Chapter 3. Packaging Your Project

If you’ve read this far, then you have met the tools that solve the core problems for dealing with C code, like debugging and documenting it. If you’re eager to get going with C code itself, then feel free to skip ahead to Part II. This chapter and the next will cover some heavy-duty tools intended for collaboration and distribution to others: package-building tools and a revision-control system. Along the way, there will be many digressions about how you can use these tools to write better even when working solo.

In the present day, Autotools, a system for autogenerating the perfect makefile for a given system, is central to how code is distributed. You’ve already met it in Using Libraries from Source, where you used it to quickly install the GNU Scientific Library. Even if you’ve never dealt with it directly, it is probably how the people who maintain your package-management system produced just the right build for your computer.

But you’ll have trouble following what Autotools is doing unless you have a good idea of how a makefile works, so we need to cover those in a little more detail first. But to a first approximation, makefiles are organized sets of shell commands, so you’ll need to get to know the various facilities the shell offers for automating your work. The path is long, but at the end you will be able to:

Use the shell to automate work.

Use makefiles to organize all those tasks you have the shell doing.

Use Autotools to let users autogenerate makefiles on any system.

This chapter is heavy on shell code and command-prompt work, because the distribution of code relies heavily on POSIX-standard shell scripts. So even if you are an IDE user who avoids the command prompt, this stuff is worth knowing. Also, your IDE is probably a thin wrapper around the shell commands covered here, so when your IDE spits out a cryptic error, this chapter might help you decipher it.

The Shell

A POSIX-standard shell will have the following:

Abundant macro facilities, in which your text is replaced with new text—i.e., an expansion syntax

A Turing-complete programming language

An interactive frontend—the command prompt—which might include lots of user-friendly tricks

A system for recording and reusing everything you typed: history

Lots of other things I won’t mention here, such as job control and many built-in utilities

There is a lot of shell scripting syntax, so this section covers only a few pieces of low-hanging syntactic fruit for these categories. There are many shells to be had (and later, a sidebar will suggest trying a different one from the one you’re using now), but unless otherwise noted, this section will stick to the POSIX standard.

I won’t spend much time on the interactive features, but I have to

mention one that isn’t even POSIX-standard: tab completion. In bash, if

you type part of a filename and hit the Tab key, the name will be

autocompleted if there’s only one option, and if not, hit Tab again to see

a list of options. If you want to know how many commands you can type on

the command line, hit Tab twice on a blank line and bash will give you the

whole list. Other shells go much further than bash: type make <tab> in the Z shell and it will read

your makefile for the possible targets. The Friendly Interactive shell

(fish) will check the manual pages for the summary lines, so when you type

man l<tab> it will give you a

one-line summary of every command beginning with L, which could save you

the trouble of actually pulling up any manpage at all.

There are two types of shell users: those who didn’t know about this tab-completion thing, and those who use it all the time on every single line. If you were one of those people in that first group, you’re going to love being in the second.

Replacing Shell Commands with Their Outputs

A shell largely behaves like a macro language, wherein certain blobs of text get replaced with other blobs of text. These are called expansions in the shell world, and there are many types: this section touches on variable substitution, command substitution, a smattering of history substitution, and will give examples touching on tilde expansion and arithmetic substitution for quick desk calculator math. I leave you to read your shell’s manual on alias expansion, brace expansion, parameter expansion, word splitting, pathname expansion, and glob expansion.

Variables are a simple expansion. If you set a variable like

onething="another thing"

on the command line, then when you later type:

echo$onething

then another thing will print

to screen.

Your shell will require that there be no spaces on either side of

the =, which will annoy you at some

point.

When one program starts a new program (in POSIX C, when the

fork() system call is used), a copy

of all environment variables is sent to the child program. Of course,

this is how your shell works: when you enter a command, the shell forks

a new process and sends all the environment variables to the

child.

Environment variables, however, are a subset of the shell variables. When you make an assignment like the previous one, you have set a variable for the shell to use; when you:

export onething="another thing"

then that variable is available for use in the shell, and its export attribute is set. Once the export attribute is set, you can still change the variable’s value.

For our next expansion, how about the backtick, `, which is not the more vertical-looking

single tick '.

Note

The vertical tick (', not the

backtick) indicates that you don’t want expansions done. The

sequence:

onething="another thing"echo"$onething"echo'$onething'

will print:

another thing

$onethingThe backtick replaces the command you give with its output, doing so macro-style, where the command text is replaced in place with the output text.

Example 3-1 presents a script that counts lines

of C code by how many lines have a ;,

), or } on them. Given that lines of source code is

a lousy metric for most purposes anyway, this is as good a means as any,

and has the bonus of being one line of shell code.

# Count lines with a ;, ), or }, and let that count be named Lines.Lines=`grep'[;)}]'*.c|wc-l`# Now count how many lines there are in a directory listing; name it Files.Files=`ls*.c|wc-l`echofiles=$Filesandlines=$Lines# Arithmetic expansion is a double-paren.# In bash, the remainder is truncated; more on this later.echolines/file=$(($Lines/$Files))# Or, use those variables in a here script.# By setting scale=3, answers are printed to 3 decimal places.bc<<---scale=3$Lines/$Files---

You can run the shell script via . linecount.sh. The dot

is the POSIX-standard command to source a script. Your shell probably

also lets you do this via the nonstandard but much more comprehensible

source

linecount.sh.

Use the Shell’s for Loops to Operate on a Set of Files

Let’s get to some proper programming, with if

statements and for loops.

But first, some caveats and annoyances about shell scripting:

Scope is awkward—pretty much everything is global.

It’s effectively a macro language, so all those text interactions that they warned you about when you write a few lines of C preprocessor code (see Cultivate Robust and Flourishing Macros) are largely relevant for every line of your shell script.

There isn’t really a debugger that can execute the level-jumping basics from Using a Debugger, though modern shells will provide some facilities to trace errors or verbosely run scripts.

You’ll have to get used to the little tricks that will easily catch you, like how you can’t have spaces around the

=inonething=another, but you must have spaces around the[and]inif [ -e ff ](because they’re keywords that just happen to not have any letters in them).

Some people don’t see these details as much of an issue, and ♥ the shell. Me, I write shell scripts to automate what I would type at the command line, and once things get complex enough that there are functions calling other functions, I take the time to switch to Perl, Python, awk, or whatever is appropriate.

My vote for greatest bang for the buck from having a programming language that you can type directly onto the command line goes to running the same command on several files. Let’s back up every .c file the old fashioned way, by copying it to a new file with a name ending in .bkup:

for file in *.c;

do

cp $file ${file}.bkup;

doneYou see where the semicolon is: at the end of the list of files

the loop will use, on the same line as the for statement. I’m pointing this out because

when cramming this onto one line, as in:

for file in *.c; do cp $file ${file}.bkup; doneI always forget that the order is ;

do and not do ;.

The for loop is useful for

dealing with a sequence of N runs of a program. By

way of a simple example, benford.sh searches C

code for numbers beginning with a certain digit (i.e., head of the line

or a nondigit followed by the digit we are looking for), and writes each

line that has the given number to a file, as shown in Example 3-2:

for i in 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9; do grep -E '(^|[^0-9.])'$i *.c > lines_with_${i}; done

wc -l lines_with* //A rough histogram of your digit usage.

Testing against Benford’s law is left as an exercise for the reader.

The curly braces in ${i} are

there to distinguish what is the variable name and what is subsequent

text; you don’t need it here, but you would if you wanted a filename

like ${i}lines.

You probably have the seq

command installed on your machine—it’s BSD/GNU standard but not POSIX

standard. Then we can use backticks to generate a sequence:

for i in `seq 0 9`; do grep -E '(^|[^0-9.])'$i *.c > lines_with_${i}; doneRunning your program a thousand times is now trivial:

for i in `seq 1 1000`; do./run_program> ${i}.out; done #or append all output to a single file: for i in `seq 1 1000`; do echo output for run $i: >>run_outputs./run_program>>run_outputsdone

Test for Files

Now let’s say that your program relies on a data set that has to be read in from a text file to a database. You only want to do the read-in once, or in pseudocode: if (database exists) then (do nothing), else (generate database from text).

On the command line, you would use test, a versatile command typically built into

the shell. To try it, run a quick ls,

get a filename you know is there, and use test to check that the file exists like

this:

test -e a_file_i_know

echo $?By itself, test outputs

nothing, but because you’re a C programmer, you know that every program

has a main function that returns an

integer, and we will use only that return value here. Custom is to read

the return value as a problem number, so 0==no problem, and in this case

1==file does not exist (which is why, as will be discussed in Don’t Bother Explicitly Returning from main, the default is that main returns zero). The shell doesn’t print

the return value to the screen, but stores it in a variable, $?, which you can print via echo.

The echo command itself has a return value, and

$? will be set to that value after you run

echo $?. If you want to use the value of

$? for a specific command more than once, assign it

to a variable, such as

returnval=$?.

Now let us use it in an if

statement to act only if a file does not exist. As in C, ! means not.

iftest! -e a_test_file;thenecho testfile had not existed touch a_test_fileelseecho testfile existed rm a_test_filefi

Notice that, as with the for

loops from last time, the semicolon is in what I consider an awkward

position, and we have the super-cute rule that we end if blocks with fi. By the way, else if is not

valid syntax; use the elif keyword.

To make it easier for you to run this repeatedly, let’s cram it

onto one margin-busting line. The keywords [ and ] are

equivalent to test, so when you see

this form in other people’s scripts and want to know what’s going on,

the answer is in man test.

if [ ! -e a_test_file ]; then echo test file had not existed; ↩ touch a_test_file; else echo test file existed; rm a_test_file; fi

Because so many programs follow the custom that zero==OK and

nonzero==problem, we can use if statements without

test to express the clause

if the program ran OK, then…. For example, it’s

common enough to use tar to archive a

directory into a single .tgz file, then delete the

directory. It would be a disaster if the tar file somehow didn’t get

created but the directory contents were deleted anyway, so we should

have some sort of test that the tar

command completed successfully before deleting everything:

#generate some test files

mkdir a_test_dir

echo testing ... testing > a_test_dir/tt

if tar cz a_test_dir > archived.tgz; then

echo Compression went OK. Removing directory.

rm -r a_test_dir

else

echo Compression failed. Doing nothing.

fiIf you want to see this fail after running once, try chmod 000 archived.tgz to make the destination

archive unwritable, then rerun.

fc

fc is a (POSIX-standard)

command for turning your noodling on the shell into a repeatable script.

Try:

fc -l # The l is for list and is important.You now have on the screen a numbered list of your last few

commands. Your shell might let you type history to get the same effect.

The -n flag suppresses the line

numbers, so you can write history items 100 through 200 to a file

via:

fc -l -n 100 200 > a_scriptthen remove all the lines that were experiments that didn’t work, and you’ve converted your futzing on the command line into a clean shell script.

If you omit the -l flag, then

fc becomes a more immediate and

volatile tool. It pulls up an editor (which means if you

redirect with >, you’re basically

hung), doesn’t display line numbers, and when you quit your editor,

whatever is in that file gets executed immediately. This is great for a

quick repetition of the last few lines, but can be disastrous if you’re

not careful. If you realize that you forgot the -l or are otherwise surprised to see yourself

in the editor, delete everything on the screen to prevent unintended

lines from getting executed.

But to end on a positive note, fc stands for fix

command, and that is its simplest usage. With no options, it

edits the prior line only, so it’s nice for when you need to make

elaborate corrections to a command.

Makefiles vs. Shell Scripts

You probably have a lot of little procedures associated with a project floating around (word count, spell check, run tests, write to revision control, push revision control out to a remote, make backup), all of which could be automated by a shell script. But rather than producing a new one- or two-line script for every little task you have for your project, you can put them all into a makefile.

Makefiles were first covered in Using Makefiles, but

now that we’ve covered the shell in more detail, we have more that we can

put into a makefile. Here’s one more example target from my daily life,

which uses the if/then shell syntax

and test. I use Git, but there are

three Subversion repositories I have to deal with, and I never remember

the procedures. As in Example 3-4, I now have a makefile to

remember for me.

I need a message for each commit, so I do that via an environment variable set on the command line, via:

MSG="This is a commit." make push. This line is anif-thenstatement that prints a reminder if I forget this.

Test to make sure that

"x$(MSG)"expands to something besides just"x", meaning that$(MSG)is not empty. This is a common shell idiom to make up for an idiotic glitch about blank strings. If the test fails,makedoes not continue.

The commands executed in a makefile are in some ways just what you would type on the command line, and in some ways drastically different:

Every line runs independently, in a separate shell. If you write this into your makefile:

clean: cd junkdir rm -f * # Do not put this in a makefile.then you will be a sad puppy. The two lines in the script are equivalent to C code like this:

system("cd junkdir"); system("rm -f *");Or, because

system("cmd")is equivalent tosh -c "cmd", ourmakescript is also equivalent to:sh -c "cd junkdir" sh -c "rm -f *"

And for the shell geeks,

(cmd)runscmdin a subshell, so themakesnippet is also equivalent to typing this at the shell prompt:(cd junkdir) (rm -f *)

In all cases, the second subshell knows nothing of what happened in the first subshell.

makewill first spawn a shell that changes in to the directory you are emptying, thenmakeis done with that subshell. Then it starts a new subshell from the directory you started in and callsrm -f *.On the plus side,

makewill delete the erroneous makefile for you. If you want to express the thought in this form, do it like this:cd junkdir && rm -f *

where the

&&runs commands in short-circuit sequence just like in C (i.e., if the first command fails, don’t bother running the second). Or use a backslash to join two lines into one:cd junkdir&& \ rm -f *

Though for a case like this, I wouldn’t trust just a backslash. In real life, you’re better off just using

rm -f junkdir/*anyway.

makereplaces instances of$x(for one-letter or one-symbol variable names) or$(xx)(for multiletter variable names) with the appropriate values.If you want the shell, not

make, to do the substitution, then drop the parens and double your$$s. For example, to use the shell’s variable mangling to name backups from a makefile:for i in *.c; do cp $$i $${i%%.c}.bkup; done.Recall the trick from Using Makefiles where you can set an environment variable just before a command, e.g.,

CFLAGS=-O3 gcc test.c. That can come in handy now that each shell survives for a single line. Don’t forget that the assignment has to come just before a command and not a shell keyword likeiforwhile.An

@at the head of a line means run the command but don’t echo anything to the screen as it happens.A

-at the head of a line means that if the command returns a nonzero value, keep going anyway. Otherwise, the script halts on the first nonzero return.

For simpler projects and most of your day-to-day annoyances, a makefile using all those features from the shell will get you very far. You know the quirks of the computer you use every day, and the makefile will let you write them down in one place and stop thinking about them.

Will your makefile work for a colleague? If your program is a common

set of .c files and any necessary libraries are

installed, and the CFLAGS and LDLIBS in your makefile are right for your

recipient’s system, then perhaps it will all work fine, and at worst will

require an email or two clarifying things. If you are generating a shared

library, then forget about it—the procedure for generating a shared

library is very different for Mac, Linux, Windows, Solaris, or different

versions of each. When distributing to the public at large, everything

needs to be as automated as possible, because it’s hard to trade emails

about setting flags with dozens or hundreds of people, and most people

don’t want to put that much effort into making a stranger’s code work

anyway. For all these reasons, we need to add another layer for publicly

distributed packages.

Packaging Your Code with Autotools

The Autotools are what make it possible for you to download a library or program, and run:

./configure make sudo make install

(and nothing else) to set it up. Please recognize what a miracle of

modern science this is: the developer has no idea what sort of computer

you have, where you keep your programs and libraries

(/usr/bin? /sw?

/cygdrive/c/bin?), and who knows what other quirks

your machine demonstrates, and yet configure sorted everything out so that make could run seamlessly. And so, Autotools is

central to how code gets distributed in the modern day. If you want

anybody who is not on a first-name basis with you to use your code (or if

you want a Linux distro to include your program in their package manager),

then having Autotools generate the build for you will significantly raise your

odds.

It is easy to find packages that depend on some existing framework for installation, such as Scheme, Python ≥2.4 but <3.0, Red Hat Package Manager (RPM), and so on. The framework makes it easy for users to install the package—right after they install the framework. Especially for users without root privileges, such requirements can be a show stopper. The Autotools stand out in requiring only that the user have a computer with rudimentary POSIX compliance.

Using the Autotools can get complex, but the basics are simple. By the end of this, we will have written six lines of packaging text and run four commands, and will have a complete (albeit rudimentary) package ready for distribution.

The actual history of Autoconf, Automake, and Libtool is somewhat involved: these are distinct packages, and there is a reason to run any of them without the other. But here’s how I like to imagine it all happening.

Meno: I love make. It’s so nice that I can write down all the

little steps to building my project in one place.

Socrates: Yes, automation is great. Everything should be automated, all the time.

Meno: I have lots

of targets in my makefile, so users can type make to produce the program, make install to install, make check to run tests, and so on. It’s a lot

of work to write all those makefile targets, but so smooth when it’s all

assembled.

Socrates: OK, I shall write a system—it will be called Automake—that will automatically generate makefiles with all the usual targets from a very short pre-makefile.

Meno: That’s great. Producing shared libraries is especially annoying, because every system has a different procedure.

Socrates: It is annoying. Given the system information, I shall write a program for generating the scripts needed to produce shared libraries from source code, and then put those into Automade makefiles.

Meno: Wow, so all I have to do is

tell you my operating system, and whether my compiler is named cc or clang

or gcc or whatever, and you’ll drop in

the right code for the system I’m on?

Socrates: That’s error-prone. I will write a system called Autoconf that will be aware of every system out there and that will produce a report of everything Automake and your program needs to know about the system. Then Autoconf will run Automake, which will use the list of variables in my report to produce a makefile.

Meno: I am flabbergasted—you’ve automated the process of autogenerating makefiles. But it sounds like we’ve just changed the work I have to do from inspecting the various platforms to writing configuration files for Autoconf and makefile templates for Automake.

Socrates: You’re right. I shall write a tool, Autoscan, that will scan the Makefile.am you wrote for Automake, and autogenerate Autoconf’s configure.ac for you.

Meno: Now all you have to do is autogenerate Makefile.am.

Socrates: Yeah, whatever. RTFM and do it yourself.

Each step in the story adds a little more automation to the step that came before it: Automake uses a simple script to generate makefiles (which already go far in automating compilation over manual command-typing); Autoconf tests the environment and uses that information to run Automake; Autoscan checks your code for what you need to make Autoconf run. Libtool works in the background to assist Automake.

An Autotools Demo

Example 3-5 presents a script that gets Autotools to take care of Hello, World. It is in the form of a shell script you can copy/paste onto your command line (as long as you make sure there are no spaces after the backslashes). Of course, it won’t run until you ask your package manager to install the Autotools: Autoconf, Automake, and Libtool.

if [ -e autodemo ]; then rm -r autodemo; fi mkdir -p autodemocd autodemo cat > hello.c <<\ "--------------" #include <stdio.h> int main(){ printf("Hi.\n"); } -------------- cat > Makefile.am <<\

"--------------" bin_PROGRAMS=hello hello_SOURCES=hello.c -------------- autoscan

sed -e 's/FULL-PACKAGE-NAME/hello/' \

-e 's/VERSION/1/' \ -e 's|BUG-REPORT-ADDRESS|/dev/null|' \ -e '10i\ AM_INIT_AUTOMAKE' \ < configure.scan > configure.ac touch NEWS README AUTHORS ChangeLog

autoreconf -iv

./configure make distcheck

Create a directory and use a here document to write hello.c to it.

We need to hand-write Makefile.am, which is two lines long. The

hello_SOURCESline is optional, because Automake can guess that hello will be built from a source file named hello.c.

Edit configure.scan to give the specs of your project (name, version, contact email), and add the line

AM_INIT_AUTOMAKEto initialize Automake. (Yes, this is annoying, especially given that Autoscan used Automake’s Makefile.am to gather info, so it is well aware that we want to use Automake.) You could do this by hand; I usedsedto directly stream the customized version to configure.ac.

These four files are required by the GNU coding standards, and so GNU Autotools won’t proceed without them. I cheat by creating blank versions using the POSIX-standard

touchcommand; yours should have actual content.

Given configure.ac, run

autoreconfto generate all the files to ship out (notably, configure). The-iflag will produce extra boilerplate files needed by the system.

How much do all these macros do? The hello.c

program itself is a leisurely three lines and

Makefile.am is two lines, for five lines of

user-written text. Your results may differ a little, but when I run

wc -l * in the post-script directory,

I find 11,000 lines of text, including a 4,700-line configure script.

It’s so bloated because it’s so portable: your recipients probably don’t have Autotools installed, and who knows what else they’re missing, so this script depends only on rudimentary POSIX-compliance.

I count 73 targets in the 600-line makefile.

The default target, when you just type

makeon the command line, produces the executable.sudo make installwould install this program if you so desire; runsudo makeuninstallto clear it out.There is even the mind-blowing option to

make Makefile(which actually comes in handy if you make a tweak to Makefile.am and want to quickly regenerate the makefile).As the author of the package, you will be interested in

make distcheck, which generates a tar file with everything a user would need to unpack and run the usual./configure; make; sudo make install(without the aid of the Autotools system that you have on your development box), and verifies that the distribution is OK, such as running any tests you may have specified.

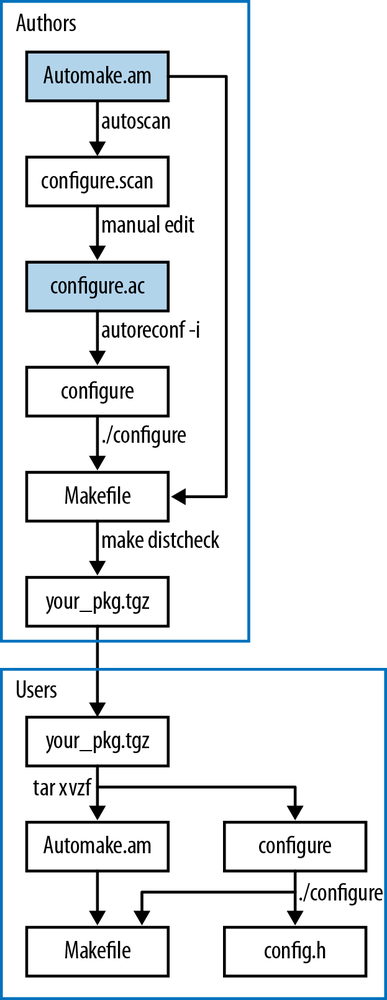

Figure 3-1 summarizes the story as a flow diagram.

You will only be writing two of these files (the shaded ones);

everything else is autogenerated by the given command. Let’s start from

the bottom portion: the user gets your package as a tarball, and untars

it via tar xvzf

your_pkg.tgz, which produces a directory with your

code, Makefile.am, configure,

and a host of other auxiliary files that aren’t worth discussing here.

The user types ./configure, and that

produces configure.h and the

Makefile. Now everything is in place for the user

to type make; sudo make

install.

As an author, your goal is to produce that tarball, with a

high-quality configure and

Makefile.am, so the user can run his or her part

without a hitch. Start by writing Makefile.am yourself. Run autoscan to get a preliminary

configure.scan, which you will manually edit to

configure.ac. (Not shown: the four files required

by the GNU coding standards: NEWS,

README, AUTHORS, and

ChangeLog.) Then run autoreconf -iv to generate the configure script (plus many other auxiliary

files). Given the configure script, you can now run it to produce the

makefile; given the makefile, you can run make

distcheck to generate the tarball to ship out.

Notice that there is some overlap: you will be using the same configure and Makefile as the user does, though your purpose is to produce a package and the user’s purpose is to install the package. That means you have the facilities to install and test the code without fully packaging it, and users have the facility to repackage the code if somehow so inclined.

Describing the Makefile with Makefile.am

A typical makefile is half about the structure of what parts of your project depend on what other parts, and half about the specific variables and procedures to execute. Your Makefile.am will focus on the structure of what needs to be compiled and what it depends on, and the specifics will be filled in by Autoconf and Automake’s built-in knowledge of compilation on different platforms.

Makefile.am will consist of two types of entry, which I will refer to as form variables and content variables.

Form variables

A file that has to be handled by the makefile may have any of a number of intents, each of which Automake annotates by a short string.

- bin

Install to wherever programs go on the system, e.g., /usr/bin or /usr/local/bin.

- include

- lib

- pkgbin

If your project is named

project, install to a subdirectory of the main program directory, e.g., /usr/local/bin/project/(similarly forpkgincludeorpkglib).- check

Use for testing the program, when the user types

make check.- noinst

Don’t install; just keep the file around for use by another target.

Automake generates boilerplate make scripts, and it’s got different boilerplate for:

PROGRAMS HEADERS LIBRARIES static libraries LTLIBRARIES shared libraries generated via Libtool DIST items to be distributed with the package, such as data files that didn’t go elsewhere

An intent plus a boilerplate format equals a form variable. For example:

bin_PROGRAMS programs to build and install

check_PROGRAMS programs to build for testing

include_HEADERS headers to install in the system-wide include directory

lib_LTLIBRARIES dynamic and shared libraries, via Libtool

noinst_LIBRARIES static library (no Libtool), to keep on hand for later

noinst_DIST distribute with the package, but that's all

python_PYTHON Python code, to byte-compile and install wherever Python packages goNow that you have the form down, you can use these to specify how each file gets handled. In the Hello, World example earlier, there was only one file that had to be dealt with:

bin_PROGRAMS=hello

To give another example, noinst_DIST is where I put data that is

needed for the postcompilation tests but is not worth installing. Put

as many items on each line as you’d like. For example:

pkginclude_HEADERS=firstpart.h secondpart.hnoinst_DIST=sample1.csv sample2.csv\sample3.csv sample4.csv

Content variables

Items under noinst_DIST just

get copied into the distribution package, and

HEADERS just get copied to the destination

directory and have their permissions set appropriately. So those are

basically settled.

For the compilation steps such as …_PROGRAMS and …_LDLIBRARIES, Automake needs to know more

details about how the compilation works. At the very least, it needs

to know what source files are being compiled. Thus, for every item on

the right side of an equals sign of a form variable about compilation,

we need a variable specifying the sources. For example, with these two

programs we need two SOURCES

lines:

bin_PROGRAMS= weather wxpredict weather_SOURCES= temp.c barometer.c wxpredict_SOURCES=rng.c tarotdeck.c

This may be all you need for a basic package.

Warning

Here we have another failure of the principle that things that

do different things should look different: the content variables

have the same lower_UPPER look as

the form variables shown earlier, but they are formed from entirely

different parts and serve entirely different purposes.

Recall from the discussion about plain old makefiles that there

are certain default rules built into make, which

use variables like CFLAGS to tweak

the details of what gets done. Automake’s form variables effectively

define more default rules, and they each have their own set of

associated variables.

For example, the rule for linking together object files to form an executable might look something like:

$(CC) $(LDFLAGS)temp.o barometer.o$(LDADD) -oweather

Warning

GNU Make uses LDLIBS for

the library variable at the second half of the link command, and GNU

Automake uses LDADD for the

second half of the link command.

It’s not all that hard to use your favorite Internet search engine to find the documentation that explains how a given form variable blows up into a set of targets in the final makefile, but I’ve found that the fastest way to find out what Automake does is to just run it and look at the output makefile in a text editor.

You can set all of these variables on a per-program or

per-library basis, such as weather_CFLAGS=-O1. Or, use AM_VARIABLE to

set a variable for all compilations or linkings. Here are my favorite

compiler flags, which you met in the section Using Makefiles:

AM_CFLAGS=-g -Wall -O3

I didn’t include -std=gnu99

to get gcc to use a less obsolete standard, because this is a

compiler-specific flag. If I put AC_PROG_CC_C99 in

configure.ac, then Autoconf will set the CC variable to gcc

-std=gnu99 for me. Autoscan isn’t (yet) smart enough to put

this into the configure.scan that it generates

for you, so you will probably have to put it into

configure.ac yourself. (As of this writing, there

isn’t yet an AC_PROG_CC_C11

macro.)

Specific rules override AM_-based rules, so if you want to keep the

general rules and add on an override for one flag, you would need a

form like:

AM_CFLAGS=-g -Wall -O3 hello_CFLAGS = $(AM_CFLAGS) -O0

Adding testing

I haven’t yet presented to you the dictionary library (which is covered all the way in Extending Structures and Dictionaries), but I have shown you the test harness for it, in Unit Testing. When Autotools pushes out the library, it makes sense to run the tests again. The agenda is now to build:

A library, based on dict.c and keyval.c. It has headers, dict.h and keyval.h, which will need to ship out with the library.

A testing program, which Automake needs to be aware is for testing, not for installation.

The program,

dict_use, that makes use of the library.

Example 3-6 expresses this agenda. The library

gets built first, so that it can be used to generate the program and

the test harness. The TESTS

variable specifies which programs or scripts get run when the user

types make check.

AM_CFLAGS=`pkg-config --cflags glib-2.0` -g -O3 -Walllib_LTLIBRARIES=libdict.la

libdict_la_SOURCES=dict.c keyval.c

include_HEADERS=keyval.h dict.h bin_PROGRAMS=dict_use dict_use_SOURCES=dict_use.c dict_use_LDADD=libdict.la

TESTS=$(check_PROGRAMS)

check_PROGRAMS=dict_test dict_test_LDADD=libdict.la

Here, I cheated, because other users might not have pkg-config installed. If we can’t assume

pkg-config, the best we can do is check for the library via Autoconf’sAC_CHECK_HEADERandAC_CHECK_LIB, and if something is not found, ask the user to modify theCFLAGSorLDFLAGSenvironment variables to specify the right-Ior-Lflags. Because we haven’t gotten to the discussion of configure.ac, I just use pkg-config.

The first course of business is generating the shared library (via Libtool, and thus the

LTinLTLIBRARIES).

When writing a content variable from a filename, change anything that is not a letter, number, or @ sign into an underscore, as with

libdict.la⇒libdict_la.

Now that we’ve specified how to generate a shared library, we can use the shared library for assembling the program and tests.

The

TESTSvariable specifies the tests that run when users typemake check. Because these are often shell scripts that need no compilation, it is a distinct variable fromcheck_PROGRAMS, which specifies programs intended for checking that have to be compiled. In our case, the two are identical, so we set one to the other.

Adding makefile bits

If you’ve done the research and found that Automake can’t handle some odd target, then you can write it into Makefile.am as you would to the usual makefile. Just write a target and its associated actions as in:

target:depsscript

anywhere in your Makefile.am, and Automake will copy it into the final makefile verbatim. For example, the Makefile.am in Python Host explicitly specifies how to compile a Python package, because Automake by itself doesn’t know how (it just knows how to byte-compile standalone .py files).

Variables outside of Automake’s formats also get added verbatim. This will especially be useful in conjunction with Autoconf, because if Makefile.am has variable assignments such as:

TEMP=@autotemp@HUMIDITY=@autohum@

and your configure.ac

has:

#configure is a plain shell script; these are plain shell variables autotemp=40 autohum=.8

AC_SUBST(autotemp) AC_SUBST(autohum)

then the final makefile will have text reading:

TEMP=40 HUMIDITY=.8

So you have an easy conduit from the shell script that Autoconf spits out to the final makefile.

The configure Script

The configure.ac shell script produces two outputs: a makefile (with the help of Automake), and a header file named config.h.

If you’ve opened one of the sample

configure.ac files produced so far, you might have

noticed that it looks nothing at all like a shell script. This is

because it makes heavy use of a set of macros (in the m4 macro language)

that are predefined by Autoconf. Rest assured that every one of them

will blow up into familiar-looking lines of shell script. That is,

configure.ac isn’t a recipe or specification to

generate the configure shell script,

it is configure,

just compressed by some very impressive macros.

The m4 language doesn’t have all that much syntax. Every macro is

function-like, with parens after the macro name listing the

comma-separated arguments (if any; else the parens are typically

dropped). Where most languages write 'literal

text', m4-via-Autoconf writes [literal text], and to prevent surprises where

m4 parses your inputs a little too aggressively, wrap all of your macro

inputs in those square brackets.

The first line that Autoscan generated is a good example:

AC_INIT([FULL-PACKAGE-NAME], [VERSION], [BUG-REPORT-ADDRESS])

We know that this is going to generate a few hundred lines of shell code, and somewhere in there, the given elements will be set. Change the values in square brackets to whatever is relevant. You can often omit elements, so something like:

AC_INIT([hello], [1.0])

is valid if you don’t want to hear from your users. At the

extreme, one might give zero arguments to a macro like AC_OUTPUT, in which case you don’t need to

bother with the parentheses.

Warning

The current custom in m4 documentation is to mark optional arguments with—I am not making this up—square brackets. So bear in mind that in m4 macros for Autoconf, square brackets mean literal not-for-expansion text, and in m4 macro documentation it means an optional argument.

What macros do we need for a functional Autoconf file? In order of appearance:

AC_INIT(…), already shown.LT_INITsets up Libtool, which you need if and only if you are installing a shared library.AC_CONFIG_FILES([, which tells Autoconf to go through those files listed and replace variables likeMakefile subdir/Makefile])@cc@with their appropriate value. If you have several makefiles (typically in subdirectories), then list them here.

So we have the specification for a functional build package for any POSIX system anywhere in four or five lines, three of which Autoscan probably wrote for you.

But the real art that takes configure.ac from

functional to intelligent is in predicting problems some users might

have and finding the Autoconf macro that detects the problem (and, where

possible, fixes it). You saw one example earlier: I recommended adding

AC_PROG_CC_C99 to

configure.ac to check for a C99 compiler. The POSIX

standard requires that one be present via the command name c99, but just because POSIX says so doesn’t

mean that every system will have one, so it is exactly the sort of thing

that a good configure script checks for.

Having libraries on hand is the star example of a prerequisite

that has to be checked. Getting back to Autoconf’s outputs for a moment,

config.h is a standard C header consisting of a

series of #define statements. For

example, if Autoconf verified the presence of the GSL, you would

find:

#define HAVE_LIBGSL 1

in config.h. You can then put #ifdefs into your C code to behave

appropriately under appropriate circumstances.

Autoconf’s check doesn’t just find the library based on some naming scheme and hope that it actually works. It writes a do-nothing program using any one function somewhere in the library, then tries linking the program with the library. If the link step succeeds, then the linker was able to find and use the library as expected. So Autoscan can’t autogenerate a check for the library, because it doesn’t know what functions are to be found in it. The macro to check for a library is a one-liner, to which you provide the library name and a function that can be used for the check. For example:

AC_CHECK_LIB([glib-2.0],[g_free]) AC_CHECK_LIB([gsl],[gsl_blas_dgemm])

Add one line to configure.ac for every

library you use that is not 100% guaranteed by the C standard, and those

one-liners will blossom into the appropriate shell script snippets in

configure.

You may recall how package managers always split libraries into the binary shared object package and the devel package with the headers. Users of your library might not remember (or even know) to install the header package, so check for it with, for example:

AC_CHECK_HEADER([gsl/gsl_matrix.h], , [AC_MSG_ERROR(

[Couldn’t find the GSL header files (I searched for \

<gsl/gsl_matrix.h> on the include path). If you are \

using a package manager, don’t forget to install the \

libgsl-devel package, as well as libgsl itself.])])Notice the two commas: the arguments to the macro are (header to check, action if found, action if not found), and we are leaving the second blank.

What else could go wrong in a compilation? It’s hard to become an

authority on all the glitches of all the world’s computers, given that

we each have only a couple of machines at our disposal. Autoscan will

give you some good suggestions, and you might find that running autoreconf also spits out some further

warnings about elements to add to configure.ac. It

gives good advice—follow its suggestions. But the best reference I have

seen—a veritable litany of close readings of the POSIX standard,

implementation failures, and practical advice—is the Autoconf manual

itself. Some of it catalogs the glitches that Autoconf takes care of and

are thus (thankfully) irrelevant nitpicking for the rest of us,[7] some of it is good advice for your code-writing, and some

of the descriptions of system quirks are followed by the name of an

Autoconf macro to include in your project’s

configure.ac should it be relevant to your

situation.

More Bits of Shell

Because configure.ac is a compressed

version of the configure script the

user will run, you can throw in any arbitrary shell code you’d like.

Before you do, double-check that what you want to do isn’t yet handled

by any macros—is your situation really so unique that it never

happened to any Autotools users before?

If you don’t find it in the Autoconf package itself, you can check the GNU Autoconf macro archive for additional macros, which you can save to an m4 subdirectory in your project directory, where Autoconf will be able to find and use them. See also [Calcote 2010], an invaluable overview of the hairy details of Autotools.

A banner notifying users that they’ve made it through the

configure process might be nice, and there’s no need for a macro,

because all you need is echo.

Here’s a sample banner:

echo \ "-----------------------------------------------------------

Thank you for installing ${PACKAGE_NAME} version ${PACKAGE_VERSION}.Installation directory prefix: '${prefix}'.

Compilation command: '${CC} ${CFLAGS} ${CPPFLAGS}'Now type 'make; sudo make install' to generate the program and install it to your system.

------------------------------------------------------------"

The banner uses several variables defined by Autoconf. There’s

documentation about what shell variables the system defines for you to

use, but you can also find the defined variables by skimming configure itself.

There’s one more extended example of Autotools at work, linking to a Python library in Python Host.

[7] For example, “Solaris 10 dtksh and the UnixWare 7.1.1 Posix shell … mishandle braced variable expansion that crosses a 1024- or 4096-byte buffer boundary within a here-document.”