The counterfeit coin puzzle: It is a classical balance puzzle proposed by mathematician E. D. Schell in 1945. It is about balancing coins to determine which holds a different value (counterfeit) using a balance scale and a limited number of tries.

The Mermin-Peres Magic Square game: This is an example of quantum pseudo-telepathy or the ability of players to achieve outcomes that would only be possible if they mysteriously communicate during the game.

In both cases, quantum computation gives quasi-magical abilities to the players, just as if they were cheating all along. Let’s see how.

Counterfeit Coin Puzzle

- 1.

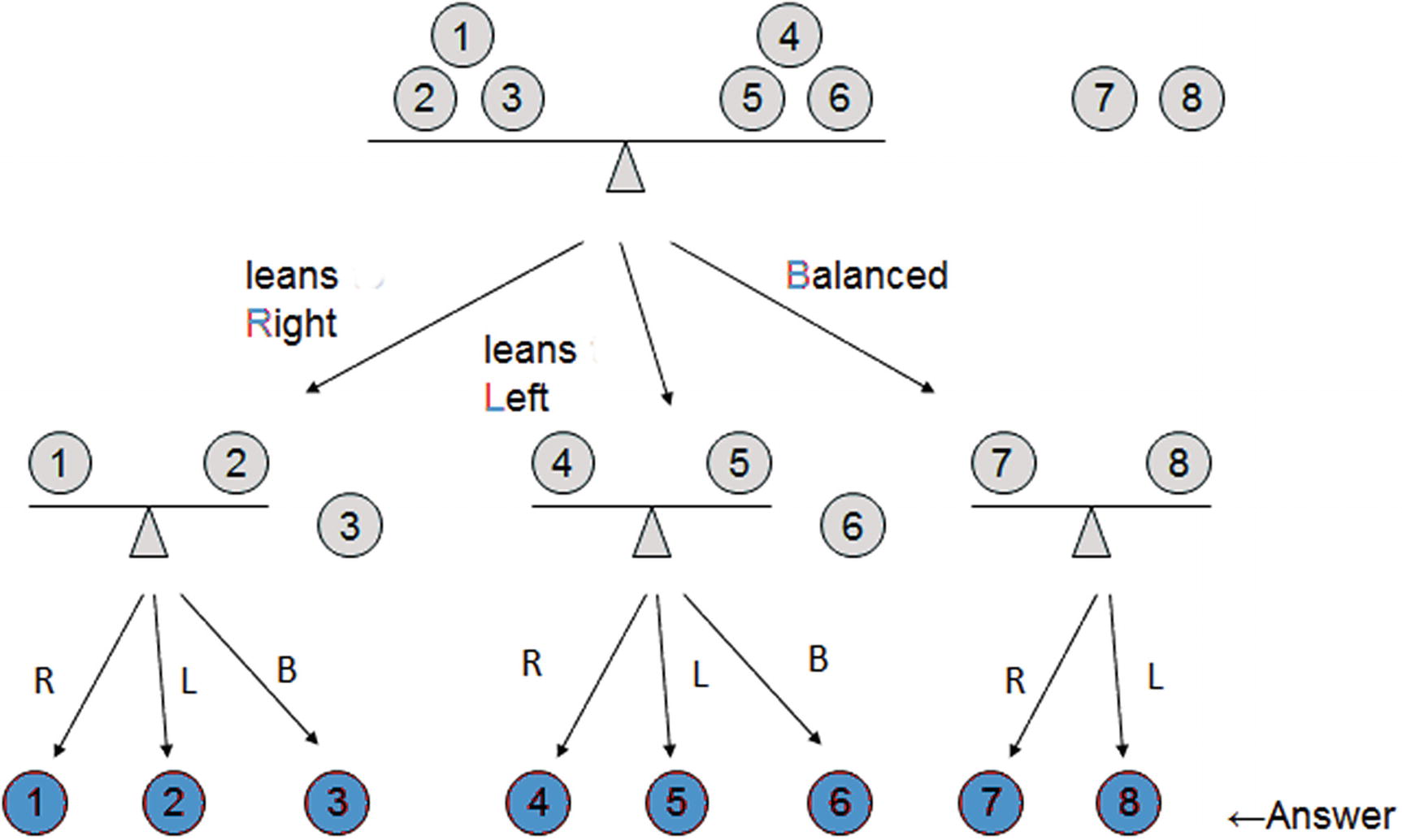

Given eight coins, put coins 1-3 on the left side of the balance and 4-6 on the right side. Leave the last two coins 7 and 8 on the side and weight.

- 2.If the balance leans right, the counterfeit is among 1-3 (left). Remember that the fake coin is lighter. Thus take out the last coin from the left (3) and weight again (for the second time).

If the beam leans right, the counterfeit is 1. Stop.

If the beam leans left, the counterfeit is 2. Stop.

If the beam is balanced, the counterfeit is 3. Stop.

- 3.If the balance leans left, the counterfeit is among 4-6. Take out the last coin (6) and weight again.

If the beam leans right, the counterfeit is 4. Stop.

If the beam leans left, the counterfeit is 5. Stop.

If the beam is balanced, the counterfeit is 6. Stop.

- 4.If the beam is balanced, the counterfeit is either 7 or 8. Put 7 and 8 in the balance and weight again.

If the beam leans right, the counterfeit is 7. Stop.

If the beam leans left, the counterfeit is 8. Stop.

Counterfeit puzzle solution for eight coins

Tip

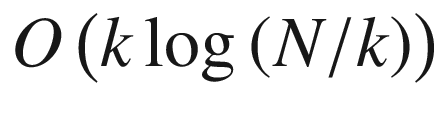

It has been proven that the minimal number of tries required to find a single counterfeit coin using the balance beam in a classical computer is two.

Counterfeit Coin, the Quantum Way

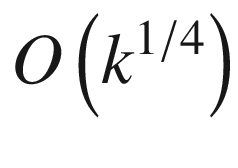

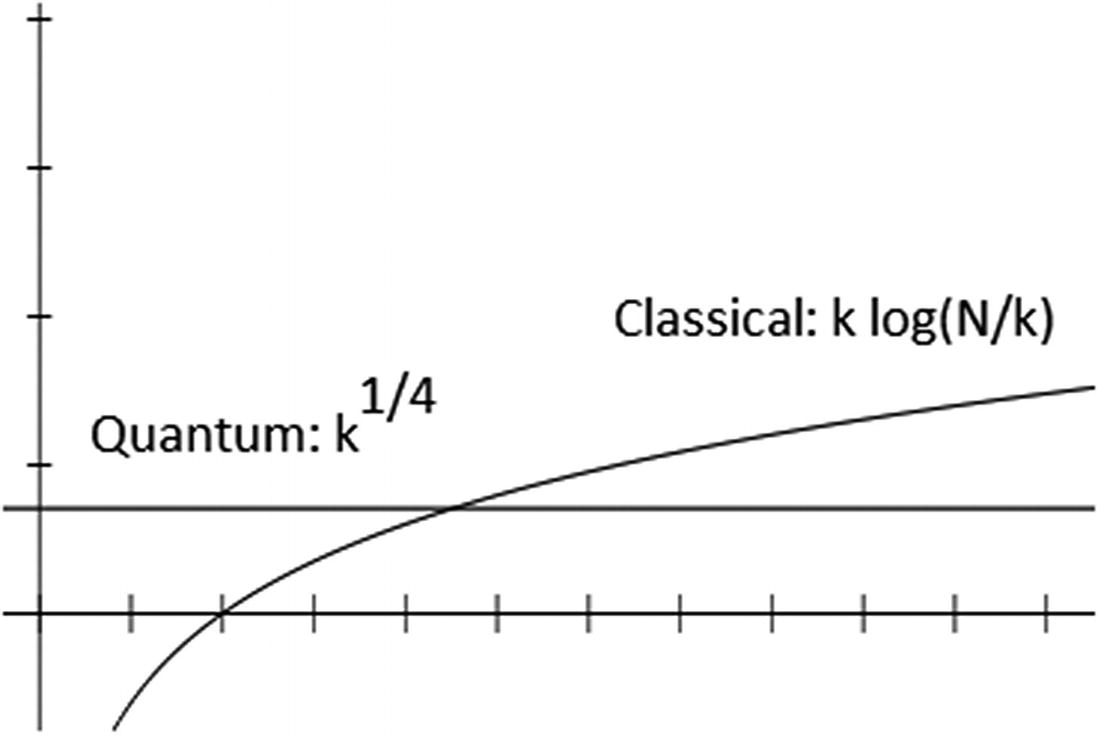

Quantum vs. classical time complexities for the counterfeit coin puzzle

Tip

The quantum counterfeit coin algorithm is an example of quartic speedup over its classical counterpart.

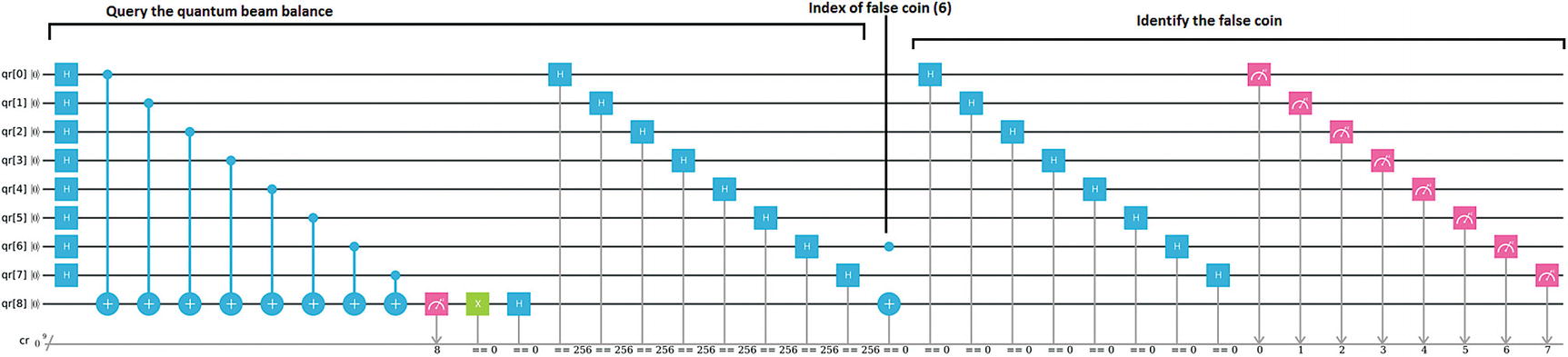

Thus Figure 7-2 shows the power of a quantum algorithm over its classical counterpart for the counterfeit coin puzzle. Now, let’s dig deeper. A quantum algorithm to find a single counterfeit coin (k = 1) can be summarized in three stages: query the quantum beam balance, construct the quantum balance, and identify the false coin.

Step 1: Query the Quantum Beam Balance

N (# of coins) | F (index of false coin) | Query string | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

8 | 3 | 11101111 | Balanced (0) |

8 | 3 | 11111111 | Tilted (1) |

- 1.

Use two quantum registers to query the quantum balance, where the first register is for the query string and the second register for the result.

- 2.

Prepare the superposition of all binary query strings with even number of 1s.

- 3.

To obtain the superposition of states of even number of 1s, perform a Hadamard transform on the basis state |0>, and check if the Hamming weight of |x| is even. It can be shown that the Hamming weight of |x| is even if and only if x1 ⊕ x2 ⊕ … ⊕ xN = 0.

Tip

The Hamming weight (hw) of a string is the number of symbols that are different from the zero symbol of the alphabet used. For example, hw(11101) = 4, hw(11101000) = 4, hw(000000) = 0.

- 4.

Finally, measure the second register, and if |0> is observed, then the first register is the superposition of all binary query strings we want. If we get |1> then repeat the procedure until |0> is observed.

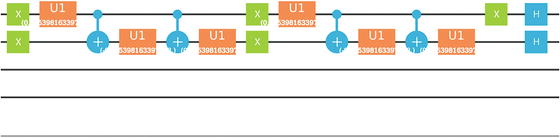

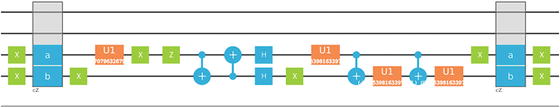

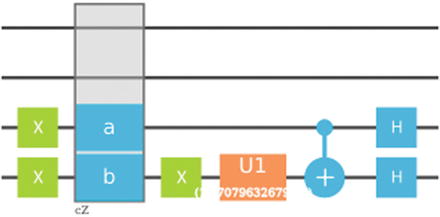

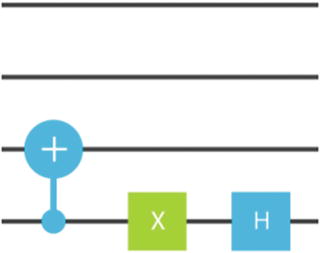

Note that each repetition is guaranteed to succeed with probability exactly half. Hence, after several repetitions, we should be able to obtain the desired superposition state. Listing 7-1 shows an implementation of a quantum program to query the beam balance with the corresponding graphical circuit shown in Figure 7-3.

Note

For the sake of clarity, the full counterfeit coin program has been broken in Listings 7-1 thru 7-3. Although you should be able to join the sections to run the program, a full listing is available from the source at Workspace\Ch07\p_counterfeitcoin.py.

Script to Query the Quantum Beam Balance

Quantum circuit for the counterfeit coin puzzle with N = 8, k = 1, and fake at index 6 (Note: For full-size viewing, this graph is included in the source code download)

Step 2: Construct the Quantum Balance

In the previous section, we constructed the superposition of all binary query strings whose Hamming weights are even. In this step, we construct the quantum beam by setting the position of the false coin. Thus given k is the position of the false coin with regard to the binary string |x1, x2, …, xN>|0>, the quantum beam balance returns

|x1, x2, … , xN> |0⊕xk>

Construct the Quantum Beam Balance

Step 3: Identify the False Coin

Identify the False Coin

If the leftmost bit is 0, then we succeed in identifying the false coin.

If the leftmost bit is 1, we failed to obtain the desired superposition and must repeat the process from the beginning.

Counterfeit Coin Puzzle Main Container Script

Generalization for Any Number of False Coins

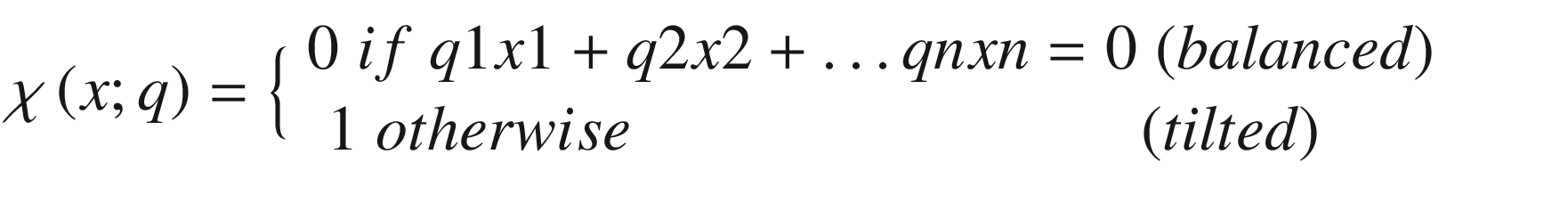

Given an input of N bits x = x1x2…xn Є {0, 1}N.

Construct a query string of N tri-bits such that q = q1q2…qn ∈ {0, 1, −1}N with the same number of 1s and -1s.

The answer is 1 bit such that

.

.

Tip

An Oracle is the portion of an algorithm regarded as a black box. It is used to simplify circuits and provide complexity comparisons between quantum and classical algorithms. A good Oracle should provide speed, generality, and feasibility.

B-Oracle for N = 6 and k = 2 )

All in all, the counterfeit puzzle is the quintessential example of quartic speedup of a quantum algorithm over its classical counterpart. In the next section, we look at another bizarre quasi-magical puzzle called the Mermin-Peres Magic Square.

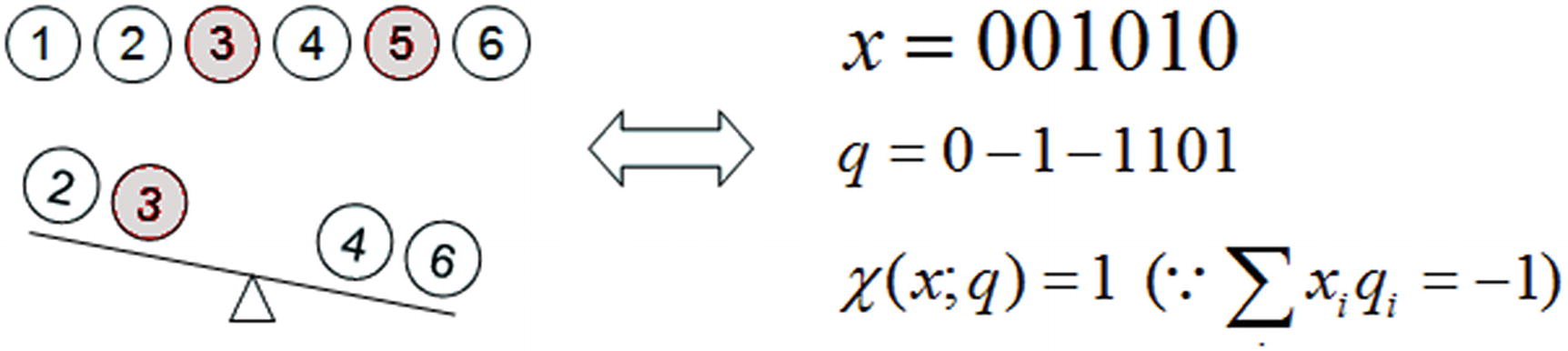

Mermin-Peres Magic Square

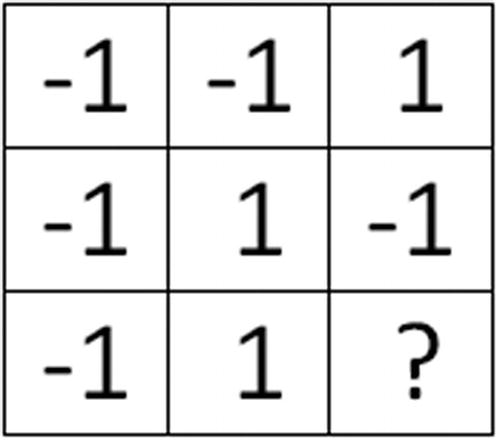

Mermin-Peres Magic Square

All entries are either 0 or 1 such that the sum of entries on each row is even, and the sum of each column is odd. The game is called the magic square because such square is impossible; as shown in Figure 7-5, there is no valid combination where the sum of rows is even and the sum of columns is odd (try it yourself with pen and paper). This is due to the odd number of entries in the matrix.

The referee sends an integer a Є {1,2,3} to Alice and another b Є {1,2,3} to Bob. Alice must reply with the a-th row of the square. Bob must reply with the b-th column.

Alice and Bob win if the sum of Alice’s entries is even, the sum of Bob’s is odd, and their intersecting answer is the same. Otherwise, the referee wins.

Prior to the start, Alice and Bob can strategize and share information. For example, they could decide to answer using the matrix in Figure 7-5. However they are not allowed to communicate during the game.

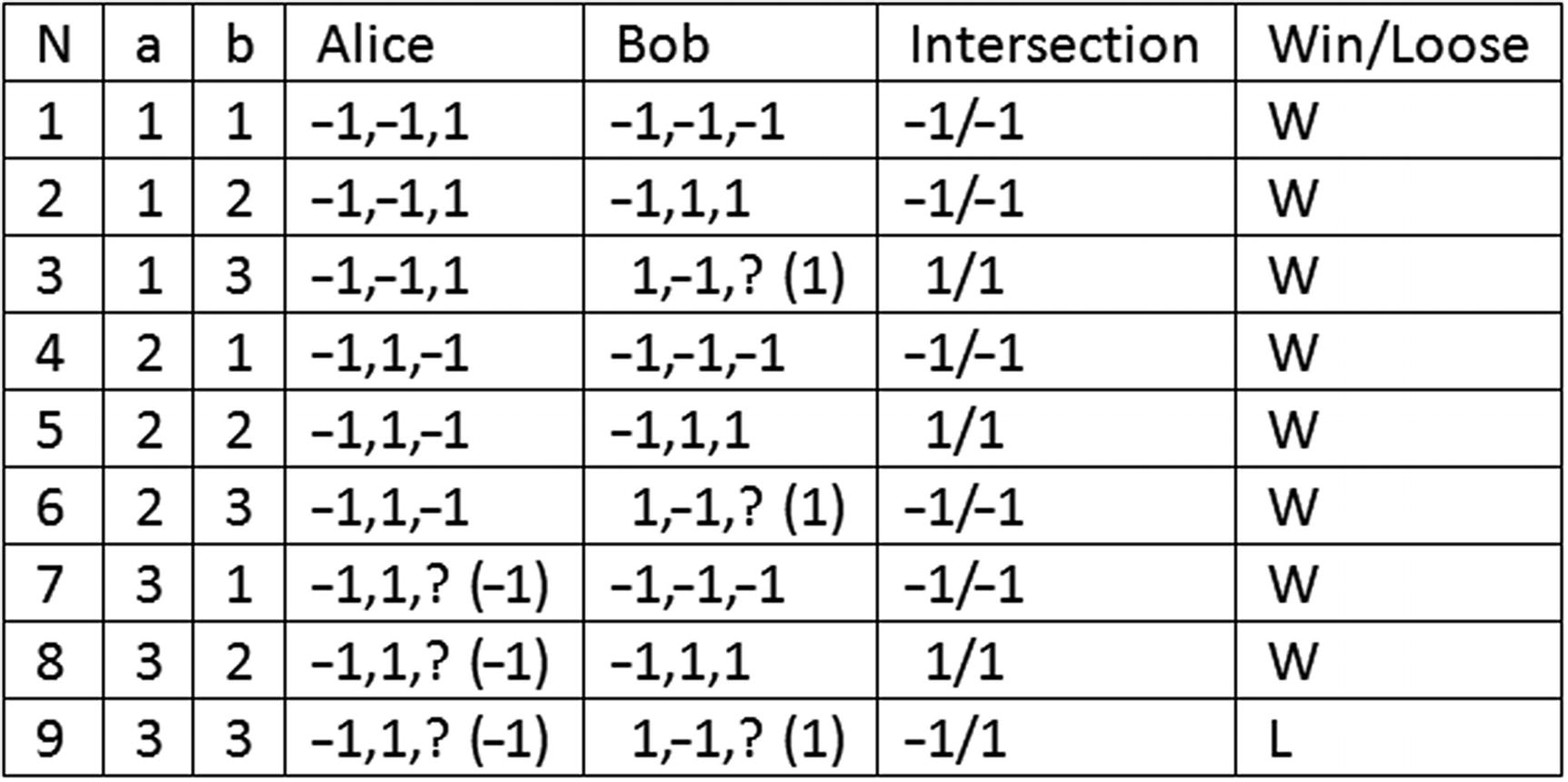

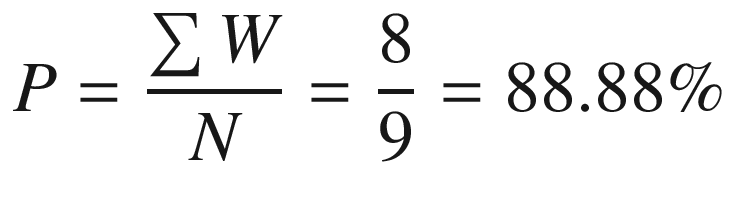

For example, in the preceding matrix, if the referee sends a = 1 to Alice and b = 2 to Bob, Alice would reply with 110 (row 1) and Bob with 100 (column 2). The element in the intersection of the answers (row 1-column 2) is the same (1) so they win the game. It can be shown that in a classical setting, the winning probability for Alice and Bob is at most 8/9. That is, there are eight out of nine permutations in the square for victory. Therefore Alice and Bob’s winning probability is at most 88.8%.

Let’s put this assertion to the test with a neat exercise to prove that indeed the classical winning probability for the magic square is at most 8/9 (88.88%).

Mermin-Peres Magic Square Exercise

- 1.

Construct a magic square similar to Figure 7-5 using the binary code (1, -1) instead of (1, 0) where the product of the row elements is 1 (even), and the product of the column elements is -1 (odd). Confirm that in fact this is not possible.

- 2.Create a permutation table for the referee values for a and b using the square in step 1 including

A permutation count number.

The values for a, b.

Alice and Bob’s response.

The intersection of Alice and Bob’s response. Remember that it must be equal for them to win.

The result of the game iteration: Win = W, Loose = L.

- 3.

Finally calculate the winning probability and prove that it is at most 8/9. Note: Answers are at the end of the section .

Quantum Winning Strategy

Shared entangled state: This is the key for Alice and Bob to win 100% of the time.

Unitary transformations for Alice and Bob’s inputs: These provide the responses to be sent back to the referee.

Measure in the computational basis: The final stage to construct a final response.

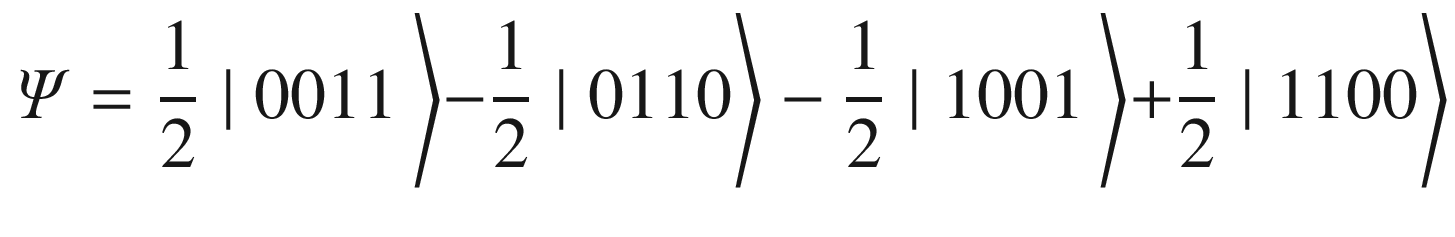

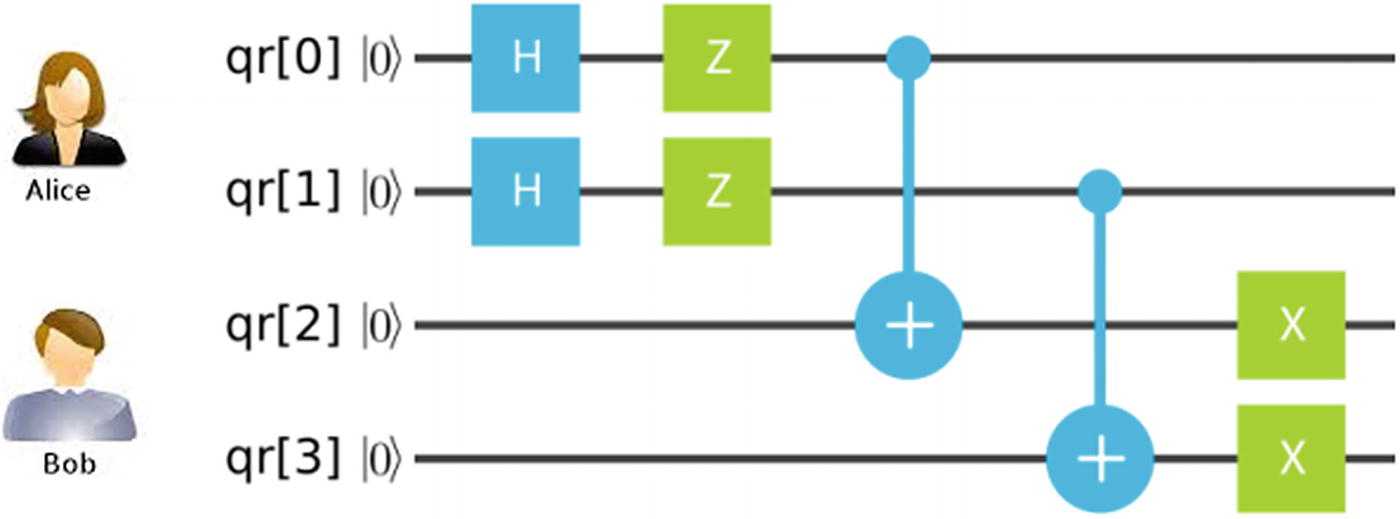

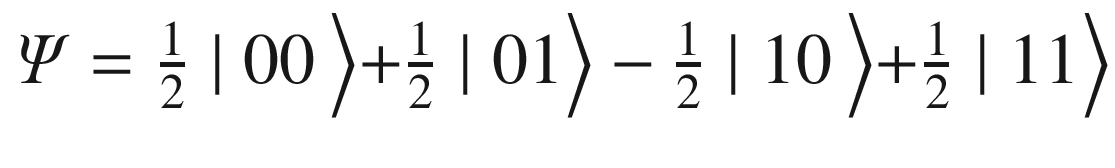

Shared Entangled State

Entangled state for the magic square

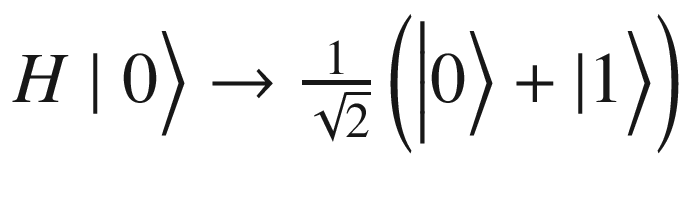

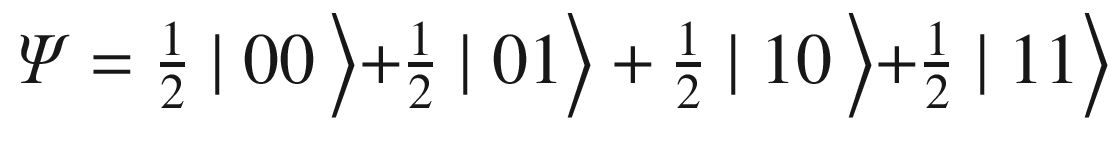

We know that the Hadamard maps the basis state

. Thus applying for the first 2 qubits yields

. Thus applying for the first 2 qubits yields  .

.Next apply a Z gate to the first 2 qubits. Remember that Z leaves the 0 state unchanged and maps 1 to -1 (flipping the sign of the preceding third term). At this stage the state becomes

.

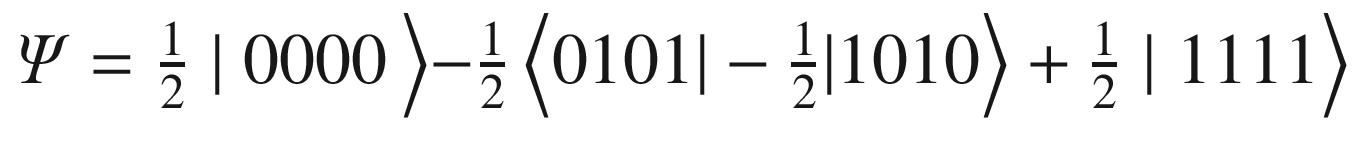

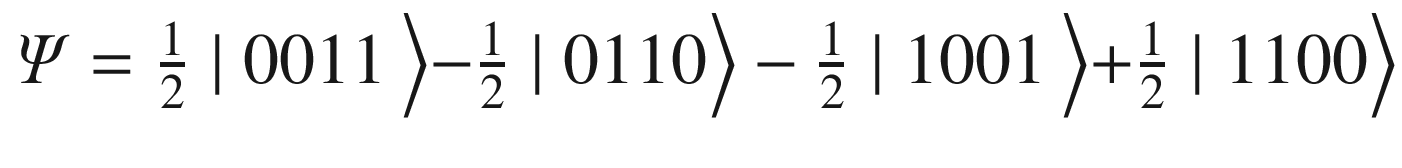

.Next apply the CNOT gate to entangle qubits 0-2 and 1-3:

.

.Finally flip the last 2 qubits with the X gate for

.

.

Quantum Winning Strategy Entangled State

With the shared entangled state, Alice and Bob can now start the game and receive their inputs from the referee.

Unitary Transformations

![$$ A1=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& 0& 0& 1\\ {}0& -i& 1& 0\\ {}0& i& 1& 0\\ {}1& 0& 0& i\end{array}\right],A2=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& 1& 1& i\\ {}-i& 1& -1& i\\ {}i& 1& 1& -i\\ {}-i& 1& -1& -i\end{array}\right],A3=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}-1& -1& -1& 1\\ {}1& 1& -1& 1\\ {}1& -1& 1& 1\\ {}1& -1& -1& -1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_Equd.png)

![$$ B1=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& -i& 1& 1\\ {}-i& -i& 1& -1\\ {}1& 1& -i& i\\ {}-i& i& 1& 1\end{array}\right],B2=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}-1& i& 1& i\\ {}1& i& 1& -i\\ {}1& -i& 1& i\\ {}-1& -i& 1& -i\end{array}\right],B3=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}1& 0& 0& 1\\ {}-1& 0& 0& 1\\ {}0& 1& 1& 0\\ {}0& 1& -1& 0\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_Eque.png)

Note

Remember that by applying the preceding transformations to their entangled states, Alice and Bob are able to construct the first 2 bits of their respective responses to the referee.

Unitary Transformations for Alice and Bob

Table 7-1 shows quantum circuits for the unitary transformations A1-3, B1-3 for IBM Q Experience Composer.

Quantum Circuits for the Unitary Transformations in Listing 7-6

Transformation | Circuit |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Table 7-1 note that A3 is not included due to the fact that the Composer does not support the swap gate required by Listing 7-6. This does not mean the quantum program can’t be run in the simulator or real device however. It simply means the circuit cannot be created in the Composer. Thus for the final step, Alice and Bob measure their qubits in the computational basis .

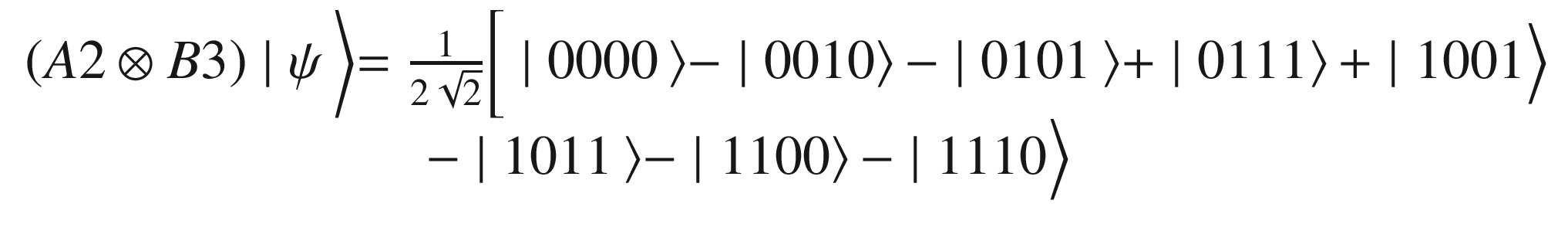

Measure in the Computational Basis

Answer Permutations for a = 2, b =3 of the Magic Square

ψ | Alice’s answer | Bob’s answer | Square |

|---|---|---|---|

|0000> | 000 | 001 |

|

|0010> | 000 | 100 |

|

|0101> | 011 | 010 |

|

|0111> | 011 | 111 |

|

|1001> | 101 | 010 |

|

|1011> | 101 | 111 |

|

|1100> | 110 | 001 |

|

|1110> | 110 | 101 |

|

It loops through a[1,3] and b[1,3] inclusive.

For each (a, b), a circuit for Alice (Alice-a) and a circuit for Bob (Bob-b) are retrieved from Listing 7-6.

The shared entangled state ψ and Alice-a and Bob-b circuits are submitted for execution to the simulator or real quantum device.

Two bits are extracted for Alice and two for Bob from the answer such as {‘0011’: 1}.

The parity rules are applied: Alice’s sum must be even, and Bob’s sum must be odd.

Finally the answer is verified, and the winning probability is displayed.

Script for All Rounds of the Magic Square

Simplified Standard Output from a Run of All Rounds of the Magic Square

Note

If running in a real device, the winning probability will not be 100% due to environmental noise and gate error.

Answers for the Mermin-Peres Magic Square Exercise

- 1.

A magic square whose row product is even and whose column product is odd is given in the following presentation. Note that such square is not possible due to the odd number of cells.

- 2.

The permutation table for the square in answer 1 is

- 3.

Note that, in the previous step rows 7-9, Alice’s answer must be -1 so the product can be even (1). Plus, in columns 3, 6, and 9, Bob’s answer must be 1 so his product can be odd (−1). Finally, the probability is calculated by dividing the total number of wins by the total number of permutations. Thus

In this chapter you have learned how the power of quantum entanglement can provide significant speedups over classical computation. With a quantum beam balance, it is possible to achieve quartic speedups for classical puzzles like the counterfeit coin problem. For others, such as the magic square, entanglement gives a quasi-magical telepathy among players. Now, if only Brassard and colleagues could come up with a quantum winning strategy for Black Jack or Poker, we will all be making a killing in Vegas right now. All in all, this chapter has shown how quantum mechanics is as confusing, bizarre, and fascinating as always. It never fails to deliver.

In the next and final chapter, you will learn about arguably the most famous quantum algorithm of them all: the notorious Shor’s integer factorization. An algorithm that may crumble asymmetric cryptography!

![$$ A1=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& 0& 0& 1\\ {}0& -i& 1& 0\\ {}0& i& 1& 0\\ {}1& 0& 0& i\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq7.png)

![$$ A2=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& 1& 1& i\\ {}-i& 1& -1& i\\ {}i& 1& 1& -i\\ {}-i& 1& -1& -i\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq8.png)

![$$ B1=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}i& -i& 1& 1\\ {}-i& -i& 1& -1\\ {}1& 1& -i& i\\ {}-i& i& 1& 1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq9.png)

![$$ B2=\frac{1}{2}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}-1& i& 1& i\\ {}1& i& 1& -i\\ {}1& -i& 1& i\\ {}-1& -i& 1& -i\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq10.png)

![$$ B3=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cccc}1& 0& 0& 1\\ {}-1& 0& 0& 1\\ {}0& 1& 1& 0\\ {}0& 1& -1& 0\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq11.png)

![$$ \left[0\kern0.375em 0\kern0.375em \begin{array}{l}0\\ {}0\\ {}1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq12.png)

![$$ \left[0\kern0.5em 0\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}1\\ {}0\\ {}0\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq13.png)

![$$ \left[0\kern0.5em 1\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}1\\ {}1\\ {}0\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq14.png)

![$$ \left[0\kern0.5em 1\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}1\\ {}1\\ {}1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq15.png)

![$$ \left[1\kern0.5em 0\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}0\\ {}1\\ {}0\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq16.png)

![$$ \left[1\kern0.5em 0\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}1\\ {}1\\ {}1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq17.png)

![$$ \left[1\kern0.5em 1\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}0\\ {}0\\ {}1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq18.png)

![$$ \left[1\kern0.5em 1\kern0.5em \begin{array}{l}1\\ {}0\\ {}1\end{array}\right] $$](../images/469026_1_En_7_Chapter/469026_1_En_7_Chapter_TeX_IEq19.png)