In the previous chapter, you learned about the fundamentals of the x86-64 platform including its data types, register sets, memory addressing modes, and the core instruction set. In this chapter, you learn how to code basic x86-64 assembly language functions that are callable from C++. You also learn about the semantics and syntax of an x86-64 assembly language source code file. The sample source code and accompanying remarks of this chapter are intended to complement the instructive material presented in Chapter 1.

The content of Chapter 2 is organized as follows. The first section describes how to code functions that perform simple integer arithmetic such as addition and subtraction. You also learn the basics of passing arguments and return values between functions written in C++ and x86-64 assembly language. The next section highlights additional arithmetic instructions including integer multiplication and division. In the final section, you learn how to reference operands in memory and use conditional jumps and conditional moves.

It should be noted that the primary purpose of the sample code presented in this chapter is to elucidate proper use of the x86-64 instruction set and basic assembly language programming techniques. All of the assembly language code is straightforward, but not necessarily optimal since understanding optimized assembly language code can be challenging especially for beginners. The sample code that's discussed in later chapters places more emphasis on efficient coding techniques. Chapter 15 also examines techniques that you can use to improve the efficiency of your assembly language code.

Simple Integer Arithmetic

In this section, you learn the basics of x86-64 assembly language programming. It begins with a simple program that demonstrates how to perform integer addition and subtraction. This is followed by an example program that illustrates use of the logical instructions and, or, and xor. The final program describes how to execute shift operations. All three programs illustrate passing argument and return values between a C++ and assembly language function. They also show how to employ commonly-used assembler directives.

As mentioned in the Introduction, all of the sample code discussed in this book was created using Microsoft's Visual C++ and Macro Assembler (MASM), which are included with Visual Studio. Before taking a look at the first code example, a few instructive comments about these development tools may be helpful. Visual Studio uses entities called solutions and projects to help simplify application development. A solution is a collection of one or more projects that are used to build an application. Projects are container objects that help organize an application’s files including (but not limited to) source code, resources, icons, bitmaps, HTML, and XML. A Visual Studio project is usually created for each buildable component (e.g., executable file, dynamic-linked library, static library, etc.) of an application. You can open and load a chapter’s sample programs into the Visual Studio development environment by double-clicking on its solution (.sln) file. Appendix A contain additional information regarding the use of Visual C++ and MASM.

Note

All of the source code examples in this book include one or more functions written in x86-64 assembly language plus some C++ code that demonstrates how to invoke the assembly language code. The C++ code also contains ancillary functions that perform required initializations and display results. For each source code example, a single listing that includes both the C++ and assembly language source code is used in order to minimize the number of listing references in the main text. The actual source code uses separate files for the C++ (.cpp) and assembly language (.asm) code.

Addition and Subtraction

Example Ch02_01

The C++ code in Listing 2-1 is mostly straightforward but includes a few lines that warrant some explanatory comments. The #include "stdafx.h" statement specifies a project-specific header file that contains references to frequently used system items. Visual Studio automatically generates this file whenever a new C++ project is created. The line extern "C" int IntegerAddSub_(int a, int b, int c, int d) is a declaration statement that defines the parameters and return value for the x86-64 assembly language function IntegerAddSub_ (all assembly language function names and public variables used in this book include a trailing underscore for easier recognition). The declaration statement’s "C" modifier instructs the C++ compiler to use C-style naming for function IntegerAddSub_ instead of a C++ decorated name (a C++ decorated name includes extra characters that help support function overloading). It also notifies the compiler to use C-style linkage for the specified function.

The C++ function main contains the code that calls the assembly language function IntegerAddSub_. This function requires four arguments of type int and returns a single int value. Like many programming languages, Visual C++ uses a combination of processor registers and the stack to pass argument values to a function. In the current example, the C++ compiler generates code that loads the values of a, b, c, and d into registers ECX, EDX, R8D, and R9D, respectively, prior to calling function IntegerAddSub_.

In Listing 2-1 the x86-64 assembly language code for example Ch02_01 is shown immediately after the C++ function main. The first thing to notice are the lines that begin with a semicolon. These are comments lines. MASM treats any text that follows a semicolon as comment text. The .code statement is a MASM directive that defines the start of an assembly language code section. A MASM directive is a statement that instructs the assembler how to perform certain actions. You’ll learn how to use additional directives throughout this book.

The IntegerAddSub_ proc statement defines the start of the assembly language function . Toward the end of Listing 2-1, the IntegerAddSub_ endp statement marks the end of the function. Like the .code line, the proc and endp statements are not executable instructions but assembler directives that signify the start and end of an assembly language function. The final end statement is a required assembler directive that indicates the completion of statements for the assembly language file. The assembler ignores any text that appears after the end directive.

The assembly language function IntegerAddSub_ calculates a + b + c - d and returns this value to the calling C++ function. It begins with a mov eax,ecx (Move) instruction that copies the value a from ECX into EAX. Note that the contents of ECX are not altered by the mov instruction. Following execution of this mov instruction, registers EAX and ECX both contain the value a. The add eax,edx instruction adds the values in registers EAX and EDX. It then saves the sum (or a + b) in register EAX. Like the previous mov instruction, the contents of register EDX are not modified by the add instruction. The next instruction, add eax,r8d computes a + b + c. This is followed by a sub eax,r9d instruction that calculates the final value a + b + c – d.

Logical Operations

Example Ch02_02

Similar to what you saw in the first example, the declaration of assembly language function IntegerLogical_ uses the "C" modifier to instruct the C++ compiler not to generate a decorated name for this function. Omitting this modifier would result in a link error during program build. (If the "C" modifier is omitted from the current example, Visual C++ 2017 uses the decorated function name ?IntegerLogical_@@YAIIIII@Z instead of IntegerLogical_. Decorated names are derived using the function's argument types, and these names are compiler specific.) Function IntegerLogical_ requires four unsigned int arguments and returns a single unsigned int result. Immediately following the declaration of function IntegerLogical_ is the definition of a global unsigned int variable named g_Val1. This variable is defined to demonstrate how to access a global value from an assembly language function. Like function declarations, use of the "C" modifier for g_Val1 instructs the compiler to use C-style naming instead of a decorated C++ name.

The definition of function IntegerLogicalCpp follows next in the C++ source code. The reason for defining this function is to provide a simple method for determining whether or not the corresponding x86-64 assembly language function IntegerLogical_ calculates the correct result. While overkill for this particular example, coding complex functions using both C++ and assembly language is often helpful for software test and debugging purposes. The function main in Listing 2-2 includes code that calls both IntegerLogicalCpp and IntegerLogical_. It also calls the function PrintResult to display the results.

In Listing 2-2 the x86-64 assembly language code for example Ch02_02 follows the C++ function main. The first assembly language source code statement, extern g_Val1: dword , is the MASM equivalent of the corresponding declaration for g_Val1 that’s used in the C++ code. In this instance, the extern directive notifies the assembler that storage space for the variable g_Val1 is defined in another module, and the dword directive indicates that g_Val1 is a doubleword (or 32-bit) unsigned value.

Shift Operations

Example Ch02_03

Near the top of the C++ code, the declaration of the x86 assembly language function IntegerShift_ is somewhat different than the previous examples in that it defines two pointer arguments. Pointers are used by this function since it needs to return more than one result to its calling function. The other minor difference is that the int return value from IntegerShift_ is used to indicate whether or not the value of count is valid. The remaining C++ code in Listing 2-3 exercises the assembly language function IntegerShift_ using a few test cases and displays results.

The assembly language code of function IntegerShift_ starts with an xor eax,eax instruction that sets register EAX to zero. This is done to ensure that register EAX contains the correct return code should an invalid value for argument count be detected. The next instruction, cmp edx,31, compares the contents of register EDX, which contains count, to the constant value 31. When the processor performs a compare operation, it subtracts the second operand from the first operand, sets the status flags based on the results of this operation, and discards the result. If the value of count is above 31, the ja InvalidCount instruction performs a jump to the program location specified by the destination operand. If you look ahead a few lines, you will notice a statement with the text InvalidCount:. This text is called a label. If count > 31 is true, the ja InvalidCount instruction transfers program control to the first assembly language instruction immediately following the label InvalidCount. Note that this instruction can be on same line or a different line, as shown in Listing 2-3.

The xchg ecx,edx instruction swaps the values in registers ECX and EDX. The reason for doing this is that the shl and shr instructions must use register CL for the shift count. The mov eax,edx copies the value a into register EAX, and the subsequent shl eax,cl instruction shifts this value left by the number of bits that’s specified in register CL. The 64-bit pointer value a_shr is passed to function IntegerShift_ using register R8 (in 64-bit programming, all pointers are 64 bits). The mov [r8],eax instruction saves the result of the shift operation to the memory location that’s specified by the contents of register R8.

Advanced Integer Arithmetic

In this section, you’ll learn how to perform integer multiplication and division. You’ll also learn how to use the x86-64 assembly language instruction set to carry out integer arithmetic using operands of different sizes. In addition to these topics, this section introduces important programming concepts and a few particulars related to Visual C++ calling convention.

Note

The Visual C++ calling convention requirements that are described in this section and in subsequent chapters may be different for other high-level programming languages and operating systems. If you're reading this book to learn x86-64 assembly language and plan on using it with a different high-level programming language or operating system, you should consult the appropriate documentation for more information regarding the target platform's calling convention requirements.

Multiplication and Division

Example Ch02_04

A calling convention is a binary protocol that describes how arguments and return values are exchanged between two functions. As you have already seen, the Visual C++ calling convention for x86-64 programs on Windows requires a calling function to pass the first four integer (or pointer) arguments using registers RCX, RDX, R8, and R9. The low-order portions of these registers are used for argument values smaller than 64 bits (e.g., ECX, CX, or CL for a 32-, 16-, or 8-bit integer). Any additional arguments are passed using the stack. The calling convention also defines additional requirements including rules for passing floating-point values, general-purpose and XMM register use, and stack frames. You’ll learn about these additional requirements in Chapter 5.

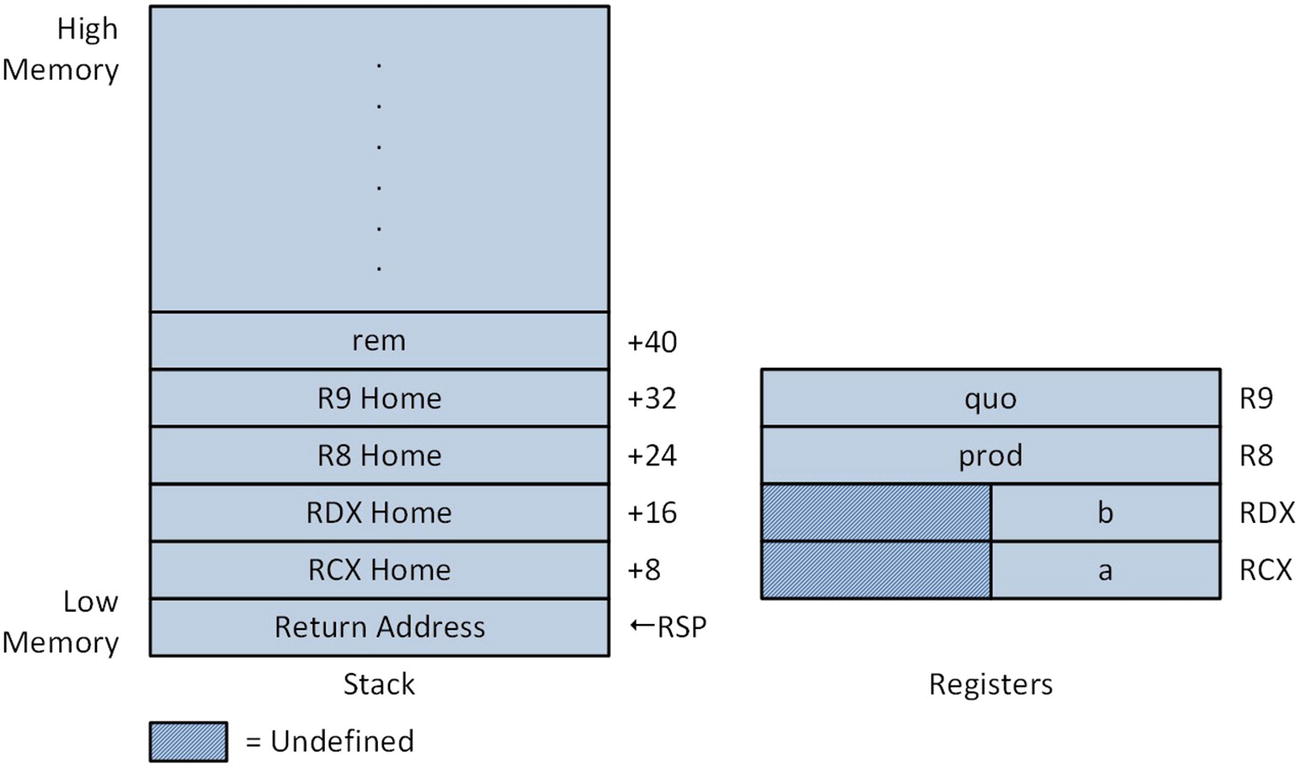

Argument registers and stack at entry to function IntegerMulDiv_

Figure 2-1 illustrates the state of the stack and the argument registers upon entry to IntegerMulDiv_ but prior to the execution of its first instruction. Note that the location of the fifth argument value rem is at memory address RSP + 40. As simple mov instruction can be used to load rem, which is a pointer, into a general-purpose register when it’s needed. Also note in Figure 2-1 that register RSP points to the caller’s return address on the stack. During execution of a ret instruction, the processor copies this value from the stack and ultimately stores it in register RIP. The ret instruction also removes the caller’s return address from the stack by adding 8 to the value in RSP. The stack locations labeled RCX Home, RDX Home, R8 Home, and R9 Home are storage areas that can be used to temporarily save the corresponding argument registers. These areas can also be used to store other transient data. You’ll learn more about the home area in Chapter 5.

The function IntegerMulDiv_ computes and saves the product a * b. It also calculates and saves the quotient and remainder of a / b. Since IntegerMulDiv_ performs division using b, it makes sense to test the value of b to confirm that it’s not equal to zero. In Listing 2-4, the mov eax,edx instruction copies b into register EAX. The next instruction, or eax,eax, performs a bitwise OR operation to set the status flags. If b is zero, the jz InvalidDivisor (Jump if Zero) instruction skips over the code that performs the division. Like the previous example, the function IntegerMulDiv_ uses a return value of zero to indicate an error condition. Since EAX already contains zero, no additional instructions are necessary.

The next instruction imul eax,ecx computes a * b and saves the product to the memory location specified by R8, which contains the pointer prod. The x86-64 instruction set supports several different forms of the imul instruction. The two-operand form that’s used here actually computes a 64-bit result (recall that the product of two 32-bit integers is always a 64-bit result) but saves only the lower 32 bits in the destination operand. The single-operand form of imul can be used when a non-truncated result is required.

Calculations Using Mixed Types

Example Ch02_05

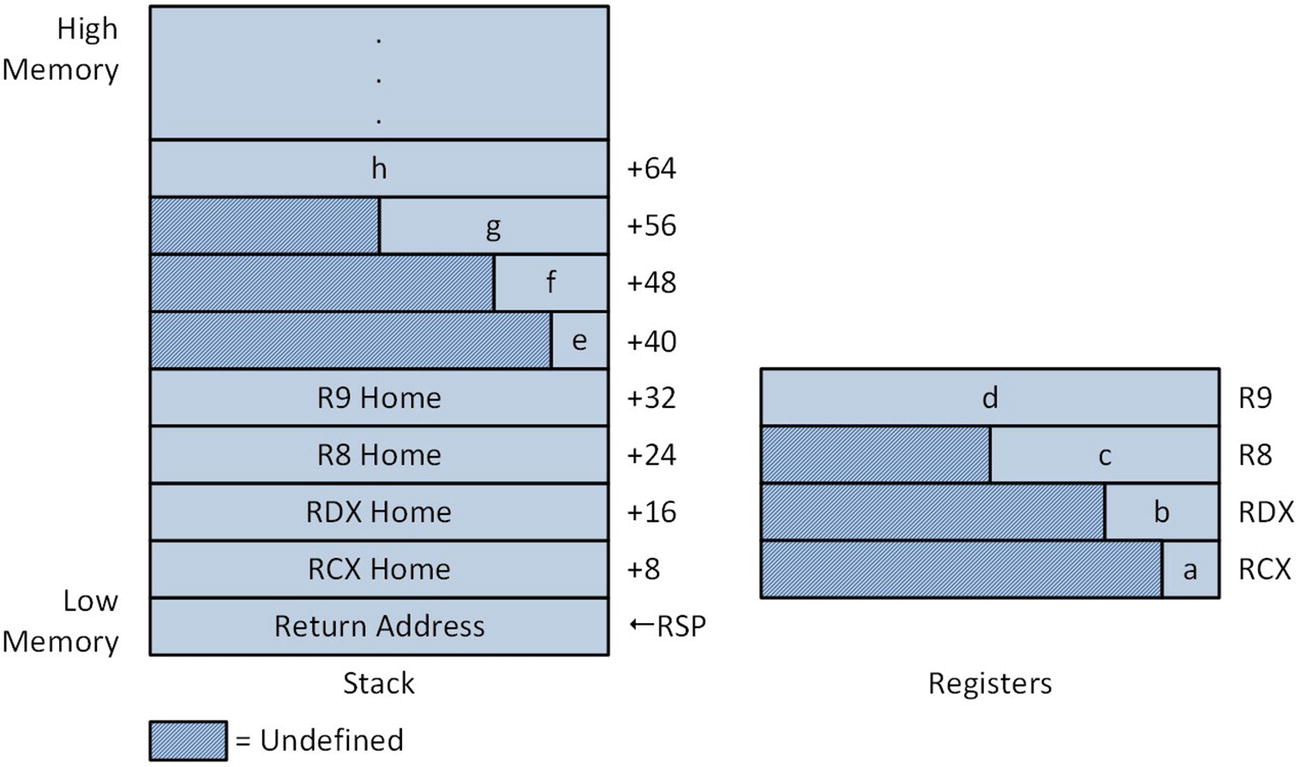

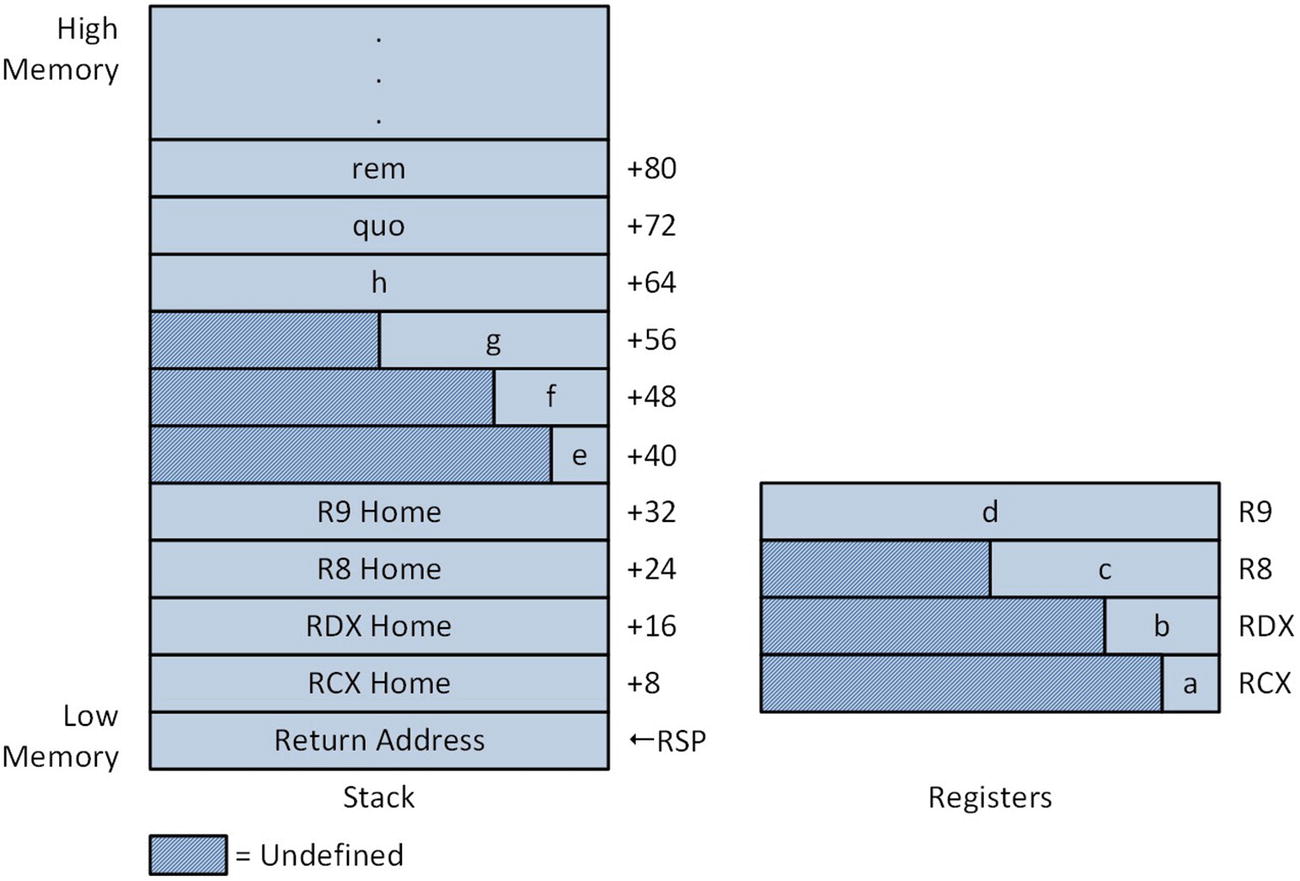

Argument registers and stack at entry to function IntegerMul_

The first instruction of IntegerMul_, movsx rax,cl (Move with Sign Extension), sign-extends a copy of the 8-bit integer value a that’s in register CL to 64 bits and saves this value in register RAX. Note that the original value in register CL is unaltered by this operation. Another movsx instruction follows that saves a 64-bit sign-extend copy of the 16-bit value d to RDX. Like the previous movsx instruction, the source operand is not modified by this operation. An imul rax,rdx instruction computes the product of a and b. The two-operand form of the imul instruction that’s used here saves only the lower 64 bits of the 128-bit product in the destination operand RAX. The next instruction movsxd rcx,r8d sign-extends the 32-bit operand c to 64 bits. Note that a different instruction mnemonic is required when sign extending a 32-bit integer to 64 bits. The next two imul instructions compute the intermediate product a * b * c * d.

Calculation of the second intermediate product e * f * g * h is carried out next. All of these argument values were passed using the stack as shown in Figure 2-2. The movsx rcx,byte ptr [rsp+40] sign extends a copy of the 8-bit argument value e that’s located on the stack and saves the result to register RCX. The text byte ptr is a MASM directive that acts like a C++ cast operator and conveys to the assembler the size of the source operand. Without the byte ptr directive, the movsx instruction is ambiguous since several different sizes are possible for the source operand. The argument value f is loaded next using a movsx rdx,word ptr [rsp+48] instruction . Following calculation of the intermediate product e * f using an imul instruction, a movsxd rdx,dword ptr[rsp+56] instruction loads a sign-extended copy of g into RDX. This is followed by an imul rdx,qword ptr[rsp+64] instruction that calculates the intermediate product g * h. Use of the qword ptr directive is optional here; size directives are often used in this manner to improve program readability. The final two imul instructions calculate the final product.

Argument registers and stack at entry to function UnsignedIntegerDiv_

Memory Addressing and Condition Codes

Thus far the source code examples of this chapter have primarily illustrated how to use basic arithmetic and logical instructions. In this section, you’ll learn more about the x86’s memory addressing modes. You’ll also examine sample code that demonstrates how to exploit some of the x86’s condition-code based instructions.

Memory Addressing Modes

Example Ch02_06

Toward the top of the C++ code are the requisite declaration statements for this example. Earlier in this chapter you learned how to reference a C++ global variable in an assembly language function. In this example, the opposite is illustrated. Storage space for the variables NumFibVals_ and FibValsSum_ is defined in the assembly language code, and these variables are referenced in the function main.

In the assembly language function MemoryOperands_, argument i is employed as an index into an array (or lookup table) of constant integers, while the four pointer arguments are used to save values loaded from the lookup table using different addressing modes. Near the top of Listing 2-6 is a .const directive, which defines a memory block that contains read-only data. Immediately following the .const directive, a lookup table named FibVals is defined. This table contains 16 doubleword integer values. The text dword is an assembler directive that is used to allocate storage space and optionally initialize a doubleword value (the text dd can also be used as a synonym for dword).

The final line of the .const section declares NumFibVals_ as a public symbol in order to enable its use in main. The .data directive denotes the start of a memory block that contains modifiable data. The FibValsSum_ dword ? statement defines an uninitialized doubleword value, and the subsequent public statement makes it globally accessible.

Let’s now look at the assembly language code for MemoryAddressing_. Upon entry into the function, the argument i is checked for validity since it will be used as an index into the lookup table FibVals. The cmp ecx,0 instruction compares the contents of ECX, which contains i, to the immediate value 0. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the processor carries out this comparison by subtracting the source operand from the destination operand. It then sets the status flags based on the result of the subtraction (the result is not saved to the destination operand). If the condition ecx < 0 is true, program control will be transferred to the location specified by the jl (Jump if Less) instruction. A similar sequence of instructions is used to determine if the value of i is too large. The cmp ecx,[NumFibVals_] instruction compares ECX against the number of elements in the lookup table. If ecx >= [NumFibVals] is true, a jump is performed to the target location specified by the jge (Jump if Greater or Equal) instruction.

Immediately following the validation of i, a movsxd rcx,ecx sign-extends the table index value to 64 bits. Sign-extending or zero-extending a 32-bit integer to a 64-bit integer is often necessary when using an addressing mode that employs an index register as you’ll soon see. The subsequent mov [rsp+8],rcx saves a copy of the signed-extended table index value to the RCX home area on the stack and is done primarily to exemplify use of the stack home area.

The remaining instructions of MemoryAddressing_ illustrate accessing items in the lookup table using various memory addressing modes. The first example uses a single base register to read an item from the table. In order to use a single base register, the function must explicitly calculate the address of the i-th table element, which is achieved by adding the offset (or starting address) of FibVals and the value i * 4. The mov r11,offset FibVals instruction loads R11 with the correct table offset value. This is followed by a shl rcx,2 instruction that determines the offset of the i-th item relative to the start of the lookup table. An add r11,rcx instruction calculates the final address. Once this is complete, the specified table value is read using a mov eax,[r11] instruction. It is then saved to the memory location specified by the argument v1.

In the second example, the table value is read using BaseReg+IndexReg memory addressing. This example is similar to the first one except that the processor computes the final effective address during execution of the mov eax,[r11+rcx] instruction. Note that recalculation of the lookup table element offset using the mov rcx,[rsp+8] and shl rcx,2 instructions is unnecessary here but included to illustrate use of the stack home area.

The third example demonstrates use of BaseReg+IndexReg*ScaleFactor memory addressing. In this example, the offset of FibVals and the value i are loaded into registers R11 and RCX, respectively. The correct table value is loaded into EAX using a mov eax,[r11+rcx*4] instruction. In the fourth (and somewhat contrived) example, BaseReg+IndexReg*ScaleFactor+Disp memory addressing is demonstrated. The fifth and final memory address mode example uses an add[FibValsSum_],eax instruction to demonstrate RIP-relative addressing. This instruction, which uses a memory location as a destination operand, updates a running sum that is ultimately displayed by the C++ code.

Given the multiple addressing modes that are available on an x86 processor, you might wonder which mode should be used. The answer to this question depends on a number of factors, including register availability, the number of times an instruction (or sequence of instructions) is expected to execute, instruction ordering, and memory space vs. execution time tradeoffs. Hardware features such as the processor’s underlying microarchitecture and cache sizes also need to be considered.

When coding an x86 assembly language function, one suggested guideline is to favor simple (a single base register or displacement) rather than complex (multiple registers) memory addressing. The drawback of this approach is that the simpler forms generally require the programmer to code longer instruction sequences and may consume more code space. The use of a simple form also may be imprudent if extra instructions are needed to preserve non-volatile registers on the stack (non-volatile registers are explained in Chapter 3). Chapter 15 considers in greater detail some of the issues and tradeoffs that can affect the efficiency of assembly language code.

Condition Codes

Example Ch02_07

When developing code to implement a particular algorithm, it is often necessary to determine the minimum or maximum value of two numbers. The standard C++ library defines two template functions named std::min() and std::max() to perform these operations. The assembly language code that’s shown in Listing 2-7 contains several three-argument versions of signed-integer minimum and maximum functions. The purpose of these functions is to illustrate proper use of the jcc and cmovcc instructions. The first function, called SignedMinA_, finds the minimum value of three signed integers. The first code block determines min(a, b) using two instructions: cmp eax,ecx and jle @F. The cmp instruction, which you saw earlier in this chapter, subtracts the source operand from the destination operand and sets the status flags based on the result (the result is not saved). The operand of the jle (Jump if Less or Equal) instruction, @F, is an assembler symbol that designates nearest forward @@ label as the target of the conditional jump (the symbol @B can be used for backward jumps). Following calculation of min(a, b), the next code block determines min(min(a, b), c) using the same technique. With the result already present in register EAX, SignedMinA_ can return to the caller.

The function SignedMaxA_ uses the same approach to find the maximum of three signed integers. The only difference between SignedMaxA_ and SignedMinA_ is the use of a jge (Jump if Greater or Equal) instead of a jle instruction. Versions of SignedMinA_ and SignedMaxA_ that operate on unsigned integers can be easily created by changing the jle and jge instructions to jbe (Jump if Below or Equal) and jae (Jump if Above or Equal), respectively. Recall from the discussion in Chapter 1 that condition codes using the words “greater” and “less” are intended for signed integer operands, while “above” and “below” are used with unsigned integer operands.

The assembly language code also contains the functions SignedMinB_ and SignedMaxB_. These functions determine the minimum and maximum of three signed integers using conditional move instructions instead of conditional jumps. The cmovcc instruction tests the specified condition and if it’s true, the source operand is copied to the destination operand. If the specified condition is false, the destination operand is not altered.

The use of a conditional move instruction to eliminate one or more conditional jump statements frequently results in faster code, especially in situations where the processor is unable to accurately predict whether the jump will be performed. You’ll learn more about some of issues related to optimal use of the conditional jump and conditional move instructions in Chapter 15.

Summary

The add and sub instructions perform integer (signed and unsigned) addition and subtraction.

The imul and idiv instructions carry out signed integer multiplication and division. The corresponding instructions for unsigned integers are mul and div. The idiv and div instructions usually require the dividend to be sign- or zero-extended prior to use.

The and, or, and xor instructions are used to perform bitwise AND, inclusive OR, and exclusive OR operations. The shl and shr instructions execute logical left and right shifts; sar is used for arithmetic right shifts.

Nearly all arithmetic, logical, and shift instructions set the status flags to indicate the results of an operation. The cmp instruction also sets the status flags. The jcc and cmovcc instructions can be used to alter program flow or perform conditional data moves based on the state of one or more status flags.

The x86-64 instruction set supports a variety of different address modes for accessing operands stored in memory.

MASM uses the .code, .data, and .const directives to designate code, data, and constant data sections. The directives proc and endp denote the beginning and end of an assembly language function.

The Visual C++ calling convention requires a calling function to use registers RCX, RDX, R8, and R9 (or the low-order portions of these registers for values smaller than 64 bits) for the first four integer or pointer arguments. Additional arguments are passed on the stack.

To disable the creation of decorated names by the C++ compiler, assembly language functions must be declared using the extern "C" modifier. Global variables shared between C++ and assembly language code must also use the extern "C" modifier.