Chapter 10. Better Structures

Twenty-nine different attributes and only seven that you like.

—The Strokes, “You Only Live Once”

This chapter is about functions that take structured inputs, and just how far they can take us.

We start by covering three bits of syntax introduced to C in the ISO C99 standard: compound literals, variable-length macros, and designated initializers. The chapter is to a great extent an exploration of all the things that combinations of these elements can do for us.

With just compound literals, we can more easily send lists to a function. Then, a variable-length macro lets us hide the compound literal syntax from the user, leaving us with a function that can take a list of arbitrary length:

f(1, 2)orf(1, 2, 3, 4)would be equally valid.We could do similar tricks to implement the

foreachkeyword as seen in many other languages, or vectorize a one-input function so that it operates on several inputs.Designated initializers make working with structs much easier, to the point that I’ve almost entirely stopped using the old method. Instead of illegible and error-prone junk like

person_struct p = {"Joe", 22, 75, 20}, we can write self-documenting declarations such asperson_struct p = {.name="Joe", .age=22,.weight_kg=75,.education_years=20}.Now that initializing a struct doesn’t hurt, returning a struct from a function is also painless and can go far to clarify our function interfaces.

Sending structs to functions also becomes a more viable option. By wrapping everything in another variable-length macro, we can now write functions that take a variable number of named arguments, and even assign default values to those the function user doesn’t specify.

The remainder of the chapter gives some examples of situations where input and output structs can be used to make life easier, including when dealing with function interfaces based on void pointers, and when saddled with legacy code with a horrendous interface that needs to be wrapped into something usable.

Compound Literals

You can send a literal value into a function easily enough: given

the declaration double a_value, C has

no problem understanding f(a_value).

But if you want to send a list of elements—a compound literal value

like {20.38, a_value, 9.8}—then there’s

a syntactic caveat: you have to put a type-cast before the compound

literal, or else the parser will get confused. The list now looks like

(double[]) {20.38, a_value, 9.8}, and

the call looks like this:

f((double[]) {20.38, a_value, 9.8});Compound literals are automatically allocated, meaning that you need

neither malloc nor free to use them. At the end of the

scope in which the compound literal appears, it just disappears.

Example 10-1 begins with a rather typical function,

sum, that takes in an array of double, and sums its

elements up to the first NaN (Not-a-Number, see Marking Exceptional Numeric Values with NaNs). If the input array has no NaNs, the results will be

a disaster; we’ll impose some safety below. The example’s main has two ways to call it: the traditional via a

temp variable and the compound literal.

#include <math.h> //NAN

#include <stdio.h>

double sum(double in[]){  double out=0;

for (int i=0; !isnan(in[i]); i++) out += in[i];

return out;

}

int main(){

double list[] = {1.1, 2.2, 3.3, NAN};

double out=0;

for (int i=0; !isnan(in[i]); i++) out += in[i];

return out;

}

int main(){

double list[] = {1.1, 2.2, 3.3, NAN};  printf("sum: %g\n", sum(list));

printf("sum: %g\n", sum((double[]){1.1, 2.2, 3.3, NAN}));

printf("sum: %g\n", sum(list));

printf("sum: %g\n", sum((double[]){1.1, 2.2, 3.3, NAN}));  }

}

This unremarkable function will add the elements of the input array, until it reaches the first NaN marker.

This is a typical use of a function that takes in an array, where we declare the list via a throwaway variable on one line, and then send it to the function on the next.

Here, we do away with the intermediate variable and use a compound literal to create an array and send it directly to the function.

There’s the simplest use of compound literals; the rest of this chapter will make use of them to all sorts of benefits. Meanwhile, does the code on your hard drive use any quick throwaway lists whose use could be streamlined by a compound literal?

Note

This form is setting up an array, not a pointer to an array, so

you’ll be using the (double[]) type,

not (double*).

Initialization via Compound Literals

Let me delve into a hairsplitting distinction, which might give you a more solid idea of what compound literals are doing.

You are probably used to declaring arrays via a form like:

doublelist[]={1.1,2.2,3.3,NAN};

Here we have allocated a named array, list. If you called sizeof(list), you would get back whatever

4 * sizeof(double) is on your

machine. That is, list

is the array.

You could also perform the declaration via a compound literal,

which you can identify by the (double[]) type cast:

double*list=(double[]){1.1,2.2,3.3,NAN};

Here, the system first generated an anonymous list, put it into

the function’s memory frame, and then it declared a pointer, list, pointing to the anonymous list. So

list is an

alias, and sizeof(list) will equal sizeof(double*). Example 8-2

demonstrates this.

Variadic Macros

I broadly consider variable-length functions in C to be broken (more

in Flexible Function Inputs). But variable-length macro arguments are

easy. The keyword is __VA_ARGS__, and

it expands to whatever set of elements were given.

In Example 10-2, I revisit Example 2-5, a customized variant of printf that prints a message if an assertion

fails.

#include <stdio.h>#include <stdlib.h>//abort/** Set this to \c 's' to stop the program on an error.Otherwise, functions return a value on failure.*/charerror_mode;/** To where should I write errors? If this is \c NULL, write to \c stderr. */FILE*error_log;#define Stopif(assertion, error_action, ...) do { \if (assertion){ \fprintf(error_log ? error_log : stderr, __VA_ARGS__); \fprintf(error_log ? error_log : stderr, "\n"); \if (error_mode=='s') abort(); \else {error_action;} \} } while(0)

//sample usage:Stopif(x<0||x>1,return-1,"x has value %g, ""but it should be between zero and one.",x);

You can probably guess how the ellipsis (...) and __VA_ARGS__ work: whatever the user puts down in

place of the ellipsis gets plugged in at the __VA_ARGS__ mark.

As a demonstration of just how much variable-length macros can do

for us, Example 10-3 rewrites the syntax of for loops. Everything after the second

argument—regardless of how many commas are scattered about—will be read as

the ... argument and pasted in to the

__VA_ARGS__ marker.

for loop (varad.c)#include <stdio.h>#define forloop(i, loopmax, ...) for(int i=0; i< loopmax; i++) \{__VA_ARGS__}intmain(){intsum=0;forloop(i,10,sum+=i;printf("sum to %i: %i\n",i,sum);)}

I wouldn’t actually use Example 10-3 in real-world code, but chunks of code that are largely repetitive but for a minor difference across repetitions happen often enough, and it sometimes makes sense to use variable-length macros to eliminate the redundancy.

Safely Terminated Lists

Compound literals and variadic macros are the cutest couple, because we can now use macros to build lists and structures. We’ll get to the structure building shortly; let’s start with lists.

A few pages ago, you saw the function that took in a list and summed

until the first NaN. When using this function, you don’t need to know the

length of the input array, but you do need to make sure that there’s a NaN

marker at the end; if there isn’t, you’re in for a segfault. We could

guarantee that there is a NaN marker at the end of the list by calling

sum using a variadic macro, as in Example 10-4.

#include <math.h> //NAN

#include <stdio.h>

double sum_array(double in[]){  double out=0;

for (int i=0; !isnan(in[i]); i++) out += in[i];

return out;

}

#define sum(...) sum_array((double[]){__VA_ARGS__, NAN})

double out=0;

for (int i=0; !isnan(in[i]); i++) out += in[i];

return out;

}

#define sum(...) sum_array((double[]){__VA_ARGS__, NAN})  int main(){

double two_and_two = sum(2, 2);

int main(){

double two_and_two = sum(2, 2);  printf("2+2 = %g\n", two_and_two);

printf("(2+2)*3 = %g\n", sum(two_and_two, two_and_two, two_and_two));

printf("sum(asst) = %g\n", sum(3.1415, two_and_two, 3, 8, 98.4));

}

printf("2+2 = %g\n", two_and_two);

printf("(2+2)*3 = %g\n", sum(two_and_two, two_and_two, two_and_two));

printf("sum(asst) = %g\n", sum(3.1415, two_and_two, 3, 8, 98.4));

}

The name is changed, but this is otherwise the sum-an-array function from before.

This line is where the action is: the variadic macro dumps its inputs into a compound literal. So the macro takes in a loose list of

doubles but sends to the function a single list, which is guaranteed to end inNAN.

Now,

maincan send tosumloose lists of numbers of any length, and it can let the macro worry about appending the terminalNAN.

Now that’s a stylish function. It takes in as many inputs as you have, and you don’t have to pack them into an array beforehand, because the macro uses a compound literal to do it for you.

In fact, the macro version only works with loose numbers, not with

anything you’ve already set up as an array. If you already have an

array—and if you can guarantee the NAN

at the end—then call sum_array

directly.

Foreach

Earlier, you saw that you can use a compound literal anywhere you would put an array or structure. For example, here is an array of strings declared via a compound literal:

char **strings = (char*[]){"Yarn", "twine"};Now let’s put that in a for loop.

The first element of the loop declares the array of strings, so we can use

the preceding line. Then, we step through until we get to the NULL marker at the end. For additional

comprehensibility, I’ll typedef a

string type:

#include <stdio.h>

typedef char* string;

int main(){

string str = "thread";

for (string *list = (string[]){"yarn", str, "rope", NULL};

*list; list++)

printf("%s\n", *list);

}It’s still noisy, so let’s hide all the syntactic noise in a macro.

Then main is as clean as can be:

#include <stdio.h> //I'll do it without the typedef this time.

#define Foreach_string(iterator, ...)\

for (char **iterator = (char*[]){__VA_ARGS__, NULL}; *iterator; iterator++)int main(){

char *str = "thread";

Foreach_string(i, "yarn", str, "rope"){

printf("%s\n", *i);

}

}Vectorize a Function

The free function takes exactly

one argument, so we often have a long cleanup at the end of a function of

the form:

free(ptr1); free(ptr2); free(ptr3); free(ptr4);

How annoying! No self-respecting LISPer would ever allow such

redundancy to stand, but would write a vectorized free function that would allow:

free_all(ptr1,ptr2,ptr3,ptr4);

If you’ve read the chapter to this point, then the following

sentence will make complete sense to you: we can write a variadic macro

that generates an array (ended by a stopper) via compound literal, then

runs a for loop that applies the

function to each element of the array. Example 10-5 adds

it all up.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h> //malloc, free

#define Fn_apply(type, fn, ...) { \  void *stopper_for_apply = (int[]){0}; \

void *stopper_for_apply = (int[]){0}; \  type **list_for_apply = (type*[]){__VA_ARGS__, stopper_for_apply}; \

for (int i=0; list_for_apply[i] != stopper_for_apply; i++) \

fn(list_for_apply[i]); \

}

#define Free_all(...) Fn_apply(void, free, __VA_ARGS__);

int main(){

double *x= malloc(10);

double *y= malloc(100);

double *z= malloc(1000);

Free_all(x, y, z);

}

type **list_for_apply = (type*[]){__VA_ARGS__, stopper_for_apply}; \

for (int i=0; list_for_apply[i] != stopper_for_apply; i++) \

fn(list_for_apply[i]); \

}

#define Free_all(...) Fn_apply(void, free, __VA_ARGS__);

int main(){

double *x= malloc(10);

double *y= malloc(100);

double *z= malloc(1000);

Free_all(x, y, z);

}

For added safety, the macro takes in a type name. I put it before the function name, because the type-then-name ordering is reminiscent of a function declaration.

We need a stopper that we can guarantee won’t match any in-use pointers, including any

NULLpointers, so we use the compound literal form to allocate an array holding a single integer and point to that. Notice how the stopping condition of theforloop looks at the pointers themselves, not what they are pointing to.

Now that the machinery is in place, we can wrap this vectorizing macro around anything that takes in a pointer. For the GSL, you could define:

#define Gsl_vector_free_all(...) \ Fn_apply(gsl_vector, gsl_vector_free, __VA_ARGS__); #define Gsl_matrix_free_all(...) \ Fn_apply(gsl_matrix, gsl_matrix_free, __VA_ARGS__);

We still get compile-time type-checking (unless we set the pointer

type to void), which ensures that the

macro inputs are a list of pointers of the same type. To take in a set of

heterogeneous elements, we need one more trick—designated initializers.

Designated Initializers

I’m going to define this term by example. Here is a short program

that prints a 3-by-3 grid to the screen, with a star in one spot. You get

to specify whether you want the star to be in the upper right, left

center, or wherever by setting up a direction_s structure.

The focus of Example 10-6 is in main, where we declare three of these structures

using designated initializers—i.e., we designate the name of each

structure element in the initializer.

#include <stdio.h>

typedef struct {

char *name;

int left, right, up, down;

} direction_s;

void this_row(direction_s d); //these functions are below

void draw_box(direction_s d);

int main(){

direction_s D = {.name="left", .left=1};  draw_box(D);

D = (direction_s) {"upper right", .up=1, .right=1};

draw_box(D);

D = (direction_s) {"upper right", .up=1, .right=1};  draw_box(D);

draw_box((direction_s){});

draw_box(D);

draw_box((direction_s){});  }

void this_row(direction_s d){

}

void this_row(direction_s d){  printf( d.left ? "*..\n"

: d.right ? "..*\n"

: ".*.\n");

}

void draw_box(direction_s d){

printf("%s:\n", (d.name ? d.name : "a box"));

d.up ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

(!d.up && !d.down) ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

d.down ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

printf("\n");

}

printf( d.left ? "*..\n"

: d.right ? "..*\n"

: ".*.\n");

}

void draw_box(direction_s d){

printf("%s:\n", (d.name ? d.name : "a box"));

d.up ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

(!d.up && !d.down) ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

d.down ? this_row(d) : printf("...\n");

printf("\n");

}

This is our first designated initializer. Because

.right,.up, and.downare not specified, they are initialized to zero.

It seems natural that the name goes first, so we can use it as the first initializer, with no label, without ambiguity.

This is the extreme case, where everything is initialized to zero.

Everything after this line is about printing the box to the screen, so there’s nothing novel after this point.

The old school method of filling structs was to memorize the order

of struct elements and initialize all of them without any labels, so the

upper right declaration without a label

would be:

direction_s upright = {NULL, 0, 1, 1, 0};This is illegible and makes people hate C. Outside of the rare situation where the order is truly natural and obvious, please consider the unlabeled form to be deprecated.

Did you notice that in the setup of the

upper rightstruct, I had designated elements out of order relative to the order in the structure declaration? Life is too short to remember the order of arbitrarily ordered sets—let the compiler sort ’em out.The elements not declared are initialized to zero. No elements are left undefined.

You can mix designated and not-designated initializers. In Example 10-6, it seemed natural enough that the name comes first (and that a string like

"upper right"isn’t an integer), so when the name isn’t explicitly tagged as such, the declaration is still legible. The rule is that the compiler picks up where it left off:typedef struct{ int one; double two, three, four; } n_s; n_s justone = {10, .three=8}; //10with no label gets dropped in the first slot:.one=10n_s threefour = {.two=8, 3, 4}; //By the pick up where you left off rule,3gets put in //the next slot after.two:.three=3and.four=4

I had introduced compound literals in terms of arrays, but being that structs are more or less arrays with named and oddly sized elements, you can use them for structs, too, as I did in the

upper rightandcenterstructs in the sample code. As before, you need to add a cast-like(typename)before the curly braces. The first example inmainis a direct declaration, and so doesn’t need a compound initializer syntax, while later assignments set up an anonymous struct via compound literal and then copy that anonymous struct toDor send it to a subfunction.

Note

Your Turn: Rewrite every struct declaration in all of your code to use designated initializers. I mean this. The old school way without markers for which initializer went where was terrible. Notice also that you can rewrite junk like

direction_s D; D.left = 1; D.right = 0; D.up = 1; D.down = 0;

with

direction_s D = {.left=1, .up=1};Initialize Arrays and Structs with Zeros

If you declare a variable inside a function, then C won’t zero it out automatically (which is perhaps odd for things called automatic variables). I’m guessing that the rationale here is a speed savings: when setting up the frame for a function, zeroing out bits is extra time spent, which could potentially add up if you call the function a million times and it’s 1985.

But here in the present, leaving a variable undefined is asking for trouble.

For simple numeric data, set it to zero on the line where you

declare the variable. For pointers, including strings, set it to NULL. That’s easy enough, as long as you remember (and a good compiler will warn you

if you risk using a variable before it is initialized).

For structs and arrays of constant size, I just showed you that if you use designated initializers but leave some elements blank, those blank elements get set to zero. You can therefore set the whole structure to zero by assigning a complete blank. Here’s a do-nothing program to demonstrate the idea:

typedef struct {

int la, de, da;

} ladeda_s;int main(){

ladeda_s emptystruct = {};

int ll[20] = {};

}Isn’t that easy and sweet?

Now for the sad part: let us say that you have a variable-length

array (i.e., one whose length is set by a runtime variable). The only way

to zero it out is via memset:

int main(){

int length=20;

int ll[length];

memset(ll, 0, 20*sizeof(int));

}This is bitter in exact proportion to the sweetness of initializing fixed-length arrays. So it goes.[15]

Note

Your Turn: Write yourself a macro to declare a variable-length array and set all of its elements to zero. You’ll need inputs listing the type, name, and size.

For arrays that are sparse but not entirely empty, you can use designated initializers:

//Equivalent to{0, 0, 1.1, 0, 0, 2.2, 0}:double list1[7] = {[2]=1.1, [5]=2.2} //A form for filling in from the end of an array. By the pick up //where you left off rule, this will become{0.1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1.1, 2.2}:int len=7; double list3[len] = {0.1, [len-2]=1.1, 2.2}

Typedefs Save the Day

Designated initializers give new life to structs, and the rest of this chapter is largely a reconsideration of what structs can do for us now that they don’t hurt so much to use.

But first, you’ve got to declare the format of your structs. Here’s a sample of the format I use:

typedef struct newstruct_s {

int a, b;

double c, d;

} newstruct_s;This declares a new type (newstruct_s) that happens to be a structure of

the given form (struct newstruct_s).

You’ll here and there find authors who come up with two different names

for the struct tag and the typedef, such as typedef struct _nst { ... } newstruct_s;. This

is unnecessary: struct tags have a separate namespace from other

identifiers (K&R 2nd ed. §A8.3 (p. 213); C99 & C11 §6.2.3(1)), so

there is never ambiguity to the compiler. I find that repeating the name

doesn’t produce any ambiguity for us humans either, and saves the trouble

of inventing another naming convention.

The POSIX standard reserves names ending in _t for future types that might one day be

added to the standard. Formally, the C standard only reserves int..._t and unit..._t, but each new standard slips in all

sorts of new types ending in _t via

optional headers. A lot of people don’t spend a second worrying about

potential name clashes their code will face when C22 comes out in a

decade, and use the _t ending freely.

In this book, I end struct names with _s.

You can declare a structure of this type in two ways:

newstruct_sns1; struct newstruct_sns2;

There are only a few reasons for why you would need the struct newstruct_s name instead of just newstruct_s:

If you’ve got a struct that includes one of its own kind as an element (such as how the

nextpointer of a linked list structure is to another linked list structure). For example:typedef struct newstruct_s { int a, b; double c, d; struct newstruct_s *next; } newstruct_s;The standard for C11 anonymous structs goes out of its way to require that you use the

struct newstruct_sform. This will come up in C, with fewer seams.Some people just kinda like using the

struct newstruct_sformat, which brings us to a note on style.

A Style Note

I was surprised to see that there are people in the world who

think that typedefs are obfuscatory. For example, from the Linux kernel

style file: “When you see a vps_t a;

in the source, what does it mean? In contrast, if it says struct virtual_container *a; you can actually

tell what a is.” The natural response

to this is that it is having a longer name—and even one ending in

container—that clarifies the code, not the word

struct hanging at the

beginning.

But this typedef aversion had to come from somewhere. Further research turned up several sources that advise using typedefs to define units. For example:

typedef double inches; typedef double meters;

inches length1; meters length2;

Now you have to look up what inches really is every time it is used

(unsigned int? double?), and it doesn’t even afford any error

protection. A hundred lines down, when you assign:

length1 = length2;

you have already forgotten about the clever type declaration, and the typical C compiler won’t flag this as an error. If you need to take care of units, attach them to the variable name, so the error will be evident:

double length1_inches, length2_meters; //100 lines later: length1_inches = length2_meters; //this line is self-evidently wrong.

It makes sense to use typedefs that are global and the internals of which should be known by the user as sparingly as you would any other global elements, because looking up their declaration is as much a distraction as looking up the declaration of a variable, so they can impose cognitive load at the same time that they impose structure.

That said, it’s hard to find a production library that doesn’t

rely heavily on typdeffed global structures, like the GSL’s gsl_vectors and gsl_matrixes; or GLib’s hashes, trees, and

plethora of other objects. Even the source code for Git, written by

Linus Torvalds to be the revision control system for the Linux kernel,

has a few carefully placed typedefed structures.

Also, the scope of a typedef is the same as the scope of any other declaration. That means that you can typedef things inside a single file and not worry about them cluttering up the namespace outside of that file, and you might even find reason to have typedefs inside of a single function. You might have noticed that most of the typedefs so far are local, meaning that the reader can look up the definition by scanning back a few lines, and when they are global (i.e., in a header to be included everywhere), they are somehow hidden in a wrapper, meaning that the reader never has to look up the definition at all. So we can write structs that do not impose cognitive load.

Return Multiple Items from a Function

A mathematical function doesn’t have to map to one dimension. For example, a function that maps to a 2D point (x, y) is nothing at all spectacular.

Python (among other languages) lets you return multiple return values using lists, like this:

#Given the standard paper size name, return its width, heightdefwidth_length(papertype):if(papertype=="A4"):return[210,297]if(papertype=="Letter"):return[216,279]if(papertype=="Legal"):return[216,356][a,b]=width_length("A4");("width=%i, height=%i"%(a,b))

In C, you can always return a struct, and thus as many subelements as desired. This is why I was praising the joys of having throwaway structs earlier: generating a function-specific struct is not a big deal.

Let’s face it: C is still going to be more verbose than languages that have a special syntax for returning lists. But as demonstrated in Example 10-7, it is not impossible to clearly express that the function is returning a value in ℝ2.

#include <stdio.h>#include <strings.h>//strcasecmp#include <math.h>//NaNtypedefstruct{doublewidth,height;}size_s;size_swidth_height(char*papertype){return!strcasecmp(papertype,"A4")?(size_s){.width=210,.height=297}:!strcasecmp(papertype,"Letter")?(size_s){.width=216,.height=279}:!strcasecmp(papertype,"Legal")?(size_s){.width=216,.height=356}:(size_s){.width=NAN,.height=NAN};}intmain(){size_sa4size=width_height("a4");printf("width= %g, height=%g\n",a4size.width,a4size.height);}

Note

The code sample uses the

condition?

iftrue :

else form, which is a single expression, and

so can appear after the return.

Notice how a sequence of these cascade neatly into a sequence of cases

(including that last catch-all else clause at the end). I like to format

this sort of thing into a nice little table; you can find people who

call this terrible style.

The alternative is to use pointers, which is common and not

considered bad form, but it certainly obfuscates what is input and what is

output, and makes the version with the extra typedef look stylistically great:

//Return height and width via pointer: void width_height(char *papertype, double *width, double *height); //or return width directly and height via pointer: double width_height(char *papertype, double *height);

Reporting Errors

[Goodliffe 2006] discusses the various means of returning an error code from a function and is somewhat pessimistic about the options.

In some cases, the value returned can have a specific semaphore value, like -1 for integers or NaN for floating-point numbers (but cases where the full range of the variable is valid are common enough).

You can set a global error flag, but in 2006, Goodliffe was unable to recommend using the C11

_Thread_localkeyword to allow multiple threads to allow the flag to work properly when running in parallel. Although a global-to-the-program error flag is typically unworkable, a small suite of functions that work closely together could conceivably be written with a_Thread_localfile-scope variable.The third option is to “return a compound data type (or tuple) containing both the return value and an error code. This is rather clumsy in the popular C-like languages and is seldom seen in them.”

To this point in the chapter, you have seen that there are many benefits to returning a struct, and modern C provides lots of facilities (typedefs, designated initalizers) that eliminate most of the clumsiness.

Note

Any time you are writing a new struct, consider adding an

error or status element. Whenever your new struct is

returned from a function, you’ll then have a built-in means of

communicating whether it is valid for use.

Example 10-8 turns a physics 101 equation into an error-checked function to answer the question: given that an ideal object of a given mass has been in freefall to Earth for a given number of seconds, what is its energy?

I tricked it up with a lot of macros, because I find that authors tend to be more comfortable writing error-handling macros in C than for most other problems, perhaps because nobody wants error-checking to overwhelm the central flow of the story.

#include <stdio.h> #include <math.h> //NaN, pow #define make_err_s(intype, shortname) \typedef struct { \ intype value; \ char const *error; \

} shortname##_err_s; make_err_s(double, double) make_err_s(int, int) make_err_s(char *, string) double_err_s free_fall_energy(double time, double mass){ double_err_s out = {}; //initialize to all zeros. out.error = time < 0 ? "negative time"

: mass < 0 ? "negative mass" : isnan(time) ? "NaN time" : isnan(mass) ? "NaN mass" : NULL; if (out.error) return out;

double velocity = 9.8*time; out.value = mass*pow(velocity, 2)/2.; return out; } #define Check_err(checkme, return_val) \

if (checkme.error) {fprintf(stderr, "error: %s\n", checkme.error); return return_val;} int main(){ double notime=0, fraction=0; double_err_s energy = free_fall_energy(1, 1);

Check_err(energy, 1); printf("Energy after one second: %g Joules\n", energy.value); energy = free_fall_energy(2, 1); Check_err(energy, 1); printf("Energy after two seconds: %g Joules\n", energy.value); energy = free_fall_energy(notime/fraction, 1); Check_err(energy, 1); printf("Energy after 0/0 seconds: %g Joules\n", energy.value); }

If you like the idea of returning a value/error tuple, then you’ll want one for every type. So I thought I’d really trick this up by writing a macro to make it easy to produce one tuple type for every base type. See the usage a few lines down, to generate

double_err_s,int_err_s, andstring_err_s. If you think this is one trick too many, then you don’t have to use it.

Why not let errors be a string instead of an integer? The error messages will typically be constant strings, so there is no messing about with memory management, and nobody needs to look up the translations for obscure enums. See Enums and Strings for discussion.

Another table of return values. This sort of thing is common in the input-checking preliminaries to a function. Notice that the

out.errorelement points to one of the literal strings listed. Because no strings get copied, nothing has to be allocated or freed. To clarify this further, I madeerrora pointer tochar const.

Or, use the

Stopifmacro from Error Checking:Stopif(out.error, return out, out.error).

Macros to check for errors on return are a common C idiom. Because the error is a string, the macro can print it to

stderr(or perhaps an error log) directly.

Usage is as expected. Authors often lament how easy it is for users to traipse past the error codes returned from their functions, and in that respect, putting the output value in a tuple is a good reminder that the output includes an error code that the user of the function should take into account.

Flexible Function Inputs

A variadic function is one that takes a

variable number of inputs. The most famous example is printf,

where both printf("Hi.") and printf("%f %f %i\n", first,

second, third) are valid, even though the first example

has one input and the second has four.

Simply put, C’s variadic functions provide exactly enough power to

implement printf, and nothing more. You

must have an initial fixed argument, and it’s more or less expected that

that first argument provides a catalog to the types of the subsequent

elements, or at least a count. In the preceding example, the first

argument ("%f %f %i\n") indicates that

the next two items are expected to be floating-point variables, and the

last an integer.

There is no type safety: if you pass an int like 1 when you thought you were passing a

float like 1.0, results are undefined.

If the function expects to have three elements passed in but you sent only

two, you’re likely to get a segfault. Because of issues like this, CERT, a

software security group, considers variadic functions to be a security

risk (Severity: high. Likelihood: probable).[16]

Earlier, you met the first way to provide some safety to variable-length function inputs: by writing a wrapper macro that appends a stopper to the end of a list, we can guarantee that the base function will not receive a never-ending list. The compound literal will also check the input types and fail to compile if you send in an input of the wrong type.

This section covers two more ways to implement variadic functions with some type-checking safety. The last method will let you name your arguments, which can also help to reduce your error rate. I concur with CERT in considering free-form variadic functions too risky, and use only the forms here for variadic functions in my own code.

The first safe format in this segment free-rides on the compiler’s

checking for printf, extending the

already-familiar form. The second format in this segment uses a variadic

macro to prep the inputs to use the designated initializer syntax in

function headers.

Declare Your Function as printf-Style

First, let’s go the traditional route, and use C89’s variadic function facilities. I mention this because you might be in a situation where macros somehow can’t be used. Such situations are typically social, not technical—there are few if any cases where a variadic function can’t be replaced by a variadic macro using one of the techniques discussed in this chapter.

To make the C89 variadic function safe, we’ll need an addition

from gcc, but widely adopted by other compilers: the __attribute__, which allows

for compiler-specific tricks.[17] It goes on the declaration line of a

variable, struct, or function (so if your function isn’t declared before

use, you’ll need to do so).

gcc and Clang will let you set an attribute to declare a function

to be in the style of printf, meaning

that the compiler will type-check and warn you should you have an

int or a double* in a slot reserved for a double.

Say that we want a version of system that will allow printf-style inputs. In Example 10-9, the system_w_printf function takes in

printf-style inputs, writes them to a string, and

sends them to the standard system

command. The function uses vasprintf,

the va_list-friendly analog to

asprintf. Both of these are

BSD/GNU-standard. If you need to stick to C99, replace them with the

snprintf analog vsnprintf (and so, #include <stdarg.h>).

The main function is a simple

sample usage: it takes the first input from the command line and runs

ls on it.

#define _GNU_SOURCE //cause stdio.h to include vasprintf #include <stdio.h> //printf, vasprintf #include <stdarg.h> //va_start, va_end #include <stdlib.h> //system, free #include <assert.h> int system_w_printf(char const *fmt, ...) __attribute__ ((format (printf,1,2)));int system_w_printf(char const *fmt, ...){ char *cmd; va_list argp; va_start(argp, fmt); vasprintf(&cmd, fmt, argp); va_end(argp); int out= system(cmd); free(cmd); return out; } int main(int argc, char **argv){ assert(argc == 2);

return system_w_printf("ls %s", argv[1]); }

Mark this as a

printf-like function where input one is the format specifier and the list of additional parameters starts at input two.

I confess: I’m being lazy here. Use the raw

assertmacro only to check intermediate values under the author’s control, not inputs sent in by the user. See Error Checking for a macro appropriate for input testing.

The one plus this has over the variadic macro is that it is

awkward getting a return value from a macro. However, the macro version

in Example 10-10 is shorter and easier, and if your

compiler type-checks the inputs to printf-family functions, then it’ll do so here

(without any gcc/Clang-specific attributes).

#define _GNU_SOURCE//cause stdio.h to include vasprintf#include <stdio.h>//printf, vasprintf#include <stdlib.h>//system#include <assert.h>#define System_w_printf(outval, ...) { \char *string_for_systemf; \asprintf(&string_for_systemf, __VA_ARGS__); \outval = system(string_for_systemf); \free(string_for_systemf); \}intmain(intargc,char**argv){assert(argc==2);intout;System_w_printf(out,"ls %s",argv[1]);returnout;}

Optional and Named Arguments

I’ve already shown you how you can send a list of identical arguments to a function more cleanly via compound literal plus variable-length macro. If you don’t remember, go read Safely Terminated Lists right now.

A struct is in many ways just like an array, but holding not-identical types, so it seems like we could apply the same routine: write a wrapper macro to clean and pack all the elements into a struct, then send the completed struct to the function. Example 10-11 makes it happen.

It puts together a function that takes in a variable number of named arguments. There are three parts to defining the function: the throwaway struct, which the user will never use by name (but that still has to clutter up the global space if the function is going to be global); the macro that inserts its arguments into a struct, which then gets passed to the base function; and the base function.

#include <stdio.h>

typedef struct {  double pressure, moles, temp;

} ideal_struct;

/** Find the volume (in cubic meters) via the ideal gas law: V =nRT/P

Inputs:

pressure in atmospheres (default 1)

moles of material (default 1)

temperature in Kelvins (default freezing = 273.15)

*/

#define ideal_pressure(...) ideal_pressure_base((ideal_struct){.pressure=1, \

double pressure, moles, temp;

} ideal_struct;

/** Find the volume (in cubic meters) via the ideal gas law: V =nRT/P

Inputs:

pressure in atmospheres (default 1)

moles of material (default 1)

temperature in Kelvins (default freezing = 273.15)

*/

#define ideal_pressure(...) ideal_pressure_base((ideal_struct){.pressure=1, \  .moles=1, .temp=273.15, __VA_ARGS__})

double ideal_pressure_base(ideal_struct in){

.moles=1, .temp=273.15, __VA_ARGS__})

double ideal_pressure_base(ideal_struct in){  return 8.314 * in.moles*in.temp/in.pressure;

}

int main(){

printf("volume given defaults: %g\n", ideal_pressure() );

printf("volume given boiling temp: %g\n", ideal_pressure(.temp=373.15) );

return 8.314 * in.moles*in.temp/in.pressure;

}

int main(){

printf("volume given defaults: %g\n", ideal_pressure() );

printf("volume given boiling temp: %g\n", ideal_pressure(.temp=373.15) );  printf("volume given two moles: %g\n", ideal_pressure(.moles=2) );

printf("volume given two boiling moles: %g\n",

ideal_pressure(.moles=2, .temp=373.15) );

}

printf("volume given two moles: %g\n", ideal_pressure(.moles=2) );

printf("volume given two boiling moles: %g\n",

ideal_pressure(.moles=2, .temp=373.15) );

}

First, we need to declare a struct holding the inputs to the function.

The input to the macro will be plugged into the definition of an anonymous struct, wherein the arguments the user puts in the parens will be used as designated initializers.

The function itself takes in an

ideal_struct, rather than the usual free list of inputs.

The user inputs a list of designated initializers, the ones not listed get given a default value, and then

ideal_pressure_basewill have an input structure with everything it needs.

Here’s how the function call (don’t tell the user, but it’s actually a macro) on the last line will expand:

ideal_pressure_base((ideal_struct){.pressure=1, .moles=1, .temp=273.15,

.moles=2, .temp=373.15})The rule is that if an item is initialized multiple times, then

the last initialization takes precedence. So .pressure is left at its default of one, while

the other two inputs are set to the user-specified value.

Warning

Clang flags the repeated initialization of moles and temp with a warning when using -Wall, because the compiler authors expect

that the double-initialization is more likely to be an error than a

deliberate choice of default values. Turn off this warning by adding

-Wno-initializer-overrides to your

compiler flags. gcc flags this as an error only if you ask for

-Wextra warnings; use -Wextra -Woverride-init if you make use of

this option.

Note

Your Turn: In this case, the throwaway struct might not be so throwaway, because it might make sense to run the formula in multiple directions:

pressure = 8.314 moles * temp/volume

moles = pressure *volume /(8.314 temp)

temp = pressure *volume /(8.314 moles)

Rewrite the struct to also have a volume element, and use the same struct to write the functions for these additional equations.

Then, use these functions to produce a unifying function that

takes in a struct with three of pressure, moles, temp, and volume (the fourth can be NAN or you can add a what_to_solve element to the struct) and

applies the right function to solve for the fourth.

Note

Now that arguments are optional, you can add a new argument six months from now without breaking every program that used your function in the meantime. You are free to start with a simple working function and build up additional features as needed. However, we should learn a lesson from the languages that had this power from day one: it is easy to get carried away and build functions with literally dozens of inputs, each handling only an odd case or two.

Polishing a Dull Function

To this point, the examples have focused on demonstrating simple constructs without too much getting in the way, but short examples can’t cover the techniques involved in integrating everything together to form a useful and robust program that solves real-world problems. So the examples from here on in are going to get longer and include more realistic considerations.

Example 10-12 is a dull and unpleasant function. For an amortized loan, the monthly payments are fixed, but the percentage of the loan that is going toward interest is much larger at the outset (when more of the loan is still owed), and diminishes to zero toward the end of the loan. The math is tedious (especially when we add the option to make extra principal payments every month or to sell off the loan early), and you would be forgiven for skipping the guts of the function. Our concern here is with the interface, which takes in 10 inputs in basically arbitrary order. Using this function to do any sort of financial inquiry would be painful and error-prone.

That is, amortize looks a lot

like many of the legacy functions floating around the C world. It is

punk rock only in the sense that it has complete disdain for its

audience. So in the style of glossy magazines everywhere, this segment

will spruce up this function with a good wrapper. If this were legacy

code, we wouldn’t be able to change the function’s interface (other

programs might depend on it), so on top of the procedure that the ideal

gas example used to generate named, optional inputs, we will need to add

a prep function to bridge between the macro output and the fixed legacy

function inputs.

#include <math.h>//pow.#include <stdio.h>#include "amortize.h"doubleamortize(doubleamt,doublerate,doubleinflation,intmonths,intselloff_month,doubleextra_payoff,intverbose,double*interest_pv,double*duration,double*monthly_payment){doubletotal_interest=0;*interest_pv=0;doublemrate=rate/1200;//The monthly rate is fixed, but the proportion going to interest changes.*monthly_payment=amt*mrate/(1-pow(1+mrate,-months))+extra_payoff;if(verbose)printf("Your total monthly payment: %g\n\n",*monthly_payment);intend_month=(selloff_month&&selloff_month<months)?selloff_month:months;if(verbose)printf("yr/mon\tPrinc.\t\tInt.\t| PV Princ.\tPV Int.\tRatio\n");intm;for(m=0;m<end_month&&amt>0;m++){doubleinterest_payment=amt*mrate;doubleprincipal_payment=*monthly_payment-interest_payment;if(amt<=0)principal_payment=interest_payment=0;amt-=principal_payment;doubledeflator=pow(1+inflation/100,-m/12.);*interest_pv+=interest_payment*deflator;total_interest+=interest_payment;if(verbose)printf("%i/%i\t%7.2f\t\t%7.2f\t| %7.2f\t%7.2f\t%7.2f\n",m/12,m-12*(m/12)+1,principal_payment,interest_payment,principal_payment*deflator,interest_payment*deflator,principal_payment/(principal_payment+interest_payment)*100);}*duration=m/12.;returntotal_interest;}

Example 10-13 and Example 10-14 set up a user-friendly interface to the function. Most of the header file is Doxygen-style documentation, because with so many inputs, it would be insane not to document them all, and because we now have to tell the user what the defaults will be, should the user omit an input.

double amortize(double amt, double rate, double inflation, int months,

int selloff_month, double extra_payoff, int verbose,

double *interest_pv, double *duration, double *monthly_payment);

typedef struct {

double amount, years, rate, selloff_year, extra_payoff, inflation;  int months, selloff_month;

_Bool show_table;

double interest, interest_pv, monthly_payment, years_to_payoff;

char *error;

} amortization_s;

/** Calculate the inflation-adjusted amount of interest you would pay

int months, selloff_month;

_Bool show_table;

double interest, interest_pv, monthly_payment, years_to_payoff;

char *error;

} amortization_s;

/** Calculate the inflation-adjusted amount of interest you would pay  over the life of an amortized loan, such as a mortgage.

\li \c amount The dollar value of the loan. No default--if unspecified,

print an error and return zeros.

\li \c months The number of months in the loan. Default: zero, but see years.

\li \c years If you do not specify months, you can specify the number of

years. E.g., 10.5=ten years, six months.

Default: 30 (a typical U.S. mortgage).

\li \c rate The interest rate of the loan, expressed in annual

percentage rate (APR). Default: 4.5 (i.e., 4.5%), which

is typical for the current (US 2012) housing market.

\li \c inflation The inflation rate as an annual percent, for calculating

the present value of money. Default: 0, meaning no

present-value adjustment. A rate of about 3 has been typical

for the last few decades in the US.

\li \c selloff_month At this month, the loan is paid off (e.g., you resell

the house). Default: zero (meaning no selloff).

\li \c selloff_year If selloff_month==0 and this is positive, the year of

selloff. Default: zero (meaning no selloff).

\li \c extra_payoff Additional monthly principal payment. Default: zero.

\li \c show_table If nonzero, display a table of payments. If zero, display

nothing (just return the total interest). Default: 1

All inputs but \c extra_payoff and \c inflation must be nonnegative.

\return an \c amortization_s structure, with all of the above values set as

per your input, plus:

\li \c interest Total cash paid in interest.

\li \c interest_pv Total interest paid, with present-value adjustment for inflation.

\li \c monthly_payment The fixed monthly payment (for a mortgage, taxes and

interest get added to this)

\li \c years_to_payoff Normally the duration or selloff date, but if you make early

payments, the loan is paid off sooner.

\li \c error If <tt>error != NULL</tt>, something went wrong and the results

are invalid.

*/

#define amortization(...) amortize_prep((amortization_s){.show_table=1, \

__VA_ARGS__})

over the life of an amortized loan, such as a mortgage.

\li \c amount The dollar value of the loan. No default--if unspecified,

print an error and return zeros.

\li \c months The number of months in the loan. Default: zero, but see years.

\li \c years If you do not specify months, you can specify the number of

years. E.g., 10.5=ten years, six months.

Default: 30 (a typical U.S. mortgage).

\li \c rate The interest rate of the loan, expressed in annual

percentage rate (APR). Default: 4.5 (i.e., 4.5%), which

is typical for the current (US 2012) housing market.

\li \c inflation The inflation rate as an annual percent, for calculating

the present value of money. Default: 0, meaning no

present-value adjustment. A rate of about 3 has been typical

for the last few decades in the US.

\li \c selloff_month At this month, the loan is paid off (e.g., you resell

the house). Default: zero (meaning no selloff).

\li \c selloff_year If selloff_month==0 and this is positive, the year of

selloff. Default: zero (meaning no selloff).

\li \c extra_payoff Additional monthly principal payment. Default: zero.

\li \c show_table If nonzero, display a table of payments. If zero, display

nothing (just return the total interest). Default: 1

All inputs but \c extra_payoff and \c inflation must be nonnegative.

\return an \c amortization_s structure, with all of the above values set as

per your input, plus:

\li \c interest Total cash paid in interest.

\li \c interest_pv Total interest paid, with present-value adjustment for inflation.

\li \c monthly_payment The fixed monthly payment (for a mortgage, taxes and

interest get added to this)

\li \c years_to_payoff Normally the duration or selloff date, but if you make early

payments, the loan is paid off sooner.

\li \c error If <tt>error != NULL</tt>, something went wrong and the results

are invalid.

*/

#define amortization(...) amortize_prep((amortization_s){.show_table=1, \

__VA_ARGS__})  amortization_s amortize_prep(amortization_s in);

amortization_s amortize_prep(amortization_s in);

The structure used by the macro to transfer data to the prep function. It has to be part of the same scope as the macro and prep function themselves. Some elements are input elements that are not in the

amortizefunction, but can make the user’s life easier; some elements are output elements to be filled.

The documentation, in Doxygen format. It’s a good thing when the documentation takes up most of the interface file. Notice how each input has a default listed.

This macro stuffs the user’s inputs—perhaps something like

amortization(.amount=2e6, .rate=3.0)—into a designated initializer for anamortization_s. We have to set the default toshow_tablehere, because without it, there’s no way to distinguish between a user who explicitly sets.show_table=0and a user who omits.show_tableentirely. So if we want a default that isn’t zero for a variable where the user could sensibly send in zero, we have to use this form.

The three ingredients to the named-argument setup are still apparent: a typedef for a struct, a macro that takes in named elements and fills the struct, and a function that takes in a single struct as input. However, the function being called is a prep function, wedged in between the macro and the base function, the declaration of which is here in the header. Its guts are in Example 10-14.

#include "stopif.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include "amortize.h"

amortization_s amortize_prep(amortization_s in){  Stopif(!in.amount || in.amount < 0 || in.rate < 0

Stopif(!in.amount || in.amount < 0 || in.rate < 0  || in.months < 0 || in.years < 0 || in.selloff_month < 0

|| in.selloff_year < 0,

return (amortization_s){.error="Invalid input"},

"Invalid input. Returning zeros.");

int months = in.months;

if (!months){

if (in.years) months = in.years * 12;

else months = 12 * 30; //home loan

}

int selloff_month = in.selloff_month;

if (!selloff_month && in.selloff_year)

selloff_month = in.selloff_year * 12;

amortization_s out = in;

out.rate = in.rate ? in.rate : 4.5;

|| in.months < 0 || in.years < 0 || in.selloff_month < 0

|| in.selloff_year < 0,

return (amortization_s){.error="Invalid input"},

"Invalid input. Returning zeros.");

int months = in.months;

if (!months){

if (in.years) months = in.years * 12;

else months = 12 * 30; //home loan

}

int selloff_month = in.selloff_month;

if (!selloff_month && in.selloff_year)

selloff_month = in.selloff_year * 12;

amortization_s out = in;

out.rate = in.rate ? in.rate : 4.5;  out.interest = amortize(in.amount, out.rate, in.inflation,

months, selloff_month, in.extra_payoff, in.show_table,

&(out.interest_pv), &(out.years_to_payoff), &(out.monthly_payment));

return out;

}

out.interest = amortize(in.amount, out.rate, in.inflation,

months, selloff_month, in.extra_payoff, in.show_table,

&(out.interest_pv), &(out.years_to_payoff), &(out.monthly_payment));

return out;

}

This is the prep function that

amortizeshould have had: it sets nontrivial, intelligent defaults, and checks for an input errors. Now it’s OK thatamortizegoes straight to business, because all the introductory work happened here.

See Error Checking for discussion of the

Stopifmacro. As per the discussion there, the check on this line is more to prevent segfaults and check sanity than to allow automated testing of error conditions.

Because it’s a simple constant, we could also have set the rate in the

amortizationmacro, along with the default forshow_table. You’ve got options.

The immediate purpose of the prep function is to take in a single

struct and call the amortize function

with the struct’s elements, because we can’t change the interface to

amortize directly. But now that we

have a function dedicated to preparing function inputs, we can really do

error-checking and default-setting right. For example, we can now give

users the option of specifying time periods in months or years, and can

use this prep function to throw errors if the inputs are out of bounds

or insensible.

Defaults are especially important for a function like this one, by the way, because most of us don’t know (and have little interest in finding out) what a reasonable inflation rate is. If a computer can offer the user subject-matter knowledge that he or she might not have, and can do so with an unobtrusive default that can be overridden with no effort, then rare will be the user who is ungrateful.

The amortize function returns

several different values. As per Return Multiple Items from a Function, putting

them all in a single struct is a nice alternative to how amortize returns one value and then puts the

rest into pointers sent as input. Also, to make the trick about

designated initializers via variadic macros work, we had to have another

structure intermediating; why not combine the two structures? The result

is an output structure that retains all of the input

specifications.

After all that interface work, we now have a well-documented,

easy-to-use, error-checked function, and the program in Example 10-15 can run lots of what-if scenarios with no hassle.

It uses amortize.c and

amort_interface.c from earlier, and the former file

uses pow from the math library, so

your makefile will look like:

P=amort_use objects=amort_interface.o amortize.o CFLAGS=-g -Wall -O3 #the usual LDLIBS=-lm CC=c99 $(P):$(objects)

#include <stdio.h>

#include "amortize.h"

int main(){

printf("A typical loan:\n");

amortization_s nopayments = amortization(.amount=200000, .inflation=3);

printf("You flushed real $%g down the toilet, or $%g in present value.\n",

nopayments.interest, nopayments.interest_pv);

amortization_s a_hundred = amortization(.amount=200000, .inflation=3,

.show_table=0, .extra_payoff=100);

printf("Paying an extra $100/month, you lose only $%g (PV), "

"and the loan is paid off in %g years.\n",

a_hundred.interest_pv, a_hundred.years_to_payoff);

printf("If you sell off in ten years, you pay $%g in interest (PV).\n",

amortization(.amount=200000, .inflation=3,

.show_table=0, .selloff_year=10).interest_pv);  }

}

The

amortizationfunction returns a struct, and in the first two uses, the struct was given a name, and the named struct’s elements were used. But if you don’t need the intermediate named variable, don’t bother. This line pulls the one element of the struct that we need from the function. If the function returned a piece ofmalloced memory, you couldn’t do this, because you’d need a name to send to the memory-freeing function, but notice how this entire chapter is about passing structs, not pointers-to-structs.

There are a lot of lines of code wrapping the original function, but the boilerplate struct and macros to set up named arguments are only a few of them. The rest is documentation and intelligent input-handling that is well worth adding. As a whole, we’ve taken a function with an almost unusable interface and made it as user-friendly as an amortization calculator can be.

The Void Pointer and the Structures It Points To

This segment is about the implementation of generic procedures and generic structures. One example in this segment will apply some function to every file in a directory hierarchy, letting the user print the filenames to screen, search for a string, or whatever else comes to mind. Another example will use GLib’s hash structure to record a count of every character encountered in a file, which means associating a Unicode character key with an integer value. Of course, GLib provides a hash structure that can take any type of key and any type of value, so the Unicode character counter is an application of the general container.

All this versatility is thanks to the void pointer, which can point to anything. The hash function and directory processing routine are wholly indifferent to what is being pointed to and simply pass the values through as needed. Type safety becomes our responsibility, but structs will help us retain type safety and will make it easier to write and work with generic procedures.

Functions with Generic Inputs

A callback function is a function that is passed to another function for the other function’s use. Next, I’ll present a generic procedure to recurse through a directory and do something to every file found there; the callback is the function handed to the directory-traversal procedure for it to apply to each file.

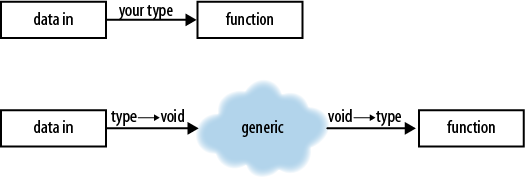

The problem is depicted in Figure 10-1. With a

direct function call, the compiler knows the type of your data, it knows

the type the function requires, and if they don’t match the compiler

will tell you. But a generic procedure should not dictate the format for

the function or the data the function uses. Easy Threading with Pthreads

makes use of pthread_create, which

(omitting the irrelevant parts) might be declared with a form

like:

typedef void *(*void_ptr_to_void_ptr)(void *in); int pthread_create(..., void *ptr, void_ptr_to_void_ptr fn);

If we make a call like pthread_create(...,

indata,

myfunc), then the type information for

indata has been lost, as it was cast to a void

pointer. We can expect that somewhere in pthread_create, a call of the form

myfunc(indata) will occur. If

indata is a double*, and myfunc

takes a char*, then this is a

disaster the compiler can’t prevent.

Example 10-16 is the header file for an

implementation of the function that applies functions to every directory

and file within a given directory. It includes Doxygen documentation of

what the process_dir function is

expected to do. As it should be, the documentation is roughly as long as

the code will be.

struct filestruct;

typedef void (*level_fn)(struct filestruct path);

typedef struct filestruct{

char *name, *fullname;

level_fn directory_action, file_action;

int depth, error;

void *data;

} filestruct;  /** I get the contents of the given directory, run \c file_action on each

file, and for each directory run \c dir_action and recurse into the directory.

Note that this makes the traversal `depth first'.

Your functions will take in a \c filestruct, qv. Note that there is an \c error

element, which you can set to one to indicate an error.

Inputs are designated initializers, and may include:

\li \c .name The current file or directory name

\li \c .fullname The path of the current file or directory

\li \c .directory_action A function that takes in a \c filestruct.

I will call it with an appropriately-set \c filestruct

for every directory (just before the files in the directory

are processed).

\li \c .file_action Like the \c directory_action, but the function

I will call for every non-directory file.

\li \c .data A void pointer to be passed in to your functions.

\return 0=OK, otherwise the count of directories that failed + errors thrown

by your scripts.

Your functions may change the \c data element of the \c filestruct.

Sample usage:

\code

void dirp(filestruct in){ printf("Directory: <%s>\n", in.name); }

void filep(filestruct in){ printf("File: %s\n", in.name); }

//list files, but not directories, in current dir:

process_dir(.file_action=filep);

//show everything in my home directory:

process_dir(.name="/home/b", .file_action=filep, .directory_action=dirp);

\endcode

*/

#define process_dir(...) process_dir_r((filestruct){__VA_ARGS__})

/** I get the contents of the given directory, run \c file_action on each

file, and for each directory run \c dir_action and recurse into the directory.

Note that this makes the traversal `depth first'.

Your functions will take in a \c filestruct, qv. Note that there is an \c error

element, which you can set to one to indicate an error.

Inputs are designated initializers, and may include:

\li \c .name The current file or directory name

\li \c .fullname The path of the current file or directory

\li \c .directory_action A function that takes in a \c filestruct.

I will call it with an appropriately-set \c filestruct

for every directory (just before the files in the directory

are processed).

\li \c .file_action Like the \c directory_action, but the function

I will call for every non-directory file.

\li \c .data A void pointer to be passed in to your functions.

\return 0=OK, otherwise the count of directories that failed + errors thrown

by your scripts.

Your functions may change the \c data element of the \c filestruct.

Sample usage:

\code

void dirp(filestruct in){ printf("Directory: <%s>\n", in.name); }

void filep(filestruct in){ printf("File: %s\n", in.name); }

//list files, but not directories, in current dir:

process_dir(.file_action=filep);

//show everything in my home directory:

process_dir(.name="/home/b", .file_action=filep, .directory_action=dirp);

\endcode

*/

#define process_dir(...) process_dir_r((filestruct){__VA_ARGS__})  int process_dir_r(filestruct level);

int process_dir_r(filestruct level);

Here they are again: the three parts of a function that takes in named arguments. But even that trick aside, this struct will be essential to retaining type-safety when passing void pointers.

The macro that stuffs designated initializers from the user into a compound literal struct.

The function that takes in the struct built by the

process_dirmacro. Users won’t call it directly.

Comparing this with Figure 10-1, this header

already indicates a partial solution to the type-safety problem:

defining a definite type, the filestruct, and requiring the callback take in

a struct of that type. There’s still a void pointer buried at the end of

the struct. I could have left the void pointer outside of the struct, as

in:

typedef void (*level_fn)(struct filestruct path, void *indata);

But as long as we’re defining an ad hoc struct as a helper to the

process_dir function, we might as

well throw the void pointer in there. Further, now that we have a struct

associated with the process_dir

function, we can use it to implement the form where a macro turns

designated initializers into a function input, as per Optional and Named Arguments. Structs make everything easier.

Example 10-17 presents a use of process_dir—the portions before and after the

cloud of Figure 10-1. These callback functions are

simple, printing some spacing and the file/directory name. There

isn’t even any type-unsafety yet, because the input to the callback was

defined to be a certain type of struct.

Here’s a sample output, for a directory that has two files and a subdirectory named cfiles, holding another three files:

Treeforsample_dir:├cfiles└───┐▕c.c▕a.c▕b.c│a_file│another_file

#include <stdio.h>#include "process_dir.h"voidprint_dir(filestructin){for(inti=0;i<in.depth-1;i++)printf(" ");printf("├ %s\n",in.name);for(inti=0;i<in.depth-1;i++)printf(" ");printf("└───┐\n");}voidprint_file(filestructin){for(inti=0;i<in.depth;i++)printf(" ");printf("│ %s\n",in.name);}intmain(intargc,char**argv){char*start=(argc>1)?argv[1]:".";printf("Tree for %s:\n",start?start:"the current directory");process_dir(.name=start,.file_action=print_file,.directory_action=print_dir);}

As you can see, main hands the

print_dir and print_file functions to process_dir, and trusts that process_dir will call them at the right time

with the appropriate inputs.

The process_dir function itself

is in Example 10-18. Most of the work of the function is

absorbed in generating an up-to-date struct describing the file or

directory currently being handled. The given directory is opened, via

opendir. Then, each call to readdir will pull another entry from the

directory, which will describe one file, directory, link, or whatever

else in the given directory. The input filestruct is updated with the current entry’s

information. Depending on whether the directory entry describes a

directory or a file, the appropriate callback is called with the newly

prepared filestruct. If it’s a

directory, then the function is recursively called using the current

directory’s information.

file_action to every file found and directory_action to every directory found

(process_dir.c)#include "process_dir.h"

#include <dirent.h> //struct dirent

#include <stdlib.h> //free

int process_dir_r(filestruct level){

if (!level.fullname){

if (level.name) level.fullname=level.name;

else level.fullname=".";

}

int errct=0;

DIR *current=opendir(level.fullname);  if (!current) return 1;

struct dirent *entry;

while((entry=readdir(current))) {

if (entry->d_name[0]=='.') continue;

filestruct next_level = level;

if (!current) return 1;

struct dirent *entry;

while((entry=readdir(current))) {

if (entry->d_name[0]=='.') continue;

filestruct next_level = level;  next_level.name = entry->d_name;

asprintf(&next_level.fullname, "%s/%s", level.fullname, entry->d_name);

if (entry->d_type==DT_DIR){

next_level.depth ++;

if (level.directory_action) level.directory_action(next_level);

next_level.name = entry->d_name;

asprintf(&next_level.fullname, "%s/%s", level.fullname, entry->d_name);

if (entry->d_type==DT_DIR){

next_level.depth ++;

if (level.directory_action) level.directory_action(next_level);  errct+= process_dir_r(next_level);

}

else if (entry->d_type==DT_REG && level.file_action){

level.file_action(next_level);

errct+= process_dir_r(next_level);

}

else if (entry->d_type==DT_REG && level.file_action){

level.file_action(next_level);  errct+= next_level.error;

}

free(next_level.fullname);

errct+= next_level.error;

}

free(next_level.fullname);  }

closedir(current);

return errct;

}

}

closedir(current);

return errct;

}

The

opendir,readdir, andclosedirfunctions are POSIX-standard.

For each entry in the directory, make a new copy of the input

filestruct, then update it as appropriate.

Given the up-to-date

filestruct, call the per-directory function. Recurse into subdirectory.

Given the up-to-date

filestruct, call the per-file function.

The

filestructs that get made for each step are not pointers and are notmalloced, so they require no memory-management code. However,asprintfdoes implicitly allocatefullname, so that has to be freed to keep things clean.

The setup successfully implemented the appropriate encapsulation: the printing functions didn’t care about POSIX directory-handling, and process_dir.c knew nothing of what the input functions did. And the function-specific struct made the flow relatively seamless.

Generic Structures

Linked lists, hashes, trees, and other such data structures are applicable in all sorts of situations, so it makes sense that they would be provided with hooks for void pointers, and then you as a user would check types on the way in and on the way out.

This segment will present a typical textbook example: a character-frequency hash. A hash is a container that holds key/value pairs, with the intent of allowing users to quickly look up values using a key.

Before getting to the part where we process files in a directory, we need to customize the generic GLib hash to the form that the program will use, with a Unicode key and a value holding a single integer. Once this component (which is already a good example of dealing with callbacks) is in place, it will be easy to implement the callbacks for the file traversal part of the program.

As you will see, the equal_chars and printone functions are intended as callbacks

for use by functions associated with the hash, so the hash will send to

these callbacks two void pointers. Thus, the first lines of these

functions declare variables of the correct type, effectively casting the

void pointer input to a type.

Example 10-19 presents the header, showing what is for public use out of Example 10-20.

#include <glib.h>voidhash_a_character(gunicharuc,GHashTable*hash);voidprintone(void*key_in,void*val_in,void*xx);GHashTable*new_unicode_counting_hash();

#include "string_utilities.h"

#include "process_dir.h"

#include "unictr.h"

#include <glib.h>

#include <stdlib.h> //calloc, malloc

typedef struct {  int count;

} count_s;

void hash_a_character(gunichar uc, GHashTable *hash){

count_s *ct = g_hash_table_lookup(hash, &uc);

if (!ct){

ct = calloc(1, sizeof(count_s));

gunichar *newchar = malloc(sizeof(gunichar));

*newchar = uc;

g_hash_table_insert(hash, newchar, ct);

}

ct->count++;

}

void printone(void *key_in, void *val_in, void *ignored){

int count;

} count_s;

void hash_a_character(gunichar uc, GHashTable *hash){

count_s *ct = g_hash_table_lookup(hash, &uc);

if (!ct){

ct = calloc(1, sizeof(count_s));

gunichar *newchar = malloc(sizeof(gunichar));

*newchar = uc;

g_hash_table_insert(hash, newchar, ct);

}

ct->count++;

}

void printone(void *key_in, void *val_in, void *ignored){  gunichar const *key= key_in;

gunichar const *key= key_in;  count_s const *val= val_in;

char utf8[7];

count_s const *val= val_in;

char utf8[7];  utf8[g_unichar_to_utf8(*key, utf8)]='\0';

printf("%s\t%i\n", utf8, val->count);

}

static gboolean equal_chars(void const * a_in, void const * b_in){

utf8[g_unichar_to_utf8(*key, utf8)]='\0';

printf("%s\t%i\n", utf8, val->count);

}

static gboolean equal_chars(void const * a_in, void const * b_in){  const gunichar *a= a_in;

const gunichar *a= a_in;  const gunichar *b= b_in;

return (*a==*b);

}

GHashTable *new_unicode_counting_hash(){

return g_hash_table_new(g_str_hash, equal_chars);

}

const gunichar *b= b_in;

return (*a==*b);

}

GHashTable *new_unicode_counting_hash(){

return g_hash_table_new(g_str_hash, equal_chars);

}

Yes, this is a struct holding a single integer. One day, it might save your life.

This is going to be a callback for

g_hash_table_foreach, so it will take in void pointers for the key, value, and an optional void pointer that this function doesn’t use.

If a function takes in a void pointer, the first line needs to set up a variable with the correct type, thus casting the void pointer to something usable. Do not put this off to later lines—do it right at the top, where you can verify that you got the type cast correct.

Six

chars is enough to express any UTF-8 encoding of a Unicode character. Add another byte for the terminating'\0', and 7 bytes is enough to express any one-character string.

Because a hash’s keys and values can be any type, GLib asks that you provide the comparison function to determine whether two keys are equal. Later,

new_unicode_counting_hashwill send this function to the hash creation function.

Did I mention that the first line of a function that takes in a void pointer needs to assign the void pointer to a variable of the correct type? Once you do this, you’re back to type safety.

Now that we have a set of functions in support of a hash for

Unicode characters, Example 10-21 uses them, along with

process_dir from before, to count all

the characters in the UTF-8-readable files in a directory.

It uses the same process_dir

function defined earlier, so the generic procedure and its use should now be familiar to you. The callback to

process a single file, hash_a_file, takes in a

filestruct, but buried within that

filestruct is a void

pointer. The functions here use that void pointer to point to a

GLib hash structure. Thus, the first line of hash_a_file casts the void pointer to the

structure it points to, thus returning us to type safety.

Each component can be debugged in isolation, just knowing what

will get input and when. But you can follow the hash from component to

component, and verify that it gets sent to process_dir via the .data element of the input filestruct, then hash_a_file casts .data to a GHashTable again, then it gets sent to

hash_a_character, which will modify

it or add to it as you saw earlier. Then, g_hash_table_foreach uses the printone callback to

print each element in the hash.

#define _GNU_SOURCE //get stdio.h to define asprintf

#include "string_utilities.h" //string_from_file

#include "process_dir.h"

#include "unictr.h"

#include <glib.h>

#include <stdlib.h> //free

void hash_a_file(filestruct path){

GHashTable *hash = path.data;  char *sf = string_from_file(path.fullname);

if (!sf) return;

char *sf_copy = sf;

if (g_utf8_validate(sf, -1, NULL)){

for (gunichar uc; (uc = g_utf8_get_char(sf))!='\0';

char *sf = string_from_file(path.fullname);

if (!sf) return;

char *sf_copy = sf;

if (g_utf8_validate(sf, -1, NULL)){

for (gunichar uc; (uc = g_utf8_get_char(sf))!='\0';  sf = g_utf8_next_char(sf))

hash_a_character(uc, hash);

}

free(sf_copy);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

GHashTable *hash;

hash = new_unicode_counting_hash();

char *start=NULL;

if (argc>1) asprintf(&start, "%s", argv[1]);

printf("Hashing %s\n", start ? start: "the current directory");

process_dir(.name=start, .file_action=hash_a_file, .data=hash);

g_hash_table_foreach(hash, printone, NULL);

}

sf = g_utf8_next_char(sf))

hash_a_character(uc, hash);

}

free(sf_copy);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

GHashTable *hash;

hash = new_unicode_counting_hash();

char *start=NULL;

if (argc>1) asprintf(&start, "%s", argv[1]);

printf("Hashing %s\n", start ? start: "the current directory");

process_dir(.name=start, .file_action=hash_a_file, .data=hash);

g_hash_table_foreach(hash, printone, NULL);

}

Recall that the

filestructincludes a void pointer,data. So the first line of the function will of course declare a variable with the correct type for the input void pointer.

UTF-8 characters are variable-length, so you need a special function to get the current character or step to the next character in a string.