Chapter 12. Libraries

And if I really wanted to learn something I’d listen to more records.

And I do, we do, you do.—The Hives, “Untutored Youth”

This chapter will cover a few libraries that will make your life easier.

My impression is that C libraries have grown less pedantic over the

years. Ten years ago, the typical library provided the minimal set of tools

necessary for work, and expected you to build convenient and

programmer-friendly versions from those basics. The typical library would

require you to perform all memory allocation, because it’s not the place of

a library to grab memory without asking. Conversely, the libraries presented

in this chapter all provide an “easy” interface, like curl_easy_... functions for cURL, Sqlite’s single

function to execute all the gory steps of a database transaction, or the

three lines of code we need to set up a mutex via GLib. If they need

intermediate workspaces to get the work done, they just do it. They are fun

to use.

I’ll start with somewhat standard and very general libraries, and move on to a few of my favorite libraries for more specific purposes, including SQLite, the GNU Scientific Library, libxml2, and libcURL. I can’t guess what you are using C for, but these are friendly, reliable systems for doing broadly applicable tasks.

GLib

Given that the standard library left so much to be filled in, it is only natural that a library would eventually evolve to fill in the gaps. GLib implements enough basic computing needs that it will pass the first year of CompSci for you, is ported to just about everywhere (even POSIX-less editions of Windows), and is at this point stable enough to be relied on.

I’m not going to give you sample code for the GLib, because I’ve already given you several samples:

The lighting-quick intro to linked lists in Example 2-2.

A test harness, in Unit Testing.

Unicode tools, in Unicode.

Hashes, in Generic Structures.

Reading a text file into memory, in Count References.

Perl-compatible regular expression parsing, also in the section Count References.

And over the next few pages, I’ll mention GLib’s contributions for:

Wrapping

mmapfor both POSIX and Windows, in Using mmap for Gigantic Data Sets.Mutexes, in Easy Threading with Pthreads.

There’s more: if you are writing a mouse-and-window program, then you will need an event loop to catch and dispatch mouse and keyboard events; GLib provides this. There are file utilities that do the right thing on POSIX and non-POSIX (i.e., Windows) systems. There’s a simple parser for configuration files, and a lightweight lexical scanner for more complex processes. Et cetera.

POSIX

The POSIX standard adds several useful functions to the standard C library. Given how prevalent POSIX is, they are worth getting to know.

Using mmap for Gigantic Data Sets

I’ve mentioned the three types of memory (static, manual, and

automatic), and here’s a fourth: disk based. With this type, we take a

file on the hard drive and map it to a location in memory using mmap.

This is often how shared libraries work: the system finds

libwhatever.so, assigns

a memory address to the segment of the file representing a needed

function, and there you go: you’ve loaded a function into memory.

Or, we could share data across processes by having them both

mmap the same file.

Or, we could use this to save data structures to memory.

mmap a file to memory, use memmove to copy your in-memory data structure

to the mapped memory, and it’s stored for next time. Problems come up

when your data structure has a pointer to another data structure;

converting a series of pointed-to data structures to something savable

is the serialization problem, which I won’t cover

here.

And, of course, there’s dealing with data sets too large to fit in

memory. The size of an mmaped array is constrained by

the size of your disk, not memory.

Example 12-1 presents sample code. The load_mmap routine does most of the work. If

used as a malloc, then it needs to

create the file and stretch it to the right size; if you are opening an

already-existing file, it just has to be opened and

mmaped.

#include <stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> //lseek, write, close #include <stdlib.h> //exit #include <fcntl.h> //open #include <sys/mman.h> #include "stopif.h" #define Mapmalloc(number, type, filename, fd) \load_mmap((filename), &(fd), (number)*sizeof(type), 'y') #define Mapload(number, type, filename, fd) \ load_mmap((filename), &(fd), (number)*sizeof(type), 'n') #define Mapfree(number, type, fd, pointer) \ releasemmap((pointer), (number)*sizeof(type), (fd)) void *load_mmap(char const *filename, int *fd, size_t size, char make_room){

*fd=open(filename, make_room=='y' ? O_RDWR | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC : O_RDWR, (mode_t)0600); Stopif(*fd==-1, return NULL, "Error opening file"); if (make_room=='y'){ // Stretch the file size to the size of the (mmapped) array int result=lseek(*fd, size-1, SEEK_SET); Stopif(result==-1, close(*fd); return NULL, "Error stretching file with lseek"); result=write(*fd, "", 1); Stopif(result!=1, close(*fd); return NULL, "Error writing last byte of the file"); } void *map=mmap(0, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, *fd, 0); Stopif(map==MAP_FAILED, return NULL, "Error mmapping the file"); return map; } int releasemmap(void *map, size_t size, int fd){

Stopif(munmap(map, size) == -1, return -1, "Error un-mmapping the file"); close(fd); return 0; } int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int fd; long int N=1e5+6; int *map = Mapmalloc(N, int, "mmapped.bin", fd); for (long int i = 0; i <N; ++i) map[i] = i;

Mapfree(N, int, fd, map); //Now reopen and do some counting. int *readme = Mapload(N, int, "mmapped.bin", fd); long long int oddsum=0; for (long int i = 0; i <N; ++i) if (readme[i]%2) oddsum += i; printf("The sum of odd numbers up to %li: %lli\n", N, oddsum); Mapfree(N, int, fd, readme); }

I wrapped the functions that follow in macros so you don’t have to type

sizeofevery time, and won’t have to remember how to callload_mmapwhen allocating versus when loading.

The macros hide that this function gets called two different ways. If only reopening existing data, the file gets opened,

mmapgets called, the results are checked, and that’s all. If called as an allocate function, we need to stretch the file to the right length.

Releasing the mapping requires using

munmap, which is akin tomalloc’s friendfree, and closing the file handle. The data is left on the hard drive, so when you come back tomorrow you can reopen it and continue where you left off. If you want to remove the file entirely, useunlink("filename").

The payoff: you can’t tell

mapis on disk and not in the usual memory.

Final details: the mmap

function is POSIX-standard, so it is available everywhere but Windows

boxes and some embedded devices. In Windows, you can do the identical

thing but with different function names and flags; see CreateFileMapping and MapViewOfFile. GLib wraps both mmap and the Windows functions in an

if POSIX … else if Windows … construct and names

the whole thing g_mapped_file_new.

Easy Threading with Pthreads

If your computer is less than about five years old and is not a telephone, then it has several cores, which are independent pipelines for processing. How many cores do you have? To find out, run the following:

Linux:

grep cores /proc/cpuinfo.Mac:

sysctl hw.logicalcpu.Cygwin:

env | grep NUMBER_OF_PROCESSORS.

Threading is billed as a complex and arcane topic, but when I first implemented threads in a program, I was delighted by how easy it is to get a serial loop to become a set of parallel threads. It’s not the syntax; the hard part is in dealing with the details of how threads interact.

The simplest case, sometimes called a process that is embarrassingly parallel, is when you are applying the same task to every element of an array, and each is independent of the other. Any shared data is used read-only. As per the nickname for this kind of thing, this is the easy case, and I’ll show you the syntax for making it work next.

The first complication is when there is some resource that is writable and is shared across threads. Let us say that we have two threads doing some simple arithmetic:

int a=0;

//Thread 1:

a++;

a*=2;

printf("T1: %i\n", a);//Thread 2:

printf("T2: %i\n", a);

a++;It’s anybody’s guess what this might print. Maybe thread two will run first, so we’ll get:

T2: 0 T1: 4

It is not impossible for the commands in the threads to alternate, like so:

a++; //T1

printf("T2: %i\n", a); //T2, prints T2: 1

a*=2; //T1

a++; //T2

printf("T1: %i\n", a); //T1, prints T1: 3It gets worse, because a single line of C like a++ can consist of several machine

instructions, and we have no idea what a looks like halfway through an

increment.

A mutex locks a resource (here, a) while in use by one thread, and tells the

other threads that want to use the resource to hold on until the prior

thread is done and releases the lock.

When you have multiple mutexes that may interact, then you’re up to rocket science. It’s easy for threads to get into states where both are waiting for the other to release a mutex or some other odd case occurs that causes the threads to trample each other, and debugging this sort of thing is now a question of the luck of replicating the surprising order of execution when the debugger is running. But the simple stuff here will already be enough for you to safely speed up your code.

The pthreads checklist

You have a for loop over

elements, such as an operation on every element of an array. As

earlier, no one iteration of the loop has any bearing on any other. If

the iterations were somehow run in random order, you wouldn’t care, as

long as every array element gets hit once and only once.

We’re going to turn that serial for loop into parallel threads. We are going

to convert the body of the loop (one iteration) into a function that

will be applied to each element of the array, using pthread_create, and then use pthread_join to wait for each thread to

return. At the end of that disperse/gather procedure, the program can

continue as if nothing special had happened.

For gcc, Clang, or Intel, add

-pthreadto the compiler line.#include <pthreads.h>.Write a wrapper function, which will be called by every thread. It has to have a signature of the form

void * your_function (void *). That is, it takes one void pointer in and spits one void pointer out. If you started with aforloop, paste the body of the loop into this wrapper, and do the appropriate surgery so that you are acting on the function input instead of element i of the array.Disperse the threads: your

forloop now appliespthread_createto each array element. See the following example.Gather the threads: Write a second

forloop to callpthread_jointo gather all of the threads and check their return values.

Example 12-3 presents an example. I am sorry to

say that it is a word counter, which is such a typical example.

However, it’s at least a zippy one, which runs about 3x faster than

wc. (The definitions of a word also

differ, so it’ll be hard to seriously compare, though.) The focus is

on the implementation of the preceding gather/disperse

procedure.

I use the string utilities from Example 9-5, and that will need GLib. At this point, the makefile is as in Example 12-2.

gthread-2.0 part is necessary only if you are

using GLib’s mutexes (pthreads.make)P=pthreadsobjects=string_utilities.o# To use Glib mutexes, some systems will require bothglib-2.0andgthread-2.0.CFLAGS=`pkg-config--cflagsglib-2.0`-g-Wall-std=gnu99-O3-pthreadLDLIBS=`pkg-config--libsglib-2.0`-lpthread$(P):$(objects)

#include "stopif.h"

#include "string_utilities.h"

#include <pthread.h>

typedef struct{

int wc;

char *docname;

} wc_struct;

void *wc(void *voidin){

wc_struct *in = voidin;  char *doc = string_from_file(in->docname);

char *doc = string_from_file(in->docname);  if (!doc) return NULL; // in->wc remains zero.

char *delimiters = " `~!@#$%^&*()_-+={[]}|\\;:\",<>./?\n";

ok_array *words = ok_array_new(doc, delimiters);

if (!doc) return NULL; // in->wc remains zero.

char *delimiters = " `~!@#$%^&*()_-+={[]}|\\;:\",<>./?\n";

ok_array *words = ok_array_new(doc, delimiters);  if (!words) return NULL;

in->wc = words->length;

ok_array_free(words);

return NULL;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

argc--;

argv++;

if (!words) return NULL;

in->wc = words->length;

ok_array_free(words);

return NULL;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

argc--;

argv++;  Stopif(!argc, return 0, "Please give some file names on the command line.");

pthread_t threads[argc];

wc_struct s[argc];

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++){

s[i] = (wc_struct){.docname=argv[i]};

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, wc, &s[i]);

Stopif(!argc, return 0, "Please give some file names on the command line.");

pthread_t threads[argc];

wc_struct s[argc];

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++){

s[i] = (wc_struct){.docname=argv[i]};

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, wc, &s[i]);  }

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);  for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) printf("%s:\t%i\n",argv[i], s[i].wc);

}

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) printf("%s:\t%i\n",argv[i], s[i].wc);

}

As discussed in The Void Pointer and the Structures It Points To, the throwaway typedef,

wc_struct, adds immense safety. I still have to be careful to write the inputs and outputs to the pthread system correctly, but the internals of the struct get type-checked, both inmainand here in the wrapper function. Next week, when I changewcto along int, the compiler will warn me if I don’t do the change correctly.

string_from_filereads the given document into a string, and is borrowed from the string utilities in Example 9-5.

Also borrowed from the string utility library, this function divides a string at the given delimiters. We just want the count from it.

argv[0]is the name of the program, so we step theargvpointer past it. The rest of the arguments on the command line are files to be word-counted.

This is the thread creation step. We set up a list of thread info pointers, and then we send to

pthread_createone of those, the wrapper function, and an item to send in to the wrapper function. Don’t worry about the second argument, which controls some threading attributes.

This second loop gathers outputs. The second argument to

pthread_joinis an address where we could write the output from the threaded function (wc). I cheat and just write the output to the input structure, which saves somemallocing; if you think the program would be more readable if there were a separate output struct, I would not bicker with you.At the end of this loop, the threads have all been gathered, and the program is once again single-threaded.

Note

Your Turn: Now that you have the form down (or at least, you have a template you can cut and paste), check your code for embarrassingly parallel loops, and thread ’em.

Earlier, I gave each row of an array one thread; how would you split something into a more sensible number, like two or three threads? Hint: you’ve got a struct, so you can send in extra info, like start/endpoints for each thread.

Protect threaded resources with mutexes

What about the case where

some resource may be modified by some of the threads? We can retain

consistency via the mutex, which provides mutual

exclusion. We will provide one mutex for each resource to be shared,

such as a read/write variable i. Any thread

may lock the mutex, so that when other threads try to claim the mutex,

they are locked out and have to wait. So, for example:

The write thread claims the mutex for

iand begins writing.The read thread tries to claim the mutex, is locked out.

The write thread keeps writing.

The read thread pings the mutex—Can I come in now? It is rejected.

The write thread is done and releases the mutex.

The read thread pings the mutex, and is allowed to continue. It locks the mutex.

The write thread is back to write more data. It pings the mutex, but is locked out, and so has to wait.

Et cetera. The read thread is guaranteed that there won’t be shenanigans about transistors in memory changing state mid-read, and the write thread is similarly guaranteed that things will be clean.

So any time we have a resource, like stdout or a variable, at least one thread that wants to modify the resource, and one or more threads that will read or write the resource, we will attach a mutex to the resource. At the head of each thread’s code to use the resource, we lock the mutex; at the end of that block of code, we release the mutex.

What if one thread never gives up a mutex? Maybe it’s caught in an infinite loop. Then all the threads that want to use that mutex are stuck at the step where they are pinging the mutex over and over, so if one thread is stuck, they all are. In fact, stuck pinging a mutex that is never released sounds a lot like an infinite loop. If thread A has locked mutex 1 and is waiting for mutex 2, and thread B has locked mutex 2 and is waiting for mutex 1, you’ve got a deadlock.

If you are starting out with threading, I recommend that any given block of code lock one mutex at a time. You can often make this work by just associating a mutex with a larger block of code that you might have thought deserved multiple mutexes.

The example

Let us rewrite the wc

function from earlier to increment a global counter along with the

counters for each thread. If you throw a lot of threads at the

program, you’ll be able to see if they all get equal time or run in

serial despite our best efforts. The natural way to maintain a global

count is by tallying everything at the end, but this is a simple and

somewhat contrived example, so we can focus on wiring up the

mutex.

If you comment the mutex lines, you’ll be able to watch the threads walking all over each other. To facilitate this, I wrote:

for(inti=0;i<out->wc;i++)global_wc++;

which is entirely equivalent to:

global_wc+=out->wc;

but takes up more processor time.

You may need to add gthread-2.0 to the makefile above to get

this running.

All of the mutex-oriented changes were inside the function itself. By allocating a mutex to be a static variable, all threads see it. Then, each thread by itself tries the lock before changing the global word count, and unlocks when finished with the shared variable.

Example 12-4 presents the code.

#include "string_utilities.h"

#include <pthread.h>

#include <glib.h> //mutexes

long int global_wc;

typedef struct{

int wc;

char *docname;

} wc_struct;

void *wc(void *voidin){

wc_struct *in = voidin;

char *doc = string_from_file(in->docname);

if (!doc) return NULL;

static GMutex count_lock;  char *delimiters = " `~!@#$%^&*()_-+={[]}|\\;:\",<>./?\n\t";

ok_array *words = ok_array_new(doc, delimiters);

if (!words) return NULL;

in->wc = words->length;

ok_array_free(words);

g_mutex_lock(&count_lock);

char *delimiters = " `~!@#$%^&*()_-+={[]}|\\;:\",<>./?\n\t";

ok_array *words = ok_array_new(doc, delimiters);

if (!words) return NULL;

in->wc = words->length;

ok_array_free(words);

g_mutex_lock(&count_lock);  for (int i=0; i< in->wc; i++)

global_wc++; //a slow global_wc += in->wc;

g_mutex_unlock(&count_lock);

for (int i=0; i< in->wc; i++)

global_wc++; //a slow global_wc += in->wc;

g_mutex_unlock(&count_lock);  return NULL;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

argc--;

argv++; //step past the name of the program.

pthread_t threads[argc];

wc_struct s[argc];

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++){

s[i] = (wc_struct){.docname=argv[i]};

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, wc, &s[i]);

}

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) printf("%s:\t%i\n",argv[i], s[i].wc);

printf("The total: %li\n", global_wc);

}

return NULL;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

argc--;

argv++; //step past the name of the program.

pthread_t threads[argc];

wc_struct s[argc];

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++){

s[i] = (wc_struct){.docname=argv[i]};

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, wc, &s[i]);

}

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

for (int i=0; i< argc; i++) printf("%s:\t%i\n",argv[i], s[i].wc);

printf("The total: %li\n", global_wc);

}

Because the declaration is static, it is shared across all instances of the function. Also, it is initialized to zero.

The next few lines use a variable shared across threads, so this is the appropriate place to set a checkpoint.

Here, we are done with the shared resource, so release the lock. These three marked lines (declare/init, lock, unlock) are all we need for the mutex.

Note

Your Turn: Try this on a few dozen files. I used the complete works of Shakespeare, because I have Gutenberg’s Shakespeare broken up by play; I’m sure you’ve got some files on hand to try out. After you run it as is, comment out the lock/unlock lines, and rerun. Do you get the same counts?

_Thread_local and static variables

All of the static variables

in a program, meaning those declared outside of a function plus those

inside a function with the static

keyword, are shared across all threads. Same with anything malloced (that is, each thread may call

malloc to produce a pocket of

memory for its own use, but any thread that has the address could

conceivably use the data there). Automatic variables are specific to

each thread.

As promised, here’s your fifth type of memory. C11 provides a

keyword, _Thread_local, that splits

off a static variable (either in the file scope or in a function via

the static keyword) so that each

thread has its own version, but the variable still behaves like a

static variable when determining scope and not erasing it at the end

of a function. The variable is initialized when the threads start and

is removed when the threads exit.

C11’s new keyword seems to be an emulation of the gcc-specific

__thread keyword. If this is useful

to you, within a function, you can use either of:

static __thread int i; //GCC-specific; works today.

// or

static _Thread_local int i; //C11, when your compiler implements it.[21]You can check for which to use via a block of preprocessor

conditions, like this one, which sets the string threadlocal to the right thing for the given

situation.

#undef threadlocal #ifdef _ISOC11_SOURCE #define threadlocal _Thread_local #elif defined(__APPLE__) #define threadlocal #elif defined(__GNUC__) && !defined(threadlocal) #define threadlocal __thread #else #define threadlocal #endif

/* The globalstate variable is thread-safe if you are using a C11-compliant compiler or the GCC (but not on Macs). Otherwise, good luck. */ static threadlocal int globalstate;

Outside of a function, the static keyword is optional, as

always.

The GNU Scientific Library

If you ever read somebody asking a question that starts I’m trying to implement something from Numerical Recipes in C… [Press 1992], the correct response is almost certainly download the The GNU Scientific Library (GSL), because they already did it for you [Gough 2003].

Some means of numerically integrating a function are just better than others, and as hinted in Deprecate Float, some seemingly sensible numeric algorithms will give you answers that are too imprecise to be considered anywhere near correct. So especially in this range of computing, it pays to use existing libraries where possible.

At the least, the GSL provides a reliable random number generator (the C-standard RNG may be different on different machines, which makes it inappropriate for reproducible inquiry), and vector and matrix structures that are easy to subset and otherwise manipulate. The standard linear algebra routines, function minimizers, basic statistics (means and variances), and permutation structure may be of use to you even if you aren’t spending all day crunching numbers.

And if you know what an Eigenvector, Bessel function, or Fast Fourier Transform are, then here’s where you can get them.

I give an example of the GSL’s use in Example 12-5,

though you’ll notice that the string gsl_ only appears once or twice in the example.

The GSL is a fine example of an old-school library that provides the

minimal tools needed and then expects you to build the rest from there.

For example, the GSL manual will show you the page of boilerplate you will

need to use the provided optimization routines to productive effect. It

felt like something the library should do for us, and so I wrote a set of

wrapper functions for portions of the GSL, which became

Apophenia, a library aimed at modeling with data. For

example, the apop_data struct binds

together raw GSL matrices and GSL vectors with row/column names and an

array of text data, which brings the basic numeric-processing structs

closer to what real-world data looks like. The library’s calling

conventions look like the modernized forms in Chapter 10.

An optimizer has a setup much like the routines in The Void Pointer and the Structures It Points To, where

routines took in any function and used the provided function as a black

box. The optimizer tries an input to the given function and uses the

output value to improve its next guess for an input that will produce a

larger output; with a sufficiently intelligent search algorithm, the

sequence of guesses will converge to the function-maximizing input. The

procedure is relatively complex (over how many dimensions is the optimizer

searching? Is the optimization relative to some reference data set? Which

search procedure should the optimizer use?), so the apop_estimate function takes in an apop_model struct with hooks for the function

and the relevant additional information.

In typical use, the reference data set comes from a text file (read

via apop_text_to_data), and the model

struct is a standard model that ships with the library, such as ordinary least squares

regression. Example 12-5 sets up an optimization in

greater detail. It first presents a distance function that calculates the total

distance from the parameters in the input model struct and the list of

input data points, then declares a model struct holding that function and

advice on the input vector’s size (and a slot for the optimizer to put its

guesses for parameter values), then attaches optimization settings to that

model. The data set is prepared in main. When all that setup is done, the

optimization is a one-line call to apop_estimate, which spits out a model struct

with its parameters set to the point that minimizes total distance to the

input data points.

#include <apop.h>

double one_dist(gsl_vector *v1, void *v2){

return apop_vector_distance(v1, v2);

}

double distance(apop_data *data, apop_model *model){

gsl_vector *target = model->parameters->vector;

return -apop_map_sum(data, .fn_vp=one_dist, .param=target, .part='r');  }

apop_model min_distance={.name="Minimum distance to a set of input points.",

}

apop_model min_distance={.name="Minimum distance to a set of input points.",  .p=distance, .vbase=-1};

.p=distance, .vbase=-1};  int main(){

apop_data *locations = apop_data_fill(

int main(){

apop_data *locations = apop_data_fill(  apop_data_alloc(5, 2),

1.1, 2.2,

4.8, 7.4,

2.9, 8.6,

-1.3, 3.7,

2.9, 1.1);

Apop_model_add_group(&min_distance, apop_mle, .method= APOP_SIMPLEX_NM,

apop_data_alloc(5, 2),

1.1, 2.2,

4.8, 7.4,

2.9, 8.6,

-1.3, 3.7,

2.9, 1.1);

Apop_model_add_group(&min_distance, apop_mle, .method= APOP_SIMPLEX_NM,  .tolerance=1e-5);

Apop_model_add_group(&min_distance, apop_parts_wanted);

.tolerance=1e-5);

Apop_model_add_group(&min_distance, apop_parts_wanted);  apop_model *est = apop_estimate(locations, min_distance);

apop_model *est = apop_estimate(locations, min_distance);  apop_model_show(est);

}

apop_model_show(est);

}

Map the input function

one_distto every row (.part='r') of the input data set, thus calculating the distance between that row and thetargetvector (sent as thevoid *input to the function), then sum the distances to find total distance. It is a common trick to turn a maximizer into a minimizer by negating the objective function; we seek the minimum total distance, so the function returns the negation of the sum.

The

apop_modelstruct includes over a dozen elements, but designated initializers save the day yet again, and we need only declare the elements we use.

The

.vbaseis normally set to the number of elements in the vector the optimizer is searching for. As a special case that is common in modeling settings, setting.vbase=-1indicates that the parameter count should equal the number of columns in the data set.

The first argument to

apop_data_fillis an already-allocated data set; here, we allocate one just in time, then fill the grid just allocated with five 2D points.

This line adds notes to the model about the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE): use the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm, and keep trying until the algorithm’s error measure is less than 1e-5. Add

.verbose=1for some information about each iteration of the optimization search.

Being a stats library, Apophenia finds the covariance and other statistical measures of the parameters. We don’t need that information here, so a blank

apop_parts_wantedgroup tells the optimizer that none of the auxiliary information should be calculated.

This line will prep the

apop_modelstruct by allocating aparametersset and aninfoset (which will mostly be NaNs in this case). It will then fill the parameters set with test points, evaluate the distance to that test point using themin_distance.pfunction, and use the test evaluations to refine later test points, until the convergence criterion is met and the search declares that it has reached a minimum.

SQLite

Structured Query Language (SQL) is a roughly human-readable means of interacting with a database. Because the database is typically on disk, it can be as large as desired. An SQL database has two especial strengths for these large data sets: taking subsets of a data set and joining together data sets.

I won’t go into great detail about SQL, because there are voluminous

tutorials available. If I may cite myself, [Klemens 2008] has a chapter on SQL and using it from C, or

just type sql tutorial into your favorite

search engine. The basics are pretty simple. Here, I will focus on getting

you started with the SQLite library itself.

SQLite provides a database via a single C file plus a single header.

That file includes the parser for SQL queries, the various internal

structures and functions to talk to a file on disk, and a few dozen

interface functions for our use in interacting with the database. Download

the file, unzip it into your project directory, add sqlite3.o to the objects line of your makefile, and you’ve got a

complete SQL database engine on hand.

There are only a few functions that you will need to interact with, to open the database, close the database, send a query, and get rows of data from the database.

Here are some serviceable database-opening and -closing functions:

sqlite3 *db=NULL; //The global database handle. int db_open(char *filename){ if (filename) sqlite3_open(filename, &db); else sqlite3_open(":memory:", &db); if (!db) {printf("The database didn't open.\n"); return 1;} return 0; } //The database closing function is easy: sqlite3_close(db);

I prefer to have a single global database handle. If I need to open

multiple databases, then I use the SQL attach command to open another database. The SQL

to use a table in such an attached database might look like:

attach "diskdata.db" asdiskdb; create indexdiskdb.index1ondiskdb.tab1(col1); select * fromdiskdb.tab1wherecol1=27;

If the first database handle is in memory, and all on-disk databases

are attached, then you will need to be explicit about which new tables or

indices are being written to disk; anything you don’t specify will be

taken to be a temporary table in faster, throwaway memory. If you forget

and write a table to memory, you can always write it to disk later using a

form like create table

diskdb.saved_table as

select * from table_in_memory.

The Queries

Here is a macro for sending SQL that doesn’t return a value to the

database engine. For example, the attach and create

index queries tell the database to take an action, but return

no data.

#define ERRCHECK {if (err!=NULL) {printf("%s\n",err); return 0;}}#define query(...){char *query; asprintf(&query, __VA_ARGS__); \char *err=NULL; \sqlite3_exec(db, query, NULL,NULL, &err); \ERRCHECK \free(query); free(err);}

The ERRCHECK macro is straight

out of the SQLite manual. I wrap the call to sqlite3_exec in a macro so that you can write

things like:

for(inti=0;i<col_ct;i++)query("create index idx%i on data(col%i)",i,i);

Building queries via printf-style string construction is the norm

for SQL-via-C, and you can expect that more of your queries will be

built on the fly than will be verbatim from the source code. This format

has one pitfall: SQL like clauses and

printf bicker over the % sign, so query("select * from data where col1 like

'p%%nts'") will fail, as printf thinks the %% was meant for it. Instead, query("%s", "select * from data where col1 like

'p%%nts'") works. Nonetheless, building queries on the fly is

so common that it’s worth the inconvenience of an extra %s for fixed queries.

Getting data back from SQLite requires a callback function, as per Functions with Generic Inputs. Here is an example that prints to the screen.

intthe_callback(void*ignore_this,intargc,char**argv,char**column){for(inti=0;i<argc;i++)printf("%s,\t",argv[i]);printf("\n");return0;}#define query_to_screen(...){ \char *query; asprintf(&query, __VA_ARGS__); \char *err=NULL; \sqlite3_exec(db, query, the_callback, NULL, &err); \ERRCHECK \free(query); free(err);}

The inputs to the callback look a lot like the inputs to main: you get an argv, which is a list of text elements of

length argc. The column names (also a

text list of length argc) are in

column. Printing to screen means that

I treat all of the strings as such, which is easy enough. So is a

function that fills an array, for example:

typedef{double*data;introws,cols;}array_w_size;intthe_callback(void*array_in,intargc,char**argv,char**column){array_w_size*array=array_in;*array=realloc(&array->data,sizeof(double)*(++(array->rows))*argc);array->cols=argc;for(inti=0;i<argc;i++)array->data[(array->rows-1)*argc+i]=atof(argv[i]);}#define query_to_array(a, ...){\char *query; asprintf(&query, __VA_ARGS__); \char *err=NULL; \sqlite3_exec(db, query, the_callback, a, &err); \ERRCHECK \free(query); free(err);}//sample usage:array_w_sizeuntrustworthy;query_to_array(&untrustworthy,"select * from people where age > %i",30);

The trouble comes in when we have mixed numeric and string data. Implementing something to handle a case of mixed numeric and text data took me about page or two in the previously mentioned Apophenia library.

Nonetheless, let us delight in how the given snippets of code,

along with the two SQLite files themselves and a tweak to the objects line of the makefile, are enough to

provide full SQL database functionality to your program.

libxml and cURL

The cURL library is a C library that handles a long list of Internet protocols, including HTTP, HTTPS, POP3, Telnet, SCP, and of course Gopher. If you need to talk to a server, you can probably use libcURL to do it. As you will see in the following example, the library provides an easy interface that requires only that you specify a few variables, and then run the connection.

While we’re on the Internet, where markup languages like XML and HTML are so common, it makes sense to introduce libxml2 at the same time.

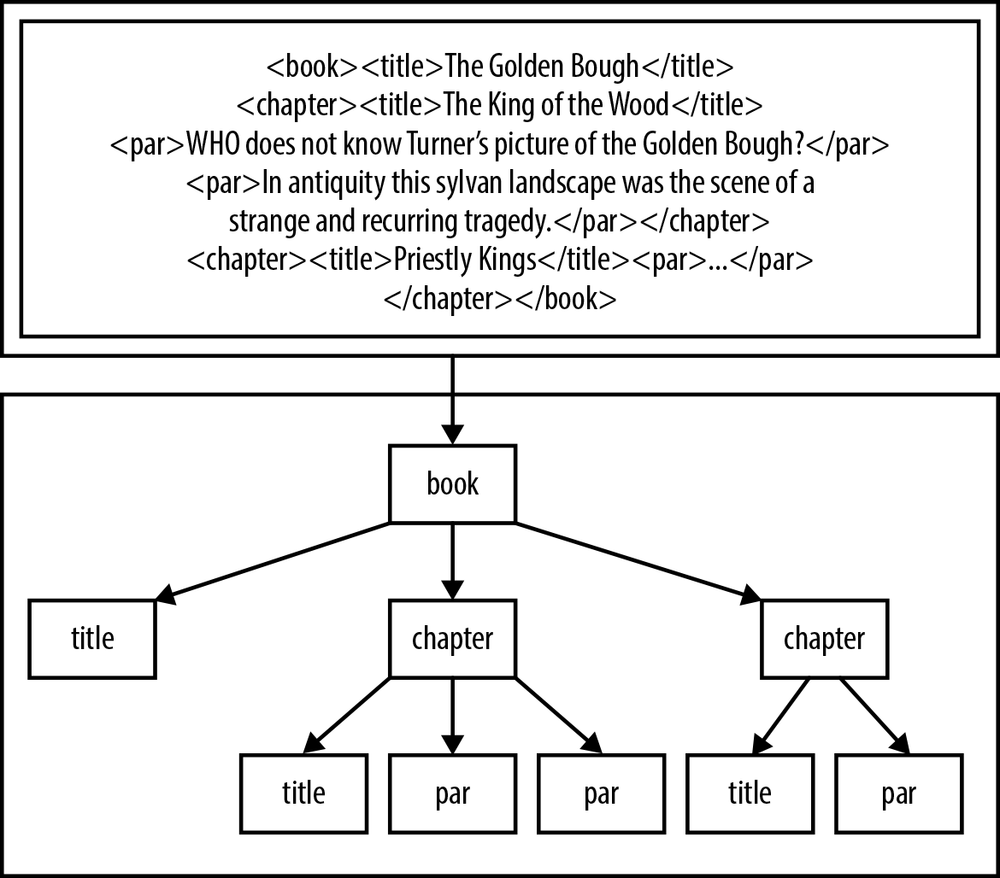

Extensible Markup Language (XML) is used to describe the formatting

for plain text files, but it is really the definition of a tree structure.

The first half of Figure 12-1 is a typical barely readable

slurry of XML data; the second half displays the tree structure formed by

the text. Handling a well-tagged tree is a relatively easy affair: we

could start at the root node (via xmlDocGetRootElement) and do a recursive

traversal to check all elements, or we could get all elements with the tag

par, or we could get all elements with the tag

title that are children of the second chapter, and so

on. In the following sample code, //item/title indicates all title elements whose parent is an item, anywhere in the tree.

libxml2 therefore speaks the language of tagged trees, with its focal objects being representations of the document, nodes, and lists of nodes.

Example 12-6 presents a full example. I documented it via Doxygen (see Interweaving Documentation), which is why it looks so long, but the code explains itself. Again, if you’re in the habit of skipping long blocks of code, do try it out and see if it’s readable. If you have Doxygen on hand, you can try generating the documentation and viewing it in your browser.

/** \fileA program to read in the NYT's headline feed and produce a simpleHTML page from the headlines. */#include <stdio.h>#include <curl/curl.h>#include <libxml2/libxml/xpath.h>#include "stopif.h"/** \mainpageThe front page of the Grey Lady's web site is as gaudy as can be, includingseveral headlines and sections trying to get your attention, various formattingschemes, and even photographs--in <em>color</em>.This program reads in the NYT Headlines RSS feed, and writes a simple list inplain HTML. You can then click through to the headline that modestly piquesyour attention.For notes on compilation, see the \ref compilation page.*//** \page compilation Compiling the programSave the following code to \c makefile.Notice that cURL has a program, \c curl-config, that behaves like \c pkg-config,but is cURL-specific.\codeCFLAGS =-g -Wall -O3 `curl-config --cflags` -I/usr/include/libxml2LDLIBS=`curl-config --libs ` -lxml2 -lpthreadCC=c99nyt_feed:\endcodeHaving saved your makefile, use <tt>make nyt_feed</tt> to compile.Of course, you have to have the development packages for libcurl and libxml2installed for this to work.*///These have in-line Doxygen documentation. The < points to the prior text//being documented.char*rss_url="http://rss.nytimes.com/services/xml/rss/nyt/HomePage.xml";/**< The URL for an NYT RSS feed. */char*rssfile="nytimes_feeds.rss";/**< A local file to write the RSS to.*/char*outfile="now.html";/**< The output file to open in your browser.*//** Print a list of headlines in HTML format to the outfile, which is overwritten.\param urls The list of urls. This should have been tested for non-NULLness\param titles The list of titles, also pre-tested to be non-NULL. If the lengthof the \c urls list or the \c titles list is \c NULL, this will crash.*/voidprint_to_html(xmlXPathObjectPtrurls,xmlXPathObjectPtrtitles){FILE*f=fopen(outfile,"w");for(inti=0;i<titles->nodesetval->nodeNr;i++)fprintf(f,"<a href=\"%s\">%s</a><br>\n",xmlNodeGetContent(urls->nodesetval->nodeTab[i]),xmlNodeGetContent(titles->nodesetval->nodeTab[i]));fclose(f);}/** Parse an RSS feed on the hard drive. This will parse the XML, then findall nodes matching the XPath for the title elements and all nodes matchingthe XPath for the links. Then, it will write those to the outfile.\param infile The RSS file in.*/intparse(charconst*infile){constxmlChar*titlepath=(xmlChar*)"//item/title";constxmlChar*linkpath=(xmlChar*)"//item/link";xmlDocPtrdoc=xmlParseFile(infile);Stopif(!doc,return-1,"Error: unable to parse file\"%s\"\n",infile);xmlXPathContextPtrcontext=xmlXPathNewContext(doc);Stopif(!context,return-2,"Error: unable to create new XPath context\n");xmlXPathObjectPtrtitles=xmlXPathEvalExpression(titlepath,context);xmlXPathObjectPtrurls=xmlXPathEvalExpression(linkpath,context);Stopif(!titles||!urls,return-3,"either the Xpath '//item/title' ""or '//item/link' failed.");print_to_html(urls,titles);xmlXPathFreeObject(titles);xmlXPathFreeObject(urls);xmlXPathFreeContext(context);xmlFreeDoc(doc);return0;}/** Use cURL's easy interface to download the current RSS feed.\param url The URL of the NY Times RSS feed. Any of the ones listed at\url http://www.nytimes.com/services/xml/rss/nyt/ should work.\param outfile The headline file to write to your hard drive. First savethe RSS feed to this location, then overwrite it with the short list of links.\return 1==OK, 0==failure.*/intget_rss(charconst*url,charconst*outfile){FILE*feedfile=fopen(outfile,"w");if(!feedfile)return-1;CURL*curl=curl_easy_init();if(!curl)return-1;curl_easy_setopt(curl,CURLOPT_URL,url);curl_easy_setopt(curl,CURLOPT_WRITEDATA,feedfile);CURLcoderes=curl_easy_perform(curl);if(res)return-1;curl_easy_cleanup(curl);fclose(feedfile);return0;}intmain(void){Stopif(get_rss(rss_url,rssfile),return1,"failed to download %s to %s.\n",rss_url,rssfile);parse(rssfile);printf("Wrote headlines to %s. Have a look at it in your browser.\n",outfile);}

[21] The standard requires a <threads.h> header that defines thread_local, so you don’t need the annoying underscore-capital combination (much like <bool.h> defines bool=_Bool). But this header isn’t yet implemented in any standard libraries I could find.