Using qubits to represent ship positions in the board

How to calculate damage percentages using a quantum program to be run in the local, remote simulator or real quantum device

How to perform rotations on the X-axis of a single qubit using a partial NOT quantum gate

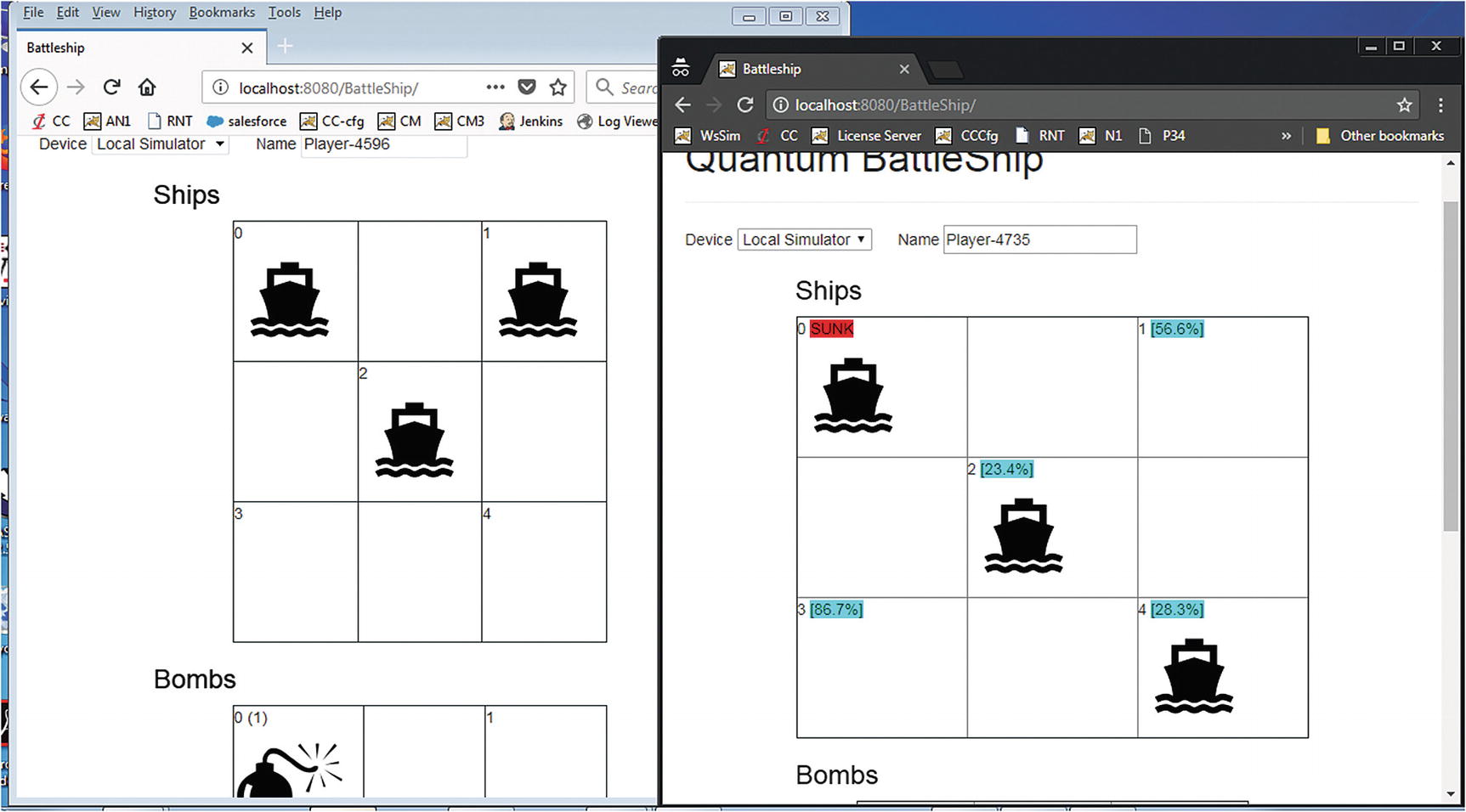

A browser-based user interface with interactive boards to place ship or bombs. The game mechanics remain the same nonetheless.

A CGI-based script using the Apache Web Server to consume game events and dispatch them to the quantum program.

A modified version of the original quantum program to perform partial NOT rotations on the qubits to calculate ship damage. Most of the original code remains intact.

You will learn how the original code can be modularized and reused for a different take of Quantum Battleship in the cloud. Let’s get started.

Quantum Battleship with a Twist

In this particular case, ship damage is calculated by doing a series of partial rotations on the X-axis (theta) using the number of bombs for that position. If the damage for a position (or ship) exceeds 95%, the ship is destroyed, and once the entire player’s fleet is smashed, a winner is declared and the game is over. This is just the standard battleship game we all played as children but using a quantum computer or simulator in the background.

Note

The game was written by James Wootton from the University of Basel and contributed to the QISKit Python tutorial. A modified version of the original code by Wootton is available from the source of this book at Workspace\Ch06\battleship\BattleShip.py (minus some unnecessary fancy text).

Let’s run the program and take a look at the game mechanics.

Setup Instructions

For CentOS 6 or 7 or any Fedora-like OS, activate your Python virtual environment. This is required only if you have multiple versions of Python, for example, 2.7 and 3.6. Remember that you must use 3.5 or later. Instructions on how to set up a virtual Python environment were covered in Chapter 3.

Copy the script Workspace/Ch06/battleship/BattleShip.py and the configuration file Qconfig.py from the book source to your workspace and execute it (as shown in the next fragment).

Let’s look at how the program works.

Initialization

It loads system libraries: sys and QuantumProgram required for all QISKit operations.

It makes sure you are using Python 3.5 or later.

It asks if you wish to use a simulator or a real quantum computer. It then sets the number of shots for the execution to the default 1024.

Script Initialization

Tip

To run a quantum program on a real device, you must place the configuration file (Qconfig.py) in the same location as the main script. The configuration contains your required API token and IBM Q Experience end point.

Now let’s place some ships in the board.

Set Ships in the Board

The script can bypass user choice and select random positions, or else the player must enter positions for three ships.

Positions are stored in the two-dimensional list shipPos where shipPos[0] contains the positions for player 1 and shipPos[1] contains positions for player 2. Remember that only three ships are allowed per player.

Setting Ships on the Board

The interesting stuff occurs in the main loop. Let’s take a look.

Main Loop and Results

It asks both players to place one bomb in position [0-4]. A count of the bomb is stored in a two-dimensional list of five elements (two players, five bomb counts). Note that the player can bomb the same position multiple times; thus if player 1 bombs position 0 twice, then bombs = [[2,0,0,0,0],[0,0,0,0,0]].

It creates a QuantumProgram to hold 5 qubits (1 per position in the board) and five classical registers to hold the measurement results.

If a bomb position matches the opposing player’s ship position (from the shipPos list), the damage is calculated by performing one rotation over the X-axis per bomb count using a single-qubit partial NOT gate: gridScript.u3(1/(ship +1) * math.pi, 0.0, 0.0, q[position]). Note that the effectiveness of the bomb also depends on which ship is bombed (0, 1, 2).

To complete the circuit, a measurement is performed in the qubit for the position and the result stored in the respective classical register: gridScript.measure(q[position], c[position]).

- Next, the program is executed in the target device, and the results stored in the two-dimensional list grid. For example, if position 0 for player 1 is bombed, then grid = [[1,0,0,0,0],[0,0,0,0,0]]. The following paragraph shows how this is done:results = Q_program.execute(["gridScript"], backend=device, shots=shots)grid[player] = results.get_counts("gridScript")

The results are checked for errors. If no errors, then a damage percentage between [0, 1] is calculated if the grid list contains a 1 for that position. The percentages are kept in the two-dimensional list damage. Thus damage [[0.95, 0, 0, 0, 0], [0, 0, 0, 0, 0]] indicates that player 1 ship in position 0 has been destroyed.

It finally presents the results to the players in a simple text-based interface. The process repeats itself until all ships are destroyed and a winner is declared (see Listing 6-3).

Battleship Main Loop

Game Standard Output for One Game Interaction

Thus the main loop continues until a winner is declared. All in all you have learned how a simple game can be implemented to make use of a quantum computer to perform simple damage calculations via rotations in the X-axis of a qubit. This version is rudimentary but interesting nonetheless. However we can do better; in the next section, we give this game an improved look and feel.

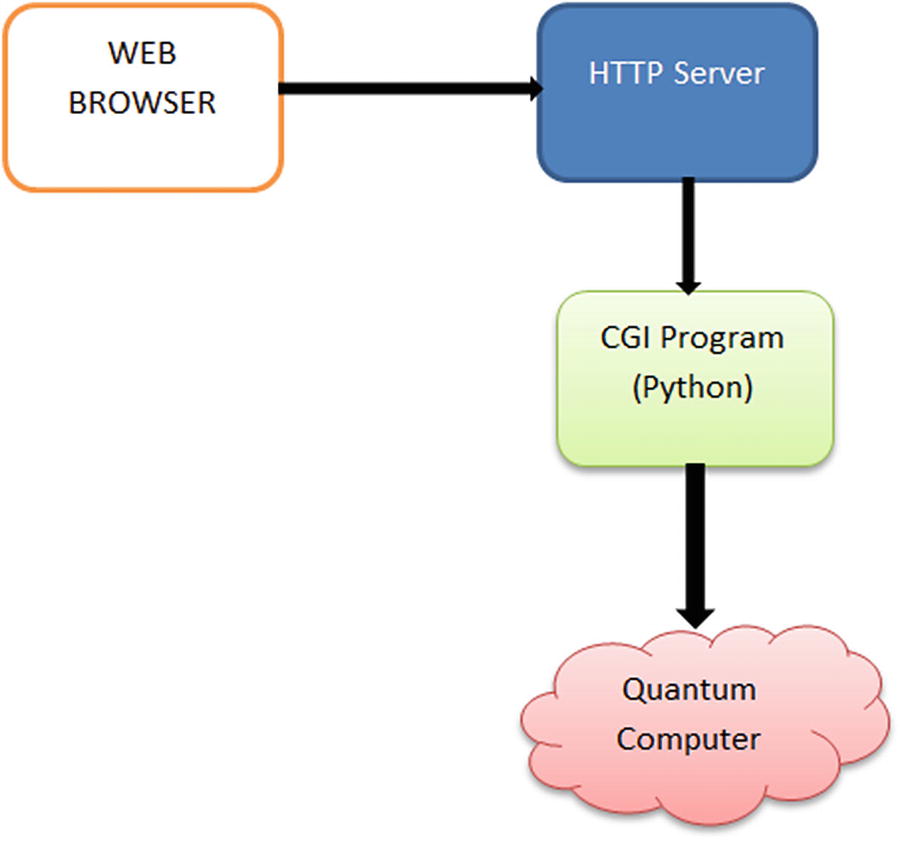

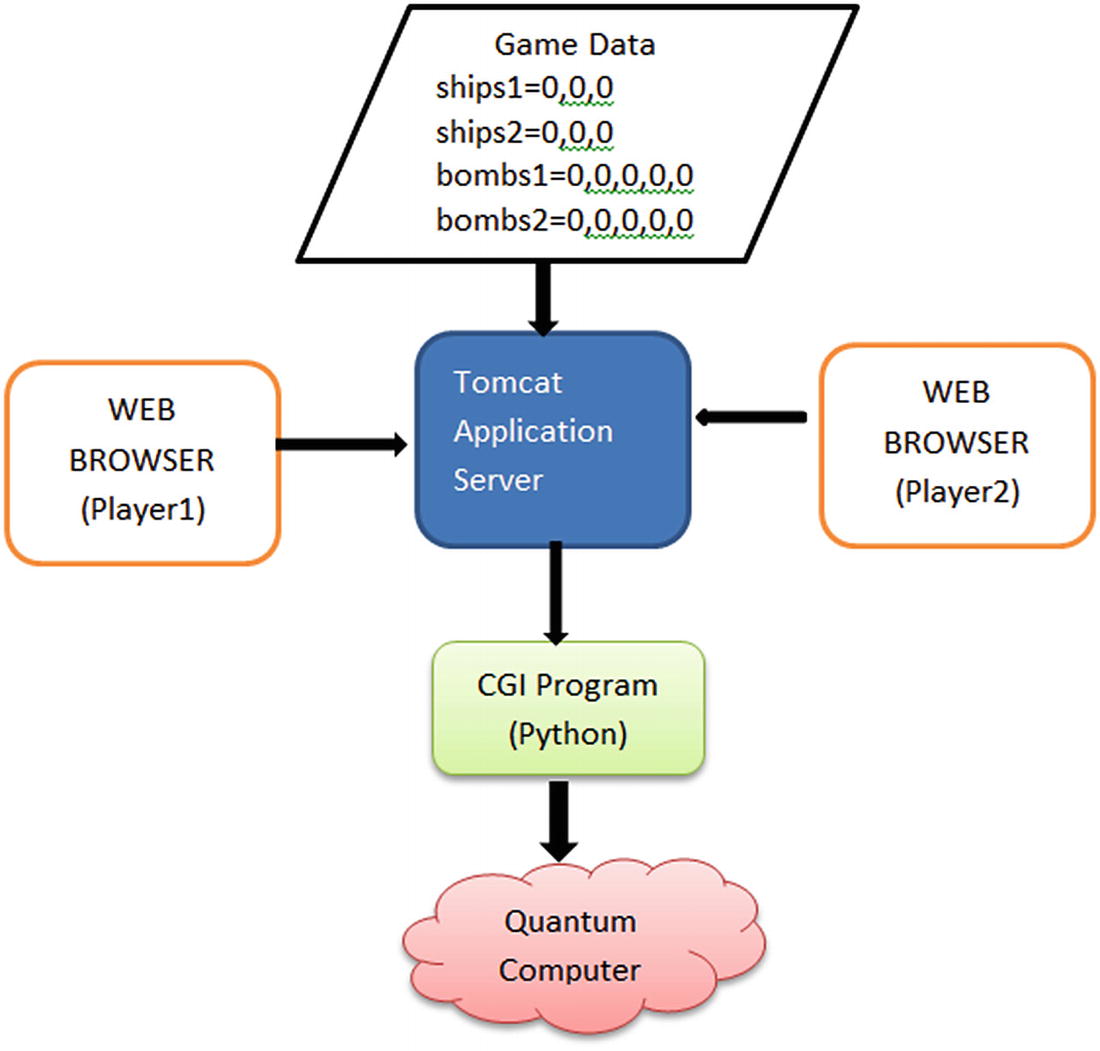

Cloud Battleship: Modifying for Remote Access

Layout for Quantum Battleship in the cloud

Ditch the boring text-based interface in favor of an HTML page that can be deployed in the cloud.

Use the Apache HTTP Server Common Gateway Interface (CGI) to deploy the quantum logic in a script using Python’s excellent CGI support.

Let the player select the device where to run the calculations: local simulator, remote simulator, or real quantum device.

Let’s do this in a series of exercises described in the next sections.

Exercise 1: Decouple the User Interface from the Game Logic

The first section of the script which reads the position of the ships for each player (a good chunk of code), being careful not to remove any data structures or variables.

All print statements and keyboard input statements.

The main while loop of the game that keeps asking for a position to bomb must be removed also. The script must terminate after it consumes data from the HTTP request. It cannot have infinite loops or else the request will hang.

- Add Python’s CGI support to the script so the data can be read from the HTTP request including

Ship positions for each player

Bomb positions and count for each player

Device where to run the quantum computations

The script must return a damage report (preferably in JSON) via the HTTP response for the browser to render in Javascript.

Note that most of the code will be reused: data structures, local variables, and quantum logic; it is just a matter of commenting all input and print statements. The solution to this (and each) exercise is shown at the end of this section.

Exercise 2: Build a Web Interface for the Ship-Bomb Boards

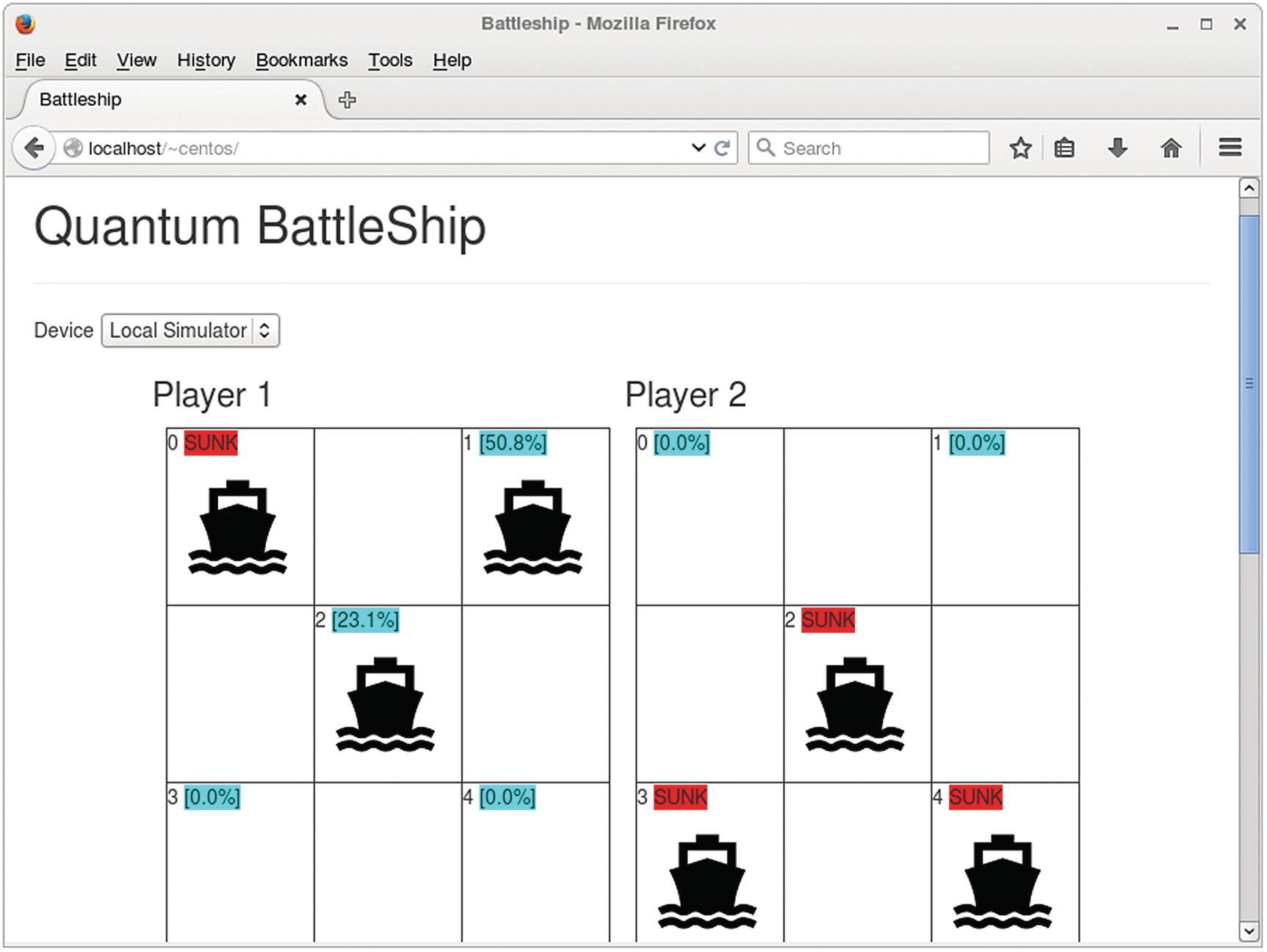

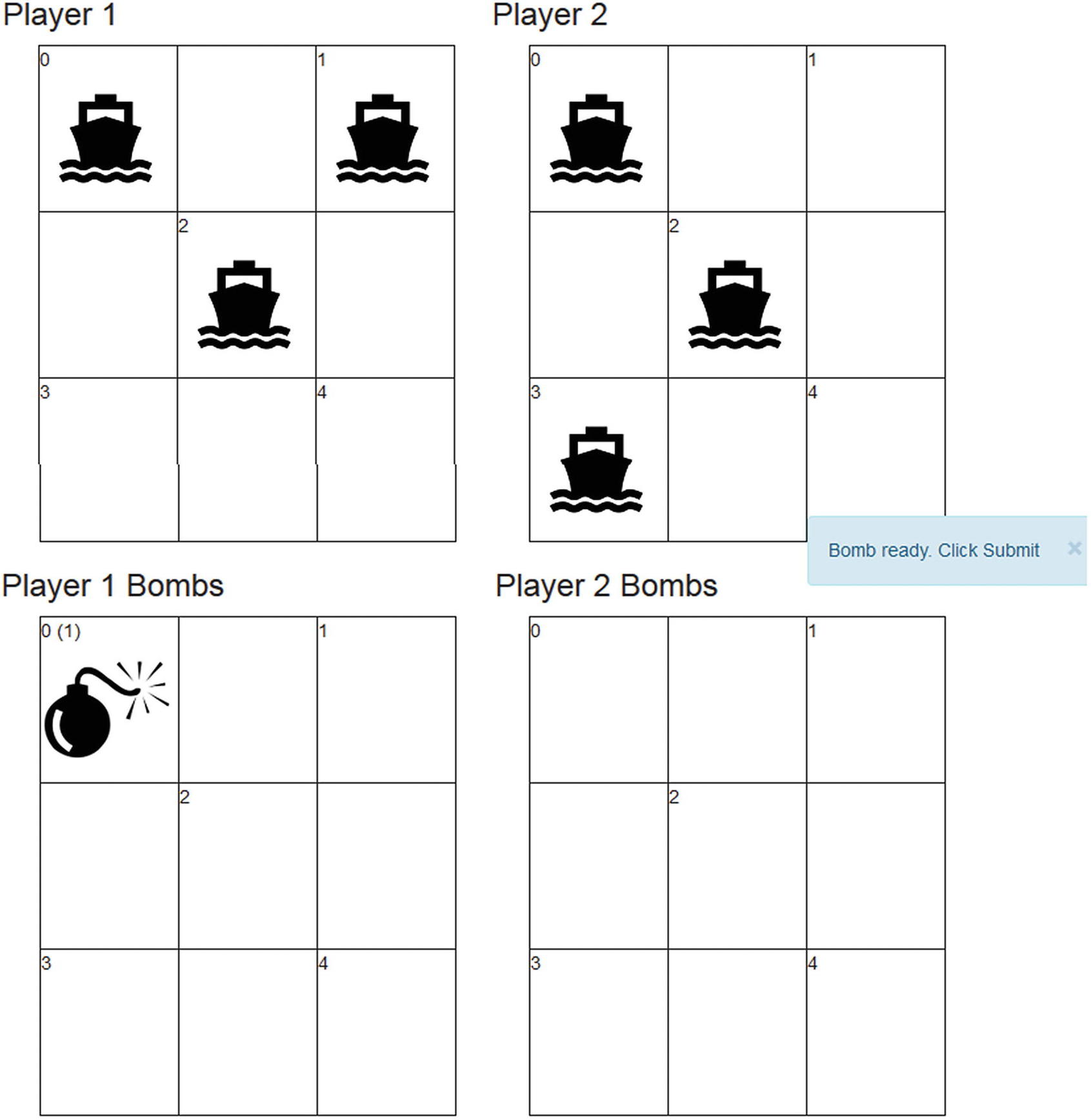

User interface for the new Quantum Battleship

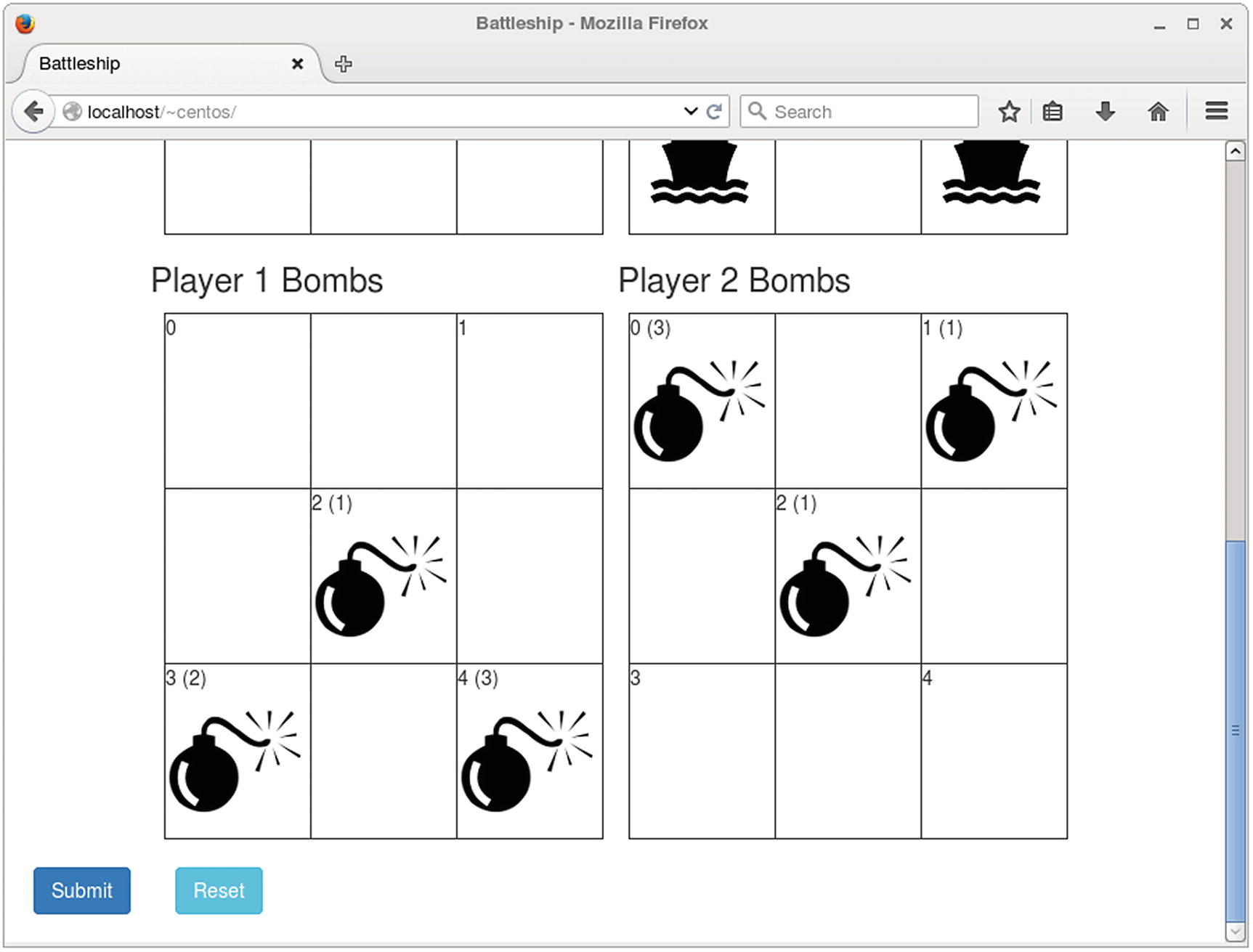

The HTML file will have four 3x3 boards. The top boards will be used to place three ships in five qubit locations. These will be implemented as HTML checkboxes (<INPUT TYPE=“checkbox”>). We will use CSS to replace the toggle button with an image, so when the player clicks the box, the ship image will be toggled instead.

The bottom boards will allow the players to place bombs in five locations, using the same CSS in the preceding paragraph, but they will be implemented as <INPUT TYPE=“radio”> so that multiple bombs can be placed per location.

Even though the boards are 3x3, only five locations are allowed for user input corresponding to each qubit in the quantum program.

Each ship location will display a qubit number and a colorized damage percentage returned by the backend.

The game mechanics are exactly the same as the text-based version. Each player places three ships in the board, and then each takes a turn placing a bomb and clicks Submit. The Python CGI script will receive the request via AJAX, run the quantum program created in exercise 1, and return a damage result to be rendered in Javascript.

Note that all game state, arrays, variables, and other data, is kept in the client HTML; therefore we must use AJAX to send the request asynchronously, or else the data will be lost every time a player submits. There will be no page refreshes.

Quantum Battleship showing the bomb boards

Figure 6-3 shows the bottom 3x3 boards displaying a qubit number, a click count per bomb, and the image radio buttons rendered using CSS. Once each player places three ships and selects a location to bomb, the Submit button is clicked to send the AJAX request to the server. A Reset button is also available to restart the game at any point. Note that all state is kept in the client (browser). No data will be kept in the Python script as HTTP is a stateless request-response protocol. This means that when a request is received, the program is executed by the Web Server, a response is printed to the request output buffer, and the program terminates. As with the previous exercise, the solution is at the end of this section.

Exercise 3: Deploy and Troubleshoot in Apache HTTPD

Once all the pieces are in place, it’s time to deploy to the Web Server. I will use Apache HTTPD in CentOS 6, but this should work for any CentOS, Fedora, or Red Hat flavor (probably for any current Linux distribution with Apache HTTPD). Note that each flavor has its own idiosyncrasies when it comes to configuring system software. For example, CentOS focuses in stability and security which gave me a lot of headaches configuring HTTPD and Python.

Solution 1: A Reusable Python Program

Modularized Quantum Battleship Initialization

Listing 6-5 shows the first section of the script. Lines 6 and 7 import the Python libraries: cgi and cgitb (CGI Toolbox) used to read from the HTTP request and debug the CGI program, respectively.

Tip

The lines in the following paragraph activate a special exception handler that will display detailed reports in the web browser if any error occurs.

shipPos: A two-dimensional list that stores the positions for three ships per player initialized to -1; thus shipPos = [[-1, -1, -1], [-1, -1, -1]].

bomb: A two-dimensional list that stores bomb counts per position per player initialized to 0: bomb = [[0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0]]. Note that the same position can be bombed multiple times; therefore the need to store counts. This list will be used to calculate ship damage.

Reading Data from the HTTP Request

- To read data from the HTTP request, use form = cgi.FieldStorage(). This CGI call returns a dictionary or hash map of key-value pairs used to extract query string parameters from the request. In this particular case, the values expected are

ships1: A three-element JSON array of player 1 ship positions.

ships2: A three-element JSON array of player 2 ship positions.

bombs1: A five-element JSON array of bomb counts for player 1.

bombs2: A five-element JSON array of bomb counts for player 2.

- device: The device where the quantum program will be executed. This can be

local_qasm_simulator: Local simulator packed with the QISKit

ibmq_qasm_simulator: Remote simulator provided by IBM

ibmqx2: 5-qubit quantum processor provided by IBM Q Experience

The great thing about Python is that the JSON provided by the HTTP request can be mapped to its excellent collection support in a snap:

shipPos[0] = list(map(int, ships1.split(",")))bomb[0] = list(map(int, bombs1.split(",")))

Tip

In Python, the split(SEPARATOR) system call is used to create a list of elements of type String. But we need a list of integers instead. For that purpose we use the map(DATA-TYPE, LIST) system call. Note that in Python 3, map returns a hash map (dictionary); therefore we must use the list system call to convert to a list of integers we need. This is great because it allows the script to reuse the old data structures and keep most of the quantum logic intact.

Quantum Script Main Section

All print statements have been removed. Instead, a standard output string buffer is used to return information back to the client. This is done because Python’s print will dump information directly into the HTTP response which will mess up the JSON format we must return back (Javascript expects proper JSON from AJAX). Note that this is a purely optional but helpful step meant to return debug information back to the client. All in all, you can get away by simply commenting all print statements (of course, if an error occurs, you’ll have a hard time figuring out what went wrong).

All user input statements (read bomb position, Press enter to continue, and others) have been removed. Remember that ship positions and bomb counts are mapped from the HTTP request.

The original script uses an endless while loop to read bomb positions. This loop has been removed, or else the script will run forever and hang the HTTP request.

Sending the Response Back to the Browser

The preceding JSON document indicates damage for player 1 qubit(0) and player 2 qubit(1). This document will be parsed by the browser AJAX code and the values updated on screen.

Tip

The code for this exercise is available from the book source at Workspace\Ch06\battleship\cgi-bin\qbattleship.py.

Solution 2: User Interface

Quantum Battleship user interface

HTML Code for Figure 6-4

Dynamically Rendered Table Using document.write()

Cloud Battleship User Interface Tips and Tricks

We hide the checkboxes and radio buttons using stylesheets. The selectors in lines 1 and 2 use the negation pseudo-class to hide the rule from older browsers. Lines 3 to 5 set the width, margin, and padding, in order to be able to position the alternative graphics accurately. Line 6 sets the opacity to render the standard user interface invisible. | input[type=checkbox]:not(old), input[type=radio ]:not(old){ width : 104px; margin : 0; padding : 0; opacity : 0; } |

Each cell in the ships table displays •A qubit number •HTML span element to show damage percentage •An <INPUT type=”checkbox”> modified to use a 100x100 pixel image instead of the usual control | input[type=checkbox]:not(old) + label { display : inline-block; margin-left : -104px; padding-left : 104px; background : url('img/ship.png') no-repeat 0 0; line-height : 100px; } We position the label and display the unchecked image. Line 2 sets the label to display as an inline-block element, allowing line 6 to set its height to the height of the alternative graphics and center the text vertically. Line 3 uses a negative margin to cover the space where the standard user interface would be displayed, and line 4 then uses padding to restore the label text to the correct position. The 104-pixel value used here is equal to the width of the image plus some additional padding so that the label text is not too close to the image. Line 5 displays the unchecked image in the space before the label text. |

Each bomb cell contains •A qubit number •HTML span element to show bomb counts for that position •An <INPUT type=”radio”> modified with CSS to use a 100x100 pixel image instead of the usual control

| The style used to format the bomb is shown in the following fragment: input[type=radio ]:not(old) + label{ display : inline-block; margin-left : -104px; padding-left : 104x; background : url('img/bomb.png') no-repeat 0 0; line-height : 100px; } Next, we display the selected images when the checkboxes and radio buttons are selected: input[type=checkbox]:not(old):checked + label{ background-position : 0 -100px; } input[type=radio]:not(old):checked + label{ background-position : 0 -100px; } Because we have combined the images for the various states into a single image, the preceding rules modify the background position to show the appropriate image. |

The slick jQuery, Bootstrap, and Bootstrap-Growl libraries are used to render messages and debug information into the JS console: <script type="text/javascript" src="js/log.js"></script> <script type="text/javascript" src="js/jquery.js"></script> <script type="text/javascript" src="js/bootstrap.js"></script> <script type="text/javascript" src="js/bootstrap-growl.js"></script> <script type="text/javascript" src="js/notify.js"></script> | The HTML is beautified using the quintessential Bootstrap library for GUI design. Messages are displayed on screen using the great JS library Bootstrap-Growl: notify('Bomb ready. Click Submit', info);

|

Game Rules and Validation

Players cannot be allowed to place more than three ships on the board.

No ship changes must be allowed after a bomb is placed.

Bombs cannot be placed before all players place their ships.

A global array of bomb counts is used to track user clicks: var BOMBS = [[0,0,0,0,0], [0,0,0,0,0]]. This array matches its Python counterpart: bomb = [[0]*5 for _ in range(2)].

Enforcing Game Rules Using Click Callbacks from Book Source index.html

Now the data can be sent to the backend for consumption.

End Point and Response Format

Each request must be sent to the Web Server asynchronously using AJAX. Furthermore a specific format must be used for the query string. Thus the request-response format is as follows:

The username is centos.

The code has been deployed into the user’s home folder: $HOME/centos/public_html/battleship.

Python 3 must be activated by using the wrapper script qiskit-driver.sh. This is required only if multiple versions of Python are present in the host (see “Running Multiple Versions of Python” section).

ships1: comma-separated list of three positions for player 1 ships

ships2: comma-separated list of three positions for player 2 ships

bombs1: comma-separated list of five bomb counts for player 1

bombs2: comma-separated list of five bomb counts for player 2

device: quantum device. For example, local_qasm_simulator, ibmq_qasm_simulator, or ibmqx2.

Submitting Data to the Backend from Book Source index.html

If something goes wrong, an error notification will be displayed on screen, else the expected response JSON will be sent to a handler for consumption. Let’s see how.

Response Handler

Response Handler from Book Source index.html

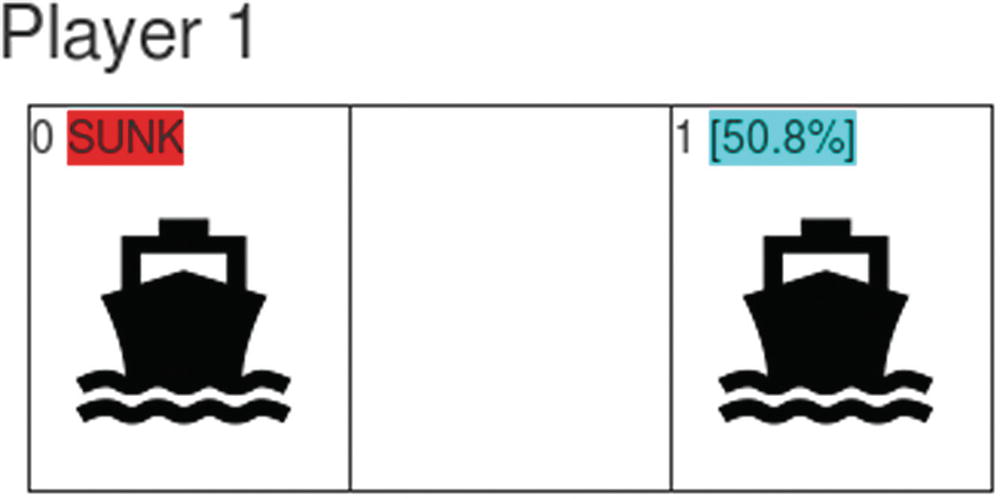

The handler extracts the damage array and loops for each position converting the damage for each player to a 1-100 percentage.

- Colorization is used to display the damage percentage for a dramatic effect. Messages are displayed on screen for each ship sunk (see Figure 6-5).

Figure 6-5

Figure 6-5Damage colorization

If the damage sum exceeds a 90% threshold for all ships of a player, a winner is declared and the game is over. Click the Reset button to start a new game.

Game Reset from Book Source index.html

Now it is time to run, deploy, test, and troubleshoot if necessary. I use CentOS 6 for development which bundles Python 2.7 as default. Remember that we must run in Python 3.5 or later.

Running Multiple Versions of Python

Now finally deploy and test. Hopefully troubleshooting won’t be necessary.

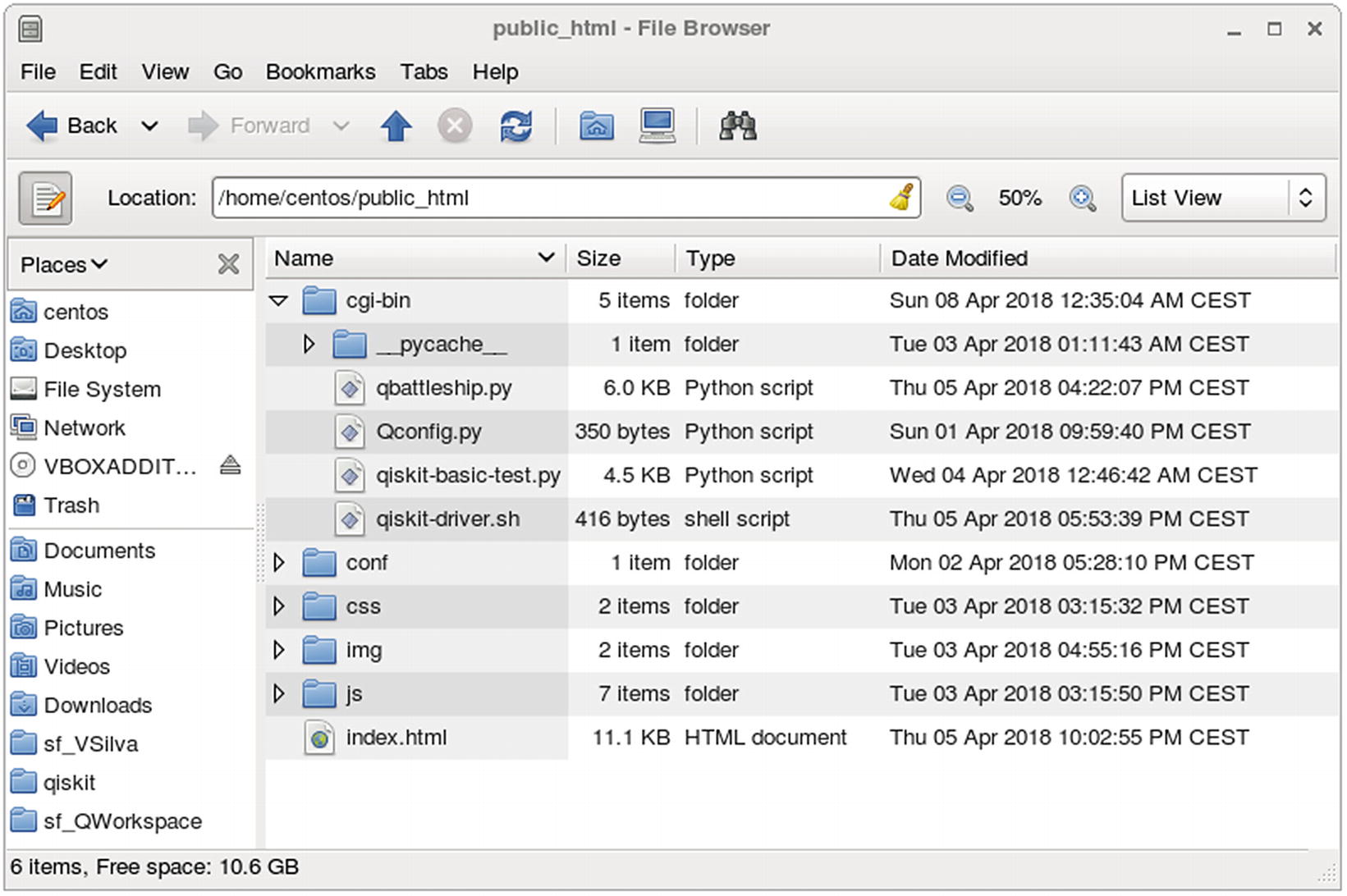

Solution 3: Deploy and Test

In this section we deploy the game in the Apache HTTPD server and look at the game in action. The full source for the game including all support files, styles, images, CGI wrapper, and quantum program, can be found in the book source under Workspace\Ch06\battleship. The folder layout is shown in Figure 6-6.

Note

This section assumes that you already have installed Apache HTTPD in your system and that the default service has been configured and it is running properly. If this is not the case, there are plenty of tutorials up there. For example, for CentOS 7 I like www.liquidweb.com/kb/how-to-install-apache-on-centos-7/ .

Folder layout for the Cloud Quantum Battleship

- 1.

Create a folder called public_html in your user’s home.

$ mkdir $HOME/public_html

- 2.

Create the cgi-bin folder under public_html to contain the CGI Python scripts.

$ mkdir $HOME/public_html/cgi-bin

- 3.

Configure the HTTPD server to enable access from the user’s public_html as well as public_html/cgi-bin folders (see Listing 6-15). Note that cgi-bin needs a special permission to allow for CGI script execution.

- 4.

If you wish to use the book source, copy all files from Workspace\Ch06\battleship to public_html/battleship.

- 5.

Make sure the file permissions are correct for the public_html folder and all subfolders and files. This is very important; if the permissions are incorrect, the browser will give a “500 – Internal Server Error” response. This was a major source of headaches when I was testing in my CentOS 6 desktop: $ chmod -R 755 public_html.

Configuration to Enable HTTP Requests from the User’s public_html Directory (CentOS 6/Apache HTTPD 2.2)

Tip

Enabling requests from public_html (Listing 6-15) requires the Apache module userdir to be enabled in httpd.conf (uncomment LoadModule userdir_module modules/mod_userdir.so). This module may not be enabled by default.

Finally, for the grand finale, start your browser and open the URL http://localhost/~centos/battleship/ (assuming the username is centos). Hopefully there will be no issues and you can start playing Quantum Battleship in the cloud; however if something goes wrong, here is a list of issues that I came across setting things up.

Troubleshooting

Apache HTTPD idiosyncrasies: Enabling requests from the user’s home (Listing 6-15) requires the module userdir to be enabled in the daemon configuration httpd.conf. Depending on your OS, this module may not be enabled by default. Also HTTPD 2.4 users: Listing 6-15 is for Apache v2.2; v2.4 may require a different syntax.

HTTP status 500 - Internal Server Error in the Browser: Make sure the file permissions for public_html and all files and subfolders are set to 755. You can diagnose this by looking at the HTTPD log files located at

/var/log/httpd/error_log/var/log/httpd/suexec.log

Tip

Apache suEXEC is a feature of the Apache Web Server. It allows users to run CGI and SSI applications as a different user. In CentOS suEXEC writes a log to /var/log/httpd/suexec.log.

SELinux headaches: This is a Linux kernel security module that provides a mechanism for supporting access control security policies. In CentOS this feature is enabled by default. It can be disabled temporarily from the command line using the command:

$ sudo setenforce 0

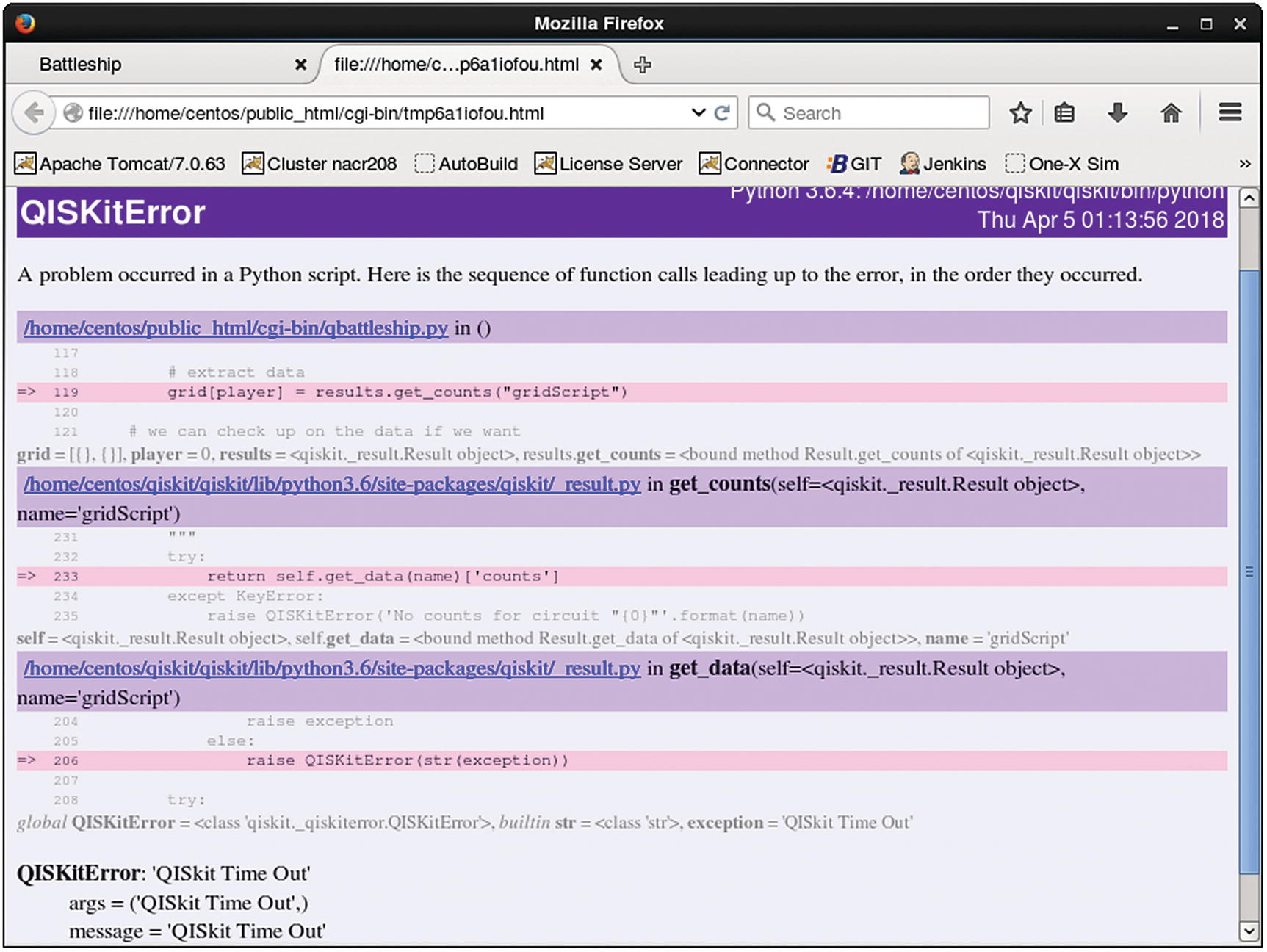

- Python bugs: If any error occurs in the Python script, the CGI exception handler will catch it and dump a nice HTML page in the current working directory (cgi-bin). Figure 6-7 shows the output from a timeout error occurred when executing in the real quantum device ibmqx2.

Figure 6-7

Figure 6-7Python error dump created by the cgi package

API configuration issues: Finally if running in a real quantum device, make sure the configuration is correct in Qconfig.py (including the API token for your Q Experience account) as shown in the next fragment:

Note that Qconfig.py must live in the same location as the quantum program qbattleship.py, that is, the cgi-bin folder. Still, further improvements can be made to the game; let’s discuss them in the next section.

Further Improvements

The user interface shows the ship and bomb boards for both players. In a real battleship game each player should open its own browser window, set his ships, and start bombing the opponent.

Gate state : ship, bomb positions, and quantum device are all kept in the client due to the fact that HTTP is a stateless protocol. That is, a request comes, the python program runs, and a response is sent back. After that, all memory disappears. A real game should use a server-based player lobby to host all the game state (e.g., using an application server) and coordinate communication between browser windows.

A Better Cloud Battleship

Improved Cloud Quantum Battleship

A rudimentary game lobby can be implemented as a Tomcat web application to store ship, bomb positions, and quantum device.

The web application can use the host OS runtime facilities (in this case Java’s runtime API) to invoke the quantum Python script, get damage results back, and dispatch them to each player.

To avoid the always-annoying browser page refreshes, each browser can connect via WebSocket to the application server. This will keep a permanent connection open where JSON text messages can be sent quickly between clients.

Connecting via WebSocket

The UI web page needs to be modified slightly to connect via WebSocket instead of AJAX as shown in Listing 6-16.

Tip

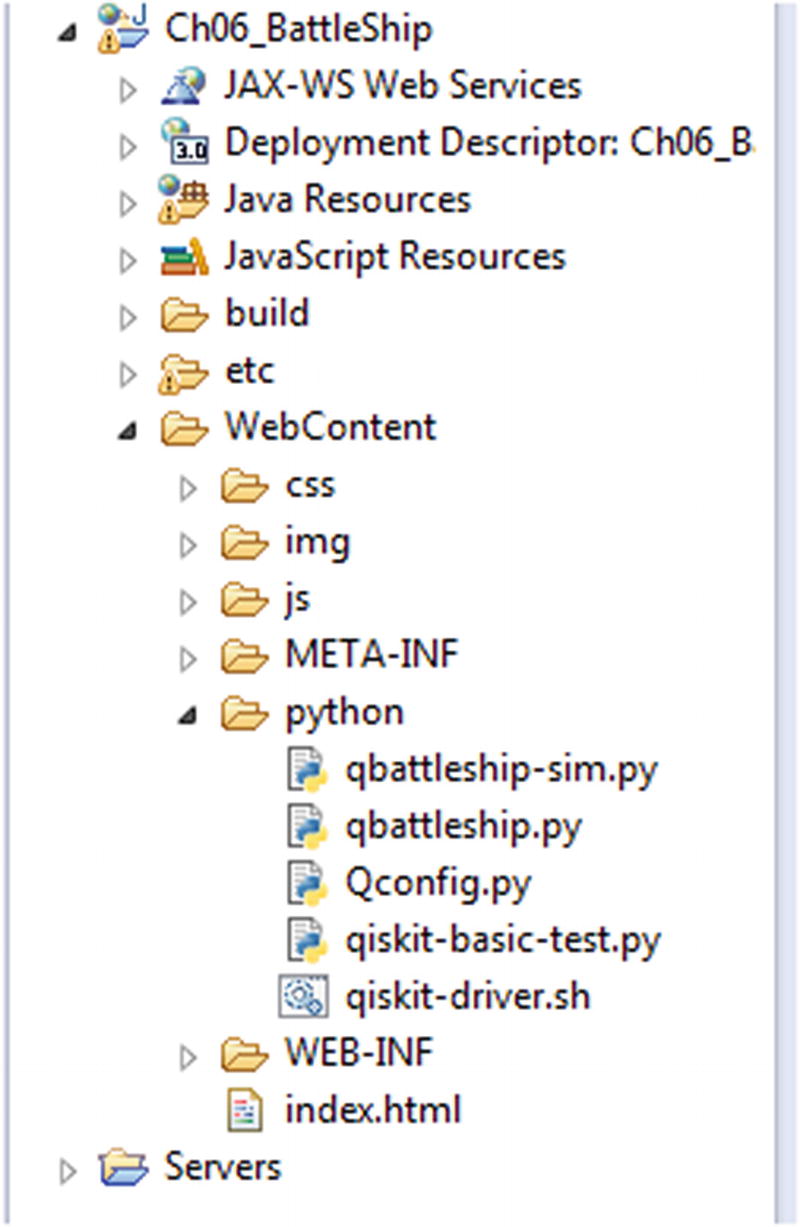

An Eclipse project for this section is provided in the book source under Workspace\Ch06_BattleShip. Given all the complex parts of this web app, I recommend that you open the workspace in your IDE and read along. Note that I assume that you have a good level of proficiency on writing apps with the Eclipse/Tomcat combo.

WebSocket Javascript Client Code Under WebContent/js/websocket.js

All major browsers implement the WebSocket standard used to keep a persistent connection against a capable server. For this, an end point URL of the form ws://localhost:8080/BattleShip/WSBattleship is created in line 2. Note that parameters can be sent in WebSocket end points just like regular URLs. Thus the final WS URL is ws://localhost:8080/BattleShip/WSBattleship?clientId=RANDOM-ID where a random ID is used to track each player.

- WebSocket in Javascript uses a callback system to receive events such as

socket.onopen: It fires when the socket is opened. Line 23 shows the callback used to handle this event.

socket.onclose: It fires when the connection is broken: when the browser is closed or refreshed or the server dies for example.

socket.onmessage: This is the most important callback. It fires when a message is received, and it is used to consume the JSON message sent by Python, just as AJAX does in the previous version.

WebSocket Server Handler Skeleton (WSConnector.java)

In Listing 6-17 line 1, the Java class WSConnector defines the annotation @ServerEndpoint(value = "/WSBattleship"). This powerful instruction is all we need to build a server handler. The value WSBattleship is the name of the handler; thus the full server end point will be ws://host:POT/Battleship/WSvattleship?QUERY-STRING.

- Callbacks for open, close, and message events are declared using the annotations: @OnOpen, @OnClose, and @OnMessage, respectively. Note that the method names are irrelevant, what matters are the parameters:

OnOpen: Receives a Session object which contains information about the connection.

OnClose: No parameters in this one. It fires when the browser connection dies.

OnMessage: The most important of the lot. It fires when a text message is sent by a client with the data as the argument.

Keep in mind that a single instance of the WSConnector class will be created for each client connection; thus in line 5, we use a thread safe static list List<WSConnectionDescriptor> connections to track all client connections. Line 8 declares a static hash map to track game data with the key being a player id and the value, a JSON object sent by the browser. For example, [Player-1 => {name: 'Player-1', ships: "0,0,0:, bombs: "0,0,0,0,0”, device: "local_qasm_simulator"}].

When the message callback fires (file WSConnector.java lines 201-253), the text message is parsed as JSON, the data is stored in memory, game rules applied, and if everything is correct, the Python script is invoked with ship and bomb positions. Finally the results are collected and sent back to each client for update.

Invoking Python and Setting File Permissions from Java

Executing OS Commands and Extracting Results (SysRunner.java)

Project layout of the Cloud Battleship J2EE project

Executing the Quantum Program and Sending Results Back

Obtains the LOCATION of the python folder within the web app. That is TOMCAT-ROOT/webapps/Battleship/python

- Executes the driver script LOCATION/qiskit-driver.sh LOCATION/qbattleship.py with the arguments:

ships1: Ship locations for player 1

ships2: Ship locations for player 2

bombs1: Bomb counts for player 1

bombs2: Bomb counts for player 2

device: Quantum device

Dispatches the results back to the clients

- 1.

Export the web app as a web archive WAR, and right-click the Ch06_Battleship project in your IDE (see Figure 6-9). Click Export > Web Archive, and select a name/destination (e.g., Ch06_Battleship.war).

- 2.Make sure the Tomcat service is up and running. If not installed by default in your system, here is some help:yum -y install java (CentOS 6,7)yum -y install tomcat7 tomcat7-webapps tomcat7-admin-webapps (CentOS 6,7)service tomcat7 start (CentOS 6)systemctl start tomcat7 (CentOS 7)

- 3.

Use the Tomcat manager UI at http://yourhost:8080/manager/ to upload and deploy the archive into your Linux Tomcat container. (Tip: The manager will ask for a user/password; if you don’t have them, edit the file /etc/tomcat7/tomcat-users.xml).

- 4.

You should now be able to point two browsers to http://localhost:8080/BattleShip/ (Tip: Tomcat web apps are deployed into the folder /var/lib/tomcat7/webapps). Having trouble? Check the container logs at /var/log/tomcat7/catalina.out.

Improved Cloud Battleship with two browsers

This chapter has shown how the popular game Battleship can be run in a quantum computer using a single-qubit partial NOT gate to compute ship damage. For this purpose, the Quantum Battleship sample from the QISKit tutorial has been used. Furthermore, the game has been taken to the next level by giving it a major face lift. You have learned how this quantum code can be invoked in the cloud using CGI scripting via the Apache HTTPD server. Further improvements have been made to play using two browsers via the Tomcat J2EE container. The code for both projects is available as Eclipse projects from the book source at Workspace\Ch06 and Workspace\Ch06_BattleShip, respectively.

The next chapter explores two game puzzles that show the remarkable power of quantum algorithms over their classical counterparts: the counterfeit coin puzzle and the Mermin-Peres Magic Square. These are examples of quantum pseudo-telepathy or the ability of players to achieve outcomes only possible if they were reading each other’s minds during the game.