Chapter 8. Obstacles and Opportunity

There’s no C Foundation paying me to advocate the language, and this book is not a sales pitch dressed up as a tutorial, so I can write freely about C’s problems. The bits here are too valuable to be in the don’t-bother category under which so many of the items in the previous chapter fall, but they also come with cautions about the historic cruft that made sense at the time and is now just a mess.

C’s macro facilities are simple but still pack in a lot of little exceptions.

The usage of the

statickeyword is at this point painfully confusing, though in the end, it will give us a nice alternative to elaborate macros. Its complement in certain senses, theexternkeyword, also gives us enough rope with which to hang ourselves.The

constkeyword fits this chapter because it is too useful to not use, but it has oddities in its specification in the standard and in its implementation in common compilers.

Cultivate Robust and Flourishing Macros

Chapter 10 will present several options for making the user interface to your library friendlier and less error-inviting, and will rely heavily on macros to do it.

I read a lot of people who say that macros are themselves

invitations for errors and should be avoided, but those people don’t

advise that you shouldn’t use NULL,

isalpha, isfinite, assert, type-generic math like log, sin,

cos, pow, and so on, or any of the dozens of other

facilities defined by the GNU standard library via macros. Those are

well-written, robust macros that do what they should every time.

Macros perform text substitions (referred to as expansions under the presumption that the substituted text will be longer), and text substitutions require a different mindset from the usual functions, because the input text can interact with the text in the macro and other text in the source code. Macros are best used in cases where we want those interactions, and when we don’t we need to take care to prevent them.

Before getting to the rules for making macros robust, of which there

are three, let me distinguish between two types of macro. One type expands

to an expression, meaning that it makes sense to evaluate these macros,

print their values, or in the case of numeric results, use them in the

middle of an equation. The other type is a block of instructions, that

might appear after an if statement or

in a while loop. That said, here are

some rules:

Parens! It’s easy for expectations to be broken when a macro pastes text into place. Here’s an easy example:

#define double(x) 2*x Needs more parens.Now, the user tries

double(1+1)*8, and the macro expands it to2*1+1*8, equals 10, not 32. Parens make it work:#define double(x) (2*(x))

Now

(2*(1+1))*8is what it should be. The general rule is to put all inputs in parens unless you have a specific reason not to. If you have an expression-type macro, put the macro expansion itself in parens.

Avoid double usage. This textbook example is a little risky:

#define max(a, b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b))

If the user tries

int x=1, y=2; int m=max(x, y++), the expectation is thatmwill be 2 (the preincrement value ofy), and thenywill bump up to 3. But the macro expands to:m = ((x) > (y++) ? (x) : (y++))

which will evaluate

y++twice, causing a double increment where the user expected only a single, andm=3where the user expectedm=2.If you have a block-type macro, then you can declare a variable to take on the value of the input at the head of the block, and then use your copy of the input for the rest of the macro.

This rule is not adhered to as religiously as the parens rule—the

maxmacro often appears in the wild—so bear in mind as a macro user that side effects inside calls to unknown macros should be kept to a minimum.

Curly braces for blocks. Here’s a simple block macro:

#define doubleincrement(a, b) \ Needs curly braces. (a)++; \ (b)++;We can make it do the wrong thing by putting it after an

ifstatement:int x=1, y=0; if (x>y) doubleincrement(x, y);Adding some indentation to make the error obvious, this expands to:

int x=1, y=0; if (x>y) (x)++; (y)++;Another potential pitfall: what if your macro declares a variable

total, but the user defined atotalalready? Variables declared in the block can conflict with variables declared outside the block. Example 8-1 has the simple solution to both problems: put curly braces around your macro.Putting the whole macro in curly braces allows us to have an intermediate variable named

totalthat lives only inside the scope of the curly braces around the macro, and it therefore in no way interferes with thetotaldeclared inmain.Example 8-1. We can control the scope of variables with curly braces, just as with typical nonmacro code (curly.c)#include <stdio.h>#define sum(max, out) { \int total=0; \for (int i=0; i<= max; i++) \total += i; \out = total; \}intmain(){intout;inttotal=5;sum(5,out);printf("out= %i original total=%i\n",out,total);}But there is one small glitch remaining. This code:

#define doubleincrement(a, b) { \ (a)++; \ (b)++; \ } if (a>b) doubleincrement(a, b); else return 0;expands to this:

if (a>b) { (a)++; (b)++; }; else return 0;The extra semicolon just before the

elseconfuses the compiler. The common solution to this is to wrap the macro still further in a run-oncedo-whileloop:#define doubleincrement(a, b) do { \ (a)++; \ (b)++; \ } while(0); if (a>b) doubleincrement(a, b); else return 0;

Note

For gcc, Clang, and icc, use -E

to only run the preprocessor, printing the expanded version of

everything to stdout. Because that includes the expansion of #include <stdio.h> and other voluminous

boilerplate, I usually redirect the results to a file or to a pager,

with a form like gcc -E

mycode.c |less, and then search the results for the

macro expansion I’m trying to debug.

Using gcc -E curly.c, we see that

the preprocessor expands the sum macro

as shown next, and following the curly braces shows us that there’s no

chance that the total in the macro’s

scope will interfere with the total in

the main scope. So the code would print

total as 5:

int main(){

int out;

int total = 5;

{ int total=0; for (int i=0; i<= 5; i++) total += i; out = total; };

printf("out= %i total=%i\n", out, total);

}Warning

Limiting a macro’s scope with curly braces doesn’t protect us from

all name clashes. In the previous example, what would happen if we were

to write int out, i=5; sum(i,

out);?

That’s about it for macro caveats. The basic principle of keeping macros simple still makes sense, and you’ll find that macros in production code tend to be one-liners that prep the inputs in some way and then call a standard function to do the real work. The debugger and non-C systems that can’t parse macro definitions themselves don’t have access to your macro, so whatever you write should still have a way of being usable without the macros. Linkage with static and extern will have one suggestion for reducing the hassle when writing down simple functions.

Preprocessor Tricks

The token reserved for the preprocessor is the octothorp, #, and the preprocessor makes three entirely

different uses of it.

You know that a preprocessor directive like #define begins with a # at the head of the line. Whitespace before

the # is ignored (K&R 2nd ed.

§A12, p. 228), so here’s your first tip: you can put throwaway macros in

the middle of a function, just before they get used, and indent them to

flow with the function. According to the old school, putting the macro

right where it gets used is against the “correct” organization of a

program (which puts all macros at the head of the file), but having it

right there makes it easy to refer to and makes the throwaway nature of

the macro evident. The preprocessor knows next to nothing of where

functions begin and end, so the scope of a macro is from its occurrence

in the file to the end of the file.

The next use of the # is in a

macro: it turns input code into a string. Example 8-2

shows a program demonstrating a point about the use of sizeof (see the sidebar), though the main

focus is on the use of the preprocessor macro.

When you try it, you’ll see that the input to the macro is printed

as plain text, and then its value is printed, because #cmd is equivalent to cmd as a string. So Peval(list[0]) would expand to:

printf("list[0]" ": %g\n", list[0]);Does that look malformed to you, with the two strings "list[0]" ": %g\n" next to each other? The

next preprocessor trick is if two literal strings are adjacent, the

preprocessor merges them into one: "list[0]:

%g\n". And this isn’t just in macros:

printf("You can use the preprocessor's string "

"concatenation to break long lines of text "

"in your program. I think this is easier than "

"using backslashes, but be careful with spacing.");Conversely, you might want to join together two things that are

not strings. Here, use two octothorps, which I herein dub the

hexadecathorp: ##. If the value of

name is LL, then when you see name ## _list, read it as LL_list, which is a valid and usable variable

name.

Gee, you comment, I sure wish every

array had an auxiliary variable that gave its length. OK,

Example 8-3 writes a macro that declares a local

variable ending in _len for each list

you tell it to care about. It’ll even make sure every list has a

terminating marker, so you don’t even need the length.

That is, this macro is total overkill, and I don’t recommend it for immediate use, but it does demonstrate how you can generate lots of little temp variables that follow a naming pattern that you choose.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h> //NAN

#define Setup_list(name, ...) \

double *name ## _list = (double []){__VA_ARGS__, NAN}; \  int name ## _len = 0; \

for (name ## _len =0; \

!isnan(name ## _list[name ## _len]); \

) name ## _len ++;

int main(){

Setup_list(items, 1, 2, 4, 8);

int name ## _len = 0; \

for (name ## _len =0; \

!isnan(name ## _list[name ## _len]); \

) name ## _len ++;

int main(){

Setup_list(items, 1, 2, 4, 8);  double sum=0;

for (double *ptr= items_list; !isnan(*ptr); ptr++)

double sum=0;

for (double *ptr= items_list; !isnan(*ptr); ptr++)  sum += *ptr;

printf("total for items list: %g\n", sum);

#define Length(in) in ## _len

sum += *ptr;

printf("total for items list: %g\n", sum);

#define Length(in) in ## _len  sum=0;

Setup_list(next_set, -1, 2.2, 4.8, 0.1);

for (int i=0; i < Length(next_set); i++)

sum=0;

Setup_list(next_set, -1, 2.2, 4.8, 0.1);

for (int i=0; i < Length(next_set); i++)  sum += next_set_list[i];

printf("total for next set list: %g\n", sum);

}

sum += next_set_list[i];

printf("total for next set list: %g\n", sum);

}

The right-hand side of the equals sign uses a variadic macro to construct a compound literal. If this jargon is foreign to you, just focus on the macro work on the left-hand side and hold tight until Chapter 10.

Generates

items_lenanditems_list.

Here is a loop using the

NaNmarker.

Some systems let you query an array for its own length using a form like this.

Here is a loop using the

next_set_lenlength variable.

As a stylistic aside, there has historically been a custom to indicate that a function is actually a macro by putting it in all caps, as a warning to be careful to watch for the surprises associated with text substitution. I think this looks like yelling, and prefer to mark macros by capitalizing the first letter. Others don’t bother with the capitalization thing at all.

Linkage with static and extern

In this section, we write code that will tell the compiler what kind of advice it should give to the linker. The compiler works one .c file at a time, (typically) producing one .o file at at a time, then the linker joins those .o files together to produce one library or executable.

What happens if there are two declarations in two separate files for

the variable x? It could be that the

author of one file just didn’t know that the author of the other file had

chosen x, so the two xes should be broken up and into two separate

spaces. Or perhaps the authors were well aware that they are referring to

the same variable, and the linker should take all references of x to be pointing to the same spot in

memory.

External linkage means that symbols that match

across files should be treated as the same thing by the linker. For

functions and variables declared outside of a function, this is the

default, but the extern keyword will be

useful to indicate external linkage (see later).[10]

Internal linkage indicates that a file’s

instance of a variable x or a function

f() is its own and matches only other

instances of x or f() in the same scope (which for things declared

outside of any functions would be file scope). Use the static keyword to indicate internal

linkage.

It’s funny that external linkage has the extern keyword, but instead of something

sensible like intern for internal

linkage, there’s static. In Automatic, Static, and Manual Memory, I discussed the three types of memory model:

static, automatic, and manual. Using the word static for both linkage and memory model is

joining together two concepts that may at one time have overlapped for

technical reasons, but are now distinct.

For file scope variables,

staticaffects only the linkage:The default linkage is external, so use the

statickeyword to change this to internal linkage.Any variable in file scope will be allocated using the static memory model, regardless of whether you used

static int x,extern int x, or just plainint x.

For block scope variables,

staticaffects only the memory model:The default linkage is internal, so the

statickeyword doesn’t affect linkage. You could change the linkage by declaring the variable to beextern, but later, I will advise against this.The default memory model is automatic, so the

statickeyword changes the memory model to static.

For functions,

staticaffects only the linkage:Functions are only defined in file scope (gcc offers nested functions as an extension). As with file-scope variables, the default linkage is external, but use the

statickeyword for internal linkage.There’s no confusion with memory models, because functions are always static, like file-scope variables.

The norm for declaring a function to be shared across

.c files is to put the header in a

.h file to be reincluded all over your project, and

put the function itself in one .c file (where it will

have the default external linkage). This is a good norm, and is worth

sticking to, but it is reasonably common for authors to want to put one-

or two-line utility functions (like max

and min) in a .h

file to be included everywhere. You can do this by preceding the

declaration of your function with the static keyword, for example:

//In common_fns.h:

static long double max(long double a, long double b){

(a > b) ? a : b;

}

When you #include "common_fns.h"

in each of a dozen files, the compiler will produce a new instance of the

max function in each of them. But

because you’ve given the function internal linkage, none of the files has

made public the function name max, so

all dozen separate instances of the function can live independently with

no conflicts. Such redeclaration might add a few bytes to your executable

and a few milliseconds to your compilation time, but that’s irrelevant in

typical environments.

Externally Linked Variables in Header Files

The extern keyword is a simpler

issue than static, because it is only

about linkage, not memory models. The typical setup for a variable with

external linkage:

In a header to be included anywhere the variable will be used, declare your variable with the

externkeyword. E.g.,externint x.In exactly one

.cfile, declare the variable as usual, with an optional initializer. E.g.,int x=3. As with all static-memory variables, if you leave off the initial value (justint x), the variable is initialized to zero orNULL.

That’s all you have to do to use variables with external linkage.

You may be tempted to put the extern declaration not in a header, but just

as a loose declaration in your code. In file1.c,

you have declared int x, and you

realize that you need access to x in

file2.c, so you throw a quick extern int

x at the top of the file. This will work—today. Next month,

when you change file1.c to declare double x, the compiler’s type checking will

still find file2.c to be entirely internally

consistent. The linker blithely points the routine in

file2.c to the location where the double named x is stored, and the routine blithely misreads

the data there as an int. You can

avoid this disaster by leaving all extern declarations in a header to #include in both file1.c

and file2.c. If any types change anywhere, the

compiler will then be able to catch the inconsistency.

Under the hood, the system is doing a lot of work to make it easy

for you to declare one variable several times wile allocating memory for

it only once. Formally, a declaration marked as extern is a declaration (a statement of type

information so the compiler can do consistency checking), and not a

definition (instructions to allocate and initialize space in memory).

But a declaration without the extern

keyword is a tentative definition: if the compiler

gets to the end of the unit (defined below) and doesn’t see a

definition, then the tentative definitions get turned into a single

definition, with the usual initialization to zero or NULL. The standard defines

unit in that sentence as a single file, after

#includes are all pasted in (a

translation unit; see C99 & C11 §6.9.2(2)).

Compilers like gcc and Clang typically read

unit to mean the entire program, meaning that a

program with several non-extern

declarations and no definitions rolls all these tentative definitions up

into a single definition. Even with the --pedantic flag, gcc doesn’t care whether you

use the extern keyword or leave it

off entirely. In practice, that means that the extern keyword is largely optional: your

compiler will read a dozen declarations like int

x=3 as a single definition of a single variable with

external linkage. K&R [2nd ed, p 227] describe this behavior as

“usual in UNIX systems and recognized as a common extension by the

[ANSI] Standard”. [Harbison 1991] §4.8 documents

four distinct interpretations of the rules for externs.

This means that if you want two variables with the same name in

two files to be distinct, but you forget the static keyword, your compiler will probably

link those variables together as a single variable with external

linkage; subtle bugs can easily ensue. So be careful to use static for all file-scope variables intended

to have internal linkage.

The const Keyword

The const keyword is

fundamentally useful, but the rules around const have several surprises and

inconsistencies. This segment will point them out so they won’t be

surprises anymore, which should make it easier for you to use const wherever good style advises that you

do.

Early in your life, you learned that copies of input data are passed to functions, but you can still have functions that change input data by sending in a copy of a pointer to the data. When you see that an input is plain, not-pointer data, then you know that the caller’s original version of the variable won’t change. When you see a pointer input, it’s unclear. Lists and strings are naturally pointers, so the pointer input could be data to be modified, or it could just be a string.

The const keyword is a literary device for you,

the author, to make your code more readable. It is a type

qualifier indicating that the data pointed to by the input

pointer will not change over the course of the function. It is useful

information to know when data shouldn’t change, so do use this keyword

where possible.

The first caveat: the compiler does not lock down the data being

pointed to against all modification. Data that is marked as

const under one name can be modified using a different

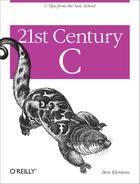

name. In Example 8-4, a and b point

to the same data, but because a is not

const in the header for set_elmt, it can change an element of the

b array. See Figure 8-1.

So const is a literary device,

not a lock on the data.

Noun-Adjective Form

The trick to reading declarations is to read from right to left. Thus:

int const= a constant integerint const *= a (variable) pointer to a constant integerint * const= a constant pointer to a (variable) integerint * const *= a pointer to a constant pointer to an integerint const * *= a pointer to a pointer to a constant integerint const * const *= a pointer to a constant pointer to a constant integer

You can see that the const

always refers to the text to its left, just as the * does.

You can switch a type name and const, and so write either int const or const

int (though you can’t do this switch with const and *). I prefer the int

const form because it provides consistency with the more

complex constructions and the right-to-left rule. There’s a custom to

use the const int form, perhaps

because it reads more easily in English or because that’s how it’s

always been done. Either works.

Tension

In practice, you will find that const sometimes creates tension that needs to

be resolved, when you have a pointer that is marked const, but want to send it as an input to a

function that does not have a const

marker in the right place. Maybe the function author thought that the

keyword was too much trouble, or believed the chatter about how shorter

code is always better code, or just forgot.

Before proceeding, you’ll have to ask yourself if there is any way

in which the pointer could change in the const-less function being called. There might

be an edge case where something gets changed, or some other odd reason.

This is stuff worth knowing anyway.

If you’ve established that the function does not break the promise

of const-ness that you made with your

pointer, then it is entirely appropriate to cheat and cast your const pointer to a

non-const for the sake of quieting the

compiler.

//No const in the header this time...

void set_elmt(int *a, int *b){

a[0] = 3;

}

int main(){

int a[10];

int const *b = a;

set_elmt(a, (int*)b); //...so add a type-cast to the call.

}The rule seems reasonable to me. You can override the compiler’s const-checking, as long as you are explicit about it and indicate that you know what you are doing.

If you are worried that the function you are calling won’t fulfill

your promise of const-ness, then you

can take one step further and make a full copy of the data, not just an

alias. Because you don’t want any changes in the variable anyway, you

can throw out the copy afterward.

Depth

Let us say that we have a struct—name it counter_s—and we have a function that takes in

one of these structs, of the form f(counter_s

const *in). Can the function modify the elements of the

structure?

Let’s try it: Example 8-5 generates a struct with

two pointers, and in ratio, that

struct becomes const, yet when we

send one of the pointers held by the structure to the const-less

subfunction, the compiler doesn’t complain.

#include <assert.h>

#include <stdlib.h> //assert

typedef struct {

int *counter1, *counter2;

} counter_s;

void check_counter(int *ctr){ assert(*ctr !=0); }

double ratio(counter_s const *in){  check_counter(in->counter2);

check_counter(in->counter2);  return *in->counter1/(*in->counter2+0.0);

}

int main(){

counter_s cc = {.counter1=malloc(sizeof(int)),

return *in->counter1/(*in->counter2+0.0);

}

int main(){

counter_s cc = {.counter1=malloc(sizeof(int)),  .counter2=malloc(sizeof(int))};

*cc.counter1 = *cc.counter2 = 1;

ratio(&cc);

}

.counter2=malloc(sizeof(int))};

*cc.counter1 = *cc.counter2 = 1;

ratio(&cc);

}In the definition of your struct, you can specify that an element

be const, though this is typically

more trouble than it is worth. If you really need to protect only the

lowest level in your hierarchy of types, your best bet is to put a note

in the documentation.

The char const ** Issue

Example 8-6 is a simple program to check

whether the user gave Iggy Pop’s name on the command line. Sample usage

from the shell (recalling that $? is

the return value of the just-run program):

iggy_pop_detector Iggy Pop; echo $? #prints 1 iggy_pop_detector Chaim Weitz; echo $? #prints 0

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <strings.h> //strcasecmp

bool check_name(char const **in){  return (!strcasecmp(in[0], "Iggy") && !strcasecmp(in[1], "Pop"))

||(!strcasecmp(in[0], "James") && !strcasecmp(in[1], "Osterberg"));

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

if (argc < 2) return 0;

return check_name(&argv[1]);

}

return (!strcasecmp(in[0], "Iggy") && !strcasecmp(in[1], "Pop"))

||(!strcasecmp(in[0], "James") && !strcasecmp(in[1], "Osterberg"));

}

int main(int argc, char **argv){

if (argc < 2) return 0;

return check_name(&argv[1]);

}The check_name function takes

in a pointer to (string that is constant), because there is no need to

modify the input strings. But when you compile it, you’ll find that you

get a warning. Clang says: “passing char

** to parameter of type const char

** discards qualifiers in nested pointer types.” In a sequence

of pointers, all the compilers I could find will convert to

const what you could call the top-level pointer

(casting to char * const *), but

complain when asked to const-ify what that pointer is

pointing to (char const **, aka

const char **).

Again, you’ll need to make an explicit cast—replace check_name(&argv[1]) with:

check_name((char const**)&argv[1]);

Why doesn’t this entirely sensible cast happen automatically? We need some creative setup before a problem arises, and the story is inconsistent with the rules to this point. So the explanation is a slog; I will understand if you skip it.

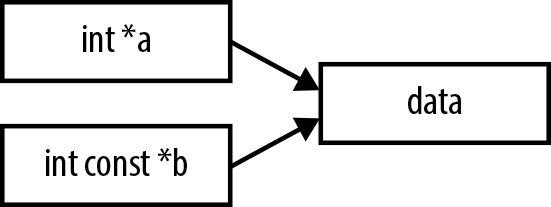

The code in Example 8-7 creates the three links

in the diagram: the direct link from constptr

-> fixed, and the two steps in the indirect link from

constptr -> var and var -> fixed. In the code, you can see that

two of the assignments are made explicitly: constptr -> var and constptr -> -> fixed. But because

*constptr == var, that second link

implicitly creates the var ->

fixed link. When we assign *var=30, that assigns fixed = 30.

We would never allow int *var

to point directly at int const fixed.

We only managed it via a sleight-of-pointer where var winds up implicitly pointing to fixed without explicitly stating it.

Note

Your Turn: Is it possible to

cause a failure of const like this

one, but where the disallowed type cast happens over the course of a

function call, as per the Iggy Pop detector?

As earlier, data that is marked as const under

one name can be modified using a different name. So, really, it’s little

surprise that we were able to modify the const data using an alternative name.[11]

I enumerate this list of problems with const so that you can surmount them. As

literature goes, it isn’t all that problematic, and the recommendation

that you add const to your function

declarations as often as appropriate still stands—don’t just grumble

about how the people who came before you didn’t provide the right

headers. After all, some day others will use your code, and you don’t

want them grumbling about how they can’t use the const keyword because your functions don’t

have the right headers.

[10] This is from C99 & C11 §6.2.3, which is actually about resolving symbols across different scopes, not just files, but trying crazy linkage tricks across different scopes within one file is generally not done.

[11] The code here is a rewrite of the example in C99 & C11

§6.5.16.1(6), where the line analogous to constptr=&var is marked as a constraint violation. Why do gcc and Clang

mark it as a warning, instead of halting? Because it’s technically

correct: C99 & C11 §6.3.2.3(2), regarding type qualifiers like

const, explains that, “For any

qualifier q, a pointer to a

non-q-qualified type may be converted to a

pointer to the q-qualified version of the

type…”