Chapter 3. Event-Based Architectures

Using factories of various abstractions, façades, and other patterns is not the only way to decouple dependencies and isolate code. A more JavaScript-oriented approach involves the use of events. The functional nature of JavaScript makes it an ideal language for event-based programming.

The Benefits of Event-Based Programming

At their core, all applications revolve around message passing. Tight

coupling can occur because the code needs to have a reference to another

object so that it can send the object a message and perhaps receive a

reply. These objects are global, passed in, or injected via a function

parameter, or they are instantiated locally. Our use of factories in the

preceding chapter enabled us to pry away the local instantiation

requirement; however, we still need the object to be available locally in

order to pass messages to it, which means we still must deal with global

or injected dependencies. Global dependencies are dangerous: any part of

the system can touch them, making bugs very difficult to track down; we

can accidentally change them if we have a variable by the same or a

similar name declared locally; and they cause data encapsulation to break

since they are available everywhere, making debugging very difficult.

JavaScript makes declaration and use of global variables very easy, and the environment typically

provides several global variables (e.g., the window object in the global scope), as well as global functions and

objects (e.g., the YUI object, or

$ from jQuery). This means we must be

careful to not just dump variables into the global scope, as there already

are a lot of them there.

If we want to neither instantiate objects locally nor put them in the global namespace, we are left with injection. Injection is not a panacea, though, as we now must have setter functions and/or update constructors to handle injection, and more importantly, we now must deal with the care and feeding of either factories or a dependency injection framework. This is boilerplate code that must be maintained and managed and is code that is not specific to our application.

To recap, the problem with dependencies arises because we need to interact with other pieces of code that may be internal or external to our application. We may need to pass parameters to this other code. We may expect a result from this other code. This code may take a long time to run or return. We may want to wait for this code to finish and return before continuing, or keep plowing ahead while it churns away. Typically, this is all accomplished by holding direct references to other objects. We have these references; we shake them up by calling methods or setting properties, and then get the results.

But event-based programming provides an alternative way to pass messages to objects. By itself, the use of events is not much different from calling a method with a level of indirection through an event-handling framework. You still need to have a local reference to the object to throw an event to it, or to listen for events coming from it.

Interestingly, the JavaScript language has no formal support for events and callbacks; historically, the language has only provided functions as first-class objects. This allowed JavaScript to ditch the interface-based model of Java event listeners wherein everything must be an object, leading to some very clunky syntax. The event model provided by the DOM in browsers brought event-based JavaScript programming to the core, followed by the Node.js approach of asynchronous programming utilizing callbacks extensively.

Event-based programming all boils down to two primary pieces: the call and the return. It transforms the call into a parameterized thrown event and the return into a parameterized callback. The magic occurs when the requirement for a local reference to make these calls and returns is abstracted away, allowing us to interact with other code without having to have a local reference to it.

The Event Hub

The idea behind events is simple: methods register with an event hub, advertising themselves as capable of handling certain events. Methods utilize the hub as the single central location to which to throw event requests and from which to await responses. Methods can both register for and throw events. Methods receive asynchronous responses via callbacks. Your application’s classes or methods require only one reference to the event hub. All communication is brokered through the event hub. Code running in a browser or on a server has equal access to the hub.

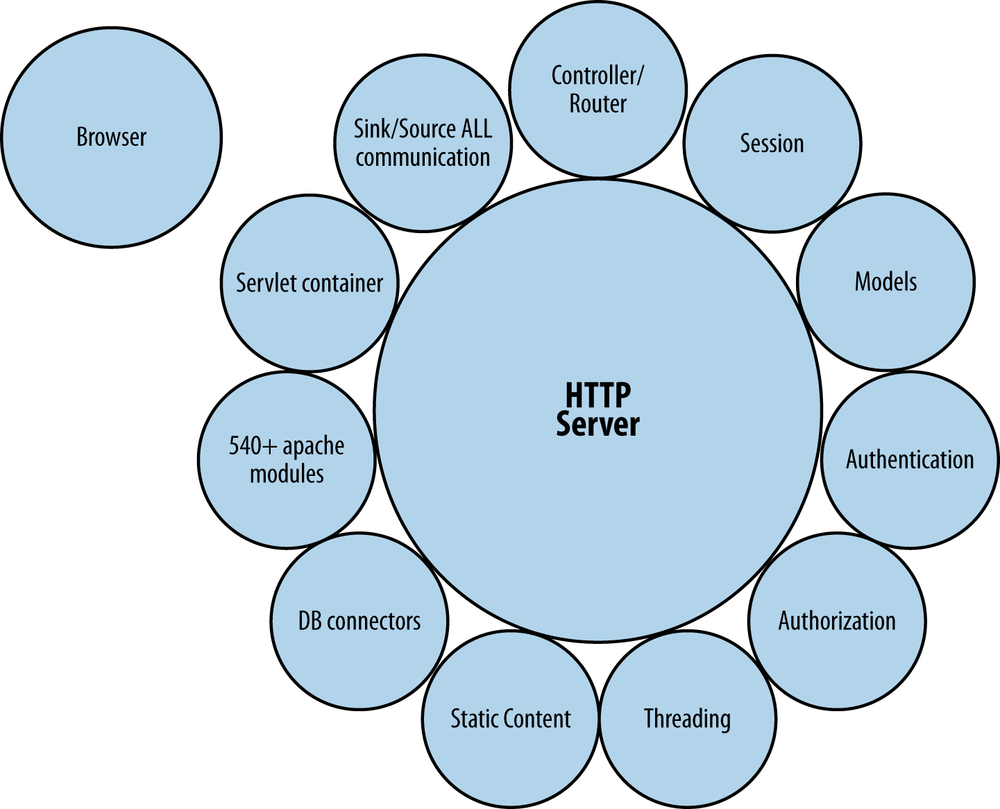

A typical web application is tightly coupled to the web server itself, as shown in Figure 3-1.

As you can see in the figure, browsers and clients are off on their own, connecting to an HTTP server laden with services and modules. All extra services are tightly coupled to the HTTP server itself and provide all the other required services. Furthermore, all communication between clients and modules is brokered through the HTTP server, which is unfortunate, as HTTP servers are really best for just serving static content (their original intent). Event-based programming aims to replace the HTTP server with an event hub as the center of the universe.

As the following code shows, all we need to do is add a reference to the hub to join the system. This works great for multiple clients and backends all joining the same party:

eventHub.fire(

'LOG'

, {

severity: 'DEBUG'

, message: "I'm doing something"

}

);Meanwhile, somewhere (anywhere) else—on the server, perhaps—the

following code listens for and acts on the LOG event:

eventHub.listen('LOG', logIt);

function logIt(what) {

// do something interesting

console.log(what.severity + ': ' + what.message);

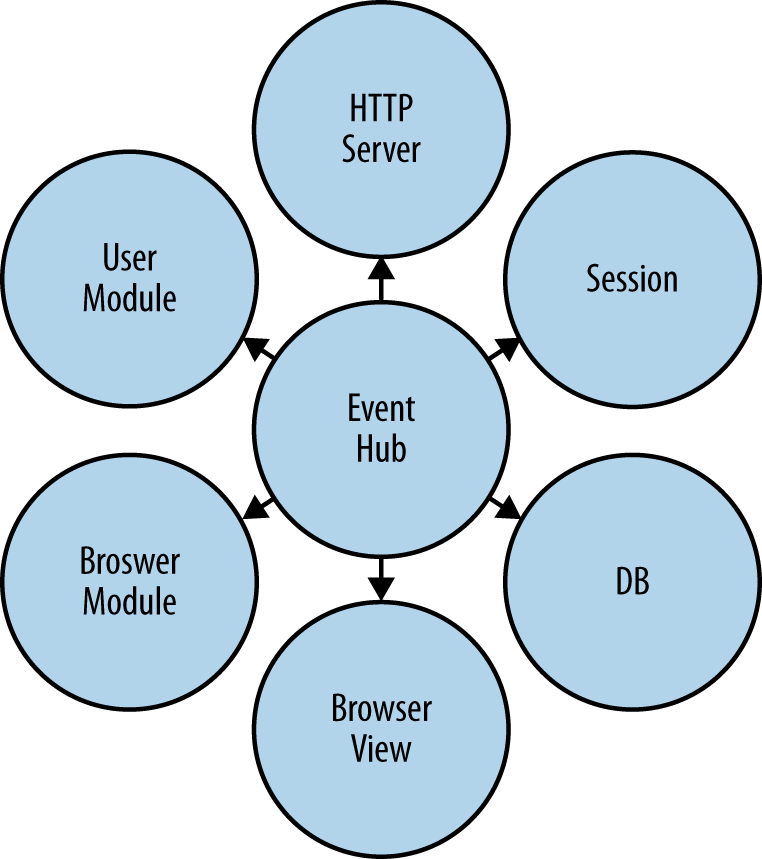

}The event hub joins these two otherwise disconnected pieces of code. Disregard what is happening behind the scenes; messages are being passed between event hub clients regardless of their location. Figure 3-2 illustrates the relationship between the hub and all of its connected modules. Note that the HTTP server is no longer the center of the universe, but is relegated to being a service-providing module similar to all other connected modules.

But now are we commonly coupled? As we discussed in Chapter 2, common coupling is the second tightest form

of coupling, wherein objects share a common global variable. Regardless of

whether the EventHub object is global

or is passed into each object as a parameter, this is not common coupling.

While all objects use the common EventHub, they do not alter it or share

information through it by changing its state. This is an important

distinction and an interesting case for an EventHub versus other kinds of global objects.

Although all communication between objects is brokered through an EventHub object, there is no shared state in the

EventHub object.

Using the Event Hub

So, the game is to have pieces join the hub and start firing, listening for, and responding to events. Instead of making method calls (which requires a local instantiation of an object, coupling, fan-out, and local mocking and stubbing), throw an event and (possibly) wait for the response (if you need one).

A hub can run wherever you like on the server side. Clients can connect to it and fire and subscribe to events.

Typically, browser-based clients fire events and server-based clients consume them, but of course any client can fire and consume events.

This architecture plays to JavaScript’s functional strengths and encourages small bits of tightly focused code with minimal dependencies. Using events instead of method calls greatly increases testability and maintainability by encouraging developers to write smaller chunks of code with minimal dependencies. Anything external to a module is provided as a service instead of being wrapped within a dependency. The only function calls should be to the hub or to methods local to the object or module.

Let’s take a look at some canonical login logic. Here is the standard Ajax-based login using the YUI framework:

YUI().add('login', function(Y) {

Y.one('#submitButton').on('click', logIn);

function logIn(e) {

var username = Y.one('#username').get('value')

, password = Y.one('#password').get('value')

, cfg = {

data: JSON.stringify(

{username: username, password: password })

, method: 'POST'

, on: {

complete: function(tid, resp, args) {

if (resp.status === 200) {

var response = JSON.parse(resp.responseText);

if (response.loginOk) {

userLoggedIn(username);

} else {

failedLogin(username);

}

} else {

networkError(resp);

}

}

}

}

, request = Y.io('/login', cfg)

;

}

}, '1.0', { requires: [ 'node', 'io-base' ] });At 27 lines of code, that login isn’t too bad. Here is the equivalent using event-based programming (using the YUI Event Hub module):

YUI().add('login', function(Y) {

Y.one('#submitButton').on('click', logIn);

function logIn(e) {

var username = Y.one('#username').get('value')

, password = Y.one('#password').get('value')

;

eventHub.fire('logIn'

, { username: username, password: password }

, function(err, resp) {

if (!err) {

if (resp.loginOk) {

userLoggedIn(username);

} else {

failedLogin(username);

}

} else {

networkError(err);

}

});

}

}, '1.0', { requires: [ 'node', 'EventHub' ] });This code is only 18 lines long, representing a whopping 33% code savings. But in addition to fewer lines of code, testing is simplified. To illustrate this, let’s conduct a unit test of the standard Ajax version and compare it to a unit test of the event-hub-based version. (We will discuss unit tests in detail in Chapter 4, so don’t get too bogged down in the syntax if you are not familiar with YUI Test. We’ll start with the Ajax version, beginning with the setup:

YUI().use('test', 'console', 'node-event-simulate'

, 'login', function(Y) {

// Factory for mocking Y.io

var getFakeIO = function(args) {

return function(url, config) {

Y.Assert.areEqual(url, args.url);

Y.Assert.areEqual(config.data, args.data);

Y.Assert.areEqual(config.method, args.method);

Y.Assert.isFunction(config.on.complete);

config.on.complete(1, args.responseArg);

};

}

, realIO = Y.io;This is standard boilerplate YUI code that loads the external

modules our tests depend on, including our login module, which we will be testing. The

code also includes the factory for creating a mocked Y.io instance, which is YUI’s veneer over

XMLHttpRequest. This object will ensure that the correct values are passed to

it. Finally, we keep a reference to the real Y.io instance so that it can be restored for

other tests.

Here is the test itself:

var testCase = new Y.Test.Case({

name: "test ajax login"

, tearDown: function() {

Y.io = realIO;

}

, testLogin : function () {

var username = 'mark'

, password = 'rox'

;

Y.io = getFakeIO({

url: '/login'

, data: JSON.stringify({

username: username

, password: password

})

, method: 'POST'

, responseArg: {

status: 200

, responseText: JSON.stringify({ loginOk: true })

}

});

userLoggedIn = function(user) {

Y.Assert.areEqual(user, username); };

failedLogin = function() {

Y.Assert.fail('login should have succeeded!'); };

networkError = function() {

Y.Assert.fail('login should have succeeded!'); };

Y.one('#username').set('value', username);

Y.one('#password').set('value', password);

Y.one('#submitButton').simulate('click');

}

});The preceding code is testing a successful login attempt. We set

up our fake Y.io object and mock the

possible resultant functions our login module calls to ensure that the

correct one is used. Then we set up the HTML elements with known values

so that clicking Submit will start the whole thing off. One thing to

note is the teardown function

that restores Y.io to its original

value. The mocking of Y.io is a bit

clunky (although not horribly so), as Ajax only deals with strings and

we need to keep track of the HTTP status from the server. For

completeness, here is the rest of the test module, which is all

boilerplate:

var suite = new Y.Test.Suite('login');

suite.add(testCase);

Y.Test.Runner.add(suite);

//Initialize the console

new Y.Console({

newestOnTop: false

}).render('#log');

Y.Test.Runner.run();

});Let’s now look at a unit test for the event-based code. Here is the beginning portion:

YUI().use('test', 'console', 'node-event-simulate'

, 'login', function(Y) {

// Factory for mocking EH

var getFakeEH = function(args) {

return {

fire: function(event, eventArgs, cb) {

Y.Assert.areEqual(event, args.event);

Y.Assert.areEqual(JSON.stringify(eventArgs),

JSON.stringify(args.data));

Y.Assert.isFunction(cb);

cb(args.err, args.responseArg);

}

};

};

});Here we see the same boilerplate at the top and a similar factor for mocking out the event handler itself. Although this code is slightly cleaner, some unfortunate ugliness crops up when comparing the two objects for equality, as YUI does not provide a standard object comparator method.

Here is the actual test:

var testCase = new Y.Test.Case({

name: "test eh login"

, testLogin : function () {

var username = 'mark'

, password = 'rox'

;

eventHub = getFakeEH({

event: 'logIn'

, data: {

username: username

, password: password

}

, responseArg: { loginOk: true }

});

userLoggedIn = function(user) {

Y.Assert.areEqual(user, username); };

failedLogin = function() {

Y.Assert.fail('login should have succeeded!'); };

networkError = function() {

Y.Assert.fail('login should have succeeded!'); };

Y.one('#username').set('value', username);

Y.one('#password').set('value', password);

Y.one('#submitButton').simulate('click');

}

});This is very similar to the previous code. We get a mocked version of the event hub, prime the HTML elements, and click the Submit button to start it off. The exact same post-test boilerplate code present from the previous Ajax test is also necessary here to complete the example (refer back to that code if you want to see it again!).

This example illustrates that the base code and the test code are smaller for the event-based example, while providing more semantic usage and more functionality. For example, the event-based code handles cross-domain (secure or not) communication without any changes. There is no need for JSONP, Flash, hidden iframes, or other tricks, which add complexity to both the code and the tests. Serialization and deserialization are handled transparently. Errors passed as objects, not as HTTP status codes, are buried within the response object. Endpoints are abstracted away from URLs to arbitrary strings. And finally (and perhaps most importantly), this kind of event-based architecture completely frees us from the tyranny of instantiating and maintaining tightly coupled pointers to external objects.

The test code for Ajax requests really grows when using more of

the features of XMLHttpRequest and

Y.io, such as the success and failure callbacks, which also need to be

mocked. There are more complex usages that require more testing

complexity.

Responses to Thrown Events

There are three possible responses to a thrown event: no response, a generic response, or a specific response. Using events for message passing is simplest when no reply is necessary. In a typical event system, sending events is easy but getting replies is problematic. You could set up a listener for a specific event directly tied to the event that was just fired. This approach is similar to giving each event a unique ID; you could then listen for a specifically named event containing the request ID to get the response. But that sure is ugly, which is why eventing has typically been relegated to “one-way” communication, with logging, UI actions, and notifications (typically signifying that something is now “ready”) being the most common event use cases. However, two-way asynchronous communication is possible using callbacks, which handle generic and specific responses. Let’s look at some examples.

Obviously, if no response is necessary, we can simply throw the event and move on:

eventHub.fire('LOG', { level: 'debug', message: 'This is cool' });If a specific response to the thrown event is not necessary and a

more generic response is sufficient, the remote

listener can throw the generic event in response. For example, if a new

user registers a generic USER_REGISTERED event, a generic response may

be the only “reply” that is necessary:

// somewhere on server

eventHub.on('REGISTER_USER', function(obj) {

// stick obj.name into user DB

eventHub.fire('USER_REGISTERED', { name: obj.name });

});

// somewhere global

eventHub.on('USER_REGISTERED', function(user) {

console.log(user.name + ' registered!');

});

// somewhere specific

eventHub.fire('REGISTER_USER', { name: 'mark' });In this example, the REGISTER_USER event handler is sitting on a

server writing to a database. After registering the user by adding him

to the database, the handler throws another event, the USER_REGISTERED event. Another listener

listens for this event. That other listener then handles the

application’s logic after the user has been registered—by updating the

UI, for example. Of course, there can be multiple listeners for each

event, so perhaps one USER_REGISTERED

event can update an admin panel, another can update the specific user’s

UI, and yet another can send an email to an administrator with the new

user’s information.

Finally, in some cases a specific response sent directly back to the event thrower is required. This is exactly the same as making a method call, but asynchronously. If a direct reply is necessary, an event hub provides callbacks to the event emitter. The callback is passed as a parameter by the event emitter to the hub. For example:

// Somewhere on the server

eventHub.on('ADD_TO_CART'

, function(userId, itemId, callback) {

d.cart.push(itemId);

callback(null, { items: userId.cart.length });

});

// Meanwhile, somewhere else (in the browser, probably)

function addItemToCart(userId, itemId) {

eventHub.fire('ADD_TO_CART'

, { user_id: userId, item_id: itemId }

, function(err, result) {

if (!err) {

console.log('Cart now has: ' + result.cart.items + ' items');

}

});

}Here, we fire a generic ADD_TO_CART event with some information and we

wait for the callback. The supplied callback to the event hub is called

with data provided by the listener.

Event-Based Architectures and MVC Approaches

How do event-based architectures compare with Model-View-Controller (MVC) approaches? They are actually quite similar. In fact, event-based architectures help to enforce the separation of concerns and modularity that MVC advocates.

But there are a few differences between the two, with the biggest

difference being that in event-based architectures models are turned

inside out, eliminated, or pulled apart, depending on how you like to

think about these things. For example, using MVC, a Model class is instantiated for each database row; this class provides

the data and the methods that operate on that data. In an event-based

architecture, models are simple hashes storing only data; this data is

passed using events for listeners (you can call them models, I suppose)

to operate on. This separation of data and functionality can provide

greater testability, memory savings, greater modularity, and higher

scalability, all with the benefits of putting the data and methods

together in the first place. Instead of lots of individual instantiated

Model objects floating around, there

are lots of data hashes floating around, and one instantiated object to

operate on them all.

The controller is now simply the event hub, blindly passing events between views and models. The event hub can have some logic associated with it, such as being smarter about where to pass events instead of passing them blindly to all listeners. The event hub can also detect events being thrown with no listeners and return an appropriate error message. Beyond event-specific logic, the controller in an event-centered world is just a dumb hub (perhaps upgraded to a slightly smarter switch, exactly like Ethernet hubs and switches).

Views, perhaps the least changed, have data pushed to them via events instead of querying models. Upon a user-initiated event, views “model” the data and throw the appropriate event. Any required UI updates are notified by events.

Event-Based Architectures and Object-Oriented Programming

Storing data along with the methods that operate on it is the basic tenet of object-oriented programming. Another tenet of object-oriented programming is reuse. The theory is that more generic superclasses can be reused by more specific subclasses. Object-oriented methodology introduces another form of coupling: inheritance coupling. There is nothing stopping an event-based programmer from using object-oriented principles when designing her listeners, but she will encounter a few twists.

For starters, the entire application is not based on object-oriented programming. In addition, there are no chains of interconnected objects connected only by inheritance or interface coupling, and the application is not running in a single thread or process, but rather in multiple processes. But the biggest difference is that the data is not stored within the objects. Singleton objects are instantiated with methods that operate on the data, and data is passed to these objects to be operated on.

There are no “public,” “private,” or “protected” modifiers—everything is private. The only communication with the “outside” world is via the event-based API. As these objects are not instantiated by dependents, there is no need to worry that an external object will mess with your internals. There are no life-cycle issues, as the objects live for the entire life of the application, so constructors (if there are any) are called once at the beginning and destructors are unnecessary.

Event-Based Architectures and Software as a Service

Event-based architectures facilitate Software as a Service (SaaS). Each independent piece can join the event hub to provide a service in isolation from all the other services used to create the application. You can easily imagine a repository of services either available for download or accessible over the Internet for your application to use. Your application would connect to their hub to access their services. The “API” for these services is a unique event name with which to call exposed actions and the data that must be present in the event. Optionally, the service can either fire another event upon completion or use the callback mechanism for responses, if any response is necessary.

Web-Based Applications

Most web-based applications are intractably intertwined with a web server. This is unfortunate, as HTTP servers were never originally built to have the amount of functionality we cram into them today. HTTP servers are built to negotiate Hypertext Transfer Protocol data and to serve static content. Everything else has been bolted on over time and has made web applications unnecessarily complex.

Mixing application logic into the web server and/or relying on a web

server to be the central hub of an application not only ties our

application to HTTP, but also requires a lot of care and feeding of the

web server to keep the application running. Lots of tricks have been

created and abused over the years to try to make HTTP support two-way

asynchronous communication, but some shortcomings remain. While the socket.io library

does support running over HTTP, it also supports Web Sockets transparently

for when that protocol becomes more widely available.

Web-based applications also suffer from the “same-origin” principle,

which severely limits how code can interact with code from differing

origins. HTML5 brings postMessage as a

workaround, but by using a socket.io-based event architecture this can all

be easily bypassed.

The event hub in an event-based architecture becomes the hub, not the web server. This is preferable, as the event hub is built from the ground up to be a hub without any unnecessary bits, which web servers have in spades. Additional functionality is built not into the hub itself, but into remote clients, which are much more loosely coupled and significantly easier to test.

Testing Event-Based Architectures

Testing event-based architectures involves merely calling the function that implements the action. Here is an interesting case:

// Some handle to a datastore

function DB(eventHub, dbHandle) {

// Add user function

eventHub.on('CREATE_USER', createAddUserHandler(eventHub, dbHandle));

}

function createAddUserHandler(eventHub, dbHandle) {

return function addUser(user) {

var result = dbHandle.addRow('user', user);

eventHub.fire('USER_CREATED', {

success: result.success

, message: result.message

, user: user

});

}

}There are several curious things to note about this piece of code.

First, there is no callback, and events are used instead to broadcast the

success or failure of this operation. You may be tempted to use a callback

so that the caller knows whether this action succeeded, but by

broadcasting the response we allow other interested parties to know

whether a user was created successfully. Multiple clients may all want to

be informed if a new user is created. This way, any browser or server-side

client will be notified of this event. This also allows a separate module

to handle the results of an attempted user creation event, instead of

forcing that code to be within the addUser code. Of course, it can live in the same

file as the addUser code, but it does

not have to. This helps tremendously

in terms of modularity. In fact, typically a module on the server side and

a module on the client side will both want to know whether a user was

created and take action because of it. The client-side listener will want

to update the UI and a server-side listener can update other internal

structures.

Here the eventHub and databaseHandle are injected into the

constructor, aiding testing and modularity as well. No object is created;

only event listeners are registered to the injected eventHub. This is the essence of event-based

architectures: event listeners are registered and no (or few) objects are

instantiated.

A browser-based handler could look like this:

eventHub.on('USER_CREATED', function(data) {

dialog.show('User created: ' + data.success);

});A server-side handler could look like this:

eventHub.on('USER_CREATED', function(data) {

console.log('User created: ' + data.success);

});The preceding code would pop up a dialog anytime anyone attempted to create a user from this browser, from any other browser, or even on the server side. If this is what you want, having this event be broadcast is the answer. If not, use a callback.

It is also possible to indicate in the event whether you expect the result to be in a callback or in an event (you could even live it up and do both!). Here is how the client-side code would look:

eventHub.fire('CREATE_USER', user);Here is how the server-side code would look:

eventHub.fire('CREATE_USER', user);It can’t get any simpler than that.

To test this function, you can use a mocked-up event hub and a stubbed-out database handle that verifies events are being fired properly:

YUI().use('test', function(Y) {

var eventHub = Y.Mock()

, addUserTests = new Y.Test.Case({

name: 'add user'

, testAddOne: function() {

var user = { user_id: 'mark' }

, dbHandle = { // DB stub

addRow: function(user) {

return { user: user

, success: true

, message: 'ok' };

}

}

, addUser = createAddUserHandler(eventHub, dbHandle)

;

Y.Mock.expect(

eventHub

, 'fire'

, [

'USER_CREATED'

, { success: true, message: 'ok', user: user }

]

);

DB(eventHub, dbHandle); // Inject test versions

addUser(user);

Y.Mock.verify(eventHub);

}

});

eventHub.on = function(event, func) {};

eventHub.fire = function(event, data) {};

Y.Test.Runner.add(addUserTests);

Y.Test.Runner.run();

});This test case uses both a mock (for the event hub) and a stub (for

the DB handle) to test the addUser function. The fire event is expected to be called on the

eventHub object by the addUser function with the appropriate arguments.

The stubbed DB object’s addRow function is set to return canned data.

Both of these objects are injected into the DB object for testing, and we are off and

running.

The end result of all of this is simply testing that the addUser function emits the proper event with the

proper arguments.

Compare this with a more standard approach using an instantiated

DB object with an addUser method on its prototype:

var DB = function(dbHandle) {

this.handle = dbHandle;

};

DB.prototype.addUser = function(user) {

var result = dbHandle.addRow('user', user);

return {

success: result.success

, message: result.message

, user: user

};

};How would client-side code access this?

transporter.sendMessage('addUser', user);A global or centralized message-passing mechanism would post a

message back to the server using Ajax or something equivalent. It would do

so perhaps after updating or creating an instantiated user model object on the client side. That piece

would need to keep track of requests and responses, and the server-side

code would need to route that message to the global DB singleton, marshal the response, and send the

response back to the client.

Here is a test for this code:

YUI().use('test', function(Y) {

var addUserTests = new Y.Test.Case({

name: 'add user'

, addOne: function() {

var user = { user_id: 'mark' }

, dbHandle = { // DB stub

addRow: function(user) {

return {

user: user

, success: true

, message: 'ok'

};

}

}

, result

;

DB(dbHandle); // Inject test versions

result = addUser(user);

Y.Assert.areSame(result.user, user.user);

Y.Assert.isTrue(result.success);

Y.Assert.areSame(result.message, 'ok');

}

})

;

Y.Test.Runner.add(addUserTests);

Y.Test.Runner.run();

});In this case, as the DB object

has no dependencies, the tests look similar.

For a client to add a new user, a new protocol between the client

and the server must be created, a route in the server must be created to

hand off the “add user” message to this DB object, and the results must be serialized

and passed back to the caller. That is a lot of plumbing that needs to be

re-created for every message type. Eventually, you will end up with a

cobbled-together RPC system that an event hub gives you for free.

That kind of code is a great example of the 85% of boilerplate code you should not be implementing yourself. All applications boil down to message passing and job control. Applications pass messages and wait for replies. Writing and testing all of that boilerplate code adds a lot of overhead to any application, and it is unnecessary overhead. What if you also want a command-line interface to your application? That is another code path you must implement and maintain. Let an event hub give it to you for free.

Caveats to Event-Based Architectures

An event-based architecture is not the answer to all problems. Here are some issues you must keep in mind when using such an architecture.

Scalability

An event hub creates a super single point of failure: if the hub goes

down, your application goes down with it. You need to either put a set

of event hubs behind a load balancer, or build failing over to another

event hub into your application. This is no different from adding more

web servers; in fact it’s actually simpler, as you do not have to worry

about the same-origin policy using socket.io.

Broadcasting

A lot of events being broadcast to all clients can potentially result in a lot of traffic. Guards should be put in place to ensure that events that are meant to be consumed locally do not get sent to the hub. Further, the hub itself can act more like a switch than a hub if it knows which client is listening for an event, sending it directly there instead of broadcasting it.

Runtime Checking

Whereas misspelling a function or method name will result in a runtime error, the compiler cannot check string event names for misspellings. Therefore, it is highly recommended that you use enumerations or hashes for event names instead of typing them over and over. A nice way to get runtime checking of your event names is to do something like this:

// Return an object with 'on' and 'fire' functions for the specified

// eventName

hub.addEvent = function(eventName) {

var _this = this;

this.events[eventName] = {

on: function(callback) {

_this.on.call(_this, eventName, callback);

}

, fire: function() {

Array.prototype.unshift.call(arguments, eventName);

this.fire.apply(_this, arguments);

}

};

return this.events[eventName];

};You would use this code as follows:

var clickEvent = hub.addEvent('click');

clickEvent.on(function(data) { /* got a click event! */ });

clickEvent.fire({ button: 'clicked' }); // fired a click event!Now you have runtime checking of event names.

Security

If you’re afraid that random unwashed masses will connect to your event hub and inject any events they want, don’t be; the event hub implementation requires “trusted” clients to authenticate with the hub.

If you want to encrypt event hub connections, you can build your

event hub solution using socket.io, which

supports encrypted connections.

State

State, which typically is provided by a web server via a session cookie, moves from the web server to a module. Upon web application load, a new session object can be created and persisted completely independently of a web server. The client-side JavaScript writes the session token as a cookie itself, which is then available to the web server if it needs to serve authenticated-only content. The event hub itself injects the session into events, making it impossible for one session to masquerade as another.

Trusted (typically server-side) modules get the session key, and therefore the state, from untrusted (typically client-side) events, passed as a parameter or hash field.

A Smarter Hub: The Event Switch

An event switch enhances event-based architectures by making them more modular and more deployable. If you are willing to add a bit of logic to the event hub and to the events themselves, your applications will be easier to deploy and manage.

By categorizing your events into two groups, broadcast and unicast, you will gain some neat features using an event switch instead of a hub. The biggest win (besides some network bandwidth savings) is fail-safe deployments.

One of the biggest promises of event-based architectures is modularity. A typical monolithic application is replaced with a number of independent modules, which is great for testability; using an event switch instead of a hub is great for deployability too.

An event switch knows the difference between broadcast and unicast events. Broadcast events behave exactly like all events do using an event hub. Unicast events are only sent to a single listener that has registered for the event. This feature makes deployment much simpler, as we shall see in the next section.

Deployment

A monolithic application typically has all the server-side logic intertwined with the HTTP server. Deploying a new version involves pushing the entire application logic at once and restarting the web server. To upgrade a portion of the application, everything must be pushed. The logic for event-based applications is completely separate from the web server; in fact, the logic of the application resides in many different independent modules. This makes pushing new versions of code much simpler, as the modules can be updated and deployed completely independently of one another and of the web server. Although there are more “moving parts” to deal with, you gain much finer-grained control of your deployment and code.

So, how can you safely stop a listener without dropping an event? You can use unicast events and broadcast events. An event switch is necessary for safely shutting down listeners without missing an event.

Unicast events

Unicast events, such as depositMoney

in the following code, have only one listener. In this case, a

listener must notify the event switch that this event is a unicast

event and that it is the (only) listener for it. When we’re ready to

upgrade, we need to start the new version of the module, which

announces to the event switch that it is now the sole listener for the

event. The event switch will notify the older module that it has been

replaced, and that module can now shut down cleanly after handling any

outstanding events. No events are lost; the event switch will switch

the unicast event over to the new listener, but the switch will remain

connected to the original listener to handle any callbacks or events

emitted by that listener while it finishes handling any outstanding

events. In this way, we have successfully shut down the old listener

and brought up a new one with no loss in service:

eventSwitch.on('depositMoney', function(data) {

cash += data.depositAmount;

eventSwitch.emit('depositedMoney', cash);

}, { type: 'unicast' });When we begin listening for this event, this code informs the

event switch that this is a unicast event, and that all events of this

name must go only to this listener. All we have done is add a third

parameter to the on method with

some metadata about the event, which the client passes to the

switch.

Meanwhile, the switch will replace the current listener for this event (if there is one) with the new listener, and will send a “hey, someone bumped you” event to the previous listener (again, if there was one). Any listener for this event should have another listener for the “go away” event too:

eventHub.on('eventClient:done', function(event) {

console.log('DONE LISTENING FOR ' + event);

// finish handling any outstanding events & then safely:

process.exit(0);

});The eventClient:done event

signifies that this listener will no longer receive the specified

event, and that when it is done processing any outstanding events it

can safely shut down or can continue to handle events it is still

listening for.

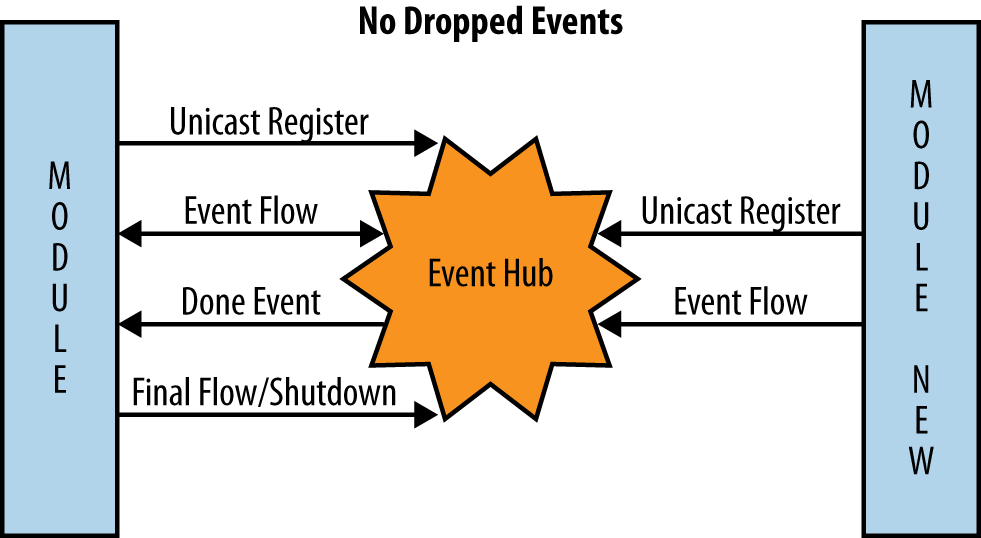

The atomic operation of the event switch ensures that no events

are dropped and none are sent to a listener that has been replaced. To

understand this more fully, take a look at Figure 3-3. In the figure,

time flows from the top of the picture to the bottom. The module on

the left registers for the unicast event, and events are delivered to

it. Then the updated module on the right registers for that same

unicast event. The first module receives the done event; all new event requests are sent

to the module on the right, while the module on the left finishes

handling any current events and then shuts down. The updated module

continues to serve event requests until another updated module

notifies the hub that it is now responsible for the unicast

event.

Broadcast events

Safely shutting down broadcast listeners follows a similar process. However, the event

listener itself will broadcast the eventClient:done event to signal to all

other listeners for the specified event that they should now shut

down. The event switch is smart enough to broadcast that event to

every listener except the one that emitted the event.

A listener receiving this event will no longer receive messages for the specified event. After processing any outstanding events, the listeners can now shut down safely:

eventHub.on('eventClient:done', function(event) {

console.log('I have been advised to stop listening for event: '

+ event);

eventHub.removeAllListeners(event);

});Note that the event switch is smart enough to not allow any

connected clients to fire eventClient:done events and will drop them

if it receives one. A rogue client cannot usurp the event switch’s

authority!

An Implementation

This sample

implementation of an event switch with clients for Node.js, YUI3, and

jQuery based on socket.io can be

installed using npm:

% npm install EventHubBuilt on top of socket.io, this

implementation provides a centralized hub running under Node.js and

provides event callback functions for direct responses. Most events do

not require a direct callback, so be careful and do not overuse that

feature. Think carefully about receiving a direct callback versus firing

another event when the action is complete.

After EventHub is installed,

simply start the hub:

% npm start EventHubThis starts the event switch listening on port 5883 by default. All clients need to point to the host and port where the hub is listening. Here is a Node.js client:

var EventHub = require('EventHub/clients/server/eventClient.js');

, eventHub = EventHub.getClientHub('http://localhost:5883');

eventHub.on('ADD_USER', function(user) {

// Add user logic

eventHub.fire('ADD_USER_DONE', { success: true, user: user });

});These lines of code instantiate an event hub client connecting to the previously started event hub (running on the same machine as this client, but of course it can run on another host). Simply execute this file:

% node client.jsNow any ADD_USER event fired by

any client will be routed to this function. Here is a client running in

a browser using YUI3:

<script src="http://yui.yahooapis.com/3.4.1/build/yui/yui-min.js">

</script>

<script src="/socket.io/socket.io.js"></script>

<script src="/clients/browser/yui3.js"></script>

<script>

YUI().use('node', 'EventHub', function(Y) {

var hub = new Y.EventHub(io, 'http://myhost:5883');

hub.on('eventHubReady', function() {

hub.on('ADD_USER_DONE', function(data) { };

... TIME PASSES ...

hub.fire('ADD_USER', user);

});

});

</script>After loading the YUI3 seed, socket.io, and the YUI3 EventHub client, a new EventHub client is instantiated, and when it’s

ready we listen for events and at some point fire the ADD_USER event. It’s that simple.

Here is the same example using jQuery:

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.6.2/jquery.min.js">

</script>

<script src="/socket.io/socket.io.js"></script>

<script src="/clients/browser/jquery.js"></script>

<script>

var hub = new $.fn.eventHub(io, 'http://myhost:5883');

hub.bind('eventHubReady', function() {

hub.bind('ADD_USER_DONE', function(data) { });

... TIME PASSES ...

hub.trigger('ADD_USER', user);

});

</script>The process is the same: load up the jQuery seed, socket.io, and the jQuery EventHub client.

The EventHub is provided

as a jQuery plug-in and uses the jQuery event syntax of bind and trigger.

Any event emitted by any client can have an optional callback function as the last parameter in the event arguments:

hub.fire('CHECK_USER', 'mark',

function(result) { console.log('exists: ' + result.exists); });And any responder to this event is given a corresponding function as the last parameter in the event argument list to pass back any arbitrary data:

hub.on('CHECK_USER', function(username, callback) {

callback({ exists: DB.exists(username) });

});This is slick! The callback

will execute the remote function in the caller’s space with the callee’s

provided data. The data is serialized as JSON, so do not get too crazy,

but if necessary you can receive a targeted

response to the event you fired!

You can also use the addEvent

helper for compile-time checking of event names using YUI3:

var clickEvent = hub.addEvent('click');

clickEvent.on(function(data) { /* got a click event! */ });

clickEvent.fire({ button: 'clicked' }); // fired a click event!This is exactly as outlined earlier. In the jQuery world, you use

bind and trigger instead:

var clickEvent = hub.addEvent('click');

clickEvent.bind(function(data) { /* got a click event! */ });

clickEvent.trigger({ button: 'clicked' }); // triggered a click event!Finally, you can use event switch features for unicast events:

hub.on('CHECK_USER', function(username, callback) {

callback({ exists: DB.exists(username) });

}, { type: 'unicast' });You can kick off any other listeners for broadcast events, like so:

// this goes to everyone BUT me...

hub.fire('eventClient:done', 'user:addUser');To play nicely you must listen for this event:

hub.on('eventClient:done', function(event) {

console.log('DONE LISTENING FOR ' + event);

hub.removeAllListeners(event);

});This will be fired by the event switch itself when a new unicast listener comes online or by a user module when broadcast modules are being upgraded.

Sessions

Trusted unicast listeners receive session data from thrown events. A “trusted” client connects to the hub using a shared secret:

eventHub = require('EventHub/clients/server/eventClient.js')

.getClientHub('http://localhost:5883?token=secret)Now this client can listen for unicast events. All unicast events receive extra session data in their event callbacks:

eventHub.on('user', function(obj) {

var sessionID = obj['eventHub:session'];

...

});The eventHub:session key is a

unique string (a UUID) that identifies this session. Trusted listeners

should utilize this key when storing and accessing session data.

Session keys are completely transparent to untrusted clients. Both the YUI3 and jQuery clients persist the session key into a cookie.

The HTTP server, just a trusted event hub client, leverages the session key from the cookie on an HTTP request when deciding to send trusted, authenticated, or personalized content to the browser.

Extensibility

The socket.io library has

clients in many languages, so services you use are not

limited to only JavaScript client implementations. It is relatively

trivial (I hope!) for users of other languages supported by socket.io to write an EventHub client using their language of

choice.

Note

Poke around here to see how a web application works and is transformed by using the event hub implementation versus the standard web server implementation. It really is just a playground for putting event-based web application ideas into practice to see how it all shakes out.

Recap

Event-based architectures are not a panacea. However, their high modularity, loose coupling, small dependency count, and high reusability provide an excellent basis upon which to create testable JavaScript. By taking away a large swath of boilerplate code, event hubs let you focus on the 15% of the application’s code that makes your project unique.

The sample event hub implementation has a very small code size,

built upon the excellent socket.io

library. The crux of the event hub code itself consists of fewer than 20

lines. The YUI3, jQuery, and Node.js clients are also vanishingly small.

Given the functionality, testability, maintainability, and scalability

provided, it is a no-brainer to actively investigate and prove how easy

and natural using an event hub can be, instead of locally instantiating

objects.

The MVC paradigm is actually enhanced using events. The controller and views are kept separate from the models and themselves. Models are passed around as event data and the logic is encapsulated into independent services. Views are notified via events of changes. The controller is merely the event hub itself. The essence of MVC, separation of concerns, is made more explicit.

Event-based architectures enable the Software as a Service model, whereby small, independent bits of functionality are added and removed dynamically as needed, providing services to the application.

Deploying event-based applications is much easier using an event switch. It allows individual modules to be shut down and new ones started without losing any events. This allows your application to be deployed in piecemeal fashion instead of all at once. Instead of a Big Bang when upgrading, you can upgrade individual modules in isolation, allowing your code and processes to be much more agile.

Testing the already isolated modules is also much more straightforward, and dependency and fan-out counts are greatly reduced. Give an event-based architecture a whirl today!