The previous chapter introduced the fundamentals of x86-64 assembly language programming. You learned how to use the x86-64 instruction set to perform integer addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. You also examined source code that illustrated use of logical instructions, shift operations, memory addressing modes, and conditional jumps and moves. In addition to learning about frequently used instructions, your initiation to x86-64 assembly language programming has also covered important practical details including assembler directives and calling convention requirements.

In this chapter, your exploration of x86-64 assembly language programming fundamentals continues. You’ll learn how to use additional x86-64 instructions and assembler directives. You’ll also study source code that elucidates how to manipulate common programming constructs including arrays and data structures. This chapter concludes with several examples that demonstrate use of the x86’s string instructions.

Arrays

Arrays are an indispensable data construct in virtually all programming languages. In C++ there is an inherent connection between arrays and pointers since the name of an array is essentially a pointer to its first element. Moreover, whenever an array is used as a C++ function parameter, a pointer is passed instead of duplicating the array on the stack. Pointers are also employed for arrays that are dynamically allocated at runtime. This section examines x86-64 assembly language code that processes arrays. The first two sample programs demonstrate how to perform simple operations using one-dimensional arrays. This is followed by two examples that explain the techniques necessary to access the elements of a two-dimensional array.

One-Dimensional Arrays

In C++ one-dimensional arrays are stored in a contiguous block of memory that can be statically allocated at compile time or dynamically during program execution. The elements of a C++ array are accessed using zero-based indexing, which means that valid indices for an array of size N range from 0 to N-1. The sample code of this section includes examples that carry out basic operations with one-dimensional arrays using the x86-64 instruction set.

Accessing Elements

Example Ch03_01

Using Elements in Calculations

Example Ch03_02

The x86-64 assembly language function CalcArrayValues_ computes y[i] = x[i] * a + b. If you examine the declaration for this function in the C++ code, you will notice that the source array x is declared as an int while the destination array y is declared as long long. The other function arguments a, b, and n are declared as int, short, and int respectively. The remainder of the C++ code includes the function CalcArrayValuesCpp that also computes the specified array transformation for comparison purposes. It also includes code to display the results.

You may have noticed that in all of the sample source code presented thus far, only a subset of the general-purpose registers have been used. The reason for this is that the Visual C++ calling convention designates each general-purpose register as either volatile or non-volatile. Functions are permitted to use and alter the contents of any volatile register but cannot use a non-volatile register unless it preserves the caller’s original value. The Visual C++ calling convention designates registers RAX, RCX, RDX, R8, R9, R10, and R11 as volatile and the remaining general-purpose registers as non-volatile.

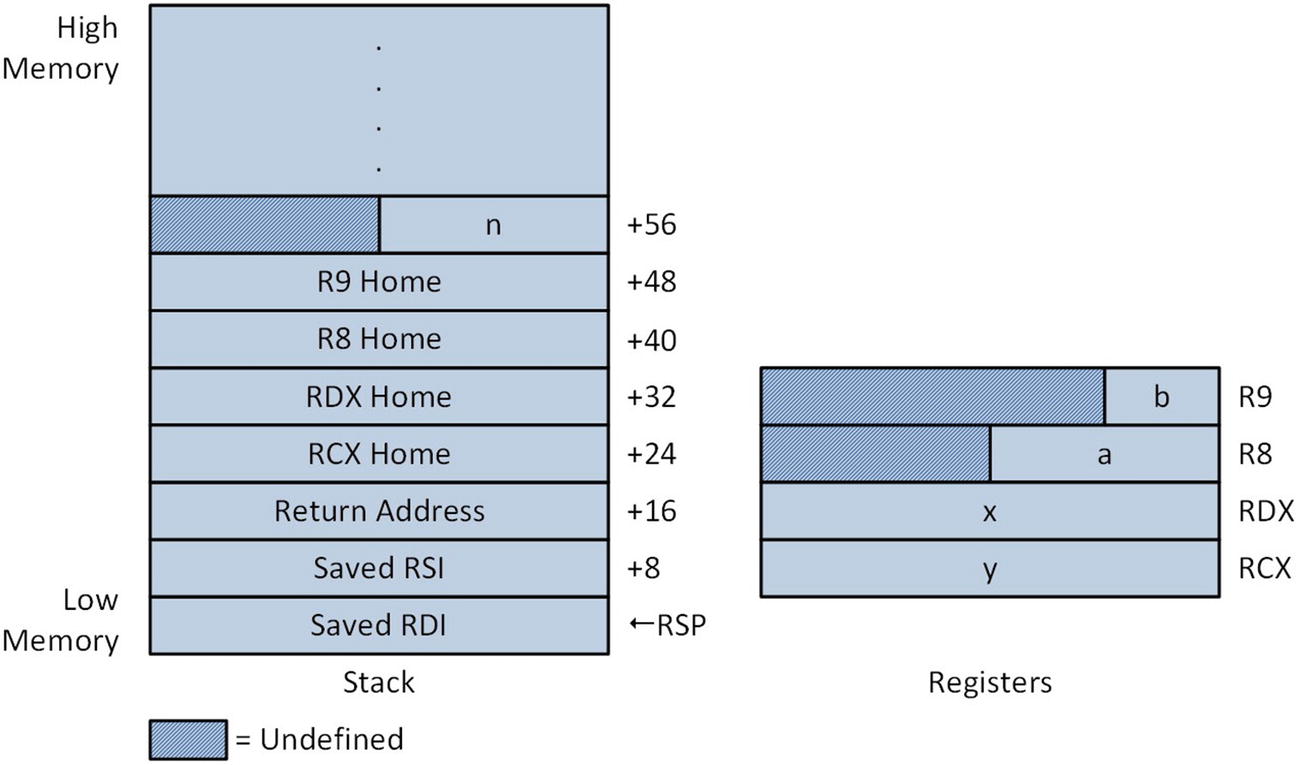

The function CalcArrayValues_ uses non-volatile registers RSI and RDI, which means that their values must be preserved. A function typically saves the values of any non-volatile registers it uses on the stack in a section of code called the prolog. A function epilog contains code that restores the values of any saved non-volatile registers. Function prologs and epilogs are also used to perform other calling-convention initialization tasks and you’ll learn about these in Chapter 5.

In the assembly language code for Ch03_02, the statement CalcArrayValues_ proc frame denotes the start of function CalcArrayValues_. Note the frame attribute on the proc directive. This attribute indicates that CalcArrayValues_ uses a formal function prolog. It also enables additional directives that must be used whenever a general-purpose register is saved on the stack or whenever a function employs a stack frame pointer. Chapter 5 discusses the frame attribute and stack frame pointers in greater detail.

The first x86-64 assembly language instruction of CalcArrayValues_ is push rsi (Push Value onto Stack), which saves the current value in register RSI on the stack. Immediately following this is a .pushreg rsi directive. This directive instructs the assembler to save information about push rsi instruction in an assembler-maintained table that is used to unwind the stack during exception processing. Using exceptions with assembly language code is not discussed in this book but the calling convention requirements for saving registers on the stack must still be observed. Register RDI is then saved on the stack using a push rdi instruction. The required .pushreg rdi directive follows next and the subsequent .endprolog directive signifies the end of the prolog for CalcArrayValues_.

Stack and register contents after prolog in CalcArrayValues_

The processing loop of CalcArrayValues_ uses a movsxd rcx,dword ptr [rsi+rdx*4] instruction to load a sign-extended copy of x[i] into register RCX. The ensuing imul rcx,r8 and add rcx,r9 instructions calculate x[i] * a + b and the mov qword ptr [rdi+rdx*8] instruction saves the final result to y[i]. Note that in the processing loop, the two move instructions use different scale factors. This is because array x and array y are declared as int and long long. The add rax,rcx instruction updates a running sum that will be used as the return value. The inc edx (Increment by 1) instruction adds 1 to the value that’s in register EDX. It also zeros bits 63:32 of register RDX. The reason for using an inc edx instruction instead of an inc rdx instruction is that the machine language encoding of the former requires less code space. More importantly, it is okay to use an inc edx instruction here since the maximum number of elements to be processed is specified by a 32-bit signed integer (n) that’s already been validated as being greater than zero. The following cmp edx,r11d instruction compares the contents of EDX (which is i) to n, and the processing loop repeats until i equals n.

Two-Dimensional Arrays

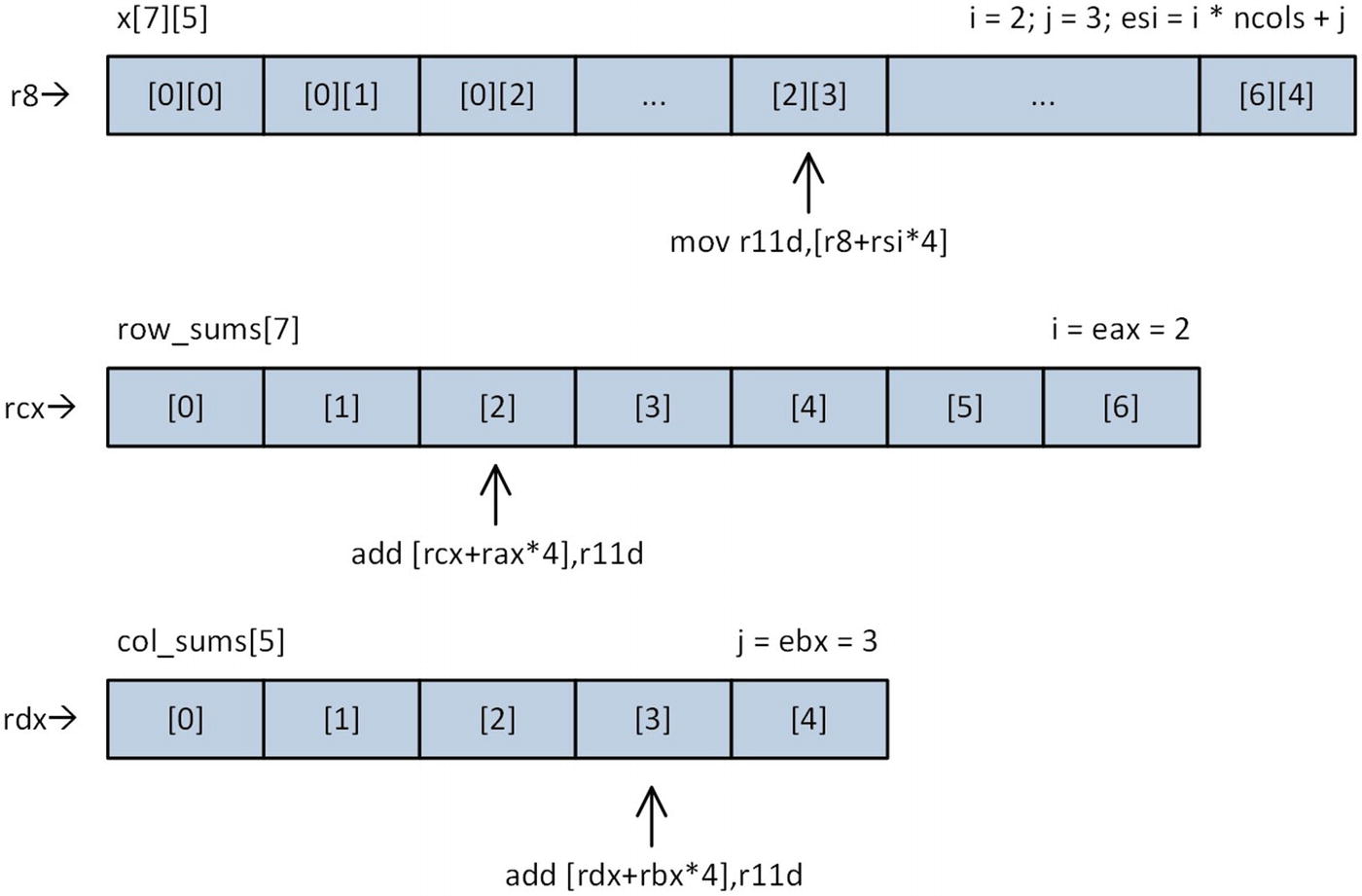

C++ also utilizes a contiguous block of memory to implement a two-dimensional array or matrix. The elements of a C++ matrix in memory are organized using row-major ordering. Row-major ordering arranges the elements of a matrix first by row and then by column. For example, elements of the matrix int x[3][2] are stored in memory as follows: x[0][0], x[0][1], x[1][0], x[1][1], x[2][0], and x[2][1]. In order to access a specific element in the matrix, a function (or a compiler) must know the starting address of the matrix (i.e., the address of its first element), the row and column indices, the total number of columns, and the size in bytes of each element. Using this information, a function can use simple arithmetic to access a specific element in a matrix as exemplified by the sample code in this section.

Accessing Elements

Example Ch03_03

The C++ function CalcMatrixSquaresCpp illustrates how to access the elements of a matrix. The first thing to note is that arguments x and y point to the memory blocks that contain their respective matrices. Inside the second for loop, the expression kx = j * ncols + i calculates the offset necessary to access element x[j][i]. Similarly, the expression ky = i * ncols + j calculates the offset for element y[i][j].

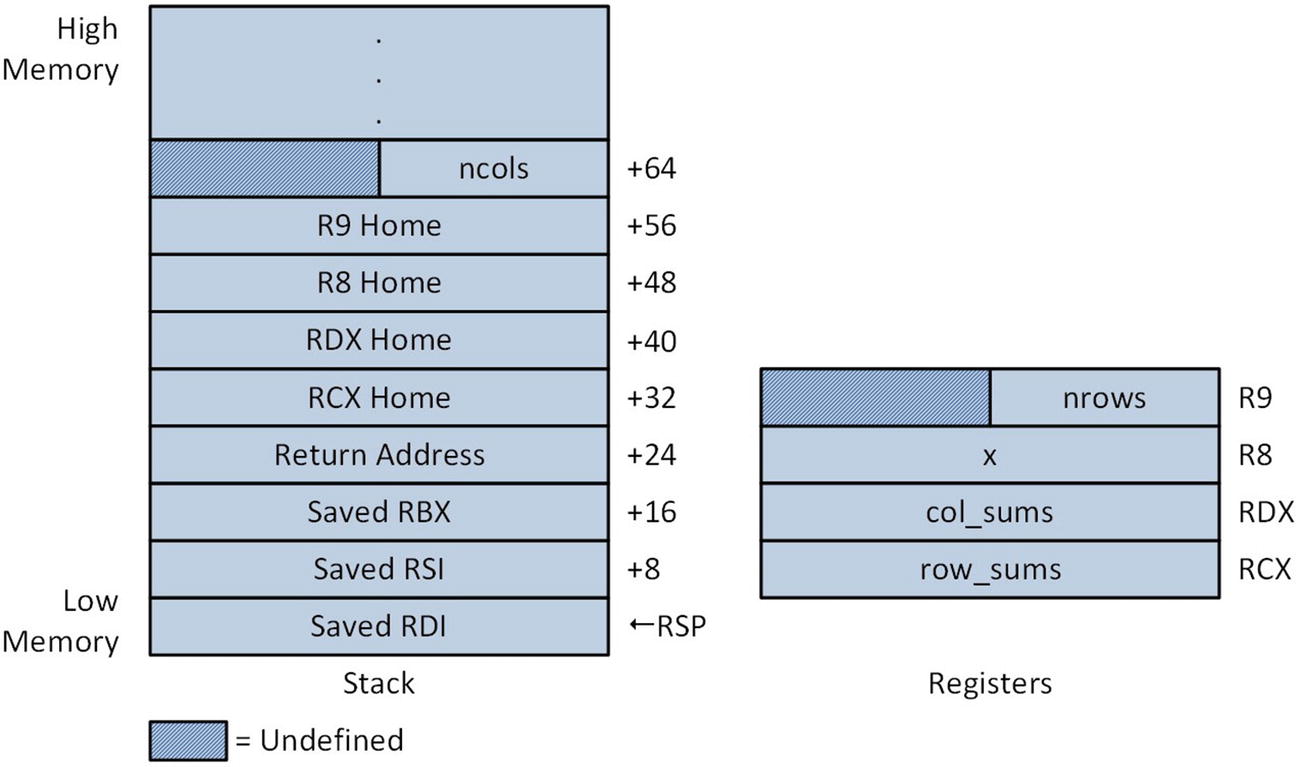

The assembly language function CalcMatrixSquares_ implements the same calculations as the C++ code to access elements in matrices x and y. This function begins with a prolog that saves non-volatile registers RSI and RDI using the same instructions and directives as the previous source code example. Next, argument values nrows and ncols are checked to ensure that they’re greater than zero. Prior to the start of the nested processing loops, registers RSI and RDI are initialized as pointers to x and y. Registers RCX and RDX are also primed as the loop index variables and perform the same functions as variables i and j in the C++ code. This is followed by two movsxd instructions that load sign-extended copies of nrows and ncols into registers R8 and R9.

Row-Column Calculations

Example Ch03_04

Stack and register contents after prolog in CalcMatrixRowColSums_

Memory addressing used in function CalcMatrixRowColSums_

Structures

A structure is a programming language construct that facilitates the definition of new data types using one or more existing data types. In this section, you’ll learn how to define and use a common structure in both a C++ and x86-64 assembly language function. You’ll also learn how to deal with potential semantic issues that can arise when working with a common structure that’s manipulated by software functions written using different programming languages.

In C++ a structure is equivalent to a class. When a data type is defined using the keyword struct instead of class, all members are public by default. A C++ struct that’s declared sans any member functions or operators is equivalent to a C-style structure such as typedef struct { ... } MyStruct;. C++ structure declarations are usually placed in a header (.h) file so they can be easily referenced by multiple C++ files. The same technique also can be employed to declare and reference structures that are used in assembly language code. Unfortunately, it is not possible to declare a single structure in a header file and include this file in both C++ and assembly-language source code files. If you want to use the “same” structure in both C++ and assembly language code, it must be declared twice and both declarations must be semantically equivalent.

Example Ch03_05

The C++ function CalcTestStructSumCpp sums the members of the TestStruct instance that’s passed to it. The x86 assembly language function CalcTestStructSum_ performs the same operation. The movsx eax,byte ptr [rcx+TestStruct.Val8] and movsx edx,word ptr [rcx+TestStruct.Val16] instructions load sign-extended copies of structure members TestStruct.Val8 and TestStruct.Val16 into registers EAX and EDX, respectively. These instructions also illustrate the syntax that is required to reference a structure member in an assembly language instruction. From the perspective of the assembler, the movsx instructions are instances of BaseReg+Disp memory addressing since the assembler ultimately converts structure members TestStruct.Val8 and TestStruct.Val16 into constant displacement values.

Strings

The x86-64 instruction set includes several useful instructions that process and manipulate strings. In x86 parlance, a string is a contiguous sequence of bytes, words, doublewords, or quadwords. Programs can use the x86 string instructions to process conventional text strings such as “Hello, World.” They also can be employed to perform operations using the elements of an array or similarly-ordered data in memory. In this section, you’ll examine some sample code that demonstrates how to use the x86-64 string instructions with text strings and integer arrays.

Counting Characters

Example Ch03_06

The assembly language function CountChars_ accepts two arguments: a text string pointer s and a search character c. Both arguments are of type char, which means that each text string character and the search character require one byte of storage. The function CountChars_ starts with a function prolog that saves the caller’s RSI on the stack. It then loads the text string pointer s into RSI and the search character c into register CL. An xor edx,edx instruction initializes register RDX to zero for use as a character occurrence counter. The processing loop uses the lodsb instruction to read each text string character. This instruction loads register AL with the contents of the memory pointed to by RSI; it then increments RSI by one so that it points to the next character.

A version of CountChars_ that processes strings of type wchar_t instead of char can be easily created by changing the lodsb instruction to a lodsw (Load String Word) instruction. 16-bit registers would also need to be used instead of 8-bit registers for the character matching instructions. The last character of an x86 string instruction mnemonic indicates the size of the operand that is processed.

String Concatenation

Example Ch03_07

Let’s begin by examining the C++ code in Listing 3-7. It starts with a declaration statement for the assembly language function ConcatStrings_, which includes four parameters: des is the destination buffer for the final string; des_size is the size of des in characters; and parameter src points to an array that contains pointers to src_n text strings. In 64-bit Visual C++ programs, the type size_t is equivalent to a 64-bit unsigned integer. The function ConcatStrings_ returns the length of des or -1 if the supplied value for des_size is less than or equal to zero.

The test cases presented in main illustrate use of ConcatStrings_. If, for example, src points to a text string array consisting of “Red” , “Green” , “Blue” , the final string in des is "RedGreenBlue" provided des is large enough to contain the result. If des_size is insufficient, ConcatStrings_ produces a partially concatenated string. For example, a des_size equal to 10 would yield "RedGreen" as the final string.

Following its prolog, the function ConcatStrings_ checks argument value des_size for validity using a test rdx,rdx instruction. This instruction performs a bitwise AND of its two operands and sets the parity (RFLAGS.PF), sign (RFLAGS.SF), and zero (RFLAGS.ZF) flags based on the result (the carry (RFLAGS.CF) and overflow (RFLAGS.OF) are set to zero). The result of the bitwise AND operation is not saved. The test instruction is often used as an alternative to the cmp instruction, especially when a function needs to ascertain if a value is less than, equal to, or greater than zero. Using a test instruction may also be more efficient in terms of code space. In this instance, the test rdx,rdx instruction requires fewer opcode bytes than a cmp rdx,0 instruction. Register initialization is carried out next prior to the start of the concatenation processing loop.

The subsequent block of instructions marks the top of the concatenation loop that begins by loading registers RSI and RDI with a pointer to string src[i]. The length of src[i] is determined next using a repne scasb instruction in conjunction with several support instructions. The repne (Repeat String Operation While not Equal) is an instruction prefix that repeats execution of a string instruction while the condition RCX != 0 && RFLAGS.ZF == 0 is true. The exact operation of the repne scasb (Scan String Byte) combination is as follows: If RCX is not zero, the scasb instruction compares the string character pointed to by RDI to the contents of register AL and sets the status flags according to the results. Register RDI is then automatically incremented by one so that it points to the next character and a count of one is subtracted from RCX. This string-processing operation is repeated as long as the aforementioned test conditions remain true; otherwise, the repeat string operation terminates.

Prior to use of the repne scasb instruction, register RCX was loaded with -1. Upon completion of repne scasb, register RCX contains -(L + 2), where L denotes the actual length of string src[i]. The value L is calculated using a not rcx (One’s Complement Negation) instruction followed by a dec rcx (Decrement by 1) instruction, which is equal to subtracting 2 from the two’s complement negation of -(L + 2). It should be noted that the instruction sequence used here to calculate the length of a text string is a well-known technique that dates back to the 8086 CPU.

Following the computation of len(src[i]), a check is made to verify that the string src[i] will fit into the destination buffer. If the sum des_index + len(src[i]) is greater than or equal to des_size, the function terminates. Otherwise, len(src[i]) is added to des_index and string src[i] is copied to the correct position in des using a rep movsb (Repeat Move String Byte) instruction.

Comparing Arrays

Example Ch03_08

The assembly language function CompareArrays_ compares the elements of two integer arrays and returns the index of the first non-matching element. If the arrays are identical, the number of elements is returned. Otherwise, -1 is returned to indicate an error. Following the function prolog, a test r8,r8 instruction checks argument value n to see if it’s less than or equal to zero. As you learned in the previous section, this instruction performs a bitwise AND of the two operands and sets the status flags RFLAGS.PF, RFLAGS.SF, and RFLAGS.ZF based on the result (RFLAGS.CF and RFLAGS.OF are cleared). The result of the AND operation is discarded. If argument value n is invalid, the jle @F instruction skips over the compare code.

Array Reversal

Example Ch03_09

The function ReverseArray_ copies the elements of a source array to a destination array in reverse order. This function requires three parameters: a pointer to a destination array named y, a pointer to a source array named x, and the number of elements n. Following validation of n, registers RSI and RDI are initialized with pointers to the arrays x and y. A mov ecx,r8d instruction loads the number of elements into register RCX. In order to reverse the elements of the source array, the address of the last array element x[n - 1] needs to be calculated. This is accomplished using a lea rsi,[rsi+rcx*4-4] instruction, which computes the effective address of the source memory operand (i.e., it performs the arithmetic operation specified between the brackets and saves the result to register RSI).

The Visual C++ runtime environment assumes that the direction flag (RFLAGS.DF) is always cleared. If an assembly language function sets RFLAGS.DF to perform auto-decrementing with a string instruction, the flag must be cleared before returning to the caller or using any library functions. The function ReverseArray_ partially fulfills this requirement by saving the current state of RFLAGS.DF on the stack using the pushfq (Push RFLAGS Register onto Stack) instruction. It then uses the std (Set Direction Flag) instruction to set RFLAGS.DF to 1. The duplication of array elements from x to y is straightforward. A lodsd (Load String Doubleword) instruction loads an element from x into EAX and subtracts four from register RSI. The next instruction, mov [rdi],eax, saves this value to the element in y that is pointed to by RDI. An add rdi,4 instruction points EDI to the next element in y. Register RCX is then decremented and the loop is repeated until the array reversal is complete.

Summary

The address of an element in a one-dimensional array can be calculated using the base address (i.e., the address of the first element) of the array, the index of the element, and the size in bytes of each element. The address of an element in a two-dimensional array can be calculated using the base address of the array, the row and column indices, the number of columns, and the size in bytes of each element.

The Visual C++ calling convention designates each general-purpose register as volatile or non-volatile. A function must preserve the contents of any non-volatile general-purpose register it uses. A function should use the push instruction in its prolog to save the contents of a non-volatile register on the stack. A function should use the pop instruction in its epilog to restore the contents of any previously-saved non-volatile register.

X86-64 assembly language code can define and use structures similar to the way they are used in C++. An assembly language structure may require extra padding elements to ensure that it’s semantically equivalent to a C++ structure.

The upper 32 bits of a 64-bit general-purpose register are set to zero in instructions that specify the corresponding 32-bit register as a destination operand. The upper 56 or 48 bits of a 64-bit general-purpose register are not affected when the destination operand of an instruction is an 8-bit or 16-bit register.

The x86 string instructions cmps, lods, movs, scas, and stos can be used to compare, load, copy, scan, or initialize text strings. They also can be used to perform operations on arrays and other similarly-ordered data structures.

The prefixes rep, repe, repz, repne, and repnz can be used with a string instruction to repeat a string operation multiple times (RCX contains the count value) or until the specified zero flag (RFLAGS.ZF) condition occurs.

The state of the direction flag (RFLAGS.DF) must be preserved across function boundaries.

The test instruction is often used as an alternative to the cmp instruction, especially when testing a value to ascertain if it’s less than, equal to, or greater than zero.

The lea instruction can be used to simplify effective address calculations.