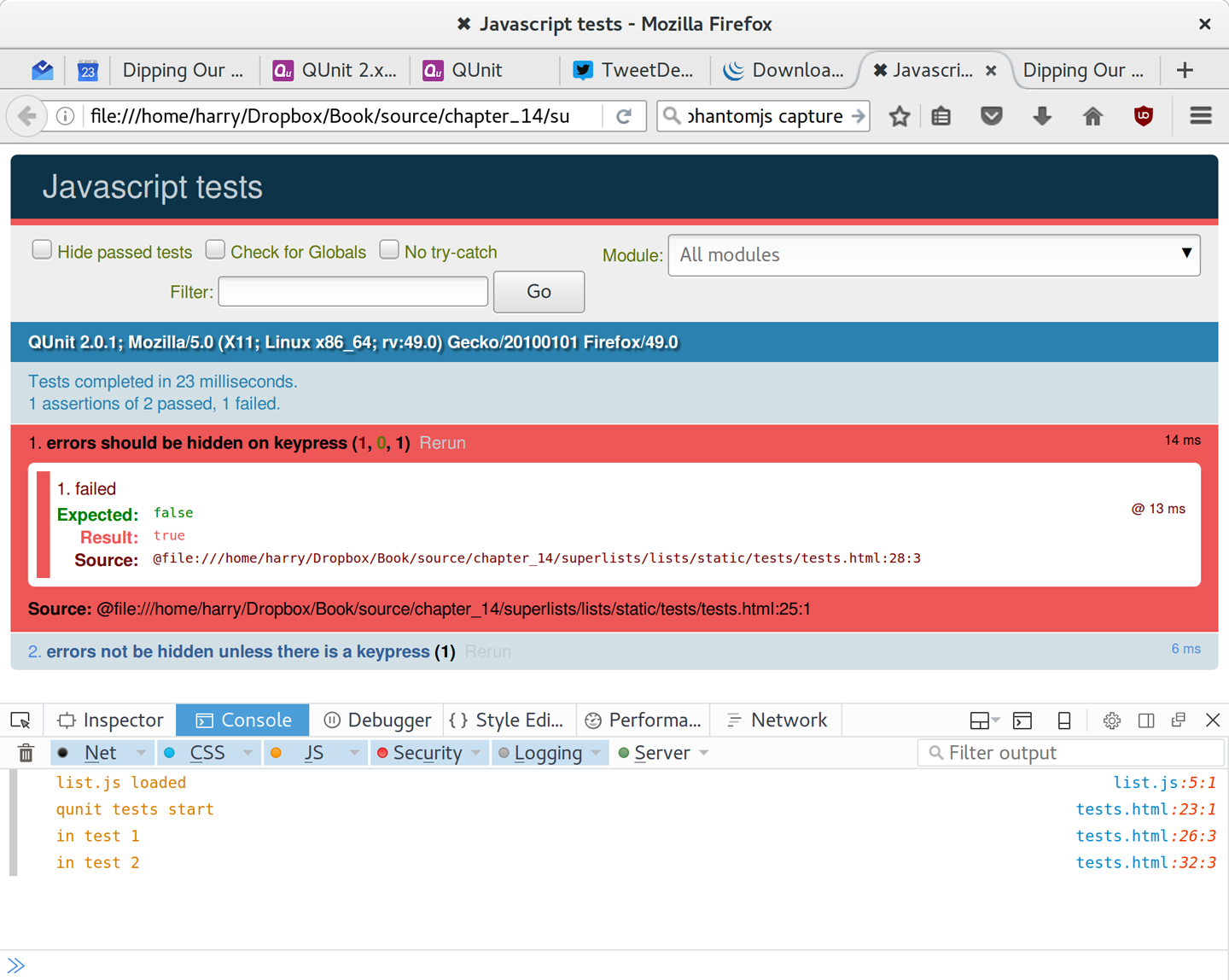

Covers some of the trickier but unavoidable aspects of web development, and shows how testing can help us with them: static files, deployment to production, form data validation, database migrations, and the dreaded JavaScript.

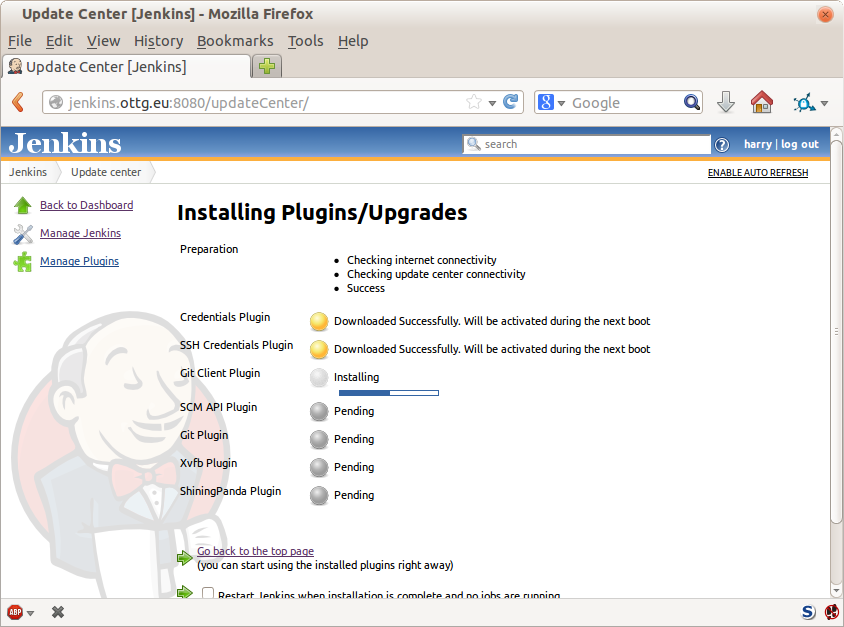

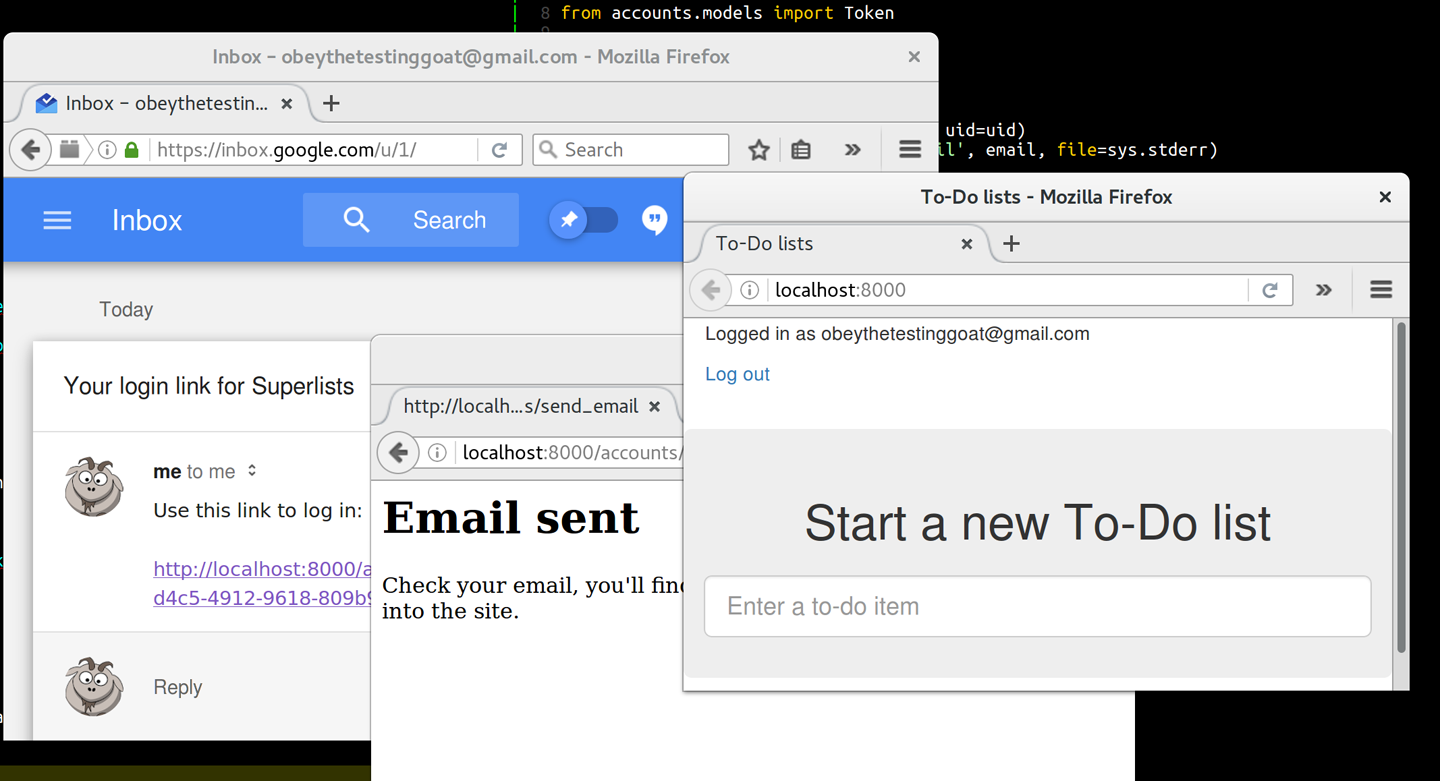

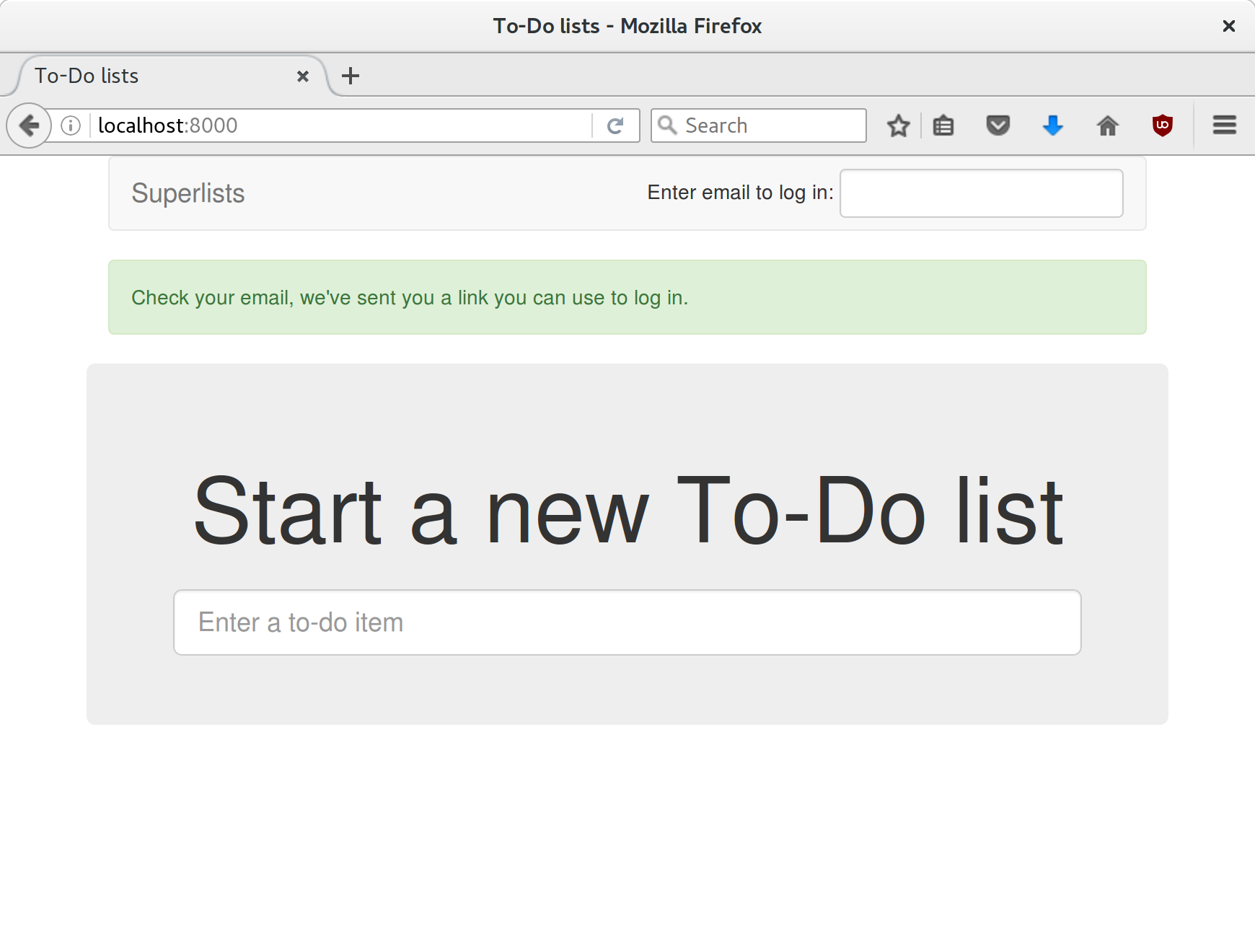

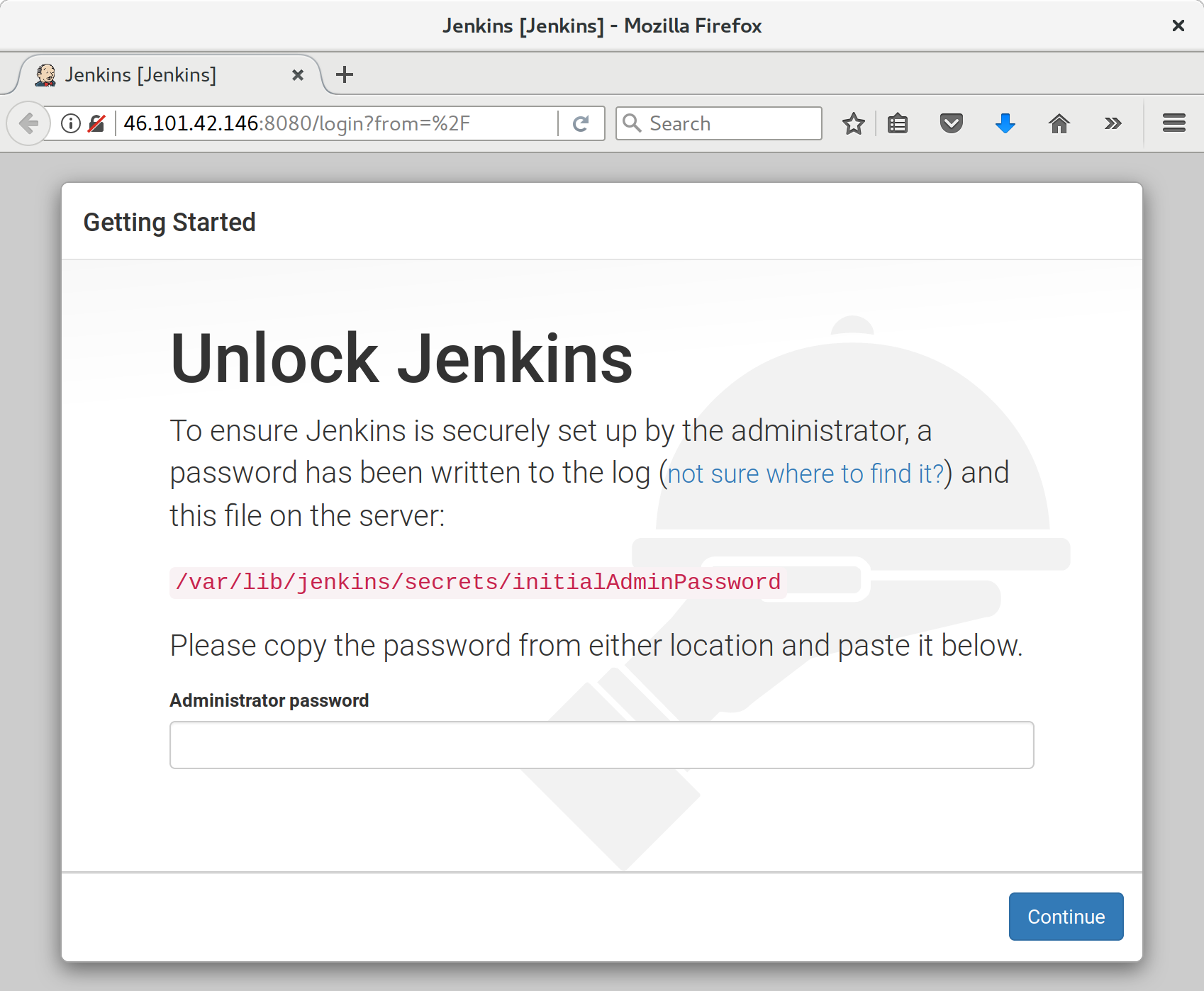

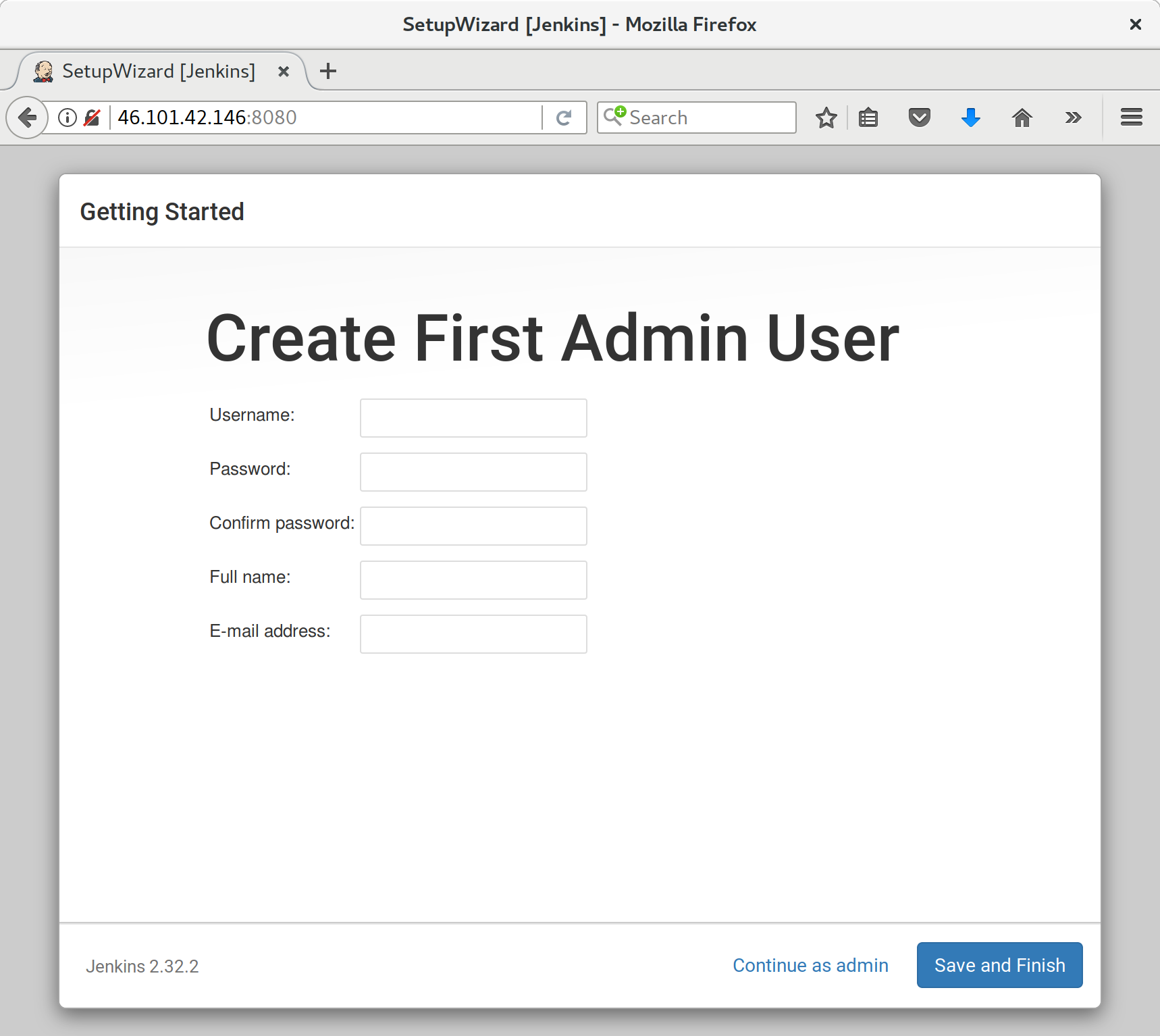

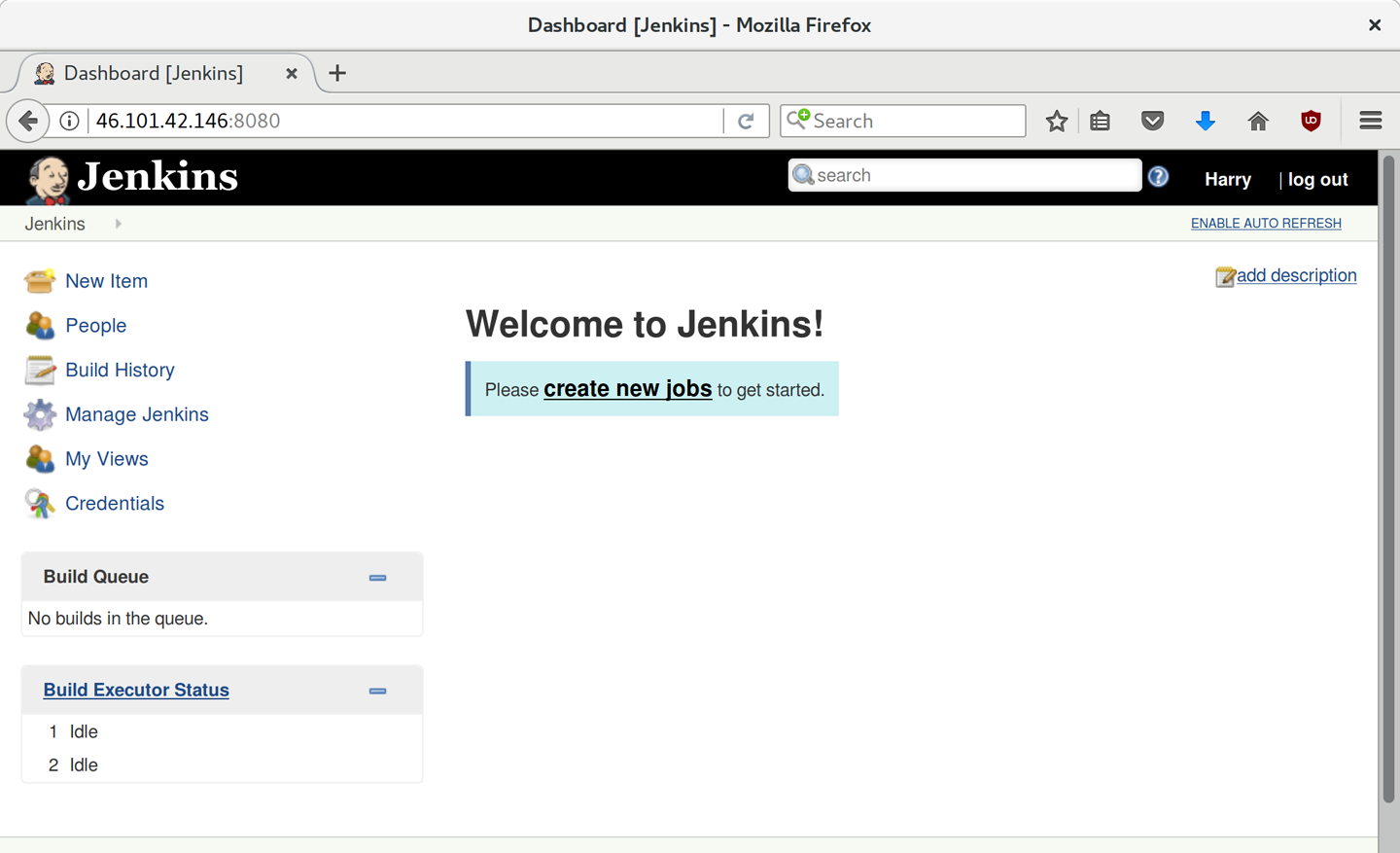

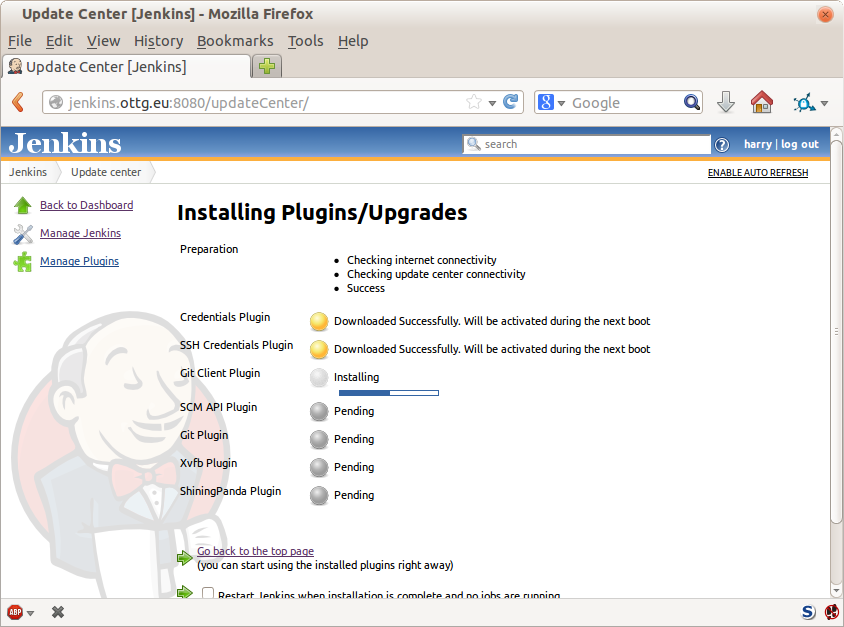

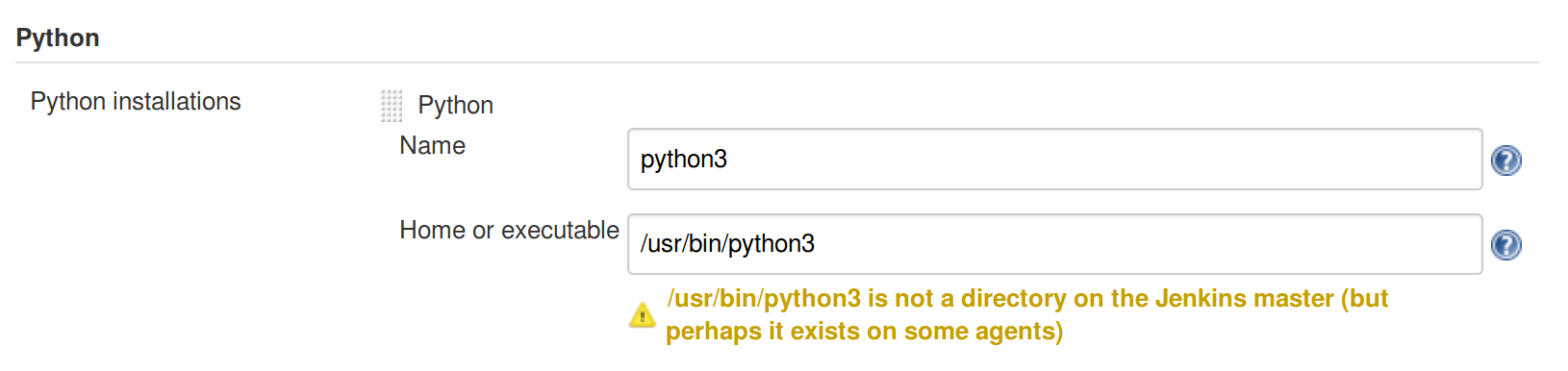

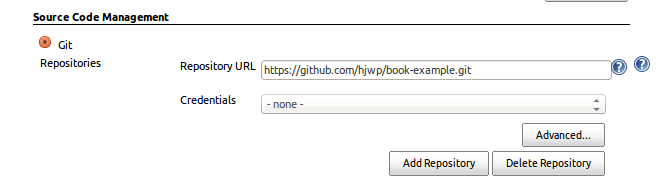

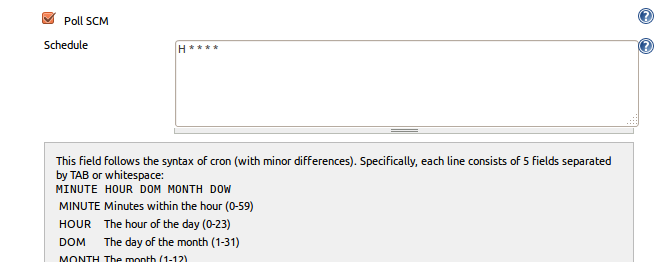

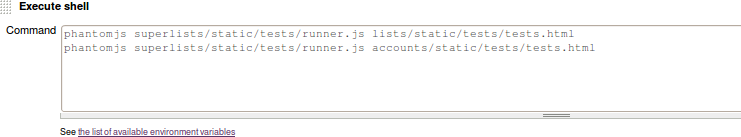

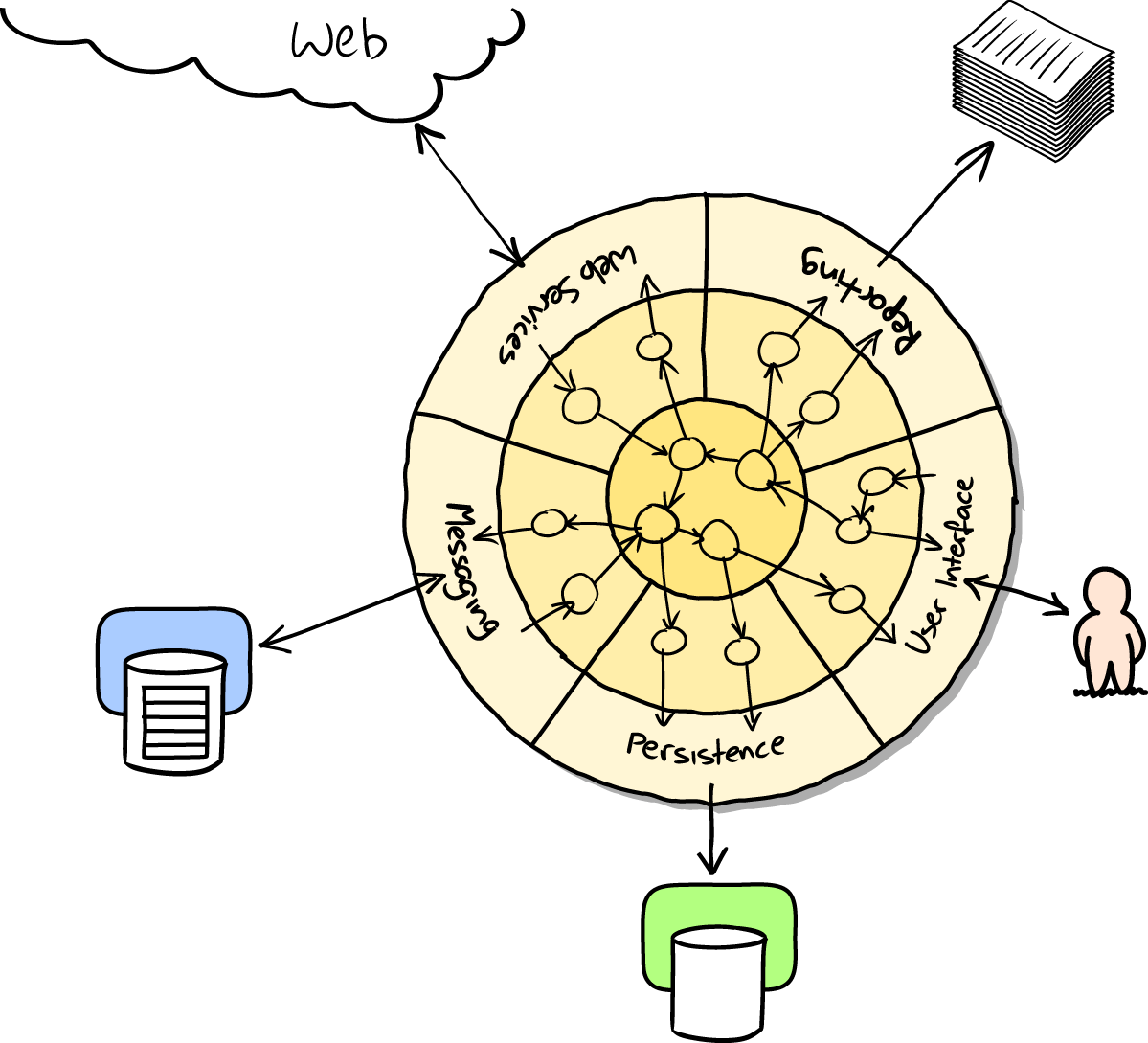

Mocking, integrating a third-party system, test fixtures, Outside-In TDD, and Continuous Integration (CI).

On to a little housekeeping…

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Occasionally I will use the symbol:

[...]

to signify that some of the content has been skipped, to shorten long bits of output, or to skip down to a relevant section.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note or aside.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Spotted a mistake or a typo? The sources for this book are available on GitHub, and I’m always very happy to receive issues and pull requests: https://github.com/hjwp/Book-TDD-Web-Dev-Python/.

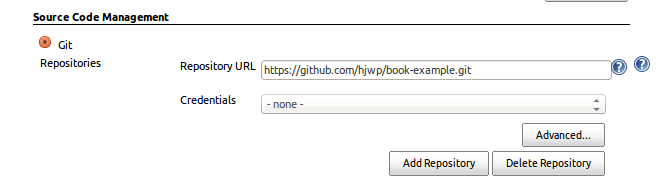

Code examples are available at https://github.com/hjwp/book-example/; you’ll find branches for each chapter there (e.g., https://github.com/hjwp/book-example/tree/chapter_unit_test_first_view). You’ll find a full list, and some suggestions on ways of working with this repository, in Appendix J.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Test-Driven Development with Python, 2nd edition, by Harry J.W. Percival (O’Reilly). Copyright 2017 Harry Percival, 978-1-491-95870-4.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

If you’d like to get in touch with my beloved publisher with any questions about this book, contact details follow:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/tdd_py_2e.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about books, courses, conferences, and news, see O’Reilly’s website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Here’s an outline of what I’m assuming about you and what you already know, as well as what software you’ll need ready and installed on your computer.

I’ve tried to write this book with beginners in mind, but if you’re new to programming, I’m assuming that you’ve already learned the basics of Python. So if you haven’t already, do run through a Python beginner’s tutorial or get an introductory book like Dive Into Python or Learn Python the Hard Way, or, just for fun, Invent Your Own Computer Games with Python, all of which are excellent introductions.

If you’re an experienced programmer but new to Python, you should get along just fine. Python is joyously simple to understand.

I’m using Python 3 for this book. When I wrote the first edition in 2013–14, Python 3 had been around for several years, and the world was just about on the tipping point at which it was the preferred choice. You should be able to follow this book on Mac, Windows, or Linux. Detailed installation instructions for each OS follow.

This book was tested against Python 3.6. If you’re on an earlier version, you will find minor differences (the f-string syntax, for example), so you’re best off upgrading if you can.

I wouldn’t recommend trying to use Python 2, as the differences are more substantial. You’ll still be able to carry across all the lessons you learn in this book if your next project happens to be in Python 2. But spending time figuring out whether the reason your program output looks different from mine is because of Python 2, or because you made an actual mistake, won’t be time spent productively.

If you are thinking of using PythonAnywhere (the PaaS startup I work for), rather than a locally installed Python, you should go and take a quick look at Appendix A before you get started.

In any case, I expect you to have access to Python, to know how to launch it from a command line, and to know how to edit a Python file and run it. Again, have a look at the three books I recommended previously if you’re in any doubt.

If you already have Python 2 installed, and you’re worried that installing Python 3 will break it in some way, don’t! Python 3 and 2 can coexist peacefully on the same system, particularly if you’re using a virtualenv, which we will be.

I’m also assuming you have a basic grasp of how the web works—what HTML is, what a POST request is, and so on. If you’re not sure about those, you’ll need to find a basic HTML tutorial; there are a few at http://www.webplatform.org/. If you can figure out how to create an HTML page on your PC and look at it in your browser, and understand what a form is and how it might work, then you’re probably OK.

The book uses the Django framework, which is (probably) the most well-established web framework in the Python world. I’ve written the book assuming that the reader has no prior knowledge of Django, but if you’re new to Python and new to web development and new to testing, you may occasionally find that there’s just one too many topics and sets of concepts to try and take on board. If that’s the case, I recommend taking a break from the book, and taking a look at a Django tutorial. DjangoGirls is the best, most beginner-friendly tutorial I know of. The official tutorial is also excellent for more experienced programmers (make sure you follow the 1.11 tutorial rather than a 2.x one though).

This book was published before Django 2.0 came out, and as such is written for Django v1.11 (which is an “long-term-support” or LTS edition). If you’re keen to use Django 2, I strongly recommend doing so after you’ve read this book, in your own projects, rather than installing it now and trying to adapt as you go along. Django hasn’t changed that much, but when things look different on your own PC from what the book says should happen, you’ll waste time trying to figure out whether it’s because Django has changed, or because you’ve made a mistake.

Read on for instructions on installing Django.

There’s a little bit of JavaScript in the second half of the book. If you don’t know JavaScript, don’t worry about it until then, and if you find yourself a little confused, I’ll recommend a couple of guides at that point.

Aside from Python, you’ll need:

Selenium can actually drive any of the major browsers, but Firefox is the best to use as an example because it’s reliably cross-platform and, as a bonus, is less sold out to corporate interests.

This is available for any platform, at http://git-scm.com/. On Windows, this comes with the Bash command line, which is needed for the book.

Python’s virtualenv and pip tools now come bundled with Python 3.4+ (they didn’t always used to, so this is a big hooray). Detailed instructions for preparing your virtualenv follow.

This is the driver that will let us remotely control Firefox via Selenium. I’ll point to a download link in “Installing Firefox and Geckodriver”.

I’ll

provide step-by-step instructions for Git, but it may be a good idea to

get a bit of configuration done now. For example, when you do your first

commit, by default vi will pop up, at which point you may have no idea what

to do with it. Well, much as vi has two modes, you then have two choices. One

is to learn some minimal vi commands (press the i key to go into insert mode,

type your text, press <Esc> to go back to normal mode, then write the file

and quit with :wq<Enter>). You’ll then have joined the great fraternity of

people who know this ancient, revered text editor.

Or you can point-blank refuse to be involved in such a ridiculous throwback to

the 1970s, and configure Git to use an editor of your choice. Quit vi using

<Esc> followed by :q!, then change your Git default editor. See the Git

documentation on

basic Git configuration.

Firefox is available as a download for Windows and macOS from https://www.mozilla.org/firefox/. On Linux, you probably already have it installed, but otherwise your package manager will have it.

Geckodriver is available from https://github.com/mozilla/geckodriver/releases. You need to download and extract it and put it somewhere on your system path.

For Windows, you can just put it in the same folder as your code for this book—or if you put it in your Python Scripts folder, it’ll be available for other projects.

For macOS or Linux, one convenient place to put it is /usr/local/bin

(you’ll need sudo for this).

To test that you’ve got this working, open up a Bash console and you should be able to run:

$ geckodriver --version geckodriver 0.19.1 The source code of this program is available at https://github.com/mozilla/geckodriver. This program is subject to the terms of the Mozilla Public License 2.0. You can obtain a copy of the license at https://mozilla.org/MPL/2.0/.

A Python virtualenv (short for virtual environment) is how you set up your environment for different Python projects. It allows you to use different packages (e.g., different versions of Django, and even different versions of Python) in each project. And because you’re not installing things system-wide, it means you don’t need root permissions.

Let’s create a Python 3 virtualenv called “superlists”.2 I’m assuming you’re working in a folder called python-tdd-book, but you can name your work folder whatever you like. Stick to the name “virtualenv” for the virtualenv, though.

$ cd python-tdd-book $ py -3.6 -m venv virtualenv

On Windows, the py executable is a shortcut for different Python versions. On

Mac or Linux, we use python3.6:

$ cd python-tdd-book $ python3.6 -m venv virtualenv

Whenever you work on the book, you’ll want to make sure your virtualenv has

been “activated”. You can always tell when your virtualenv is active because

you’ll see (virtualenv) in parentheses, in your prompt. But you can

also check by running which python to check whether Python is currently

the system-installed one, or the virtualenv one.

The command to activate the virtualenv is source virtualenv/Scripts/activate on

Windows and source virtualenv/bin/activate on Mac/Linux. The command to

deactivate is just deactivate.

Try it out like this:

$ source virtualenv/Scripts/activate (virtualenv)$ (virtualenv)$ which python /C/Users/harry/python-tdd-book/virtualenv/Scripts/python (virtualenv)$ deactivate $ $ which python /c/Users/harry/AppData/Local/Programs/Python/Python36-32/python

$ source virtualenv/bin/activate (virtualenv)$ (virtualenv)$ which python /home/myusername/python-tdd-book/virtualenv/bin/python (virtualenv)$ deactivate $ $ which python /usr/bin/python

Always make sure your virtualenv is active when working on the book. Look

out for the (virtualenv) in your prompt, or run which python to check.

We’ll install Django 1.11 and the latest Selenium, Selenium 3.

Remember to make sure your virtualenv is active first!

(virtualenv) $ pip install "django<1.12" "selenium<4" Collecting django==1.11.8 Using cached Django-1.11.8-py2.py3-none-any.whl Collecting selenium<4 Using cached selenium-3.9.0-py2.py3-none-any.whl Installing collected packages: django, selenium Successfully installed django-1.11.8 selenium-3.9.0

If you’re new to virtualenvs—or even if you’re not, to be honest—at some point you’re guaranteed to forget to activate it, and then you’ll be staring at an error message. Happens to me all the time. Here are some of the things to look out for:

ImportError: No module named selenium

Or:

ImportError: No module named django.core.management

As always, look out for that (virtualenv) in your command prompt, and a

quick source virtualenv/Scripts/activate or source

virtualenv/bin/activate is probably what you need to get it working again.

Here’s a couple more, for good measure:

bash: virtualenv/Scripts/activate: No such file or directory

This means you’re not currently in the right directory for working on the

project. Try a cd tdd-python-book, or similar.

Alternatively, if you’re sure you’re in the right place, you may have run into a bug from an older version of Python, where it wouldn’t install an activate script that was compatible with Git-Bash. Reinstall Python 3, and make sure you have version 3.6.3 or later, and then delete and re-create your virtualenv.

If you see something like this, it’s probably the same issue, you need to upgrade Python:

bash: @echo: command not found

bash: virtualenv/Scripts/activate.bat: line 4:

syntax error near unexpected token `(

bash: virtualenv/Scripts/activate.bat: line 4: `if not defined PROMPT ('

Final one! If you see this:

'source' is not recognized as an internal or external command, operable program or batch file.

It’s because you’ve launched the default Windows command prompt, cmd,

instead of Git-Bash. Close it and open the latter.

Did these instructions not work for you? Or have you got better ones? Get in touch: obeythetestinggoat@gmail.com!

1 I wouldn’t recommend installing Firefox via Homebrew though: brew puts the Firefox binary in a strange location, and it confuses Selenium. You can work around it, but it’s simpler to just install Firefox in the normal way.

2 Why superlists, I hear you ask? No spoilers! You’ll find out in the next chapter.

I’ve recorded a 10-part video series to accompany this book.1 It covers the content of Part I. If you find you learn well from video-based material, then I encourage you to check it out. Over and above what’s in the book, it should give you a feel for what the “flow” of TDD is like, flicking between tests and code, explaining the thought process as we go.

Plus I’m wearing a delightful yellow T-shirt.

1 The video has not been updated for the second edition, but the content is all mostly the same.

Lots of people to thank, without whom this book would never have happened, and/or would have been even worse than it is.

Thanks first to “Greg” at $OTHER_PUBLISHER, who was the first person to encourage me to believe it really could be done. Even though your employers turned out to have overly regressive views on copyright, I’m forever grateful that you believed in me.

Thanks to Michael Foord, another ex-employee of Resolver Systems, for providing the original inspiration by writing a book himself, and thanks for his ongoing support for the project. Thanks also to my boss Giles Thomas, for foolishly allowing another one of his employees to write a book (although I believe he’s now changed the standard employment contract to say “no books”). Thanks also for your ongoing wisdom and for setting me off on the testing path.

Thanks to my other colleagues, Glenn Jones and Hansel Dunlop, for being invaluable sounding boards, and for your patience with my one-track record conversation over the last year.

Thanks to my wife Clementine, and to both my families, without whose support and patience I would never have made it. I apologise for all the time spent with nose in computer on what should have been memorable family occasions. I had no idea when I set out what the book would do to my life (“Write it in my spare time, you say? That sounds reasonable…”). I couldn’t have done it without you.

Thanks to my tech reviewers, Jonathan Hartley, Nicholas Tollervey, and Emily Bache, for your encouragements and invaluable feedback. Especially Emily, who actually conscientiously read every single chapter. Partial credit to Nick and Jon, but that should still be read as eternal gratitude. Having y’all around made the whole thing less of a lonely endeavour. Without all of you the book would have been little more than the nonsensical ramblings of an idiot.

Thanks to everyone else who’s given up some of their time to give some feedback on the book, out of nothing more than the goodness of their heart: Gary Bernhardt, Mark Lavin, Matt O’Donnell, Michael Foord, Hynek Schlawack, Russell Keith-Magee, Andrew Godwin, Kenneth Reitz, and Nathan Stocks. Thanks for being much smarter than I am, and for preventing me from saying several stupid things. Naturally, there are still plenty of stupid things left in the book, for which y’all can absolutely not be held responsible.

Thanks to my editor Meghan Blanchette, for being a very friendly and likeable slave driver, and for keeping the book on track, both in terms of timescales and by restraining my sillier ideas. Thanks to all the others at O’Reilly for your help, including Sarah Schneider, Kara Ebrahim, and Dan Fauxsmith for letting me keep British English. Thanks to Charles Roumeliotis for your help with style and grammar. We may never see eye-to-eye on the merits of Chicago School quotation/punctuation rules, but I sure am glad you were around. And thanks to the design department for giving us a goat for the cover!

And thanks most especially to all my Early Release readers, for all your help picking out typos, for your feedback and suggestions, for all the ways in which you helped to smooth out the learning curve in the book, and most of all for your kind words of encouragement and support that kept me going. Thank you Jason Wirth, Dave Pawson, Jeff Orr, Kevin De Baere, crainbf, dsisson, Galeran, Michael Allan, James O’Donnell, Marek Turnovec, SoonerBourne, julz, Cody Farmer, William Vincent, Trey Hunner, David Souther, Tom Perkin, Sorcha Bowler, Jon Poler, Charles Quast, Siddhartha Naithani, Steve Young, Roger Camargo, Wesley Hansen, Johansen Christian Vermeer, Ian Laurain, Sean Robertson, Hari Jayaram, Bayard Randel, Konrad Korżel, Matthew Waller, Julian Harley, Barry McClendon, Simon Jakobi, Angelo Cordon, Jyrki Kajala, Manish Jain, Mahadevan Sreenivasan, Konrad Korżel, Deric Crago, Cosmo Smith, Markus Kemmerling, Andrea Costantini, Daniel Patrick, Ryan Allen, Jason Selby, Greg Vaughan, Jonathan Sundqvist, Richard Bailey, Diane Soini, Dale Stewart, Mark Keaton, Johan Wärlander, Simon Scarfe, Eric Grannan, Marc-Anthony Taylor, Maria McKinley, John McKenna, Rafał Szymański, Roel van der Goot, Ignacio Reguero, TJ Tolton, Jonathan Means, Theodor Nolte, Jungsoo Moon, Craig Cook, Gabriel Ewilazarus, Vincenzo Pandolfo, David “farbish2”, Nico Coetzee, Daniel Gonzalez, Jared Contrascere, Zhao 赵亮, and many, many more. If I’ve missed your name, you have an absolute right to be aggrieved; I am incredibly grateful to you too, so write to me and I will try and make it up to you in any way I can.

And finally thanks to you, the latest reader, for deciding to check out the book! I hope you enjoy it.

Thanks to my wonderful editor for the second edition, Nan Barber, and to Susan Conant, Kristen Brown, and the whole team at O’Reilly. Thanks once again to Emily and Jonathan for tech reviewing, as well as to Edward Wong for his very thorough notes. Any remaining errors and inadequacies are all my own.

Thanks also to the readers of the free edition who contributed comments, suggestions, and even some pull requests. I have definitely missed some of you on this list, so apologies if your name isn’t here, but thanks to Emre Gonulates, Jésus Gómez, Jordon Birk, James Evans, Iain Houston, Jason DeWitt, Ronnie Raney, Spencer Ogden, Suresh Nimbalkar, Darius, Caco, LeBodro, Jeff, Duncan Betts, wasabigeek, joegnis, Lars, Mustafa, Jared, Craig, Sorcha, TJ, Ignacio, Roel, Justyna, Nathan, Andrea, Alexandr, bilyanhadzhi, mosegontar, sfarzy, henziger, hunterji, das-g, juanriaza, GeoWill, Windsooon, gonulate, Margie Roswell, Ben Elliott, Ramsay Mayka, peterj, 1hx, Wi, Duncan Betts, Matthew Senko, Neric “Kasu” Kaz, and many, many more.

In this first part, I’m going to introduce the basics of Test-Driven Development (TDD). We’ll build a real web application from scratch, writing tests first at every stage.

We’ll cover functional testing with Selenium, as well as unit testing, and see the difference between the two. I’ll introduce the TDD workflow, what I call the unit-test/code cycle. We’ll also do some refactoring, and see how that fits with TDD. Since it’s absolutely essential to serious software engineering, I’ll also be using a version control system (Git). We’ll discuss how and when to do commits and integrate them with the TDD and web development workflow.

We’ll be using Django, the Python world’s most popular web framework (probably). I’ve tried to introduce the Django concepts slowly and one at a time, and provide lots of links to further reading. If you’re a total beginner to Django, I thoroughly recommend taking the time to read them. If you find yourself feeling a bit lost, take a couple of hours to go through the official Django tutorial (make sure to use the 1.11 version), and then come back to the book.

You’ll also get to meet the Testing Goat…

If you’re working from a digital version of the book, it’s natural to want to copy and paste code listings from the book as you’re working through it. It’s much better if you don’t: typing things in by hand gets them into your muscle memory, and just feels much more real. You also inevitably make the occasional typo, and debugging them is an important thing to learn.

Quite apart from that, you’ll find that the quirks of the PDF format mean that weird stuff often happens when you try to copy/paste from it…

TDD isn’t something that comes naturally. It’s a discipline, like a martial art, and just like in a Kung Fu movie, you need a bad-tempered and unreasonable master to force you to learn the discipline. Ours is the Testing Goat.

The Testing Goat is the unofficial mascot of TDD in the Python testing community. It probably means different things to different people, but, to me, the Testing Goat is a voice inside my head that keeps me on the True Path of Testing—like one of those little angels or demons that pop up above your shoulder in the cartoons, but with a very niche set of concerns. I hope, with this book, to install the Testing Goat inside your head too.

We’ve decided to build a website, even if we’re not quite sure what it’s going to do yet. Normally the first step in web development is getting your web framework installed and configured. Download this, install that, configure the other, run the script…but TDD requires a different mindset. When you’re doing TDD, you always have the Testing Goat inside you—single-minded as goats are—bleating “Test first, test first!”

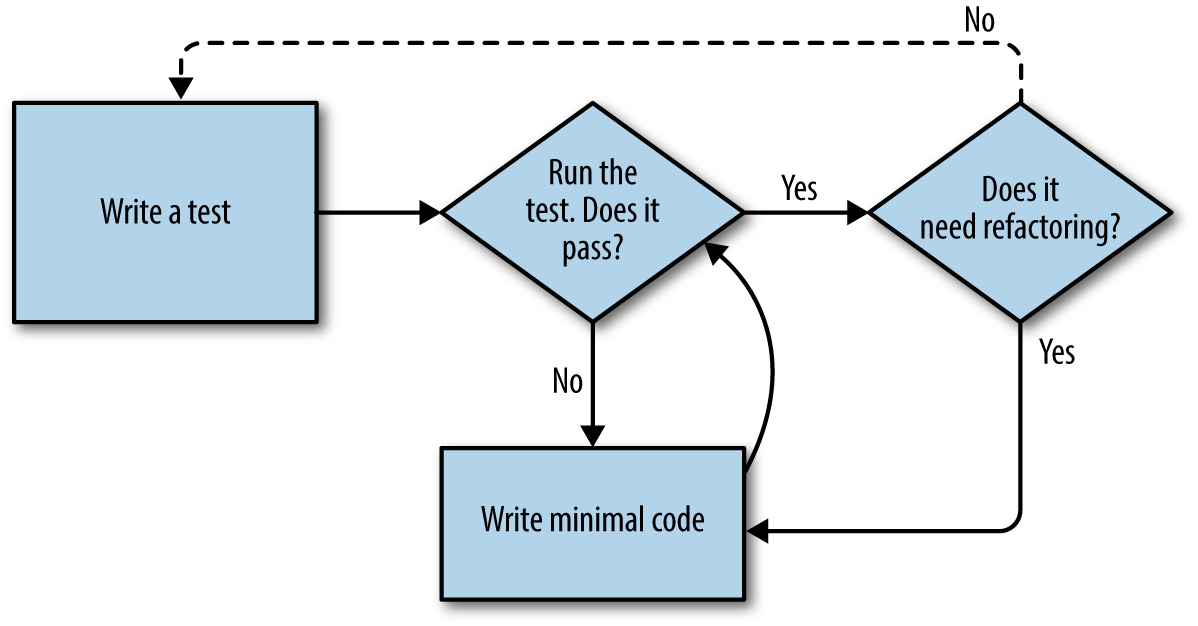

In TDD the first step is always the same: write a test.

First we write the test; then we run it and check that it fails as expected. Only then do we go ahead and build some of our app. Repeat that to yourself in a goat-like voice. I know I do.

Another thing about goats is that they take one step at a time. That’s why they seldom fall off mountains, see, no matter how steep they are. As you can see in Figure 1-1.

We’ll proceed with nice small steps; we’re going to use Django, which is a popular Python web framework, to build our app.

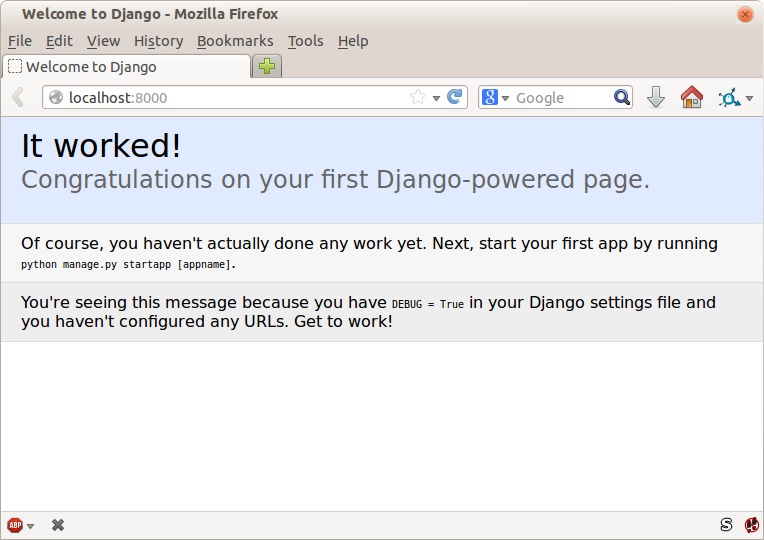

The first thing we want to do is check that we’ve got Django installed, and that it’s ready for us to work with. The way we’ll check is by confirming that we can spin up Django’s development server and actually see it serving up a web page, in our web browser, on our local PC. We’ll use the Selenium browser automation tool for this.

Create a new Python file called functional_tests.py, wherever you want to keep the code for your project, and enter the following code. If you feel like making a few little goat noises as you do it, it may help:

functional_tests.py

fromseleniumimportwebdriverbrowser=webdriver.Firefox()browser.get('http://localhost:8000')assert'Django'inbrowser.title

That’s our first functional test (FT); I’ll talk more about what I mean by functional tests, and how they contrast with unit tests, in a bit. For now, it’s enough to assure ourselves that we understand what it’s doing:

Starting a Selenium “webdriver” to pop up a real Firefox browser window

Using it to open up a web page which we’re expecting to be served from the local PC

Checking (making a test assertion) that the page has the word “Django” in its title

Let’s try running it:

$ python functional_tests.py

File ".../selenium/webdriver/remote/webdriver.py", line 324, in get

self.execute(Command.GET, {'url': url})

File ".../selenium/webdriver/remote/webdriver.py", line 312, in execute

self.error_handler.check_response(response)

File ".../selenium/webdriver/remote/errorhandler.py", line 242, in

check_response

raise exception_class(message, screen, stacktrace)

selenium.common.exceptions.WebDriverException: Message: Reached error page: abo

ut:neterror?e=connectionFailure&u=http%3A//localhost%3A8000/[...]

You should see a browser window pop up and try to open localhost:8000, and show the “Unable to connect” error page. If you switch back to your console, you’ll see the big ugly error message, telling us that Selenium hit an error page. And then, you will probably be irritated at the fact that it left the Firefox window lying around your desktop for you to tidy up. We’ll fix that later!

If, instead, you see an error trying to import Selenium, or an error trying to find “geckodriver”, you might need to go back and have another look at the "Prerequisites and Assumptions" section.

For now though, we have a failing test, so that means we’re allowed to start building our app.

Since you’ve definitely read “Prerequisites and Assumptions” by now, you’ve already got Django installed. The first step in getting Django up and running is to create a project, which will be the main container for our site. Django provides a little command-line tool for this:

$ django-admin.py startproject superlists .

Don’t forget that “.” at the end; it’s important!

That will create a file called manage.py in your current folder, and a subfolder called superlists, with more stuff inside it:

├── functional_tests.py

├── geckodriver.log

├── manage.py

├── superlists

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

└── virtualenv

├── [...]

Make sure your project folder looks exactly like this! If you see two nested folders called superlists, it’s because you forgot the “.” above. Delete them and try again.

The superlists folder is intended for stuff that applies to the whole project—like settings.py, for example, which is used to store global configuration information for the site.

But the main thing to notice is manage.py. That’s Django’s Swiss Army knife, and one of the things it can do is run a development server. Let’s try that now:

$ python manage.py runserver Performing system checks... System check identified no issues (0 silenced). You have 13 unapplied migration(s). Your project may not work properly until you apply the migrations for app(s): admin, auth, contenttypes, sessions. Run 'python manage.py migrate' to apply them. Django version 1.11.3, using settings 'superlists.settings' Starting development server at http://127.0.0.1:8000/ Quit the server with CONTROL-C.

It’s safe to ignore that message about “unapplied migrations” for now. We’ll look at migrations in Chapter 5.

That’s Django’s development server now up and running on our machine.

Leave it there and open another command shell. Navigate to your project folder, activate your virtualenv, and then try running our test again:

$ python functional_tests.py $

If you see an error saying “no module named selenium”, you’ve forgotten to activate your virtualenv. Check the Prerequisites and Assumptions section again if you need to.

Not much action on the command line, but you should notice two things: firstly,

there was no ugly AssertionError and secondly, the Firefox window that

Selenium popped up had a different-looking page on it.

Well, it may not look like much, but that was our first ever passing test! Hooray!

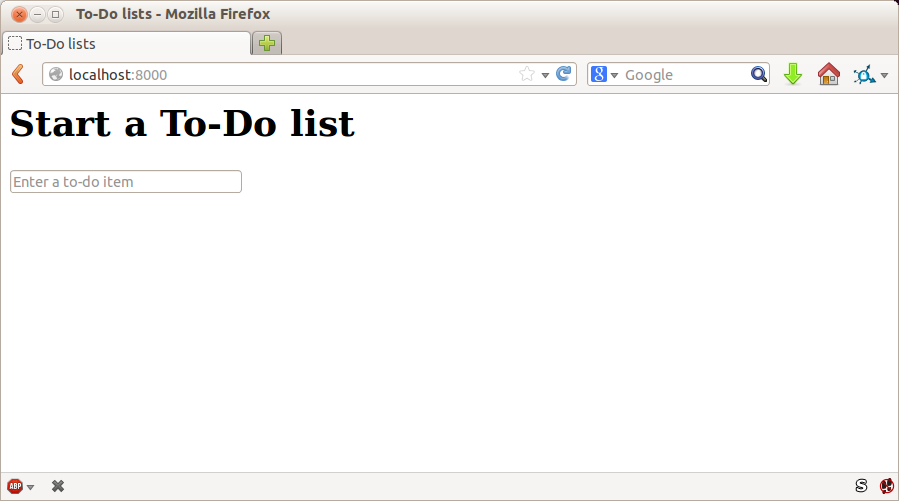

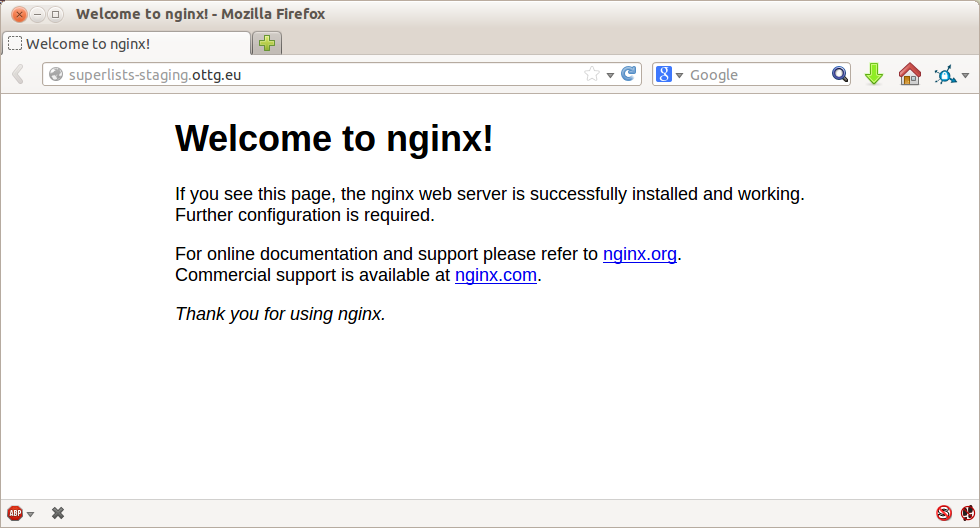

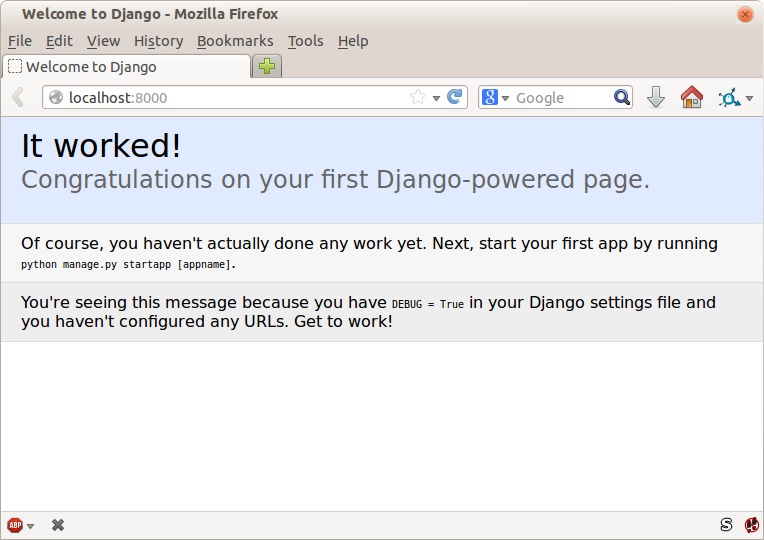

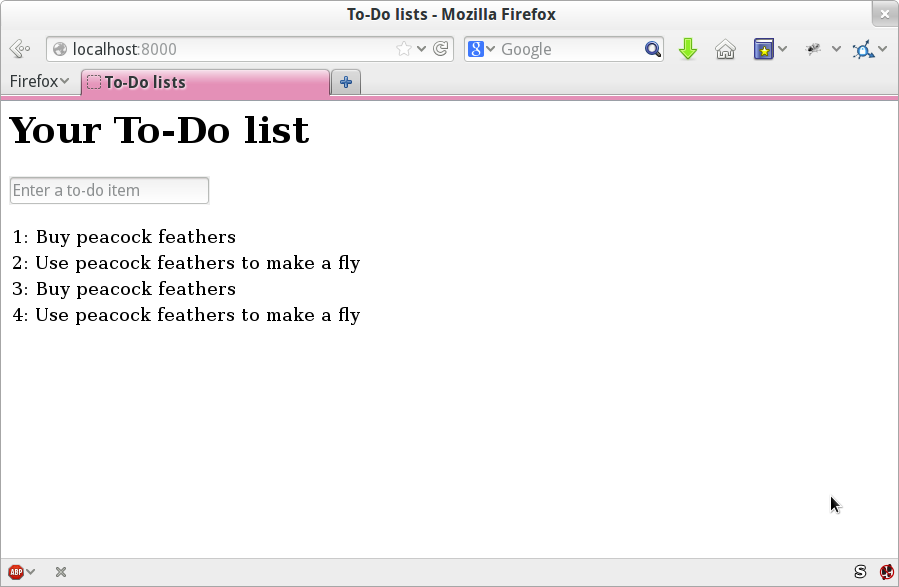

If it all feels a bit too much like magic, like it wasn’t quite real, why not go and take a look at the dev server manually, by opening a web browser yourself and visiting http://localhost:8000? You should see something like Figure 1-2.

You can quit the development server now if you like, back in the original shell, using Ctrl-C.

There’s one last thing to do before we finish the chapter: start to commit our work to a version control system (VCS). If you’re an experienced programmer you don’t need to hear me preaching about version control, but if you’re new to it please believe me when I say that VCS is a must-have. As soon as your project gets to be more than a few weeks old and a few lines of code, having a tool available to look back over old versions of code, revert changes, explore new ideas safely, even just as a backup…boy. TDD goes hand in hand with version control, so I want to make sure I impart how it fits into the workflow.

So, our first commit! If anything it’s a bit late; shame on us. We’re using Git as our VCS, ’cos it’s the best.

Let’s start by doing the git init to start the repository:

$ ls db.sqlite3 functional_tests.py geckodriver.log manage.py superlists virtualenv $ git init . Initialised empty Git repository in ...python-tdd-book/.git/

Now let’s take a look and see what files we want to commit:

$ ls db.sqlite3 functional_tests.py geckodriver.log manage.py superlists virtualenv

There are a few things in here that we don’t want under version control: db.sqlite3 is the database file, geckodriver.log contains Selenium debug output, and finally our virtualenv shouldn’t be in git either. We’ll add all of them to a special file called .gitignore which, um, tells Git what to ignore:

$ echo "db.sqlite3" >> .gitignore $ echo "geckodriver.log" >> .gitignore $ echo "virtualenv" >> .gitignore

Next we can add the rest of the contents of the current folder, “.”:

$ git add .

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitignore

new file: functional_tests.py

new file: manage.py

new file: superlists/__init__.py

new file: superlists/__pycache__/__init__.cpython-36.pyc

new file: superlists/__pycache__/settings.cpython-36.pyc

new file: superlists/__pycache__/urls.cpython-36.pyc

new file: superlists/__pycache__/wsgi.cpython-36.pyc

new file: superlists/settings.py

new file: superlists/urls.py

new file: superlists/wsgi.py

Oops! We’ve got a bunch of .pyc files in there; it’s pointless to commit those. Let’s remove them from Git and add them to .gitignore too:

$ git rm -r --cached superlists/__pycache__ rm 'superlists/__pycache__/__init__.cpython-36.pyc' rm 'superlists/__pycache__/settings.cpython-36.pyc' rm 'superlists/__pycache__/urls.cpython-36.pyc' rm 'superlists/__pycache__/wsgi.cpython-36.pyc' $ echo "__pycache__" >> .gitignore $ echo "*.pyc" >> .gitignore

Now let’s see where we are… (You’ll see I’m using git status a lot—so

much so that I often alias it to git st…I’m not telling you how to do

that though; I leave you to discover the secrets of Git aliases on your own!):

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitignore

new file: functional_tests.py

new file: manage.py

new file: superlists/__init__.py

new file: superlists/settings.py

new file: superlists/urls.py

new file: superlists/wsgi.py

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: .gitignore

Looking good—we’re ready to do our first commit!

$ git add .gitignore $ git commit

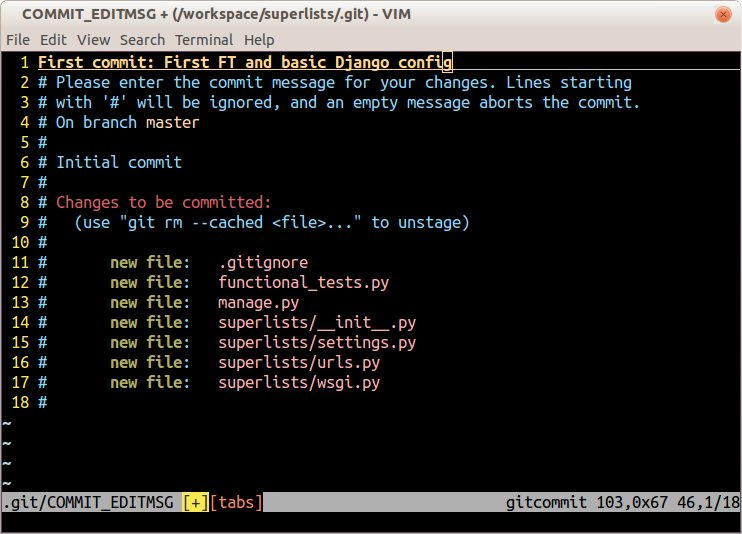

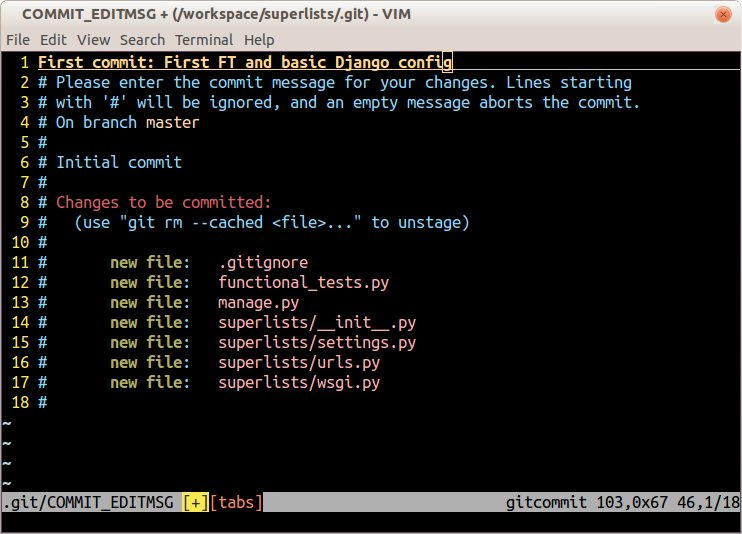

When you type git commit, it will pop up an editor window for you to write

your commit message in. Mine looked like

Figure 1-3.1

If you want to really go to town on Git, this is the time to also learn about how to push your work to a cloud-based VCS hosting service, like GitHub or Bitbucket. They’ll be useful if you think you want to follow along with this book on different PCs. I leave it to you to find out how they work; they have excellent documentation. Alternatively, you can wait until Chapter 9 when we’ll be using one for deployment.

That’s it for the VCS lecture. Congratulations! You’ve written a functional test using Selenium, and you’ve gotten Django installed and running, in a certifiable, test-first, goat-approved TDD way. Give yourself a well-deserved pat on the back before moving on to Chapter 2.

1 Did vi pop up and you had no idea what to do? Or did you see a message about account identity and git config --global

user.username? Go and take another look at “Prerequisites and Assumptions”; there are some brief instructions.

Let’s adapt our test, which currently checks for the default Django “it worked” page, and check instead for some of the things we want to see on the real front page of our site.

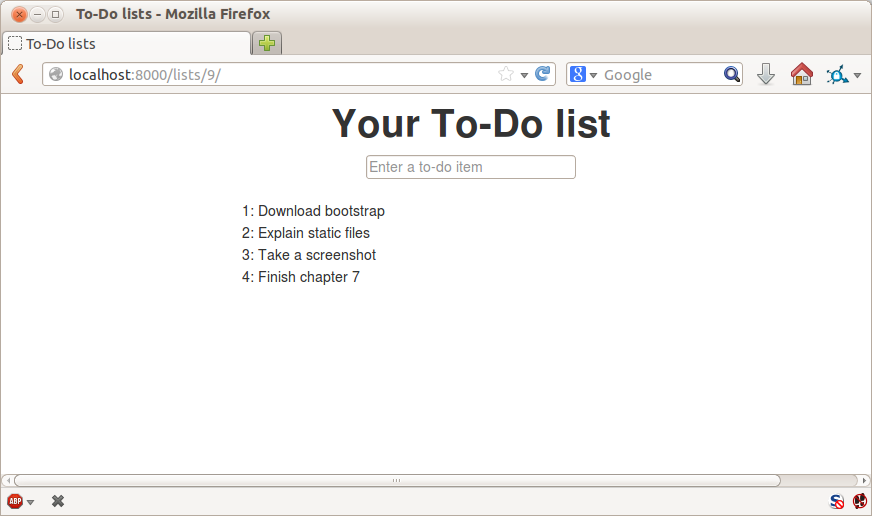

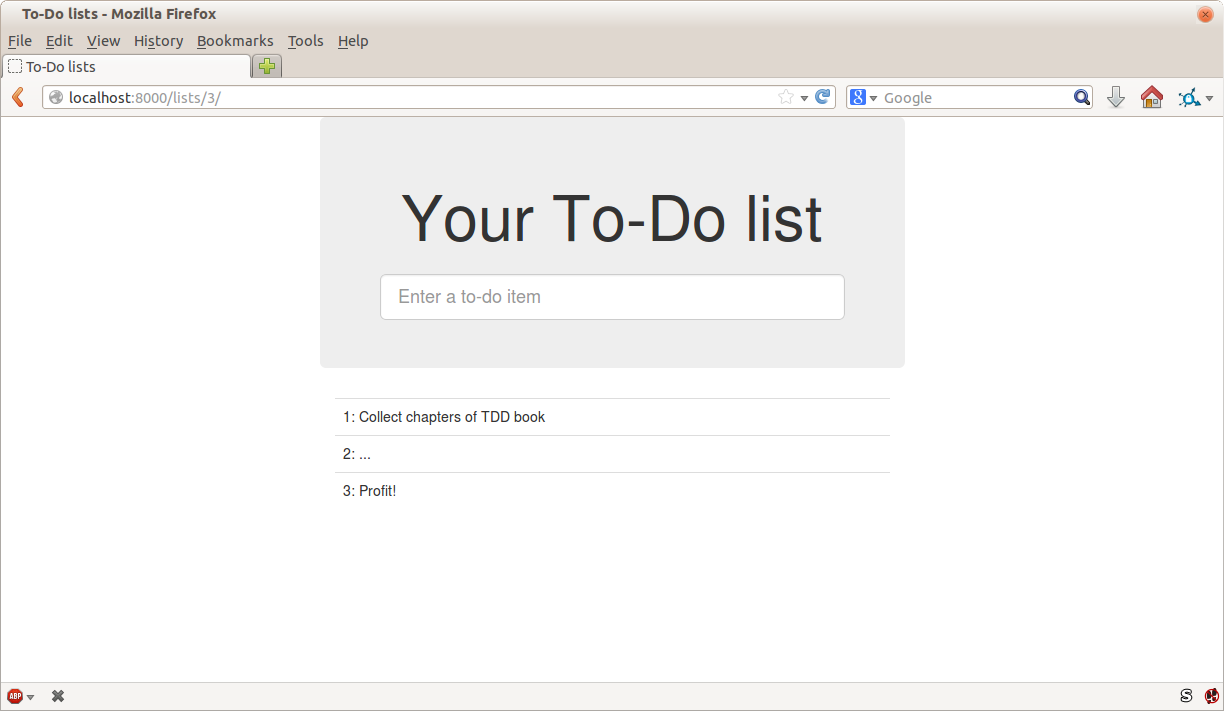

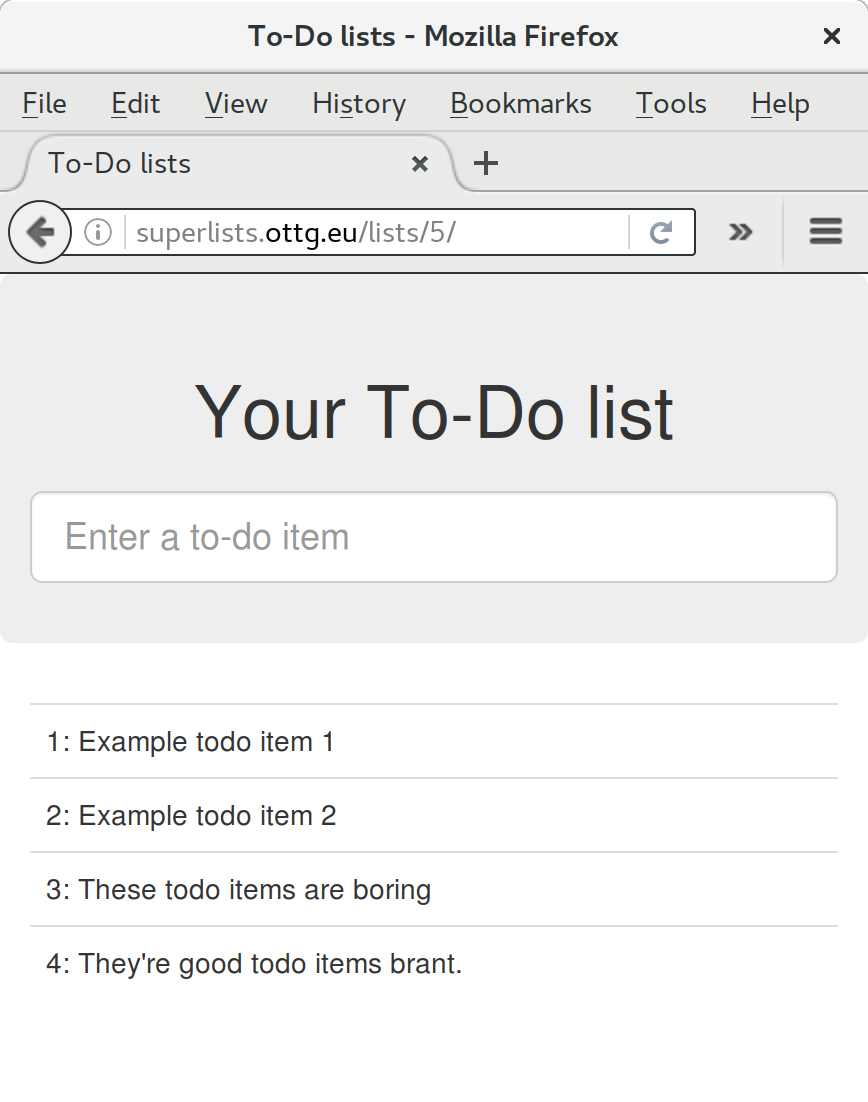

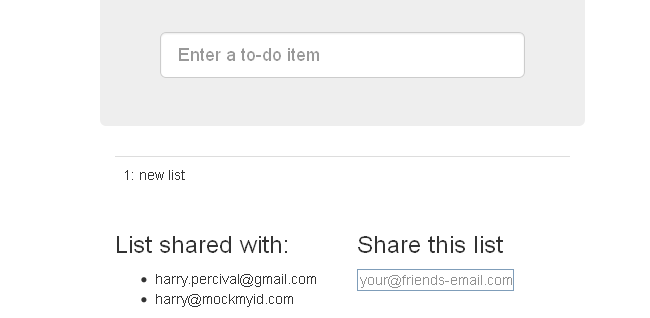

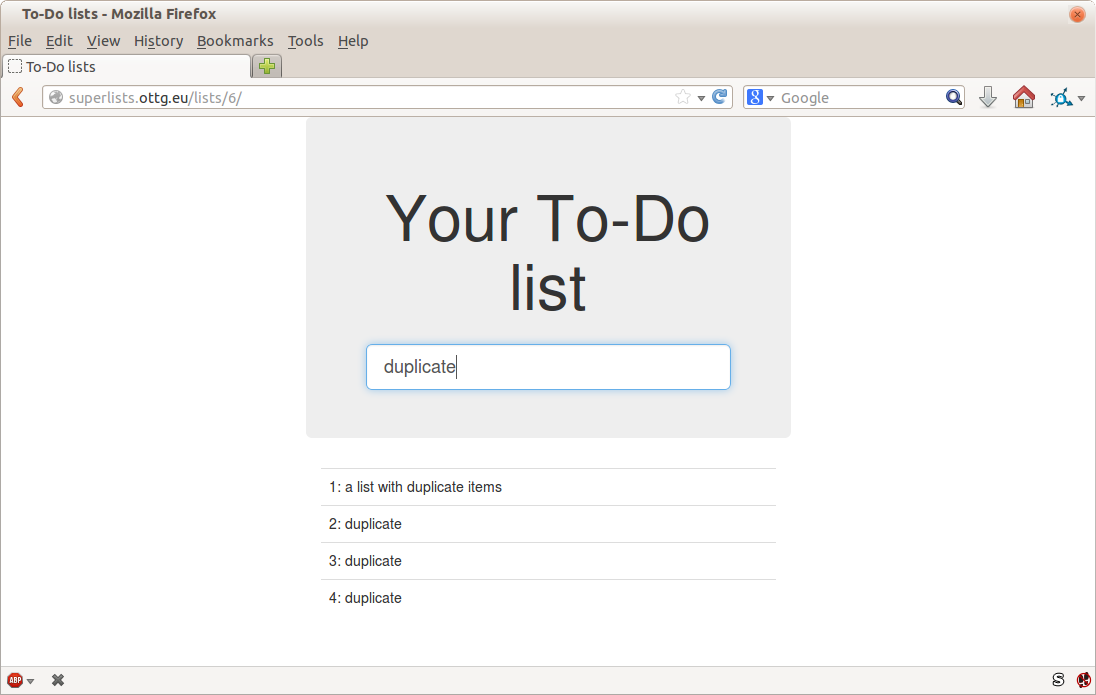

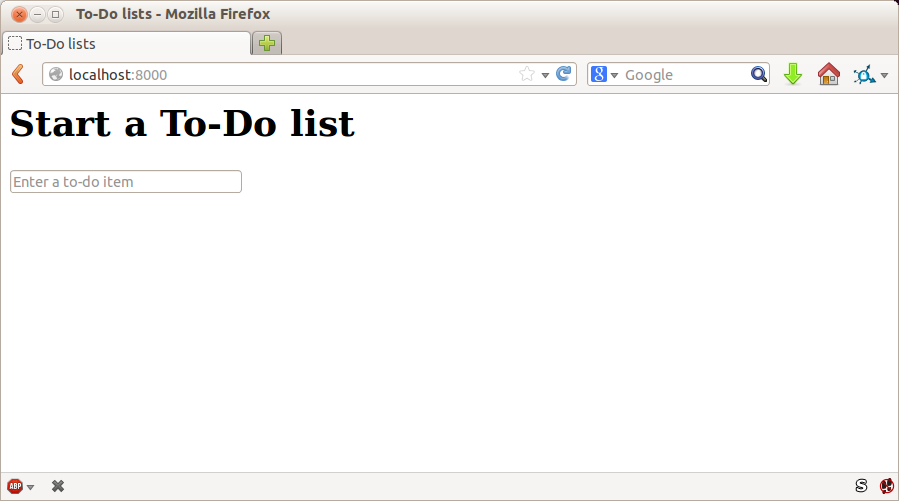

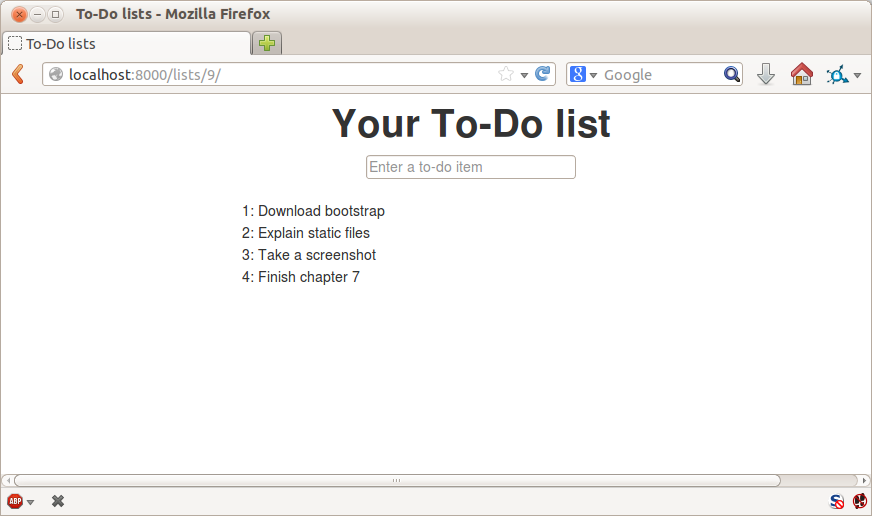

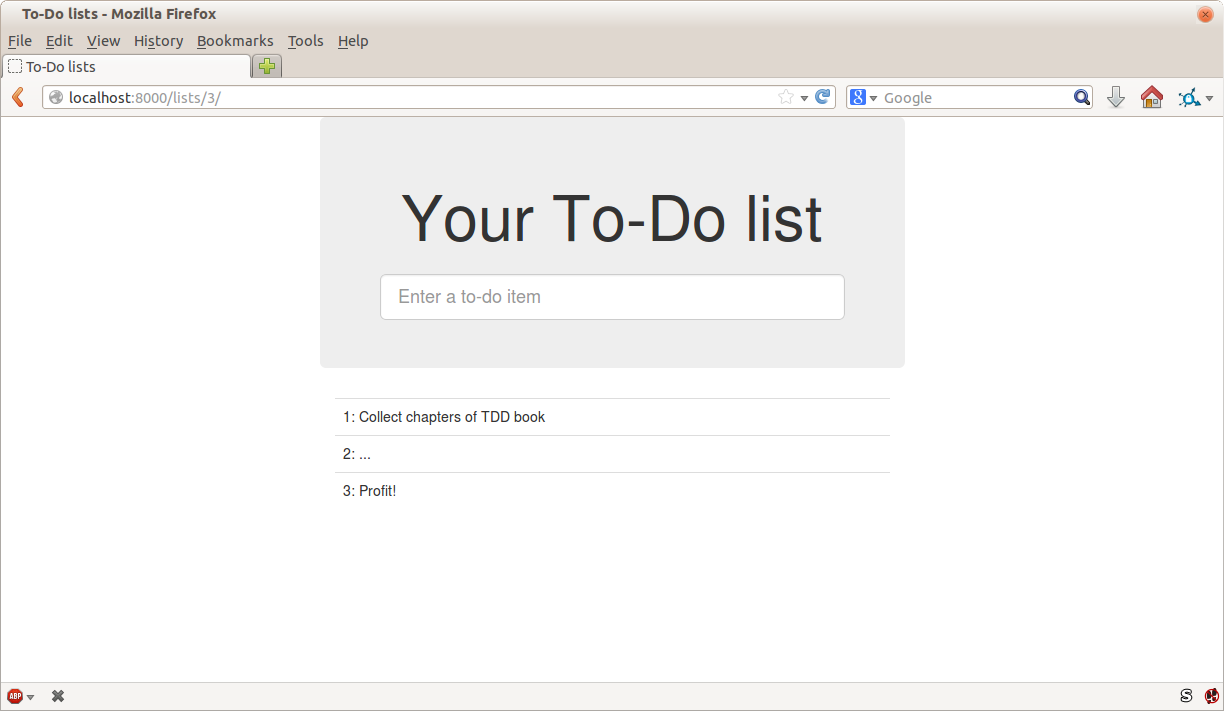

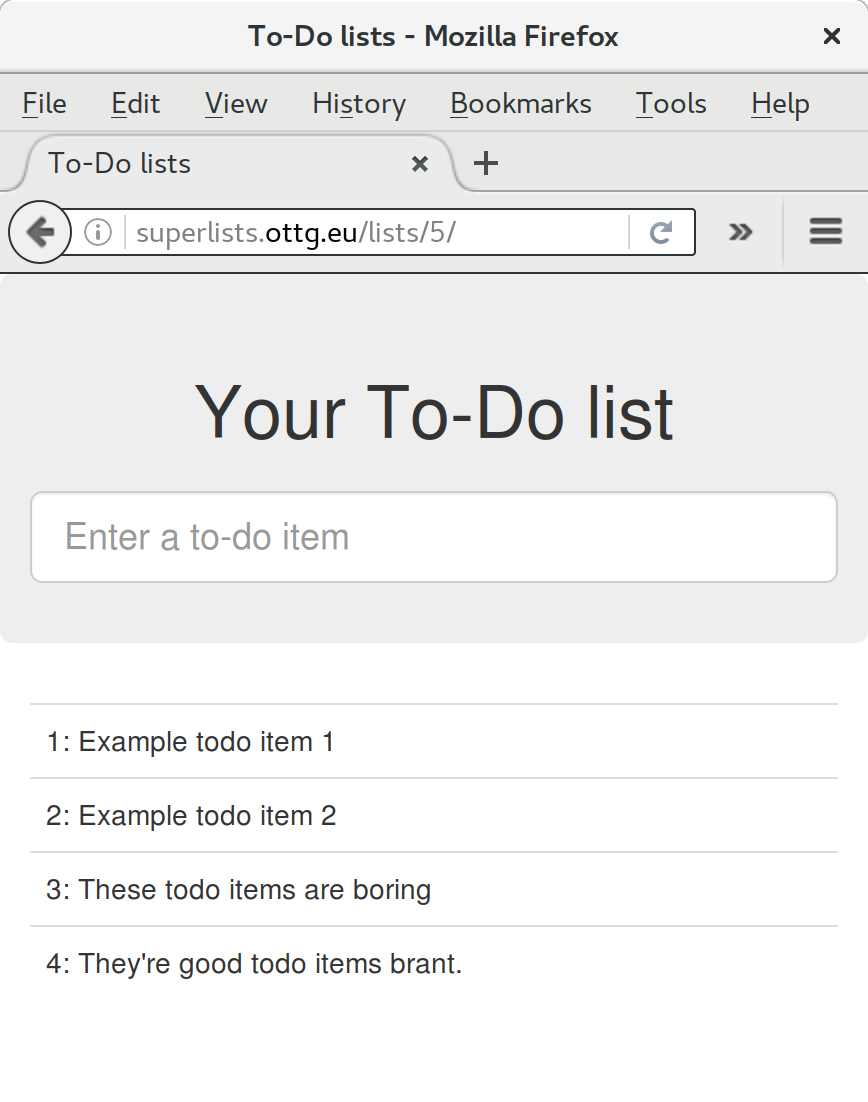

Time to reveal what kind of web app we’re building: a to-do lists site! In doing so we’re very much following fashion: a few years ago all web tutorials were about building a blog. Then it was forums and polls; nowadays it’s all to-do lists.

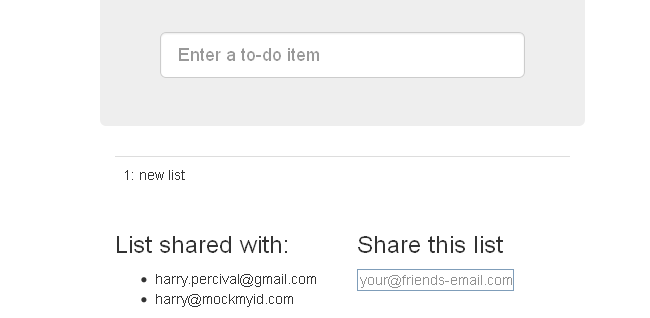

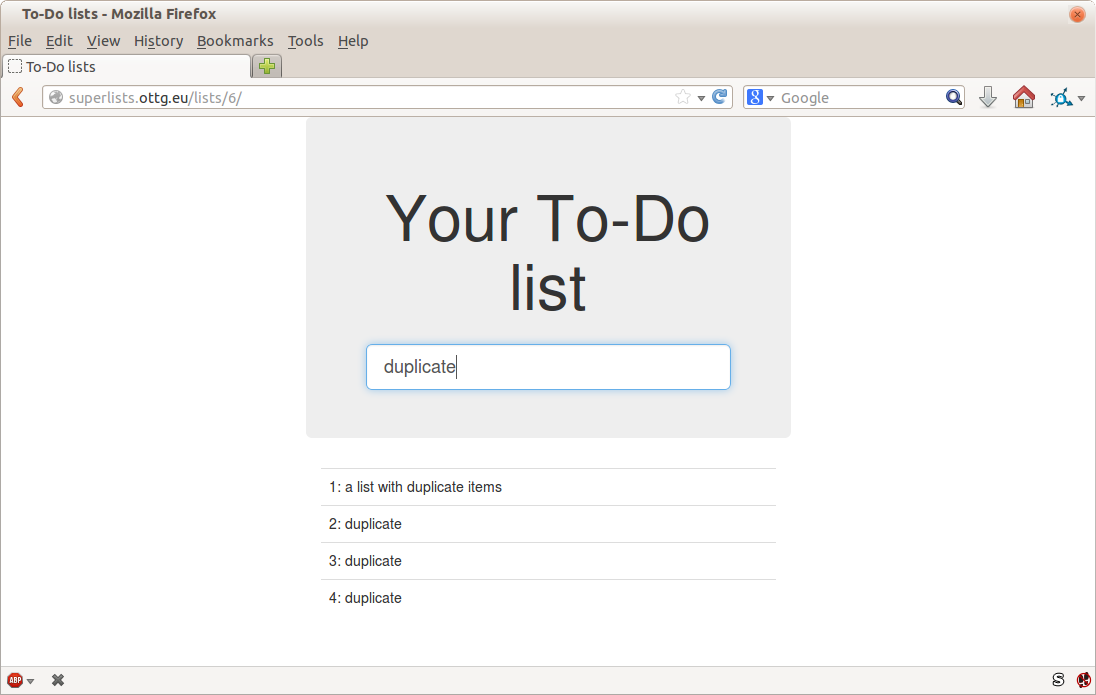

The reason is that a to-do list is a really nice example. At its most basic it is very simple indeed—just a list of text strings—so it’s easy to get a “minimum viable” list app up and running. But it can be extended in all sorts of ways—different persistence models, adding deadlines, reminders, sharing with other users, and improving the client-side UI. There’s no reason to be limited to just “to-do” lists either; they could be any kind of lists. But the point is that it should allow me to demonstrate all of the main aspects of web programming, and how you apply TDD to them.

Tests that use Selenium let us drive a real web browser, so they really let us see how the application functions from the user’s point of view. That’s why they’re called functional tests.

This means that an FT can be a sort of specification for your application. It tends to track what you might call a User Story, and follows how the user might work with a particular feature and how the app should respond to them.

FTs should have a human-readable story that we can follow. We make it explicit using comments that accompany the test code. When creating a new FT, we can write the comments first, to capture the key points of the User Story. Being human-readable, you could even share them with nonprogrammers, as a way of discussing the requirements and features of your app.

TDD and agile software development methodologies often go together, and one of the things we often talk about is the minimum viable app; what is the simplest thing we can build that is still useful? Let’s start by building that, so that we can test the water as quickly as possible.

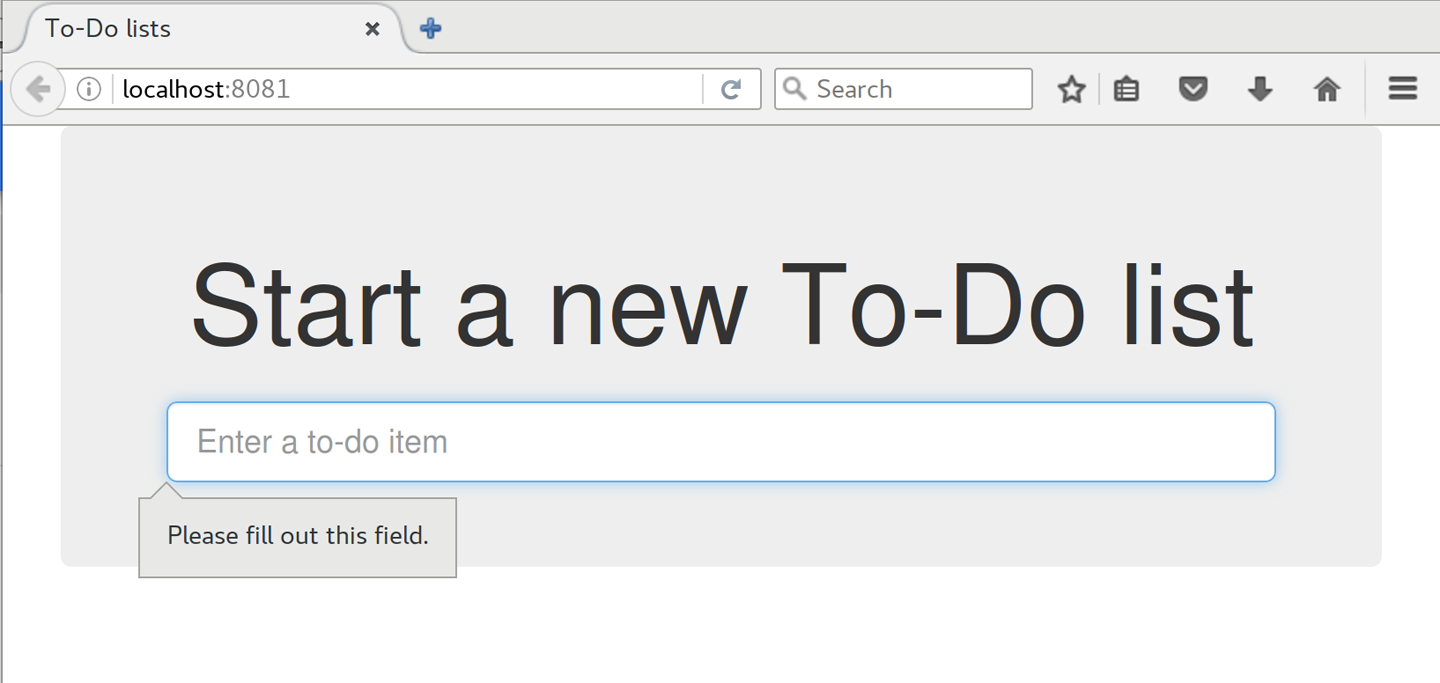

A minimum viable to-do list really only needs to let the user enter some to-do items, and remember them for their next visit.

Open up functional_tests.py and write a story a bit like this one:

functional_tests.py

fromseleniumimportwebdriverbrowser=webdriver.Firefox()# Edith has heard about a cool new online to-do app. She goes# to check out its homepagebrowser.get('http://localhost:8000')# She notices the page title and header mention to-do listsassert'To-Do'inbrowser.title# She is invited to enter a to-do item straight away# She types "Buy peacock feathers" into a text box (Edith's hobby# is tying fly-fishing lures)# When she hits enter, the page updates, and now the page lists# "1: Buy peacock feathers" as an item in a to-do list# There is still a text box inviting her to add another item. She# enters "Use peacock feathers to make a fly" (Edith is very methodical)# The page updates again, and now shows both items on her list# Edith wonders whether the site will remember her list. Then she sees# that the site has generated a unique URL for her -- there is some# explanatory text to that effect.# She visits that URL - her to-do list is still there.# Satisfied, she goes back to sleepbrowser.quit()

You’ll notice that, apart from writing the test out as comments, I’ve

updated the assert to look for the word “To-Do” instead of “Django”.

That means we expect the test to fail now. Let’s try running it.

First, start up the server:

$ python manage.py runserver

And then, in another shell, run the tests:

$ python functional_tests.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "functional_tests.py", line 10, in <module>

assert 'To-Do' in browser.title

AssertionError

That’s what we call an expected fail, which is actually good news—not quite as good as a test that passes, but at least it’s failing for the right reason; we can have some confidence we’ve written the test correctly.

There are a couple of little annoyances we should probably deal with. Firstly, the message “AssertionError” isn’t very helpful—it would be nice if the test told us what it actually found as the browser title. Also, it’s left a Firefox window hanging around the desktop, so it would be nice if that got cleared up for us automatically.

One option would be to use the second parameter to the assert keyword,

something like:

assert'To-Do'inbrowser.title,"Browser title was "+browser.title

And we could also use a try/finally to clean up the old Firefox window. But

these sorts of problems are quite common in testing, and there are some

ready-made

solutions for us in the standard library’s unittest module. Let’s

use that! In

functional_tests.py:

functional_tests.py

fromseleniumimportwebdriverimportunittestclassNewVisitorTest(unittest.TestCase):defsetUp(self):self.browser=webdriver.Firefox()deftearDown(self):self.browser.quit()deftest_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later(self):# Edith has heard about a cool new online to-do app. She goes# to check out its homepageself.browser.get('http://localhost:8000')# She notices the page title and header mention to-do listsself.assertIn('To-Do',self.browser.title)self.fail('Finish the test!')# She is invited to enter a to-do item straight away[...restofcommentsasbefore]if__name__=='__main__':unittest.main(warnings='ignore')

You’ll probably notice a few things here:

Tests are organised into classes, which inherit from unittest.TestCase.

The main body of the test is in a method called

test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later. Any method

whose name starts with test is a test method, and will be run by the

test runner. You can have more than one test_ method per class. Nice

descriptive names for our test methods are a good idea too.

setUp and tearDown are special methods which get

run before and after each test. I’m using them to start and stop our

browser—note that they’re a bit like a try/except, in that tearDown will

run even if there’s an error during the test

itself.1

No more Firefox windows left lying around!

We use self.assertIn instead of just assert to make our test

assertions. unittest provides lots of helper functions like this to make

test assertions, like assertEqual, assertTrue, assertFalse, and so

on. You can find more in the

unittest documentation.

self.fail just fails no matter what, producing the error message given.

I’m using it as a reminder to finish the test.

Finally, we have the if __name__ == '__main__' clause (if you’ve not seen it

before, that’s how a Python script checks if it’s been executed from the

command line, rather than just imported by another script). We call

unittest.main(), which launches the unittest test runner, which will

automatically find test classes and methods in the file and run them.

warnings='ignore' suppresses a superfluous ResourceWarning which

was being emitted at the time of writing. It may have disappeared by the

time you read this; feel free to try removing it!

If you’ve read the Django testing documentation, you might have seen

something called LiveServerTestCase, and are wondering whether we should

use it now. Full points to you for reading the friendly manual!

LiveServerTestCase is a bit too complicated for now, but I promise I’ll

use it in a later chapter…

Let’s try it!

$ python functional_tests.py

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later (__main__.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "functional_tests.py", line 18, in

test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later

self.assertIn('To-Do', self.browser.title)

AssertionError: 'To-Do' not found in 'Welcome to Django'

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 1.747s

FAILED (failures=1)

That’s a bit nicer, isn’t it? It tidied up our Firefox window, it gives us a

nicely formatted report of how many tests were run and how many failed, and

the assertIn has given us a helpful error message with useful debugging info.

Bonzer!

This

is a good point to do a commit; it’s a nicely self-contained change. We’ve

expanded our functional test to include comments that describe the task we’re

setting ourselves, our minimum viable to-do list. We’ve also rewritten it to

use the Python unittest module and its various testing helper functions.

Do a git status—that should assure you that the only file that has

changed is functional_tests.py. Then do a git diff, which shows you the

difference between the last commit and what’s currently on disk. That should

tell you that functional_tests.py has changed quite substantially:

$ git diff

diff --git a/functional_tests.py b/functional_tests.py

index d333591..b0f22dc 100644

--- a/functional_tests.py

+++ b/functional_tests.py

@@ -1,6 +1,45 @@

from selenium import webdriver

+import unittest

-browser = webdriver.Firefox()

-browser.get('http://localhost:8000')

+class NewVisitorTest(unittest.TestCase):

-assert 'Django' in browser.title

+ def setUp(self):

+ self.browser = webdriver.Firefox()

+

+ def tearDown(self):

+ self.browser.quit()

[...]

Now let’s do a:

$ git commit -a

The -a means “automatically add any changes to tracked files” (i.e., any

files that we’ve committed before). It won’t add any brand new files (you have

to explicitly git add them yourself), but often, as in this case, there aren’t

any new files, so it’s a useful shortcut.

When the editor pops up, add a descriptive commit message, like “First FT specced out in comments, and now uses unittest.”

Now we’re in an excellent position to start writing some real code for our lists app. Read on!

1 The only exception is if you have an exception inside setUp, then tearDown doesn’t run.

We finished the last chapter with a functional test failing, telling us that it wanted the home page for our site to have “To-Do” in its title. It’s time to start working on our application.

Django encourages you to structure your code into apps: the theory is that one project can have many apps, you can use third-party apps developed by other people, and you might even reuse one of your own apps in a different project…although I admit I’ve never actually managed it myself! Still, apps are a good way to keep your code organised.

Let’s start an app for our to-do lists:

$ python manage.py startapp lists

That will create a folder called lists, next to manage.py and the existing superlists folder , and within it a number of placeholder files for things like models, views, and, of immediate interest to us, tests:

.

├── db.sqlite3

├── functional_tests.py

├── lists

│ ├── admin.py

│ ├── apps.py

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── migrations

│ │ └── __init__.py

│ ├── models.py

│ ├── tests.py

│ └── views.py

├── manage.py

├── superlists

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── __pycache__

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

└── virtualenv

├── [...]

As with so many of the labels we put on things, the line between unit tests and functional tests can become a little blurry at times. The basic distinction, though, is that functional tests test the application from the outside, from the point of view of the user. Unit tests test the application from the inside, from the point of view of the programmer.

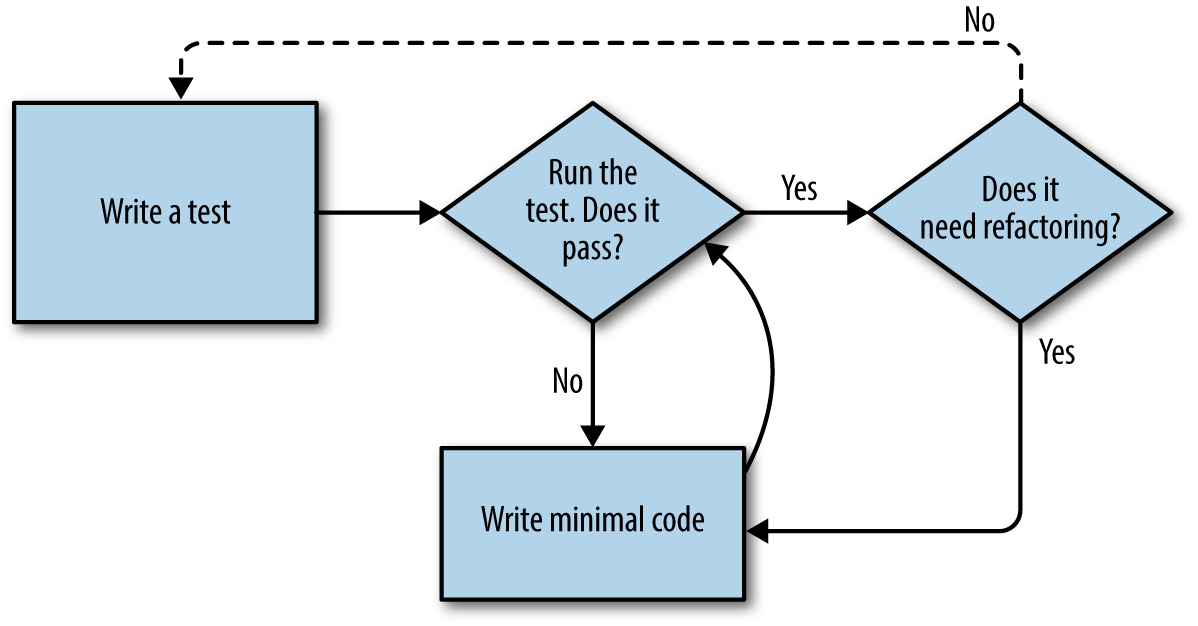

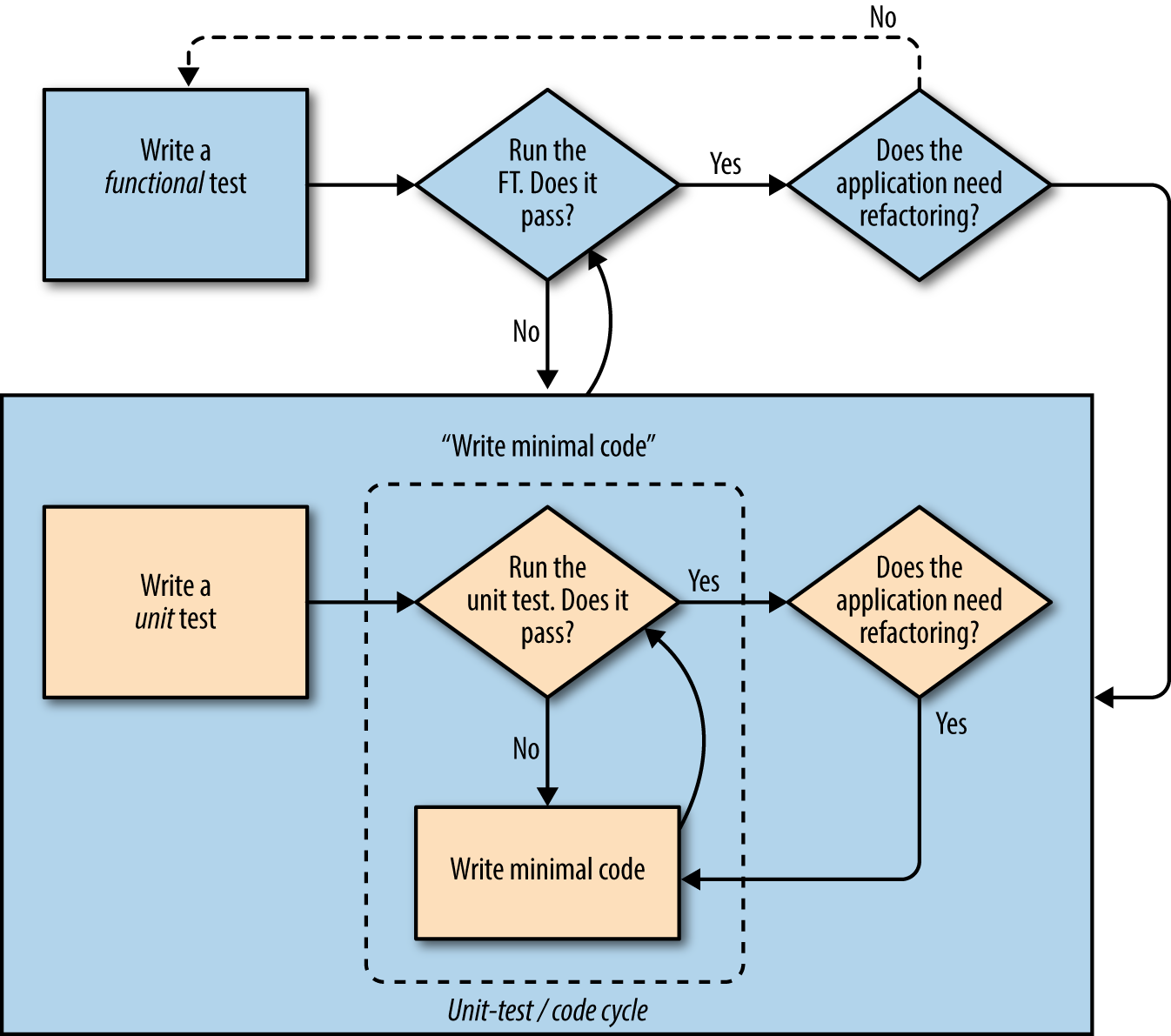

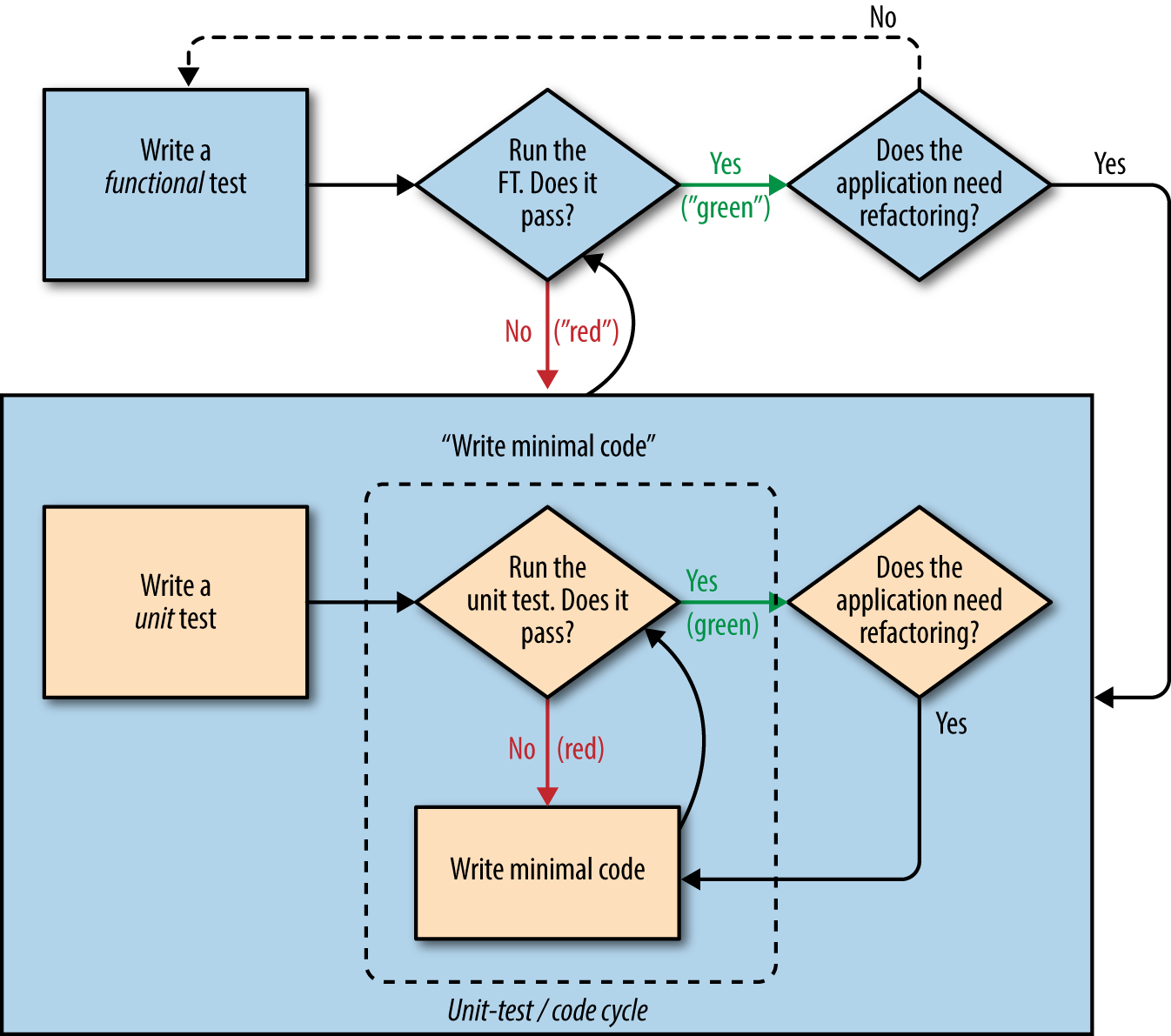

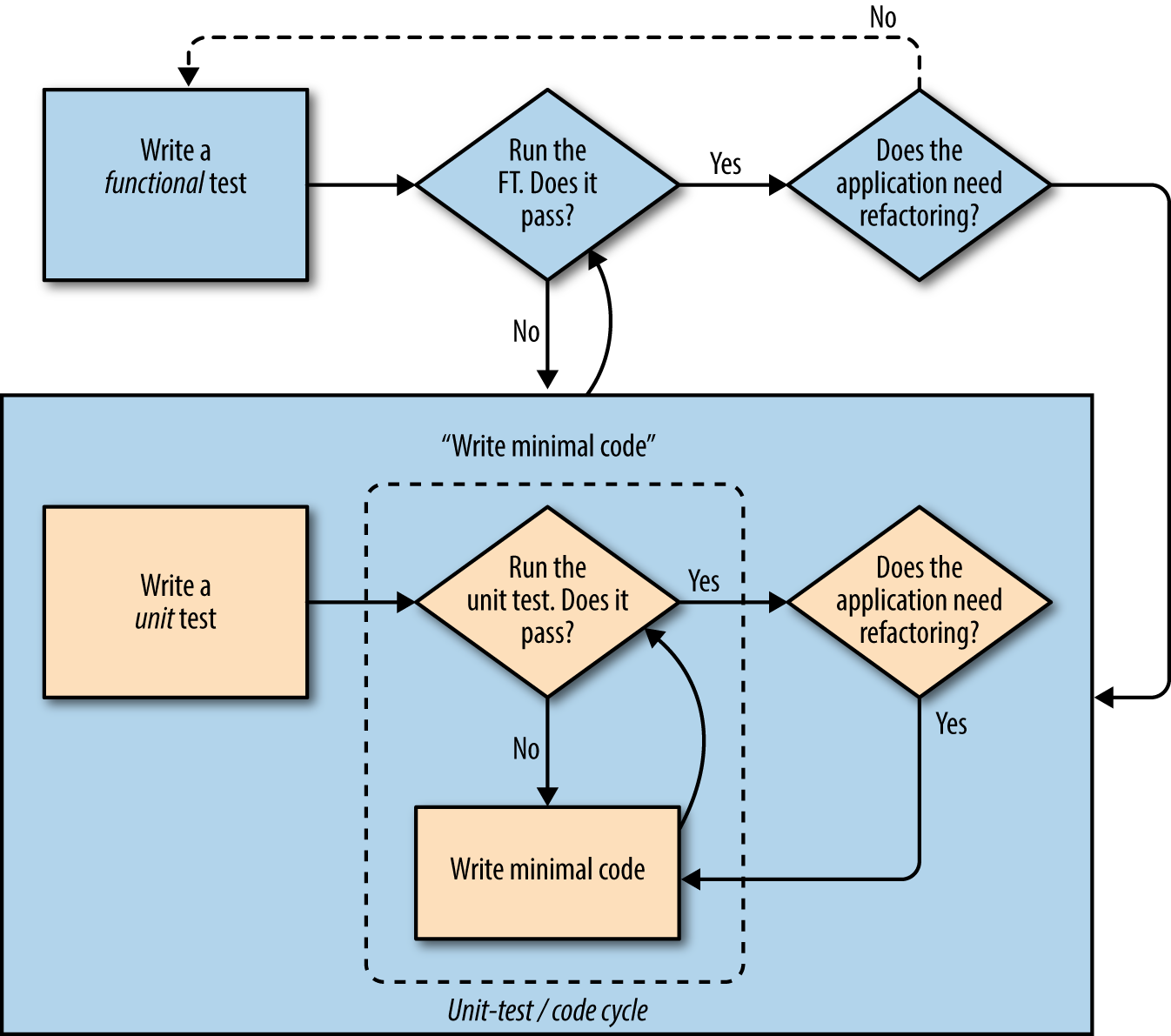

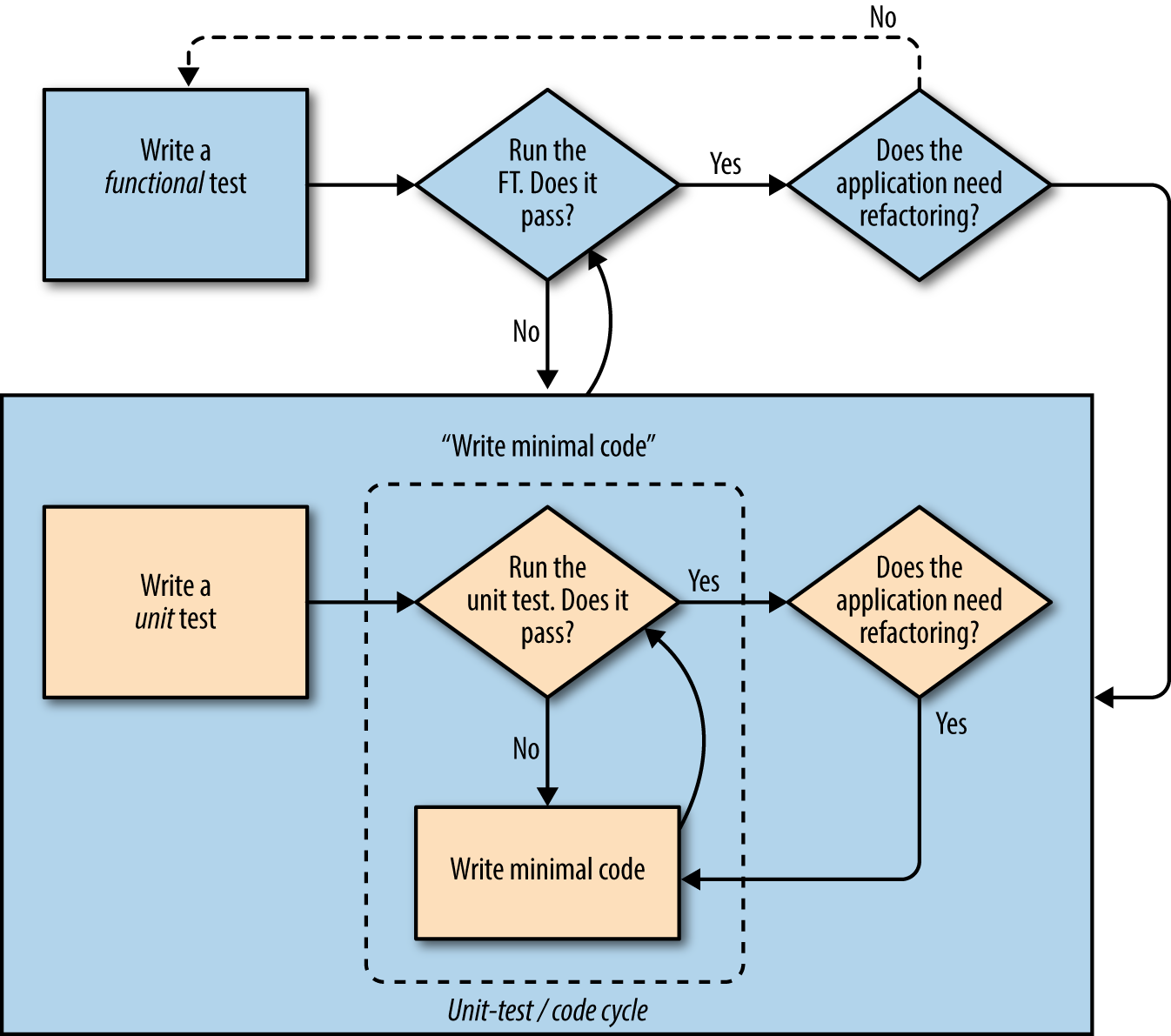

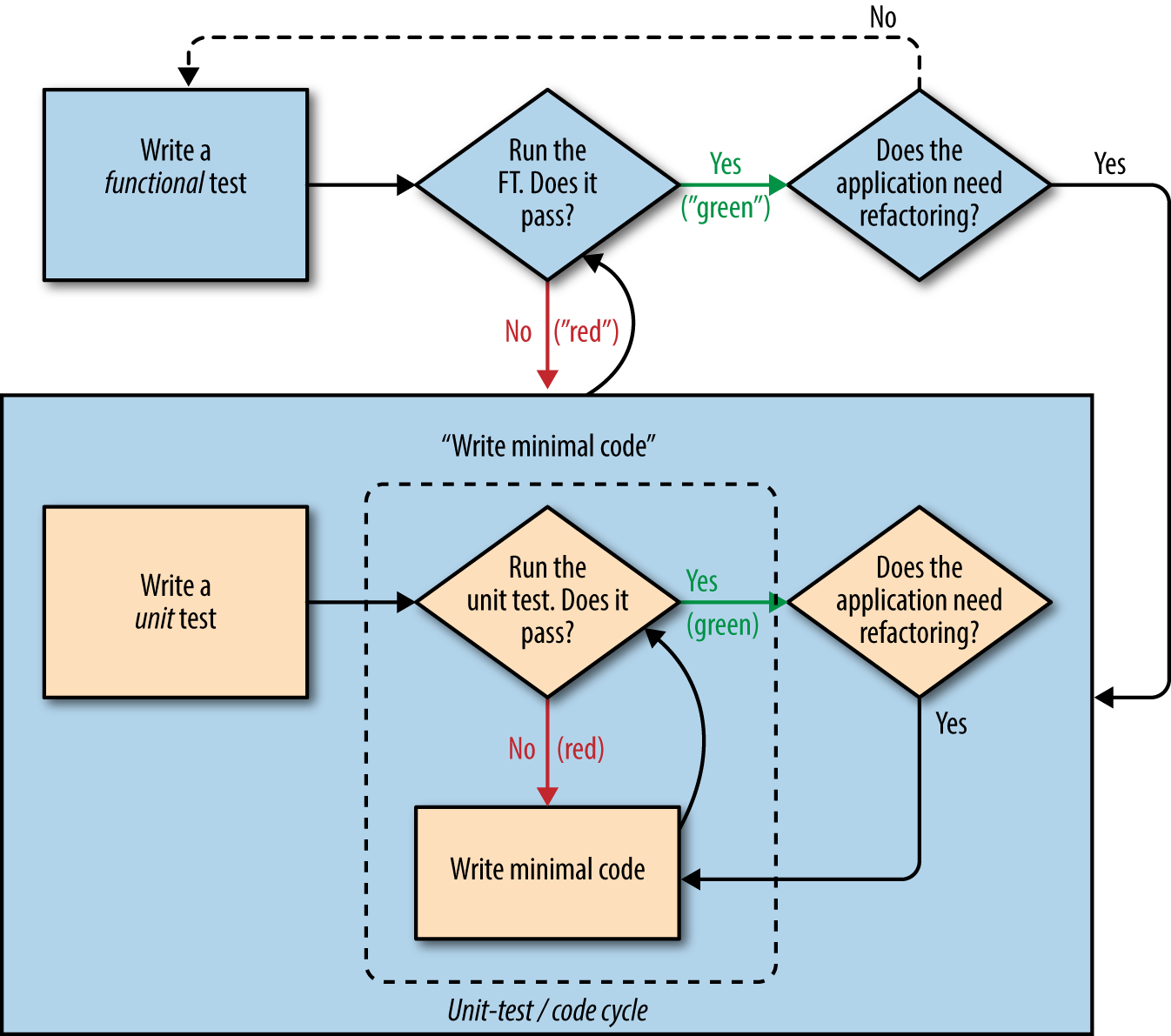

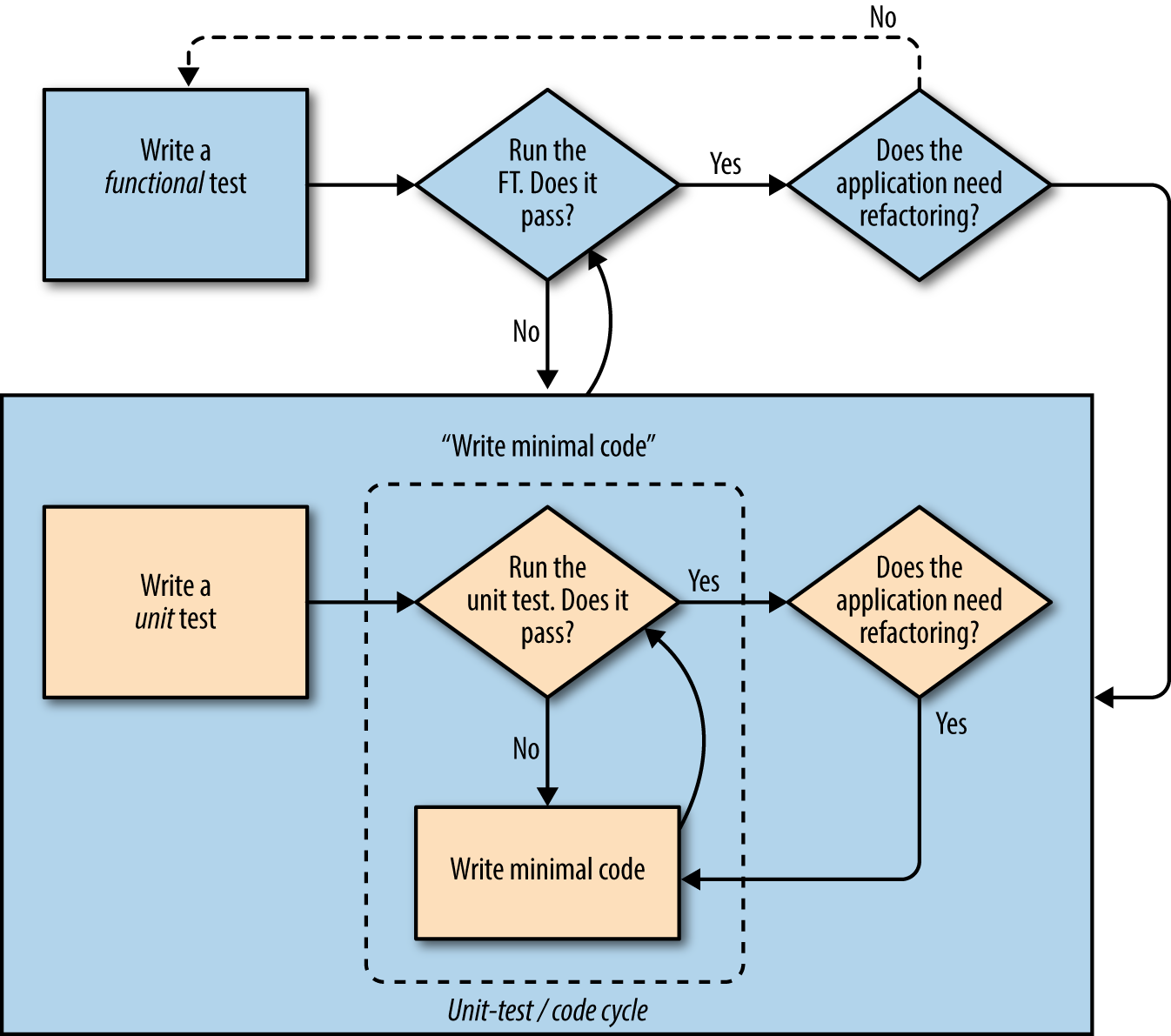

The TDD approach I’m following wants our application to be covered by both types of test. Our workflow will look a bit like this:

We start by writing a functional test, describing the new functionality from the user’s point of view.

Once we have a functional test that fails, we start to think about how to write code that can get it to pass (or at least to get past its current failure). We now use one or more unit tests to define how we want our code to behave—the idea is that each line of production code we write should be tested by (at least) one of our unit tests.

Once we have a failing unit test, we write the smallest amount of application code we can, just enough to get the unit test to pass. We may iterate between steps 2 and 3 a few times, until we think the functional test will get a little further.

Now we can rerun our functional tests and see if they pass, or get a little further. That may prompt us to write some new unit tests, and some new code, and so on.

You can see that, all the way through, the functional tests are driving what development we do from a high level, while the unit tests drive what we do at a low level.

Does that seem slightly redundant? Sometimes it can feel that way, but functional tests and unit tests do really have very different objectives, and they will usually end up looking quite different.

Functional tests should help you build an application with the right functionality, and guarantee you never accidentally break it. Unit tests should help you to write code that’s clean and bug free.

Enough theory for now—let’s see how it looks in practice.

Let’s see how to write a unit test for our home page view. Open up the new file at lists/tests.py, and you’ll see something like this:

lists/tests.py

fromdjango.testimportTestCase# Create your tests here.

Django has helpfully suggested we use a special version of TestCase, which

it provides. It’s an augmented version of the standard unittest.TestCase,

with some additional Django-specific features, which we’ll discover over the

next few chapters.

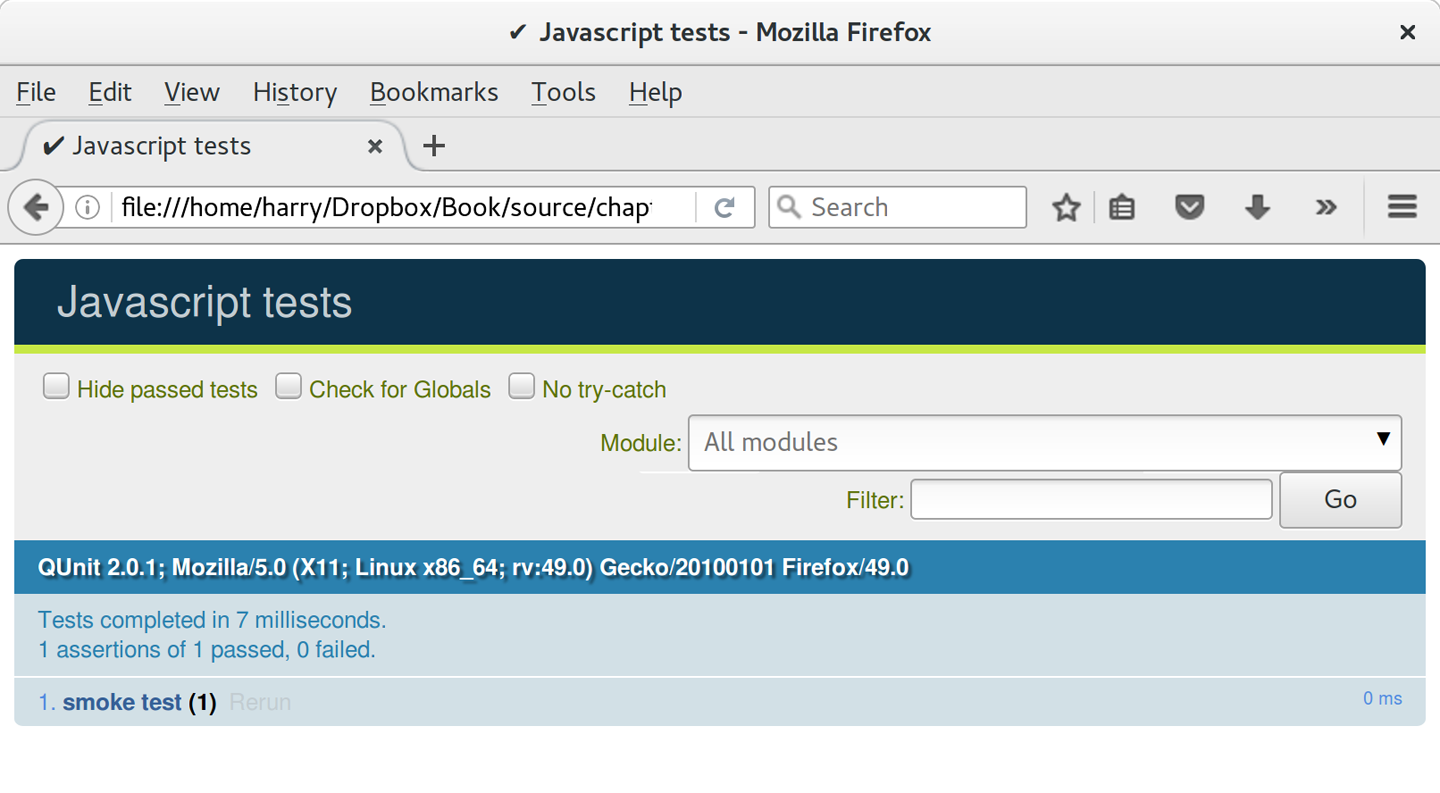

You’ve already seen that the TDD cycle involves starting with a test that fails, then writing code to get it to pass. Well, before we can even get that far, we want to know that the unit test we’re writing will definitely be run by our automated test runner, whatever it is. In the case of functional_tests.py, we’re running it directly, but this file made by Django is a bit more like magic. So, just to make sure, let’s make a deliberately silly failing test:

lists/tests.py

fromdjango.testimportTestCaseclassSmokeTest(TestCase):deftest_bad_maths(self):self.assertEqual(1+1,3)

Now let’s invoke this mysterious Django test runner. As usual, it’s a manage.py command:

$ python manage.py test

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_bad_maths (lists.tests.SmokeTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "...python-tdd-book/lists/tests.py", line 6, in test_bad_maths

self.assertEqual(1 + 1, 3)

AssertionError: 2 != 3

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.001s

FAILED (failures=1)

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Excellent. The machinery seems to be working. This is a good point for a commit:

$ git status # should show you lists/ is untracked $ git add lists $ git diff --staged # will show you the diff that you're about to commit $ git commit -m "Add app for lists, with deliberately failing unit test"

As you’ve no doubt guessed, the -m flag lets you pass in a commit message

at the command line, so you don’t need to use an editor. It’s up to you

to pick the way you like to use the Git command line; I’ll just show you

the main ones I’ve seen used. The key rule is: make sure you always review

what you’re about to commit before you do it.

Django is structured along a classic Model-View-Controller (MVC) pattern. Well, broadly. It definitely does have models, but its views are more like a controller, and it’s the templates that are actually the view part, but the general idea is there. If you’re interested, you can look up the finer points of the discussion in the Django FAQs.

Irrespective of any of that, as with any web server, Django’s main job is to decide what to do when a user asks for a particular URL on our site. Django’s workflow goes something like this:

An HTTP request comes in for a particular URL.

Django uses some rules to decide which view function should deal with the request (this is referred to as resolving the URL).

The view function processes the request and returns an HTTP response.

So we want to test two things:

Can we resolve the URL for the root of the site (“/”) to a particular view function we’ve made?

Can we make this view function return some HTML which will get the functional test to pass?

Let’s start with the first. Open up lists/tests.py, and change our silly test to something like this:

lists/tests.py

fromdjango.urlsimportresolvefromdjango.testimportTestCasefromlists.viewsimporthome_pageclassHomePageTest(TestCase):deftest_root_url_resolves_to_home_page_view(self):found=resolve('/')self.assertEqual(found.func,home_page)

What’s going on here?

resolve is the function Django uses internally to resolve

URLs and find what view function they should map to. We’re checking that

resolve, when called with “/”, the root of the site, finds a function

called home_page.

What function is that? It’s the view function we’re going to

write next, which will actually return the HTML we want. You can see from

the import that we’re planning to store it in lists/views.py.

So, what do you think will happen when we run the tests?

$ python manage.py test ImportError: cannot import name 'home_page'

It’s a very predictable and uninteresting error: we tried to import something we haven’t even written yet. But it’s still good news—for the purposes of TDD, an exception which was predicted counts as an expected failure. Since we have both a failing functional test and a failing unit test, we have the Testing Goat’s full blessing to code away.

It is exciting, isn’t it? Be warned, TDD means that long periods of anticipation are only defused very gradually, and by tiny increments. Especially since we’re learning and only just starting out, we only allow ourselves to change (or add) one line of code at a time—and each time, we make just the minimal change required to address the current test failure.

I’m being deliberately extreme here, but what’s our current test failure?

We can’t import home_page from lists.views? OK, let’s fix that—and only

that. In lists/views.py:

lists/views.py

fromdjango.shortcutsimportrender# Create your views here.home_page=None

“You must be joking!” I can hear you say.

I can hear you because it’s what I used to say (with feeling) when my colleagues first demonstrated TDD to me. Well, bear with me, and we’ll talk about whether or not this is all taking it too far in a little while. But for now, let yourself follow along, even if it’s with some exasperation, and see if our tests can help us write the correct code, one tiny step at a time.

We run the tests again:

$ python manage.py test

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

E

======================================================================

ERROR: test_root_url_resolves_to_home_page_view (lists.tests.HomePageTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "...python-tdd-book/lists/tests.py", line 8, in

test_root_url_resolves_to_home_page_view

found = resolve('/')

File ".../django/urls/base.py", line 27, in resolve

return get_resolver(urlconf).resolve(path)

File ".../django/urls/resolvers.py", line 392, in resolve

raise Resolver404({'tried': tried, 'path': new_path})

django.urls.exceptions.Resolver404: {'tried': [[<RegexURLResolver

<RegexURLPattern list> (admin:admin) ^admin/>]], 'path': ''}

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.002s

FAILED (errors=1)

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Our tests are telling us that we need a URL mapping. Django uses a file called urls.py to map URLs to view functions. There’s a main urls.py for the whole site in the superlists/superlists folder. Let’s go take a look:

superlists/urls.py

"""superlists URL ConfigurationThe `urlpatterns` list routes URLs to views. For more information please see:https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/1.11/topics/http/urls/Examples:Function views1. Add an import: from my_app import views2. Add a URL to urlpatterns: url(r'^$', views.home, name='home')Class-based views1. Add an import: from other_app.views import Home2. Add a URL to urlpatterns: url(r'^$', Home.as_view(), name='home')Including another URLconf1. Import the include() function: from django.conf.urls import url, include2. Add a URL to urlpatterns: url(r'^blog/', include('blog.urls'))"""fromdjango.conf.urlsimporturlfromdjango.contribimportadminurlpatterns=[url(r'^admin/',admin.site.urls),]

As usual, lots of helpful comments and default suggestions from Django.

If your urls.py looks different or if it mentions a function called

path instead of url, it’s because you’ve got the wrong version of

Django. This book is written for Django v1.11. Take another look at

the "Prerequisites and Assumptions" section and get the right version before you

go any further.

A url entry starts with a regular expression that defines which URLs it

applies to, and goes on to say where it should send those requests—either to

a view function you’ve imported, or maybe to another urls.py file somewhere

else.

The first example entry has the regular expression ^$, which means

an empty string—could this be the same as the root of our site, which we’ve

been testing with “/”? Let’s find out—what happens if we include it?

If you’ve never come across regular expressions, you can get away with just taking my word for it, for now—but you should make a mental note to go learn about them.

We’ll also get rid of the admin URL, because we won’t be using the Django admin site for now:

superlists/urls.py

fromdjango.conf.urlsimporturlfromlistsimportviewsurlpatterns=[url(r'^$',views.home_page,name='home'),]

Run the unit tests again, with python manage.py test:

[...] TypeError: view must be a callable or a list/tuple in the case of include().

That’s progress! We’re no longer getting a 404.

The traceback is messy, but the message at the end is telling us what’s going

on: the unit tests have actually made the link between the URL “/” and the

home_page = None in lists/views.py, and are now complaining that the

home_page view is not callable. And that gives us a justification for

changing it from being None to being an actual function. Every single code

change is driven by the tests!

Back in lists/views.py:

lists/views.py

fromdjango.shortcutsimportrender# Create your views here.defhome_page():pass

And now?

$ python manage.py test Creating test database for alias 'default'... . --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 1 test in 0.003s OK System check identified no issues (0 silenced). Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Hooray! Our first ever unit test pass! That’s so momentous that I think it’s worthy of a commit:

$ git diff # should show changes to urls.py, tests.py, and views.py $ git commit -am "First unit test and url mapping, dummy view"

That was the last variation on git commit I’ll show, the a and m flags

together, which adds all changes to tracked files and uses the commit message

from the command line.

git commit -am is the quickest formulation, but also gives you the

least feedback about what’s being committed, so make sure you’ve done a

git status and a git diff beforehand, and are clear on what changes are

about to go in.

On to writing a test for our view, so that it can be something more than a do-nothing function, and instead be a function that returns a real response with HTML to the browser. Open up lists/tests.py, and add a new test method. I’ll explain each bit:

lists/tests.py

fromdjango.urlsimportresolvefromdjango.testimportTestCasefromdjango.httpimportHttpRequestfromlists.viewsimporthome_pageclassHomePageTest(TestCase):deftest_root_url_resolves_to_home_page_view(self):found=resolve('/')self.assertEqual(found.func,home_page)deftest_home_page_returns_correct_html(self):request=HttpRequest()response=home_page(request)html=response.content.decode('utf8')self.assertTrue(html.startswith('<html>'))self.assertIn('<title>To-Do lists</title>',html)self.assertTrue(html.endswith('</html>'))

What’s going on in this new test?

We create an HttpRequest object, which is what Django will see when

a user’s browser asks for a page.

We pass it to our home_page view, which gives us a response. You won’t be

surprised to hear that this object is an instance of a class called

HttpResponse.

Then, we extract the .content of the response. These are the raw bytes,

the ones and zeros that would be sent down the wire to the user’s browser.

We call .decode() to convert them into the string of HTML that’s being

sent to the user.

We want it to start with an <html> tag which gets closed at the end.

And we want a <title> tag somewhere in the middle, with the words

“To-Do lists” in it—because that’s what we specified in our functional test.

Once again, the unit test is driven by the functional test, but it’s also much closer to the actual code—we’re thinking like programmers now.

Let’s run the unit tests now and see how we get on:

TypeError: home_page() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

We can start to settle into the TDD unit-test/code cycle now:

In the terminal, run the unit tests and see how they fail.

In the editor, make a minimal code change to address the current test failure.

And repeat!

The more nervous we are about getting our code right, the smaller and more minimal we make each code change—the idea is to be absolutely sure that each bit of code is justified by a test.

This may seem laborious, and at first, it will be. But once you get into the swing of things, you’ll find yourself coding quickly even if you take microscopic steps—this is how we write all of our production code at work.

Let’s see how fast we can get this cycle going:

Minimal code change:

lists/views.py

defhome_page(request):pass

Tests:

html = response.content.decode('utf8')

AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'content'

Code—we use django.http.HttpResponse, as predicted:

lists/views.py

fromdjango.httpimportHttpResponse# Create your views here.defhome_page(request):returnHttpResponse()

Tests again:

self.assertTrue(html.startswith('<html>'))

AssertionError: False is not true

Code again:

lists/views.py

defhome_page(request):returnHttpResponse('<html>')

Tests:

AssertionError: '<title>To-Do lists</title>' not found in '<html>'

Code:

lists/views.py

defhome_page(request):returnHttpResponse('<html><title>To-Do lists</title>')

Tests—almost there?

self.assertTrue(html.endswith('</html>'))

AssertionError: False is not true

Come on, one last effort:

lists/views.py

defhome_page(request):returnHttpResponse('<html><title>To-Do lists</title></html>')

Surely?

$ python manage.py test Creating test database for alias 'default'... .. --------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 2 tests in 0.001s OK System check identified no issues (0 silenced). Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Yes! Now, let’s run our functional tests. Don’t forget to spin up the dev server again, if it’s not still running. It feels like the final heat of the race here; surely this is it…could it be?

$ python functional_tests.py

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later (__main__.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "functional_tests.py", line 19, in

test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later

self.fail('Finish the test!')

AssertionError: Finish the test!

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 1.609s

FAILED (failures=1)

Failed? What? Oh, it’s just our little reminder? Yes? Yes! We have a web page!

Ahem. Well, I thought it was a thrilling end to the chapter. You may still be a little baffled, perhaps keen to hear a justification for all these tests, and don’t worry, all that will come, but I hope you felt just a tinge of excitement near the end there.

Just a little commit to calm down, and reflect on what we’ve covered:

$ git diff # should show our new test in tests.py, and the view in views.py $ git commit -am "Basic view now returns minimal HTML"

That

was quite a chapter! Why not try typing git log, possibly using the

--oneline flag, for a reminder of what we got up to:

$ git log --oneline a6e6cc9 Basic view now returns minimal HTML 450c0f3 First unit test and url mapping, dummy view ea2b037 Add app for lists, with deliberately failing unit test [...]

Not bad—we covered:

Starting a Django app

The Django unit test runner

The difference between FTs and unit tests

Django URL resolving and urls.py

Django view functions, request and response objects

And returning basic HTML

Now that we’ve seen the basics of TDD in action, it’s time to pause and talk about why we’re doing it.

I’m imagining several of you, dear readers, have been holding back some seething frustration—perhaps some of you have done a bit of unit testing before, and perhaps some of you are just in a hurry. You’ve been biting back questions like:

Aren’t all these tests a bit excessive?

Surely some of them are redundant? There’s duplication between the functional tests and the unit tests.

I mean, what are you doing importing django.urls.resolve in your

unit tests? Isn’t that testing Django—that is, testing third-party code? I

thought that was a no-no?

Those unit tests seemed way too trivial—testing one line of declaration, and a one-line function that returns a constant! Isn’t that just a waste of time? Shouldn’t we save our tests for more complex things?

What about all those tiny changes during the unit-test/code cycle? Surely we

could have just skipped to the end? I mean, home_page = None!? Really?

You’re not telling me you actually code like this in real life?

Ah, young grasshopper. I too was once full of questions like these. But only because they’re perfectly good questions. In fact, I still ask myself questions like these, all the time. Does all this stuff really have value? Is this a bit of a cargo cult?

Ultimately, programming is hard. Often, we are smart, so we succeed. TDD is there to help us out when we’re not so smart. Kent Beck (who basically invented TDD) uses the metaphor of lifting a bucket of water out of a well with a rope: when the well isn’t too deep, and the bucket isn’t very full, it’s easy. And even lifting a full bucket is pretty easy at first. But after a while, you’re going to get tired. TDD is like having a ratchet that lets you save your progress, take a break, and make sure you never slip backwards. That way you don’t have to be smart all the time.

OK, perhaps in general, you’re prepared to concede that TDD is a good idea, but maybe you still think I’m overdoing it? Testing the tiniest thing, and taking ridiculously many small steps?

TDD is a discipline, and that means it’s not something that comes naturally; because many of the payoffs aren’t immediate but only come in the longer term, you have to force yourself to do it in the moment. That’s what the image of the Testing Goat is supposed to illustrate—you need to be a bit bloody-minded about it.

Where were we at the end of the last chapter? Let’s rerun the test and find out:

$ python functional_tests.py

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later (__main__.NewVisitorTest)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "functional_tests.py", line 19, in

test_can_start_a_list_and_retrieve_it_later

self.fail('Finish the test!')

AssertionError: Finish the test!

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 1.609s

FAILED (failures=1)

Did you try it, and get an error saying Problem loading page or

Unable to connect? So did I. It’s because we forgot to spin up the dev

server first using manage.py runserver. Do that, and you’ll get the failure

message we’re after.

One of the great things about TDD is that you never have to worry about forgetting what to do next—just rerun your tests and they will tell you what you need to work on.

“Finish the test”, it says, so let’s do just that! Open up functional_tests.py and we’ll extend our FT:

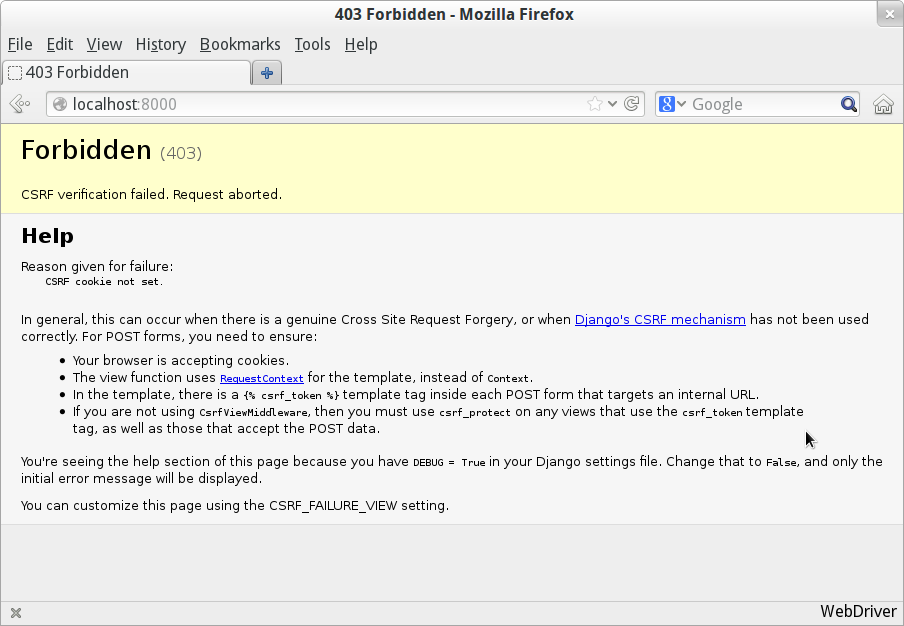

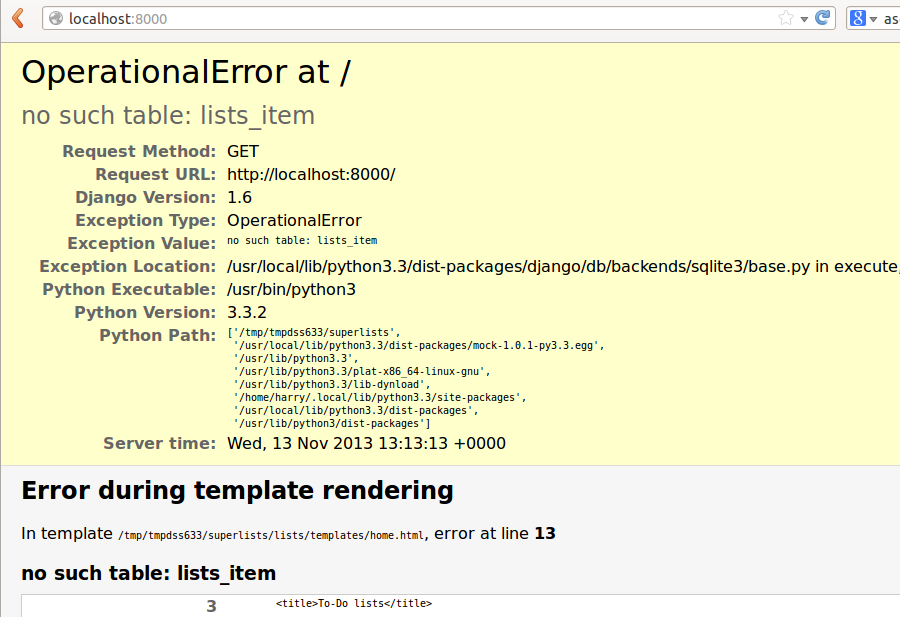

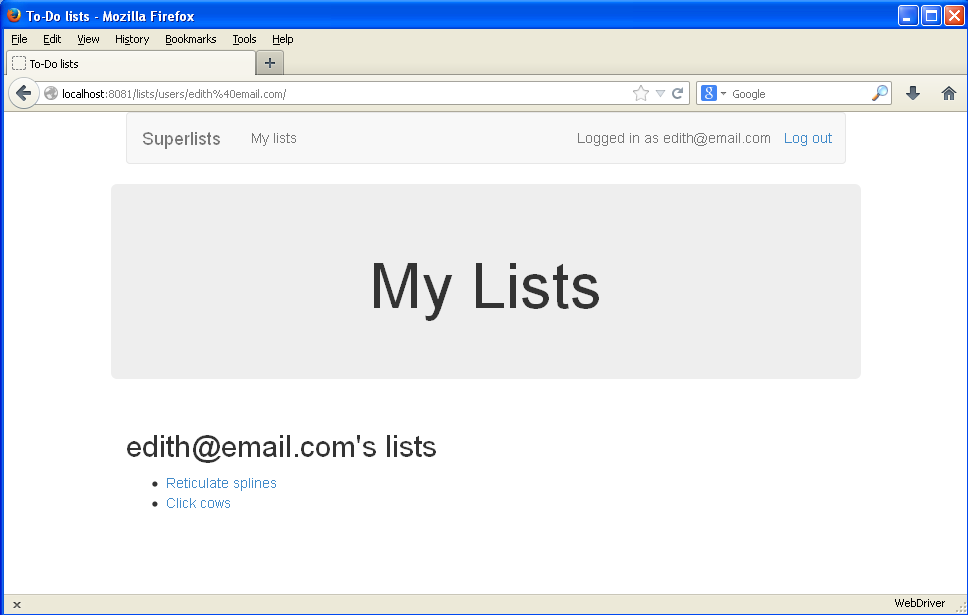

functional_tests.py